Abstract

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had devastating health and socio-economic impacts. Human activities, especially at the wildlife interphase, are at the core of forces driving the emergence of new viral agents. Global surveillance activities have identified bats as the natural hosts of diverse coronaviruses, with other domestic and wildlife animal species possibly acting as intermediate or spillover hosts. The African continent is confronted by several factors that challenge prevention and response to novel disease emergences, such as high species diversity, inadequate health systems, and drastic social and ecosystem changes. We reviewed published animal coronavirus surveillance studies conducted in Africa, specifically summarizing surveillance approaches, species numbers tested, and findings. Far more surveillance has been initiated among bat populations than other wildlife and domestic animals, with nearly 26,000 bat individuals tested. Though coronaviruses have been identified from approximately 7% of the total bats tested, surveillance among other animals identified coronaviruses in less than 1%. In addition to a large undescribed diversity, sequences related to four of the seven human coronaviruses have been reported from African bats. The review highlights research gaps and the disparity in surveillance efforts between different animal groups (particularly potential spillover hosts) and concludes with proposed strategies for improved future biosurveillance.

1. Introduction

In the past two decades, four novel coronaviruses of public and veterinary health importance have emerged. These include the three agents originating from China; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 [1,2], swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) among localized pig farms in 2017 with re-emergence in 2019 [3,4], and SARS-CoV 2 towards the end of 2019 [1,4,5,6]. The fourth emergent coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), emerged in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012 [7,8]. These events show that coronaviruses have the potential to spillover from natural hosts into different species and cause severe diseases with devastating consequences. Dromedary camels are considered the reservoirs of MERS-CoV, though the original source and transmission routes from animals are still uncertain for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV 2 [9,10,11,12,13], with related viruses identified in bats. Different amplification hosts are considered to be involved in all three human coronavirus (HCoV) outbreaks.

The link between bats and emerging coronaviruses was first considered in 2005 following the identification of coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV in specific Asian rhinolophid bat species [14,15,16]. Since then, a high diversity of coronavirus nucleic acids has been detected in bats, several of which are related to coronaviruses infecting human and domestic animals, with hundreds of unclassified sequences pending characterization. The expanding knowledge of coronavirus diversity has additionally allowed for novel insights into their evolutionary history, including linking bats as the ancestors of specific mammalian coronavirus lineages [17,18]. More specifically, bat coronaviruses with genetic similarity to known coronavirus species, such as HCoV229E and HCoVNL63, are suggested to have acted as ancestors of these human viruses from previous spillover events [19].

Biosurveillance of wildlife hosts, including bats, are one of the first steps towards understanding how viruses emerge [20,21] and include identifying viral diversity, host species, and distribution ranges. However, several factors have been implicated in spillover events, including genetic, ecologic, epidemiological, and anthropological elements [22]. Unless the underlying factors are also identified and mitigated, coronaviruses are likely to continue to emerge in the future.

The high biodiversity on the African continent supports viral species richness, which has been correlated with disease hotspot mapping and novel viral diseases that have emerged or re-emerged in Africa to date [22]. Many communities in Africa live in close contact with wildlife, domesticated animals, and livestock. Some surveillance for bat coronaviruses has been performed in Africa. A recent review by Markotter et al. [23] provides a comprehensive summary of potentially zoonotic coronaviruses reported from Africa (relatives of HCoV229E, HCoVNL63, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV), focusing on the distribution of the host bat species, and concluding that inferences on zoonotic potential based on the genetic relatedness is limiting. This review focuses in greater detail on the total coronavirus diversity identified among African animal species. We review published literature concerning bat species targeted, sample sizes, viral genetic diversity, and evolutionary links to specific host species. The review was also expanded to include the currently available surveillance data among non-bat wildlife and domesticated livestock as hosts of coronavirus diversity. We highlight surveillance approaches from previous studies, important findings, and gaps in current surveillance and propose a surveillance framework to guide the design of future biosurveillance studies.

2. The Importance of Viral Taxonomy

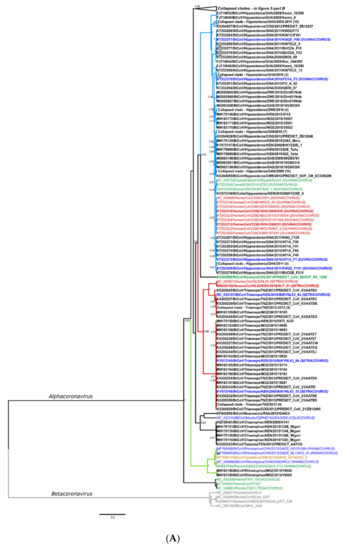

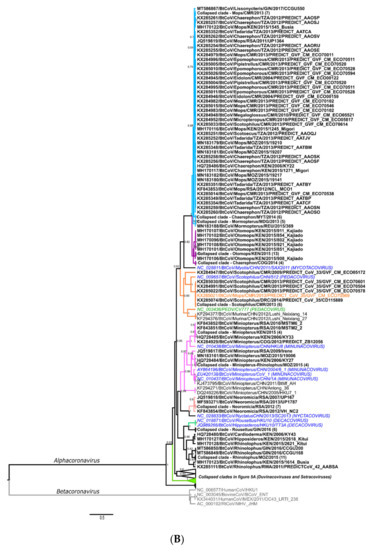

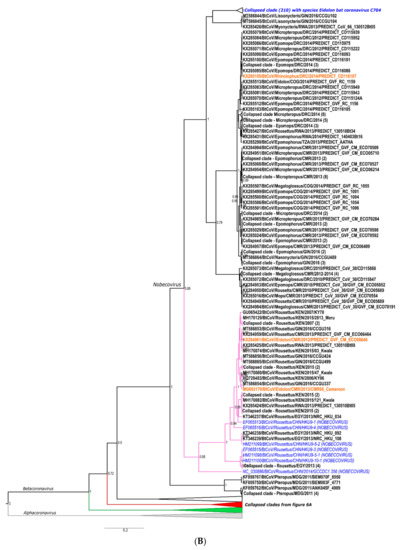

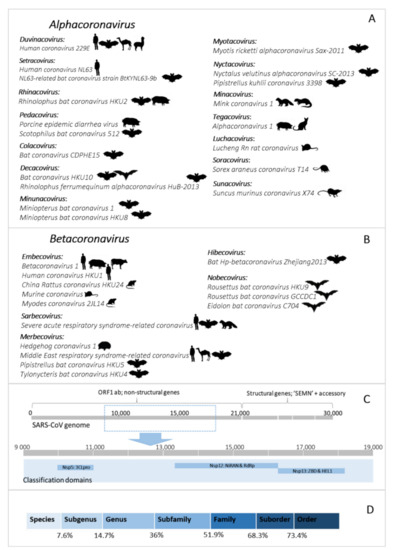

The hierarchical levels of the coronavirus taxonomy are well described [24]. There are currently four genera in the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily: the Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus, and Deltacoronavirus. The Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus genera predominantly infect mammals and are further divided into subgenera (Figure 1A,B). Human coronaviruses group within either the Duvinacovirus, Setracovirus, Sarbecovirus, Merbecovirus, or Embecovirus subgenera (Figure 1A,B). Coronavirus genomes consist of several non-structural genes in open reading frame (ORF) 1 (encoding the replicase polyprotein pp1ab), followed by four structural genes and several accessory genes depending on the species (Figure 1C). Current classification criteria for coronaviruses (ICTV code 2019.021S) rely on comparative amino acid sequence analysis of five domains within the replicase polyprotein pp1ab: 3CLpro, NiRAN, RdRp, ZBD, and HEL1 [6,25]. Computational approaches are used to estimate genetic divergence, and thresholds are utilized as demarcation criteria at various taxonomic levels (Figure 1C,D) [24]. Moreover, only complete genomes are considered for formal taxonomic placement.

Figure 1.

(A,B) Current coronavirus subgenera (bold) and species of the Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus genera. The images indicate host species associated with the virus species. Figure constructed with the species listed on the 2019 Release of the ICTV Virus Taxonomy 9th Report MSL#35: (Available at https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_9th_report/positive-sense-rna-viruses-2011/w/posrna_viruses/222/coronaviridae accessed on 12 December 2020). (C) Representation of the coronavirus genome (based on the reference genome NC_004718.3 SARS coronavirus Tor2) depicting the locations of important domains for classification of species (NSP5 (3CLpro), NSP12 (NiRAN and RdRp), and NSP13 (ZBD and HEL1)). (D) Thresholds of the taxonomic demarcation criteria [24]. Novel viruses are part of a taxonomic level if the divergence within the five concatenated replicase domains is less than the indicated amino acid percentage.

Since the initial identification of bat coronaviruses in 2005, a total of 16 formally recognized coronavirus species have been described from bats. Biosurveillance research mainly report on partial sequences of the coronavirus genome and can only be described to a limited extent by their phylogenetic grouping or similarity percentages. Sequences are considered ‘related’ to genetically similar sequences in a phylogenetic cluster, pending the viral diversity included in the inference. This ‘related’ terminology has become widely misrepresented. It is frequently used to indicate the relatedness of sequences to the closest human coronavirus (HCoV) in a phylogeny, even if these sequences may be significantly distant. For example, SARS-CoV belongs to the Sarbecovirus subgenus; and the Hibecovirus subgenus forms a sister-clade to the sarbecoviruses (Figure S2). Sequences with low similarity to sarbecoviruses, and which should be part of the hibecoviruses, have (even recently) been deemed as ‘SARS-related’. Erroneous conclusions may be readily avoided by including all representative diversity of the current taxonomy in phylogenies. In this review, we will employ the convention of limiting the use of ‘related’ only to describe bat coronaviruses deemed sufficiently similar to known species according to demarcation criteria (e.g., MERS-related, SARS-related, 229E-related, and NL63-related). All others will be described in relation to phylogenetic clusters, using sequence similarities where possible, or indicating possible grouping within a subgenus (Figure 1A).

3. Biosurveillance Studies Based on Nucleic Acid Detection in Africa

Table 1 stipulates the selection criteria utilized to identify and classify publications included in the review. Several surveillance studies focused on bat species were identified [19,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], though few studies were found in regards to surveillance among other wild animals or livestock [40,48,49,50,51] (Table 1). This may be due to the ‘reactive’ nature of surveillance among livestock, domestic animals, and non-bat wildlife in response to outbreak events among farmed animals or human populations; such events have not been regularly reported in Africa. Global examples include studies involving farmed civets following the first SARS-CoV outbreak, surveillance in camel herds after identifying MERS-CoV and detecting SARS-CoV 2 among mink farms in Europe [9,52,53]. Coincidentally, the use of passive unbiased metagenomic next-generation sequencing among illegally smuggled pangolins identified sarbecoviruses with overall genome similarity of 85.5% to 92.4% to SARS-CoV 2 in Asia [10,54,55].

Table 1.

Selection and classification criteria of studies included in the review.

3.1. Surveillance in African Bats

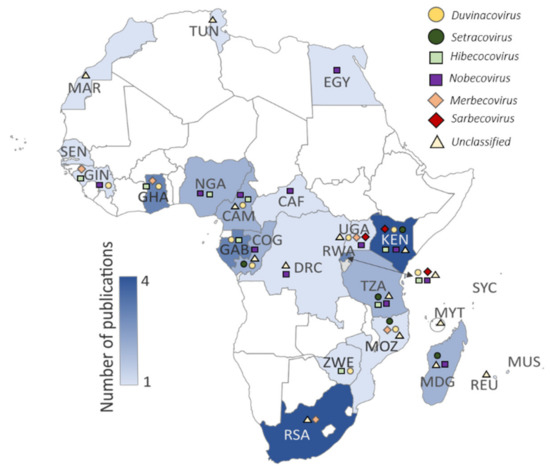

Several surveillance studies focused on bats have been performed in Africa since the first reports in 2009 [26,37]. We identified 23 primary surveillance reports and four subsequent secondary characterization reports [57,58,59,60] (Table 2 and Figure 2) that included sampling in 24/54 African countries (www.un.org, accessed on 6 September 2020). Several reports originate from Kenya, Ghana, Gabon, and South Africa (Table 2, Figure 2), with limited surveillance in Morocco and Tunisia [33]. Most studies focused on one or more sites within a single country (Table S1), though few studies include once-off sampling from multiple African countries [30,33,38,45]. Anthony et al. [30] describe the PREDICT surveillance performed over a 5-year timespan in more than 20 countries, seven of which took place in Africa (with Rwanda surveillance further detailed in Nziza et al. [36]). Furthermore, nine reports identified coronaviruses while conducting broader virological surveillance [29,31,32,34,35,36,39,45], whereas others were coronavirus specific. Supplementary Tables S1–S4 summarize the different reports in terms of approach, species and sample numbers, nucleic-acid detection strategy, and overall findings, including when the information was omitted or not sufficiently described.

Table 2.

Bat coronavirus surveillance performed in Africa, per country.

Figure 2.

Published bat coronavirus surveillance studies per country (shading denoting the number of publications). Symbols in the key above the map represent different coronaviruses detected in the respective countries: Duvinacovirus as a yellow circle (HCoV229E-related viruses), Setracoronavirus as a dark green circle (HCoVNL63-related viruses), Sarbecoviruses as a red diamond (HCoV-SARS-related viruses), Merbecoviruses as an orange diamond (HCoV-MERS-related viruses), Nobecoviruses as a purple square, Hibecoviruses as a green square, and unclassified viruses as a black triangle. Further details on coronaviruses identified can be reviewed in Table S4. Three-letter ISO country code abbreviations are shown on the map.

3.1.1. Sampling Approaches and Methodologies of Bat Coronavirus Surveillance

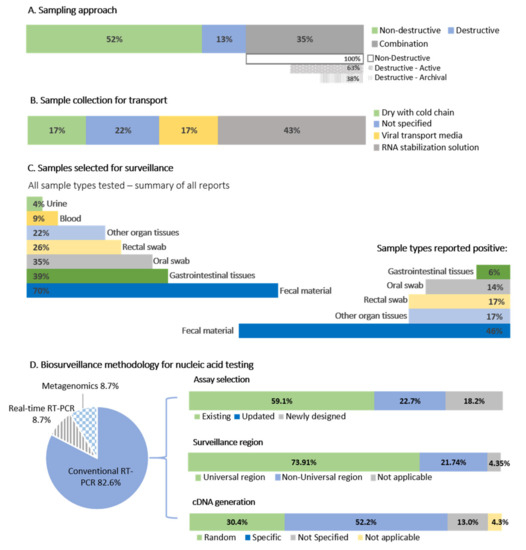

Overall, the primary aim of most of the reports was to detect the presence of coronavirus RNA in bat species, with limited subsequent genetic characterization. Bat species and sample numbers were opportunistically sampled at roosts in mainly cross-sectional once-off sampling focused on a targeted population, region, or species. The frequency of sampling was generally poorly described (Table S1). Exceptions include reports from Madagascar, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, where multiple sampling events (2 or more) were performed at the same roosts [28,31,47]. Figure 3 provides a graphical summary of the approaches employed by surveillance efforts for bat coronaviruses (Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 3.

A summary of coronavirus sampling approaches and methodology. (A) The sampling approaches of the 23 primary surveillance reports. Combination studies are split into those employing new or archival destructive sampling. (B) Sample preservation methods. (C) Sample types selected for surveillance and samples testing positive. (D) Biosurveillance methodology for nucleic acid testing, percentage of studies using conventional, real-time, or metagenomic approaches. The conventional assays were further split into existing assays from the literature, updated exiting assays, or whether new assays were developed. The percentages of studies targeting the ‘universal surveillance region’ (see text for an explanation) contrast to those using different genome regions, and whether specific or random primers were chosen for cDNA preparation.

It is well established that coronaviruses display a gastrointestinal tropism in bats [61], and fecal material or other gastrointestinal sample types such as rectal swabs (non-destructive) or intestinal tissue (destructive) is the preferred sample types for surveillance (Figure 3). Sample collection was mostly non-destructive (52% of studies), including fecal material collected beneath roosting bats in caves and trees [28,29,31,33,37] or fecal material and rectal swabs from individual bats [19,26,27,30,32,34,35,37,42,43,44,46,47]. For this review, we are assuming fecal swabs are the same as rectal swabs. Only 13% of studies solely implemented destructive sampling (collection of organ tissues), and 35% of studies (Figure 3) combined both methodologies to collect sample material for multi-pathogen surveillance [27,30,35,41,43,45] or were tested due to availability within archival tissue banks [32,39,42]. Along with gastrointestinal samples, oral (or throat) swabs were also collected [19,26,27,30,47], but infrequently contained coronavirus RNA [19,27,30,36,39]. Due to limited reporting information provided per study, coronavirus detection among oral swabs can only be roughly estimated. Of all reports investigated, only 35% tested oral swabs (Figure 3). From these reports, 62.5% identified coronavirus RNA, representing positive oral swabs from only 14% of studies overall (Table S1). Coronaviruses were also opportunistically detected within lung and liver tissues [27,38,45], though it is unclear what other positive individuals’ organs were also tested.

The basic methodology implemented in all but two studies [32,34] involved RNA extraction of samples followed by nucleic acid detection targeting a conserved region of the genome. A region of the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene within the open reading frame (ORF) 1b of the coronavirus genome (Figure 4) is mostly targeted and corresponds to approximate nucleotide position 15,200–15,600 in the coronavirus genome (using reference NC_004718.3 SARS coronavirus Tor2) (Figure 4, Table S2). Targeting of this “universal coronavirus surveillance region” enables comparison between studies, though 74% of the African bat surveillance studies utilized assays based on the region (22% either used a non-universal region or combination of both; Table S2). The addition of a nested step is generally essential for the detection of low concentration viral RNA. A small number of studies in Africa quantified viral concentrations of positive samples, obtaining as little as 50–450 RNA copies/mg fecal material for some low concentration samples, or between 323 to 1.5 × 108 RNA copies/g of fecal material [37,44].

Figure 4.

Representation of the coronavirus genome (based on the reference genome NC_004718.3 SARS coronavirus Tor2) depicting the assay regions. The assays corresponding to this universal region included in Tong et al. [26], de Souza Luna [62], Geldenhuys et al. [42] and Geldenhuys et al. [32] (based on primers from Woo et al. [63]), Razanajatovo et al. [47] (based on Poon et al. [14]), Shehata et al. [27], Waruhiu et al. [29] (based on Watanabe et al. [64]), Chu et al. [65], Gouilh et al., [33]. The RdRp grouping units (RGU) amplification region by Drexler et al. [66] is indicated with the line and arrows.

The majority of surveillance studies (52.2%) implemented a one-step kit approach (i.e., utilizes RNA templates in a single reaction with target-specific primers for cDNA followed directly by PCR amplification), with seven (30.4%) implementing an unbiased methodology for the preparation of cDNA with random hexamers before PCR amplification [31,32,33,35]. An unbiased approach is more beneficial where only limited sample material is available and multi-pathogen surveillance is done. Suitable assays were either selected from the literature (with the assay from de Souza Luna et al. [62] most frequently employed), constitute newly developed assays (included if no reference was provided for assay modifications), or were updated/modified from the literature (Table S2 and Figure 3). Assays selected from the literature were constructed using the available sequence information known at that point in time. The expanding genetic diversity of coronaviruses is high, and even though these assays target a conserved region, existing primers may be less sensitive toward the detection of more diverse viruses. For example, primers developed before the 2012 emergence of MERS-CoV might not be sufficiently sensitive to detect diverse coronaviruses from the Merbecovirus subgenus. Developing new assays or updating available primers have the added advantage of ensuring that some of the expanding sequence diversity of emerging human coronaviruses and newly detected animal coronaviruses can be incorporated; reducing the probability of highly diverse clades going undetected.

Exceptions to this ‘universal CoV surveillance’ region are represented mainly by the nested RT-PCR assay developed by Quan et al. [41], targeting a region downstream of the universal CoV surveillance region, corresponding to the approximate nucleotide position 18,300–18,700 (Figure 4). Sequences amplified with the assay from Quan et al. [41] cannot be directly incorporated in phylogenies using the short universal CoV surveillance region and may only be compared to viruses for which this corresponding genome region is available or with full genomes. The PREDICT surveillance described in Anthony et al. [30] and Nziza et al. [36] utilized two surveillance assays to test samples; that of Watanabe et al. [64] based on the universal region and Quan et al. [41]. In total, the Watanabe assay detected 950 coronavirus sequences compared to the 654 sequences from the Quan assay, with only a 27% overlap [30].

Overall, it is not possible to directly compare methodologies to conclude best practices for coronavirus surveillance. However, non-destructive sampling methodologies (swab collection or fecal material from underneath roosting bats) associated with a gastrointestinal origin allow for successful coronavirus identification with minimal injury to the hosts or ecosystem. Proper preservation of sample material is good practice (cold chain or using preservation media), and unbiased cDNA preparation approaches allow for the conservation of reagents and sample material. The use of appropriate assays and overlapping target regions are essential to enable comparisons between studies.

3.1.2. Summary of Sample Sizes and Bat Species Tested

The surveillance data from the 23 publications were compared to the 2019 African Chiropteran Report (comprehensive report of the current taxonomy with data based on museum records from bats collected across the continent) to determine an estimate of total bats sampled per species (Table S4; [67]). There are 13 extant bat families in Africa, with an estimated 324 species [67]. Eleven families have been included in coronavirus surveillance reports (Table 3). Several publications provided the total bats sampled within a study though may not have specified per species or country, and thus 1966 sampled bats could not be included [29,41]. The sample numbers (per species per country) were not specifically indicated in Anthony et al. [30], but total PREDICT surveillance data for the seven African-surveyed countries was accessed online from Healthmap.org and included in the analyses. We acknowledge that the data likely exceeds the sample size for the countries used for the analysis in the 2017 publication; however, we felt that including the data in our assessment greatly contributes to the total bats sampled in Africa per species—by over 10,000 individuals. Moreover, this data was also used in Table 2 and Tables S1–S3. Of the approximate 127 total bat species included in studies, bat coronaviruses were identified in 59. Nearly 26,000 bat individuals are estimated to have been tested for coronaviruses in African surveillance studies using one or more assays. However, this number comprises mainly pteropid and hipposiderid bats (41.8% and 33%, respectively) and varies per family. The table below highlights the need for additional surveillance in several families, such as the Vespertilionidae. These are abundant bats, and increasing the sample size tested of species in this family may provide a greater understanding of the host ecology of coronavirus species such as MERS-related viruses.

Table 3.

Coronavirus detections according bat host taxonomy.

Coronavirus RNA has been detected in nine of the eleven families sampled, excluding the Emballonuridae and Rhinopomatidae. The Rhinopomatidae represents only one tested individual; approximately 678 bats from four species in the Emballonuridae family have been investigated (Coleura afra, Taphozous perforates, Taphozous mauritianus, and Taphozous hildegardeae). This includes surveillance from eight countries with sample sizes varying from 1 to 172 (Tables S4 and S5). Comparatively, coronaviruses have been identified from families like the Megadermatidae, Rhinonycteridae, or Nycteridae, from which far fewer individuals were analyzed (25–299). The lack of viral detection from the Emballonuridae family could be due to insufficient sample sizes, extremely low prevalence, time of sampling, highly diverse viruses missed by consensus primers, or the absence of coronaviruses. The remaining unsampled Myzopodidae and Cistugonidae families are small (two species each), with limited distributions in Madagascar and Southern Africa, respectively.

Primary surveillance reports investigating one or two species/genera typically focus on abundant hosts that may form large populations with frequent opportunities for contact with human communities [28,31,32,34]. Studies sampling many diverse genera/species (83% of primary surveillance reports) mostly sample species opportunistically present at one or more surveillance sites (Table S3). To estimate sample sizes per species, we looked at the total and average number of individuals per species tested in these reports and specifically noted sample sizes of less than ten individuals (Table S3). For some species, below ten individuals were tested, whereas several hundred [19,27,30,36,45,47] or even thousands of individuals from other species were sampled [44,46]. It was more common for less than 100 individuals to be sampled per species, though a few reports averaged 100–150 per species [19,27,30,36,45,47]. The percentage of species within a report for which less than ten individuals were sampled ranged between 18.5 to 100% of species (Table S3). This constituted more than 50% of species sampled from 11 of the reports and likely represented opportunistically caught individuals. This could not be determined for a further four reports, as sufficient detail was not specified, or samples collected represent colony or population-level sample collection.

A guideline for optimal sample sizes per species was proposed by the meta-analysis of coronavirus surveillance in 20 countries by Anthony et al. [30], with the optimal sampling number being approximately 397 individuals. This was calculated to detect the average number of unique coronavirus groups relating to probable viral species (2.67) estimated to be present in each bat species. Their findings identified that sampling less than 154 individuals per species constituted poor returns on investment and sampling effort [30]. The percentage of species per report from which coronavirus nucleic acids were detected varied between 8.3% to 66.7% (excluding when only one species was sampled). Overall, the percentage positivity of coronaviruses per total samples ranged from below 1% to 25.7% (excluding pools) (Table S3). As expected, increasing either sample sizes or number of species tested show correlation with increased positivity percentages (Pearson’s product correlation t = 8.9289, df = 21, p < 0.001 and t = 5.4952, df = 20, p < 0.001, respectively). The differences in positivity can be attributed to many factors, including the nucleic acid detection assay, the methodology for sample collection (preservation of nucleic acids), time of sampling coinciding with coronavirus excretion, species sampled, and sufficient sample numbers per species. Tables S4 and S5 highlight species commonly detected to host coronaviruses; a detailed description of ‘high-risk’ viruses identified from host species is described below.

3.1.3. Importance of Accurate Bat Species Identification

Correct identification of bat species is essential to conclude potential virus-host associations and estimation of host-viral distribution ranges. This is especially important for complex bat species with similar morphological markers, such as members of the Hipposideridae, Rhinolopidae, and Vespertilionidae. Since the start of coronavirus nucleic acid surveillance among bat species in Africa in 2009, several bat species have undergone species reassignments and name changes. We could not update all new species names for this review and used the taxonomy described in the 2019 African Chiropteran report [67]. However, recent changes of note are among the Hipposideridae, Rhinolophidae, Miniopteridae, and Vespertilionidae families, with additions of new genera (Afronycteris, Pseudoromicia, Vansonia (elevated to genus)) and the reassignment of species to existing and new genera [68,69,70,71]. Some of these include Hipposideros species reassignments to the genus Macronycteris and the resolution of some Neoromicia species with reassignments to Laephotis, Afronycteris, and Pseudoromicia genera [68,69]. Currently recognized species may be accessed at www.batnames.org (accessed 18 November 2020) [72], and new species need to be correctly correlated to geographical distributions.

We investigated the methodologies for host identification implemented by the primary surveillance reports (Table S3). No identification methodologies for bat species were stipulated in seven (30%) of the bat coronavirus surveillance studies; five (22%) report the use of keys to determine morphological identities by either field teams, veterinarians, or experienced chiroptologists; and two (9%) report the use of molecular means of species confirmation. Only nine reports (39%) describe both morphological and molecular methods to identify and confirm host species (Table S3). Molecular methods include either mitochondrial cytochrome B gene or cytochrome C oxidase subunit I sequencing [73,74]. Not only is this good practice in ensuring accurate determination of host species identity, but if deposited on public reference databases, it ensures that the records of these sequences for sampled species are expanded. However, depositing sequences of individuals lacking accurate morphological identification and failure to update taxonomic changes generally leads to confusion and incorrect host reporting. Thus, reference material on these databases must be associated with correctly identified individuals where morphological identification was conducted by highly trained individuals or experienced bat taxonomists.

3.1.4. Characterization of Bat Coronavirus Genomes and Virus Isolation Attempts

Bat coronavirus surveillance in Africa primarily focused on amplifying and sequencing short amplicon sequences and subsequent diversity determination. The majority of African bat coronaviruses are therefore unclassified and are only represented by a short-sequenced region. Further characterization of the detected coronaviruses is essential for improved phylogenetic placement and comparisons of various genes/proteins for phenotypic analyses. Studies aiming to further characterize identified coronaviruses employed diverse methodologies (Table S2). Sequence-specific primers have been successful in extending the sequenced regions of the ORF1ab [28,47] or recovering complete coding regions of structural genes like the nucleoprotein gene [27,37]. Sequencing these regions generally involved primer-walking strategies with conventional Sanger sequencing or even high throughput sequencing platforms to overcome the length limit of conventional sequencing. The informal RdRp gene grouping units (referred to as RGU; Figure 4) developed by Drexler et al. [66] amplifies an 816 nucleotide amplicon of the RdRp gene. The pairwise distances of the translated 816 nucleotide fragments (272 amino acids) have been used to delimit different groups as a surrogate system for taxonomic placement of detected bat coronaviruses that lack complete genomes. Grouping units of alphacoronaviruses differ by 4.8% and betacoronaviruses by 5.1% [61]. These grouping units have been used as an extension assay by 22% of African bat coronavirus studies [32,35,43,44,46]. It is worth noting that these units are an unofficial estimate of possible species groupings and may be subject to revision as new diversity is detected (as evident by previous decreasing betacoronavirus thresholds from 6.3% to 5.1%) [61].

The number of bat coronaviruses that can correctly be assigned to a viral species is limited to those with available complete genomes. From African studies, there are over 1840 partial coronavirus gene sequences available among public domains (such as NCBI’s GenBank), though only 13 complete genomes and 12 near-complete genomes [19,32,34,41,46,57,58,59]. The MERS-related Pipistrellus bat coronavirus from Uganda was recovered with unbiased sequence-independent high throughput sequencing on the MiSeq platform [59] and a near-complete genome of Zaria bat coronavirus from Nigeria using 454 pyrosequencing [41]. Sanger sequencing with classic primer-walking spanning the entire genome with 70 overlapping hemi-nested PCR assays was implemented to recover a MERS-related Neoromicia bat coronavirus from South Africa [58], with a second variant from the same host sequenced using 11 overlapping hemi-nested PCR assays on the MiSeq platform [32]. For more novel viruses, amplification of more conserved coronavirus genome segments with nested consensus degenerate primers are frequently required before being able to sequence more diverse regions with long-range PCRs [19,46,57].

The limited number of complete African bat coronavirus genomes are reflective of the challenges involved. These include the limited scope of certain studies, low viral RNA concentrations, unavailability of sufficient material, lacking related reference genomes for primer design, availability of high throughput sequencing platforms, expertise, and cost [32,37,46]. To overcome some of these constraints, such as limited availability of material, virus culturing can be attempted. However, coronaviruses are notoriously difficult to isolate in vitro, with various methodologies utilized (reviewed in Geldenhuys et al. [75]). Only bat coronaviruses closely related to SARS-CoV have thus far been successfully isolated in Vero cells because the bat viruses could use the same receptors as SARS-CoV [76,77]. This challenge and limited sample material available after nucleic acid extraction and high-biocontainment requirements are likely contributing factors to why none of the 23 primary surveillance publications or secondary characterization reports attempted cultivation of coronaviruses in cell culture (nor described attempts).

It is important to note the formats of naming conventions among bat coronavirus studies, with only some providing sufficient information on the origins of sequences (Table S2). The Coronavirus Study Group of the ICTV recommends adopting a standardized format for nomenclature that has been used for Influenza viruses and avian coronaviruses [6]. Namely, the reference to a host organism from which the viral nucleic acid was derived, the place of detection, a unique strain identifier as well as mention of the time of sampling (e.g., virus/host/location/isolate/date or as an example BtCoV/Neoromicia/RSA/UP5038/2015). This format also allows rapid identification of inter-genus viral sharing in phylogenetic trees and highlights similar clades of viruses occurring in related species independent of geography. More importantly, this naming convention makes no inference of belonging to a particular species, as species assignments may only be performed once the requirements have been met (i.e., sequencing the genome according to species demarcations).

3.1.5. Coronavirus RNA Identified in African Bats

Global coronavirus surveillance in bats has established several generalizations, with which African studies are in agreement. Namely, bat coronaviruses generally display host specificity, which is usually evident at the genus-level [19,61,78,79,80]. As a result, certain viral species or even subgenera may be predominantly associated with specific host genera (e.g., rhinolophid bats and Sarbecovirus). This association has been observed to be independent of the geographical isolation of the bat hosts [38,81,82]. The evolution of coronaviruses has been suggested to involve a combination of two mechanisms, co-evolution between viral and host taxa and frequent cross-species transmission events [78]. Co-evolution is evident by genus-specificity and the large diversity of bat coronaviruses globally sampled, though many taxa host more than one species/group of coronaviruses [37,78]. Meta-analyses of publicly available bat coronavirus sequences confirmed long-term evolution among bats and determined that frequent cross-species transmissions occur, particularly among sympatric species, though often result in transient spillover among distantly related host taxa [19,30,78]. Such transmissions potentially create viral adaptation opportunities to new hosts and increase overall genetic diversity [83]. Uniquely for Africa, the genetic information of bat coronaviruses sharing similarity to human coronaviruses have been identified in four of the five subgenera associated with human coronaviruses—Duvinacovirus, Setracovirus, Merbecovirus, and Sarbecovirus (Figure 1A,B). Such findings suggest opportunities for transmission from bats to other animals or directly to humans may have occurred in the past. Though these viruses are still circulating among these hosts, discerning current risks of spillover is limited by available evidence.

Together with highly variable mutation rates [84,85], coronaviruses are also known for recombination events, where homologous recombination between similar coronaviruses is the most likely. However, recombination between different co-infecting coronaviruses from different subgenera/genera has also been documented [86,87,88]. Opportunities also increase when bats are co-infected by more than one species of coronavirus. Moreover, heterologous recombination between viral families has also led to the assimilation of novel genes in certain coronaviruses [86,87]. Recombination hotspots within the spike gene have been identified for diverse coronaviruses originating from humans, domestic animals, and bats [89]. Some of the new resultant variants may have improved fitness advantages within their native or new hosts, and new recombinants may be more suited to the usage of new receptor molecules.

Phylogenies were constructed with the sequences from the 23 primary surveillance reports and secondary characterization research studies, representing the sequence diversity of African bat coronaviruses compared to formally classified species and relevant reference sequences (see Appendix A and complete phylogenies in Figures S1 and S2). The following sections summarize the information available regarding detected bat coronaviruses associated with known human coronaviruses and highlight the importance of recombination in the emergence of novel viruses. We also discuss the large diversity of unclassified and unstudied viruses in some highly abundant host species and consider possible interaction opportunities between humans and bat hosts.

3.1.6. Investigating Factors Affecting the Maintenance of Bat Coronaviruses

Understanding how bat coronaviruses are maintained in their host populations allows determination of infection duration and times that may be at ‘higher risk’ for coronavirus spillover opportunities. ‘High risk’ periods coincide with increased excretion of viruses from bats in a colony and may be associated with reproductive or seasonal factors affecting the viral infection dynamics of the colony. For example, an increase of mating activity and accompanying hormonal changes may affect the susceptibility of hosts to infection, or the increase in immunologically naive juveniles at the start of a birthing pulse creates a large population of bats susceptible to infection [106,107,108]. Understanding these dynamics allows the formulation of management plans to mitigate risks and facilitate engagement with communities at risk of frequent contact with particular bat populations. Behavioral changes may assist in reducing the associated risks of exposure and possible spillover interactions [109].

Limited African studies (only 5) expanded data analyses to include correlations between bat biology, ecology, and viral status of hosts [30,36,38,40,44]. Those investigating increased infection among age classes agree that subadults are more likely to host coronaviruses than adults [30,36,44], consistent with reports from other continents [109]. A higher frequency of infection was also identified among lactating females [44], though also males [30]. Most disagreements center around seasonality, with either no correlation identified [36] or a higher chance of detecting coronaviruses in the dry seasons [30]. Longitudinal surveillance projects would be able to assist with such interpretations in the future.

Bats occupy a wide range of niches, including diverse roost preference (e.g., cave-dwelling or tree-roosting), eating habits (frugivores, nectivores, insectivores, etc.), population sizes (less than 10 to thousands), and level of social interaction between the same and different species (gregarious or non-gregarious). It may also be possible that factors affecting the maintenance of coronavirus infection among bat species may not be universal to all bat species. Thus, combining coronavirus data from different species may result in biased conclusions. For example, it has been suggested that bat coronaviruses may amplify within maternity colonies [108], though the reproductive seasons of diverse bat species do not all overlap, and certain species are capable of reproducing more than once a year, depending on the geographic regions. For example, Rousettus aegyptiacus displays two birthing pulses among populations along the North of Africa [110], while populations in Southern Africa have only one [111]. Thus, if coronavirus maintenance is linked to its host species’ reproductive biology, viral shedding may be predictable for certain species in particular climate zones.

A recent study predicted high-risk periods for different host species utilizing available surveillance data from three countries (Rwanda, Uganda, and Tanzania) and Bayesian modeling [30,60]. Though several assumptions were made regarding the duration of lactation and weaning, they determined that juveniles recently weaned were 3.34 times more likely to shedding coronavirus RNA than juveniles that were not recently weaned. Even adults were nearly four times more likely to be shedding coronaviruses when juveniles were being weaned [60], possibly due to increased coronavirus excretion levels within the colony. As described in Wacharapluesadee et al., [109], increased coronavirus shedding among juvenile bats may be due to vertical transmission from mother to pup, which coincides with studies describing viral shedding from lactating females with increased frequency compared to non-lactating females [112]. The higher frequencies observed in recently weaned juveniles may be due to the loss of maternally received antibody protection following weaning [60,108]. These conclusions require confirmation with longitudinal surveillance among investigated bat species as well as serological studies determining changing antibody levels between lactating mothers, weaning and non-weaning juveniles, as well as other adults in the colony.

3.2. Surveillance in Other Wildlife and Domestic Animals (Livestock)

Coronavirus nucleic acid surveillance among non-bat wildlife, livestock, or other domestic animals in Africa is very limited, both in the frequency of research, sample sizes of animals tested, locations targeted, and are frequently investigated for only specific coronaviruses. Nucleic acid testing in animal populations where the prevalence of infection may be very low would yield limited data, provided that sampling was performed at a time when animals are infected or actively excreting viruses [113]. We only identified four reports in which other animals were tested for coronavirus nucleic acids, including anthroponoses of HCoVOC43 between humans and chimpanzees in Côte d’Ivoire [48], MERS-CoV specific surveillance among 4248 livestock animals from Ghana (cattle, sheep, donkeys, goats, and pigs) [50], general surveillance among 731 wildlife animals (rodents, non-human primates, and ad hoc samples of other wildlife) in Gabon [40], as well as just over 27,000 animals (birds, domestic animals, carnivores, pangolins, swine, rodents, and non-human primates) as part of the PREDICT surveillance initiative (accessed via Healthmap.org) (Table 4). Though this seems like a significant number of individuals tested, the total species diversity among all 16 countries sampled is much larger than the fraction represented by this surveillance. Moreover, not all hosts listed were surveyed in all countries (Table 4), with mostly opportunistic sampling from accessible individuals. However, even though the total positives detected in relation to the total number sampled is <1%, it still shows the presence of coronaviral RNA from among non-human primates (14 chimpanzees), ungulates (1 bush duiker), carnivores (1 African palm civet) and rodent species (13 individuals) from opportunistic surveillance [48,56].

Table 4.

Summary of animals (non-bat) tested for coronavirus nucleic acids.

Two of these sequences, publicly available and corresponding to the universal surveillance region (excluding the anthroponoses of HCoVOC43 from the chimpanzees), were included in the phylogenies in Figure 5A and Figure 6A (KX285508 and KX285250). Most of the detected African rodent coronavirus partial sequences are phylogenetically placed in the Embecovirus subgenus, with human coronaviruses OC43 and HKU1 and other rodent coronaviruses from Asia [18,30]. Divergent rodent alphacoronavirus virus RNA was also identified (KX285508), as well as highly divergent shrew coronaviruses [30]. The sequence information confirms surveillance data from Asia and Europe, namely that rodents and shrews likely harbour additional undiscovered diversity of coronaviruses. Improved systematic and longitudinal surveillance of wildlife and domestic populations will provide more data on the presence of coronaviruses among these animal groups. The research is too limited to make any conclusions regarding the absence of viral sharing between animal groups. Additionally, serological surveillance would complement nucleic acid surveillance by providing data on hosts not actively infected with coronaviruses.

Not included in Table 4 is the expansive surveillance of dromedary camel populations for MERS-CoV. MERS-CoV is not only endemic to the dromedary camel populations of the Middle East but also populations in Northern Africa (Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali, Morocco, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia) [93,114]. Seroprevalence of adult dromedaries is high (80–100%) and may result in respiratory disease with viral shedding via nasal discharge [93,115]. Despite this widespread occurrence, MERS infections among people from camels have only been reported from the Arabian Peninsula [114,115]. Viruses from African dromedaries form a separate basal lineage to the two clades of MERS-CoV identified from infected people and camels on the Arabian Peninsula [114,116], though still share antigenic similarities through cross-neutralization [114]. Furthermore, within this African clade, genomes from the West and North African dromedary populations (Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Morocco) display deletions in specific accessory genes [114,117,118]. It has been suggested that these accessory genes are not required for the adaptation of the virus to dromedary camels and may have been necessary for a more historical host [114]. Whether bat-borne MERS-related viruses established in dromedary camel populations can only be addressed with better surveillance of African bat and dromedary populations, especially where bat and camelid distributions overlap [32].

7. Conclusions

Surveillance of coronaviruses in wildlife and potential spillover hosts is complicated with logistical, technical, and practical challenges. Proper biosurveillance requires detailed planning ahead of time with well-formulated research questions [150] and essential resources such as highly skilled staff, funding, and operating within ethical and regulatory requirements. Availability of research tools such as appropriate diagnostic assays, standardized protocols, and correct species (specifically related to wildlife) identification is paramount. Studies based on nucleic acid detection have been more commonly used, given the lack of suitable or validated serological assays. The development of such assays is further complicated with issues concerning coronavirus culture in vitro and stringent biosafety Level III conditions. The latter limits research to only a few groups when additional characterization, pathogenicity investigations, and determination of the zoonotic potential of newly discovered bat, rodent, and wildlife coronaviruses is needed. The development of recombinant proteins for serological assays and reverse-genetics systems for coronavirus rescue, though technically complex, are some of the only available options at present.

Much of the coronavirus biosurveillance studies reported, particularly in wildlife, has been reactive to outbreaks/newly emerging viruses and very opportunistic. The current coronavirus research identified many coronavirus host species among bats and rodents and provided novel insights into the possible evolutionary origins of some human coronaviruses [25,35,54]. Moreover, specific groups of coronaviruses have been identified for further research due to lack of characterization and high coronavirus diversity among abundant host populations with opportunities for human contact. The studies mainly provided “snap-shots” of diverse coronaviruses among different species, time points, and geographical locations. Such approaches do not allow long-term monitoring of these viruses in host species toward understanding the factors involved in viral maintenance, nor does it provide cues for interpreting increased risk of spillover. Systematic longitudinal investigations of both natural and potential spillover hosts are needed. Additional layers of investigation must include studying human behavior and anthropological influences and the roles of virus/host interactions, pathogenicity, and the natural ecology of the virus. Investigations of coronavirus diversity among other wildlife (particularly rodents) and livestock are at infancy, with much still unknown. As a result, the future of coronavirus research in African has many topics to cover and will expand continent-wide, requiring an interdisciplinary collaborative approach and significant resource investment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v13050936/s1, Figure S1: complete Bayesian BEAST phylogeny of African alphacoronaviruses, Figure S2: complete Bayesian BEAST phylogeny of African betacoronaviruses, Table S1: overview of bat surveillance nucleic acid detection studies, Table S2: molecular methodologies employed by the bat surveillance nucleic acid detection studies, Table S3: summary of bat host species tested for coronavirus RNA and positive species reported, Table S4: coronavirus surveillance performed per bat host species, Table S5: bat species from which coronaviruses have been reported (positive species).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., M.M., W.M., J.W., J.T.P., J.H.E.; Data collection, M.G. and M.M.; Data curation, M.G. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., M.M., W.M.; Draft review M.M., W.M., J.W., J.T.P., J.H.E.; funding acquisition, W.M., J.W., J.T.P., J.H.E.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported in part by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa: the DSI-NRF South African Research Chair held by WM Grant No. 98339 (postdoctoral fellowship funding). The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. The project or effort depicted was or is sponsored by the Department of the Defense, Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA1-20-1-0025). The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the federal government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. MG and MM were also supported by the University of Pretoria’s postdoctoral funding program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Details of Phylogenetics

Short sequence lengths may hamper the resolution of a phylogeny, resulting in poor support for certain clades. The phylogenies in Figures S1 and S2 (and Figure 5 and Figure 6) were constructed to include as many African bat coronavirus sequences as possible while still allowing for sequence lengths that would yield well-supported clades. Therefore, sequences that would have resulted in alignments of less than 200 nucleotides were omitted with final lengths between 260 and 294 nucleotides, respectively. For simplicity, all sequence names were converted to the standardized convention with the modification of listing unique sequence identifiers last. Sequences were obtained from Genbank (NCBI) by searching the accession numbers listed in the publications identified as described in Table 1, or manually searching for the publication title. The accession numbers of all sequences included are provided in the phylogenetic trees. Sequence alignments and editing were performed with ClustalW in Bioedit [151]. Maximum clade credibility trees were constructed using suggested models selected from jModelTest2.org [152]. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with Bayesian phylogenetics using BEAST v. 1.10 using the general time-reversible model (GTR) plus invariant sites and gamma distribution substitution model [153]. The CIPRES Science Gateway was used to run computationally expensive analyses such as alignments, jmodeltest, and BEAST [154]. The Bayesian MCMC chains of the alphacoronavirus phylogeny was set to 20,000,000 states, sampling every 2000 steps, and the betacoronavirus phylogeny was set at 25,000,000 states (sampling every 2500 steps). Final trees were calculated from the 9000 generated trees after discarding the first 10% as burn-in. Trees were viewed and edited in Figtree v1.4.2.

References

- Ksiazek, T.G.; Erdman, D.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Zaki, S.R.; Peret, T.; Emery, S.; Tong, S.; Urbani, C.; Comer, J.A.; Lim, W.; et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1953–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, M.; Gamieldien, J.; Fielding, B.C. Identification of new respiratory viruses in the new millennium. Viruses 2015, 7, 996–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Fan, H.; Lan, T.; Yang, X.L.; Shi, W.F.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.W.; Xie, Q.M.; Mani, S.; et al. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature 2018, 556, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Q.N.; Su, J.N.; Chen, G.H.; Wu, Z.X.; Luo, Y.; Wu, R.T.; Sun, Y.; Lan, T.; Ma, J.Y. The re-emerging of SADS-CoV infection in pig herds in Southern China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 2180–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Baker, S.C.; Baric, R.S.; de Groot, R.J.; Drosten, C.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Haagmans, B.L.; Lauber, C.; Leontovich, A.M.; Neuman, B.W.; et al. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.M.; Van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO MERS-CoV Situation Update, January 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Licence CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.T.-Y.; Jia, N.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Shum, M.H.-H.; Jiang, J.-F.; Zhu, H.-C.; Tong, Y.-G.; Shi, Y.-X.; Ni, X.-B.; Liao, Y.-S.; et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature 2020, 583, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, M.G.; Elmoslemany, A.; Al-Hizab, F.; Alnaeem, A.; Almathen, F.; Faye, B.; Chu, D.K.W.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Peiris, M. Dromedary camels and the transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 64, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haagmans, B.L.; Al Dhahiry, S.H.S.; Reusken, C.B.E.M.; Raj, V.S.; Galiano, M.; Myers, R.; Godeke, G.; Jonges, M.; Farag, E.; Diab, A.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: An outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, L.L.M.; Chu, D.K.W.; Chan, K.H.; Wong, O.K.; Ellis, T.M.; Leung, Y.H.C.; Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Suen, K.Y.; Yuen, K.Y.; et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in bats. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Ren, W.; Smith, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Eaton, B.T.; Zhang, S.; et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-Like coronaviruses. Science 2005, 310, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Li, K.S.M.; Huang, Y.; Tsoi, H.-W.; Wong, B.H.L.; Wong, S.S.Y.; Leung, S.-Y.; Chan, K.-H.; Yuen, K.-Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14040–14045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Huang, Y.; Yuen, K.-Y. Coronavirus diversity, phylogeny and interspecies jumping. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 234, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Li, K.S.M.; Tsang, A.K.L.; Fan, R.Y.Y.; Luk, H.K.H.; Cai, J.-P.; Chan, K.-H.; Zheng, B.-J.; Wang, M.; et al. Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 with implications on the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3076–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Shi, M.; Chommanard, C.; Queen, K.; Zhang, J.; Markotter, W.; Kuzmin, I.V.; Holmes, E.C.; Tong, S. Surveillance of bat coronaviruses in Kenya identifies relatives of human coronaviruses NL63 and 229E and their recombination history. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01953-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, S.J.; Epstein, J.H.; Murray, K.A.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.M.; Solovyov, A.; Ojeda-Flores, R.; Arrigo, N.C.; Islam, A.; Khan, A.; et al. A strategy to estimate unknown viral diversity in mammals. MBio 2013, 4, e00598-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salkeld, D.J.; Stapp, P.; Tripp, D.W.; Gage, K.L.; Lowell, J.; Webb, C.T.; Brinkerhoff, R.J.; Antolin, M.F. Ecological traits driving the outbreaks and emergence of zoonotic pathogens. Bioscience 2016, 66, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.; Murray, K.A.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Morse, S.S.; Rondinini, C.; Di Marco, M.; Breit, N.; Olival, K.J.; Daszak, P. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markotter, W.; Coertse, J.; De Vries, L.; Geldenhuys, M.; Mortlock, M. Bat-borne viruses in Africa: A critical review. J. Zool. 2020, 311, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Krupovic, M.; Mushegian, A.R.; Kropinski, A.M.; Siddell, S.G.; Varsani, A.; Adams, M.J.; Davison, A.J.; Dutilh, B.E.; Harrach, B.; et al. The new scope of virus taxonomy: Partitioning the virosphere into 15 hierarchical ranks. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebuhr, J.; Baker, S.; Baric, R.S.; De Groot, R.J.; Drosten, C.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Haagmans, B.L.; Neuman, B.W.; Perlman, S.; Poon, L.L.M.; et al. Create Eight New Species in the Subfamily Orthocoronavirinae of the Family Coronaviridae and Four New Species and a New Genus in the Subfamily Serpentovirinae of the Family Tobaniviridae. 2020. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Website. Available online: https://talk.ictvonline.org/files/ictv_official_taxonomy_updates_since_the_8th_report/m/animal-ssrna-viruses/9495 (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Tong, S.; Conrardy, C.; Ruone, S.; Kuzmin, I.V.; Guo, X.; Tao, Y.; Niezgoda, M.; Haynes, L.; Agwanda, B.; Breiman, R.F.; et al. Detection of novel SARS-like and other coronaviruses in bats from Kenya. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehata, M.M.; Chu, D.K.W.W.; Gomaa, M.R.; AbiSaid, M.; Shesheny, R.E.; Kandeil, A.; Bagato, O.; Chan, S.M.S.S.; Barbour, E.K.; Shaib, H.S.; et al. Surveillance for coronaviruses in bats, Lebanon and Egypt, 2013–2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopardi, S.; Oluwayelu, D.; Meseko, C.; Marciano, S.; Tassoni, L.; Bakarey, S.; Monne, I.; Cattoli, G.; De Benedictis, P. The close genetic relationship of lineage D Betacoronavirus from Nigerian and Kenyan straw-colored fruit bats (Eidolon helvum) is consistent with the existence of a single epidemiological unit across sub-Saharan Africa. Virus Genes 2016, 52, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waruhiu, C.; Ommeh, S.; Obanda, V.; Agwanda, B.; Gakuya, F.; Ge, X.; Yang, X.; Wu, L.; Zohaib, A.; Hu, B.; et al. Molecular detection of viruses in Kenyan bats and discovery of novel astroviruses, caliciviruses and rotaviruses. Virol. Sin. 2017, 32, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, S.J.; Johnson, C.K.; Greig, D.J.; Kramer, S.; Che, X.; Wells, H.; Hicks, A.L.; Joly, D.O.; Wolfe, N.D.; Daszak, P.; et al. Global patterns in coronavirus diversity. Virus Evol. 2017, 3, vex012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgarel, M.; Pfukenyi, D.M.; Boué, V.; Talignani, L.; Chiweshe, N.; Diop, F.; Caron, A.; Matope, G.; Missé, D.; Liégeois, F. Circulation of Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus and Paramyxovirus in Hipposideros bat species in Zimbabwe. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 58, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, M.; Mortlock, M.; Weyer, J.; Bezuidt, O.; Seamark, E.; Kearney, T.; Gleasner, C.; Erkkila, T.; Cui, H.; Markotter, W. A metagenomic viral discovery approach identifies potential zoonotic and novel mammalian viruses in Neoromicia bats within South Africa. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ar Gouilh, M.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Diancourt, L.; Vandenbogaert, M.; Serra-Cobo, J.; Lopez Roïg, M.; Brown, P.; Moutou, F.; Caro, V.; Vabret, A.; et al. SARS-CoV related Betacoronavirus and diverse Alphacoronavirus members found in western old-world. Virology 2018, 517, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yinda, C.K.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Conceição-Neto, N.; Beller, L.; Deboutte, W.; Vanhulle, E.; Maes, P.; Van Ranst, M.; Matthijnssens, J. Cameroonian fruit bats harbor divergent viruses, including rotavirus H, bastroviruses, and picobirnaviruses using an alternative genetic code. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markotter, W.; Geldenhuys, M.; Jansen van Vuren, P.; Kemp, A.; Mortlock, M.; Mudakikwa, A.; Nel, L.; Nziza, J.; Paweska, J.; Weyer, J. Paramyxo- and Coronaviruses in Rwandan Bats. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nziza, J.; Goldstein, T.; Cranfield, M.; Webala, P.; Nsengimana, O.; Nyatanyi, T.; Mudakikwa, A.; Tremeau-Bravard, A.; Byarugaba, D.; Tumushime, J.C.; et al. Coronaviruses detected in bats in close contact with humans in Rwanda. Ecohealth 2019, 17, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferle, S.; Oppong, S.; Drexler, J.F.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Ipsen, A.; Seebens, A.; Müller, M.A.; Annan, A.; Vallo, P.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; et al. Distant relatives of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and close relatives of human coronavirus 229E in bats, Ghana. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joffrin, L.; Goodman, S.M.; Wilkinson, D.A.; Ramasindrazana, B.; Lagadec, E.; Gomard, Y.; Le Minter, G.; Dos Santos, A.; Corrie Schoeman, M.; Sookhareea, R.; et al. Bat coronavirus phylogeography in the Western Indian Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, A.; Vidal, N.; Keita, A.K.; Thaurignac, G.; Esteban, A.; De Nys, H.; Diallo, R.; Toure, A.; Goumou, S.; Soumah, A.K.; et al. Wide diversity of Coronaviruses in frugivorous and insectivorous bat species: A pilot study in Guinea, West Africa. Viruses 2020, 12, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganga, G.D.; Pinto, A.; Mombo, I.M.; Madjitobaye, M.; Mbeang Beyeme, A.M.; Boundenga, L.; Ar Gouilh, M.; N’Dilimabaka, N.; Drexler, J.F.; Drosten, C.; et al. Genetic diversity and ecology of coronaviruses hosted by cave-dwelling bats in Gabon. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, P.-L.; Firth, C.; Street, C.; Henriquez, J.A.; Petrosov, A.; Tashmukhamedova, A.; Hutchison, S.K.; Egholm, M.; Osinubi, M.O.V.; Niezgoda, M.; et al. Identification of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in a leaf-nosed bat in Nigeria. MBio 2010, 1, 00208-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, M.; Weyer, J.; Nel, L.H.; Markotter, W. Coronaviruses in South African bats. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 13, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ithete, N.L.; Stoffberg, S.; Corman, V.M.; Cottontail, V.M.; Richards, L.R.; Schoeman, M.C.; Drosten, C.; Drexler, J.F.; Preiser, W. Close relative of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1697–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annan, A.; Baldwin, H.J.; Corman, V.M.; Klose, S.M.; Owusu, M.; Nkrumah, E.E.; Badu, E.K.; Anti, P.; Agbenyega, O.; Meyer, B.; et al. Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012-related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganga, G.D.; Bourgarel, M.; Vallo, P.; Dallo, T.D.; Ngoagouni, C.; Drexler, J.F.; Drosten, C.; Nakouné, E.R.; Leroy, E.M.; Morand, S. Bat distribution size or shape as determinant of viral richness in African bats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corman, V.M.; Baldwin, H.J.; Tateno, A.F.; Zerbinati, R.M.; Annan, A.; Owusu, M.; Nkrumah, E.E.; Maganga, G.D.; Oppong, S.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; et al. Evidence for an ancestral association of human coronavirus 229E with bats. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 11858–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razanajatovo, N.H.; Nomenjanahary, L.A.; Wilkinson, D.A.; Razafimanahaka, J.H.; Goodman, S.M.; Jenkins, R.K.; Jones, J.P.G.; Heraud, J.-M. Detection of new genetic variants of Betacoronaviruses in endemic frugivorous bats of Madagascar. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrono, L.V.; Samuni, L.; Corman, V.M.; Nourifar, L.; Röthemeier, C.; Wittig, R.M.; Drosten, C.; Calvignac-Spencer, S.; Leendertz, F.H. Human coronavirus OC43 outbreak in wild chimpanzees, Côte d’Ivoire, 2016 correspondence. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Duah, P.; Meyer, B.; Sylverken, A.; Owusu, M.; Gottula, L.T.; Yeboah, R.; Lamptey, J.; Frimpong, Y.O.; Burimuah, V.; Folitse, R.; et al. Development of a whole-virus ELISA for serological evaluation of domestic livestock as possible hosts of human coronavirus nl63. Viruses 2019, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Duah, P.; Sylverken, A.; Owusu, M.; Yeboah, R.; Lamptey, J.; Frimpong, Y.O.; Burimuah, V.; Antwi, C.; Folitse, R.; Agbenyega, O.; et al. Potential intermediate hosts for coronavirus transmission: No evidence of Clade 2c coronaviruses in domestic livestock from Ghana. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burimuah, V.; Sylverken, A.; Owusu, M.; El-Duah, P.; Yeboah, R.; Lamptey, J.; Frimpong, Y.O.; Agbenyega, O.; Folitse, R.; Tasiame, W.; et al. Sero-prevalence, cross-species infection and serological determinants of prevalence of Bovine coronavirus in cattle, sheep and goats in Ghana. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 241, 108544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reusken, C.B.E.M.; Haagmans, B.L.; Müller, M.A.; Gutierrez, C.; Godeke, G.-J.; Meyer, B.; Muth, D.; Raj, V.S.; Vries, L.S.-D.; Corman, V.M.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: An outbreak investigation. Lancet 2013, 3099, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, A.S.; Quaade, M.L.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Fonager, J.; Rasmussen, M.; Mundbjerg, K.; Lohse, L.; Strandbygaard, B.; Jørgensen, C.S.; Alfaro-Núñez, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission between mink (Neovison vison) and humans, Denmark. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Jiang, J.Z.; Wan, X.F.; Hua, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, F.; Chen, J.; Zou, J.; et al. Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)? PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Zhai, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.J.; Li, N.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, X.; et al. Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins. Nature 2020, 583, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HealthMap. Predict USAID Data. Available online: https://www.healthmap.org/predict/ (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Tao, Y.; Tang, K.; Shi, M.; Conrardy, C.; Li, K.S.M.; Lau, S.K.P.; Anderson, L.J.; Tong, S. Genomic characterization of seven distinct bat coronaviruses in Kenya. Virus Res. 2012, 167, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corman, V.M.; Ithete, N.L.; Richards, R.; Schoeman, M.C.; Preiser, W.; Drosten, C.; Drexler, J.F.; Raposo, R.A.S.; Abdel-Mohsen, M.; Deng, X.; et al. Rooting the phylogenetic tree of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus by characterization of a conspecific virus from an African bat. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11297–11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, S.J.; Gilardi, K.; Menachery, V.D.; Goldstein, T.; Ssebide, B.; Mbabazi, R.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Liang, E.; Wells, H.; Hicks, A.; et al. Further evidence for bats as the evolutionary source of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. MBio 2017, 8, e00373-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecino-Latorre, D.; Goldstein, T.; Gilardi, K.; Wolking, D.; Van Wormer, E.; Kazwala, R.; Ssebide, B.; Nziza, J.; Sijali, Z.; Cranfield, M.; et al. Reproduction of East-African bats may guide risk mitigation for coronavirus spillover. One Health Outlook 2020, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, J.F.; Corman, V.M.; Drosten, C. Ecology, evolution and classification of bat coronaviruses in the aftermath of SARS. Antivir. Res. 2014, 101, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza Luna, L.K.; Heiser, V.; Regamey, N.; Panning, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Mulangu, S.; Poon, L.; Baumgarte, S.; Haijema, B.J.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Generic detection of coronaviruses and differentiation at the prototype strain level by reverse transcription-PCR and nonfluorescent low-density microarray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Chu, C.; Chan, K.; Tsoi, H.; Huang, Y.; Wong, B.H.L.; Poon, R.W.S.; Cai, J.J.; Luk, W.; et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel Coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Masangkay, J.S.; Nagata, N.; Morikawa, S.; Mizutani, T.; Fukushi, S.; Alviola, P.; Omatsu, T.; Ueda, N.; Iha, K.; et al. Bat coronaviruses and experimental infection of bats, the Philippines. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Leung, C.Y.H.; Gilbert, M.; Joyner, P.H.; Ng, E.M.; Tse, T.M.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Poon, L.L.M. Avian coronavirus in wild aquatic birds. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12815–12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, J.F.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Glende, J.; Corman, V.M.; Muth, D.; Goettsche, M.; Seebens, A.; Niedrig, M.; Pfefferle, S.; Yordanov, S.; et al. Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11336–11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AfricanBast NPC. ACR African Chiroptera Report 2019; AfricanBats NPC: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019; ISBN 1990-6471. [Google Scholar]

- Monadjem, A.; Demos, T.C.; Dalton, D.L.; Webala, P.W.; Musila, S.; Kerbis Peterhans, J.C.; Patterson, B.D. A revision of pipistrelle-like bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in East Africa with the description of new genera and species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 191, 1114–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, N.M.; Goodman, S.M.; Whelan, C.V.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Teeling, E. Towards navigating the Minotaur’s Labyrinth: Cryptic diversity and taxonomic revision within the speciose genus Hipposideros (Hipposideridae). Acta Chiropterol. 2017, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monadjem, A.; Shapiro, J.T.; Richards, L.R.; Karabulut, H.; Crawley, W.; Nielsen, I.B.; Hansen, A.; Bohmann, K.; Mourier, T. Systematics of West African miniopterus with the description of a new species. Acta Chiropterol. 2020, 21, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; MacDonald, A.; Goodman, S.M.; Kearney, T.; Cotterill, F.P.D.; Stoffberg, S.; Monadjem, A.; Schoeman, M.C.; Guyton, J.; Naskrecki, P.; et al. Integrative taxonomy resolves three new cryptic species of small southern African horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 187, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.B.; Cirranello, A.L. Bat Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Database. Available online: https://www.batnames.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham, J.W.; Patton, J.C.; Schlitter, D.A.; Rautenbach, I.L.; Honeycutt, R.L. Molecular phylogenetics, karyotypic diversity, and partition of the genus Myotis (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004, 33, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldenhuys, M.; Coertse, J.; Mortlock, M.; Markotter, W. In vitro isolation of bat viruses using commercial and bat-derived cell lines. In Bats and Viruses: Current Research and Future Trends; Corrales-Aguilar, E., Schwemmle, M., Eds.; Caister Academic Press: Norfolk, UK, 2020; pp. 149–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, X.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.-L.; Hu, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, M.-N.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wu, L.-J.; Ge, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Daszak, P.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel bat coronavirus closely related to the direct progenitor of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 3253–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopardi, S.; Holmes, E.C.; Gastaldelli, M.; Tassoni, L.; Priori, P.; Scaravelli, D.; Zamperin, G.; De Benedictis, P. Interplay between co-divergence and cross-species transmission in the evolutionary history of bat coronaviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 58, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.C.P.; Li, X.; Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y. Global epidemiology of bat coronaviruses. Viruses 2019, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.P.; Li, K.S.M.; Huang, Y.; Shek, C.-T.; Tse, H.; Wang, M.; Choi, G.K.Y.; Xu, H.; Lam, C.S.F.; Guo, R.; et al. Ecoepidemiology and complete genome comparison of different strains of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related Rhinolophus bat coronavirus in China reveal bats as a reservoir for acute, self-limiting infection that allows recombination events. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2808–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.J.; Wang, J.; Peacey, M.; Moore, N.E.; McInnes, K.; Tompkins, D.M. New Alphacoronavirus in Mystacina tuberculata bats, New Zealand. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latinne, A.; Hu, B.; Olival, K.J.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Chmura, A.A.; Field, H.E.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Epstein, J.H.; et al. Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Wang, M.; Lau, S.K.P.; Xu, H.; Poon, R.W.S.; Guo, R.; Wong, B.H.L.; Gao, K.; Tsoi, H.-W.; Huang, Y.; et al. Comparative analysis of twelve genomes of three novel group 2c and group 2d coronaviruses reveals unique group and subgroup features. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salemi, M.; Fitch, W.M.; Ciccozzi, M.; Ruiz-Alvarez, M.J.; Rezza, G.; Lewis, M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus sequence characteristics and evolutionary rate estimate from maximum likelihood analysis. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 1602–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaykrishna, D.; Smith, G.J.D.; Zhang, J.X.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Chen, H.; Guan, Y. Evolutionary insights into the ecology of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4012–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Liu, W.J.; Xu, W.; Jin, T.; Zhao, Y.; Song, J.; Shi, Y.; Ji, W.; Jia, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. A bat-derived putative cross-family recombinant coronavirus with a reovirus gene. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.J. Structure, function and evolution of the hemagglutinin-esterase proteins of corona- and toroviruses. Glycoconj. J. 2006, 23, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zeng, L.P.; Yang, X.L.; Ge, X.Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Xie, J.Z.; Shen, X.R.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, N.; et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.L.; Baric, R.S. Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: Mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3134–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, P.; Vallo, P. Taxonomic revision of the genus Triaenops (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae) with description of a new species from southern arabia and definitions of a new genus and tribe. Folia Zool. 2009, 58, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Monadjem, A.; Shapiro, J. Triaenops afer, African Trident Bat. Iucn Red List Threat. Species 2017, e.T81081036A95642225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]