Abstract

In the context of green transition and digital transformation, forestry is becoming a strategic area of application of current modern technologies. The Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), big data analysis (Big Data) and Digital Twins define the basic infrastructure of smart forestry. By connecting sensors, drones and satellites, IoT allows for continuous monitoring of forest ecosystems, risk anticipation and decision optimization in real-time. The purpose of this study is to perform a comprehensive narrative analysis of the relevant scientific literature from the recent period (2020–2025) regarding the application of IoT in forestry, highlighting the conceptual, technological and institutional developments. Based on a selection of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (29 full-text articles), four major axes are analyzed: (A) forest fire detection and prevention; (B) climate-smart forestry and carbon accounting; (C) forest digitalization through the concepts of Forest 4.0, Forest 5.0 and Digital Twins; (D) sustainability and digital forest policies. The results show that IoT is a catalyst for the sustainable transformation of the forest sector, supporting carbon accounting, climate-risk reduction and data-driven governance. The analysis highlights four major developments: the consolidation of IoT–AI architectures, the integration of IoT and remote sensing, the emergence of Forest 4.0/5.0 and Digital Twins and the growing role of governance and data standards. These findings align with the objectives of the EU Forest Strategy 2030 and the European Green Deal.

1. Introduction

Forests represent one of the most important biological ecosystems on the planet, necessary for climate regulation, biodiversity conservation and maintaining hydrological balance at a global level [1,2]. They cover approximately 31% of the land surface and store over 80% of the carbon of continental biomass, playing a fundamental role in mitigating climate change and supporting ecosystem services [3]. However, forest reduction and degradation, increased fires and economic pressure on natural resources have determined the need to implement modern monitoring and planning tools [4].

In this context, forestry is in a stage of absolute digital transition, in which new technologies become levers of sustainability. This transformation takes place simultaneously with the green transition promoted at the European Union level, oriented towards ecological digitalization and the use of data as a strategic infrastructure [5,6]. Smart Forestry relies on the integration of Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), big data and digital twin technologies, which allow the observation and analysis of ecological processes in near-real time [7,8].

The digitalization of the forestry sector has accelerated the adoption of Internet of Things (IoT)-based technologies, supporting continuous monitoring and operational decision-making [9]. According to recent work, IoT-based environmental monitoring platforms can support soil moisture sensing, microclimate assessment, fire prediction and forest health monitoring, even though large landscapes still pose deployment and cost constraints [10,11].

In forestry, these networks provide continuous monitoring of microclimate, sap flows, moisture levels, and carbon parameters, supporting decision-making based on practical field studies [12]. Integration of IoT sensors with AI platforms also enables automated forest fire identification, biomass estimation, and ecological stress prediction [13,14]. IoT, AI and remote sensing technologies play an increasingly important role in detecting forest disturbances such as illegal logging, plant diseases and fire-risk conditions, providing real-time support for monitoring and prevention [15].

In parallel, LPWAN technologies (LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, Sigfox) offer long-distance transmissions with minimal energy consumption, allowing the observation of forests in mountainous or hard-to-reach areas [16]. In this way, digital forestry becomes not just a technological field, but a connected ecological infrastructure.

The concept of the Internet of Forest Things (IoFT) [16] extends the IoT paradigm to the forest ecosystem level, proposing a hybrid architecture that combines sensors, weather stations, drones and satellites. IoFT allows for the dynamic monitoring of biological and physiological processes in the forest, transforming it into an interactive digital ecosystem [17,18]. In recent years, this concept has been used and validated in numerous European and Asian projects, demonstrating its applicability in fire detection, carbon accounting and digitalization of forestry operations [19,20].

Recent research shows that the digital transformation of forestry depends not only on technological innovation, but also on how policies are interpreted and implemented across governance levels. A comparative topic-modeling study in China reveals that national, regional and operational policy layers often diverge in their emphasis and terminology, creating gaps that influence the adoption of smart forestry technologies [21]. These findings underline that digital forestry must be understood as both a technical and an institutional transformation, shaping how IoT systems, data infrastructures and Digital Twin frameworks are effectively integrated into forest management.

The digital transformation of forestry is also supported at a strategic level by the European Union Forestry Strategy 2030, which promotes the transition towards sustainable, digital and resilient forestry [22]. It encourages the development of digital wood traceability systems and the implementation of IoT platforms for automated carbon reporting and biodiversity monitoring [23]. The AI Act (2024) also sets out ethical principles for the use of artificial intelligence in high-impact sectors, including forestry [24]. At the EU level, the New EU Forest Strategy for 2030 and the European Green Deal position forests as key components for climate neutrality, biodiversity protection and a circular bioeconomy, emphasizing the need for improved digital monitoring and reporting tools. In this policy context, digital forestry refers to the broad use of digital tools and data infrastructures along the forestry value chain, including inventory, planning and operations, as outlined in recent analyses of digital transformation in forestry [25].

Smart forestry is more narrowly associated with sensor-rich, data-driven and adaptive management systems based on IoT and AI, a perspective supported by current smart forest monitoring research [19]. The Internet of Forest Things (IoFT) describes IoT architectures tailored to forest environments, in which trees, stands, machines and environmental parameters operate as interconnected nodes [7]. Forest 4.0 focuses on the integration of Industry 4.0 technologies—automation, robotics, big data and cyber-physical systems—into forestry operations [4], whereas Forest 5.0 extends this approach by incorporating human-centered, collaborative and ecological dimensions into digital forest governance [26,27].

Recent developments also point toward the emergence of data-driven Digital Twin applications in forestry [28] illustrate how remote sensing time-series data, combined with machine learning models, can be used to reconstruct and predict forest conditions, signaling a transition from conceptual digitalization frameworks to more operational, data-rich implementations. Such advances complement IoT- and AI-based monitoring systems and reflect the broader movement toward integrated, intelligent forest management.

Therefore, smart forestry is an interdisciplinary approach that connects technology with forest ecology and economics. IoT is no longer just a data collection tool, but a knowledge system, which transforms the forest into an adaptive system capable of learning and reacting [3].

In this context, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive narrative analysis of the scientific literature from 2020 to 2025 on IoT applications in smart forestry, exploring the technological, ecological and institutional dimensions of this process [11,12,29]. The selected studies reflect the maturing trend of research in the field of IoT–AI forestry, focused on fire detection, carbon accounting, digitalization of forestry processes and data integration in public policies [18,27,30].

The central objective of this research is to formulate an integrative perspective on how IoT contributes to increasing the resilience of forest ecosystems, making carbon accounting more efficient, and optimizing sustainable management decisions [31,32].

This review examines how IoT-based applications, remote sensing tools and digitalization frameworks contribute to the current development of smart forestry. Using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) selection of 29 peer-reviewed studies, this analysis is structured into four axes covering wildfire detection and prevention, climate-smart forestry and carbon accounting, digitalization through Forest 4.0, Forest 5.0 and Digital Twin concepts, and the role of digital forest policies and governance. This structure enables the identification of technological advances, operational approaches and governance-related factors discussed in the recent literature. This review also points to areas where links between sensing systems, data infrastructures and policy frameworks remain limited, indicating directions for future work on integrated digital forestry strategies.

This paper is structured in six sections: the first introduces the theoretical framework of forest digitalization; the second describes the methodology (PRISMA and selection criteria); the third synthesizes the results, divided into four thematic axes (A–D); the fourth provides a conceptual synthesis of the interconnection between technology and sustainability; the fifth presents limitations and future directions; and the last section includes conclusions, contributions and practical implications for the transition to Forest 5.0 [8,20,27]. All of this provides a coherent and integrated perspective on how digitalization can redefine forestry practices in the context of the transition to green and smart forestry. Thus, the research is not limited to identifying existing progress, but also outlines concrete directions for the development of smart, resilient and ecologically responsible forestry, providing a valuable framework for decision-makers, practitioners and researchers aiming for the sustainable implementation of Forest 5.0.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and General Approach

This paper adopts an integrative narrative approach, specific to review studies, according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) recommendations and the methodological guidelines formulated by Snyder [33]. Unlike a classic systematic review, which aims at quantitative synthesis, the narrative approach allows for critical analysis and the contextualization of results within a rapidly evolving interdisciplinary field, such as the digitalization of forestry [3]. This methodology is suitable for rapidly developing fields, where the diversity of technologies and indicators makes it difficult to apply quantitative meta-analysis [33]. The analysis focuses on identifying conceptual models, technical metrics and the ecological and social impacts of IoT use in forest management [11,29].

Although a PRISMA workflow was used to ensure transparency and consistency in the screening stage, the synthesis conducted in this review remains narrative. This methodological choice reflects the heterogeneity of the selected studies and the aim of structuring the findings along four thematic axes rather than performing a fully systematic evaluation.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted between July and November 2025, using the main international databases: Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, Science Direct, SpringerLink and MDPI platforms (Sensors, Forests, Remote Sensing).

To identify relevant articles in this field, the following keyword combinations were used: “forest monitoring IoT”, “smart forest”, “Forest 4.0”, “Forest 5.0”, “digital twin forestry”, “AI wildfire detection”, “IoT carbon sequestration”, “sustainable forest management IoT” and “IoT biodiversity monitoring”.

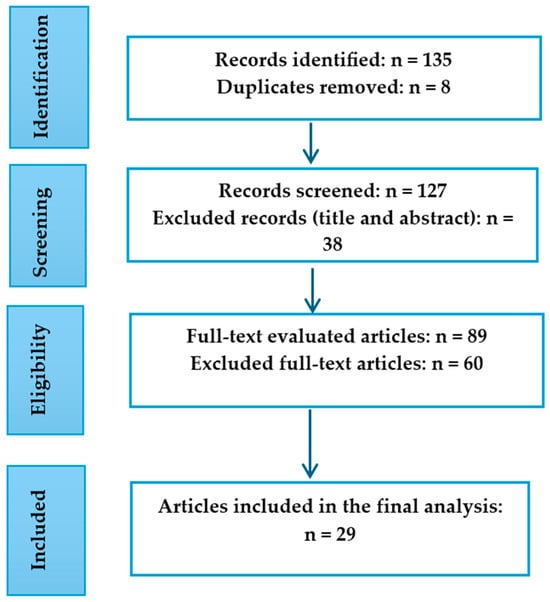

By applying these criteria, 135 publications dated between 2020 and 2025 were initially retrieved. After removing 8 duplicates, 127 records remained for screening. A total of 38 publications were excluded at the title–abstract stage because they lacked direct relevance to forestry applications. The remaining 89 full-text articles were then examined in detail, and 60 were excluded for not meeting the methodological scope of this review (e.g., non-forestry domains such as agriculture, horticulture or urban IoT, or insufficient methodological detail). The final corpus consisted of 29 peer-reviewed articles, which were included in the narrative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study identification and screening workflow (PRISMA).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure the consistency of the selection process, the following criteria were applied.

Inclusion criteria: articles published between 2020 and 2025 in Scopus/WoS indexed journals; studies with direct applicability in smart forestry (monitoring, carbon, fires, Digital Twins); articles available in full text; papers presenting experimental results, conceptual models or IoT performance evaluations.

Exclusion criteria: studies dedicated to precision agriculture without a forestry component; theoretical articles without experimental validation; publications not indexed or with incomplete data; works published before 2020 to ensure focus on recent and relevant research.

To improve transparency and reproducibility, a detailed record of all search operations was maintained. The full search strings, database-specific date stamps and the number of initial hits obtained from each source have been compiled in Appendix A, together with the screening steps that led to the final selection. The list of all 29 included peer-reviewed articles—each accompanied by DOI and access information—is also provided in the appendix, grouped according to the four thematic axes of this review. Grey literature (technical reports, project deliverables and preprints) was screened separately and reported narratively; however, these sources were not included in the final synthesis to ensure consistency with the methodological scope of this academic review.

2.4. Thematic Classification

The included articles were organized into four major thematic axes, reflecting the dominant directions of the current research (Table 1). The 29 full-text articles retained after the PRISMA screening constitute the empirical and conceptual core of this review. A complete list of these studies, including their thematic allocation to axes A–D, DOI and study type, is provided in Appendix A (Appendix A.4). Table 1 presents a synthetic overview of the thematic axes along with representative examples.

Table 1.

Classification of studies across the four thematic axes.

The number of eligible articles reflects the emerging stage of IoT-based forestry research and the focus on studies that directly evaluate or implement IoT systems in forest contexts.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each article included in the current study, information was extracted related to the type of technology used (sensors, protocols, microcontrollers); performance indicators (accuracy, autonomy, latency, costs); ecological objectives (fire monitoring, carbon accounting, tree health assessment); institutional and social implications (digital policies, acceptance, ethics).

The comparative analysis was carried out through synoptic tables and correlations between axes, identifying convergences and research gaps.

2.6. Methodological Limitations

The narrative approach has limitations in terms of replicability and generalizability, given the heterogeneous nature of the studies analyzed. However, it allows for an integrative perspective on a current and rapidly developing field, in which quantitative methods are still insufficient [33]. To reduce these limitations, the analysis was completed by triangulation: correlating technical data with conceptual and institutional ones, providing a coherent overview of contemporary forest digitalization [6,29].

This review also presents methodological limitations related to the specificity and early development of the research domain. The relatively small number of studies included does not result from an incomplete or insufficient search strategy, but rather from the deliberately narrow scope adopted. By combining IoT-related keywords strictly with forestry and smart forestry terms, and by limiting the selection to recent, peer-reviewed full-text articles that explicitly link IoT technologies to forest ecosystems, the search yielded a limited but highly relevant set of publications. Therefore, the modest size of the final corpus reflects the emerging and fragmented nature of IoT-based forestry research rather than a methodological weakness. Broader reviews that include generic IoT, environmental monitoring technologies, agricultural applications or grey literature would naturally identify a larger number of records, but would fall outside the focused research questions guiding this study.

3. Results

3.1. Axis A—Forest Fire Detection and Prevention

Forest fires represent one of the greatest threats to forest ecosystems, generating significant losses of biodiversity, carbon and ecosystem services [12]. In recent decades, their increased frequency and intensity, caused by climate change and inefficient land management, have led to the emergence of IoT monitoring and early warning systems capable of transmitting information in real time [11].

Studies highlight that IoT technologies can significantly enhance wildfire preparedness by enabling continuous environmental sensing, early warning capabilities and remote coordination of fire risk conditions. This transition from manual to digital fire management contributes to the creating of more resilient forest landscapes in the face of increasing climate pressures [6].

Recent research (2020–2025) has highlighted a clear transition from solutions based solely on simple sensors (DHT11, MQ6, BMP180) to AI-integrated IoT systems, capable of recognizing complex patterns and predicting events before they occur [12,39]. Hybrid AI–IoT models, such as the proposed real-time forest fire detection architecture [40] and the ESP32–LoRaWAN systems developed by Subbarayudu et al. [41] combine machine learning algorithms with low-power communication technologies, achieving 93%–96% accuracy in detecting fire conditions and maintaining an average latency below 3 s.

The recent literature shows a clear transition from basic environmental sensors used in early IoT wildfire detection prototypes—such as DHT11/22, MQ-series gas sensors or BME280, commonly reported in studies [41,42]—toward more advanced and integrated devices. Newer developments include the BME688 sensor with embedded gas classification machine learning [43], multi-gas electrochemical sensors used in recent wildfire monitoring studies [30], particulate matter sensors (PM1/2.5/10), as well as low-power thermal or optical imaging modules described by Pettorru et al. [44]. These devices offer higher accuracy and multi-parameter measurement capabilities, but require careful attention to calibration procedures, long-term drift, humidity and condensation effects and routine maintenance, as highlighted by Carta et al. [43]. Distinguishing between early low-cost components and current smart sensors clarifies their performance, reliability and applicability in real forest conditions.

Üremek et al. [11] showed that using a LoRa + BME280 network combined with ARIMA and Decision Tree models can provide accurate and energy-efficient detection, while Pedditi and Debasis [30] proposed an EERP protocol that extends the lifetime of networks by over 35%. Similarly, Ayansoku [45] developed a low-power IoT system for monitoring vibrations and noise in tropical forests, with dual applicability for fire detection and illegal logging prevention.

For example, Jayasingh et al. [12] proposed a LoRaWAN-based IoT system with 92.4% accuracy in smoke detection, powered by solar panels and with an autonomous operational period of 18 months, demonstrating that autonomous solutions can operate in the long term without maintenance.

Beyond LoRa/LoRaWAN and NB-IoT, recent studies emphasize additional LPWAN technologies that may be relevant for forest monitoring under diverse environmental and regulatory conditions. Previous research [46] provides a detailed comparison of LPWAN standards, including Sigfox, showing important differences in transmission range, duty-cycle restrictions, energy consumption profiles, payload limitations and cost structures. Complementary work [47] demonstrates that LoRa-Mesh architectures can extend coverage and improve energy efficiency in forested terrain, while highlighting how attenuation, multipath propagation and gateway placement influence throughput and latency under dense canopy.

In parallel, it was shown how satellite-derived information can complement terrestrial LPWAN links within hierarchical sensing architectures, supporting resilience in areas where ground connectivity is constrained by topography or vegetation [48]. Taken together, these contributions offer a broader and more nuanced perspective on communication strategies for fixed sensor nodes, mobile platforms and UAV-assisted monitoring in forest ecosystems. Additionally, AI applications based on machine learning and image recognition (CNN, Random Forest, SVM) have been used for visual detection of smoke and thermal anomalies. Hybrid IoT–AI models have significantly reduced false alarms by combining data streams from gas sensors and thermal cameras [32].

The current trend is to move from isolated networks to integrated ecosystems, in which sensors on the ground communicate with drones, satellites and cloud platforms, forming a multi-level hierarchical architecture. Thus, data collected on the ground are validated by aerial and satellite observations, increasing spatial accuracy and reducing detection errors [18].

For difficult to access mountainous areas, LoRaWAN systems have proven to be superior in terms of energy efficiency, with a transmission range of 6–12 km and consumption below 1 W per node [30]. In contrast, NB-IoT solutions offer superior stability but higher operating costs, making them more suitable for permanent fixed networks [11].

Methodologically, the literature confirms (Table 2) the migration from static networks to dynamic and multi-level IoT systems, where data from sensors, drones and satellites are integrated into a common flow for cross-validation and reduction of false alarms [13,14,49].

Table 2.

IoT systems for forest fire detection and prevention (2020–2025).

Through these innovations, IoT becomes a central element of predictive forestry, significantly contributing to the modeling of thermal parameters of ecosystems and real time risk management [8,27].

Recent studies highlight the convergence towards IoT + ML systems with multi-parameter sensors and LPWAN protocols (LoRa/NB-IoT) for high coverage and low power consumption, respectively, with Wi-Fi remaining for prototypes or restricted perimeters [11,12,39]. The integration of ESP32/ARM with sensors such as BME280, DHT11/DHT22, MQ-6 and, in some cases, GPS + mobile applications, allows for rapid alerting and operational traceability, creating an efficient framework for intelligent environmental surveillance [41].

In the field of communications, LoRa dominates due to its optimal compromise between range and power consumption. LoRa + BME280 implementation with ARIMA/Decision Tree models has shown a power reduction of approximately 40% while maintaining detection accuracy [11]. Field-validated long-range, low-power devices support stable connectivity over distances of over 10 km and allow the expansion of the network for monitoring and securing perimeters, and vibration and noise detection [45]. Wi-Fi solutions remain useful for testbeds, with low latencies but limited autonomy [39].

At the algorithmic level, moving from fixed rules to ML models (MLR, Random Forest, ANN) increases detection accuracy; the previously evaluated IoT platform [12] reports 93%–96% accuracy in experimental scenarios. On-edge ML reduces false alarms and stabilizes alerts [42]. ARIMA + Decision Tree models are effective for predicting pre-fire conditions in low-power networks [11]. Recent work in IoT-based wildfire detection shows that computation is increasingly distributed across the chain sensor → edge node → gateway → cloud. Several studies included in Axis A demonstrate the feasibility of lightweight inference directly on low-power microcontrollers [11,30]. It is shown that ARIMA and Decision Tree classifiers can operate locally on constrained devices, enabling rapid anomaly screening and reducing communication overhead [12,41]. Researchers report that integrating on-edge ML with multi-parametric sensing improves alert stability and reduces false alarms, achieving accuracy levels above 90% in experimental forest monitoring scenarios.

Gateway-level processing is also described in studies [39], where aggregated multi-sensor inputs allow for more complex inference routines and support faster confirmation of alerts. Recent implementations presented by Nevatia et al. [48] illustrate how combining IMU, gas or optical data streams at the gateway enhances robustness under variable field conditions. Across these systems, commonly reported evaluation indicators include node-level latency, energy-per-inference cycle, time-to-alert and false-positive reduction, which together provide a clearer characterization of performance in AI-enabled forest monitoring architectures.

Field validation confirms its practical utility: a previous study [32] reports an accuracy of over 92% in mixed vegetation, but notes the sensitivity to radio interference. Furthermore, Haque and Soliman [50] go beyond detection, introducing fire evolution prediction (temporal ML model), which facilitates preventive and planned risk management.

From an energy efficiency perspective, the EERP protocol proposed by Pedditi and Debasis [30] reduces consumption by ~35% and extends network lifetime by ≈40% in multi-hop WSN scenarios, a critical difference for autonomous field deployments.

Overall, LoRa + ML configurations offer the best accuracy–power scalability ratio, ensuring sub-second latencies and 12–18 months of autonomous operation in real-world conditions. Hybrid IoT–AI–UAV systems can raise accuracy above 94%, but require more consistent energy and computational infrastructure [13]. The development direction is the integration of networks in edge cloud architectures and interconnection with satellite/UAV imagery and Digital Twins, with a focus on explainable AI (XAI) for decision traceability [8,27].

Despite these technological advances, studies included in Axis A also report several operational constraints that affect the feasibility and long-term performance of IoT-based wildfire detection systems. Sensor longevity can be reduced by prolonged exposure to heat, humidity or particulate matter, and communication links may become unstable in mountainous terrain or under dense canopy. Several implementations remain susceptible to false positives caused by smoke, dust or fluctuating microclimatic conditions. Long-term deployment also requires stable energy supply, periodic maintenance and reliable field calibration procedures, which continue to influence the scalability and robustness of these systems in real forest environments.

3.2. Axis B—Climate-Smart Forestry and Forest Carbon Accounting

In the recent literature, forest carbon monitoring is approached by integrating multi-sensor data, forest inventories and ecosystem models, generating advanced tools for assessing carbon stocks and flows in climate-smart contexts. Experimental results illustrate the influence of stand structure and management intensity on carbon stocks, with significant variations in aboveground biomass observed in peri-urban forests [3]. Remote sensing methods combined with machine learning algorithms have led to highly accurate estimates of biomass and its long-term changes [35], while operational systems implemented at a regional scale have allowed the quantification of carbon fluxes and the effects of harvesting and fires on the ecosystem balance [51]. In addition, multi-sensor analyses have highlighted the variability of algorithm performance depending on forest type and structural characteristics, highlighting the need for specific spatial calibrations for biomass mapping [34].

At the experimental level, a study by Braga et al. [3] demonstrated that the structure and management history determine significant differences in carbon stocks. According to the results, low-SI forests presented the highest biomass values, reaching 41–251 t C/ha, with an average of 119 t C/ha, while no-SI forests recorded the highest annual carbon growth rates [3]. These results show that the intensity of forestry interventions influences stocks (AGB) and annual flows (CSC) differently, confirming the need for differentiated management strategies in a climate-smart context.

On the remote sensing and modeling side, Esteban et al. [35] used ALS and Landsat images combined with Random Forest algorithms, achieving high accuracy in estimating aboveground biomass (R2 = 0.82–0.86). The study also provides multi-temporal values of biomass change (ΔAGB = 15.11 ± 3 Mg/ha), which allows the use of this type of modeling in assessing carbon stock variations over time. The major advantage is its applicability in large areas, where detailed inventories are costly.

At regional and national scales, Zhou et al. [51] developed one of the most advanced operational systems, the National Forest Carbon Monitoring System (NFCMS), integrating FIA, Landsat, LiDAR, InSAR data and ecosystem models (CASA, WoodCarb II). The results showed a high correlation with independent products (r = 0.96, RMSE ≈ 0.5 kg C/m2). During the analyzed period, the forests of the Pacific Northwest acted as a net sink of 18.5 Tg C/year, with a major contribution from harvesting, which generated an equivalent loss of over 75% of the NEP, and from fires, responsible for emissions of 16.6 Tg C (2002) and 7.1 Tg C (2006) [44].

In the direction of methodological comparison, Antropov et al. [34] analyzed the performance of satellite sensors (Sentinel-1/2, TanDEM-X, ALOS-2) and ML algorithms (RF, SVR, k-NN), reporting large variations in accuracy depending on the forest type, density range and combination of sensors used. Biomass estimates show an accuracy between 20 and 50%, highlighting the fact that local ML models have a superior performance compared to global models, when there are no specific calibrations for each type of ecosystem.

Regarding digital infrastructure, Buonocore et al. [17] proposed a Forest Digital Twin that combines IoT, remote sensing and advanced analytics to support MRV processes. Although the work is conceptual in nature and does not include experimental validations, it represents an essential step in defining the technical architecture necessary for the development of integrated carbon storage systems.

In addition, Venanzi et al. [20] addressed the role of IoT, GNSS, LiDAR and forest monitoring systems in optimizing sustainability, providing a complementary technological basis for climate-smart forest management. Although they do not directly estimate carbon, the tools used indirectly influence the carbon balance by improving operational efficiency and reducing the impact on ecosystems.

Overall, the synthesis of the studies analyzed reveals three major findings regarding carbon monitoring in forests:

- Quantifying carbon fluxes requires integrated systems based on the combination of forest inventories, multi-sensor remote sensing and ecosystem modeling [51];

- The use of ALS/optical images in combination with machine learning algorithms provides real estimates of aboveground biomass and its variations over time [35];

- Forest management practices significantly influence the distribution and dynamics of carbon stocks, with clear differences between the forestry intervention systems applied [3].

The comparative analysis of the six studies in the literature (Table 3) highlights important differences in the way forest carbon is assessed and interpreted, depending on the scale of analysis, data sources and objectives of each study. Studies operating at the stand level accurately reflect the sensitivity of carbon stocks to structural features of stands and the history of forestry interventions. In this sense, the results of Braga et al. [3] show a high internal variation of the indicators, highlighting the fact that local parameters, such as the composition and density of stands, generate differences that cannot be captured by generalized models.

Table 3.

IoT systems for carbon accounting and climate monitoring (2020–2025).

In contrast to this local perspective, Esteban et al. [35] demonstrate that models based on remote sensing and machine learning provide stable and reproducible predictions over time, which is essential for large-scale monitoring of biomass trends. However, the authors emphasize that the accuracy of these methods depends on the availability of ALS data and the uniformity of conditions at the regional level.

The large-scale results presented by Zhou et al. [51] highlight another fundamental aspect: ecosystem fluxes are much more sensitive than stocks to natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Fires and harvesting rapidly influence the carbon budget, generating considerably more pronounced interannual variations than those observed in studies focusing exclusively on stocks. Similarly, Antropov et al. [34] showed that estimates derived from radar and optical sensors are influenced by forest type and structural heterogeneity, emphasizing that the accuracy of mappings depends on contextual calibration and the simultaneous integration of multiple data sources.

The conceptual studies by Buonocore et al. [17] and Venanzi et al. [20], although not providing numerical results, complement the empirical results by highlighting the technological infrastructures required for implementing MRV systems and operational monitoring. These results confirm that the effective implementation of carbon monitoring requires both hardware sensor components and digital systems that support integrated data flows.

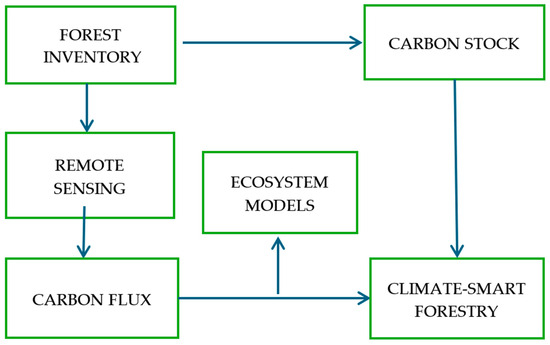

Overall, comparing the results (Figure 2), it is observed that local studies capture the structural variability of ecosystems, ML ones capture regional spatial trends, and multi-sensor systems highlight the impact of disturbances on carbon fluxes, each contributing complementary to the understanding of carbon accounting in the context of climate-smart forestry.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework illustrating the three complementary scales of forest carbon monitoring identified in the reviewed studies: (1) local stand-level assessments detecting structural variability and management effects; (2) regional remote sensing and machine learning approaches capturing spatial patterns and multi-temporal biomass change; and (3) integrated national systems providing annual carbon flux estimates and assessing the sensitivity of forest carbon balance to disturbances.

Despite these advancements, IoT-based carbon and biomass monitoring systems presented in Axis B face several limitations. Biomass estimation accuracy remains sensitive to site-specific variability, allometric assumptions and environmental noise, which can lead to uncertainty in carbon calculations. Sensor-based measurements often require frequent calibration to maintain stability over time, while differences in canopy structure, species composition and microclimatic conditions reduce the transferability of machine learning models across forest types and biomes. These factors continue to influence the generalizability and robustness of IoT-supported climate monitoring approaches.

3.3. Forest Digitalization: Forest 4.0, Forest 5.0 and Digital Twins

Forest digitalization is a strategic direction in the modernization of the forestry sector, integrating advanced technologies such as IoT, artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, data infrastructures and high-precision modeling. Within the Forest 4.0 concept, the specialized literature emphasizes the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in forestry processes, including automation, robotics, big data analysis and intelligent sensor networks, which allow for the optimization of operational flows and increased efficiency [25,36]. Forest 5.0 extends this approach by integrating socio-technical components, participatory governance and collaborative data infrastructures, thus contributing to increasing decision making transparency and developing a sustainable digital framework [6,26].

To clarify the conceptual boundaries within Axis C, the distinction between technological infrastructures, organizational transformations and socio-technical frameworks is important. IoT architectures, cyber-physical systems and distributed sensing platforms constitute the technological layer that enables data acquisition and integration. Organizational transformations refer to workflow automation, digitalized operations and interoperability across forest management processes.

The socio-technical dimension encompasses the broader paradigms of Forest 4.0 and Forest 5.0, which combine technological capabilities with human-centered, collaborative and sustainability-oriented principles. Within this structure, Digital Twins can be positioned as advanced decision-support tools that integrate real-time sensing, simulation and predictive modeling, linking operational technologies with strategic forest governance objectives.

Recent advancements in forest digitalization also include data-driven approaches to Digital Twin construction. Anterior study [28] demonstrates how Landsat time-series imagery combined with machine learning models can be used to reconstruct and predict forest canopy dynamics, illustrating an operational pathway for developing Digital Twins based on remote sensing data. This perspective complements existing conceptual frameworks and highlights the emergence of increasingly implementable, data-rich digital infrastructures in forestry.

Technically, the implementation of IoT networks provides the infrastructure necessary for continuous monitoring of ecological and operational processes, facilitating real-time data collection and their connection to scalable cloud platforms [7]. The integration of multispectral, optical and IoT sensors into a coherent monitoring system is necessary for the digital transformation of the forestry domain, as it allows for consistent and interoperable data flows, usable in intelligent decision-support systems [19].

Digitalization across the forestry value chain depends directly on this interoperability, with Müller and Jaeger [36] demonstrating that the integration of operational data with automated control systems increases traceability and optimizes forestry logistics. At the same time, Roberts and Damaševičius [25] emphasize that the implementation of Forest 4.0 requires the standardization of digital infrastructures and their integration with AI technologies to enable adaptive management processes.

In a rapidly evolving context, digital transformation includes the use of simulation systems and Digital Twins, which allow for the anticipation of ecosystem behavior, testing of future scenarios and optimizing decisions in this field. Buonocore et al. [17] propose a complete architecture for the Forest Digital Twin, based on the integration of multi-sensor streams, 3D models and analytical algorithms, demonstrating that these systems can reproduce forest dynamics in real time.

This perspective is further illustrated by Bryan-Elliot Tam et al. [52], who show that Digital Twins used in the training of forest operators improve performance, accuracy and safety in the field. Hoppen et al. [4] demonstrate complementary that the integration of intelligent machines and automated systems in harvesting contributes to the standardization of operational processes, facilitating their realistic simulation through advanced digital platforms. At a conceptual level, Gabrys [26] highlights the role of distributed data infrastructures and digital governance in configuring smart forest ecosystems, emphasizing that Digital Twins are not only technical tools, but also socio-technical devices for multisectoral coordination and management.

Overall, the literature shows that forest digitalization evolves on three interdependent levels: the development of Forest 4.0 infrastructure through IoT, sensors and automation; the expansion towards Forest 5.0 through digital governance and participatory processes; and the integration of Digital Twin technologies, which allow the simulation, anticipation and optimization of forestry processes in a dynamic and connected framework.

Operationalizing a Forest Digital Twin requires adopting formalized data structures and metadata standards to enable the synchronization of heterogeneous forest datasets across space and time. In current smart forestry practice, commonly used standards include OGC Observations and Measurements (O&M) for structuring IoT time-series [53], ISO 19115 for geospatial metadata documentation [54], and EPSG-compliant spatial reference systems for the alignment of field plots, stands and compartments. Semantic descriptions of sensors and observations are typically based on the W3C SSN/SOSA ontology, which supports machine-readable interpretation and interoperability across platforms [55]. Such requirements are consistent with the digital integration approaches described in recent smart forest monitoring studies.

Digital Twin implementations documented in Climate-Smart Forestry applications outline multi-layer computational architectures in which edge nodes perform basic filtering, gateways validate and harmonize sensor streams, and cloud infrastructures handle storage, spatiotemporal indexing and simulation routines (e.g., disturbance or biomass forecasting). These components align with the IoT–RS integration models previously described [18] and with the Forest 4.0 architectures presented by scholars [4].

Deployment is generally developed in stages, beginning with the stabilization of IoT data ingestion pipelines, followed by the integration of satellite or aerial remote sensing products, and subsequently the incorporation of simulation modules for growth dynamics or disturbance analysis [4].

Governance-oriented studies also highlight the need to consider privacy, security and data provenance, especially where high-frequency IoT streams or sensitive geospatial data are involved. Although blockchain-based mechanisms have been proposed for ensuring immutability and transparent reporting, their applicability in forestry remains limited by scalability and governance constraints [17].

Interoperability with Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) frameworks depends on using open geospatial standards, harmonized metadata schemas and reproducible processing pipelines that support consistent carbon-accounting workflows.

The results of the studies analyzed in Axis C (Table 4) highlight a convergent evolution of forest digitalization, in which Industry 4.0 technologies, data infrastructures, socio-technical processes and Digital Twins interconnect to create intelligent forest ecosystems. At the operational level, Roberts and Damaševičius [25] define Forest 4.0 as a structural transformation in which sensors, artificial intelligence, robotics and big data analytics enable the optimization of forest flows. These foundational concepts are empirically confirmed by Müller and Jaeger [36], who demonstrate that digitalization of the wood supply chain increases traceability, reduces operational uncertainties and improves logistical coordination by connecting equipment and automating processes.

Table 4.

Systems and concepts for forest digitalization (Forest 4.0, Forest 5.0, Digital Twins).

In terms of governance and institutional frameworks, Brunori et al. [6] show that sustainable digitalization depends on the capacity of rural ecosystems to integrate data infrastructures, participatory processes and collaborative platforms. In the same socio-technical direction, Gabrys [26] highlights the role of data infrastructures in the development of “smart forests”, arguing that digitalization is not only a technical process, but also one of reconfiguring institutional relationships and modes of organization. The results of these works indicate that Forest 5.0 is developing and defining itself as a stage in which digital technologies are interconnected with social, decision making and participatory management processes.

Regarding the technical monitoring infrastructure, Singh et al. [7] demonstrate, through a functional IoT prototype, that sensor networks can monitor microclimatic and operational parameters in real time, providing support for adaptive management. In addition, Ehrlich-Sommer et al. [19] show that the integration of multispectral, optical and IoT sensors into a coherent digital transformation architecture allows for the achievement of interoperable data flows, necessary for the development of advanced applications, including Digital Twins. The works converge towards the idea that IoT infrastructure represents the indispensable technical foundation for advancing the digitalization of the forestry sector to higher stages.

In the area of Forest 4.0 operationalization, Hoppen et al. [4] highlight that the application of smart machines and automated systems in harvesting leads to efficiency gains, reduction of human errors and standardization of processes, thus facilitating the integration of operational data into digital systems. These results indicate that operational digitalization constitutes the technical basis for the simulation and optimization of forestry interventions.

Regarding state-of-the-art technologies, Buonocore et al. [17] propose a complete architecture for Forest Digital Twin, in which multi-sensor streams, 3D models, RS systems and artificial intelligence are integrated to create a virtual replica of the forest ecosystem. This framework is operationally validated by Bryan-Elliot Tam et al. [52], who demonstrate that the use of a Digital Twin for operator training significantly improves performance, accuracy and safety in the field. The results of these two studies indicate that Digital Twins represent the most advanced stage of forest digitalization, as they allow for realistic simulation of processes, evaluation of management scenarios and optimization of decision support.

Complementary to these conceptual and simulation-based approaches, there are studies [28,49] that provide an operational demonstration of a data-driven forest Digital Twin using Landsat 7 time-series imagery. Their LSTM-based model reconstructs and predicts canopy dynamics over time, illustrating how remote sensing data and machine learning can support the development of implementable DT architectures for spatiotemporal forest monitoring.

Although progress is significant, the literature indicates the existence of structural limitations. Roberts and Damaševičius [25] highlight the lack of standardization of Forest 4.0 infrastructures, and research by Müller and Jaeger [36] shows that data interoperability remains a major challenge in this area. Brunori et al. [6] and Gabrys [26] emphasize that the implementation of Forest 5.0 requires digital skills and stable data ecosystems, while Singh et al. [7] and Ehrlich-Sommer et al. [19] show that the reliability of IoT depends on field conditions and connectivity. At the same time, Buonocore et al. [17] and Bryan-Elliot Tam et al. [52] show that Digital Twins require large databases and high computing resources, which limits their wide scaling. Overall, the digitalization of forests is a promising process, but it depends on standardization, interoperability and coherent integration of Forest 4.0, Forest 5.0 and Digital Twin technologies.

3.4. Axis D—Sustainability and Digital Forest Policies

Axis C focuses on the technological layer of forest digitalization, including IoT infrastructures, Forest 4.0 and Forest 5.0 models and Digital Twin systems. Axis D addresses the governance layer, in which “digital forest policies” denote the institutional frameworks, regulatory instruments and strategic mechanisms that guide the adoption and implementation of these technologies. In conceptual terms, Axis C outlines what the technological systems consist of and how they function, while Axis D explains how these systems are incorporated into policy processes, sustainability objectives and operational management structures.

The feasibility of IoT-based forest monitoring is increasingly shaped by emerging European regulatory frameworks. The EU AI Act establishes transparency, risk-management and documentation requirements that directly affect AI-enabled sensing systems, while the Data Governance Act and the European Data Strategy define conditions for data sharing, interoperability and public–private data reuse. Likewise, the EU Forest Strategy 2030 and associated monitoring initiatives emphasize the need for harmonized indicators, MRV-ready datasets and open digital infrastructures. These regulatory provisions influence the design of IoT architectures by requiring standardized data flows, traceable processing pipelines and clear governance mechanisms, thereby linking policy objectives to the technological developments described in Axes A–C.

In terms of sustainability and forest policies, digital technologies bring to the fore not only the technologies themselves, but also how they are integrated into strategies, organizational rules, data standards and professional training. At the national level, Stewart and Hartley [38] show, based on interviews with representatives from universities, research organizations and forestry companies in New Zealand, that the forestry sector is facing an “unprecedented potential” of data and collective learning, with the expansion of remote sensing, UAVs and data science tools. The authors explicitly discuss the idea of a unified vision of the forest resource at a national scale, in which forest inventories, wood flows and value chains are integrated into a common digital environment, and emphasize that the future of forestry work will require teams with advanced digital skills, not just “a single GIS or remote sensing specialist” [56].

In technological terms, while also carrying clear policy implications, Buonocore et al. [17] propose a Forest Digital Twin (FDT) framework that combines tree- and stand-level state variables with remote sensing data and ecosystem monitoring tools. The authors start from the Digital Twin definitions used in Industry 4.0 and argue that an FDT should be based on the integration of historical and real-time data, continuous synchronization between the physical and virtual components and the use of technologies such as blockchain to manage transactions associated with ecosystem services [17]. This perspective places forest digitalization in a framework for organizing data and ecosystem value, in which traceability, transparency and fairness in reporting become essential conditions for MRV policies and payment schemes for ecosystem services.

The IoT approach is explicitly extended to sustainability in Abdul Salam’s [57] chapter, which discusses the notion of the Internet of Things for Sustainable Forestry as part of a transition to “digital forestry.” The author defines digital forestry as a framework that connects forest information at local, national and global levels through an organized digital network and highlights both the potential of IoT for monitoring fires, pests, fragmentation and soil erosion, as well as the challenges related to very large areas, limited resources and poor infrastructure in forest areas [58].

IoT is presented as a key technology for monitoring and early warning systems, but also as a fundamental element in connecting conservation, production and risk indicators with the broader framework of sustainable development and global goals [37].

The literature on smart urban forests is shifting the discussion away from technical architectures towards considerations of ethics, justice and governance. Nitoslawski et al. [59] examines how smart technologies, from sensors and monitoring platforms to data analytics, are integrated into the “smart cities” discourse, highlighting that urban forests are important components of green infrastructure, but that their management is constrained by a lack of standards, fragmentation of responsibilities and the difficulty of integrating into urban planning.

In a complementary direction, Prebble et al. [56] apply a “more-than-human” lens to examine urban forest management policies and documents in Australian cities, showing that digitalization through the collection and use of “tree data” and what the authors call “lively data” is closely linked to how the relationships between people, trees and digital infrastructure are defined [57].

Advances in digital forest governance also include the integration of optimization algorithms for planning and decision support; recent work demonstrates that modified A-Star models can enhance sustainability by reducing operational costs, minimizing road use and limiting ecological disturbance in forest landscapes [60].

At a conceptual and normative level, Nitoslawski’s [61] thesis proposes an exploration of “smart forests” and data practices in urban forest management, treating forests as socio-technical infrastructures in which the way data are collected, stored and used influences decision-making and the distribution of benefits. The author explicitly emphasizes the need for principles of “data justice” in urban forest governance, linking digitalization to transparency, accountability and inclusion in planning processes [59].

In a vision of integrated urban policy, Russo [37] proposes a framework for “nature positive smart cities” based on a socio-technical ecological system (STES), arguing that smart technologies can support ecosystem services and biodiversity in urban green spaces only if they are deliberately oriented towards conservation and ecological equity objectives. The study highlights that future urban planning must integrate digital infrastructure with green and blue infrastructure, and include policies that prioritize biodiversity and climate change adaptation.

Digital governance has become a key determinant of how smart forestry technologies are implemented in practice. A recent comparative study shows that policy layers—national, regional and operational—often differ in focus and terminology, creating gaps that influence the uptake of digital tools in forestry [21]. These insights highlight that digital transformation depends not only on technological capacity, but also on policy coherence and institutional alignment. Axis D therefore explores how governance structures, regulatory frameworks and organizational processes shape the effective adoption of digital innovations in the forestry sector.

Overall, these contributions show that digital forest sustainability and policies cannot be reduced to the adoption of IoT technologies or Digital Twins, but involve rebuilding the data governance framework, defining standards and structures to support reporting and financing of ecosystem services [17,58] and integrating social and ecological justice dimensions into forest and urban forest management [37,56,59,61]. In addition, strategic visions for the future of the forest sector, such as the one formulated for New Zealand, emphasize that professional training and the development of digital skills are becoming sine qua non conditions for harnessing the “unprecedented potential” of forest data [38].

The studies analyzed in Axis D (Table 5) show that forest digitalization is evolving simultaneously on two interdependent levels. On the one hand, there is a direction oriented towards the development of digital infrastructure necessary for data management, standardization and reporting, highlighted in the works of Stewart and Hartley [38], Buonocore et al. [17] and Salam [58].

Table 5.

Articles included in Axis D—digital sustainability, governance and future forest policies.

On the other hand, the literature emphasizes the importance of the normative, ethical and institutional framework that structures the organization of forests and urban forests, coherently highlighted in the contributions of Nitoslawski et al. [59], Prebble et al. [56], Nitoslawski [61] and Russo [37]. Together, these studies show that digital forest sustainability cannot be understood only through the lens of technology, but requires a balance between technical infrastructure and social, institutional and ethical processes that condition the responsible adoption of technologies in this field.

A central element that differentiates the directions addressed is the way in which digital infrastructure is conceptualized. Stewart and Hartley [38] describe the process of digitalization as a broad sectoral transformation, emphasizing the role of data as a strategic resource and the need for a unified framework for professional training. They highlight that the future of the forest sector depends on the existence of a shared national vision, in which technology, skills and institutional collaboration are integrated into a coherent ecosystem.

In contrast, Buonocore et al. [17] focus on the technical architecture of a Forest Digital Twin, where real-time data synchronization, multi-sensor information integration and the use of blockchain for traceability contribute to the consolidation of a robust monitoring and reporting system. In this perspective, digitalization becomes an infrastructure for organizing ecosystem value, and digital technologies function as a support for MRV processes and for eventual markets for ecosystem services.

Salam’s [58] contribution is positioned between these two main directions, analyzing the potential of IoT to support sustainable management by connecting the technical architecture to the international criteria and indicators of the Montréal Process C&I. This approach operates both at a technical level, by describing IoT applications for monitoring fires, pests or water stress, and at a strategic level, by arguing for the role of IoT in modernizing ecological reporting and assessment systems. Compared to the macro-strategic approach proposed by Stewart and Hartley [38] and the Digital Twin architecture presented by Buonocore et al. [17], Salam’s [58] work provides a framework for linking technological infrastructure and international standards for forest sustainability.

In the literature on smart urban forests, digitalization is analyzed in a much more critical manner and more oriented towards the social and ecological implications of modern technology. Nitoslawski et al. [59] identify structural difficulties, such as fragmentation of institutional responsibilities and the absence of common data standards, which limit the integration of urban forestry into smart city initiatives. Prebble et al. [56] offer a conceptual perspective in which urban forests are treated as “more-than-human” socio-technical arrangements, in which trees, people, sensors and digital infrastructures are interconnected, and applied forest policies must take into account the dynamics of these relationships.

Nitoslawski’s thesis [61] explores how data practices influence the structure of urban forests, highlighting that the processes of data collection, storage and processing can lead to forms of exclusion or perpetuate inequalities. The concept of “data justice” thus becomes a fundamental element for the integration of digital technologies into fair and transparent decision-making processes. Russo [37] builds a complementary direction, arguing that smart cities must be oriented towards “nature-positive” objectives and that smart technologies can contribute to the expansion and improvement of green and blue infrastructure only if they are integrated with coherent and multiscale urban policies.

Complementing this distinction, it was observed [21] that digital forestry policies often diverge across national, regional and operational levels, creating semantic and organizational gaps that affect the implementation of smart forestry tools. Their comparative topic-modeling analysis reinforces that effective digital transformation requires not only robust technical infrastructure, but also coherent policy alignment and institutional coordination across governance scales.

Overall, these contributions suggest that the notion of digital forest transformation should be understood as an interaction between two spheres: the technical infrastructure, which supports data collection and management, and the socio-political framework, which determines how these technologies are implemented, accepted and regulated. Infrastructure-oriented studies show the technological potential of digitalization in reporting, evaluation and optimization, while critical literature on urban forests highlights the limits, risks and responsibilities associated with data use. Consequently, a coherent vision of digital forest sustainability requires the integration of these two planes into a structure that includes both technical standards and mechanisms for participation, transparency and ecological justice.

This perspective is consistent with the objectives of the EU Forest Strategy 2030, which include strengthened forest monitoring, increased climate resilience, biodiversity protection and transparent, interoperable forest information systems. It is also aligned with the priorities of the European Green Deal, where digital innovation, particularly IoT-based monitoring and MRV frameworks, supports decarbonization, sustainable resource use and ecological transition. Digital forest policies therefore function as a mechanism for integrating the technological developments described in Axis C into coherent, scalable and sustainability-oriented management practices.

4. Limitations and Future Directions

The reviewed literature highlights important limitations of the current research in the field of IoT applied to forestry. A significant part of the studies is based on short-term experiments, carried out under controlled or semi-controlled conditions, which reduces the relevance of the results for operational implementations. The lack of testing over extended periods, in ecosystems characterized by high climatic and topographic variability, limits the possibility of assessing the real reliability of IoT systems in the field.

In addition to the limited duration of experimentation, the predominance of controlled or semi-controlled testing environments constrains the external validity of the reported findings. Forest ecosystems exhibit dynamic interactions between climatic stressors, vegetation structure and terrain complexity, which are rarely captured in short-term experimental designs. As a result, the current evidence provides only a partial understanding of the long-term performance and resilience of IoT-based monitoring systems under real operational conditions.

There is also considerable variability in the types of sensors, hardware platforms, communication protocols and performance indicators used. This lack of standardization makes it difficult to directly compare results and restricts the development of coherent and widely compatible MRV systems. In addition, many studies report results based on small datasets or simulations, without independent validation in different forest ecosystems.

This technological fragmentation also limits the integration of IoT-generated data into broader monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) frameworks. Without harmonized sensor configurations, data formats and performance indicators, the scalability of IoT solutions beyond isolated case studies remains constrained. Furthermore, the reliance on small datasets, simulations or single-site deployments, often without independent validation, reduces confidence in the transferability of reported results across different forest types and biogeographical regions.

Institutional and operational aspects are addressed unevenly. The real costs of implementation, equipment maintenance, data protection, platform interoperability and integration into existing forest management procedures are rarely analyzed in detail, which limits the assessment of the feasibility of applying IoT at the operational level.

In light of these limitations, future research should move beyond proof-of-concept implementations and focus on the conditions required for operational deployment. Addressing both technological and institutional gaps is essential to support the transition from experimental IoT prototypes to reliable components of forest management systems.

Future research should prioritize long-term and multi-site deployments of IoT systems across heterogeneous forest ecosystems. Extended monitoring periods are necessary to evaluate system robustness, sensor performance degradation, energy efficiency and communication reliability under real environmental stressors. Such approaches would allow for a more realistic assessment of the sustainability and resilience of IoT infrastructures in forestry applications.

Strengthening the institutional framework and building digital skills are essential for moving from prototypes to stable implementations, aligned with the objectives of Forest 5.0.

From a technological perspective, further advances are required in edge and distributed data processing architectures to reduce energy consumption and communication loads while maintaining data quality. The integration of IoT data with UAV- and satellite-based Earth observation products represents a critical pathway toward multiscale forest monitoring. In this context, the operationalization of Digital Twins for forest ecosystems offers significant potential for continuous monitoring, scenario analysis and adaptive management.

Beyond technical innovation, strengthening institutional frameworks and digital competencies remains a key prerequisite for successful implementation. Capacity building within forest administrations, along with improved governance, interoperability and alignment with policy frameworks such as Forest 5.0, will be essential to ensure that forestry digitalization evolves from isolated pilot projects toward stable, scalable and sustainable smart forestry systems.

Consequently, to fully harness the potential of IoT in forestry, an integrated approach is needed that combines technological innovation with standardization, long-term testing and institutional capacity building, so that forestry digitalization becomes sustainable.

5. Conclusions

This review analyzed the recent literature on the use of IoT technologies in smart forestry, highlighting the contributions and limitations reported between 2020 and 2025. The results obtained to date show consistent progress in fire detection, carbon monitoring and storage, digitalization of forestry processes and the development of the institutional framework necessary for the adoption of these technologies.

In terms of fire detection, IoT systems integrated with machine learning models offer high accuracy and reduced response time in experiments and local validations. However, the persistence of constraints related to energy autonomy, interference and field coverage indicate that the operational implementation requires further optimizations.

For carbon monitoring, the reviewed studies confirm that integrating sensory data with remote sensing and ecosystem models allows for consistent estimates of carbon stocks and flows. Variability in stand structure and the impact of natural disturbances significantly influence the results, which underlines the importance of spatially calibrated and repeatedly validated MRV systems.

The analysis of the Forest 4.0/5.0 direction shows a clear trend towards the use of cyber-physical architectures, Digital Twins and explainable artificial intelligence. Although the potential of these tools is well-defined, most applications are still in the experimental stage, with relatively few studies documenting operational implementations in the field.

The institutional and policy dimension indicates that the adoption of IoT technology depends on standardization, interoperability and the ability of organizations to integrate digital technologies into management processes. The European framework provides clear directions, but their application in practice is under consolidation.

Across the reviewed literature, several recurring research directions can be identified. These include the integration of IoT with AI-based analytics for early detection and prediction tasks, the combination of IoT and remote sensing data for multiscale monitoring, the emergence of Digital Twin concepts within Forest 4.0 and 5.0 frameworks and the increasing attention to governance, interoperability and data standardization challenges. These elements outline the current research status and represent the main hotspots shaping ongoing developments in smart forestry.

Overall, IoT is a useful tool for monitoring forest ecosystems and supporting climate-smart management. Progress is evident, but long-term validation, protocol harmonization, improved system autonomy and expanded testing under real-world operating conditions remain necessary. The development of a robust digital infrastructure, specific to Forest 5.0, depends not only on technological advances, but also on the capacity of institutions to integrate these solutions into current forestry practices, optimizing forest management, forest resource protection and ecosystem service evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D.A. and F.H.A.; methodology, I.D.A. and I.M.M.; software, I.A.C. and V.I.I.; validation, I.D.A., I.M.M. and A.M.T.; formal analysis, I.D.A. and A.M.T.; investigation, I.D.A., I.M.M. and A.M.T.; resources, F.H.A. and I.A.C.; data curation, I.D.A. and V.I.I.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.A.; writing—review and editing, I.D.A., I.M.M. and F.H.A.; visualization, V.I.I.; supervision, F.H.A.; project administration, I.D.A.; funding acquisition, F.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted within the project “Intelligent Monitoring of Forest Ecosystems Using IoT Technologies: An Innovative Approach to Combat Climate Change and Protect Biodiversity”, funded under the TEAMS/Young Scientists program of the Romanian Academy of Sciences (AOȘR), selected in 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the institutional support provided by the Academy of Romanian Scientists (AOȘR) within the Project for Young Researchers/Project TEAMS “Intelligent Monitoring of Forest Ecosystems Using IoT Technologies: An Innovative Approach to Combat Climate Change and Protect Biodiversity”, which facilitated the development of this study. The authors also thank the administrative and technical staff of the Faculty of Forestry and Cadastre, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, for their assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1, 2025) for language refinement, organization of ideas, and technical editing. The authors have reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AGB | Above-Ground Biomass |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ALS | Airborne Laser Scanning |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

| AOȘR | Academia Oamenilor de Știință din România |

| ARIMA | AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average |

| BME280 | Environmental Sensor Module (Bosch) |

| CASA | Carnegie–Ames–Stanford Approach model |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CSC | Carbon Sequestration Change (flux anual de carbon) |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide (din MQ-6) |

| DHT11/DHT22 | Digital Temperature and Humidity Sensors |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| ESP32 | Low-Power Microcontroller with Wi-Fi/Bluetooth |

| FIA | Forest Inventory and Analysis (USDA) |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| InSAR | Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| IoFT | Internet of Forest Things |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| LoRa | Long-Range Radio |

| LoRaWAN | Long-Range Wide-Area Network |

| LPWAN | Low-Power Wide-Area Network |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| MRV | Monitoring, Reporting and Verification |

| MQ-6 | Gas Sensor Module (LPG/CO detection) |

| NB-IoT | Narrowband Internet of Things |

| NBP | Net Biome Production |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NEP | Net Ecosystem Production |

| PPM | Parts Per Million |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| Sigfox | LPWAN Communication Protocol |

| SN | Springer Nature (din SN Computer Science) |

| TDMA | Time Division Multiple Access |

| TEAMS | Programul AOȘR—Tineri Cercetători |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

Appendix A. Search Strategy, Screening Process and Final Set of Included Studies (2020–2025)

Appendix A.1. Search Strategy and Keywords

Multiple academic databases were queried using combinations of controlled vocabulary and Boolean operators. The following keyword groups were used across databases, capturing variations such as “forest monitoring IoT”, “smart forest”, “digitalization of forests”, “IoT sensors”, “wireless sensor networks”, “forest microclimate” and “remote sensing AI”.

Each database applied automatic pluralization and wildcard expansion (e.g., forest, sensor, IoT).

Appendix A.2. Databases, Dates and Number of Records Identified

| Source | Keywords | n Identified |

| Web of Science | Forest monitoring IoT + smart forest + digitalization of forest | 21 |

| Scopus | IoT for Forest | 39 |

| ScienceDirect | IoT forestry, sensors, CO2, forestry monitoring | 16 |

| IEEE Xplore | IoT, sensor forests, temperature, humidity | 3 |

| MDPI Sensors | Peri-urban forests, carbon sequestration | 3 |

| MDPI Forests | Smart forest, forest digitalization, IoT | 8 |

| IEEE/Elsevier | Smart forest, sensors, IoT | 18 |

| MDPI Sensors/Remote Sensing | Remote sensing, AI, forest microclimate, air quality | 15 |

| SpringerLink | Internet of Things (IoT), wireless | 12 |

| Total | — | 135 |

| Search period: 2020—2025. | ||

Appendix A.3. Screening and Eligibility Process

| Source | Keywords | n Identified | Duplicates Removed | Excluded After Title and Abstract | Excluded After Full Paper | Final Set (Included) |

| Web of Science | Forest monitoring IoT + smart forest + digitalization of forest | 21 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 8 |

| Scopus | IoT for Forest | 39 | 2 | 8 | 22 | 7 |

| ScienceDirect | IoT forestry, sensors, CO2, forestry monitoring | 16 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 2 |

| IEEE Xplore | IoT, sensor forests, temperature, humidity | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| MDPI Sensors | Peri-urban forests, carbon sequestration | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| MDPI Forests | Smart forest, forest digitalization, IoT | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| IEEE/Elsevier | Smart forest, sensors, IoT | 18 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| MDPI Sensors/Remote Sensing | Remote sensing, AI, forest microclimate, air quality | 15 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 0 |

| SpringerLink | Internet of Things (IoT), wireless | 12 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| Total | — | 135 | 8 | 38 | 60 | 29 |

Appendix A.4. List of Included Studies (n = 29)

| Axis | Reference | DOI | Type |

| A | Wesly, J.A. A Detailed Investigation on Forest Monitoring System for Wildfire Using IoT. [39] | https://doi.org/10.3233/ATDE221275 | Experimental |

| A | Üremek, İ.; Leahy, P.; Popovici, E. A System for Efficient Detection of Forest Fires through Low Power Environmental Data Monitoring and AI [11] | https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024068038 | Experimental |

| A | Yerragudipadu, S. An Efficient IoT-Based Novel Approach for Fire Detection [41] | https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/202439201109 | Experimental |

| A | Jayasingh, S.; Swain, S.; Patra, K.; Gountia, D. An Experimental Approach to Detect Forest Fire Using Machine Learning Mathematical Models and IoT [12] | https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-02514-5 | Experimental |

| A | Anthony, B.; A, E.M.; Anthea, L.; Rizki, R.; Achmad, R.; Wangkun, X.; Daphne, T. Assessing the Efficacy of IoT-Based Forest Fire Detection: A Practical Use Case 2024 [32] | https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.09117 | Experimental |

| A | Ayankoso, S.; Wang, Z.; Shi, D.; Yang, W.; Vikiru, A.; Kamau, S.; Muchiri, H.; Gu, F. Development of Long-Range, Low-Powered and Smart IoT Device for Detecting Illegal Logging in Forests [45] | https://doi.org/10.37965/jdmd.2024.550 | Experimental |