Abstract

The interest in nanoparticles (NPs) and their effects on living organisms has been continuously growing in the last decades. A special interest is focused on the effects of NPs on the central nervous system (CNS), which seems to be the most vulnerable to their adverse effects. Non-metallic NPs seem to be less toxic than metallic ones; thus, the application of non-metallic NPs in medicine and industry is growing very fast. Hence, a closer look at the impact of non-metallic NPs on neural tissue is necessary, especially in the context of the increasing prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge of the in vitro and in vivo neurotoxicity of non-metallic NPs, as well as the mechanisms associated with negative or positive effects of non-metallic NPs on the CNS.

1. Introduction

The unique features of nanoparticles (NPs), e.g., size and strong absorption properties, make them more reactive in the biological environments, due to their exceptional chemical properties and ability to get different sites of organisms, as compared to a bulk material with the same chemical composition. To exploit these new capabilities, NPs were introduced to everyday life as industry and medicine products, e.g., biosensors, biomaterials, tissue engineering systems, drugs and drug-delivery systems for diagnosis and treatment of many diseases, including that of the central nervous system (CNS) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

The CNS can be reached by NPs through three different pathways. The first and the most likely is through systemic blood circulation, as NPs can cross blood–brain and blood–spinal cord barriers. The second path is a nose-to-brain route along nerve bundles that cross the cribriform plate to the olfactory bulb. Finally, NPs can diffuse through the nasal cavity mucosa to reach the branches of the trigeminal nerve in the olfactory and respiratory regions and then reach the brain stem via axonal transport [8,9,10].

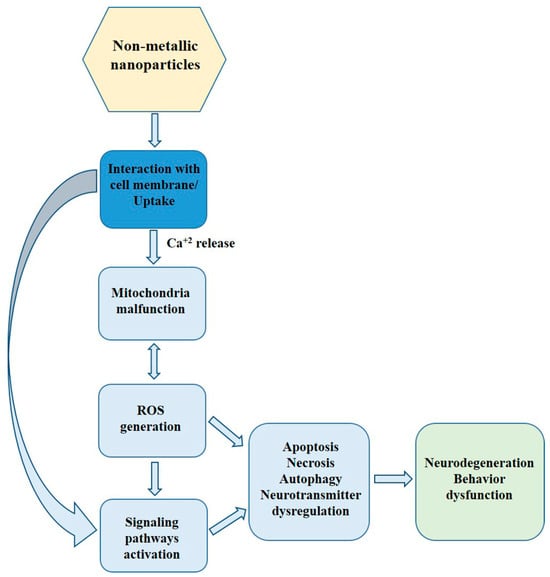

The presence of nanomaterials in the CNS may have unexpected consequences, including acute or chronic neurological complications [2,8]. Though numerous studies clearly indicate in vitro and in vivo oxidative stress-associated adverse effects of metallic NPs in the CNS (for recent review, see Sawicki et al. [11]), the toxicity of non-metallic NPs (nmNPs) in the CNS remains obscure. Here, we review the in vitro and in vivo studies regarding the neurotoxicity of nmNPs and summarize the current state of knowledge in this area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The scheme of direct and indirect action of nmNPs in CNS.

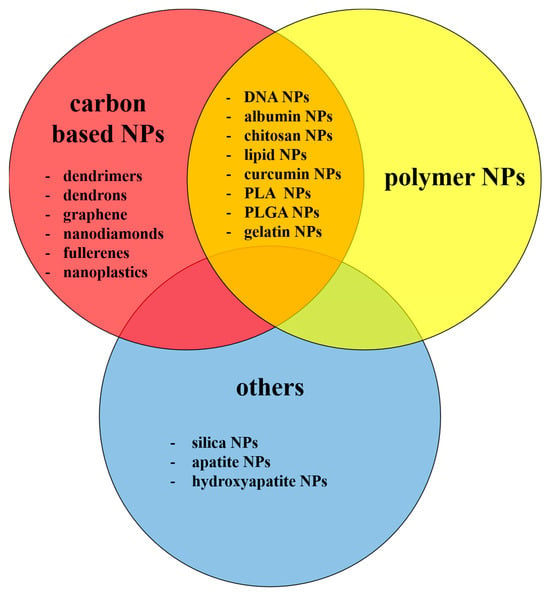

2. Non-Metallic NPs

Pure carbon NPs constitute the largest and most important group of nmNPs, which include nanotubes, nanohorns, nano-onions, nanodiamonds, fullerenes and graphene, and exhibit large diversity in structure, morphology, physical properties and chemical reactivity [1,12,13,14,15]. Another carbon-containing, large group of nmNPs are dendrimers. These NPs have a highly branched three-dimensional structure, consisting of an initial core, several internal layers, repetitive units and several terminal active surface groups. The presence of a hydrophobic core and multiple surface groups makes them a good candidate for high-load drug carriers [1,16,17]. Other nmNPs discussed later in this review include polymer NPs, silica NPs, apatite, and hydroxyapatite NPs, also widely described in scientific literature in connection with CNS.

These and other types of NPs discussed in the present review are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Types of the nmNPs discussed in the present review.

3. Uptake of Non-Metallic NPs

3.1. Uptake of Non-Metallic NPs by Normal CNS-Derived Cells In Vitro

Various cells responsible for maintaining brain homeostasis can accumulate nmNPs. The most important seems to be microglia, brain macrophages responsible for clearance from damaged or dead cells and other dangerous particles [18]. Microglia are also primary cells responsible for the clearance of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs), an allotropic form of pure carbon structured in a shape of empty nested fibers (concentric cylinders). MWTNTs distinguish from other types of nanomaterials, as their length can be thousands of times larger than their diameter [19]. Carboxylic acid group modified MWNTs were observed inside microglial cells in ex vivo mixed cultures isolated from the rat’s brain [20]. In vitro, an average phagocytosis time for MWNTs by the human microglia (BV-2 cells) was approximately 2 h, and MWNTs were completely internalized after 6 h [21]. In line, the presence of acid-oxidized or pristine MWNTs in N9 microglial cells was observed after several hours of treatment [22]. The MWNTs accumulated in various cellular compartments, such as cytoplasm, phagolysosomes, endosomes and lysosomes, with the exception of the nucleus, which seemed to be free from MWNTs [20,22]. With regard to other types of nmNPs internalized by microglial cells, the following can be listed: silica nanoparticles (SiNPs) [23], indocyanine green (ICG)-coated polycaprolactone (PCL)-rhodaminedoped NPs, Si-ICG/PCL-polylactic acid (PLLA)-rhodamine-doped NPs [24] and G4 and G4-C12-modified polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers [25]. The internalization of cyanine5-labeled hydroxyl terminated 4th generation (G4) PAMAM dendrimers by microglial cells was more efficient than by other types of brain cells, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes or neurons [26,27,28,29,30].

Besides microglia, the ability to internalize nmNPs has been shown for astrocytes, which are involved in many processes, including the biochemical support of endothelial cells, the formation of blood–brain barrier (BBB), the provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, maintenance of extracellular ion balance and repair and scarring process of the brain [31]. The astrocytes internalized MWNTs, less efficiently than microglial cells [19]; however, the process was facilitated by the functionalization of MWNTs with amine groups [32].

The internalization of nmNPs by neurons, paramount cells in the CNS, is less efficient when compared to the other cell types. Resveratrol-loaded NPs based on poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PVP-b-PCL), were mainly localized in the cytoplasm, dendrites and axons of cortical neurons [33]. In line, neurons internalized also polylactide-co-glycolic-acid (PLGA) NPs loaded with curcumin and modified with g7 ligand [34], poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) (PLGA-PEG) conjugated with B6 peptide and loaded with curcumin [35] or lactose myristoyl carboxymethyl chitosan and algal polysaccharide myristoyl carboxymethyl chitosan NPs [36]. In addition, mouse hippocampal neurons and mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons internalized nanodiamonds and accumulated them inside the cell bodies of cortical neurons and inside membrane-surrounded organelles [37]. It was also shown that PAMAM dendrimers were able to penetrate into human neural progenitor cells cultured as a 3D neurosphere model [38] and that amino-functionized G5 PAMAM dendrimers accumulate in the plasma membrane of neurons, as soon as 30 min after treatment [39].

Finally, the presence of nmNPs was also reported for brain endothelial cells. This type of cell maintains the delicate balance of ions, nutrients and other molecules essential for proper brain function and is responsible for removing toxins from the CNS [40]. Liu et al. [41] showed that SiNPs modified with PEG were taken up by mouse cerebral endothelial cells (bEnd.3) with the efficiency dependent on the size of NPs. This was confirmed by Ye et al. [42], who reported that the uptake of SiNPs by human capillary microvascular endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3) was more efficient for 50 nm NPs than for 200 nm NPs. SiNPs were localized inside intracellular vesicles along the endo–lysosomal pathway, inside membrane-bound vesicles and in late endosomes. Other kinds of nmNPs taken up by brain endothelial cells include PEG and polyethylenimine nanogel [43], amino-functionalized MWNTs [32] and fullerenes [44]. The interaction of MWNTs with the plasma membrane of endothelial cells was observed after 4 h of incubation, while their accumulation in endoplasmic vesicles and multi-vesicular bodies was observed after 24 h of treatment and was depended on the NPs concentration [32].

3.2. Uptake of Non-Metallic NPs by CNS-Derived Cancer Cells In Vitro

Though NP uptake by normal brain cells may have adverse effects, the internalization of NPs by brain cancer cells opens the possibility for the development of new NP-based theranostic therapies. Among several types of brain cancers, neuroblastoma and astrocytoma are the most frequent ones [45,46] and are often used for testing their interactions with NPs. Various neuroblastoma and astrocytoma cells were able to take up nmNPs, including SiNPs [47], rhodamine doped Si-ICG/PCL/PLLA NPs [24], curcumin-loaded lactoferrin NPs [48], curcumin-loaded PLGA NPs [49], carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [50], and polymeric NPs and liposomes [51]. These particles accumulated in a membrane region, cytoplasm and a region over the nucleus [47,49,50]. According to Listik et al. [51], the efficiency of internalization depends on the type of NPs and cancer cells. The authors studied an uptake of polysorbate-80 coated polymeric NPs and liposomes coupled with G-protein estrogen receptor selective agonist, in N2a and SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Liposomes were identified inside N2a cells after 6 and 24 h of incubation, while polymeric NPs were detected only after 24 h. In the case of SHSY5Y cells, liposomes were internalized in less than 30 min, whereas the internalization of polymeric NPs is characterized by a slower kinetic profile (internalization was observed after more than 6 h).

Gliomas, which arise from glial cells of the brain or spine and are one of the most invincible cancers, constitute another important group of brain cancers [52]. Many studies indicated that nmNPs were easily taken up by glioma cells, e.g., C6 cells. The NPs tested in this in vitro model include G7 PAMAM dendrimers with amine, acetamide and carboxylate end groups [53], coumarin-6 loaded D-α-tocopheryl PEG1000 succinate (TPGS) coated liposomes [54], PEG-PCL NPs loaded with resveratrol [55], curcumin-loaded polysaccharide nanoformulations based on hyaluronic acid and chitosan hydrochloride NPs [56], temozolomide-loaded PLGA NPs functionalized with anti-EPHA3 [57], and transferrin-conjugated polylactide (PLA)-D-α-tocopheryl-PEG-succinate diblock copolymer NPs [58]. The uptake of NPs occurs very fast; the NPs were observed inside glioma C6 cells after 2 h of incubation [59]. Moreover, it was shown that modifications of NPs and/or targeting with receptor-specific antibody (ephrin type-A receptor 3 tyrosine kinase antibody-modified PLGA NPs and enhancer-modified albumin NPs) change internalization efficacy [57,60].

3.3. Uptake of Non-Metallic NPs by CNS In Vivo

In order to reach the brain, NPs must cross the BBB, a decisive barrier between the brain and systemic circulation. This structure is formed by a complex system of endothelial cells, astroglia, pericytes and perivascular mast cells and is stabilized by a multiprotein complex that seals gaps between endothelial cells and prevents leakage of the barrier, known as a tight junction. The BBB plays an important metabolic role by disposing of waste products, metabolizing different chemical compounds, both drugs and toxins, and protecting the CNS from changes in the ionic composition of cerebrospinal fluid [61,62].

NPs can penetrate through the tight junctions of BBB and their presence in brain cells and tissue was described for single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) [63], cationic albumin conjugated PEG–PLLA NPs [64], SiNPs [65] and many others. Translocation from systemic circulation to brain tissue occurred very fast. Labeled, amino-functionalized MWNTs were present in the brain of mice 5 min after intravenous injection [32]. Similarly, poly(n-butylcyanoacrylate) dextran polymer NPs coated with polysorbate 80 were detected in mice brains 18 min after injection [66]. The mechanisms of NP uptake by brain cells include phagocytosis, macropinocytosis, and clathrin and caveolin-mediated endocytosis [25,67]. Different receptors may also be involved, as was shown for folic acid [68], apolipoprotein E, low-density lipoprotein receptors and GLUT transporter [67,69].

Initial localization of NPs in the brain tissue depends mainly on a mode of administration. Intravenously administered amino-functionalized MWNTs localized mainly in brain capillaries and parenchyma fraction [32], whereas radiolabeled SiNPs modified with aminopropyltriethoxysilane applied to mice through intranasal instillation localized mostly in the striatum. From brain microvasculature, NPs can be transferred to other regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus (CA1 and CA3 regions), brain stem, cerebellum, and frontal cortex, while intranasal administration resulted in the presence of NPs also in the olfactory bulb [65]. The final localization of NPs depends mostly on their modifications and mode of administration. Bardi et al. [70] tested the internalization of oxidized and non-oxidized amino-functionalized MWNTs (oxMWNT-NH3+ and MWNT-NH3+, respectively) and reported that, after stereotactic administration, MWNTs-NH3+ were abundantly and evenly dispersed along the injection site and within the brain parenchyma, while oxMWNTs-NH3+ were observed mainly as small clusters in intracellular vesicles in microglia, astrocytes and neurons, with the minority in extravesicular cytoplasmic or brain parenchymal areas. After intracortical administration, MWNTs-NH3+ were dispersed throughout the brain parenchyma, forming small aggregates inside membranous intracellular vesicles or as a single nanotube residing in the cytoplasm. In contrast, oxMWNTs-NH3+ were present in clusters and were rarely seen in the cytoplasm, as a single nanotube.

Despite NP modifications and mode of administration, NP uptake and localization in the brain tissue depend also on their size, coating and cargo. Size-dependent differences in the uptake and biodistribution of nmNPs were reported for fluorescent polystyrene latex nanospheres. 20 nm fluorescent polystyrene latex nanospheres were not detected in the brain of rats after intravenous injection or oral pharyngeal aspiration, whereas 100 nm and 1000 nm spheres were present in the CNS 24 h after administration [71]. Similarly, the study with hydroxyl-PAMAM dendrimers in a dog model of a hypothermic circulatory arrest revealed that G6 dendrimers (approx. diameter 6.7 nm) showed extended blood circulation time and increased accumulation in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), hippocampus, cerebellum and cortex of the injured brain, whereas smaller, G4 dendrimers (approx. diameter 4.3 nm) were undetectable in the brain even 48 h after the final administration [30].

It was also shown that coating with a ligand for the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 peptide (angiopep-2), antibodies, bovine serum albumin, apolipoprotein E, and transferrin improve the NP uptake by CNS. MWNTs coated with angiopep-2 were more intensively taken up by glioma-bearing brains than NPs without the ligand [72]. Enhanced accumulation in brain tissue was also observed for transferrin-loaded solid lipid NPs [73], liposomes with bovine serum albumin [74], biodegradable polymersomes with cationic bovine serum albumin [75] and antibody-coated polymer-based NPs [76]. This effect was attributed to enhanced phagocytosis by macrophages [76]. Enhanced uptake of NPs into the brain was also observed after the coating of NPs with a nonionic surfactant—polysorbate 80, nonionic block copolymer—poloxamer 188 and chitosan polysaccharide [77]. In line, Calvo et al. [78] reported that PEGylated poly(cyanoacrylate) NPs can penetrate the brain of mice and rats. The concentration of PEGylated NPs was significantly higher than uncoated ones in the majority of brain structures, especially those in the deeper regions of the brain (striatum, hippocampus, hypothalamus and thalamus). Further, fluorescent COOH-modified polystyrene particles covalently modified with methoxyPEG(NH2) rapidly diffused within normal rat brain tissue, but only if coated with an exceptionally dense layer of PEG [79].

An Important factor affecting the penetration of NPs is also the brain intactness. The ability of G6 dendrimers to cross the BBB correlated with the extent of CNS inflammation, while their accumulation was more efficient in injured places [30]. Similarly, in a rabbit cerebral palsy model, ethylenediamine-core PAMAM dendrimers were more abundantly present in the brain parenchyma of regions characterized with significant inflammation, as compared to the healthy regions [26].

4. Toxicity of Non-Metallic NPs in Mammals

4.1. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Toxicity

Many reports indicate that metallic NPs are toxic to CNS. Their neurotoxicity is associated with the induction of oxidative stress in the brain tissue through the release of metal ions [11]. Similarly, numerous reports also show detrimental effects of nmNPs (Table 1).

Table 1.

The effect of nmNPs (toxic or non-toxic) on CNS-derived normal cells in vitro.

The tables included in this publication present information on the toxic and non-toxic effects of various types of NPs on the CNS (in vitro and in vivo studies).

In vitro research on various types of brain cells clearly show that toxicity of nmNPs is dependent on cell type and uptake of NPs. In accordance, Du et al. [81] observed an intense uptake of SiNPs by microglial N9 and endothelial bEnd.3 cells, while neuronal HT22 cells barely internalized the NPs. Consequently, toxicity of SiNPs described as morphological changes, such as swelling and cell membrane blebbing, was higher in BV-2 and N9 cell lines than in HT22 cells. A similar result was reported for CNTs, as sensitivity of internalization prone microglia to CNTs was higher than internalization tardy neurons [19].On the other hand, many publications reported also the lack of detrimental effects of nmNPs. In the study conducted by Ducray et al. [24] exposure of primary hippocampal cultures to SiNPs coated ICG/PCL-rhodamine-doped NPs or Si-ICG/PLLA-rhodamine-doped NPs did not affect cell viability, however as noticed earlier, these NPs impaired cell differentiation. The lack of impact of SiNPs on cellular viability was also observed for endothelial cells (bEnd.3) [96] and for A-172 brain cells [105]. In addition, carbon NPs [19,21,22,32,44,97], modified PAMAM dendrimers [28,89,106], PEG–based dendrimers [107], polymer NPs [102], PEG/polyethylenimine (“nanogel”) NPs modified with oligonucleotides [43], PLGA NPs modified with PEG and phage-displayed peptides [101], solid lipid NPs, as well as albumin and chitosan NPs [67,75,91,108] were also reported to be non-toxic to glial cells, neurons and endothelial cells.

Toxicity of nmNPs to CNS-derived normal cells is definitely an unfavorable phenomenon. On the other hand, toxicity to cancer cells may be exploited for development of new anticancer drugs provided that selective accumulation of NPs in cancer cells can be achieved. Numerous reports indicate the toxic effects of nmNPs on glioma and glioblastoma cells in vitro. Transferrin conjugated PLA-D-α-tocopheryl PEG succinate diblock copolymer NPs [58] inhibited growth of glioma C6 cells. In line, exposure to PAMAM dendrimers and dendrons resulted in reduced cell size, rounded shape and loss of neurites of cells belonging to several glioma lines [109].

In contrast to the above results, several publications showed the lack of toxicity of nmNPs to CNS-derived cancer cells, e.g., MWNTs and SWNTs shown no toxicity to glioma GL261 [21,110], also no adverse effects were observed after treatment of glioblastoma A-172 cell line with SiNPs [105].

More detailed information about nmNPs effects on CNS-derived non-cancer and cancer cells in vitro is presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 2.

The effect of nmNPs (toxic or non-toxic) in CNS-derived cancer cell in vitro.

4.2. Toxicity In Vivo

Many in vivo studies conducted using mammals describe neurotoxic effects associated with the presence of nmNPs in the brain (Table 3).

Table 3.

The effect of nmNPs (toxic or non-toxic) in vivo. Mammalian species.

Interestingly, exposure to nmNPs might exert different effects in various brain regions, e.g., polysorbate 80-modified chitosan NPs were deposited mainly in the frontal cortex and cerebellum of the rats’ brain after systemic injection. Although no signs of oxidative stress were observed, apoptosis and necrosis of neurons and mild inflammatory response were observed in the frontal cortex, whereas in the cerebellum a decrease in the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein was the only detected sign of degenerative changes [143]. In line, though reductions in the number and dispersion of Nissl bodies were observed in neurons of mice exposed to FITC-tagged SiNPs, the effect was spatially limited to the frontal cortex and was not present in the other brain regions, such as the hippocampus [137]. The toxicity of nmNPs partially depends on the disruption of BBB integrity, as acute pulmonary exposure to MWNTs caused a neuroinflammatory response in rodents that was dependent on the disruption of BBB integrity [141].

On the other hand, many in vivo studies show also that nmNPs are low- or non-toxic to CNS. Bardi et al. [97] demonstrated that the injection of MWNTs coated with pluronic F127 surfactant into mice brain resulted only in a small injury area. No damage to the overall brain structure and tissue was observed. No pathological changes were also observed in mice brain after 28 days of exposure to carboxylated MWNTs [147]. No adverse effects associated with CNS in rodents, despite the penetration of BBB, were also detected for other kinds of carbon NPs, such as fullerenes [148], dextran-coated graphene oxide nanoplatelets [163], water soluble fluorescent carbon nano onions [151] and nanodiamonds [37]. In line, similar results were published for other types of nmNPs, such as SiNPs [105], dendrimers, dendriplexes [90] and poly(n-butyl cyanoacrylate)dextran polymers [66]. See Table 3 for details.

5. Mechanism of nmNPs Toxicity. Other Adverse Effects of Non-Metallic NPs in Mammals

In spite of direct interactions with cells or cellular components leading to non-metallic nanomaterials toxicity, several indirect mechanisms were proposed to have a role in this process.

Non-toxic doses of SiNPs caused Ca2+ flux into neuronal cells in a size and surface charge dependent manner, stimulating long-lasting but reversible calcium signaling. Voltage-dependent and transient receptor potential-vanilloid 4 channels were involved in this process. Interestingly, NP internalization was not necessary to induce the calcium flux [83]. The enhancement of Ca2+ concentration after interaction with plasma membrane was also observed in pyramidal neurons and astroglial cells of rat hippocampal slices treated with 5th generation dendrimers (PAMAM G5). The increase in Ca2+ concentration was followed by the mitochondria depolarization of astroglial cells [39].

Another indirect mechanism of toxicity of non-metallic NPs involves alterations in gene and protein expression. Inhibition of the expression of mitochondrial deacetylase SIRT3 that plays an important role in regulation of cellular metabolism was proposed as a cause of increased oxidative stress in mitochondria and reprogramming of cellular metabolism in LPS-stimulated mice microglia treated with single-walled carbon nanohorns. This resulted in G1 arrest and increased the apoptosis of treated cells [87].

The treatment of rat brain capillary endothelial cells with gold and polymer-coated Si-ICG/PCL and Si-ICG/PCL/PLLA NPs resulted in a time- and concentration-dependent decrease in the phosphorylation of MAPKs, which participate in cellular response to a diverse array of stimuli, such as mitogens, osmotic stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines, and regulate cell proliferation, gene expression, differentiation, mitosis and many others [82]. Yet, another alteration in gene expression was shown in a 3D model of human neural progenitor cells incubated with PAMAM-NH2 dendrimers. In this model, NPs inhibited cell proliferation and migration, which was accompanied by the down-regulation of several genes, including early growth response gene 1 (EGR1), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI2) and adrenomedullin (ADM) [38].

Incubation of neuroblastoma N2a cells with MWNTs promoted nuclear translocation and acetylation of NFκB transcription factor in a dose-dependent manner, followed by up-regulation of nNOS and an increase in NO production [111]. The NFκB-dependent signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of immunity, inflammation, cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis [164].

Another important cellular signaling pathway affected by nmNPs is the p53-mediated pathway. The incubation of PC12 cells, often used as a model of dopaminergic neurons, with SiNPs, caused an upregulation of p21 and GADD45A proteins that resulted in G2/M arrest and induction of apoptosis [65]. The upregulation of p21 and GADD45A proteins, accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase of cell cycle and induction of apoptosis were also observed in primary cultures of rats’ cortical neurons and N9 microglia cells after incubation with SiNPs [81].

Another mechanism that has been proposed to be responsible for adverse effects of nmNPs is alteration in redox balance. Apoptosis triggered by ROS production was proposed as a mechanism of SWNTs and graphene toxicities. ROS generation in PC12 cells treated with graphene layers [113] and SWNTs [114] resulted in the upregulation of caspase 3 apoptosis and was dependent on the PEG coating of nanomaterials. MWNTs were also able to induce alterations in the microenvironment and microstructure of brain tissue associated with NOS and ROS production. After treatment with MWNTs, high expression of nNOS and increased ROS production were observed in rostral ventrolateral medulla and nucleus tractus solitaries—two regions of the brain, which play important roles in the regulation of sympathetic nerve activity [111]. This result was confirmed by Zheng et al. [88] who proved that inhalation of MWNTs significantly alters the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system in rats. An enhanced ROS production and lipid peroxidation were also observed in rat hippocampus after exposure to SWNTs functionalized with PEG [142] and SiNPs [138]. The latter was confirmed by an increase in the expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activity, two enzymes responsible for the removal of ROS [138].

Incubation of microglial BV-2 and N9 cells with MWNTs and single-wall carbon nanohorns resulted in a dose-dependent cell division arrest and apoptosis [86,87]. Similarly, the increase in apoptosis level was reported for neuronal NeuroScreen-1 cells (NS-1) incubated with MWNTs [85] or primary neuronal cells treated with G4-C12 PAMAM dendrimers [25].

Yet, another indirect effect mechanism leading to nmNPs toxicity in CNS-derived cells involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that may led to inflammation in the brain. N9 microglial cells treated with SiNPs produced pro-inflammatory interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and N-terminal fragment of gasdermin D, a marker protein for pyroptosis [81], whereas nanoplastic treatment induced pro-inflammatory response in astrocytes, including the up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-1β [165]. MWNTs caused an increase in TNF-α and IL-1β expression, indicating the pro-inflammatory action of nmNPs inside the brain (in vivo studies). The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines was also reported for shortened-by-oxidation, amino-functionalized MWNT (oxMWNTs-NH3+). Furthermore, oxMWNTs-NH3+ induced the higher-than-long, non-oxidized analog expression of GFAP and CD11b, which points to the more intense glial cell activity and degenerative changes [70]. An increase in the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β was also observed in the striatum of rats treated with SiNPs [65].

nmNPs also affected the functionality of neural cells, such as the differentiation and formation of neurite and dendrites. Treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with ICG/PCL-rhodamine-doped NPs and Si-ICG/PLLA-rhodamine-doped NPs resulted in a significant down-regulation of the expression of differentiation marker MAP-2 [24]. Accordingly, a study by Hollinger et al. [27] showed that incubation of rabbits primary mixed glial cells with 2-PMPA dendrimers triggered up-regulation of transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), which plays an important role in the regulation and differentiation of immune and stem cells. Treatment of primary cultured cortical neurons with increased concentrations of SiNPs resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the number of dendrites. Furthermore, subsequent analysis showed that soma of the neurons collapsed and dendrites disappeared [80]. In line, reduction in the ability to form neurites after NGF stimulation was observed in PC12 cells treated with SiNPs modified with aminopropyltriethoxysilane, likely due to disorder in cytoskeletal structure [65].

The impact of nmNPs on neurotransmitter secretion was described by Wu et al. [65], who showed that exposure of rats to SiNPs caused a decrease in dopamine level in the striatum and in hippocampus. In line tissue, decreased levels of epinephrine, norepinephrine and dopamine was reported in the blood of mice exposed to MWNTs [111]. The negative impact of SiNPs on the functionality of dopaminergic neurons shows that these nmNPs can be a risk factor of neurodegenerative diseases. Further evidence that SiNPs might be at risk of neurodegenerative diseases was delivered by You et al. [137], who reported that phosphorylation Tau protein was significantly increased in the frontal cortex of SiNP exposed mice. It was accompanied by increased phosphorylation of ERK in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) in the frontal cortex. The impairment of Tau protein phosphorylation is associated with neurodegeneration and contributes to the development of Alzheimer disease. The above-mentioned changes were associated with microglia activation and upregulation of pro-inflammatory markers, suggesting that exposure to SiNPs can lead to neuroinflammation that underlies many neurodegenerative disorders. The same work showed the significant impact of SiNP exposure on synapses function and structure. Exocytosis and endocytosis are essential processes in synapse firing, allowing communication to occur between neurons. It was found that exocytosis was significantly impaired in the SiNP-exposed mice in the frontal cortex. However, neither endocytosis nor exocytosis was affected in the hippocampus. Furthermore, after ex vivo exposure of primary cortical neurons to SiNPs, a decrease in the expression of synapsin I and a parallel increase in the expression of synaptophysin were observed, both proteins playing a pivotal role in the proper functioning of synapses.

Finally, nmNPs also affect the behavior of exposed animals. Treatment of mice with SiNPs via intranasal instillation resulted in mood dysfunction and cognitive impairment. Short-term memory and spatial learning, estimated by using a Morris water maze test, were impaired. Furthermore, the mice social interaction activity was decreased after 2 months of NP exposure; however, any symptoms of depression were not detected [137]. On the contrary, Wu et al. [65] reported that intranasal administration of SiNPs for 1 or 7 days did not result in any changes in animals’ behavior or cause histological changes in the brain tissue; however, it should be noted that dose used in this study was relatively low (20 μg/day) and exposition time was shorter, as compared to the study mentioned before. Adverse effects of nmNPs on rodent behavior was confirmed by the study of Dal Bosco et al. [142], who showed that the treatment of rats with SWNTs-PEG caused a significant deficit in the retrieval of fear memory.

6. Adverse Effects of Non-Metallic NPs in Non-Mammalian Organisms

Many types of nmNPs are released into the environment, as a result of their use, and may impact animals living there. Therefore, testing the toxicity of nmNPs on the CNS of higher non-mammalian organisms seems to be crucial for estimating of the environmental risk associated with their use.

Exposure of adult Japanese rice fish (Oryzias latipes) to fluorescent polystyrene NPs for 7 days revealed the presence of particles in the brain, indicating that nanoplastics have the innate capacity to cross the BBB [166]. In line, amino-modified polystyrene nanobeads were more prevalent than similar microparticles in the brain of exposed Crucian carp (Carassius carassius). The presence of polystyrene nano- and microparticles in the brain coincided with alterations in behavioral patterns, decreased brain mass and morphological changes in the cerebral gyri [167]. In line, 15 days of exposure to polyethylene nano- and microplastic caused varying degrees of necrosis, fibrosis, changes in blood capillaries, tissue detachment, edema, degenerated connective tissues, and necrosis in large cerebellar neurons and ganglion cells in the tectum of juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio). The changes were accompanied by a decrease in the activity of acetylcholinesterase (aChE) [168]. The gut–brain axis related toxicity of nanoplastic was recently reviewed, and it is clear that these particles may induce oxidative stress, disturb neurodevelopment, and impact behaviour and immune system activation [165].

The studies performed on bivalves and crustaceans confirmed the neurotoxic effect of nanoplastic. It was shown that nanoplastic can inhibit cholinesterase in the hemolymph of Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis), an enzyme responsible for the breakdown of neurotransmitters [169]. The same effect was observed in brine shrimp (Artemia fransiscana) [170].

Despite nanoplastic, significant lipid peroxidation and GSH depletion were found in the brains of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) after 48 h of exposure to uncoated fullerenes [171]. In line, 21 days exposure of zebrafish (Danio rerio) to fullerenes, short and long MWNTs and SWNTs, caused significant disturbances in lipid, revealed as an elevation of the lipid to protein ratio and in the brain and gills. In addition, a decrease in the level of unsaturated lipids was reported in the brain of fullerene exposed males. In contrast to the result obtained for male zebrafish, the level of unsaturated lipids in the brain in female fish exposed to fullerenes increased [172].

The zebrafish model was also used to study embryonic developmental toxicity of SiNPs. The results revealed persistent changes in larval behavior [173]. In agreement, transcriptomic analysis suggests neurodegeneration and motor dysfunction in larval zebrafish after polystyrene NP treatment. The authors clearly indicate the changes in behavior and physiology, potentially decreasing organismal fitness in contaminated ecosystems [174].

Studies on in vivo toxicity of different types of nmNPs in mammals and non-mammalian organisms are summarized in detail in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 4.

The effect of nmNPs (toxic) in vivo. Non-mammalian species.

7. Conclusions

In the past decade, rapid growth of interest in nanotechnology and increasing use of NPs in commercial applications have been widely observed. In general, despite being similar in shape and size, nmNPs seem to be less toxic than metal nanomaterials. The exact cause of the lesser toxicity of nmNPs over similar metallic ones is not yet explained. It might be speculated that the smaller density of nmNPs, as compared with the metallic ones, affects their interactions with cellular components, such as cell membranes, they might differ in composition and/or behavior to protein corona, or a smaller amount of metal ions is released from the NPs that might contribute to the generation of oxidative stress. Whatever it is needs further investigation; however, the impact of nmNPs on human health should not be disregarded.

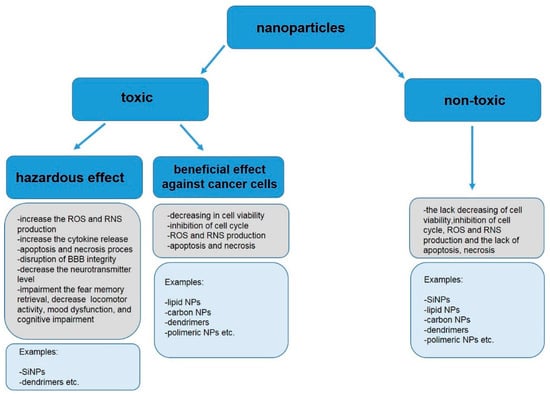

The summary of current knowledge about the toxicity of nmNPs, presented in this study, demonstrates that nmNPs can easily penetrate the animal body, both of terrestrial and aquatic organisms and can be toxic to the CNS in vivo and to CNS-derived cells in vitro. Though a large and diverse group of nmNPs has been engineered and studied, they seem to share common mechanisms of toxicity. Adverse effects of nmNPs are usually associated with the generation of oxidative stress that leads to the malfunction of mitochondria, the activation of different signaling pathways, and subsequent activation of autophagy or apoptosis. Some nmNPs can, however, directly interact with cell membrane proteins, which leads to the activation of ion channel and flux of ion, e.g., calcium, from cellular milieu. The potential effects of nmNPs in the CNS are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Effects of nmNPs in CNS.

8. Limitation of the Study and Future Directions

A general impression of non-metallic nanomaterials’ effects on the CNS after reading this review might be biased by the fact that the review is focused on the adverse effects of nmNPs. Thus, it must be understood that there is also a large number of publications describing little or no effects of nmNPs on the CNS. These publications have been omitted as being beyond the scope of this review. However, while limited toxicity might be a potential benefit of non-metallic nanomaterials, predisposing them to biomedical applications, it should be kept in mind that it can be harmful and there is a need to estimate the risk of its use, especially in medicine and diagnostics. While this review clearly shows a negative impact of nmNPs on the CNS, including mammals and non-mammalian vertebrates, their impact on human health in terms of long-term daily exposure is still unclear. Available data in regard to human exposure are very limited, and it is not possible to draw reliable conclusions. Thus, similar to the recently published report by the European Commission Directorate General for Environment on nanoplastic health impact [184], reporting standards should be developed for various nmNPs, which can penetrate different biological barriers and slip through filters more than other particles. This requires enormous work by nanotechnology scientists to conduct numerous experiments associated with the estimation of toxicity-tested materials. The report should include current quantification and assessment methods, the occurrence of NPs in the environment, their ecotoxicity, and what is most importantly their impacts on human health.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by K.S. (Katarzyna Sikorska), K.B., M.K., L.K.-S., K.S. and M.C. (Magdalena Czajka). The first draft of the manuscript was written by K.S. (Katarzyna Sikorska) and all authors commented on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Centre project No. 2019/35/B/NZ7/04133 “Nanoplastic toxicity: effects on the gut-brain axis” and statutory funding for the Institute of Nuclear Chemistry and Technology (K.S. (Katarzyna Sikorska), K.B. and M.K.), National Science Centre Project No. 2020/39/B/NZ7/03197 “Nanoplastic and silver nanoparticles as a factor modulating the activity of estrogen-dependent intracellular signaling pathways in in vitro and in vivo systems” (M.K. and K.B.), and statutory funding from the Institute of Nuclear Chemistry and Technology (K.S. (Katarzyna Sikorska), K.B. and M.K.)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saeedi, M.; Eslamifar, M.; Khezri, K.; Dizaj, S.M. Applications of nanotechnology in drug delivery to the central nervous system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.W.; Allaker, R.P.; Reip, P.; Oxford, J.; Ahmad, Z.; Ren, G. A review of nanoparticle functionality and toxicity on the central nervous system. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cheng, J.; He, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Song, Q.; Hou, Y.; Gan, Z. Cell membrane-based nanomaterials for theranostics of central nervous system diseases. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhator, C.; Qureshi, M.Q.; Zuberi, A.W.; Hussain, M.; Sangroula, N.; Yerra, S.; Devi, M.; Arsal Naseem, M.; Bellegarde, S.B.; Pendyala, P.R. Advances and Opportunities in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery for Central Nervous System Disorders: A Review of Current Advances. Cureus 2023, 15, e44302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, M.; He, J.; Gong, M.; Sun, J.; Yang, X. Central nervous system injury meets nanoceria: Opportunities and challenges. Regen. Biomater. 2022, 9, rbac037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annu Sartaj, A.; Qamar, Z.; Md, S.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Baboota, S.; Ali, J. An Insight to Brain Targeting Utilizing Polymeric Nanoparticles: Effective Treatment Modalities for Neurological Disorders and Brain Tumor. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 788128. [Google Scholar]

- Montegiove, N.; Calzoni, E.; Emiliani, C.; Cesaretti, A. Biopolymer Nanoparticles for Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery: A New Promising Approach for the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athira, S.S.; Prajitha, N.; Mohanan, P.V. Interaction of nanoparticles with central nervous system and its consequences. Am. J Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 4, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolà, A.; Visalli, G.; La Maestra, S.; Ceccarelli, M.; D’Aleo, F.; Nunnari, G.; Pellicanò, G.F.; Di Pietro, A. Carbon nanotubes and central nervous system: Environmental risks, toxicological aspects and future perspectives. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 65, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, S.; Islam Aqib, A.; Muneer, A.; Fatima, M.; Atta, K.; Kausar, T.; Zaheer, C.-N.F.; Ahmad, I.; Saeed, M.; Shafique, A. Insights into nanoparticles-induced neurotoxicity and cope up strategies. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1127460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, K.; Czajka, M.; Matysiak-Kucharek, M.; Fal, B.; Drop, B.; Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Sikorska, K.; Kruszewski, M.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L. Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrighi, M.; Trusel, M.; Tonini, R.; Giordani, S. Carbon Nanomaterials Interfacing with Neurons: An In vivo Perspective. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and Toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sigdel, G.; Mintz, K.J.; Seven, E.S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Leblanc, R.M. Carbon Dots: A Future Blood–Brain Barrier Penetrating Nanomedicine and Drug Nanocarrier. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 5003–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, A.; Majkowska-Marzec, B. Whether Carbon Nanotubes Are Capable, Promising, and Safe for Their Application in Nervous System Regeneration. Some Critical Remarks and Research Strategies. Coatings 2022, 12, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauro, R.; Nandave, M.; Jain, V.K.; Jain, K. Advances in dendrimer-mediated targeted drug delivery to the brain. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2021, 23, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masserini, M. Nanoparticles for brain drug delivery. ISRN Biochem. 2013, 2013, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Barres, B.A. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussy, C.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Boczkowski, J.; Lanone, S.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A.; Kostarelos, K. Microglia Determine Brain Region-Specific Neurotoxic Responses to Chemically Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2015, 9, 7815–7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussy, C.; Hadad, C.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A.; Kostarelos, K. Intracellular degradation of chemically functionalized carbon nanotubes using a long-term primary microglial culture model. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateb, B.; Van Handel, M.; Zhang, L.; Bronikowski, M.J.; Manohara, H.; Badiea, B. Internalization of MWCNTs by microglia: Possible application in immunotherapy of brain tumors. NeuroImage 2007, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, A.E.; Gonzalez Carter, D.A.; Motskin, M.; Pienaar, I.S.; Chen, S.; Hu, S.; Ruenraroengsak, P.; Ryan, M.P.; Shaffer, M.S.P.; Dexter, D.T.; et al. High resolution and dynamic imaging of biopersistence and bioreactivity of extra and intracellular MWNTs exposed to microglial cells. Biomaterials 2015, 70, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Zheng, Q.; Katz, H.E.; Guilarte, T.R. Silica-Based Nanoparticle Uptake and Cellular Response by Primary Microglia. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducray, A.D.; Stojiljkovic, A.; Möller, A.; Stoffel, M.H.; Widmer, H.R.; Frenz, M.; Mevissen, M. Uptake of silica nanoparticles in the brain and effects on neuronal differentiation using different in vitro models. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertazzi, L.; Gherardini, L.; Brondi, M.; Sato, S.S.; Bifone, A.; Pizzorusso, T.; Ratto, G.M.; Bardi, G. In Vivo Distribution and Toxicity of PAMAM Dendrimers in the Central Nervous System Depend on Their Surface Chemistry. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Navath, R.S.; Balakrishnan, B.; Guru, B.R.; Mishra, M.K.; Romero, R.; Kannan, R.M.; Kannan, S. Intrinsic targeting of inflammatory cells in the brain by polyamidoamine dendrimers upon subarachnoid administration. Nanomedicine 2010, 5, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, K.; Sharma, A.; Tallon, C.; Lovell, L.; Thomas, A.G.; Zhu, X.; Kambhampati, S.P.; Liaw, K.; Sharma, R.; Rojas, C.; et al. Microglia-targeted dendrimer-2PMPA therapy robustly inhibits GCPII and improves cognition in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. bioRxiv 2020. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, A.J.; Oliveira, J.M.; Pirraco, R.P.; Pereira, V.H.; Fraga, J.S.; Marques, A.P.; Neves, N.M.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L.; Sousa, N. Carboxymethylchitosan/Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimer Nanoparticles in Central Nervous Systems-Regenerative Medicine: Effects on Neuron/Glial Cell Viability and Internalization Efficiency. Macromol. Biosci. 2010, 10, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Nance, E.; Alnasser, Y.; Kannan, R.; Kannan, S. Microglial migration and interactions with dendrimer nanoparticles are altered in the presence of neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Magruder, J.T.; Lin, Y.A.; Crawford, T.C.; Grimm, J.C.; Sciortino, C.M.; Wilson, M.A.; Blue, M.E.; Kannan, S.; Johnston, M.V.; et al. Generation-6 hydroxyl PAMAM dendrimers improve CNS penetration from intravenous administration in a large animal brain injury model. J. Control. Release 2017, 10, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, R.; Fusco, R.; Cuzzocrea, S. Astrocytes: Role and Functions in Brain Pathologies. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafa, H.; Wang, J.T.W.; Rubio, N.; Venner, K.; Anderson, G.; Pach, E.; Ballesteros, B.; Preston, J.E.; Abbott, N.J.; Al-Jamal, K.T. The interaction of carbon nanotubes with an in vitro blood-brain barrier model and mouse brain in vivo. Biomaterials 2015, 53, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, H.; Sun, B.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, D.; Li, X. Enhanced Neuroprotective Effects of Resveratrol Delivered by Nanoparticles on Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress in Rat Cortical Cell Culture. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 2045–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, R.; Belletti, D.; Pederzoli, F.; Masoni, M.; Keller, J.; Ballestrazzi, A.; Vandelli, M.A.; Tosi, G.; Grabrucker, A.M. Novel Curcumin loaded nanoparticles engineered for Blood-Brain Barrier crossing and able to disrupt A-beta aggregates. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 30, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Fang, W.; Chen, X.; Liao, W.; Jing, X.; Lei, M.; Tao, E.; Ma, Q.; et al. Curcumin-loaded PLGA-PEG nanoparticles conjugated with B6 peptide for potential use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, C.H.; Han, J.; Han, X.L.; Zhuang, H.J.; Zhao, Z.M. Preparation and characterization of the Adriamycin loaded amphiphilic chitosan nanoparticles and their application in the treatment of liver cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 17, 7833–7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, Y.A.; Kao, C.W.; Liu, K.K.; Huang, H.S.; Chiang, M.H.; Soo, C.R.; Chang, H.C.; Chiu, T.W.; Chao, J.I.; Hwang, E. The effect of fluorescent nanodiamonds on neuronal survival and morphogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Kurokawa, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Win-Shwe, T.T.; Nansai, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sone, H. Effects of Polyamidoamine Dendrimers on a 3-D Neurosphere System Using Human Neural Progenitor Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2016, 152, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyitrai, G.; Héja, L.; Jablonkai, I.; Pál, I.; Visy, J.; Kardos, J. Polyamidoamine dendrimer impairs mitochondrial oxidation in brain tissue. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatovic, S.M.; Keep, R.F.; Andjelkovic, A.V. Brain Endothelial Cell-Cell Junctions: How to “Open” the Blood Brain Barrier. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2008, 6, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lin, B.; Shao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Ji, T.; Yang, C. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies on the Transport of PEGylated Silica Nanoparticles across the Blood–Brain Barrier. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 2131–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Raghnaill, M.N.; Bramini, M.; Mahon, E.; Aberg, C.; Salvati, A.; Dawson, K.A. Nanoparticle accumulation and transcytosis in brain endothelial cell layers. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 11153–11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, S.V.; Batrakova, E.V.; Kabanov, A.V. Nanogels for Oligonucleotide Delivery to the Brain. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004, 15, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, F.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Ge, C.; Qu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Han, D.; Chen, C. Fullerene Nanoparticles Selectively Enter Oxidation-Damaged Cerebral Microvessel Endothelial Cells and Inhibit JNK Related Apoptosis. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3358–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Arendonk, K.J.; Chung, D.H. Neuroblastoma: Tumor Biology and Its Implications for Staging and Treatment. Children 2019, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bettegowda, C. Genomic discoveries in adult astrocytoma. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015, 30, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungare, S.; Hallam, K.; Badhan, R.K.S. Phytochemical-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles for nose-to-brain olfactory drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 20, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollimpelli, V.S.; Kumar, P.; Kumari, S.; Kondapi, A.K. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin-loaded lactoferrin nano particles against rotenone induced neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 95, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paka, G.D.; Doggui, S.; Zaghmi, A.; Safar, R.; Dao, L.; Reisch, A.; Klymchenko, A.; Roullin, V.G.; Joubert, O.; Ramassamy, C. Neuronal Uptake and Neuroprotective Properties of Curcumin- Loaded Nanoparticles on SK-N-SH Cell Line: Role of Poly(lactide-coglycolide) Polymeric Matrix Composition. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Witkowski, C.M.; Craig, M.M.; Greenwade, M.M.; Joseph, K.L. Cytotoxicity Effects of Different Surfactant Molecules Conjugated to Carbon Nanotubes on Human Astrocytoma Cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listik, E. Development and optimization of G-1 polymeric nanoparticulated and liposomal systems for central nervous system applications. Neurol. Disord. Therap. 2018, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B. Publication Landscape Analysis on Gliomas: How Much Has Been Done in the Past 25 Years? Front. Oncol. 2020, 9, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Rattan, R.; Majoros, I.J.; Mullen, D.G.; Peters, J.L.; Shi, X.; Bielinska, A.U.; Blanco, L.; Orr, B.O.; Baker, J.R., Jr.; et al. The Role of Ganglioside GM1 in Cellular Internalization Mechanisms of Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009, 19, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vijayakumar, M.R.; Vajanthri, K.Y.; Balavigneswaran, C.K.; Mahto, S.K.; Mishra, N.; Muthu, M.S.; Singh, S. Pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, in vitro cytotoxicity andbiocompatibility of Vitamin E TPGS coated trans resveratrol liposomes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 145, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Jiang, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, Q.; You, Y.; Fu, Z. Enhanced growth inhibition effect of Resveratrol incorporated into biodegradable nanoparticles against glioma cells is mediated by the induction of intracellular reactive oxygen species levels. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2009, 72, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Asghar, S.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Ping, Q.; Xiao, Y. Lactoferrin-coated polysaccharide nanoparticles based on chitosanhydrochloride/hyaluronic acid/PEG for treating brain glioma. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, A.; Ni, L.; Yan, X.; Song, Y.; Zhao, M.; Sun, K.; Mu, H.; Liu, S.; Wu, Z.; et al. Nose-to-brain delivery of temozolomide-loaded PLGA nanoparticles functionalized with anti-EPHA3 for glioblastoma targeting. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.W.; Feng, S.S. Transferrin-conjugated nanoparticles of Poly(lactide)-D-a-Tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate diblock copolymer for targeted drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7748–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, M.R.; Kosuru, R.; Singh, S.K.; Prasad, C.B.; Narayan, G.; Muthua, M.S.; Singh, S. Resveratrol loaded PLGA:D-a-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate blend nanoparticles for brain cancer therapy. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 74254–74268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Gao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ling, C.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Qin, J.; Wang, J.; Lu, W.; Wang, J. Natural Brain Penetration Enhancer-Modified Albumin Nanoparticles for Glioma Targeting Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 30201–30213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceña, V.; Játiva, P. Nanoparticle crossing of blood–brain barrier: A road to new therapeutic approaches to central nervous system diseases. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Auriat, A.; Koudrina, A.; DeRosa, M.; Cao, X.; Tsai, E.C. Nano-engineering Nanoparticles for Clinical Use in the Central Nervous System: Clinically Applicable Nanoparticles and Their Potential Uses in the Diagnosis and Treatment of CNS Aliments. In Nanoengineering Materials for Biomedical Uses; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.T.; Guo, W.; Lin, Y.; Deng, X.Y.; Wang, H.F.; Sun, H.F.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, M.; et al. Biodistribution of Pristine Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes In Vivo. J. Phys. Chem. 2007, 111, 17761–17764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.Z.; Hu, K.L.; Jiang, X.G.; Fu, S.K. Cationic albumin conjugated pegylated nanoparticles as novel drug carrier for brain delivery. J. Control. Release 2005, 107, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, J.; Xue, J. Neurotoxicity of Silica Nanoparticles: Brain Localization and Dopaminergic Neurons Damage Pathways. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4476–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffie, R.M.; Farrar, C.T.; Saidi, L.J.; William, C.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Spires-Jones, T.L. Nanoparticles enhance brain delivery of blood–brain barrier-impermeable probes for in vivo optical and magnetic resonance imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18837–18842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zensi, A.; Begley, D.; Pontikis, C.; Legros, C.; Mihoreanu, L.; Wagner, S.; Büchel, C.; von Briesen, H.; Kreuter, J. Albumin nanoparticles targeted with Apo E enter the CNS by transcytosis and are delivered to neurons. J. Control. Release 2009, 137, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, C. Development of PLGA-lipid nanoparticles with covalently conjugated indocyanine green as a versatile nanoplatform for tumor-targeted imaging and drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 5807–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xie, C.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y. Specific role of polysorbate 80 coating on the targeting of nanoparticles to the brain. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3065–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, G.; Nunes, A.; Gherardini, L.; Bates, K.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Gaillard, C.; Kostarelos, K. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes in the Brain: Cellular Internalization and Neuroinflammatory Responses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlo, K.; Blackburn, K.L.; Clark, E.D.; Grothaus, J.; Chaney, J.; Neu, S.; Flood, J.; Abbott, D.; Bohne, C.; Casey, K.; et al. Tissue distribution of 20nm, 100 nm and 1000 nm fluorescent polystyrene latex nanospheres following acute systemic or acute and repeat airway exposure in the rat. Toxicology 2009, 263, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafa, H.; Wang, J.T.W.; Rubio, N.; Klippstein, R.; Costa, P.M.; Hassan, H.A.F.M.; Sosabowski, J.K.; Bansal, S.S.; Preston, J.E.; Abbott, N.J.; et al. Translocation of LRP1 targeted carbon nanotubes of different diameters across the blood–brain barrier in vitro and in vivo. J. Control. Release 2016, 225, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.; Jain, A.; Jain, S.K. Transferrin-conjugated solid lipid nanoparticles for enhanced delivery of quinine dihydrochloride to the brain. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, F.; Fricker, G. Liposomal Conjugates for Drug Delivery to the Central Nervous System. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Gao, H.; Chen, J.; Shen, S.; Zhang, B.; Ren, J.; Guo, L.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, X.; Mei, H. Intracellular delivery mechanism and brain delivery kinetics of biodegradable cationic bovine serum albumin-conjugated polymersomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 3421–3432. [Google Scholar]

- Lozić, I.; Hartz, R.V.; Bartlett, C.A.; Shaw, J.A.; Archer, M.; Naidu, P.S.R.; Smith, N.M.; Dunlop, S.A.; Swaminathan Iyer, K.; Kilburn, M.R.; et al. Enabling dual cellular destinations of polymeric nanoparticles for treatment following partial injury to the central nervous system. Biomaterials 2016, 74, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kawashima, Y.; Kreuter, J.; Yamamoto, H. Brain targeting with surface-modified poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles delivered via carotid artery administration. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 77, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Gouritin, B.; Chacun, H.; Desmaele, D.; D’Angelo, J.; Noel, J.P.; Georgin, D.; Fattal, E.; Andreux, J.P.; Couvreur, P. Long-Circulating PEGylated Polycyanoacrylate Nanoparticles as New Drug Carrier for Brain Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, E.; Zhang, C.; Shih, T.Y.; Xu, Q.; Schuster, B.S.; Hanes, J. Brain-Penetrating Nanoparticles Improve Paclitaxel Efficacy in Malignant Glioma Following Local Administration. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10655–10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Ezure, H.; Ito, J.; Sawa, C.; Yamamoto, M.; Hata, H.; Moriyama, H.; Manome, Y.; Otsuka, N. Effect of Silica Nanoparticles on Cultured Central Nervous System Cells. J. Neurosci. 2018, 8, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Ge, D.; Mirshafiee, V.; Chen, C.; Li, M.; Xue, C.; Ma, X.; Sun, B. Assessment of neurotoxicity induced by differentsized Stöber silica nanoparticles: Induction of pyroptosis in microglia. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 12965–12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, A.; Ducray, A.D.; Widmer, H.R.; Stoffel, M.H.; Mevissen, M. Effects of gold and PCL- or PLLA-coated silica nanoparticles on brain endothelial cells and the blood–brain barrier. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardino, A.; Catalano, F.; Ruffinatti, F.A.; Alberto, G.; Nilius, B.; Antoniotti, S.; Martra, G.; Lovisolo, D. Interaction of SiO2 nanoparticles with neuronal cells: Ionic mechanisms involved in the perturbation of calcium homeostasis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 66, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yang, Y.; Xia, D.; Meng, L.; He, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z. Silica Nanoparticles Promote α-Synuclein Aggregation and Parkinson’s Disease Pathology. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 807988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Yeyeodu, S.; Gilyazova, N.; Witherspoon, S.; Ibeanu, G. Effects of Carbon Nanotubes on a Neuronal Cell Model In Vitro. J. Biol. 2011, 1, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, J.C.; Álvarez-Montes, L.; Rodríguez-Fernández, L.; González, J.; Valiente, R.; Fanarraga, M.L. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Hinder Microglia Function Interfering with Cell Migration and Phagocytosis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2014, 3, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, L.; Yang, Y.; Chang, T.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, G.; Cao, Y.; et al. Single-wall carbon nanohorns inhibited activation of microglia induced by lipopolysaccharide through blocking of Sirt3. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; McKinney, W.; Kashon, M.; Salmen, R.; Castranova, V.; Kan, H. The influence of inhaled multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the autonomic nervous system. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2016, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaszewska, A.; Ciolkowski, M.; Wróbel, D.; Petersen, J.F.; Ficker, M.; Christensen, J.B.; Bryszewska, M.; Klajnert, B. Modified PAMAM dendrimer with 4-carbomethoxypyrrolidone surface groups reveals negligible toxicity against three rodent cell-lines. Nanomedicine 2013, 9, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serramía, M.J.; Álvarez, S.; Fuentes-Paniagua, E.; Clemente, M.I.; Sánchez-Nieves, J.; Gómez, R.; de la Mata, J.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.A. In vivo delivery of siRNA to the brain by carbosilane dendrimer. J. Control. Release 2015, 200, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.J.; Fernandes, C.; Martins, S.; Borges, F.; Sarmento, B. Tailoring Lipid and Polymeric Nanoparticles as siRNA Carriers towards the Blood-Brain Barrier—From Targeting to Safe Administration. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017, 12, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastorakos, P.; Zhang, C.; Berry, S.; Oh, Y.; Lee, S.; Eberhart, C.H.; Woodworth, G.F.; Suk, J.S.; Hanes, J. Highly PEGylated DNA Nanoparticles Provide Uniform and Widespread Gene Transfer in the Brain. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.; Kenesei, K.; Li, Y.; Demeter, K.; Környei, Z.; Madarász, E. Uptake and bioreactivity of polystyrene nanoparticles is affected by surface modifications, ageing and LPS adsorption: In vitro studies on neural tissue cells. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 4199–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.K.; Han, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Bae, J.S.; Choi, J.; Ryu, K.Y. Neurotoxic potential of polystyrene nanoplastics in primary cells originating from mouse brain. NeuroToxicology 2020, 81, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Du, D.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Dutta, P.; Lin, Y. In Vitro Study of Receptor-Mediated Silica Nanoparticles Delivery across Blood–Brain Barrier. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 20410–20416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghirov, H.; Karaman, D.; Viitala, T.; Duchanoy, A.; Lou, Y.R.; Mamaeva, V.; Rosenholm, J.M. Feasibility Study of the Permeability and Uptake of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles across the Blood- Brain Barrier. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, G.; Tognini, P.; Ciofani, G.; Raffa, V.; Costa, M.; Pizzorusso, T. Pluronic-coated carbon nanotubes do not induce degeneration of cortical neurons in vivo and in vitro. Nanomedicine 2009, 5, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Song, Q.; Su, R.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, T.; Liu, L.; Jin, G.; Tang, M.; Cheng, G. The promotion of neurite sprouting and outgrowth of mouse hippocampal cells in culture by graphene substrates. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9374–9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojo, M.; Cerqueira, S.R.; Mota, T.; Xavier-Magalhães, A.; Ribeiro-Samy, S.; Mano, J.F.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L.; Sousa, N.; Costa, B.M.; et al. In vitro evaluation of the cytotoxicity and cellular uptake of CMCht/PAMAM dendrimer nanoparticles by glioblastoma cell models. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.K.; Agarwal, S.; Seth, B.; Yadav, A.; Nair, S.; Bhatnagar, P.; Karmakar, M.; Kumari, M.; Chauhan, L.K.S.; Patel, D.K.; et al. Curcumin-Loaded Nanoparticles Potently Induce Adult Neurogenesis and Reverse Cognitive Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease Model via Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, L.; Fan, L.; Zha, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Pang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Targeting the brain with PEG-PLGA nanoparticles modified with phage-displayed peptides. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 4943–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Cai, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Song, Y.; Du, D.; Dutta, P.; Lin, Y. Synthetic Polymer Nanoparticles Functionalized with Different Ligands for Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis across the Blood–Brain Barrier. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.R.; Ho, P.C. Role of serum albumin as a nanoparticulate carrier for nose-to-brain delivery of R-flurbiprofen: Implications for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 70, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wei, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Ren, L. In vitro and in vivo studies on gelatin-siloxane nanoparticles conjugated with SynB peptide to increase drug delivery to the brain. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, K.E.; Heejoon, M. Cytotoxic Effects of Nanoparticles Assessed In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.R.; Du, J.; Ying, X.; Lu, W.L.; Lou, J.N.; Wei, Y. PEGylated Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-based dual-targeting carrier for treating brain tumors. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liaw, K.; Kambhampati, S.P.; Porterfield, J.E.; Lin, K.C.; DeRidder, L.B.; Kannan, S.; Kannan, R.M. Dense hydroxyl polyethylene glycol dendrimer targets activated glia in multiple CNS disorders. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, P.; Kim, B.; Ramalaingam, P.; Karthivashan, G.; Revuri, V.; Park, S.; Kim, J.S.; Ko, Y.T.; Choi, D.K. Antineuroinflammatory Activities and Neurotoxicological Assessment of Curcumin Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles on LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia Cell Models. Molecules 2019, 24, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Sun, Y.; Song, P.; Ju, D. The role of autophagy in the neurotoxicity of cationic PAMAM Dendrimers. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 7588–7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Alizadeh, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Farrukh, O.; Manuel, E.; Diamond, D.J.; Badie, B. Carbon Nanotubes Enhance CpG Uptake and Potentiate Anti-Glioma Immunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhong, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Gong, N.; Wang, Y.; Cai, J.; Liang, X.J. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Induced Hypotension by Regulating the Central Nervous System. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittorio, O.; Raffa, V.; Cuschieri, A. Influence of purity and surface oxidation on cytotoxicity of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with human neuroblastoma cells. Nanomedicine 2009, 5, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ali, S.F.; Dervishi, E.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Casciano, D.; Biris, A.S. Cytotoxicity Effects of Graphene and Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Neural Phaeochromocytoma-Derived PC12 Cells. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3181–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, T.; Lantz, S.M.; Howard, P.C.; Paule, M.G.; Slikker, W.; Watanabe, F.; Mustafa, T.; et al. Mechanistic Toxicity Evaluation of Uncoated and PEGylated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Neuronal PC12 Cells. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7020–7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.W.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.H.; Hwang, E.J.; Hwang, Y.S.; Lee, M.H.; Han, D.W.; Park, J.C. Enhanced Neural Cell Adhesion and Neurite Outgrowth on Graphene-Based Biomimetic Substrates. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 212149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athira, S.S.; Biby, T.E.; Mohanan, P.V. Effect of polymer functionalized fullerene soot on C6 glial cells. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 127, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, C.L.; Sparks, S.M.; Uhrich, K.E.; Roth, C.M. Acetylation of PAMAM dendrimers for cellular delivery of siRNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2009, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, J.; Posadas, I.; Játiva, P.; Bugaj- Zarebska, M.; Urbanczyk-Lipkowska, Z.; Ceña, V. Second Generation Amphiphilic Poly-Lysine Dendrons Inhibit Glioblastoma Cell Proliferation without Toxicity for Neurons or Astrocytes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, M.R.; Kumari, L.; Patel, K.K.; Vuddanda, P.R.; Vajanthri, K.Y.; Mahtoc, S.K.; Singh, S. Intravenous administration of trans-resveratrol loaded TPGS-coated solid lipid nanoparticles for prolonged systemic circulation, passive brain targeting and improved in vitro cytotoxicity against C6 glioma cell lines. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 50336–50348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.Y.; Zhang, P.L.; Zhou, J.L.; Liu, B. Preparation of N, N, N-trimethyl chitosan-functionalized retinoic acid-loaded lipid nanoparticles for enhanced drug delivery to glioblastoma. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, A.; Deshpande, P.; Pattni, B.; Torchilin, V. Transferrin-targeted, resveratrol-loaded liposomes for the treatment of glioblastoma. J. Control Release. 2018, 10, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delalat, B.; Sheppard, V.C.; Ghaemi, S.R.; Rao, S.; Prestidge, C.A.; McPhee, G.; Rogers, M.L.; Donoghue, J.F.; Pillay, V.; Johns, T.G.; et al. Targeted drug delivery using genetically engineered diatom biosilica. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Sun, C.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Jiang, T.Y.; Wang, S.L. Trimethylated chitosan-conjugated PLGA nanoparticles for the delivery of drugs to the brain. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gao, X.; Su, L.; Xia, H.; Gu, G.; Pang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Yao, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, H. Aptamer-functionalized PEG-PLGA nanoparticles for enhanced anti-glioma drug delivery. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 8010–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.J.; Bisht, S.; Bar, E.E.; Maitra, A.; Eberhart, C.G. A polymeric nanoparticle formulation of curcumin inhibits growth, clonogenicity and stem-like fraction in malignant brain tumors. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammam, S.N.; Azzazy, H.M.E.; Lamprecht, A. Nuclear and cytoplasmic delivery of lactoferrin in glioma using chitosan nanoparticles: Cellular location dependent-action of lactoferrin. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 129, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejat, H.; Rabiee, M.; Varshochian, R.; Tahriri, M.; Jazayeri, H.E.; Rajadas, J.; Ye, H.; Cui, Z.; Tayebi, L. Preparation and characterization of cardamom extract-loaded gelatin nanoparticles as effective targeted drug delivery system to treat glioblastoma. React. Funct. Polym. 2017, 120, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Xie, W.; Zhao, P.; Liu, J. Ultrasound-Excited Protoporphyrin IX-Modified Multifunctional Nanoparticles as a Strong Inhibitor of Tau Phosphorylation and β-Amyloid Aggregation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 32965–32980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.A.; Henry, J.E.; Good, T.A. Attenuation of β-amyloid induced toxicity by sialic acidconjugated dendrimers: Role of sialic acid attachment. Brain Res. 2007, 3, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.C.; Tsai, H.C. Rosmarinic acid- and curcumin-loaded polyacrylamide-cardiolipin-poly (lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles with conjugated 83-14 monoclonal antibody to protect β-amyloid-insulted neurons. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 91, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, A.M.; Cardoso, I.; Saraiva, M.J.; Tauer, K.; Pereira, M.K.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Möhwald, H.; Brezesinski, G. Randomization of Amyloid-b-Peptide(1-42)Conformation by Sulfonated and SulfatedNanoparticles Reduces Aggregation and Cytotoxicity. Macromol. Biosci. 2010, 10, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, R.; Ren, Y.; Lee, J.; Braunstein, K.E.; Mao, H.Q.; Wong, P.C. Intraventricular Delivery of siRNA Nanoparticles to the Central Nervous System. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2015, 4, e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotoarisoa, M.; Angelov, B.; Garamus, V.M.; Angelova, A. Curcumin- and Fish Oil-Loaded Spongosome and Cubosome Nanoparticles with Neuroprotective Potential against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Differentiated Human SH-SY5Y Cells. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 3061–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Ghormade, V.; Kolge, H.; Paknikar, K.M. Dual effect of chitosan-based nanoparticles on the inhibition of b-amyloid peptide aggregation and disintegration of the preformed fibrils. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 3362–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookhaklari, R.; Geramizadeh, B.; Abkar, M.; Moosavi, M. The neuroprotective effect of BSA-based nanocurcumin against 6-OHDA-induced cell death in SH-SY5Y cells. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2019, 9, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mulik, R.S.; Mönkkönen, J.; Juvonen, R.O.; Mahadik, K.R.; Paradkar, A.R. ApoE3 Mediated Poly(butyl) Cyanoacrylate Nanoparticles Containing Curcumin: Study of Enhanced Activity of Curcumin against Beta Amyloid Induced Cytotoxicity Using In Vitro Cell Culture Model. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, R.; Ho, Y.S.; Hung, C.H.L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.X.; Chan, H.N.; Ho, S.L.; Lui, S.Y.; Li, H.W.; Chang, R.C.C. Silica nanoparticles induce neurodegeneration-like changes in behavior, neuropathology, and affect synapse through MAPK activation. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çömelekoğlu, Ü.; Ball, E.; Yalın, S.; Eroğlu, P.; Bayrak, G.; Yaman, S.; Söğüt, F. Effects of different sizes silica nanoparticle on the liver, kidney and brain in rats: Biochemical and histopathological evaluation. J. Res. Pharm. 2019, 23, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Qin, Z.; Tao, X.; Zhu, X.; Song, E.; Chen, C.; Chun Ke, P.; Leong, D.T.; et al. Brain Accumulation and Toxicity Profiles of Silica Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size and Exposure Route. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 8319–8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, M.K.; Langeh, R.; Anuradha, J.; Sanjeevani, R.; Sanjeevi, R.; Tripathi, S.; Chauhan, D.S. Silica Nanoparticles Induced Oxidative Stress in Different Brain Regions of Male Albino Rats. Sch. Acad. J. Biosci. 2021, 9, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, M.J.; Topper, L.; Tyler, C.R.; Sanchez, B.; Zychowski, K.; Young, T.; Herbert, G.; Hall, P.; Erdely, A.; Eye, T.; et al. Serum-borne bioactivity caused by pulmonary multiwalled carbon nanotubes induces neuroinflammation via blood–brain barrier impairment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 21, E1968–E1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bosco, L.; Weber, G.E.B.; Parfitt, G.M.; Paese, K.; Gonçalves, C.O.F.; Serodre, T.M.; Furtado, C.A.; Santos, A.P.; Monserrat, J.M.; Barros, D.M. PEGylated Carbon Nanotubes Impair Retrieval of Contextual Fear Memory and Alter Oxidative Stress Parameters in the Rat Hippocampus. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.L.; Gao, J.Q. Brain Localization and Neurotoxicity Evaluation of Polysorbate 80-Modified Chitosan Nanoparticles in Rats. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, J.C.; Fenart, L.; Chauvet, R.; Pariat, C.; Cecchelli, R.; Couet, W. Indirect evidence that drug-brain targeting using Polysorbate 80-coated Polybutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles is related to toxicity. Pharm. Res. 1999, 16, 1836–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Dou, J.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, X. Bioeffects of Inhaled Nanoplastics on Neurons and Alteration of Animal Behaviors through Deposition in the Brain. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Handel, M.; Alizadeh, D.; Zhang, L.; Kateb, B.; Bronikowski, M.; Manohara, H.; Badie, B. Selective uptake of multi-walled carbon nanotubes by tumor macrophages in a murine glioma model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009, 208, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, W.; Yan, B. The effect of multiwalled carbon nanotube agglomeration on their accumulation in and damage to organs in mice. Carbon 2009, 47, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamago, S.; Tokuyama, H.; Nakamuralr, E.; Kikuchi, K.; Kananishl, S.; Sueki, K.; Nakahara, H.; Enomoto, S.; Ambe, F. In vivo biological behavior of a water-miscible fullerene:14C labeling, absorption, distribution, excretion and acute toxicity. Chem. Biol. 1995, 2, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shytikov, D.; Shytikova, I.; Rohila, D.; Kulaga, A.; Dubiley, T.; Pishel, I. Effect of Long-Term Treatment with C60 Fullerenes on the Lifespan and Health Status of CBA/Ca Mice. Rejuv. Res. 2021, 24, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]