Abstract

Considered among the fastest-growing industries in the world, tourism brings immense benefits but also creates certain challenges. Conservation of natural resources is a stringent necessity, without which the extraordinary ecosystems’ attributes that create the premises for nature-based tourism would reduce, alter, and subsequently disappear. The aim of the present review is twofold: gaining a general understanding of what nature-based tourism is and providing a systematic literature review of articles on nature-based tourism in European national and natural parks, with emphasis on their applicability. The articles included in the present review were selected based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The review accounts for research conducted between 2000 and 2021 and is divided into two sections: articles aimed at understanding tourists’ behaviour and articles that are focused on other stakeholders or have the local communities in the foreground. While many studies are aimed at understanding tourists’ behaviour as a means of improving parks’ management, participatory strategies including local communities are often indicated as beneficial. The results of this paper can facilitate future research in the field and provide valuable knowledge to policymakers and any interested parties.

1. Introduction

The challenges that the world is facing nowadays are tremendous, and humanity must continuously find new ways to adapt and improve its practices and way of life as the only means to survive and thrive as a species. Climate change is rapidly taking a toll on nature, biodiversity, and ultimately society. Natural disasters that gravely endanger communities, often coming as an effect of disrupting the natural balance of ecosystems; growing food demand along with fast urbanisation; the need for water and air quality; and addressing and overcoming socio-economic inequality are only a few of the main themes of concern that Europe must face, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [1].

To counteract some of the destructive effects that modern society’s development creates, organisations, institutions, and people all over the world collaborate with the goal of creating a synergy that would decrease the pressure of some of our greatest challenges. The environmental, social, and economic pillars of sustainable development under focus through various proposed measures concern not only the environment and biodiversity but also the economic and social development of communities, as the fragile balance between natural and anthropic dimensions must be carefully maintained [2,3].

Among the measures designed to safeguard the natural ecosystems and ensure a balanced utilisation of resources to the benefit of present and future generations, creating protected areas (PAs) is vital. While the critical need for such areas is conspicuous, they fulfil two main purposes concerning multiple actors in different sectors: conserving biodiversity and ensuring a place for recreational activities.

With the increasing level of urbanisation and the progressively faster and more alert way of living, an increasing number of people are trying to find comfort in unspoiled and raw nature in the search for tranquillity and the pursuit of happiness, well-being, and exciting or unique experiences. Thus, naturally, the demand for recreational opportunities in unaltered environments is increasing exponentially [4]. And what better setting for such a quest than the protected areas that contain, among other things, the precise subject of interest?

Tourism is one of the fastest-growing industries [5,6,7], with a business volume that today is easily comparable with the oil exports, agri-food, or even automotive industries, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Hence, with such growth comes the need for a deeper understanding of one of the leading socio-economic phenomena of the 21st century.

Understanding how nature-based tourism can be placed in connection with other forms of tourism and how it is situated relative to the industry in general helps in identifying the right approach and strategies for the sustainable development of this activity.

As illustrated by Cater et al. [8] and Metin [9] in their works, one potential approach for positioning nature-based tourism in comparison with some of its related forms of tourism is to understand how it overlaps with already established concepts, such as ecotourism, wild-life tourism, and sustainable tourism, all placed under the same umbrella—using natural areas as the main stage for touristic activities.

With the global strive for action aimed at sustainable development and the 17 Goals [10] adopted by all United Nations Member States as a shared canvas model, a great opportunity and necessity arise for studying and shaping new practices focused on nature-based tourism.

The aim of the present review is twofold: gaining a general understanding of what nature-based tourism is and providing a systematic literature review of articles on nature-based tourism in European national and natural parks, with emphasis on their applicability. The synthesis of the existing state of knowledge was performed in two main categories: (1) articles aimed at understanding tourists’ behaviour; and (2) articles that are focused on other stakeholders or have the local communities in the foreground.

The existing gap in the specialised literature is vast, with currently no similar review, and the need for a thorough recognition of the main stakeholders involved determined the current direction of study. This approach provides a first insight into the studied subject and helps in understanding how, through research, valuable knowledge can be revealed and further used by policymakers, service providers, local communities, and future specialists in the studied field.

2. Nature-Based Tourism: Concept and Forms

2.1. The Concept of Nature-Based Tourism

Nature-based tourism could be generally seen as touristic activities that take place in a natural environment. While the previous statement remains valid, some authors bring into perspective the importance of the natural setting, placing it as a key factor rather than ancillary [11]. At the same time, nature-based tourism is determined and modelled by both anthropic and natural factors such as socio-demographic attributes (of both consumers and residents), cultural values and financial aspects, biotic and abiotic elements (unique fauna, flora, often spectacular geology and hydrography of an area, etc.), infrastructure (access, utilities, and services), as well as objectives (endemic species, pristine wilderness, serene landscapes, monuments of nature, and man-made elements of touristic attraction within a natural setting).

Different actors have different perspectives and impose a specific approach regarding the concept of nature-based tourism. While tourists are interested in the benefits obtained through a nature-based experience (improved health and well-being, positive memories and social interactions, exciting experiences, social status, etc.) [9,12,13], service providers are interested in the financial benefits that can be obtained by quantifying and embodying nature elements into profitable products [14]. Therefore, it could be stated that nature oversteps the role of a setting for touristic experiences and becomes the actual product.

Although it may not seem hard to gain a general idea of what nature-based tourism could refer to, a consensus when defining this specific type of tourism has not yet been achieved. There appears to be an increasing interest in the subject in the last 15 years, with various articles focusing exclusively on nature-based tourism or analysing it as part of broader tourism studies. While understanding and defining the concept is one objective, correlation with general sustainable development is often being made in the search for better and more efficient solutions for managing and increasing the attractivity of protected areas and communities residing within them.

Several review articles [9,13,15,16] investigate the concept of nature-based tourism, trying to gain a deeper understanding and shed some light on the theoretical aspects that surround this form of tourism (existing definitions, epistemology, and how to measure and analyse it), but the research gap is yet to be diminished. The scientific literature is rather focused on trying to identify, understand, and improve various concrete issues, often through specific study cases. Therefore, the concept of nature-based tourism is not always the focus. This generates a paucity of publications in the research literature that aim to create the premises for a common definition that would be generally and officially accepted.

Trying to define nature-based tourism has implications not only for the research environment but also for society at large. Finding accurate and reliable ways to measure demand (e.g., perception, motivations, preferences, attitudes, behaviour, and expenditure) and supply (e.g., offers, natural resource valuation, generated income, and the labour market) can enable scholars in their studies. Where locals, different stakeholders, and suppliers need to cooperate to meet different needs and goals (biodiversity and conservation, preserving cultural heritage, sustainable development, improving the living standard of communities, achieving economic growth, and financial gains for both private and public institutions involved), a commonly accepted definition of nature-based tourism can help in achieving the best results.

Although the UNWTO has set a defining frame for what a visitor is—a person travelling “outside his/her usual environment, for less than a year, for any main purpose […] other than to be employed by a resident entity in the country or place visited” [17] (p. 10), whether domestic, inbound or outbound, classified as a tourist (overnight visitor), or as an excursionist (same-day visitor)—even in this situation, there can be ambiguity when it comes to what every country understands by “usual environment” of a person. Subsequently, when trying to measure aspects related to nature-based tourism specifically, equivocation raises difficulties in understanding and delimiting the concept and nature-based tourism practitioners.

While no universal definition has been formulated, the literature pushes the often-mentioned nature-based tourism as an umbrella term under which different forms of tourism can be included.

As mentioned before, nature can play different roles in tourism, and Valentine [11] points out three main levels of implication: certain types of touristic experiences are fully dependent on nature (e.g., observing wildlife in the wilderness, such as bird-watching), some activities are only enhanced by the natural setting (e.g., camping), while others can be achieved with similar levels of satisfaction even in the absence of nature (e.g., satisfying the need to cool off by taking a swim). After identifying multiple definitions in the existing literature, Valentine [11] (p. 108) proposes a simplified version: “nature-based tourism is primarily concerned with the direct enjoyment of some relatively undisturbed phenomenon of nature”.

More recently, Fredman and Tyrväinen [14] state: “the nature-based tourism industry represents those activities in different sectors directed to meet the demand of nature tourists”.

In a 2019 study, nature-based tourism is defined as “visitation to a natural destination which may be the venue for recreational activity […] where interaction with the plants and animals is incidental, or the object of the visit to gain an understanding of the natural history of the destination […] and to interact with the plants and animals”, where “the interactions […] can be non-consumptive or consumptive” [18].

Also in 2019, Fossgard and Fredman [19] stated a direct link between nature-based tourism and adventure tourism and chose to base their study on a minimalistic definition of nature-based tourism from a previous study, without any mentions of the type of touristic activity that is to be practised, the risks or requirements, or the environment and satisfaction expected.

In 2020, the World Bank Group [20] reported the definition given by Leung et al. [21] (p. 99) for nature-based tourism: “forms of tourism that use natural resources in a wild or undeveloped form. Nature-based tourism is travel for the purpose of enjoying undeveloped natural areas or wildlife”.

Thus, a very broad spectrum can be comprehended without imposing any clear limitations on the definition of “human activities”, “natural areas”, or “usual surroundings”.

Without a clear definition regarding the conservation of nature—a constant goal of nature tourists and stakeholders alike—transportation, accommodation, and certain activities could be excluded unless closely linked to nature, including swimming pools, golf courses, and downhill ski slopes (which may not meet the criteria of what is generally viewed as nature-based tourism [22]).

Recurring themes in many studies correlate nature-based tourism with tourists travelling into a nature area to experience the natural environment, involving a nature-related activity, and considering sustainability principles in the process.

2.2. Forms of Nature-Based Tourism

While found in the literature under different terms—“nature based tourism”, “nature-based tourism”, “nature tourism”, “nature travel”, “natural area tourism”, “nature-orientated tourism”, “ethical tourism”, “responsible tourism”, “environmental-friendly travel”, “environmental tourism”, “green tourism”, “sustainable tourism”, and “conservation tourism”—nature-based tourism is widely considered to coincide with multiple forms of tourism and touristic activities. This guided the approach of the present review in addressing the concept of nature-based tourism.

Among the commonly recognised forms of nature-based tourism are the following:

- -

- Ecotourism/Eco-tourism/Ecological tourism—While one of the most popular and widely studied forms of tourism of the century, there is still a wide plethora of definitions to describe it. For example, Fredman and Tyrväinen [14] identified 42 recognised definitions mentioned in one paper alone.

According to the International Ecotourism Society, ecotourism is defined as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education” [23]. UNWTO describes it as “all nature-based forms of tourism in which the main motivation of the tourists is the observation and appreciation of nature as well as the traditional cultures prevailing in natural areas” [24].

- -

- Wildlife tourism is a form of nature-based tourism “that includes, as a principle aim, the consumptive and non-consumptive use of wild animals in natural areas”. [25] (p. 3).

- -

- Geotourism is an abiotic nature-based tourism that, according to some definitions, is “a form of natural area tourism that specifically focuses on geology and landscape. It promotes tourism to geosites and the conservation of geodiversity and an understanding of earth sciences through appreciation and learning”. [26].

- -

- Rural tourism is ”a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s experience is related to a wide range of products generally linked to nature-based activities, agriculture, rural lifestyle/culture, angling and sightseeing”, according to UNWTO [27].

Other mentions include adventure tourism (hard and soft; not always taking place in the wilderness), mountain tourism, outdoor tourism/outdoor recreation, active tourism, wilderness tourism, dark sky tourism, and botanical and garden tourism.

Some usual nature-based activities are hiking, trekking, birdwatching, photography, camping, hunting, fishing, park touring, skiing, mountain biking, safaris, stargazing, etc.

When it comes to the tourism industry, efficient collaboration and understanding between all actors involved are vital to achieving positive effects and the highest results [28]. The administration, groups with scientific expertise, local communities, and companies offering touristic services and products, along with their consumers, are all equally important and should be included in the decision-making process. If one of the aforementioned groups is not acknowledged in the creation of administrative frameworks and development processes, maximising the best outcome will be impossible, leaving room for the possibility of creating negative effects along the way.

The correlation between research in the field with various scientific results and the actual implementation of tangible actions is scarce and needs to be addressed. This is where organisations such as IUCN come in cooperation with governments and local authorities in the struggle to apply practical solutions: “In Europe, the IUCN European Regional Office works closely with EU institutions, EU member states and other key stakeholders to ensure that the concept of nature-based solutions is well-known, accepted, and reflected in policies across different sectors and levels of government”. [29].

Other notable mentions of institutions, organisations, and projects that contribute to and influence directly or incidentally the nature-based tourism industry are the Federation of Nature and National Parks of Europe (EUROPARC Federation)—the largest network of European Protected Areas, the European Environment Agency, the European Greendeal, the BIOTOUR research project, Horizon2020 (e.g., “Enabling Low carbon, clean access to National Parks”), Natura2000, and the European Commission’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

3. Methodology

While narrative reviews can be very comprehensive on a given subject, the limitations and lower efficiency in presenting the findings [30] led to the use of the systematic literature review model. Systematic literature reviews have several important qualities that influenced the decision to conduct the present research accordingly, such as a clearly defined methodology, a comprehensive and structured collection of research articles, and the opportunity to pursue related studies [30]. Hence, the present review is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement revised in 2020 [31], with its 27-item checklist and recommendations to support a thorough review.

The search for the present review was conducted from February–April 2022, using Clarivate Analytics’ online database, Web of Science™ (WoS).

Within the identification process, only articles, proceeding papers, and early access papers written in English between 2000 and 2021 with the main interest of obtaining an overview of the subject reflecting the 21st century were included.

Based on the purpose of this research and the foray into understanding the defining elements of tourism outlined above, the main labels associated with nature-based tourism were selected, and the Boolean operators AND/OR and “*” were used to avoid unintended exclusions based on terminology.

The final syntax used for this study is the following:

“Nature-based touris*” OR “Nature Touris*” OR “Nature * tourism” OR “Nature based activ*” OR “recreat * activ*” OR “Ecotouris*” OR “Eco-touris*” OR “Adventure Touris*” OR “Wildlife Touris*” OR “Wilderness Touris*” OR “Mountain Touris*” OR “Outdoor Recreation” OR “Outdoor Touris*” OR “Rural Touris *” (TOPIC) AND “National Park*” OR “Natural Park*” (TOPIC) NOT “Marine” (TOPIC) NOT “Coastal” (TOPIC).

During the selection process, all results were scanned and assessed against the chosen criteria to determine the best selection relevant to the present study. The screening process consisted of analysing the search results by title content, abstract, and keywords and, based on certain criteria, eliminating the articles that were not of interest for further consideration.

This process was followed by an in-depth assessment of eligibility based on the full text of articles that passed the screening procedure.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles, proceeding papers, or early access papers written in English and published between 2000 and 2021; (2) research papers focused on various forms of nature-based tourism concepts, practices, effects, and perspectives; (3) case studies addressing tourists’ preferences and behaviour, locals’ perceptions and attitudes, as well as papers dealing with managers’ and policymakers’ points of view.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) review papers (traditional, systematic, mixed); (2) conceptual frameworks without applied methods; (3) study cases outside Europe; (4) articles that are not mainly related to national or natural parks; (5) articles that were not relevant to the goal or the research (e.g., focused on the touristic potential of a certain area, biodiversity); (6) articles that were accepted during the screening process but were not accessible in full-text version.

The information retrieved included the author’s name, the title and year of publication, keywords, journal of publication, WoS category, citation number, country/countries of study, research methods applied (qualitative/quantitative/mixed), main objectives of the research, applicability of the results, and funding of the study. These elements help identify the most common research directions concerning European national and natural parks.

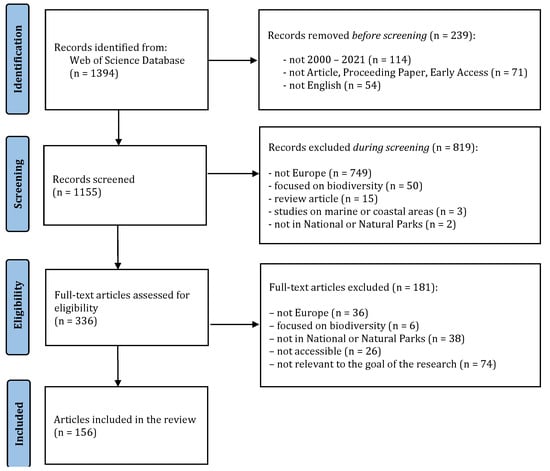

The flow process of the systematic review is depicted in Figure 1. Based on the designed syntax, 1394 results were returned before applying three conditions: only papers published between 2000 and 2021; only articles, proceeding papers, and early access papers; and only studies written in English, leaving a total of 1155 papers to undergo the next phase of the selection. Following the screening process, all remaining results were analysed by title, abstract, and keywords for testing against the exclusion criteria established at the beginning of the research. Based on the findings, 819 papers were excluded, of which 749 studies were conducted in countries outside Europe, 50 articles addressed biodiversity aspects as their main point of interest, 15 papers were review articles, 3 studies were conducted on marine or coastal areas, and 2 studies were not conducted in a national or natural park. The screening phase was passed by 336 articles, which were further assessed for eligibility by full-text analysis. In some articles, it was not clear from the abstract that the studies were not conducted in Europe or national or natural parks, and this was only discovered during the second phase. In this final stage of selection, 181 articles were excluded: 36 studies were conducted outside Europe; 6 papers were focused on biodiversity; 38 studies were not in national or natural parks; 26 articles were not accessible; and 74 were not relevant to the goal of the research. After evaluating the eligibility, a total of 156 articles were accepted and included in the present review: 66.67% addressed tourists’ perceptions, attitudes, behaviours, and motivations; 33.33% were focused on different stakeholders (the local community, park management, policymakers, service providers, etc.).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for research articles included in the present review based on PRISMA.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Research Papers Focusing on Tourists

In the following paragraphs, the 104 research papers focusing on tourists (Table 1) are accounted for and analysed. The information gathered refers to the methodology and instruments used for collecting and analysing data, the main objectives of the articles, the applicability of the results, and whether the studies have been funded by institutions or organisations.

Table 1.

Research papers included in the review that focus on tourists.

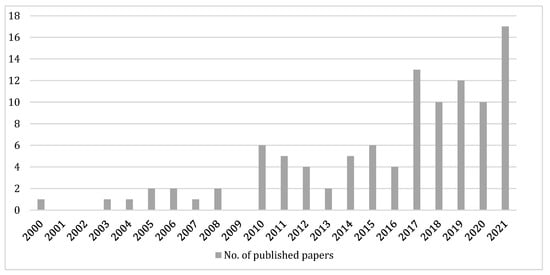

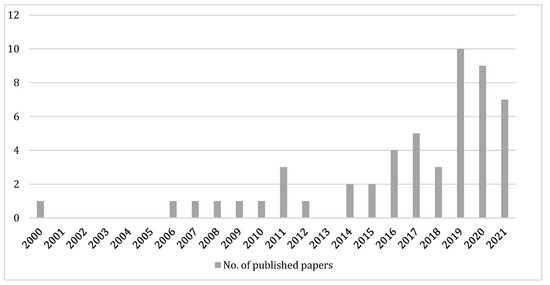

Figure 2 illustrates the number of published papers per year between 2000 and 2021 and indicates a clear growing interest in the subject in the past decade.

Figure 2.

Published papers between 2000 and 2021 focusing on tourists. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by WoS.

The predefined Web of Science category with the highest number of articles focusing on tourists registered within the present study is “Hospitality, Leisure, Sport, and Tourism” (34%), followed closely by research areas focused on environment studies, as shown in Table 2. Out of the 104 articles included in the analysis, 55 were identified within two or more WoS categories.

Table 2.

Top 10 WoS categories by the number of identified articles focusing on tourists.

While a very large number of different publication journals were identified (64 journal titles), the top three with the most publication articles analysed in the present review that focus on tourists’ behaviours and demands are: Sustainability (7%), Land (7%), and Eco Mont-Journal on Protected Mountain Areas Research (6%).

The 12 journals presented in Table 3 account for 51% of all articles focusing on tourists included in the review. The impact factor, the number of citations, the H-index, and the quartile that the journal or distinct categories of a journal belong to are accurate indicators for a publication, and when analysed together, they can provide a general overview of the academic quality of the content. As shown in Table 3, ten out of the twelve most encountered publications for the present research belong to Q1 or Q2, which raises confidence in the scientific standard and interest in the analysed subject.

Table 3.

Top 12 journals with the highest number of published studies focusing on tourists.

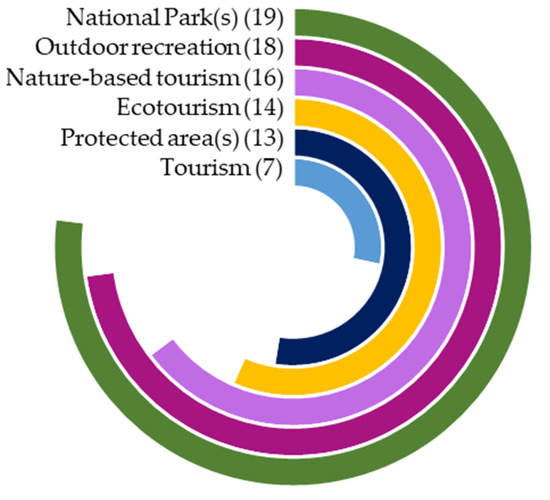

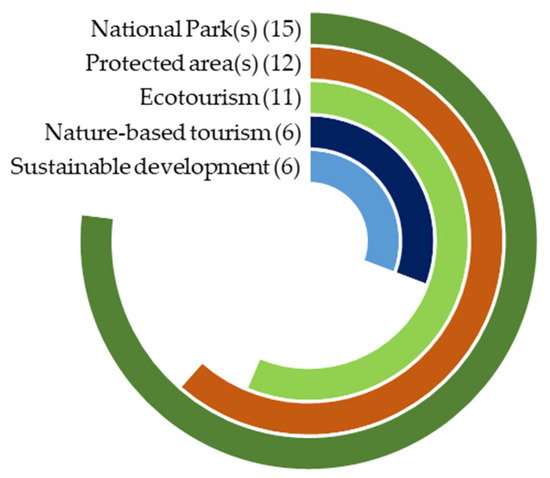

A visual accounting of author keywords, as provided by WoS, with a frequency higher than 5 can be seen in Figure 3. It was determined that most appearances are for “National Park” and “National Parks” together—5% of all keywords. Representing a main point of interest in the research papers, they were used 19 times out of a total of 382 different items. The keywords “Ecotourism” and “Eco-tourism” were also considered summed entries.

Figure 3.

Keywords with the highest frequency in articles focused on tourists. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by WoS.

The analysis of citations places the articles titled “Willingness to pay entrance fees to natural attractions: An Icelandic case study” [126] (120 citations), “Visitors’ satisfaction, perceptions and gap analysis: The case of Dadia-Lefkimi-Souflion National Park” [123] (82 citations), and “Past on-site experience, crowding perceptions, and use displacement of visitor groups to a peri-urban National Park” [128] (74 citations) as the most influential papers with the highest contribution to the research in the field. The results are illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Top 10 most cited published articles focusing on tourists according to the WoS number of citations.

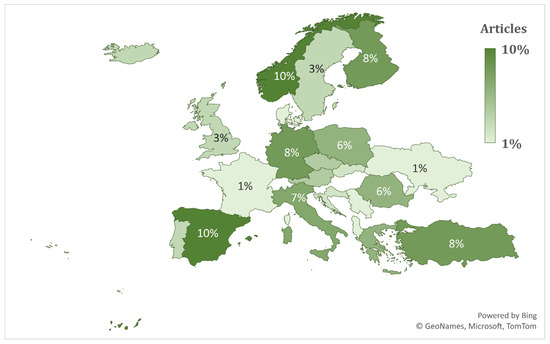

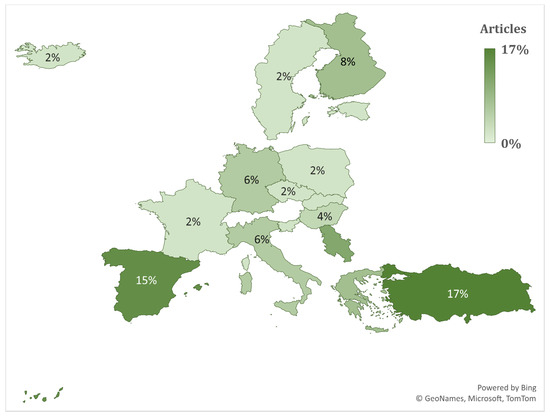

Accounting for the number of articles published by the country where the study was conducted (Figure 4), Spain (10%), Norway (10%), Finland (8%), Turkey (8%), Germany (8%), and Italy (7%) present the highest interest for studying tourists’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours related to nature-based tourism in national and natural parks.

Figure 4.

Percentage of articles by country in Europe focusing on tourists as reviewed in this research. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by WoS.

Another indicator that helps emphasise the necessity and importance of research aimed at understanding tourist demand with all its attributes is the funding of studies. Within the 104 reviewed papers, 53% were financed by various institutions, showing that scientific knowledge on the subject is requested and can provide valuable insights with diverse implications and plausible applicability. This includes insights for the management and administrative units of protected areas, for governmental institutions and policymakers, for local communities and residents directly affected by the tourism industry and the designation of PAs, for service providers that continuously need to adapt and expand their offer to meet tourists’ needs and tendencies, and for the academic world that is endeavouring to expand the knowledge and understanding of different aspects of tourism and create the premises for better practice.

Among the methods of data analysis identified, 71% of the studies were based on quantitative methods, 7% on qualitative methods, and 22% on mixed methodologies, using various techniques. The data collection instrument most used was a questionnaire (76%), but interviews, observation, and focus groups were also used as traditional tools for research. In the struggle to improve the research process, authors are striving to validate new methods, mainly to ease the process and reduce or overcome the limitations of traditional instruments (time-consuming, expensive, incomplete information, human error). Some authors choose to analyse information already available on social media platforms to understand consumer behaviour [32,49,53,71], while others take a different approach, analysing GPS/PPGIS tracks to study travel patterns [55,63,65,73,80,82,90,92,94,104], and a few authors, such as Barros et al. [58], use both methods.

Based on the main objectives identified across the reviewed studies, the recurring themes coincide with the main nature-based tourism topics stated by the World Bank Group: enabling policy environment, governance and institutional arrangements, concessioning and partnership models, destination management, infrastructure and facilities, visitor management, nature-based enterprise development, impacts of nature-based tourism, risk management and climate change, and monitoring and evaluation [20].

In general, the articles presented in this section (Table 1) provide valuable insight into the understanding of tourists’ preferences, attitudes, or behaviours through various methods and techniques. Their applicability was found by exploring their particular methodology and examining the aim, objectives, and potential practical use of the findings. A few articles that have potential management implications for the sustainable development of parks and other protected areas focused on understanding tourists’ willingness to pay for visitation fees [126,131,133]. Some authors attempted to develop guidelines for sustainable tourism planning [34,38]. As discussed earlier in the present review, nature can be viewed not only as the context for touristic activities but as a product itself. Visiting a national park can be seen as having its value and benefits without the consumption of other services or as a complete package where anthropic elements are complementary. Carvache-Franco et al. [35] and Carrascosa-López et al. [38] analysed the correlation between the perceived value of a touristic destination and the loyalty of tourists, or their desire to return. Monitoring visitors is also a subject of potential interest to park managers, and it is addressed by analysing various methods: camera traps [39], applications [64], and GPS tracking [73]. Kristensen et al. [42] analysed tourists’ motivations based on their level of experience, information that can be used for potential campsite development. Pouwels et al. [55] tackled an important aspect of protected areas, trying to estimate the effect of management actions on visitor densities. Developing new facilities in national parks, such as information stands, is a decision that impacts visitors’ experiences. Their most suitable location can be determined by analysing visitor behaviour using geotagged data from social media, as proposed by Barros et al. [58]. Overcrowding in national and natural parks is another subject of potential interest to park management. Several authors addressed this by predicting congestion levels [60] or identifying tourists’ profiles [68] and their perceptions of the crowding levels [109,121,128]. Natural and national parks have hotspots or popular places that attract a wide variety of tourists and can even be part of an inhabited area. It can be of interest to the park management to identify highly valued visitation areas to minimise potential conflicts [66]. Other articles attempted to evaluate hiking trails [63,78,104,132].

Another side of the potential implications of the reviewed articles for the management of parks is that of nature conservation. To successfully balance nature conservation and tourism, it can be of interest to determine the perceived value of the human–nature relationship, as Fälton aimed to do in his paper [32]. Understanding tourists’ willingness to pay for conservation [84] and their behaviour concerning wildlife [43] can support park management in their decision-making. Assessing the suitability of the infrastructure for recreational activities in parks is another important aspect addressed by Turgut et al. [47] and Taczanowska et al. [82]. Dell’Eva et al. [52] tried to assess the perceived role of wildlife in creating a satisfactory touristic experience. When actors have different interests, financial gain can be achieved through methods that can cause harm to unaltered environments. Comparing the revenues of wildlife tourism activities with other resource exploitation could potentially justify the sustainable development of parks [61]. Although tourism activities can bring numerous advantages to an area, it is important not to overlook the negative impacts of tourism and try to evaluate them to improve the development measures of parks [94].

Some articles in the present review may have extensive research implications for understanding tourists’ attitudes and behaviours towards nature [33] or for innovation. Mancini et al. [71] validated the use of Flickr data as a research method. Moreno-Llorca et al. [67] developed a method to assess tourists’ perceptions of recreational activities, and Sinclair et al. [49] compared two research methods for the evaluation of perceived value to facilitate future research.

Service providers can gain valuable information from research in the field and improve their offer in accordance with demand and market conditions. Understanding tourists’ expectations and level of experience can be used to develop tourism services [40]. It can be of interest to understand the role of professional guides in parks [102] and tourists’ decision-making processes to justify the need for this service [36]. Carrascosa-López et al. [38] created guidelines to develop products based on tourists’ perceived value of them and predicted behaviour. Another practical aspect is analysing the effects of park attributes on the prices of services [45]. Other authors tried to analyse tourists’ interests in “eco-sustainable goods and services” [65,85].

Although not focused solely on the local communities, some of the articles included in this section have potential implications for them. To achieve an integrated approach to park resources, Cozma et al. [44] analysed the impact of tourism on communities surrounding the parks. Çetinkaya et al. [76] tried to understand the potential difficulties of local people using park areas as tourists.

Some articles have been found to have potential implications for other institutions and for developing governance, fiscal policies, and marketing strategies for tourism. For example, Melnychenko et al. [46] measured the brand positioning of parks, and Molina [62] developed a tool that helps evaluate investments in fire protection in parks.

4.2. Description of Research Papers Focusing on Local Communities and Other Stakeholders

Similar to the previous section of this paper, a general review of the 52 selected articles can be seen in Table 5.

As mentioned earlier, synergy between all parties involved in the existence and governance of protected areas is vital for achieving efficient management, sustainable development, and peaceful coexistence [136,137]. While various stakeholders can be identified concerning nature-based tourism in national and natural parks, it is important to note that the local communities play a vital role and require careful consideration. Throughout the 52 reviewed papers included in this section of the present study, 42% are solely or partially focused on the people residing on the territory or in the immediate vicinity of the protected areas being addressed. Other stakeholders that are the subject of the research include national and natural park managers, local authorities, private providers of touristic services, and business owners, as well as mass media operators that can influence public opinion and lobby on the matter.

Figure 5 illustrates the fluctuation in articles published between 2000 and 2021 and focused on different categories concerned directly or tangentially with the development and management of nature-based tourism in national and natural parks. Comparing different time frames, a slightly growing interest can be concluded.

Figure 5.

Published papers between 2000 and 2021 focusing on other stakeholders. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by WoS.

Table 5.

Research papers included in the review that focus on various stakeholders.

Table 5.

Research papers included in the review that focus on various stakeholders.

| Nr. Crt. | Year and Reference | Country | Method | Main Instrument of Data Collection | Objectives * | Applicability | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2020 * [138] | Finland | Qualitative | Thematic interview (n = 10 respondents) | Analyse the balance between tourism and nature conservation from a historical perspective | Management implications—improving the sustainable management of NPs | No |

| 2 | 2021 [139] | Hungary | Mixed | In-depth interview (n = 76 respondents) | Analyse the balance between tourism and nature conservation in NPs | Management implications—improving cross-sector collaboration for managing and developing NPs | No |

| 3 | 2021 [140] | Germany | Quantitative | Interview; secondary data | Estimate visitation data using a standardised methodology | Management implications—improving the sustainable management of PAs, with consideration for the carrying capacity | Yes |

| 4 | 2021 [141] | Serbia | Mixed | Interview (n = 4) | Present the methodology for NP management decision-making | Management implications—improving decision-making processes in NP administration | Yes |

| 5 | 2021 [142] | Serbia | Mixed | Survey | Prioritise management strategies for NP administration | Management implications—improving decision-making processes for the development of NPs | No |

| 6 | 2021 [143] | Russia | Mixed | Survey; secondary data | Determine the economic value of PAs—case study on an NP | Management implications—balancing between the maximisation of the ecological and economic value of PAs | No |

| 7 | 2021 [144] | Hungary | Mixed | Questionnaire (n = 146 respondents); semi-structured interview (n = 36 respondents); roundtable discussion (n = 40 respondents); focus group (n = 15 respondents); desktop study | Analyse the results of adaptive co-management | Management implications—stimulating adaptive co-management of PAs | Yes |

| 8 | 2021 [145] | Turkey | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 366 respondents) | Analyse the involvement of local women in ecotourism activities—case study on an NP | Management/local community implications—understanding the role of women in the development of ecotourism for improving local people’s quality of life and the protection of NPs | No |

| 9 | 2020 [146] | Spain | Mixed | Questionnaire (n = 363 respondents); interview (n = 95 respondents) | Analyse the effects of conservation and rural development policies on the offer of touristic services—case study on an NP | Management implications—improving environmental policies considering the benefit of local communities | Yes |

| 10 | 2020 [147] | Italy | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 78 respondents) | Analyse the effects of ecotourism implementation—case study on an NP | Service provider implications—improving awareness of conservation issues and adapting economic practices accordingly | Yes |

| 11 | 2020 [148] | France | Qualitative | Interview (n = 45 respondents); participant observation; logbooks; secondary data | Analyse cross-sector contributions to sustainable mountain tourism development | Management/service provider/local community implications—improving the sustainable management of NPs | No |

| 12 | 2020 [149] | Poland | Quantitative | Quantifying the volume of waste per tourist | Analyse the amount of waste on tourist trails in a popular PA | Management implications—improving the sustainable management of PAs | No |

| 13 | 2020 [150] | Poland-Slovakia-Ukraine | Quantitative | Questionnaire (for demographic data and tax revenues); secondary data | Analyse the development of ecotourism in relation to the demography, land use, and revenue of local stakeholders | Institution/service provider/local community implications—improving the development of ecotourism | Yes |

| 14 | 2020 [151] | Italy | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 62 respondents) | Analyse the local people’s attitude towards sustainable ecotourism development in PAs | Management/service provider/local community implications—developing eco-sustainable goods and services through ecotourism | No |

| 15 | 2020 [152] | Spain | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 75 respondents) | Analyse local people’s perceptions of the sustainability of tourism and the public exploitation of NPs | Management/institution/service provider/local community implications—improving coordination in the usage of resources in PAs | Yes |

| 16 | 2020 [153] | Serbia | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 115 respondents) | Determine the tourism potential, the degree of utilisation of PA resources, and the level of awareness of the local population on this matter | Service provider/local community implications—improving the tourism offer in PAs | No |

| 17 | 2019 [154] | Spain | Mixed | Semi-structured interview (n = 3 respondents); secondary data (e.g., census on local people) | Demonstrate the sustainability of the coexistence of a sports tourism event and a historical and cultural one | Management implications—improving the sustainable management of NPs | Yes |

| 18 | 2019 [155] | Italy | Mixed | Interview (n = 17 respondents) | Analyse stakeholders’ points of view on tourism development | Management/service provider implications—developing integrated tourism offers in PAs | Yes |

| 19 | 2019 [156] | Finland | Mixed | Semi-structured interview (n = 11 respondents); visitor survey (n = 756 respondents); PPGIS survey (n = 170 respondents) | Analyse the potential of PPGIS use for visitor use planning—case study on an NP | Management/research implications—integrating PPGIS tools into planning processes and management of NPs | No |

| 20 | 2019 [157] | Iceland | Qualitative | Workshop (n = 14 respondents in 3 groups) | Analyse the use of participatory scenario planning for adaptation planning in glacial mountain tourism | Management implications—reducing uncertainty for long-term planning and decision-making in PAs | Yes |

| 21 | 2019 [158] | Germany | Mixed | Questionnaire (n = 12 respondents); semi-structured interview (n = 16 respondents) | Analyse the balance between tourism and nature conservation in the context of public participation—case study on an NP | Management implications—balancing between increasing tourism demand and biodiversity conservation | Yes |

| 22 | 2019 [159] | Poland, Slovakia | Qualitative | Interview (n1 = 14 Polish respondents, n2 = 8 Slovak respondents) | Analyse NP authorities’ attitude towards the organisation of mass sports events in PAs—case study on an NP | Management/service provider implications—developing and managing sports events in NPs | No |

| 23 | 2019 [160] | Spain | Quantitative | Interview (n = 15 respondents) | Propose PA categories corresponding to the IUCN framework based on a participatory approach | Management implications—improving the management of PAs | Yes |

| 24 | 2019 [161] | Turkey | Mixed | Interview | Analyse touristic value by highlighting cultural, historical, and natural viewpoints—case study on an NP | Management/research implications—applying visibility analysis and landscape assessment for NP tourism management | Yes |

| 25 | 2019 [162] | Serbia | Mixed | Questionnaire (n = 112 respondents) | Analyse the local population’s opinion on the sustainability of tourism development and its contribution to rural development in PAs | Management/local community implications—improving sustainable development strategies for tourism in PAs | Yes |

| 26 | 2019 [163] | Spain | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 384 respondents); interview | Analyse the social demand for sustainable management of a PA | Management/local community implications—estimating the optimal distribution of the annual budget of PAs according to social demand | Yes |

| 27 | 2018 [164] | Spain | Mixed | In-depth, semi-structured interview (n = 7 respondents); focus group (n = 13 respondents in 3 groups); secondary data | Analyse the conflict between tourism, nature conservation, and local economic development in NPs | Management implications—improving tourism management in PAs in the context of conflicting interests | Yes |

| 28 | 2018 [165] | Serbia | Mixed | Workshops and meetings with local action groups (LAGs); brainstorming | Create and analyse scenarios for the future development of PAs—case study on an NP | Management implications—improving the decision-making process for environmental management in NPs | No |

| 29 | 2018 [166] | Turkey | Mixed | Questionnaires (n = 9 respondents) | Determine suitable ecotourism activities in PAs—case study on a natural park | Management/service provider implications—improving the development of ecotourism | Yes |

| 30 | 2017 [167] | Serbia | Mixed | Interview; secondary data | Develop and present the methodology for NP management decision-making | Management/service provider implications—improving the development of ecotourism | No |

| 31 | 2017 [168] | Alps—examples in NPs included, different countries | Qualitative | Workshop (n = 45 respondents) | Analyse management strategies for winter mountain tourism in relation to biodiversity conservation | Management implications—administering visitors in PAs | No |

| 32 | 2017 [169] | Spain | Quantitative | Interview (n = 194 respondents) | Analyse relations between local stakeholders in two historically touristic areas—a NP focused on ecotourism and a snow-tourism region | Service provider/local community implications—improving the collaboration between local stockmen in the area of NPs | Yes |

| 33 | 2017 [170] | Turkey | Quantitative | Semi-structured interview (n = 31 respondents) | Analyse the local guiding activity and its effects on the sustainable management of PAs | Management implications—improving the sustainable management of NPs | No |

| 34 | 2017 [171] | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia | Quantitative | Consultation with administrations; secondary data | Analyse differences in tourism development in NPs based on the existing touristic offer | Management/service provider implications—developing the nature-based tourist offer in PAs; creating mutual tourist services through inter-park cooperation | No |

| 35 | 2016 [172] | Turkey | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 59 respondents); in-depth interview (n = 5 respondents) | Analyse and define the ethical aspects of ecotourism activities | Management/local community implications—applying global ethical certification systems for the development of ecotourism | Yes |

| 36 | 2016 [173] | Turkey | Quantitative | Survey (n = 959 respondents) | Analyse local people’s opinions regarding wildlife and its management, as well as the designation of PAs | Management/local community implications—improving the development of ecotourism | Yes |

| 37 | 2016 [174] | Turkey | Qualitative | Secondary data from a previous study | Analyse the current state of the PA and make proposals for its sustainable development | Management implications—improving the sustainable development of rafting tourism and management in the PA | No |

| 38 | 2016 [175] | Slovakia | Quantitative | Secondary data | Determine stakeholders’ socio-economic interactions, considering demography, land use, and revenues in relation to the PA | Management/local community implications—improving cooperation between population and nature conservation bodies and developing sustainable nature-based tourism | Yes |

| 39 | 2015 [176] | Spain | Quantitative | Workshop (n = 29 respondents) | Analyse “differences in the perception of the spatial distribution of ecosystem services supply and demand between different stakeholders through collaborative mapping” | Management/service provider/local community implications—improving decision-making processes in PA administration | Yes |

| 40 | 2015 [177] | Greece | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 170 respondents); interview (n = 1 respondent) | Analyse the local people’s attitude towards tourism development and their engagement in participatory opportunities | Management/local community implications—improving participatory approaches in PA management | No |

| 41 | 2014 [178] | Sweden | Quantitative | Secondary data on employment | Compare the influence on the labour market between local communities around NPs and nature reserves | Management/local community implications—assessing the impact of nature protection on tourism labour market development | No |

| 42 | 2014 [179] | Germany | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 197 respondents); interview (n = 25 respondents) | Present a complete cost–benefit analysis | Management implications—improving decision-making processes; analysing nature-based tourism benefits in NPs | Yes |

| 43 | 2012 [180] | Czech Republic | Quantitative | Survey (n1 = 181 respondents, n2 = 200 respondents) | Analyse local people’s perception of the success of NP management policies | Management/local community implications—improving PA management policies | Yes |

| 44 | 2011 [181] | Finland | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 185 respondents) | Analyse the attitudes of tourism service providers and decision-makers regarding tourism development—case study on an NP | Management/service provider implications—improving collaboration between service providers and decision-makers for tourism development in NPs | No |

| 45 | 2011 [182] | Turkey | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 500 respondents) | Analyse the carrying capacity of an NP with consideration for its natural and cultural resources | Management implications—improving the sustainable development of NPs with consideration for the carrying capacity | Yes |

| 46 | 2011 [183] | Estonia | Mixed | Questionnaire (n = 273 respondents) | Present the impact of tourism on local communities | Management/local community implications—improving the communication between authorities of NPs and local communities | Yes |

| 47 | 2010 [184] | Slovenia | Qualitative | Interview (n = 4 respondents); secondary data | Create a decision model for infrastructure development in NPs | Management implications—improving the sustainable development of ecotourism | Yes |

| 48 | 2009 [185] | Finland | Qualitative | Semi-structured interview (n = 40 respondents) | Analyse the perceptions of stakeholders on the sociocultural sustainability of tourism—case study on an NP | Management/local community implications—improving the sustainable development of tourism in NPs | Yes |

| 49 | 2008 [186] | Greece | Quantitative | Paper articles (n = 100 articles) | Analyse the representation of three main topics of environment policy in the local press—ecotourism, forest management, and environmental awareness | Management/institution implications—promoting and sustainably developing ecotourism in PAs | No |

| 50 | 2007 [187] | Greece | Quantitative | Questionnaire (n = 276 respondents) | Analyse stakeholders’ points of view on environmental policy for PA management | Management/institution/research implications—measuring the environmental policy beliefs of stakeholders involved in PA management; supporting participatory approaches | Yes |

| 51 | 2006 [188] | Greece | Qualitative | In-depth interview (n = 23 respondents) | Determine the local people’s perception and interpretation of “nature”, “wildlife”, and “landscape” in the context of a PA | Management/local community implications—improving participatory approaches in PA management, environmental conservation awareness, and quality of life in local communities | No |

| 52 | 2000 [189] | Turkey | Quantitative | Survey (n = 15 respondents) | Create an ecosystem zoning procedure to determine its suitability for human activities | Management implications—improving the sustainable development of NPs | No |

Note: The objectives of the research are based on the authors’ mentions and may partially duplicate their stated goals. Source: own elaboration. * Year of Early Access as appeared on the WoS database at the time of data collection.

The reduced number of articles focused on other stakeholders in comparison with the ones that address tourists directly could be explained not through reduced interest but rather through the increased complexity of the methodology. A significant number of studies involving stakeholders use qualitative methods, such as interviews, which can better capture their opinions. This implies a longer participation time; thus, data can be more difficult to obtain and the response rate can be lower [190] (p. 344).

The applicability of the research papers that have been reviewed resides in, among others, providing deeper insight into the commonly encountered challenges and helping decision-makers improve their management acumen while respecting all parties concerned.

Considering the Web of Science categories, as shown in Table 6, the ones concerning environmental studies and ecology have recorded the most articles focused on various stakeholders other than tourists. “Environmental Sciences” covers 48% with the highest number of articles, and of all 52 studies analysed, 28 were identified within two or more WoS categories.

Table 6.

Top 10 WoS categories by the number of identified articles focusing on stakeholders.

Within the 37 different journals that published the 52 analysed articles included in this section, most papers are found in Sustainability (12%), Polish Journal of Environmental Studies (6%), and Forest Policy and Economics (6%).

Almost half of all the papers focusing on various stakeholders that were included in the present study (46%) were published in one of the 9 journals presented in Table 7. Unlike the articles that focused on understanding tourists’ behaviours and preferences, most of the ones that address other categories appear in journals with a lower impact factor.

Table 7.

Top 9 journals with the highest number of published studies focusing on other stakeholders.

The keyword with the highest frequency for articles focused on stakeholders other than tourists is again referring to an area of interest—the national parks, summing a 7% frequency, accounting for 15 entries out of 213 different keywords. Unlike previously analysed, “sustainable development” is also registered as an important label for this category of research (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Keywords with the highest frequency in articles focused on other stakeholders. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by WoS.

Among the articles that appear to have raised the most interest among other researchers, according to the number of citations registered on the WoS database, “Collaborative mapping of ecosystem services: The role of stakeholders’ profiles” [176] (81 citations), “Can nature-based tourism benefits compensate for the costs of national parks? A study of the Bavarian Forest National Park, Germany” [179] (52 citations), and “Hybrid SWOT—ANP—FANP model for prioritization strategies of sustainable development of ecotourism in National Park Djerdap, Serbia” [167] (50 citations) are the highest regarded. The top 10 most cited articles included in this section of the present review are illustrated in Table 8.

Table 8.

Top 10 most cited published articles focusing on other stakeholders according to the WoS number of citations.

Most study cases and research scenarios have been developed and analysed throughout Europe, with a higher incidence in Turkey (17%), Spain (15%), and Serbia (12%), followed by Finland (8%) and Greece (8%), which can be observed in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Percentage of articles by country in Europe focusing on other stakeholders as reviewed in this research. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by WoS.

Funding plays a fundamental role in facilitating the study of the influence, approach, and attitudes of stakeholders involved in organising nature-based tourism in national and natural parks, as previously stated in connection with the research focused on understanding tourists. Out of the 52 papers included in the present section, 56% have received financial support from different institutions, which confirms the interest and need for research on the subject to improve the decision-making process at all levels (management and administration of protected areas, local communities, and service providers, as well as others concerned).

Although quantitative methods of analysing collected data still prevail (50%), the different nature of subjects approached while studying categories of stakeholders other than tourists requires different instruments. Thus, 17% of the papers used qualitative methods for data analysis, and 33% used mixed methodologies. Most often, the instruments used for data collection are a questionnaire or interview, but workshops and focus groups are also occasionally preferred, depending on the context and parties involved in the research.

Improving and innovating methodologies that enable and assist the sustainable management of protected areas are common goals among various stakeholders and the research community, as reflected in the objectives of numerous papers included in the present study. For example, Job et al. [140] analysed methods to estimate attributes and the volume of visitors, while other authors provided alternative approaches for the decision-making processes concerning protected areas [141,142,156,157,165,167,184].

Some of the articles presented in this section (Table 5) analysed cross-sector collaboration, where institutions, park management boards, service providers, and local communities can become involved for the general benefit of national and natural park administration and address conflicting interests. For example, analysing cross-sector contributions to sustainable mountain tourism development [148] can have implications not only for the park management but also for the service providers and local communities. Analysing the development of ecotourism in relation to the demography, land use, and revenue of local stakeholders [150] can provide valuable knowledge to various institutions, service providers, and residents of parks. Research that can have implications for park management includes, but is not limited to, analysing the balance between tourism and nature conservation [138,139,158,164] or the amount of waste on tourist trails in popular parks [149]. Understanding the carrying capacity of parks with consideration for their natural and cultural resources [182] and creating an ecosystem zoning procedure to determine the suitability for human activities [189] are also important elements for the efficient and durable management of national and natural parks. Presenting a complete cost–benefit analysis for nature-based tourism in parks can help park administration bodies decide how to coordinate human activities within the protected areas [179]. Some articles provided resources to improve the park administration by presenting a decision-making methodology [141,167] or prioritising management strategies [142]. Welling et al. [157] analysed the use of participatory scenario planning for adaptation planning in glacial mountain tourism. Their results can help reduce uncertainty for long-term planning and decision-making in parks.

Involvement of residents and consideration of them in the decision-making process aims at improving their quality of life and the protection of parks at the same time. A few articles included in the present section have potential implications for the residents of national and natural parks and people living in their vicinity. Altunel [145] addressed a subject of potential sensitivity in some cultures—the involvement of local women in ecotourism activities. Other authors analysed the local people’s attitude towards sustainable ecotourism development in parks [151] and their engagement in participatory opportunities [177]. Ristić et al. [162] tried to understand the local population’s opinion on the sustainability of tourism development and its contribution to rural development in parks. Analysing residents’ opinions regarding wildlife and its management, as well as the designation of protected areas [173], can help mitigate the human–wildlife conflict in parks to the benefit of all parties. National parks have strict administration requirements to protect the natural environment, which can sometimes interfere with the lifestyle of residents and their quality of life. Comparing the influence on the labour market between local communities around national parks and nature reserves [178] can provide a better understanding of the degree of influence these conservation measures have on residents.

Applying certain methodologies to address a given subject can have implications for the academic environment, providing knowledge for future studies. For example, analysing the potential of using PPGIS for visitor use planning through a case study on a national park [156] can facilitate future research.

Service providers can improve their awareness and impact on conservation policies when they are included in collaborative actions. Analysing stakeholders’ points of view on tourism development can help create integrated tourism offers in parks [155]. Understanding park authorities’ attitudes towards the organisation of mass sports events in protected areas can address a potential conflict of interest. Suta et al. [171] analysed differences in tourism development in national parks based on the existing touristic offer. Through their research, they can help service providers develop nature-based tourist offers in protected areas and create mutual tourist services through inter-park cooperation.

Some authors deal with themes with potential implications for institutions responsible for tourism policies and regulations. Alcon et al. [163] analysed the social demand for sustainable management of a park to estimate the optimal distribution of the annual budget according to social demand. Hovardas and Poirazidis [187] investigated stakeholders’ points of view on environmental policy for park management, supporting participatory approaches. Hovardas and Korfiatis [186] analysed the representation of three main topics of environment policy in the local press—ecotourism, forest management, and environmental awareness.

5. Discussion

The necessity of a more thorough understanding of the ever-growing tourism industry and a durable approach to its development fueled the present research. With an essential need for exhaustive investigation, supported by an increasing focus on nature protection and defining the benefits of nature-based tourism in the context of today’s global difficulties, this study aims to gather expansive knowledge on the matter that can further benefit researchers.

Although previous research of a similar nature exists, it is usually focused on particular aspects [49,51,54,191], while the results of the present study aim for a broader approach. It was beyond the scope of this article to focus on a certain subject in the sphere of nature-based tourism but rather to account for the existing literature and organise it according to different attributes, such as keywords, journal, the country of the case study, the type of research method applied and the main instrument of data collection, the objective and potential applicability of the study, and the funding status for the research.

The results of this paper show that, without a harmonised definition of nature-based tourism, the scientific community approaches the concept with a wide perspective, which can be concluded from the wide-ranging variety of objectives described in Table 1 and Table 5. This is also emphasised by other authors [11,192]. While some authors focus explicitly on this form of tourism, in a quest to analyse the relevant literature, one should not exclude research that mentions other similar terms. For this reason, it becomes a necessity to place nature-based tourism in relation to other forms of tourism and understand what can be generally included under the same umbrella topic and can become a research pattern.

The data collected for the current study, presented in Table 4 and Table 8, suggest a correlation between the relevance of certain research papers in the academic world and the main themes of interest in analysing the touristic activity in protected areas, such as the tourists’ perception [123], willingness to pay [126], cost–benefit analysis [179], participatory management [176], the crowding effect [128], assessment of the sociocultural sustainability of touristic activities within a national park [185], and residents’ perception of the surrounding natural environment with all its elements [188].

Even if there are profound cultural differences between countries, as well as different policy approaches and extremely varied behaviours, common objectives have emerged from the analysed articles, including testing the efficiency and benefits of cross-sector collaboration and participatory management actions. This finding suggests that conservation efforts can be shared between different actors, ensuring better cooperation, improving existing services, and yielding benefits. This was also supported by Jones et al. [114], Welling et al. [157], and Hovardas and Poirazidis [187].

Understanding the complex mechanisms driving the touristic offer and demand, along with its effects on the environment and the market, should be accompanied by a thorough comprehension of how the enactment of protected areas and the activities occurring within these special territories are influencing the living conditions of residents. While nature-based tourism with its profusion of activities can have both positive and negative effects on the local communities in protected areas, more consistent research is needed, as also emphasised by Thapa et al. [193]. Although most of the reviewed articles are aimed at analysing tourists’ behaviour, the residents of protected areas make a complementary and equally important subject for achieving efficient adaptive management. Understanding both perspectives provides a more comprehensive and realistic basis for management purposes. The reduced number of research papers focused on local communities and various stakeholders other than tourists could raise questions regarding the level of implication or interest in the matter at hand. While the complexity of the subject and the means to tackle it could provide a reasonable answer, the subject is expected to witness an increasing trend in research in the following years, creating a good opportunity for future inquiry.

Research on the nature-based tourism subject is one step towards raising awareness of the economic, social, environmental, and cultural implications of the tourism industry in national and natural parks and creating and applying the best policies to minimise the negative impact and maximise the great benefits it can generate. Covering this research gap in geographical areas where appropriate expertise is lacking, human activity and the incommensurably valuable treasures of nature have the chance to become consonant and balance each other, whether it is about land use, species conservation and research, or achieving a state of physical health and mental well-being as visitors.

Sustainability remains the goal of utmost importance when it comes to the administration of protected areas and their surroundings. In this context, future research can encourage and support better cooperation between the population and conservation bodies for human–wildlife co-existence.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review contributes to a clearer understanding of the concept of nature-based tourism as well as creating a centralised data collection of various research information published between 2000 and 2021 that can be used in future studies. The review indicates a wide variety of methods that can be used to obtain valuable practical information, which has been emphasised through the analysis of the papers’ applicability. The information collected and systematised could also aid other researchers interested in investigating the results of case studies concerning a given topic in the context of nature-based tourism in European national and natural parks. The reliability of the collected data is impacted by the process of registering the full information of new articles, including publication dates. The results can only be generalised in the context of the chosen research database, Web of Science™. Due to the lack of consensus on officially defining nature-based tourism, the results are limited by the selected syntax, as decided by the authors of this paper. The methodological choices were primarily constrained by time and resources, making it difficult to expand the search criteria. Understanding the different interests and concerns of all parties affected can help avoid and mitigate potential conflicts. Therefore, a high potential for future research exists, where this review can be a commencement for deepening knowledge in the quest for understanding tourism in protected areas. Despite the limitations, the results provide new insight into the touristic activity and management of national and natural parks in Europe and can be used as starting material for other literature reviews focused on specific elements of interest. Such research opportunities include analysing the effects of tourism and park designation in balance with wildlife conservation, enriching research material that focuses on communities and their involvement in the administration of protected areas, and creating collaborative studies that include various economic actors and stakeholders in the tourism sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.D. and D.E.D.; methodology, D.S.D. and D.E.D.; formal analysis, D.S.D. and D.E.D.; investigation, D.S.D. and D.E.D.; resources, D.S.D.; data curation, D.S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.D.; writing—review and editing, D.S.D. and D.E.D.; visualisation, D.S.D. and D.E.D.; supervision, D.E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained by contacting the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions: A User-Friendly Framework for the Verification, Design and Scaling up of NbS, 1st ed.; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-2-8317-2058-6. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Policy Brief on Nature-Based Solutions in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Targets; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Part Two). December, 2022. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-cbd-press-release-final-19dec2022 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Elmahdy, Y.M.; Haukeland, J.V.; Fredman, P. Tourism Megatrends: A Literature Review Focused on Nature-Based Tourism; (MINA Fagrapport 42); Norwegian University of Sciences: Trondheim, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, F. A New Approach to Sustainable Tourism Development: Moving beyond Environmental Protection. Nat. Resour. Forum 2003, 27, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T. Tourism in Emerging Economies: The Way We Green, Sustainable, and Healthy; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 9789811524622. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Nascimento, J. Shaping a View on the Influence of Technologies on Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, C.; Garrod, B.; Low, T. The Encyclopedia of Sustainable Tourism; CABI: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-78064-143-0. [Google Scholar]

- Metin, T.C. Nature-Based Tourism, Nature Based Tourism Destinations’ Attributes and Nature Based Tourists’ Motivations. In Travel Motivations: A Systematic Analysis of Travel Motivations in Different Tourism Context; Çakır, O., Ed.; Lambert Academic Publishing: Istanbul, Turkey, 2019; Volume 7, pp. 174–200. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 (RES/70/1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Valentine, P. Review: Nature-Based Tourism; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Björnsdóttir, A.L. Nature Based Tourism Trends: An Analysis of Drivers, Challenges and Opportunities. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, As, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman, P.; Margaryan, L. 20 Years of Nordic Nature-Based Tourism Research: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Tyrväinen, L. Frontiers in Nature-based Tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, P.; Ramakrishna, S.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Nature-Based Solutions in Tourism: A Review of the Literature and Conceptualization. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 442–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoseviciute, G.; Pereira, L.; Panagopoulos, T. The Economic Impact of Recreational Trails: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Ecotourism 2022, 21, 366–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; World Tourism Organization. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008; Studies in Methods, Series M; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-92-1-161521-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, I.D.; Croft, D.B.; Green, R.J. Nature Conservation and Nature-Based Tourism: A Paradox? Environments 2019, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossgard, K.; Fredman, P. Dimensions in the Nature-Based Tourism Experiencescape: An Explorative Analysis. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Tools and Resources for Nature-Based Tourism; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/e51e4a32-2749-5918-8da6-c7b44b67a31f (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Leung, Y.-F.; Spenceley, A.; Hvenegaard, G.; Buckley, R. Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Sustainability, 1st ed.; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-2-8317-1898-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman, P.; Margaryan, L. The Supply of Nature Based Tourism in Sweden. A National Inventory of Service Providers; Mid-Sweden University: Östersund, Sweden, 2014; ETOUR, report 2014:1. [Google Scholar]

- The International Ecotourism Society. What Is Ecotourism? 2015. Available online: https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- World Tourism Organization. The British Ecotourism Market; Special Report; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2001; ISBN 978-92-844-0486-5. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Leader-Williams, N.; Dalal-Clayton, B. Take Only Photographs, Leave Only Footprints: The Environmental Importance; IIED: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-1-904035-24-4. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. Setting an agenda for geotourism. In Geotourism: The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Newsome, D., Dowling, R., Eds.; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Rural Tourism. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/rural-tourism (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Félix, F.; Hurtado, M. Participative Management and Local Institutional Strengthening: The Successful Case of Mangrove Social-Ecological Systems in Ecuador. In Social-Ecological Systems of Latin America: Complexities and Challenges; Delgado, L.E., Marín, V.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 261–281. ISBN 978-3-030-28451-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Nature-Based Solutions. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/our-work/region/europe/our-work/european-nature-based-solutions (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- James, B.; Connolly, M.; MacKay, T. Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Educ. Child Psychol. 2016, 33, 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fälton, E. The Romantic Tourist Gaze on Swedish National Parks: Tracing Ways of Seeing the Non-Human World through Representations in Tourists’ Instagram Posts. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintassilgo, P.; Pinto, P.; Costa, A.; Matias, A.; Guimarães, M.H. Environmental Attitudes and Behaviour of Birdwatchers: A Missing Link. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, J.; Wałdykowski, P. Planning for Sustainable Developmen of Tourism in the Tatra National Park Buffer Zone Using the MCDA Approach. Misc. Geogr. 2022, 26, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]