Abstract

This research investigated the impact of using lecithin and casein on lignocellulosic fiberboards on their characteristics and properties, including fire resistance. The six experimental variants created included: (1) unmodified reference fiberboards, (2) fiberboards coated with casein only, (3) fiberboards that were vacuum-impregnated with rapeseed or (4) soy lecithin, and (5, 6) fiberboards that were both vacuum-impregnated with lecithin and coated with casein. Evaluation of the board’s mass uptake, density profile, modulus of elasticity, compressive strength and fire behavior (single face exposure to mass loss, maximum posterior temperature, and area burned) demonstrated that vacuum-impregnation with lecithin was the primary driving force behind mass uptake (producing minor densification of the surface), while the casein coating produced only very minor changes to mechanical properties and modestly modified the fire performance. Lecithin alone produced an increase in both mass loss and area burned while producing a decrease in maximum posterior temperature (about 20%–25%). Lecithin-impregnated boards that were also casein-coated displayed a synergistic effect; these boards provided intermediate mechanical properties with the highest levels of fire performance (approximately 20%–30% lower than the reference fiberboards) in terms of both mass loss and area burned while also having approximately 20%–30% lower maximum posterior temperature compared to the reference.

1. Introduction

Ecological insulation materials have received greater focus in recent years, with more consumers viewing their purchasing decisions as a way to shape the environment, as well as improve energy efficiency in buildings. Increased awareness of climate change and stricter regulatory constraints on greenhouse gas emissions in the building industry have also contributed to growing interest in ecological insulation materials. The boards produced from renewable plant biomass (lignocellulose) have been identified as viable substitutes for current fossil-based insulating materials (expanded polystyrene (EPS), extruded polystyrene (XPS), polyurethane (PUR)), due to their lower embodied energy, lower carbon footprint, and superior life-cycle performance when compared to conventional insulating materials. From 2010 to 2024, studies have consistently shown that boards made from biopolymers have the same thermal and mechanical properties as those made from traditional wood products. In addition to providing the same properties as wood-based boards, biobased boards also offer net climate benefits through carbon sequestration and a decrease in global warming potential. However, despite these benefits, current market penetration levels are low due to challenges associated with scaling up production, variability in material properties, and regulatory hurdles. Nevertheless, based on the advancements made in biopolymer modification, processing technologies, and sustainable manufacturing techniques, it is likely that as the construction sector shifts toward circular and low-carbon building systems, the use of lignocellulosic materials for insulation purposes will continue to increase [1,2,3,4].

Manufacturing conditions have a strong influence on the thermal characteristics of insulating materials created from low-density lignocellulosic (from plant cellulose) fibers. Key factors influencing this process include the type of manufacturing process used (wet vs. dry), the techniques employed to refine fibres (such as chemical and/or mechanical treatments), the density of the final product, the temperature at which it was produced, and the adhesive used. Boards made with water as a chemical single-bond lubricant can have lower thermal conductivity and better mechanical properties. They can be much more homogeneous in terms of dispersing and grouping the dominant fibers than those made without water as the lubricant. Additionally, boards produced dry tend to have higher thermal conductivity due to the clustering of fibres and a significantly larger variation in mechanical properties when produced at lower densities [5,6]. Fibre refining and chemical treatments further influence board performance by modifying fibre morphology and surface chemistry; optimised alkali or mechanical refining improves inter-fibre bonding and dimensional stability, while over-refining or excessive chemical treatment can weaken fibres and impair both thermal and mechanical properties [7,8,9,10]. Board density remains a key factor: increasing density generally enhances modulus of rupture and elasticity but also raises thermal conductivity, leading to a trade-off between structural strength and insulation efficiency [11,12,13,14]. Processing temperature must be carefully controlled; moderate thermal modification enhances dimensional stability and fungal resistance. However, temperatures exceeding 180–200 °C can cause hemicellulose degradation and loss of mechanical integrity, even though they reduce moisture-related defects [15,16,17]. Ultimately, the type of adhesive has a significant impact on long-term performance. However, conventional adhesives offer reliable bonding, and well-formulated bio-based systems can achieve similar strength and insulation properties, provided that adhesive-fibre interactions and curing conditions are optimised [18,19,20,21]. Overall, the interaction among these parameters emphasises the importance of integrated process optimisation to attain low thermal conductivity, sufficient mechanical durability, and long-term stability in sustainable fibreboard insulation materials.

The thermal and fire performance of wood fibre insulation boards is strongly influenced by their pore structure, especially pore size distribution, the ratio of open to closed porosity, and pore connectivity. Smaller pores—particularly those below 50 nm—decrease gaseous conduction and thus lower thermal conductivity, while larger pores enhance conductive and radiative heat transfer and can promote convective flow during heating [22,23,24]. The ratio of open to closed porosity further affects heat transfer: closed pores inhibit air movement and enhance insulation efficiency, whereas extensive open porosity increases convective exchange and can speed up flame spread until a critical point is reached [23,25]. Microstructural features such as fibre clustering and orientation influence the continuity of solid heat paths, with aligned or densely clustered fibres raising conductivity and affecting burning rate and flame propagation patterns [6,26]. High pore connectivity enhances gas transport through the fibre network, thereby boosting convective heat transfer and influencing the transition between continuous and discrete flame behaviour [27]. Moisture sorption introduces additional complexity, as water within pores increases effective thermal conductivity by enabling vapour transport and can either cause spalling at high saturation or improve fire resistance at moderate levels [28,29]. Overall, optimising pore size distribution and managing the open-to-closed porosity ratio can significantly reduce thermal conductivity while also enhancing flame resistance, highlighting pore structure as a key design factor in developing high-performance bio-based insulation materials [6,24,25].

Casein-based adhesives in wood composites rely on a combination of molecular and microstructural mechanisms, including polar interactions between casein phosphoproteins and cellulose, as well as protein conformational changes (notably, increases in α-helical content) that enhance wetting, hydrophobicity, and interfacial bonding [30,31,32,33]. Chemical modifications, such as phosphorylation and the use of crosslinkers (e.g., PAE), enhance water resistance, mechanical strength, and thermal stability. Adding nanoparticles or sugars (e.g., nano-ZnO, silica, maltodextrin) further boosts durability and resistance to thermal and microbial degradation [34,35,36,37]. Lime addition, by increasing alkalinity and densifying the adhesive matrix, has been shown to promote early strength, better water resistance, and improved interfacial adhesion in wood-based panels and bark insulation boards [38,39,40]. These developments have enabled the application of casein-based systems in modern bio-based building materials, including wood composites, insulation panels, and, more recently, elements for engineered wood products where low toxicity and renewability are essential [41,42,43]. Long-term durability under moisture cycling and outdoor exposure, as well as consistent compliance with structural and regulatory standards, remain key challenges, and further optimisation of formulation (crosslinking density, additives, pH) and standardised testing is required before casein adhesives can fully replace petrochemical systems in demanding building applications [41,43,44].

Current research indicates that studies directly examining soy or rapeseed lecithin as hydrophobising or fire-retardant agents for lignocellulosic materials are limited, with only sparse evidence for soy lecithin in paper and fibre coatings and no recorded applications for rapeseed lecithin [45,46,47]. Lecithin’s amphiphilic phospholipid structure, especially in soy lecithin, has shown potential to influence water repellence and fire behaviour in related biobased systems, such as microbial cellulose and biotextiles, where lecithin emulsions increased char formation and thermal stability [48]. Mechanistic studies suggest that phospholipid headgroups may participate in phosphorylation reactions during pyrolysis, promoting condensed-phase char formation and enhancing flame resistance [49]. Structural analyses further reveal that soy and rapeseed lecithins contain similar phospholipid classes (PC, PE, PI, PA), but differ in their fatty acid saturation profiles, with soy being more polyunsaturated and rapeseed being more monounsaturated, which affects molecular packing, hydrophobic interactions, and surface activity [50]. These structural differences, along with headgroup chemistry, influence lecithin’s capacity to form hydrogen bonds with cellulose and hydrophobic interactions with lignin [51], ultimately impacting adhesion, surface modification efficiency, and thermal response. Research on phospholipid-cellulose interfaces confirms the presence of strong hydrogen bonding and a headgroup-dependent affinity [52], while variations in acyl-chain saturation influence monolayer stability and interaction strength [53,54]. Although rapeseed lecithin may demonstrate slightly different binding behaviour due to its fatty acid profile [55], both lecithins can engage in synergistic or competitive interactions with lignin-cellulose matrices [56,57], affecting composite performance. Overall, while direct applications remain insufficiently explored, the molecular structure and interaction mechanisms of soy and rapeseed lecithin endorse their potential as sustainable hydrophobising and fire-retarding agents in lignocellulosic materials, meriting further targeted research [58,59].

Among existing modification methods, vacuum-pressure impregnation is widely recognised as the most effective technique for improving wood fibre composites with natural biopolymers, as it offers the deepest penetration, highest polymer retention, and superior gains in mechanical performance and durability compared to vacuum alone, dipping, or spraying [60,61]. Vacuum treatment enhances penetration by evacuating air from lumens and pits. At the same time, subsequent pressure significantly accelerates polymer uptake and distribution, especially when low-viscosity biopolymer formulations and high vacuum levels (≈−90 kPa) are used [62]. Pressure-only systems improve retention and hardness but are more sensitive to wood anatomy and polymer molecular weight [63]. Conversely, dipping and spraying primarily provide surface-level modification, which can enhance wetting, early-stage water repellence, and surface adhesion; however, they offer limited penetration and lower long-term durability [64,65]. For better bonding, hybrid techniques that combine impregnation with alkali, silane, or acetylation treatments result in markedly improved compatibility between biopolymers and wood fibres, leading to higher mechanical strength and moisture resistance [66,67,68]. Overall, the effectiveness of each method primarily depends on process parameters such as vacuum intensity, pressure duration, polymer viscosity, and wood species anatomy, which collectively influence penetration pathways, interfacial bonding, and overall property improvement [69].

Current research on natural biopolymers, such as casein and lecithins, and other proteins in lignocellulosic insulation boards still lacks comprehensive, multi-property studies that jointly assess physical, mechanical, and fire performance within a single, coherent framework [70,71,72]. Few studies explore combined impregnation-coating sequences, and these are rarely optimised for simultaneous improvements in moisture resistance, strength, and fire retardancy using natural biopolymers rather than conventional flame retardants [71,73,74,75]. Moreover, the optimal binder loadings and their impact on long-term durability and environmental resistance remain poorly quantified [76,77,78,79], while advanced compatibilisation and interfacial engineering strategies for enhancing biopolymer-fiber adhesion (e.g., for casein- or lecithin-based systems) are underexplored and mostly examined in isolation from multi-property performance objectives [80,81,82].

The research outlined in this paper summarises the existing literature, which suggests that impregnated wood fibres have the potential to enhance their fire performance. In this project, porous fibre boards treated with casein and either soy or rapeseed lecithin were assessed as the main research focus to determine their effectiveness, both individually and in combination, in improving fire resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wood Fibers

The pine Pinus sylvestris L. fibres, commercially used for the production of wet-formed softboards, have been supplied by the Research and Development Centre for Wood-Based Panels Sp. z o.o., Czarna Woda, Poland. The degree of defibration of the fibres, established by the producer according to [83] on a vibratory sieve shaker Analysette 3 Pro (FRITSCH GmbH Milling and Sizing, Idar-Oberstein, Germany), was 63 DS. The relative moisture content of the fibrous mass was about 63%.

2.2. Alternative Fire Retardants

The following substances have been used in research as alternative fire retardants:

- Micellar casein, EAN/GTIN 5903849602549, commercially available in a powder state, delivered by KDF S.C., Tarnów, Poland, containing (per 100 g) 1485 kJ energy value, 1.6 g of fat, including 1.6 g of saturated fats, 5.2 g of carbohydrates, including 5.2 g of sugars, 80 g of proteins, 0 g of salt and 0.333 g of L-glutamine; for research purposes the 10% dry matter water solution of casein, Ford #4 cup release time about 16 s (11 s for water), has been prepared by 10 min mechanical stirring with the use of demineralized water.

- Soy lecithin, EAN/GTIN 5904492841040, commercially available in a powder state, delivered by Agroimpulse Sp. z o.o., Bydgoszcz, Poland, containing (per 100 g) 2230 kJ energy value, 0 g of proteins, 53 g of fats, 13 g of carbohydrates; for research purposes, the 10% dry matter water solution of soy lecithin, Ford #4 cup release time about 13 s, has been prepared by 10 min mechanical stirring with the use of demineralized water.

- Rapeseed lecithin, EAN/GTIN 5904492841033, commercially available in a powder state, delivered by Agroimpulse Sp. z o.o., Bydgoszcz, Poland, containing (per 100 g) 3307 kJ energy value, below 0.01 g of proteins, 85 g of fats, 6 g of carbohydrates; for research purposes, the 10% dry matter water solution of rapeseed lecithin, Ford #4 cup release time about 13 s, has been prepared by 10 min mechanical stirring with the use of demineralized water.

2.3. Softboard Production

Fiberboard panels with a nominal thickness of 20 mm and a target density of 300 kg m−3 were manufactured using a wet-forming method under laboratory conditions. The selected steps for panel preparation are illustrated in Figure 1. The fibres were mixed with room-temperature tap water to achieve a fibre concentration of 1.5%. Such a solution was stirred at 600–700 rpm for 15 min (Figure 1a). Immediately after stirring, the solution was transferred to the mat-forming station (Figure 1b), where it initially drained under gravity through a mesh without the application of additional pressure (Figure 1c). Then, the mat, top and bottom covered by steel mesh, was transferred to a room-temperature (cold) hydraulic press PH-1P125 (ZUP-NYSA, Nysa, Poland) and dewatered by pressing to achieve a moisture content of less than 60%. Subsequently, mat hot pressing was conducted at 160 °C for a total of 20 min in a hot press (AKE, Mariannelund, Sweden), with a maximum applied unit pressure of 1.0 MPa (Figure 1d). The material was dried in a drying chamber (Thermolyne 9000 series, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 105 °C for 48 h. No hydrophobic additives were used in this formulation.

Figure 1.

Selected steps of panel preparation: (a) stirring of fibres-water solution, (b) mixing before mat formation, (c) the formed mat before cold pressing, (d) mats after hot-pressing.

2.4. Softboard Modification

The produced mats have been cut to a size of 250 mm × 90 mm. Four such samples have been retained for further testing as reference panels (hereafter referred to as “REF”). The remaining panels were subjected to the following modifications:

- (1)

- Wide surfaces manual covering by casein-water solution in the amount of 280 g m−2 casein dry content, and 24 h drying in the drying chamber at 70 °C (hereafter called “C”; 4 samples).

- (2)

- Room temperature, 0.015 MPa absolute pressure/vacuum (where 0.0 MPa represents a theoretical perfect vacuum), 5 min impregnation by water-soy lecithin solution and 72 h drying in the drying chamber at 70 °C (hereafter called “S”; 4 samples)

- (3)

- room temperature, 0.015 MPa vacuum (as above), 5 min impregnation by water-rapeseed lecithin solution and 72 h drying in the drying chamber at 70 °C (hereafter called “R”; 4 samples).

- (4)

- Room temperature, 0.015 MPa vacuum (as above), 5 min impregnation by water-soy lecithin solution, 72 h drying in the drying chamber at 70 °C, followed by (1) modification (hereafter called “SC”; 4 samples).

- (5)

- Room temperature, 0.015 MPa vacuum (as above), 5 min impregnation by water-rapeseed lecithin solution, 72 h drying in the drying chamber at 70 °C, followed by (1) modification (hereafter called “RC”; 4 samples).

All the samples mentioned above were subjected to conditioning at 20 °C ± 1 °C and 65% ± 2% relative humidity for 5 days. A summary of the prepared samples and their modifications is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of the prepared samples and their modifications.

2.5. Mechanical Properties

The compression behaviour of the tested panels, measured as compression strength at 10% of relative strain (σm) and modulus of elasticity (E), has been characterized according to [84] using four samples of each panel type, with dimensions of 90 mm × 90 mm. Before the tests, the samples were stored at 23 °C ± 2 °C for 24 h.

2.6. Physical Properties

The density profiles of the tested samples were measured with a sampling step of 0.02 mm and measuring speed of 0.1 mm s−1 using a GreCon DAX 5000 device (Fagus-GreCon Greten GmbH & Co. KG, Alfeld/Hannover, Germany) on three samples of 50 mm × 50 mm. After analysing every plot, representative plots of the density profiles for each panel type have been identified for further evaluation. The profile selected for presentation was the one that (i) had an average density closest to the arithmetic mean density of the three specimens, (ii) exhibited a symmetrical U-shaped distribution with respect to the mid-plane, and (iii) showed surface peak and core density values within the range spanned by the other two measured profiles. No profiles displaying atypical shapes or artefacts were excluded, and all measured specimens for each variant showed the same qualitative through-thickness trends, differing only slightly in peak magnitude. The purpose of presenting representative plots was therefore illustrative rather than statistical, aiming to visualise consistent structural features common to all samples rather than to imply specimen-specific behaviour.

The equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of the tested boards, after 5 days of conditioning at 20 °C ± 1 °C and 65% ± 2% relative humidity, has also been determined. As many as eight samples per board type with dimensions of 90 mm × 90 mm have been used. After conditioning, the weight of the samples was measured using a laboratory balance (PS 1000.X2, RADWAG, Radom, Poland) with a precision of 0.001 g. Then, the samples were dried in a drying chamber (Thermolyne 9000 series, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 105 °C for 48 h. The EMC, %, has been calculated as a mass difference before and after drying, referred to as dry mass.

2.7. Under-Fire Properties

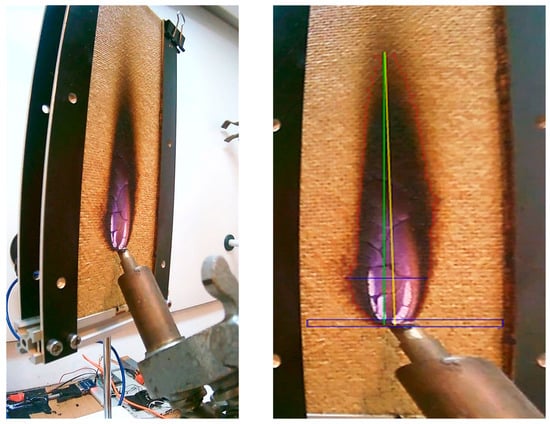

The under-fire properties of the tested panels have been characterized according to the procedure outlined in [85]. The following parameters have been measured during the test: burned area, sample weight loss, and back surface temperature. The flame activity on the sample surface lasted for 10 min. All the mentioned parameters have been measured during the flame activity and 10 min directly after flame retraction. Four samples, each measuring 250 mm × 90 mm, have been tested for every sample type. For further evaluation, representative results are presented after an initial comparison of the result sets for each panel type.

A prototype station [86] was used to test the flammability of the boards, automating and expanding the process to collect additional data. The station consisted of an Axis ad600 laboratory scale (Axis, Gdańsk, Poland) with a sample holder with 100 mm × 100 mm reference holes, a savio cak-01 full HD USB camera (Savio, Rzeszów, Poland), a burner mounted on a guide driven by a stepper motor, and an MLX90641 thermal imaging camera (Waveshare, Hong Kong). The thermal imaging camera was positioned approximately 15 cm from the cold side of the sample, covering its entire width. The size of one pixel of the thermal image corresponded to an area of approximately 20 mm × 20 mm. Temperature data were collected in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (https://www.waveshare.com/wiki/MLX90641-D55_Thermal_Camera, accessed on 1 December 2025), taking into account the calibration values (factory calibration), with the assumed emissivity = 0.95. The whole system, except for the USB camera, was controlled by an Espressif ESP-WROOM-32 ESP32 microcontroller (Shanghai, China), which collected and transmitted data to a computer. The computer was equipped with software designed to simultaneously receive data from the microcontroller and the camera, enabling display, synchronization, and immediate data storage.

The combustion process began with burner preparation (heating and setting the flame length to 20 mm). The burner was then moved towards the sample (to a predetermined position of—< 1 mm from the sample surface, without contact with it). Once the final position was reached, the sample was adjusted to obtain a vertical flame. After 10 min, the burner was automatically moved away from the sample.

The software used for data collection is available at https://github.com/PMKrol/FrAnK/tree/v1.0 (accessed on 1 December 2025) and includes the files FrAnK.cpp and arduino.zip (ESP32 microcomputer software ver. 1.0).

The data analysis process was divided into three stages. All files generated for this study are available at https://doi.org/10.18150/AEFP2D (accessed on 1 December 2025). The software used in the analysis phase is also available on https://github.com/PMKrol/FrAnK/tree/v1.0 (accessed on 1 December 2025). To ensure full reproducibility of the performed analyses, configuration data (including mask values and reference point ROI) are made available in the repository in the output data.zip archive.

The first stage (FrAnCs) involved processing the data collected by the ESP32 microcomputer, extracting the highest temperature from the thermal imaging camera (highest temperature pixel value), the sample mass change, motor position (in steps), and the ESP32 system clock, and storing the data in a CSV file.

The second stage (FrIC) involved preparing and analyzing the burned surface (Figure 2). This process required running the software in setup mode (with the “-s” flag), which allowed for marking the position of reference holes, designating the area of interest, and adjusting color masks. After running the same program without the “-s” flag, the software performed a series of operations, including automatically determining the position of reference holes, removing perspective from the image, filtering the image using masks (marking each image pixel as exceeding appropriate thresholds—light, dark, blue), cumulating masks, and calculating the parameters of the resulting burned surface (area, maximum dimensions—horizontal, vertical, and at any angle). The results were saved to a CSV file. The final step (FrAg) combines the CSV files into a single file, so that the data from the previous analyses (FrAnCs and FrIC) are arranged in order in a single output file.

Figure 2.

Sample input image for burn area analysis (left) and the output from the FrIC program (right). Lines indicate the maximum dimensions of the burn area (green line along the sample and yellow line along the burn area).

The test procedure used differs fundamentally from the ISO 11925-2 [85] method, which uses a flame exposure time of 15 or 30 s and limits the evaluation to observations of ignition and flame height (150 mm). In the presented method, samples (with other test parameters unchanged, such as: size, orientation, flame length, etc.) were exposed to a flame for 10 min, continuously recording mass loss, the area and dimensions of the charred zone, and the temperature of the unexposed side, which allows for a quantitative characterization of the combustion process as a function of time.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data for mechanical tests were subject to variance analysis (ANOVA), and t-tests were used to determine statistical significance (α = 0.05) of differences between factors and levels (IBM SPSS 20 software, Armonk, NY, USA). A comparison of the means was performed when the ANOVA indicated a significant difference, employing the Duncan test. The results on the mechanical properties plot represent the average value and ± standard deviation (SD) bars. The letters “a”, “b” and “c” on the plot indicate the statistically homogeneous groups.

In this study, formal statistical analysis (ANOVA and post hoc tests) was applied only to the mechanical properties, as these measurements were conducted under standardized, quasi-static conditions with relatively low experimental variability, making them suitable for parametric statistical evaluation. In contrast, the fire-test outcomes (mass loss, burned area, and backside temperature) represent time-dependent, non-linear processes that are strongly influenced by transient flame interaction, char development, and coupled heat and mass transfer phenomena. Such responses inherently exhibit greater variability and are less amenable to conventional parametric statistical treatment. Therefore, the fire-test results were evaluated primarily through comparative analysis of trends, consistency of response across replicates, and clear separation between material variants, rather than through formal hypothesis testing.

3. Results and Discussion

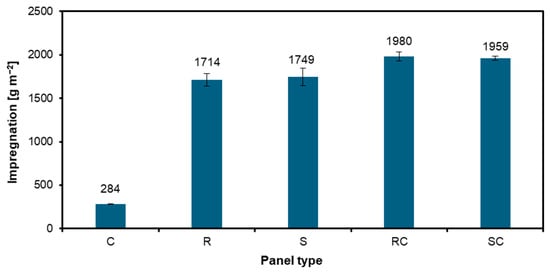

3.1. Impregnation

The amount of impregnating agent retained in the boards, presented in Figure 3, depended heavily on the type of modification applied. Applying a casein-based surface coating alone (C) resulted in only a slight increase in mass, around 300 g m−2 or less, indicating that the casein layer forms a fairly thin film on the board surface without significantly penetrating the internal structure. In contrast, vacuum impregnation with lecithin, whether from rapeseed (R) or soy (S), caused a marked increase in the amount of impregnating agent, reaching approximately 1700–1750 g m−2. This clearly demonstrates that the vacuum process allows for deep and effective penetration of lecithin throughout the board’s cross-section. The highest quantities of impregnating agent, approximately 1950–2000 g m−2, were achieved for the boards that combined vacuum impregnation with lecithin and subsequent casein surface coating (RC and SC). In these cases, most of the added mass comes from the lecithin introduced by vacuum impregnation, while the additional casein layer only results in a moderate further increase. Overall, the results show that the casein coating itself adds relatively little material, whereas vacuum impregnation with lecithin is the main factor influencing the total amount of impregnating substance in the boards; adding the casein coating to lecithin-impregnated boards gives only a limited additional mass gain.

Figure 3.

The amount of impregnation related to the specified technique applied in this research.

These trends are consistent with the literature describing the interaction of casein and lecithin with lignocellulosic matrices. Casein uptake is driven by conformational changes and hydrogen bonding to cellulose, which favours the formation of a thin, near-surface film and explains the low overall mass increase [33,87,88,89]. Lecithin, in turn, acts mainly as a physically penetrating filler; under vacuum, it is forced into lumens and partially into cell walls, with uptake controlled by porosity, anatomy and process parameters, leading to the much higher mass retention observed for R and S boards [90,91,92,93,94]. This deep, volumetric bulking improves compressive response but may slightly reduce stiffness, reflecting the predominantly physical rather than strongly cross-linking nature of the modification [95,96,97,98]. In the RC and SC variants, where most of the mass still originates from lecithin, the thin casein coating despite its small contribution to mass can modify surface chemistry and char formation, providing a plausible basis for the synergistic improvements in fire performance and intermediate mechanical behaviour reported for combined treatments [33,88,92,94,98,99].

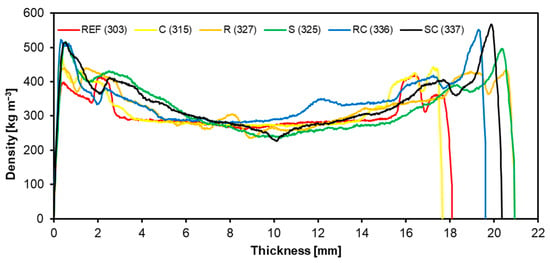

3.2. Density Profile

The density profiles shown in Figure 4 as a function of board thickness reveal that all variants maintain the typical “dish-shaped” distribution characteristic of hot-pressed fibreboards, with clearly higher densities in the near-surface zones and a distinct minimum in the core region. This pattern is symmetrical about the mid-plane of the board. It is consistently observed for the reference panels (REF) as well as all modified boards, indicating that neither surface coating nor vacuum impregnation alters the fundamental through-thickness structure formed during the pressing process. The casein-coated boards (C) display a density profile that closely resembles that of the reference, with only minor changes in the magnitude of the surface peaks, suggesting that the thin casein film contributes little to the overall compaction of the surface layers. In contrast, the boards impregnated with lecithin (R and S) show slightly higher densities in the outer zones compared with REF and C, while the core density remains largely unchanged. This effect is most noticeable in the RC and SC variants, which combine vacuum impregnation with lecithin and subsequent casein surface coating. In these boards, the near-surface density peaks are marginally higher, reflecting the accumulation of the impregnating agent in the outer layers. Despite these differences in absolute values, the overall shape and symmetry of the profiles remain mostly unchanged across all treatments. Overall, the results suggest that impregnation mainly increases the mass and slightly improves the compaction of the surface regions, without fundamentally altering the characteristic density gradient developed across the board thickness.

Figure 4.

The density profiles of the tested materials. Numbers in brackets are average densities.

The persistence of the U-shaped density gradient across all treatments agrees with established findings that this profile is primarily determined during hot pressing through heat transfer, moisture migration and mat compressibility, and is therefore only marginally influenced by post-pressing modifications [100,101,102]. The minimal impact of the casein coating corresponds with studies showing that thin bio- or polymer-based surface layers affect only surface characteristics without altering internal consolidation [91,103,104]. The slightly increased near-surface densities in lecithin-impregnated boards reflect typical capillary-driven uptake behaviour, where added mass accumulates mainly in the outer layers, while the core region remains unchanged [105,106,107,108]. Similarly, the modestly elevated density peaks observed in RC and SC variants are consistent with previous reports in which various impregnation methods enhance surface densification yet maintain the characteristic U-shaped distribution [101,109,110]. Overall, the literature confirms that impregnation influences the magnitude of surface-zone density primarily, while the intrinsic U-shaped gradient established during pressing remains robustly preserved [107,111].

Table 2 reveals that the EMC of all boards remains within a narrow range (9.33%–10.52%), indicating that none of the modifications significantly altered the hygroscopic behaviour of the fiberboards. The REF and C boards exhibit nearly identical mean EMC values and belong to the same statistically homogeneous group, indicating that surface application of casein does not significantly affect moisture equilibrium. Boards impregnated solely with lecithin exhibit a decrease in EMC, with soy lecithin (S) showing the lowest value among all variants. This suggests that lecithin impregnation, particularly with soy lecithin, effectively reduces moisture uptake, likely due to increased hydrophobicity within the board structure. Rapeseed lecithin (R) displays intermediate behaviour, overlapping statistically with both the reference and combined-treatment groups. The combined lecithin—casein treatments (RC and SC) produce EMC values that are clearly lower than REF and C but higher than S, placing them in a distinct statistical group. This pattern suggests that the primary effect on EMC stems from lecithin impregnation, while the additional casein coating slightly mitigates this reduction. Overall, the data suggest that lecithin effectively reduces moisture affinity, whereas casein alone has little impact, and their combination yields a balanced, intermediate moisture response.

Table 2.

The EMC of the tested boards.

From a chemical perspective, casein contains numerous polar functional groups (e.g., amide, carboxyl, and phosphate groups) that can form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which explains why a thin casein surface layer does not reduce EMC and may even slightly maintain moisture affinity similar to the reference boards. Soy and rapeseed lecithins, in contrast, are dominated by amphiphilic phospholipids [112], whose long hydrophobic fatty acid chains reduce the availability of polar sorption sites within the fibre network, thereby limiting moisture uptake. Physically, vacuum impregnation with lecithin partially fills lumens and pores, decreasing accessible pore volume for water vapour sorption and reducing capillary condensation, which contributes to the lower EMC observed. Differences between soy and rapeseed lecithin can be attributed to their fatty-acid composition, as the higher degree of unsaturation in soy lecithin enhances molecular packing and surface coverage, leading to a more pronounced hydrophobising effect and thus a lower EMC.

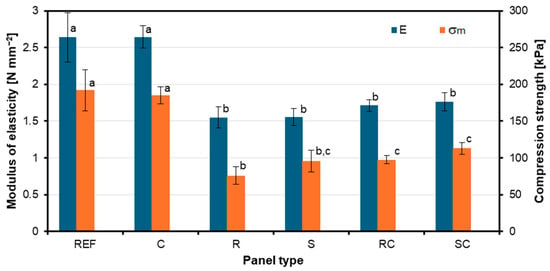

3.3. Modulus of Elasticity and Compression Strength

The mechanical tests (Figure 5) demonstrated a clear impact of the various modification strategies on both the modulus of elasticity and compressive strength. The highest values for both parameters were observed in the reference boards (REF) and boards coated solely with casein (C). The average stiffness of C was only marginally lower than that of REF, by just a few percent, and the ranges for these two variants largely overlapped, indicating that applying a thin casein layer to the surface does not significantly impair the load-bearing capacity of the boards. Boards treated only with vacuum impregnation using lecithin (R and S) displayed a notable decrease in both modulus and strength. For these variants, the mean values dropped by approximately 20%–30% compared to REF, with a considerable separation between their means and those of REF and C. The ranges associated with R and S scarcely overlapped with those of the unmodified or casein-coated boards, highlighting that the softening effect of lecithin penetrating the entire cross-section is substantial and likely systematic rather than incidental. Boards treated with lecithin impregnation followed by a casein coating (RC and SC) showed intermediate results. Their average modulus and compressive strength were clearly higher than those of R and S, recovering a significant portion of the loss caused by lecithin alone. Yet, they remained roughly 10%–15% below the levels measured for REF and C. The ranges for RC and SC partially overlapped both with the lower-performing group (R, S) and the higher-performing group (REF, C), indicating a partial, but not complete, recovery of mechanical properties. Overall, the pattern of average values and their variability suggests that surface coating with casein alone does not degrade the mechanical properties of the boards, vacuum impregnation with lecithin greatly reduces both stiffness and strength, and the combined treatment of lecithin and casein alleviates this adverse effect to a significant, though incomplete, extent.

Figure 5.

The modulus of elasticity and compression strength of the tested materials. The letters “a”, “b”, and “c” represent the statistically homogeneous groups.

The reductions in modulus of elasticity and compressive strength observed in the lecithin-impregnated boards can be attributed to the plasticization mechanisms typical of phospholipid surfactants. Lecithin forms reverse and cylindrical micelles that disrupt the native hydrogen-bond network within lignocellulosic polymers, lowering crystallinity and increasing chain mobility, which leads to pronounced structural softening [113,114]. In contrast, casein coatings act primarily at the surface and enhance fiber-matrix adhesion through protein conformational adjustments and multiscale interfacial interactions, improving mechanical performance without altering the internal structure of the composite [30,115]. In the combined lecithin-casein treatments, the partial recovery of stiffness and strength arises from synergistic interfacial effects, where surfactant-protein complexes form more cohesive boundary layers and gel-like networks that improve load transfer despite the initial plasticization of the core [30,116]. These mechanisms align with the experimental results, showing that lecithin substantially decreases mechanical properties, casein alone does not impair board performance, and the combined modification mitigates—but does not fully reverse—the softening effect.

3.4. Under-Fire Properties

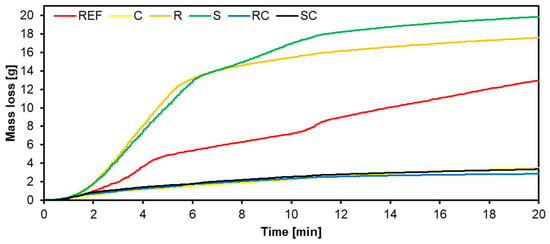

The time-dependent mass loss curves (Figure 6) reveal significant differences in fire behaviour between the board variants. For the reference boards (REF), mass decreased nearly linearly during the 20 min exposure, resulting in a final loss of approximately half of the initial mass. The casein-coated boards (C) followed a very similar pattern, with mass loss at 10 and 20 min only about 5%–10% higher than at REF, and the replicate results for these two variants overlapped across most of the time period. This suggests that applying the casein coating alone does not fundamentally alter the degradation kinetics. The boards impregnated with lecithin only (R and S) showed a noticeably more intense degradation. After just 5 min, their mean mass loss was around 10–15 percentage points higher than REF, representing an increase of roughly 30%–40% relative, and this difference grew as exposure continued. At 20 min, the lecithin-only variants had the highest mass losses among all boards, exceeding the reference by approximately 20%–25%. Their mean values formed a distinct group well above those of REF and C, with R and S showing minimal overlap with the upper part of the REF/C range. This separation, along with limited range overlap, indicates that lecithin impregnation alone causes a significant, systematic, and statistically meaningful increase in mass loss. The best performance was observed in boards that combined lecithin impregnation with a casein surface coating (RC and SC). The curves of these variants increased more slowly throughout the test, and their final mass loss was at least 20–25 percentage points lower than R and S, and approximately 10–15 points lower than REF. This equates to roughly one-third reduction compared to lecithin-only boards, and 20%–30% less than unmodified boards. The ranges for RC and SC were consistently lower than those of all other variants, with minimal overlap, even at the lower values for REF and C, strongly indicating that the reduction in mass loss from the combined treatment is reliable and likely statistically significant.

Figure 6.

The mass loss of the tested panels during the fire test.

These findings suggest that lecithin impregnation alone increases the combustibility of the material, but adding a casein coating to lecithin-treated boards effectively counteracts this, resulting in the lowest and most consistent mass loss among all tested configurations. The casein coating alone leaves the overall fire behaviour similar to that of the reference boards.

The under-fire behaviour observed in the boards is consistent with known thermal degradation mechanisms of phosphorus-containing surfactants and protein-based coatings in lignocellulosic systems. Phospholipid-based modifiers degrade through multi-stage pathways involving phosphorus-rich intermediates, dehydration, and radical-driven reactions, which can lower the onset temperature of degradation and intensify volatile release in lignocellulosic matrices, especially in the absence of mineral co-additives. This helps explain the systematically higher mass loss in lecithin-only boards compared to the reference [117,118]. In contrast, casein is well documented as an intumescent, char-forming fire retardant: it promotes the formation of cohesive, insulating char layers and reduces heat release in wood, MDF and biopolymer composites; so, a thin surface coating can maintain a fire behaviour similar to the reference while providing a modest barrier effect [34,119,120]. When lecithin impregnation is combined with a casein coating, phosphorus-nitrogen synergy and the formation of a more continuous, protein-phosphorus-rich char at the surface lead to improved thermal shielding and reduced mass loss under fire, in line with reports that phosphorylated casein systems significantly enhance char yield and fire resistance in wood-fibre boards and related composites [34,119,121].

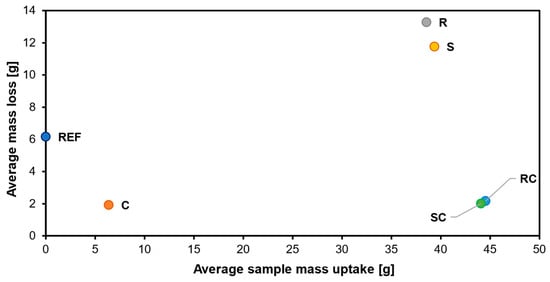

The average mass loss for each sample type after 8 min of combustion was calculated to assess the correlation between impregnation mass and mass loss due to combustion. The results are summarized in Figure 7; the analysis revealed no correlation between these two parameters. It is noteworthy that the mass loss for samples SC and RC is similar to that for sample C, indicating that the combined use of impregnations R and S with C does not provide additional benefits over C alone in the analyzed range.

Figure 7.

The average mass loss during burning referred to the average mass uptake during impregnation.

The higher mass loss observed for boards impregnated with lecithin can be attributed to modified pyrolysis pathways in the lignocellulosic matrix. Lecithin plasticizes the fibre network and enhances molecular mobility, which facilitates earlier generation and release of volatile degradation products, increasing material consumption during combustion. At the same time, the phosphorus-containing headgroups of lecithin and the redistributed lipid phase alter condensed-phase reactions and heat transport, leading to a reduced maximum temperature on the unexposed side. These effects are therefore not contradictory, as increased mass loss and reduced heat transfer originate from different physicochemical mechanisms. In contrast to conventional halogen-free fire retardants, which typically reduce both mass loss and heat transfer through the formation of stable intumescent char, lecithin alone primarily enhances the thermal barrier effect. When combined with a casein surface coating, however, phosphorus–nitrogen synergy and the formation of a coherent protective char layer suppress mass loss while further lowering backside temperature, resulting in a fire response more suitable for building insulation applications.

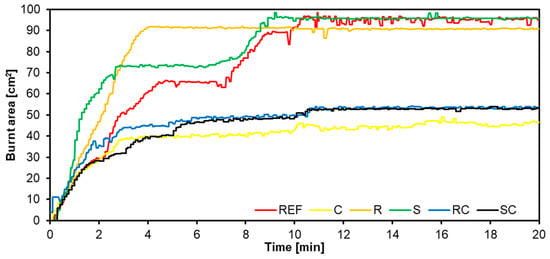

The evolution of the charred area during fire exposure (Figure 8) demonstrated a clear influence of the modification system. For the reference boards (REF), the affected area increased rapidly over time, reaching the highest final values among all variants or being closely matched only by the boards impregnated solely with lecithin (R and S). In these lecithin-treated boards, the growth of the charred region closely followed that of REF throughout the test, and the final areas were similar or slightly higher, differing by no more than a few to around 10%. The average values for REF, R, and S clustered in the upper part of the scale, and the corresponding scatter ranges overlapped considerably, indicating that the isolated use of lecithin does not significantly reduce the extent of surface damage and that any minor differences between these three variants are unlikely to be statistically significant. Conversely, the boards coated only with casein (C) exhibited a modest yet clearly noticeable reduction in charred area compared with REF. The mean values for C remained consistently lower throughout the exposure period, and the final area was reduced by roughly one to two tenths relative to the reference level. The ranges associated with C and REF partially overlapped. Still, the central values shifted downward for C, suggesting a mild yet systematic tendency of the casein coating to limit lateral flame spread and decrease the overall size of the damaged zone. The most significant improvement was observed for the boards combining vacuum impregnation with lecithin and subsequent casein coating (RC and SC). For these variants, the increase in charred area over time was slower than for all other boards, and the final values were substantially reduced—approximately one-third compared with REF and an even larger margin relative to R and S, roughly several tens of per cent. The ranges for RC and SC lay clearly below those for REF, R, and S, with minimal overlap between the upper values of RC/SC and the lower values of the high-burn group, indicating a high likelihood that these differences are statistically significant. At the same time, RC and SC formed a tight cluster with very similar mean values and overlapping ranges, suggesting that the type of lecithin (rapeseed or soy) plays a secondary role once combined with the casein layer. Overall, these results indicate that lecithin impregnation alone maintains the extent of burning at a level comparable to unmodified boards. The casein coating, by itself, offers a moderate reduction in charred area. In contrast, the combined lecithin-casein treatment provides a notably superior fire performance, exhibiting the smallest affected surface among all tested variants, with differences likely to be statistically significant.

Figure 8.

The charred area of the tested panels during the fire test.

The observed differences in the extent of the charred area result from the distinct mechanisms of action of phospholipid- and protein-based coatings, as described in the literature. Phospholipid surfactants reduce the activation energy of pyrolysis and catalyse dehydration, but their action primarily occurs within the bulk of the material rather than at the surface. As a result, they do not form a stable, intumescent barrier capable of limiting lateral flame spread, which explains why boards impregnated with lecithin alone (R, S) exhibit a charred area comparable to the reference boards [122,123,124]. In contrast, casein coatings behave differently: due to phosphorylation and the formation of P–O–C bonds with the lignocellulosic surface, casein promotes the formation of a compact, intumescent char layer that effectively suppresses flame propagation, consistent with the moderate reduction in charred area observed for variant C [34,125,126]. The strongest protective effect in RC and SC results from the well-established phosphorus-nitrogen synergy: interactions between phosphate and amino groups lead to the formation of crosslinked, graphitizing char structures that create a tighter and more thermally stable barrier, significantly inhibiting flame propagation—aligning with reports on the high efficiency of protein-phosphorus-nitrogen hybrid systems [127,128,129]. These mechanisms collectively explain why lecithin alone does not reduce the extent of charring, casein provides moderate protection, and their combination yields the most effective reduction in the damaged surface area.

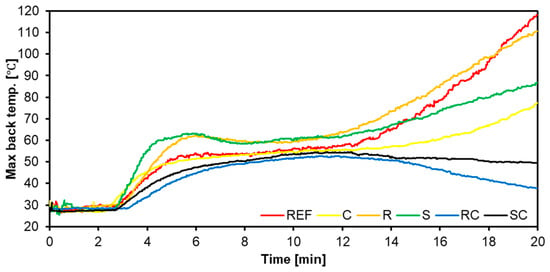

The maximum temperature on the unexposed side of the boards (Figure 9) was greatly influenced by the modification system. For the reference variant (REF), the backside temperature rose steadily during fire exposure and reached the highest value among all boards, establishing an upper benchmark for comparison. The boards coated only with casein (C) exhibited a very similar pattern of temperature increase, but the peak temperature was consistently lower than that of REF, by approximately 5%–10%. The mean values for REF and C were close, and their measurement ranges overlapped considerably, indicating that casein coating alone offers only a modest improvement in thermal insulation. The difference between REF and C may be statistically small, even though the central values tend to favour the coated boards. A much more notable effect was seen in the boards impregnated solely with lecithin (R and S). In these cases, the maximum temperature on the non-exposed surface was clearly lower than that on both REF and C. The peak values for R and S were roughly 20%–25% lower than REF, and their average temperatures formed a distinct group clearly separate from the higher values typical of unmodified and only casein-coated boards. It is worth noting that both R and S panels exhibit a self-extinguishing effect when the temperature drops between 6 and 8 min after the flame activity. The variability in R and S showed limited overlap with the lower end of the REF/C range, suggesting that the improvement in thermal barrier performance from lecithin impregnation is not only significant in size but also likely systematic and statistically meaningful. The best performance was seen in boards that combined vacuum impregnation with lecithin and a subsequent casein coating (RC and SC). These boards exhibited a slower increase in backside temperature. They stabilised at the lowest levels tested, with final maximums reduced by around 30% or more compared to REF, and still notably by about 10%–15% versus lecithin-only boards. The average values for RC and SC were very similar, and their ranges were significantly lower than those of all other variants, with little to no overlap, even with the lower values observed for R and S. This pattern strongly suggests that the combined lecithin-casein treatment provides a reliable and significant enhancement in thermal insulation. Overall, the temperature data show that impregnating boards with lecithin significantly boosts their resistance to heat transfer during fire, and adding a casein surface layer to lecithin-treated boards further strengthens this effect, producing the most effective barrier on the unexposed side.

Figure 9.

The maximum registered temperature of the back side of the sample during the fire test.

Lecithin impregnation significantly lowers the backside temperature because soy and rapeseed lecithin modify the internal structure of the board, increasing heat-storage capacity and reducing thermal conductivity through rheological changes and heat-buffering effects [130,131,132]. Casein coatings primarily act at the surface, where their protein-based, porous layer provides only moderate thermal resistance, consistent with the small temperature reduction observed for variant C [133,134]. The strongest effect in RC and SC results from the documented lecithin-casein synergy: phospholipids stabilise the casein layer under heat, suppress protein aggregation, and create a denser, more coherent thermal barrier, which markedly suppresses heat transfer compared with either treatment alone [135,136].

It should be noted that no dedicated hydrophobic additives were used in the manufacture of the tested fiberboards. This approach was intentionally adopted to isolate the effects of casein and lecithin modifications without the influence of additional chemical treatments. In practical insulation applications, the absence of conventional hydrophobic agents (e.g., waxes or silicones) may result in increased moisture uptake and reduced dimensional stability under conditions of elevated or fluctuating humidity. Although lecithin impregnation led to a measurable reduction in equilibrium moisture content, this effect should be regarded as partial and not equivalent to targeted hydrophobic systems used in commercial insulation products. Therefore, future work should investigate the compatibility of the proposed bio-based modification strategies with mild hydrophobic treatments to ensure long-term moisture resistance and dimensional stability in real-use building environments.

At the molecular level, casein interacts with lignocellulosic fibres mainly through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions between its polar amino acid residues (amide, carboxyl, and phosphate groups) and the hydroxyl groups of cellulose and hemicelluloses, leading to improved interfacial adhesion at the fibre surface. Upon drying or heating, casein undergoes conformational rearrangements that promote protein–protein aggregation and partial crosslinking, forming a cohesive surface film that enhances load transfer and char formation during fire exposure. Soy and rapeseed lecithin, composed primarily of phospholipids, interact with fibres through a combination of hydrogen bonding between phosphate headgroups and cellulose hydroxyls, and hydrophobic interactions between fatty acid chains and lignin-rich domains. These amphiphilic molecules can penetrate the fibre network, partially disrupting the native hydrogen bonding within the cell wall and acting as plasticisers that increase the molecular mobility of the lignocellulosic polymers. During thermal degradation, the phosphorus-containing headgroups of lecithins promote dehydration and condensed-phase reactions, while their interaction with nitrogen-rich casein enables synergistic phosphorus–nitrogen mechanisms that stabilize char and improve fire resistance.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the type and arrangement of modifications with lecithin and casein significantly influence the mass uptake, mechanical behaviour, and fire performance of fibreboards while only marginally changing their internal structure. Vacuum impregnation with lecithin was the primary factor controlling the amount of substance added, resulting in a tenfold increase in uptake compared to the casein coating alone. Despite this, all boards maintained a characteristic dish-shaped density profile with denser surface layers and a less dense core. Only boards containing lecithin, especially those also coated with casein, showed slightly higher densities near the surface. These subtle structural changes contrasted with the clear mechanical effects: applying casein as a surface coating did not notably reduce the modulus of elasticity or compressive strength, whereas lecithin impregnation alone resulted in a significant decrease in both properties, typically around 20%–30% relative to the control boards. The combined lecithin-casein systems partially recovered this loss, producing intermediate mechanical performance. The distinct separation of average values between the control/only-casein group and the lecithin-containing variants, along with limited overlap in the result ranges, suggests that these trends are systematic and likely statistically significant. The results demonstrate that lecithin-based impregnation is the key factor governing EMC, as it consistently reduces moisture affinity by introducing hydrophobic components and limiting the number of accessible sorption sites within the fiberboard structure. In contrast, casein applied alone has a negligible effect on EMC, while its combination with lecithin slightly moderates but does not negate the moisture-reducing effect of lecithin impregnation.

Regarding fire behaviour, the different treatments produced a more intricate but coherent pattern. Lecithin impregnation alone resulted in the highest mass loss and the largest charred areas, indicating increased material consumption during combustion, even as it reduced the maximum temperature on the unexposed side by approximately 20%–25% compared to the control, thereby improving the thermal barrier effect. The casein coating without lecithin had only a modest effect, causing mass loss and charred areas similar to or slightly smaller than those of the control boards, and only marginally lowering the back-side temperature. The combination of lecithin impregnation and casein coating yielded the most favourable fire performance. The RC and SC boards exhibited the lowest mass loss, the smallest charred areas, and the lowest maximum temperatures on the unexposed side, with reductions in key fire parameters of around 20%–30% relative to the control, and even greater reductions compared to the lecithin-only boards. The consistent separation of central values, combined with limited overlap in the ranges of RC/SC versus other variants, indicates that this enhancement is robust and highly likely to be statistically meaningful. Overall, the results reveal a clear trade-off: lecithin impregnation enhances thermal insulation but diminishes mechanical properties, and on its own does not limit the extent of burning; meanwhile, adding a casein layer produces a synergistic effect, stabilising or partially restoring mechanical performance and significantly improving fire resistance.

Future research should aim to quantify these trends more precisely and explore their underlying mechanisms. Microstructural and chemical characterisation of the modified boards, including the distribution and interaction of lecithin and casein within the fibre network, would help to clarify the origins of both the mechanical weakening and the improved fire behaviour. Further investigations should also examine the effects of dosage, application technique, and sequence, as well as the method for both agents, on their long-term stability under varying humidity and temperature conditions. Additionally, performance in more realistic fire scenarios, including larger-scale testing, smoke production, and the emission of potentially hazardous volatiles, should be assessed, ultimately through life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies, to fully quantify the environmental implications of using these bio-based additives. Such studies would provide a more comprehensive basis for optimising hybrid lecithin-casein systems for industrial use in bio-based fibreboards, where a balance between mechanical integrity and enhanced fire performance is essential.

Author Contributions

K.B.K. and A.W. state of the art, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and resources; S.K. investigation, writing—review and editing; P.M.K. conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition; G.K. conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, project administration, and resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available in RepOD at https://doi.org/10.18150/AEFP2D (created and accessed on 2 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The mentioned research was conducted with the support of the Student Furniture Scientific Group (Koło Naukowe Meblarstwa) and CNC Machine Tools Student Research Group (Koło Naukowe Obrabiarek CNC), Faculty of Wood Technology, Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW, Warsaw, Poland. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly for Windows ver. 1.2.214.1792 for superficial text editing (i.e., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schulte, M.; Lewandowski, I.; Pude, R.; Wagner, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Bio-Based Insulation Materials: Environmental and Economic Performances. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladu, L.; Vrins, M. Supportive Regulations and Standards to Encourage a Level Playing Field for the Bio-Based Economy. Int. J. Stand. Res. 2019, 17, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Lee, S.-E.; Choi, G.S.; Buahom, P.; Park, C.B. Trends of Non-CFC Insulation Materials and Thermal Characteristics of CO2-Foamed Plastic Insulation Materials. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, S51041–S51043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Oscanoa, A.J.; Tayo, L.T.; Nayaka, D.S.; Euring, M. Low-Density Wood-Fiber Insulation Boards Produced with Canola Isolated-Protein Based as a Binder. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2578609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderegger, W.; Niemz, P. Thermal and Moisture Flux in Soft Fibreboards. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2012, 70, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrä, H.; Dobrovolskij, D.; Engelhardt, M.; Godehardt, M.; Makas, M.; Mercier, C.; Rief, S.; Schladitz, K.; Staub, S.; Trawka, K.; et al. Image-Based Microstructural Simulation of Thermal Conductivity for Highly Porous Wood Fiber Insulation Boards: 3D Imaging, Microstructure Modeling, and Numerical Simulations for Insight into Structure–Property Relation. Wood Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamath, L.G.; Srimal, L.K.T.; Sewvandi, G.A.; Gallage, R.; Epaarachchi, J. Optimizing the Alkaline Concentration for Coir Fibre Treatment and Estimation of Lifetime. Sri Lanka J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 52, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Z.; Alias, A.H.; Ramli, R.; Wahab, N.A.; Ahmad, M.; Osman, S.; Sheng, E.L. Effects of Refining Parameters on the Properties of Oil Palm Frond (OPF) Fiber for Medium Density Fibreboard (MDF). J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2021, 87, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Deng, J.; Zhang, S.Y. Effect of Thermo-Mechanical Refining on Properties of MDF Made from Black Spruce Bark. Wood Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, E.; Saju, K.K. Impact of Alkali Treatment with Varying Soaking Times on the Physico-Chemical, Tensile, and Morphological Properties of Smilax Zeylanica Plant Fibers. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 16663–16673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lebel, S.; Henry, A.; Deng, J.; Ricard, M. Cellulose Filament Reinforcement of Wood Fibre Insulation Boards. Int. Conf. Nanotechnol. Renew. Mater. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Niu, M.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Y. Effect of Silica Sol Content on Thermostability and Mechanical Properties of Ultra-Low Density Fiberboards. BioResources 2015, 10, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grześkiewicz, M.; Borysiuk, P.; Kramarz, K. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Thermally Modified and Densified MDF. Int. Wood Prod. J. 2012, 3, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupciauskas, R.; Berzins, A.; Pavlovics, G.; Bikovens, O.; Filipova, I.; Andze, L.; Andzs, M. Optimization of Thermal Conductivity vs. Bulk Density of Steam-Exploded Loose-Fill Annual Lignocellulosics. Materials 2023, 16, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekounougou, S.; Kocaefe, D. Effect of Thermal Modification Temperature on the Mechanical Properties, Dimensional Stability, and Biological Durability of Black Spruce (Picea mariana). Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 9, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Xue, J.; Zhou, M.; Cao, J. Fungal Competition in Thermally Modified Scots Pine Wood as Related to Changes in Lignocellulosic Composition and Laccase Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, M.J.; Van Acker, J.; Tjeerdsma, B.F.; Kegel, E.V. Strength Properties of Thermally Modified Softwoods and Its Relation to Polymeric Structural Wood Constituents. Ann. For. Sci. 2007, 64, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tene Tayo, L.; Shivappa Nayaka, D.; Cárdenas-Oscanoa, A.J.; Euring, M. Enhancing Physical and Mechanical Properties of Single-Layer Particleboards Bonded with Canola Protein Adhesives: Impact of Production Parameters. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostendorf, K.; Ahrens, C.; Beulshausen, A.; Tayo, J.L.T.; Euring, M. On the Feasibility of a Pmdi-Reduced Production of Wood Fiber Insulation Boards by Means of Kraft Lignin and Ligneous Canola Hulls. Polymers 2021, 13, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzele, S.; van Herwijnen, H.W.; Griesser, T.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Rößler, C.; Konnerth, J. Differences in Adhesion between 1C-PUR and MUF Wood Adhesives to (Ligno)Cellulosic Surfaces Revealed by Nanoindentation. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, A.; Balma, F.X.Z.; Bond, B.H. Adhesive Bonding Performance of Thermally Modified Yellow Poplar. BioResources 2023, 18, 8151–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Ito, A.; Torikai, H. Effect of Porosity on Flame Spread along a Thin Combustible Solid with Randomly Distributed Pores. In Progress in Scale Modeling, Volume II: Selections from the International Symposia on Scale Modeling, ISSM VI (2009) and ISSM VII (2013); Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 303–314. ISBN 9783319103082. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.; Ito, A.; Torikai, H. Flame Spread along a Thin Combustible Solid with Randomly Distributed Square Pores of Two Different Sizes. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2012, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Qi, X.; Chen, N.; Zeng, Q.; Dai, D.; Fan, M.; Rao, J. Thermal Insulation Properties of Green Vacuum Insulation Panel Using Wood Fiber as Core Material. BioResources 2019, 14, 3339–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, K.; Wang, S. Effect of Porosity on Ignition and Burning Behavior of Cellulose Materials. Fuel 2022, 322, 124158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhou, L.; Han, G.; Huang, M.; Su, F.; Mi, L.; Feng, Y.; Liu, C. Effect of Morphology and Structure of Polyethylene Fibers on Thermal Conductivity of PDMS Composites. Polymer 2025, 323, 128194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Chen, J. Pore-Scale Conjugate Heat Transfer of Nanofluids within Fibrous Medium with a Double MRT Lattice Boltzmann Model. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2021, 163, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, G.; Tao, L.; Chen, Y. Effect of Moisture Absorption on High Temperature Thermal Insulation Performance of Fiber Insulation Materials. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 697, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Duan, L.M.; Xie, K. Thermal Conductivity Characteristics of Thermal Insulation Materials Immersed in Water for Cold-Region Tunnels. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 9345615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakalo, A.; Filpponen, I.; Rojas, O.J. Protein-Mediated Interfacial Adhesion in Composites of Cellulose Nanofibrils and Polylactide: Enhanced Toughness towards Material Development. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 160, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Notley, S.M.; Wågberg, L. Cellulose Thin Films: Degree of Cellulose Ordering and Its Influence on Adhesion. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.T.; Zhai, J.; Hoffmann, S.V.; Aguilar, M.I.; Augustin, M.A.; Wooster, T.J.; Day, L. Conformational Changes to Deamidated Wheat Gliadins and β-Casein upon Adsorption to Oil-Water Emulsion Interfaces. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 27, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalitha, S.; Srivastava, V.; Schmidt, L.E.; Deshpande, A.P.; Varughese, S. Multiscale Approach to Studying Biomolecular Interactions in Cellulose-Casein Adhesion. Langmuir 2022, 38, 15077–15087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, N.K.; Verbeek, C.J.R.; Bhattacharyya, D. A Novel Approach Utilising Phosphorylated Casein for Fire-Retardant and Formaldehyde-Free Medium Density Wood Fibreboards. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 215, 118608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wu, H.; Fan, L. Formation of Casein and Maltodextrin Conjugates Using Shear and Their Effect on the Stability of Total Nutrient Emulsion Based on Homogenization. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Ma, J.; Xu, Q. Research Progress on Functional Casein-Based Composites. Cailiao Daobao/Mater. Rep. 2019, 33, 2602–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z. Bonding Strength and Water Resistance of Starch-Based Wood Adhesive Improved by Silica Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S.; Woo, S.W.; Jeong, S.W.; Lee, D.E. Durability and Strength Characteristics of Casein-Cemented Sand with Slag. Materials 2020, 13, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urstöger, J.; Kain, G.; Prändl, F.; Barbu, M.C.; Kristak, L. Physical-Mechanical Properties of Light Bark Boards Bound with Casein Adhesives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoe, E.; Ghahremaninezhad, A. The Effect of Biomolecules on Enzyme-Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation in Cementitious Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristak, L.; Antov, P.; Bekhta, P.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Iswanto, A.H.; Reh, R.; Sedliacik, J.; Savov, V.; Taghiyari, H.R.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; et al. Recent Progress in Ultra-Low Formaldehyde Emitting Adhesive Systems and Formaldehyde Scavengers in Wood-Based Panels: A Review. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 18, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narskii, A.R. Investigations of Protein Casein Adhesives in 1927-1934 in Research Works of Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute and All-Russia Institute of the Aircraft Materials. Polym. Sci.-Ser. D 2010, 3, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemz, P.; Dunky, M. Bonding of Solid Wood-Based Materials for Timber Construction. In Biobased Adhesives: Sources, Characteristics, and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 621–658. ISBN 9781394175383. [Google Scholar]

- Mary, A.; Blanchet, P.; Pepin, S.; Chamberland, J.; Diouf, P.N.; Landry, V. Bio-Innovation in Wood Bonding: Sodium Caseinate as a Renewable Polyol Substitute. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, V.; Lucia, L.A.; Banerjee, S. Soy Flour and Soy Lecithin Improve Paper Strength and Formation. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2016, 31, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacharlerie, S.; Petrut, R.; Deckers, S.; Flöter, E.; Blecker, C.; Danthine, S. Structuring Effects of Lecithins on Model Fat Systems: A Comparison between Native and Hydrolyzed Forms. LWT 2016, 72, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fabià, S.; Torstensen, J.; Johansson, L.; Syverud, K. Hydrophobisation of Lignocellulosic Materials Part I: Physical Modification. Cellulose 2022, 29, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiros, T.N.; Antrobus, R.; Farías, D.; Chiu, Y.T.; Joseph, C.T.; Esdaille, S.; Sanchirico, G.K.; Miquelon, G.; An, D.; Russell, S.T.; et al. Microbial Nanocellulose Biotextiles for a Circular Materials Economy. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2022, 1, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, J.E.; Drake, G.L.; Barker, R.H. Pyrolysis and Combustion of Cellulose. III. Mechanistic Basis for the Synergism Involving Organic Phosphates and Nitrogenous Bases. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1972, 16, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyutikov, A.A.; Markina, V.Y.; Konoplenko, E.S. Flax Seed Lecithin—Chemical Composition and Prospects for Use. Khimiya Rastit. Syr’ya 2025, 2, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerich, G.; Koehler, P. Functional Properties of Individual Classes of Phospholipids in Breadmaking. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 42, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorf, D.; Bindrich, U.; Mischnick, P.; Juadjur, A.; Franke, K.; Heinz, V. Atomic Force Microscopy Study on the Effect of Different Lecithins in Cocoa-Butter Based Suspensions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 499, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estiasih, T.; Ahmadi, K.G.; Ginting, E.; Priyanto, A.D. Modification of Soy Crude Lecithin by Partial Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Phosholipase A1. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 843. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Li, W. Ammonolysis Modified Soybean Lecithin as a Drilling Fluid Lubricant. Drill. Fluid Complet. Fluid 2022, 39, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Van De Walle, D.; Petit, C.; Beheydt, B.; Depypere, F.; Dewettinck, K. Mapping the Chemical Variability of Vegetable Lecithins. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, H.I.; Chen, Y.; Smolentsev, N.; Zdrali, E.; Roke, S. Interfacial Structure and Hydration of 3D Lipid Monolayers in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 2808–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, N.; Constantinesco, I.; Yu, K.; Kizhakkedathu, J.N.; Brooks, D.E. Choline Phosphate Functionalized Cellulose Membrane: A Potential Hemostatic Dressing Based on a Unique Bioadhesion Mechanism. Acta Biomater. 2016, 40, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, J.V.; Crowley, M.F.; Beckham, G.T. A Quantitative Molecular Atlas for Interactions between Lignin and Cellulose. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 19570–19583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Sanyoto, B.; Choi, J.W.; Ha, J.M.; Suh, D.J.; Lee, K.Y. Effects of Lignin on the Ionic-Liquid Assisted Catalytic Hydrolysis of Cellulose: Chemical Inhibition by Lignin. Cellulose 2013, 20, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Blanchet, P. Effect of Vacuum Time, Formulation, and Nanoparticles on Properties of Surface-Densified Wood Products. Wood Fiber Sci. 2011, 43, 326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z. Impregnation Property across Carbon Fiber Stacks under Vacuum Pressure. Fuhe Cailiao Xuebao/Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2006, 23, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire-Paul, M.; Foruzanmehr, M.R. The Study of Physico-Mechanical Properties of SiO2-Impregnated Wood under Dry and Saturated Conditions. Wood Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Chui, Y.H.; Wan, H.; Bousmina, M. Wood Plastic Composites by Melt Impregnation: Polymer Retention and Hardness. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmazer, S.; Aras, U.; Kalaycıoğlu, H.; Temiz, A. Water Absorption, Thickness Swelling and Mechanical Properties of Cement Bonded Wood Composite Treated with Water Repellent. Maderas Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2023, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, F.; Wu, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, L. Assessment of Soybean Protein-Based Adhesive Formulations, Prepared by Different Liquefaction Technologies for Particleboard Applications. Wood Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkowiak, K.; Emmerich, L.; Militz, H. Wood Chemical Modification Based on Bio-Based Polycarboxylic Acid and Polyols–Status Quo and Future Perspectives. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.H.; Liu, H.L.; Yu, W.D. The Effect of Chemical Treatment on Sisal Fiber Property. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 821–822, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, I.; Farsi, M. Interfacial Behaviour of Wood Plastic Composite: Effect of Chemical Treatment on Wood Fibres. Iran. Polym. J. (Engl. Ed.) 2010, 19, 811–818. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, M.R.; Leman, Z.; Sapuan, S.M.; Rahman, M.Z.A.; Anwar, U.M.K. Impregnation Modification of Sugar Palm Fibres with Phenol Formaldehyde and Unsaturated Polyester. Fibers Polym. 2013, 14, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumowska, A.; Robles, E.; Kowaluk, G. Evaluation of Functional Features of Lignocellulosic Particle Composites Containing Biopolymer Binders. Materials 2021, 14, 7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, R.; Sweesy, W.; Jur, J.S.; Willoughby, J. Moisture Vapor Barrier Properties of Biopolymers for Packaging Materials. ACS Symp. Ser. 2012, 1107, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, G.; Bastida, G.A.; Tarrés, Q.; Corazza, M.L.; Ramos, L.P.; Delgado-Aguilar, M. Silylated Softwood and Hardwood Lignin: Impact on Thermomechanical and Interfacial Properties of PLA Biocomposites. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 7681–7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.S.; Abouzeid, R.; Shayan, M.; Kärki, T.; Wu, Q. Structural and Chemical Modification of Cellular Wood Composite for Enhanced Strength, Fire, and Biological Resistance. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 46965–46976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesov, N.G.; Varankina, G.S.; Shishlyannikova, A.B.; Rusakov, D.S. A Study of the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Modified Fire-Retardant Wood Materials. Polym. Sci.-Ser. D 2025, 18, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]