Abstract

Efficient object detection is vital for Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) performing marine debris cleanup, yet existing lightweight designs frequently encounter efficiency bottlenecks when adapted to deeper neural networks. This research identifies a critical “Inverted Bottleneck” anomaly in the Slim-Neck architecture on the YOLO11 backbone, where deep-layer Memory Access Cost (MAC) abnormally spikes. To address this, we propose SvelteNeck-YOLO. By incorporating the proposed EHSCSP module and EHConv operator, the model systematically eliminates computational redundancies. Empirical validation on the TrashCan and URPC2019 datasets demonstrates that the model resolves the memory wall issue, achieving a state-of-the-art trade-off with only 5.8 GFLOPs. Specifically, it delivers a 34% relative reduction in computational load compared to specialized underwater models while maintaining a superior Recall of 0.859. Consequently, SvelteNeck-YOLO establishes a robust, cross-generational solution, optimizing the Pareto frontier between inference speed and detection sensitivity for resource-constrained underwater edge computing.

1. Introduction

With the widespread adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) and edge computing technologies, the paradigm of computer vision has fundamentally shifted from cloud-centered processing to edge-side intelligence [1]. As the cornerstone of visual perception, object detection has become widely applied in resource-constrained scenarios, such as fire detection in intelligent surveillance [2], real-time Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imaging on satellites [3], transmission line inspections by high-altitude drones [4], and defect detection in industrial automation [5]. In underwater applications, object detection is especially critical yet daunting due to the unique optical characteristics of the aquatic medium. Unlike structured terrestrial scenes, underwater environments suffer from severe image degradation caused by wavelength-dependent light absorption and scattering, resulting in color distortion, low contrast, and high turbidity [6,7,8]. Furthermore, dynamic background noise, such as marine snow and water turbulence, frequently obscures targets, rendering standard visual perception algorithms unreliable. In parallel, multi-frequency perception with complementary fusion has been investigated to improve representation robustness in complex scenes [9], which is conceptually relevant to underwater imagery where degradation and background clutter challenge feature fusion. For this reason, underwater robots rely heavily on visual information for environmental awareness, particularly in real-time object detection on low-power, low-latency edge computing platforms, which greatly enhances task accuracy and autonomy [10,11,12].

However, deploying advanced detectors such as the YOLO series on edge devices remains challenging, because constraints on computation, memory bandwidth, and energy consumption often conflict with the demand for high accuracy [11,13]. This conflict is amplified in underwater robots, which must perform real-time, on-device inference without relying on high-latency shore-based cloud computing. Therefore, designing lightweight architectures that balance efficiency and accuracy has become a research hotspot [14].

To alleviate the computational burden, researchers have extensively explored efficient neural network components. Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC), popularized by MobileNet and Xception, has been widely adopted in lightweight detection networks and YOLO variants to reduce parameter size and Floating-Point Operations (FLOPs) [15,16], as evidenced by recent lightweight designs for small-object detection [17]. Despite the high efficiency of DSC, its inherent channel information separation weakens feature extraction capability, especially for detecting small or significant targets [18]. To address this issue, Ghost-module-based YOLO variants leverage cheap feature generation operations to efficiently produce redundant feature maps for lightweight representation, e.g., Ghost-YOLOv8 [19]. Moreover, Ghost-Attention-YOLOv8 shows that combining Ghost modules with attention mechanisms can further reduce model size while maintaining practical performance [20]. Similarly, LFRE-YOLO and YOLO-Fast enhance inference speed on edge platforms by optimizing backbone structures [4,21]. Beyond convolution-centric designs, recent studies have also explored efficient feature aggregation and compression strategies, such as graph-adaptive pooling with information-bottleneck principles, to enhance edge understanding under resource constraints [22].

Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC) provides an efficient approach to lightweight architectures, but its limitation in feature extraction, especially for complex or small targets, has led to further exploration of structural improvements. The Slim-Neck design emerged in this context to address the shortcomings caused by channel information separation and enhance feature fusion capability. Li et al. proposed the “Slim-Neck” design [23] to tackle this bottleneck. Their research shows that the “neck” of detection networks, responsible for multi-scale feature fusion, is a computational bottleneck. By introducing GSConv (Group Shuffling Convolution), which merges Standard Convolution (SC) with DSC through channel shuffling, they successfully reduced complexity while preserving implicit channel relationships. This design has been validated in industrial defect detection, demonstrating that replacing the Standard Convolution (SC) in the neck with a GSConv-based structure can significantly increase the frame rate without sacrificing mean average precision (mAP) [5]. Beyond industrial applications, this lightweight paradigm has also been successfully adapted to the marine domain; for instance, Cai et al. [24] validated the broad applicability and effectiveness of GSConv-based structures for efficient underwater object detection.

Although lightweight detection has been widely studied, purely lightweight designs may sacrifice representation capability and become more sensitive to difficult cases (e.g., small objects, occlusion, and blur) [25]. More importantly, Slim-Neck is architecturally coupled to YOLOv8; when directly ported to the newer YOLO11 backbone, its split–shuffle operator pattern (e.g., GSConv) may increase memory traffic in deep fusion layers, as revealed by our profiling and MAC analysis, leading to a “low FLOPs, high latency” phenomenon. This motivates a redesigned neck that prioritizes hardware affinity and mitigates memory-access bottlenecks.

Inspired by the efficiency of GSConv and the elegant structure of Slim-Neck, and recognizing their shortcomings in hardware affinity and feature alignment, this paper proposes an improved lightweight YOLO Neck structure—SvelteNeck. We name the proposed structure ‘SvelteNeck’ to reflect its design philosophy: a streamlined and cohesive architecture that eliminates the structural fragmentation inherent in previous lightweight designs. The structure, based on the principle of ‘retaining key multi-scale fusion ability,’ refines and reconstructs the feature fusion path and computation units of the neck. This design achieves an optimal balance between parameter reduction and computational complexity, while maintaining representation ability and localization stability for small-scale targets across different YOLO generations.

Experimental results show that the proposed method significantly improves operational efficiency while ensuring detection accuracy, providing an efficient and deployable solution for underwater platforms to execute seabed waste detection tasks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Analysis of Computational Efficiency

Existing lightweight modifications for YOLO, such as Slim-Neck, heavily rely on Group Shuffling Convolution (GSConv) to reduce parameters. While effective in YOLOv8, this design exposes significant efficiency bottlenecks when integrated into the highly optimized YOLO11 architecture. We analyze this limitation through the relationship between Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) and Memory Access Cost (MAC) [26].

The theoretical computational cost of a Standard Convolution (SC) is defined as:

where , are the feature map dimensions, is the kernel size, and , are input/output channels.

The Slim-Neck architecture replaces SC with GSConv. GSConv approximates the representation capability of SC by combining a Standard Convolution (with ) and a Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC), followed by a channel shuffle. Theoretically, this reduces FLOPs to approximately half:

However, FLOPs are not the sole determinant of inference latency, especially on edge devices. The actual latency is heavily constrained by MAC and the degree of parallelism. The channel shuffle operation in GSConv introduces non-negligible memory overhead. The reshape and permute operations required for shuffling do not contribute to FLOPs but significantly increase MAC:

where Tinference denotes the total inference latency. The term Parallelism represents the effective degree of parallel processing on the hardware (e.g., GPU utilization rate), and is a hardware-specific coefficient inversely proportional to memory bandwidth. This equation highlights a critical trade-off: while Slim-Neck reduces the theoretical FLOPs, its fragmented operator design (splitting and shuffling) significantly degrades Parallelism and increases the memory overhead term (MAC). As a result, the reduction in computation is offset by the penalties in parallelism and memory access, leading to suboptimal inference speed on high-performance architectures like YOLO11.

In YOLO11, the native C3k2 module utilizes optimized dense convolutions that maximize hardware parallelism. In contrast, the VoVGSCSP module in Slim-Neck forces the data flow through multiple split-transform-merge stages with GSConv. This fragmentation leads to a lower effective bandwidth utilization. Mathematically, for the same channel expansion ratio, the “fragmented” MAC of VoVGSCSP exceeds the “dense” MAC of C3k2 due to the additional intermediate feature maps generated during the shuffle process:

Therefore, directly transplanting the Slim-Neck (designed for the heavier C2f backbone of YOLOv8) into YOLO11 results in a “low FLOPs, high Latency” trap, negating the architectural upgrades of YOLO11. This necessitates the proposed SvelteNeck, which prioritizes hardware affinity using Large-Kernel Depthwise Convolutions without complex shuffling. We will empirically validate this theoretical limitation in Section 3.4, where layer-wise profiling demonstrates that the Slim-Neck architecture suffers from drastically reduced Arithmetic Intensity in the feature fusion layers compared to our proposed method.

2.2. The Proposed SvelteNeck-YOLO Architecture

Guided by the theoretical analysis in Section 2.1, we propose SvelteNeck-YOLO, a hardware-friendly lightweight architecture designed to overcome the “low FLOPs, high Latency” trap inherent in Slim-Neck. Unlike the fragmented operator design of GSConv, SvelteNeck adheres to the principle of “maintaining high parallelism while minimizing Memory Access Cost (MAC).” By reconstructing the feature fusion path and computational units within the Neck, the proposed architecture achieves a dual improvement in both computational efficiency and detection accuracy.

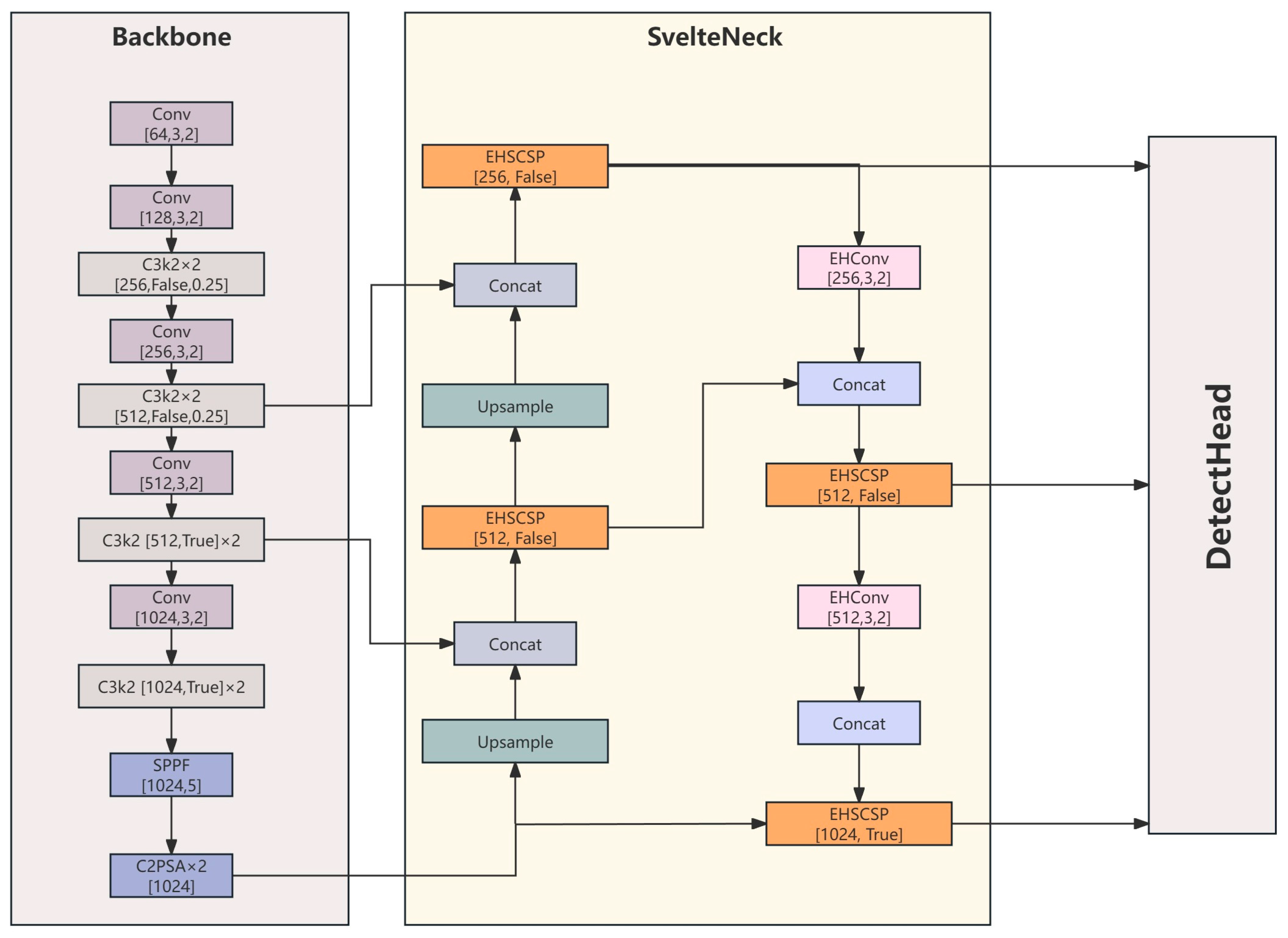

SvelteNeck-YOLO is built upon the YOLO11 framework, retaining its efficient Backbone and Decoupled Head, with core modifications concentrated in the feature fusion network (Neck). The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 1. The detailed architecture specifications (Scale: n) are provided in Appendix A (Table A1).

Figure 1.

Overall Architecture of SvelteNeck-YOLO.

- Backbone: Stable Multi-scale Feature Extraction

The backbone is responsible for providing feature maps at different semantic levels. We retain the YOLO11n backbone design, utilizing C3k2 modules with optimized dense convolutions for feature extraction, and introducing SPPF and C2PSA modules at high levels to enhance the global receptive field. The backbone outputs features at three scales: P3 (80 × 80), P4 (40 × 40), and P5 (20 × 20), providing a high-parallelism input foundation for the Neck.

- 2.

- SvelteNeck: High Arithmetic Intensity Feature Fusion

Addressing the low arithmetic intensity issue of VoVGSCSP identified in Section 2.1, SvelteNeck redesigns the feature fusion path. It adopts the classic “Top-down Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) + Bottom-up Path Aggregation Network (PAN)” bidirectional topology but implements fundamental innovations in operator selection:

- Eliminating Fragmented Shuffling: We discard GSConv, which relies on Channel Shuffle and Split operations, thereby eliminating redundant memory transfer overhead (MAC).

- Incorporating Large-Kernel Depthwise Convolutions: The EHSCSP module is introduced to replace the original C3k2 or VoVGSCSP. The core unit of this module is EHConv, which utilizes a 5 × 5 large kernel within a depthwise separable convolution structure to expand the receptive field. This design maintains operator continuity while keeping parameter counts low, thereby preserving high Arithmetic Intensity.

- Reconstructing Downsampling Paths: In the downsampling stages of the PAN path, SvelteNeck employs lightweight operators that retain large receptive fields, ensuring that detailed information is not lost due to channel compression when flowing back to deeper layers.

- 3.

- Head

The detection head directly decodes the three aligned feature maps output by SvelteNeck, predicting the categories and positions for large, medium, and small objects, respectively.

SvelteNeck is primarily composed of three core modules: EHConv, EHSBottleneck, and EHSCSP. The principles of each module will be introduced one by one below.

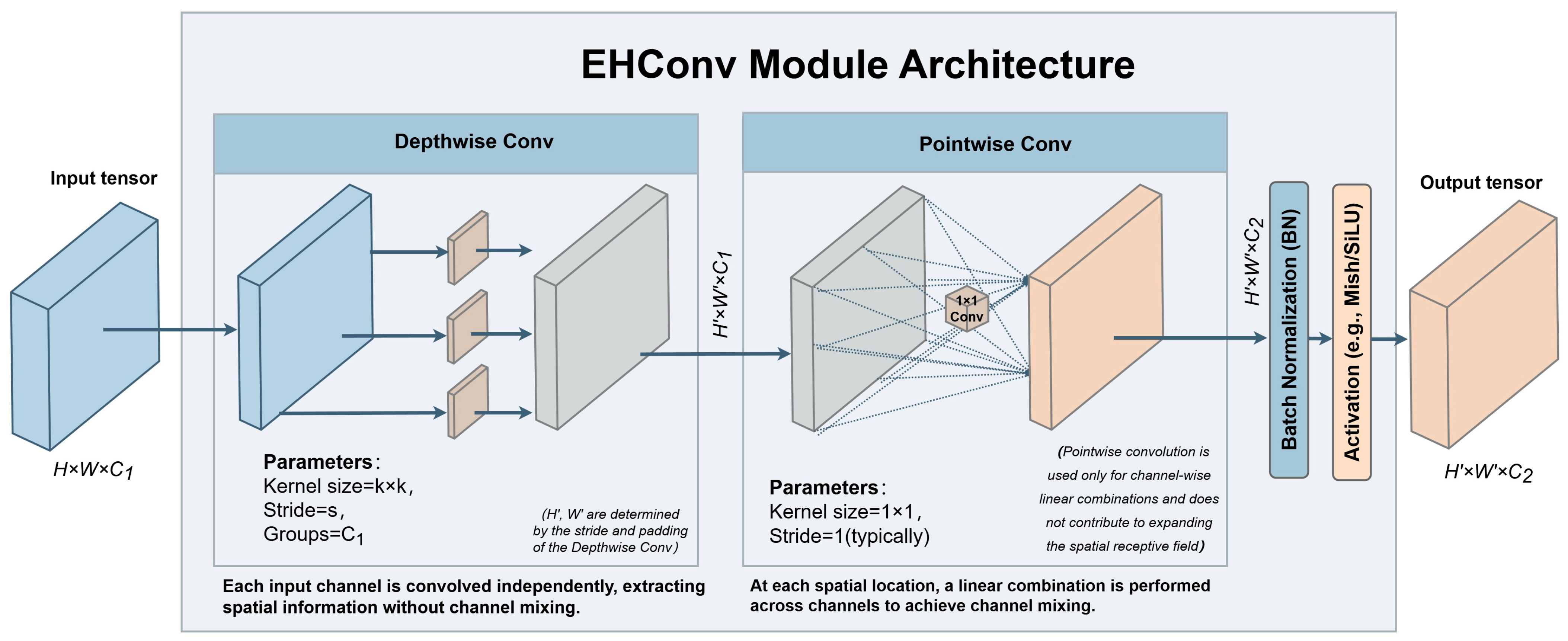

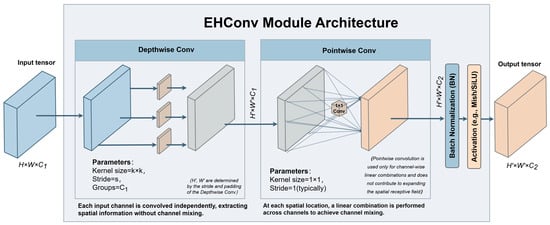

2.3. EHConv: Receptive-Field-Oriented Lightweight Convolution

In complex underwater environments, optical scattering and absorption often result in significant blurring and diffusion of object edges and textures. Traditional feature transformations based on 3 × 3 convolutions in the Neck stage struggle to effectively model such long-range dependencies and structural information, while directly employing large-kernel Standard Convolutions would impose a prohibitive computational burden. To address this, we designed a receptive-field-friendly lightweight operator named EHConv (Efficient Hybrid Convolution), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of EHConv.

As shown in Figure 2, EHConv adopts the Depthwise Separable Convolution paradigm. Its mathematical expression is defined as:

where and denote the input and output feature tensors, respectively. represents the Large-Kernel Depthwise Convolution (), designed to expand the spatial receptive field and capture contextual information of blurred underwater targets, addressing the limitation of traditional 3 × 3 convolutions. denotes the 1 × 1 Pointwise Convolution, responsible for feature fusion and linear combination across channel dimensions. and represent Batch Normalization and the SiLU activation function, respectively; the former calibrates feature distribution to adapt to underwater illumination variations, while the latter introduces non-linearity to enhance the model’s representational capability.

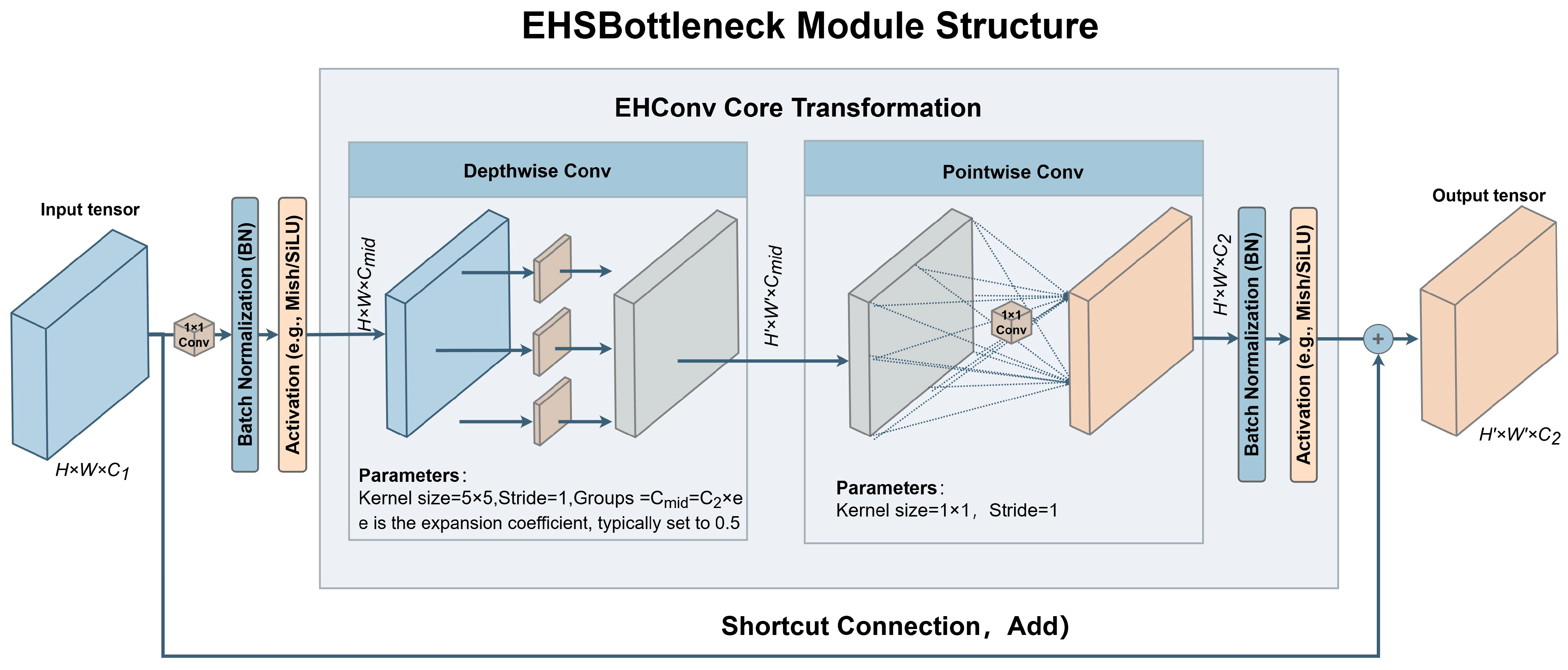

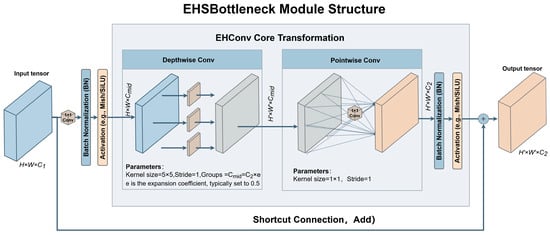

2.4. EHSBottleneck: Efficient Hybrid Large-Kernel Bottleneck

In the process of neck feature fusion, bottleneck structures are typically employed to achieve efficient non-linear feature transformation within a limited computational budget [27]. However, traditional Bottleneck units often rely on Standard Convolutions for spatial modeling, where parameter size and computational complexity increase linearly with the number of channels, hindering their ability to be stacked deeply in lightweight neck networks. To address this, we construct a lightweight bottleneck unit named EHSBottleneck (Efficient Hybrid Shuffle Bottleneck), centered around the EHConv operator. Its structure is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structure of EHSBottleneck.

The module first applies a 1 × 1 convolution to project and compress the input features into an intermediate dimension . Here, represents the channel compression ratio (set to in this study), designed to significantly reduce the computational overhead of the subsequent spatial modeling stage. Within this low-dimensional feature space, EHConv is introduced as the core transformation module. It utilizes a Large-Kernel Depthwise Convolution (DWConv, with ) to perform channel-wise spatial modeling, combined with a Pointwise Convolution (PWConv, 1 × 1) to achieve cross-channel information fusion and dimensionality restoration (). This design effectively expands the receptive field of the features at a minimal computational cost.

At the end of the module, when the input and output channel dimensions match, EHSBottleneck introduces a residual learning mechanism via a Shortcut Connection. This performs an element-wise addition between the input features and the main branch output, enhancing gradient propagation capabilities and improving training stability in deep networks. Thanks to these designs, EHSBottleneck significantly reduces unit-level computational complexity while maintaining the representational power of the bottleneck structure. This enables multi-level stacking within the neck feature fusion module, thereby providing richer and more efficient intermediate representations for subsequent multi-scale feature aggregation.

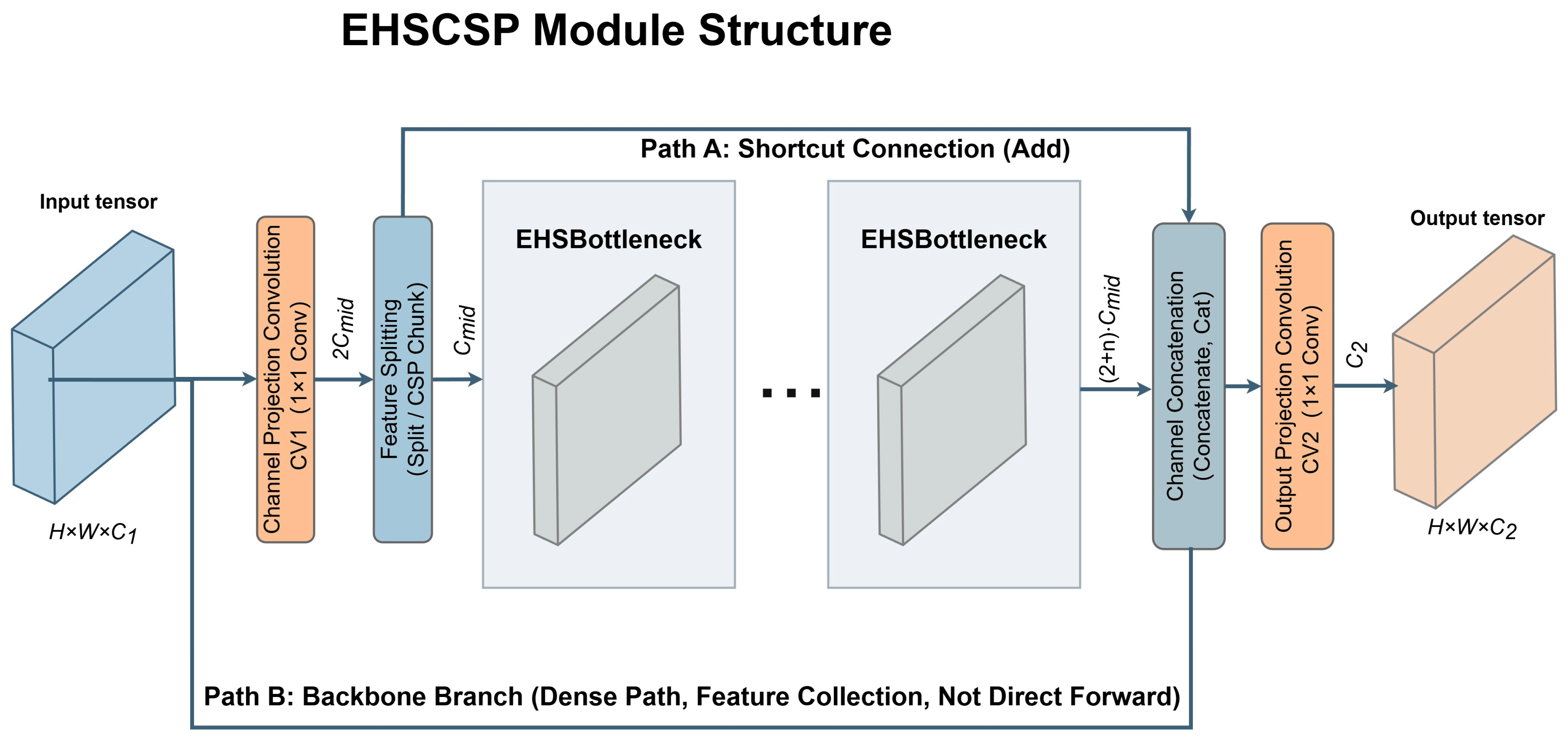

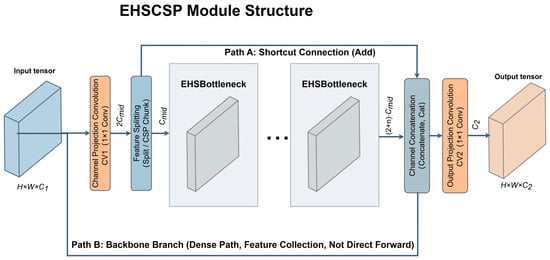

2.5. EHSCSP: Lightweight Aggregation Module

In YOLO11, neck feature fusion relies on efficient split-and-aggregation mechanisms to achieve collaborative modeling of semantic information across different levels while maintaining spatial resolution. To avoid disrupting the original gradient flow organization, SvelteNeck adheres to the mature “Split-Stack-Aggregate” paradigm of the YOLO series. On this basis, we construct a lightweight feature aggregation module named EHSCSP (Efficient Hybrid Stage Cross Stage Partial Network), as illustrated in Figure 4, to achieve stable feature reuse and fusion representation at a lower computational cost [28].

Figure 4.

Structure of EHSCSP.

Let the input feature map be denoted as . First, a 1 × 1 convolution (CV1) adjusts the channel dimension, mapping the features to . In this step, we introduce a channel compression coefficient (set to in this work) to map the features to , thereby controlling the overall computational scale while preserving representational capacity. Subsequently, the features are split equally along the channel dimension into two branches: one serves as the cross-stage collateral branch (Path A), retaining shallow information directly; the other serves as the main branch (Path B), entering a stacked structure composed of multiple EHSBottlenecks for progressive feature transformation.

In the main branch, each EHSBottleneck maintains consistent input and output channel counts, performing feature transformation at a fixed spatial resolution. Specifically, EHConv is uniformly configured with stride = 1, undertaking only spatial structure modeling and channel semantic reorganization without introducing additional downsampling. This ensures consistent feature dimensions between the two split branches in the CSP-style structure and in the subsequent aggregation stage, avoiding extra scale alignment operations and effectively reducing structural complexity [28].

Unlike the layer-wise residual addition aggregation method, EHSCSP performs a one-time concatenation of the collateral branch features and the outputs of all EHSBottlenecks in the main branch at the end of the module. This forms an aggregated feature with a channel dimension of , where denotes the number of stacked EHSBottlenecks. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution (CV2) completes the feature fusion and channel alignment, remapping the channel count to to obtain the final output.

Benefiting from the “One-time End Aggregation + Cross-Stage Collateral Retention” structure, EHSCSP preserves multi-level feature representations intact while maintaining stable gradient backpropagation. Combined with the lightweight characteristic of EHSBottleneck, which performs large-kernel spatial modeling in a low-dimensional channel space, this module possesses strong multi-scale feature fusion capabilities while significantly reducing computational load and parameter size. It is particularly well-suited to the dual requirements of efficient aggregation and representational stability in the YOLO11 neck.

3. Experiments and Analysis

3.1. Dataset

To comprehensively validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method, evaluations are conducted on two distinct datasets representing contrasting underwater environments: TrashCan-Instance (representing unconstrained deep-sea debris scenarios) and URPC2019 (representing shallow-water seafood capture scenarios).

3.1.1. TrashCan Dataset

We primarily evaluate our detectors on the TrashCan-Instance 1.0 dataset, a large-scale benchmark for underwater debris detection sourced from the J-EDI deep-sea image library of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC). Unlike controlled shallow-water datasets, TrashCan consists of 7212 images captured by ROVs in deep-sea scenarios, characterized by severe turbidity, variable lighting conditions, and unconstrained seafloor backgrounds.

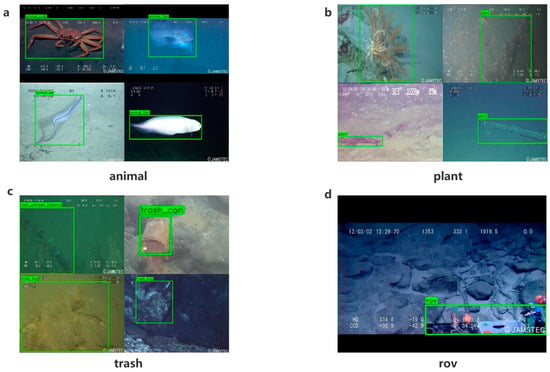

The dataset includes 22 instance-level categories, which are aggregated into four semantic super-classes in this study: (1) Biological Organisms (e.g., fish, crabs, starfish), (2) Plants (e.g., marine vegetation, floating biological fragments), (3) Marine Debris (e.g., bottles, plastic bags, nets, wreckage) and (4) ROV Components (e.g., ROV parts, man-made structures). Due to the absence of an official split, we strictly adhere to prior protocols by randomly partitioning the dataset into an 8:1:1 split (train/val/test) using a fixed random seed.

Figure 5 shows typical annotated examples from the TrashCan-Instance dataset, categorized by semantic groups. Figure 5a presents various animals, where deformable body shapes and low-contrast boundaries against the seafloor make detection difficult. Figure 5b shows sessile and filamentous plants that resemble background textures. Figure 5c depict different types of marine litter, including cans, bags, and unknown fragments, often partially buried or camouflaged by sediments. Figure 5d illustrates the ROV platform, where strong specular highlights and on-screen telemetry further challenge robust localization.

Figure 5.

Representative samples from the TrashCan-Instance dataset. (a) animal; (b) plant; (c) trash; (d) ROV [29].

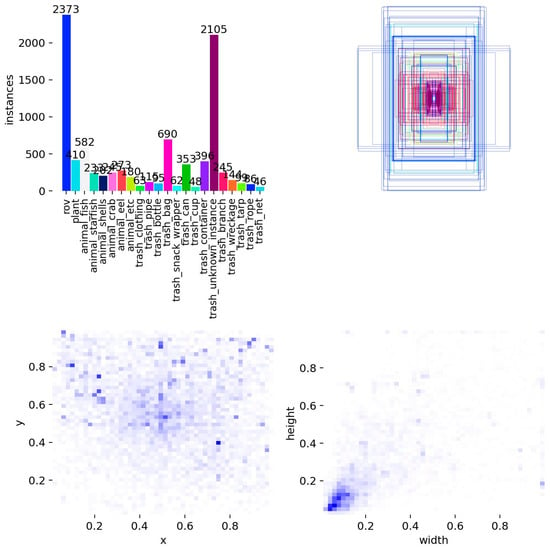

To further characterize the detection challenges, we performed a statistical analysis on the training set labels, as shown in Figure 6. Each object is represented by normalized coordinates .

Figure 6.

Statistical analysis of labels in the TrashCan-Instance dataset.

- Class Imbalance and Long-tail Distribution: The instance count distribution reveals a distinct long-tail characteristic. A few categories (e.g., ROV components and unknown debris) dominate the sample space, while numerous fine-grained biological categories are scarce. This imbalance tends to bias the model towards head classes, increasing the risk of missed detections for tail classes.

- Spatial Bias and Prevalence of Small Objects: The heatmap of object centers indicates a preference for the lower-middle region of images, consistent with the ROV’s top-down viewing angle. Meanwhile, the width-height density plot shows that the vast majority of bounding boxes have small normalized dimensions. This indicates that small objects dominate the dataset. In turbid underwater environments with strong texture interference, these small targets are prone to detail loss.

In summary, TrashCan-Instance possesses combined characteristics of “long-tail distribution + small object dominance + strong background interference.” This serves as a primary motivation for incorporating EHConv and EHSCSP in our SvelteNeck design—to significantly enhance the preservation of fine texture details and the robust fusion of multi-scale features while maintaining a lightweight architecture.

3.1.2. URPC2019 Dataset

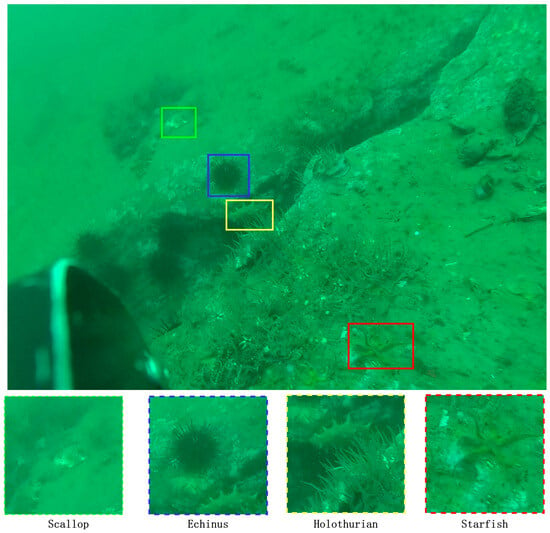

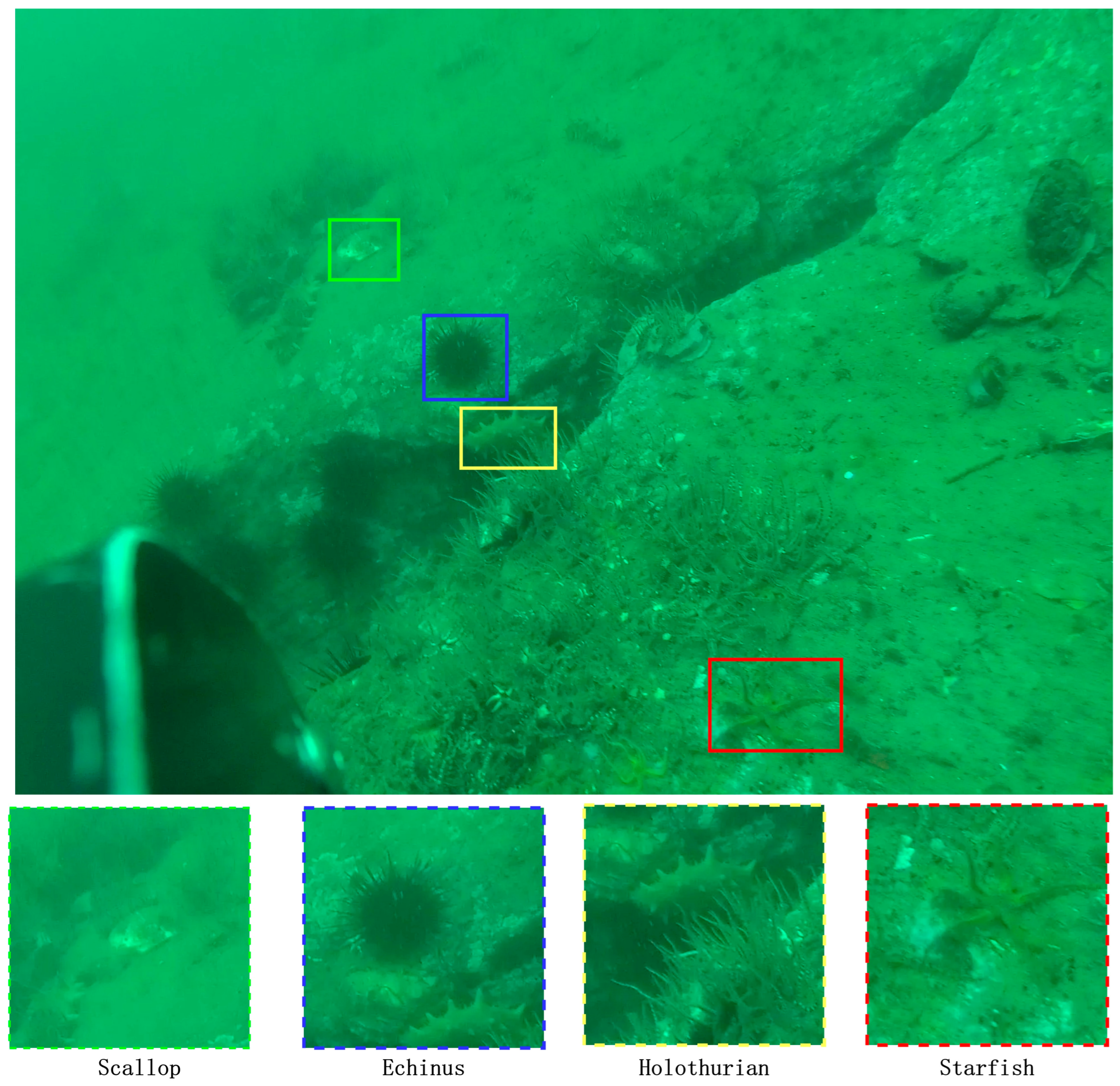

To verify the generalization capability of the model across different water environments, supplementary experiments were conducted on the URPC2019 (Underwater Robot Professional Contest) dataset. Collected primarily in shallow sea environments, this dataset contains four typical seafood categories: Holothurian, Echinus, Scallop, and Starfish. In contrast to TrashCan, URPC2019 images exhibit a distinct greenish-blue color cast and are characterized by dense distribution and clustering of small targets. After filtering out images with missing annotations, we utilized 4765 images for experiments, following the same 8:1:1 split ratio. The inclusion of this dataset helps validate the localization performance of SvelteNeck in dense small-object scenarios.

To intuitively illustrate the detection challenges inherent in this dataset, Figure 7 presents a representative visualized sample containing all four target categories. As shown, the original image (top) exhibits significant turbidity and a greenish-blue color cast, with targets being extremely minute and highly integrated into the complex seafloor background. To reveal the details, we display corresponding color-coded magnified views at the bottom: the Scallop (green box) is almost completely covered by sediment, demonstrating strong camouflage; the Echinus (blue box) shows extremely low contrast against the dark surroundings; while the Holothurian (yellow box) and Starfish (red box) exhibit typical characteristics of small scale and blurred textures. Such scenarios, characterized by dense multi-class distribution and severe background interference, pose a stringent test on the feature extraction and localization capabilities of the detector.

3.2. Experimental Details

All experiments are conducted using Python 3.10.11, PyTorch 2.3.1+cu118, and CUDA 11.8 on a single NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU (24 GB VRAM). All detectors are trained under a unified protocol across both datasets: images are resized to 640 × 640 with a training batch size of 16. To strictly simulate real-time robotic deployment, the inference batch size is set to 1 for all latency and Frames Per Second (FPS) measurements. Data augmentation includes a 50% probability of horizontal flipping, HSV color augmentation (hue 0.015, saturation 0.7, value 0.4), random scaling in the range of 0.5–1.0, translation up to 10% in each direction, mosaic augmentation in the early epochs, as well as RandAugment and random erasing with a probability of 0.4.

We use Adam-based optimization (optimizer = auto) with an initial learning rate of 0.01, momentum 0.937, and weight decay 0.0005, and adopt the default YOLO detection losses. To ensure reproducibility, all experiments are run with a fixed random seed of 42. Except for the number of training epochs, which is adjusted according to the scale of each dataset, all other hyper-parameters are kept identical on TrashCan and URPC2019 to guarantee fair comparison.

Figure 7.

Visualization of a typical multi-class dense scene in the URPC2019 dataset.

Figure 7.

Visualization of a typical multi-class dense scene in the URPC2019 dataset.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

To strictly and comprehensively evaluate the performance of SvelteNeck in underwater scenarios, we adopt standard evaluation metrics commonly used in object detection, including Precision (P), Recall (R),the mean Average Precision (mAP), and computational complexity indicators.

- Computational Efficiency (GFLOPs and Parameters)

To measure the lightweight characteristics of the model, we utilize GFLOPs (Giga Floating-point Operations) to represent the theoretical computational cost, and Parameters to measure the model size. These are calculated as:

where denotes the Floating-Point Operations of the layer . Lower GFLOPs and parameters are critical for deployment on resource-constrained underwater robots (ROVs).

- 2.

- Precision and Recall

Precision () measures the accuracy of positive predictions, while Recall () measures the coverage of true positives. They are defined as:

where , , , are true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives.

- 3.

- Mean Average Precision (mAP)

Average Precision (AP) represents the area under the Precision-Recall (P-R) curve for a specific class . The mean Average Precision (mAP) is the average of AP across all classes (). We report two standard Common Objects in Context (COCO) metrics:

- mAP50: The mAP calculated at a single Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5.

- mAP50–95: The average mAP calculated over multiple IoU thresholds ranging from 0.50 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05. This metric provides a more rigorous assessment of localization accuracy.

3.4. Empirical Validation of Computational Efficiency

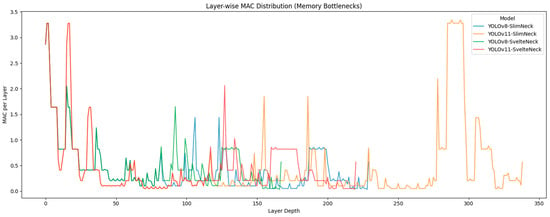

To strictly validate the theoretical derivation in Section 2.1, we conducted a comprehensive layer-wise profiling of Memory Access Cost (MAC). Figure 8 visualizes the global MAC trace across the network depth, while Table 1 details the specific layers responsible for computational bottlenecks. The complete layer-wise profiling report for all four models is provided in the Supplementary Material (CSV).

Figure 8.

Layer-wise Memory Access Cost (MAC) Trace.

Table 1.

Top-5 Layer-wise Memory Access Cost (MAC) Profile.

The “Architecture-Coupling” of Slim-Neck The profiling results reveal a critical efficiency trap when transferring the Slim-Neck architecture from YOLOv8 to YOLO11:

- Normal Distribution in YOLOv8-Slim-Neck: As shown in Table 1, the YOLOv8-Slim-Neck model follows a standard computational profile where the highest MAC consumption occurs at the shallow input layers (e.g., model.0.bn, 3.28 M). This indicates that the GSConv design remains compatible with the YOLOv8 backbone.

- Inverted Bottleneck in YOLO11-Slim-Neck: However, a severe anomaly appears in YOLO11-Slim-Neck. This is visually corroborated by the orange curve in Figure 8, which reveals a distinct “Inverted Bottleneck.” Unlike the expected downward trend, the MAC consumption abnormally spikes in the deep layers (Layer Index > 200), creating a “memory wall” that exceeds the input stage. Table 1 confirms this, showing that the neck convolution layers (model.23.cv3…) reach a peak MAC of 3.34 M. This proves that the fragmented convolution operators in Slim-Neck cause a breakdown in parallelism when applied to the deeper and wider YOLO11 architecture.

In contrast, SvelteNeck restores a hardware-friendly distribution across both backbones. As illustrated by the red curve in Figure 8 (YOLO11-SvelteNeck), the model successfully realigns computational cost with feature map resolution. The high-MAC layers are strictly confined to the initial stages (confirmed by Table 1), and the deep-layer spikes observed in the orange curve are effectively eliminated. This demonstrates that SvelteNeck is a broadly compatible solution that resolves the efficiency paradox.

To further evaluate the robustness and practical efficiency of the proposed method, we conducted comparative experiments on the TrashCan dataset. As shown in Table 2, SvelteNeck demonstrates a significant advantage in inference speed and efficiency:

Table 2.

Comparative Performance on TrashCan Dataset.

- Speed and Efficiency: SvelteNeck achieved a remarkable 32% increase in FPS across both YOLOv8 (66.1 → 87.2 FPS) and YOLO11 (54.2 → 71.6 FPS) backbones. Crucially, on YOLO11, the latency dropped significantly from 14.3 ms to 9.7 ms, supporting our claim that SvelteNeck mitigates the memory-access bottlenecks.

- Accuracy: Despite the substantial speedup and reduced computational cost (lower GFLOPs), SvelteNeck maintains competitive accuracy. On YOLOv8, it even slightly improved mAP50–95 (0.699 vs. 0.694), while on YOLO11, the performance drop was negligible (0.701 vs. 0.691), ensuring reliable detection in complex underwater environments.

While SvelteNeck significantly improves Recall on the TrashCan dataset, we observe a minor decrease in Precision and mAP at higher IoU thresholds. Specifically, when replacing YOLO11-Slim-Neck with YOLO11-SvelteNeck, Recall increases from 0.851 to 0.859, whereas Precision decreases from 0.887 to 0.847 and mAP50–95 slightly drops from 0.701 to 0.691. A similar trend is observed on YOLOv8 (Precision: 0.873 → 0.837; Recall: 0.848 → 0.857). This behavior is expected for recall-oriented designs: enhancing sensitivity to small, occluded, or low-contrast targets reduces false negatives but may introduce additional false positives from background clutter (e.g., marine snow and turbulence), leading to a modest Precision drop. Moreover, mAP50–95 is more sensitive to localization uncertainty in degraded underwater imagery, which can cause a small reduction even when mAP50 remains competitive. In practical deployment, the operating point can be tuned by adjusting the confidence/NMS thresholds to balance Precision–Recall according to mission requirements; in underwater cleaning scenarios, we prioritize minimizing missed detections.

3.5. Comparison with Existing Detectors on the TrashCan Dataset

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed SvelteNeck-YOLO in complex underwater waste detection tasks, we conducted comparative experiments against a variety of representative detectors under identical datasets and uniform training configurations. The comparison models include:

- General Lightweight Baselines: YOLOv8n and YOLO11n.

- Specialized Underwater/Lightweight Methods: S2-YOLO [30], SCoralDet [31], LUOD-YOLO [32], and RT-DETR-n [33]. This selection allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the trade-off between detection accuracy and deployment costs.

Specifically, S2-YOLO is an improved model for marine waste detection proposed in our previous work, based on structurally optimized YOLOv8n. SCoralDet represents a recent advancement in real-time underwater biological detection, employing efficient feature aggregation to mitigate optical noise. LUOD-YOLO incorporates Dynamic Local-Global Attention (DLGA) and Cross-Scale Feature Fusion (CCFF), serving as a state-of-the-art lightweight benchmark.

Implementation Note on RT-DETR-n:Since the official RT-DETR repository does not offer a “nano” scale configuration, we designed a custom variant, RT-DETR-n, to ensure a fair comparison with the YOLO-n series. This model applies a reduced compound scaling strategy (depth = 0.75, width = 0.75, max_channels = 512) and adjusts the kernel sizes in the HGBlock (from k = 2 to k = 3) to guarantee tensor compatibility at smaller scales. This establishes a valid transformer-based baseline for this study.

To precisely evaluate model performance, Table 3 presents a detailed comparison of metrics on the test set, including Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP50, and mAP50–95.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of different detection algorithms.

The comparative results in Table 3 demonstrate that SvelteNeck-YOLO achieves the best trade-off between efficiency and accuracy, effectively balancing the constraints of embedded deployment with the demands of complex underwater detection.

In terms of computational efficiency, our model achieves the lowest GFLOPs (5.8 G) among all candidates. Compared to the latest YOLO11n (6.3 GFLOPs), SvelteNeck delivers a relative reduction of approximately 8% in computational cost while achieving higher mAP. The advantage is even more pronounced when compared to the underwater-specific SCoralDet (8.8 GFLOPs), where our model reduces the computational load by 34%. This significant decrease validates the findings in Section 3.4, confirming that the SvelteNeck architecture successfully eliminates the “Inverted Bottleneck,” preventing memory access spikes in deep layers and resulting in a truly lightweight inference process suitable for resource-constrained ROVs.

Despite its minimal computational cost, SvelteNeck-YOLO demonstrates state-of-the-art detection capability, achieving the highest mAP50 (0.900) and Recall (0.859) across all models. In the specific context of underwater waste cleaning, Recall is often more critical than Precision, as false negatives result in pollution remaining in the ecosystem. While SCoralDet shows decent precision, its significantly lower Recall (0.804) and mAP50 (0.849) on the waste dataset suggest that models optimized for specific biological textures (e.g., soft corals) may lack the generalization capability to detect diverse man-made waste. In contrast, SvelteNeck’s feature fusion mechanism demonstrates superior robustness. Furthermore, compared to the lightweight competitor LUOD-YOLO, SvelteNeck outperforms it in both mAP50 and Recall, achieving absolute gains of 1.1% and 4.4%, respectively. This proves that our design achieves better feature expressiveness in complex environments without relying on excessive parameter reduction that might compromise detection sensitivity.

Finally, regarding the evolution of our methodology, the proposed SvelteNeck-YOLO represents a significant architectural optimization over our previous work, S2-YOLO. We successfully transitioned from a 6.9 GFLOPs scale model to a 5.8 GFLOPs scale model while maintaining comparable high-precision performance. By focusing on actual inference efficiency and high-recall detection rather than just theoretical parameter counts, SvelteNeck-YOLO establishes itself as the most practical and robust solution for real-time underwater waste cleaning missions among the evaluated general-purpose and specialized detectors.

3.6. Ablation Study

To strictly verify the individual contributions of the proposed Efficient Heterogeneous Spatial-Channel Split Projection (EHSCSP) module and the Efficient Heterogeneous Convolution (EHConv) operator, we conducted a component-wise ablation study on the TrashCan dataset. Using YOLO11n as the baseline, we progressively integrated these components to evaluate their impact on detection accuracy and model complexity. The quantitative results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation study of different components on the TrashCan dataset.

First, the substitution of the original C3k2 feature extraction modules with the proposed EHSCSP yielded a significant performance boost. Specifically, the mAP50 increased by 1.3% (from 0.884 to 0.897), and notably, the Recall surged by 3.5% (from 0.818 to 0.853). Simultaneously, the model parameters dropped from 2.59 M to 2.38 M. This reduction indicates that the heterogeneous split-projection mechanism inherent in EHSCSP effectively minimizes channel redundancy while enhancing the network’s ability to capture intricate underwater waste features.

Similarly, the integration of the EHConv operator to replace Standard Convolutions proved beneficial for computational efficiency. This modification reduced the computational cost (GFLOPs: 6.3 → 6.1) while slightly improving the mAP50–95 metric (0.681 → 0.687). These results confirm that EHConv successfully mitigates the computational burden associated with spatial aggregation without compromising the receptive field required for effective detection.

Finally, the complete SvelteNeck-YOLO architecture, which unifies both EHSCSP and EHConv, achieves the optimal trade-off between efficiency and accuracy. This configuration attains the highest mAP50 (0.900) and Recall (0.859) among all variants, demonstrating that the two components work synergistically to maximize feature expressiveness. Crucially, the full model achieves the lowest complexity (5.8 GFLOPs/2.22 M Params). This result validates the core design philosophy of “SvelteNeck,” which does not merely add layers but systematically replaces heavy, redundant operators with highly efficient ones. Although Precision shows a slight decrease (0.881 → 0.847), this is a deliberate trade-off to prioritize Recall, ensuring that diverse and occluded waste targets are not missed during underwater cleaning operations.

3.7. Cross-Dataset Generalization on the URPC2019 Dataset

To further verify the generalization capability and robustness of SvelteNeck-YOLO in diverse underwater environments, we extended our evaluation to the URPC2019 (Underwater Robot Professional Contest 2019) dataset. Unlike the TrashCan dataset, which focuses on varying scales of man-made waste in open waters, URPC2019 presents a significant domain shift: it is characterized by higher turbidity, severe color distortion, and a dense distribution of small biological targets (e.g., holothurian, echinus, scallop, and starfish). This contrast allows us to rigorously test whether the proposed architectural optimizations are effective across different optical conditions and target categories.

We benchmarked SvelteNeck-YOLO against the same set of representative models: general-purpose baselines (YOLOv8n, YOLO11n), specialized underwater/lightweight detectors (S2-YOLO, SCoralDet, LUOD-YOLO), and the transformer-based RT-DETR-n. All models were retrained on the URPC2019 training set using identical hyperparameters to ensure a fair comparison. The experimental results, detailed in Table 5, demonstrate the superior adaptability of our method.

Table 5.

Cross-dataset generalization results on the URPC2019 dataset.

The experimental results on the URPC2019 dataset confirm that SvelteNeck-YOLO maintains superior robustness and efficiency even under significant domain shifts. When compared to the direct baseline YOLO11n, our model demonstrates a comprehensive improvement. Despite the challenging environment characterized by turbidity and dense biological targets, SvelteNeck achieves an absolute gain of 1.8% in mAP50 (0.743 → 0.761) and improved high-precision performance (mAP50–95: 0.439 → 0.441). Simultaneously, it delivers a relative reduction of approximately 8% in computational cost (6.3 → 5.8 GFLOPs). This proves that the architectural resolution to the “Inverted Bottleneck” issue, identified in Section 3.4, yields consistent benefits across diverse underwater domains and is not limited to specific dataset characteristics.

Regarding the trade-off between efficiency and accuracy, although YOLOv8n achieves the highest mAP50 (0.794), this performance comes at the cost of significantly higher computational complexity (8.1 GFLOPs). In contrast, SvelteNeck achieves a competitive accuracy profile with 28% lower GFLOPs (relative to YOLOv8n), making it far more suitable for battery-constrained underwater robots. Furthermore, when compared to the ultra-lightweight LUOD-YOLO, SvelteNeck achieves comparable detection performance (mAP50: 0.761 vs. 0.762, a virtually negligible difference) while maintaining a lower computational load (5.8 vs. 5.9 GFLOPs) and slightly superior high-precision metrics (mAP50–95: 0.441 vs. 0.439). This establishes SvelteNeck as the most efficient model in the sub-6.0 GFLOPs category.

Notably, SvelteNeck also exhibits superior generalization capabilities over domain-specific models. It surpasses the coral-specific SCoralDet in both accuracy (absolute gain of 0.4% in mAP50) and efficiency (relative reduction of 34% in GFLOPs). Similarly, it outperforms our previous waste-specific model S2-YOLO (mAP50: 0.761 vs. 0.753). These results indicate that SvelteNeck possesses a backbone-agnostic generalization capability, allowing it to effectively extract features from diverse biological targets (e.g., urchins, scallops) without requiring task-specific structural complexity. In summary, SvelteNeck-YOLO represents the optimal Pareto frontier, offering the best balance of lightweight deployment and robust generalization in complex underwater environments.

4. Discussion

The core contribution of this study is the resolution of the “Inverted Bottleneck” efficiency trap observed when porting the Slim-Neck architecture to modern deep detectors like YOLO11. By systematically analyzing the layer-wise Memory Access Cost (MAC), we demonstrated that the fragmented operator design of GSConv creates a “memory wall” in deep layers. The proposed SvelteNeck, utilizing the EHSCSP module and EHConv operator, successfully eliminates these redundancies. This architectural realignment is empirically validated by the superior trade-off achieved on the TrashCan and URPC2019 datasets, where the model attained the lowest computational complexity (5.8 GFLOPs) and a 32% relative increase in FPS. Notably, the model achieved the highest Recall (0.859), which is critical for underwater waste cleaning missions where missing a target (False Negative) poses a greater environmental risk than a false alarm.

Despite these achievements, we acknowledge certain limitations in the current study. First, regarding the scope of architectural validation, while the original Slim-Neck design was validated across multiple popular real-time detector architectures (e.g., YOLOv3/v4/v5/v7) and lightweight backbone variants (e.g., MobileNetV3, ShuffleNetV2), our current optimization is strictly tailored to the “Split-Stack-Aggregate” paradigm of the YOLO series. The generalizability of the EHConv and EHSCSP modules to other detector families (such as two-stage detectors or anchor-free architectures) has not yet been extensively verified. Second, the extreme lightweight design of SvelteNeck incurs a minor trade-off in high-precision metrics (e.g., mAP50–95) compared to computationally heavier baselines (e.g., YOLOv8n), suggesting that the feature discrimination capability for complex scenarios requires further enhancement.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we identified and rigorously analyzed the “Inverted Bottleneck” phenomenon in lightweight network design. To address this, we proposed SvelteNeck-YOLO, a hardware-friendly detector tailored for underwater environments. By introducing the large-kernel EHConv and the aggregation-efficient EHSCSP module, the proposed architecture successfully realigns computational cost with feature resolution. Experimental results demonstrate that SvelteNeck-YOLO achieves a state-of-the-art balance between efficiency and accuracy, delivering robust detection performance with significantly reduced latency, making it highly suitable for resource-constrained underwater platforms.

Future work will focus on expanding the architectural universality and practical deployment of the proposed method. First, to address the current limitation of YOLO-specific validation, we aim to investigate the synergistic effects of SvelteNeck with a broader range of CNN backbones (e.g., MobileNet, Swin Transformer) to verify its cross-architecture robustness. Second, we will explore advanced training strategies, such as knowledge distillation, to recover the slight precision loss observed in lightweight configurations. Finally, we plan to deploy the model on actual edge computing hardware (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson Orin) embedded in ROVs to assess its long-term stability and energy consumption in real-world marine missions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/a19020113/s1. Supplementary Material (CSV): Layer-wise complexity breakdown for four models. This file provides a layer-by-layer profiling report for YOLOv8-SlimNeck, YOLO11-SlimNeck, YOLOv8-SvelteNeck, and YOLO11-SvelteNeck (as defined in the main text). Under a unified input setting (1 × 3 × 640 × 640, single forward pass), we record for each layer/operator its FLOPs (M), Memory Access Cost (MAC, M; memory traffic/access cost rather than multiply–accumulate operations), Intensity = FLOPs/MAC, parameter count, and the input/output tensor shapes. This supplementary report is provided to support the overall complexity comparison in the manuscript and to facilitate reproducibility and identification of memory-bound bottlenecks at the operator level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W. and H.W.; Data curation, B.Y. and H.D.; Formal analysis, T.W.; Funding acquisition, H.W. and W.W.; Investigation, T.W.; Methodology, T.W.; Resources, H.W. and W.W.; Software, T.W.; Supervision, H.W. and K.Z.; Validation, T.W., H.W. and W.W.; Visualization, B.Y.; Writing—original draft, T.W.; Writing—review and editing, K.Z., B.Y. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Hainan Province (Grant No. ZDYF2024GXJS034); the Major Science and Technology Program of Yazhou Bay Innovation Institute, Hainan Tropical Ocean University (Grant No. 2023CXYZD001); the School-Level Research and Practice Project of Hainan Tropical Ocean University (Grant No. RHYxgnw2024-12); the Sanya Science and Technology Special Fund (Grant No. 2022KJCX30); the Hainan Provincial Graduate Student Innovation Research Project (Grant No. Hys2025-523); and the University-Level Graduate Innovation Research Projects of Hainan Tropical Ocean University (Grant Nos. RHDYC-202514 and RHDYC-202515).

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are from publicly available datasets. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author according to reasonable requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The specific architectural parameters for the SvelteNeck-YOLO model (Scale: n) are detailed in Table A1. The configuration corresponds to the provided yaml file in the Supplementary Materials.

Table A1.

Detailed architecture specifications of SvelteNeck-YOLO (Scale: n). The input size is set to 640 × 640. The “Arguments” column denotes [k, s, c, n], representing kernel size, stride, output channels, and number of module repetitions, respectively.

Table A1.

Detailed architecture specifications of SvelteNeck-YOLO (Scale: n). The input size is set to 640 × 640. The “Arguments” column denotes [k, s, c, n], representing kernel size, stride, output channels, and number of module repetitions, respectively.

| Stage | Module | Arguments [k, s, c, n] | Output Size (H × W × C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone | |||

| 0 | Conv | [3, 2, 16, 1] | 320 × 320 × 16 |

| 1 | Conv | [3, 2, 32, 1] | 160 × 160 × 32 |

| 2 | C3k2 | [3, 1, 64, 1] | 160 × 160 × 64 |

| 3 | Conv | [3, 2, 64, 1] | 80 × 80 × 64 |

| 4 | C3k2 | [3, 1, 128, 1] | 80 × 80 × 128 |

| 5 | Conv | [3, 2, 128, 1] | 40 × 40 × 128 |

| 6 | C3k2 | [3, 1, 128, 1] | 40 × 40 × 128 |

| 7 | Conv | [3, 2, 256, 1] | 20 × 20 × 256 |

| 8 | C3k2 | [3, 1, 256, 1] | 20 × 20 × 256 |

| 9 | SPPF | [5, 1, 256, 1] | 20 × 20 × 256 |

| 10 | C2PSA | [-, -, 256, 1] | 20 × 20 × 256 |

| SvelteNeck | |||

| 11 | Upsample | [-, 2, -, -] | 40 × 40 × 256 |

| 12 | Concat | [-] | 40 × 40 × 384 |

| 13 | EHSCSP | [5, 1, 128, 1] | 40 × 40 × 128 |

| 14 | Upsample | [-, 2, -, -] | 80 × 80 × 128 |

| 15 | Concat | [-] | 80 × 80 × 256 |

| 16 | EHSCSP | [5, 1, 64, 1] | 80 × 80 × 64 |

| 17 | EHConv | [3, 2, 64, 1] | 40 × 40 × 64 |

| 18 | Concat | [-] | 40 × 40 × 192 |

| 19 | EHSCSP | [5, 1, 128, 1] | 40 × 40 × 128 |

| 20 | EHConv | [3, 2, 128, 1] | 20 × 20 × 128 |

| 21 | Concat | [-] | 20 × 20 × 384 |

| 22 | EHSCSP | [5, 1, 256, 1] | 20 × 20 × 256 |

| Head | |||

| 23 | Detect | [nc = 80] | P3, P4, P5 Outputs |

References

- Mittal, P. A Comprehensive Survey of Deep Learning-Based Lightweight Object Detection Models for Edge Devices. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, W.; Wan, L.; Zhang, G. A Lightweight Fire Detection Algorithm Based on the Improved YOLOv8 Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Ge, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, X. Edge-Optimized Lightweight YOLO for Real-Time SAR Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, B.; Chen, M. LFRE-YOLO: Lightweight Edge Computing Algorithm for Detecting External-Damage Objects on Transmission Lines. Information 2025, 16, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, G.; Liang, S.-D.; Yang, C.; Zheng, X.; Huang, D.; He, F. An Improved Model Based on YOLO V5s for Intelligent Detection of Center Porosity in Round Bloom. ISIJ Int. 2024, 64, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Kong, M.; Yuan, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Lu, W.; Wang, R.; Yang, Q. Real-Time Underwater Object Detection Technology for Complex Underwater Environments Based on Deep Learning. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; De, S.; Gurung, S. A Survey on Underwater Object Detection. In Intelligence Enabled Research: DoSIER 2021; Bhattacharyya, S., Das, G., De, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 91–104. ISBN 978-981-19-0489-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, M.; Yang, N.; Tao, C.; Zhi, H.; Luo, H. Underwater Object Detection and Datasets: A Survey. Intell. Mar. Technol. Syst. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Cao, Z.; Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, M. It Takes Two: Multi-Frequency Perception with Complementary Fusion Network for Complex Scene Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Peng, L.; Tang, S. Underwater Object Detection Using TC-YOLO with Attention Mechanisms. Sensors 2023, 23, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Wang, X.; Miao, X.; Zhao, Q. A Review of AI Edge Devices and Lightweight CNN and LLM Deployment. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Peng, X.; Li, D.; Shi, F. YOLOv11-MSE: A Multi-Scale Dilated Attention-Enhanced Lightweight Network for Efficient Real-Time Underwater Target Detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ye, B. Edge Computing Based Electric Bicycle Dangerous Riding Behavior Detection System. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Pan, L.; Cui, H.; Zhang, L. An Improved Lightweight Tiny-Person Detection Network Based on YOLOv8: IYFVMNet. Front. Phys. 2025, 13, 1553224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, Hi, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1800–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Elhenidy, A.M.; Labib, L.M.; Haikal, A.Y.; Saafan, M.M. GY-YOLO: Ghost Separable YOLO for Pedestrian Detection. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 14907–14933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, O.E. Revisiting Convolutional Design for Efficient CNN Architectures in Edge-Aware Applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 44351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, Z.; Li, S.; Yan, L. Ghost-YOLO v8: An Attention-Guided Enhanced Small Target Detection Algorithm for Floating Litter on Water Surfaces. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 80, 3713–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.D.; Do Le, T.M. Ghost-Attention-YOLOv8: Enhancing Rice Leaf Disease Detection with Lightweight Feature Extraction and Advanced Attention Mechanisms. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tan, P. YOLO-Fast: A Lightweight Object Detection Model for Edge Devices. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Pei, H.; Zhou, D.; Qiu, J. ADP: Graph Adaptive Pooling Based on Edge Understanding with Graph Pooling Information Bottleneck. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-Neck by GSConv: A Lightweight-Design for Real-Time Detector Architectures. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, X.; Mo, Y. A Lightweight Underwater Detector Enhanced by Attention Mechanism, GSConv and WIoU on YOLOv8. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C. A Survey of Lightweight Methods for Object Detection Networks. Array 2026, 29, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.-T.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet V2: Practical Guidelines for Efficient CNN Architecture Design. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Mark Liao, H.-Y.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Y.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Yeh, I.-H. CSPNet: A New Backbone That Can Enhance Learning Capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1571–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ye, B.; Dong, H. F3M: A Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module for Robust Underwater Object Detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ye, B. An Improved YOLOv8n Based Marine Debris Recognition Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Computer Graphics, Image and Virtualization (ICCGIV), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 6–8 June 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Liao, L.; Xie, X.; Yuan, H. SCoralDet: Efficient Real-Time Underwater Soft Coral Detection with YOLO. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 85, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Pan, W. LUOD-YOLO: A Lightweight Underwater Object Detection Model Based on Dynamic Feature Fusion, Dual Path Rearrangement and Cross-Scale Integration. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.