Abstract

Effective financial fraud detection requires systems that can interpret complex transaction semantics while dynamically adapting to asymmetric operational costs. We propose a hybrid framework in which a large language model (LLM) serves as an encoder, transforming heterogeneous transaction data into a unified embedding space. These embeddings define the state representation for a reinforcement learning (RL) agent, which acts as a fraud classifier optimized with business-aligned rewards that heavily penalize false negatives while controlling false positives. We evaluate the approach on two benchmark datasets—European Credit Card Fraud and PaySim—demonstrating that policy-gradient methods, particularly A2C, achieve high recall without sacrificing precision. Critically, our ablation study reveals that this hybrid architecture yields substantial performance gains on semantically rich transaction logs, whereas the advantage diminishes on mathematically compressed, anonymized features. Our results highlight the potential of coupling LLM-driven representations with RL policies for cost-sensitive and adaptive fraud detection.

1. Introduction

Fraud detection is a critical task for financial institutions, e-commerce platforms, and mobile money providers, where even a small fraction of fraudulent activity can lead to disproportionate financial and reputational losses. The problem is compounded by severe class imbalance—fraud often constitutes less than 0.2% of transactions [1,2], and industry reports similarly indicate fraud rates in the range of 0.1–0.2% for large-scale payment systems [3]—continual concept drift as adversaries adapt, and the multi-modal nature of data that combines structured fields (amount, time, location) with unstructured text (transaction memos, descriptions, customer messages).

Historically, financial institutions relied on rule-based systems, which have largely been superseded by supervised machine learning algorithms such as Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Gradient Boosting Ensembles [4,5]. While these methods represent the current industry standard, they face inherent limitations: they rely heavily on manual feature engineering and struggle to adapt to rapid shifts in fraud tactics without frequent retraining [6]. Furthermore, standard supervised classifiers optimize for global accuracy, often failing to account for the asymmetric costs inherent in financial risk management, where a false negative (missed fraud) incurs significantly higher liability than a false positive (false alarm) [7].

To address these limitations, recent research has diverged into two promising directions. First, Cost-Sensitive Learning (CSL) has emerged as a paradigm to directly embed business costs into the optimization process, prioritizing recall over precision where necessary [8]. Second, Reinforcement Learning (RL) has gained traction for its ability to model fraud detection as a sequential decision-making problem, allowing agents to adapt their strategies dynamically in adversarial environments [9,10]. Simultaneously, the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) has revolutionized the processing of unstructured financial text, enabling the extraction of deep semantic cues from transaction narratives that were previously inaccessible to numerical classifiers [11].

To synthesize these advancements, we design a hybrid pipeline where an LLM encodes both text and structured fields into semantic embeddings, which are then passed to a reinforcement learning agent that acts as an adaptive classifier. The RL agent is trained under a reward function aligned with business utility, assigning a large penalty to false negatives, a moderate penalty to false positives, and positive reward for correct detections. This design allows the policy to adapt over time and prioritize high-recall fraud detection while maintaining operational precision.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews prior research on fraud detection, with an emphasis on machine learning and reinforcement learning approaches. Section 3 introduces the proposed hybrid framework, detailing the large language model (LLM)-based feature encoding mechanism and the formalization of the fraud detection task as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). Section 4 describes the experimental setup, including the datasets, baseline methods, and evaluation metrics. Section 5 presents the empirical results, followed by a comprehensive analysis and discussion of key findings and implications in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines promising avenues for future research.

Contributions

Our main contributions are the following:

- Hybrid RL + LLM framework: We integrate LLM-derived text embeddings with structured features to form the state space for an RL agent that performs cost-sensitive fraud classification.

- Reward shaping aligned with business costs: We design and evaluate asymmetric reward functions that directly encode the higher cost of false negatives relative to false positives.

- Comprehensive evaluation: We benchmark multiple RL algorithms (A2C, PPO, DQN, and contextual bandits) on two fraud detection datasets (European Credit Card Fraud and PaySim), analyzing precision–recall trade-offs under severe imbalance.

- Reproducibility assets: We provide environment design, implementation details, and training configurations to facilitate replication and extension of our results.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the literature pertinent to adaptive, cost-sensitive fraud detection. We first establish the foundational challenge of class imbalance and survey common mitigation techniques (Section 2.1). We then contextualize our work by reviewing the two dominant paradigms: traditional machine learning classifiers (Section 2.2) and more recent reinforcement learning approaches (Section 2.3). Finally, we examine the emerging use of Large Language Models in finance and decision-making, establishing the research gap for a unified LLM + RL framework (Section 2.4).

2.1. Imbalanced Data Classification and Challenges

Fraud detection inherently involves extreme class imbalance, where fraudulent transactions often represent less than 0.2% of all data. This imbalance poses two main challenges: (i) classifiers become biased toward the majority (non-fraudulent) class, leading to high accuracy but poor recall, and (ii) standard loss functions (e.g., cross-entropy) fail to reflect the asymmetric cost of false negatives.

Common remedies include resampling (oversampling minority or undersampling majority classes), synthetic data generation (SMOTE, ADASYN), and cost-sensitive learning that adjusts decision thresholds or penalizes misclassifications based on business costs [12,13]. However, these methods can introduce data leakage or instability in high-dimensional settings.

Reinforcement learning provides a complementary perspective by embedding imbalance handling directly within the reward design. In our setting, the RL agent optimizes a reward function that encodes the asymmetric costs of misclassifying fraudulent and legitimate transactions and can adapt online to non-stationary environments. This shifts the focus from solely reshaping the data distribution to explicitly optimizing the decision-making process under realistic, highly imbalanced conditions.

2.2. Traditional ML/DL for Fraud Detection

The European Credit Card dataset (characterized by extreme class imbalance) has become the canonical benchmark in fraud detection. Deep models such as attention-based LSTMs [14] and ensemble neural networks [15] achieve strong recall and AUC values, while tree ensembles remain competitive. For example, Random Forest and AdaBoost report exceptional accuracy and near-perfect AUC metrics [16,17]. More recent hybrid approaches combining resampling with gradient boosting (e.g., CatBoost) further improve AUC and recall under imbalance [18,19].

Recent advances in deep learning and cost-sensitive methods continue to push state-of-the-art boundaries. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have shown promise in capturing relational fraud patterns, with Wei Zhang et al. [8] achieving substantial improvements in recall on the European Credit Card dataset through cost-sensitive graph architectures. Transformer-based approaches, such as the time-aware fraud detection model by Aminian et al. [20], demonstrate superior recall capabilities by leveraging temporal attention mechanisms, though at significant computational cost. These recent works confirm that maximizing recall while maintaining precision remains a critical challenge for static ML/DL methods.

The PaySim simulator (a large-scale mobile money dataset with severe imbalance) has enabled controlled studies on mobile transfer fraud. Prior work primarily explores XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost frameworks [18], with dataset creators showing baseline ML classifiers aided by dimensionality reduction and resampling [2]. However, most PaySim studies emphasize methodology rather than standardized benchmarks, leaving space for RL- and LLM-based approaches.

Overall, traditional ML/DL methods deliver high predictive performance on imbalanced fraud datasets, but they remain static classifiers vulnerable to concept drift and often require extensive re-weighting or resampling to account for class imbalance.

2.3. Reinforcement Learning for Fraud Detection

Recent work has framed fraud detection as a sequential decision problem. Dang et al. [21] modeled transactions as a Markov Decision Process and trained a Deep Q-Network (DQN) that encoded imbalance costs in long-term rewards. Singh et al. [22] developed a Gym-based environment with DQN agents that achieved close to state-of-the-art performance on highly imbalanced credit card data. Kumari et al. [23] also proposed deep RL approaches, showing growing interest in this paradigm.

More recent RL studies have achieved notable results on benchmark datasets. Qayoom et al. [9] reported highly competitive F1-scores using deep RL on PaySim, demonstrating that pure RL approaches can be effective but often suffer from training instability and high variance in imbalanced settings. Kumari and Acharjya [23] explored actor-critic variants for credit card fraud, achieving promising recall but noting challenges with sample efficiency and convergence. These works highlight that while RL offers theoretical advantages in adaptive, cost-sensitive learning, practical deployment remains hindered by high-dimensional state spaces and sparse reward signals—challenges that motivate our integration with LLM-derived representations.

2.4. LLMs in Financial Text and Emerging RL + LLM

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated strong capabilities in financial text understanding. FinBERT, trained on financial corpora, has been applied successfully to SEC filings and analyst reports [24], while FinChain-BERT [25] improves accuracy by focusing on financial terminology. Bhattacharya and Mickovic [26] fine-tuned BERT on 10-K MD&A sections and achieved superior accounting fraud detection compared to traditional methods.

For transaction-level fraud, LLMs can extract cues from short descriptions or memos. Early studies report that GPT-class models achieve near-perfect identification on PaySim using zero-shot prompting, and anomaly detection studies highlight their ability to flag deviations from normative patterns [27,28]. Smaller domain-tuned models such as DistilBERT and FinBERT often provide competitive accuracy at lower cost, making them practical in production.

Finally, there is emerging work on integrating RL with LLMs in decision-making. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) has been used to align models like ChatGPT-3.5 [29], and systems such as SayCan [30] combine LLMs with RL for robotics. Aminian et al. [20] designed a GPT-based fraud model that captures temporal sequences with RL-like objectives. Yet, despite these parallel advances, the integration of these two fields for transaction-level fraud detection remains largely unexplored. Prior work has not investigated using rich, semantic embeddings from LLMs as a state representation for RL agents, which would allow policies to be trained directly on textual data and aligned with asymmetric business costs. This represents a critical and open research gap.

3. Methodology

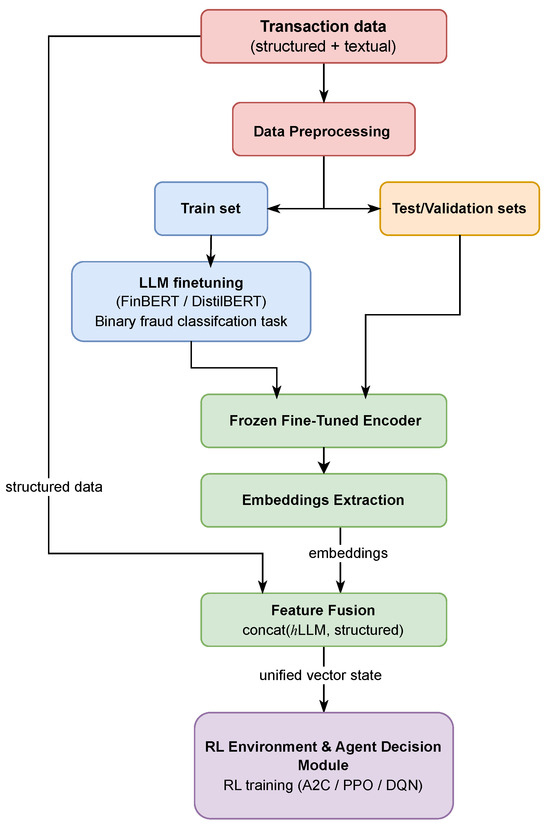

Our framework integrates a large language model (LLM) with a reinforcement learning (RL) agent to build an adaptive, cost-sensitive fraud detection system. The overall architecture of this hybrid pipeline is illustrated in Figure 1. The process begins with raw transaction data, which undergoes preprocessing and is split for training and evaluation. A fine-tuned LLM is used as a frozen encoder to generate semantic embeddings from the data. These embeddings are then fused with the original structured features to create a unified state representation. Finally, this state is fed into an RL agent, which is trained to make optimal classification decisions. The following subsections detail each of these core components.

Figure 1.

High-level architecture of the proposed LLM-RL fraud detection framework. The system processes raw transaction data, uses a fine-tuned LLM to create semantic embeddings, fuses them with structured features, and trains an RL agent on the resulting unified state representation.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

Each transaction contains both structured attributes (numerical features such as amount and timestamp, categorical features such as transaction type, and historical indicators of prior fraud) and unstructured text (descriptions, memos, or free-form notes). Preprocessing standardizes numeric scales (e.g., robust scaling of amounts, temporal features such as time-of-day) and cleans text (removal of personally identifiable information, normalization, and financial-jargon handling). The dataset splits are constructed using stratified sampling to preserve the empirical class ratios across training, validation, and test sets.

To mitigate the gradient starvation caused by extreme class rarity, we apply a controlled undersampling of the majority (legitimate) class restricted strictly to the training split. We retain all fraudulent instances and randomly sample legitimate transactions to achieve a balanced ratio, creating a dense training distribution for both LLM fine-tuning and RL embedding generation. We deliberately exclude synthetic data augmentation; our preliminary experiments with CTGAN failed to show proper convergence, as the synthesized samples demonstrated poor distributional overlapping with real transaction semantics. Consequently, we treat resampling as a pragmatic initialization tool rather than a complete solution, ensuring the agent learns purely from genuine data distributions while the validation and test sets retain their naturally occurring class ratios to rigorously evaluate generalization capability.

3.2. LLM-Based Transaction Encoding

A key novelty of our approach is the transformation of heterogeneous transaction features into natural language form and subsequent encoding with an LLM. To effectively leverage the semantic power of Large Language Models (LLMs) for tabular financial data, we developed a rigorous pipeline that transforms raw transaction records into dense vector representations. This process consists of two stages: template-based serialization and attention-weighted encoding.

3.2.1. Template-Based Serialization

The first step involves converting heterogeneous transaction attributes into a coherent natural language sequence. Let be the set of features for a single transaction. We define a serialization function that maps these features into a structured text prompt using domain-specific templates.

Unlike simple concatenation, we use explicit field indicators to preserve semantic context. For example, a raw transaction tuple is transformed as follows:

This template approach ensures that numerical values (e.g., “250.00”) are not treated as arbitrary tokens but are contextualized as monetary values (“amount of 250.00”), allowing the LLM to attend to the relationship between the transaction magnitude and the merchant description.

3.2.2. Supervised Fine-Tuning

Fine-tuning is a transfer learning technique where a large, pre-trained model is adapted to a new, specialized task. In our work, we take a language model (DistilBERT) and further train it on our specific dataset to become an expert in the binary classification of fraudulent transactions. This adaptation is performed exclusively on training records with their corresponding labels. No validation or test examples are ever used for weight updates or model calibration, ensuring the model’s final evaluation is unbiased.

Formally, this process involves adding a classification head on top of the base LLM and updating the entire network’s parameters () and the new classification head parameters be () to minimize a binary classification loss. For an input transaction text and its true label from the training set (), the optimization objective is to minimize the total binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss:

where the loss for a single instance is

The predicted probability is obtained by passing the LLM’s output representation through the classification head. This entire optimization is strictly confined to the training partition to guarantee that no information from other data splits influences the learned model parameters.

3.2.3. Tokenization and Forward Pass

The serialized sequence is processed by the tokenizer associated with the pre-trained model (DistilBERT). The tokenizer splits the text into sub-word units and prepends the special classification token [CLS] and appends the separator token [SEP]:

where and . In Equation (3), L denotes the maximum sequence length (truncated to 128 tokens for efficiency). The token sequence is passed through the transformer encoder. We extract the hidden states from the final layer of the network, denoted as , where is the hidden dimension size. represents the contextualized embeddings for each token in the sequence.

3.2.4. Attention-Based Pooling Mechanism

To derive a fixed-size vector representation for the entire transaction, we implement a learnable attention pooling layer rather than using the standard [CLS] token or mean pooling. This allows the model to assign variable importance to different parts of the input sequence.

The attention mechanism is implemented as a linear projection. For each token hidden state , we compute a raw attention score using a learnable linear layer defined by weight vector and bias :

To handle variable sequence lengths and ensure padding tokens do not influence the embedding, we apply a masking operation using the binary attention mask :

By setting the scores of padding tokens to a large negative value, we effectively nullify their contribution. We then apply the softmax function to normalize these scores into attention weights :

Finally, the transaction embedding is computed as the weighted sum of the token embeddings:

This resulting vector aggregates the semantic information of the transaction, weighted by the relevance of each token to the fraud detection task.

Why Attention-Based Pooling? Mean pooling treats all tokens equally, which can dilute critical information when fraud indicators are concentrated in a few words (e.g., “urgent transfer overseas”). Attention pooling instead assigns learnable importance weights, enabling the encoder to selectively amplify informative tokens while suppressing irrelevant ones. This mechanism has been shown to improve financial text tasks by focusing on high-salience cues [31,32,33]. This process allows the model to learn which parts of the input text are most relevant for the fraud detection task. Empirically, this approach yields embeddings that are not only more discriminative but also more interpretable, as the attention weights can be inspected to highlight which textual fragments contributed most to the final decision.

3.2.5. Train/Validation/Test Protocol and Data Leakage Controls

To prevent any form of data leakage, all splitting and estimator fitting follow a strict train-only protocol:

- Split before any modeling. We create train/validation/test partitions prior to any preprocessing or model fitting. For the European dataset we use a stratified split; for PaySim we use a chronological (temporal) split to emulate deployment.

- Fit transforms on train only. All preprocessing operators (scalers, PCA/feature reductions, tokenizers’ vocabs) are fit on the training set and then frozen and applied to validation/test.

- LLM fine-tuning on train only. As detailed in Section 3.2.2, the fine-tuning process is restricted to the training set to prevent label leakage.

- Embeddings for val/test via frozen encoder. After fine-tuning, the LLM encoder is frozen. Validation and test embeddings are computed forward-only with the frozen encoder; no adapter updates, prompt revisions, or threshold tuning use validation/test labels except for model selection (via a held-out validation set).

- RL training/evaluation isolation. The RL agent is trained using states derived from the training split only (including the frozen encoder and train-fit transforms). Policies are then evaluated on validation/test with no additional learning.

This protocol ensures that representation learning (LLM), feature scaling, and policy learning never access information from validation/test during training, eliminating label or distributional leakage.

3.3. Feature Fusion

The LLM-derived embedding () is concatenated with normalized structured features to form the RL state representation . This is defined as

Here, represents a preprocessing function (e.g., standardization or min-max scaling) applied to the raw vector of structured features (such as Amount, Time, and account balances). We experiment with both simple concatenation and multi-modal late fusion networks. This unified state enables the agent to leverage semantic signals from text alongside statistical transaction attributes.

3.4. Markov Decision Process Formulation

We formalize the fraud detection task as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by the tuple

where each component captures a specific element of the LLM-assisted reinforcement learning framework.

3.4.1. State Space ()

Each state represents the fused embedding of the current transaction at time step t, combining structured numerical and categorical features with semantic information extracted from the LLM:

where denotes the frozen LLM encoder and the normalized structured feature vector. This state encapsulates the complete contextual snapshot available to the agent before taking an action.

3.4.2. Action Space ()

At each time step, the agent selects an action from the discrete set

These actions mirror operational fraud decisions: allowing a transaction, flagging it for review, or routing it to a verification queue. Each action incurs distinct business consequences reflected in the reward function.

3.4.3. Transition Dynamics (P)

The transition probability models the stochastic generation of the next transaction given the current state and action. Although individual transactions may appear independent, the RL environment treats the data stream as a sequential process where policy behavior influences future distributions (e.g., increased scrutiny may change fraud patterns). This framing enables the agent to learn temporal dependencies and adapt to evolving fraud tactics or concept drift across episodes.

3.4.4. Reward Function (R)

Rewards encode asymmetric business costs for each classification outcome:

This cost-sensitive shaping enforces business alignment by heavily penalizing false negatives and moderately penalizing false positives. The agent is thus encouraged to maximize long-term expected reward rather than immediate accuracy.

Recent studies in modern fraud analytics emphasize this asymmetry, showing that false negatives carry substantially higher financial and operational cost than false positives. Cost-sensitive approaches therefore assign significantly larger penalties to missed frauds to reduce high-impact losses [7,8,34,35].

3.4.5. Discount Factor ()

A positive discount factor accounts for the long-term impact of consecutive decisions:

We set to , ensuring that the agent values both immediate rewards and future outcomes, such as downstream detection accuracy and stability under shifting transaction patterns.

3.4.6. Policy and Objective

The agent learns a stochastic policy parameterized by neural network weights , optimized to maximize the expected discounted return:

Actor–critic and policy-gradient methods (e.g., A2C, PPO) estimate using sampled trajectories and adjust to increase the probability of reward-yielding actions.

3.4.7. Interpretation

Framing LLM-assisted fraud detection as an MDP provides a principled way to reason about sequential decision-making under uncertainty. The LLM encoder defines a semantically rich state space, while reinforcement learning enables optimization over time under asymmetric cost structures. This formulation allows the agent not only to classify individual transactions but also to evolve its policy as fraud strategies drift, balancing precision, recall, and long-term operational utility.

3.5. RL Environment and Decision Module

The RL agent interacts with a fraud detection environment where each transaction is a state , and actions are defined as

Reward Design

To encode business priorities, we assign asymmetric rewards based on the outcome of each classification. In the context of fraud detection:

- TP (True Positive): a fraudulent transaction correctly identified as fraud,

- TN (True Negative): a legitimate transaction correctly identified as non-fraudulent,

- FP (False Positive): a legitimate transaction incorrectly flagged as fraud,

- FN (False Negative): a fraudulent transaction incorrectly passed as legitimate.

The definition of the reward function in Equation (9) reflects that a missed fraud (FN) is an order of magnitude costlier than a false alarm. Such cost-sensitive shaping has been emphasized in imbalanced learning [12,13] and aligns with financial regulation requiring proportionate security measures. The design encourages recall-oriented policies while controlling false positives, shifting the decision threshold toward aggressive fraud catching.

3.6. Algorithmic Choices

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of different reinforcement learning paradigms for this task, we benchmark several distinct families of algorithms. Each was chosen to test a specific hypothesis about what makes for a successful fraud detection agent.

- DQN (Deep Q-Network) [36]: As a foundational value-based method, DQN serves as our primary baseline. It learns to approximate the optimal action-value function, , using a deep neural network, and relies on experience replay and a target network for stabilization. Its performance helps us gauge the effectiveness of learning state-action values in a high-dimensional, imbalanced environment.

- PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) [37] and A2C (Advantage Actor-Critic) [38]: These represent the state-of-the-art in policy-gradient methods. Unlike DQN, they directly learn a stochastic policy () via an actor-critic architecture. A2C provides a strong synchronous baseline, while PPO’s clipped surrogate objective function prevents destructive large policy updates, making it exceptionally robust. We include them to test the hypothesis that directly optimizing the policy is more stable and effective in the sparse-reward and high-dimensional state space characteristic of fraud detection.

- Contextual Bandits (LinUCB) [39]: We include contextual bandits as a simplified, non-sequential baseline. This formulation treats each transaction as an independent, one-shot decision problem, ignoring the long-term consequences of actions (i.e., ). By comparing full RL agents against LinUCB, we can isolate and measure the value added by modeling fraud detection as a sequential Markov Decision Process, thereby justifying the use of a more complex RL framework.

This comparison isolates the benefits of full RL over myopic classifiers, showing how sequential optimization and asymmetric reward design reduce costly false negatives.

3.7. Some Elements Justifying the Foundation of the LLM-RL Integration

The integration of LLM-based encoding primarily addresses the challenge of state aliasing, where fraudulent and legitimate transactions appear indistinguishable in low-dimensional numerical spaces:

y denotes a transaction label (: Probability that the transaction label to be fraud), : label is fraud, : label is legitimate.

By defining a mapping function , we project raw inputs into a high-dimensional semantic manifold where latent linguistic patterns serve to disentangle overlapping class distributions. Formally, this transformation acts as a kernel that maximizes the distance between classes,

thereby increasing state separability. This effectively mitigates the Partial Observability (POMDP) inherent in raw feature sets, allowing the agent to converge on a deterministic policy with significantly lower entropy.

Furthermore, this framework replaces the probabilistic calibration of supervised learning with direct utility maximization. While standard binary cross-entropy () treats prediction errors symmetrically, necessitating post hoc threshold tuning, the reinforcement learning formulation optimizes the expected discounted return directly against the business’s asymmetric cost matrix. By embedding the condition

where represents the heavy penalty for missing a fraud (False Negative) and denotes the moderate cost of a false alarm (False Positive)—explicitly into the reward function , the resulting policy gradient naturally biases the agent toward high recall in regions of uncertainty. This ensures that the optimization trajectory converges to a solution that minimizes actual financial liability rather than merely approximating conditional probabilities.

4. Experiments

This section describes the experimental setup, including datasets, preprocessing, model configurations, and reinforcement learning environment design. Our goal is to evaluate whether integrating LLM embeddings into RL policies improves fraud detection under extreme class imbalance.

4.1. Phase 1—Data Collection and Preparation

4.1.1. Credit Card Fraud Dataset

We use the well-known European Credit Card dataset (284,807 transactions, 0.172% fraud) collected in September 2013. Although the European Credit Card Fraud dataset was collected in 2013, it remains one of the most widely used and accepted benchmarks in recent fraud detection research. Recent studies continue to rely on this dataset for evaluating modern machine learning, deep learning, and cost-sensitive fraud detection models; see for example [40]. Therefore, using this dataset aligns with current research practice and allows meaningful comparison against state-of-the-art baselines. It consists of 28 anonymized PCA-transformed variables (V1–V28), together with Time and Amount. To enable text-based processing, we synthetically generated natural language representations of transactions (e.g., “$247.00 transaction at 12:18:32 with high V3 (−2.15) and low V7 (1.77)”). This provides compatibility with LLM tokenizers. To mitigate imbalance during learning while preserving realistic evaluation, we first perform an 80/20 stratified split on the original, highly imbalanced dataset. Within the training partition, we retain all 492 fraud cases and randomly undersample legitimate transactions to obtain an approximate 5:1 ratio of non-fraud to fraud. The validation and test sets are left at their original class ratios and are never resampled, so all reported metrics on the Credit Card benchmark reflect performance under real-world class imbalance.

4.1.2. PaySim Mobile Transactions Dataset

PaySim simulates 6.3 M mobile money transactions, with an original fraud rate of 0.2%. For the structured input features, we applied one-hot encoding to the categorical transaction ‘type’. We note that this feature has extremely low cardinality, consisting of only five distinct values (PAYMENT, TRANSFER, CASH_OUT, DEBIT, and CASH_IN). Consequently, the encoding adds only minimal dimensionality to the state space and does not introduce the computational bottlenecks or sparsity issues typically associated with high-cardinality features. Numeric balances were scaled using robust standardization.

Following preprocessing, we created a temporally stratified split (70/15/15) to mimic deployment. Within the training split, fraud cases were then randomly oversampled and majority-class transactions moderately undersampled to obtain a balanced training subset of 25,464 transactions used for policy learning. The validation and test sets retain their original, highly imbalanced class ratios and are never resampled, ensuring that all PaySim evaluation metrics reflect performance under realistic deployment conditions. This design exposes the RL agent to sufficient minority examples during training without inflating performance estimates on evaluation data.

4.2. Phase 2—LLM Model Selection and Fine-Tuning

Transaction text (original or synthesized) is processed using DistilBERT or FinBERT depending on the dataset. Structured attributes are textualized and appended to descriptions. A classification head (dense layer + softmax) is trained with class-weighted cross-entropy and focal loss [13]. Optimization uses AdamW with linear decay ( learning rate). Validation follows a 70/15/15 split with early stopping, monitored by area under the precision–recall curve (AUPRC) and F2-score. Models are implemented in HuggingFace Transformers.

Leakage Prevention

All splits are performed prior to modeling. Preprocessors (scalers, PCA) are fit on the training set and reused on validation/test. The LLM is fine-tuned only on training records; validation/test embeddings are computed with the frozen fine-tuned encoder in forward mode. Resampling is restricted to the training split. This prevents representation leakage from validation/test into training.

4.3. Phase 3—RL Environment and Simulator Development

We implemented a custom environment using the OpenAI Gym API [41]. Each step corresponds to classifying one transaction, with the observation space defined as the concatenation of LLM-derived embeddings () and structured features. Actions are discrete: {0 = pass, 1 = flag}.

4.3.1. Reward Implementation

The environment applies the asymmetric reward formulation introduced in Section 3.5, which encodes the higher cost of missed frauds relative to false alarms. This design is directly implemented within the OpenAI Gym-compatible simulator to promote recall-oriented policy behavior while maintaining reasonable precision.

4.3.2. Simulator Features

The environment supports adversarial drift (to mimic concept shift) and synthetic fraud injection for robustness testing. Metrics such as precision, recall, F1, and cost-sensitive expected utility are computed in real time.

4.4. Phase 4—Training the RL Agent

RL algorithms are trained using Stable-Baselines3 [42]. We compare the following:

- DQN [36]: value-based baseline for discrete actions.

- A2C [38]: on-policy actor–critic with low-variance advantage estimation.

- PPO [37]: robust policy-gradient with clipped surrogate objective.

- Contextual Bandits (naïve, LinUCB) [39]: simplified baselines ignoring temporal dependencies.

Hyperparameters follow standard defaults (replay buffer 100 k for DQN, rollout length 2048 for PPO). Models are trained on NVIDIA GPUs; code and seeds are fixed for reproducibility.

4.5. Summary of Experimental Setup

Table 1 summarizes the datasets, preprocessing strategies, and models compared.

Table 1.

Summary of experimental setup.

5. Results and Analysis

We evaluate the proposed RL-based fraud detection framework on two datasets: the European Credit Card dataset and the PaySim simulation dataset. Results include quantitative comparisons, learning dynamics, and classification outcomes, with a focus on cost-sensitive performance.

5.1. Performance on the Credit Card Fraud Dataset

We benchmarked A2C and DQN on the imbalanced Credit Card Fraud dataset. Table 2 summarizes their quantitative performance. DQN achieved the highest overall accuracy and F1-score, balancing recall and precision effectively. A2C attained the highest recall but at the expense of precision, flagging more legitimate transactions. This illustrates the trade-off between false negatives and false positives under cost-sensitive learning.

Table 2.

Performance comparison on the Credit Card Fraud test set (class 1 = fraud).

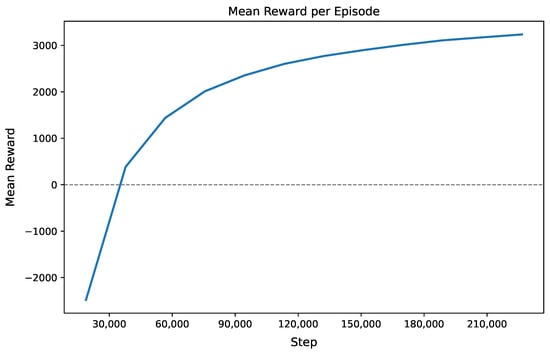

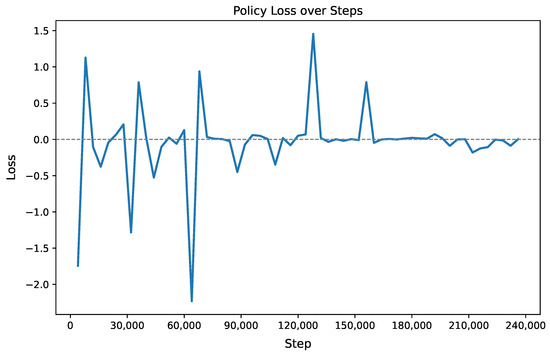

5.1.1. Training Dynamics

Both agents converged stably. For DQN, the rapid rise in mean episode reward followed by stabilization reflects the algorithm’s ability to effectively learn value approximations through experience replay and target network updates. As illustrated by Figure 2, the initial steep climb indicates successful discovery of high-reward state–action pairs, while the subsequent plateau suggests convergence toward a near-optimal policy within the representational capacity of the neural network and the constraints of -greedy exploration. This behavior is typical in DQN when the replay buffer sufficiently decorrelates transitions and the target network stabilizes learning, though further gains may require architectural enhancements, reward shaping, or advanced exploration strategies. Figure 3 shows the oscillatory policy loss given by A2C. The policy loss curve exhibits high initial volatility, reflecting unstable gradient updates during early exploration. As training progresses, after ∼120 k steps the loss stabilizes around zero with diminishing fluctuations, indicating convergence of the policy toward a locally optimal solution. Occasional spikes (e.g., at 60 k and 130 k steps) suggest transient instability due to noisy gradient estimates or sudden shifts in advantage estimation—common in on-policy methods like A2C that rely on recent rollouts. The overall trend confirms effective learning despite non-smooth optimization, typical of actor-critic architectures operating under stochastic policy gradients. In all cases, convergence was reached within 200 k steps, demonstrating efficient policy learning.

Figure 2.

Mean reward per episode for the DQN agent during training on the Credit Card Fraud dataset.

Figure 3.

Policy loss curve for the A2C agent during training on the Credit Card Fraud dataset.

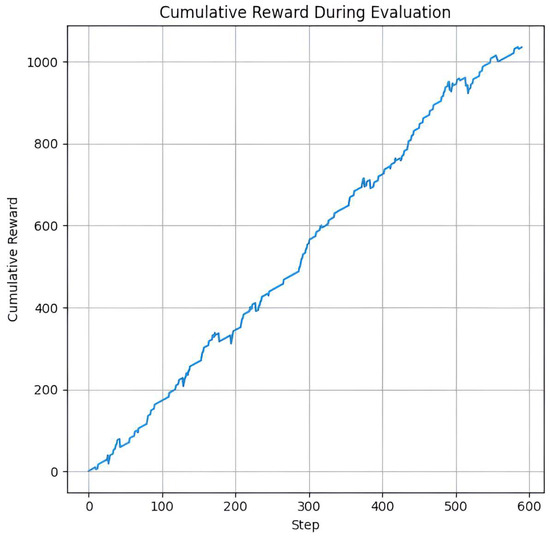

5.1.2. Evaluation Performance

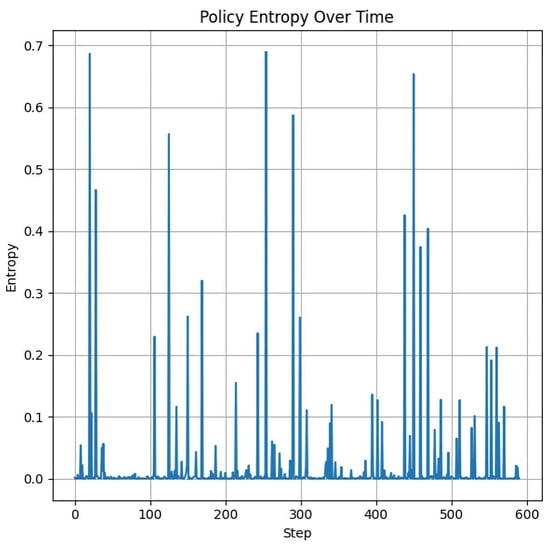

During evaluation, as shown by Figure 4, the DQN agent exhibited predominantly positive step-wise rewards, resulting in a steadily increasing cumulative reward. This monotonic growth reflects consistent policy performance and effective generalization to unseen episodes, indicating that the learned Q-function reliably guides action selection toward high-return trajectories. The absence of significant dips suggests robustness to environmental stochasticity and minimal catastrophic failures during deployment. For the A2C model, as illustrated in Figure 5, policy entropy declined near zero over training steps, indicating progressive reduction in stochasticity and increasing confidence in decision-making. This behavior is consistent with policy convergence in actor-critic methods, where the agent learns to favor high-probability actions as it identifies optimal strategies for detecting fraud. The intermittent spikes reflect transient exploration or shifts in state distribution—common in on-policy RL—but the overall downward trend confirms effective learning.

Figure 4.

DQN reward dynamics during evaluation. Cumulative reward on the Credit Card Fraud dataset.

Figure 5.

A2C agent evaluation: Policy Entropy on the Credit Card Fraud dataset.

5.1.3. Confusion Matrices

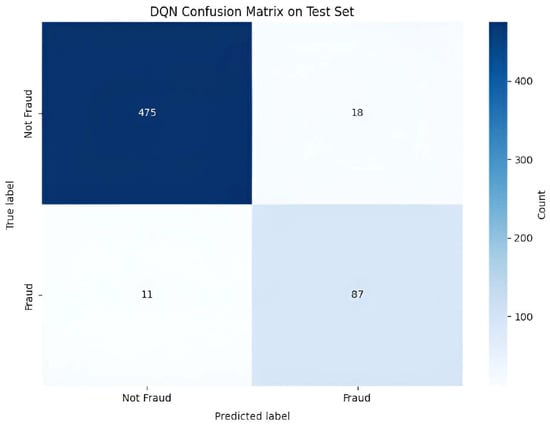

Figure 6 shows the confusion matrix of the DQN model during evaluation, which highlights its strong performance on the binary classification task. With 475 true negatives and 87 true positives, the agent correctly identifies the majority of instances. Low misclassification rates—18 false positives and 11 false negatives—indicate a well-calibrated policy that balances precision and recall. The high diagonal dominance suggests effective learning of decision boundaries, validating the agent’s ability to generalize from learned Q-values to accurate discrete action selection in the evaluation phase.

Figure 6.

Confusion Matrix of the DQN Model on the Credit Card Fraud Test Set.

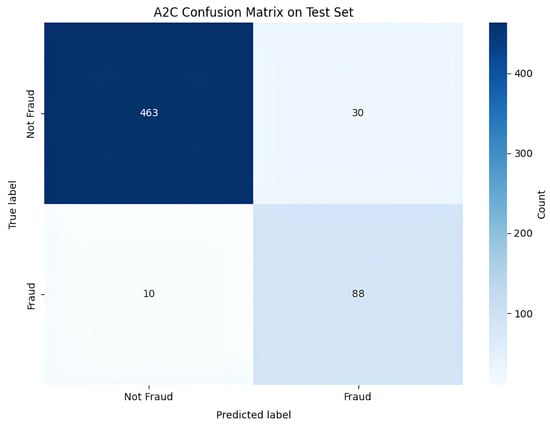

Figure 7 illustrates the confusion matrix of the A2C model, which exhibits strong classification performance, with 463 true negatives and 88 true positives, reflecting high accuracy in class discrimination. The model exhibits low misclassification rates—30 false positives and 10 false negatives—suggesting effective policy learning and well-calibrated action probabilities. While slightly more false positives than DQN, the A2C agent achieves marginally higher true positive detection, reflecting its stochastic policy’s capacity to capture nuanced decision boundaries during evaluation.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrix of the A2C Model on the Credit Card Fraud Test Set.

5.2. Performance on the PaySim Dataset

We extended evaluation to PaySim, comparing A2C, PPO, DQN, and two bandit baselines. Table 3 shows quantitative results. A2C achieved near-perfect precision and recall, outperforming all other models. PPO reached strong but slightly lower precision, while DQN’s high precision came at the cost of very low recall. Bandits failed to capture complex dynamics, validating the importance of sequential decision-making.

Table 3.

Performance on the PaySim fraud detection test set (class 1 = fraud).

Qualitative Insights

A2C achieved near-perfect detection, excelling at capturing rare frauds while preserving precision—reflecting its ability to model sequential risk via on-policy learning and entropy regularization. PPO demonstrated robustness with slightly higher false positives, trading minor precision loss for policy stability—a consequence of its clipped objective that curbs aggressive exploration in ambiguous states. DQN underperformed due to -greedy’s poor sampling of rare events and its off-policy reliance on static replay buffers, which fail to adapt to evolving fraud patterns. Contextual bandits performed worst, confirming that non-sequential methods lack the temporal modeling capacity needed to detect adaptive, multi-step fraud strategies—highlighting the necessity of RL frameworks for dynamic threat environments.

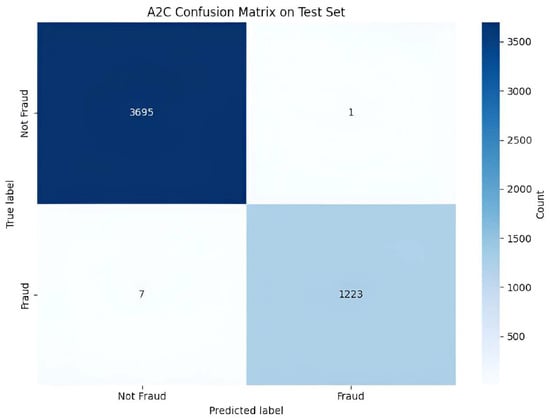

The exceptional performance of the A2C agent is further elucidated by its confusion matrix on the PaySim test set, as illustrated in Figure 8. The matrix reveals a near-perfect classification capability. With 1223 true positives and only 7 false negatives, the agent achieves a recall of 99.4%, demonstrating its profound effectiveness at identifying the vast majority of fraudulent transactions. This directly addresses the core business objective of minimizing costly missed frauds. Concurrently, the model exhibits remarkable precision; the presence of only a single false positive against 3695 true negatives indicates that the agent’s alerts are highly reliable, minimizing the operational overhead associated with investigating false alarms. This balance between extremely high recall and near-perfect precision suggests that the A2C policy, optimized under our asymmetric reward structure, has learned a highly discriminative decision boundary. The agent successfully avoids the common pitfall of sacrificing precision to gain recall, a testament to the stability of on-policy learning when guided by a rich semantic state representation provided by the LLM.

Figure 8.

Confusion Matrix of the A2C Model on the PaySim Test Set.

5.3. Cross-Dataset Comparative Analysis

Taken together, these results highlight three main findings:

- RL outperforms bandits: Sequential learning with cost-sensitive rewards clearly outperforms static classifiers.

- Policy-gradient dominates: A2C and PPO surpass value-based DQN, especially in recall—critical for fraud settings where missed cases are far costlier than false alarms.

- LLM + RL integration adds value: Using LLM embeddings as state inputs enables higher recall and interpretability, giving RL agents richer representations than numeric features alone.

These findings underscore the novelty of our work: while RL has been explored for fraud detection [21,23], and LLMs for financial text [43,44], to our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate their successful integration for cost-sensitive fraud screening.

5.4. Ablation Study

To rigorously assess the individual contributions of the semantic LLM encoder and the reinforcement learning agent, we conducted a component-wise ablation study. We decomposed the framework into three distinct analyses: (1) the standalone performance of the language model, (2) the impact of RL optimization on decision boundaries, and (3) the specific value of semantic features across different data types.

5.4.1. Standalone LLM Performance

To isolate the contribution of the LLM component independently of the RL agent, we first evaluated a standalone DistilBERT classifier fine-tuned on the Credit Card Fraud dataset.

As shown in Table 4, the model achieves a strong recall of 0.8991, successfully identifying the majority of fraudulent transactions. However, this comes at the cost of significantly lower precision (0.6533), resulting in a high number of false positives. This indicates that while the supervised Cross-Entropy loss encourages the model to find fraud, it lacks the nuance to distinguish borderline cases from legitimate transactions effectively.

Table 4.

Standalone DistilBERT Performance on Binary Credit Card Fraud Classification.

5.4.2. Efficacy of RL Optimization

We next assessed whether the Reinforcement Learning agent provides a tangible benefit over supervised learning when costs are asymmetric. We compared the Supervised LLM against RL-only and the RL + LLM model.

As presented in the “Credit Card” section of Table 5, the Supervised LLM improved recall to 89.91% but at the cost of precision, which dropped to 65.33% (52 false positives). In contrast, the RL + LLM model maintained high recall (88.78%) while restoring precision to 82.86%. This demonstrates that the RL agent, driven by the complex reward function (), successfully learned a more nuanced decision boundary that filters out false positives better than a static weighted loss function.

Table 5.

Comparison of LLM-only, RL-Only, and LLM + RL Hybrid Model.

On the PaySim dataset, the necessity of this optimization is underscored by recent benchmarks from Malingu et al. [45], who demonstrated that LLMs applied to PaySim in zero-shot settings achieve poor performance, with AUC scores ranging from 0.475 to 0.492. Their results indicate that without explicit guidance either through extensive few-shot examples or, as in our case, reward-driven policy updates the raw semantic knowledge of the LLM is insufficient to distinguish fraud from legitimate behavior. By adding the RL component, our RL + LLM model bridges this gap, transforming a latent semantic representation into a highly effective policy (F1 0.9985) by directly optimizing for business utility rather than relying on probability calibration or prompt engineering.

5.4.3. Contribution of Semantic Feature Encoding

Finally, we analyzed the necessity of the LLM encoder by comparing the RL + LLM model against an RL-Only agent that consumes raw numerical features. To ensure a fair comparison, the RL + LLM model for the PaySim experiments utilized a specific instance of DistilBERT that was fine-tuned exclusively on the serialized PaySim training logs, analogous to the procedure used for the Credit Card dataset.

Table 5 reveals a stark contrast in the utility of embeddings based on the data type:

Semantic Data (PaySim)

On the PaySim dataset, which contains rich heterogeneous fields (e.g., transaction types like ‘TRANSFER’ vs. ‘PAYMENT’, distinct flags, and temporal patterns), the RL-Only agent struggled to find a stable policy, achieving a maximum F1-score of only 0.6718. Relying solely on raw numbers and one-hot encoded variables resulted in state aliasing, where sophisticated fraud patterns appeared numerically indistinguishable from legitimate high-value behaviors. The inclusion of embeddings from the domain-adapted DistilBERT in the RL + LLM model boosted the F1-score to near-perfection (0.9985). This confirms that for realistic logs, the fine-tuned LLM acts as a critical de-noising filter, projecting raw transactions into a disentangled latent space where the RL agent can easily separate fraud states from legitimate ones.

Abstract Data (Credit Card)

Conversely, on the European Credit Card dataset, the RL-Only agent (F1 = 0.9355) outperformed the RL+LLM model (F1 = 0.8571). This performance inversion is attributable to the nature of the input features: are anonymized PCA components which are already mathematically compressed and orthogonal. We observed that “textualizing” these abstract values (e.g., converting the scalar into the token sequence “V1 is −2.3”) introduces high-dimensional embedding noise without adding new semantic signal. In this context, the LLM encoder acts as a lossy channel, effectively diluting the precise mathematical signal of the PCA vectors. This finding delineates the boundary of our approach: our hybrid framework is highly effective for interpreting meaningful transaction narratives but adds unnecessary complexity when applied to data that has already undergone dimensionality reduction.

6. Discussion

Our results demonstrate the promise of combining large language model (LLM) embeddings with reinforcement learning (RL) agents for financial fraud detection. This hybrid approach creates a system that is both cost-sensitive and adaptive, drawing strength from LLMs’ ability to capture nuanced textual signals and RL’s capability to optimize under asymmetric reward structures. The superior performance of policy-gradient methods, especially A2C, underscores the value of this integration in achieving high recall without compromising precision. In this section, we interpret these findings, situate them within the context of existing fraud detection paradigms, and discuss the practical implications, challenges, and limitations of the proposed framework.

6.1. Comparison with Prior Work and State-of-the-Art

Our findings build upon and extend prior paradigms in fraud detection by addressing key limitations of prior approaches. Traditional machine learning methods, while effective on static benchmarks, are constrained by their inability to adapt to concept drift and their reliance on costly re-weighting or resampling strategies to manage class imbalance [16,17,18,19]. In contrast, reinforcement learning–only approaches offer adaptability through long-term, cost-sensitive optimization but often suffer from sparse positive feedback and instability in high-dimensional feature spaces [9,21,22,23].

To contextualize these conceptual differences with empirical results, we compare the proposed LLM + RL framework against these traditional ML and prior RL-only methods, as summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparative performance of the proposed LLM + RL framework and existing ML and RL-only approaches across multiple datasets. (Acc: Accuracy, Pre: Precision, Re: Recall).

On the European Credit Card dataset, tree ensembles like Random Forest and AdaBoost have achieved accuracies exceeding 96%, but their recall performance varies significantly. AdaBoost achieves a recall of 66.8% [16], while Random Forest reaches 91.1% [17]. More recent hybrid ensembles (e.g., CatBoost) report improved performance under imbalance, achieving a recall of 95.9% and an F1-score of 87.4% [18]. Recent state-of-the-art studies demonstrate further improvements: Graph Convolutional Neural Networks achieve 86% F1 [40], while Hybrid Deep Learning Ensembles [46] and Transformer-based architectures [20] have reached F1-scores as high as 97.5% and 99.8%, respectively. Our A2C + LLM model reaches a recall of 89.8% while maintaining precision at 74.6%, whereas the DQN model offers a balanced trade-off (recall 88.8%, precision 82.9%). The performance gap between our hybrid method and the top-performing numerical baselines corroborates the signal dilution phenomenon identified in our ablation study: textualizing abstract PCA features adds tokenization noise, rendering the framework less effective than specialized numerical models on anonymized data, while highlighting its specific utility for semantically rich environments. On the PaySim dataset, prior work based on XGBoost demonstrates strong accuracy (99.2%) but limited benchmarked recall of 75.0% [47], highlighting the difficulty of reducing false negatives in highly imbalanced settings. More sophisticated approaches, such as the Graph-Enhanced Transformer Network by Bolla et al. [48], have pushed the boundary to 99.5% F1-score. Similarly, recent RL-only work by Agomuo et al. [49] achieves 99.0% F1, while the hybrid FraudGNN-RL framework [50] reaches 92.3% F1 with a strong emphasis on recall (97.3%). Despite these high-performing baselines, our A2C+LLM system achieves near-perfect performance (precision 100.0%, recall 99.7%, F1 99.9%), demonstrating that the semantic enrichment provided by the LLM offers a critical edge even against advanced graph and deep RL methods.

These comparisons highlight that while traditional ML and recent Deep Ensembles deliver high precision on static benchmarks, our LLM + RL framework provides superior recall and substantially reduces costly false negatives—addressing the core business objective of minimizing missed fraud cases.

6.2. Why LLM + RL Outperforms Traditional ML and RL-Only Approaches

While traditional ML methods achieve competitive accuracy on static benchmarks, they face three fundamental limitations that our LLM + RL framework addresses:

6.2.1. Static Decision Boundaries

ML classifiers learn fixed thresholds optimized on training data. When fraud patterns drift (concept drift), performance degrades. Our RL agent continuously adapts its policy through sequential optimization, enabling real-time adjustment to evolving adversarial tactics.

6.2.2. Cost Asymmetry Handling

Traditional methods require manual re-weighting or threshold tuning to encode business costs. Our framework embeds asymmetric costs directly in the reward function (Equation (9)), enabling automatic optimization for business objectives aligned with operational priorities.

6.2.3. Limited Semantic Understanding

Standard ML relies on hand-crafted features or simple embeddings. Our LLM encoder captures nuanced linguistic patterns in transaction descriptions (e.g., “urgent transfer overseas”, “suspicious merchant codes”) that statistical methods miss. As discussed in Section 3.7, LLM-based representations are expected to capture higher mutual information with fraud labels than manual features, because they leverage pre-trained knowledge about financial language and contextual cues.

6.3. The Value and Future of Combining LLMs and RL Agents

This work introduces a novel and highly effective paradigm for fraud detection by synergistically integrating fine-tuned large language model (LLM) embeddings with deep reinforcement learning (RL). Our approach delivers four key innovations that collectively address longstanding limitations in the field:

First, we leverage LLMs not merely as off-the-shelf feature extractors, but as domain-adapted semantic encoders fine-tuned on financial transaction narratives. This yields state representations that capture subtle linguistic and contextual signals—such as anomalous phrasing, inconsistent merchant descriptions, or disguised transaction purposes—that are invisible to conventional feature engineering or shallow classifiers.

Second, we formulate fraud detection as a cost-sensitive sequential decision-making problem within a Markov Decision Process framework. By explicitly encoding business-aware penalties into the reward function—where false negatives incur substantially higher costs than false positives—our RL agent learns policies that are directly aligned with real-world operational objectives, a capability absent in standard supervised models.

Third, our framework is the first to unify semantic understanding with temporal reasoning in fraud detection. Rather than treating transactions in isolation, the agent conditions its decisions on evolving user behavior trajectories, enabling it to detect sophisticated, multi-step fraud schemes that unfold over time.

Fourth, the resulting system is inherently adaptive: unlike static classifiers that degrade as fraud tactics evolve, our RL agent continuously refines its policy through online interaction, offering long-term resilience without requiring full retraining cycles.

These contributions collectively establish a new benchmark for intelligent fraud detection—one that is semantic-aware, economically rational, temporally coherent, and self-updating. While challenges remain in scaling and reward design, our work lays a robust foundation for next-generation systems. Future extensions will explore graph-augmented RL for entity-centric fraud detection, efficient online learning architectures for real-time deployment, and human-in-the-loop mechanisms that integrate expert feedback to accelerate policy refinement. By bridging the representational power of LLMs with the strategic optimization of RL, this paper marks a significant step toward autonomous, adaptive, and business-aligned fraud defense systems.

6.4. Dataset Characteristics and Implications

The datasets highlight complementary strengths and limitations. The European Credit Card dataset provides a real-world benchmark with extreme imbalance but anonymized PCA features that obscure interpretability. This setting tests whether models can succeed without hand-crafted signals. By contrast, PaySim offers large-scale, multi-type synthetic data with injected fraud patterns. While useful for stress-testing, its simulated nature may reduce external validity. Together, these datasets validate robustness across both real-world imbalance and synthetic, high-volume conditions, though future work should include additional domains to ensure broader generalization.

6.4.1. Performance Variations Between Datasets

Our analysis reveals that the effectiveness of the hybrid framework is heavily contingent on the nature of the input features and the scale of the data. We observed a distinct performance dichotomy where the integration of LLM embeddings provided substantial gains on datasets composed of raw, heterogeneous logs but faced diminishing returns on data that had already undergone dimensionality reduction. In the former case, the encoder successfully bridged the semantic gap, extracting latent contextual signals that resolved state aliasing in the raw numerical space, thereby increasing state separability for the agent. Conversely, when applied to mathematically compressed features (such as those from PCA), the process of textualizing abstract values introduced embedding noise and increased state dimensionality without adding information entropy, leading to a phenomenon of signal dilution that hampered policy optimization compared to simpler baselines. Furthermore, the stability of gradient estimation proved sensitive to data volume; larger, richer transactional spaces facilitated faster convergence and more robust policy learning, whereas smaller, highly imbalanced environments limited the agent’s opportunity to capture stable patterns from sparse positive feedback. Collectively, these findings suggest that the proposed architecture is most advantageous when applied to raw, unstructured transaction streams rather than pre-processed, abstract feature spaces.

6.4.2. Implications for Real-World Deployment

A significant consideration for deployment is the nature of available data. Our study used anonymized PCA features and synthetic data. In a production environment, the framework could leverage rich, non-anonymized client information, including customer IDs, merchant names, device information, and transaction locations (e.g., country). In such cases, the LLM’s ability to embed this raw transaction text would be even more critical. It could capture subtle, informative features—such as inconsistencies between a user’s known location and a transaction’s origin—that are absent in anonymized data. This suggests that the performance gains observed here may represent a conservative estimate of the framework’s potential when applied to real-world, feature-rich transaction streams.

7. Conclusions

This paper introduced a hybrid fraud detection framework that integrates large language models as feature encoders with reinforcement learning agents as adaptive, cost-sensitive classifiers. Our experiments on two benchmark datasets demonstrated that policy-gradient methods, particularly A2C, achieve near-perfect precision and recall while decisively outperforming value-based RL and contextual bandits. These results establish that coupling LLM embeddings with RL policies yields measurable gains in recall, precision, and cost-sensitive utility.

However, our component-wise ablation study reveals a critical distinction regarding data modality. While the hybrid pipeline delivers transformative gains on raw, semantically rich transaction logs (such as PaySim) by resolving state aliasing, it yields diminishing returns on mathematically compressed feature spaces (such as PCA-anonymized data) where the textualization process introduces signal dilution. This distinction clarifies the optimal operational domain for our framework, demonstrating that integrating LLM embeddings with policy-gradient RL sets a new benchmark specifically for interpreting heterogeneous, unstructured financial data where traditional numerical methods struggle. Our contributions are threefold: (i) we validate LLM + RL across two distinct fraud domains, delineating the specific conditions under which semantic encoding is beneficial; (ii) we formulate fraud detection as a sequential decision process under asymmetric rewards, capturing the true operational costs of false negatives versus false positives; and (iii) we demonstrate the first integration of LLM embeddings as RL states for fraud detection, closing a gap in the literature.

Future work will focus on extending the system to online learning scenarios, enabling continuous adaptation to adversarial fraud strategies; incorporating graph-based signals such as account–transaction networks to capture relational structure; and designing human-in-the-loop workflows where analysts can provide corrective feedback to guide policy updates. These directions will further enhance adaptability, interpretability, and real-world deployment of LLM + RL fraud detection systems.

In summary, this work provides a foundation for the next generation of fraud detection systems—ones that are not only intelligent and accurate, but also resilient, adaptive, and aligned with real-world financial risk priorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and N.F.; methodology, All authors; software, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; validation, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; formal analysis, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; investigation, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; resources, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; data curation, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; visualization, A.D.H., M.B., I.A. and S.H.; supervision, A.B. and N.F.; project administration, A.B. and N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The source code and models developed in this work are publicly available at https://huggingface.co/djaloul/LLM-RL-Fraud/tree/main/false (accessed on 1 December 2025). The data used in the study are openly available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mlg-ulb/creditcardfraud (accessed on 1 April 2025) and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mtalaltariq/paysim-data (accessed on 1 April 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dal Pozzolo, A.; Johnson, R.; Caelen, O.; Bontempi, G. Credit Card Fraud Detection Dataset, 2015. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mlg-ulb/creditcardfraud (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Lopez-Rojas, E.A.; Elmir, A.; Axelsson, S. PaySim: A financial mobile money simulator for fraud detection. In Proceedings of the European Modeling and Simulation Symposium (EMSS), Larnaca, Cyprus, 26–28 September 2016; pp. 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- ACI Worldwide. Strategies for Fighting Fraud in the Real-Time World; Technical Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.aciworldwide.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/strategies-for-fighting-fraud-in-a-real-time-world.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Popat, R.R.; Chaudhary, J. A Survey on Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 11–12 May 2018; pp. 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, A.O.; Akinyelu, A.A. A survey of machine-learning and nature-inspired based credit card fraud detection techniques. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2017, 8, 937–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojan, Z. Financial Fraud Detection Based on Machine and Deep Learning: A Review. Indones. J. Comput. Sci. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cate, M. Cost-Sensitive Learning in Financial Fraud Detection Models. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393569888_Cost-Sensitive_Learning_in_Financial_Fraud_Detection_Models (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Hu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, X. Cost Sensitive GNN-based Imbalanced Learning for Mobile Social Network Fraud Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayoom, A.; Khuhro, M.A.; Kumar, K.; Waqas, M.; Saeed, U.; Rehman, S.U.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S. A novel approach for credit card fraud transaction detection using deep reinforcement learning scheme. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmi, R.; Suresh Kumar, R.G.; Thanushree, T. A Survey on Credit Card Fraud Detection using Deep Learning Model. Int. Res. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. (IRJAEM) 2025, 3, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Ding, H.; Chen, H. Large Language Models in Finance: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkan, C. The foundations of cost-sensitive learning. In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI’01, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–10 August 2001; Volume 2, pp. 973–978. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchaji, I.; Douzi, S.; Ouahidi, B.E.; Jaafari, J. Enhanced credit card fraud detection based on attention mechanism and LSTM deep model. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenogho, E.; Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Aruleba, K.; Obaido, G. A Neural Network Ensemble with Feature Engineering for Improved Credit Card Fraud Detection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 16400–16407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, K.; Loo, C.K.; Seera, M.; Lim, C.P.; Nandi, A.K. Credit card fraud detection using AdaBoost and majority voting. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 14277–14284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanouz, D.; Subramanian, R.R.; Eswar, D.; Parameswara Reddy, G.V.; Ranjith Kumar, A.; Praneeth, C.H.V.N.M. Credit card fraud detection using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 6–8 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaiz, N.S.; Fati, S.M. Enhanced credit card fraud detection model using machine learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.R.; Gul, H.; Nasir, J.; Al-Issa, Y.I.; Al-Maroof, R.S. Enhancing credit card fraud detection: An ensemble machine learning approach. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminian, G.; Elliott, A.; Li, T.; Wong, T.C.H.; Dehon, V.C.; Szpruch, L.; Maple, C.; Read, C.; Brown, M.; Reinert, G.; et al. FraudTransformer: Time-Aware GPT for Transaction Fraud Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.23712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.K.; Tran, T.C.; Tuan, L.M.; Tiep, M.V. Machine Learning Based on Resampling Approaches and Deep Reinforcement Learning for Credit Card Fraud Detection Systems. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhinin-Vera, L.; Riofrio-Paz, F.; Camacho-G., E.; Brito-P., L.; Chang, O.; Valencia-Ramos, R.; Velastegui, R.; Pilliza, G.E.; Quinga-Socasi, F. Q-Credit Card Fraud Detector for Imbalanced Classification using Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence—Volume 1: ICAART, Valletta, Malta, 22–24 February 2020; SciTePress: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Acharjya, D.P. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Credit Card Fraud Detection. In Proceedings of the Advances in Data-Driven Computing and Intelligent Systems; Das, S., Saha, S., Coello, C.A., Bansal, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Araci, D. FinBERT: Financial Sentiment Analysis with Pre-trained Language Models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, B.; Li, Y. FinChain-BERT: A high-accuracy automatic fraud detection model based on NLP methods for financial scenarios. Information 2023, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Mickovic, A. Accounting fraud detection using contextual language learning. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2024, 53, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Stevens, N.; Han, S.C. Large language models in finance (finllms). Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 24853–24867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkos, E.; Boskou, G.; Chatzipetrou, E.; Tiakas, E.; Spathis, C. Exploring the Boundaries of Financial Statement Fraud Detection with Large Language Models. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4842962 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, M.; Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Chebotar, Y.; Cortes, O.; David, B.; Finn, C.; Fu, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Hausman, K.; et al. Do as I can, not as I say: Grounding language in robotic affordances. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.01691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, D.; Dyer, C.; He, X.; Smola, A.; Hovy, E. Hierarchical attention networks for document classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 1480–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Feng, M.; dos Santos, C.N.; Yu, M.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, B.; Bengio, Y. A structured self-attentive sentence embedding. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.03130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppner, S.; Baesens, B.; Verbeke, W.; Verdonck, T. Instance-dependent cost-sensitive learning for detecting transfer fraud. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 297, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peykani, P.; Peymany Foroushany, M.; Tanasescu, C.; Sargolzaei, M.; Kamyabfar, H. Evaluation of Cost-Sensitive Learning Models in Forecasting Business Failure of Capital Market Firms. Mathematics 2025, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Badia, A.P.; Mirza, M.; Graves, A.; Lillicrap, T.; Harley, T.; Silver, D.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Asynchronous methods for deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 1928–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Chu, W.; Langford, J.; Schapire, R.E. A contextual-bandit approach to personalized news article recommendation. In Proceedings of the WWW ’10: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, Raleigh, NC, USA, 26–30 April 2010; pp. 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Mahdi Yadegar, R.H. FinFD-GCN: Using Graph Convolutional Networks for Fraud Detection in Financial Data. J. AI Data Min. 2024, 12, 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, G.; Cheung, V.; Pettersson, L.; Schneider, J.; Schulman, J.; Tang, J.; Zaremba, W. OpenAI Gym. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, A.; Hill, A.; Gleave, A.; Kanervisto, A.; Ernestus, M.; Dormann, N. Stable-Baselines3: Reliable reinforcement learning implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, P.; Henriques, R. Mining corporate annual reports for intelligent detection of financial statement fraud: A comparative study of machine learning methods. Knowl. Based Syst. 2017, 128, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craja, P.; Kim, A.; Lessmann, S. Deep learning for detecting financial statement fraud. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 139, 113421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malingu, C.J.; Kabwama, C.A.; Businge, P.; Agaba, I.A.; Ankunda, I.A.; Mugalu, B.; Ariho, J.G.; Musinguzi, D. Application of LLMs to Fraud Detection. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 26, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileberi, E.; Sun, Y. A Hybrid Deep Learning Ensemble Model for Credit Card Fraud Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 175829–175838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P.; Abedin, M.Z.; Sivarajah, U. Fraud detection in mobile payment systems using XGBoost-based frameworks. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 1985–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolla, R.L.; Ayyadurai, R.; Parthasarathy, K.; Panga, N.K.R.; Bobba, J.; Pushpakumar, R. Graph-Enhanced Transformer Network for Fraud Detection in Digital Banking: Integrating GNN and Self-Attention for End-to-End Transaction Analysis. Int. J. Res. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2025, 7, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agomuo, O.C.; Uzoma, A.K.; Khan, Z.; Otuomasirichi, A.I.; Muzamal, J.H. Transparent AI for Adaptive Fraud Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 19th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM), Bangkok, Thailand, 3–5 January 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X. FraudGNN-RL: A Graph Neural Network with Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Financial Fraud Detection. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).