Abstract

Facial Expression Recognition (FER) is a critical component of affective computing, with deep learning models dominating performance metrics. In contrast, geometric approaches based on the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) offer explainability through using triangles aligned to facial landmarks. The notable points of these triangles capture the deformation of muscles. However, restricting the feature extraction to notable points may be suboptimal. This paper introduces a novel method for optimizing the extraction of features by searching for optimal inner points in 22 facial triangles applying three metaheuristics: Differential Evolution (DE), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Convex Partition (CP). This results in a set of 59 geometric-based descriptors that capture muscle deformation more accurately. The proposed method was evaluated using five machine learning classifiers on two benchmark databases: the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) and the Japanese Female Facial Expression (JAFFE). Experimental results demonstrate significant performance improvements. The combination of DE with a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) achieved an accuracy of on the KDEF database, while Support Vector Machine (SVM) optimized via CP attained an accuracy of on the JAFFE database. Statistical analysis confirms that optimized descriptors yield higher accuracy than previous geometric methods.

1. Introduction

Facial expressions are the most direct non-verbal channel for communicating human emotion, a capability that has been a determinant factor for the survival and evolution of humans throughout history [1]. These expressions are grounded in physiological responses to environmental stimuli [2] and involve the coordinated movement of a complex array of approximately 43 facial muscles [3]. The accurate classification of these movements is critical for applications ranging from human–computer interaction to clinical monitoring of neurological disorders [4,5]. For instance, recent studies have demonstrated the utility of analyzing regional facial information for the automatic diagnosis of facial palsy [6].

The foundational framework for analyzing facial movement is the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) proposed by Ekman and Friesen [7], which decomposes expressions into specific Action Units (AUs) corresponding to muscle contractions. While this categorical approach is standard, researchers have also explored dimensional models, such as the circular model of affect proposed by Barrett and Russell [8], which positions emotions on axes of pleasantness and activation. However, modeling the multifaceted nature of emotion computationally remains a significant challenge [9].

Regarding automated recognition, while recent advancements in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have achieved high accuracy [10], they often lack explainability. Conversely, geometric approaches that track the deformation of specific facial regions preserve the anatomical context of the analysis [11]. Standard geometric methods rely on the detection of 68 facial landmarks, a process extensively reviewed by Ouanan et al. [12].

To bridge the gap between these raw points and muscular mechanics, recent research has attempted to infer muscle activity directly from visual data. Benli and Eskil [13] utilized optical flow to track landmark displacement as a proxy for muscle features. Similarly, hybrid approaches have combined computer vision with wearable electromyography (EMG) to map muscle synergies to observable kinematics [14,15]. Building on the concept of non-intrusive muscle estimation, Arrazola et al. [5] proposed measuring the deformation of triangles anchored by the centroid to estimate muscle activation, providing a robust set of features for emotion recognition. Building on this, Aguilera et al. [11] demonstrated that the centroid is not always the most discriminative point. They improved performance by selecting the best notable point (e.g., Incenter, Fermat point, Nagel point) for each triangle from a finite set of candidates [11]. To address this limitation, the present work proposes a new method to find the optimal inner point for each triangle in a continuous search space. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms—such as Differential Evolution (DE), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Convex Partition (CP)—are used for determining the precise linear combination of vertices that maximizes the discriminative power of the geometric features. This approach generalizes previous geometric works using inner point location as a tunable parameter, thereby enhancing the performance of standard machine learning classifiers.

The emphasis on explainability in this work may justify the difference in accuracy between the proposal (which achieves 0.91 in KDEF and 0.81 in JAFFE) and the state-of-the-art deep learning methods ad hoc for each database (0.96 in KDEF and 0.98 in JAFFE) [10]. In critical application scenarios, such as clinical diagnosis aids for neurological disorders or forensic psychological assessment, the ability to validate a decision provided with explainability at the muscle level is vital, with a minimum acceptable performance threshold typically set close to 0.80 [6]. Our method fulfills this by mapping feature deformation directly to specific muscle groups, allowing results to be interpreted through the lens of anatomical dynamics rather than uninterpretable pixel-level correlations.

Section 2 briefly introduces the databases, the methodology for constructing geometric descriptors, and the optimization metaheuristics algorithm, along with evaluated machine learning classifiers. Section 3 details how metaheuristics are applied for tuning 22 FACS-consistent triangles from 68 landmarks. Section 4 reports the performance of tested strategies and utilizes the non-parametric Friedman test for statistical analysis and visual resources to discuss results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the successful deployment of the evolutionary metaheuristics, confirming that the proposed methodology yields state-of-the-art results among geometric FER approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

This section briefly describes the databases, the geometric reference framework, the machine learning, and the metaheuristic applied to FER.

2.1. Databases

Two widely recognized databases in the field of affective computing are utilized, targeting the classification of seven basic emotions: Anger, Disgust, Fear, Happiness, Sadness, Surprise, and Neutral.

- KDEF (Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces): Developed by Lundqvist et al. (1998) [16], this database consists of 4900 images of human facial expressions. The set features 70 amateur actors (35 females and 35 males). For this study, only the frontal view images are utilized to ensure consistency with the geometric landmark detection (980 images).

- JAFFE (Japanese Female Facial Expression): Created by Lyons et al. (1998) [17], this database contains 213 images of 7 facial expressions posed by 10 Japanese female models.

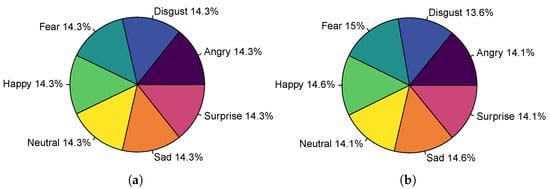

Figure 1 shows the proportion of emotions for both databases. In both cases, emotion labels are uniformly distributed, i.e., well-balanced.

Figure 1.

Proportions of emotion labels in databases: (a) KDEF and (b) JAFFE.

2.2. Face Landmarks and Facial Muscle Representation

Facial landmarks are key points that localize distinctive features of the face (e.g., eyes, eyebrows, mouth, and jawline). This work is based on the 68-point annotation scheme proposed by Kazemi and Sullivan [18], which utilizes an ensemble of regression trees to estimate face alignment. Kazemi’s geometric approach aligns with the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) [7], which states that expressions are the result of specific movements of facial muscles called Action Units (AU). Significant AUs are listed in Table 1 for further reference.

Table 1.

Kazemi’s landmarks associated with emotional AUs [11].

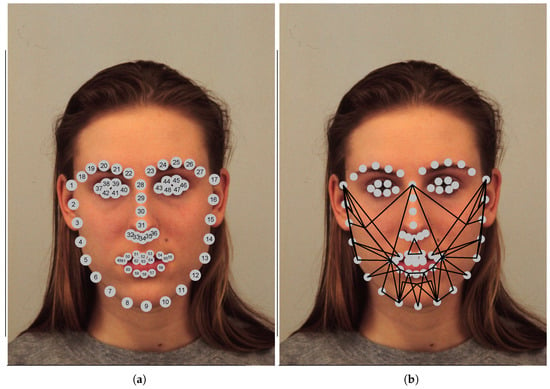

Formally, for any given picture, let be a collection of Kazemi’s face landmarks, i.e., a set of points aligned to specific parts of the face. According to [5,11], constructing triangles based on the vertex set constitutes a robust muscle representation for emotion recognition. Table 2 lists the vertices of 22 triangles manually defined to be consistent with Table 1 based on the FACS theory proposed by [7]. Figure 2 illustrates (a) the enumerated Kazemi’s Face Landmarks and (b) the proposed triangles.

Table 2.

Definition of the 22 facial triangles utilized for muscle representation. Each triangle is constructed using three vertex landmarks () from the Kazemi set or an inner point from a previously defined triangle .

Figure 2.

Visual representation of the feature extraction basis in image AF05NES from KDEF. (a) The 68 enumerated Kazemi’s facial landmarks. (b) The corresponding mesh of 22 triangles designed to capture FACS-based muscle movements.

To identify different expressions, the deformation of triangles is measured as the Euclidean distance between inner points of a pair of triangles, which represent relevant muscle groups. As fundamental geometric descriptors, the specific pairs of triangles utilized are listed in Table 3. Based on these distances, a feature vector of 59 descriptors is computed for each image. The following subsection details how these inner points are defined.

Table 3.

List of the 59 geometric descriptors employed for classification. The descriptors are computed as Euclidean distances between specific pairs of points.

2.3. Inner Points

The discriminative quality of the 59 descriptors depends heavily on the definition of the inner points within each triangle. Formally, for a triangle T defined by three vertices , any inner point can be expressed by a linear combination as follows:

The existing literature provides standard approaches for defining these points:

- Arrazola et al. [5] defines each inner point in T as the centroid of the triangle, i.e., ;

- Aguilera et al. [11] utilizes the trajectory metaheuristic of Simulated Annealing to select the best option among four notable triangle centers (Incenter, Centroid, Nagel point, or Torricelli point).

In this context, the main idea of this paper is applying continuous optimization metaheuristics to directly tune the weights , , and . This allows for an efficient search of the optimal feature extraction point to maximize the performance of machine learning methods.

2.4. Machine Learning Methods

The task of facial expression recognition is easily formulated as a supervised classification problem. Formally, for both databases, the i-th image is encoded as a vector of 59 descriptors (Table 3) associated with a known emotion label . To solve this multi-class problem in , the algorithms listed below are applied and evaluated.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM) [19]: A powerful classifier that constructs hyperplanes in a high-dimensional space to separate classes. A linear kernel is used to handle relationships in the feature space. The Support Vector Machine classifier is established using the SVC class from the sklearn.svm library. The model is configured with the following parameters:

- kernel = ‘linear’: Specifies the use of a linear kernel to create the decision boundary;

- random_state = 42: Controls the pseudo-random number generation for shuffling data to ensure reproducibility.

- Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [20]: A feedforward artificial neural network, capable of learning non-linear function approximations for the emotion descriptors. The artificial neural network is constructed using the MLPClassifier function from the sklearn.neural_network library. The specific architecture and training behavior are governed by the following parameters:

- hidden_layer_sizes = (100, 50): Defines a network with two hidden layers containing 100 and 50 neurons, respectively;

- max_iter = 500: Sets the maximum number of training iterations (epochs) to 500;

- activation = ‘relu’: Specifies the Rectified Linear Unit function for the hidden layers;

- solver = ‘adam’: Utilizes the Adam optimizer for weight adjustment;

- random_state = 42: Fixes the seed for random weight initialization.

- Decision Tree (DT) [21]: A non-parametric method that learns simple decision rules inferred from the data features. It provides high interpretability regarding which geometric distances are most critical for classification. The classification model is built using the DecisionTreeClassifier class from the sklearn.tree sublibrary. The model is defined by the following hyperparameters explicitly passed during initialization:

- criterion = ‘gini’: Uses Gini impurity to measure the quality of splits;

- max_depth = 5: Limits the tree expansion to a maximum depth of 5 to prevent overfitting;

- random_state = 42: Ensures the stochastic elements of the estimator are reproducible.

- Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [22]: A statistical method that finds a linear combination of features that characterizes or separates two or more classes of objects or events, assuming Gaussian densities. The Linear Discriminant Analysis model is instantiated using the LinearDiscriminantAnalysis class from the sklearn.discriminant_analysis library. No specific hyperparameters are explicitly defined, implying the model relies entirely on the default configuration provided by the library

- XGBoost (XGB) [23]: An efficient implementation of gradient-boosted decision trees. It is designed for speed and performance, operating by combining an ensemble of weak prediction models to produce a strong learner. The XGB model is implemented using the R library xgboost 1.7.11 with its default parameters.

To measure the effectiveness of these methods, a 5-fold cross-validation is performed using scikit-learn 1.4.1. The performance is evaluated by computing the mean accuracy across all folds, which represents the average proportion of correctly classified instances across the experimental folds. The mean accuracy is formally expressed as

where

- K is the number of folds ();

- C is the total number of emotion classes ();

- is the entry of the confusion matrix).

2.5. Optimization Metaheuristics

Consider that inner triangle points are parametric, so different geometric descriptors can be computed, and the performance of any machine learning algorithm is consequently affected. In order to improve the classification, several optimization metaheuristics are applied to discover the parameters that maximize the accuracy of each machine learning method. The optimization metaheuristics listed below share remarkable characteristics: (1) initially, they explore uniformly the space of parameters; (2) they are population-based and avoid local optima; and (3) they can be tuned with similar parameters. As shown below, their parameters are similarly tuned. For example, the population is set to 200 and the number of iterations to 50.

- Differential Evolution (DE) [24]. A population-based metaheuristic that optimizes a problem by iteratively trying to improve a candidate solution. It uses mechanisms analogous to biological evolution, such as mutation, crossover, and selection, and is particularly effective for continuous search spaces. Algorithm 1 is the basic algorithmic schema of DE. The DEoptim [25] library implements Differential Evolution (DE) for global optimization.

Algorithm 1 Differential Evolution (DE) - Require:

- Objective function accuracy, Population size

- Ensure:

- Best solution

- 1:

- Initialize population

- 2:

- while termination criteria not met do

- 3:

- for do

- 4:

- Generate trial vector using mutation and crossover

- 5:

- if then

- 6:

- 7:

- end if

- 8:

- end for

- 9:

- end while

The following parameters are used:- Maximum Iterations (itermax): The maximum number of generations/iterations for the DE algorithm, set to 50 via the control list.

- Population Size (NP): The number of population members, set to 200 via the control list.

- Crossover Probability (CR): Controls the fraction of parameter values copied from the mutant vector to the trial vector. It regulates the diversity of the population and is set to 0.5

- Differential Weighting Factor (F): A scaling factor applied to the difference vector during mutation. It controls the magnitude of the perturbation and is set to 0.8.

- Approximate function evaluations for the given parameters:.

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [26]: A computational method that solves a problem by having a population of candidate solutions, here named particles, and moving these particles around in the search-space according to simple mathematical formulae over the particle’s position and velocity. Algorithm 2 is the basic algorithmic schema of PSO.

Algorithm 2 Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) - Require:

- Objective function accuracy, Swarm size s

- Ensure:

- Best solution (global best)

- 1:

- Initialize particles and velocities for

- 2:

- while termination criteria not met do

- 3:

- for do

- 4:

- Update velocity using local best and global best

- 5:

- Update position

- 6:

- if is better than then

- 7:

- Update local best and global best

- 8:

- end if

- 9:

- end for

- 10:

- end while

The utilized pso library implements Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) via the psoptim [27] function. The experiments reported in this paper follow the parameters suggested by [28], which are summarized below.- Swarm Size (s): The number of particles in the swarm, set to 200 via the control list.

- Local Exploration Constant (c.p): Controls the particle’s tendency to return to its best-found position. The default value is .

- Global Exploration Constant (c.g): Controls the particle’s attraction to the swarm’s best-found position. The default value is .

- Approximate function evaluations for the given parameters:.

- Convex Partition (CP) [29]: A Bayesian optimization approach, which utilizes a regression tree structure to partition the search space into convex regions, allowing for efficient exploration of high-dimensional continuous spaces. Algorithm 3 is the basic algorithmic schema of CP.

Algorithm 3 Convex Partition (CP) - Require:

- An objective function

- Ensure:

- A domain partition focused on promising subsets

- 1:

- 2:

- fordo

- 3:

- Select a promising* subset G from the collectionNote: promising subset to contain extreme values of f, previously not observed

- 4:

- Remove G from

- 5:

- Split G into

- 6:

- Insert into the collection

- 7:

- end for

The CPoptim [30] library is used for executing the optimization process with the following parameters:- Maximum Function Evaluations (maxFE): The maximum number of times the objective function will be evaluated, set to 10,000.

- Sample Size (sampleSize): The size of the sample/population used in the search, set to 200.

- Approximate function evaluations for the given parameters:.

3. Proposed Method

This section details the proposed methodological framework for the Facial Expression Recognition (FER) task. The experimental pipeline can be summarized into three main stages: (1) data acquisition and preprocessing, where facial landmarks are extracted from standard databases; (2) feature extraction, where a geometric representation based on triangular regions is utilized; and (3) optimization and classification, where metaheuristic algorithms tune the geometric features to maximize the performance of various machine learning classifiers. The following subsections explain (1) how metaheuristics can be used for producing efficient descriptors and (2) details about the experiment designed for discovering the optimal combination of metaheuristics and machine learning methods.

3.1. Encoding Solutions for Metaheuristics

To implement optimization metaheuristics, firstly a proper representation of inner points consistent with Equation (1) is defined. Formally,

Definition 1.

For any pair , denotes an indexed inner point of the triangle T whose vertices are . Formally, , where

The transformation above is not bijective, but it possesses a remarkable property:

Theorem 1.

If , then is a random observation uniformly distributed inside T.

Proof.

To prove that this transformation results in a uniform distribution within the triangle, consider the following: (1) and are order statistics of uniform variables; (2) the Jacobian of the transformation of these order statistics to results in a flat Dirichlet distribution; and (3) the flat Dirichlet distribution samples uniformly on a simplex (a triangle in this case). See [31] for more details. □

This property allows us to uniformly explore the space of inner points without additional constraints on . Therefore, for each of the 22 triangles (Table 2), an inner point is determined by two parameters . Consequently, the full configuration of 22 inner points is encoded as a real vector . For a fixed machine learning method at time, the optimization problem is formulated as maximizing the mean accuracy of a nested 5-fold cross-validation as an objective function (Equation (2)) by tuning the parameter vector V.

3.2. Experimental Design

To identify the most efficient combination of optimization metaheuristics (MHs) and machine learning (ML) methods, every triad of Database , Metaheuristic , and Classifier is evaluated once. For each triad , the optimal vector of inner points is estimated via the following procedure:

- Compute Kazemi’s face landmark for each image in the database using the Dlib 2.0 library, and keep landmarks alongside the corresponding emotion labels.

- Define the objective function f that takes a vector V as a single parameter and returns the mean accuracy of the model trained and tested by a 5-fold cross-validation schema. In detail: (i) Compute the triangles and descriptors listed in Table 2 and Table 3, utilizing the kept landmarks and parameters V to define the inner points and geometric descriptors. (ii) Perform a 5-fold cross-validation schema for the model using Scikit-learn 1.4.1. The model is trained and tested five different times, ensuring every data point tested has not been used for training in the current iteration. (iii) Return the mean accuracy across the 5 folds (Equation (2)).

- Apply the optimization metaheuristic to maximize the previously defined objective function f. The feasible search space is restricted to .

4. Results and Discussion

The computational experiments were executed on a system running the Windows 11 Pro operating system, featuring an Intel Core i5-6500, 3.2 GHz. processor, and 16 GB of RAM. The core machine learning analysis, including the implementation of the classifiers and optimization procedures, was performed in Python 3.14, utilizing the scikit-learn library version 1.4.1. The overall experimental workflow, which included the coordination of the Python scripts and the generation of final summary reports and statistical analyses, was conducted by scripts written in the statistical computing language R, version 4.3. The resulting optimal accuracy for each combination is reported and discussed in this section. Table 4 and Table 5 report the mean accuracy and its corresponding standard deviation estimated by a 5-fold cross-validation for each pair for both databases. Table 6 organizes running time in minutes for each tested combination , additionally it reports the total time by column (machine learning method) and row (metaheuristic). To contrast the time efficiency of each method, Table 7 shows the average time taken in milliseconds for classifying an image.

Table 4.

Optimum mean accuracy (nested 5-fold cross-validation) reached by different metaheuristics for different machine learning methods.

Table 5.

Standard deviation of accuracy estimated by a 5-fold cross-validation for each combination of machine learning methods and optimization metaheuristics.

Table 6.

Execution time in minutes for each trained combination.

Table 7.

Average testing classification time per image in milliseconds.

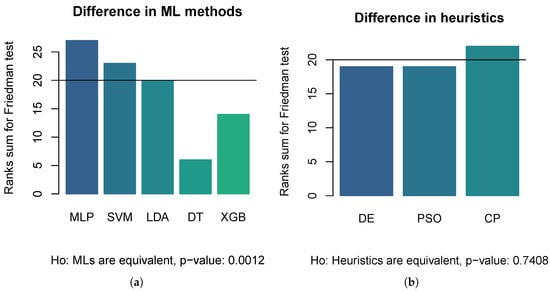

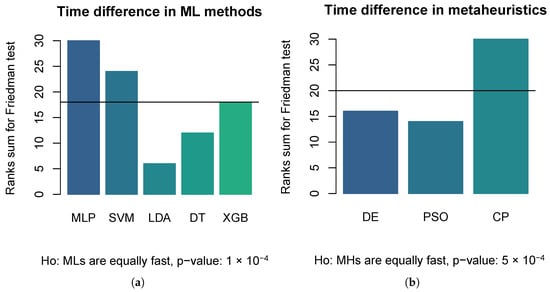

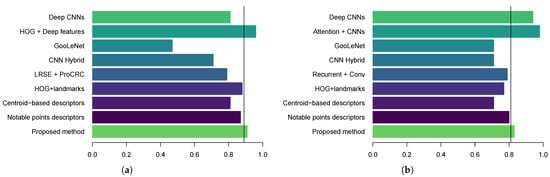

To statistically compare each combination, the non-parametric Friedman test is selected because the distribution of performance metrics did not satisfy the necessary assumptions for parametric testing, specifically regarding the lack of normality and homoscedasticity (homogeneity of variance) in samples (See Table 5). The Friedman test operates on the rank of the performance metrics rather than the raw values, making it robust against outliers and non-normal distributions, thus providing a reliable statistical basis for determining if significant differences exist between the methods. Figure 3 illustrates the results of the Friedman test through bar charts representing the sum of ranks. Figure 3a displays the comparison among machine learning methods. The test yielded a p-value of 3 , which is well below the significance threshold (). This allows us to reject the null hypothesis () that all classifiers are equivalent, confirming that the choice of classifier significantly impacts performance. As observed in the chart, MLP and SVM obtained the highest rank sums, statistically outperforming LDA, DT, and XGB. Conversely, Figure 3b compares the optimization metaheuristics. Here, the test returned a p-value of . In this case, we fail to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that there is no statistically significant difference between the performance of DE, PSO, and CP. The statistical analysis confirms that the selection of the machine learning classifier is critical (with MLP and SVM being superior choices), while the choice of optimization metaheuristic (among DE, PSO, and CP) has a negligible impact on the final model performance. Similarly, Figure 4 illustrates Friedman tests for contrasting optimizing–training time between (a) machine learning methods and (b) metaheuristics. In both cases, the hypothesis of equality is rejected: (a) MLP and SVM are significantly slower, and (b) CP is significantly slower than DE and PSO. Although metaheuristics perform approximately the same number of function evaluations 1 , CP is a surrogate-based technique, which implies additional time to estimate a latent Bayesian model at each iteration [29].

Figure 3.

Bar charts for ranks sums of Friedman tests. Each chart reports a p-value for a hypotheses: (a) All machine learning methods are equivalent in mean accuracy (5-fold cross-validation), (b) All optimization metaheuristics are equivalent in mean accuracy (5-fold cross-validation). The horizontal line marks the expected ranks sum if contrasted variables were equivalent.

Figure 4.

Bar charts for ranks sums of Friedman tests. Each chart reports a p-value for a hypotheses: (a) All machine learning methods are equally efficient in optimizing-training minutes. (b) All optimization metaheuristics are equally efficient in optimizing–training minutes. The horizontal line marks the expected ranks sum if contrasted variables were equivalent.

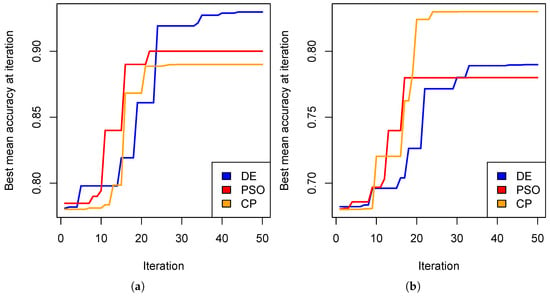

Table 4 indicates that the Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) + Differential Evolution (DE) achieved the highest performance on the KDEF database, achieving an accuracy of . Similarly, the combination of Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convex Partition (CP) demonstrated robust stability on the JAFFE dataset, achieving an accuracy of . In contrast, the Decision Tree (DT) classifier produced the lowest results, with an accuracy of on the JAFFE dataset. The Friedman test supports that the best experimental results were obtained by utilizing the MLP+DE (Accuracy: ) and SVM+CP (Accuracy: ), for KDEF and JAFFE respectively. Hence, further analysis is focused on these best models. Figure 5 shows how the mean accuracy converges for MLP and SVM during the execution of the three tested metaheuristics. These convergence charts visually exhibit the superiority of combinations MLP+DE and SVM+CP. In all cases, the metaheuristic search stops when the trend gets stuck.

Figure 5.

Convergence of the mean accuracy (nested 5-fold cross-validation) during the tuning of parameter V for (a) MLP+DE for KDEF and (b) SVM+CP for JAFFE.

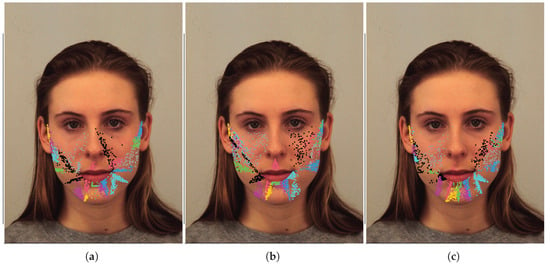

The results presented validate the hypothesis that optimizing the geometric landmark points within facial triangles significantly improves emotion recognition performance. By relaxing the constraints imposed by previous methods—which relied on fixed points like centroids [5] or a discrete selection of triangle centers [11]—the continuous optimization approach allows the model to adapt to the specific deformation dynamics of each muscle group. The superiority of the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) combined with Differential Evolution (DE), achieving an accuracy of on the KDEF dataset, suggests that this classifier is the best suited to interpret the complex geometric relationships discovered by the metaheuristic search. Comparing these findings to the state-of-the-art, the proposed method outperforms the fixed-center approaches reported by Aguilera-Hernández et al. [11] This indicates that the most informative point on a facial triangle is often an arbitrary location best found through stochastic search rather than geometric intuition. Figure 6 illustrates the best 100 sets of inner points (coded by V) found for (a) MLP+DE, (b) SVM+CP, and (c) LDA+CP. It is possible to visually state that points are not focused at the center of triangles. The distribution of points allows us to identify areas that are intuitively relevant for emotions recognition:

Figure 6.

Different sets of inner points corresponding to the best 100 vectors V found for (a) MLP+DE, (b) SVM+CP, and (c) LDA+CP. To identify each triangle, inner points are illustrated with different color.

- Mouth and Chin Region: There is a heavy concentration of points around the lips, corners of the mouth, and the chin/jawline. This region is critical for expressing emotions and it is associated with AUs 20, 25, and 26.

- Cheeks and Nasolabial Folds.: Points are distributed across the cheeks and along the nasolabial folds (the lines running from the sides of the nose to the corners of the mouth). These areas are associated with AUs 9, 6, and 12.

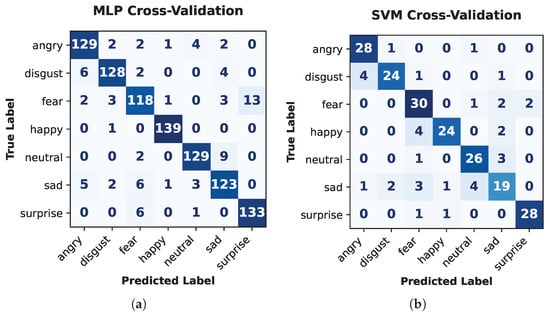

Figure 7 shows two confusion matrices for (a) MLP+DE on the KDEF database and (b) SVM+CP on the JAFFE database, respectively. Matrix (a) demonstrates superior results, marked by exceptionally high true positive counts across all emotions and very minimal confusion, with errors primarily isolated to instances like Angry/Disgust and Neutral/Sad misclassifications. In contrast, matrix (b) shows a moderate-to-high overall score; it particularly struggles with discrimination among Fear, Sad, and Surprise categories. The geometric features derived from the optimization process are more robust and distinctive on the KDEF dataset.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrices for the best models reported in Table 4: (a) MLP+DE for KDEF and (b) SVM+CP for JAFFE.

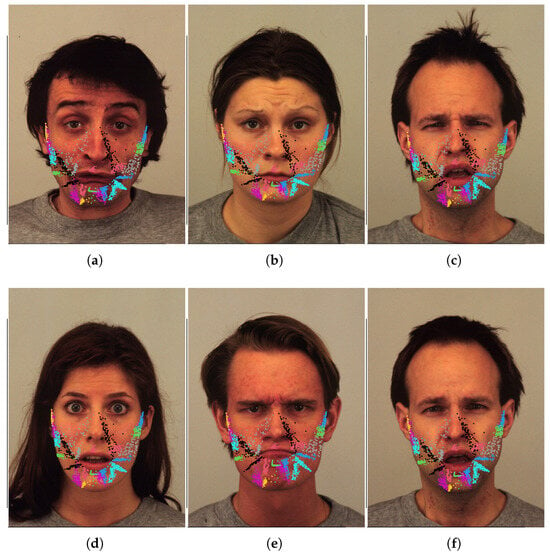

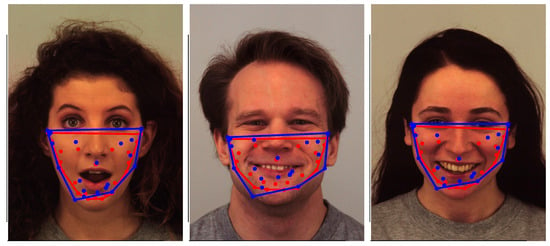

Figure 8 shows six cases of misclassification produced by the best model MLP+DE. The misclassifications shown, such as Fear being confused with Surprise or Anger with Disgust, strongly support the argument that these specific emotions are inherently ambiguous and difficult to classify, even for a high-performing model. This difficulty arises because the facial expressions share significant overlaps in their underlying muscle movements (Action Units): for example, both Fear and Surprise often involve wide eyes and an open mouth. Those errors are not mere methodological failures, but rather a reflection of the subtle individual variations and the blurring lines between emotion categories. Consider that these specific expressions would likely confuse even human observers due to their high structural similarity. The inner points added to the plots visually indicate where the model is focused, so these points may constitute a form of explainable AI (XAI). They reveal where the MLP+DE model is attending on the face—typically highlighting critical facial regions like the cheeks, mouth and chin, i.e., AUs [2]: 6, 9, 12, 20, 25, 26, etc. Observing the scatter of these points directly may help understand which specific facial features are driving the misclassification. This crucial insight then guides the design of future models by allowing developers to reinforce weights on truly discriminative features or, conversely, to ignore confounding noise in ambiguous regions.

Figure 8.

Six misclassification cases predicted by the best model (MLP+DE). Each case is listed as ‘Expected Emotion’ vs. ‘Predicted Emotion’: (a) fear vs. surprise, (b) sad vs. neutral, (c) fear vs. disgust, (d) surprise vs. fear, (e) angry vs. disgust, and (f) fear vs. disgust.

To contrast the proposed method with state-of-the-art results, Table 8 lists the accuracy scores of ten different methodologies applied to FER, divided into Deep Learning, Hybrid, and Geometric approaches. To visually compare these methodologies, Figure 9 presents bar charts of accuracy scores listed in Table 8. In the charts for KDEF and JAFFE, the proposed method, along with one or two Deep Learning models, appears in the third quartile (indicated by a vertical line). Notably, the proposed method is consistently the only geometric approach positioned in the third quartile. These results indicate that metaheuristic optimization allows geometric features to achieve competitive accuracy, despite registering lower accuracy than Deep Learning approaches.

Table 8.

Accuracy reported for state-of-the-art methods.

Figure 9.

Bar charts of accuracy for (a) KDEF and (b) JAFFE. In both charts, the 3rd quartile is marked by a vertical line.

While Figure 9 suggests that methodologies based on Deep Learning capture more discriminating information, the proposed method maintains the crucial advantage of modeling muscle action directly through continuously optimized geometric landmarks. This provides a white-box solution that explicitly validates the psychological plausibility of the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). The complexity of these attention-based deep learning models comes at the cost of explainability, whereas the proposed method remains fully transparent; it achieves competitive performance using inner points, making it a robust, computationally efficient, and highly explainable tool for emotion recognition.

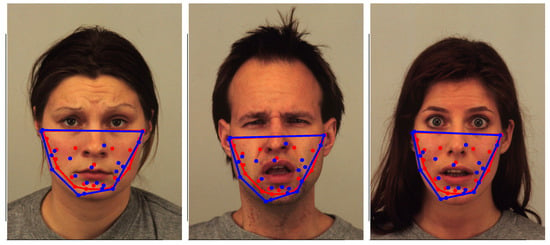

In this context, it is relevant to compare the best proposed model (MLP+DE) against another explainable geometric approach based on inner points, for instance, Arrazola et al. [5], which uses centroids as inner points. To visually contrast these last two referred methods, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show collections of images correctly classified and misclassified, respectively. In both figures, blue points locate the optimized inner points (the best proposed model MLP+DE), and red points mark the centroids. For both classes of points, the convex hull is traced with the corresponding color. The blue convex hull associated with the best proposed model covers more area than the red convex hull associated with the centroids proposed by [5]. In addition, the blue points seem to be more uniformly distributed over their corresponding convex hull. Considering the traced convex hulls in Figure 10 and Figure 11, and the triangles shown in Figure 6 and Figure 8, the proposed approach constitutes a framework to generate more powerful interpreting tools than those offered by geometric approaches merely based on central points, such as [5,11].

Figure 10.

Gallery of properly classified images with inner points and convex hull traced for the best proposed model MLP+DE (blue), and the model based on centroids [5] (red).

Figure 11.

Gallery of misclassified images with inner points and convex hull traced for the best proposed model MLP+DE (blue), and the model based on centroids [5] (red).

The proposed method based on metaheuristics is evaluated against the other strategies based on inner points under identical conditions (the same databases, 5-fold cross-validation, and classifiers) to ensure a fair comparison. Table 9 presents the mean accuracy for these three approaches across various machine learning models. The baseline strategies involve (1) using the centroid as proposed by [5], and (2) selecting the best of several notable points (centroid, incenter, Nagel, or Torricelli) as proposed by [11]. As shown, the proposed method consistently outperforms the others, demonstrating that metaheuristic optimization of inner points significantly enhances classification accuracy.

Table 9.

Mean accuracy comparison of inner-point methods under identical experimental conditions.

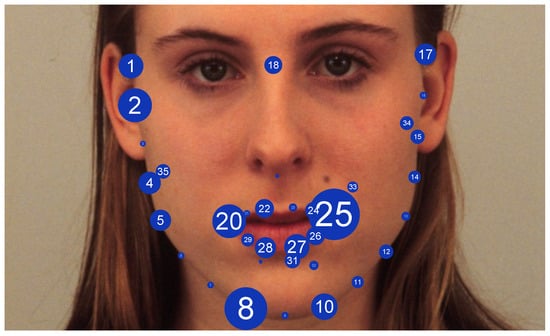

To provide a visual and explainable relation between the optimized inner points and Action Units (AUs) listed in Table 1, Figure 12 illustrates the facial landmarks where the radius of each point is proportional to the sum of the weights w assigned to it during the optimization process. This weighting scheme reflects the discriminative importance of each landmark, analogous to the loading vectors in Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which reveal the contribution of each dimension to the total variance [38]. In this context, the size of a landmark illustrates its relevance to the classification task. The points are numbered for reference. For instance, points 20 and 25 around the mouth are related to the Lip Corner Puller (AU12) and the Risorius (AU20). Similarly, points 5, 8, and 10 are associated with Jaw Drop (AU26), while points 1, 2, 17, and 18 capture the activation of the Inner Eyebrow Raiser (AU1) and the Outer Eyebrow Raiser (AU2).

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of landmark relevance. The radius of each numbered point represents the cumulative weight assigned during the optimization of inner triangle points. A larger radius indicates higher discriminative power.

5. Conclusions

The research introduces a novel approach to facial expression recognition that significantly enhances the performance of geometric-based methods through the optimization of inner triangle points. The key contributions include the following:

- Superior performance compared to traditional geometric and hybrid approaches;

- Validation of the method’s effectiveness across multiple machine learning classifiers and optimization algorithms;

- Achievement of state-of-the-art results slightly lower than deep learning FER approaches, with accuracy of 0.91 (KDEF) and 0.83 (JAFFE).

Compared to discrete geometric centers, the proposed method provides a more precise model of muscle activation, offering a high-performance, explainable alternative for FER tasks. Continuously optimizing inner points provides a more accurate representation of muscle movements, bridging the gap between raw facial landmarks and precise muscle activation modeling. Excluding deep learning approaches, the proposal improves recognition accuracy and may also help with explainability and interpretability. Currently, the inner points merely help locate relevant areas of the face. To be valuable to non-expert users, the inner points should be interpreted automatically, explaining which AUs and motions are associated. Creating a user-friendly interface that justifies each recognized emotion could contribute to the affective computing community. This paper is a first step in that direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization I.C.-A., E.G.G.d.P., A.H.-A., and M.-A.G.-R.; Investigation I.C.-A., E.G.G.d.P., A.H.-A., and M.-A.G.-R.; Formal analysis I.C.-A., E.G.G.d.P., A.H.-A., and M.-A.G.-R.; Writing—original draft, E.G.G.d.P. and I.C.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Author thanks SECIHTI and CIMAT. This work was supported by SECIHTI under project IxM-SECIHTI No. 3097-7185.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of pre-existing and publicly available datasets (JAFFE and KDEF) collected by third parties for research purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study involved the secondary analysis of publicly available datasets (JAFFE and KDEF) where informed consent was obtained by the original investigators at the time of data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in (1) KDEF https://kdef.se/ (accessed on 1 November 2025), (2) JAFFE http://www.kasrl.org/jaffe.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CP | Convex Partition |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| FACS | Facial Action Coding System |

| FER | Facial Expression Recognition |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| XGB | XGBoost |

References

- Frank, M. Facial expressions. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 5230–5234. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B.M.; Gray, J.J.; Burrows, A.M. Selection for universal facial emotion. Emotion 2008, 8, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingenbach, T.S. Facial EMG investigating the interplay of facial muscles and emotions. In Social and Affective Neuroscience of Everyday Human Interaction: From Theory to Methodology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Arrazola, M.A.; Sanchez-Yañez, R.E.; Garcia-Capulin, C.H.; Rostro-Gonzalez, H. Enhancing image-based facial expression recognition through muscle activation-based facial feature extraction. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2024, 240, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Dominguez, G.; Garcia-Capulin, C.; Sanchez-Yanez, R. Automatic facial palsy diagnosis as a classification Problem Using Regional information extracted from a photograph. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Facial Action Coding System: A Technique for the Measurement of Facial Movement; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.F.; Russell, J.A. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 805–819. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, D.C.; Zaki, J.; Goodman, N.D. Computational models of emotion inference in theory of mind: A review and roadmap. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2019, 11, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jin, K.; Zhou, D.; Kubota, N.; Ju, Z. Attention mechanism-based CNN for facial expression recognition. Neurocomputing 2020, 411, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Hernández, E.I.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Hernández-Aguirre, A.; Moya-Albor, E.; Brieva, J. Image Facial Expression Recognition based on Active Muscles and their Notable Triangle Points. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Biomedical Image Processing and Analysis, Pasto, Colombia, 19–21 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ouanan, H.; Ouanan, M.; Aksasse, B. Facial landmark localization: Past, present and future. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th IEEE International Colloquium on Information Science and Technology (CiSt), Tangier, Morocco, 24–26 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 487–493. [Google Scholar]

- Benli, K.S.; Eskil, M.T. Extraction and selection of muscle based features for facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 2014 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Stockholm, Sweden, 24–28 August 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1651–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Perusquía-Hernández, M.; Dollack, F.; Tan, C.; Namba, S.; Ayabe-Kanamura, S.; Suzuki, K. Facial movement synergies and action unit detection from distal wearable electromyography and computer vision. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 146585–146600. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, H.; Zhou, B.; Lukowicz, P. Facial muscle activity recognition with reconfigurable differential stethoscope-microphones. Sensors 2020, 20, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundqvist, D.; Flykt, A.; Öhman, A. The Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF). CD ROM Dep. Clin. Neurosci. Psychol. Sect. Karolinska Institutet 1998, 91, 630. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.; Akamatsu, S.; Kamachi, M.; Gyoba, J. Coding facial expressions with gabor wavelets. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition, Nara, Japan, 14–16 April 1998; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, V.; Sullivan, J. One millisecond face alignment with an ensemble of regression trees. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1867–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The Use of Multiple Measurements in Taxonomic Problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; KDD ’16. pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution–A Simple and Efficient Heuristic for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, K.; Ardia, D.; Gil, D.; Windover, D.; Cline, J. DEoptim: An R Package for Global Optimization by Differential Evolution. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendtsen, C. pso: Particle Swarm Optimization; R package version 1.0.4; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc, M. L’aléatoire Contrôlé en Optimisation; ISTE Group: London, UK, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- de Paz, E.G.; Vaquera-Huerta, H.; Albores-Velasco, F.J.; Bauer-Mengelberg, J.R.; Romero-Padilla, J.M. Convex Partition: A Bayesian Regression Tree for Black-box Optimisation. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2025, 196, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paz, E.G.; Huerta, H.V.; Velasco, F.J.A.; Mengelberg, J.R.B.; Padilla, J.M.R. CPoptim: Convex Partition Optimisation; R package version 0.1.0; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, L.; Luengo, D.; Miguez, J. Independent Random Sampling Methods, 1st ed.; Statistics and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, M.; Alebiary, D.; Aldawsari, M.; Elsawy, A.; AbuEl-Atta, A.H. FERDCNN: An efficient method for facial expression recognition through deep convolutional neural networks. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadit, A.B.; Jatoth, R.K. A novel multi-feature fusion deep neural network using HOG and VGG-Face for facial expression classification. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2022, 33, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthanidam, R.V.; Moh, T.S. A Hybrid Approach for Facial Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication, Langkawi, Malaysia, 5–7 January 2018. IMCOM ’18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Hu, Z.P.; Wang, M.; Bai, F.; Sun, B. Robust Facial Expression Recognition with Low-Rank Sparse Error Dictionary Based Probabilistic Collaborative Representation Classification. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Tools 2018, 27, 1850001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. Video-based emotion recognition using CNN-RNN and C3D hybrid networks. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Tokyo, Japan, 12–16 November 2016; ICMI ’16. pp. 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kas, M.; Merabet, Y.E.; Ruichek, Y.; Messoussi, R. New framework for person-independent facial expression recognition combining textural and shape analysis through new feature extraction approach. Inf. Sci. 2021, 549, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, W.; Goldstein, M. Multivariate Analysis: Methods and Applications; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.