Abstract

Today, a forest is also understood as a real social actor with multiple-scale influences, capable of significantly conditioning the social, economic, and cultural system of a whole territory. The aim of this paper is to reconstruct and interpret the population’s perception of the silvicultural activities related to traditional use of forest resources of the southwestern Sardinian Marganai State Forest. The “Marganai case” has brought to the attention of the mass media the role of this forest and its silviculture. The research was carried out via semi-structured interviews with the main stakeholders in the area. The qualitative approach in the collection and analysis of the information gathered has allowed us to reconstruct the historical-cultural and social cohesion function that the forest plays in rural communities. The results highlight that the main risks concern the erosion of the cultural forest heritage due to the abandonment of the rural dimension (mainly by the new generations, but not only), with the consequent spread of deep distortions in the perception, interpretation, and necessity of forestry activities and policy.

1. Introduction

The social component plays a fundamental role in the forestry sector. Some authors say that the social component is determined by those “who in a certain place and at a certain time have the right to decide the land use” [1]. At the same time, the forest policy process implies several interests. Public, private, and non-profit associations can influence forest policy today [2].

The forest planner cannot limit himself to applying technical knowledge based on the stationary characteristics of the forest in which he/she operates but must carefully analyze the socio-economic aspects that link the forest to the community. Today, the participatory approach is a recognized tool in public forestry management in Europe and North America [3]. However, it is not always applied with the right weight by forestry technicians and is often limited to a few public meetings and only at the information level.

The analysis of the perception of forestry issued by the community is an abundantly developed topic in this field of research [4,5,6] but the collected information is not always integrated into the planning processes. Furthermore, the participatory process can be adversely affected by difficulty in communication. The scientific sector often uses complex messages, which are not always attractive, and this can cause problems in communicating with the community. This difficulty, already presenting itself at the lowest level of involvement, can influence the whole process between planners and communities. A further problem is given by the widespread loss of historical memory, particularly evident in forest management. A striking example is given by the coppice silvicultural system. Coppice has been used for several centuries in the Mediterranean woods [7]. Although it has remote origins, the greater diffusion of the coppice system in Italy coincided with the population increase and the industrialization of the 19th century. In this historical period, coppice was connected to different wood assortments. The main products were firewood, coal, and sleepers, used in the construction of the Italian railway network. In the past, coppice has been associated with many uncontrolled practices in forests, such as grazing and agriculture. This association produced a strong environmental impact, building up the negative perception of the coppice system handed down to today, calling it “robbery forestry” [8,9].

The widespread interest in socio-environmental issues requires a new approach. Forest management has become particularly complex, as it must propose solutions capable of supporting socio-ecological systems. At the same time, new economic potentials are emerging: the correct management of forests should respond to new market needs [10]. In this perspective, collaborative activities between researchers in the sector, resource managers, and policy makers could generate interesting shared management strategies where the coppice management would take on an important role [11].

Today in Italy, the coppice woods are still widespread [12] and most of the coppice stands have reached or even exceeded twice the rotation age. Nevertheless, the recent proposal to re-introduce small-scale coppice management in the Marganai area has given rise to a heated debate at the regional and national level [13]. The influence of the media, due to the extreme synthesis the new media require and to some journalistic exaggerations, has led to a debate with actually no scientific grounds. The authority’s intervention has led to the limitation of silvicultural operations in Sardinia as well as in other regions. A conflict between forest, forestry, and the landscape emerged. From a regional case, the forestry policy has been influenced up to the national scale.

An increasing number of research projects highlight an approach even more influenced by social sciences with respect to forest planning and management. References [14,15] have shown that the socio-cultural elements supporting the decision-making processes increase the socio-economic–environmental sustainability of the management interventions and reduce social conflicts. However, sociological research in forestry usually apply a quantitative approach that, through highly standardized techniques, aims to detect the incidence of pre-determined indicators. This approach detects static data that does not allow the emergence of new information, extraneous to those foreseen by the indicators identified ex ante. This scenario generates reliable results but does not capture innovative elements. The adoption of a rigorous qualitative approach for the socio-economic surveys concerning forest contexts can contribute significantly to improving the political and operational choices regarding land management [16].

The aim of this work is to study the contradictions of the perceived conflict between forests and forestry, through the perceptions within the local rural community, of the role of the forest and its management. A qualitative approach in this context is essential: the aim is to let those contradictions emerge, not to verify a priori hypothesis concerning the heart of the problem. Not relying on a random sample and being limited to relatively few interviews implies taking the burden of the responsibility, which we acknowledge.

To provide readers with a more detailed framework of this study case, in the next chapter we will introduce a brief history of the Marganai State Forest from the 19th century to the time that generated the case.

1.1. Context: Study Area and Forest Management from the 1850s to the Present

Marganai State Forest is located in the south-western part of Sardinia (Italy) and extends in a single body of about 3650 hectares on the Linas mountain massif (Figure 1). It is mainly located in the municipality of Domusnovas (with more than 6000 inhabitants). Smaller portions fall in other municipalities: Iglesias (more than 26,000 inhabitants) and Fluminimaggiore (about 3000 inhabitants). These municipalities occupy an area of 2324 km2. The northern side of the Marganai forest, about 450 ha, is included in the Natura 2000 network as a Site of Community Interest (SCI), “Monte Linas-Marganai ITB 041111”. In 1979, the Marganai forest was bought by the Italian government. Today it is managed by the Agenzia Fo.Re.S.T.A.S. (Forest Agency of the Sardinia Region).

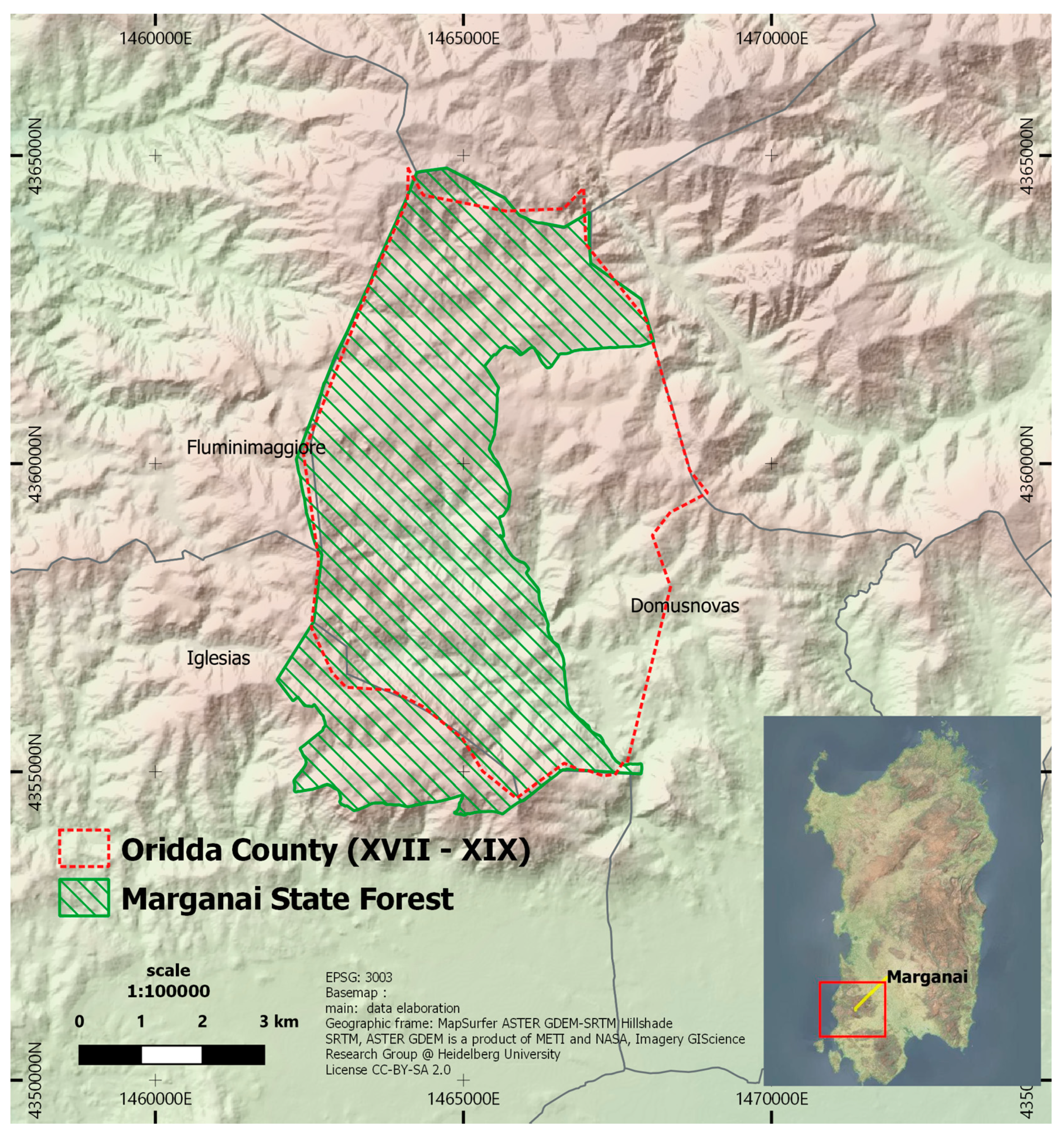

Figure 1.

Geographical framework of the Marganai State Forest. Basemap: MapSurfer ASTER GDEM-SRTM Hillshade, a METI and NASA product, Imagery GIScience (License CC-BY-SA 2.0). The Oridda County border was processed from Real Corpo, 1842, Serie Mappe, Archives of State, Cagliari, Italy. Digitization by Techso SPA, 1999.

1.1.1. The 19th and 20th Centuries

Historically, the Marganai State Forest overlaps with the forested area that in the 19th century was known as Oridda County (Figure 1). The story of this area is representative for the wide mining area of Sardinia called “Sulcis-Iglesiente”. Oridda County became government property after the law of 1835 and was granted almost entirely to the municipality of Domusnovas. After the abolition of the fiefdoms, some of the woods were sold through private negotiations. In 1857, Oridda was sold to Count Beltrami. The count, a businessman and seller of timber, bought Oridda County in 1857 and was the first to use the forest for production purposes at an industrial level. In 1864 he sold the property to a mining company interested in the exploitation of the subsoil. The ownership passed to several mining companies, including the Scarzella family business, which held it for 55 years, from 1896 to 1951. Furthermore, in 1856, the firm John Taylor & Sons, seated in London, floated a company to pursue mining interest in these “celebrated” lead mines. The mining activity also resulted in the intensive exploitation of the forest’s resources [17]. The intense production of coal has continued for about a century and continued until 1970. The structure of the forest and the dense network of mule tracks and charcoal burner’s posts (Figure 2) bear witness to this silvicultural history.

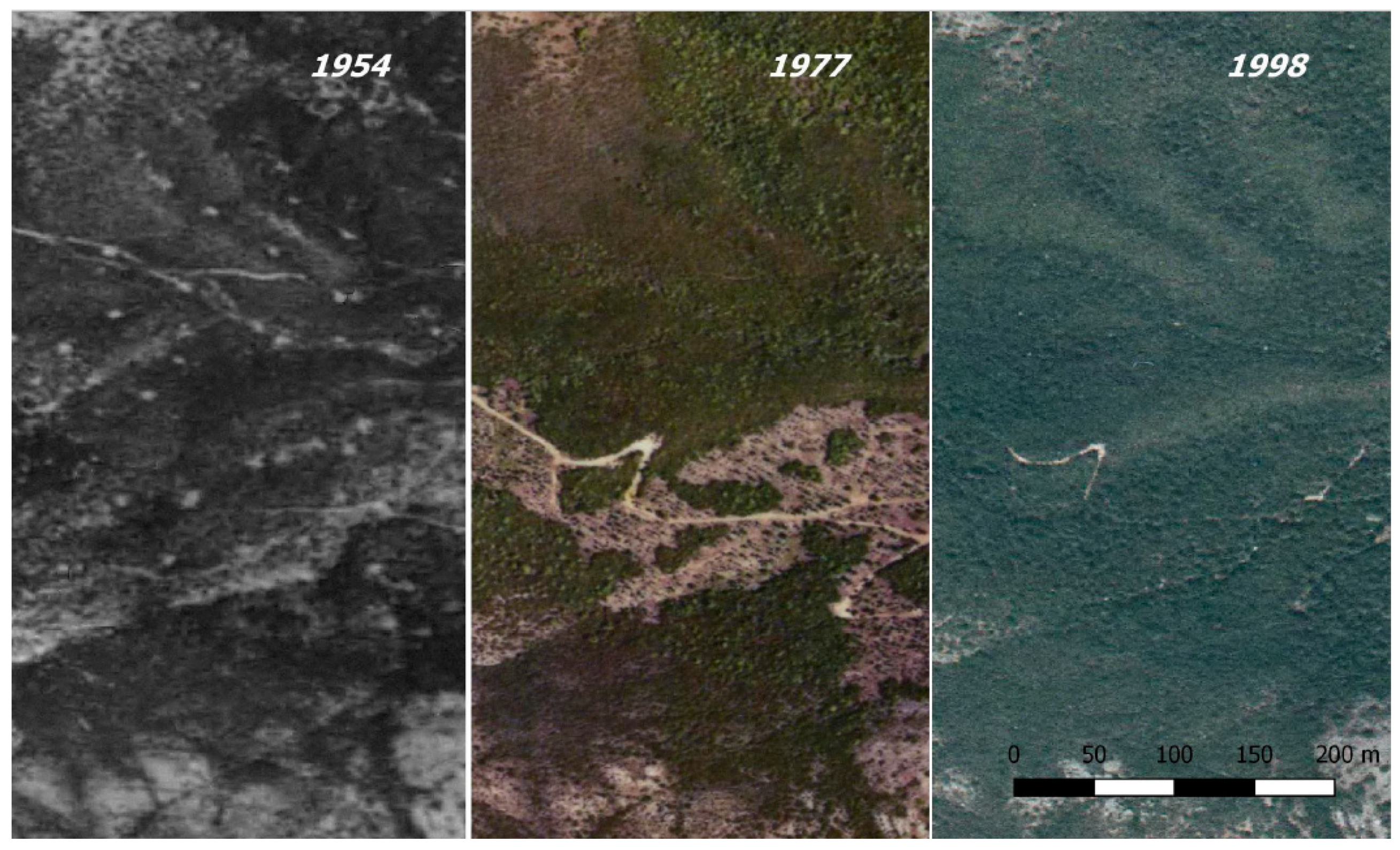

Figure 2.

Sequence of images representative of the change in forest management, starting from the intense use in the post-war period to the present day. Mining activities and coal production shaped the landscape of this region and coppice wood dominated the management of this territory since the 19th century, in order to provide coal and lumber for industry, mines, and population. From the photo taken in 1954, it is possible to view the coal areas scattered throughout the territory. In 1977, coppice-with-standards areas at different stages of evolution are evident. Photos with permission from Sardinia Region.

In the last decades of the 20th century, the Marganai State Forest has been managed with a conservation approach, due to the abandonment of rural areas and the decline in demand for charcoal. Some parts of the forest have been thinned, aiming towards the conversion to high forest, while others have been left to natural evolution. Coal production is only a memory of the past and the production of firewood in the area is now limited to very small private properties.

1.1.2. The 21st Century

The Marganai forest has been left mainly to natural evolution (no silvicultural operations) from the 1980s to today, resulting in holm oak coppice of 40 to 50 years old. In 2010, with the double aim of recovering the 150-year-old historical silvicultural practices and to favor a local, sustainable forest chain for firewood, the Forest Agency implemented a management plan for a small portion of the Marganai forest’s surface, less than 600 ha. Of this area, 354 ha were allocated to the reactivation of the traditional coppicing system [18].

The present case study has developed from a series of key events. Two other important planning processes initiated short after the 2010 forest management had started. The Marganai forest was included in a larger operation: the drafting of a forest management plan for the 13 state-owned forests in Sardinia [19,20]. Beside this, the renewal of the SCI management plan “Monte Linas-Marganai ITB 041111”.

The larger planning operation activated interesting participatory processes for each forest. The first meeting for the Marganai forest was held in 2011, carrying out the information phase and presenting the planning project already underway.

The second meetings took place in 2013 and saw a moment of exchange between the local population, forest users, and planners. The interesting aspect is that the importance of the recreational and touristic function and that of the productive enhancement of the forest emerged in this context, as opportunities to revive the local economy and to meet the needs of the local market. The communities explicitly raised a request for firewood. The planners responded, identifying productive areas suited for the reactivation of the coppice system (personal communication).

In the same period, the professionals involved in the renewal of the plan for the Margani SCI expressed very strong concerns about the activation of coppice practices in the Marganai area [21]. During the participatory meeting, held in the Iglesias area in 2014, the professionals denounced the high risk of erosive phenomena triggered by such silvicultural operations [22]. However, Giadrossich et al. questioned the hypothesis of such risks in the Marganai forest [23].

The case has been amplified in the media and moved from local to national newspapers [13,23]. The media, following the criticisms highlighted by the professionals, further amplified the case, publishing titles and phrases like “The prehistoric forest that becomes firewood”, “disastrous environmental consequences”, and “deforestation of Marganai forest”, just to mention a few.

The impact on the media has influenced local and national forest policies. The landscape superintendent at the regional level, pressured by the information disseminated by the media, investigated the case, and finally blocked the silvicultural works, launching a legal quibble. The planned developed of the identified productive area has been submitted to the authorities in accordance with the regulations in force for the Marganai forest. The interpretation of the legislation did not help the case and the length of the bureaucracy did not allow it to be resolved. Besides being marginally interested by a SCI, the whole forest is actually under a double bound (according to the following Italian laws: Legge 29 June 1939, n. 1497, “Protezione delle bellezze naturali”, published in the G.U. n. 241 in the 14/10/1939; and D. Lgs. 22 Juanary 2004, n. 42, “Codice dei Beni culturali e del Paesaggio”, published in the G.U. n. 45 in the 24/02/2004, s.o. n. 28). The procedures required for authorization are not straightforward. As some environmentalists raised the case with the administrative authorities, local operations have been blocked, waiting for clarifications. Moreover, the silvicultural operations in all the other coppice systems in Sardinia (and also in other regions) have been severely limited. The difficulty in interpreting the legislation has caused a blockage of the sector, stopping proposals for new forest management plans. All the people responsible for the planning process and the implementation of the Marganai silvicultural works have been reported.

The stop has also had economic consequences on the local and larger population. For the implementation of the silvicultural operations, the Forestas Agency had issued a call for a tender [24]. The contract was awarded to a company in the neighboring town of Domusnovas. The silvicultural operations started in 2010 but were halted by the authorities in 2014. The forestry company was sued. People lost jobs and the company lost the possibility of recovering its economic investment finally heading to its failure and to the closure of the company.

The “Marganai case” is still remembered by the Italian scientific community as an example of distorted information spread by the media and of conflicts both between forest perception and forestry and between effective legal competences and legislation interpretation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

We used the semi-structured interview as a detection tool. The interview, intended as a scientific tool for information collection, i.e., a conversation with a specific purpose, is the main tool in social research, providing reliable and comparable qualitative data [25,26]. Specifically, we used a qualitative approach that is characterized by the use of non-standardized procedures (or with a low level of standardization) for the collection of information on a limited number of cases taken as “typical and significant” [27]. This approach leaves an important margin of autonomy to the witnesses interviewed to expose their vision; it facilitates the emergence of unpredictable elements in the eyes of researchers, who are unrelated to the local communities and dynamics. The testimony collected through an interview is a representation of facts and personal experiences, interpreted and presented according to the point of view of a witness. Therefore, it is an unarguable—it cannot be considered “right or wrong”.

The interview outline is divided into sub-topics to make possible an overview of the more specific investigative elements to be looked at in-depth during the information-gathering phase. The outline of the interview is the boundary that defines the scope of the investigation and the topics that must be addressed. It is a compass that allows the interviewer to follow the flow of thoughts of the witness, catching the unexpected but useful information, enhancing the originality, and “conducting the conversation” in accordance with the purpose set for the research [28]. The questions and insights are proposed to the witness, following the path of his thoughts, and stimulating the emergence of information, memories, personal opinions, and feelings [29]. In this research, the interview outline has been built around four macro dimensions, for each of which a set of sub-topics has been defined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outline of the interviews.

2.2. Research Sample

The research sample consisted of an audience of 23 stakeholders (Table 2) defined as “qualified witnesses” [30]. This term indicates people who hold information on the topics useful for research purposes. In a qualitative approach the researcher carefully selects the witnesses based on their personal characteristics and on the skills/knowledge they hold [31]. The qualified witnesses are selected with a non-probabilistic procedure (reasonably chosen, [32,33]). This is justified by the fact that the personal characteristics of the witnesses significantly determine the success of the survey in terms of the quality, variety, and reliability of the information collected, decisively influencing the pursuit of the cognitive objectives of the research [34,35].

Table 2.

Composition of the research sample.

2.3. Interview’s Analysis

Following the most common qualitative analysis methodology, the 23 semi-structured interviews were transcribed and analyzed through the identification of “meaning strings” (interviews phrases) obtained through the interpretative capacity of the researcher. Through analysis of the interview, we detected situations, behaviors, attitudes, and opinions, which are the result of the witness’s personal vision of the reality under investigation [36]. The methodology led to the creation of interviews with very different contents, expressing what each witness deemed appropriate to communicate. The breakdown of the interview tracks into sub-topics (Table 1) and sub-dimension made up the storytelling of the interview, even if with different and original shapes, which are determined by the age, the skills, and the propensity to speak in front of a stranger. We highlighted significant witnesses’ phrases that support homogeneous information categories (H.I.) and used these categories as a path for the discussion. The final product of the analysis consists of a series of coded information useful for teasing out the vision of the world of each witness.

To protect the privacy of the witnesses, the interview extracts were reported anonymously through the assignment of a progressive alphanumeric code randomly distributed (witnesses from W-01 to W-23). Each respondent has signed a release to the processing of personal data and the use of the testimony collected [37]. Interviews were carried out from June to September 2018.

3. Results and Discussion

The analysis of the interviews has produced an archive of information, rich in suggestions and useful for explaining the meaning of the communities’ social action and for reconstructing and defining the role of the Marganai forest as a social actor capable of coexisting, in a symbiotic way, with the socio-economic system [38]. The relationship among the environmental, cultural, and economic components creates socio-cultural dynamics whose repercussions are considered far more important and significant than the value attributed to each single component of the relationship [39,40]. In fact, collected testimonies constantly show the awareness of living within a “community dimension” that embraces environmental, cultural, socio-economic, and historical elements. Results highlighted the presence of some central and recurring themes, summarized in the perspectives of the analysis and argumentation:

- Historical and identity function of the forest.

- Intergenerational cultural erosion.

- Socio-economic dimension of forestry.

- Perception of silvicultural activities.

In the following sections we discuss each of these four recurring themes, crossing all testimonies.

3.1. Historical and Identity Function of the Forest

The first element that unites the testimonies concerns the identity function of the Marganai forest for the local populations. Table 3 shows the homogeneous information collected during the investigation, which has clearly revealed the existence of this link and the important role that the forest plays in the community path of collective identity construction (Table 3). Over the centuries, the Marganai forest has played a central role in the history of local communities: from Roman domination until just a few decades ago the documented mining activities that led to the exploitation of other environmental resources, thereby influencing the local economy [9,17]. The presence of the forest of Marganai, both as economic and ecosystem agent, has inevitably conditioned the lifestyles and wellbeing of the population, determining the main features of the community identity. Within this social-cultural-environmental triangle, nature (the “non-human” element) has met the cultural dimension (social product through which man organized the material world) and the economy (social institution at the base of the social order) [41]. The interweaving of these factors is the result of a complex set of social relations, historical events, and socio-economic dynamics that have involved both the Marganai forest and the local populations. The link between the rural populations and territory is characterized by a sense of belonging that has a cultural base made up of a system of values and symbols linked to the land, the soil, and the territory [42,43].

Table 3.

Examples of homogeneous information (H.I.) about the dimensional analysis of the historical and identity functions of the forest.

Interviews also describe the importance of the Marganai forest intended as a “social actor” (Table 3), socially and historically significant in the processes of the local communities’ socialization to rural life (see also [44,45]). It is possible to re-define the symbolic, cultural, and social function of the Marganai forest thanks to the interpretative transition of the same forest from a “landscape element” to “social actor”. This change in social function (from ecosystem to social actor) tends to define the forest as an active subject in the community that can condition social dynamics [46]. According to the interviewees’ point of view, the environmental and ecosystem context exists and takes shape through the realization of a process of cultural interpretation that influences the perception of the forest for people who experience and give it symbolic meaning (see also [4,47]). The witnesses agree on the central role of the Marganai forest in relation to the processes of defining the community identity: the local population and urban population benefit differently from the resources of the forest system (Table 3). Rural communities perceive the natural environment as an element characterizing the cultural identity, while the urban population perceives more a tourist–recreational (aesthetic) value, based on a conservative attitude. The “culture of silviculture” is linked to a “tacit knowledge” transmitted from generation to generation through implicit and traditional education paths. This culture is not the result of conscious learning or ideological imposition, but is acquired through practice [48]. The community path of transmission of these operational skills originates in a “practical sense” that is realized not through educational pathways but thanks to a practical, daily operational experience in which words assume a residual relevance: the “know-how” prevails over the “knowing that” [49,50]. It is a symbiotic path of accompaniment to the direct and personal discovery of the “know-how” that is realized within the rural communities and it is in sync with the natural environment. Times and places become variables that determine the success of the transmission/transposition of knowledge. To guarantee the transfer of technical and cultural skills, a constant relationship (over a long timeframe) between the rural and ecosystem dimension is necessary [51].

3.2. Intergenerational Cultural Erosion

The presence of some central elements in contemporary society is beginning to emerge clearly through the interview’s analysis: history, culture, environment, and economy form a scenario in which divergent visions and interpretations are defined [40,52].

This is the case of the progressive loss of skills and knowledge related to the cultivation and management of the forest. Local communities have always lived in close relationship with the forest, but the changing needs (Table 4) of the communities have modified the dynamics of exploitation and cultivation of the natural environment. Today, we might say that different ecosystem services emerge. It all began with the spread of the urbanization process that consisted of the abandonment of the countryside, of rural centers, and of the outskirts in favor of the cities [53,54]. This phenomenon occurred during the first years of the twentieth century but showed a significant acceleration after World War II. Whereas in 1950, the inhabitants of the cities numbered only 29.6% of the world population; by the year 2000 the percentage had risen to 47%. In 2007, for the first time in human history, the urban population surpassed that of the countryside. Furthermore, the statistical projections indicate that in 2050 the urbanized urban population will be equal to 69% [55]. The progressive depopulation of rural areas is a phenomenon that in Sardinia significantly affects the entire regional territory, to the advantage of the main urban centers of the island. Specifically, the three municipalities in which this research was carried out show an average early decrease in population of 5.1% in the period 2001–2017. A significant trend that also has negative repercussions on the economic and labor market dimensions. Consequently, relations with abandoned rural areas are no longer defined and no longer perceived as elements capable of conditioning social and economic life [56,57]. The forest, therefore, becomes a place away from the daily socio-economic dynamics. Over time, the forest assumes the characteristics of a natural space useful for recreational activities. There would seem to be an intergenerational rift between old generations, who have experienced the forest as a part of their life experience, and new generations, urbanized, and therefore not socialized to the dynamics and knowledge typical of the rural context. The consequence is the progressive disappearance of the intangible memory of practical and traditional knowledge. This is a cultural capital that has always allowed rural populations to interpret natural dynamics and interact harmoniously with the cycles of the forest [58,59]. The reason lies in the fact that the recipients of this process of socialization to rural life no longer inhabit those places. The new generations are for the most part urbanized. Even those who still live in rural areas are culturally urbanized; that is, they are included in socio-cultural subsystems distant from the dimension of values and knowledge on which the symbiotic coexistence is based between the local communities and Marganai forest [60].

Table 4.

Examples of homogeneous information (H.I.) about the intergenerational cultural erosion.

The greatest expression of this inter-generational fracture (Table 4) is the loss of the so-called instrumental skills (linked to the cultivation and culture of the forest) and the consequent interpretative distortion of the role and functions of “nature” in the eyes of “citizens”. According to witnesses, the main problem concerns the loss of rural and forest culture that led to the inevitable “abandonment of the forest”, both from a cultural point of view and from a political/administrative perspective. The “rural and forest culture”, typical of the old generations, played an essential role in interpreting and better understanding the balance between the needs of local populations and the sustainability of the system in environmental and economic terms. The various forms of forest resource use are also affected by this decision-making process. Sometimes, however, the socio-economic system is not able to enhance the uses and values of the forest, indicated by our witness as “forest dynamics”, linked not only to the exploitation of naturally occurring resources but also to agriculture and breeding [61].

When the socialization of the new generations to these cultural elements has ceased, the interpretative perspective on the role and function of natural environments has changed in favor of an urban-centric perspective. The term “Taliban” is often collocated with that of “environmentalist” (Table 4). The meaning tends to highlight the radicalization of environmentalist thought, disconnected from the constraints and opportunities of everyday social life. With this expression, our witnesses wanted to underline the dangerousness of anachronistic attitudes towards a nature that is interpreted as “virgin” or falsely defined “millenarian”. This is the result of the interruption of the process of regeneration of the rural culture that led to the modification of the vision of the natural environment as “someplace that is at the disposal of the city”, a vision founded on the idea that nature regulates itself and man must never intervene or interfere. This perspective originates in a post-industrial context according to which the natural environment is interpreted and experienced as a resource to be exploited without any limit, in favor of a de-regulated economic–industrial development [62]. Despite this, the witnesses say that the new generations are not able to recognize the important role of the Marganai forest and the strong interconnection that this has with the daily life of local populations (not only ecological but also socio-economic).

This vision tends to ignore all the silviculture activities that man has historically put into practice and transforms a culturally rooted instrumental competence into a practice of environmental devastation. The abandonment of the rural world led to the “loss of cultural capital” (Table 4) and loss of tacit knowledge, useful for balanced cohabitation with the surrounding natural environment. Furthermore, it has produced a generation of environmentalists who live in sociocultural dynamics and contexts far from the physical place where their ideological vision of nature takes shape, with subsequent obvious distortions. The urbanization of large masses of population has certainly contributed to the construction of a romantic vision of natural environments and of the idea that tree cutting is always wrong. An excessive radicalization of this thought could, however, lead to a conservative perspective, to the detriment of a more balanced forest management capable of considering the multiple values and uses of the forest [14]. In this debate, forestry plays a central role as a concrete expression of the instrumental and traditional skills handed down in the rural communities.

3.3. Socio-Economic Dimension of Forestry

According to the words of our witnesses, silviculture and, in particular, the coppice system are “millennial activities” practiced since the “dawn of time” with the aim of “cultivating the forest” to put it “in condition to grow and to live better”: the coppice activities guarantee sustainability and increase natural renewal processes, contributing to the protection of local biodiversity and enhancing the multifunctional dimension of the ecosystem services of socio-economic interest [63,64,65].

Coppicing is commonly considered a traditional form of forest management, widely practiced in Europe and particularly in Italy at least since the Etruscan-Roman period [7,66]. The practice of coppicing is based on the ability of some species of trees to regenerate promptly, starting from their stock after cutting; this is an extremely simple principle that, based on a deep knowledge of the regenerative capacity and “resilience of the forest” (Table 5), has allowed, over the centuries, to exploit the forest resources in a balanced fashion [1,67]. The coppice has guaranteed to the local communities the regeneration of forest raw materials, i.e., firewood and timber, necessary for the subsistence of the population, both for the daily needs and for the local socio-economic system [68]. However, forest management has long been oriented toward maximizing the returns of a limited set of outputs.

Table 5.

Examples of homogeneous information (H.I.) about the socio-economic dimension of forestry.

On the other hand, the last decades have seen the spread of a romantic and symbolic view of the forest, not only because there has been an increase in sensitivity to environmental protection. As mentioned, this is due to the intensification of the urbanization phenomenon that has contributed significantly to the dispersion of the rural cultural heritage founded also on the knowledge of the ecological dynamics of the forest environments. The generational fracture that has characterized recent history has inevitably affected the relationship between time and places, compromising the socializing process and limiting the spread of traditional cultural elements. The critical issues to which we refer have particularly affected the instrumental skills related to the practice of coppicing. The recent generational fracture has led to the reduction of cultural competencies related to the management of forest resources. Public opinion was divided between those who continue to inhabit the rural area and those who base their vision of the forest on ideological elements, ignoring the symbolic and practical values that characterize the deep relationship between man and nature. The distance between these two positions is even more evident if the focus is on the coppice. In this case, the possession or absence of the instrumental skills related to the forest dimension make clear the attitudes for and against the cuts (Table 5) among the local populations.

Silviculture, and coppicing in particular, is based on the elaboration of traditional instrumental skills (linked to the rural dimension) within scientific paradigms widely recognized as valid. However, public opinion is still deeply divided on this issue, with consequent ideological conflicts that negatively influence the already precarious equilibrium that binds man to the natural environment.

3.4. Perception of Silvicultural Activities

What is now denounced as “violence against the forest” (Table 6), in the past was interpreted as a symbiotic activity between man and nature. The set of activities concerning the care and cultivation of the forest are considered one of the most important forms of “culture” for the rural communities because of the close interdependence link between them and the forest environment. In fact, rural communities have always drawn food and energy resources from forestry activities. At the same time, the cultivation of the forest guarantees its vigor and wellbeing, making it flourish and thrive [69,70]. However, the intertwining of social phenomena, such as “generational fracture”, “urbanization of the population”, and “depletion of rural cultural heritage”, has progressively influenced the dissemination of information on forest activities. With the lack of socialization paths in the community, the transfer of cultural skills is now achieved through the Internet and social networks [71]. Public opinion is constructed starting from that portion of the population most interested in particular themes, which interacts with the flows of information transfer and which determines the orientation of information contents in ideological terms [72]. The spread of hostile positions and prejudices about forest activities would, therefore, seem to be the result of a “communicative action” of this type [73]. The social communication processes have thus led the population to form a “public opinion” (Table 6) divided into two fronts: on the one hand, that based on technical information and favorable to a traditional use of forest resources; on the other, a public opinion influenced by social networks, which convey information associated with the devastation and indiscriminate exploitation of the natural environment.

Table 6.

Homogeneous information (H.I.) about the perception of silvicultural activities.

From testimonies emerge the opposing positions to the practices of silviculture. They are the result of the synergistic intertwining of trends with different characteristics. Some of these are related to the lack of knowledge that witnesses have of forest life, a dimension perceived solely for recreational purposes. Other testimonies would seem to be deeply influenced and conditioned by the specific communication dynamics that orient the communication flows (Table 6) towards ideological tendencies contrary to silviculture. Public opinion is oriented towards an interpretation of forest management activities as harmful for the balance of ecosystem services and environmental regulation (climate, water, natural disasters, pollination, and infestations) [74].

The information about silvicultural activities carried out in the Marganai forest has been found by our witnesses mainly via online communication: social networks, newspapers, or blogs. The information conveyed through social media is hardly submitted to the control of reliability and scientific validity (Table 6) before dissemination. The result is possible exploitation and distortions for ideological purposes ([13], among others). In the specific case of the cuttings of the Marganai forest, this was possible because the public institutions would not seem to have adequately considered the importance of creating a participatory information path with respect to these issues.

Witnesses highlight the lack of a role of guidance and information on the part of public institutions, a role that could have mediated and prevented ideological contrasts [75,76]. Planning a participatory path of stakeholder engagement can be useful on several levels. From a cultural point of view, it could promote the rediscovery and diffusion of cultural elements linked to forest cycles. It could also contribute to worsen the generational fracture created by the abandonment of the rural dimension. From a socio-economic point of view, coppice forest management fosters economic activity related to the processing of wood and, therefore, produces wellbeing also in terms of social protection [77].

If public institutions do not take responsibility for promoting actions for the creation of a “well-informed public opinion”, this informative space is occupied by other non-institutional subjects that can influence and direct public opinion towards values that are distant both from the rural culture dimension and from the scientific sphere.

4. Conclusions and Final Discussion

The qualitative approach has allowed us to reconstruct the perceptions of the local population concerning the forest and the connected socio-economic-cultural dynamics. The analysis of the information highlighted the presence of some significant elements, constantly present in the reference bibliography: human-nature interactions; the value of the witness of the stakeholders; and the perception about forest uses [78].

Firstly, a central role of the Marganai forest emerges in terms of its contribution to the community identity, its history, and relational network: the local population still recognizes itself in the forest. Identity, history, and social relationships are elements of a cultural dimension that can contribute to safeguarding the relational dimension between man and nature from possible fractures induced by “hypermodernity”. Hypermodernity is taken to mean to all those processes that could potentially transform the rural environment into “non-places”, into physical aseptic spaces (from a socio-cultural point of view) where people do not create relationships, do not produce history, and do not recognize each other in a shared identity [79]. In this scenario, people enjoy goods or services (environmental) individually and sporadically over time. The urbanization process strongly undermines the resilience of rural communities and leads to “cultural fragmentation”.

Equally important is the stakeholders’ perception of traditional uses of the Marganai forest’s resources: the loss of identity of the link with the forest dimension undermines the intergenerational transfer of knowledge and practical skills related to forest cultivation. Intergenerational fracture is the result of the progressive loss of a community identity through which people have always interpreted the places of everyday life and built up stable social relations over time [60,80]. This fracture has negative repercussions on the local economic dimension that is historically linked to the traditional uses of forest resources. The “common knowledge” has been eroded by postmodern transformative processes with a consequent shift to the sphere of purely scientific “technical knowledge” [81]. The capacity of people to evaluate competently and silently any forestry intervention is also lost if cultural capital is no longer the result of knowledge handed down and experienced, or the result of practical experience, within a multidimensional perception of the natural environment in which the community lives. Emotionality fosters a vision of the natural dimension in which human interventions that can modify the natural environment (even if historically always implemented) are interpreted in a negative way and therefore hindered, or condemned, by the less informed public opinion.

This research highlighted also that if the population is adequately informed about silvicultural activities, a greater awareness of the complexity of the problems in the management of the community material (natural) and intangible (cultural) goods emerges (see also, e.g., [82,83]). The institutions responsible for governing the interventions should play a central role in an information process aimed at promoting the participation of citizens and the assumption of shared responsibility through effective planning. For example, they could involve citizens in informative paths on silvicultural activities, also putting the accent on the cultural–traditional, as well as scientific dimension, considering all the available options within the sustainability framework, from most strictly conservative prospects, limited to monitoring, up to the most productive ones like coppicing. It is widely believed in forestry that efficient and effective management of environmental resources should take into account and enhance the information and participatory processes that actively involve local communities. Participation creates awareness and shared knowledge that reduces the distance between “urbanized citizens”, bearers of a romantic vision of the forest environment, and rural communities, holders of values and traditions that derive from the daily interaction with the physical resources of the forest. The balance between social, economic, and environmental needs produces tangible benefits and responses to the needs of the territory that can be addressed through participatory process [83].

The results of the research suggest the need to study the knowledge of silvicultural activities via an approach devoid of ideological connotations. The emotional dimension, linked to the perception of environmental risks [72], if combined with pragmatic elements of rural cultural capital, can lead public opinion to the creation of original insights about future socio-economic development. A multidisciplinary approach to the analysis of the socio-economic dimensions can help to develop new prospects for the forest management planning and decision-making process [84]. Finally, a holistic silvicultural model, which also includes the participative process, can safeguard different ecosystem services of the Marganai forest.

One last comment should be reserved for the methodological aspect. During this work, where sociologists and foresters collaborated closely, getting to understand each other’s world, it became evident that social research in a forestry context cannot be conducted without adequate basic training, especially for semi-structured interviews. The person doing this must have a specific competence and mastery of the dynamics of conversation, which are often not part of the forester’s cultural background. For example, with the exception of the question stimulus of departure (which is always the same and presented identically to all witnesses), the questions rarely follow the order indicated in the diagram [85]. The structure of the topics or questions of a semi-structured interview is not binding, neither in the formulation nor in the presentation order [86]. It is characterized by a high degree of discrepancy in the stimuli to which the witness is subjected. This allows unexpected but essential information to emerge helping to complete the reconstruction of the social phenomenon under investigation. The hope is that sociologists and foresters can collaborate more systematically in land and forest planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G., L.C., G.B., I.P., R.S., A.G., S.F.C., E.G., I.M., R.L., M.S.; methodology, G.B., L.C., I.P.; formal analysis, G.B.; investigation, G.B.; data curation, G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.B., F.G., I.P.; writing—review and editing, F.G., I.P., R.S., L.C., M.S., I.M.; visualization, A.G., I.M.; supervision, F.G.; project administration, F.G., L.C.; funding acquisition, F.G., L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Regione Sardegna (Italy), co-funded by European Regional Development Fund (ROP Sardegna ERDF) [project code SULCIS-820965]. Project title: “Environmental and socio-economic sustainability of coppice forest utilization in Marganai”.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the project partners for their important contribution in the realization of the research. We are immensely grateful to all the respondents of the survey for their availability and for their precious testimonies. We would like to thank Andrea Vargiu and Mariantonietta Cocco of the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sassari, for their helpful suggestions in the development of the qualitative approach of this sociological research. A special thanks to Elisa Marras for drawing the graphical abstract. We also thank Ludmila Ribeiro Roder, Francesca Angius, Matteo Piccolo and Gonario Sirca for their active support to the Marganai project. Finally, the municipality of Iglesias for their willingness and logistic support for the final conference of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Piussi, P.; Alberti, G. Selvicoltura Generale. Boschi, Società e Tecniche Colturali; Compagnia delle Foreste S.r.l.: Arezzo, Italy, 2015; p. 432. ISBN 978-88-98850-11-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna-Garcia, X.; Marey-Pèrez, M.F. Public participation: A need of forest planning. iForest 2014, 7, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sectoral Activities Department International Labour Office. Public Participation in Forestry in Europe and North America. Report of the Team of Specialists on Participation in Forestry; Joint Fao/Ece/Ilo Committee on Forest Technology, Management and Training, Geneva, CH. 2000. Available online: http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/timber/joint-committee/participation/report-participation.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- De Meo, I.; Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G. The attractiveness of Forests: Preferences and perceptions in a mountain community in Italy. Ann. Res. 2015, 58, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Ruda, A.; Kalasová, Z.; Paletto, A. The forest stakeholders’ perception towards the NATURA 2000 network in the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Giacovelli, G.; Grilli, G.; Balest, J.; De Meo, I. Stakeholders’ preferences and the assessment of forest ecosystem services: A comparative analysis in Italy. J. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbrielli, A. Le vicende storiche e demografiche italiane come causa dei cambiamenti del paesaggio forestale. In ANNALI; Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forestali: Firenze, Italy, 2006; Volume 55, pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bernetti, G.; La Marca, O. Il bosco ceduo nella realtà italiana. In Atti della; Accademia dei Georgofili: Firenze, Italy, 2012; pp. 542–585. ISBN 978-88-596-1040-3. [Google Scholar]

- Beccu, E. Tra cronaca e storia Le vicende del patrimonio boschivo in Sardegna; Carlo Delfino editore: Sassari, Italy, 2000; p. 432. ISBN 88-7138-196-3. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, M.; Vizzarri, M.; Lasserre, B.; Sallustio, L.; Tavone, A. Natural capital and bioeconomy: Challenges and opportunities for forestry. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2015, 38, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, P. Forestry research to support the transition towards a bio-based economy. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2014, 38, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbio, G. Coppice forests, or the changeable aspect of things, a review. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2016, 40, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, G.A. La Selva Preistorica del Sulcis che Diventa Legna da Ardere. Available online: https://www.corriere.it/scienze/15_settembre_07/selva-preistorica-sulcis-che-diventa-legna-ardere-1c366754-5524-11e5-b550-2d0dfde7eae0.shtml (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- O’Brien, E.A. Human values and their importance to the development of forestry policy in britain: A literature review. Forests 2003, 76, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farcy, C.; Devillez, F. New orientations of forest management planning from an historical perspective of the relations between man and nature. For. Pol. Econ. 2005, 7, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelhas, J.; Zabawa, R.; Molnar, J.J. New opportunities for social research on forest landowners in the South. South. Rur. Sociol. 2003, 19, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.L.; Canavera, E. Domusnovas Dalle Origini al ′900: Ricerca Storica, Documentaria, Bibliografica e sul Territorio; Comune di Domusnovas: Domusnovas, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Airi, M.; Casula, A.; Asoni, G. Piano Di Gestione Complesso Marganai-Ripristino Del Governo a Ceduo Su Aree Demaniali; Personal Communication: Cagliari, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- SardegnaForeste Notizie. Available online: https://www.sardegnaforeste.it/notizia/avvio-della-pianificazione-forestale-particolareggiata-nelle-foreste-demaniali (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Niccolini, M.; Perrino, M. Piano Forestale Particolareggiato Del Complesso Forestale “Marganai” Ugb “Marganai”-“Gutturu Pala” Relazione Tecnica. Available online: http://www.sardegnaambiente.it/documenti/3_68_20140701114331.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- A.T.P “C.C.W.R” progettazioni e soluzioni ambientali, sviluppo equo ed ecosostenibile. Richiesta incontro tecnico: discussione su problematiche riscontrate su habitat forestali in area SIC MONTE LINAS-MARGANAI ITB041111 e limitrofe, 2015. Letter addressed to the “Sardegna Regional Forest Service”, dated 11 Novembre 2014. Available online: https://gruppodinterventogiuridicoweb.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/richiesta-incontro-tecnico-ente-for.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Gruppo d’Intervento Giuridico odv. Foreste demaniali sarde e direttiva Habitat, un contributo del dott. Francesco Aru. Available online: https://gruppodinterventogiuridicoweb.com/2014/06/20/foreste-demaniali-sarde-e-direttiva-habitat-un-contributo-del-dott-francesco-aru/ (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Giadrossich, F.; Guastini, E. A critical analysis of Vacca, A., Aru, F., Ollesch, G. (2017). Short term impact of coppice management on soil in a Quercus ilex L. Stand in Sardinia. Land Degradation & Development 2019, 28, 553–565. Land Degrad. Develop. 2019, 30, 1765–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piano Di Gestione Dei Tagli Boschivi Del Cf N °-15- Marganai– Ugb 1, Allegato A, Capitolato Tecnico Delle Condizioni Sotto le Quali è Posto in Vendita il Materiale Legnoso Proveniente dal Ceduo Semplice con Rilascio di Matricine del Bosco Sito in Località “Su Caraviu E Su Isteri” in Agro del Comune Di Domusnovas. Regione Autonoma della Sardegna, Ente Foreste della Sardegna. 2010. Available online: http://www.sardegnaambiente.it/documenti/3_233_20100204102403.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 8th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences, 3rd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, H. The logic of qualitative survey research and its position in the field of social research methods. Forum Qualit. Soci. Res. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G. Tell me about…: Using interviews as a research methodology. In Methods in Human Geography: A Guide for Students Doing a Research Project, 2nd ed.; Flowerdew, R., Martin, D., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Essex, UK, 2005; pp. 110–126, ISBN-13: 9780582473218. [Google Scholar]

- Vargiu, A. Metodologia e Tecniche per la Ricerca Sociale, 1st ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2007; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, A.L.; Miles, S. Stakeholders: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 362. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.R.; Qureshi, M.E. Choice of stakeholder groups and members in multi-criteria decision models. Nat. Resour. For. 2000, 24, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakos, P. Social Research, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- Ananda, J.; Herath, G. The use of analytic hierarchy process to incorporate stakeholder preferences into regional forest planning. For. Pol. Econ. 2003, 5, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candrea, A.N.; Bouriaud, L.A. Stakeholders’ analysis of potential sustainable tourism development strategies in Piatra Craiului National Park. Ann. For. Res. 2009, 52, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, T.H. Conceptualizing and Proposing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN-13: 978-0131702868. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Archer, M.S. Making Our Way Through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN-13: 978-0521696937; ISBN -13. [Google Scholar]

- Fukujama, F. Social Capital, Civil society and development. Third World Quart 2001, 22, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision making. Geoforum 2012, 43, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre; TP Verone Publishing: Einbeck, Germany, 2013; p. 588. ISBN 9783863831936. [Google Scholar]

- Goudy, W.J. Community attachment in a rural region. Rur. Soc. 1990, 55, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannerz, U. Transnational Connections. Culture, People, Places, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 216. ISBN 9780415143097. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; p. 480, ISBN-13: 978-0465097197. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, W. Cultures and Society in a Changing World, 2nd ed.; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, M. Towards a rural sociological imagination: Ethnography and schooling in mobile modernity. Ethnol. Educ. 2015, 10, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieder, T.; Garkovich, L. Landscapes: The social construction of nature and the environment. Rural Sociol. 1994, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; p. 128, ISBN-13: 978-0226672984. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement; Minuit: Paris, France, 1979; p. 670, ISBN-13: 978-2707302755. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Raisons Pratiques. Sur la Théorie de L’action; Seuil: Paris, France, 1994; p. 252, ISBN-13: 978-2020231053. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. Assets and affect in the study of social capital in rural communities. Sociol. Rur. 2016, 56, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P. Sociology and History; Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1980; p. 116, ISBN-13: 9780043011157. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a Way of Life; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964; pp. 60–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Implosion/Explosion: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. 573, ISBN-13: 978-3868593174. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Dynamics. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Bell, M. The fruit of difference: The rural-urban continuum as system of identity. Rural Sociol. 1992, 57, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.J. The Urbanism of Exception. The Dynamics of Global City Building in the Twenty-First Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; p. 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, H. Cultural tradition and social change in agriculture. Sociol. Rur. 1990, 30, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardsen, T.; Lowe, P.; Whatmore, S. Rural Reconstructuring. Global Processes and Their Responses; Fulton Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 1990; p. 197. ISBN 1853461113. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 200, ISBN-13: 978-0745609232. [Google Scholar]

- De Meo, I.; Ferretti, F.; Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G. An approach to public involvement in forest landscape planning in Italy: A case study and its evaluation. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2017, 41, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touraine, A. Pourrons-Nous Vivre Ensemble? Fayard: Paris, France, 1997; p. 395, ISBN-10: 221359872X. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; D’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruel, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, S.C.; Costanza, R.; Wilson, M.A. Economic and ecological concepts for valuing ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Comín, F.A.; Escalera-Reyes, J. A framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services. Ambio 2015, 44, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.D. Silvicultural Systems; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991; p. 296, ISBN-13: 978-0198546702. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, G.P. Ecology and Management of Coppice Woodlands; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1992; p. 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneifl, M.; Kadavy, J.; Knott, R. Gross value yield potential of coppice, high forest and model conversion of high forest to coppice on best sites. J For. Sci. 2011, 57, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.J. Conceiving forest management as providing for current and future social value. For. Ecol. Man. 1985, 13, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmithüsen, F. Multifunctional forestry practices as a land use strategy to meet increasing private and public demands in modern societies. J. For. Sci. 2007, 53, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Hill, C.A.; Dean, E. Social Media, Sociality and Survey Research; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Public opinion does not exist. In Communication and Class Struggle; Mattelart, A., Siegelaub, S., Eds.; International General: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 124–130. ISBN 0-88477-011-7. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft; Suhrkamp Verlag AG: Frankfurt, Germany, 2001; p. 391, ISBN-13: 978-3518284919. [Google Scholar]

- Nikodinoska, N.; Paletto, A.; Pastorella, F.; Granvik, M.; Franzese, P.P. Assessing, valuing and mapping ecosystem services at city level: The case of Uppsala (Sweden). Ecol. Model. 2018, 368, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, D.A.; Stokes, M.K. Public participation and institutional fit: A social-psychological perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Pritchard, L.; Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Svedin, U. The problem of fit between ecosystems and institutions: Ten years later. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirivayia, N.; Nennena, L.; Tesfayea, W.; Mab, Q. The benefits of collective action: Exploring the role of forest producer organizations in social protection. For. Pol. Econ. 2018, 90, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, M.; Hagerman, S.; Kozak, R. Going deeper with documents: A systematic review of the application of extant texts in social research on forests. For. Pol. Econ. 2018, 92, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augé, M. Non-lieux. Introduction à Une Anthropologie de la Surmodernité; Seuil: Paris, France, 1992; p. 150, ISBN-13: 978-2020125260. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; p. 228. ISBN 0-7456-2409-X. [Google Scholar]

- Zoppi, C.; Lai, S. Assessment of the regional landscape plan of Sardinia (Italy): A participatory-action-research case study type. Land Use Pol. 2010, 27, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, A.; Nijnik, M.; Kopiy, S.; Zahvoyska, L.; Sarkki, S.; Kopiy, L.; Miller, D. Identifying and understanding attitudinal diversity on multi-functional changes in woodlands of the Ukrainian Carpathians. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, K.T.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: A case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. For. Pol. Econ. 2019, 100, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, S.; Scotti, R.; Piredda, I.; Murgia, I.; Ganga, A.; Giadrossich, F. The open data kit suite, a mobile data collection technology as an opportunity for forest mensuration practices. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2020, 44, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichi, R. La Conduzione Delle Interviste Nella Ricerca Sociale, 2nd ed.; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2011; p. 216. ISBN 9788843038008. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 258. ISBN 9780814732939. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).