Abstract

While most patients with degenerative rotator cuff tears respond to conservative treatment, a minority progress to surgery. To anticipate these cases under class imbalance, we propose a sensitivity-constrained evolutionary feature selection framework prioritizing surgical-class recall, benchmarked against traditional methods. Two variants are proposed: (i) a single-objective search maximizing balanced accuracy and (ii) a multi-objective search also minimizing the number of selected features. Both enforce a minimum-sensitivity constraint on the minority class to limit false negatives. The dataset includes 347 patients (66 surgical, 19%) described by 28 clinical, imaging, symptom, and functional variables. We compare against 62 widely adopted pipelines, including oversampling, undersampling, hybrid resampling, cost-sensitive classifiers, and imbalance-aware ensembles. The main metric is balanced accuracy, with surgical-class F1-score as secondary. Pairwise Wilcoxon tests with a win–loss ranking assessed statistical significance. Evolutionary models rank among the top; the multi-objective variant with a Balanced Bagging Classifier performs best, achieving a mean balanced accuracy of 0.741. Selected subsets recurrently include age, tear location/severity, comorbidities, and pain/functional scores, matching clinical expectations. The constraint preserved minority-class recall without discarding or synthesizing data. Sensitivity-constrained evolutionary feature selection thus offers a data-preserving, interpretable solution for pre-surgical decision support, improving balanced performance and supporting safer triage decisions.

1. Introduction

In real-world clinical scenarios, datasets used for predictive modeling frequently exhibit class imbalance, particularly in medicine, where adverse outcomes such as mortality, disease recurrence, or treatment failure occur less frequently than their absence [1]. This imbalance poses significant challenges, as it often leads machine learning (ML) models to become biased toward the majority class, resulting in poor identification of critical but underrepresented cases [2]. Addressing this issue is essential in clinical settings, where the misclassification of minority cases can have severe consequences for patient care.

This study focuses on predicting the need for surgical intervention in patients with rotator cuff tears (RCTs), one of the most common causes of shoulder pain and functional limitation in the adult population [3,4,5]. RCTs are most commonly the result of degenerative processes, with prevalence increasing markedly with age [6,7]. While many patients respond positively to conservative treatment such as physical therapy, analgesics, or corticosteroid injections, a substantial subset experience persistent pain, restricted mobility, and progressive tendon degeneration, ultimately requiring surgical repair [8]. Identifying, as early as possible, those patients who are likely to fail conservative treatment can improve clinical outcomes by preventing tear progression and reducing chronic muscle deterioration [9,10,11,12]. Therefore, developing accurate predictive models to guide treatment decisions is of considerable interest to orthopedic surgeons and rehabilitation specialists.

From a computational perspective, this problem is framed as a binary imbalanced classification task, where the minority class corresponds to patients who will eventually require surgery. In such contexts, the use of standard accuracy metrics can be misleading, as they predominantly reflect the majority class [13]. Instead, the primary metric used is balanced accuracy (BA) [14], which equally weights recall for both classes, providing a fairer evaluation of performance [15].

Several strategies have been proposed to address class imbalance, broadly categorized into data-level techniques (e.g., oversampling, undersampling, hybrid resampling) [16] and algorithm-level techniques (e.g., class weighting, specialized classifiers) [17]. While effective to some extent, these approaches face limitations, such as potential information loss, increased risk of overfitting, and reduced interpretability. Our alternative is the use of feature selection (FS) [18], which seeks to identify the most informative variables, thereby improving model generalization and offering clinicians a clearer understanding of relevant predictors. However, FS becomes challenging in the presence of imbalance, where minority class patterns may be underrepresented in the search process.

To address both imbalance and FS, we explore the combination of specialized classifiers for imbalanced data with evolutionary algorithms (EAs), which are population-based optimization techniques inspired by natural selection. EAs are particularly suitable for FS because they efficiently navigate large and complex search spaces while avoiding local optima. Two main EA paradigms are commonly applied:

- Constrained Single-objective evolutionary algorithms (EA), which optimize a single performance criterion.

- Constrained Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MOEA), which simultaneously optimize multiple conflicting objectives, producing a set of trade-off solutions known as the Pareto front.

In this work, we implement both paradigms. The EA focuses on maximizing BA, while the MOEA jointly optimizes BA and minimizes the number of selected features to balance predictive performance and model simplicity. Clinically, minimizing false negatives—patients incorrectly predicted to improve without surgery—is paramount, as these errors may delay appropriate treatment and lead to further tear progression and deterioration of shoulder function. In contrast, false positives, while undesirable, are comparatively less harmful since they primarily result in closer follow-up or additional diagnostic procedures. This asymmetry highlights the need to prioritize the accurate detection of surgical cases. To address this, our evolutionary algorithms incorporate a clinically driven constraint with a feasibility-first strategy [19,20,21] that enforces a minimum sensitivity threshold for the minority class. By doing so, we ensure that no model achieves high overall performance at the expense of overlooking patients who require surgery, an unacceptable trade-off in a clinical setting [22].

Additionally, we include the F1-score [23] as a complementary metric, given its focus on the positive (minority) class, which corresponds to patients who require surgery. Non-parametric statistical tests are applied to determine whether observed differences between models are statistically significant, providing rigorous validation of our findings.

In summary, our main contributions are as follows:

- We frame the prediction of surgical need in RCTs as an imbalanced classification problem with clinically asymmetric misclassification costs.

- We propose a constrained evolutionary FS framework that prioritizes sensitivity of the minority class and BA while exploring both single- and multi-objective optimization strategies.

- We benchmark our framework against a broad set of imbalance-handling techniques, including data-level, algorithm-level, and hybrid approaches, using multiple classifiers.

- We perform an experimental evaluation with multiple random seeds and statistical testing to ensure the robustness of our conclusions.

- We provide clinical and technical interpretations of the results, demonstrating that our approach achieves superior balance between performance, generalization, and interpretability compared to traditional methods.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work on imbalanced classification, evolutionary FS and ML for RCT prediction. Section 3 describes the dataset, clinical context, and methodology, including our proposed EA/MOEA frameworks. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and performance evaluation and analyzes the results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main findings and discusses future research directions.

2. Related Works

Recent years have seen sustained activity across three intertwined fronts: (i) image-centric pipelines for diagnosis and segmentation (MRI, ultrasound, and radiographs) driven largely by deep learning; (ii) tabular, clinic-driven models for screening and prognosis that rely on resampling, class weighting, or imbalance-aware ensembles; and (iii) FS and metaheuristic optimization, including single- and multi-objective EAs, to improve generalization and interpretability under class imbalance.

The challenge of class imbalance in medical datasets has been extensively studied in recent years due to its adverse impact on the development of reliable predictive models. Salmi et al. [24] provide a review of strategies used in the past decade to address this issue in medical applications, categorizing techniques into preprocessing, algorithmic, and hybrid methods, and highlighting the persistent methodological gaps in handling rare classes within diagnostic contexts. Aubaidan et al. [25] complement this view with a broad overview of ML techniques for intelligent data analysis in healthcare, emphasizing how class imbalance can undermine performance metrics and raise ethical and safety concerns. Along the same lines, Ahsan et al. [26] conducted a systematic review of ML-based heart disease prediction methods, identifying imbalanced data as a barrier to both generalization and interpretability, with many studies prioritizing accuracy over robustness and fairness. In response to these concerns, Nnamoko et al. [27] proposed a selective oversampling method combining SMOTE with outlier detection for improved diabetes prediction, while Vandewiele et al. [28] highlighted the risk of over-optimistic results when oversampling is improperly applied before data partitioning. Together, these works illustrate the pervasiveness of the imbalance problem across diverse clinical domains and the need for methodological design when developing ML pipelines for healthcare.

ML is increasingly being applied to orthopaedics, including tasks such as fracture detection, joint disease classification, and tendon injury assessment [29]. Within this field, RCT diagnosis and prognosis have received growing attention as potential beneficiaries of data-driven approaches. Shinohara et al. [30] proposed several ML classifiers to predict the risk of re-tear after arthroscopic repair, identifying age and imaging findings as key predictors. Similarly, Li et al. [31] developed an explainable ML model to identify relevant features for predicting RCTs in outpatient settings, achieving high accuracy and integrating the best model into a clinical application. Expanding beyond diagnostic screening, Alaiti et al. [32] used preoperative tabular data and multiple ML algorithms to predict failure to achieve clinically meaningful improvement two years after rotator cuff repair; while most models outperformed logistic regression, overall AUCs were moderate and the study did not focus on imbalance-aware learning. Complementing these task-specific efforts, Rodríguez et al. [33] reviewed AI for RCT management, covering imaging-based diagnosis, segmentation, radiograph interpretation, and outcome prediction, highlighting opportunities as well as persistent challenges such as small datasets and heterogeneous clinical definitions.

In the specific context of RCTs under class imbalance, Zhang et al. [34] tackle postoperative re-tear prediction using a cost-sensitive, graph-based approach that embeds imbalance handling directly in the loss. Their method combines a pairwise associative encoder to construct edges with a GCN weight network that learns node- and class-dependent weights, optimizing a weighted logits cross-entropy with logit adjustment and regularization.

Beyond RCT-specific applications, other works investigate domain-specific strategies for addressing imbalance in imaging data. Gao et al. [35] developed a deep learning-based one-class classification method for medical imaging, tackling the challenge of rare event detection using perturbation-based feature extraction. Although the approach targets images rather than tabular data, it underscores the general importance of tailored imbalance strategies in healthcare applications.

In the realm of metaheuristics, evolutionary and swarm-based methods have emerged as promising tools for handling class imbalance, especially when coupled with FS. Namous et al. [36] explore several metaheuristic-based approaches for imbalanced binary classification problems, evaluating how different fitness functions (such as ROC AUC and G-mean) influence the selection of relevant features. They show that conventional accuracy metrics often mislead the optimization process in imbalanced settings.

In the context of FS using multi-objective optimization, Chen et al. [37] propose a method that integrates dominance-based initialization and duplication analysis to improve both convergence and diversity. Their approach transforms feature–label and feature–feature correlations into multi-objective terms, resulting in more robust optimization performance. Rey et al. [38] introduce a hybrid evolutionary algorithm combining filter-based statistics and wrapper methods, tested across 44 imbalanced datasets. Their findings identify the best-suited filter techniques for evolutionary FS and show significant improvements for imbalanced data classification using Nearest Neighbour models.

Several studies have also examined advanced evolutionary paradigms for high-dimensional or large-scale problems. Li et al. [39] propose a dual-population cooperative evolutionary algorithm for many-objective optimization problems, designed for large-scale decision variables, and validate it on both synthetic and real-world tasks. Although not strictly in the medical domain, their approach provides insights into handling complexity in multi-objective search spaces. Saadatmand et al. [40] extend this line of research by introducing JSEMO, a Jaccard-based many-objective FS algorithm specifically tailored for imbalanced data. Their method incorporates set-based variation operators and a double-weighted KNN classifier, significantly improving metrics like BA and G-mean in high-dimensional spaces.

More recently, Ding et al. [41] proposed a multistage multitasking framework for FS in imbalanced datasets, combining SMOTE with swarm intelligence methods. Their approach aims to maximize the F1-score by capturing complex feature interactions and transferring knowledge across optimization tasks. Likewise, Dhinakaran et al. [42] present the SKR-DMKCF framework for medical data, which couples recursive feature elimination with multi-kernel classifiers in a distributed architecture. Their system reduces memory usage and improves scalability without compromising predictive performance.

Wrapper-based evolutionary algorithms, known for their superior accuracy but high computational demands, have also been addressed. Dominico et al. [43] design a multi-objective wrapper FS method that integrates filter-based pre-ranking with Differential Evolution (DE), showing performance gains with fewer features across benchmark datasets. To mitigate the computational burden of wrapper methods, Barradas-Palmeros et al. [44] propose mechanisms like sampling fraction strategies and evaluation caching within a permutation-based DE framework. Their results demonstrate that performance can be preserved while significantly reducing computational time.

Finally, Ghosh et al. [45] address the interaction between FS and class imbalance directly by proposing a binary DE algorithm that incorporates mutual information and a class-aware weighting scheme. Their model outperforms several baselines across multiple metrics including F-measure and G-mean, highlighting the value of combining relevance and fairness in FS.

Conclusions of Related Works

Collectively, these studies underscore the growing importance of EAs and multi-objective optimization in addressing the dual challenges of FS and class imbalance, particularly in complex, high-stakes domains like healthcare. Prior works have proposed various combinations of oversampling techniques, cost-sensitive classifiers, and metaheuristics to improve fairness and robustness, with varying degrees of interpretability. In the RCT-specific literature, recent contributions emphasize image-based pipelines, explainable outpatient diagnosis, or long-term outcome prediction, yet typically do not integrate imbalance-aware, constraint-driven FS as a central mechanism. In contrast, our work (i) encodes a clinical sensitivity requirement for the minority class directly into the optimization objective, ensuring that gains are not achieved at the expense of missed surgical candidates; (ii) preserves the integrity of the original dataset by avoiding artificial sample generation or instance removal, improving performance through subset-based FS coupled with the downstream classifier; and (iii) adopts an evaluation protocol attuned to imbalance, prioritizing BA and F1. These choices yield compact, interpretable models tailored to pre-surgical decision support in RCTs, complementing existing diagnostic and prognostic studies while addressing methodological gaps identified in the literature.

3. Materials and Methods

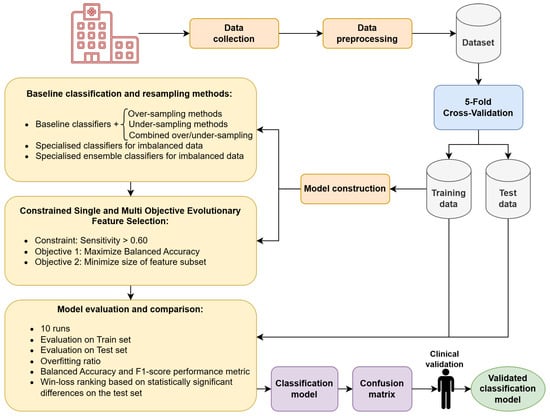

This section presents the dataset and clinical variables used in our study, followed by a description of the methods evaluated. We first introduce the baseline approaches commonly used to address class imbalance, including data-level, algorithm-level, and hybrid strategies. Next, we describe our proposed framework based on constrained EAs for FS, covering both single- and multi-objective optimization variants. Finally, we outline the evaluation protocol and statistical tests employed to compare all methods. The overall workflow of the proposed methodology is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proposed methodology.

3.1. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this study comprises clinical, demographic, and imaging-derived variables from a prospective cohort of 347 patients diagnosed with degenerative supraspinatus RCTs. All patients initially underwent conservative management (e.g., physical therapy, analgesics, corticosteroid injections), with surgery considered only in those failing non-operative treatment. Of the 347 patients, 66 (19%) ultimately required surgical repair, while the remaining 281 (81%) responded successfully to conservative approaches.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements defined tear characteristics. The tear size was measured in millimeters in both the coronal and sagittal views using dedicated software designed for clinical imaging analysis (Carestream Vue PACS, Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY, USA) [46]. Tears were classified based on their size using the ISAKOS classification [47] (C1 < 1 cm, C2 < 2 cm, C3 = 2–4 cm, and C4 = massive tears). In the sagittal plane, the tendon was divided into three sections (anterior, central, posterior), and the tear was recorded in all segments that were affected. Because rotator cuff tears may extend across multiple contiguous regions, one, two, or all three segments may be involved in a given patient. Tears were also categorized as smaller or larger than 20 mm, which would correspond to almost the entire tendon [48]. Fatty infiltration and arthropathy were graded using the MRI Goutallier classification [49,50] and Hamada classification [51] on anteroposterior X-ray. Concomitant subscapularis tears were classified per Lafosse [52], as recommended by ISAKOS. For functional evaluation, patients were assessed objectively using the ASES score [53] and the SSV [54] was used as PROM to measure function pre-treatment. Pain was recorded using the VAS and the presence of night pain. The study adhered to TRIPOD guidelines for prediction model development.

The dataset includes 28 predictive features, grouped as follows:

- Demographics and comorbidities: age, male sex, hand dominance (affected side), manual labor occupation, smoking status, diabetes, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, hypothyroidism, and history of rotator cuff repair on the contralateral shoulder.

- Tear characteristics: tear size measured in anteroposterior (mmAP) and lateral (mmLAT) planes, tear location (anterior, central, posterior thirds), complete tear larger than 20 mm, infraspinatus involvement, subscapularis tear severity (Lafosse > 2), Snyder classification (C1–C3), Goutallier grade for fatty infiltration, and Hamada classification for rotator cuff arthropathy.

- Symptoms and prior treatment: history of corticosteroid injections, presence of night pain, and pain intensity measured via Visual Analog Scale (VAS).

- Functional scores: Subjective Shoulder Value (SSV) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score.

Data were collected between 2021 and 2023 under strict inclusion criteria that excluded patients with traumatic injuries, massive tears (ISAKOS C4), advanced fatty degeneration (Goutallier > 3) or severe arthropathy (Hamada > 3) due to poor surgical prognosis [55,56], thereby ensuring a clinically homogeneous study population.

No missing values were present in the dataset, as patients with incomplete records were excluded. Prior to modeling, a minimal preprocessing stage was applied, where categorical variables were converted into binary indicators when appropriate, and ordinal features such as tear grading or muscle atrophy classifications were encoded while preserving their intrinsic order. Feature scaling was applied exclusively to the training data, and the same transformation parameters were subsequently applied to the corresponding test set, preventing data leakage. A detailed list of input variables is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of input features included in the dataset.

3.2. Baseline Classifiers and Imbalance Handling Methods

To provide a broad comparison framework, we evaluated a wide range of classification algorithms and imbalance-handling strategies implemented in the imbalanced-learn Python package [57]. This library offers a unified interface for both data-level resampling and algorithm-level approaches, as well as specialized ensemble classifiers specifically designed for imbalanced datasets, ensuring reproducibility and standardization of experiments.

The dataset was processed using a stratified 5-fold cross-validation (CV) procedure to maintain the original class distribution in each fold. For each fold, data-level transformations were applied exclusively to the training portion to prevent information leakage, after which the resulting models were evaluated on the corresponding test set. This design allows for an unbiased assessment of each technique’s ability to handle imbalance while preserving the integrity of the evaluation.

Table 2 summarizes all the evaluated techniques, organized into six main categories: (i) baseline classifiers, (ii) data-level oversampling methods, (iii) data-level undersampling methods, (iv) combined hybrid sampling techniques, (v) specialized classifiers for imbalanced datasets, and (vi) specialized ensemble classifiers for imbalanced datasets. By systematically combining resampling strategies with different classifiers, a total of 62 classification pipelines were tested. This included three baseline classifiers with six oversampling methods, eleven undersampling methods and two hybrid methods applied to each baseline classifier, two specialized imbalance-aware classifiers, and four specialized ensemble models.

Table 2.

Classification and resampling methods and their categories.

The three baseline classifiers used were Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Classifier (SVC), and Histogram-based Gradient Boosting (HGB). These represent three commonly used modeling paradigms: tree-based bagging ensembles, margin-based classifiers, and boosting methods, respectively. RF constructs multiple decision trees using bootstrap sampling and aggregates predictions via majority voting, providing strong performance and robustness. SVC finds an optimal separating hyperplane in a high-dimensional space and is particularly effective for complex decision boundaries. HGB leverages gradient boosting with histogram-based binning, enabling faster training and scalability on larger datasets.

To address class imbalance with these baseline classifiers, we applied a diverse set of resampling strategies. Oversampling techniques generate synthetic or replicated samples of the minority class, whereas undersampling methods reduce the number of majority class instances. Hybrid approaches, such as SMOTEENN and SMOTETomek, combine oversampling (e.g., SMOTE) with data cleaning procedures (e.g., Edited Nearest Neighbours or Tomek Links) to simultaneously increase minority representation and remove noisy samples. Each resampling method was evaluated in conjunction with the three baseline classifiers, providing a view of their combined performance. In addition to the classifiers’ standard versions, these classifiers can incorporate internal mechanisms to mitigate imbalance using the class_weight parameter. The option balanced automatically assigns weights inversely proportional to class frequencies.

Beyond individual classifiers, we included ensemble approaches specifically tailored for imbalanced learning. For example, the Balanced Bagging Classifier (BBC) enforces balanced class distributions within each bootstrap sample, while the Balanced Random Forest Classifier (BRF) is a variant of RF, where each tree is trained on a balanced bootstrap subset of the data, combining the benefits of bagging and undersampling. These specialized ensembles are widely recognized for their ability to improve minority class detection without discarding large portions of the dataset.

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.10.0. Data processing and modeling relied on widely used open-source libraries, NumPy 2.1.3, Pandas 2.2.3, and Matplotlib 3.10.0, for numerical computation, data manipulation, and visualization. For ML modeling, we used scikit-learn 1.6.1 and imbalanced-learn 0.13.0, and evolutionary optimization was implemented with pymoo 0.6.1.3.

Experiments were executed on the GACOP cluster (CPU compute node Mendel) with the following configuration: motherboard Supermicro X10DRL-i (SYS-6018R-MTR), dual Intel Xeon E5-2698 v4 processors, 128 GiB DDR4 2400 MHz memory (4 × 32 GiB DIMMs), Intel I210 Gigabit Ethernet, 1 TB HDD (ST1000NM0033-9ZM), and 80 GB Intel SSD (SSDSC2BB08). Multiple evolutionary runs and CV folds were launched in parallel across CPU cores to amortize wall-clock time.

Wall-clock times for optimization and evaluation were recorded using the standard time module, and per-generation/iteration progress was monitored with tqdm progress bars.

3.3. Constrained Evolutionary Algorithms for Feature Selection

To address the problem of imbalanced classification while reducing model complexity, we propose two wrapper-based evolutionary approaches for FS with specialized classifiers for imbalanced data: a single-objective EA and an MOEA. Both algorithms use the BA metric as the primary evaluation criterion and enforce a sensitivity-based constraint to ensure clinical reliability.

The two methods share common evolutionary components: they employ binary vectors to represent subsets of selected features, use a population size of 50 individuals, and run for 1000 generations. Each individual represents a candidate subset of features, encoded as a binary string where a bit value of 1 indicates inclusion of the corresponding feature. Evaluation is conducted using a 5-fold stratified CV to estimate the model’s BA on the training set.

To determine the optimal balance between exploration and exploitation, we performed a grid search over the crossover and mutation probabilities. A search grid with three repetitions was applied, where the crossover probability was explored in the interval and the mutation probability in the interval , with a total of 5000 evaluations. Based on this procedure, the selected crossover probability was set to 0.7, while the mutation probability was set to 0.1.

Crossover operations differ between the two approaches: the EA uses uniform crossover, whereas the MOEA applies two-point crossover. Mutation is performed using the bit-flip operator [81].

Selection in the EA is performed using ranking-based selection with an exponential ranking function, which provides adjustable selection pressure through tunable parameters, while the MOEA handles selection based on non-dominated sorting and crowding distance. Both algorithms enforce a recall-based constraint to ensure clinically acceptable sensitivity for the minority class. Infeasible solutions, those not satisfying the constraint, are penalized.

3.4. Optimization Objective and Sensitivity Constraint

Let be a binary vector representing the selection of n features, where indicates that feature j is included in the model. Each individual is evaluated using 5-fold stratified CV on the training data to ensure robustness and reduce variance.

The primary optimization objective in both the EA and MOEA is to maximize the BA. This metric is particularly well-suited for imbalanced classification problems because it equally considers the performance of both classes, mitigating the bias toward the majority class. BA is defined as

where (true positives) refers to correctly predicted surgical cases, (false negatives) to surgical cases incorrectly predicted as non-surgical, (true negatives) to correctly predicted non-surgical cases, and (false positives) to non-surgical cases incorrectly predicted as requiring surgery.

During preliminary experiments, we evaluated alternative metrics such as specificity (recall of the majority class) and sensitivity (recall of the minority class). However, these measures in isolation proved inadequate for guiding the optimization process.

In highly imbalanced datasets, a model could achieve perfect sensitivity by simply predicting every instance as belonging to the minority class, or perfect specificity by predicting exclusively the majority class. Although these extreme cases would yield high values for one metric, they would perform poorly overall and would not represent clinically useful solutions.

By combining both sensitivity and specificity, BA addresses this issue, penalizing models that overfit to a single class and rewarding those that achieve balanced performance. This makes BA a more robust measure of classifier quality, particularly when both classes have clinical importance.

3.4.1. Sensitivity Constraint

Consider the following example with two hypothetical models:

- Model A: BA = 0.775. Specificity = 0.95. Sensitivity = 0.60.

- Model B: BA = 0.775. Specificity = 0.80. Sensitivity = 0.75.

Although both models achieve identical BA scores, Model B provides higher recall for the minority class (patients requiring surgery), resulting in fewer false negatives. In clinical practice, failing to identify patients who need surgery may delay treatment and worsen prognosis. Conversely, false positives, while undesirable, mainly lead to additional follow-up or diagnostic testing, which are comparatively less harmful.

This asymmetry highlights the need to explicitly control sensitivity to ensure that solutions are not only balanced but also clinically meaningful.

To guarantee a minimum level of detection for the minority class, we impose a sensitivity constraint during the optimization process. Only solutions that meet this minimum recall threshold are considered feasible. This ensures that the evolutionary search does not converge toward models that, while achieving high BA, neglect to correctly identify surgical cases.

Formally, the constraint is expressed as

where 0.6 was chosen based on a preliminary analysis in which several candidate sensitivity thresholds were empirically evaluated through exploratory evolutionary runs. Values below this level resulted in clinically unacceptable false-negative rates, whereas more restrictive thresholds markedly reduced the feasible search space and hindered optimization. The selected threshold was also reviewed and validated by our collaborating orthopedic surgeons, confirming its suitability as a clinically meaningful lower bound.

The feasibility function used during optimization is defined as

A feasibility-first strategy is adopted to handle this constraint, meaning that the selection mechanism prioritizes feasible solutions and compares fitness values only among them. Infeasible solutions are penalized but remain in the population to encourage exploration near the boundary of feasibility.

In addition to BA, we also monitor the F1-score during evaluation. In this work we use the standard binary F1-score, as commonly defined in the ML literature for binary problems, which corresponds to the harmonic mean of precision and recall computed with respect to the positive class. Since the surgical class is treated as the positive (minority) class in our formulation, the F1-score naturally reflects the trade-off between correctly identifying surgical cases (high recall) and avoiding unnecessary interventions (high precision). Formally, the F1-score is defined as

where

This metric provides a complementary perspective to BA by offering a minority-class-focused measure that is widely used and well understood. While BA serves as the optimization objective in the evolutionary algorithms, the F1-score is reported during the analysis phase to better characterize the balance between sensitivity and precision across competing models.

To assess whether the observed performance differences between models were statistically meaningful, we perform pairwise comparisons using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [82]. This non-parametric test is particularly appropriate for evaluating two related samples when no assumption of normality can be made regarding their performance differences. From the test results, we derived a win–loss ranking by counting the number of statistically significant pairwise victories (wins) and defeats (losses) for each model when compared against the others. This ranking provides a clear summary of the comparative performance of all approaches.

3.4.2. Single-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm

The EA minimizes the negative BA:

subject to the feasibility constraint defined above. The fitness transformation is

This structure encourages infeasible solutions to evolve toward feasibility, while driving feasible ones toward optimality. Selection is based on exponential ranking and elitism is applied to retain top individuals across generations.

3.4.3. Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm

The proposed MOEA is implemented using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) scheme [83] from the pymoo framework [84], and is designed to optimize two conflicting objectives:

subject to:

Each individual is evaluated to obtain a pair of objective values and a constraint violation score. Only individuals satisfying the recall threshold are considered feasible and eligible for Pareto ranking. The final output is a Pareto front of feasible, non-dominated solutions, enabling trade-offs between model interpretability and predictive performance.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

This section presents an experimental evaluation of the proposed evolutionary feature selection frameworks, comparing our proposal against traditional data-level and model-level imbalance handling strategies. All methods were trained and evaluated following the setup described in Section 3, using the same dataset, partitions, and evaluation metrics to ensure a fair comparison.

Our analysis begins with a statistical comparison of models using non-parametric tests to determine whether observed performance differences are statistically significant, with a win–loss ranking to provide an overall performance hierarchy across all evaluated techniques. Following this, we examine the generalization capabilities of the top-performing models through the analysis of the overfitting ratio, comparing training and test performance. Finally, we interpret the clinical and technical implications of these results, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each approach.

4.1. Statistical Test Results

Table 3 presents the win–loss ranking for all evaluated methods, based on statistically significant differences observed on the test set.

Table 3.

Win–loss ranking for the BA metric based on statistically significant differences on the test set.

These results demonstrate the superiority of our proposed evolutionary approaches. The MOEA combined with BBC achieves the highest overall score, with 69 wins and no losses. Similarly, MOEA and single-objective EA with SVC using balanced class weighting occupy the next top positions, highlighting the effectiveness of incorporating FS within an evolutionary optimization framework to address severe class imbalance.

In contrast, traditional resampling methods combined with standard classifiers tend to perform worse, appearing mostly in the middle or lower parts of the ranking. Undersampling methods, such as RUS or IHT, can occasionally achieve competitive performance and even rank within the top ten models. However, these approaches achieve class balance by removing a substantial number of majority class samples, which can severely reduce the amount of available training data. In real-world medical datasets, where data collection is often expensive, time-consuming, and subject to strict privacy regulations, this reduction in sample size can be particularly problematic. Eliminating potentially informative instances may lead to a loss of clinically relevant patterns, ultimately limiting the model’s ability to generalize to future patient populations.

Oversampling techniques, such as SMOTE or Borderline-SMOTE, take the opposite approach by generating synthetic minority class samples to increase their representation. While this avoids the problem of discarding real patient data, it introduces artificially generated instances that may not fully capture the complex variability of real-world medical cases. As shown in Table 3, these methods tend to perform poorly, ranking near the bottom. This suggests that simply augmenting the minority class with synthetic data is insufficient for handling the complexity of this prediction task, particularly when the relationships between variables are highly non-linear and clinically nuanced.

Our evolutionary FS framework offers a distinct advantage over both resampling paradigms. By directly optimizing the selection of the most informative features, our approach achieves superior performance without altering the original dataset. Unlike undersampling, it does not discard valuable clinical information, and unlike oversampling, it does not introduce potentially unreliable synthetic data. This makes it especially suitable for medical applications, where maintaining the integrity of the dataset is crucial and where the interpretability of selected features can provide additional insights for clinicians.

To further examine the generalization capabilities of the models, we analyzed the overfitting ratio (OR), which measures the relative difference between training and test performance. Lower values indicate a smaller gap between training and test BA, suggesting better generalization and reduced risk of overfitting.

For this analysis, we selected three representative models from each category:

- Our three best-performing evolutionary approaches (EA/MOEA).

- Three strong models based on traditional undersampling techniques.

- Two specialized classifiers designed for imbalanced datasets, without FS.

Table 4 summarizes the mean and standard deviation of the BA for both training and test sets, along with the resulting OR for each model. The evolutionary methods exhibit a favorable balance, achieving competitive test performance with moderate OR values, indicating that they are not overfitting to the training data. In contrast, some specialized ensemble methods, such as BRF, display very high training accuracy but substantially lower test accuracy, leading to the highest OR values. This pattern highlights a tendency to overfit, which can limit their practical utility in real-world clinical settings.

Table 4.

Mean BA and OR for selected models. Lower OR indicates better generalization.

The table shows that evolutionary models achieve a balance between high test performance and controlled overfitting, confirming their suitability for complex imbalanced classification tasks in clinical applications. On the other hand, models like BRF and BBC, although strong on training data, exhibit signs of overfitting, which can hinder their reliability when applied to unseen patient cases.

In addition to the analysis of the BA metric, we also evaluate the performance of all models using the F1-score, a metric particularly relevant in our clinical context since it focuses on the minority class, which represents patients requiring surgery. This metric is useful to assess how well the algorithms identify true surgical cases without excessively misclassifying non-surgical patients.

Table 5 presents the win–loss ranking for the F1-score. Similar to the BA analysis, each comparison between models is performed on the test set results across multiple runs, and statistically significant differences are recorded as wins or losses.

Table 5.

Win–loss ranking for the F1-score metric based on statistically significant differences on the test set.

The F1-score results reinforce the conclusions drawn from the BA analysis. The top positions are consistently occupied by our proposed evolutionary approaches. These findings confirm that incorporating FS within an evolutionary optimization framework is highly effective for improving the identification of surgical cases.

4.2. Computational Cost and Execution Times

Evolutionary algorithms are inherently computationally intensive due to their iterative nature and the need to evaluate a population of candidate solutions across multiple generations. In our case, each individual corresponds to a subset of features, which must be trained and validated using 5-fold stratified CV.

To keep wall-clock time manageable, we executed runs in parallel on a multi-core node of our HPC cluster; wall times were recorded with the time module and per-generation progress monitored with tqdm. Table 6 reports times for each classifier for a single execution under the single-objective EA (top) and the MOEA (bottom).

Table 6.

Execution times by classifier for a single execution.

In the full experimental protocol, in order to perform statistical tests, we executed 10 runs per fold and 5 folds, i.e., 50 executions per classifier. Aggregating across classifiers, the end-to-end wall-clock time to complete all experiments on our cluster was under 67 h. These figures illustrate the expected trade-off: while evolutionary optimization incurs a higher computational cost than conventional baselines, it produces compact subsets and consistent gains in BA and F1 in a high-stakes clinical setting, justifying the one-time training investment prior to deployment.

4.3. Subset-Based FS and Clinical Relevance

A central advantage of our pipeline is the explicit search over subsets of variables rather than relying solely on attribute rankings. Ranking-based tools (e.g., permutation importance, SHAP) are valuable for interpretation, but they typically assess variables in isolation or under a fixed model and can miss interactions, conditional effects, and redundancies that emerge only when features are considered jointly. By treating the predictor as a wrapper and optimizing the variable set with respect to the downstream classifier’s empirical behavior, subset-based FS can (i) capture synergistic patterns among moderately informative variables, (ii) remove redundant or collinear attributes, and (iii) align the selected subset with the task objective and the sensitivity constraint used during training. This is particularly relevant in medical datasets that are often imbalanced, may contain relatively few instances, and include many attributes drawn from heterogeneous measurements (clinical scales, imaging, laboratory analyses).

4.4. Analysis of the Top-Performing Models and Results Interpretation

Across the win–loss analyses based on BA and the complementary results for F1, the best overall configuration is the MOEA paired with BBC. Close contenders are the balanced SVC with both EA and MOEA, reinforcing that embedding FS within an evolutionary wrapper that optimizes BA under a clinically motivated sensitivity constraint yields consistent advantages in imbalanced settings. These results are achieved without altering the original data distribution (no over-/under-sampling at the data level), which is desirable in medical cohorts where sample sizes are modest and the minority class is scarce. Averaged across the five folds, our MOEA BBC achieves a BA of 0.741, computed by averaging the best execution from each of the five folds.

Comparative results highlight the limitations of pure undersampling methods (e.g., RUS, NearMiss): although they can occasionally perform well, they discard a large fraction of majority-class instances, which is problematic in real-world medical datasets where the total number of patients is limited and the minority class is small. Conversely, over-sampling approaches (e.g., SMOTE variants) avoid data loss but may inject synthetic borderline or noisy samples that do not translate into sustained gains in BA or F1 in our task. By avoiding any manipulation of the data distribution and instead optimizing a clinically guided objective, the MOEA/EA + FS strategy attains top-tier performance while maintaining the integrity of the original dataset.

Importantly, MOEA consistently outperforms EA across classifiers. Because the second MOEA objective explicitly promotes smaller feature subsets, this pattern suggests that the dataset contains redundant or weakly informative variables. MOEA’s explicit drive toward compact subsets likely removes redundancy beyond what EA achieves, improving generalization while maintaining the sensitivity constraint.

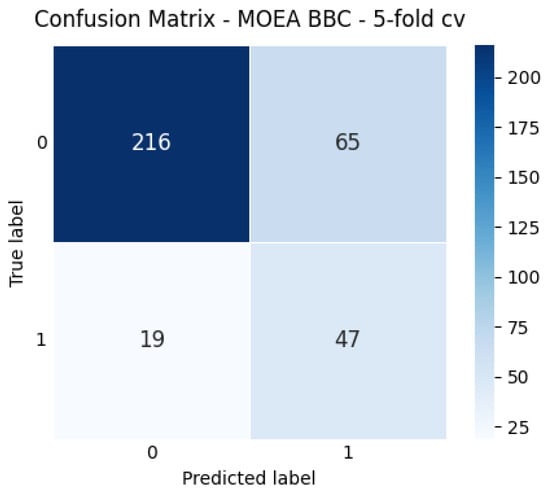

To illustrate the learned operating point, Figure 2 reports the aggregated confusion matrix for MOEA BBC over the 5-fold CV. The model correctly identifies most Surgery cases (minority class), consistent with the sensitivity constraint. As expected, this comes with a moderate increase in false positives; however, in our clinical context this trade-off is acceptable. Patients incorrectly flagged as surgical candidates are not directed to immediate surgery; rather, they undergo closer follow-up, additional imaging, or more detailed functional assessment. These steps form part of the standard diagnostic workflow and do not impose a substantial additional burden on clinical personnel, as all patients already undergo routine orthopedic and rehabilitation evaluations. Importantly, surgical referral rates in rotator cuff care are relatively low, and the incremental workload generated by false positives is substantially smaller than the clinical cost of missing true surgical cases. Therefore, the proposed model supports decision-making without exceeding realistic evaluation capacity while helping prioritize patients who may benefit from earlier surgical assessment.

Figure 2.

Aggregated confusion matrix for MOEA_BBC over 5-fold CV.

The features most often selected across folds and runs are consistent with clinical expectations: Age; Snyder classification; Tear size; Tear location (anterior third); Infraspinatus involvement; comorbidities (Diabetes, Dyslipidemia, High blood pressure, Hypothyroidism); Night pain; and functional scores (SSV, ASES).

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This work presents a novel FS framework based on EAs with clinically driven constraints, aimed at addressing the challenges of imbalanced classification in healthcare applications. Our case study focused on predicting the need for surgical intervention in patients with RCTs, where early and accurate identification of individuals likely to require surgery is essential. Detecting these patients in advance allows clinicians to initiate timely interventions, prevent further tear progression, and ultimately improve patient outcomes while optimizing healthcare resource allocation.

The results demonstrate that the proposed methodology consistently outperforms traditional approaches such as data-level methods (oversampling, undersampling, and hybrid techniques) and algorithm-level strategies (class weighting and specialized classifiers). By integrating FS into the optimization process, our framework generates more interpretable models.

A key strength of our approach is that it operates directly on the original dataset without the need to modify its distribution through artificial data generation or by discarding potentially useful cases. Unlike undersampling, which removes data and may be problematic when working with small real-world datasets, or oversampling, which introduces synthetic information, our proposal preserves data integrity while focusing on identifying the most informative predictors for accurate classification. Furthermore, the incorporation of a sensitivity constraint ensures that the minority class (patients who require surgery) is not neglected, addressing the asymmetric clinical cost of misclassification.

Despite these advantages, evolutionary algorithms inherently involve a higher computational cost, as they require the evaluation of many candidate solutions across multiple generations. However, this cost is primarily incurred during the model optimization stage. Once the best solution is identified, the resulting model can be deployed efficiently for real-time predictions in clinical practice.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of this work. Although the dataset includes a diverse set of clinical variables, its overall size is relatively limited, underscoring the need for external and multicentric validation to ensure that the proposed models generalize well across different populations and healthcare settings.

Future directions include incorporating explainable machine learning techniques such as SHAP to enhance model transparency and support clinical decision-making. The combination of constrained optimization and explainability could lead to more trustworthy and clinically actionable AI systems. Additionally, exploring domain-specific or multiple clinical constraints (e.g., age- or risk-based thresholds) could further tailor the optimization process to practical clinical scenarios. As a complementary line, we intend to investigate strategies to accelerate evolutionary optimization, such as parallel evaluation, surrogate-assisted fitness approximation, and multi-fidelity/early-stopping schemes, so as to reduce runtime while preserving the quality of the selected feature subsets.

In conclusion, our work shows that combining FS with clinically informed constraints within an evolutionary optimization framework is a promising strategy for tackling imbalanced classification problems in medicine. This approach not only improves predictive performance but also produces interpretable and clinically relevant models, providing a strong foundation for future decision support systems in healthcare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.B., F.J., G.S., S.G., N.M.-C., E.C., G.B. and J.M.G.; methodology, J.M.B., F.J. and J.M.G.; software, J.M.B., F.J. and G.S.; validation, F.J., S.G., N.M.-C. and E.C.; formal analysis, F.J., G.S., N.M.-C. and E.C.; investigation, J.M.B., F.J., G.S., G.B. and J.M.G.; resources, S.G., N.M.-C. and E.C.; data curation, J.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.B.; writing—review and editing, F.J., G.S., S.G., N.M.-C., E.C., G.B. and J.M.G.; supervision, F.J., G.S., S.G., N.M.-C., E.C., G.B. and J.M.G.; project administration, F.J., G.B. and J.M.G.; funding acquisition, G.B. and J.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially funded by Grant TED2021-129221B-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article may be provided by the authors, where appropriate, upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADASYN | Adaptive Synthetic Sampling |

| AllKNN | All K-Nearest Neighbours |

| ASES | American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons |

| BA | Balanced Accuracy |

| BBC | Balanced Bagging Classifier |

| BRF | Balanced Random Forest |

| CC | Cluster Centroids |

| CNN | Condensed Nearest Neighbour |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| EA | Evolutionary Algorithm |

| ENN | Edited Nearest Neighbours |

| FS | Feature Selection |

| HGB | Histogram-based Gradient Boosting |

| IHT | Instance Hardness Threshold |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MOEA | Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NCR | Neighbourhood Cleaning Rule |

| NSGA | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm |

| OSS | One-Sided Selection |

| OR | Overfitting Ratio |

| RCT | Rotator Cuff Tear |

| RENN | Repeated Edited Nearest Neighbours |

| RF | Random Forest |

| ROS | Random Oversampling |

| RUS | Random Undersampling |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SMOTEENN | SMOTE + Edited Nearest Neighbour |

| SVC | Support Vector Classifier |

| SSV | Subjective Shoulder Value |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Banik, D.; Bhattacharjee, D. Mitigating data imbalance issues in medical image analysis. In Research Anthology on Improving Medical Imaging Techniques for Analysis and Intervention; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1215–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarouci, S.; Chikh, M.A. Medical imbalanced data classification. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2017, 2, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, D.; Yamamoto, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Osawa, T.; Shitara, H.; Ichinose, T.; Takasawa, E.; Takagishi, K. The effects of rotator cuff tears, including shoulders without pain, on activities of daily living in the general population. J. Orthop. Sci. 2012, 17, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener, J.D.; Aleem, A.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Sefko, J.; Steger-May, K. Factors associated with choice for surgery in newly symptomatic degenerative rotator cuff tears: A prospective cohort evaluation. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindisino, F.; Salomon, M.; Giagio, S.; Pastore, C.; Innocenti, T. Rotator cuff repair vs. nonoperative treatment: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2021, 30, 2648–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, W.; Lee, S.; Hoon Kim, S. The natural course of and risk factors for tear progression in conservatively treated full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, T.E.; Werner, B.C. Surgery and Rotator Cuff Disease: A Review of the Natural History, Indications, and Outcomes of Nonoperative and Operative Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tears. Clin. Sport. Med. 2023, 42, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Green, S.; McBain, B.; Surace, S.J.; Deitch, J.; Lyttle, N.; Mrocki, M.A.; Buchbinder, R. Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, H.C.; Norlin, R.; Johansson, K.; Adolfsson, L.E. The influence of age, delay of repair, and tendon involvement in acute rotator cuff tears. Acta Orthop. 2011, 82, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.G.; Dugas, J.R.; Andrews, J.R.; Goldstein, S.R.; Emblom, B.A.; Cain, E.L., Jr. Rotator Cuff Repair in Adolescent Athletes. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2018, 46, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemitsch, C.; Chahal, J.; Vicente, M.; Nowak, L.; Flurin, P.H.; Lambers Heerspink, F.; Henry, P.; Nauth, A. Surgical repair versus conservative treatment and subacromial decompression for the treatment of rotator cuff tears. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101-B, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetia, R.; Handoko, H.K.; Rosa, W.Y.; Ismiarto, A.F.; Petrasama; Utoyo, G.A. Primary traumatic shoulder dislocation associated with rotator cuff tear in the elderly. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 95, 107200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thölke, P.; Mantilla-Ramos, Y.J.; Abdelhedi, H.; Maschke, C.; Dehgan, A.; Harel, Y.; Kemtur, A.; Mekki Berrada, L.; Sahraoui, M.; Young, T.; et al. Class imbalance should not throw you off balance: Choosing the right classifiers and performance metrics for brain decoding with imbalanced data. NeuroImage 2023, 277, 120253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodersen, K.H.; Ong, C.S.; Stephan, K.E.; Buhmann, J.M. The Balanced Accuracy and Its Posterior Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, 23–26 August 2010; pp. 3121–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V. Data Mining for Imbalanced Datasets: An Overview. In Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery Handbook; Maimon, O., Rokach, L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamilla, M.Y.; Al-Haddad, R.; Chowdhury, S. Resampling Imbalanced Healthcare Data for Predictive Modelling. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.L.; Leong, T.Y. A Model Driven Approach to Imbalanced Data Sampling in Medical Decision Making. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2010, 160, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolón-Canedo, V.; Sánchez-Maroño, N.; Alonso-Betanzos, A. Feature selection for high-dimensional data. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2016, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, F.; Verdegay, J.L. Evolutionary techniques for constrained optimization problems. In Proceedings of the 7th European Congress on Intelligent Techniques and Soft Computing (EUFIT’99), Aachen, Germany, 13–16 September 1999; pp. 504–512. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, F.; Verdegay, J.L.; Gómez-Skarmeta, A.F. Evolutionary techniques for constrained multiobjective optimization problems. In Workshop on Multi-Criterion Optimization Using Evolutionary Methods GECCO-1999; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Coello Coello, C.A. Theoretical and numerical constraint-handling techniques used with evolutionary algorithms: A survey of the state of the art. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2002, 191, 1245–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, K.; Georgiou, S.; Koukouvinos, C.; Stylianou, S. Support Vector Machines Classification on Class Imbalanced Data: A Case Study with Real Medical Data. J. Data Sci. 2022, 12, 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.; Atif, D.; Oliva, D.; Abraham, A.; Ventura, S. Handling imbalanced medical datasets: Review of a decade of research. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubaidan, B.H.; Kadir, R.A.; Lajb, M.T.; Anwar, M.; Qureshi, K.N.; Taha, B.A.; Ghafoor, K. A review of intelligent data analysis: Machine learning approaches for addressing class imbalance in healthcare - challenges and perspectives. Intell. Data Anal. 2025, 29, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Machine learning-based heart disease diagnosis: A systematic literature review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2022, 128, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnamoko, N.; Korkontzelos, I. Efficient treatment of outliers and class imbalance for diabetes prediction. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 104, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewiele, G.; Dehaene, I.; Kovács, G.; Sterckx, L.; Janssens, O.; Ongenae, F.; De Backere, F.; De Turck, F.; Roelens, K.; Decruyenaere, J.; et al. Overly optimistic prediction results on imbalanced data: A case study of flaws and benefits when applying over-sampling. Artif. Intell. Med. 2021, 111, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzubaidi, L.; AL-Dulaimi, K.; Salhi, A.; Alammar, Z.; Fadhel, M.A.; Albahri, A.; Alamoodi, A.; Albahri, O.; Hasan, A.F.; Bai, J.; et al. Comprehensive review of deep learning in orthopaedics: Applications, challenges, trustworthiness, and fusion. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 155, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, I.; Mifune, Y.; Inui, A.; Nishimoto, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kato, T.; Furukawa, T.; Tanaka, S.; Kusunose, M.; Hoshino, Y.; et al. Re-tear after arthroscopic rotator cuff tear surgery: Risk analysis using machine learning. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2024, 33, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Alike, Y.; Hou, J.; Long, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Meng, K.; Yang, R. Machine learning model successfully identifies important clinical features for predicting outpatients with rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg. Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiti, R.K.; Vallio, C.S.; Assunção, J.H.; de Andrade e Silva, F.B.; Gracitelli, M.E.C.; Neto, A.A.F.; Malavolta, E.A. Using Machine Learning to Predict Nonachievement of Clinically Significant Outcomes After Rotator Cuff Repair. Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231206180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, H.C.; Rust, B.; Hansen, P.Y.; Maffulli, N.; Gupta, M.; Potty, A.G.; Gupta, A. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Rotator Cuff Tears. Sport. Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2023, 31, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Dong, Y. Predicting Postoperative Re-Tear of Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Using Artificial Intelligence on Imbalanced Data. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 24487–24497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Wu, S. Handling imbalanced medical image data: A deep-learning-based one-class classification approach. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 108, 101935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namous, F.; Faris, H.; Heidari, A.A.; Khalafat, M.; Alkhawaldeh, R.S.; Ghatasheh, N. Evolutionary and Swarm-Based Feature Selection for Imbalanced Data Classification. In Evolutionary Machine Learning Techniques: Algorithms and Applications; Mirjalili, S., Faris, H., Aljarah, I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yao, X.; Gong, D.; Tu, H. A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for feature selection incorporating dominance-based initialization and duplication analysis. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 95, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, C.C.T.; García, V.S.; Villuendas-Rey, Y. Evolutionary feature selection for imbalanced data. In Proceedings of the 2023 Mexican International Conference on Computer Science (ENC), Guanajuato, Mexico, 11–13 September 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, S.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, G.; Ding, W. Research on Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms Based on Large-Scale Decision Variable Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatmand, H.; Akbarzadeh-T, M.R. Many-Objective Jaccard-Based Evolutionary Feature Selection for High-Dimensional Imbalanced Data Classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 8820–8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Yao, H.; Huang, J.; Hou, T.; Geng, Y. Evolutionary multistage multitasking method for feature selection in imbalanced data. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 92, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhinakaran, D.; Srinivasan, L.; Edwin Raja, S.; Valarmathi, K.; Gomathy Nayagam, M. Synergistic feature selection and distributed classification framework for high-dimensional medical data analysis. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominico, G.; Bernardes, J.S.; Dorneles, L.L.; Dorn, M. Multi-Objective Wrapper Differential Evolution with Guided Initial Population for Feature Selection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Chicago, IL, USA, 1–5 July 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas-Palmeros, J.A.; Mezura-Montes, E.; Rivera-López, R.; Acosta-Mesa, H.G. Computational Cost Reduction in Wrapper Approaches for Feature Selection: A Case of Study Using Permutational-Based Differential Evolution. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M. Binary Differential Evolution based Feature Selection Method with Mutual Information for Imbalanced Classification Problems. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Krakow, Poland, 28 June–1 July 2021; pp. 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.T. Comparison of mediolateral (V-shaped) vs. anteroposterior dominant rotator cuff tears: The anteroposterior tear width contributes more to postoperative retears than mediolateral length when the tear size area is similar. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2025, 34, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, E.; Rebollón, C.; Itoi, E.; Imhoff, A.; Savoie, F.H.; Arce, G. Reliable interobserver and intraobserver agreement of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification system of rotator cuff tears. J. ISAKOS 2022, 7, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, L.; Atinga, A.; White, L.; Henry, P.; Probyn, L. Rotator Cuff Injury and Repair. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2022, 26, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutallier, D.; Postel, J.M.; Bernageau, J.; Lavau, L.; Voisin, M.C. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures. Pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1994, 304, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, B.; Weishaupt, D.; Zanetti, M.; Hodler, J.; Gerber, C. Fatty degeneration of the muscles of the rotator cuff: Assessment by computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 1999, 8, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Yamanaka, K.; Uchiyama, Y.; Mikasa, T.; Mikasa, M. A Radiographic Classification of Massive Rotator Cuff Tear Arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafosse, L.; Lanz, U.; Saintmard, B.; Campens, C. Arthroscopic repair of subscapularis tear: Surgical technique and results. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2010, 96, S99–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.R.; An, K.N.; Bigliani, L.U.; Friedman, R.J.; Gartsman, G.M.; Gristina, A.G.; Iannotti, J.P.; Mow, V.C.; Sidles, J.A.; Zuckerman, J.D. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 1994, 3, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbart, M.K.; Gerber, C. Comparison of the subjective shoulder value and the Constant score. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2007, 16, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, A.; Davies, M. Rotator Cuff Disease: Treatment Options and Considerations. Sport. Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, S.; Bois, A.J.; Matthewson, G.; Oiwa, S.; More, K.D.; Lo, I.K. The relationship between preoperative Goutallier stage and retear rates following posterosuperior rotator cuff repair: A systematic review. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 32, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, G.; Nogueira, F.; Aridas, C.K. Imbalanced-learn: A Python Toolbox to Tackle the Curse of Imbalanced Datasets in Machine Learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.06570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.J. LIBSVM: A library for support vector machines. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2011, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 4–9 December 2017; NIPS’17. pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalov, F.; Leung, H.H.; Cherukuri, A.K. Keep it simple: Random oversampling for imbalanced data. In Proceedings of the 2023 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 20–23 February 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Int. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Bai, Y.; Garcia, E.A.; Li, S. ADASYN: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), Hong Kong, China, 1–8 June 2008; pp. 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, W.Y.; Mao, B.H. Borderline-SMOTE: A New Over-Sampling Method in Imbalanced Data Sets Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Intelligent Computing, Hefei, China, 23–26 August 2005; Huang, D.S., Zhang, X.P., Huang, G.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douzas, G.; Bacao, F.; Last, F. Improving imbalanced learning through a heuristic oversampling method based on k-means and SMOTE. Inf. Sci. 2018, 465, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Cooper, E.W.; Kamei, K. Borderline over-sampling for imbalanced data classification. Int. J. Knowl. Eng. Soft Data Paradig. 2011, 3, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S.J.; Lee, Y.S. Cluster-based under-sampling approaches for imbalanced data distributions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 5718–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. The condensed nearest neighbor rule (Corresp.). IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1968, 14, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.L. Asymptotic Properties of Nearest Neighbor Rules Using Edited Data. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1972, SMC-2, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomek, I. An Experiment with the Edited Nearest-Neighbor Rule. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1976, SMC-6, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Martinez, T.; Giraud-Carrier, C. An instance level analysis of data complexity. Mach. Learn. 2014, 95, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mani, I. KNN Approach to Unbalanced Data Distributions: A Case Study Involving Information Extraction. In Proceedings of the ICML’2003 Workshop on Learning from Imbalanced Datasets, Washington, DC, USA, 21 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Laurikkala, J. Improving Identification of Difficult Small Classes by Balancing Class Distribution. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, Cascais, Portugal, 1–4 July 2001; Quaglini, S., Barahona, P., Andreassen, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubat, M. Addressing the Curse of Imbalanced Training Sets: One-Sided Selection. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, Nashville, TN, USA, 8–12 July 1997; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, M.; Werner, A.; Palt, M. The Proposal of Undersampling Method for Learning from Imbalanced Datasets. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 159, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomek, I. Two Modifications of CNN. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1976, SMC-6, 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.E.A.P.A.; Prati, R.C.; Monard, M.C. A study of the behavior of several methods for balancing machine learning training data. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2004, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.; Bazzan, A.; Monard, M.C. Balancing Training Data for Automated Annotation of Keywords: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Bioinformatics, Macaé, Brazil, 3–5 December 2003; pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, D.; Maclin, R. An empirical evaluation of bagging and boosting for artificial neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’97), Houston, TX, USA, 12 June 1997; Volume 3, pp. 1401–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liaw, A.; Breiman, L. Using Random Forest to Learn Imbalanced; Data Technical Report 666; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L. (Ed.) Handbook of Genetic Algorithms; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Woolson, R.F. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. In Encyclopedia of Biostatistics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, J.; Deb, K. Pymoo: Multi-Objective Optimization in Python. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 89497–89509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).