Abstract

The forest at the Changdeokgung Rear Garden is under ecological threat from factors such as soil acidification due to the growing influence of nearby metropolitan Seoul. It is difficult to maintain biodiversity in forests without first setting a clear direction for ecosystem management. Conservation and management should be based on the history and natural ecological succession of the Rear Garden forest. This study classified the ecology of the Rear Garden at Changdeokgung, a world cultural heritage site, based on soil characteristics, actual vegetation, and plant community structure and identified ecological changes over time (1986–2018) through the analysis of past survey data. The soil pH in the forest of the Changdeokgung’s Rear Garden has decreased over time, and the organic matter content has also decreased. Changdeokgung’s Rear Garden was first created and managed as a Pinus densiflora forest, and subsequently as a Quercus aliena forest. It includes a series of Quercus spp., predominantly Q. serrate. The plant community in the forest is unstable due to the absence of deciduous broad-leaved trees in the understory layer in most of the regions of the garden. Therefore, vegetation management is required in areas with high densities of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Acer palmatum, and Sorbus alnifolia to ensure stability of the ecosystem.

1. Introduction

The forest in the Rear Garden at Changdeokgung dates back to the construction of Changdeokgung Palace in 1405 (the 5th year of King Taejong’s reign). The forest was left unattended for 20 years after the Japanese invasion of Korea but was restored during the reign of the Gwanghaegun of Joseon. The history of the forest extends for 600 years before Gojong rebuilt the Gyeongbokgung. Because the Changdeokgung served as the royal palace during the Joseon dynasty, public access to the Rear Garden was prohibited for many years, but the garden was opened to the public by the Japanese colonial government in 1912. Public access has again been limited since 1976 because of concerns over ecological damage. The Rear Garden at Changdeokgung is an area with high conservation value as it has a large number of old trees, including the natural monuments Juniperus chinensis, Sophora japonica, Actinidia arguta, and Morus alba, and a wide range of good Quercus aliena and Quercus serrata colonies. A 2001 Seoul investigation on superb biotope areas noted that the forest had trees that were large in diameter, old in age and of high conservation value. Thus, the Changdeokgung Rear Garden (area: 440,707 m2) including the Changdeokgung palace has been designated an ecological landscape preservation area in Seoul [1]. The Changdeokgung was registered as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in December 1997 because it is a well-preserved prototypical Joseon-era palace and represents excellent harmony with nature [2]. The site has value because it is a representative palace with informal aesthetics that demonstrate the architectural history of the palaces of Eastern Asia. Looking at the cultural heritage site selection criteria in detail, the palace and gardens correspond to world heritage selection criteria (II), (III), and (IV) [2]. Since the forest of the Rear Garden at Changdeokgung was selected as a World Heritage Site, protection and management of the cultural facilities has proceeded systematically, but the breadth and depth of research that has been done on the natural environment in terms of ecology and the actual vegetation of the forest is insufficient. In the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden, the ecosystem environment continues to deteriorate due to rapid urbanization, soil acidification, and the oak wilt disease. Our hypothesis is that there will be a decrease in the number of trees in the next generation of the ecosystem. Partly because the forest faces various ecological threats, such as soil acidification due to the ongoing influence of metropolitan Seoul, weather-related damage like typhoons, oak wilt disease, and pine wilt disease, it is difficult to maintain biodiversity in forests without first setting a clear direction for ecosystem management. The history of the Changdeokgung is written in the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty and Donggwoldo [3]. In particular, “Donggwoldo (249th National Treasure of South Korea),” which was written in around 1830, depicts the site plan and building structure of the Changdeokgung and is a valuable resource for research into the history and architecture of the palace. Research on the Changdeokgung includes “Yuanyou of the Changdeokgung and the Jongmyo” [4] and the “Seoul Landscape Conservation Area Management Plan Report” [5]. The Cultural Heritage Administration [4] suggested a vegetation and management plan for the Changdeokgung, and there exists some phytosociological research on the vegetation of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden [6] as well as research into the site’s characteristics and planting pattern with a focus on the Donggwoldo [7]. A research team at the University of Seoul conducted the first study on the ecosystem of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden in 1986 and investigated the vegetation distribution, Plant community structure, avifauna, and soil in 1990, 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, and 2006. Also, the Seoul metropolitan government established comprehensive inorganic environment, plant ecology, animal ecology, ecological change and diagnosis, and management plans on the basis of its first precision monitoring effort (2008–2009) [1] and in its second effort (2017–2018) [8]. This study aims to obtain objective and precise data through ecological monitoring of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden and identify the characteristics and changes in the natural ecosystem of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden through a comparative analysis with past survey data.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Area

The Changdeokgung is located in Yulgok-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul (37°34′45″ N, 126°59′27″ E). It is the 122nd historic site in South Korea. The size of the Rear Garden is approximately 34.192 ha. The Changdeokgung is the palace of the Joseon dynasty; it is located at the foot of Eungbong, the left peak of Bukaksan. The Rear Garden was constructed at the founding of the Changdeokgung in the 5th year of Taejong’s reign (1405) and was connected with the Changdeokgung. The Changdeokgung Rear Garden is a representative of the traditional Korean garden. Most of the pavilions (Jung-Ja) were destroyed during the Japanese invasions of Korea. The remaining pavilions and palace buildings have been renovated and enlarged since the first year of the Injo of Joseon (1623). The climate of Seoul, where Changdeokgung is located, is classified as Dwa according to Köppen’s climate classification, and is also classified as a wet continental climate. It is a continental climate with a large annual temperature intersection. It is a moderate climate between temperate and cold climates. In the last 30 years (1991–2020), the average annual temperature in Seoul is about 12.8 °C, with the average temperature in August being 26.1 °C and an average temperature of −1.9 °C in January.

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Soil Environment

In order to assess the health of the forest at the Changdeokgung Rear Garden, the physicochemical properties of the soil were investigated. Soil samples collected from fixed survey plots were analyzed. Soil samples were collected randomly by selecting one location for each survey plots. The size of the pit from where the topsoil sample was collected was 30 cm × 30 cm, and the depth was 0~15 cm. The physical and chemical properties of the soil were analyzed based on the soil test results obtained from a specialized soil analysis institution. The analysis items included soil texture, soil pH, and content of organic matter, available phosphate, and exchangeable cations (Ca, Mg, K, Na). The results were compared and analyzed with data from surveys conducted in 1986, 2001, 2007, and 2018.

2.2.2. Actual Vegetation

Actual vegetation can present the distribution area and the coverage of tree species by correlation analysis of trees. In order to identify changes in the distributions of the dominant vegetative communities in the forest of Changdeokgung Rear Garden, a vegetation map that depicts the vegetation physiognomy of the canopy layer was built on top of a 1/1000 digital topography map from the Seoul Metropolitan Government. Changes in vegetation were analyzed based on actual vegetation maps created in 1986, 2009, and 2018.

2.2.3. Plant Community Structure

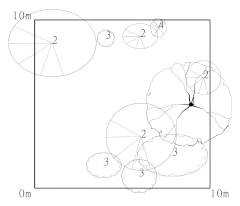

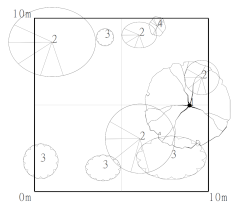

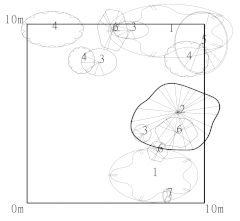

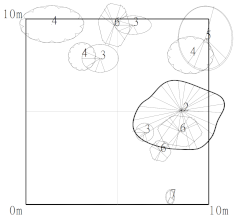

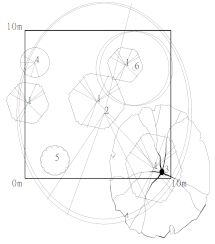

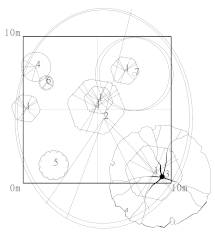

Plant community structure includes both the individual plant species and plant specifications. The plant community structure was investigated using the Quadrat method. The target sites consisted of 30 fixed survey plots established by the Environmental Ecology Laboratory of the University of Seoul in 1988 (Figure 1). Representative plots were set for each type of existing vegetation community in the forest of the Changdeokgung’s Rear Garden. With reference to the method described by Monk et al. [9], a survey of the plant community structure was conducted to measure diameter at breast height (DBH) (cm), height (m), crown height (m), and width of the crown (m × m) of tree species with a DBH of 2 cm or more appearing in each survey plot. For shrub layers, height (m), crown height (m), and width of the crown (m × m) were surveyed. All survey plots were prepared using crown projection maps of the canopy and understory layers. In this paper, we include one site where trends in ecosystem changes by vegetation cluster are observed. In order to measure the growth of the trees, after selecting one tree corresponding to the average DBH among the dominant species for each surveyed plots, annual rings were extracted using an increment-borer, and age and annual growth were determined. The fixed survey plots included communities of Quercus aliena, Quercus serrata, Quercus mongolica, Quercus variabilis-Quercus mongolica, Zelkova serrata, and Castanea crenata. The total number of plots were 30 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Locations of the fixed survey plots in the forests of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

Table 1.

Fixed survey plots in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

2.2.4. Analysis Items

Based on the survey data, the importance percentage (IP) of each plot was estimated, and the Shannon diversity index [10], max diversity index (H′max), evenness (J′), and dominance (D) were recorded. Additionally, the species diversity index and the variations of species and population in each fixed plot were compared between 1998 and 2018 (in years 1998, 2013, and 2018). To compare the relative dominance between species based on the crown layers of each plot, the IP was estimated based on the Curtis and McIntosh method [11]. For each layer, the mean IP was estimated as follows [12]:

To measure the species diversity index (a measure of the varying degrees of species composition), the Shannon species diversity index [10], max diversity index (H′max), evenness (J′) and dominance (D), which places more importance on rare species, were estimated. The species diversity index analysis was limited to tree species.

In the Shannon calculation:

where pi is the ratio of the total population of a given species to the total population of all species and S denotes the number of species.

species diversity index (H′) = −∑ pi log pi

max diversity index (H′max) = log S

Evenness (J′) = H′/H′max

Dominance (D) = 1 − J′

3. Results and Review

3.1. Soil Environment

According to the 2018 soil environment analysis, the soil textures in the garden were sandy loam, silt loam, and loam. The soil pH ranged from 4.16 to 5.37, with a mean of 4.39, which is lower than pH 4.80 [13], the mean pH of soil in uncultivated mountain regions. Soil acidification proceeded until 2001, with a pH of 4.77 in 1986 and 4.11 in 2001; however, the acidity of the soil decreased markedly in 2007, when the mean pH was 5.33. The analysis of soil pH in 2018 suggested that improvements in the soil environment were needed at that time due to the increase in soil pH caused by proximity to the urban environment. The organic matter content was just 4.14% in 1986, 6.04% in 2001, 4.16% in 2007, and 2.18% in 2018; all of these measurements are much lower than 6.40%, the mean organic matter content of uncultivated soil in mountainous regions. Thus, improvements in the soil environment are needed to bring about an increase in organic matter content. The available phosphate concentration ranged from 32.96 to 75.87 mg/kg, with a mean of 44.35 mg/kg.

Due to continuous application of fertilizers, the level of available phosphate in the Changdeokgung Rear Garden was high until 1986. After 1986, the level of available phosphate dropped continuously due to natural leaching, but it recently increased again due to interventions such as fertilization. Regarding the levels of exchangeable cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Na+, the levels of the first three cations were greater in the most recent measurements than in the measurements taken in 2007, so continuous fertilization was effective (Table 2). Regarding the soil environment, the overall soil pH has increased and the organic matter content decreased over time, which suggests the need for improvements in the soil environment. Also, the levels of available phosphate and exchangeable cations have risen, thus continuous fertilization was effective in this regard. In the future, it is necessary to identify the changes in plant communities that occur due to changes in the soil environment through continuous monitoring.

Table 2.

Changes in physico-chemical properties of the soil in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

3.2. Changes in Vegetation over Time

According to the Donggwoldo, a painting created from 1826 to 1830 revealed that there were 11 species of trees including Pinus densiflora, Sophora japonica, Kalopanax pictus, and Zelkova serrata planted in the Changdeokgung [14,15]. Pinus densiflora are abundant in the northern forest and most parts of the southern ridge forest of the palace garden, and deciduous broad-leaved trees can be found in the valley. In the actual vegetation map of the Changdeokgung from 1986, which was confirmed by Oh and Lee [6], most of the northern Changdeokgung forest consisted of Quercus aliena, while artificial forests consisting of Castanea crenata, Ailanthus altissima, Populus tomentiglandulosa, and Populus euramericana were widely distributed in the southern part of the forest. Table 3 shows a comparison of the area and proportion of major vegetation type in 1986, 2007, and 2018 (Figure 2). Most areas were dominated by species of oak, such as Quercus aliena, Quercus serrata, and Quercus mongolica, and the proportion of oak trees increased from 48.1% in 1986 to 48.3% in 2007, then decreased to 42.9% in 2018. The proportion of communities dominated by Pinus densiflora showed an increasing trend over time (from 0.5% in 1986 to 3.7% in 2007 and 7.8% in 2018), as did the proportion of communities dominated by Zelkova serrata (from 6.0% in 1986 to 6.0% in 2007 and 10.9% in 2018). The prevalence of communities dominated by deciduous broad-leaved trees, such as Sophora japonica, Prunus padus, and Prunus sargentii R. was 7.1% in 1986, 2.8% in 2007, and 4.3% in 2018. The greatest changes in vegetation over time from 1986 to 2007 and then to 2018 were the rapid decrease of the Quercus aliena community and an increase in the Pinus densiflora and Zelkova serrata communities due to succession. The change is attributed to the expansion of the remaining Zelkova serrata community and planting of Pinus densiflora in areas where oak trees were declining. A field survey in 2013 revealed various problems, such as withering of trees and weakening of the vigor of oak species due to oak wilt disease; canopies inside the forest were found to be open due to various human interference. The 2018 field survey showed that oak species continued to decline in terms of both population and vegetation coverage, and only Zelkova serrata had maintained its community. In the understory layer, the communities of Acer palmatum, Acer pseudosieboldianum, and Sorbus alnifolia had increased significantly at that time. Also, there was widespread extinction of several components of the artificial forest, such as Ailanthus altissima, Populus tomentiglandulosa, and Populus euramericana, an increase in planting of landscape trees, and a decrease in artificial pasture lands and bare land. The cause is believed to date to 1986 when Ailanthus altissima forest, artificial mixed forest, bare land, and artificial pasture lands, which were distributed in the southwestern part of the site, were restored by planting Pinus densiflora.

Table 3.

Variation in the actual vegetation in ecological landscape preservation areas of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden in a 32-year period (1986–2018).

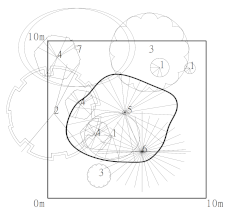

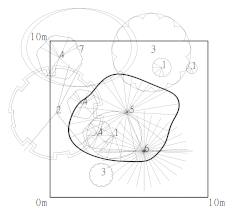

Figure 2.

Actual vegetation map of the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden (Year: 2018).

3.3. Plant Community Structure

3.3.1. Quercus serrata Community (Plot no. 7)

The Quercus serrata community represents the most typical tree in the temperate southern forest; such communities are widely distributed around the Taebaek Mountains. Compared to inland regions, some communities on the east and west coasts have been found at more northern latitudes [16]. The species analysis revealed that Quercus serrata was dominant in the canopy layer, while the understory layer consisted of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Styrax japonica, and Sorbus alnifolia, and the shrub layer consisted of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Stephanandra incisa, and Quercus mongolica. In terms of mean importance percentage (MIP), Quercus serrata in the canopy layer was highest at 50.00%, followed by Acer pseudosieboldianum in the understory layer at 27.40% and Styrax japonica at 13.72%. In the shrub layer, Acer pseudosieboldianum, Stephanandra incisa, and Quercus mongolica were dominant. There were a total of six species and 26 individuals. The Shannon diversity index decreased from 0.6642 in 2013 to 0.6390 in 2018, and the degree of dominance of Quercus serrata and Acer pseudosieboldianum was high. Thus, the overall species diversity index was low. The age of the Quercus serrata sample tree was 102 years (Figure 3). In the Quercus serrata community, Quercus serrata was dominant in the canopy layer, while in the understory layer, urbanization indicator species [17] such as Acer pseudosieboldianum, Styrax japonica, and Sorbus alnifolia had high importance percentages (IPs). In the Quercus serrata community (survey plot no. 7), it was difficult for the tree species that dominated the understory layer to also dominate the canopy layer, so the community was able to maintain stability (Table 4).

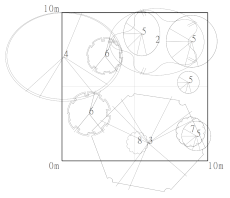

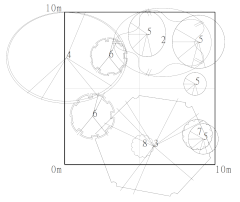

Figure 3.

Tree age and growth of the Quercus serrata sample tree in fixed survey plot no. 7 in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden. Black line in the figure shows the annual rings of the late wood.

Table 4.

Plant community structure of the Quercus serrata community (survey plot no. 7) in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

3.3.2. Pinus densiflora—Pinus koraiensis—Quercus variabilis Community (Survey Plot No. 12)

Pinus densiflora communities are distributed throughout Korea with the exception of the highlands in Hamgyeong-do and Pyeongan-do. Growth areas are found in land with dry soil and good drainage, such as special forests on slopes like ridges and rock faces [16]. Inside Changdeokgung, vegetation colonies which are believed to have been Pinus densiflora communities in the past have been succeeded by various different types of vegetation. Survey plot no. 12 was located in the forest slope on the east side of the Changdeokgung. The species analysis showed that the canopy layer consisted of Castanea crenata, Pinus koraiensis, Quercus variabilis, and Pinus densiflora, while the understory layer consisted of Sorbus alnifolia, Acer pseudosieboldianum, Styrax japonica, and Viburnum erosum. Acer pseudosieboldianum, Styrax japonica, Viburnum erosum, and Quercus acutissima were found in the shrub layer. In terms of mean importance percentage (MIP), Castanea crenata was dominant in the canopy layer at 17.54%, followed by Pinus koraiensis at 11.22%, Quercus variabilis at 10.77%, and Pinus densiflora at 10.48%. In the understory and shrub layers, the percentage dominance of Acer pseudosieboldianum was 19.56%, that of Sorbus alnifolia was 18.88%, and that of Styrax japonica was 7.75%. The MIP of urbanization indicator species was high, and Rhododendron mucronulatum, Robinia pseudoacacia, Styrax japonica, and Quercus mongolica grew on a small scale. There were a total of 11 species and 94 individuals. The Shannon diversity index decreased from 0.8603 in 2013 to 0.7442 in 2018, and the dominance of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Sorbus alnifolia and Castanea crenata was high, so the overall species diversity index was low. In this community, Castanea crenata and Pinus densiflora competed in the canopy layer. In the understory layer, urbanization indicator species such as Acer pseudosieboldianum, Sorbus alnifolia, and Castanea crenata showed high IPs, but it was difficult for these species to develop species dominance in the canopy layer. Consequently, in the current state of the forest, Castanea crenata, Pinus densiflora, Pinus koraiensis, and Quercus variabilis demonstrate a considerable degree of competition with each other. In the future, Robinia pseudoacacia, which appeared in the canopy layer, may induce a stable indigenous ecosystem through management of disturbance species (Table 5).

Table 5.

Plant community structure of the Pinus densiflora—Pinus koraiensis—Quercus variabilis community (survey plot no. 12) in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

3.3.3. Quercus mongolica—Pinus densiflora Community (Survey Plot No. 17)

Quercus mongolica is the dominant species in central temperate forests and is mainly distributed on northern slopes and ridges [18]. In the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden, the Quercus mongolica community was small in scale. This was evident in survey plot No. 17, which was located on the forest slope of the western side of the Changdeokgung. The analysis of appearing species showed that Pinus densiflora was dominant in the canopy layer; the understory layer consisted of Styrax japonica, Prunus sargentii R., Sorbus alnifolia, Acer pseudosieboldianum, and Rhododendron mucronulatum; and the shrub layer consisted of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Callicarpa japonica Thunberg, Viburnum erosum, Rhododendron mucronulatum, Zelkova serrata, and Sorbus alnifolia. In terms of MIP, Quercus mongolica was dominant in the canopy layer, at 50.00%, and Acer pseudosieboldianum was dominant in the understory layer, at 12.51%, followed by Styrax japonica at 9.79%, Sorbus alnifolia at 8.56%, and Prunus sargentii R. at 7.94%. In the shrub layer, Acer pseudosieboldianum was dominant; other species also appeared but did not dominate. There were a total of 12 species and 52 individuals. The Shannon diversity index decreased from 0.9050 in 2013 to 1.0232 in 2018. In the Quercus mongolica—Pinus densiflora community, in 2018, only Pinus densiflora was dominant because pre-existing Quercus mongolica was killed by oak wilt disease. In the understory layer, urbanization indicator species such as Acer pseudosieboldianum, Styrax japonica, and Sorbus alnifolia had high IPs, but it was difficult for these species to develop dominance in the canopy layer. Thus, we concluded that Pinus densiflora may become the dominant species in this area of the forest in the near future (Table 6).

Table 6.

Plant community structure of the Quercus mongolica—Pinus densiflora community (survey plot no. 17) in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

3.3.4. Quercus variabilis—Quercus mongolica Community (Survey Plot No. 19)

Quercus variabilis grows mainly in barren and sunny areas, such as valleys, forest ridges, or rugged areas [16]. Survey plot no. 19 was located on the forest slope of the western side of the Changdeokgung. The analysis of appearing species showed that the canopy layer consisted of Quercus variabilis and Quercus mongolica, while the understory layer consisted of Sorbus alnifolia, Prunus sargentii R., and Acer pseudosieboldianum, and the shrub layer consisted of Quercus variabilis and Quercus mongolica. In terms of MIP, Castanea crenata was dominant in the canopy layer, at 33.37%, followed by Quercus mongolica at 23.07%. In the understory layer, Sorbus alnifolia was dominant at 10.39%, followed by Prunus sargentii R. at 9.44% and Acer pseudosieboldianum at 7.42%. In the shrub layer, Styrax japonica and Zelkova serrata were dominant; other species also appeared, but did not dominate. There were a total of 11 species and 150 individuals. The Shannon diversity index decreased from 0.7518 in 2013 to 0.5823 in 2018, and the dominance of Quercus variabilis and Sorbus alnifolia was high, so the overall species diversity index was low. In the Quercus variabilis—Quercus mongolica community in the canopy layer, the existing Quercus variabilis and Quercus mongolica competed with each other. In the understory layer, Prunus sargentii R., Acer pseudosieboldianum, and Sorbus alnifolia had high IPs. In this community, it is expected that Prunus sargentii R., which may develop into the dominant tree in the canopy layer, will become dominant. In this plot, we predict that Quercus variabilis and Quercus mongolica will continue to compete with each other in this area of the forest (Table 7).

Table 7.

Plant community structure of the Quercus variabilis—Quercus mongolica community (survey plot no. 19) in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

3.3.5. Prunus sargentii R.—Quercus serrata Community (Survey Plot No. 20)

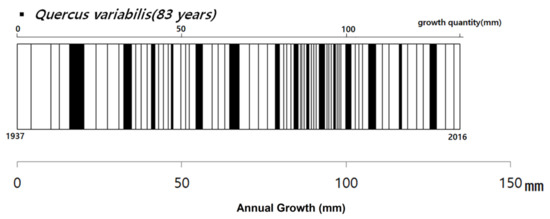

Prunus sargentii R. is a type of deciduous broad-leaved tree that grows in valleys and can generally be found from the shrub layer to the lower part of the canopy layer, but sometimes grows to the full level of the canopy layer. Survey plot no. 20 was located in the forest slope of the northern side of the Changdeokgung. The analysis of appearing species showed that the canopy layer consisted of Prunus sargentii R., Quercus serrata, and Quercus variabilis, while the understory layer consisted of Sorbus alnifolia, Styrax japonica, and Acer pseudosieboldianum. The shrub layer consisted of Zelkova serrata, Viburnum erosum, and Rhododendron mucronulatum. In terms of MIP, Prunus sargentii R. was dominant in the canopy layer at 25.45%, followed by Quercus serrata at 14.21% and Quercus variabilis at 10.35%. Sorbus alnifolia was dominant in the understory layer at 27.61%. In the shrub layer, Zelkova serrata, Viburnum erosum, Rhododendron mucronulatum, Styrax japonica, and Castanea crenata were partially dominant. There were a total of 12 species and 102 individuals. The Shannon diversity index decreased from 0.8360 in 2013 to 0.8284 in 2018, and the dominance of Sorbus alnifolia, Prunus sargentii R., and Quercus serrata was high, so the overall species diversity index was low (Table 8). The Quercus serrata sample tree was 83 years old (Figure 4). In the Prunus sargentii R.—Quercus serrata community, the existing Prunus sargentii R. was dominant and competed with Quercus serrata and Quercus variabilis. In the understory layer, urbanization indicator species such as Acer pseudosieboldianum, Styrax japonica, and Sorbus alnifolia had high IPs, but it was difficult for any species that dominated the understory layer to develop in the canopy layer. It is expected that Prunus sargentii R. will remain dominant in this area of the forest for the time being.

Table 8.

Plant community structure of the Quercus serrata—Quercus mongolica community (survey plot no. 19) in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden.

Figure 4.

Tree age and growth of the Quercus serrata sample tree in fixed survey plot no. 20 in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden. Black line in the figure shows the annual ring of the late wood.

Regarding the variation in species diversity index in the fixed survey plots in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden, the species diversity index decreased over time in 17 out of 30 surveyed plots (Table 9). This was because urbanization indicator species became dominant and species with weak resistance struggled with graft-taking due to soil acidification. Therefore, management of the effects of continuous urbanization and soil acidification in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden is required. Fixed survey plot nos. 4, 16, and 17 showed decreases in species diversity until 2013 due to the effect of urbanization, but species diversity increased in 2018 in these areas because opening of the crown induced invasion by various shrubs after oak wilt disease was controlled.

Table 9.

Changes in species diversity index of the fixed survey plots of the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden (1998–2018) (unit area: 100 m2).

4. Conclusions

This study classified the ecology of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden, a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site, based on soil environment, actual vegetation, and plant community structure and sought to identify ecological characteristics and changes from 1986 to 2018 through an analysis of survey data. Also, future changes in vegetation were predicted, and an appropriate management plans were sought.

The soil pH in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden has risen continually over time, with a concomitant decrease in the organic matter content. Also, the levels of both available phosphates and exchangeable cations increased over time due to continuous fertilization. It is necessary to identify changes in plant communities due to changes in the soil environment through continuous monitoring. Examining the characteristics of the actual vegetation showed that the Quercus aliena community covered the largest land area in 1986 (41.0% of the total area of the forest), but the coverage declined to 20% in 2007 and just 5.0% in 2018. On the other hand, the Pinus densiflora community accounted for 0.5% of the total area in 1986 but increased to 3.7% in 2007 and 7.8% in 2018. Also, the Zelkova serrata community accounted for 4.7% of the total forested area in 1986, and rapidly increased to 6.0% in 2007 and 10.9% in 2018. These changes were attributed to planting of new Pinus densiflora in communities dominated by other introduced species and the fact that the population of oak trees declined in most of the forest, as well as the fact that the Zelkova serrata population in the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden naturally expanded over time. Overall, the dominance of Quercus variabilis was greatly reduced and the dominance of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Sorbus alnifolia and Acer palmatum increased over time. Additionally, regarding managed plants, woody plants like Paulownia tomentosa, Ailanthus altissima, Prunus padus, and Pueraria lobata were continuously present, as were grasses such as Humulus japonicus, Eupatorium rugosum, Phytolacca americana, and Ambrosia trifida. Thus, intensive management is required to mitigate the effects of organisms that disturb the ecosystem. The analysis of changes in the plant community structure showed that Quercus spp., including Quercus serrata and Quercus aliena were dominant in most communities. In the understory layer, Quercus spp. including Quercus serrata and Quercus aliena, which produced progeny in the succession stage, did not appear, so the communities were believed to be unstable. Therefore, vegetation management is necessary in areas with high densities of Acer pseudosieboldianum, Ambrosia trifida, and Sorbus alnifolia to control the vegetation density and encourage succession to a stable ecosystem through supplementary planting of deciduous broad-leaved trees that can give rise to progeny. This phenomenon can also be observed in other countries. For instance, sustaining the levels of oak (Quercus spp.) stock in eastern North American forests is posing a challenge. Declining oak forests is a worldwide phenomenon, and the replacement of oak by other species in both regenerating and old-growth forests has been reported throughout the natural range of oak in the northern hemisphere [19].

The vegetation of the forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden is in a state of succession from a coniferous forest dominated by species such as Pinus densiflora to a deciduous broad-leaved tree forest dominated by Quercus spp. Quercus spp. are currently dominant in some parts of the forest; for example, Styrax japonica, Sorbus alnifolia and Acer palmatum are dominant in the understory and shrub layers of several plots. Thus, the Changdeokgung Rear Garden is expected to slowly proceed with succession into a forest dominated by Carpinus laxiflora even as the populations of Quercus spp. in the forest are maintained. The forest of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden World Cultural Heritage Site is currently designated as an ecological landscape preservation area. It is the subject of regular partial monitoring of natural ecosystems to measure the inorganic environment, vegetation, etc. In the future, in the forests of the Changdeokgung Rear Garden, ecological change must be continuously identified through monitoring of all aspects of the ecosystem. Also, wise conservation and management strategies are required based on the history and natural ecological succession of the Rear Garden forest.

Author Contributions

B.-H.H. designed the research, S.-C.P. wrote the paper. J.-I.K. and J.-Y.K. reviewed. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Management Plan of Ecological Landscape Preservation Areas in the Changdeokgung’s Rear Garden (1st year). Seoul; 2009. Available online: https://url.kr/4m2Zbs (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- UNESCO World Heritage Center. World Heritage List: Changdeokgung Palace Complex. 1997. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/816 (accessed on 7 December 1997).

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Donggwoldo. Korea University Museum, National Treasure 249-1. Available online: https://url.kr/VWR3Qr (accessed on 3 March 2018).

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Yuanyou of the Changdeokgung and the Jongmyo Investigation Report. 2002. Available online: https://url.kr/4D9d5i (accessed on 30 November 2014).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul Ecological Information. Seoul; 2006. Available online: https://url.kr/ElJqpN (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Oh, K.K.; Lee, K.J. Phytosociological Studies on Natural Vegetation in Hoo-Won, Changduk Palace. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Architect. 1986, 14, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Shim, W.K. Analysis of the Status of Plants and the Characteristicsting on the Donggweol-do. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Architect. 2007, 25, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Management Plan of Ecological Landscape Preservation Areas in the Changdeokgung’s Rear Garden (2nd year). Seoul; 2018. Available online: https://opengov.seoul.go.kr/scholarship/12075008 (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- Monk, C.D.; Child, G.I.; Nicholson, S.A. Species diversity of a Stratified Oak-hickory community. Ecology 1969, 50, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E.C. Mathematical Ecology; John Whiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, J.T.; McIntosh, R.P. An upland forest continuum in the prairie-forest border region of Wisconsin. Ecology 1951, 32, 476–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.H.; Ryu, S.B.; Kim, R.H. Forest structure in relation to altitude and part of slope in a valley forest at Odaesan National Park. Koran J. Environ. Ecol. 1996, 9, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Yun, J.Y.; Yoo, S.H. Distribution of Cs-137 and K-40 in Korean soils. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 1995, 28, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, W. Analysis of Ecological Characteristics and Management Model for the Naturalness Enrichment of the Urban Green Space: A Case Study of Seoul City. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Seoul, Seoul, Korea, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Analysis of Major Vegetation in Donggweol (Changdeokgung, Changgyeonggung) and Research on the Archetypes of Cover Facilities. 2016. Available online: https://url.kr/32PWwA (accessed on 7 September 2017).

- Chung, T.H.; Lee, W.C. A study of the Korean woody plant zone and favorable region for the growth and proper species. J. Sungkyunkwan Univ. 1965, 10, 329–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J.I. A Study on Vegetation Structure Characteristics and Ecological Succession Trends of Seoul Urban Forest, Korea. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Seoul, Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Bae, B.H.; Chun, Y.M.; Chung, H.R.; Hong, M.P.; Kim, Y.O.; Kil, J.H. Community structure and soil environment of Quercus mongolica forest on Mt. Chiljelbong. J. Basic Sci. 1998, 23, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, D.C. Sustaining oak forests in eastern North America: Regeneration and recruitment, the pillars of sustainability. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 926–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).