Abstract

The outbreak of monkeypox, coupled with the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic is a critical communicable disease. This study aimed to systematically identify and review research done on preclinical studies focusing on the potential monkeypox treatment and immunization. The presented juxtaposition of efficacy of potential treatments and vaccination that had been tested in preclinical trials could serve as a useful primer of monkeypox virus. The literature identified using key terms such as monkeypox virus or management or vaccine stringed using Boolean operators was systematically reviewed. Pubmed, SCOPUS, Cochrane, and preprint databases were used, and screening was performed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. A total of 467 results from registered databases and 116 from grey literature databases were screened. Of these results, 72 studies from registered databases and three grey literature studies underwent full-text screening for eligibility. In this systematic review, a total of 27 articles were eligible according to the inclusion criteria and were used. Tecovirimat, known as TPOXX or ST-246, is an antiviral drug indicated for smallpox infection whereas brincidofovir inhibits the viral DNA polymerase after incorporation into viral DNA. The ability of tecovirimat in providing protection to poxvirus-challenged animals from death had been demonstrated in a number of animal studies. Non-inferior with regard to immunogenicity was reported for the live smallpox/monkeypox vaccine compared with a single dose of a licensed live smallpox vaccine. The trial involving the live vaccine showed a geometric mean titre of vaccinia-neutralizing antibodies post two weeks of the second dose of the live smallpox/monkeypox vaccine. Of note, up to the third generation of smallpox vaccines—particularly JYNNEOS and Lc16m8—have been developed as preventive measures for MPXV infection and these vaccines had been demonstrated to have improved safety compared to the earlier generations.

1. Introduction

The United States government has declared the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency on 5 August 2022 following a spike in cases. This ensues declaration on 23 July 2022 by the World Health Organization (WHO) of a highest emergency alert following a worldwide surge in cases. The monkeypox virus (MPXV) originated from orthopoxvirus genus, chordopoxvirinae subfamily, and poxviridae family [1]. The poxviridae family is often brick-shaped and consists of linear double-stranded DNA and has a lipoprotein envelope. The average size of an MPXV is 200–250 nm, which is considered relatively large [2,3]. Other viruses that belong in the same genus as MPXV include variola, cowpox, camelpox, and vaccinia viruses. Variola virus (VARV) causes smallpox disease which mirrors the clinical features of MPXV—typically headache, fatigue, rash, fever, and lesions which first appeared as macular, then developed into popular, then vesicular as well as pustular. The number of lesions experienced varies from one patient to another, ranging from a few to thousands per patient, and the development of lesions into pustular is linked to the severity of the disease. The only feature that distinguishes MPXV from smallpox is the presence of lymphadenopathy in patients infected with MPXV. The lymph nodes observed in patients with MPXV can be seen as enlarged, firm, and occasionally painful.

Complications were noted especially in unvaccinated patients and the conditions included secondary lung infection, bronchopneumonia, severe dehydration resulting from diarrhoea or vomiting, encephalitis, septicaemia and ocular infections [4,5]. The transmission of MPXV is believed to occur via skin-to-skin or face-to-face contact as well as in contact with infected objects such as clothes and beddings. Once infected, MPXV will undergo an incubation period lasting from 7 to 14 days. During this period, the virus replicates at the site of inoculation and begins spreading to the lymph nodes [6,7].

MPXV was first officially documented in an animal facility in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1958 when monkeys (Macaca fascicularis and Macaca Mulatta) supplied for polio vaccine research fell sick [8]. The first human case of Monkeypox infection was found in a child in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970. This child was first suspected to have smallpox [9]. From 1970 onwards, the cases continued to rise, and the infection was first spread to other African countries including Central African Republic, Cameroon, Cote D’Ivoire, Liberia Nigeria, Gabon, South Sudan, and Sierra Leone. From 1970 to 2020, nearly 29,000 suspected cases were recorded and there were over 1300 confirmed, probable, and/or possible cases of monkeypox. The countries that were most affected by this infection are the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Congo, and Central African Republic [10]. The first case outside African countries occurred in the Midwestern United States because of the importation of infected Gambian giant rats from Ghana. The virus then spread to co-housed prairie dogs that eventually spread to humans via close contact. About 53 cases were recorded during this time in the United States [11]. Another infection case recorded in Israel after a man travelled from Nigeria and went back to Israel in 2018 [12]. One similar monkeypox case occurred in Singapore in 2019. In this case, the man had also just travelled back from Nigeria [13].

From 1 January 2022 until 26 October 2022, approximately 77,000 laboratory confirmed cases of monkeypox were confirmed. Statistics show the highest number of monkeypox as 28,000, which were reported in the United States of America. This is followed by approximately 9000 cases in Brazil, 7317 cases in the United Kingdom (UK), 3662 cases in Germany and 3298 cases in Colombia [14].

As the specific treatment for monkeypox is still lacking, the rising outbreak of monkeypox has raised the concerns of many especially when the COVID-19 outbreak is still going on. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review of the preclinical studies focusing on the potential monkeypox treatment and prevention, particularly vaccines. We analysed the efficacy of potential treatments and vaccination that had been tested in preclinical trials in terms of providing protection from mortality, reducing severity of clinical symptoms, reducing the viral loads and increasing antibodies to fight against MPXV.

2. Methods

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The databases used for searching articles included Pubmed, Scopus and Cochrane, Medrxiv and Biorxiv and grey literature.

In Pubmed, the following search term was used; (monkey pox OR monkeypox OR “monkey?pox” OR/Abstract]). The filter feature was used to limit the number of results. The searches in Pubmed were limited to animals and English studies only. In Scopus, the search term used was (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“monkey pox”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“monkeypox”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“monkey?pox”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (Therapeutics OR prevention OR control OR vaccine OR treatment OR management)). The filter was also used and the results were limited to articles only. The search term “monkey pox” OR monkeypox OR “monkeypox virus” in Title Abstract Keyword AND Therapeutics OR prevention OR control OR vaccine OR treatment OR management in Title Abstract keyword was used in the Cochrane database. In both MedRxiv and Biorxiv, the following search terms were used; monkeypox and monkey pox.

The results from these databases were imported to Endnote X9 (Philadelphia, PA, United States) and duplicates were removed using the same app. Two investigators then independently screened the identified studies. Following removal of duplication, the remaining results were screened twice. The first screening was screening of titles and abstracts. The screening was performed based on the following exclusion criteria: (1) any articles that have no relation to monkeypox, (2) non-English studies, (3) studies that focus on other poxviruses, (4) reviews, and (5) any studies that are not accessible. Once the results were narrowed down, full-text screening was performed. Additional exclusion criteria were added during the second screening; any studies that provide lack of information or data of interest, which may also indicate high risk of bias, were removed. Data extraction of the studies was also done by all investigators independently.

With the remaining studies, they were summarised in tables according to types of treatments and vaccinations. The headings included in the table are types of samples (the types of animals or cells), intervention used with its dose and regimen, the comparison treatment or drug, method, and outcomes, which include the variables being examined.

3. Results

Study Selection

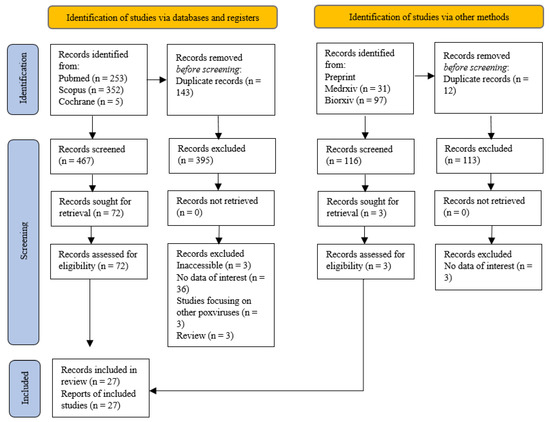

The number of results produced from the mentioned search terms for each database were recorded in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). A total of 467 results from registered databases and 116 from grey literature databases were screened. Of these results, 72 studies from registered databases and 3 grey literature studies underwent full-text screening for eligibility. In this systematic review, a total of 27 articles were eligible according to the inclusion criteria and were used. None of the studies from grey literature databases were eligible and a few eligible studies from the Cochrane databases were duplicates with those from Pubmed and Scopus.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

The table of evidence was prepared according to types of treatments: Tecovirimat (Table 1 and Table 2), Brincidofovir (Table 3 and Table 4), vaccines—IMVAMUNE, Vaccinia virus-immunoglobulin (VIG), ACAM2000, LC16m8, recombinant bovine herpesvirus 4 (BoHV-4), smallpox vaccine, DNA/HIV vaccines and Modified Vaccine Ankara (MVA) (Table 5 and Table 6), combination of treatments—cidofovir and Dryvax (Table 7 and Table 8) and other potential therapeutic agents (Table 9 and Table 10). The information included in the tables involve the type of samples, intervention used, comparison treatment, method and outcome measures and the corresponding findings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Tecovirimat (or ST-246) tested in preclinical studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Tecovirimat (or ST-246) tested in preclinical studies (Outcome measures).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Brincidofovir tested in preclinical studies.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Brincidofovir tested in preclinical studies (Outcome measures).

Table 5.

Characteristics of vaccines tested in preclinical studies.

Table 6.

Characteristics of vaccines tested in preclinical studies (Outcome measures).

Table 7.

Characteristics of treatment combination tested in preclinical studies.

Table 8.

Characteristics of treatment combination tested in preclinical studies (Outcome measures).

Table 9.

Characteristics of other potential therapeutic treatments tested in preclinical studies.

Table 10.

Characteristics of other potential therapeutic treatments tested in preclinical studies (Outcome measures).

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficacy and Safety of Treatments and Vaccines

4.1.1. Tecovirimat

Tecovirimat is an antiviral drug, which also goes by the branded name TPOXX and code name ST-246. As previously mentioned, tecovirimat was first FDA-approved for the treatment of smallpox in 2018 but had been recently approved by the European Medicines Agency as treatment of monkeypox disease [6,42]. This antiviral drug was firstly identified in 2002 through a high-throughput screening and has been shown to have efficacy against several other orthopoxviruses besides variola and MPXV, namely cowpox, rabbitpox, ectromelia and vaccinia virus [16,43,44]. Tecovirimat acts by inhibiting VP37 protein. All members of the orthopoxvirus genus are believed to encode this protein. Inhibition of this protein will prevent VP37 from interacting with GTPase and TIP47 which consequently blocks the necessary enveloped virions from being formed [45,46]. The efficacy of tecovirimat against MPXV had been shown in several preclinical studies, including seven animal studies and one in-vitro study, as summarised in Table 1. In the reported animal studies, tecovirimat had been demonstrated to reduce the mortality of MPXV-challenged animals with at least a 90% survival rate [15,16,17,22]. However, the efficacy in preventing mortality was seen to decrease in animals with delayed treatment post-challenge [22]. A similar pattern for clinical symptoms and viral loads was seen in the studies. Untreated animals were more likely to exhibit higher viral loads and more severe clinical symptoms including lethargy, lack of appetite, respiratory distress, lesions, high temperature, weight loss, nasal discharge and respiratory failure and as for treated animals, the animals experienced mild symptoms and lower viral loads [15,17,18,20,21]. In the Huggins et al study, the tecovirimat-treated animals experienced no lesions at all. Animals receiving earlier treatment post-infection had been shown to manifest milder symptoms compared to animals receiving delayed treatment [15]. The minimum effective dose for reducing viral loads and lesions was recorded at 10 mg/kg in monkeys which is comparable to 400 mg of tecovirimat in humans [16,20].

4.1.2. Brincidofovir

Hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir (HDP-CDV) or CMX001, famously known as Brincidofovir (BCV), is an alkoxyalkyl lipid ester conjugate of cidofovir (CDV). Post intravenous administration, only a very small amount of the drug reaches the kidney as it not largely taken up by transporters, hence, limiting the risk of nephrotoxicity unlike CDV [47,48]. BCV has an effect against double-stranded DNA viruses and exerts its antiviral effect by penetrating the infected cells upon administration. The drug will then be cleaved to CDV and phosphorylated to form cidofovir diphosphate, an active metabolite. This metabolite, in turn, prevents DNA polymerization by competing with deoxycytosine-5-triphosphate (dCTP) for viral DNA polymerase. This eventually disrupts viral replication [49]. BCV was first indicated for smallpox treatment in both paediatrics and adults with a dosage of 200 mg once weekly for 2 doses for those with 48 kg or above. However, it has now been under consideration to use against monkeypox infection [50,51,52]. BCV had also been shown to have positive outcomes in previous animal studies testing against several poxviruses [53,54,55]. In an MPXV-challenged animal study, the plasma concentration of BCV was analysed at different doses; 5 and 20 mg/kg and was tested with single and repeated administration. The plasma concentration was found to fall below the limit of quantification (BLQ) after 24 h (5 mg/kg dose) and 36 h (20 mg/kg) for single dose. Similar results were recorded for multiple doses of 5 mg/kg, but the concentration fell below BLQ by 48 h for dose of 20 mg/kg. In the same study, the efficacy of this drug was assessed by observing the mortality rate and clinical signs of MPXV-challenged black-tailed prairie dogs. A trend can be observed on the survival rate. Animals administered BCV were shown to have a delay in mortality in comparison to animals receiving treatment on the day of challenge and one day post-challenge. However, the highest rate of survival achieved was only 57%, which suggests a lack of efficacy of BCV in the treatment of MPXV. Despite the low efficacy, Hutson CL et al. suggested that BCV may be effective if given in combination with another drug such as tecovirimat [23].

4.1.3. Monkeypox Virus Vaccines

Dryvax, one of the first-generation smallpox vaccines, was made by replicating the vaccinia virus. This vaccine was shown to have promising results against this virus and was used to eradicate smallpox [56,57]. In the Zielenski Rj et al. study using the cynomolgus macaques model, the vaccine used involved the Wyeth strain. The vaccine was integrated with varying interleukins, IL-2 and IL-15, but Wyeth/IL-2 vaccines were served as the comparison group together with the Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA)-vaccinated group. In the study, Wyeth/IL-2 and MVA-vaccinated groups exhibited milder clinical symptoms compared to the Wyeth/IL-15 group. The Wyeth/IL-15 group had also shown to have a delay in healing. The vaccinia plaque reduction neutralizing antibody titres (PRNT 80%) were observed in the same study and MVA-treated animals were shown to have 4-fold compared to the other groups at 6 weeks post-vaccination, which implies poor efficacy of integrated Wyeth strains smallpox vaccines [29]. In other animal studies by Buchman et al., the Dryvax vaccine was used as a comparison group to a smallpox vaccine with A33, B5, L, A27 (ABL) and aluminium hydroxide (ABLA). The outcome of the study indicated favourable results of Dryvax against MPXV by which the mortality rate was seen to be reduced to zero and significantly lower viral loads in comparison to the negative control group (p < 0.05) [30]. Despite the efficacy, this vaccine was found to be linked with severe, rare side effects including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, myocarditis, pericarditis, eczema vaccinatum, encephalitis, progressive vaccinia and occasionally death. Hence, this encouraged the development of smallpox second- and third-generation vaccines [58].

ACAM2000, is live vaccinia virus vaccine derived from cell cultures in Vero Cells and is considered as a second-generation smallpox vaccine. On 31 August 2007, ACAM2000 was licensed by the FDA for individuals with high risk of smallpox infection [59]. The efficacy of this vaccine in overcoming the high mortality rate and infection severity had been demonstrated in several animal studies involving prairie dogs and cynomolgus monkeys [25,28,31]. In one of the studies, there was no reported significant change in blood or chemistry parameters within the first 15 days after vaccination. This was consistent with the pathological symptoms observed in the immunised models, which was in contrast with the control group. Apart from that, the mortality rate was seen to be reduced with further delays in receiving vaccination post-challenge, but no statistically significant survival benefit was calculated. This study used a single dose of 1 × 105 PFU of ACAM2000 [31]. In another study, the survival rate of models reached 100% and low levels of viremia was detected with the booster dose. However, some clinical symptoms were present including lesions. Based on the results, it was suggested that the prime-boost approach may be useful in obtaining an optimal effect of the vaccine as a high level of antibodies were detected following the booster dose [28]. This vaccine is said to have a similar profile as Dryvax and the efficacy is as good as the first-generation. However, there are still reported adverse effects which may induce the risk of developing complications in vaccinated individuals [31,58,60,61].

Examples of third-generation smallpox vaccines are IMVAMUNE and LC16m8 vaccines. IMVAMUNE also goes by different marketing names; Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN; Germany), JYNNEOS (the United States) and IMVANEX (the European Union). Unlike the first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines, IMVAMUNE had no reported complications linked with the first-generation vaccines. Hence, it is currently developed as an effective and safe vaccine in the prevention of smallpox and other poxviruses. However, higher doses may be required for IMVAMUNE [28,30]. This vaccine was manufactured based on a highly attenuated strain of vaccinia virus—MVA virus—which underwent multiple changes including mutations and deletions to lose its capacity to replicate efficiently in most mammalian cells and humans in order to be used in the IMVAMUNE vaccine [38]. The efficacy of this vaccine against MPXV had been tested in a number of animal studies [25,28]. One of the studies demonstrated that the prairie dog models that had been immunised with IMVAMUNE one day post-infection had shown to have reduced weight loss by Day 16 post-challenge in comparison to unvaccinated group, but no statistically significant difference was calculated (p > 0.05). Though, animals that had been administered with IMVAMUNE three days post-challenge recorded greater weight loss than the control group by Day 16 post-infection, which questions the vaccine’s ability in preventing mortality in delayed immunisation. As for comparing lesion counts, the lesion counts in one-day post-challenge IMVAMUNE-vaccinated animals were found to be significantly lower than the control group (p < 0.05) [25]. In a different study, all but 2 vaccinated cynomolgus macaques survived by day 11 post-infection. All immunised animals were seen to have increased in body weight by day 14 post-challenge. Milder clinical symptoms such as depression and dyspnea were observed in dead vaccinated animals compared to the control group. However, other surviving animals exhibited little to no clinical signs [28]. In a 1970s study in Germany, MVA vaccines were tested on approximately 120,000 people together with the Lister vaccine and there were no serious adverse reactions reported [62].

The LC16m8 vaccine, a highly attenuated vaccine and another example of third-generation smallpox vaccines, was initially developed using the Lister strain of smallpox vaccine in rabbit kidney cells under low temperature conditions in Japan in the 1970s [63]. The efficacy of this vaccine in providing protection and reducing the infection severity in animal models had been demonstrated. In the studies, no animals succumbed to infection and had shown little to no clinical signs of MPXV infection. Any signs developed were found the be milder than the control groups [26,64]. In the Iizuka et al., study, they signified that LC16m8 has the capability to provide long-term immunity against the MPXV virus in Macaca fascicularis species. However, the duration of the immunity was still unclear. Hence, further investigations are required to determine the duration [26].

4.1.4. Other Potential Therapeutic Agents

In the Mucker et al. study in 2018, they evaluated the use of monoclonal antibodies in the prophylaxis of severe MPXV infection. The particular antibodies used were 7D11 and c8A, which were produced by BioFactura [40]. These antibodies target the mature virion (by C7D11) and extracellular virion (by c8A), and eventually inhibit further action of the virions [65]. The study demonstrated that these antibodies are effective in providing protection and reducing the signs and symptoms of the disease. A total of 2 out of 3 treated animals survived and exhibited no symptoms, and it was found that C7D11 was capable of decreasing the viral load by ~90% with high dose ->1250 PFU/mL [40]. However, since the sample for this study is very small (n = 3), there is less reliability on the results and different outcomes may be projected with bigger samples. It is also noteworthy that this is the first study to use marmosets as the model for the MPXV study, hence requiring further varying studies to evaluate the use of monoclonal antibodies as prophylactic treatment for MPXV in determining the doses and immunologic responses induced by these antibodies.

Interferon-Beta (IFN-β) was another potential agent and FDA approved this drug for multiple sclerosis. IFN-β acts by stimulating the production of IFN-stimulated genes. This stimulation of these genes will activate apoptosis, allowing the active action of macrophages and natural killer cells to inhibit the synthesis of proteins. The major histocompatibility complex-1/II expression on the surface of antigen presenting cells will also be upregulated because of these genes [66]. This agent was tested by Johnston et al., 2012. In their in-vitro study, IFN-β was assessed for its ability to inhibit the production and spread of MPXV in monolayers of HeLa cells and normal derma fibroblasts. For the outcomes, it was shown that 2000 U/mL of IFN-β was capable of inhibiting the spread of MPXV for a minimum 91% in all cells. This efficacy is thought to be caused by one molecule, MxA, which was found to have an antiviral activity against a number of RNA viruses such as influenza and measles viruses. However, the exact mode of action of MxA against MPXV is unclear and requires further studies [41].

4.2. Limitations of Reported Studies

4.2.1. Animal Models

The ideal characteristics of an animal model to be used in preclinical studies should be those that are similar in a number of traits; possess similar clinical features, disease course, and mortality as humans, capable of mimicking similar transmission of the pathogen as to humans, and having a similar dosage of drugs to produce similar effects to that in humans. In addition, a model is considered ideal if a large number of animals can be provided in the research. However, varying animal models were used in the reported studies in the tables above with monkeys being the most common one used. The distinct traits or characteristics of different animals such as pharmacokinetics or histopathological changes may have contributed to varying outcomes of the studies [67]. Hence, it is unfair to compare two studies with different animals used despite involving the same poxvirus. In the studies above, the list of animal models includes monkeys (Macaca fascicularis, Macaca Mulatta, crab-eating macaques, Rhesus macaques, and marmosets), prairie dogs, ground squirrels, and mice.

Among the animals mentioned above, humans share the most similar physiology with monkeys. These animals exhibit an identical duration of onset and clinical features of disease as humans when challenged with MPXV via IV or aerosol route. Hence, a number of parameters can be used as a reference or comparison i.e., temperature, vital signs etc. However, there are a few limitations that should be noted. Monkey models require a high dose of virus to develop a symptom in comparison to other models (106~107 PFU of MPXV for monkeys). Although these models can be inoculated via aerosol or the intratracheal route, they still do not entirely mimic all the natural transmission routes of infection in humans [68,69]. The types of monkey models used in studies should also be taken under consideration as only certain species are vulnerable to MPX infection and varying species may have a different disease onset and severity. For instance, the outbreak in the US in 1959 was first spread by Macaca fascicularis and Macaca mulatta. These animals were co-housed with another monkey species, African Chlorocebus Aethiops, who surprisingly did not exhibit any of the MPXV symptoms at all [70]. This explains that the species factor could have contributed to varying outcomes in studies. Eric et al. (2018) also outlined the possibility of the effect of gender on the disease’s severity and symptoms as they observed that female marmosets had fewer viremia and oral shedding and developed higher number of lesions compared to male marmosets [40]. Thus, it is rather challenging to correlate the efficacy and safety of drugs in the models to in humans.

Rodents require a dose of virus that is far lower than the amount needed in monkey models, ranging from 12,000~32,000 PFU of MPXV. The inoculation routes for MPXV challenge for these small animals were through intranasal, intraperitoneal or cutaneous, which slightly but not entirely mimic the transmission of virus as in humans [22,71,72,73]. However, ground squirrels and prairie dogs may not be the ideal models for these studies as the availability of these animals is rather restricted due to a low reproductivity rate. Even if they are available, they are likely to be captured from the wild. Hence, there is a possibility of these animals being exposed to other pathogens and unknown external or internal factors which could have led to the misinterpretation of the outcomes [69]. Furthermore, ground squirrel models experienced only a few similar symptoms as the ones developed in humans. Thus, limited parameters can be used as reference. In addition to that, a limited species of mice can be used as a model in MPXV studies as a number of certain strains of these rodents were not vulnerable to this infection. Immunocompromised mice developed symptoms when exposed to MPXV but this model does not mimic the natural infection of MPXV. STAT1(−) mice, however, were found to have high sensitivity to this infection. Therefore, they were used in studies testing drug efficacy [74,75].

4.2.2. Monkeypox Virus Strains

Based on the severity of disease and geographical origin, MPXV strains were categorised into two clades; Congo Basin (CB) and West African (WA) MPXV [76]. It is important to note that the severity of disease that a strain caused may greatly affect the outcome of the studies. Both strains resulted in different disease severity and CB had been linked to higher severity. In the Hutson et al. (2009) study, C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were challenged intranasally (IN) or subcutaneously in the footpad (FP) with 105 PFU of either WA or CB MPXV strain. CB MPXV-challenged mice FP developed oedema on day 6 p.i. on BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, but greater oedema was identified in BALB/c mice. Severe swellings were noticed in two BALB/c and one C57BL/6 mice in the following day and the oedema resolved by day 13 p.i. Throughout the study, only one BALB/c mice had weight loss, as much as 7.3% of its initial mass. As for WA MPXV-challenged FP mice, mild oedema developed on day 7 p.i. This oedema was less severe in comparison to CB MPXV FP mice and the oedema completely resolved by day 9 or 11 p.i. Unlike CB MPXV FP animals, none of the WA MPXV FP mice lost any weight. CB MPXV IN-challenged animals. Ruffled fur was observed in four BALB/c mice and weight loss was noted in most of the inoculated animals, ranging between 3 to 19% of initial weight. Other than that, no other signs developed. In contrast, no observable morbidity signs were seen in WA MPXV IN animals [77]. In a different study with similar aims, prairie dogs were used as models. In this study, 104 PFU of either WA or CB MPXV strains were introduced to the animals via intradermal via scarification (ID) or IN. Animals challenged with CB MPXV ID or IN had a recorded rise in temperature, which was calculated as significantly higher than WA MPXV-challenged animals. Lesions started to appear on CB-MPXV animals by day 6 p.i. and on WA-MPXV animals by day 6–9 p.i. By day 15 p.i., about 3 CB MPXV prairie dogs succumbed to infection (two ID and one IN) and none for WA MPXV prairie dogs. The DNA of MPXV was also detected in swabs in the range of day 6–21 p.i. for MPXV ID prairie dogs, and on day 3–21 and day 6–18 p.i. for WA MPXV IN and CB MPXV in prairie dogs, respectively [71]. According to these studies, it is evident that CB MPXV strain is more virulent in comparison to the WA strain as animals tend to have a higher mortality rate and severity of clinical manifestations of this disease. The variability of these strains may have given rise to a distinct impact on the end results of these studies.

4.3. Clinicians and Researchers Notes

In terms of treatment of monkeypox, no antiviral treatment specifically for MPXV is available yet. However, tecovirimat, known as TPOXX or ST-246, is an antiviral drug indicated for smallpox infection and had been approved by the European Medicines Agency for MPXV infection in January 2022. Apart from tecovirimat, an anti-smallpox drug brincidofovir, also known as CMX001 or Tembexa, is also under the consideration for use as treatment for monkeypox infection [51,52]. Tecovirimat inhibits a specific protein in orthopoxviruses, namely p37, which is an essential protein for producing virions of poxviruses [78,79]. On the other hand, brincidofovir inhibits the viral DNA polymerase after incorporation into viral DNA [80]. The ability of tecovirimat in providing protection to poxvirus-challenged animals from death had been demonstrated in a number of animal studies [44,81]. Brincidofovir had also been shown to be effective against orthopoxviruses [46]. However, the issue that comes with these drugs is that they are yet to be approved by the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) specifically for the treatment of monkeypox. We also included the limitation of the reported studies in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 which MPXV researchers could pinpoint the appropriate animal model and virus strain to be used as reference for their future research.

With the resurgence of MPXV infection and a lack of efficacious and safe drugs currently available to tackle the infection, developing treatments and preventive measures for this disease has become a critical aspect to look further into. From this review, we have learned that up to the third generation of smallpox vaccines, particularly JYNNEOS and Lc16m8, have been developed as preventive measures for MPXV infection. These vaccines had been demonstrated to have improved safety compared to the earlier generations of smallpox vaccines, which had been reported to cause complications in those receiving these vaccines. Clinicians need to be precautious as the vaccines may have less efficacy under special circumstances. In this case, more focus should be directed in developing anti-viral drugs to manage and control MPXV infection, especially in those in high-risk groups, particularly those who are under immunocompromised condition.

Strength and Limitation of this Review

Due to the lack of feasibility of clinical trials and the unethical nature of introducing MPXV to human subjects, efficacy is based on animal models which we have included all relevant preclinical studies related to treatment and prevention of monkeypox.

Although this review is inclusive with all preclinical studies from the early 2000s, it is important to note that older studies may have used old preclinical guidelines, thus, not consistent with the current guidelines for preclinical studies.

5. Conclusions

To date, at the global scene, no approved treatment or vaccine for monkeypox is available. While the effectiveness of repurposed drugs in treating MPXV among human has not been evaluated, potential treatment benefit based on preclinical studies including animal efficacy data could be particularly useful. Third-generation smallpox vaccines, particularly JYNNEOS and Lc16m8, have been developed as preventive measures for MPXV infection and these vaccines had been demonstrated to have improved safety compared to the earlier generations of smallpox vaccines. Furthermore, tecovirimat has been shown to be effective against various orthopoxviruses in multiple animal challenge models. The limitations of the reported studies, particularly from the aspects of animal models and MPXV strains indicated that monkeys may be the ideal model for testing safety and efficacy of drugs for MPXV infection. These models not only reflect similar routes of transmissions as in humans but also identical duration of course and clinical manifestations. As for the MPXV strain, using the WA MPXV strain may not entirely represent the real-life condition as it is less virulent hence this strain is less likely to cause a wide spread of infection. Moreover, the severity it caused is milder. Hence, the CB MPXV strain would be preferred as it may help in providing the optimal outcomes of drugs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S., N.K., A.H. and L.C.M. methodology, N.K., A.H. and L.C.M.; formal analysis; N.S., N.K., A.H. and L.C.M., resources; L.C.M., data curation; N.S., B.-H.G. and L.C.M.; Supervision: N.K., A.H. and L.C.M.; Funding acquisition: N.K., A.H. and L.C.M.; writing original draft preparation, N.S. and L.C.M.; writing, review and editing, B.-H.G., S.F.Y., A.H. and L.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Moore, M.; Zahra, F. Monkeypox. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574519/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Kugelman, J.R.; Johnston, S.C.; Mulembakani, P.M.; Kisalu, N.; Lee, M.S.; Koroleva, G.; McCarthy, S.E.; Gestole, M.C.; Wolfe, N.D.; Fair, J.N.; et al. Genomic variability of monkeypox virus among humans, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakunle, E.; Moens, U.; Nchinda, G.; Okeke, M.I. Monkeypox Virus in Nigeria: Infection Biology, Epidemiology, and Evolution. Viruses 2020, 12, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCollum, A.M.; Damon, I.K. Human monkeypox. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezek, Z.; Szczeniowski, M.; Paluku, K.M.; Mutombo, M. Human monkeypox: Clinical features of 282 patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 156, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Monkeypox: What You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/monkeypox--what-you-need-to-know?gclid=Cj0KCQjw2_OWBhDqARIsAAUNTTE0TModmdBO6QgSCjhMvugBad0K_mlmC3NmymgH9bF79gISnAguNxQaApUeEALw_wcB (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Hutson, C.L.; Carroll, D.S.; Gallardo-Romero, N.; Drew, C.; Zaki, S.R.; Nagy, T.; Hughes, C.; Olson, V.A.; Sanders, J.; Patel, N.; et al. Comparison of Monkeypox Virus Clade Kinetics and Pathology within the Prairie Dog Animal Model Using a Serial Sacrifice Study Design. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 965710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, P.V.; Andersen, E.K.; Petersen, K.B.; Birch-Andersen, A. A pox-like disease in cynomolgus monkeys. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1959, 46, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladnyj, I.D.; Ziegler, P.; Kima, E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull. World Health Organ. 1972, 46, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multistate outbreak of monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2003, 23, 537–540. [Google Scholar]

- Erez, N.; Achdout, H.; Milrot, E.; Schwartz, Y.; Wiener-Well, Y.; Paran, N.; Politi, B.; Tamir, H.; Israely, T.; Weiss, S.; et al. Diagnosis of imported monkeypox, Israel, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 980–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.E.F.; Ng, O.T.; Ho, Z.J.M.; Mak, T.M.; Marimuthu, K.; Vasoo, S.; Yeo, T.W.; Ng, Y.K.; Cui, L.; Ferdous, Z.; et al. Imported Monkeypox, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1826–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Monkeypox Outbreak: Global Trends. Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/ (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Russo, A.T.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Brasel, T.L.; Baker, R.O.; Cawthon, A.G.; Reynolds, E.; Bailey, T.; Kuehl, P.J.; Sugita, V.; Agans, K.; et al. Effects of treatment delay on efficacy of tecovirimat following lethal aerosol monkeypox virus challenge in cynomolgus macaques. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosenbach, D.W.; Honeychurch, K.; Rose, E.A.; Chinsangaram, J.; Frimm, A.; Maiti, B.; Lovejoy, C.; Meara, I.; Long, P.; Hruby, D.E. Oral Tecovirimat for the Treatment of Smallpox. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhanu, A.; Prigge, J.T.; Silvera, P.M.; Honeychurch, K.M.; Hruby, D.E.; Grosenbach, D.W. Treatment with the smallpox antiviral tecovirimat (ST-246) alone or in combination with ACAM2000 vaccination is effective as a postsymptomatic therapy for monkeypox virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4296–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.K.; Self, J.; Weiss, S.; Carroll, D.; Braden, Z.; Regnery, R.L.; Davidson, W.; Jordan, R.; Hruby, D.E.; Damon, I.K. Effective antiviral treatment of systemic orthopoxvirus disease: ST-246 treatment of prairie dogs infected with Monkeypox virus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 9176–9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.K.; Olson, V.A.; Karem, K.L.; Jordan, R.; Hruby, D.E.; Damon, I.K. In vitro efficacy of ST246 against smallpox and monkeypox. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.; Goff, A.; Frimm, A.; Corrado, M.L.; Hensley, L.E.; Byrd, C.M.; Mucker, E.; Shamblin, J.; Bolken, T.C.; Wlazlowski, C.; et al. ST-246 antiviral efficacy in a nonhuman primate monkeypox model: Determination of the minimal effective dose and human dose justification. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, J.; Goff, A.; Hensley, L.; Mucker, E.; Shamblin, J.; Wlazlowski, C.; Johnson, W.; Chapman, J.; Larsen, T.; Twenhafel, N.; et al. Nonhuman primates are protected from smallpox virus or monkeypox virus challenges by the antiviral drug ST-246. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2620–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrana, E.; Jordan, R.; Hruby, D.E.; Mateo, R.I.; Xiao, S.Y.; Siirin, M.; Newman, P.C.; Travassos Da Rosa, A.P.A.; Tesh, R.B. Efficacy of the antipoxvirus compound ST-246 for treatment of severe orthopoxvirus infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 76, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, C.L.; Kondas, A.V.; Mauldin, M.R.; Doty, J.B.; Grossi, I.M.; Morgan, C.N.; Ostergaard, S.D.; Hughes, C.M.; Nakazawa, Y.; Kling, C.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of a Potential Smallpox Therapeutic, Brincidofovir, in a Lethal Monkeypox Virus Animal Model. mSphere 2021, 6, e00927-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; D’Angelo, J.; Buller, R.M.; Smee, D.F.; Lantto, J.; Nielsen, H.; Jensen, A.; Prichard, M.; George, S.L. A human recombinant analogue to plasma-derived vaccinia immunoglobulin prophylactically and therapeutically protects against lethal orthopoxvirus challenge. Antivir. Res. 2021, 195, 105179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon Keckler, M.; Salzer, J.S.; Patel, N.; Townsend, M.B.; Akazawa, Y.J.; Doty, J.B.; Gallardo-Romero, N.F.; Satheshkumar, P.S.; Carroll, D.S.; Karem, K.L.; et al. Imvamune® and acam2000® provide different protection against disease when administered postexposure in an intranasal monkeypox challenge prairie dog model. Vaccines 2020, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, I.; Ami, Y.; Suzaki, Y.; Nagata, N.; Fukushi, S.; Ogata, M.; Morikawa, S.; Hasegawa, H.; Mizuguchi, M.; Kurane, I.; et al. A single vaccination of nonhuman primates with highly attenuated smallpox vaccine, LC16m8, provides long-term protection against monkeypox. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 70, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, V.; Parker, S.; Jacca, S.; Crump, R.W.; Doronin, K.; Hembrador, E.; Pompilio, D.; Tebaldi, G.; Estep, R.D.; Wong, S.W.; et al. BoHV-4-based vector single heterologous antigen delivery protects STAT1(−/−) mice from monkeypoxvirus lethal challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, G.J.; Graham, V.A.; Bewley, K.R.; Tree, J.A.; Dennis, M.; Taylor, I.; Funnell, S.G.P.; Bate, S.R.; Steeds, K.; Tipton, T.; et al. Assessment of the protective effect of imvamune and Acam2000 vaccines against aerosolized monkeypox virus in cynomolgus macaques. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7805–7815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, R.J.; Smedley, J.V.; Perera, P.Y.; Silvera, P.M.; Waldmann, T.A.; Capala, J.; Perera, L.P. Smallpox vaccine with integrated IL-15 demonstrates enhanced in vivo viral clearance in immunodeficient mice and confers long term protection against a lethal monkeypox challenge in cynomolgus monkeys. Vaccine 2010, 28, 7081–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, G.W.; Cohen, M.E.; Xiao, Y.; Richardson-Harman, N.; Silvera, P.; DeTolla, L.J.; Davis, H.L.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Cohen, G.H.; Isaacs, S.N. A protein-based smallpox vaccine protects non-human primates from a lethal monkeypox virus challenge. Vaccine 2010, 28, 6627–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, K.A.; Parkinson, C.V.; Morefield, S.I.; Davenport, R.; Nichols, R.; Monath, T.P. Clonal vaccinia virus grown in cell culture fully protects monkeys from lethal monkeypox challenge. Vaccine 2008, 26, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, P.; Earl, P.L.; Americo, J.L.; Sharma, S.; Wyatt, L.S.; Edghill-Spano, Y.; Chennareddi, L.S.; Silvera, P.; Moss, B.; Robinson, H.L.; et al. DNA/MVA HIV-1/AIDS vaccine elicits long-lived vaccinia virus-specific immunity and confers protection against a lethal monkeypox challenge. Virology 2007, 366, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, P.L.; Americo, J.L.; Wyatt, L.S.; Anne Eller, L.; Montefiori, D.C.; Byrum, R.; Piatak, M.; Lifson, J.D.; Rao Amara, R.; Robinson, H.L.; et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara provides durable protection against disease caused by an immunodeficiency virus as well as long-term immunity to an orthopoxvirus in a non-human primate. Virology 2007, 366, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saijo, M.; Ami, Y.; Suzaki, Y.; Nagata, N.; Iwata, N.; Hasegawa, H.; Ogata, M.; Fukushi, S.; Mizutani, T.; Sata, T.; et al. LC16m8, a highly attenuated vaccinia virus vaccine lacking expression of the membrane protein B5R, protects monkeys from monkeypox. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5179–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heraud, J.M.; Edghill-Smith, Y.; Ayala, V.; Kalisz, I.; Parrino, J.; Kalyanaraman, V.S.; Manischewitz, J.; King, L.R.; Hryniewicz, A.; Trindade, C.J.; et al. Subunit recombinant vaccine protects against monkeypox. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 2552–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stittelaar, K.J.; Van Amerongen, G.; Kondova, I.; Kuiken, T.; Van Lavieren, R.F.; Pistoor, F.H.M.; Niesters, H.G.M.; Van Doornum, G.; Van Der Zeijst, B.A.M.; Mateo, L.; et al. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara protects macaques against respiratory challenge with monkeypox virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7845–7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, J.W.; Thompson, E.; Wilhelmsen, C.; Zimmerman, M.; Ait Ichou, M.; Steffen, S.E.; Schmaljohn, C.S.; Schmaljohn, A.L.; Jahrling, P.B. Smallpox DNA Vaccine Protects Nonhuman Primates against Lethal Monkeypox. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 4433–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earl, P.L.; Americo, J.L.; Wyatt, L.S.; Eller, L.A.; Whitbeck, J.C.; Cohen, G.H.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Hartmann, C.J.; Jackson, D.L.; Kulesh, D.A.; et al. Immunogenicity of a highly attenuated MVA smallpox vaccine and protection against monkeypox. Nature 2004, 428, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Huang, D.; Fortman, J.; Wang, R.; Shao, L.; Chen, Z.W. Coadministration of cidofovir and smallpox vaccine reduced vaccination side effects but interfered with vaccine-elicited immune responses and immunity to monkeypox. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucker, E.M.; Wollen-Roberts, S.E.; Kimmel, A.; Shamblin, J.; Sampey, D.; Hooper, J.W. Intranasal monkeypox marmoset model: Prophylactic antibody treatment provides benefit against severe monkeypox virus disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.C.; Lin, K.L.; Connor, J.H.; Ruthel, G.; Goff, A.; Hensley, L.E. In vitro inhibition of monkeypox virus production and spread by Interferon-β. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Approves First Smallpox-Indicated Treatment, SIGA’s TPOXX. Available online: https://www.genengnews.com/topics/drug-discovery/fda-approves-first-smallpox-indicated-treatment-sigas-tpoxx/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Grosenbach, D.W.; Jordan, R.; Hruby, D.E. Development of the small-molecule antiviral ST-246 as a smallpox therapeutic. Future Virol. 2011, 6, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucker, E.M.; Goff, A.J.; Shamblin, J.D.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Damon, I.K.; Mehal, J.M.; Holman, R.C.; Carroll, D.; Gallardo, N.; Olson, V.A.; et al. Efficacy of tecovirimat (ST-246) in nonhuman primates infected with variola virus (Smallpox). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 6246–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Product Information: TPOXX(R) Oral Capsules, Intravenous Injection, Tecovirimat Oral Capsules, Intravenous Injection; SIGA Technologies Inc. (per FDA): Corvallis, OR, USA, 2022.

- Lanier, R.; Trost, L.; Tippin, T.; Lampert, B.; Robertson, A.; Foster, S.; Rose, M.; Painter, W.; O’Mahony, R.; Almond, M.; et al. Development of CMX001 for the Treatment of Poxvirus Infections. Viruses 2010, 2, 2740–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostetler, K.Y.; Beadle, J.R.; Trahan, J.; Aldern, K.A.; Owens, G.; Schriewer, J.; Melman, L.; Buller, R.M. Oral 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-benzyl-sn-glycero-3-cidofovir targets the lung and is effective against a lethal respiratory challenge with ectromelia virus in mice. Antivir. Res. 2007, 73, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tippin, T.K.; Morrison, M.E.; Brundage, T.M.; Momméja-Marin, H. Brincidofovir Is Not a Substrate for the Human Organic Anion Transporter 1: A Mechanistic Explanation for the Lack of Nephrotoxicity Observed in Clinical Studies. Ther. Drug Monit. 2016, 38, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem Compound Summary for CID 483477, Brincidofovir. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Brincidofovir (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- FDA. Approved Drug Products: Tembexa (brincidofovir) for oral administration. In Chimerix; Chimerix: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Monkeypox—Questions and Answers. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/monkeypox?gclid=Cj0KCQjw2_OWBhDqARIsAAUNTTFk-3U7VjavJRwwI2eABaaTb1ggEnO_Uaqln6Cpb1KYSonkU3DyBaEaAm7WEALw_wcB (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH). Monkeypox Treatment. Available online: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/monkeypox-treatment (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Foster, S.A.; Parker, S.; Lanier, R. The Role of Brincidofovir in Preparation for a Potential Smallpox Outbreak. Viruses 2017, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, V.A.; Smith, S.K.; Foster, S.; Li, Y.; Lanier, E.R.; Gates, I.; Trost, L.C.; Damon, I.K. In vitro efficacy of brincidofovir against variola virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 5570–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.D.; Adams, M.M.; Wallace, G.; Burrage, A.M.; Lindsey, S.F.; Smith, A.J.; Swetnam, D.; Manning, B.R.; Gray, S.A.; Lampert, B.; et al. Efficacy of CMX001 as a post exposure antiviral in New Zealand White rabbits infected with rabbitpox virus, a model for orthopoxvirus infections of humans. Viruses 2011, 3, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, A. Smallpox vaccination and bioterrorism with pox viruses. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003, 26, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Wright, M.E. Progressive vaccinia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, W.; Mordmueller, B.G. Vaccines for preventing smallpox. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 2007, Cd004913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.D.; Garman, P.M.; Hughes, H.; Yacovone, M.A.; Collins, L.C.; Fegley, C.D.; Lin, G.; DiPietro, G.; Gordon, D.M. Enhanced safety surveillance study of ACAM2000 smallpox vaccine among US military service members. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5541–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.N.; Kennedy, J.S. ACAM2000: A newly licensed cell culture-based live vaccinia smallpox vaccine. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2008, 17, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, A.R.; Davis, M.M.; Freed, G.L. Expected adverse events in a mass smallpox vaccination campaign. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2002, 5, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.S.; Greenberg, R.N. IMVAMUNE: Modified vaccinia Ankara strain as an attenuated smallpox vaccine. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2009, 8, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi-Nishimaki, F.; Suzuki, K.; Morita, M.; Maruyama, T.; Miki, K.; Hashizume, S.; Sugimoto, M. Genetic analysis of vaccinia virus Lister strain and its attenuated mutant LC16m8: Production of intermediate variants by homologous recombination. J. Gen. Virol. 1987, 68 Pt 10, 2705–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, M.; Ami, Y.; Suzaki, Y.; Nagata, N.; Iwata, N.; Hasegawa, H.; Ogata, M.; Fukushi, S.; Mizutani, T.; Iizuka, I.; et al. Diagnosis and assessment of monkeypox virus (MPXV) infection by quantitative PCR assay: Differentiation of Congo Basin and West African MPXV strains. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 61, 140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig, S.; Fogg, C.; Whitbeck, J.C.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Cohen, G.H.; Moss, B. Combinations of polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies to proteins of the outer membranes of the two infectious forms of vaccinia virus protect mice against a lethal respiratory challenge. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 13454–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, R.E.; Goodbourn, S. Interferons and viruses: An interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89 Pt 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, C.L.; Damon, I.K. Monkeypox Virus Infections in Small Animal Models for Evaluation of Anti-Poxvirus Agents. Viruses 2010, 2, 2763–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artenstein, A.W. New generation smallpox vaccines: A review of preclinical and clinical data. Rev. Med. Virol. 2008, 18, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.L.; Nichols, D.K.; Martinez, M.J.; Raymond, J.W. Animal models of orthopoxvirus infection. Vet. Pathol. 2010, 47, 852–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, R.M.; Prier, J.E.; Buchanan, R.S.; Creamer, A.A.; Fegley, H.C. Studies on a pox disease of monkeys. I. Pathology. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1960, 21, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hutson, C.L.; Olson, V.A.; Carroll, D.S.; Abel, J.A.; Hughes, C.M.; Braden, Z.H.; Weiss, S.; Self, J.; Osorio, J.E.; Hudson, P.N.; et al. A prairie dog animal model of systemic orthopoxvirus disease using west African and Congo Basin strains of Monkeypox virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesh, R.B.; Watts, D.M.; Sbrana, E.; Siirin, M.; Popov, V.L.; Xiao, S.Y. Experimental infection of ground squirrels (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus) with monkeypox virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1563–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.Y.; Sbrana, E.; Watts, D.M.; Siirin, M.; da Rosa, A.P.; Tesh, R.B. Experimental infection of prairie dogs with monkeypox virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabenow, J.; Buller, R.M.; Schriewer, J.; West, C.; Sagartz, J.E.; Parker, S. A mouse model of lethal infection for evaluating prophylactics and therapeutics against monkeypox virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3909–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.E.; Iams, K.P.; Meteyer, C.U.; Rocke, T.E. Comparison of monkeypox viruses pathogenesis in mice by in vivo imaging. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likos, A.M.; Sammons, S.A.; Olson, V.A.; Frace, A.M.; Li, Y.; Olsen-Rasmussen, M.; Davidson, W.; Galloway, R.; Khristova, M.L.; Reynolds, M.G.; et al. A tale of two clades: Monkeypox viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, C.L.; Abel, J.A.; Carroll, D.S.; Olson, V.A.; Braden, Z.H.; Hughes, C.M.; Dillon, M.; Hopkins, C.; Karem, K.L.; Damon, I.K.; et al. Comparison of West African and Congo Basin monkeypox viruses in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Pevear, D.C.; Davies, M.H.; Collett, M.S.; Bailey, T.; Rippen, S.; Barone, L.; Burns, C.; Rhodes, G.; Tohan, S.; et al. An orally bioavailable antipoxvirus compound (ST-246) inhibits extracellular virus formation and protects mice from lethal orthopoxvirus challenge. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 13139–13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L.; Vanderplasschen, A.; Law, M. The formation and function of extracellular enveloped vaccinia virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83 Pt 12, 2915–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R. Cidofovir Activity against Poxvirus Infections. Viruses 2010, 2, 2803–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalca, A.; Hatkin, J.M.; Garza, N.L.; Nichols, D.K.; Norris, S.W.; Hruby, D.E.; Jordan, R. Evaluation of orally delivered ST-246 as postexposure prophylactic and antiviral therapeutic in an aerosolized rabbitpox rabbit model. Antivir. Res. 2008, 79, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).