Electrically Active Defects and Traps and Their Relation to Stoichiometry and Chemical Environment in HfO2/Al2O3 Dielectric Stacks as Revealed by XPS

Abstract

1. Introduction

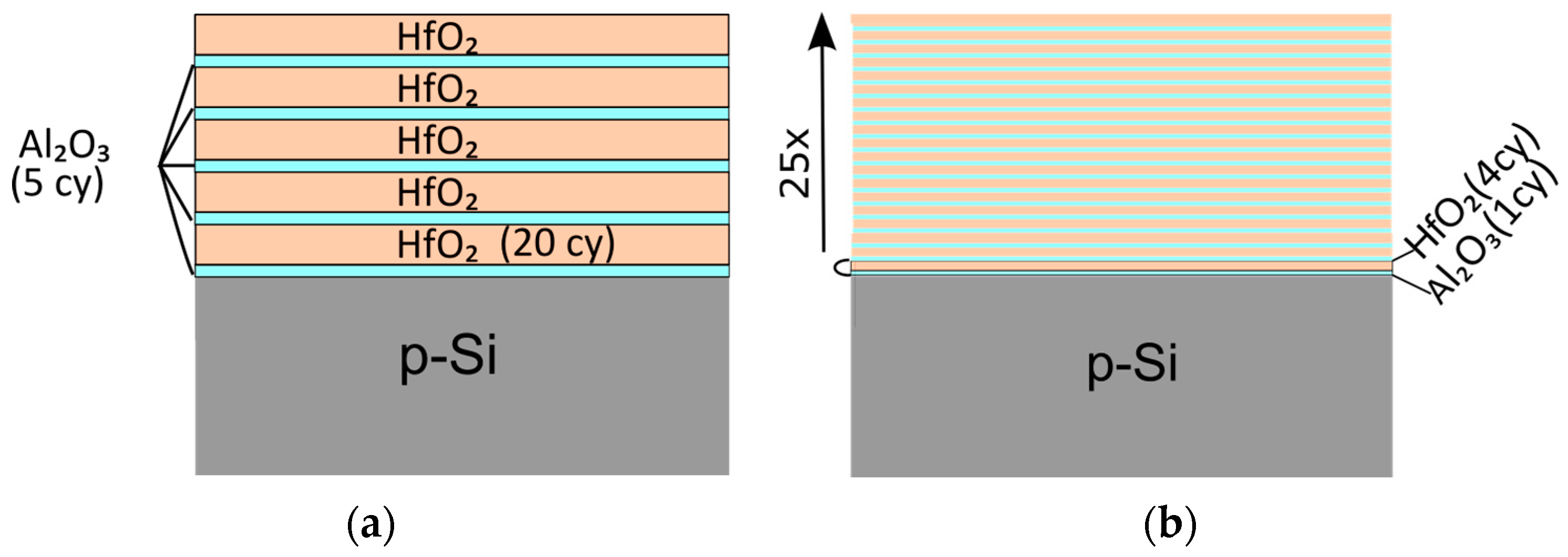

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

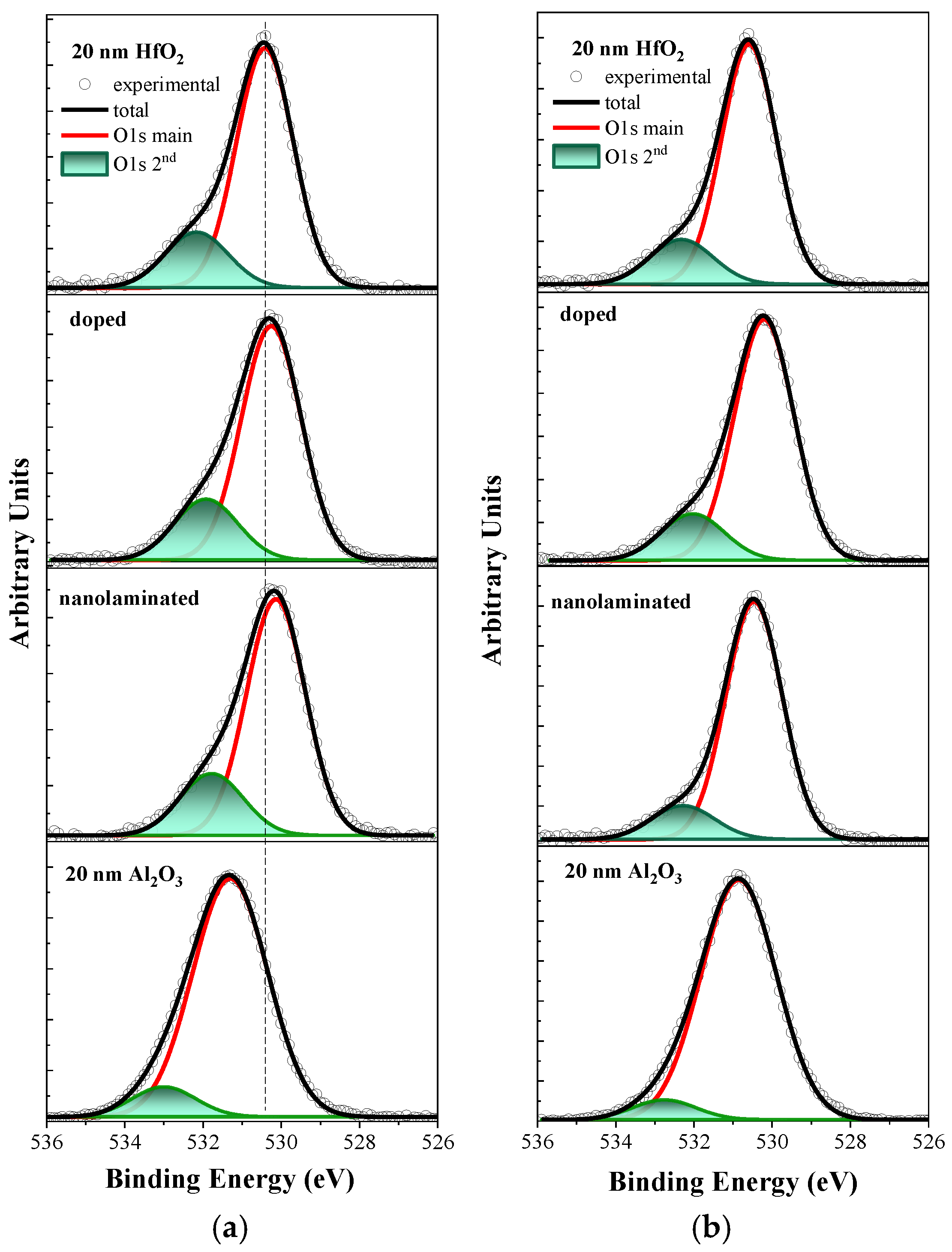

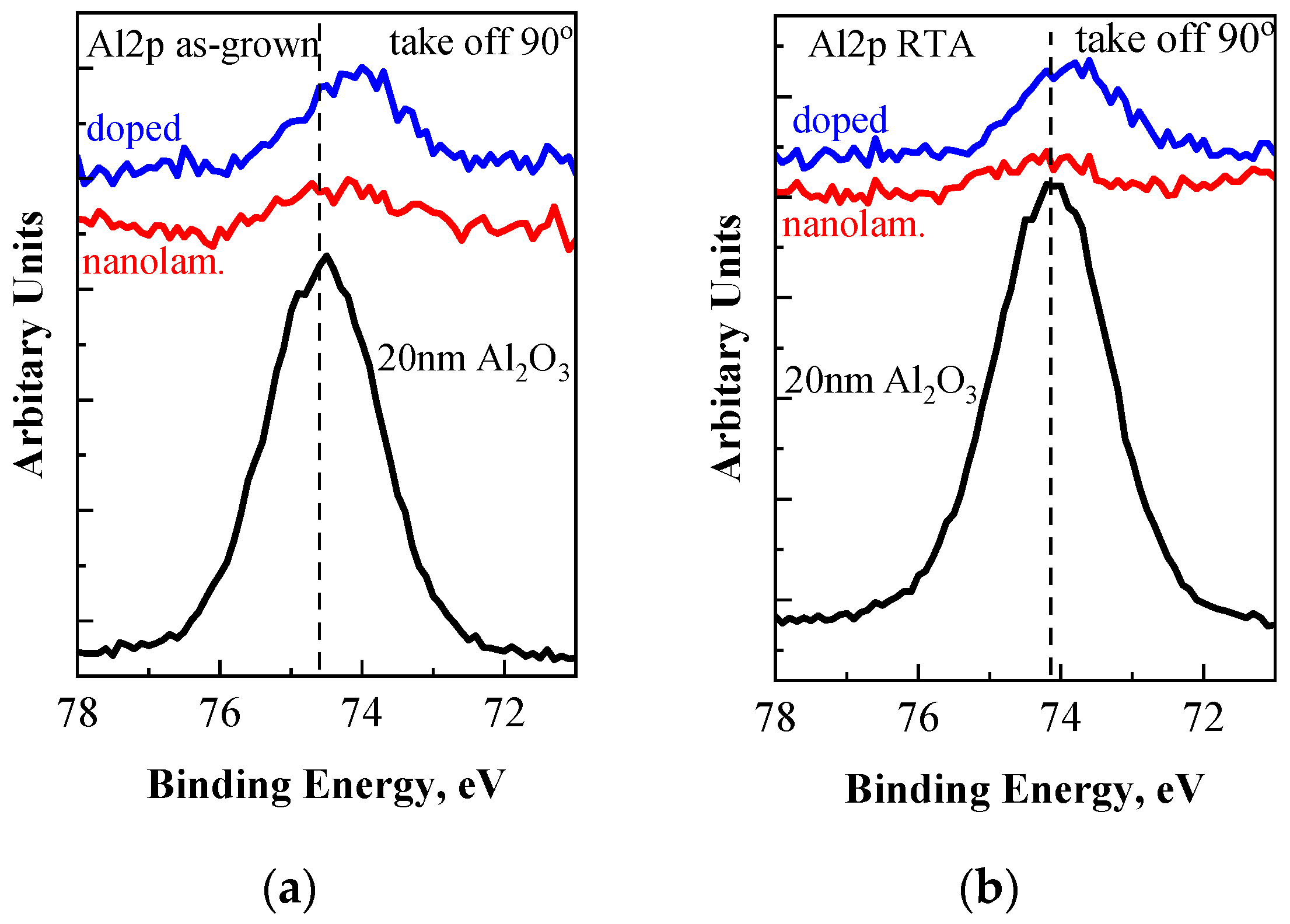

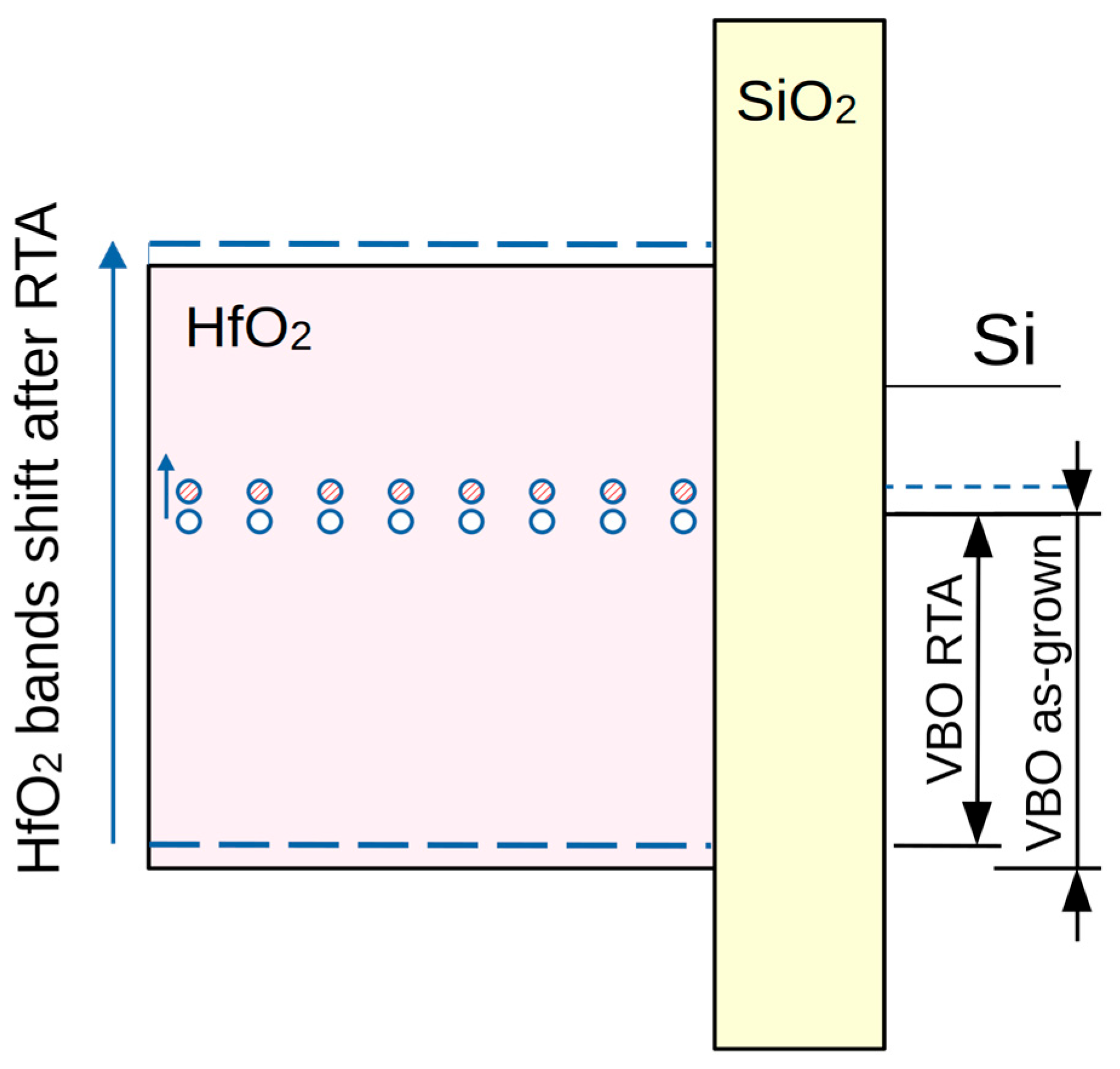

3.1. XPS Study

3.2. Charges in the Stacks

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTM | Charge-Trapping Memory |

| CTL | Charge-Trapping Layer |

| RCA | Radio Corporation of America |

| RTA | Rapid Thermal Annealing |

| BE | Binding Energy |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| VB | Valence Band |

| VBO | Valence Band Offset |

| C-V | Capacitance–Voltage |

| MOS | Metal Oxide Semiconductor |

References

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, C.Z.; Taylor, S.; Chalker, P.R. Review on Non-Volatile Memory with High-k Dielectrics: Flash for Generation Beyond 32 nm. Materials 2014, 7, 5117–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, C.S. Prospective of Semiconductor Memory Devices: From Memory System to Materials. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015, 1, 1400056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, K. Charge trapping NVMs with metal oxides in the memory stack. In Metal Oxides for Non-Volatile Memory: Materials, Technology and Application; Dimitrakis, P., Valov, I., Tappertzhofen, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Houssa, M.; Pantisano, L.; Ragnarsson, L.; Degraeve, R.; Schram, T.; Pourtois, G.; De Gendt, S.; Groeseneken, G.; Heyns, M.M. Electrical properties of high-κ gate dielectrics: Challenges, current issues, and possible solutions. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2006, 51, 37–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Yuan, T.; Kuo, Y.; Lu, J.; Yan, J.; Kuo, W. Charge trapping and dielectric relaxation in connection with breakdown of high-k gate dielectric stacks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 202904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschl, R.; Kerber, M.; Avellan, A.; Jakschik, S.; Schroeder, U.; Kudelka, S. Reliability aspects of Hf-based capacitors: Breakdown and trapping effects. Microelctron. Reliab. 2007, 47, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakis, P. Charge-Trapping Non-Volatile Memories; Dimitrakis, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spiga, S.; Driussi, F.; Lamperti, A.; Congedo, G.; Salicio, O. Effects of Thermal Treatments on the Trapping Properties of HfO2 Films for Charge Trap Memories. Appl. Phys. Express 2012, 5, 021102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Cho, E.C.; Yi, J. Analysis of HfO2 Charge Trapping Layer Characteristics After UV Treatment. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Huo, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Long, S.; Liu, M. Performance Enhancement of Multilevel Cell Nonvolatile Memory by Using a Bandgap Engineered High-k Trapping Layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 253503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Ou, X.; Cao, Y.; Tang, S.; Gong, C.; Xu, B.; Xia, Y.; Yin, J.; Li, A.; Yan, F.; et al. The effect of thermal treatment induced inter-diffusion at the interfaces on the charge trapping performance of HfO2/Al2O3 nanolaminate- based memory devices. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 044104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Xin, D.; Kim, T.; Choi, J.; Cho, J.; Yi, J. Improvement of the Charge Retention of a Non-Volatile memory by a Bandgap Engineered Charge Trap Layer. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Wu, Z.; Yin, H. The Effect of Thermal Treatment Induced Performance Improvement for Charge Trapping Memory with Al2O3/(HfO2)0.9(Al2O3)0.1/Al2O3 Multilayer Structure. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, Q229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.; Kim, T.; Agrawal, K.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Kim, H.H.; Cho, E.C.; Yi, J. Optimization of MIS type Non-volatile Memory Device with Al-doped HfO2 as Charge Trapping Layer. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 075004. [Google Scholar]

- Paskaleva, A.; Rommel, M.; Hutzler, A.; Spassov, D.; Bauer, A.J. Tailoring the Electrical Properties of HfO2 MOS-Devices by Aluminum Doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 17032–17043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spassov, D.; Paskaleva, A.; Krajewski, T.A.; Guziewicz, E.; Luka, G.; Ivanov, T. Al2O3/HfO2 Multilayer High-k Dielectric Stacks for Charge Trapping Flash Memories. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2018, 215, 1700854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassov, D.; Paskaleva, A.; Guziewicz, E.; Wozniak, W.; Stanchev, T.; Ivanov, T.; Wojewoda-Budka, J.; Janusz-Skuza, M. Charge Storage and Reliability Characteristics of Nonvolatile Memory Capacitors with HfO2/Al2O3-Based Charge Trapping Layers. Materials 2022, 15, 6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassov, D.; Paskaleva, A. Challenges to Optimize Charge Trapping Non-Volatile Flash Memory Cells: A Case Study of HfO2/Al2O3 Nanolaminated Stacks. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scofield, J.H. Hartree-Slater subshell photoionization cross-sections at 1254 and 1487 eV. J. Electron Spectrosc. Rel. Phenom. 1976, 8, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, D.K. Semiconductor Material and Device Characterization, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Chapter 6; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- Manikanthababu, N.; Dhanunjaya, M.; Nageswara Rao, S.V.S.; Pathak, A.P. SHI induced effects on the electrical and optical properties of HfO2 thin films deposited by RF sputtering. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2016, 379, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Guo, T.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z. Charge transport and bipolar switching mechanism in a Cu/HfO2/Pt resistive switching cell. Chin. Phys. B 2016, 25, 117306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Kong, J.-Z.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Li, A.-D.; Wang, L.-G.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.-Q.; Wu, D. Bipolar Resistive Switching Characteristics of HfO2/TiO2/HfO2 Trilayer-Structure RRAM Devices on Pt and TiN-Coated Substrates Fabricated by Atomic Layer Deposition. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Liang, Y.; He, K.; Sun, W.; Lin, H.-H.; Yao, S.; Lu, X.; Wan, L.; et al. Investigation of HfO2 Thin Films on Si by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, Rutherford Backscattering, Grazing Incidence X-ray Diffraction and Variable Angle Spectroscopic Ellipsometry. Crystals 2018, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, B.; Yu, S.; Lai, L.; Zeng, L.; Sun, B.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Han, R.; et al. Effects of Ionic Doping on the Behaviors of Oxygen Vacancies in HfO2 and ZrO2: A First Principles Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices, San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 September 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Materlik, R.; Künneth, C.; Falkowski, M.; Mikolajick, T.; Kersch, A. Al-, Y-, and La-doping effects favoring intrinsic and field induced ferroelectricity in HfO2: A first principles study. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 164101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Li, M.F.; Cho, B.J.; Yeo, C.C.; Joo, M.S.; Kwong, D.-L.; Pan, J.S.; Ang, C.H.; Zheng, J.Z.; Ramanathan, S. Energy gap and band alignment for on (100) Si. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberger, M.; Paskaleva, A.; Zürcher, S.; Bauer, A.J.; Frey, L.; Ryssel, H. Electrical properties of hafnium silicate films obtained from a single-source MOCVD precursor. Microelectron. Reliab. 2005, 45, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Aziz, I.; Ciou, J.-H.; Waang, J.; Gao, D.; Xiong, J.; Lee, P.S. Al2O3/HfO2 Nanolaminate Dielectric Boosting IGZO-Based Flexible Thin-Film Transistors. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suri, R.; Kirkpatrick, C.J.; Lichtenwalner, D.J.; Misra, V. Energy-band alignment of Al2O3 and HfAlO gate dielectrics deposited by atomic layer deposition on 4H–SiC. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 042903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H.; Moon, D.W.; Park, S.A.; Kim, Y.K.; Jeong, K.; Kang, S.K.; Ko, D.-H.; Doh, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, N.I. Interfacial characteristics of N-incorporated HfAlO high-k thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 5243–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, L.D.; Meng, G.W.; Li, G.H.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, J.P. Temperature-dependent structural stability and optical properties of ultrathin Hf–Al–O films grown by facing-target reactive sputtering. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 094103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Liu, G.; Zhu, H.; Shin, B.; Fortunato, E.; Martins, R.; Shan, F. Eco-friendly water-induced aluminum oxide dielectrics and their application in a hybrid metal oxide/polymer TFT. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 86606–86613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Li, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X. Potential solution-induced HfAlO dielectrics and their applications in low-voltage-operating transistors and high-gain inverters. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 36584–36595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Oh, S.K.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Cho, M.-H. Band alignment in ultrathin Hf-O-Al/Si interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 212902. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, E.A.; Grant, R.W.; Waldrop, J.R.; Kowalczyk, S.P. Precise Determination of the Valence-Band Edge in X-Ray Photoemission Spectra: Application to Measurement of Semiconductor Interface Potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 1620–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Bersch, E.; Di, M.; Consiglio, S.; Clark, R.D.; Leusink, G.J.; Diebold, A.C. Complete band offset characterization of the HfO2/SiO2/Si stack using charge corrected x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 043702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleetwood, D.M.; Shaneyleft, M.R.; Warren, W.L.; Schwank, J.R.; Meisenheimer, T.L.; Winokur, P.S. Border traps: Issues for MOS radiation response and long-term reliability. Microelectron. Reliab. 1995, 35, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Kim, J.-G.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, T.-W. Characterization of Al Incorporation into HfO2 Dielectric by Atomic Layer Deposition. Micromachines 2019, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.F.; Gong, X.G.; Li, Q. Energetics and electronic structure of aluminum point defects in HfO2: A first-principles study. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 014104. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Mondal, S.; Koteswara Rao, K.S.R. Probing the oxygen vacancy associated native defects in high-κ HfO2 using deep level transient spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 04530. [Google Scholar]

- Gritsenko, V.A.; Perevalov, T.V.; Islamov, D.R. Electronic properties of hafnium oxide: A contribution from defects and traps. Phys. Rep. 2016, 613, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. The role of oxygen-related defects and hydrogen impurities in HfO2 and ZrO2. Microelectron. Eng. 2011, 88, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Hf 4f Peak | Hf 4f7/2 Position, eV | FWHM, eV | Hf 4f (Stoichiometric)/Hf 4f (Suboxide) Peak Area Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-Grown | RTA | As-Grown | RTA | As-Grown | RTA | ||

| pure HfO2 | Stoichiometric | 17.6 | 17.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.69 | 1.92 |

| Suboxide | 16.9 | 16.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |||

| doped | Stoichiometric | 17.5 | 17.5 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 1.53 |

| Suboxide | 16.8 | 16.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | |||

| nanolaminated | Stoichiometric | 17.6 | 17.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.66 | 1.5 |

| Suboxide | 16.9 | 16.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |||

| Sample | Peak | O 1s Position, eV | O 1s (Main)/O 1s (2nd) Area Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-Deposited | RTA | As-Deposited | RTA | ||

| pure HfO2 | main Me-O peak | 530.45 | 530.6 | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| second peak | 532.15 | 532.3 | |||

| doped | main Me-O peak | 530.3 | 530.2 | 3.6 | 4.9 |

| second peak | 531.9 | 532.0 | |||

| nanolaminated | main Me-O peak | 530.1 | 530.4 | 3.5 | 6.3 |

| second peak | 531.8 | 532.3 | |||

| pure Al2O3 | main Me-O peak | 531.30 | 530.8 | 9.4 | 14.4 |

| second peak | 533.00 | 532.75 | |||

| Sample | Valence Band Edge, Ev(ox) eV | Valence Band Offset ΔEv, eV |

|---|---|---|

| nanoalminated, as-grown | 3.46 | 3.22 |

| nanolaminated, RTA | 3.31 | 3.07 |

| doped, as-grown | 3.18 | 2.94 |

| doped, RTA | 3.11 | 2.87 |

| HfO2, as-grown | 3.55 | 3.31 |

| HfO2, RTA | 3.32 | 3.08 |

| Sample | Treatment | Qf, cm−2 | Hysteresis Vfb, V | Qsl, cm−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure HfO2 | as-grown | 3.5 × 1012 | 3.2 | 8.9 × 1012 |

| RTA | 3.5 × 1012 | 0.3 | 8.8 × 1011 | |

| Nanolaminated | as-grown | 1.1 × 1012 | 1.2 | 3.5 × 1012 |

| data | 3.9 × 1012 | 0.3 | 1.1 × 1012 | |

| Doped | as-grown | 1.4 × 1012 | 1.5 | 4.3 × 1012 |

| RTA | 1.2 × 1012 | 0.8 | 2 × 1012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spassov, D.; Paskaleva, A.; Avramova, I.; Wozniak, W.; Guziewicz, E. Electrically Active Defects and Traps and Their Relation to Stoichiometry and Chemical Environment in HfO2/Al2O3 Dielectric Stacks as Revealed by XPS. Materials 2025, 18, 5420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235420

Spassov D, Paskaleva A, Avramova I, Wozniak W, Guziewicz E. Electrically Active Defects and Traps and Their Relation to Stoichiometry and Chemical Environment in HfO2/Al2O3 Dielectric Stacks as Revealed by XPS. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235420

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpassov, Dencho, Albena Paskaleva, Ivalina Avramova, Wojciech Wozniak, and Elzbieta Guziewicz. 2025. "Electrically Active Defects and Traps and Their Relation to Stoichiometry and Chemical Environment in HfO2/Al2O3 Dielectric Stacks as Revealed by XPS" Materials 18, no. 23: 5420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235420

APA StyleSpassov, D., Paskaleva, A., Avramova, I., Wozniak, W., & Guziewicz, E. (2025). Electrically Active Defects and Traps and Their Relation to Stoichiometry and Chemical Environment in HfO2/Al2O3 Dielectric Stacks as Revealed by XPS. Materials, 18(23), 5420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235420