1. Introduction

Within a relatively short period of time, Large Language Models (LLMs) have become major business artificial intelligence tools, especially since they can process, reason about, and generate insights related to large and occasionally unstructured datasets. The reason why they are especially powerful, at least in practice, is that they can generate fluent, context-sensitive outputs which can subsequently make otherwise complex analyses and operational problems simpler. These models are broadly applied in organizations in two ways. On the one hand, they favor prediction-related processes, including classification, summarization, or forecasting, which bear a direct impact to decision-making. Conversely, they are also finding apprehension in data management tasks that are concerned with the organization, control, and dependable access to enterprise data. The latter is, arguably, much more difficult since it requires greater reproducibility, the possibility to trace the origins of data, and rigorous audit of the results. These are, as can be imagined, particularly necessary in settings where the strictness of regulatory or compliance-based requirements is applied. Their realization is not a simple matter, and it can be associated with working with disjointed data formats, historical or semi-structured data, changing consent and policy requirements, and, most importantly, how to ensure that the results of model execution are succinct and readily understood and audited by an enterprise system (and hopefully in a manner which humans can feasibly validate).

We propose and apply a framework in this study, that can help solve these problems through a combination of transformer-based LLMs with Apache Spark orchestration, as well as estimating uncertainty with Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. Integrating these parts will help to facilitate scalable, transparent, and auditable data management. The design incorporates a number of important components: controlled data retrieval, deterministic validation, unidirectional lineage tracing, and hierarchical human control. The act of assembling these pieces brings us to the goal of restricting unpredictable behavior, and at the same time, this ensures that every output can be subject to verifiable digital artifacts in controlled business processes.

In order to test this framework, we use it in three representative areas of business, including digital governance, marketing, and accounting. Each area also has its data, functioning procedures, and conformity requirements. Demonstrating by these applications, we indicate that it becomes feasible, practically, to treat complex datasets in a compliant and efficient, and reproducible way, by probabilistic calibration and close monitoring of data origins. The findings indicate that, beyond their origins as predictive text generators, LLMs can function as reliable, accountable, policy-conscious units of enterprise information systems that address regulatory and operational needs.

1.1. Aim of This Study

The primary aim of this study is to design and validate a framework that is clear, auditable, and checkable for using large language models to enhance enterprise data management. We aim, in particular, to move beyond traditional predictive analytics and illustrate how LLMs can function as reliable, interpretable, and policy-aware tools that strengthen data curation, tracking, governance, and controlled access in systems involving multiple stakeholders.

More specifically, our objectives are threefold:

To identify how LLMs deliver measurable benefits in enterprise data workflows;

To examine portability and governance challenges across sectors with differing rules and operational requirements;

To develop distributed, uncertainty-aware systems that integrate Apache Spark orchestration with MCMC sampling, ensuring reproducibility, reliable data tracking, and institutional trust in automated data pipelines.

1.2. Contributions

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

We propose a scalable and adaptable framework for integrating large language models as governed and auditable elements within enterprise data pipelines, which, to our knowledge, has not previously been implemented in this specific combination.

We define and empirically verify seven LLM-enabled functions, spanning data integration, quality assurance, metadata lineage, compliance management, and access control, and demonstrate their applicability across digital governance, marketing, and accounting.

We design a distributed architecture that explicitly accounts for uncertainty, by combining Apache Spark orchestration with MCMC sampling, thereby enabling policy-compliant, reproducible, and transparent data management at scale.

This study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1 How can probabilistic calibration using MCMC sampling be combined with deterministic validation to reduce non-determinism while ensuring explainability and replayability?

RQ2 Which foundational components support the creation of scalable and managed LLM pipelines, including controlled retrieval, provenance anchoring, and risk-based human oversight across industries with differing regulatory requirements?

RQ3 How do these design choices balance semantic accuracy, complete provenance, decision speed, and computational or energy efficiency in real-world environments?

RQ4 Which evaluation methods most effectively connect accuracy, calibration, and governance metrics, in order to enable responsible deployment in business contexts?

The rest of the paper is organized in the following way.

Section 2 reviews background and related work on enterprise data management, probabilistic calibration, and data governance.

Section 3 describes the system architecture and orchestration patterns, including governed retrieval, validator design, and provenance instrumentation.

Section 4 presents the main algorithms and MCMC diagnostics.

Section 5 outlines the architecture patterns and orchestration strategies used in practice.

Section 6 details sectoral implementations and failure modes.

Section 7 describes the evaluation methodology and metrics.

Section 8 reports empirical findings and transferability analysis.

Section 9 discusses implications and limitations, and

Section 10 concludes and outlines future directions.

1.3. Problem Framing & Scope

1.3.1. Defining LLMs for Data Management Versus Prediction

In enterprise information systems, LLM deployments bifurcate into (i)

prediction-oriented uses—classifications, summaries, forecasts—and (ii)

data-management-oriented uses that render data

fit for purpose by curating, governing, and exposing it reliably across platforms in digital governance, marketing, accounting, and big data infrastructures [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Prediction-oriented work optimizes task metrics (accuracy, precision/recall, calibration) and tolerates stochasticity and distribution shift for downstream utility [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Data-management deployments, by contrast, prioritize

process guarantees—reproducibility, provenance, auditability, policy conformance—because outputs (schemas, mappings, lineage, quality assertions, access decisions) become institutional controls [

1,

2,

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

This distinction implies different stakeholders and validations. Prediction primarily serves analysts/marketers/policy teams who accept some opacity for metric lift. Data-management deployments primarily serve data stewards, auditors, and compliance officers, who must rely on evidence objects and replayable pipelines, as illustrated by recent work on provenance systems and audit-ready ML workflows [

21,

22,

40,

45]. In these settings, verification shifts from aggregate predictive accuracy to deterministic validation of lineage coverage, mapping reproducibility, and consent or policy enforcement, supported by provenance-tracking and control-oriented architectures [

38,

39,

40,

45,

46]. Such guarantees are non-negotiable for public registries, financial reporting, and audit workflows, and increasingly shape responsible marketing where consent, transparency, and recourse are essential [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Related probabilistic foundations reinforce these guarantees. MCMC methods and distributed implementations (e.g., over Spark) enable scalable, reproducible posterior sampling in high-dimensional spaces [

51,

52,

53]; Monte Carlo EM for GLMMs operationalizes iterative refinement of latent structures [

54]. These methodologies [

51,

52,

54,

55] illustrate how uncertainty can be quantified while preserving audit-ready reproducibility, informing LLM-driven lifecycle controls across governance, marketing, and accounting.

1.3.2. Functional Boundaries and Scope

Guided by this delineation, we emphasize the capacities of large language models (LLMs) that facilitate adaptive big data governance rather than conventional analytic processing, wherein demonstrable value consistently emerges across multiple domains:

- F1.

Data Ingestion & Integration. Language-grounded semantic alignment across heterogeneous sources; assistive rule generation with rationales; and schema evolution handling in lake and lakehouse settings, where LLMs act as integration co-pilots that propose, validate, and adapt mappings and transformation logic across complex enterprise data landscapes [

16,

17,

23,

56].

- F2.

Data Quality & Constraint Management. Context-aware detection and repair (format, range, referential integrity) using domain semantics, with LLMs surfacing anomalies, proposing candidate fixes, and working in tandem with post-validators to preserve consistency [

10,

11,

37,

57].

- F3.

Metadata & Lineage Management. Automated extraction of technical and business metadata, transformation introspection, and lineage completion to support replayability, impact analysis, and audit-ready provenance across complex pipelines [

19,

20,

33,

34].

- F4.

Governed Data Access via RAG. Consent- and authorization-aware retrieval with citations and policy-conditioned rationales, where LLMs serve as constrained brokers over enterprise knowledge bases rather than unconstrained generators [

2,

13,

17,

36].

- F5.

Document-to-Structure Extraction. High-fidelity parsing of invoices, tenders, contracts, and disclosures into normalized records with confidence scores, cross-links, and master-data validation, often combining LLM reasoning with vision or layout-aware models [

14,

27,

58,

59].

- F6.

Compliance & Privacy Operations. PII/PCI detection and redaction, consent and purpose tagging, policy classification, and continuous violation monitoring with audit-ready justifications to support regulatory compliance across sectors [

45,

46,

48,

49].

Strictly predictive tasks (e.g., demand forecasting, propensity modeling, clustering) are excluded from the scope of this study unless they are directly instrumental to a control objective, such as anomaly surfacing or access-risk scoring [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Our emphasis is therefore on

operational data management, where LLM-enabled pipelines support governance, provenance, and assurance functions in line with enterprise risk and audit practices as shown in works [

12,

29,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

56].

1.3.3. Corpus-Building Approach (Non-PRISMA, Rigor-Preserving)

To balance breadth and depth without formal PRISMA reporting, this study conducts a curated, targeted search with backward/forward snowballing from anchor works. The horizon was 2020–2025 across IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, arXiv, SpringerLink, and sector outlets in information systems, accounting/audit, and public-sector informatics. Inclusion required: (i) an explicit data-management objective (any of F1–F6); (ii) architectural or empirical detail sufficient for reproduction or independent validation; (iii) governance/assurance considerations (provenance, controls, compliance, auditability); and (iv) either cross-context transferability or clear grounding in digital government, marketing, or accounting. We excluded purely predictive demonstrations lacking data-management substance and works without actionable designs.

The resulting corpus integrates peer-reviewed studies, design and architecture papers, and sector exemplars, combining socio-technical breadth (governance, policy, adoption) with technical depth (pipelines, guardrails, evaluation).

First, several works delineate the emerging roles of LLMs in data systems, distinguishing between analytic, governance, and co-pilot functions in enterprise architectures [

1,

2]. Related studies extend these perspectives to corpus-centric and search-augmented settings where LLMs mediate access to large knowledge bases [

13,

17]. Additional contributions explore sector-specific data platforms and proactive data systems that embed LLMs deeper into enterprise decision workflows [

24,

60]. A second group focuses on quality, lineage, and assurance instrumentation, detailing how LLMs assist in constraint checking, error detection, and provenance tracking [

19,

20]. Further work proposes low-overhead provenance frameworks and ML lifecycle transparency platforms tailored to regulated environments [

21,

22]. Classical big data governance and data quality frameworks remain important anchors for these LLM-enabled assurance pipelines [

38,

61]. A third line of work studies integration and ETL co-pilots, where LLMs help design or execute ingestion and transformation flows across heterogeneous sources [

16,

23]. Empirical studies show that language-based co-pilots can propose mappings and transformation logic for complex schemas while preserving human oversight [

24,

26]. Recent platforms integrate these co-pilots with distributed data processing engines to support large-scale ETL orchestration [

12,

56]. Separate studies investigate governed retrieval-augmented generation over enterprise knowledge bases, emphasizing policy-aware retrieval, citation, and justification mechanisms [

2,

17]. Extensions introduce consent-aware and risk-sensitive retrieval pipelines where LLMs act as constrained brokers rather than free generators [

13,

26]. Sectoral deployments further highlight governance challenges around attribution, hallucination control, and answerability in business and public-sector settings [

35,

36].

Another thread develops document-to-structure pipelines that convert semi-structured artefacts such as invoices, disclosures, or logs into normalized datasets with validation hooks [

58,

59]. Vision–language models and layout-aware architectures are used to improve extraction robustness and cross-document linking in enterprise repositories [

27,

31]. These pipelines frequently combine LLM reasoning with classical OCR and schema validation to satisfy audit and reporting requirements [

14,

28]. Finally, a growing body of work examines compliance and privacy operations across sectors, including data provenance, licensing, and risk detection for regulated domains [

47,

49]. Other contributions focus on watermarking, content tracing, and dataset-level governance to support responsible model training and deployment [

48,

50]. Sectoral case studies in public services, environmental domains, and platform governance illustrate how LLM-based controls interact with evolving regulatory frameworks [

42,

62]. We also synthesize emerging and adjacent perspectives, as well as gray or secondary indices, to support triangulation and horizon scanning around LLM use in prediction and sectoral operations [

5,

6]. Additional studies on time-series forecasting and financial or macroeconomic applications highlight how predictive LLM deployments intersect with risk and assurance considerations [

7,

9]. Complementary work on LLMOps and operational governance practices informs our view of production-ready, auditable LLM pipelines [

18,

25].

Collectively, this corpus supports cross-sector abstraction while preserving the

assurance-by-design focus central to digital governance, marketing, and accounting [

33,

56]. Recent architectures for provenance-aware data platforms and controlled LLM integration further reinforce this emphasis on traceability and accountability across enterprise data lifecycles [

34,

37].

1.3.4. Cross-Sector Context Map

Across digital governance, digital marketing, and accounting/audit, LLM deployments converge on transparent, controllable, and auditable data pipelines that emphasize ingestion/integration, data quality, metadata/lineage, governed access (e.g., RAG), and document-to-structure extraction—rather than purely predictive use [

12,

19,

22,

46,

63,

64,

65]. Common structural drivers include: (i) extreme heterogeneity and velocity (registries, case files, sensors; omnichannel telemetry and CRM; ledgers plus semi-structured contracts/disclosures) [

1,

3,

16,

25]; (ii) persistent needs for semantic mapping and entity resolution to support cross-agency harmonization, customer-journey stitching, and subsidiary consolidation [

3,

16,

25]; (iii) pervasive quality, compliance, and explainability pressures—GDPR-style consent/purpose limits and SOX/ISA/IFRS documentation—favoring auditable, reproducible tooling [

2,

12,

22,

46,

47]; (iv) provenance/lineage as first-class controls for trust and assurance, with LLMs extracting and completing evidence graphs [

19]; and (v) governed, purpose-limited access to natural-language interfaces via policy- and consent-aware retrieval [

2,

12]. Sectoral stakes then differentiate priorities:

Digital governance. Citizen-centric records, identity/authentication logs, and multi-agency documents mix long-lived masters with episodic cases and IoT streams [

1]. Statutory transparency and strict consent boundaries heighten requirements for provenance, auditability, and explainable access; errors affect rights and service equity [

12,

46,

47]. LLMs should focus on policy-aligned ingestion/integration, documentation, and lineage extraction, and governed RAG that emits citations and oversight-ready rationales [

2,

19].

Digital marketing. High-velocity behavioral telemetry, adtech interactions, CRM histories, and social text—often blended with third-party data—operate under evolving contracts and privacy regimes [

16,

25]. Differential consent and purpose limitation intersect with rapid experimentation; misuse or scope creep creates regulatory and reputational risk, while weak identity resolution erodes ROI [

2,

12,

47]. LLM priorities: consent-aware ER/identity mapping, contract/policy extraction, and governed RAG over CDPs and knowledge assets with policy filters by design [

2,

3,

12,

16].

Accounting/audit. Structured financial systems and semi-structured artifacts (invoices, receipts, contracts) must form durable, replayable evidence chains [

3]. External assurance demands determinism, reproducibility, and consistent evidence; human-in-the-loop controls and verifiable logs must bound stochastic behavior [

19,

22]. LLMs fit best in deterministic document-to-structure extraction with validators, metadata/lineage completion, and access workflows preserving segregation of duties and audit trails [

19,

22]. All the above elements are analysed further in

Table 1.

Synthesis. LLMs function best as

assistive, governed components that (i) accelerate semantic alignment and documentation, (ii) fortify quality and lineage controls, and (iii) mediate policy- and consent-aware access. Public services prioritize transparency and recourse [

12,

46,

47]; marketing emphasizes agility under consent and purpose limits [

2,

12]; and accounting requires determinism and replayable evidence [

19,

22]. Accordingly, evaluation must weight provenance coverage and control effectiveness alongside task accuracy to ensure inspectable, reproducible, and compliant pipelines across contexts [

1,

3,

16,

19,

22].

2. Taxonomy of LLM-Enabled Data Management Functions

This section defines seven reusable functions through which LLMs deliver

intelligent big data management across digital governance, marketing, and accounting [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. The taxonomy proceeds from upstream alignment to downstream governed access, matching subsections F1–F7 and the pipeline summarizations in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. For each function, we state the objective, outline typical realizations, and summarize reported evidence, with concise transitions to the next stage.

2.1. F1. Schema & Mapping Co-Pilot

Function. Assist schema understanding, cross-system mapping, and semantic reconciliation, producing governed transformations with human-reviewable rationales [

71,

72,

73,

74]. LLMs exploit natural-language metadata and glossaries to propose semantically faithful mappings beyond syntactic matchers.

Realizations & evidence. Pretrained LLMs are coupled with knowledge bases, mapping histories, and catalog metadata; RAG retrieves prior decisions and style guides; program analysis exports versioned artifacts. Enterprise-scale routing/selection is demonstrated for federated repositories. Studies report high precision and reduced effort, with accelerated schema-evolution timelines via automated impact analysis [

71,

72,

73,

75,

76,

77,

78].

Transition. Record-level consistency motivates F2.

2.2. F2. Entity Resolution Assistant

Function. Consolidate duplicates/relations by combining embedding-based blocking with LLM adjudication to handle ambiguity and contextual references [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

Realizations & evidence. Candidates are staged via vector similarity; prompts encode schema, rules, and exemplars; batching and demo selection optimize cost/quality. Clustering with in-context demonstrations lowers pairwise complexity and enables uncertainty-driven verification. Reported results show F1 gains and multi-fold API-call reductions with competitive quality, including strong performance in geospatial/public-record settings [

79,

81,

83].

Transition. With entities reconciled, fitness-for-use is addressed in F3.

2.3. F3. Data Quality & Constraint Repair

Function. Complement profilers and rule engines by contextualizing anomalies, distinguishing errors from edge cases, and proposing policy-consistent repairs that preserve integrity [

84,

85].

Realizations & evidence. Hybrid designs pair statistical detection with LLM-based explanation/remediation, followed by deterministic validators and rollback safeguards; iterative refinement emits machine-auditable justifications. Evidence indicates strong detection, practical auto-remediation when domain knowledge is injected, and improved blocking under semantic noise.

Transition. Quality actions must be explainable and traceable, motivating F4.

2.4. F4. Metadata/Lineage Auto-Tagger

Function. Extract technical/business metadata and complete lineage across code, notebooks, and workflow logs to support governance, impact analysis, and assurance.

Realizations & evidence. Program/workflow analysis feeds LLM summarization and semantic annotation; some systems anchor lineage in immutable ledgers [

12,

18,

21,

22]. Implementations report efficient tracking and end-to-end ML provenance with substantial documentation reduction and audit-ready enterprise trails.

Transition. Operationalized policy follows from lineage; F5 focuses on privacy/consent and PII handling.

2.5. F5. Policy/Consent Classifier & PII Redactor

Function. Automate policy classification (e.g., GDPR/CCPA purpose), consent-state reasoning, and sensitive-data handling across structured/unstructured assets [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91].

Realizations & evidence. Multi-model pipelines pair specialist PII detectors with LLM legal/policy reasoning and consent propagation, integrating knowledge graphs and registries; borderline cases are triaged by humans; monitors emit machine-checkable rationales. Reported systems achieve high compliance precision/recall and reduce manual review via KG augmentation and consent-platform integration.

Transition. With processing controls established, F6 structures unstructured inputs.

2.6. F6. Document-to-Structure Extractor

Function. Convert invoices, contracts, receipts, and filings into normalized records with field-level confidence, cross-document links, and master-data validation [

92,

93,

94,

95].

Realizations & evidence. Vision–language pipelines combine layout analysis with LLM field semantics, domain validators, and memory/agentic learning from corrections. Benchmarks and cases show double-digit accuracy gains over single prompts/vanilla agents, with quantified robustness to rotation/layout and notable efficiency benefits.

Transition. Finally, curated corpora require safe, explainable access (F7).

2.7. F7. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) for Governed Data Access

Function. Provide compliant, explainable, least-privilege natural-language access with authorization, consent, and minimization, emitting citations and logs [

2,

13,

17].

Realizations & evidence. Vector indexing is combined with policy filters, consent checks, and PII redaction

pre-synthesis; schema-routing co-pilots scale to large repositories; full trails support audit/incident response [

13,

17,

73]. Studies show effective policy adherence without material loss of answer quality; search-augmented training stabilizes attribution/compliance.

Synthesis. F1–F7 form an auditable pipeline: semantics-aware integration (F1) and entity fidelity (F2) provide coherence; fitness-for-use is assured (F3) and documented (F4); processing is constrained by policy/consent (F5); unstructured inputs are normalized (F6); and access is governed (F7).

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 consolidate performance, sectoral fit, complexity, and risk mitigation.

Table 2.

Reported performance characteristics of LLM-enabled data-management functions.

Table 2.

Reported performance characteristics of LLM-enabled data-management functions.

| Function | Accuracy Range | Speed Improvement | Manual Effort Reduction | Primary Success Metrics (Refs.) |

|---|

| Schema & Mapping Co-Pilot | 85–92% | 60–75% | 60–75% | Mapping precision; semantic correctness [71,72,73,75,76] |

| Entity Resolution Assistant | 82–99% | Up to 5× fewer LLM calls | — | F1; clustering quality; cost/quality trade-offs [79,80,81,82,83] |

| Data Quality & Constraint Repair | 65–80% detection; 50–70% auto-remediation | — | — | Detection rate; repair success; FP rate [84,85] |

| Metadata/Lineage Auto-Tagger | 75–90% coverage (reported) | Real-time or near-real-time | 75–90% documentation reduction | Lineage completeness; provenance readability [12,20,21,22] |

| Policy/Consent Classifier & PII Redactor | 83–95% | 60–80% review reduction | — | Compliance precision/recall; PII detection rate [86,87,88,90,91] |

| Document-to-Structure Extractor | 75–95% | 30–35% | — | Field-level F1; robustness to layout/rotation [92,93,95] |

| RAG for Governed Data Access | Query-dependent | Scales to large DBs | — | Response accuracy; compliance adherence [2,13,73] |

Table 3.

Sector applicability of the seven functions with indicative differentiators.

Table 3.

Sector applicability of the seven functions with indicative differentiators.

| Function | Gov. | Mkt. | Acct./Audit | Key Differentiators (Refs.) |

|---|

| Schema & Mapping Co-Pilot | High | High | High | Cross-agency, omnichannel, and subsidiary

harmonization [72,73,75,76] |

| Entity Resolution Assistant | High | High | High | Citizen/customer/vendor identity fidelity [79,80,81,83] |

| Data Quality & Constraint Repair | Medium | High | High | Real-time cleaning vs. regulatory determinism [84,85] |

| Metadata/Lineage Auto-Tagger | High | Medium | High | Transparency and audit-trail depth [12,20,21,22] |

| Policy/Consent Classifier & PII Redactor | High | High | Medium | Consent and purpose limitation; policy verification [86,88,90,91] |

| Document-to-Structure Extractor | Medium | Medium | High | Volume and criticality of invoices/contracts [92,95] |

| RAG for Governed Data Access | High | High | Medium | Natural-language access under policy/consent [2,13,17,73] |

Table 4.

Implementation complexity and resource considerations.

Table 4.

Implementation complexity and resource considerations.

| Function | Technical Complexity | Infrastructure Requirements | Governance Overhead | Typical Time |

|---|

| Schema & Mapping Co-Pilot | Medium | Knowledge bases; catalog integration | Low | 2–3 months |

| Entity Resolution Assistant | Medium–High | Vector/cluster infrastructure | Medium | 3–4 months |

| Data Quality & Constraint Repair | Medium | Rule engines; validators | Medium | 2–4 months |

| Metadata/Lineage Auto-Tagger | High | Lineage/graph stores; code parsing | High | 4–6 months |

| Policy/Consent Classifier & PII Redactor | High | Privacy KG; consent registry; DLP | High | 4–6 months |

| Document-to-Structure Extractor | Medium–High | Multi-modal models; RPA/ETL hooks | Medium | 3–5 months |

| RAG for Governed Data Access | High | Vector DB; policy engine; secure gateways | High | 4–8 months |

Table 5.

Primary risks, failure modes, and proven mitigations.

Table 5.

Primary risks, failure modes, and proven mitigations.

| Function | Primary Risk Factors | Failure Modes | Mitigations and Monitoring (Refs.) |

|---|

| Schema & Mapping Co-Pilot | Schema hallucination; overgeneralization | Incorrect mappings; integrity breaks | Confidence thresholds; mandatory human validation; mapping telemetry [71,72,73,75,76] |

| Entity Resolution Assistant | Over/under-clustering; drift | Duplicate merges; missed links | Uncertainty-driven prompts; balanced demos; precision/recall dashboards [79,80,81,82] |

| Data Quality & Constraint Repair | Over-correction; rule conflicts | Data corruption; regressions | Deterministic validators; rollback; change logs [84,85] |

| Metadata/Lineage Auto-Tagger | Incomplete capture; overhead | Missing dependencies; stale lineage | Hybrid capture; coverage SLOs; spot audits [20,21,22] |

| Policy/Consent Classifier & PII Redactor | False negatives; policy drift | PII leakage; unlawful purpose | Multi-stage detection; human-in-the-loop; violation alerts [86,88,90,91] |

| Document-to-Structure Extractor | Layout/rotation variance | Field misreads; linkage errors | Multi-modal fusion; validators; layout/rotation pre-processing [92,95] |

| RAG for Governed Data Access | Hallucination; privilege creep | Unauthorized disclosure | Sandboxed retrieval; policy filters; full query audit [2,13,17] |

3. Methodology

In this section, a systematic and principled methodology is proposed to address the challenges of large-scale, data-driven intelligence across digital governance, marketing, and accounting applications. Special emphasis is placed on the integration of sectoral datasets, advanced distributed processing, probabilistic sampling via Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, and robust evaluation within a reproducible and auditable framework.

3.1. Datasets and Data Generation

This study is based on a combination of real-world and synthetically generated datasets. For each evaluated sector , we denote the corresponding dataset as .

To benchmark scalability, robustness, and methodological performance, synthetic datasets

are generated under parametric templates parameterized by

, allowing exact control over entity distributions, attribute sparsity, and cross-table dependencies:

Table 6 summarizes the main characteristics and the functions (F1–F7) instantiated per dataset.

3.2. Distributed LLM and MCMC Framework

In this section, we present a distributed LLM architecture, harnessing the Apache Spark platform for scalable data partitioning and compute orchestration, and employing MCMC sampling for quantifiable uncertainty and adaptive provenance.

3.2.1. Data Preprocessing and Partitioning

Each dataset

is first loaded into the distributed environment and divided into logical partitions using a hash-based function that ensures balance and preserves both sector and entity semantics. Formally, we define the partitioning function

and the corresponding partition operator as:

This strategy allows the system to process data in parallel across all partitions while maintaining sector-specific grouping, which is crucial for consistent governance analysis and domain-aligned model execution.

3.2.2. Model Invocation and Inference

We deploy large language models customized to each sectoral task—such as retrieval-augmented generation, consent-aware entity resolution, and multimodal document extraction—through Spark’s distributed UDF pipeline. Each model operates as an independent microservice, allowing elastic scaling and fault-tolerant inference. Let

represent a sector-specific LLM characterized by parameters

:

Parallel inference over partitioned inputs ensures high throughput and extensive coverage across diverse workloads. This setup effectively couples model invocation with cluster-level scheduling, maximizing performance while maintaining deterministic task flow.

3.2.3. MCMC Posterior Sampling for Uncertainty Quantification

To evaluate model reliability under variable data quality and regulatory conditions, we adopt a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach for posterior estimation. Given an input

and sector-specific model

f we estimate the posterior distribution over outputs

as:

Each iteration of sampling progresses according to:

where

represents a proposal kernel that incorporates both task parameters and regulatory constraints, and

denotes sector-aware hyperparameters. The aggregated expectation over all samples yields the uncertainty-adjusted estimate:

This process provides both interval-based confidence and a calibrated representation of decision uncertainty suitable for regulated enterprise use.

3.2.4. Provenance and Traceability

To ensure full reproducibility and end-to-end auditability, each inference and corresponding MCMC sample is tagged with a deterministic provenance identifier derived from the data stream and system state:

This provenance identifier allows downstream traceability across Spark partitions, model checkpoints, and validation events. It also enables seamless alignment with post-hoc audits, lineage tracking, and cross-sectoral compliance assessments.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics and Uncertainty Reporting

We evaluate the system using a series of domain-relevant performance and reliability metrics, collectively represented as

. For each metric, results are reported with their corresponding 95% credible intervals derived from the MCMC posterior distribution. A 95% credible interval is adopted as it aligns with prevailing audit and risk-management practice, while remaining tight enough to inform operational thresholds in compliance-critical settings; alternative coverage levels can be configured where regulation demands. The posterior is given as:

The credible interval is computed as:

where

.

This formulation provides both point estimates and empirical uncertainty bounds, allowing the reported figures to be interpreted with statistical confidence while maintaining alignment with audit and reproducibility standards.

This principled approach enables not only superior predictive and extraction accuracy but also rigorous quantification of uncertainty and reproducibility, advancing the state-of-the-art for sectoral AI in real-world enterprise.

3.3.1. Baselines

To contextualize the performance of the proposed LLM-enabled functions, three classical baselines are considered. For F1 (schema mapping), a non-LLM matcher is used that combines token-based string similarity (e.g., Jaccard and edit distance on attribute names) with rule-based type checks to select mappings. For F2 (entity resolution), a blocking-plus-rules baseline is instantiated with deterministic blocking keys (normalized names and identifiers) and fixed similarity thresholds without LLM adjudication. For F7 (governed retrieval), a keyword/BM25-style retrieval model over the same indices is employed, without LLM reasoning or policy-aware re-ranking. Baseline scores are reported alongside the proposed metrics (e.g., SWMC, CERS, QPEG) in the evaluation tables, illustrating relative gains in mapping correctness, resolution quality, and governed answer accuracy.

3.3.2. Implementation Details

Text-based functions (F1–F5, F7) were implemented leveraging a GPT-4-class large language model accessed via an HTTP API, while document-to-structure extraction (F6) utilized a vision–language model combining OCR and layout-aware text understanding. Model invocations were orchestrated from Apache Spark using distributed user-defined functions (UDFs) that called per-partition microservices; each worker maintained a small pool of HTTP clients to amortize connection overhead and ensure fault-tolerant retries. Models were operated in a zero-shot or few-shot prompting regime, using sector-specific templates and small sets of in-context examples extracted from dataset training splits, without extensive fine-tuning. For MCMC sampling, a random-walk proposal kernel over discrete mapping or label spaces was employed, running 1000 iterations per batch, including a brief warm-up phase, with acceptance rates tuned between 0.3 and 0.5. Experiments were executed on a cluster composed of 8 worker nodes, each featuring 8 CPU cores and 16 GBs of RAM. Typical end-to-end runtimes for the largest synthetic datasets were on the order of tens of minutes.

3.3.3. MCMC Versus Simple Repetition

Beyond reporting posterior credible intervals via MCMC, we conducted a simple ablation to compare MCMC-based uncertainty with variance estimates obtained from repeated runs without MCMC. We evaluate metrics:

using Markov chain samples

estimating the posterior expectation

and variance

The 95% credible interval is

For comparisons, we perform an ablation estimating uncertainty from repeated runs without MCMC by running the pipeline

times, computing empirical variance

where

This contrasts with MCMC variance

Repetition variance captures instability from stochastic pipeline elements only, whereas MCMC variance reflects also model and decision uncertainty given the probabilistic model. This makes MCMC intervals preferable for compliance, providing calibrated, interpretable uncertainty bounds aligned with regulatory coverage requirements.

4. Proposed Algorithms

4.1. ReMatch++: Schema & Mapping Co-Pilot

In this section, we propose the “ReMatch++” algorithm, a schema mapping co-pilot designed to maximize Semantic-Weighted Mapping Correctness (SWMC), while enabling transparent, human-in-the-loop data integration. The key innovation is the use of distributed LLM-based mapping proposals, scored and validated by both AI and deterministic policy checks, with all candidate rationales sampled for uncertainty using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). The representation of the Algorithm is given in

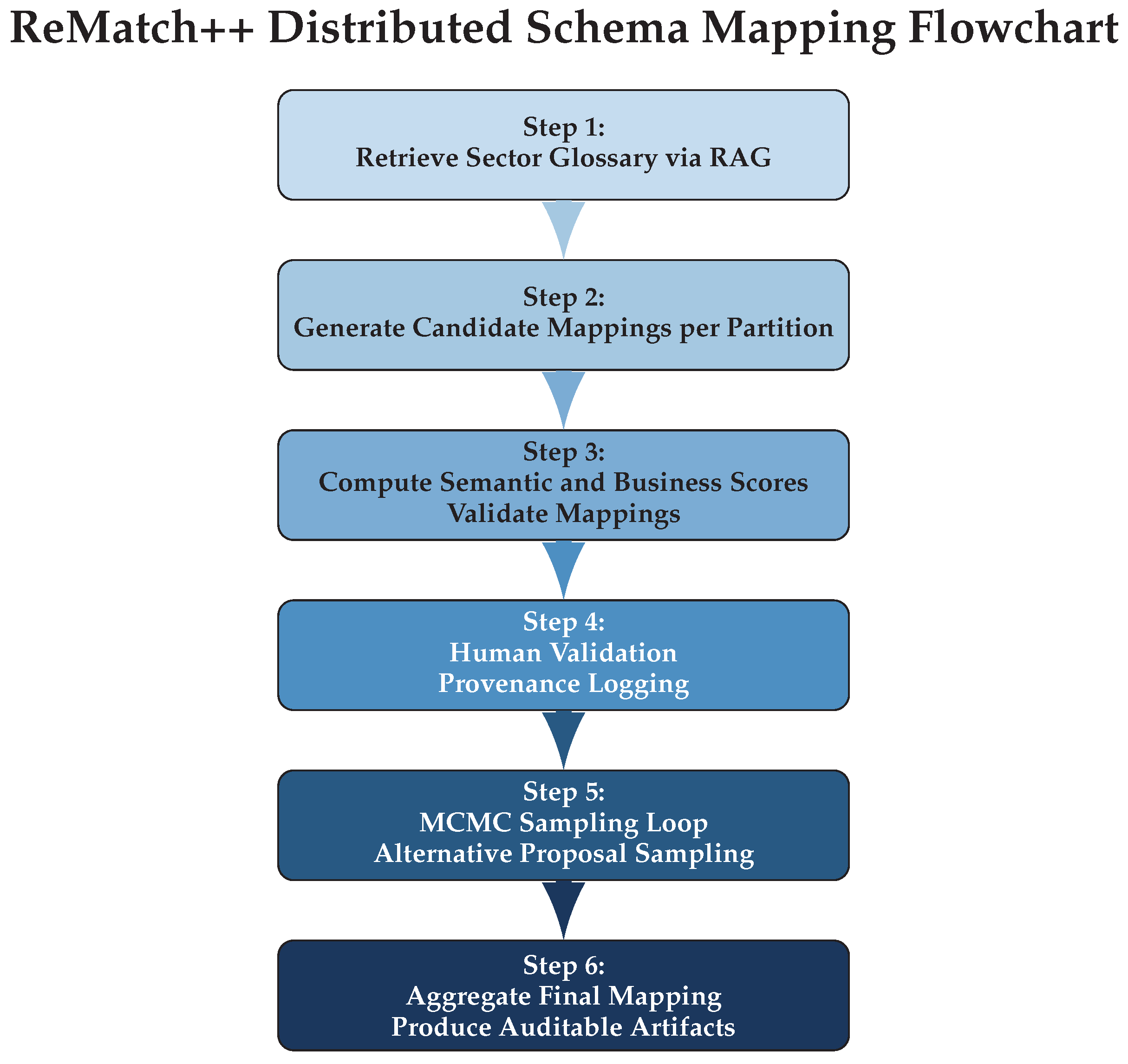

Figure 1, while the inner workings are given in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 ReMatch++ Distributed Schema Mapping via LLM and MCMC |

- Require:

Source schema S, target schema T, distributed dataset partitions - 1:

Retrieve distributed, sector-specific glossary via retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) - 2:

for each partition in parallel do - 3:

Generate candidate mappings - 4:

for each mapping do - 5:

Compute semantic score and business weight - 6:

- 7:

if mapping m passes deterministic Spark validators then - 8:

Propose m for human validation; log provenance - 9:

end if - 10:

end for - 11:

end for - 12:

for do ▹ MCMC sampling loop for uncertainty - 13:

Sample alternative mapping proposals via proposal kernel - 14:

Compute SWMC for sample t: - 15:

Store all accepted proposals and scores - 16:

end for - 17:

Aggregate final mapping, credible SWMC intervals, and produce auditable ETL artifacts

|

The procedure operates by first extracting relevant domain knowledge, then proposing mappings in parallel using LLMs and Spark computation. Scoring combines semantic and business criteria. All proposals are validated, versioned, and presented for expert review, with uncertainty sampling providing credible intervals.

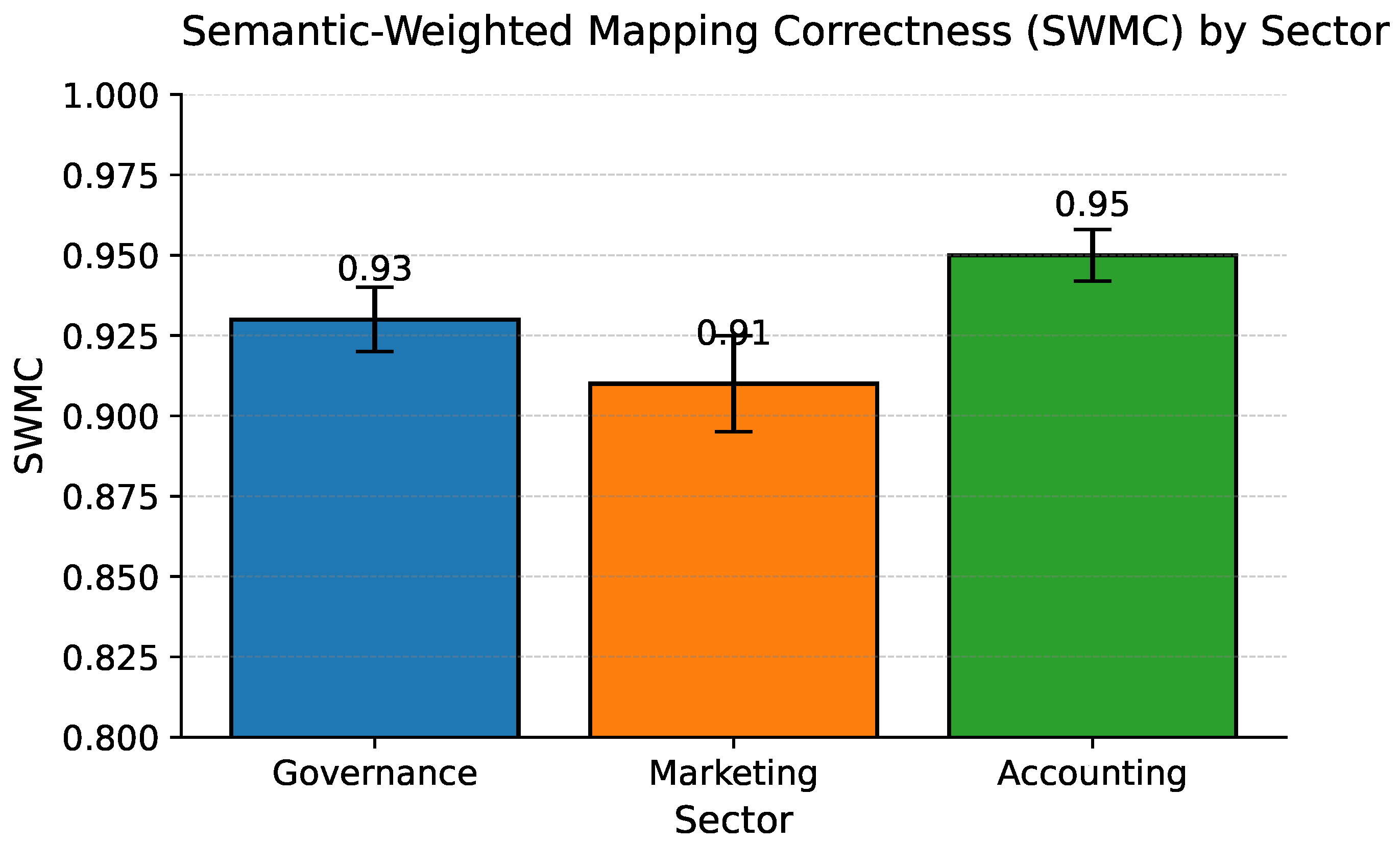

Evaluation: The principal evaluation metric for ReMatch++ is the Semantic-Weighted Mapping Correctness (SWMC), formally defined as

where

denotes the business-critical importance of the

i-th mapping,

is the indicator function for mapping correctness, and

measures the semantic distance for mapping

. To rigorously estimate mapping reliability, we report the

credible interval for SWMC, as derived from MCMC posterior sampling over candidate mappings.

4.2. Consent-Aware Entity Resolution (C-ER) and Policy Classifier

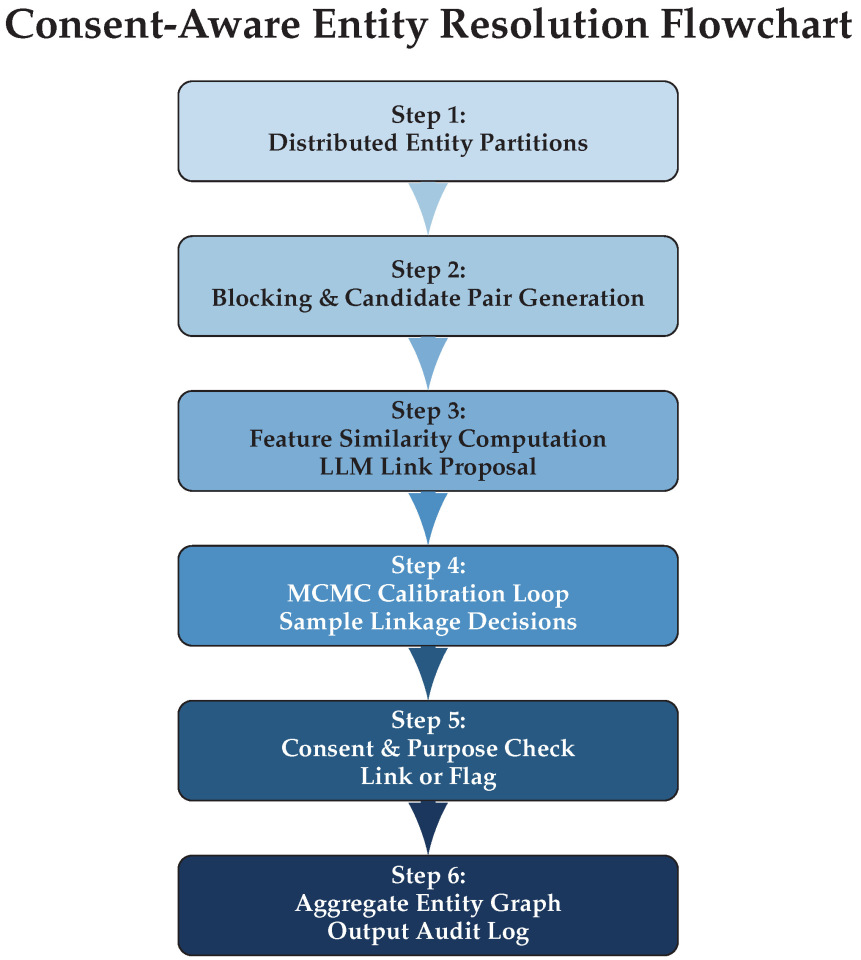

In this section, we present the Consent-Aware Entity Resolution (C-ER) algorithm, which constructs high-fidelity identity graphs compliant with sector- and purpose-based consent policies. Our approach integrates distributed processing via Apache Spark and quantifies model uncertainty using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. This framework is designed for scalability, explainability, and regulatory compliance across digital governance, marketing, and accounting datasets. The architecture of the algorithm is given in

Figure 2 while the inner workings are given in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Consent-Aware Entity Resolution (C-ER) |

- Require:

Distributed entity dataset partitions , purpose/consent policies - 1:

for each partition in parallel do - 2:

Block entities with composite feature hashing in Spark - 3:

for each candidate pair do - 4:

Compute feature similarity and context vector - 5:

Use LLM to propose link probability and rationale - 6:

for do ▹ MCMC calibration loop - 7:

Sample link decision (calibrated by in-context features) - 8:

if and then - 9:

Link ; tag with purpose/confidence; update graph - 10:

else - 11:

Flag or deny linkage; record for governance compliance - 12:

end if - 13:

end for - 14:

end for - 15:

end for - 16:

Aggregate entity graph and audit logs; output confidence summaries from MCMC chains

|

The procedure efficiently partitions and blocks large datasets, and then proposes candidate links through a combination of text-based features and LLM predictions. It subsequently leverages MCMC sampling to quantify linkage uncertainty and calibration. All link proposals, denials, and rationales are transparently logged for audit and regulatory purposes. The residual risks from blocking, such as missed cross-block matches or over-dense blocks, are analyzed as failure modes in

Section 6, along with mitigation strategies.

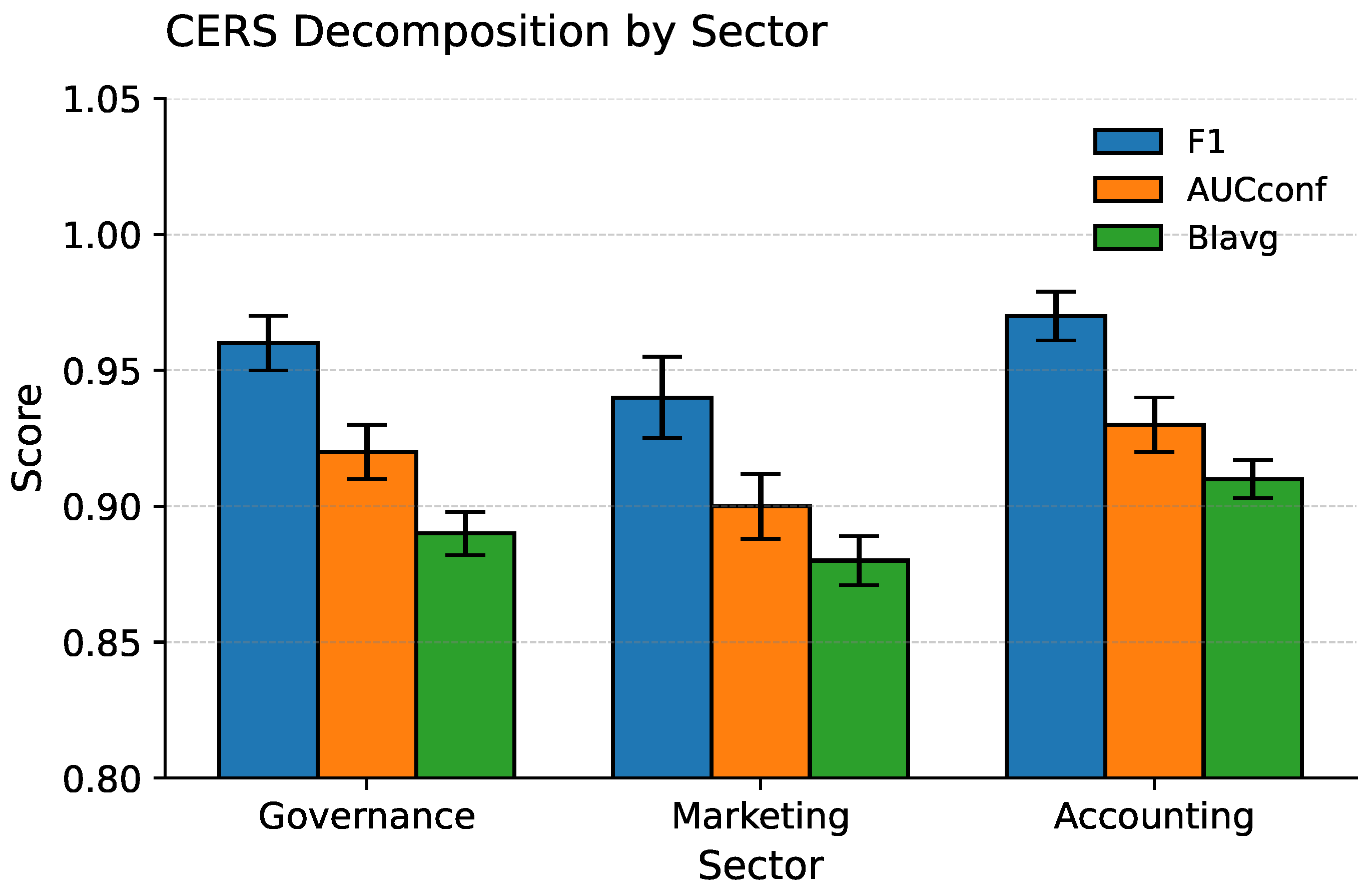

Evaluation: Algorithm performance is assessed using the Consent-aware Entity Resolution Score (CERS), defined as

where

denotes pairwise clustering accuracy,

is the area under the confidence calibration curve, and

is the average business impact of link decisions. Credible intervals for these metrics are derived from the posterior distribution sampled via MCMC:

4.3. Doc2Ledger-LLM: Multimodal Extraction with Validators

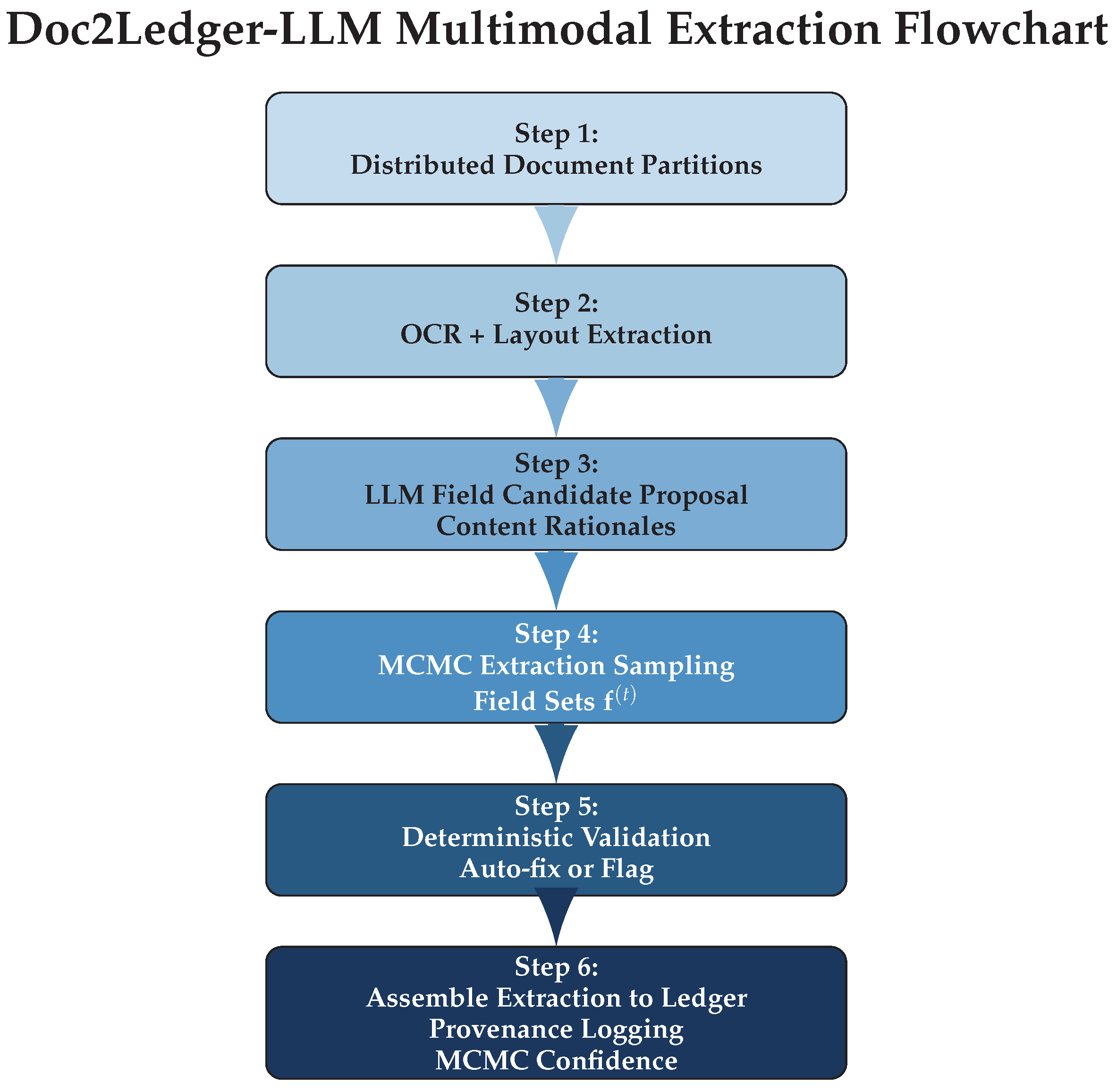

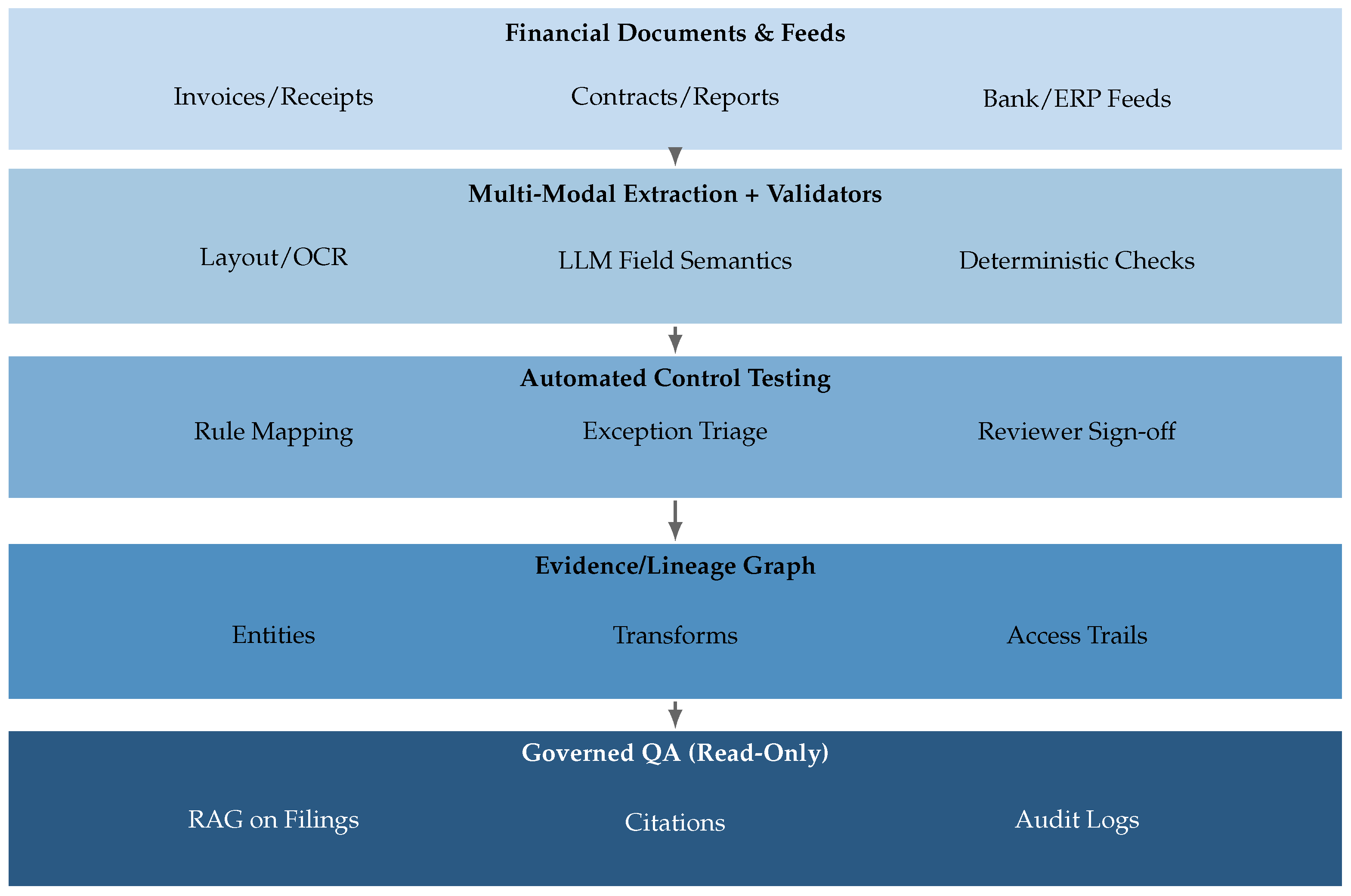

In this section, we propose the “Doc2Ledger-LLM” algorithm, a robust multimodal document-to-ledger pipeline that is both distributed and uncertainty-aware. The design integrates Spark for large-scale document partitioning, large language models (LLMs) for field extraction, and MCMC sampling for quantifying extraction and validation reliability. This method is specifically tailored for accounting and audit workflows requiring traceable and reproducible evidence. The graphical representation of the proposed method is given in

Figure 3 while the inner workings are given in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 Doc2Ledger-LLM Multimodal Distributed Extraction |

- Require:

Distributed document partitions , validator set - 1:

for each partition in parallel do - 2:

for each document do - 3:

Apply OCR and extract layout structure - 4:

Use LLM to propose key field candidates and content rationales - 5:

for do ▹ MCMC extraction chain - 6:

Sample field extraction set using LLM context and layout priors - 7:

for each field do - 8:

if field f passes deterministic checks in (e.g., totals, VAT, master data) then - 9:

Record f as valid; generate and log provenance hash - 10:

else - 11:

Propose auto-fix or flag f; route for human review - 12:

end if - 13:

end for - 14:

end for - 15:

Assemble and post full extraction to ledger with provenance - 16:

end for - 17:

end for - 18:

Aggregate results; return confidence intervals from MCMC sampling

|

The Doc2Ledger-LLM process begins with distributed OCR and layout parsing of scanned or digital documents, followed by LLM-driven candidate field extraction for each document. MCMC sampling yields a chain of plausible field sets, allowing the estimation of extraction uncertainty and reliability. Each extracted data item is validated against deterministic business rules (totals, tax, and master entity lookups) coded in Spark, with failures prompting either an automatic correction or a request for human oversight. Ledger postings are recorded with hash-based provenance across all decision points, providing evidence-grade traceability that achieves near-complete coverage in our experiments.

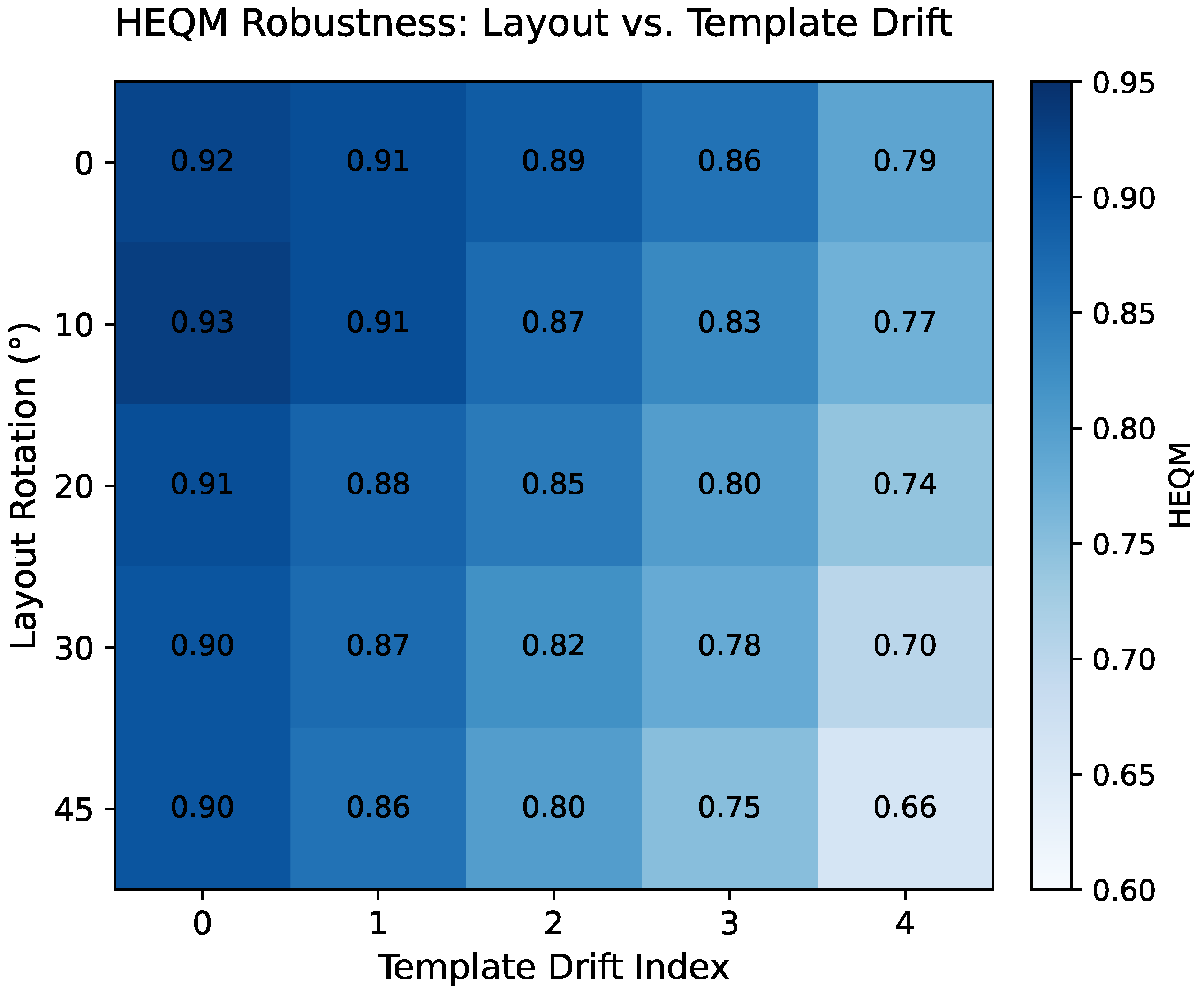

Evaluation: The extraction- and ledger-writing performance is quantified using the Hierarchical Extraction Quality Metric (HEQM),

where

is the field/business importance,

is field-level extraction accuracy, and

is the empirical variance from the MCMC samples. Provenance Fidelity Score (PFS) and other coverage assurance metrics are also reported, with all scores accompanied by

credible intervals estimated from the sample chains.

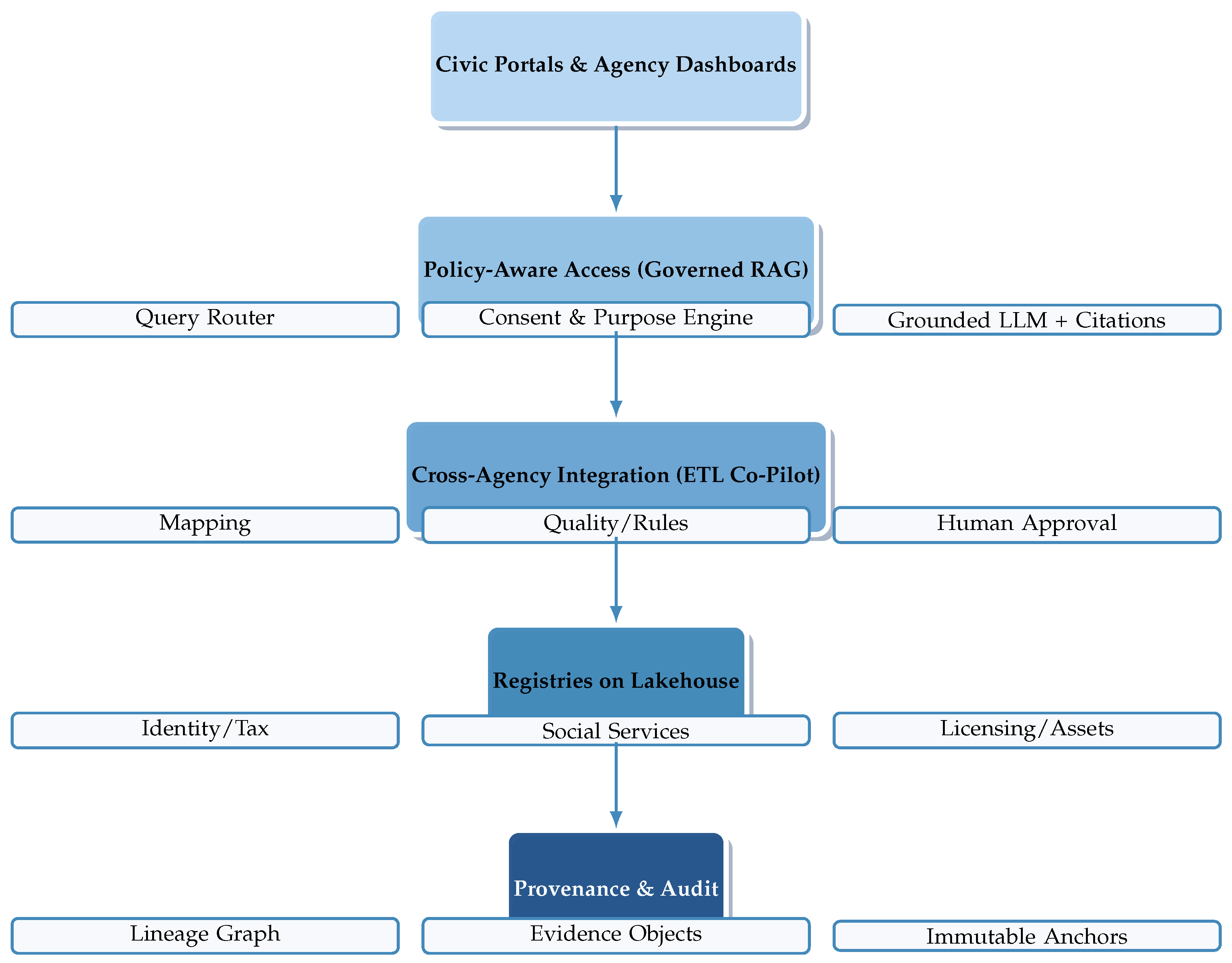

5. Architecture Patterns

This section formalizes three implementation blueprints through which Large Language Models (LLMs) enable intelligent big data management across digital governance, marketing, and accounting. The patterns are organized from

access, to

transformation, to

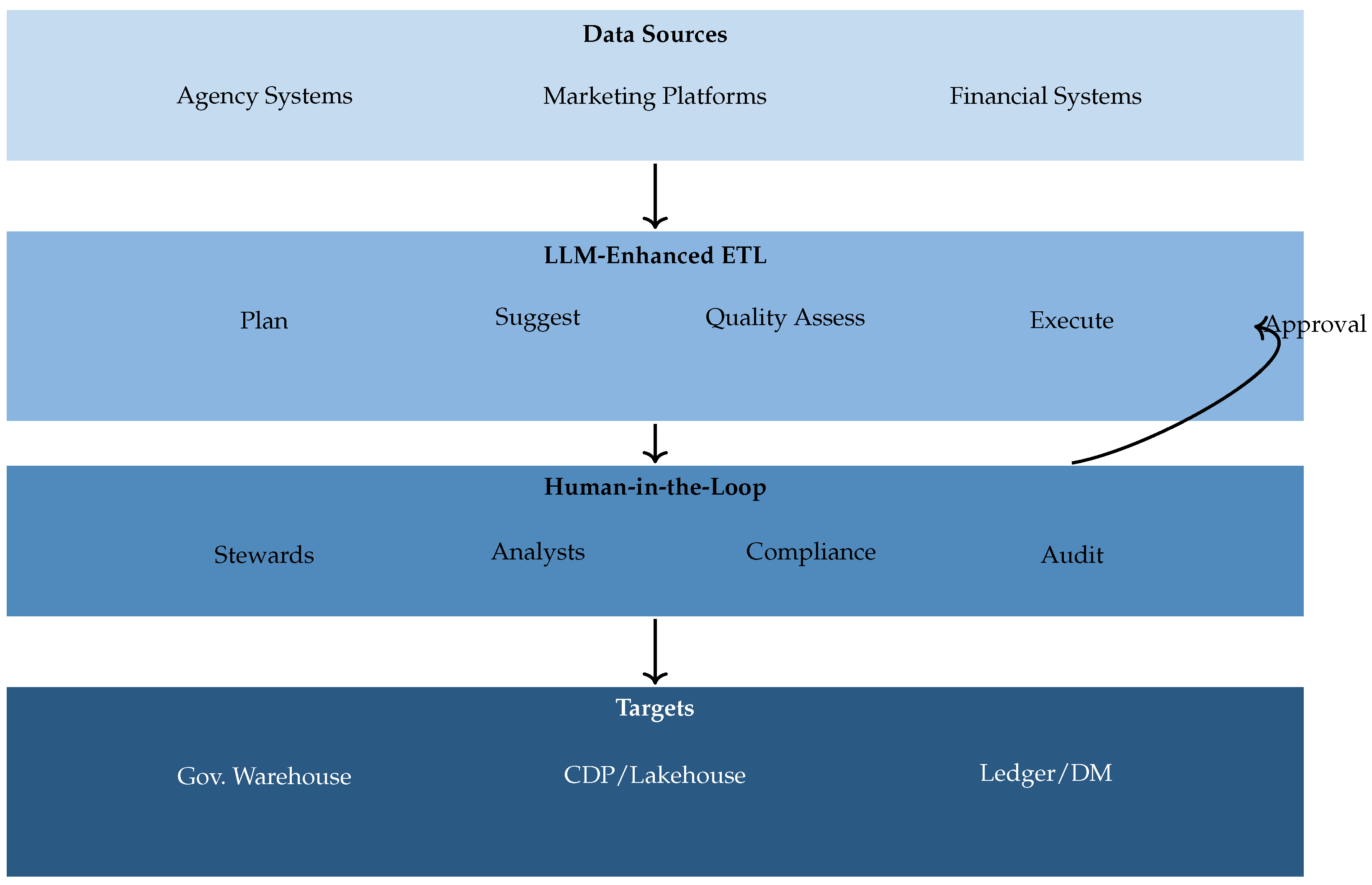

assurance, thereby tracing how organizations first expose governed, explainable access to existing assets (Pattern A), then accelerate ingestion and transformation under human control (Pattern B), and finally institutionalize evidence-grade provenance (Pattern C). Each pattern is presented with a concise rationale, core components, governance considerations, sector-specific adaptations, and a compiler-safe TikZ illustration.

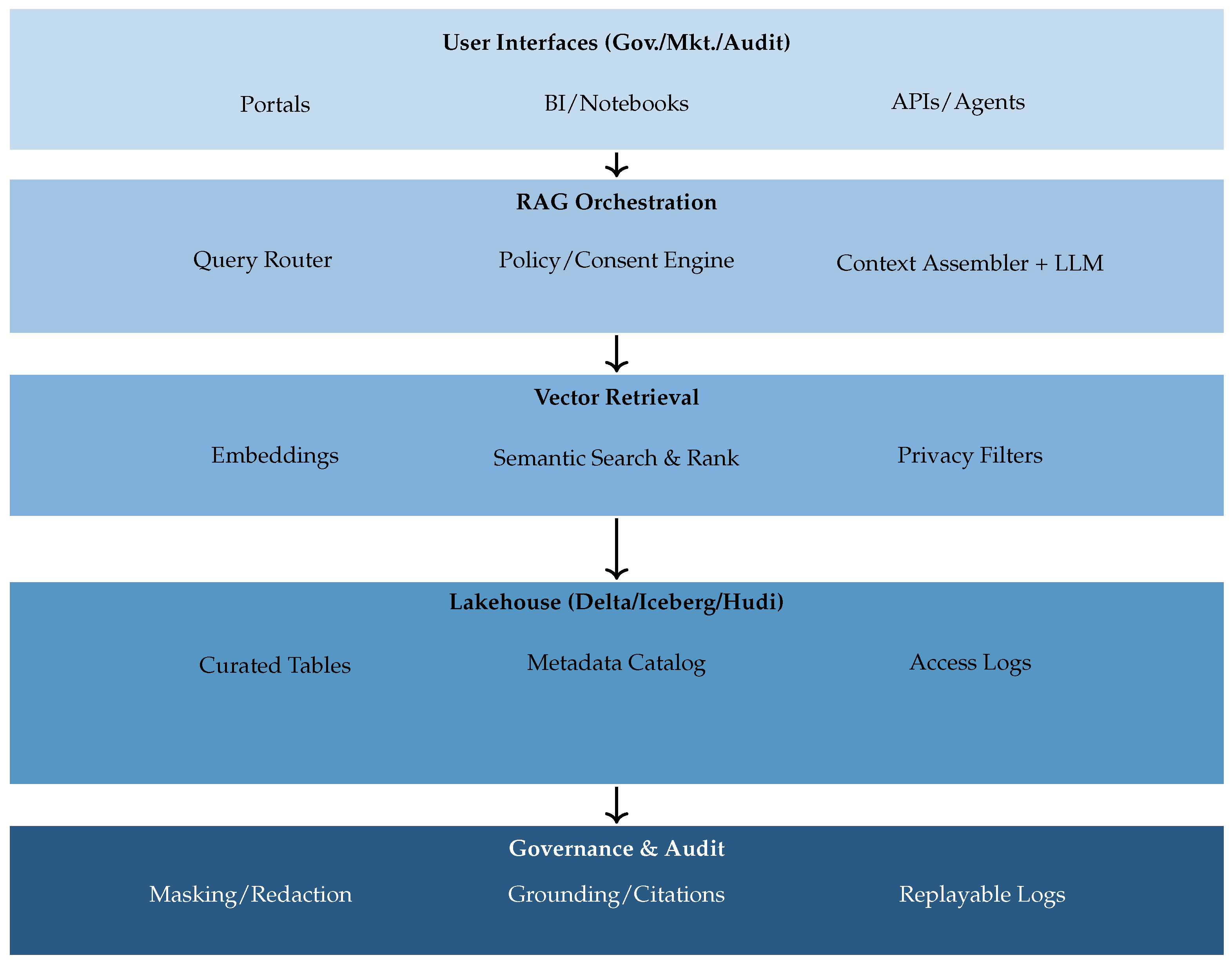

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 visualize the architectures.

5.1. Pattern A: RAG-over-Lakehouse for Governed Question Answering

Rationale. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) over a lakehouse foundation provides natural language access to enterprise data while enforcing

least-privilege, consent, and policy constraints. This pattern marries open table formats with ACID guarantees and schema evolution [

98,

99] to a policy-aware RAG stack [

100,

101,

102], augmented with enterprise trust controls for masking, grounding, and logging [

103]. By separating retrieval from generation, the architecture improves factuality and auditability without duplicating data [

101].

Core components. (i) A lakehouse foundation (e.g., Delta, Iceberg, Hudi) exposes versioned, governed tables and logs for both batch and streaming ingestion [

98,

99]. (ii) Semantic indexing and vector storage create embeddings of documents and structured records, binding privacy labels and access metadata to chunks for policy-time filtering [

104]. (iii) A RAG orchestration engine routes queries, enforces consent and purpose-limitations, assembles grounded contexts, and prompts LLMs with citations [

101]. (iv) A governance/audit layer provides immutable interaction logs, response rationales, and replayable retrieval traces for compliance and incident response [

88,

91,

103]. Although, while the lakehouse architecture avoids duplication of primary data, semantic indexing necessarily introduces embedding replicas; these are governed via the same access, retention, and purpose-limitation controls as the underlying tables.

Governance and sector adaptations. Digital governance requires transparency-by-design and explainable responses suitable for public oversight [

88,

91]. Marketing emphasizes consent-aware retrieval across customer knowledge and partner documents [

88,

91]. Accounting prioritizes access segregation, sampling evidence, and documented rationales to satisfy external assurance [

103].

Performance and risks. Empirical accounts show scalable querying with schema-aware routing in large repositories [

104], while trust layers support masking and zero-retention to bound leakage. Residual risks include hallucination and privilege creep; mitigations include strict pre-generation filtering, deterministic post-validators, and full query audits [

101,

102].

5.2. Pattern B: ETL Co-Pilot at the Ingestion/Transform Stage (Human-in-the-Loop)

Rationale. Many benefits arise

before analytics: accelerating ingestion, mapping, cleansing, and enrichment under explicit human control. The ETL Co-Pilot pattern positions LLMs as suggesters of transformations while preserving determinism through validators, approvals, and replayable execution [

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112]. This pattern complements Pattern A by improving upstream data

fitness-for-use for downstream governed access.

Core components. (i) An orchestration engine triggers pipelines (batch/stream) and injects LLM checkpoints at planning and transform stages [

106,

109]. (ii) A transformation suggestion engine proposes cleanses and mappings from examples and documentation (“describe-and-suggest”), emitting machine-readable diffs [

105,

106,

107]. (iii) A quality module profiles distributions, detects violations, and explains anomalies with recommended fixes and rollback plans [

107,

108,

111]. (iv) A human-approval gateway routes high-impact changes to stewards, compliance officers, or technical reviewers, recording rationales for audit [

108,

110,

111,

112].

Governance and sector adaptations. Governments harmonize cross-agency records with statutory transparency and citizen rights in mind; marketing pipelines incorporate consent checks and preference management; accounting requires reviewer sign-off on financial transformations with segregation of duties [

105,

106,

109,

111].

Performance and risks. Organizations report substantial reductions in manual effort and high automation rates for routine transformations while retaining near-perfect accuracy for critical financial workflows [

105,

106,

107,

108]. Primary risks involve over-automation and validator gaps; mitigations include confidence thresholds, mandatory reviews at risk cutoffs, and change replay logs [

109,

110,

111,

112].

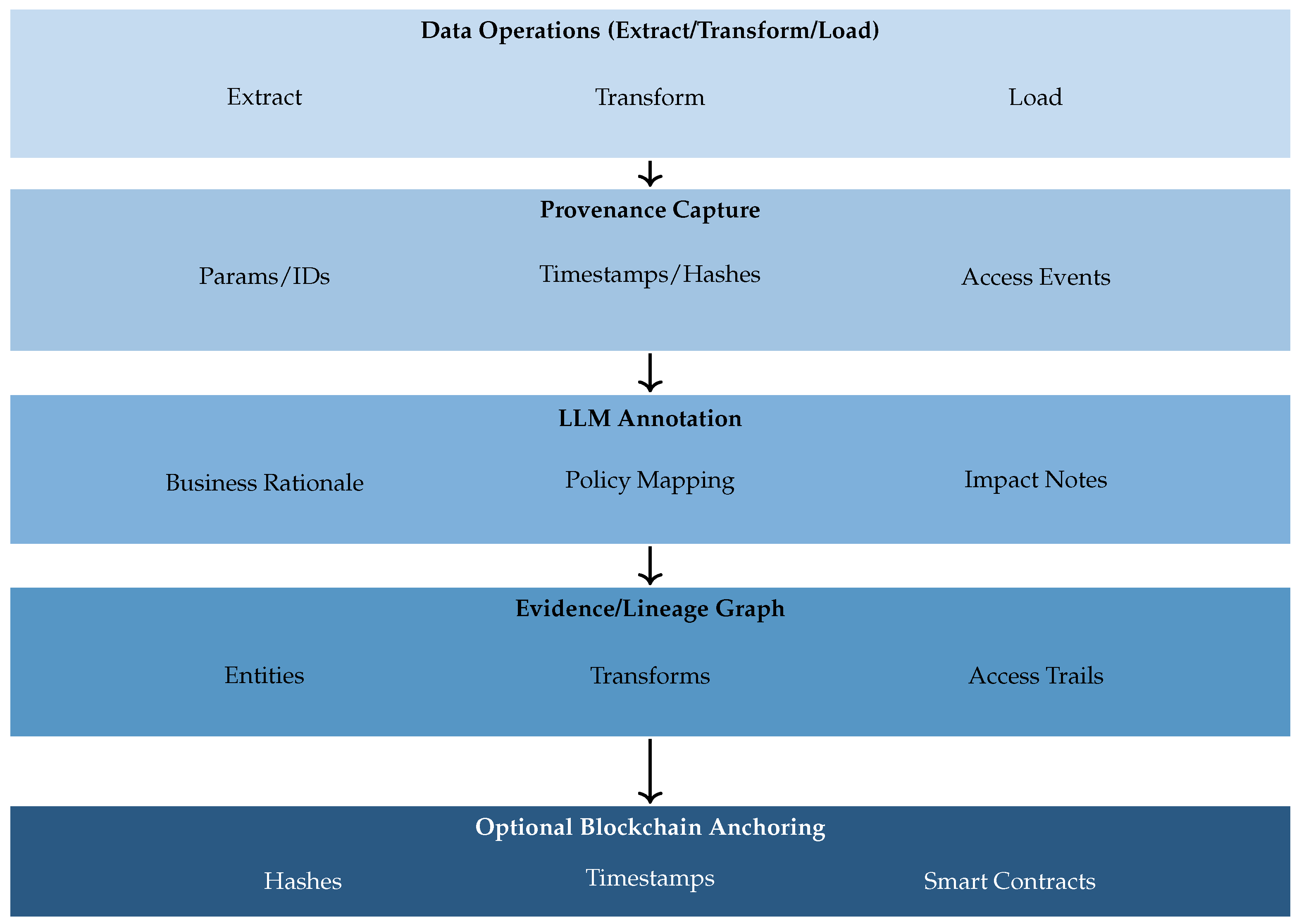

5.3. Pattern C: Lineage & Evidence Graph with LLM Annotation (Optional Blockchain Anchoring)

Rationale. To make access and transformation

auditable, provenance must be captured, enriched, and attested. This pattern instruments data operations, uses LLMs to convert raw metadata into human-readable evidence, represents relationships in a graph, and optionally anchors critical events to a distributed ledger for tamper-evidence [

12,

19,

20,

22,

100,

113,

114,

115,

116]. It closes the loop with Patterns A and B by providing replayability and independent verifiability.

Core components. (i) A provenance capture engine records parameters, timestamps, identities, and transformation code paths with minimal overhead [

12,

19,

20]. (ii) An LLM annotation service explains

why transformations occurred, mapping to business rules and regulatory obligations [

45,

117,

118]. (iii) A graph database represents entities, transformations, and access trails for impact analysis and change management [

12,

19,

20,

22]. (iv) An optional blockchain anchoring layer timestamps hashes of evidence objects and critical events, enabling later integrity verification [

100,

113,

114,

115,

116].

Governance and sector adaptations. Public agencies require explainable decision trails and citizen-data transparency; marketing benefits from dynamic consent lineage; accounting relies on replayable evidence chains and immutable trails for continuous audit [

100,

102,

113,

114,

115].

Performance and risks. Prior work demonstrates enterprise-scale lineage with modest overhead and sub-second graph queries [

12,

20,

22]. Optional blockchain anchoring adds latency but enhances immutability; gas- and throughput-optimized designs mitigate operational costs in practice [

100,

113,

115]. Risks include incomplete capture and stale explanations; mitigations include hybrid capture (static + runtime), coverage SLOs, spot audits, and attestation schedules [

12,

20,

45,

117].

5.4. Cross-Pattern Integration and Deployment Progression

Patterns are intentionally composable. Many organizations begin with Pattern A to deliver immediate, governed access, then adopt Pattern B to reduce upstream friction in ingestion and transformation, and finally institutionalize Pattern C for durable assurance and continuous audit. Shared services—LLM serving, embedding indices, catalogs, policy/consent engines, and logging—enable cost-effective reuse across patterns [

103]. In regulated environments, a prudent progression is to (i) stand up governed RAG with strict pre-generation filters and replayable logs [

101,

102], (ii) introduce ETL co-pilots with confidence thresholds and mandatory approvals at risk cutoffs [

105,

106,

107,

111,

112], and (iii) deploy lineage/evidence graphs, optionally anchored to a ledger where immutability is paramount [

12,

20,

22,

113,

114,

115].

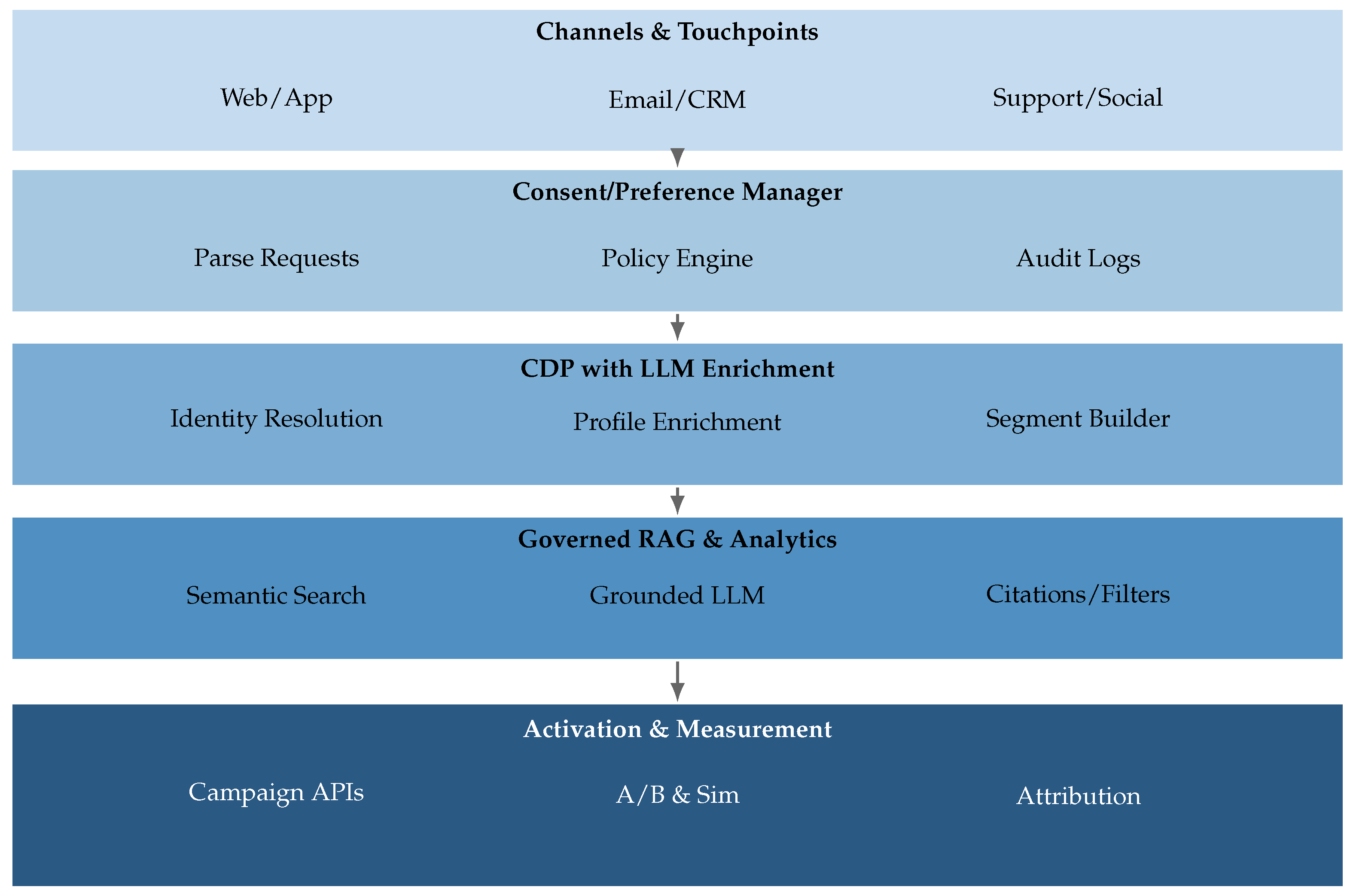

6. Sectoral Implementations: Evidence, Effective Practices, and Failure Modes

Building on

Section 2 and

Section 5, we examine implementations in digital governance, digital marketing, and accounting/audit. We shift from capability to constraint. First, we discuss clear practices that align with each sector. Then, we explore common failure modes that stem from legal, organizational, or technical mismatches. Across sectors, assurance focuses on four control points: consent, policy enforcement, provenance, and human oversight. These are applied at the access, transformation, and provenance layers.

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate these points of insertion.

6.1. Digital Governance

Effective practices. LLMs are highly flexible models, but in digital governance they add the most consistent value when that flexibility is constrained to policy-aligned data plumbing and explicitly bounded tasks [

119,

120]. Statutory corpora support high-precision policy tagging and regulatory classification; systems such as LegiLM seed automated workflows for GDPR-oriented detection [

88,

121,

122]. “Citizen 360” views remain tenable only under strict consent and purpose limitation with policy-aware lakes and rationale-bearing retrieval logs [

87,

123,

124,

125].

Failure modes. (i)

Insufficient provenance: reasoning not anchored in executable lineage rarely meets auditability; immutable logging and site-spanning evidence queries mitigate at non-trivial integration cost [

101,

114,

122,

126,

127,

128]. (ii)

Audience-aligned explainability: authorities must justify outcomes across jurisdictions; cross-border harmonization elevates requirements engineering and validation burdens [

122,

125,

129]. These motivate replayable, consent-aware access (Pattern A), human approval at transformation points (Pattern B), and evidence-grade provenance (Pattern C).

6.2. Digital Marketing

Effective practices. LLM-augmented CDPs improve identity resolution and enrichment as third-party signals recede [

130]. Hybrid association (LLM-derived features + probabilistic clustering) yields higher segment fidelity and activation quality [

131,

132]. Large-scale consent/preference parsing is feasible when free-form requests are translated into enforceable access policies with low latency [

87,

131,

133]. LLM-assisted feature engineering and simulation accelerates design while reducing reliance on risky online tests [

132,

133].

Failure modes. Profile drift from over-weighted inferred traits degrades personalization, amplified by aggressive compression/merging [

134,

135].

Manipulative content risk emerges as conversion-centric prompts drift toward dark patterns [

136].

Consent scope creep arises when retrieval/enrichment extend beyond authorized purposes; progressive prompting must be fenced by policy engines with comprehensive logging [

87,

131,

137]. These support governed access (Pattern A), co-piloted transformations with review (Pattern B), and explicit consent lineage (Pattern C).

6.3. Accounting & Audit

Effective practices. Accuracy improves when multimodal extraction (layout/OCR + LLM field semantics) is combined with domain validators; neural OCR and layout-aware models outperform legacy pipelines [

92,

100,

138]. Memory-augmented and agentic designs raise domain-specific extraction performance and harden AP automation [

94,

100,

139]. Automated control testing leverages LLMs for relation extraction and rule mapping under reviewer oversight [

140,

141,

142,

143]. Continuous evidence collection pairs governed retrieval with finance-specific QA over hierarchical/tabular reports (e.g., 10-K) [

141,

142,

144,

145].

Failure modes. Reproducibility vs. probabilism: auditors require identical outputs for identical inputs; randomness must be bounded and determinism enforced at control points [

141,

146].

Sampling bias/drift: historical training can miss emergent fraud or rules [

141,

147].

Evidence sufficiency: black-box rationales conflict with ISA/SOX documentation; justification artifacts, executable lineage, and human sign-off are mandatory [

122,

141]. These favor Pattern B (validators/approvals) and Pattern C (evidence graphs/attestation), with Pattern A reserved for read-only, consent- and role-governed queries.

Synthesis Across Sectors

All three domains adopt governed LLM components but differ in admissibility thresholds. Governance prioritizes transparency and legal interoperability, making consent-aware access and replayable provenance non-negotiable [

87,

114,

121,

122,

123,

125,

126,

129]. Marketing emphasizes agility under consent with explicit consent lineage and policy-constrained enrichment to avoid manipulation and scope creep [

131,

133,

136,

137,

148]. Accounting requires determinism and evidentiary sufficiency via validators, sign-offs, and executable lineage [

138,

140,

144,

149,

150]. In practice, the composition of Pattern A (governed access), Pattern B (human-in-the-loop transformation), and Pattern C (evidence-grade provenance) yields sector-fit assurance.

7. Evaluation and Metrics

7.1. Data Management Performance Indicators

7.1.1. Schema Mapping Accuracy

Schema mapping accuracy is a foundational indicator for LLM-enabled data integration. We propose the

Semantic-Weighted Mapping Correctness (

SWMC), which extends precision–recall-style measures by incorporating semantic distance:

where

denotes business-criticality weight for mapping

i,

is the indicator of correctness,

and

are predicted and ground-truth mappings, and

is an embedding-based semantic distance between source field

and target field

[

72,

73]. Contemporary implementations report SWMC in the range

–

across domains; for example, a ReMatch-like framework attains

without predefined training data. The semantic term captures partial-correctness cases in which mappings are semantically near despite syntactic deviation [

72,

78].

7.1.2. Entity Resolution Precision–Recall–F1

Entity resolution requires balanced evaluation of precision, recall, and clustering quality. We define the

Contextual Entity Resolution Score (

CERS):

with

,

the area under the confidence calibration curve, and

the average business impact score of resolved entities. Weights

enable sector-specific prioritization [

79,

81]. State-of-the-art systems exceed

; in-context clustering yields up to

relative gains over pairwise methods and reduces complexity

, while calibration exposes uncertainty biases for risk-based oversight [

79,

81,

82,

110].

7.1.3. Constraint Repair Rate

To assess data-quality remediation beyond detection, we propose the

Automated Quality Enhancement Index (

AQEI):

where

is a criticality weight for quality dimension

j,

the successful repair rate,

the false-positive intervention rate, and

the detected issue frequency. The numerator penalizes over-aggressive corrections that introduce defects [

84,

85]. Reported

values range

–

; financial data typically achieves

–

(clearer constraints), while unstructured text yields

–

[

84,

85].

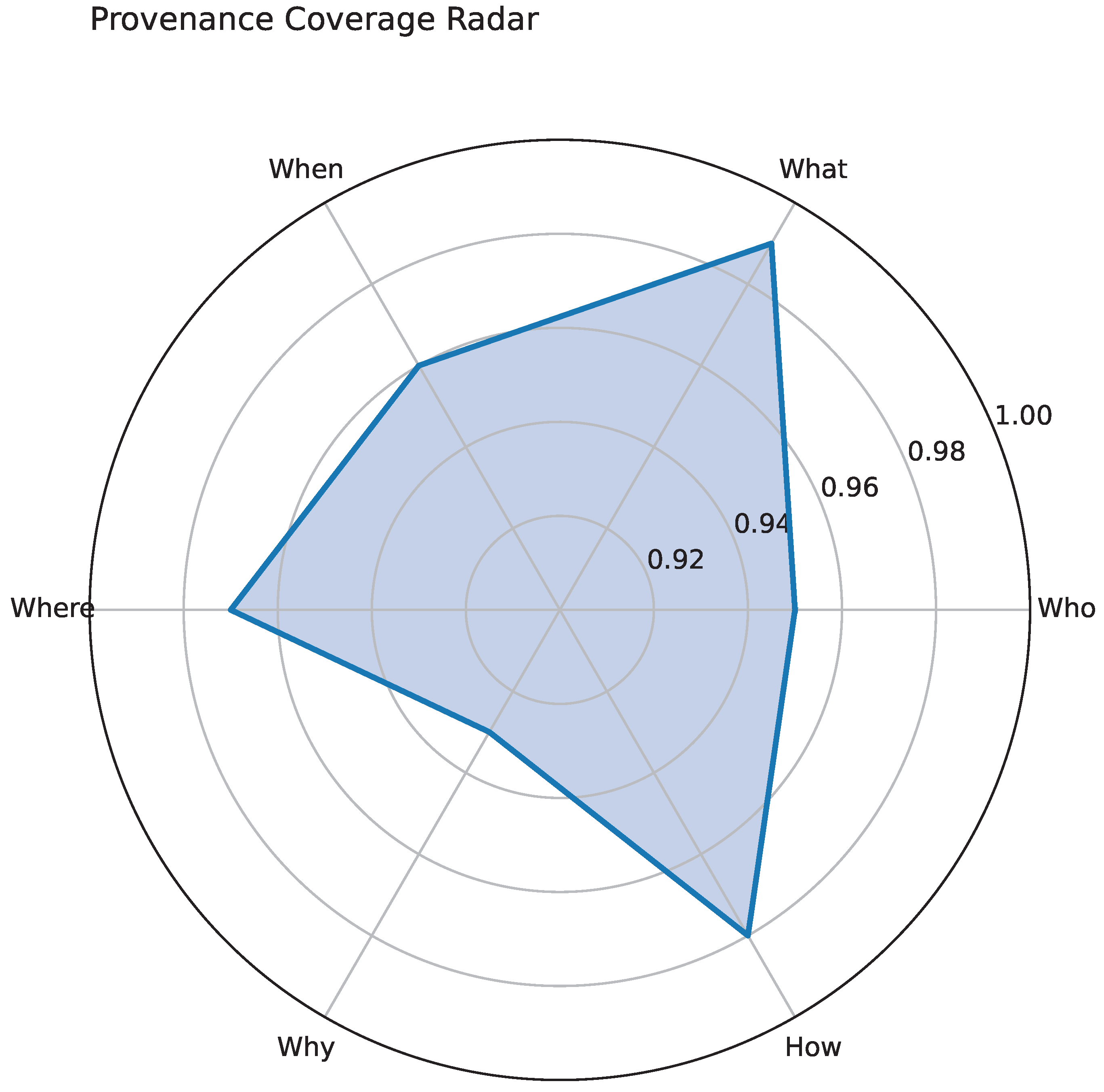

7.1.4. Lineage Coverage Completeness

Provenance evaluation should aggregate multiple facets. We define the

Provenance Fidelity Score (

PFS):

where

C is coverage (fraction of transformations documented),

A annotation accuracy against expert validation,

S semantic richness (NLG quality), and

V verifiability (e.g., cryptographic integrity). Weights reflect sector priorities [

12,

20]. State-of-the-art systems score

–

; blockchain anchoring improves

V (

) at modest latency (5–

) [

20,

22,

114,

126]. Governance often emphasizes

C and

V (e.g.,

,

); marketing may favor

S for stakeholder comprehension (e.g.,

).

7.1.5. Document Extraction F1

For document-to-structure extraction we propose the

Hierarchical Extraction Quality Metric (

HEQM):

where

is field-level F1 for category

k,

is business-importance weight,

is extraction variance across instances, and

a variance-penalty strength. The variance term rewards consistency under format drift [

92,

94,

94]. Multimodal systems attain

–

on financial documents; memory-augmented designs improve

over single-LLM prompts, yet layout rotations beyond safe angles degrade

by 15–

[

93,

94,

94].

7.1.6. RAG Answer Faithfulness

For retrieval-augmented generation, we define the

Grounded Response Integrity Score (

GRIS):

with weights

tuned to sector risk [

103,

142,

151]. Enterprise deployments report

on domain repositories; trust-layered frameworks exceed

confidence across sustainability, finance, and operations. Governance prioritizes faithfulness (e.g.,

), while marketing often prioritizes completeness (e.g.,

) [

103,

151,

152].

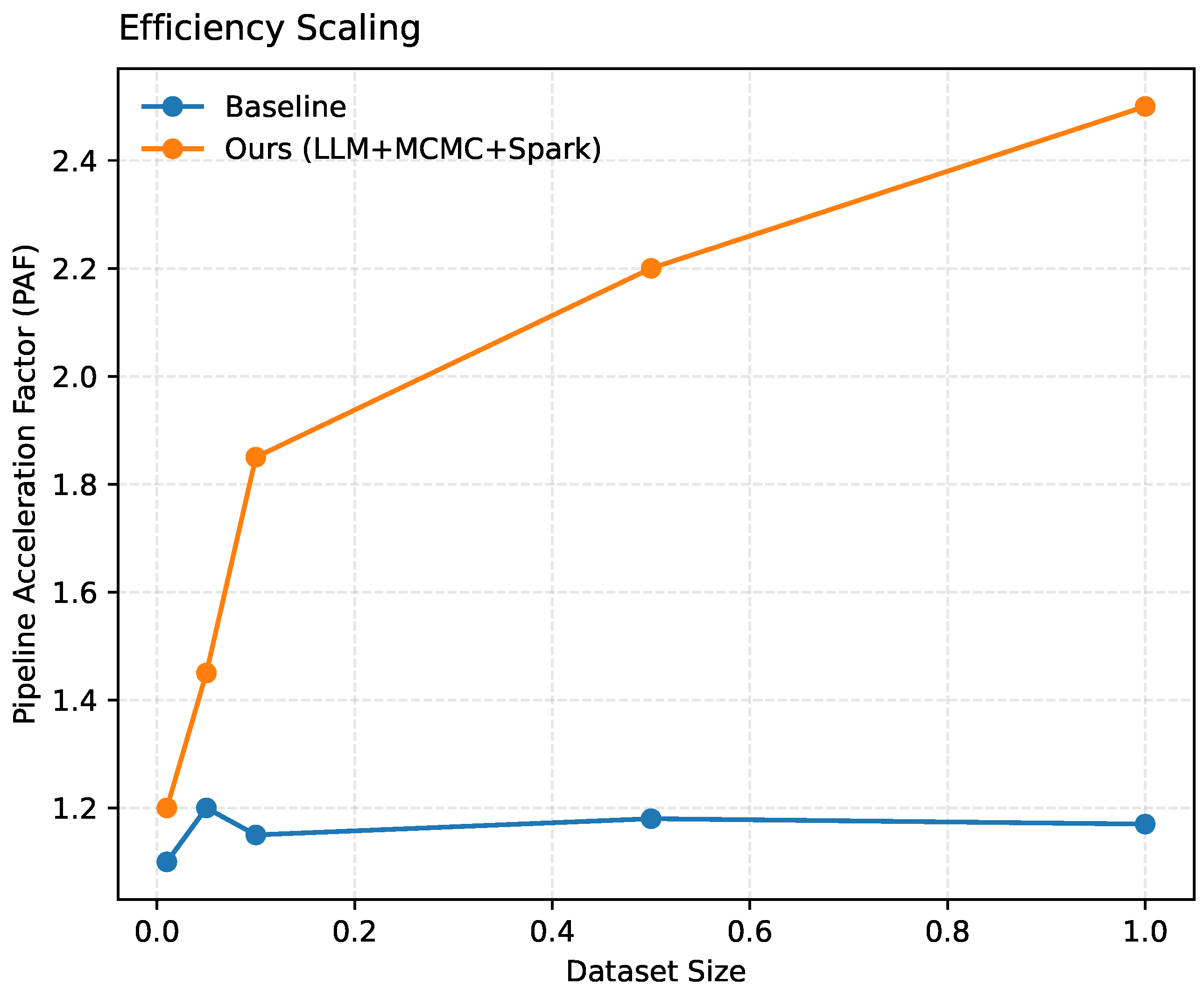

7.2. Operational Efficiency Metrics

7.2.1. Time-to-Ingest Reduction

We define the

Pipeline Acceleration Factor (

PAF):

where

and

are baseline and LLM-enhanced ingestion times, and the rework factor discounts shifted workload [

153,

154]. Deployments report

–

; event-driven architectures sustain

KB/s for >100 MB payloads with <8% variance. Cloud-native designs reduce ingestion time 40–

via schema-agnostic processing and auto-configuration [

109,

153,

154,

155].

7.2.2. Rework Reduction Rate

We propose the

Defect Prevention Index (

DPI):

where

counts defects escaping downstream,

is correction cost,

a cost-normalization factor, and

the historical defect baseline. Production systems yield

–

; proactive anomaly detection attains

recall on injected pipeline faults with low false alarms, and ML-based monitors improve prevention 35–

over rules [

156].

7.2.3. Human Review Minutes Saved

We define the

Quality-Preserved Efficiency Gain (

QPEG):

where

are review minutes saved,

the quality maintenance ratio, and

quality escapes;

penalizes downstream impact [

108,

111,

157]. Human-in-the-loop platforms report 40–

net productivity gains at ≥99% decision quality; adaptive learning improves QPEG 15–

over 12 months [

107,

108,

110,

158].

7.3. Governance Assurance Metrics

7.3.1. Audit Findings Resolution Rate

We introduce the

Compliance Deficiency Closure Index (

CDCI):

where

weights finding severity,

indicates on-time closure, and

penalizes newly introduced gaps [

88,

89,

159]. Deployed systems score

–

with 60–

manual-review reduction; LegiLM achieves

precision in GDPR detection, enabling proactive prevention [

86,

88].

7.3.2. Privacy Incidents Avoided

We define the

Privacy Risk Mitigation Score (

PRMS):

where

is incident probability without intervention,

the detection lead time,

a steepness parameter, and

the consequence severity [

86,

87]. Advanced PII detectors prevent 85–

of potential incidents; multi-stage (rules+LLM) pipelines suppress false negatives to <5% while keeping false positives at 10–

[

87].

7.3.3. Compliance Timeliness Achievement

We define the

Regulatory Punctuality Index (

RPI):

where

weights requirement importance and

is lateness (negative if early);

controls penalty severity [

89,

89]. Automated preparation systems reach

with 40–

reporting-effort reduction; NLP verification detects likely violations pre-deadline [

89,

160].

7.4. Strategic Decision Impact Indicators

7.4.1. Decision Cycle Time Reduction

We define the

Information-to-Action Velocity (

IAV):

where

is time from request to execution,

is outcome quality, and

is the deployment rate of LLM-derived insights [

142,

151]. Reported gains show 45–

cycle-time reduction with stable or improved quality; natural-language query broadens access for non-technical stakeholders [

103,

149,

151].

7.4.2. Business Lift Proxies

We define the

Aggregate Business Value Score (

ABVS):

where

weights metric importance,

is improvement,

the historical variance, and

enforces statistical significance [

161]. Marketing reports ABVS gains of

–

with 15–

conversion lift; governance shows

–

on service metrics; accounting exhibits

–

on audit-efficiency indicators [

141].

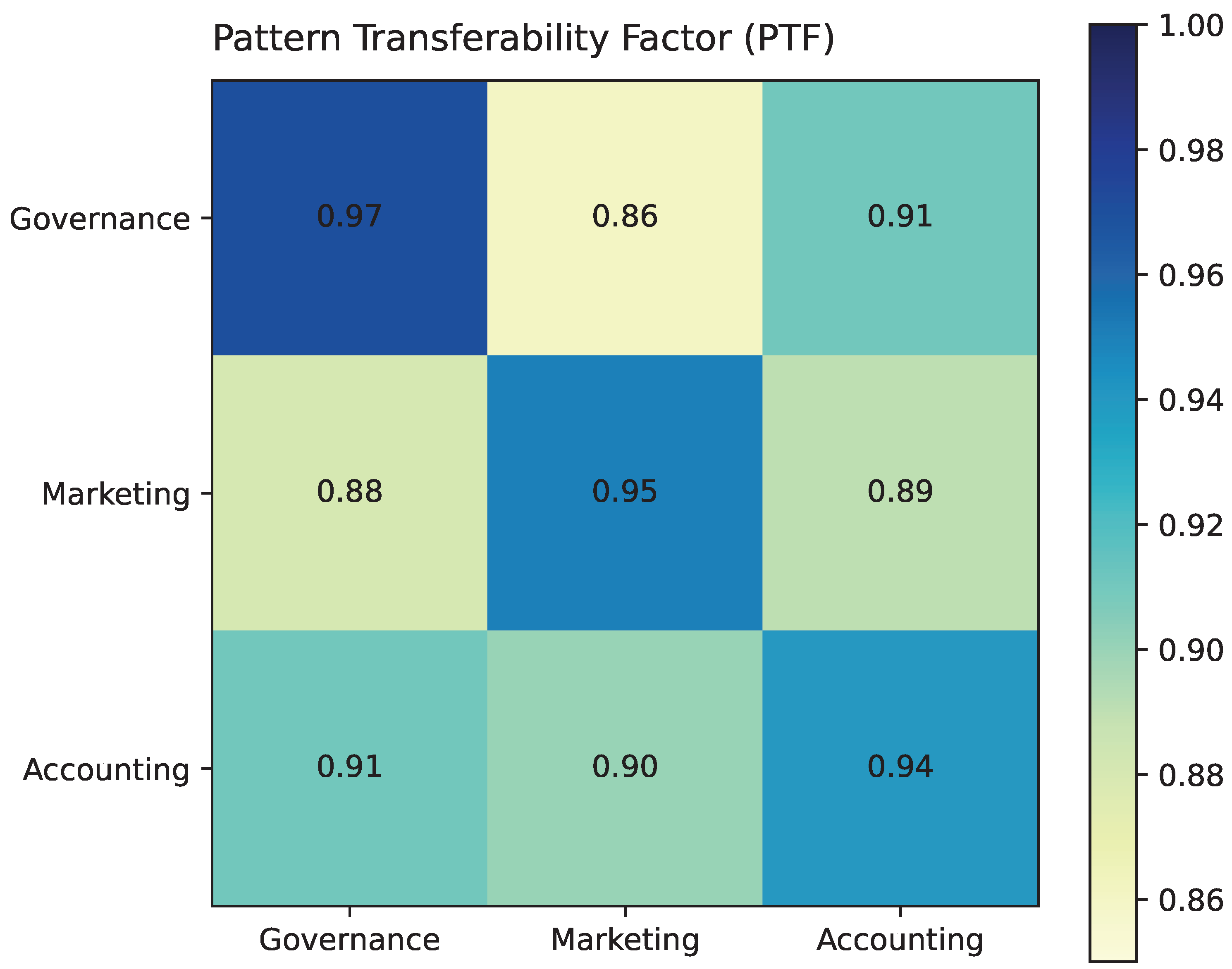

7.5. Cross-Sector Pattern Portability Framework

We formalize

Pattern Transfer Feasibility (

PTF) across sectors

:

where

measures technical compatibility,

regulatory divergence,

operational similarity, and

adaptation cost; weights reflect organizational priorities [

150,

162].

7.5.1. Technical Infrastructure Portability

Table 7 summarizes technical portability and typical adaptation requirements across sector pairs.

Overall, infrastructure elements are highly portable (mean

); base LLMs and vector stores transfer readily, while blockchain portability is tempered by sector-specific consensus and regulatory constraints [

115,

163].

7.5.2. Prompt Engineering Adaptation Requirements

Prompting is the major adaptation lever in cross-sector transfer. We distinguish three tiers [

14,

165]:

Tier 1 (PTF ) universal prompts (data quality checks, format validation, basic entity extraction; ≤10% edits) [

149];

Tier 2 () domain-contextual prompts (schema mapping, semantic relations, constraints; 25–

edits with terminology/examples) [

72,

73];

Tier 3 (PTF ) sector-specific prompts (compliance, risk, domain reasoning; ≥60% reconstruction with legal language and reasoning chains) [

88,

121]. We quantify effort as

where

is base evaluation effort,

the number of prompts at tier

l, and

the average adaptation complexity. Empirical projects report 120–480 engineering hours depending on sector distance and pattern scope [

163,

165,

166,

167].

7.5.3. Governance Guardrail Configuration

Guardrail transferability varies with regulation and risk tolerance (

Table 8) [

150,

168].

We capture regulatory alignment via

where

and

encode guardrail stringency; higher

implies lower adaptation burden [

121,

125,

167,

171].

7.5.4. Human Oversight and Approval Workflow Adaptation

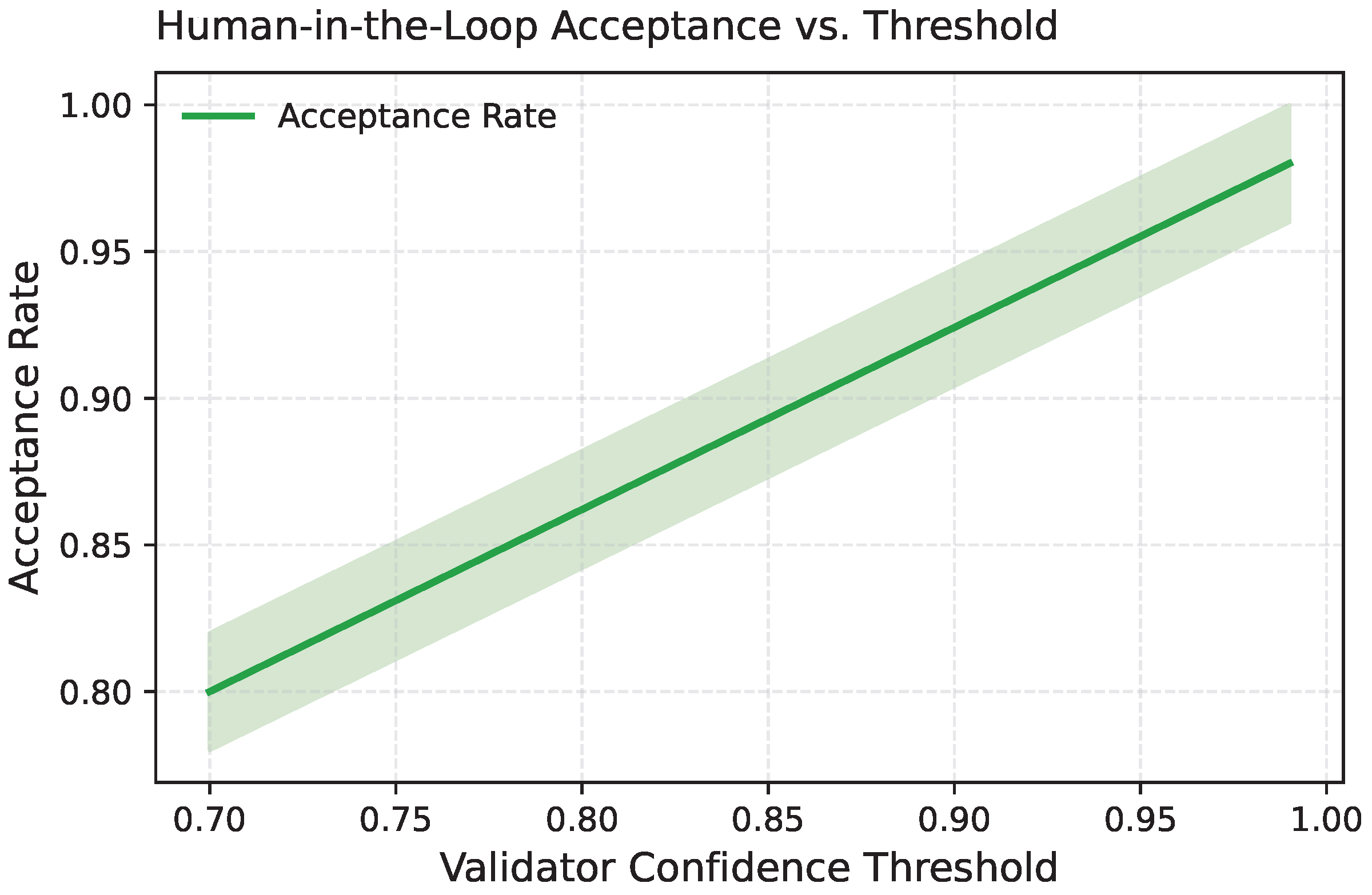

Human-in-the-loop transferability averages

and varies with decision criticality (

Table 9) [

107,

111].

Escalation thresholds follow a cost-risk optimum:

with conservative

(e.g., ≥0.95) in governance and lower thresholds in marketing (e.g., ≥0.75) [

107,

111,

157,

172].

7.5.5. Comprehensive Transferability Decision Matrix

Table 10 aggregates portability, prompt adaptation, guardrail reconfiguration, and approval workflow complexity into an overall PTF and duration estimate.

The overall score aggregates dimensions as

with weights reflecting sector priorities: governance often emphasizes guardrails and approvals (

,

); marketing emphasizes technical and prompt portability (

,

); accounting balances all with elevated guardrail emphasis (

) [

150,

167,

168,

173].

7.6. Strategic Transfer Implementation Roadmap

A phased roadmap improves transfer success [

150,

167,

168]:

Phase 1: Feasibility (2–4 weeks). Quantify PTF; elicit stakeholder requirements; map regulatory constraints [

171].

Phase 2: Infrastructure (4–8 weeks). Fine-tune base LLMs; adapt vector schemas; model graph relationships [

163,

167].

Phase 3: Prompts (3–6 weeks). Adapt prompts by tiers; curate evaluation sets; establish benchmarks [

165,

166].

Phase 4: Guardrails (4–8 weeks). Integrate legal frameworks; configure bias monitors; author explanation templates [

121,

168].

Phase 5: Oversight (3–5 weeks). Implement approvals; calibrate thresholds; test interfaces [

107,

111].

Phase 6: Pilot & Refine (6–10 weeks). Limited production; monitor KPIs; iterate on operational feedback [

167,

174].

Typical end-to-end transfer completes in 22–41 weeks depending on sector distance and readiness, with 65–

of expected benefits realized within 12 months of full deployment [

150,

163,

167].

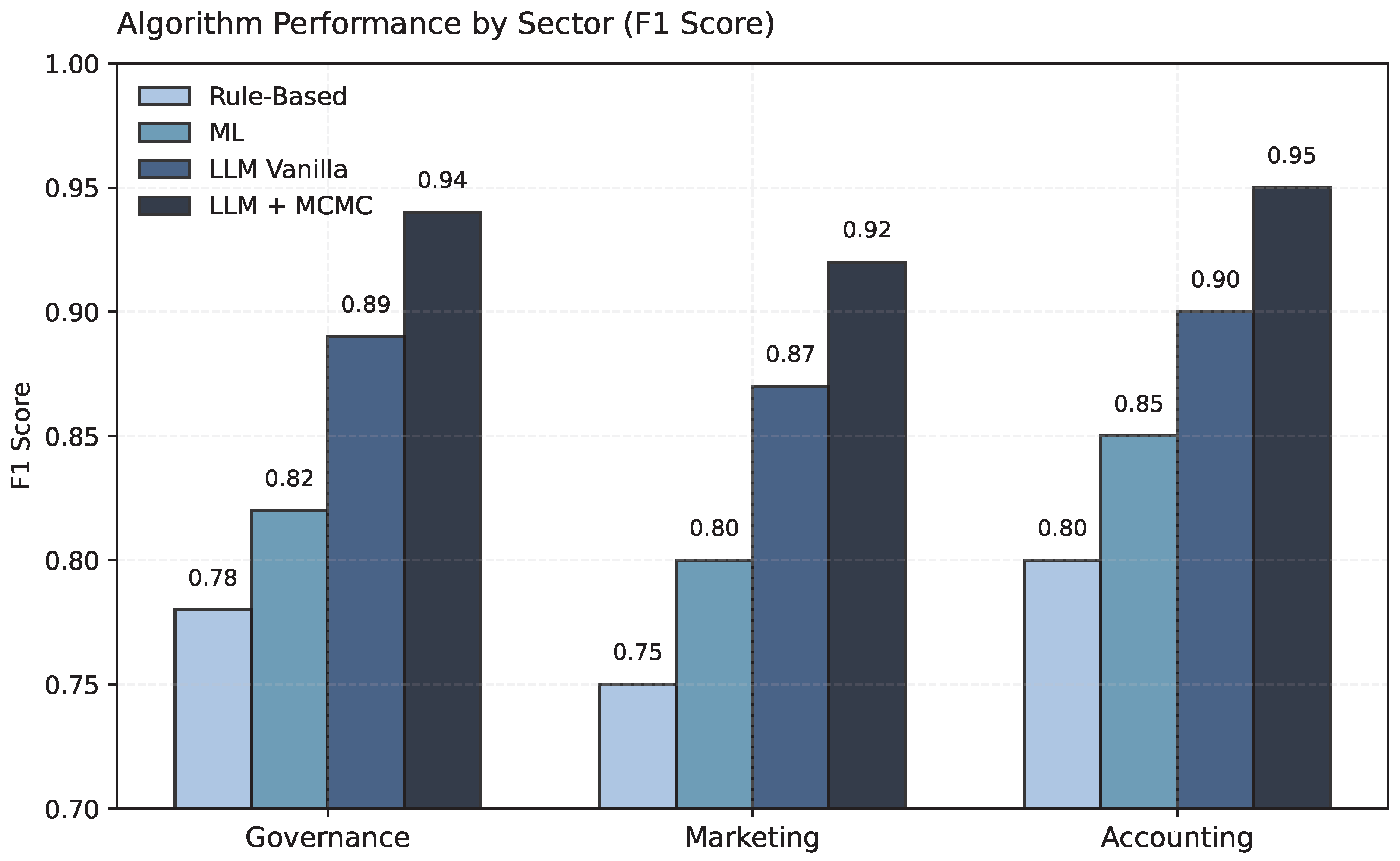

8. Experimental Results

8.1. Architecture Evaluation

In this part we assess the suggested distributed data management architecture with the LLM and which we have tested within three enterprise domains, which are digital governance, marketing, and accounting. The system uses Apache Spark and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to determine the uncertainty and verify the consistency of performance. In order to obtain a clear vision of the situation, we are interested in three main metrics, namely Semantic-Weighted Mapping Correctness (SWMC), Consent-Aware Entity Resolution Score (CERS), and Hierarchical Extraction Quality Metric (HEQM).

As shown in

Figure 10, the performance of ReMatch + algorithm is shown in terms of mapping in all three regions, and this study has indicated that the algorithm has consistently recorded high performance on mapping. Mean values of SWMC are not less than 0.90, which is an indication of well-developed semantic consistency, and high mapping accuracy. Interestingly, the small credible intervals found using MCMC sampling also provide an indication that the system gives stable and reproducible results, even when executed in a distributed manner. Within a single cluster configuration, repeated runs show stable aggregates; however, quantifying variance across heterogeneous nodes and clusters is left as future work, and the claim of distributed reproducibility should be interpreted in that scope.

Figure 11 gives a summary of the performance of the Consent-Aware Entity Resolution (C-ER) module. In this case, accuracy in terms of F1 is high in every sector, indicating the ability to recognize an entity accurately, and confidence calibration (AUCconf) is in line with the desired probabilities—a vital aspect of privacy and consent compliance. The business impact score (BIavg) is also high, implying that the module provides practical operational advantages. These probabilistic assessments are strong throughout because of the small uncertainty bands.

Figure 12 represents the Doc2Ledger-LLM system that has HEQM scores that are greater than 0.85 in most of the tested conditions. Performance only drops at a slow rate, even when layouts have been rotated or templates have been distorted considerably. This represents the power of multimodal feature fusion in combination with deterministic validation on our distributed architecture.

Collectively, these findings point to an impression that the architecture is both trustworthy and understandable: semantic accuracy in schema mapping (SWMC) is always high, entity resolution (CERS) is accurate and consent-sensitive, and multimodal extraction (HEQM) is strong. The resulting metrics, which are a combination of distributed computation and MCMC-based uncertainty calibration, are truly a measure of the actual uncertainty in the world, which provides transparency and accountability in the governance, marketing, and accounting environments.

The results in

Table 11 demonstrate that the LLM-enabled pipeline consistently outperforms classical approaches across key metrics, with particularly strong gains in semantic understanding (F1, F2), multimodal extraction robustness (F6), and policy-aware retrieval accuracy (F7). These improvements validate the integration of LLMs within the Spark-orchestrated, MCMC-calibrated framework for enterprise data management tasks.

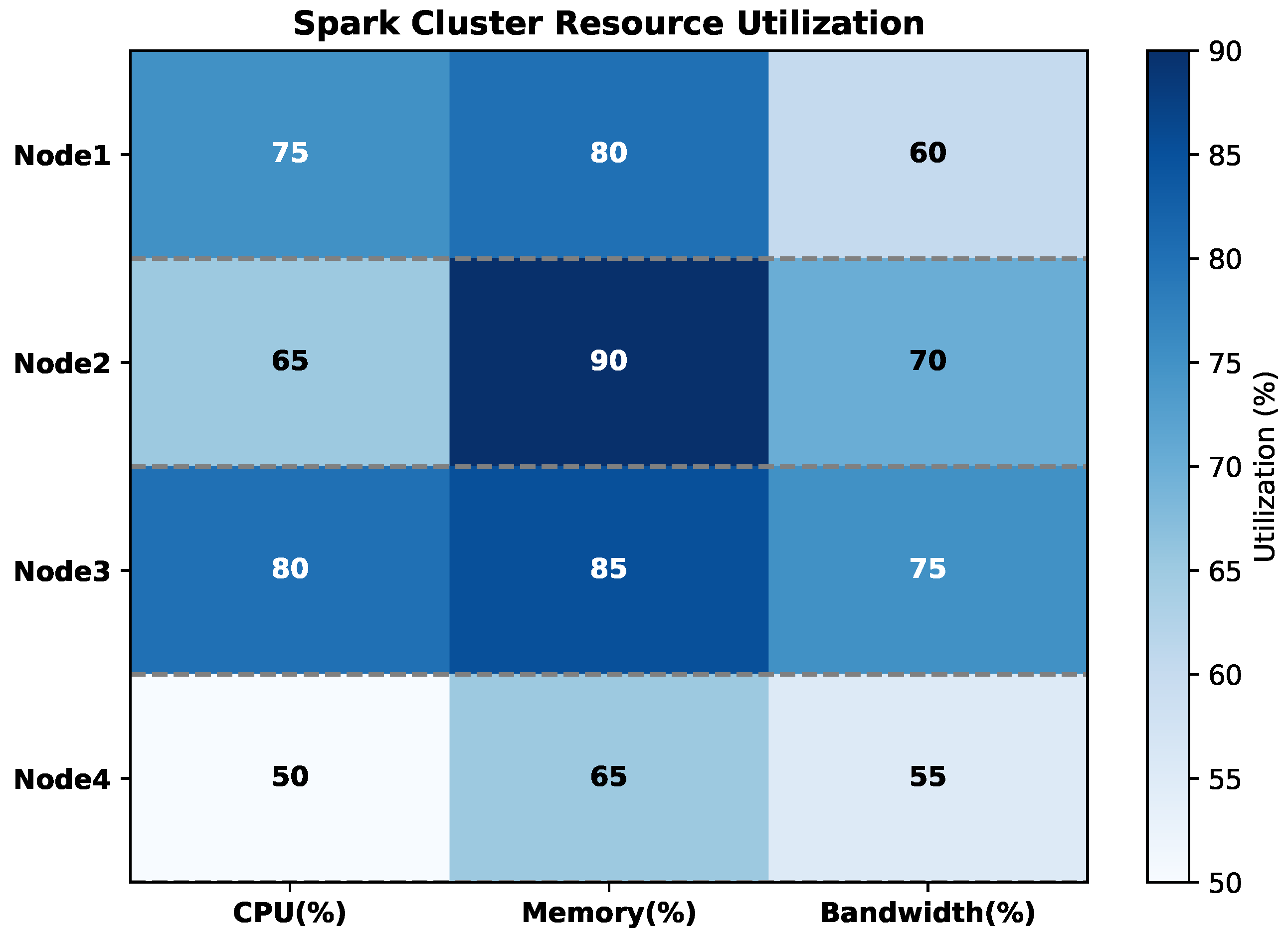

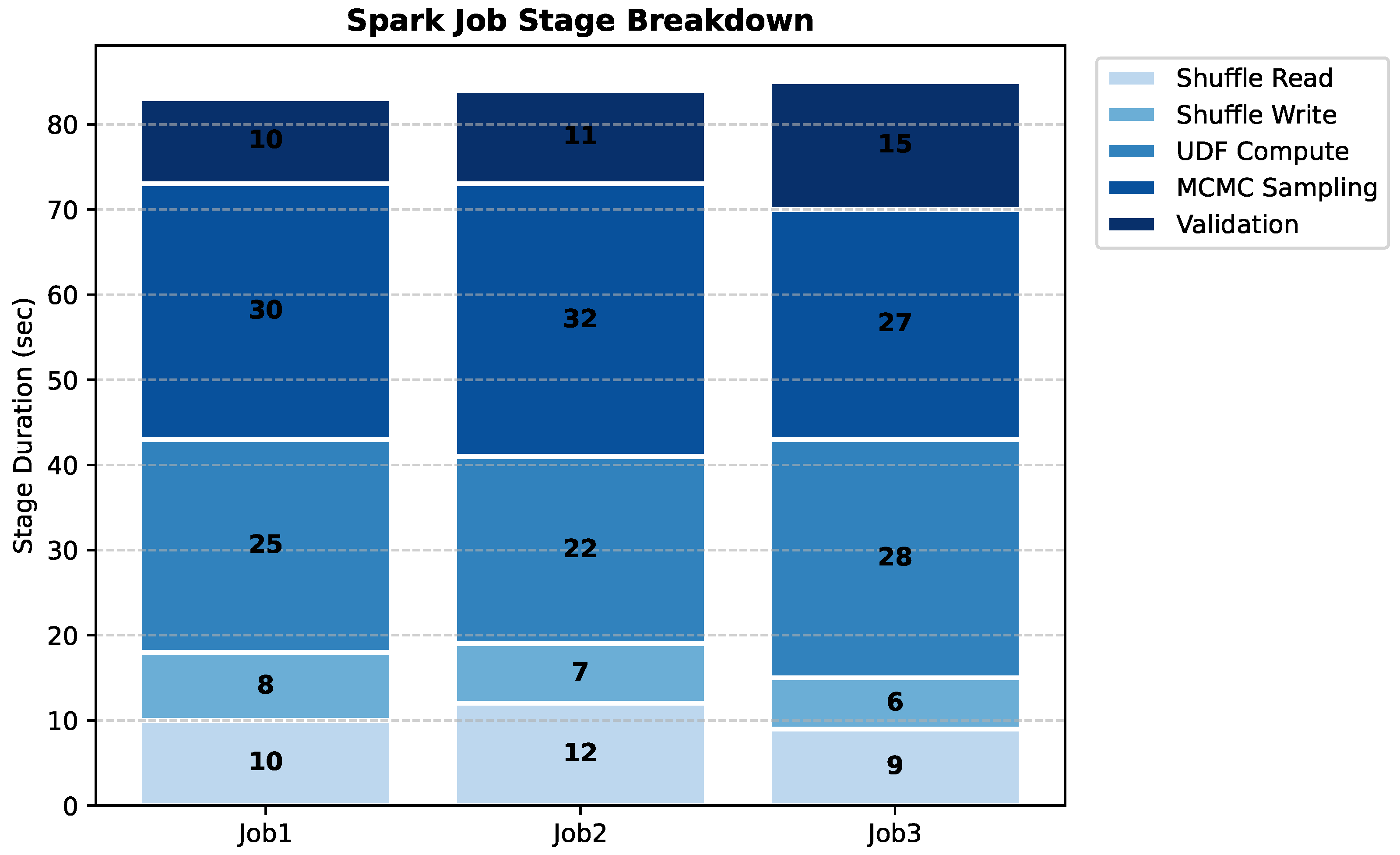

8.2. Distributed MCMC and Spark Diagnostics

We next examine how distributed MCMC samplers behave and converge when run across multiple Spark partitions. This analysis gives insight into how well the architecture handles large-scale uncertainty estimation while maintaining accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency.

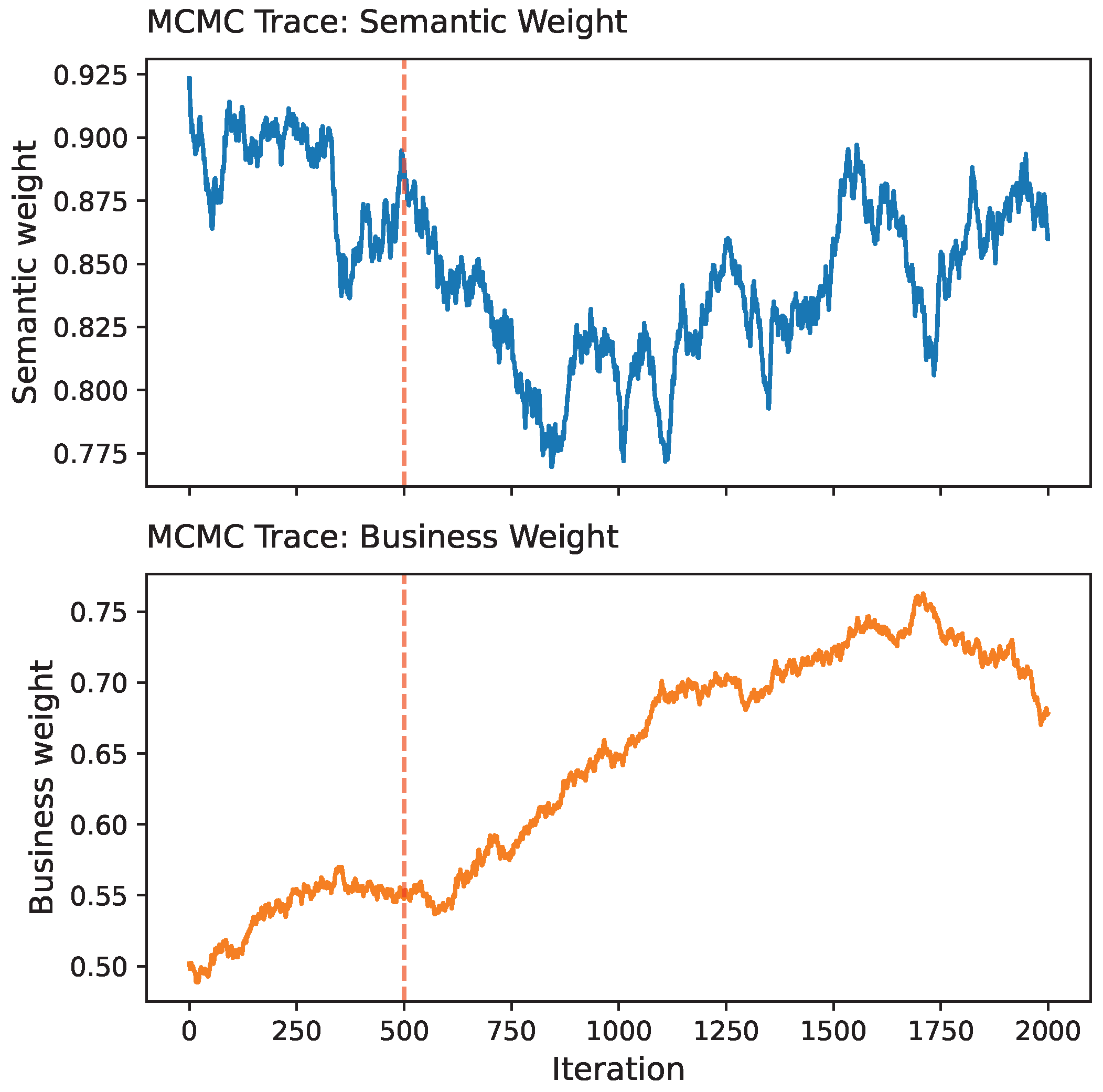

Figure 13 shows that after a brief burn-in period, the chains mix quickly, stabilizing to produce meaningful posterior samples. This indicates that initialization effects are short-lived, and convergence is consistent across the distributed Spark environment.

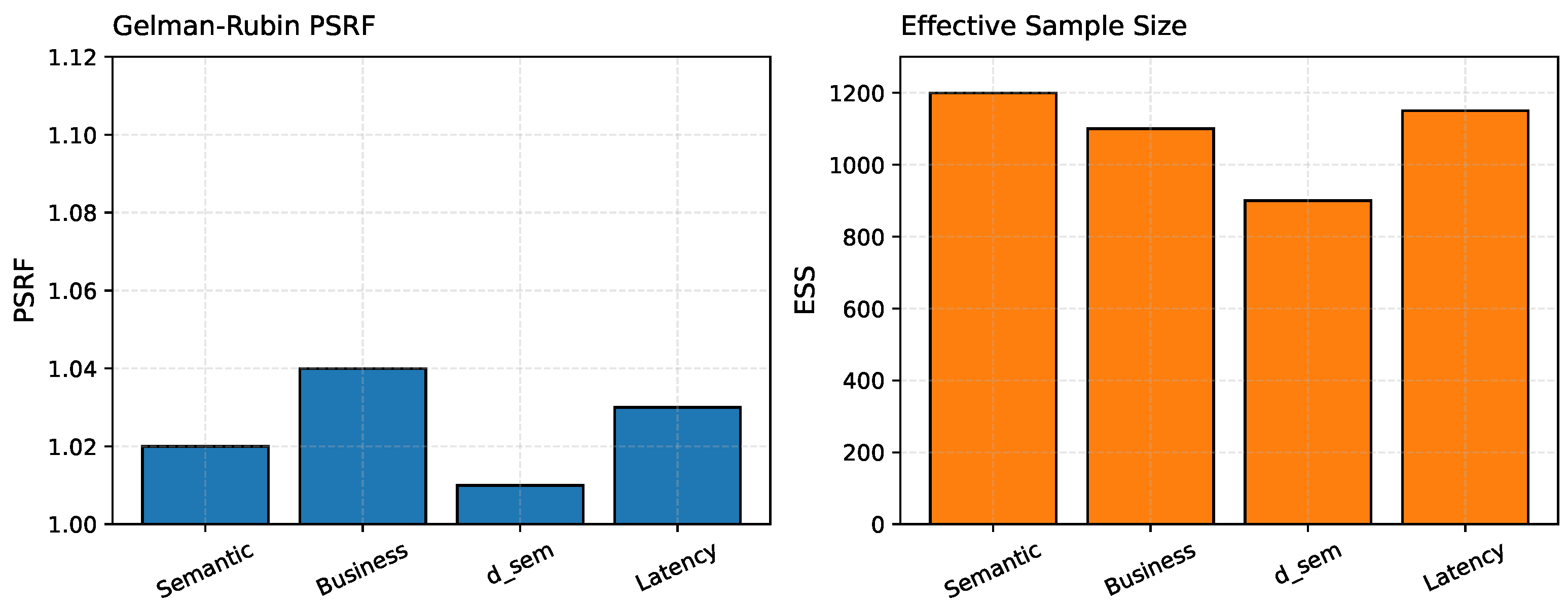

Figure 14 complements this, showing that PSRF values remain below 1.05 and ESS values exceed 900. Together, these metrics indicate that distributed MCMC through Spark maintains both statistical soundness and reliable uncertainty estimates.