1. Introduction

Industrial robots (IRs) serve as essential equipment for high-precision manufacturing, supporting applications ranging from automotive welding to semiconductor assembly. They significantly improve productivity, positioning consistency, and personnel safety. According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), global installations of IRs reached 542,000 units in 2024, with China accounting for 54% of the total. The IFR forecasts a positive growth trajectory, with the annual installation rate at an average of approximately 7% in the coming years [

1]. However, early-stage mechanical failures in key drivetrain components continue to compromise positioning accuracy, operational reliability, and service life. Consequently, there is an urgent industrial demand for diagnostic strategies that ensure high accuracy and robustness to minimize unplanned downtime and operational costs.

However, addressing this demand presents fundamental challenges in terms of practical deployability and superior diagnostic capabilities. Traditional methods for diagnosing mechanical faults rely primarily on vibration or acoustic sensing [

2,

3,

4]. For instance, He et al. [

5] directly mounted vibration sensors on robot links to identify harmonic reducer faults, while Wu et al. [

6] utilized accelerometer signals enhanced by an adaptive particle swarm optimization algorithm to learn discriminative features for IR fault diagnosis. Liu et al. [

7] further developed a monitoring framework based on acoustic emission for harmonic reducers. Despite their promise in laboratory settings, these sensing techniques face considerable barriers to real-world implementation, including restrictive mounting requirements, susceptibility to environmental interference, and high hardware costs. Specifically, triaxial accelerometers often require invasive installation, which is particularly challenging for sealed joints and high-speed axes. The fidelity of the acquired data is highly dependent on sensor placement precision in industrial robots. Hu et al. [

8] emphasized that an optimized configuration is essential for reliable health assessment, as mispositioned sensors degrade signal integrity and diagnostic accuracy. Similarly, acoustic sensors are prone to contamination from ambient factory noise. Moreover, retrofitting production-line industrial robots with multi-axis sensing systems involves significant hardware investment and additional signal processing expenses. These collective challenges ultimately diminish the economic feasibility of widespread industrial deployment.

Energy-Based Maintenance (EBM) has emerged as a pivotal theoretical and practical framework for modern predictive maintenance, positing that energy-related metrics serve as primary and direct indicators of system health and mechanical integrity [

9,

10,

11]. In electromechanical systems like IRs, the motor current is a fundamental energy-based signal, directly reflecting electromagnetic torque and the efficiency of the drivetrain. Therefore, from an EBM perspective, motor current signature analysis (MCSA) is not merely a convenient alternative but the theoretically preferred modality for fault diagnosis. Therefore, MCSA aligns perfectly with the EBM paradigm by offering a compelling solution to these deployment barriers, providing a non-invasive and economically feasible path for reliable maintenance. This approach has several advantages: (1) Non-invasive and Cost-effective Implementation: Leveraging existing current monitoring in servo drives, it eliminates the need for additional sensors or retrofitting. (2) Strong resilience to environmental conditions: Current measurements are largely unaffected by factors such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, dust, and mechanical vibrations, enabling stable signal acquisition even in harsh industrial settings. (3) Theoretical Alignment with EBM: Most significantly, it provides direct electromechanical coupling, capturing fault-induced torque variations. This makes the current signal a primary energy-based indicator, fundamentally aligning with EBM’s core principle.

Signal processing techniques have become important tools for diagnostic applications [

12]. For instance, Raouf et al. [

13] used statistical metrics and kinetic parameters derived from motor currents for dimensionality reduction. Lee et al. [

14] applied wavelet packet decomposition to extract degradation-sensitive indicators, while Wang et al. [

15] integrated variational mode decomposition with support vector machines for fault detection. However, manual feature engineering remains subjective and often limits the generalization of the model across different IRs, necessitating more robust data-driven approaches.

Deep Learning (DL) has consequently emerged as the predominant methodology, owing to its capacity for autonomous feature representation learning directly from raw sensor signals. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are widely employed to extract discriminative spatial features, eliminating the labor-intensive process of manual feature engineering [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, conventional CNNs are constrained by fixed kernel sizes and local receptive fields, which limit their ability to model long-range temporal dependencies. To mitigate this deficiency, Recurrent Neural Networks, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM), are utilized to model complex temporal dynamics and non-stationary fault signatures [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Recognizing the need to capture both spatial and temporal dependencies simultaneously, researchers have developed hybrid models such as CNN-LSTM/CNN-BiLSTM, which have demonstrated superior diagnostic performance compared to individual models [

25,

26,

27].

Despite these advances, a fundamental limitation persists: conventional CNNs and LSTMs operate on Euclidean data, thereby failing to capture the complex, non-Euclidean interdependencies and system-level interactions. Although Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) attempt to bridge this gap by modeling topological relationships [

28,

29,

30], conventional GNNs use fixed aggregation weights determined solely by graph connectivity, which ignores the physical significance of interactions and lacks adaptive learning. While Graph Attention Networks (GATs) and Multi-head GATs (MGATs) introduce adaptive weighting mechanisms [

31,

32], their application in IR fault diagnosis often lacks synergistic integration with multi-scale feature extraction and temporal sequence modeling.

However, EBM provides a theoretical rationale for utilizing motor current signals. Existing deep learning methods have not fully exploited the rich informational potential of current signals for IR fault diagnosis. Diagnostic performance remains constrained by three key issues: (1) The challenge of extracting discriminative features comprehensively across multiple scales. (2) The difficulty in dynamically modeling the complex, non-Euclidean interdependencies among features. (3) The ineffective integration of temporal dynamics with structural relationships. These problems constrain the model’s discriminative power and prevent the full realization of reliable, cost-effective maintenance solutions.

To bridge the identified theory-practice gap in EBM and enable highly accurate and robust fault diagnosis for reliable maintenance of IRs, this study proposes a hybrid deep learning framework, termed the Multi-head Graph Attention Network with Multi-scale CNNBiLSTM Fusion (MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM). This novel architecture enables an end-to-end synergistic fusion by integrating a multi-head graph attention mechanism to model complex feature interdependencies and a multi-scale CNNBiLSTM to hierarchically extract multi-resolution discriminative features.

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed energy-metric-driven framework for IR fault diagnosis.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Based on the EBM principle, motor current is established as the most effective and practical choice for enabling cost-efficient and scalable IR fault diagnosis, owing to its direct reflection of torque coupling dynamics under mechanical faults. A corresponding dataset of motor current has been acquired from IRs operating under diverse fault scenarios.

This study extends the EBM theoretical framework for IR fault diagnosis by proposing an MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM architecture that integrates MGAT with MCNNBiLSTM, effectively capturing both temporal dynamics at varying resolutions and structural dependencies within feature graphs. This dual-path design facilitates the fusion of temporal-spectral attributes with spatio-graph relationships. Comparative trials demonstrate its consistent superiority over competing architectures, including LCNNBiLSTM, SCNNBiLSTM, MCNNBiLSTM, GAT, and MGAT.

The research of these current signal-based fault diagnosis models reveals that the application of spectral preprocessing techniques yields a statistically significant enhancement in diagnostic performance. Based on our experimental results, we subsequently undertook a comprehensive and systematic analysis to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms responsible for this observed performance improvement.

To evaluate diagnostic robustness under realistic industrial operating regimes and cost constraints, noise signal injection was employed to simulate high-electromagnetic-interference environments and low-cost, low-resolution ADC implementations. The proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM model demonstrated consistent performance superiority over CNNBiLSTM variants, GAT, and MGAT benchmarks across these challenging scenarios. These results verify the model’s practical applicability in electrically noisy industrial settings and its compatibility with low-cost, low-resolution hardware. This capability directly supports the industry’s goal of achieving reliable predictive maintenance while overcoming deployment challenges associated with hardware costs and environmental interference.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows:

Section 2 details the theoretical background and framework of the proposed fault diagnosis method for IRs.

Section 3 presents the experimental results, while

Section 4 provides a detailed discussion. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Theoretical Background and Framework of Proposed Method

2.1. Signal Selection and Fault Definition

2.1.1. Signal Selection

For IRs, current-based fault diagnosis is often more practical to deploy due to its inherent compatibility with existing drive systems and standardized data interfaces. Unlike vibration monitoring, which relies on expensive accelerometers susceptible to installation misalignment, or acoustic methods that are vulnerable to ambient noise, MCSA utilizes current sensors already embedded in servo systems. A detailed comparison of MCSA with vibration and acoustic methods for fault diagnosis is presented in

Figure 2. By avoiding additional hardware, this approach reduces installation complexity and directly captures electromagnetic torque variations induced by mechanical faults. Consequently, MCSA enables low-cost deployment and millisecond-level fault response, meeting the high-reliability and real-time demands of industrial applications.

2.1.2. Fault Definition

In the evaluation of robotic performance, beyond standard product specifications, end-effector positioning repeatability represents a pivotal criterion for fault stratification. This priority originates from its direct correlation with core mechanical integrity and operational performance, in contrast to indirect indicators such as vibration or temperature. rigorously quantifies positional consistency during repeated task executions, and is sensitive to underlying mechanical degradation mechanisms.

As

Figure 3 shows, these mechanisms are primarily categorized into transmission system anomalies, structural system instabilities, motion interface imperfections, and environmental interaction perturbations. Collectively, these factors determine the positional consistency of IR manipulators during cyclic operations. This makes positioning repeatability serve as a powerful and robust diagnostic tool for mechanical faults in IRs.

As shown in

Figure 4, the schematic illustrates the methodology for measuring positioning repeatability of our IR end-effector employing the laser displacement sensor (LK-G85, Keyence, Osaka, Japan). The measured positioning repeatability

is calculated using the following equation:

where

,

, and

are the measured positioning repeatability values along the X-axis, Y-axis, and Z-axis, respectively.

is the total number of measurements.

Given the OEM-specified baseline

= 0.05 mm,

Table 1 classifies fault severity levels for IRs based on

deviation thresholds.

Figure 5 illustrates a systematic data acquisition framework designed to construct a comprehensive dataset reflecting real-world industrial scenarios. Under continuous cyclic operation, industrial robots undergo gradual mechanical degradation, which manifests as a measurable escalation in end-effector positioning repeatability error. Guided by the stratification criteria defined in

Table 1, this degradation spectrum is categorized into five distinct severity levels ranging from normal operation to critical failure risk. Subsequently, motor current signals are acquired from IR systems corresponding to these specific fault categories. Data acquisition across these levels provides the necessary dataset for developing intelligent fault diagnosis models.

2.2. Convolutional Neural Network and Long Short-Term Memory

2.2.1. Convolutional Neural Network

CNNs provide data-driven fault diagnosis through hierarchical deep learning architectures. As feed-forward networks, they employ cascaded convolution and pooling operations to learn discriminative, multi-level feature representations automatically. This architecture is particularly effective for processing complex signal modalities, including spectrograms and multivariate time-series data. Fundamentally, these networks employ weight-sharing convolutional filters to capture spatially invariant features.

The convolution operation at the layer

is defined as

where

is the spatial position index.

is the convolutional kernel size.

and

are the weight kernel and bias term for the

-th filter.

) is the input feature map at position

.

In CNNs, max-pooling is widely used as the predominant downsampling method. This process extracts the most prominent response within each sub-region, effectively capturing distinctive local patterns while curbing computational demands through dimensionality reduction. The output feature map at the

-th layer for the

-th channel after pooling can be described as

where

indexes output spatial positions after pooling.

denotes the output of the convolution layer at position

in the

-th channel, and

represents the width of the pooling kernel. The index

spans all spatial positions within the pooling window associated with the output position

.

2.2.2. Long Short-Term Memory

LSTM networks overcome critical shortcomings of traditional recurrent neural networks, including the temporal gradient vanishing and explosion phenomena, while preserving robust modeling of sequential dependency. This architecture regulates information flow across time steps through dedicated gating mechanisms—input, forget, and output gates, as depicted in

Figure 6.

The core innovation lies in the memory cell and how its gates meticulously regulate state updates:

Input Gate: Regulates integration of current input

xt and the previous hidden state

into the cell state

:

Forget Gate: Controls the retention or discard of the historical cell state

:

Output Gate: Modulates the exposure of the cell state

to update the hidden state

:

The memory cell state evolves through

where

is the sigmoid activation function,

denotes element-wise multiplication;

,

,

and

are bias vectors specific to each component, respectively;

and

represent input-hidden and hidden-hidden weight matrices, respectively, with unique parameters for gates

and the cell

. At each timestep

, gate activations and state transitions derive from the current input

and the previous hidden state

.

2.3. Framework of the CNNBiLSTM-Based Fault Diagnosis Model

Industrial robot systems operating under complex dynamic conditions generate highly coupled and non-stationary signals, which pose significant challenges to conventional fault diagnosis approaches. Current deep learning approaches also face specific shortcomings: CNNs extract spatially local features through fixed-kernel convolutions but lack dynamic temporal modeling capability, while BiLSTM networks capture temporal dependencies yet inherently ignore spatial correlations.

To address these issues, we employ a CNNBiLSTM model that combines spatial feature extraction with bidirectional temporal modeling. In this framework, convolutional layers identify discriminative spatial patterns, while the BiLSTM modules capture contextual temporal dependencies. This combination yields a unified spatiotemporal representation, which enhances the accuracy of fault diagnosis in IRs.

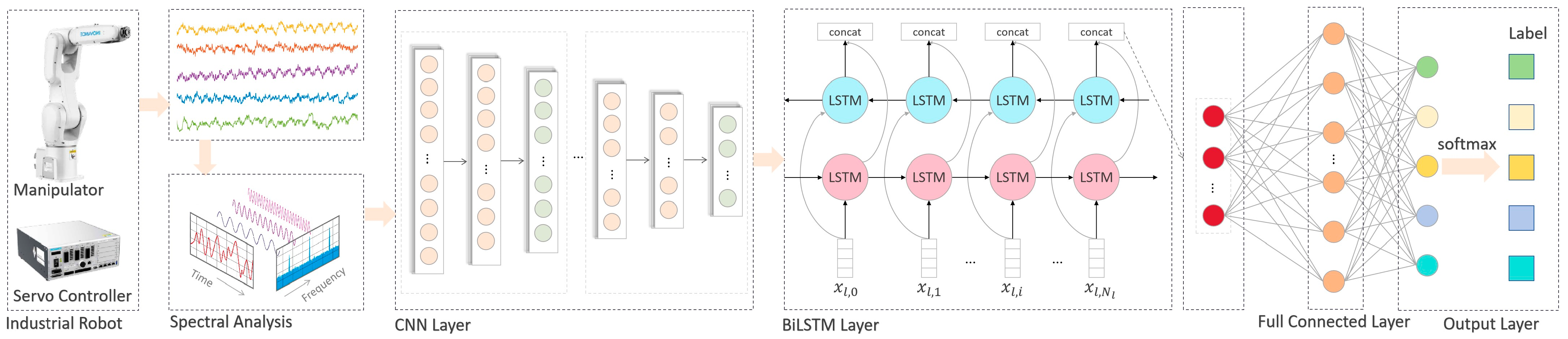

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the CNNBiLSTM fault diagnosis framework processes signals through a hierarchical cascade:

Spectral Transformation Module: The initial processing stage employs the Fourier transform to convert the raw time-domain signals into the frequency-domain representations. This transformation reveals latent spectral features that are critical for distinguishing different fault types.

Convolutional Layers: These layers apply convolutional kernels to the spectral inputs to extract salient spatial features indicative of fault signatures.

Pooling Layers: Subsequent max-pooling operations downsample the feature maps by retaining the most activated values, which serves to reduce data dimensionality and enhance invariance to small signal shifts.

BiLSTM Layers: The spatial features are then sequenced and processed by BiLSTM layers. By analyzing the sequence in both forward and backward directions, this module captures the temporal evolution of fault patterns across operational cycles.

Fully Connected Layers: The high-level spatiotemporal features from the BiLSTM are integrated by fully connected layers, combining them into a unified representation for final classification.

Output Layer: A softmax function produces the final fault probability distribution, and the entire network is trained by minimizing the cross-entropy loss.

2.4. Framework of the MCNNBiLSTM-Based Fault Diagnosis Model

The complex nonlinear dynamics inherent in IR systems distribute fault-related features across multiple temporal scales, requiring multi-resolution analysis for accurate diagnosis. Although standard CNNBiLSTM models track temporal evolution, their fixed-scale convolutional kernels are inadequate for separating overlapping fault signatures that reside in distinct spectrotemporal regions. This inflexibility of the receptive fields limits multi-scale feature adaptation and impedes the modeling of cross-scale correlations.

We present a multi-scale CNNBiLSTM (MCNNBiLSTM) framework for IR fault diagnosis. The model features a dual-branch architecture designed to learn hierarchical fault representations. As shown in

Figure 8, it comprises two complementary feature extraction pathways: a large-scale branch (LCNNBiLSTM) captures gradual degradation trends, while a small-scale branch (SCNNBiLSTM) identifies transient fault signatures. Each branch employs BiLSTM modules to model temporal dependencies. Subsequently, the outputs are concatenated to integrate multi-scale temporal features, thereby enhancing the robustness of fault diagnosis.

2.5. Framework of the GAT/MGAT-Based Fault Diagnosis Model

2.5.1. Graph Attention Network

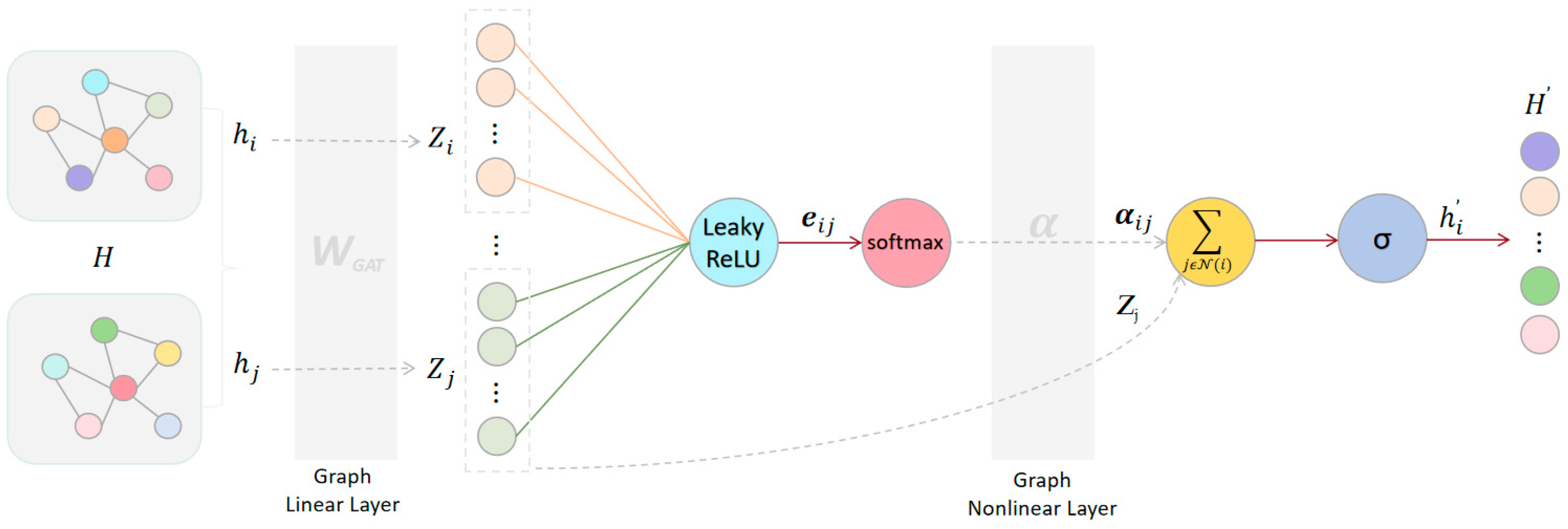

Graph Attention Networks (GATs) enhance standard graph convolutional structures by integrating a masked self-attention mechanism, which dynamically computes attention weights for neighboring nodes. This design enables GATs to focus on the most relevant features when combining information from neighboring nodes. This process strengthens important structural patterns while reducing noise interference. Consequently, GATs generate topology-aware feature representations that significantly improve the robustness and classification accuracy of graph-based diagnostic systems.

GATs operate on graph-structured data characterized by a node feature matrix

, where each node

carries a

-dimensional feature vector within an

-node topology. Through attention-driven nonlinear transformations, the architecture derives discriminative representations in latent topological spaces:

where

defines the graph connectivity, and

denotes trainable parameters. The output embeddings

with

demonstrate enhanced representational capacity for fault patterns.

The transformation involves two sequential stages, as shown in

Figure 9:

A trainable shared parameter matrix

transforms input features into a latent representation:

This transformation maintains inherent structural relationships while simultaneously capturing complex feature representations.

- 2.

Attention-Driven Aggregation

With graph attention mechanisms, normalized attention weights quantify the relational significance of neighbors for each central node .

Attention Coefficient:

where

denotes the attention parameter vector, and

represents feature concatenation.

Normalized Attention Weights:

where

defines the neighborhood of node

, with

and

being the node and edge sets of the graph, respectively.

The aggregated feature representation is given by

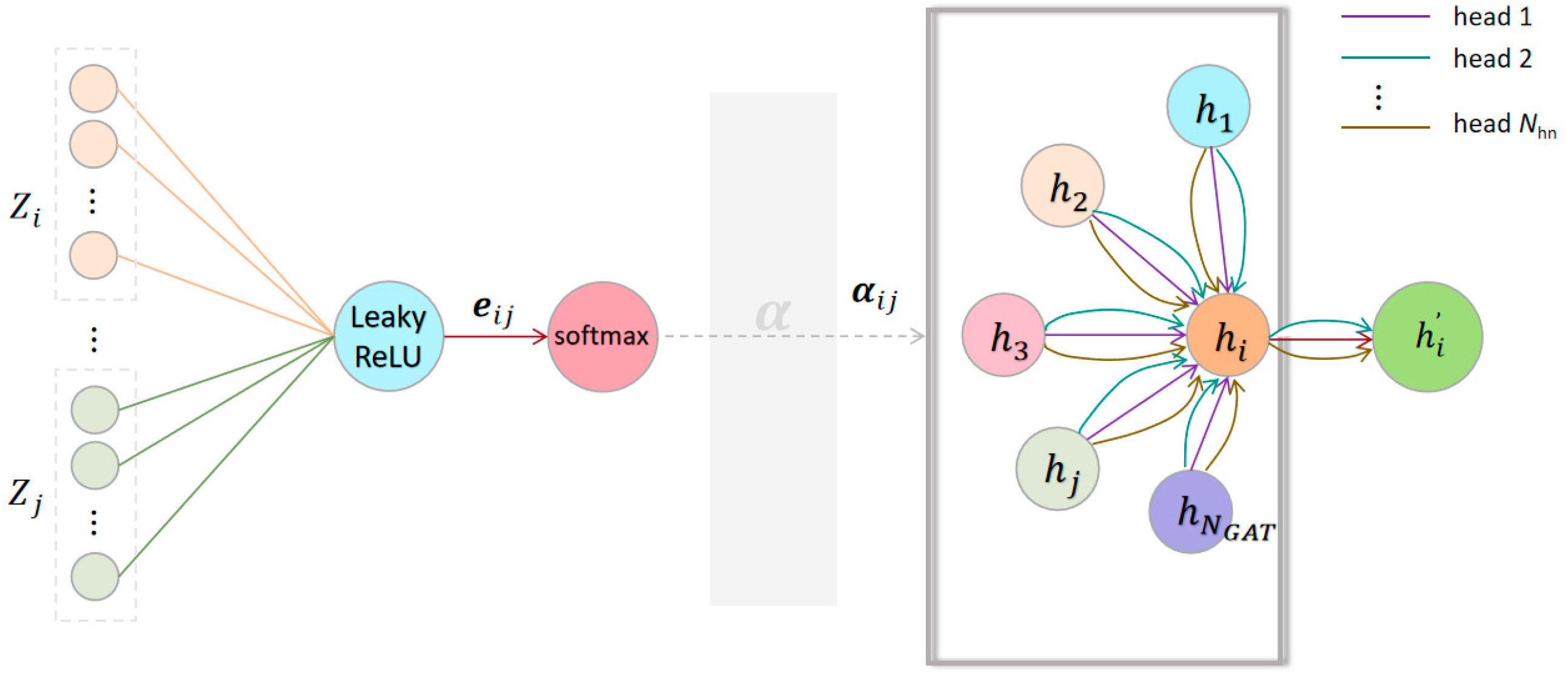

2.5.2. Multi-Head GAT-Based Fault Diagnosis Model

To improve learning stability, the multi-head attention mechanism extracts features in parallel. As shown in

Figure 10, it employs multiple independent attention units, each capturing a distinct hidden representation. Then, these outputs are combined into a unified feature vector.

This process generates two different output representations:

where

is the number of heads.

- 2.

Averaged Features: An alternative approach combines outputs via feature averaging, which produces stable representations with reduced dimensionality.

In this study, the second strategy was adopted to optimize computational efficiency and operational resilience.

Figure 11 illustrates the GAT/MGAT-based fault diagnosis model for IRs.

2.6. Framework of the MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM-Based Fault Diagnosis Model

Accurate fault diagnosis in IRs requires the concurrent analysis of complex temporal dynamics and spatial dependencies within sensor data. To address this challenge and further improve diagnostic accuracy, we propose MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM, a novel architecture integrating Multi-Graph Attention Network (MGAT) with Multi-scale Convolutional Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network (MCNNBiLSTM) for IR fault diagnosis, as illustrated in

Figure 12.

This synergistic design capitalizes on complementary strengths: MCNNBiLSTM captures multi-resolution features and bidirectional long-range temporal dynamics, while MGAT directly models heterogeneous structural dependencies across multi-relational graphs. The integrated framework comprehensively characterizes inherent spatiotemporal interactions in the complex industrial system. It preserves essential temporal dynamics while substantially enhancing spatial discriminative capacity, ultimately achieving improved fault classification accuracy.

The complete MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM fault diagnosis model follows a structured workflow, as detailed in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM Fault Diagnosis Model |

Input: Raw joint current signals

Output: Predicted class probabilities

1: Procedure Spectral Transformation Module ():

2:

3: return

4: end Procedure

5: Procedure MCNNBiLSTM Module ():

6://Branch 1: LCNNBiLSTM

7:

8: for =1 to do

9: if then

10:

11: end if

12: , {Conv, ReLU, MaxPool}

13: end for

14:

15:

16: for = 1 to do

17: if then

18:

19: end if

20: , {BiLSTM}

21: end for

22:

23://Branch 2: SCNNBiLSTM

24:

25: for = 1 to do

26: if then

27:

28: end if

29: , {Conv, ReLU, MaxPool}

30: end for

31:

32:

33: for = 1 to do

34: then

35:

36: end if

37: , {BiLSTM}

38: end for

39:

40://Feature fusion and projection

41:

42:

43: return

44: end Procedure

45: Procedure MGAT Module ()

46:

47: for = 1 to do

48: then

49:

50: end if

51:

{Multi-head GAT, BatchNorm, ReLU}

52: end for

53:

54: return

55: end procedure

56: Procedure Feature Fusion & Classification (, )

57:

58:

59:

60:

61: return

62: end procedure |

This algorithm executes the spectral transformation, the MCNNBiLSTM module, the MGAT module, and the feature fusion & classification module in sequence to obtain the IR fault diagnosis result.

Raw joint current signals sampled at from industrial robot servo drives. and are signal length and batch size, respectively.

The Fourier transform converts time-domain signals to frequency-domain representations , which corresponds to lines 1–4 in Algorithm 1. denotes the number of frequency bins (-point FFT).

- 2.

MCNNBiLSTM Module

The MCNNBiLSTM module implements a dual-branch architecture for extracting multi-scale spatiotemporal features. The complete algorithmic procedure is detailed in Algorithm 1 (lines 5–44).

The LCNNBiLSTM branch processes spectral features through CNN layers followed by BiLSTM layers, producing the output .

The SCNNBiLSTM branch follows a similar structure with independent parameters ( CNN layers and BiLSTM layers), producing the output .

The outputs from both branches are concatenated and linearly projected to obtain the final MCNNBiLSTM representation .

- 3.

MGAT Module

The MGAT module processes spectral features to capture interdependencies through graph attention mechanisms. As outlined in Algorithm 1 (lines 45–55), the module applies graph attention layers, with the final graph representation obtained via linear projection.

- 4.

Feature Fusion & Classification Module

Following the procedure in Algorithm 1 (lines 56–62), the outputs from MCNNBiLSTM and MGAT modules are concatenated, processed through a fully connected layer, and classified via softmax activation to obtain the final fault diagnosis probabilities .

The cross-entropy loss function quantifies the discrepancy between predicted class probabilities and ground-truth labels by computing the negative log-likelihood of the true class. Formally, for a true label vector

and predicted probability vector

, the loss function

is defined as

where

is the

-th compomemt of

(1 for true class, 0 otherwise);

is the predicted probability of class ;

is the number of classes.

The predicted class label is obtained through

The complete optimization objective minimizes the expected cross-entropy over the training dataset

:

where

encompasses all trainable parameters in the fault diagnosis model.

2.7. Experiment Methodology

Industrial robot systems exhibit complex fault signatures during sustained operation. The combined effect of mechanical wear, transient collisions, and thermal stress causes dynamically evolving failure mechanisms throughout operational lifespans. During extended uninterrupted service cycles, cumulative wear in transmission components progressively degrades end-effector positioning repeatability, which is a key performance metric meeting production specification standards for industrial robots. Consequently, this loss of positioning repeatability provides a measurable proxy for mechanical degradation, serving as a critical prognostic indicator of system health.

To quantify these failure modes, we recorded current signatures at different fault severity levels. The severity was determined based on both positioning repeatability tolerances and assessments from the maintenance team. Five operational states are defined: Normal, Minor, Moderate, Severe, and Critical. Details of the dataset are provided in

Table 2.

In our IRs, the analog current signal is discretized through a servo-controlled system equipped with a sigma-delta (ΣΔ) ADC, achieving 15-bit effective resolution to ensure high-fidelity signal acquisition. A sampling frequency of = 1 kHz is employed. The discrete-time sequence, denoted as ( undergoes subsequent digital processing for temporal or spectral analysis.

The study presents MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM, an end-to-end fault diagnosis model for IRs that directly identifies failure modes from motor current signatures. To benchmark its performance, we compare it against several established architectures: CNNBiLSTM with varying convolutional kernel scales, MCNNBiLSTM, GAT, and MGAT. Their network structures are illustrated in

Table 3.

To ensure a fair comparison by minimizing parametric influences, MCNNBiLSTM maintains architectural parity with both LCNNBiLSTM and SCNNBiLSTM across all shared components. The only differences lie in the feature fusion layer and the subsequent linear transformation layer. Similarly, MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM inherits core parameters identically from its constituent MGAT and MCNNBiLSTM modules, with changes strictly localized to the same feature fusion and downstream linear layers. The MGAT employs a multi-head attention mechanism with three attention heads. Model training employed the following experimental configuration: batch size was set to 128, epochs to 300, the optimizer to Adam, the learning rate to 1 × 10−3, and the loss function to cross-entropy loss.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of fault diagnosis models, experiments were designed with distinct cases based on different evaluation objectives, as shown in

Table 4.

In practical engineering applications, IRs operate in diverse and complex environments where electromagnetic interference inevitably degrades acquired current signals. Furthermore, cost-driven engineering constraints often necessitate lower-resolution ADC sampling. To evaluate fault diagnosis robustness under such compromised signal acquisition scenarios, Gaussian white noise was injected into current signals at controlled signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), where SNR is expressed as

where

and

represent the signal power and noise power, respectively.

To mitigate model overfitting risks, a five-fold cross-validation protocol was rigorously implemented. The dataset was partitioned into five non-overlapping folds. During each training-validation iteration, four folds constituted the training subset while the remaining fold served as the validation subset. This validation scheme quantifies robust diagnostic accuracy for all compared methodologies.

The accuracy of the fault model was calculated using the following equation:

where

and

are true position and false negative of the

-th fold cross-validation, respectively.

3. Results

To assess the inherent diagnostic challenge posed by raw sensor data, we first examined the motor current signals in both the time and frequency domains across varying fault severity levels.

Figure 13 characterizes the motor current signatures across varying fault severity levels in robot joints.

As shown, the raw time domain current signals exhibit high similarity across different fault severity levels, resulting in a lack of clear separation that makes direct distinction difficult.

Complementing this,

Figure 14 depicts the frequency spectra of motor current across varying fault severity levels in robot joints.

As observed in the figure, the distinctions in the frequency spectra of the motor current across different fault severity levels are subtle. It remains challenging to directly extract effective fault-discriminative features from these frequency domain data. This limitation underscores the necessity of employing DL methods to uncover underlying discriminative patterns.

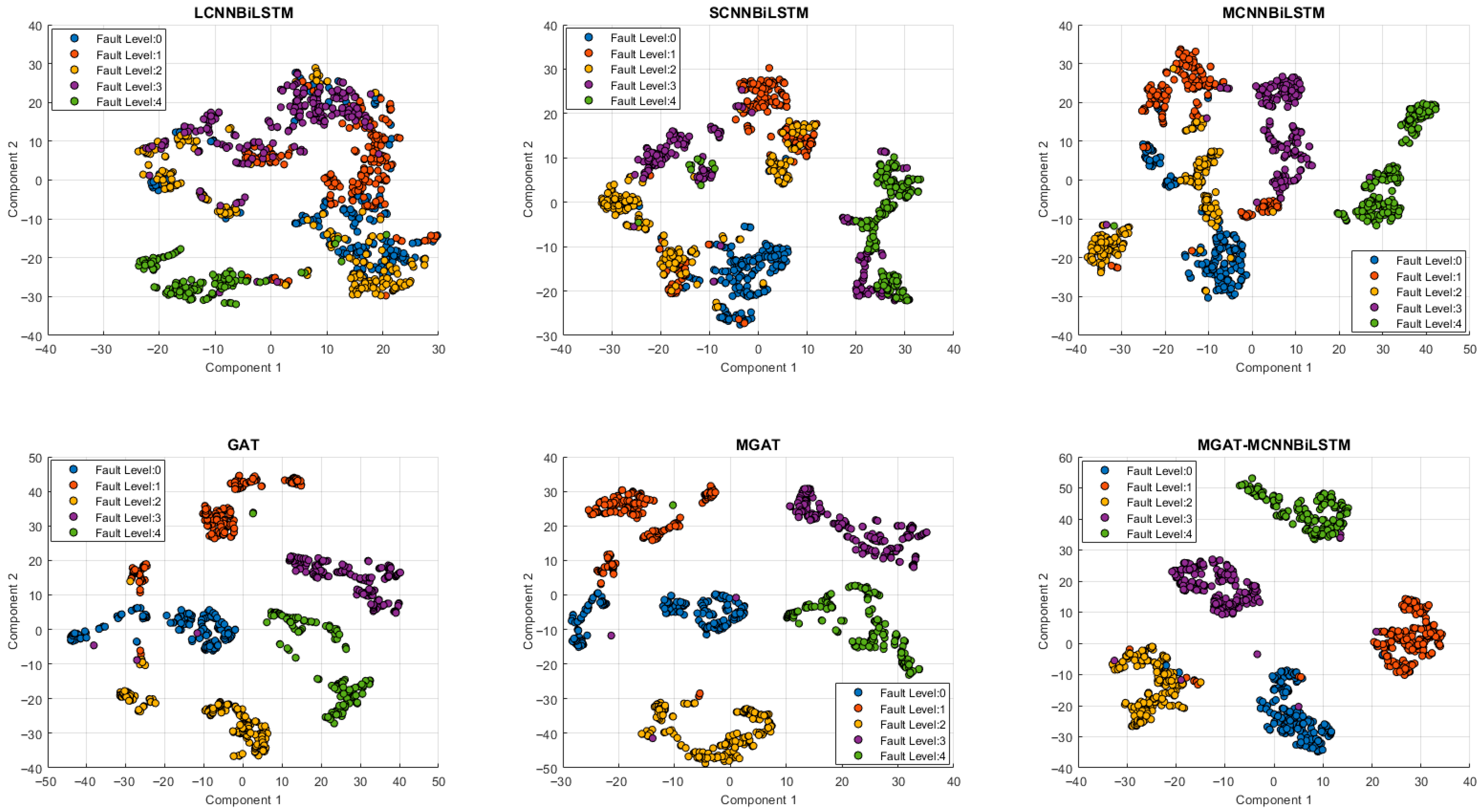

For a comprehensive comparison of different DL-based fault diagnosis methods for IRs, we used t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (T-SNE) to visualize their output features in a two-dimensional feature space, as shown in

Figure 15.

In the dimensionality-reduced feature space, the proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM exhibits considerably cleaner boundaries. The features learned by the hybrid deep learning framework are much more separable, which means the classifier will more easily distinguish between different fault types.

Case 1: Performance Validation of Fault Diagnosis Models with Raw Current-Signal Data (Architectural configuration details are provided in

Table 3. No spectral preprocessing was applied).

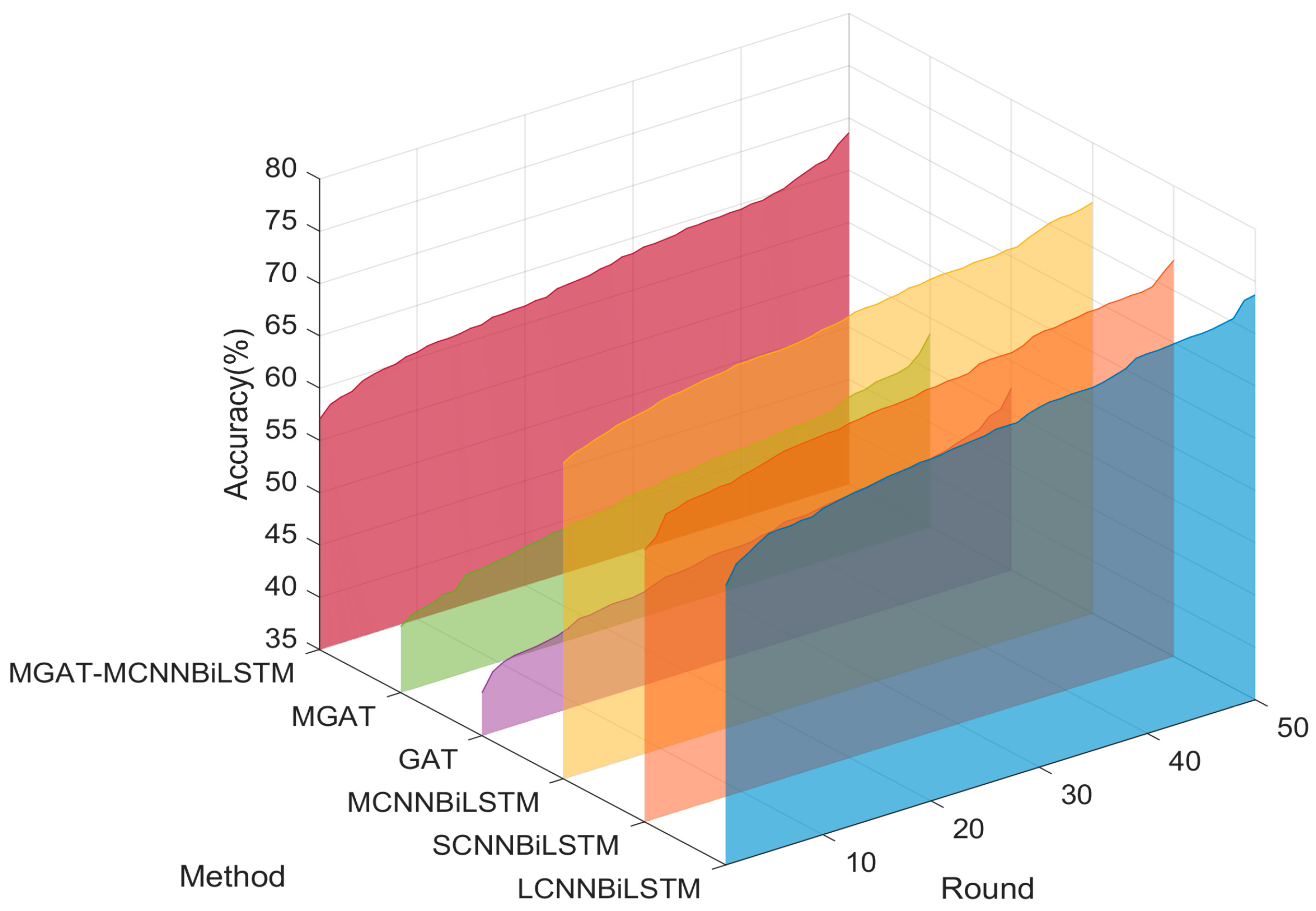

To mitigate the randomness caused by model initialization in diagnostic performance evaluation, fifty independent trials were performed for each method. To visualize the distribution of overall accuracy and highlight performance disparities among the various models, the accuracy results were sorted in ascending order and plotted as a waterfall chart. The corresponding results across all diagnosis models are depicted in

Figure 16.

As illustrated in the waterfall chart, the SNNBiLSTM, LCNNBiLSTM, and MCNNBiLSTM models demonstrate comparatively superior performance under this condition. Specifically, their accuracy exceeds that of the MGA-MCNNBiLSTM model and is significantly higher than the performance achieved by the GAT and MGAT models.

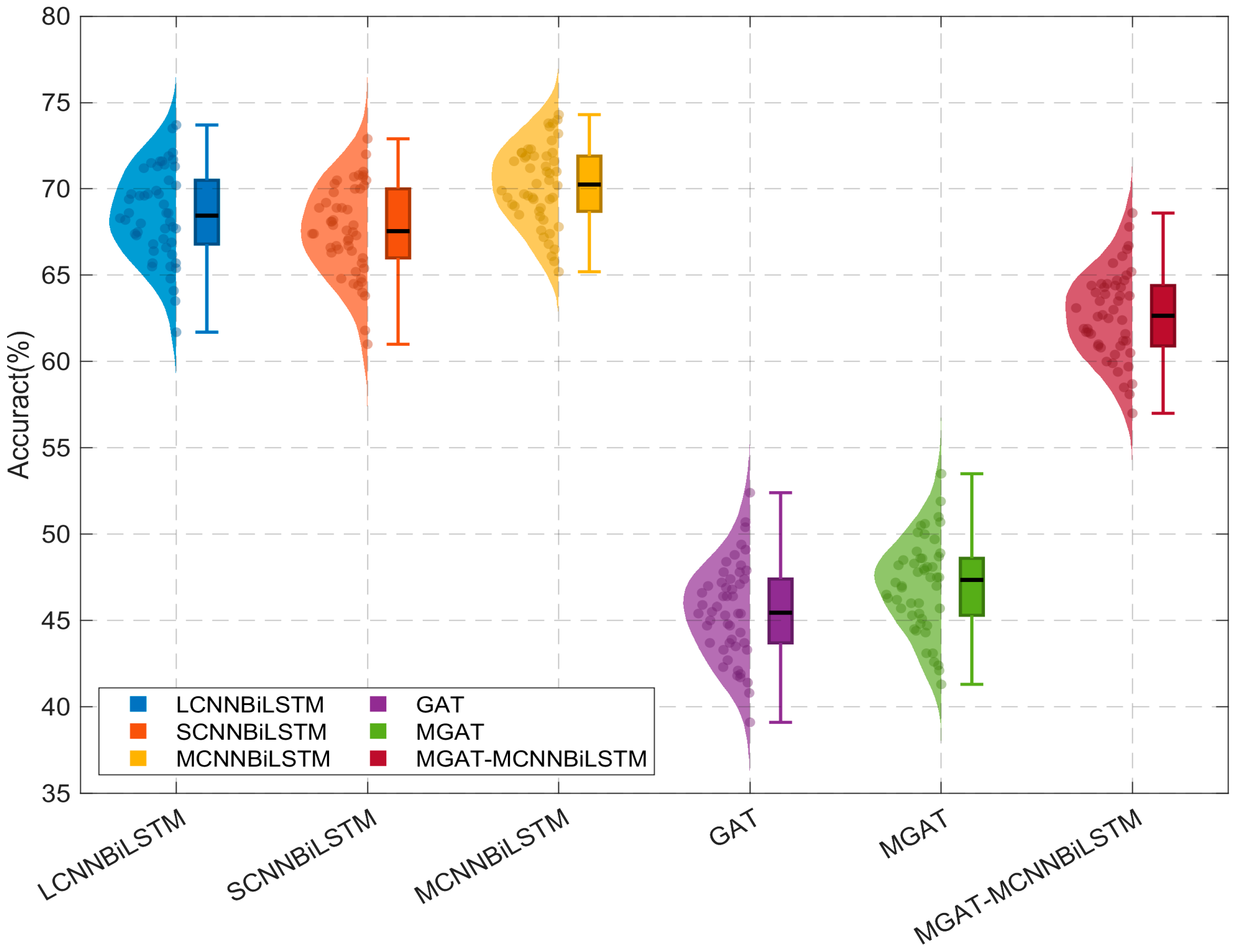

To statistically validate and deepen this performance comparison,

Figure 17 displays the statistical visualizations comparing the performance of different fault diagnosis models for Case 1.

As depicted in

Figure 17, the MCNNBiLSTM model outperforms comparative methods by not only exhibiting the highest median accuracy but also displaying remarkably narrow interquartile ranges. This combination of metrics indicates a consistently superior and highly reliable performance, characterized by minimal variance across the experimental trials.

Table 5 summarizes the comparative performance of six fault diagnosis models in Case 1. Accuracy, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), and

-Score are integral to assessing the performance of each model.

Among the methods evaluated using raw current data without spectral preprocessing, MCNNBiLSTM achieved the highest overall performance, attaining peak metrics of 70.2240 ± 2.3004% accuracy, 71.8084 ± 2.1795% PPV, and 69.7472 ± 2.4187% F1-Score. The LCNNBiLSTM and SCNNBiLSTM models demonstrated moderate efficacy, yielding accuracies of 68.5180 ± 2.6241% and 67.6320 ± 2.5937%, respectively. In contrast, the graph-based approaches, GAT and MGAT, exhibit critically limited diagnostic capability, attaining merely 45.5520 ± 2.7559% and 47.0560 ± 2.6621% accuracy. Significantly, the hybrid MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM architecture, while not surpassing the standalone MCNNBiLSTM, delivered a marked performance improvement over pure graph-based methods (GAT/MGAT), achieving an intermediate Accuracy of 62.6960 ± 2.5217%.

Case 2: Performance Validation of Fault Diagnosis Models with Frequency-transformed Current-Signal Data (Architectural configuration details are provided in

Table 3. Spectral preprocessing was applied).

In Case 2, which features raw signal diagnosis supported by spectral preprocessing, the comparative performance across all fault diagnosis models is illustrated in

Figure 18.

As illustrated in the waterfall chart, the GAT, MGAT, and MGA-MCNNBiLSTM models demonstrate distinct advantages under this condition, outperforming the LCNNBiLSTM, MCNNBiLSTM, and SNNBiLSTM models in terms of accuracy.

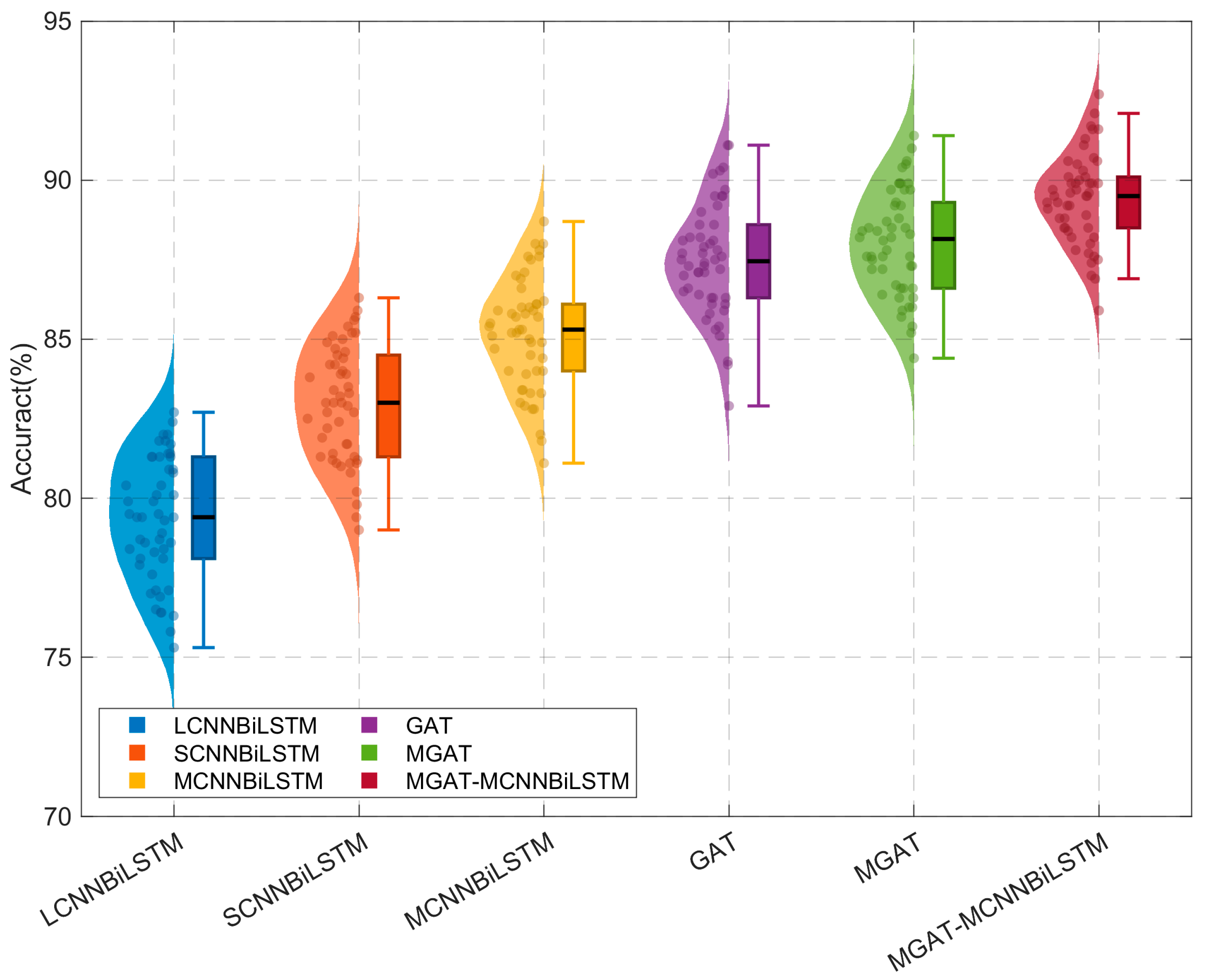

To provide statistical validation for this comparison,

Figure 19 presents performance visualizations across the different fault diagnosis models for the second case study (Case 2).

The box plots in

Figure 19 statistically corroborate the model performance results for Case 2. The MGA-MCNNBiLSTM model distinguishes itself by achieving a median accuracy above 90% while maintaining a compact interquartile range, indicating both high accuracy and excellent robustness. This performance is notably superior to the other models under evaluation.

Table 6 summarizes the comparative performance of six fault diagnosis models in Case 2. Accuracy, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), and

-Score are integral to assessing the performance of each model.

Table 6 quantitatively summarizes the comparative performance of six fault diagnosis models in Case 2. When evaluated on raw current data with spectral preprocessing, the proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM framework demonstrated superior diagnostic capability, achieving peak metrics of 90.7560 ± 1.3311% accuracy, 91.6626 ± 1.1924% PPV, and 90.6736 ± 1.3685% F

1-Score. Among graph-based architectures, both GAT and MGAT delivered competitive results, significantly exceeding all CNNBiLSTM variants. Notably, while MCNNBiLSTM attained 87.8800 ± 1.6407% accuracy, it was surpassed by both LCNNBiLSTM (82.2060 ± 1.8032%) and SCNNBiLSTM (85.9640 ± 1.7009%). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM represents the optimal fault diagnosis framework, achieving a significant 1.51–8.55% absolute improvement in accuracy relative to all benchmark methods.

Figure 20 demonstrates that raw time-series current signals offer limited diagnostic value for deep-learning fault detection, whereas spectral preprocessing substantially enhances model performance.

All models incorporating spectral preprocessing demonstrated statistically superior diagnostic performance compared to non-preprocessed models. Accuracy improvements reached 13.6880%, 18.3320%, and 17.6560% in LCNNBiLSTM, SCNNBiLSTM, and MCNNBiLSTM, respectively. More significant gains are observed in GAT, MGAT, and our proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM, with accuracy increases of 43.2920%, 42.1880%, and 28.0600%, respectively. Similarly, PPV and F1-Score exhibited parallel enhancements.

Case 3: Robustness Assessment Against Signal Degradation via Noise Injection for Emulating Low-Cost, Low-Resolution ADC Scenarios.

To evaluate the noise immunity of different fault diagnosis models, Gaussian white noise was injected into the dataset, establishing an SNR of 40 dB. A comparison of the original and noise-contaminated current signals is presented in

Figure 21.

Following noise injection, a marked degradation in signal quality is observable compared to the original state. This effectively emulates the signal corruption encountered in industrial environments characterized by high electromagnetic interference and low-resolution ADC systems.

For Case 3,

Figure 22 illustrates the comparative noise robustness of all fault diagnosis models.

The waterfall chart indicates that for Case 3, the GAT, MGAT, and MGA-MCNNBiLSTM models demonstrate superior accuracy compared to the LCNNBiLSTM, MCNNBiLSTM, and SNNBiLSTM models. This trend is consistent with the results observed in Case 2.

To statistically validate this comparison,

Figure 23 displays the statistical visualizations comparing the performance of different fault diagnosis models for the third case study (Case 3).

As shown in

Figure 23, the MGA-MCNNBiLSTM model stands out in Case 3 by achieving the highest median accuracy and a compact interquartile range, which together signify superior accuracy and robustness relative to the other models.

Table 7 quantitatively summarizes the comparative performance of six fault diagnosis models in Case 3.

Among the methods evaluated using raw current data with spectral preprocessing, the proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM model achieved superior diagnostic capability, delivering peak metrics of 89.4060 ± 1.4222% accuracy, 90.4124 ± 1.1895% PPV, and 89.2810 ± 1.4853% -Score. Among graph-based approaches, both GAT and MGAT demonstrated competitive results, significantly outperforming all CNNBiLSTM variants. While MCNNBiLSTM attained 85.1820 ± 1.7555% accuracy, it was surpassed by both LCNNBiLSTM (79.3480 ± 1.9455%) and SCNNBiLSTM (82.9900 ± 1.8334%). Significantly, under noise corruption, both GAT variants and the proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM framework exhibited marginal degradation in diagnostic accuracy (1.21–1.37%). In contrast, CNNBiLSTM architectures demonstrated substantially greater performance deterioration (2.70–2.97%), exceeding twice the magnitude of loss observed in graph-enhanced methods. Collectively, these results confirm MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM as the optimal fault diagnosis framework, achieving 1.37–10.26% absolute improvement in accuracy relative to all benchmark methods.

4. Discussion

In Case 1, the experimental results demonstrate that MCNNBiLSTM delivers optimal performance in time-domain applications, while GAT, MGAT, and MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM exhibit suboptimal efficacy under these conditions. This performance gap is primarily attributable to the fundamental limitations of graph-based architectures in time-series fault diagnosis, rooted in an intrinsic incompatibility between graph-structured processing and sequential data physics. These limitations manifest primarily as: (1) Structural incompatibility: Graph-based discretization of continuous time-series compromises critical temporal continuity; and (2) Physics omission: Scale-specific temporal signatures induced by faults remain unmodeled. In contrast, the CNNBiLSTM framework achieves superior performance in time-domain fault diagnosis through its synergistic integration of convolutional and recurrent processing. The CNN component functions as an adaptive local pattern extractor, while the BiLSTM inherently preserves sequential ordering and captures temporal dependencies. This inherently physics-compatible architecture consequently enables robust fault diagnosis.

In Case 2, the results reveal that spectral preprocessing markedly enhances diagnostic performance. Specifically, it fundamentally improves efficacy by decoupling latent signatures, amplifying critical features, and standardizing diagnostic markers, thereby transcending the inherent limitations of time-domain analysis. The core advantages are the following:

- (1)

Intrinsic fault-frequency alignment

Mechanical faults such as bearing degradation, gear tooth breakage, and rotor imbalance induce vibration-modulated sidebands in motor current signals. Conventional time-domain analysis struggles to detect these subtle modulations, as they are often obscured by dominant fundamental components. In contrast, spectral transformation effectively separates constituent frequencies, converting masked sidebands into distinct spectral features and condensing distributed temporal anomalies into localized frequency-domain indicators.

- (2)

Attenuation of non-diagnostic interference

Current signal phase measurements demonstrate marked vulnerability to noise perturbations, particularly those originating from sampling position dependencies. Spectral representations reliably preserve amplitude characteristics, which constitute primary indicators for fault confirmation, while simultaneously attenuating phase sensitivity. This targeted retention of diagnostically robust features enhances accuracy through the elimination of interference-prone signal parameters.

- (3)

Enhanced compatibility with deep learning architectures

Spectrograms spatially localize fault signatures at specific frequency coordinates, enabling clear pattern isolation. Time-domain waveforms, by comparison, often exhibit fault-related anomalies as faint, globally distributed distortions with poor structural definition, complicating feature extraction. Moreover, current amplitudes in the time domain are strongly influenced by load fluctuations, which can overshadow subtle fault-induced changes. Spectral analysis redirects model focus toward structurally stable frequency-domain patterns, aligning with the inherent strength of deep learning in detecting localized, frequency-specific features. This synergy between spectral decomposition and hierarchical learning establishes a highly efficient framework for intelligent fault diagnosis.

In Case 3, noise injection tests were conducted to emulate industrial environments characterized by high electromagnetic interference, as well as to simulate the quantization errors inherent in low-cost, low-resolution ADC systems. Despite significant signal degradation, the proposed framework consistently outperformed all benchmark models under these adversarial conditions. These results empirically confirm the framework’s exceptional robustness against signal contamination and its practicality for deployment in both noise-heavy industrial settings and resource-limited embedded devices. Consequently, this resilience significantly broadens its industrial applicability by lowering hardware precision requirements.

5. Conclusions

This study is motivated by the EBM principle, which prioritizes motor current as the critical bridge between the physics of mechanical faults and measurable electrical signals for IR diagnosis. It advances the theoretical framework of fault diagnosis in IRs by validating the critical necessity of fusing spatiotemporal and structural representations. The research demonstrates that accurate modeling of complex electromechanical systems requires the simultaneous extraction of hierarchical temporal-spectral features and dynamic structural dependencies. By successfully implementing this integration, the proposed MGAT-MCNNBiLSTM architecture provides highly accurate and robust fault diagnosis for IRs. Experimental validation confirms that our model is consistently superior to existing benchmarks, including LCNNBiLSTM, SCNNBiLSTM, MCNNBiLSTM, GAT, and MGAT, and demonstrates significantly enhanced reliability in fault detection across diverse operating conditions. Crucially, this study offers empirical support for evolving EBM theory, transitioning the focus from elementary signal analysis to the modeling of complex system fault diagnosis.

From a practical perspective, this research solidifies motor current analysis as the most viable and economically advantageous sensing modality for industrial deployment. Our approach capitalizes on the existing servo drive infrastructure, thereby eliminating the need for additional expensive sensors and associated retrofitting. Furthermore, the model’s compatibility with legacy, low-resolution data acquisition systems common in installed IRs, as well as its robustness in similar scenarios of data degradation caused by electromagnetic interference, substantially lowers the technical and financial barriers to implementation. Consequently, this synergy of high diagnostic accuracy and reliability, minimal upfront investment, and operational robustness enables a direct transition from costly reactive or scheduled maintenance to more efficient predictive strategies, significantly reducing unplanned downtime and extending IR service life.

The primary limitation of this work concerns the scope of the investigated fault scenarios, as the evaluation primarily focused on mechanical degradation reflected by positioning repeatability errors. In practical industrial applications, IRs are susceptible to a much wider spectrum of anomalies, including electrical component failures, sensor malfunctions, and complex compound faults. Capturing the distinct energy signatures of these varied anomalies is essential to validating the applicability of EBM theory across complex systems. Consequently, addressing this diversity necessitates a significant expansion of the fault knowledge base to ensure comprehensive diagnostic coverage. Therefore, future research will focus on enriching the dataset with diverse fault categories and refining the model architecture to enable the precise identification and classification of a broader range of IR faults.