Abstract

Pronoun resolution is essential for language comprehension, yet the neural mechanisms underlying this process remain poorly characterized. Here, we investigate the neural dynamics of impersonal pronoun processing using electroencephalography combined with machine learning approaches. We developed a novel experimental paradigm that contrasts impersonal pronoun resolution with direct nominal reference processing. Using electroencephalography (EEG) recordings and machine learning techniques, including local learning-based clustering feature selection (LLCFS), recursive feature elimination (RFE), and logistic regression (LR), we analyzed neural responses from twenty participants. Our approach revealed differential EEG feature patterns across frontal, temporal, and parietal electrodes within multiple frequency bands during pronoun resolution compared to nominal reference tasks, achieving classification accuracies of 78.52% for subject-dependent and 60.10% for cross-subject validation. Behavioral data revealed longer reaction times and lower accuracy for pronoun resolution compared to nominal reference tasks. Combined with differential EEG patterns, these findings demonstrate that pronoun resolution engages more complex mechanisms of referent selection and verification compared to nominal reference tasks. The results establish potential EEG-based indicators for language processing assessment, offering new directions for cross-linguistic investigations.

1. Introduction

Language comprehension fundamentally relies on our ability to establish referential relationships across discourse elements. Consider the sequence “The book is on the shelf. Bring it here.” Understanding such expressions requires linking pronouns to their antecedents, termed pronoun resolution, which forms a critical component of discourse comprehension [1,2,3]. This process enables the construction of coherent mental representations as meaning unfolds across sentences, fundamentally shaping subsequent language processing. Research into the neuro-cognitive mechanisms of pronoun resolution yields profound implications for language acquisition [4,5], comprehension [6,7], and rehabilitation of language disorders, especially in clinical populations such as Alzheimer patients [8,9], where proper pronoun processing is crucial for maintaining coherent discourse comprehension.

Behavioral and neuroimaging approaches have provided valuable insights into pronoun resolution mechanisms. Research has demonstrated that this process is governed by both prominence-lending features of referential candidates (notably subject status and left-edge positioning) and discourse-configured referential patterns, where information structure modulates referent accessibility [10,11]. Alongside behavioral observations, neuroimaging research has revealed the brain activation patterns associated with pronoun resolution. Specifically, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) investigation has identified a network involving the left middle temporal gyrus (LMTG) and frontal regions in antecedent retrieval and integration processes [12], with meta-analytic evidence further confirming the role of left temporal networks, particularly the posterior middle and superior temporal gyri, in lexical-semantic processing during pronoun resolution [13]. Despite these advances, behavioral and neuroimaging studies are inherently limited in their capacity to capture the rapid temporal dynamics of neural processes underlying pronoun resolution.

A recent study using single-neuron recording has revealed that hippocampal activity during pronoun processing exhibits distinct temporal phases, with antecedent activation occurring at 210 ms and pronoun integration at 600 ms [14]. While cellular-level observations provide valuable insights, the invasive nature of such recordings limits their widespread application in human subjects. Electroencephalography (EEG) technology offers a non-invasive alternative with millisecond-level temporal resolution, making it particularly suitable for capturing the dynamic neural changes associated with linguistic processes such as pronoun resolution [15,16]. More precisely, two primary processing stages have been identified in pronoun resolution, with antecedent activation occurring in the theta band (240–450 ms) and discourse integration in the gamma band (690–1000 ms) [17]. Evidence also suggests early parietal-frontal network engagement (~250 ms), indicating that pronoun resolution initiates during perceptual processing rather than later stages [18]. Moreover, functional network connectivity between the LMTG and frontal regions during pronoun processing reveals LMTG’s role in antecedent retrieval and frontal cortex’s role in integration, further highlighting the importance of frontal-temporal networks [19]. While these findings are promising, previous EEG studies have predominantly relied on conventional statistical methods or basic classification models, potentially overlooking the complex, high-dimensional nature of neural responses. Furthermore, the neuro-cognitive mechanisms of impersonal pronoun resolution remain largely unexplored.

The present study addresses these limitations through a novel experimental paradigm that compares sentences requiring pronoun resolution (P-label, e.g., “bring it here”) with those employing direct nominal reference (N-label, e.g., “bring the book here”). We aim to characterize the neural-cognitive mechanisms underlying impersonal pronoun resolution through comparison with nominal reference processing, while identifying optimal EEG feature extraction and classification methodologies for distinguishing these two linguistic processes. We hypothesize that pronoun resolution involves more complex mechanisms of referent selection and verification, characterized by enhanced neural complexity and increased demands on working memory and information integration processes compared to direct nominal reference processing.

To achieve this aim, we investigate the distinctive neural signatures of impersonal pronoun processing by combining behavioral data with multi-domain EEG features and utilizing advanced machine learning approaches such as local learning-based clustering feature selection (LLCFS) [20], recursive feature elimination (RFE) [21], and logistic regression (LR). Analysis of 64-channel EEG data from twenty participants revealed differential power spectral density (PSD) and differential entropy (DE) patterns across frontal, temporal, and parietal electrodes within multiple frequency bands during pronoun resolution compared to nominal reference tasks. Combined with behavioral analyses showing reduced accuracy, increased reaction time, and higher individual variability during pronoun processing, these findings collectively indicate enhanced neural complexity and more demanding working memory and information integration processes than nominal reference tasks. Furthermore, our machine learning approach successfully discriminated between impersonal pronoun and nominal reference processing, achieving classification accuracies of 78.52% for subject-dependent analysis and 60.10% for cross-subject validation, highlighting the effectiveness of our paradigm in capturing the neural dynamics of pronoun processing.

This study makes several contributions to understanding the neural mechanisms of impersonal pronoun resolution. First, we establish a novel experimental paradigm systematically contrasting pronoun resolution with nominal reference processing. Second, we develop an integrated machine learning framework combining LLCFS, RFE, and LR to identify discriminative EEG features across frequency bands and electrodes. Third, we provide empirical evidence linking behavioral patterns with differential neural signatures, revealing that pronoun resolution engages more complex referent selection and verification mechanisms compared to nominal reference tasks.

2. Related Works

Pronouns such as “it” and “she” are commonly used in daily language to refer to entities that are the focus of attention within a given context. Compared with direct nominal reference, pronoun resolution requires comprehenders to retrieve memory representations, as referential processing necessarily involves encoding a referential candidate in memory and subsequently reactivating and retrieving that representation when a pronoun or any other referring expression is encountered [22,23]. This section examines current knowledge regarding the cognitive–linguistic process and its neural substrates of pronoun resolution, emphasizing the potential of integrated EEG-based methodologies and machine learning approaches for elucidating these processes.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the cognitive–linguistic process of pronoun resolution involves information encoding of the antecedent and information retrieval with memory activation. A seminal work by Dell et al. shows that when people encounter anaphoric expressions such as pronouns [22], they need to retrieve antecedent information from memory in the form of propositions rather than isolated concepts, and they must establish connections between the propositions containing the anaphor and the antecedent. Building on this foundation, Karimi et al. further explored how different factors, including syntactic subject status, animacy, and semantic richness [23], influence the activation levels of referential candidates in memory during pronoun resolution, thereby affecting the difficulty of retrieving relevant representations from memory. A recent review examined the roles of working memory and semantic information integration in pronoun reference comprehension, pointing out that during reference processing, antecedent information needs to be retrieved from working memory, and the resolution stage involves the evaluation and verification of the correct antecedent within context [24].

Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies have revealed the cognitive–neural processes underlying pronoun resolution to some extent. Zhang et al. conducted an fMRI study indicating that compared to noun references, pronoun resolution involves antecedent retrieval processes that engage activation in brain regions associated with working memory and discourse integration, such as the temporal and frontal regions [12]. El Ouardi et al. demonstrated through fMRI that when attempting to locate the referent of a pronoun, potential antecedents need to be actively maintained in working memory and immediately retrieved upon encountering the pronoun [13]. In addition to the search and selection operations involved in pronoun referent retrieval, the reactivated antecedent must ultimately be integrated into the overall sentence or discourse structure for efficient comprehension to occur, with the entire process accompanied by activation in the frontotemporal network. Employing single-neuron recording in the hippocampus, Dijksterhuis et al. revealed that antecedent-selective cells were reactivated by corresponding pronouns, providing evidence that pronoun resolution engages memory retrieval mechanisms [14].

Recent advancements in shallow machine learning models, such as feature selection models and recursive feature elimination (RFE), have transformed EEG analysis in cognitive–neural mechanism research, providing profound insights into brain functionality and neural mechanisms underlying various cognitive processes. The pioneer work by Garrett et al. has proved that the combined use of feature selection models with shallow machine learning models is effective for analyzing spontaneous EEG classification for mental tasks [25]. In a recent study, Abdumalikov et al. employed three feature selection methods combined with four classifiers to analyze EEG signals for human emotion recognition [26], improving classification accuracy on the DEAP dataset by 1.59 to 2.84 percent and providing an effective approach for affective computing. Besides feature selection models, the combination of RFE with shallow classifiers, as a general-purpose feature selection technique, is also applicable to feature classification studies based on electrophysiological signals. The theoretical foundation of RFE was systematically established by Guyon et al. (2002), who introduced the support vector machine-based RFE method for gene selection and cancer classification, demonstrating its capability to automatically eliminate feature redundancy and produce compact feature subsets with superior classification performance [21]. Since then, RFE has been extensively applied to EEG-based classification tasks. Gysels and Celka employed RFE combined with linear discriminant analysis for channel selection in P300-based brain–computer interfaces, validating its effectiveness in identifying critical electrode positions and time windows from high-dimensional EEG data [27]. Yin et al. extended RFE to cross-subject emotion recognition, successfully reducing a 440-dimensional feature space on the DEAP database [28]. More recently, Hamed et al. demonstrated RFE’s robustness in EEG-based wheelchair navigation control, achieving 69% accuracy by selecting 13 features from 141 dimensions [29].

These investigations collectively underscore the promise of EEG-based methodologies for decoding neural mechanisms underlying pronoun resolution and associated cognitive operations. Nevertheless, research examining impersonal pronoun resolution mechanisms through appropriate machine learning frameworks remains scarce, particularly studies employing integrated models combining feature selection, RFE, and classification algorithms. Advancing such research offers substantial potential for deepening understanding of language comprehension processes and their neural foundations.

3. Materials and Methods

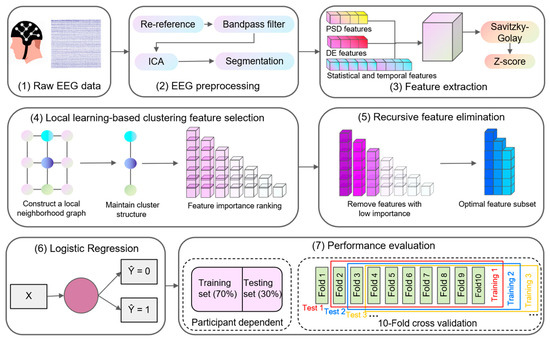

Figure 1 illustrates the overall framework of this study, which comprises seven sequential stages. The initial stage involves EEG data acquisition from participants. The subsequent stage encompasses preprocessing of the raw EEG signals. The third stage focuses on extracting relevant features from the preprocessed data. The fourth stage applies the LLCFS algorithm to rank features according to their classification contribution. The fifth stage employs the RFE approach to refine the feature set to the optimal dimensionality. The sixth stage feeds the selected features into the LR classifier for model training. The final stage conducts performance evaluation using both subject-dependent and ten-fold cross-validation methodologies to assess classification accuracy.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed framework for EEG signal analysis.

3.1. Participants

Twenty male students (age range: 18–25 years; all right-handed) from the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology (USST) participated in this study. All participants were native Mandarin Chinese speakers with no history of neurological disorders, genetic conditions, or chronic substance use. Participants had no prior exposure to pronoun resolution experiments to control for potential learning effects. The study protocol was approved by the USST Ethics Committee (protocol number: 00960.00.39586) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before the experiment and received monetary compensation for their participation.

3.2. Experimental Design

The experimental paradigm comprised 144 trials (36 per condition), counterbalanced to control for order effects. All stimuli were presented in Mandarin Chinese. Each trial consisted of three sequential components: a context sentence describing spatial relationships, a command sentence requiring referent identification, and a question prompt (“What to bring?”) eliciting participant response. As detailed in Table 1, the context sentences were categorized into two types: Type I expressed direct spatial relationships (x is on/in y), exemplified by “Waitao zai yijia shang (The coat is on the clothes rack)”; Type II indicated possession or existence (there is an x on/in y), such as “Yijia shang you waitao (There is a coat on the clothes rack)”. Notably, these two types differ in word order in Mandarin Chinese, with Type I following an x-y sequence (target-location) while Type II following a y-x sequence (location-target). After each context sentence, participants encountered either a pronoun command (“Ba ta nalai”, meaning “Bring it here”) or a noun command (“Ba waitao nalai”, meaning “Bring the coat here”). Responses were recorded via keyboard input, with ‘Z’ and ‘M’ keys corresponding to left and right nouns, respectively.

Table 1.

Experimental stimuli exemplifying context-command pairs across conditions. Examples are presented in Chinese Pinyin (italicized), morphosyntactic glosses following the Leipzig Glossing Rules, and English translations. Conditions vary in pronoun type (pronoun vs. noun command) and context sentence structure (Type I vs. Type II). Abbreviations: PREP, preposition; IMP, imperative; SG, singular; ACC, accusative.

3.3. Environment and Procedures

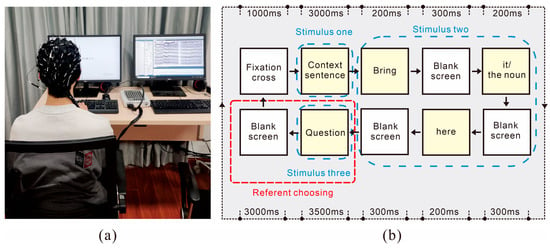

The experiment was conducted in a soundproof, electromagnetically shielded chamber (Figure 2a). Participants were seated in an adjustable chair positioned approximately sixty centimeters from the display monitor. The experimental environment was designed to facilitate independent task execution by participants while permitting discrete observation by the experimenter. Linguistic stimuli were presented on the screen of one computer via E-PRIME 3.0 software, which simultaneously recorded participants’ behavioral responses, while another computer recorded EEG data through CURRY 8.0 software during task performance. EEG data were collected using a 64-channel electrode cap configured according to the international 10–20 system. Prior to experimental initiation, participants underwent electrode cap fitting procedures to ensure optimal signal quality and received comprehensive instructions regarding experimental protocols and safety procedures to ensure complete understanding of the task requirements.

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental environment. (b) Experimental procedure for the pronoun resolution task.

The experimental paradigm (Figure 2b) comprised pronoun resolution tasks, with each trial consisting of three sequential stimuli: (1) a context sentence, (2) a command sentence containing either a pronoun or a noun, and (3) a question prompt. Throughout stimulus presentation, continuous EEG recordings were obtained. Participants indicated their responses using the ‘Z’ or ‘M’ keys on the keyboard. A 3000 ms interval was maintained between successive trials. Prior to the main experiment, participants completed a 10-trial practice session for task familiarization. To mitigate fatigue effects, one-minute rest periods were incorporated between experimental sessions. The formal experiment lasted approximately 30 min.

3.4. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

EEG data were recorded using a Neuroscan SynAmps2 64-channel amplifier (Compumedics Neuroscan, Charlotte, NC, USA) with a Quik-Cap electrode cap. Electrodes were arranged according to the extended 10/20 international system, utilizing Ag/AgCl-sintered materials with AFz serving as the ground electrode, with impedances maintained below 20 kΩ. Signal acquisition was performed through Curry 8 software with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. The experimental setup utilized a Windows 10 system (Intel i7 CPU, 3.60 GHz, 4 GB RAM) for both EEG recording and behavioral data collection.

Data preprocessing was conducted using Python 3.11 protocols: (1) selection of EEG channels, excluding HEOG, VEOG, and trigger channels; (2) bad channel detection and interpolation, followed by re-referencing; (3) application of a 4–45 Hz finite impulse response (FIR) filter and a 50 Hz notch filter for frequency band isolation; and (4) independent component analysis (ICA) for artifact removal, particularly addressing ocular and muscular contamination. The application of ICA to 4–45 Hz filtered data was specifically designed to enhance artifact identification by excluding frequency ranges dominated by eye movement artifacts (below 4 Hz) and muscle artifacts (above 45 Hz) commonly encountered in language processing tasks. The preprocessed data for each participant were divided into 144 segments of 12 s (approximately 28 min of viable data), which provided sufficient temporal resolution for subsequent analyses.

3.5. EEG Feature Extraction

We employed time-frequency transformed features extracted from preprocessed EEG signals acquired across 144 experimental trials for each participant. The classifier input consisted of features derived from entire experimental trials lasting 12 s, with each trial segmented into twelve consecutive 1-s epochs for feature extraction and analysis. Four categories of features were extracted (Table 2): statistical, temporal, PSD, and DE. Statistical features comprised mean, variance, kurtosis, and skewness, yielding 3072 features across 64 channels per epoch. Temporal features included peak-to-peak amplitude, zero-crossing rate, line length, and the minimum and maximum of the first derivative, yielding 3840 features per epoch. PSD and DE features were extracted from four frequency bands (theta: 4–8 Hz, alpha: 8–15 Hz, beta: 15–30 Hz, gamma: 30–45 Hz), each yielding 3072 features per epoch. The resulting input dataset D consisted of m = 34,560 samples (20 participants × 144 trials × 12 epochs) and n = 1088 features (576 temporal–statistical + 256 PSD + 256 DE). By incorporating multi-domain EEG features, our approach provides rich and complementary neural indicators to characterize the neural-cognitive mechanisms underlying impersonal pronoun resolution compared to nominal reference processing. To enhance interpretability, we ranked features by their LLCFS-derived classification contribution weights and analyzed the most discriminative features through topographic visualizations and neurophysiological interpretations based on existing pronoun resolution literature.

Table 2.

Summary of extracted EEG features and their notations.

3.6. Target Labels of the EEG Segments

EEG segments were labeled based on the linguistic reference type in the directive sentences. Segments were categorized as ‘P’ for anaphoric pronoun resolution tasks and ‘N’ for explicit nominal reference tasks. For instance, in the sequence “Waitao zai yijia shang. Ba ta nalai (The coat is on the clothes rack. Bring it here)”, where the pronoun “ta (it)” requires anaphoric resolution, the segment was labeled as ‘P’. Conversely, in “Qunzi zai yijia shang. Ba qunzi nalai (The dress is on the clothes rack. Bring the dress here)”, where the noun “qunzi (dress)” provides explicit reference, the segment was labeled as ‘N’.

4. Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

Feature selection and dimensionality reduction techniques play a crucial role in improving classification performance by removing irrelevant or redundant variables. Through the identification of a compact subset of informative features, model performance is improved via enhanced generalization, reduced computational overhead, and increased interpretability. This section examines diverse feature selection methodologies and one dimensionality reduction approach well-suited for multi-domain EEG feature analysis and neural pattern classification in language processing tasks. We investigate Correlation-based Feature Selection (CFS), ReliefF, Local Learning-based Clustering Feature Selection (LLCFS), Feature Selection via Concave Minimization (FSVCM), Unsupervised Discriminative Feature Selection (UDFS), and Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). These methods are selected for their demonstrated robustness in handling high-dimensional data with limited samples and noisy signals, characteristics inherent to our EEG dataset. Additionally, as shallow machine learning models, they provide transparent feature processing mechanisms that facilitate the interpretation of neural mechanisms underlying pronoun resolution. For each method, we present detailed pseudocode with dataset-specific parameters to clarify their implementation in our experimental context.

4.1. Correlation-Based Feature Selection

The correlation-based feature selection (CFS) algorithm determines an optimal subset of features by jointly assessing each feature’s association with the class label and the inter-feature redundancy [30]. By maximizing the correlation between features and the target while minimizing redundancy among selected features, the method effectively enhances classification accuracy and model interpretability.

Algorithm 1 illustrates the pseudocode of CFS. Given a dataset with samples and candidate features, we extracted time-statistical features, PSD features, and DE features (, comprising time-statistical, frequency, and DE features). The algorithm begins with an empty subset . For each feature , it computes the correlation with the target variable, denoted as , and the pairwise correlations to quantify redundancy. The mean correlations between a feature and the current subset is expressed as . The overall CFS merit score for feature is calculated by,

where denotes the number of features currently in the subset. This metric provides a trade-off between the predictive strength of a feature and its redundancy with the features already selected. The feature achieving the maximum value is iteratively incorporated into until a stopping criterion is met, ensuring an optimal equilibrium between relevance and redundancy.

| Algorithm 1. Correlation-based feature selection (CFS) | |

| Input: | // features |

| // Candidate feature set | |

| // Target variable (class labels) | |

| Output: | // Optimal subset of selected features |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | end for |

| 5 | repeat |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Compute the mean subset correlation: |

| 9 | |

| 10 | Evaluate the CFS merit score: |

| 11 | |

| 12 | end for |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | until convergence or stopping criterion is met |

| 16 | |

4.2. ReliefF

ReliefF, an improved variant of the original Relief approach, is particularly effective for high-dimensional data involving multiple classes and potential missing values [31]. In this study, we apply ReliefF to our multi-domain EEG feature set to capture cross-channel dependencies and subtle variations across PSD, DE, and temporal–statistical features. Since EEG trials naturally cluster in multidimensional space, the nearest-hit and nearest-miss mechanism of ReliefF is suitable for identifying features with consistent within-class behavior and pronounced between-class separability.

Algorithm 2 summarizes the ReliefF procedure as applied to our dataset configuration. Given our dataset with feature matrix and corresponding class labels , the algorithm iteratively examines each sample , and determines nearest neighbors both within the same class (nearest hits) and from other classes (nearest misses). For each feature , its relevance weight is updated according to the difference between the instance and its neighbors as follows.

where denotes the value of feature in instance and represent the values of feature in the -th, nearest hit and miss, respectively, and measures the feature-wise distance between instances.

After all iterations, each feature weight is normalized to the maximum value.

Features are then ranked based on their normalized weights , where higher values indicate stronger discriminative capability in distinguishing class labels while minimizing irrelevant or redundant information.

| Algorithm 2. ReliefF | |

| Input: | // features |

| // Feature matrix | |

| // Target variable (class labels) | |

| // Number of nearest neighbors | |

| Output: | // Normalized feature weights |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | // Same class |

| 4 | // Different class |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Compute the feature-wise difference |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Update feature weight according to |

| 9 | |

| 10 | end for |

| 11 | end for |

| 12 | Normalize feature weights: |

| 13 | , |

| 14 | in descending order |

4.3. Local Learning-Based Clustering Feature Selection

The local learning-based clustering feature selection (LLCFS) algorithm is an unsupervised feature selection method designed to preserve the intrinsic manifold structure of data by simultaneously learning feature importance and local discriminative information. We apply LLCFS to our EEG dataset given that EEG patterns often lie on nonlinear manifolds and exhibit strong spatial structure across channels, making LLCFS particularly suitable for uncovering features that maintain neighborhood consistency across trials in an unsupervised manner.

Algorithm 3 presents the LLCFS procedure as applied to our dataset configuration, emphasizing the construction of local graphs from our 1088-dimensional EEG feature space (comprising 9 × 64 temporal–statistical, 4 × 64 PSD, and 4 × 64 DE features) and the optimization of feature weights based on neighborhood preservation.

Formally, LLCFS seeks an optimal feature weight vector,

that minimizes the following objective function,

subject to

where and denote the feature vectors of samples and ; denotes the learned local similarity between two samples, and is a regularization parameter that controls the smoothness of the weight distribution.

During optimization, the algorithm alternately updates the similarity matrix (capturing local manifold structure) and the feature weight vector (highlighting dimensions that best preserve the local geometry). After convergence, features are ranked according to the magnitude of their normalized weights, and the top-ranked subset is selected for subsequent analysis.

| Algorithm 3. Local learning-based clustering feature selection (LLCFS) | |

| Input: | // features |

| // Feature matrix | |

| // Number of nearest neighbors | |

| // Regularization parameter | |

| // Maximum number of iterations | |

| Output: | // Learned feature weight vector |

| // Local similarity matrix | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | repeat |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | : |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | : |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | in descending order |

| 17 | return top-ranked |

4.4. Feature Selection via Concave Minimization

The feature selection via concave minimization (FSVCM) method is a supervised feature selection approach that identifies a sparse subset of features with strong discriminative power [32]. It relies on zero-norm () minimization approximated via a concave function to induce sparsity in the linear model weights, enabling both interpretability and robust classification performance.

Algorithm 4 presents the FSVCM procedure as applied to our dataset configuration, illustrating how the weight vector W is learned using our labeled EEG data. Given a labeled dataset with class labels , the FSVCM method seeks a linear classifier subject to a sparsity constraint on . The original -norm problem is NP-hard, so it is approximated using a concave surrogate function , allowing iterative reweighted optimization:

where is the feature matrix; are the class labels; is the feature weight vector; c is the bias term; is a concave function approximating the -norm; balances classification loss and sparsity.

| Algorithm 4. Feature selection via concave minimization (FSVCM) | |

| Input: | // Feature matrix |

| // Number of nearest neighbors | |

| // Regularization parameter | |

| // Feature importance estimate | |

| // Iteration counter | |

| // Smoothing parameter | |

| // Convergence threshold | |

| Output: | // Learned feature weight vector |

| // Ranked feature indices rank | |

| 1 | ← 0, ε ← 10−5 |

| 2 | repeat until convergence or max iterations |

| 3 | |

| 4 | // Compute penalty weights |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | end for |

| 9 | // Solve weighted convex optimization |

| 10 | standard quadratic programming (QP) |

| 11 | Update |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Check convergence |

| 14 | then break |

| 15 | |

| 16 | Select top-k features as final subset |

| 17 | |

4.5. Unsupervised Discriminative Feature Selection

Unsupervised discriminative feature selection (UDFS) is a method designed to identify discriminative and non-redundant features without using class labels [33]. We apply UDFS to our EEG dataset to detect feature domains (i.e., statistical, temporal, PSD and complexity) that exhibit inherent discriminative structure in an unsupervised manner.

Algorithm 5 presents the UDFS procedure as applied to our dataset configuration, illustrating the construction of the pseudo-label matrix and transformation matrix from our EEG feature space. Given our data matrix with samples and features, it seeks to learn a transformation matrix and pseudo-label indicator matrix .

The objective is formulated as:

where enforces row sparsity, ensuring that only a subset of features remains active; control sparsity and discriminative strength, respectively; acts as a latent label assignment, optimized jointly with .

To mimic the CFS-style iterative selection mechanism, a UDFS scoring function can be expressed as,

where represents the discriminative strength of feature and the denominator penalizes inter-feature dependence.

Features with the highest score are iteratively added to until convergence, producing a compact and discriminative subset.

| Algorithm 5. Unsupervised discriminative feature selection (UDFS) | |

| Input: | |

| Output: | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | repeat |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | until convergence |

| 6 | |

| 7 | -k |

| 8 | |

In our experimental evaluation across multiple feature selection methods, LLCFS consistently achieved superior performance compared to the alternatives. Consequently, groups adopt LLCFS as the primary feature selection strategy in this study, leveraging its ability to preserve local manifold structure while effectively ranking features according to their intrinsic relevance.

4.6. Dimensionality Reduction Method

Dimensionality reduction constitutes a fundamental step in improving classification performance. Among various approaches, recursive feature elimination (RFE) has been widely employed due to its systematic strategy of iteratively removing less informative features [21,27,28,29]. By leveraging the predictive capability of a base estimator, RFE ranks features according to their contribution to the model and eliminates those with minimal influence, thereby refining the feature subset in a principled manner.

In this study, we implemented RFE in combination with several classifiers, including support vector machine (SVM), adaptive boosting (ADB), naive Bayes (NB), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and LR. Algorithm 6 presents the RFE procedure as applied to our dataset configuration. Given our dataset D with m = 34,560 samples and n = 1088 features (comprising 9 × 64 temporal–statistical, 4 × 64 PSD, and 4 × 64 DE features), the algorithm iteratively removes the least important features based on the base estimator’s feature ranking. The combination of RFE and LR was selected as a representative example to demonstrate the operational mechanism of the feature selection and classification pipeline.

Specifically, LR provides feature importance through the absolute weight derived from the linear decision function:

where represents the predicted probability, denotes features, represents feature weights, and is the bias term. Feature importance is quantified as:

In practice, the algorithm iteratively eliminates 5% of the least important features until 50% of the initial set is retained, yielding the refined subset, defined by:

where represents the retention threshold. This systematic approach ensures the preservation of the most informative features while minimizing redundancy and noise in the final feature subset, ultimately enhancing both the robustness and interpretability of the classification model.

| Algorithm 6. Recursive feature elimination (RFE) | |

| Input: | // Feature matrix |

| //Ratio of features to remove in each iteration | |

| //Ratio of features to retain at the end | |

| //Estimator used for feature importance | |

| Output: | |

| 1 | , , |

| 2 | : |

| 3 | ) |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | end for |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | ) features in sorted_features |

| 10 | |

| 11 | end while |

| 12 | |

5. Results

5.1. Behavioral Data Analysis

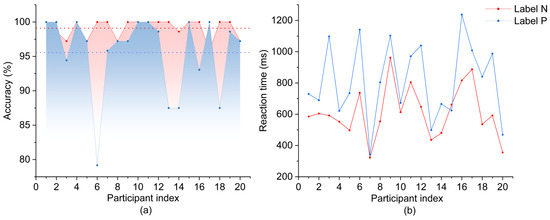

Behavioral data were analyzed for both nominal reference (N) and pronoun resolution (P) labels, with accuracy rates and reaction time collected from 20 participants (Figure 3). Analysis revealed higher accuracy rates for label N (M = 99.10%, SD = 1.37%) compared to label P (M = 95.56%, SD = 5.80%), with a significant difference between labels (t(19) = 2.57, p = 0.019). RT also exhibited a significant difference between labels (t(19) = 5.85, p < 0.001), with faster responses for label N (M = 611.827 ms, SD = 165.833 ms) relative to label P (M = 813.972 ms, SD = 249.135 ms).

Figure 3.

Behavioral performance metrics across participants during pronoun resolution tasks. (a) Response accuracies across participants. (b) Reaction times for nominal reference (N) and pronoun resolution (P) conditions.

Task validity was confirmed by the high accuracy rates (>95%) across both labels, with 19 of 20 participants maintaining accuracy levels above 85%. The significant increase in RT (202.145 ms difference, p < 0.001) and decrease in accuracy (3.54% difference, p = 0.019) for label P suggest higher cognitive processing demands during pronoun resolution. Furthermore, while performance remained relatively consistent across participants for label N, greater individual variability was observed for label P in both accuracy (SD = 5.80% vs. 1.37%) and RT (SD = 249.14 ms vs. 165.83 ms), indicating diverse cognitive processing strategies during pronoun resolution

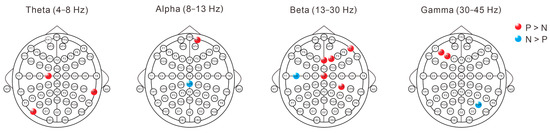

5.2. Statistical Testing of PSD

Statistical analysis using two-sample t-tests after removing aperiodic components using Fitting oscillations & one-over-F (FOOOF) revealed distinct patterns of PSD differences between labels P and N across frequency bands (Figure 4). In the theta band (4–8 Hz), significant differences were observed in multiple channels, with higher PSD values for pronoun processing in three channels (C1, TP8, PO7). The alpha band demonstrated a more focused pattern, with CPZ showing significantly lower PSD values during pronoun processing, while FP2 exhibited higher values for pronouns. Both beta (13–30 Hz) and gamma (30–45 Hz) bands demonstrated predominantly enhanced PSD values during pronoun processing. In the beta band, five channels (FZ, F2, F8, CZ, CP4) showed significantly higher PSD values, with C5 showing decreased activity. In the gamma band, F3 and F5 exhibited enhanced PSD values, while PO6 alone demonstrated lower values.

Figure 4.

Topographical distribution of pronoun-noun referential processing differences across frequency bands after removing aperiodic components using Fitting oscillations & one-over-F (FOOOF). Frequency bands analyzed include theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–45 Hz). Red and blue dots indicate electrodes where periodic component power was significantly higher for pronouns (P > N) and nouns (N > P), respectively (p < 0.05, two-sample t-test).

5.3. Optimization of Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

To identify the most indicative EEG features of neuro-cognitive mechanisms in pronoun resolution, we implemented feature selection and dimensionality reduction methods. These methods enhance classification performance in distinguishing between labels P and N by eliminating irrelevant or redundant features and mitigating the curse of dimensionality.

The analysis involved two stages of feature optimization. First, we integrated EEG features with various combinations of feature selection models and machine learning classifiers, employing a 70:30 training–testing split ratio. The optimal feature subset size was determined by incrementally selecting the top 5% to 100% of features, based on their weight rankings, in 5% intervals. The LLCFS model, combined with the ADB classifier, emerged as the optimal configuration. This combination achieved an average classification accuracy of 56.92% when selecting the top 25% of feature sets (Table 3). Subsequently, we implemented RFE in conjunction with LLCFS to further optimize feature selection. Using LR as the base estimator, we iteratively reduced the feature set to 50% of the original features. Comparative analysis of various machine learning classifiers revealed that the LR classifier demonstrated superior performance, achieving both accuracy and macro-F1 scores of 65.7% (Table 4). Based on these two-stage optimization procedures, we established the LLCFS-RFE-LR combination as our final classification framework, which demonstrated optimal performance in distinguishing between impersonal pronoun and nominal reference processing.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of feature selection methods paired with different classifiers, showing classification accuracies, optimal feature proportions, and macro-F1 scores for pronoun/nominal reference resolution. Bold text denotes the best-performing combination of LLCFS with ADB classifier. FSVCM: feature selection via concave minimization; UDFS: unsupervised discriminative feature selection; LLCFS: local learning-based clustering feature selection; CFS: correlation-based feature selection; SVM: support vector machine; ADB: adaptive boosting; NB: naive Bayes; LR: logistic regression; LDA: linear discriminant analysis.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different classifier combinations using LLCFS + RFE approaches. Bold text denotes the best performing combination of LLCFS, RFE, with LR classifier. LLCFS: local learning-based clustering feature selection; RFE: recursive feature elimination; SVM: support vector machine; ADB: adaptive boosting; NB: naive Bayes; LR: logistic regression; LDA: linear discriminant analysis.

5.4. Channel Contribution Analysis

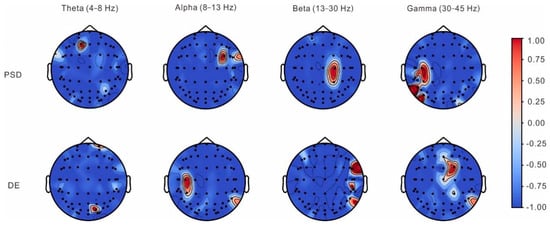

LLCFS was employed to evaluate the discriminative contribution of EEG channels in classifying labels P and N. As shown in Figure 5, analysis of channel contribution across frequency bands revealed distinct spatial patterns for both PSD and DE features. For PSD features, the most discriminative channels were identified from frontal electrode (F1) for theta band, frontotemporal electrodes (FC4, FT8) for alpha band, central–parietal electrodes (C2, CP2) for beta band, and central–parietal–occipital electrodes (C3, P7, CP3, PO7, TP7) for gamma band. Similarly, DE features exhibited distinctive spatial patterns, with significant discriminative channels from parietooccipital and frontal electrodes (PO4, FP2) for theta band, central–parietal electrodes (C3, CP3, P8) for alpha band, frontotemporal and parietal electrodes (FT8, TP8, P8) for beta band, and frontocentroparietal electrodes (FC2, CZ, CP2, FZ, P8) for gamma band. The spatial distribution of these discriminative patterns suggests frequency-specific neural mechanisms underlying the distinction between pronoun and nominal reference processing.

Figure 5.

Topographical distribution of feature importance weights derived from LLCFS analysis for discriminating between pronoun (P) and nominal (N) reference processing. Maps show normalized channel weights (−1.0 to 1.0) for power spectral density (PSD, top row) and differential entropy (DE, bottom row) across theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–45 Hz) frequency bands. Red colors indicate higher discriminative importance, while blue colors indicate lower importance.

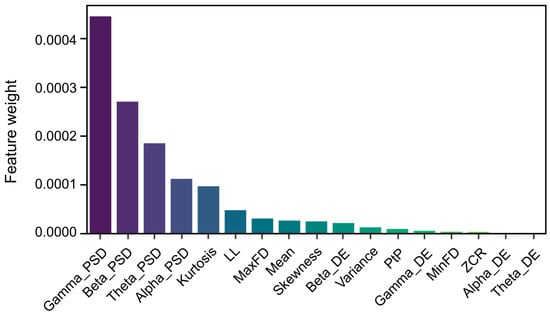

LLCFS analysis also identified critical EEG features in temporal and statistical domains that significantly contributed to the classification of labels P and N. The most discriminative features, ranked by their contribution weights, comprised kurtosis, line length, the maximum of the first derivative, mean, skewness, variance, peak-to-peak amplitude, the minimum of the first derivative, and zero crossings (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Top 17 feature contribution weights in classification derived from LLCFS across all domains. Note: ZCR = zero-crossing rate; PtP = peak-to-peak amplitude; MinFD = the minimum of the first derivative; MaxFD = the maximum of the first derivative; LL = line length.

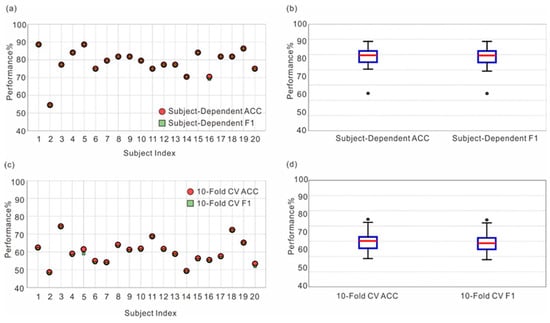

5.5. Individual Classification Performance and Cross-Validation Analysis

Individual classification performance was evaluated using the optimal combination of LLCFS, RFE, and LR, implemented with both 70:30 training–testing split ratio and 10-fold cross-validation (Figure 7). The classification accuracies averaged 78.52% and 60.10% for the training–testing split and cross-validation approaches, respectively. Statistical analysis revealed that classification accuracies significantly exceeded the chance level for both the 70:30 training–testing split (t(19) = 7.22, p < 0.001) and 10-fold cross-validation (t(19) = 6.63, p < 0.001). Participant #1 achieved the highest classification accuracy of 88.64% with 25% feature set selection, while Participant #2 showed the lowest accuracy of 54.55% with 65% feature selection, demonstrating substantial inter-individual variability in neural patterns associated with different forms of referential processing. To further validate that our model captures neural dynamics specific to pronoun resolution, we conducted targeted analyses using only the 1-s window immediately following the critical word, achieving significant above-chance accuracies of 67.61% (subject-dependent) and 63.40% (cross-subject).

Figure 7.

Individual classification performance using train-test split and cross-validation approaches: (a) Subject-dependent classification accuracy and F1 scores across 20 participants using a 70:30 train-test split. (b) Box plots showing the distribution of classification metrics for the subject-dependent method. (c) Classification performance across participants using 10-fold cross-validation. (d) Box plots illustrating the distribution of accuracy and F1 scores in cross-validation analysis.

6. Discussion

6.1. Behavioral Findings

Our behavioral analyses revealed distinct cognitive mechanisms underlying pronoun resolution and nominal reference processing. The data demonstrated that while participants can effectively resolve impersonal pronouns based on prominence features such as topic centrality, this process exhibits significantly reduced accuracy, increased reaction time, and higher individual variability compared to direct nominal reference judgments. These findings suggest that pronoun resolution encompasses more complex mechanisms of referent selection and verification.

Analysis of pronoun resolution tasks (e.g., “The book is on the shelf. Bring it here.”) revealed high accuracy rates (M = 95.56%, range: 79.17–100%) in resolving the pronoun “it” to its intended referent (“the book”) despite the presence of multiple potential antecedents (“the book” and “the shelf”). This finding corroborates previous research emphasizing the crucial role of prominence features in determining pronoun reference [10,11]. In such cases, the topic-central position and prominence of the “book” effectively guide referent selection.

However, comparative analysis with nominal reference processing tasks (e.g., “The book is on the shelf. Bring the book here.”) revealed significant performance differences. Pronoun resolution tasks yielded lower accuracy rates (M = 95.56% vs. 99.10%, p = 0.019) and longer reaction times (M = 813.972 ms vs. 611.827 ms, p < 0.001). These results indicate that pronoun resolution, unlike direct nominal reference, requires sophisticated referent identification processes involving more complex contextual integration mechanisms. This observation aligns with previous studies suggesting that pronoun resolution necessitates simultaneous evaluation of multiple candidate antecedents while integrating diverse linguistic cues across syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic levels [34,35].

Additionally, pronoun resolution exhibited greater performance variability compared to nominal reference tasks, both in accuracy (SD = 5.80% vs. 1.37%) and reaction times (SD = 249.135 ms vs. 165.833 ms). This increased variability suggests substantial individual differences in pronoun resolution strategies, consistent with previous findings indicating that factors such as linguistic experience and working memory capacity modulate pronoun processing efficiency [36,37].

6.2. Neural Correlates

PSD and DE feature analyses, combined with LLCFS-based temporal–statistical feature ranking for classification contribution assessment, demonstrate that pronoun resolution exhibits EEG signatures across frontal, temporal, and parietal electrodes within multiple frequency bands, revealing enhanced neural complexity and processing demands compared to nominal reference tasks.

Across theta, alpha, beta, and gamma frequency bands, both PSD and DE features exhibited substantial differences between pronoun resolution and nominal reference tasks, particularly from frontal, temporal, and parietal channels. These oscillatory patterns are associated with distinct cognitive functions: theta (4–8 Hz) with working memory maintenance, cognitive control, and attentional allocation [38]; alpha (8–13 Hz) with attentional processes and integration [39]; beta (13–30 Hz) with working memory and cognitive control [40]; and gamma (30–45 Hz) with integrative processing [41,42].

From the frontal channels, elevated PSD values were observed in alpha, beta, and gamma bands during pronoun resolution, which is consistent with previous literature linking frontal electrode signals to executive control and working memory [43]. The increased PSD values across these frequency bands indicate enhanced working memory load, heightened attention, and intensified higher-order cognitive processing, respectively [44]. Similarly, substantial DE feature contributions in the gamma band suggest enhanced complexity in information integration processes during pronoun resolution compared to nominal reference tasks [45]. These patterns recorded from frontal electrodes might reflect that pronoun resolution engages working memory involvement for antecedent maintenance, facilitates inter-regional neural coordination, and supports referential decision-making through integrated linguistic information processing. From the temporal channels, significantly higher PSD values in theta bands and substantial DE feature contributions in the beta band were observed during pronoun resolution. These findings align with previous research suggesting temporal electrode signals are associated with language comprehension and semantic processing [46]. This pattern, recorded from temporal channels, might indicate that pronoun resolution engages semantic information retrieval processes and facilitates the establishment of pronoun-antecedent associations. From the parietal channels, increased PSD values in the beta band, decreased values in the alpha band, and substantial DE feature contributions in alpha and beta bands were observed during pronoun resolution. These patterns support previous findings that parietal electrode activity reflects multimodal information integration [47]. These findings recorded from the parietal channel might reflect the integration of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information during pronoun resolution.

The LLCFS feature ranking revealed additional temporal and statistical domain features that significantly contributed to distinguishing between pronoun resolution and nominal reference tasks. These features, in order of contribution magnitude, include kurtosis, line length, the maximum of the first derivative, mean, skewness, variance, peak-to-peak amplitude, the minimum of the first derivative, and zero crossings. Kurtosis and line length, which reflect signal distribution peakedness and complexity [48,49], suggest that the two tasks differ in neuronal activation clustering patterns and language network engagement complexity. The maximum and minimum of the first derivative, established indicators of signal change rates [50], indicate differential neural state transition dynamics between the tasks. Mean, variance, and skewness, which measure baseline activity, fluctuation degree, and distribution asymmetry [51], reveal distinctions in cognitive resource allocation strategies. Peak-to-peak amplitude and zero crossings, reflecting signal intensity range and frequency characteristics [52], suggest that the tasks engage different oscillatory coordination patterns for inter-regional information processing.

Based on the above neurophysiological and classification findings, pronoun resolution and nominal reference tasks engage distinct neural processing mechanisms, as evidenced by differential frequency-domain signatures across distributed electrode locations and complementary temporal–statistical feature patterns. Our analyses of PSD and DE features across frontal, temporal and parietal electrodes with theta, alpha, beta and gamma bands, together with LLCFS feature ranking revealing temporal and statistical domain contributions to classification performance, suggest that pronoun resolution engages more complex neural processing mechanisms compared to nominal reference, reflecting the computational demands of antecedent encoding, retrieval, and selection mechanisms that necessitate coordinated syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information processing. These findings align with previous research. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that pronoun processing activates frontal regions during working memory operations and decision-making, temporal regions during semantic retrieval and conceptual association formation, and parietal regions during multimodal information integration [12,13]. Single-neuron recordings have revealed selective responses to pronoun antecedents in temporal hippocampal neurons, with longer processing latencies for pronouns (600 ms) compared to nouns (210 ms), reflecting the temporal demands of frontal-temporal network coordination in establishing referential relationships [14]. Event-related potential (ERP) studies have revealed that the P200 component indexes early perceptual analysis engaging frontotemporal networks, while the P300 reflects later-stage integration processes recruiting frontoparietal circuits, representing distinct temporal signatures [18,19].

6.3. Methodological Implications

The successful implementation of machine learning techniques in EEG data analysis has demonstrated the capacity to differentiate neural signatures associated with pronoun resolution from nominal reference processing. Our machine learning framework achieved notable subject-dependent classification accuracy (78.52%), comparable to classification performance in analogous linguistic processing studies [53,54]. The integration of LLCFS-RFE yielded robust cross-subject performance (60.10%), consistent with previous EEG-based classification studies of complex language tasks [55,56]. These classification outcomes align with neuroimaging evidence suggesting the engagement of distinct neural networks during pronoun processing [13,57].

Analysis of classification performance revealed substantial inter-individual variability (54.55–88.64%), indicating heterogeneous neural processing patterns during pronoun resolution, consistent with individual differences observed in classroom EEG studies [58]. While most participants maintained accuracy above 70% in the train-test split, cross-validation analysis demonstrated considerable performance variation. This heterogeneity suggests individualized processing strategies, potentially attributable to variations in working memory capacity [13], linguistic experience [37], and cognitive control mechanisms [59]. Previous studies have elucidated the cortical processing of referential expressions, emphasizing the dynamic interaction between language and decision-making systems in natural language comprehension [60,61].

The integration of multi-domain EEG features (temporal, statistical, spectral, spatial, and complexity domains) combined with diverse machine learning techniques (LLCFS, RFE, and LR) has enhanced the classification performance in distinguishing pronoun resolution from nominal reference processing. This machine learning pipeline can be conceptualized within the encoding-decoding framework, where the RFE algorithm acts as an encoder that compresses high-dimensional EEG signals into lower-dimensional feature representations [21], and the LR classifier functions as a decoder to extract cognitive states from these compressed feature representations [62], similar to hybrid CNN-GRU-LSTM architectures with interpretability features [63]. This methodological innovation achieved both remarkable subject-dependent accuracy and demonstrated stable cross-subject performance [59,64]. The complementary analytical approaches effectively capture the rich spatiotemporal dynamics and complex neural patterns underlying pronoun processing, which are distinct from nominal referential mechanisms [13,57].

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates distinct neural mechanisms underlying impersonal pronoun processing compared to nominal reference through a novel integration of behavioral data assessment, multi-domain EEG features analysis, and machine learning approaches. Our findings reveal enhanced neural complexity during pronoun resolution, characterized by differential oscillatory patterns across frontal, temporal, and parietal electrodes within multiple frequency bands, with classification accuracies of 78.52% for subject-dependent analysis and 60.10% for cross-subject validation in distinguishing pronoun resolution from nominal reference tasks. Among all tested combinations of feature selection methods and classifiers, the LLCFS-RFE-LR pipeline demonstrated superior performance in capturing the neural signatures of pronoun resolution. The combined behavioral and neurophysiological data demonstrate that pronoun resolution engages complex mechanisms of referent selection and verification, involving more demanding working memory and information integration processes than direct nominal reference judgments.

While the current findings establish reliable EEG-based indicators for impersonal pronoun processing, subsequent studies should validate these markers across larger populations and diverse linguistic contexts. Future investigations could extend to cross-linguistic comparisons and computational modeling approaches. Additionally, these neurophysiological signatures may contribute to understanding language processing mechanisms and could potentially inform future research on language comprehension assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and Y.Q.; methodology, H.W., Y.Q., W.W., and Y.Y.; software, H.W.; validation, Y.Q. and M.Z.; formal analysis, H.W., Y.Q., H.L., Y.C. and X.S.; investigation, Y.Q.; resources, Y.Q. and H.L.; data curation, Y.Q. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z., H.W., Y.Q., W.W., H.L., Y.C., X.S., and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.Z.; visualization, H.W., Y.Q., and H.L.; supervision, M.Z. and Z.Y.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. and Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is sponsored by the Humanities and Social Sciences Project of the Ministry of Education under Grant No. 24YJCZH443, Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai under Grant No. 25ZR1401270, Shanghai Municipal Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project under Grant No. 2024EYY011, Shanghai Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project under Grant No. 2024EYY015, and National Social Science Fund under Grant No. 18CZX014.

Data Availability Statement

All code used for data analysis in this study is publicly available through the GitHub repository: https://github.com/yingyi-qiu/SR_FS.git (code version: commit 8449c71; accessed on 9 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| LLCFS | Local learning-based clustering feature selection |

| RFE | Recursive feature elimination |

| LR | Logistic regression |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| LMTG | Left middle temporal gyrus |

| M | Mean |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| FOOOF | Fitting oscillations & one-over-F |

| PSD | Power spectral density |

| DE | Differential entropy |

| ADB | Adaptive boosting |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| FSVCM | Feature selection via concave minimization |

| CFS | Correlation-based feature selection |

| UDFS | Unsupervised discriminative feature selection |

| ERP | Event-related potential |

| USST | University of Shanghai for Science and Technology |

| FIR | Finite impulse response |

| ICA | Independent component analysis |

References

- Hobbs, J.R. Resolving Pronoun References. Lingua 1978, 44, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, P.C.; Grosz, B.J.; Gilliom, L.A. Pronouns, Names, and the Centering of Attention in Discourse. Cogn. Sci. 1993, 17, 311–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosse, T.; Kempen, G. Syntactic Structure Assembly in Human Parsing: A Computational Model Based on Competitive Inhibition and a Lexicalist Grammar. Cognition 2000, 75, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Fisher, C. Who’s “She”? Discourse Prominence Influences Preschoolers’ Comprehension of Pronouns. J. Mem. Lang. 2005, 52, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foursha-Stevenson, C.; Nicoladis, E.; Trombley, R.; Hablado, K.; Phung, D.; Dallaire, K. Pronoun Comprehension and Cross-Linguistic Influence in Monolingual and Bilingual Children. Int. J. Biling. 2024, 28, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Gullberg, M.; Indefrey, P. Online Pronoun Resolution in L2 Discourse: L1 Influence and General Learner Effects. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2008, 30, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojnić, U.; Stone, M.; Lepore, E. Discourse and Logical Form: Pronouns, Attention and Coherence. Linguist. Philos. 2017, 40, 519–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almor, A.; Kempler, D.; MacDonald, M.C.; Andersen, E.S.; Tyler, L.K. Why Do Alzheimer Patients Have Difficulty with Pronouns? Working Memory, Semantics, and Reference in Comprehension and Production in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Lang. 1999, 67, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Lai, C.H. Age-Related Differences in Understanding Pronominal Reference in Sentence Comprehension: An Electrophysiological Investigation. Psychol. Aging 2023, 39, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewicz-Özakın, B.; Schumacher, P.B. Anaphoric Pronouns and the Computation of Prominence Profiles. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2022, 51, 627–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.D.; Arnold, J.E. The Frequency of Referential Patterns Guides Pronoun Comprehension. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2022, 49, 1325–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Hale, J. Decoding the Silence: Neural Bases of Zero Pronoun Resolution in Chinese. Brain Lang. 2022, 224, 105050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouardi, L.; Yeou, M.; Faroqi-Shah, Y. Neural Correlates of Pronoun Processing: An Activation Likelihood Estimation Meta-Analysis. Brain Lang. 2023, 246, 105347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, D.E.; Self, M.W.; Possel, J.K.; Peters, J.C.; van Straaten, E.C.W.; Idema, S.; Baaijen, J.C.; van der Salm, S.M.A.; Aarnoutse, E.J.; van Klink, N.C.E.; et al. Pronouns Reactivate Conceptual Representations in Human Hippocampal Neurons. bioRxiv 2024, 1484, 600044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M.; Hillyard, S.A. Event-Related Brain Potentials to Semantically Inappropriate and Surprisingly Large Words. Biol. Psychol. 1980, 11, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, K.A.; Urbach, T.P.; Kutas, M. Probabilistic Word Pre-Activation during Language Comprehension Inferred from Electrical Brain Activity. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coopmans, C.W.; Nieuwland, M.S. Dissociating Activation and Integration of Discourse Referents: Evidence from ERPs and Oscillations. Cortex 2020, 126, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glim, S.; Körner, A.; Härtl, H.; Rummer, R. Early ERP Indices of Gender-Biased Processing Elicited by Generic Masculine Role Nouns and the Feminine–Masculine Pair Form. Brain Lang. 2023, 242, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, T.; Langlois, V.J.; Novick, J.M.; Kim, A.E. Theta-Band Neural Oscillations Reflect Cognitive Control during Language Processing. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2024, 153, 2279–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Cheung, Y. Feature Selection and Kernel Learning for Local Learning-Based Clustering. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 33, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Weston, J.; Barnhill, S.; Vapnik, V. Gene Selection for Cancer Classification Using Support Vector Machines. Mach. Learn. 2002, 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, G.S.; McKoon, G.; Ratcliff, R. The Activation of Antecedent Information during the Processing of Anaphoric Reference in Reading. J. Verbal Learning Verbal Behav. 1983, 22, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Swaab, T.Y.; Ferreira, F. Electrophysiological Evidence for an Independent Effect of Memory Retrieval on Referential Processing. J. Mem. Lang. 2018, 102, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chang, R.; Wang, Z. A Review on the Cognitive Neural Mechanisms of Anaphor Processing During Language Comprehension. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 128, 2191–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, D.; Peterson, D.A.; Anderson, C.W.; Thaut, M.H. Comparison of Linear, Nonlinear, and Feature Selection Methods for EEG Signal Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2003, 11, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdumalikov, S.; Kim, J.; Yoon, Y. Performance Analysis and Improvement of Machine Learning with Various Feature Selection Methods for EEG-Based Emotion Classification. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysels, E.; Renevey, P.; Celka, P. SVM-Based Recursive Feature Elimination to Compare Phase Synchronization Computed from Broadband and Narrowband EEG Signals in Brain–Computer Interfaces. Signal Process. 2005, 85, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Cross-Subject EEG Feature Selection for Emotion Recognition Using Transfer Recursive Feature Elimination. Front. Neurorobot. 2017, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, A.M.; Attia, A.-F.; El-Behery, H. Optimization of EEG-Based Wheelchair Control: Machine Learning, Feature Selection, Outlier Management, and Explainable AI. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.A. Correlation-Based Feature Selection of Discrete and Numeric Class Machine Learning. (Working Paper, No. 00/08); University of Waikato, Department of Computer Science: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2000; ISSN 1170-487X. [Google Scholar]

- Skonja, M.R. Igor Kononenko Theoretical and Empirical Analysis of ReliefF and RReliefF. Mach. Learn. 2003, 53, 23–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.S.; Mangasarian, O.L. Feature Selection via Concave Minimization and Support Vector Machines. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–27 July 1998; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, H.T.; Ma, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, X. ℓ2,1-Norm Regularized Discriminative Feature Selection for Unsupervised Learning. In Proceedings of the IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Barcelona Catalonia, Spain, 16–22 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, E.; Runner, J.T.; Sussman, R.S.; Tanenhaus, M.K. Structural and Semantic Constraints on the Resolution of Pronouns and Reflexives. Cognition 2009, 112, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rij, J.; van Rijn, H.; Hendriks, P. How WM Load Influences Linguistic Processing in Adults: A Computational Model of Pronoun Interpretation in Discourse. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2013, 5, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, M.S.; Van Berkum, J.J.A. Individual Differences and Contextual Bias in Pronoun Resolution: Evidence from ERPs. Brain Res. 2006, 1118, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.E.; Strangmann, I.M.; Hwang, H.; Zerkle, S.; Nappa, R. Linguistic Experience Affects Pronoun Interpretation. J. Mem. Lang. 2018, 102, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. EEG Alpha and Theta Oscillations Reflect Cognitive and Memory Performance: A Review and Analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999, 29, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misselhorn, J.; Friese, U.; Engel, A.K. Frontal and Parietal Alpha Oscillations Reflect Attentional Modulation of Cross-Modal Matching. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proskovec, A.L.; Wiesman, A.I.; Heinrichs-Graham, E.; Wilson, T.W. Beta Oscillatory Dynamics in the Prefrontal and Superior Temporal Cortices Predict Spatial Working Memory Performance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon-Baudry, C.; Bertrand, O. Oscillatory Gamma Activity in Humans and Its Role in Object Representation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasei, T.; Gediya, H.; Ravan, M.; Santhanakrishnan, A.; Mayor, D.; Steffert, T. Investigating Brain Responses to Transcutaneous Electroacupuncture Stimulation: A Deep Learning Approach. Algorithms 2024, 17, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, J.A.; Zaveri, H.P.; Goncharova, I.I.; Distasio, M.M.; Papademetris, X.; Spencer, S.S.; Spencer, D.D.; Constable, R.T. Effects of Working Memory Load on Oscillatory Power in Human Intracranial EEG. Cereb. Cortex 2008, 18, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başar, E.; Başar-Eroglu, C.; Karakaş, S.; Schürmann, M. Gamma, Alpha, Delta, and Theta Oscillations Govern Cognitive Processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2001, 39, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.-N.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Lu, B.-L. Differential Entropy Feature for EEG-Based Emotion Classification. In Proceedings of the 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Diego, CA, USA, 6–8 November 2013; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Forseth, K.J.; Donos, C.; Rollo, P.S.; Tandon, N. The spatiotemporal dynamics of semantic integration in the human brain. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molholm, S.; Sehatpour, P.; Mehta, A.D.; Shpaner, M.; Gomez-ramirez, M.; Ortigue, S.; Dyke, J.P.; Schwartz, T.H.; Foxe, J.J. Audio-Visual Multisensory Integration in Superior Parietal Lobule Revealed by Human Intracranial Recordings. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 96, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnevis, S.A.; Sankar, R. Applications of Higher Order Statistics in Electroencephalography Signal Processing: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 13, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, A.; Ramesh, A.; Mitra, A.; Majumdar, K. Automatic Seizure Detection by Modified Line Length and Mahalanobis Distance Function. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2018, 44, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, A.; Wennberg, A.; Zetterberg, L.H. Computer Analysis of EEG Signals with Parametric Models. Proc. IEEE 1981, 69, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, A.; Khandnor, P.; Chand, T. A Comparative Analysis of Signal Processing and Classification Methods for Different Applications Based on EEG Signals. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 40, 649–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subha, D.P.; Joseph, P.K.; Acharya, U.R.; Lim, C.M. EEG Signal Analysis: A Survey. J. Med. Syst. 2010, 34, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, C.; Mendez-Orellana, C.; Herff, C.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. Identification of Perceived Sentences Using Deep Neural Networks in EEG. J. Neural Eng. 2024, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puffay, C.; Vanthornhout, J.; Gillis, M.; Clercq, P.D.; Accou, B.; Van Hamme, H.; Francart, T. Classifying Coherent versus Nonsense Speech Perception from EEG Using Linguistic Speech Features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, C.; Wang, G.; Yin, Z. Assessing Distinct Cognitive Workload Levels Associated with Unambiguous and Ambiguous Pronoun Resolutions in Human-Machine Interactions. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, B.M.; Gurrin, C.; Healy, G. DERCo: A Dataset for Human Behaviour in Reading Comprehension Using EEG. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeko, M.; Hirshfield, L.; Doherty, E.; Southwell, R.; D’Mello, S.K. Cortical Cognitive Processing during Reading Captured Using Functional-near Infrared Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, R.; Chadha, S.; Prince, A.A.; Murugappan, M.; Islam, M.S.; Sumon, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.E.H. A Machine Learning Framework for Classroom EEG Recording Classification: Unveiling Learning-Style Patterns. Algorithms 2024, 17, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko, E.; Behr, M.K.; Kanwisher, N. Functional Specificity for High-Level Linguistic Processing in the Human Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16428–16433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, C.T.; Clark, R.; Gunawardena, D.; Ryant, N.; Grossman, M. FMRI Evidence for Strategic Decision-Making during Resolution of Pronoun Reference. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Monroe, W.; Ritter, A.; Jurafsky, D.; Galley, M.; Gao, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dialogue Generation. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pazdera, J.K.; Kahana, M.J. EEG Decoders Track Memory Dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baibulova, M.; Aitimov, M.; Burganova, R.; Abdykerimova, L.; Sabirova, U.; Seitakhmetova, Z.; Uvaliyeva, G.; Orynbassar, M.; Kassekeyeva, A.; Kassim, M. A Hybrid CNN–GRU–LSTM Algorithm with SHAP-Based Interpretability for EEG-Based ADHD Diagnosis. Algorithms 2025, 18, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, N.; Mirman, D.; Thompson-Schill, S.L. The Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex Facilitates Processing of Sentential Context to Locate Referents. Brain Lang. 2016, 157–158, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).