Abstract

Cultural ecosystem services are nonmaterial benefits that individuals acquire from the ecosystem, such as recreation, aesthetic enjoyment, and tourism. The quantification of cultural services is considered difficult to accurately make compared to other forest ecosystem services. Although some studies evaluate cultural services from forest recreation, “simple quantification” based on easy-to-obtain data is criticized for disregarding the local context and missing essential details. Therefore, this study evaluates a structure providing cultural services, and the local or detailed factors missed by simple quantification, while illustrating objective and statistical evidence with careful observations and a comprehension of local society. This study focuses on urban resident participation in natural resource management through recreational activities in Japanese mountain villages, using Fujiwara District, Minakami Town, Japan, as a case study, and by conducting a quantitative text analysis of 424 essays containing participants’ experiences and impressions. Using the software KH Coder, the Jaccard index is used to calculate co-occurrence relationships between frequently used words, visualizing the results in a network diagram. Additionally, several codes are added to keywords that characterize this case, and correlations between each code are examined. From the analysis, we discovered that social factors, such as interaction with comrades and locals, considerably influence participants’ positive emotions.

1. Introduction

Forests have traditionally provided people with timber and other products; however, “new” services, such as disaster prevention, climate change mitigation, and health promotion, are being noticed [1]. This adjective of “new” emanates not from changes of forest supplies, but rather changes in our demands, shifting from provisioning services to regulating and cultural services. Additionally, areas benefiting from forest ecosystem services expand to larger areas, including urban areas [2].

Sustainable performance of forest ecosystem services requires (1) the appropriate management of natural resources and (2) quantitative evaluation of services. Regarding (1), we must address overuse and underuse problems of resources. Underuse problems mean a decline in ecosystem services due to the abandonment of resource use and arise primarily in advanced industrial countries [3,4,5]. The traditional resource management decline in these countries requires implemented shifts, from provisioning services to regulating and cultural services. For instance, the implementation of Payments for Ecosystem Services schemes [6,7] for regulating services and resource management through recreational activities for cultural services [8,9,10]. Regarding (2), although some researchers have attempted quantitative evaluation since the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) in the early 2000s [11,12], the results disagree with each ecosystem service. Provisioning and regulating services can be estimated to some degree by the examination of forest resources stock or biogeochemical cycles, and can be mapped according to vegetation, climatic conditions, etc. [13]. However, cultural services extending over various categories (Table 1) have problems regarding quantification without double counting or misleading interpretations [14]. As a result, governments have frequently adopted a simple and rough evaluation index, such as the number of religious ceremonies or national park visitors [15].

Table 1.

The categories and their explanations of cultural ecosystem services by MA (listed from [12]).

Despite these difficulties, some studies have evaluated cultural services quantitatively, fixated on the category of “recreation and ecotourism” [14,16]. For instance, mapping of cultural services estimated from the ecosystem function and accessibility [17] and identifying objects contributing to recreation using automated image recognition from social media photographs [18] have been attempted. Moreover, the TEEB project [19] stated that the economic valuation of recreation develops annually [20,21]. Through a literature review or qualitative research, some researchers have criticized quantification using data that are easy-to-obtain and measure (hereinafter referred to as “simple quantification”) due to the possibility of disregarding the local context and missing essential details [16,22,23]. Alternatively, while cultural services can be defined as the nonmaterial benefits of the ecosystem that individuals derive from “human-ecological relations” [24] (p. 206), they indicate that simple quantification cannot measure “human-ecological relations”. However, these attitudes toward the estimation of cultural services are due to the differences in research methods (quantitative or qualitative), causing inconsistent discussions or results. Therefore, it is important to clarify what simple quantification overlooks to promote an animated discussion based on objective evidence.

This study was undertaken to structurally define factors that provide cultural services using quantitative text analysis of essays from forest recreation participants. In other words, this study verifies factors that generate positive emotions, such as “pleasant” or “wonderful” for participants. This study focuses on the case in which urban residents participate in natural resource management through forest recreation in Japanese mountain villages using Fujiwara District, Minakami Town, Japan, as a case study because it contributes to both (1) and (2) stated in the category of “recreation and ecotourism”.

2. Objects and Methods

2.1. Objects of the Study

2.1.1. Outlines

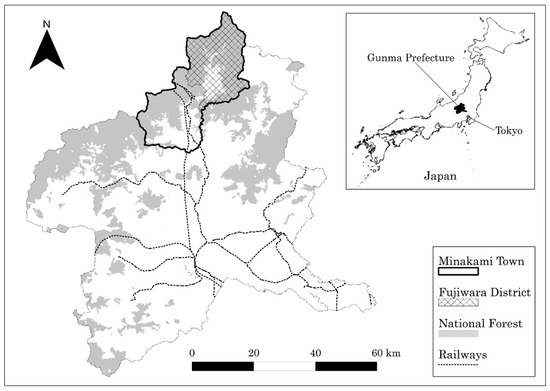

In this study, a case of forest recreation in Fujiwara District, located in Minakami Town, Gunma Prefecture, Kanto Region, Japan (Figure 1), will be discussed. Fujiwara District is located at a distance of approximately 150 km from Tokyo and is situated in a mountainous area that contains extensive forests and that receives heavy snowfall in winter. Natural resource management in this district is conducted through collaboration between a nonprofit organization named Forest College Seisui (FCS; “Shinrin Jyuku Seisui” in Japanese) and locals. FCS is primarily composed of urban residents who live in the Tokyo metropolitan area and local youths. About 10 core members of FCS plan forest recreation and call on the general participants to join activities. This study focuses on this case because their activities address the modern issue of regenerating underused natural resources, and a previous study [10] clarified the details of governance of natural resource management.

Figure 1.

Map showing Fujiwara District in Minakami Town, Gunma Prefecture, Kanto Region, Japan (extracted from [10]).

2.1.2. The Place of Activities

FCS conducts various activities on Uenohara in Fujiwara District, which consists of an 11.8 ha forest dominated by Quercus crispula and a 9.7 ha grassland dominated by Miscanthus sinensis (total of 21.5 ha) (Figure 2). This district had grasslands of over 300 ha, which were used to provide residents with necessities, such as roofs, organic fertilizer, forage, and food as common pool resources. However, most were abandoned due to the modernization of lifestyles and the spread of chemical fertilizers after the 1960s; they were sold to a major developer for use as a resort site, including a hotel, skiing grounds, and a golf course. Uenohara was an unsold land because of its unsuitability for resort development. The owner of the unsold land, Minakami Town Office, was anxious for effective usage of Uenohara. Therefore, FCS signed a land lease agreement for Uenohara and began managing forests and grasslands for recreation in 2003.

Figure 2.

Image showing Uenohara. These pictures were taken in 2015.

2.1.3. Contents of Activities

Table 2 shows the annual schedule and participation scale of recreational activities held by FCS. Among the various events concerning forest and grassland management in Uenohara (Figure 3), control burning (referred to as “Noyaki” in Japanese) in spring and thatch cropping (referred to as “Kayakari” in Japanese) in autumn are particularly attractive to participants.

Table 2.

Activities of Forest College Seisui in 2017.

Figure 3.

Image showing activities of FCS. These pictures were taken in 2015.

Grassland in the temperate humid climate of Japan is classified as “semi-natural grassland” and requires continuous management. Control burning deters weed invasion, which hinders Miscanthus sinensis growth. Control burning is a labor-saving, but dangerous, vegetation management method. Thatch cropping is harvesting grown Miscanthus sinensis as “Kaya” (regarded as plant resources used as roofing materials), and Kaya produced by FCS is sold to a construction company that preserves cultural properties. Although these activities have faded in Fujiwara District, forest recreation led by FCS regenerates them. However, FCS members have no experience in traditional resource management, so local elders have instructed them regarding these methods. FCS members are mainly led to activities due to the fun derived from recreation; social contributions through underused resources management are secondary motivation [10]. Nevertheless, the interaction between urban and rural residents is essential for mountain villages facing population decline.

2.2. Research Methodology

Considering that cultural services are derived from “human-ecological relations” as previously mentioned, understanding them in the context of forest recreation requires clarifying the participants’ impression on natural resources or recreational activities. Therefore, in this study, quantitative text analysis of participants’ essays appeared in FCS’s newsletters (titled “Kayakaze Tsūshin” in Japanese), made to structurally specify cultural services by forest recreation. These essays contain the experiences and impressions of participants in recreational activities; each issue of the newsletter has about five to ten articles. Quantitative text analysis can be defined as “a quantitative method of context analysis through organizing text data” [25] (p. 15). The data were analyzed using the free software KH Coder (https://khcoder.net/en/, Retrieved on 5 November 2021). Computer-based text analysis methods are classified into a correlational approach and a dictionary-based approach. The former means automatic word extraction from text data and statistically analyzing them while avoiding incorporation of researcher’s prejudices. This approach has the reproducibility of analysis results through automatic operation, has also been called “text mining” or “text analytics” [26,27]. Alternatively, the latter sets coding rules that assign a code corresponding to sentences, paragraphs, or articles in which specific words appear and statistically analyze concepts represented by each code. Through this approach, researchers can examine text data in any aspect based on their interests [27,28]. The KH Coder software can combine these two approaches, so both advantages can be exploited [25].

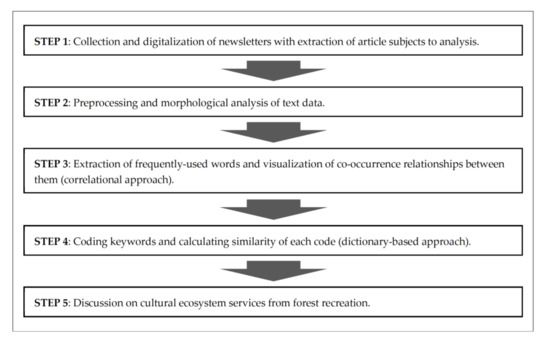

Figure 4 shows a flowchart of this research. STEP 1: FCS’s newsletters No. 4–61 published in 2003–2020 are collected and digitalized (No. 1–3 are unavailable). Then, participants’ essays referring to activities in Fujiwara District are extracted as subjects to analysis; the other articles, such as conference proceedings in Tokyo are exempted. The text analysis targets Japanese because essays use Japanese as the original language. However, morphemes from text data are translated into English with original words in parentheses for writing this paper. Names of individuals and hamlets are anonymized for information protection (e.g., first name A, last name B, hamlet name C). STEP 2: Compound words are added to the forced extraction list to avoid the word division during preprocessing. Then, the object words are counted through morphological analysis of the text data. STEP 3: Frequently used 150 words (appeared 86 times or more) are listed and co-occurrence relationships between them are visualized on a network diagram. This diagram is composed of the top 60 relationships that calculated the similarity between frequently used words in paragraph units using the Jaccard index. This visualization is operated by importing GraphML format data created by KH Coder into open-source software Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/, Retrieved on 5 November 2021). This step corresponds to the correlational approach described above. To enhance the comprehension of this diagram, similar words are classified into several groups while referring to categories of cultural services in Table 1. The grouping process is regarded as a bridge between this and subsequent steps. STEP 4: Several codes are added to keywords that characterize this case while referring to the diagram created in the previous step. Then, a similarity matrix between each code added to paragraph units is shown, explaining correlations between participants’ positive expressions and various factors. Additionally, a co-occurrence network composed of the top 30 relationships between each code is drawn in the same method as the previous step. This step corresponds to a dictionary-based approach described above. STEP 5: A structure of cultural ecosystem services (CES) brought by forest recreation is discussed.

Figure 4.

Flowchart showing the steps of this research.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Analysis of Text Data

As a result of sorting article subjects for analysis from 58 newsletters published across 18 years, 424 essays composed of 4388 paragraphs and 12,573 sentences were extracted. This paper exempts irrelevant words, such as postpositional particles or auxiliary verbs from 297,504 word tokens (16,664 word types) derived from morphological analysis, picking up 119,231 word tokens (15,014 word types) for subsequent text analysis.

3.2. Correlational Approach

Table 3 shows 150 frequently used words in the text data. This study focuses on essays describing the impressions of activities by participants; therefore, words, such as “participation” (sanka), “think” (omou), and “this time” (konkai) are ranked high. Words about specific activity contents (e.g., “work” (sagyou), “control burning” (noyaki), “thatch cropping” (kayakari)) or words about natural environment found in Uenohara (e.g., “snow” (yuki), “grassland” (sougen), or “mountain” (yama)) appear frequently.

Table 3.

Frequently used 150 words from newsletters.

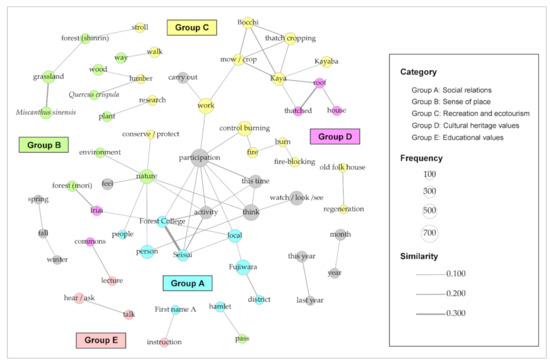

Figure 5 illustrates a co-occurrence network that describes correlations between frequently used words (appeared 86 times or more). This diagram is composed of nodes meaning each word, and edges meaning co-occurrence relations between each word. Node size is proportionate to words’ frequency; likewise, edge size is proportionate to similarity calculated by the Jaccard index. The absence of an edge does not necessarily mean no correlation between nodes because only the top 60 relationships are shown for clarity. Furthermore, the co-occurrence relation between words is indicated by the thickness of the edge and is not affected by the distance between each node.

Figure 5.

Diagram showing each word co-occurrence relation.

Several groups of words with similar properties are shown in Figure 5. Although the diagram itself is described through automatic operation, grouping (coloring) was performed based on the author’s decision for comprehension. In this process, classification was based on whether or not there was a corresponding category other than “recreation and ecotourism,” and if so, which one (Table 1). Group A concerns people, organizations, and regional communities. The words “Forest College” (Shinrin Jyuku) and “Seisui” (Seisui) are combined, indicating the organizer’s name. The co-occurrence relation between them and the word “local” (jimoto) shows that activities in Fujiwara District are practiced by collaboration between urban and rural residents. Group B concerns the natural environment observed in the place of activities. The words that express landscapes (e.g., “forest” (shinrin), “grassland” (sougen)) or vegetation (e.g., “Quercus crispula” (mizunara), “Miscanthus sinensis” (susuki)) are shown in addition to the general words, such as “nature” (shizen) and “environment” (kankyou). Group C concerns activity contents. Words about continuous activities appear, for instance, thatch cropping, control burning, and regeneration of old folk house. They have object–action relations with words of Group B (e.g., “nature” (shizen) and “conserve/protect” (mamoru), “wood” (ki) and “lumber” (bassai), “plant” (syokubutsu) and “research” (chousa)). Group D concerns local and traditional culture. Words associating traditional buildings with thatched roofs are described because Kaya produced through thatch cropping is mainly used for them. Further, the words “Iriai” (iriai) and “commons” (komonzu) are co-occurring with the words “forest” (mori), “Forest College” (Shinrin Jyuku), and “lecture” (kouza), respectively. Aforementioned, Uenohara, which had been used as local commons, was abandoned after the 1960s. These correlations mean that FCS regards natural resource management through recreational activities as commons regeneration. Group E concerns stakeholder communication. “First name A” refers to a local cooperating with FCS on forest maintenance instructions, thatch cropping, etc. The appearance of these words, including “instruction” (shidou) and “lecture” (kouza), suggests that locals provide various pieces of knowledge to FCS members.

3.3. Dictionary-Based Approach

Some factors included in the essays were illustrated in Figure 5 by interpretating the co-occurrence network created through an automatic operation. In this section, relations between these factors and participants’ positive expressions will be discussed to clarify a structure that provides cultural services.

Table 4 shows the coding rule on classification of words in text data. Each code is added to keywords that characterize the case in Fujiwara District while referring to Group A–E in Figure 5. To emphasize features of the activities, this rule is established by subdividing each group and contains factors that are generally considered vital in recreation (*Food and *Stay). Due to the difficulty of classifying all word types, these codes are added to words that appeared 50 times or more. The similarity matrix between each code is described in Table 5, as a result of paragraph units coding and Jaccard index calculation. Although this index has no criteria applicable to any document, numbers above 0.100 and 0.150 are highlighted in this study.

Table 4.

Coding rules for dictionary-based approach.

Table 5.

Similarity matrix between each code.

Firstly, the code * Positive is added to words that symbolize cultural services, such as “good” (yoi), “pleasant” (tanoshii), “beautiful” (utsukushii), and “wonderful” (subarashii). According to similarity calculations between this code and the others, relations with the codes * Party (0.142), * Local community (0.132), and * People (0.129) are close. These indicate human relationships between participants or locals. A relation with the code * Knowledge (0.125) derived from local people is relatively close. Regarding the natural environment in which activities are conducted, * Forest (0.119) shows a much higher percentage than * Grassland (0.063). Concerning the activities, a relation with the code * Work (0.130) denoting labor is more intimate than code connoting specific contents, such as *Thatch cropping (0.104) and * Control burning (0.097).

Next, focusing on the relations between codes other than * Positive, (1) * Work and * Thatch cropping (0.221), (2) * Forest and * Work (0.200), (3) * Party and * Local community (0.199), (4) * Local community and * Work (0.196), (5) * Local community and *Knowledge (0.180) had the highest values, respectively. Relations (1) and (2) show the feature of FCS’s activities of natural resource management through recreation. Relations (3)–(5) illustrate that these activities demand the imparting of some knowledge from locals to participants.

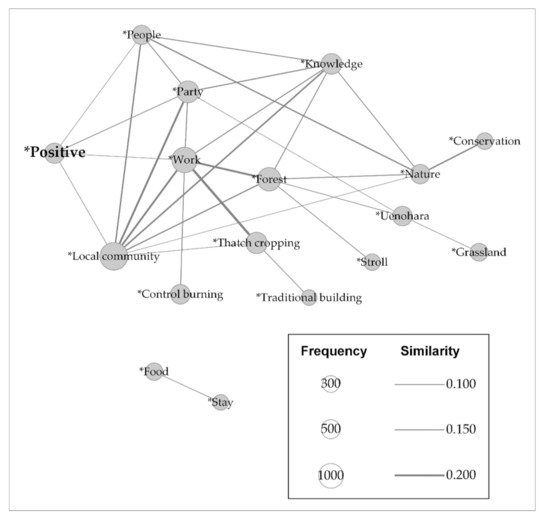

To enhance the comprehension of correlations between each code, a co-occurrence network diagram starting from the code * Positive is drawn in Figure 6. This figure depicts the following points: firstly, participants prefer working with comrades to nature conservation itself. The node * Positive is connected with * People, * Party, * Work, and * Local Community having no co-occurrence relation with nodes indicating specific activity contents or natural environments. Therefore, participants’ positive emotions are derived from interactions with people, not satisfaction in social contributions or nature experiences. Secondly, locals and their knowledge are vital in the case of the Fujiwara District. As several edges starting from * Local community or * Knowledge appear in Figure 6, these nodes function as the network hub. FCS’s activities, natural resource management through forests and grasslands maintenance, cannot lack these factors. Thirdly, general factors, such as * Food and * Stay are interrelated but less relevant to other codes. It shows that dietary and accommodation factors are less important in forest recreation.

Figure 6.

Diagram showing each code co-occurrence relation.

4. Discussion

The quantification of CES derived from forest recreation has been determined by the potential of what resources are and where they are [17,18]. Although they have some importance, resource type and its location are not the only factors that provide cultural services.

This study attempted to show a structure providing CES by performing quantitative text analysis of essays written by forest recreation participants. According to Table 5, which indicates similarities between factors composing text data, the code, * Positive, that is added to words that symbolize cultural services has strong connections between the codes such as * Party, * Local community, and * People that suggest social relations. We have illustrated each code co-occurrence relation as a network diagram in Figure 6, wherein a structure that shows participants’ positive emotions from ecosystems has been visualized.

In the case of Fujiwara District, participants’ positive emotions were not only about landscapes, such as forests and grasslands, plant species, such as Quercus crispula and Miscanthus sinensis, and activities, such as control burning and thatch cropping. They experienced emotions of “pleasant” (tanoshii) or “wonderful” (subarashii) toward field activities involving interactions with comrades and locals. This implies that CES are provided by social relationships or the communication of knowledge. Hence, simple quantification using easy-to-obtain data could be missing some social factors and underestimate cultural services. Not surprisingly, information about connections between people or their knowledge of using natural resources is not revealed in official statistics released by central and local governments. Importantly, inasmuch as it is derived from “human-ecological relations”, valid evaluation of culture services cannot be achieved without careful observation and comprehension of local societies. In this regard, Hirano (2019) claims that “functions” carried out by forests and “values” recognized by people should be distinguished, explaining the latter’s advantage in terms of its potential in indicating specific interactions between the subject (people) and object (forests) [30]. Furthermore, Shibasaki (2018; 2019) demonstrated that the designation of protected areas (e.g., World Natural Heritage site) emphasizes the importance of the natural environment itself and restricts the customs of the local communities such as traditional festivals or hunting [31,32]. Referring to the results of this study, restriction of local activities involving various social relations could invite the decline in cultural services, while protecting flora and fauna.

Additionally, the correlation between cultural and provisioning services should be clearly defined. A situation in which an increase in one ecosystem service leads to a decrease in another is described as a “trade-off.” Contrastingly, the enhancement of multiple services in relation to each other is called a “synergy” [33]. Because this case is based on participants’ interest in activities with the regeneration of Uenohara, their expectations are primarily directed toward cultural services. However, note that, thatch cropping, which is performed as a recreational activity, supplies Kaya to cultural properties; provisioning services are evident in the case of Fujiwara District. This shows that synergies between cultural and provisioning services are found in Uenohara, and social relationships or knowledge communication can influence recreation domains and other fields. In this regard, previous studies demonstrated that traditional cultures or customs include abundant knowledge of natural resource management [34,35].

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on forest recreation activities occurring in Fujiwara District located in Minakami Town, Gunma Prefecture, Kanto Region, Japan, and shows a structure providing CES through quantitative text analysis of essays by participants. The study targeted 15,014 word types included in 424 articles, and the 150 frequently used words are shown in Table 3. In addition, similarities between these words were calculated by the Jaccard index and visualized via a network diagram (Figure 5). Codes that subdivided factors appearing in this figure were established and added to words that appeared 50 times or more (Table 4). As a result of the calculation of similarities between each codes, the code, * Positive, that symbolize cultural services connects strongly to the codes that suggest social relations (Table 5). Figure 6 represents co-occurrence relations and structurally shows that there are factors, such as social relationships or knowledge communication, between ecosystems and services.

Although Hirahara (2020) has shown that social factors have vital roles in the new governance of natural resource management [10], this study illustrates each causal relationship from the cultural services perspective. However, one of the limitations of this study is that the subject of analysis is just one form of forest recreation in a certain area. Continuous studies on various cases in several landscapes would clarify what provides cultural services. Furthermore, these results should be integrated and reflected in the evaluation of CES during the policy-making process.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Newsletters used for text analysis in this study are available on the FCS website (http://commonf.net/wordpress/, Retrieved on 5 November 2021). All newsletters were written in Japanese.

Acknowledgments

I appreciate FCS members for their cooperation in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Nakashizuka, T. Shinrin no Henka to Seitaikei Sābisu [Forest Changes and Ecosystem Services]. In Shinrin no Henka to Jinrui [Changes in Forests in Relation to Human]; Nakashizuka, T., Kikuzawa, K., Eds.; Kyoritsu Syuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 211–244. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, D. Multi-level Natural Resources Governance Based on Local Community: A Case Study on Semi-Natural Grassland in Tarōji, Nara, Japan. Int. J. Commons 2015, 9, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, A. Smallscale European Forestry, an Anticommons? Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, C. The Traditional Commons of England and Wales in the Twenty–First Century: Meeting New and Old Challenges. Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 192–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y. What is Satoyama? Points for Discussion on its Future Direction. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 7, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts; Center for International Forestry Research: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the Concept of Payments for Environmental Services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, N.T.B.; De Groot, W.T. The Impact of Payment for Forest Environmental Services (PFES) on Community-Level Forest Management in Vietnam. Forest Policy Econ. 2020, 113, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aza, A.; Riccioli, F.; Di Iacovo, F. Optimising Payment for Environmental Services Schemes by Integrating Strategies: The Case of the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Forest Policy Econ. 2021, 125, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahara, S. Regeneration of Underused Natural Resources by Collaboration Between Urban and Rural Residents: A Case Study in Fujiwara District, Japan. Int. J. Commons 2020, 14, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystem and Human Well-Being: A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystem and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nakashizuka, T. Rikuiki no Seibutsu Tayousei to Seitaikei Sābisu [Biodiversity and Service of Terrestrial Ecosystems]. Nouson Keikaku Gakkaishi 2017, 36, 5–8. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. An Empirical Review of Cultural Ecosystem Service Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Biodiversity Outlook 2. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/biodic/jbo2.html (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Milcu, A.I.; Hanspach, J.; Abson, D.; Fischer, J. Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Literature Review and Prospects for Future Research. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paracchini, M.L.; Zulian, G.; Kopperoinen, L.; Maes, J.; Schägner, J.P.; Termansen, M.; Zandersen, M.; Perez-Soba, M.; Scholefield, P.A.; Bidoglio, G. Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Framework to Assess the Potential for Outdoor Recreation Across the EU. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richards, D.R.; Tunçer, B. Using Image Recognition to Automate Assessment of Cultural Ecosystem Services from Social Media Photographs. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEEB. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, C.; Larondelle, N. Going to the Woods Is Going Home: Recreational Benefits of a Larger Urban Forest Site—A Travel Cost Analysis for Berlin, Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Recreation–amenity Use and Contingent Valuation of Urban Greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landscape Urban. Plan. 2006, 75, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Klain, A.; Satterfield, T.; Basurto, X.; Bostrom, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Gould, R.; Halpern, B.S.; et al. Where are Cultural and Social in Ecosystem Services? A Framework for Constructive Engagement. BioScience 2012, 62, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascua, P.; McMillen, H.; Ticktin, T.; Vaughan, M.; Winter, K.B. Beyond Services: A Process and Framework to Incorporate Cultural, Genealogical, Place-Based, and Indigenous Relationships in Ecosystem Service Assessments. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Goldstein, J.; Satterfield, T.; Hannahs, N.; Kikiloi, K.; Naidoo, R.; Vadeboncoeur, N.; Woodside, U. Cultural Services and Non-use Values. In Natural Capital: Theory and Practice of Mapping Ecosystem Services; Kareiva, P., Tallis, H., Ricketts, T.H., Daily, G.C., Polasky, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 206–228. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, K. Syakai-chousa no Tame no Keiryou Tekisuto Bunseki [Quantitative Text Analysis for Social Researchers], 2nd ed.; Nakanishiya Syuppan: Kyoto, Japan, 2020. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Iker, H.P.; Harway, N.I. A Computer Systems Approach Toward the Recognition and Analysis of Content. In The Analysis of Communication Content: Developments in Scientific Theories and Computer Techniques; Gerbner, G.A., Holsti, O.R., Krippendorff, K., Paisly, W.J., Stone, P.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 381–486. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, K. A Two-Step Approach to Quantitative Content Analysis: KH Coder Tutorial using Anne of Green Gables (Part I). Ritsumeikan Soc. Sci. Rev. 2016, 52, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tennenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, U.; Balooni, K.; Inoue, M. Effect of Instituting “Authorized Neighborhood Associations” on Communal (Iriai) Forest Ownership in Japan. Soc. Natur. Resour. 2009, 22, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, Y. Aratana Shinrin Riyou no Chouryuu to Bunkateki Kachi no Sousei: Shinrin wo Meguru Kachi Kenkyuu Jyoron [New Trends in Forest Use and the Birth of Cultural Values in Human-Forest Relationships: An Introduction to Value Studies in Forestry]. Ringyou Keizai Kenkyuu 2019, 65, 27–38, (In Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki, S. Yakushima Island: Landscape History, World Heritage Designation, and Conservation Status for Local Society. In Natural Heritage of Japan: Geological, Geomorphological, and Ecological Aspects; Chakraborty, A., Mokudai, K., Cooper, M., Watanabe, M., Chakraborty, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, S. Hogo Chiiki wo Katsuyoushita Chiiki Shinkou ya Sanson Bunka Hozen no Kanousei [Possibility of Regional Development and Mountain Village Cultural Conservation of Utilizing Protected Areas]. In Shinrin to Bunka: Mori to Tomoni Ikiru Minzokuchi no Yukue [Forest and Human Culture: The Future of Folk Knowledge in Changing Human-Forest Interactions]; Ebihara, I., Saitou, H., Ubukata, S., Eds.; Kyoritsu Syuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 233–258. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, E.M.; Peterson, G.D.; Gordon, L.J. Understanding Relationships Among Multiple Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Mitsumata, G. Bidding Customs and Habitat Improvement for Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake) in Japan. Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).