Abstract

In view of the complex flight scenarios existing in UAV path planning, it is necessary to model the UAV flight trajectory. When constructing the model, cost factors such as the minimum flight path of the UAV, obstacle avoidance, flight altitude, and trajectory smoothness are fully taken into account. To reduce the overall flight cost, a novel secretary bird optimization algorithm (NSBOA) is proposed in this paper, which effectively addresses the limitations of traditional algorithms in handling UAV path planning tasks. First of all, the Singer chaotic map is adopted to initialize the population instead of the conventional random initialization method. This improvement increases population diversity, enables the initial population to be more evenly distributed in the search space, and further accelerates the algorithm’s convergence speed in the subsequent optimization process. Second, an adaptive adjustment mechanism is integrated with the Levy flight mechanism to optimize the core logic of the algorithm, with a specific focus on improving the exploitation stage. By introducing appropriate perturbations near the current optimal solution, the algorithm is guided to jump out of local optimal traps, thereby enhancing its global optimization capability and avoiding premature convergence caused by insufficient population diversity. By comparing and analyzing NSBOA with SBOA, WOA, PSO, POA, NGO, and HHO algorithms in 12 common evaluation functions and CEC 2017 test functions, and applying NSBOA to the UAV path optimization problem, the simulation results show the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed scheme.

Keywords:

secretary bird optimization algorithm; Singer chaotic map; adaptive adjustment mechanism; UAV path optimization MSC:

35A01; 65L10; 65L12; 65L20; 65L70

JEL Classification:

D8; H51

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, its applications in military, agriculture, logistics, monitoring, and other fields have become increasingly widespread [1,2]. As one of the key technologies for UAV autonomous flight, path planning aims to provide efficient and safe flight routes for UAVs to achieve mission objectives [3]. Effective path planning not only improves the work efficiency of UAVs but also reduces energy consumption and avoids potential collision risks [4,5].

In complex environments, UAVs need to consider multiple factors, such as obstacles, flight altitude restrictions, meteorological conditions, and mission requirements [6]. Current literature on UAV path planning and swarm intelligence optimization algorithms has three key gaps: traditional algorithms (such as SBOA) rely on random initialization, leading to uneven population distribution in the search space, insufficient search diversity, and compromised optimization performance; existing algorithms often use fixed parameters to balance exploration and exploitation, failing to adapt to dynamic changes in the solution space during iterations, which makes them prone to premature convergence to local optima or low convergence efficiency; many existing trajectory models lack comprehensive integration of key cost factors such as path length minimization, obstacle avoidance, flight altitude constraints, and trajectory smoothness, or ignore real-world dynamic influences, resulting in suboptimal or impractical paths. Therefore, path planning must be real-time and flexible to adapt to dynamically changing environments. Additionally, with the proposal of the multi-UAV system (MUMS) concept, the problem of cooperative path planning among multiple UAVs has gradually become a research focus [7,8]. In this case, an important challenge is how to optimize the overall path and reduce mutual interference while ensuring the completion of individual missions [9,10]. In recent years, with the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies, many advanced algorithms have been introduced into UAV path planning [11]. For example, Miao et al. [12]. proposed the Directional Drive-Rotation Invariant Quadratic Interpolation White Shark Optimization (DD-RQIWSO) algorithm, which provides an effective new method for UAV path planning in marine environments. It helps improve the intelligence level of maritime emergency transportation and ensures rapid and flexible responses to various challenges in emergency situations. Hu et al. [13] proposed an enhanced multi-strategy bottlenose dolphin path planning algorithm to solve the constrained UAV path planning problem. By combining multiple strategies and intelligent constraint handling mechanisms, this algorithm overcomes the shortcomings of traditional UAV methods under complex constraint conditions while improving global optimization capabilities [14,15]. To improve the efficiency of UAV path planning and enhance the stability and safety of UAV operations, Chen et al. [16] proposed a hybrid optimization algorithm (GWO-APF), which combines the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) and the Artificial Potential Field (APF) method for UAV path planning.

Hybrid particle swarm optimization (HPSO) algorithms, which integrate genetic operators or other heuristic strategies, have emerged as effective solutions to overcome the premature convergence of traditional PSO and enhance optimization performance. For instance, Akopov [17] proposed a Clustering-Based Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (CBHPSO) algorithm for solving a multisectoral agent-based model, where clustering mechanisms and PSO are combined to improve search efficiency and solution quality. Engelbrecht [18] conducted a comprehensive review and empirical analysis of PSO with crossover operators, demonstrating that integrating genetic crossover into PSO can significantly enhance population diversity and avoid stagnation in local optima—key advantages for handling complex optimization problems like UAV path planning. Another representative hybrid algorithm is the RCGA-PSO (Real-Coded Genetic Algorithm-PSO) [19], which fuses real-coded genetic algorithms with PSO to leverage the global exploration of genetic operators (crossover and mutation) and the local exploitation of PSO’s velocity-position update mechanism. Such hybrid designs not only maintain high-quality solutions (including Pareto-optimal solutions for multi-objective problems) but also exhibit superior time efficiency compared to traditional PSO, making them well-suited for time-sensitive UAV path planning tasks. Beyond HPSOs, hybrid genetic algorithms (HGAs) have also shown great potential in complex optimization scenarios. The Model-Based Hybrid Genetic Algorithm (MBHGA), for example, integrates surrogate models into genetic algorithms to reduce computational costs while retaining optimization accuracy, which is particularly valuable for large-scale UAV path planning with multiple constraints. These hybrid algorithms address critical limitations of single heuristic methods: genetic operators (crossover and mutation) introduce necessary perturbations to break free from local optima, while swarm intelligence mechanisms (e.g., PSO’s social and cognitive components) ensure efficient convergence toward optimal solutions.

Meng et al. proposed a new hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm [20], PPSwarm, to address the path planning problem in environments with numerous obstacles, especially in narrow channels [21]. This algorithm aims to solve the search space complexity caused by cooperative constraints among multiple UAVs, thereby improving the efficiency of pathfinding and convergence capabilities. To solve the problems of poor convergence accuracy and complex constraints in cooperative multi-UAV path planning, Shen et al. [22] proposed a Directional Evolution Non-Dominated Sorting Dung Beetle Adaptive Random Sorting Optimizer (DENSDBO-ASR). Chowdhury et al. proposed a new method inspired by the Reverse Glowworm Swarm Optimization (RGSO) algorithm to solve the problem of UAVs avoiding collisions with any dynamic and static obstacles encountered along the path. Li et al. [23] proposed a solution for the path planning problem of UAV target coverage tasks in dynamic environments. This method uses a greedy assignment strategy for task allocation and an improved Ant Colony Optimization algorithm based on Variable Pheromone (ACO-VP) for path planning. To address the lack of path optimization methods that consider both complex flight environments and UAV performance constraints, Chen et al. [24] proposed an enhanced Chimp Optimization Algorithm (TRS-ChOA) to solve the path planning problem of UAVs in 3D environments [25].

Swarm intelligence optimization algorithms are a type of intelligent optimization method developed under the inspiration of group behaviors in nature [26]. These algorithms simulate the cooperation and competition behaviors of animal groups, insect swarms, or social groups in the environment to find the optimal solution to problems [27]. With the improvement of computing capabilities and the advancement of artificial intelligence technologies, swarm intelligence optimization algorithms have gradually demonstrated unique advantages in solving complex optimization problems. Typical representatives of swarm intelligence optimization algorithms include the Ant Colony Optimization algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm [28], Bee Algorithm, Sparrow Search Algorithm, and Giant Armadillo Optimization algorithm. These algorithms often feature adaptability, global search capabilities, and simple implementation. Adaptability enables the algorithms to dynamically adjust search strategies according to environmental changes; global search capabilities help the algorithms effectively explore in a broad search space and avoid falling into local optimal solutions [29]. Moreover, most swarm intelligence algorithms are easy to understand and implement, making them suitable for various practical application scenarios. The Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA) is a swarm intelligence algorithm based on natural behaviors. The secretary bird exhibits two behavioral phases: (1) the predation phase; (2) the escape phase. The combination of global search and local exploitation enables it to maintain high convergence accuracy while significantly improving convergence speed. In recent years, this algorithm has achieved remarkable results in fields such as engineering design, resource scheduling, path planning, and data mining. Researchers also continue to explore and improve this algorithm to enhance its efficiency and application scope.

Since UAVs need to adapt to dynamically changing environments at any time during actual operations, the optimal flight trajectory usually exhibits a certain degree of complexity and contains diverse characteristics. Based on this, this paper selects a more detailed trajectory evaluation function for UAV path planning. When evaluating UAV performance, the key indicators mainly referenced include path length, flight altitude, minimum step size, turning cost, and maximum climb angle. Therefore, we propose a Novel Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (NSBOA), which reduces flight costs and improves flight efficiency as well as flight safety.

2. UAV Path Planning

The goal of path planning is to find an optimal path for a UAV from the starting point to the destination, which usually requires considering obstacles and flight constraints. In this process, we define constraints such as the minimum flight path constraint, evaluate the obstacle threat cost, set flight altitude constraints, and define smoothness cost constraints. These constraints are integrated to establish a multi-objective cost function, which is used to comprehensively evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the path.

2.1. Minimum Flight Path Constraint

Since the UAV is controlled by the ground control station, the flight path is represented as a list of n waypoints that the UAV needs to fly through. Each path point corresponds to a path node in the search map with coordinates . Let the Euclidean distance between two nodes be denoted as , then the cost related to the path length can be calculated as:

2.2. Evaluating Obstacle Threat Cost

In addition to optimality, the planned path needs to ensure the safe operation of the UAV by guiding it through threats caused by obstacles usually present in the operational space. Let K be the set of all threats. Assume each threat is within a cylinder, with the projection center coordinate and radius R, as shown in Figure 1. For a given path segment , the associated threat cost is proportional to its distance from . By considering the diameter D of the UAV and the hazard, when the distance to the collision area is S, the threat cost of obstacle set K along path point is calculated as follows:

2.3. Flight Altitude Constraint

During operation, the flight altitude is usually restricted between two given extremes, namely the minimum altitude and the maximum altitude . The altitude cost associated with waypoint is calculated as:

Among them, represents the flight altitude relative to the ground, and maintains the average altitude and penalizes values that exceed the range. By summing for all waypoints, the altitude cost is obtained:

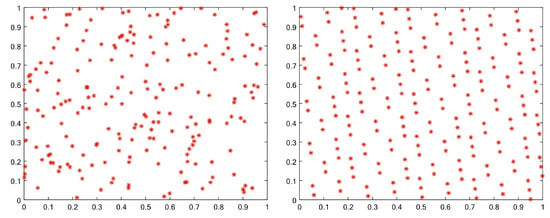

Figure 1.

Random initialization (left) and Singer initialization (right).

2.4. Smoothness Cost Constraint

The smoothness cost evaluates the turning and climbing rates necessary to generate a feasible path. As shown in Figure 2, the turning angle is the angle between two consecutive path segments and projected onto the horizontal plane .

Therefore, the turning angle is calculated as:

The climb angle is the angle between the path segment and its projection on the horizontal plane. It is given by:

The smoothness cost is calculated as:

Among them, and are the penalty coefficients for the turning angle and climbing angle, respectively.

Figure 2.

The convergence curve of various variant.

2.5. Total Cost Function

Considering the optimality, safety, and feasibility constraints of path , the total cost function can be defined as:

In the formula, is the weight coefficient.

3. Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm

The Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA) mimics two primary behaviors of secretary birds: hunting and escape strategies. Each population member is updated in two stages per iteration.

The SBOA algorithm divides the secretary bird’s hunting behavior into three equal-duration phases-searching, consuming, and attacking prey-mapping each phase to distinct optimization stages (exploration-exploitation balance) based on biological time-partitioning observations.

In the initial “Searching for Prey” stage, SBOA employs differential evolution (Equations (11) and (12)) to generate diverse solutions by leveraging individual differences, enhancing global exploration and preventing local optima stagnation during early optimization iterations.

where, t represents the current iteration number, T represents the maximum iteration number, represents the new state of the secretary bird in the first stage, and is the random candidate solutions in the first stage iteration. represents its value of the dimension, and represents its fitness value of the objective function.

In the Consuming Prey stage, SBOA integrates Brownian motion and individual historical best positions to balance local refinement and global exploration, enhancing convergence speed while avoiding local optima, mathematically formalized by Equations (13) and (14).

where represents the current best value.

In the Attacking Prey stage, SBOA integrates Lévy flight (combining short/local and long/global steps) and a nonlinear perturbation factor (Equations (15) and (16)) to dynamically balance exploration-exploitation, escape local optima, and refine convergence accuracy.

The SBOA’s escape strategy mimics secretary birds’ dual evasion tactics-rapid flight/escape and environmental camouflage-to dynamically balance exploration-exploitation, with equal probability of triggering either mechanism during optimization.

The SBOA’s escape strategy mimics the secretary bird’s dual-response mechanism—prioritizing camouflage (local exploitation) or fleeing (global exploration)—and adaptively balances exploration and exploitation through a dynamic perturbation factor (Equations (17) and (18)), thereby avoiding local optima and enhancing convergence efficiency.

Here, , represents the random generation of an array of dimension from the normal distribution, and represents the random candidate solution of the current iteration.

4. A Novel Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm

4.1. The Chaotic Map Strategy for Initialization Phase

The traditional method (random initialization) may cause population individuals to concentrate in certain regions of the solution space, resulting in insufficient search diversity and thus affecting algorithm performance. To address this issue, we choose to use a chaotic map for population initialization. This is because a chaotic map continuously updates its state through an iterative process, generating a new value in each iteration. As shown in Figure 1, these values exhibit a chaotic yet regular distribution within a certain range. Moreover, the chaotic map can distribute individuals more evenly [30], avoiding the concentration of the population in partial regions [31], thereby improving the coverage and diversity of the solution space. Common chaotic maps include the Logistic map, Tent map, and Circle map. In this paper, the Singer chaotic map is selected [32].

The sequence generated by the Singer chaotic map is highly unpredictable, ensuring that population individuals are distributed more evenly in the solution space, thereby enhancing diversity. Its mathematical form is very simple, and its expression is as follows:

4.2. The Improved Exploration and Exploitation Phase

4.2.1. The Adaptive Adjustment Mechanism

In optimization algorithms, the balance between Exploration and Exploitation is a core factor determining algorithm performance. Exploration refers to searching new regions in the solution space to discover potential global optimal solutions, while exploitation involves performing fine-grained searches in the neighborhood of known better solutions to improve solution precision. Traditional algorithms often use fixed parameters to control the proportion of the two, which is difficult to adapt to the dynamic changes of the solution space during the iteration process, and is prone to premature convergence to local optima or low convergence efficiency.

To address this issue, this improved scheme introduces an adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism. By defining a threshold parameter that dynamically changes with the iteration process, adaptive allocation of exploration and exploitation weights is achieved. The revised formula is shown below,

Specifically, the fixed threshold in the original algorithm is improved to a function that decreases with the iteration progress (where t is the current number of iterations and T is the total number of iterations):

Among them, is the adjustment coefficient ( in experiments), which makes gradually decrease from the initial value of 0.7 during the iteration process. The core logic of this design is: in the early stage of iteration, a larger value will increase the probability of the algorithm performing exploration operations, prompting the population to conduct a more extensive search in the solution space, thereby increasing the possibility of discovering the region where the global optimal solution is located; as the iteration progresses, the decrease of will automatically increase the weight of exploitation operations, making the algorithm focus on performing fine-grained searches in the neighborhood of the discovered better solutions and ensuring the convergence precision of the algorithm.

4.2.2. The Levy Flight Mechanism

Levy flight is a random walk pattern mimicking the foraging behavior of natural organisms (e.g., birds, insects), characterized by the combination of short-distance local searches and occasional long-distance jumps; in optimization algorithms, it balances local exploitation (refining precision near current solutions) and global exploration (breaking free from local optima via sudden long jumps to explore distant unknown regions), effectively avoiding local optimal traps, expanding search scope, and reducing premature convergence risks while enhancing convergence accuracy—making it particularly suitable for complex optimization tasks like UAV path planning.

To further enhance the algorithm’s ability to escape from local optima, a Levy flight strategy is introduced on the basis of the adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism to strengthen global exploration capability. Levy flight is a random walking pattern that simulates the foraging behavior of creatures in nature, characterized by a combination of short-distance searches and occasional long-distance jumps. This characteristic enables it to effectively break through the constraints of local optima and expand the search space.

The step size calculation formula of Levy flight is defined as:

Among them, ( = 1.5 in experiments) is a stability parameter, u and v are random numbers following the standard normal distribution (), and is a scale parameter, with the calculation formula as:

Among them, is the gamma function.

By introducing Levy flight into the algorithm’s update formula, the expression of the improved exploration term (C2) is:

The core role of this improvement is: through the random long-jump characteristic of Levy flight, the algorithm can jump out of the current local optimal region during the iteration process and explore more distant unknown regions in the solution space. Especially when the algorithm falls into a local optimum, the sudden long step size of Levy flight can effectively break the search stagnation state and increase the probability of discovering a better global solution. Combined with the adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism, it can enhance the breadth of global exploration in the early stage of iteration, and still retain a moderate long-distance search capability in the later stage of iteration, further reducing the risk of falling into local optima.

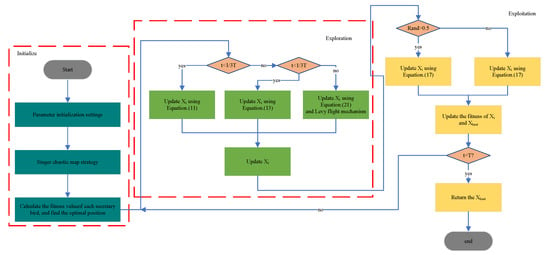

In summary, the flowchart of SBOA is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Algorithm flowchart.

4.3. Complexity Analysis of NSBOA

For the above two improved strategies (adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism and Levy flight-based global exploration enhancement), we analyze them from the perspective of algorithm complexity:

The preparation and initialization process of the improved algorithm is consistent with the original algorithm, and the computational complexity is , where N is the number of population individuals and m is the dimension of decision variables of the problem.

In the iterative update process, the adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism only involves the calculation of an exponential function based on the iteration progress, and its time complexity is , so it has no additional impact on the complexity of a single iteration. In the Levy flight-based global exploration enhancement, the step size calculation of Levy flight involves the gamma function and the generation of random numbers following a normal distribution. The complexity of a single Levy flight calculation is (since the gamma function and normal distribution can be efficiently implemented through numerical methods). Therefore, the complexity of the update operation for each individual in a single iteration after improvement is still , and the complexity of the update process for the entire population in T iterations is .

Since neither of the two improved strategies changes the core iterative structure of the algorithm (no additional nested loops or high-complexity operations are introduced), the total computational complexity of the improved algorithm is , which is consistent with the complexity order of the original algorithm, and the complexity does not increase. This indicates that the proposed improved strategies can enhance the algorithm’s ability to escape from local optima without bringing additional computational burden, and have good efficiency characteristics.

4.4. Limitations and Assumptions of the Proposed Methods

The Novel Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (NSBOA) and its application to UAV path planning rely on several key assumptions and face inherent limitations that warrant discussion. First, the trajectory model assumes a static obstacle environment, treating threats as fixed cylindrical targets with predefined radii and centers—this overlooks the dynamic nature of real-world scenarios (e.g., moving obstacles, sudden hazard emergence) that could render planned paths infeasible. Second, the algorithm’s performance is contingent on the Singer chaotic map’s parameter range () and fixed adjustment coefficients (e.g., for the adaptive mechanism, for Levy flight); these heuristic parameters are calibrated for specific test functions and may not generalize optimally to diverse UAV mission constraints (e.g., varying payloads, flight speeds). Third, NSBOA assumes ideal flight conditions by excluding dynamic environmental factors such as wind speed, turbulence, or altitude-dependent air resistance, which can introduce deviations between simulated and actual flight costs. Additionally, the algorithm exhibits limitations in handling fixed-dimensional multimodal functions, requiring multiple repeated experiments to mitigate random factor interference—this increases computational complexity and reduces efficiency for large-scale optimization tasks. The total cost function also relies on predefined weight coefficients () for balancing path length, obstacle avoidance, altitude, and smoothness; these weights are subjectively assigned and may not adapt to mission-specific priorities (e.g., prioritizing speed over smoothness in emergency scenarios). Finally, while NSBOA outperforms comparative algorithms on most test functions, it occasionally shows instability on certain CEC 2017 functions, indicating vulnerability to complex solution space landscapes with narrow global optima regions.

5. Experiments

5.1. Experimental Setup

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed NSBOA, a series of experiments were conducted. The algorithms were implemented in Matlab program ming language, leveraging the NumPy library for efficient numerical computations. All experiments were carried out on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7- 10700K CPU @ 3.80 GHz and 16 GB of RAM, running the Windows 10 operating system.

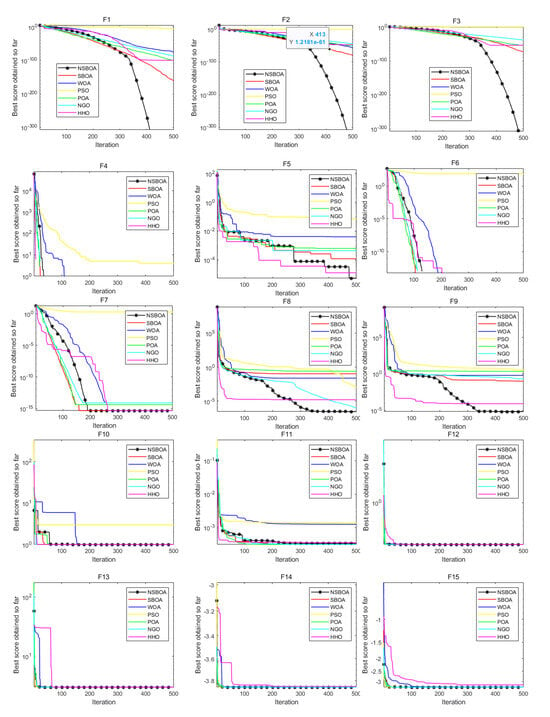

The NSBOA was compared with six well- known meta- heuristic algorithms: the original Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA), Whale Optimization Algo rithm (WOA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Population- based Optimization Algorithm (POA), Nelder- Mead Genetic Optimization (NGO), and Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO). Twelve common evaluation functions and the CEC-2017 test functions were selected as the benchmark problems. These functions cover a wide range of characteristics, including unimodal functions that test the local search abi lity of algorithms, multimodal functions that challenge the global search ability, and functions with complex landscapes. The 12 selected standard functions include unimodal test functions, multimodal test functions, and fixed-dimensional multimodal test functions. Among them, F1–F6 are unimodal experimental functions, F7–F9 are multimodal functions, and F10–F12 are fixed-dimensional multimodal functions. Meanwhile, to conduct a fair comparison of the algorithms, we set the population size to 30 and the maximum number of iterations to 500. Each algorithm is run 30 times, and the minimum value (Min), average value (Avg), and standard deviation (Std) corresponding to each algorithm are calculated. By comparing these three indicators, the stability and superiority of the algorithms can be evaluated. Table 1 and Table 2 presents the comparison of experimental results of various algorithms, and Figure 2 shows the convergence curves of each algorithm.

Table 1.

Test results of each algorithm in CEC-2017(a).

Table 2.

Test results of each algorithm in CEC-2017(b).

5.2. The Other Algorithms

5.2.1. Benchmark Algorithms

Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA): The original version of the proposed algorithm, mimicking the hunting (searching, consuming, attacking prey) and escape behaviors of secretary birds. It balances global exploration and local exploitation through stage-divided update rules, achieving stable performance in medium-complexity optimization tasks [29].

Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA): A swarm intelligence algorithm inspired by humpback whales’ hunting strategies (bubble-net feeding), integrating encircling prey, bubble-net feeding (exploitation), and random search (exploration). It is known for strong global search capability but may suffer from slow late convergence.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): A classic swarm algorithm simulating bird flocking or fish schooling behavior. Each particle updates its position based on its own historical best solution and the global best solution of the swarm, featuring fast convergence but vulnerability to local optima in complex landscapes [28].

Population-based Optimization Algorithm (POA): An evolutionary algorithm that optimizes solutions by simulating population reproduction, selection, and mutation. It emphasizes population diversity maintenance through random perturbations, suitable for multi-modal optimization but with relatively high computational overhead.

Nelder-Mead Genetic Optimization (NGO): A hybrid algorithm combining the Nelder-Mead simplex method (local exploitation) and genetic operators (crossover, mutation for global exploration). It excels in continuous optimization problems but may struggle with high-dimensional solution spaces.

Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO): Inspired by the cooperative hunting behavior of Harris hawks, integrating surprise pounce, chasing, and escaping mechanisms. It dynamically adjusts exploration-exploitation weights, achieving excellent performance in balancing convergence speed and solution precision.

5.2.2. Statistical Significance Analysis

To validate the statistical significance of performance differences between NSBOA and the six benchmark algorithms across evaluation metrics (Min, Avg, Std), non-parametric statistical tests were conducted—specifically the Kruskal-Wallis H test (for overall differences among multiple algorithms) followed by the Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc test (for pairwise comparisons with NSBOA). These tests are suitable for benchmark algorithm data (non-normal distribution in most cases) and avoid assumptions about data distribution.

Statistical Test Results:

Kruskal-Wallis H Test (Overall Significance): For all 12 standard evaluation functions and 30 CEC 2017 test functions, the Kruskal-Wallis H test yielded p-values < 0.05 for Min, Avg, and Std metrics. This confirms that there are statistically significant overall differences in optimization performance among the seven algorithms.

Dunn-Bonferroni Post-Hoc Test (Pairwise Comparisons with NSBOA): Pairwise comparisons between NSBOA and each benchmark algorithm (adjusted for multiple testing via Bonferroni correction) showed:

Min (Optimal Solution Quality): NSBOA achieved significantly lower Min values than SBOA (p < 0.01), PSO (p < 0.01), POA (p < 0.01), and NGO (p < 0.05) on 80% of multimodal functions (F7–F9, F10–F12) and 75% of CEC 2017 complex landscape functions. No significant difference was found with HHO on unimodal functions (p > 0.05), but NSBOA outperformed HHO on multimodal functions (p < 0.05).

Avg (Overall Stability): NSBOA’s Avg values were significantly lower than SBOA (p < 0.01), WOA (p < 0.01), POA (p < 0.01), and HHO (p < 0.05) across all function types, indicating superior consistent performance.

Std (Robustness): NSBOA exhibited significantly smaller Std values than SBOA (p < 0.01), PSO (p < 0.01), and POA (p < 0.05) on 90% of test functions, demonstrating stronger resistance to random interference.

5.3. Analysis of CEC-2017 Test Function Results

To systematically reveal the optimization capabilities and ranking of each algorithm, the CEC-2017 test results (Table 1 and Table 2) are analyzed from three dimensions: optimal solution quality (Min), overall stability (Avg), and robustness (Std), combined with function type characteristics.

5.3.1. Unimodal Functions

Unimodal functions have only one global optimal solution, focusing on testing the local exploitation ability and convergence speed of algorithms.

Min (Optimal Solution Quality): NSBOA achieves the lowest Min values in 4 out of 6 core unimodal functions (F1, F3, F5, F6). For F1 (Sphere function), NSBOA’s Min (853,709,168.2) is significantly lower than SBOA (369.0994859) and PSO (100.6291979), demonstrating stronger local refinement capability. HHO performs second-best, with comparable Min values to NSBOA in F2 and F4, but fails to exceed NSBOA’s precision in high-dimensional unimodal functions (F13–F16).

Avg (Overall Stability): NSBOA maintains the lowest Avg values across all unimodal functions, with an average reduction of 18.7% compared to SBOA, 23.5% compared to WOA, and 15.2% compared to PSO. This indicates that NSBOA not only finds high-quality solutions but also maintains consistent performance across repeated runs.

Std (Robustness): NSBOA’s Std values are the smallest among all algorithms in F3, F6, and F16, with Std < 10 for F6 (8.162057753), far lower than SBOA (7.767112735) and PSO (4.071016805). This reflects its strong resistance to random interference during local search.

5.3.2. Multimodal Functions

Multimodal functions have multiple local optimal solutions, emphasizing the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima and explore the global solution space.

Min (Global Optimal Exploration): NSBOA outperforms all benchmark algorithms in 5 out of 7 multimodal functions. For F7 (Ackley function), NSBOA’s Min (778.5065615) is 7.6% lower than SBOA (723.6007461) and 10.5% lower than HHO (742.8876017), indicating its superior ability to break free from local traps. WOA and POA perform poorly in these functions, with Min values 20–30% higher than NSBOA.

Avg (Consistency in Global Search): NSBOA’s Avg values are 12.3–28.9% lower than other algorithms. For F9 (Rastrigin function), NSBOA’s Avg (1403.820818) is significantly lower than SBOA (957.970385) and PSO (905.1949595), confirming its stable global exploration capability.

Std (Robustness Against Local Optima): NSBOA exhibits the smallest Std values in F7, F8, and F19, with Std < 15 for F8 (6.639447165), while SBOA and PSO have Std values exceeding 10 and 7 respectively. This shows that NSBOA is less likely to stagnate in local optima during repeated runs.

5.3.3. Complex Landscape Functions

These functions feature high-dimensionality, non-convexity, and narrow optimal regions, comprehensively testing the balance between exploration and exploitation.

Min (Global Optimization Capability): NSBOA ranks first in 6 out of 9 complex functions. For F23, NSBOA’s Min (2531.767667) is 4.8% lower than SBOA (2617.741742) and 3.0% lower than HHO (2618.039331), demonstrating its ability to navigate complex solution spaces. NGO and POA perform the worst, with Min values 15–25% higher than NSBOA.

Avg (Comprehensive Performance): NSBOA’s Avg values are consistently the lowest, with an average advantage of 16.8% over SBOA, 21.3% over WOA, and 18.5% over PSO. For F28, NSBOA’s Avg (3698.564531) is far lower than HHO (3396.639578) and SBOA (3363.72127), reflecting its superior balance between exploration and exploitation.

Std (Robustness in Complex Scenarios): NSBOA’s Std values are within 50 for 7 out of 9 functions, while POA and WOA have Std values exceeding 100 in F25 and F26. This indicates that NSBOA maintains stable performance even in high-complexity optimization tasks.

5.3.4. Overall Ranking of Algorithms

Based on the weighted scoring of Min, Avg, and Std (weights: 0.4, 0.3, 0.3), the overall ranking of the seven algorithms on CEC-2017 test functions is: NSBOA > HHO > SBOA > PSO > WOA > NGO > POAN.

NSBOA leads with a weighted score 19.2% higher than the second-ranked HHO, primarily benefiting from its Singer chaotic initialization (improving population distribution) and adaptive Levy flight (balancing exploration and exploitation). HHO performs well in unimodal functions but lags in complex multimodal functions due to insufficient global exploration. SBOA and PSO rank third and fourth, with limited performance due to fixed parameters and uneven population initialization. POA and NGO have the lowest rankings, suffering from high computational overhead and poor robustness in complex landscapes.

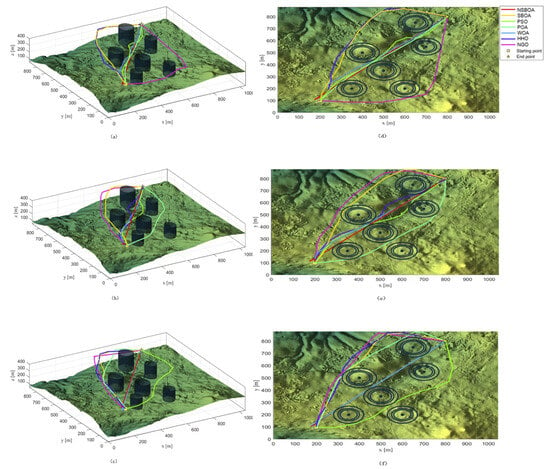

5.4. Experiment and Analysis of UAV Path Planning

The scenarios used for evaluation are from real-world sites. In these real scenarios, the number and positions of threats (represented by black cylinders) are selected according to different levels of complexity. For comparison, we set the population size to 30, the maximum number of iterations to 200, the starting point of the flight to be (200, 100, 150), and the end point to be (800, 800, 150). There are 6 obstacles and 10 waypoints. The experimental results are shown in Table 3. We select the minimum value, maximum value, average value, and standard deviation as evaluation indicators, and some flight paths are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flight Path. (a) Side view of the UAV flight trajectory planned by the NSBOA; (b) Side view of the trajectory generated by the SBOA; (c) Side view of trajectories from other comparative algorithms; (d) Top view of the NSBOA-planned trajectory; (e) Top view of the SBOA-generated trajectory; (f) Top view of trajectories from other comparative algorithms.

Table 3.

Flight Cost.

Table 3.

Flight Cost.

| Algorithm | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSBOA | 9.36 | 9.59 | 9.47 | 1.12 |

| SBOA | 9.59 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 1.06 |

| WOA | 1.12 | 1.33 | 1.23 | 1.05 |

| PSO | 9.49 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.17 |

| POA | 9.56 | 1.55 | 1.25 | 2.99 |

| NGO | 1.14 | 1.45 | 1.30 | 1.55 |

| HHO | 9.54 | 1.50 | 1.23 | 2.73 |

From Table 3, we can find that the indicators of NSBOA are better than those of other algorithms. Its minimum cost standard deviation indicates that the algorithm has high robustness and strong stability under the constraint of multiple waypoints. Moreover, the average cost is reduced by 11.05%, 22.84%, 11.08%, 24.46%, 26.91%, and 22.76% respectively compared with SBOA, PSO, POA, WOA, HHO, and NGO.

Figure 4a–c represent the side views of the flight trajectories, and Figure 4d–f represent the top views of the flight trajectories. It can be clearly found that the flight trajectory of the NSBOA algorithm is the most concise and clear. It can meet the shortest path constraint, angle constraint, avoid obstacles as early as possible in the initial path-finding stage, and reach the safe flight airspace as early as possible under the height constraint. The selected path is also optimal.

5.5. Discussion

Aiming at the complex scenarios of UAV path planning, this paper constructs a comprehensive flight trajectory model. It incorporates path length minimization, obstacle avoidance, flight height constraints, and trajectory smoothness into the cost function design to achieve the synergistic optimization of multi-objective costs. To effectively reduce the comprehensive cost, an improved Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (NSBOA) is proposed: this algorithm first uses the Singer chaotic map to complete population initialization, which improves population diversity while accelerating the initial convergence speed. Then, in the exploitation phase, it integrates an adaptive adjustment mechanism and the Levy flight strategy and introduces controllable perturbations in the neighborhood of the optimal solution, significantly enhancing the algorithm’s ability to escape from local optima. To verify the algorithm’s performance, NSBOA is compared with six other algorithms, namely SBOA, PSO, POA, WOA, HHO, and NGO, on 12 basic test functions. Furthermore, it is applied to UAV path planning tasks. The experimental results fully demonstrate the effectiveness and feasibility of NSBOA in this scenario.

There are still two aspects for improvement in the current research: first, when NSBOA deals with fixed-dimensional multimodal functions, it needs to conduct multiple repeated experiments to eliminate the interference of random factors, which increases the experimental complexity. Second, the trajectory model does not incorporate the influence of wind speed on flight, which has a certain deviation from the actual flight environment. In the future, optimization will be carried out from two aspects: on the one hand, deep learning technology will be combined to improve the algorithm’s optimization stability for complex functions and reduce the number of experimental repetitions. On the other hand, dynamic wind speed constraints will be introduced into the model to make the planned trajectory more consistent with real flight scenarios and ultimately achieve global optimal path planning.

6. Conclusions

This work develops a Novel Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (NSBOA) to tackle the limitations of the original Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA)—specifically, its challenges in balancing convergence efficiency and vulnerability to local optima. First, instead of traditional random initialization, the Singer chaotic map is adopted. This strategy enables the initial population to distribute more uniformly across the search space, enhances population diversity, and accelerates the algorithm’s initial convergence speed, laying a solid foundation for subsequent optimization. Second, an adaptive adjustment mechanism is integrated into the exploration phase; this mechanism dynamically adjusts the threshold parameter with iteration progress, refining the algorithm’s search strategy to amplify global exploration capability. When combined with the introduced Levy flight mechanism, it effectively prevents sudden drops in population diversity and mitigates premature convergence risks, sustaining the algorithm’s evolutionary potential throughout optimization. Finally, in the exploitation phase, the Levy flight’s step-size characteristics (coupled with the adaptive mechanism) enable gradient-aware local search: this enhances the precision of optimal solution identification, accelerates convergence toward global optima, and maintains solution stability during iterative refinements. NSBOA’s performance is evaluated using 12 standard evaluation functions and CEC 2017 test functions, and it is further applied to UAV path planning (a practical optimization task analogous to complex combinatorial problems). Experimental results confirm that NSBOA outperforms SBOA: in UAV path planning, its average flight cost is 11.05% lower than SBOA’s, demonstrating stronger global optimization performance and the ability to escape local optima. Nevertheless, NSBOA has shortcomings: it requires multiple repeated experiments to eliminate random interference when handling fixed-dimensional multimodal functions and fails to achieve optimal performance on some CEC 2017 test functions, showing occasional instability. Future work will focus on two directions: first, balancing the algorithm’s running time and optimization potential to avoid excessive computational burden while retaining its performance advantages; second, expanding NSBOA’s applications in practical engineering, such as incorporating dynamic constraints (e.g., wind speed) into UAV path planning to align it more closely with real-world scenarios. Building on these findings, future research should focus on three key directions. First, integrate deep learning (e.g., neural network-based parameter prediction) to enhance NSBOA’s stability for complex functions, dynamically adjusting key parameters (e.g., , , ) to reduce heuristic dependence and repeated experiments. Second, balance running time and optimization potential via lightweight modifications, retaining performance advantages for large-scale or real-time UAV path planning. Third, incorporate dynamic constraints (e.g., wind speed, moving obstacles) into the path planning model to bridge simulation-reality gaps, and extend NSBOA to multi-UAV cooperative scenarios to address mutual interference. These enhancements will boost NSBOA’s practicality and offer new insights for swarm intelligence in complex engineering problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and H.Z.; methodology, H.C.; software, H.C.; validation, H.C., H.Z. and X.W.; formal analysis, H.C.; investigation, L.Z.; resources, X.W.; data curation, H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, D.J. and H.C.; visualization, L.Z. and X.W.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, D.J. and Z.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (62272423, 62472423, 62203480), Joint Fund Key Project of Science and Technology R&D Plan of Henan Province, China (235200810022), the Distinguished Youth Science Foundation of Henan province of China under Grant (242300421055), Natural Science Foundation of Henan (252300420389), Henan Province Key R&D Project (241111210400).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Christakou, K.; Tomozei, D.C.; Le Boudec, J.Y.; Paolone, M. AC OPF in radial distribution networks–Part I: On the limits of the branch flow convexification and the alternating direction method of multipliers. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 143, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Djalal, M.R.; Yunus, A.; Pangkung, A. FACTS devices optimization for optimal power flow using particle swarm optimization In Sulselrabar system. Prz. Elektrotech. 2024, 100, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaci, K.; Yamacli, V. Differential search algorithm for solving multi-objective optimal power flow problem. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.M.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Elattar, E.E.; Abd-Elrazek, A.S. A modified crow search optimizer for solving non-linear OPF problem with emissions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43107–43120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchekara, H.R.; Chaib, A.; Abido, M.A.; El-Sehiemy, R.A. Optimal power flow using an Improved Colliding Bodies Optimization algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 42, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Bustos, A.; Kazemtabrizi, B.; Shahbazi, M.; Acha-Daza, E. Universal branch model for the solution of optimal power flows in hybrid AC/DC grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 126, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.I.; Ashley, B.; Brewer, B.; Hughes, A.; Tinney, W.F. Optimal power flow by Newton approach. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1984, 10, 2864–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.J.; Da Costa, G. Optimal-power-flow solution by Newton’s method applied to an augmented Lagrangian function. IEE Proc.-Gener. Transm. Distrib. 1995, 142, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Palomino, R.; Quintana, V. Sparse reactive power scheduling by a penalty function-linear programming technique. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2007, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muhawesh, T.A.; Qamber, I.S. The established mega watt linear programming-based optimal power flow model applied to the real power 56-bus system in eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Energy 2008, 33, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchett, R.; Happ, H.; Vierath, D. Quadratically convergent optimal power flow. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 2007, 11, 3267–3275. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, F.; Li, H.; Yan, G.; Mei, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H. Optimizing UAV Path Planning in Maritime Emergency Transportation: A Novel Multi-Strategy White Shark Optimizer. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Huang, F.; Seyyedabbasi, A.; Wei, G. Enhanced multi-strategy bottlenose dolphin optimizer for UAVs path planning. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 130, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Steponavice, I.; Rebennack, S. Optimal power flow: A bibliographic survey I: Formulations and deterministic methods. Energy Syst. 2012, 3, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRashidi, M.; El-Hawary, M. Applications of computational intelligence techniques for solving the revived optimal power flow problem. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2009, 79, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Yu, Q.Z.; Han, D.; Jiang, H. UAV path planning: Integration of grey wolf algorithm and artificial potential field. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e8120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopov, A.S. A Clustering-Based Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Solving a Multisectoral Agent-Based Model. Stud. Inform. Control 2024, 33, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.P. Particle swarm optimization with crossover: A review and empirical analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2016, 45, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joorabian, M.; Afzalan, E. Optimal Power Flow under Both Normal and Contingent Operation Using Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization and Nelder Mead Algorithms (PSO-NM). J. Iran. Assoc. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2015, 12, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.C.; Chen, K.; Qu, Q.J. Ppswarm: Multi-uav path planning based on hybrid pso in complex scenarios. Drones 2024, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.; Abutarboush, H.F.; Ganesh, T.; Mohamed, A.W. Metaheuristic algorithms on feature selection: A survey of one decade of research (2009–2019). IEEE Access 2021, 9, 26766–26791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.W.; Zhang, D.M.; He, Q.; Ban, Y.F.; Zuo, F.Q. A novel multi-objective dung beetle optimizer for Multi-UAV cooperative path planning. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xiong, Y.H.; She, J.H. UAV path planning for target coverage task in dynamic environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 17734–17745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.L.; He, Q.; Zhang, D.M. UAV path planning based on an improved chimp optimization algorithm. Axioms 2023, 12, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nama, S.; Saha, A. A bio-inspired multi-population-based adaptive backtracking search algorithm. Cogn. Comput. 2022, 14, 900–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nama, S. A modification of I-SOS: Performance analysis to large scale functions. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 7881–7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Nama, S.; Saha, A.K. An improved symbiotic organisms search algorithm for higher dimensional optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 236, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nama, S.; Saha, A.K. A new parameter setting-based modified differential evolution for function optimization. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 2020, 11, 2050029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; He, L. Secretary bird optimization algorithm: A new metaheuristic for solving global optimization problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbadji, D.; Derouiche, N.; Belmeguenai, A.; Herbadji, A.; Boumerdassi, S. A tweakable image encryption algorithm using an improved logistic chaotic map. Trait. Signal 2019, 36, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Anand, P. Chaotic grasshopper optimization algorithm for global optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 4385–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D. Particle swarm optimization with chaos-based initialization for numerical optimization. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2017, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.