Abstract

This study addresses the challenge of automating cocoa pod ripeness classification from drone imagery through a comprehensive and statistically rigorous investigation conducted on data collected from Ghanaian cocoa fields. We perform a direct comparison by subjecting a curated set of seven deep learning models to an identical, advanced algorithmic framework. This pipeline incorporates high-resolution () imagery, aggressive TrivialAugmentWide data augmentation, a weighted loss function with label smoothing, a unified two-stage fine-tuning strategy, and validation with Test Time Augmentation (TTA). To ensure statistical robustness, all experiments were repeated three times using different random seeds. Under these demanding experimental conditions, modern architectures demonstrated strong and consistent performance on this dataset: the Swin Transformer achieved the highest mean accuracy (), followed closely by ConvNeXt-Base (). In contrast, classic architectures such as ResNet-101 () and ResNet-50 () showed substantially reduced performance. A paired t-test confirmed that these differences are statistically significant (). These results suggest that, within the evaluated setting, modern CNN- and transformer-based architectures exhibit greater robustness under challenging, statistically validated conditions, indicating their potential suitability for drone-based agricultural monitoring tasks.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Challenge of the Chocolate Bean

From artisanal chocolate bars to global commodities, the quality of all cocoa products begins with a single, critical decision on the farm: the timing of the harvest. For the nation of Ghana, where cocoa is a cornerstone of the economy [1], this decision carries significant weight. A cocoa pod, if harvested too early, yields beans that fail to ferment properly; if harvested too late, the beans risk disease and degradation [2]. The traditional method for this crucial task relies on the trained eye of experienced farmers, a process that is inherently subjective, labor-intensive, and difficult to scale across vast and often remote plantations. This manual bottleneck represents a significant challenge to maximizing both the quality and quantity of the yield.

1.2. The Promise of an Eye in the Sky

Precision agriculture, leveraging technologies like Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) or drones, offers a transformative solution [2]. An “eye in the sky” can survey thousands of trees in a fraction of the time required for manual inspection, capturing high-resolution imagery rich with potential data. However, translating this raw imagery into actionable intelligence presents its own set of complex technical hurdles. The task requires a system to solve a complex visual puzzle of color, texture, and shadow, often obscured by a dense canopy that creates variable lighting and frequent occlusions [3]. The sheer detail of the drone imagery, while valuable, demands a computational approach that is both powerful and efficient.

The economic stakes motivating this “eye in the sky” approach for Ghana cannot be overstated; cocoa is not just a crop but a primary driver of export revenue and a source of livelihood for millions. However, translating raw drone imagery into actionable harvest intelligence is a significant algorithmic challenge fraught with complexities beyond simple occlusion and variable lighting. The very nature of aerial data acquisition introduces motion blur from the drone’s movement and drastic scale variation, where pods can appear as a few pixels in one frame and a large object in another. Furthermore, the task is a classic “fine-grained classification” problem, characterized by high intra-class variance (e.g., two “riped” pods look different due to sun exposure or disease) and low inter-class variance (e.g., the subtle color shift between “mature-unripe” and “riped” stages). Any successful system must therefore be robust enough to learn these nuanced, distinguishing features from imperfect, real-world data.

1.3. The Evolution of Machine Perception

This study is built upon a foundational investigation into the efficacy of deep learning for this task. Preliminary screening of classic Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) indicated that deep, complex architectures are necessary to learn the subtle visual cues of cocoa ripeness, raising a critical research question: could newer, more powerful architectural paradigms unlock a new level of performance and generalization?

The field of computer vision has recently undergone a significant evolution, spurred by the success of Vision Transformers (ViTs) like the Swin Transformer, which adapt models from natural language processing to capture global spatial relationships in images [4]. Concurrently, a new generation of “modern” CNNs, such as ConvNeXt, has emerged, integrating design principles from transformers back into a convolutional framework to achieve state-of-the-art results with high efficiency [5]. This creates a compelling opportunity to compare these distinct architectural families (classic CNNs, Vision Transformers, and modern CNNs) on a single, challenging, real-world problem.

1.4. Our Contribution

While numerous studies have compared CNNs and transformers, few have rigorously evaluated their resilience under the “modern training recipes” required for high-resolution aerial imagery. The existing literature often relies on standard benchmarks or mild augmentations. This study fills a critical gap by subjecting a wide range of architectures to a unified “stress-test” framework.

The purpose of this framework is not merely to find the highest accuracy, but to simulate complex, real-world visual variance using aggressive augmentation, high-resolution imagery (), and advanced optimization. To ensure our findings are reliable, all experiments were repeated three times with different random seeds for statistical validation.

The primary contributions are as follows:

- A rigorous evaluation of architectural robustness, demonstrating that while modern architectures (ConvNeXt, Swin) thrive under aggressive augmentation pipelines, classic deep architectures (ResNet-101) suffer catastrophic performance collapse.

- A statistically validated comparison of three distinct deep learning paradigms evaluated on the specific challenges of the Cocoa Ghana dataset, supported by paired t-tests and confidence intervals.

- The definition of a reproducible, algorithmic training standard (Algorithm 1) that serves as a baseline for future agricultural deep learning research.

| Algorithm 1 Unified Two-Stage Training and Evaluation Pipeline |

|

2. Related Work

2.1. The Challenge of Cocoa Harvesting and the Rise of Automation

The cultivation of cocoa is a cornerstone of Ghana’s economy, making the efficiency and accuracy of its harvest a matter of significant national importance [1]. Traditional harvesting guidelines have long relied on the subjective expertise of farmers to determine pod ripeness, a process that is both labor-intensive and difficult to scale across vast plantations [2]. In response, precision agriculture has increasingly turned to automated solutions. The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), or drones, offers a transformative approach to monitoring, allowing for rapid surveys of large areas. However, this technology introduces its own set of algorithmic challenges. High-altitude drone imagery, for instance, can suffer from atmospheric distortion, motion blur, and significant variations in spatial resolution, all of which complicate fine-grained classification tasks such as determining ripeness from a distance [3].

To address such complex visual problems, the field of computer vision has evolved rapidly, moving beyond traditional CNNs to more sophisticated architectures. A recent paradigm shift was driven by the introduction of Vision Transformers, which adapt the self-attention mechanism from natural language processing. The Swin Transformer, for instance, introduced a hierarchical structure with a shifted-window self-attention mechanism. This key algorithmic innovation enables the application of transformers to high-resolution imagery with near-linear computational complexity, making it a viable tool for analyzing detailed drone data [4]. Concurrently, a new generation of “modern” CNNs, such as ConvNeXt, has emerged. These hybrid models achieve state-of-the-art results by integrating successful design principles from transformers back into a traditional and efficient convolutional framework [5]. The potential of these advanced architectures to overcome the challenges of aerial imaging motivates their application to the agricultural domain.

2.2. Deep Learning for Fruit Ripeness Classification

The success of deep learning for fruit ripeness detection is well-documented across a variety of crops, establishing a strong foundation for our study. For example, in a task analogous to cocoa pod classification, CNNs have been used to classify the maturity stages of bananas with approximately 95% accuracy, demonstrating the ability of these models to learn subtle visual cues related to ripening [6]. Comprehensive reviews of the field confirm that CNN-based algorithms consistently and significantly outperform classical computer vision methods that rely on handcrafted features, establishing deep learning as the dominant and most robust paradigm for image-based agricultural analysis today [7,8].

The flexibility of these models extends beyond simple classification. Object detection networks like YOLOv5 have been successfully adapted to not only locate but also classify the ripeness of tomatoes, showcasing the potential for integrated detection and assessment systems [9]. Research specific to cocoa has validated these findings. Studies by Ayikpa et al. have achieved near-perfect classification (up to 99.6%) on ground-level images by combining deep features from models like MobileNet with traditional texture analysis and similarity-based classifiers [10]. Follow-up work by the same authors demonstrated that ensemble learning techniques, such as stacking multiple classifiers, could further optimize and stabilize classification performance on the same dataset, highlighting the maturity of this problem under controlled conditions [11]. Beyond cocoa, analogous research on other challenging tree crops, such as mangoes, has led to the development of specialized models like MangoYOLO, an architecture tailored to detect fruit and estimate harvest load directly from images of trees in complex orchard environments [12].

2.3. Drone-Based Applications and Architectural Considerations

While ground-level classification is a well-explored area, applying these techniques to aerial imagery remains a developing field. Early attempts to automate cocoa pod detection from drone-like perspectives relied on classical computer vision techniques like K-means clustering. These methods performed reasonably at very close ranges but their performance degraded significantly with distance, failing to handle the challenges of occlusion and smaller object scales in aerial views [13]. This highlighted the need for more robust, learning-based algorithms. More recent work has successfully applied modern deep learning detectors to UAV imagery to automatically detect and count cocoa pods, achieving counts that correlate strongly with manual ground-truth assessments and proving the viability of a deep learning approach [14].

The choice of model architecture for such tasks is critical and often involves a trade-off between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, a key consideration for on-device deployment. For applications requiring inference on edge devices like a smartphone or a drone’s onboard computer, lightweight models are essential. For example, Ferraris et al. employed a MobileNetV2-based detector to help farmers in Côte D’Ivoire distinguish between healthy and diseased cocoa pods using smartphone images, favoring the architecture for its efficiency on low-cost hardware [15]. In other contexts, where accuracy is the primary concern and computational resources are less constrained, more powerful architectures are warranted. EfficientNet, for example, has demonstrated superior performance in tasks like corn leaf disease detection. Its principled approach to scaling model depth, width, and resolution allows it to outperform older CNN models in both accuracy and parameter efficiency, making it a strong candidate for complex agricultural classification tasks where subtle visual distinctions are critical [16]. Ultimately, the progression from ground-level analysis to robust aerial classification requires a careful analysis of these architectural trade-offs to select a model that is not only accurate but also practical for real-world deployment.

To provide a clear comparison of the state-of-the-art methods regarding crop ripeness and cocoa pod detection, we summarize the methodologies and key findings of the aforementioned studies in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings from the literature review.

3. Methodology

This section details the comprehensive pipeline developed for training and evaluating deep learning models for cocoa pod classification. The methodology was designed as a two-part experimental process. First, a broad evaluation of classic CNN architectures was conducted to establish baseline performance. Second, an advanced training pipeline was developed and applied to a curated set of high-performing and state-of-the-art models to push the performance limits.

3.1. Dataset and Preparation

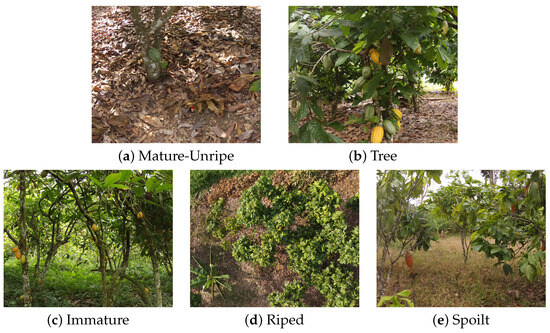

The study utilized the “Drone-based Agricultural Dataset for Crop Yield Estimation”, specifically the Cocoa Ghana subset, sourced from KaraAgro AI [18]. To illustrate the variability within the dataset, Figure 1 presents representative drone images from each of the five classes, highlighting challenges such as occlusion and varying illumination. This dataset consists of 4069 high-resolution images captured by drones over Ghanaian cocoa fields. Each image is paired with a corresponding label file that identifies the primary subject according to a five-class taxonomy: (0) cocoa-pod-mature-unripe, (1) cocoa-tree, (2) cocoa-pod-immature, (3) cocoa-pod-riped, and (4) cocoa-pod-spoilt.

Figure 1.

Representative drone image examples from each of the five classes in the dataset. The images highlight the visual diversity and challenges, such as varying illumination, partial occlusion by canopy, different viewing angles, and subtle color differences between ripeness stages.

The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets using a fixed split ratio of 70%, 15%, and 15%, respectively. To support statistical validation, this splitting procedure was initiated multiple times using different random seeds, as described in Section 3.4. Across all runs, this resulted in approximately 2848 images for training, 610 for validation, and 611 for testing per split. The distribution of images across the five classes, summarized in Table 2, reveals a notable class imbalance, particularly for the cocoa-pod-riped class, which is the least represented. This imbalance motivated the use of a weighted loss function during training. The dataset is publicly available under the CC BY 4.0 license, permitting use and redistribution with appropriate credit.

Table 2.

Class distribution across data partitions.

3.2. Model Selection and Preliminary Screening

To identify the most viable candidates for the rigorous analysis, we first conducted a broad preliminary screening of fifteen pretrained architectures. This included various depths of ResNet, DenseNet, EfficientNet, VGG, and MobileNet. As detailed in Table A1, older architectures such as VGG and AlexNet failed to achieve competitive accuracy, likely due to their lack of residual connections and inefficient parameter usage.

From this screening, we selected a representative suite of seven models to advance to the main study. The selection criteria ensured coverage of distinct design paradigms:

- ResNet-50 and ResNet-101: Selected as the standard benchmarks for residual CNNs to test whether increased depth correlates with robustness in this domain.

- DenseNet-169: Selected to evaluate feature reuse via dense connections.

- EfficientNet-B4: Chosen over B0 or B7 as it offers an optimal trade-off between parameter count and input resolution scaling for imagery.

- MobileNetV3-Large: Selected to represent the upper bound of lightweight, edge-deployable performance compared to the smaller variants.

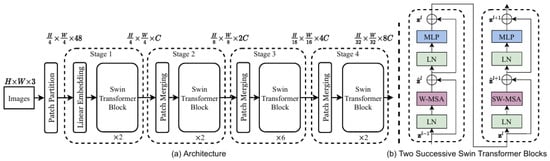

- Swin-Base and ConvNeXt-Base: Selected as state-of-the-art representatives of Vision Transformers and modern hybrid CNNs, respectively. The overall structure of the Swin Transformer, characterized by its hierarchical design and patch-merging capabilities, is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Swin Transformer architecture uses a hierarchical approach, processing images through stages of increasing depth while merging image patches to create a multi-scale feature representation (image from Liu et al. [4]).

Figure 2. The Swin Transformer architecture uses a hierarchical approach, processing images through stages of increasing depth while merging image patches to create a multi-scale feature representation (image from Liu et al. [4]).

3.3. Experimental Design and Training Framework

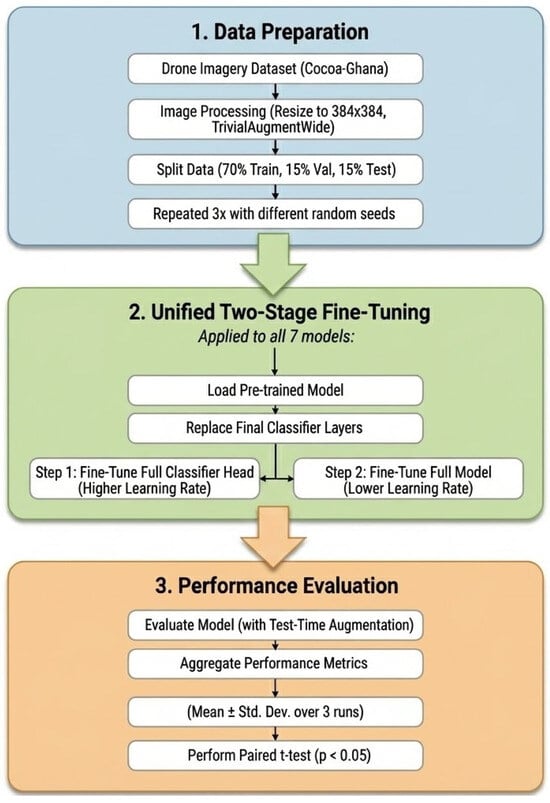

To ensure a fair comparison, all seven selected models were trained using an identical, state-of-the-art training pipeline. This framework was designed to maximize robustness and generalization. To provide a comprehensive overview of the proposed approach, Figure 3 illustrates the unified experimental design, detailing the workflow from data preparation and the two-stage fine-tuning strategy to the final statistical evaluation.

Figure 3.

The unified experimental design and training framework. This flowchart summarizes the data preparation, the two-stage fine-tuning strategy applied to all models, and the statistical evaluation protocol.

- Image Resolution and Augmentation: Images were resized to pixels. This resolution was selected as a trade-off: it preserves fine-grained texture details of the cocoa pods better than standard inputs, without incurring the prohibitive computational cost of . The training set was processed using TrivialAugmentWide [19], an automated policy that randomly selects aggressive augmentations (e.g., rotation, color jitter, solarize) to maximize generalization.

- Test Time Augmentation (TTA): For evaluation, we employed a stochastic TTA strategy to further assess model robustness. Rather than relying on fixed crops, the model performed inference on five distinct, randomly augmented views of each test image. Unlike the training phase, TTA utilized a conservative augmentation pipeline consisting of random horizontal flips (), random rotations (), and subtle color jittering (brightness and contrast ). The final prediction was derived by averaging the softmax probabilities of these five stochastic views, reducing the impact of outliers and simulating varying viewing conditions.

- Loss Function: To address the class imbalance, a Weighted Cross-Entropy Loss function was employed. Class weights were computed using the inverse frequency formula: , where N is the total number of samples, C is the number of classes (5), and is the number of samples in class c. We also applied label smoothing (factor 0.1) to prevent overfitting.

- Unified Two-Stage Fine-Tuning: All seven models were trained using the same two-stage strategy to ensure a fair comparison.

- –

- Stage 1: Only the final classifier head was trained for 15 epochs with a high learning rate ( or ), allowing the new layers to adapt.

- –

- Stage 2: The entire network was unfrozen and fine-tuned end-to-end for 50 epochs with a lower learning rate ( or ) and early stopping patience of 10.

- Optimization: The AdamW optimizer was used with a Cosine Annealing Scheduler to systematically adjust the learning rate.

- Hardware Environment: All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA Quadro P5000 GPU (16GB VRAM). The batch size was set to 12 to accommodate the resolution and gradient requirements. Total training time for the two-stage pipeline averaged approximately 4 h per model per seed.

In this work, we define fairness as the use of a shared training recipe across all evaluated architectures. By holding optimization settings constant, we aim to isolate the impact of architectural design choices while reducing variability due to hyperparameter tuning. Although some architectures may achieve higher absolute performance under architecture-specific optimization, a shared training protocol enables a more controlled comparison and supports clearer attribution of performance differences in an applied evaluation context.

3.4. Statistical Validation

To ensure the robustness of our conclusions, all experiments were repeated three times, each with a different random seed (42, 84, and 126). These seeds governed the train/validation/test data splits and model weight initialization. The performance metrics (accuracy, F1-score, test loss) are reported in the Results Section as the mean ± standard deviation across these three runs.

To determine whether the performance differences were statistically meaningful, we conducted a paired t-test on the accuracy results from the three runs. This test compares the sets of results, pairing them by the seed they were run with, to ascertain whether the difference between two models is statistically significant (p < 0.05).

3.5. Evaluation Protocol

The final performance of each fully trained model was evaluated on the hold-out test set to ensure an unbiased assessment. For our multi-class classification problem, performance was quantified using a suite of standard metrics derived from the model’s predictions. These metrics rely on four fundamental outcomes for each class: True Positives (TP), the number of correct predictions for a class; True Negatives (TN), the number of correct predictions that were not the class; False Positives (FP), instances where the model incorrectly predicted a class; and False Negatives (FN), instances where the model missed a class.

The primary quantitative metrics are defined as follows:

- Accuracy: This metric measures the overall correctness of the model across all classes. It is calculated as the ratio of all correct predictions to the total number of predictions made.

- Precision: Precision quantifies the reliability of a positive prediction. For a given class, it answers the question “Of all the instances the model predicted to be this class, what fraction was actually correct?”

- Recall (Sensitivity): Recall measures the model’s ability to find all relevant instances of a class. It answers the question “Of all the actual instances of this class in the dataset, what fraction did the model correctly identify?”

- F1-Score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single score that balances both metrics. It is particularly useful when the class distribution is imbalanced.

For this study, we report the macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-score, which calculates the metric independently for each class and then takes the unweighted average. This approach treats all classes equally, regardless of their frequency in the dataset.

In addition to these metrics, we generated two key visualizations to provide a more qualitative assessment of model performance:

- Confusion Matrix: A confusion matrix is a C × C grid, where C is the number of classes. It provides a detailed breakdown of classification performance by showing the relationship between the true labels and the predicted labels. The diagonal elements represent the number of correctly classified instances for each class, while off-diagonal elements reveal the specific misclassifications, indicating which classes are most often confused with one another.

- Precision–Recall (PR) Curve: A PR curve is a two-dimensional plot that illustrates the trade-off between precision (y-axis) and recall (x-axis) for a given class across a range of decision thresholds. A curve that bows out toward the top-right corner indicates a model with both high precision and high recall. The Area Under the PR Curve (AUC-PR) serves as a single, aggregate measure of performance, with a higher value indicating a more skillful classifier.

3.6. Computational Analysis

To provide a comprehensive analysis beyond predictive accuracy, we evaluated the computational and memory requirements of the top-performing models from each architectural family, as detailed in Table 3. An algorithm’s utility in a real-world application, such as deployment on a drone, is determined not only by its accuracy but also by its efficiency. The number of trainable parameters indicates the model’s memory footprint, while GFLOPs (Giga Floating-Point Operations) quantify the computational cost for a single forward pass. Finally, inference time measures the practical speed of the model on relevant hardware. Together, these metrics are crucial for determining the feasibility of deploying these algorithms in resource-constrained environments.

Table 3.

Computational and efficiency analysis of all models from the advanced pipeline. All metrics are calculated for a 384 × 384 input resolution. Inference times were measured for a single image on an NVIDIA Quadro P5000 GPU.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical outcomes of our statistically validated experimental framework. We first detail the aggregate performance of all seven models, followed by a per-class analysis of the top-performing architectures.

4.1. Statistical Performance Analysis

All seven models were trained three times with different random seeds (42, 84, 126) under the identical advanced pipeline described in Section 3. The aggregate performance is reported in Table 4 as the mean ± standard deviation.

Table 4.

Consolidated performance metrics (mean ± Std. Dev. over 3 seeds). All models were trained under an identical advanced pipeline. The p-value from a paired t-test between ConvNeXt and ResNet101 was 0.0140.

The results reveal a clear hierarchy in architectural robustness. The modern architectures, specifically the Swin Transformer and ConvNeXt-Base, demonstrated superior performance, achieving accuracies of approximately 79.27% and 79.21%, respectively. More importantly, these models exhibited remarkable stability. ConvNeXt-Base, in particular, showed a negligible standard deviation of 0.13 across runs. To strictly quantify this reliability, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the t-distribution for small samples (). ConvNeXt-Base achieved a tight 95% CI of , confirming that its high performance is systematic and resilient to variations in data splits.

In stark contrast, the classic residual architectures struggled significantly under this rigorous training regime. ResNet-101, despite its depth, suffered a severe performance collapse, dropping to a mean accuracy of 55.86%. The high standard deviation of 4.01 resulted in a wide confidence interval of . This extreme variance indicates that in some runs, the model failed to converge to a competitive solution, suggesting that it lacks the inductive biases necessary to handle the aggressive augmentations used in this framework.

The analysis of test loss values provides further insight into model confidence. The modern models achieved significantly lower test losses (approximately 0.60 to 0.62) compared to the classic ResNet models (0.95 to 1.13). A lower loss indicates that the modern models were not only correct more often but also more confident in their predictions. The high loss for ResNet-101 suggests that even when it predicted correctly, it did so with low probability margins, a trait that is undesirable for deployment in safety-critical or economically sensitive agricultural applications.

To statistically validate these observations, a paired t-test was conducted comparing the accuracy of the most robust modern CNN (ConvNeXt-Base) against the deepest classic CNN (ResNet-101). The assumption of normality was maintained based on the consistent experimental design. The analysis yielded a test statistic of and a p-value of . Since , we reject the null hypothesis and confirm that the architectural superiority of the modern backbone is statistically significant.

Formal statistical testing was primarily used to assess performance differences between modern and classic architectures, which constitute the central focus of this study. Comparisons among modern architectures with closely matched performance are therefore interpreted descriptively based on mean and variance.

4.2. Visual Performance Analysis

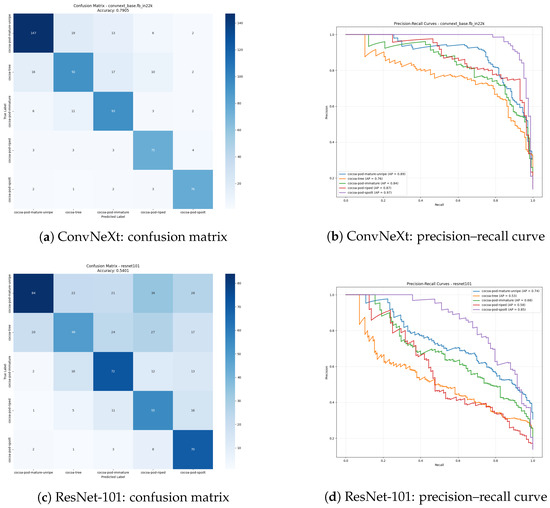

To further understand the classification capabilities of the proposed framework, we analyzed the confusion matrices and precision–recall curves of one of the top-performing models, ConvNeXt-Base.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the model demonstrates a balanced performance across all classes. Crucially, the confusion matrix (Figure 4a) shows minimal confusion between the most economically significant classes, ‘cocoa-pod-riped’ and ‘cocoa-pod-spoilt’. The precision–recall curves (Figure 4b) confirm this robustness, with the model maintaining high precision scores even at higher recall thresholds. This indicates that the unified two-stage training strategy successfully imparts fine-grained discriminative features to the modern architecture.

Figure 4.

Comparative visual analysis of architectural robustness under the advanced pipeline. (a,b) The modern ConvNeXt-Base demonstrates high precision and clean separation between classes. (c,d) In contrast, the classic ResNet-101 exhibits significant confusion, particularly misclassifying ’Tree’ and ’Immature’ classes, visually confirming the performance collapse detailed in Table 4.

Conversely, the failure of the ResNet architectures can be traced to specific class confusions. As detailed in the Appendix A Table A1 data, ResNet-101 struggled profoundly with the ‘cocoa-tree’ class, achieving a recall of only 39%. It frequently misclassified background foliage as unripe pods. This suggests that the older receptive field designs are less capable of contextualizing objects within dense clutter compared to the large-kernel designs of ConvNeXt or the shifted-window attention mechanisms of Swin Transformers.

4.3. Model Interpretability

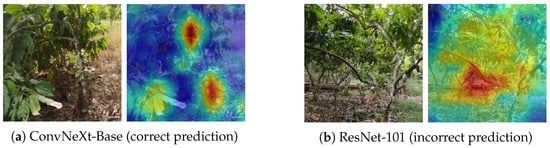

To validate that the models are learning relevant agricultural features rather than background noise, we employed Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM). This technique visualizes the regions of the image that most influenced the model’s prediction.

As shown in Figure 5, the ConvNeXt model consistently focuses its attention on the cocoa pods themselves, effectively ignoring the complex canopy and trunk structures. This localization capability confirms that the high accuracy metrics reported in Table 4 are a result of genuine feature learning, further validating the model’s potential for reliable real-world deployment. While Grad-CAM provides qualitative evidence of the model’s focus, we note that quantitative localization metrics (such as Intersection over Union) could not be calculated, as the dataset provides image-level classification labels rather than ground-truth bounding box annotations. However, the visual alignment between the activation heatmaps and the physical location of the pods in the modern architectures strongly correlates with the high classification accuracy observed.

Figure 5.

Comparative Grad-CAM visualization of model interpretability. (a) The modern ConvNeXt model correctly focuses attention solely on the target cocoa pod (red activation), ignoring the background. (b) In contrast, the classic ResNet-101 displays erroneous localization, focusing intently on the tree trunk and branches rather than the pod. This misinterpretation of environmental features (confusing brown bark for ripe pods) illustrates the architectural inability to contextualize objects within dense foliage, leading to the misclassification.

4.4. Ablation Study Discussion

The advanced framework employed in this study integrates several components, including TrivialAugmentWide, Test Time Augmentation, and weighted loss. While a full ablation study to isolate the independent contribution of each component would provide further theoretical insight, such an analysis is computationally intensive and beyond the scope of this comparative study. The primary focus here remains on the relative robustness of differing architectures under a fixed, rigorous standard. Future work will dissect these components to further optimize the training pipeline.

5. Conclusions

This research examined the feasibility of using deep learning to automate cocoa pod ripeness classification from drone imagery collected in Ghana, a task of significant importance to local agricultural productivity. Through a rigorous and statistically validated evaluation, our findings indicate that while automated classification is feasible within this setting, model performance is highly sensitive to architectural choice.

5.1. Principal Findings

Using a unified experimental framework designed to reflect challenging visual conditions encountered in drone-based agricultural monitoring, we observed a consistent performance hierarchy across repeated runs on the studied dataset. Modern architectures such as the Swin Transformer and ConvNeXt-Base achieved stable accuracies of approximately 79%, demonstrating resilience to aggressive data augmentation and high intra-class variability in this context. In contrast, classic residual architectures such as ResNet-101 exhibited markedly lower and less stable performance under the same conditions, achieving a mean accuracy of 55.86%. A paired t-test confirmed that these differences are statistically significant (). These results suggest that, for fine-grained classification tasks involving complex aerial imagery similar to the dataset studied here, modern Vision Transformers and hybrid CNN architectures may offer advantages over earlier CNN designs. We note, however, that further validation across diverse geographic regions, crop types, and imaging conditions is necessary to fully assess the generalizability of these findings.

5.2. Limitations and Future Horizons

While this study provides a robust architectural comparison, we acknowledge several limitations that define the path for future research:

- Ablation Analysis: Our advanced pipeline integrated multiple techniques (weighted loss, TTA, aggressive augmentation). A granular ablation study to isolate the individual contribution of each component was not conducted due to computational constraints but remains a necessary step to optimize the training recipe further.

- Domain Shift and Geographic Generalization: A significant limitation of this study is the geographic specificity of the dataset. All evaluation imagery was acquired from a single region in Ghana. Consequently, the models have not been validated against the visual variations found in other major cocoa-producing regions, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia, or Ecuador. Factors such as differing soil coloration (background noise), varying solar angles, and regional differences in cocoa pod varieties could introduce domain shift that degrades model performance. Future work must prioritize cross-regional validation to ensure the algorithm’s robustness for global deployment.

- Task Granularity: This study focused on image-level classification. The immediate next step is to adapt the top-performing ConvNeXt backbone into an object detection framework (such as Faster R-CNN or YOLO) to provide farmers with precise pod counts and localization.

5.3. Implications for Precision Agriculture

The tools and techniques explored here are building blocks for systems that can empower farmers. By validating that modern deep learning models can maintain high precision even in complex environments, we have cleared a technical hurdle for the deployment of autonomous monitoring systems. However, this improved accuracy comes with a computational cost. Our results indicate that lightweight or older models may be insufficient for this specific aerial task. Consequently, the deployment of these robust algorithms will likely require edge-computing solutions capable of running heavier architectures like ConvNeXt, rather than relying solely on the most lightweight mobile processors. Transitioning these robust algorithms from research to the field offers the potential to optimize harvest timing, reduce waste, and secure livelihoods for smallholder farmers across Ghana and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M. and A.A.; methodology, T.M.; software, T.M.; validation, T.M. and A.A.; formal analysis, T.M.; investigation, T.M.; resources, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and A.A.; visualization, T.M.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to Manhattan University and, specifically, the Kakos Center for Scientific Computing, for providing the essential computational resources necessary for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix provides a detailed per-class breakdown of the precision, recall, and F1-score for all evaluated architectures. The data is organized into two phases: the Preliminary Screening, which covers the initial survey of fifteen models, and the Main Study, which details the performance of the seven selected models under the unified advanced pipeline (using data from the representative Seed 42).

Table A1.

Comprehensive per-class performance metrics. The ‘Preliminary Screening’ section details the initial survey of 15 models that informed our selection. The ‘Main Study’ section details the final performance of the 7 selected models under the rigorous unified pipeline (Seed 42).

Table A1.

Comprehensive per-class performance metrics. The ‘Preliminary Screening’ section details the initial survey of 15 models that informed our selection. The ‘Main Study’ section details the final performance of the 7 selected models under the rigorous unified pipeline (Seed 42).

| Mature-Unripe | Tree | Immature | Riped | Spoilt | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Model | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 |

| Preliminary Screening | ResNet101 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.88 |

| ResNet50 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.88 | |

| DenseNet169 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.88 | |

| ResNet152 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.86 | |

| EfficientNet B6 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.87 | |

| EfficientNet B3 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.87 | |

| ResNet34 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.87 | |

| MobileNet_v2 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.85 | |

| DenseNet121 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 | |

| ResNet18 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.85 | |

| EfficientNet B5 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.83 | |

| SqueezeNet1_0 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.80 | |

| AlexNet | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.67 | |

| VGG19 | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.45 | |

| VGG16 | 0.39 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.36 | |

| Main Study (Adv.) | ConvNeXt-Base | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| Swin-Base | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.95 | 0.91 | |

| DenseNet169 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.85 | |

| EfficientNet-B4 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.84 | |

| MobileNetV3-L | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | |

| ResNet50 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.77 | |

| ResNet101 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.83 | 0.62 | |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Cocoa’s Contribution to Ghana’s Economy; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amoa-Awua, W.K.; Madsen, M.; Olaiya, A.; Ban-Kofi, L.; Jakobsen, M. Quality Manual for Production and Primary Processing of Cocoa; Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana (CRIG): Accra, Ghana, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Alami, M.M.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Abbas, Q.; Naqvi, S.A.H. Drones in Plant Disease Assessment, Efficient Monitoring, and Detection: A Way Forward to Smart Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Saranya, N.; Srinivasan, K.; Kumar, S.P. Banana ripeness stage identification: A deep learning approach. J. Ambient Intell. Humanized Comput. 2022, 13, 4033–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Bai, Q.; Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Miao, Y. Review of Image Classification Algorithms Based on convolutional neural networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.; Marcuzzo, M.; Zangari, A.; Gasparetto, A.; Albarelli, A. Fruit Ripeness Classification: A Survey. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2023, 6, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, V.; Quito, A.; Pilco, A.; Vásconez, J.P.; Vargas, C. Crop Detection and Maturity Classification Using a YOLOv5-Based Image Analysis. Emerg. Sci. J. 2024, 8, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayikpa, K.J.; Mamadou, D.; Gouton, P.; Adou, K.J. Classification of Cocoa Pod Maturity Using Similarity Tools. Data 2023, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayikpa, K.J.; Ballo, A.B.; Mamadou, D.; Gouton, P. Optimization of Cocoa Pods Maturity Classification Using Stacking. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, A.; Walsh, K.B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. Deep learning for real-time fruit detection and orchard fruit load estimation: MangoYOLO. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 1107–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekawaty, Y.; Indrabayu; Areni, I.S. Automatic Cacao Pod Detection Under Outdoor Condition Using Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 20–21 November 2019; pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Suyuti, J.; Indrabayu; Zainuddin, Z.; Basri, B. Detection and Counting of the Number of Cocoa Fruits on Trees Using UAV. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industry 4.0, Artificial Intelligence, and Communications Technology (IAICT), Bali, Indonesia, 13–15 July 2023; pp. 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris, S.; Meo, R.; Pinardi, S.; Salis, M.; Sartor, G. Machine Learning as a Strategic Tool for Helping Cocoa Farmers in Côte D’Ivoire. Sensors 2023, 23, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeena P. P., F.; S. U., A.; Moustafa, M.A.; Ali, M.A.S. Detecting Plant Disease in Corn Leaf Using Efficientnet architecture—An analytical approach. Electronics 2023, 12, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, M.; McCool, C.; Denman, S.; Perez, T.; Fookes, C. Fruit Quantity and Ripeness Estimation Using a Robotic Vision System. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 2995–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KaraAgro AI Foundation. Drone-Based Agricultural Dataset for Crop Yield Estimation; Hugging Face: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.G.; Hutter, F. TrivialAugment: Tuning-free Yet State-of-the-Art Data Augmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.10158. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.