Abstract

The hot deformation behaviors of a Ti46Al2Cr2Nb alloy were investigated at strain rates of 0.001–0.1 s−1 and temperatures of 910–1060 °C. Under given deformation conditions, the activation energy of the TiAl alloy could be estimated as 319 kJ/mol. The experimental results were predicted by different predictive models including three constitutive models and three data-driven models. The most accurate data-driven model and constitutive model were an artificial neural network (ANN) and an Arrhenius type strain-compensated Sellars (SCS) model, respectively. In addition, the generalization capability of ANN model and SCS model was examined under different deformation conditions. Under known deformation conditions, the ANN model could accurately predict the flow stress of TiAl alloys at interpolated and extrapolated strains with a coefficient of determination (R2) greater than 0.98, while the R2 value of the SCS model was smaller than 0.5 at extrapolated strains. However, both ANN and SCS models performed poorly under new deformation conditions. A hybrid model based on the SCS model and ANN predictions was shown to have a wider generalization capability. The present work provides a comprehensive study on how to choose a predictive model for the flow stress of TiAl alloys under different conditions.

1. Introduction

TiAl based alloys are elevated-temperature structural materials with a high specific strength, great specific modulus, good creep resistance, outstanding elevated temperature strength, and great oxidation resistance [1,2,3,4]. TiAl alloys are potential materials in automotive and aerospace industries due to the aforementioned excellent properties [5,6]. However, the hot workability of TiAl alloys is limited, which inhibits them from being broadly employed for desirable applications [7,8,9]. Understanding the hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys is critical to define optimal thermomechanical processing conditions within the limitation of workability. Therefore, many efforts have been put into constructing predictive models for the hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys [7,10,11,12,13].

In the past decades, the hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys and other alloys at elevated temperatures have been examined, and predictive constitutive models have been developed on the basis of these investigations [14,15]. For instance, Kong et al. [11] employed the Arrhenius type constitutive model to predict the peak stress of Ti-48Al-2Cr-4Nb-0.2Y alloys under deformation temperatures of 1100–1250 °C at strain rates of 0.01–1 s−1, which suggested the optimal processing temperature and strain rate in the range of 1200–1230 °C and 0.01–0.05 s−1, respectively. Cheng et al. [10] proposed a constitutive model involving different softening mechanisms, and the resulting predictive model could give an accurate estimate of the flow stress of a high-Nb-containing TiAl alloy. Sun et al. [16] examined and described the hot-deformation behaviors of powder metallurgy (PM) TiAl alloys with the Arrhenius type model. They found that the PM TiAl alloy exhibited some flow instability at strain rates higher than 0.01 s−1, indicating that the processing strain rate should be slower than 0.01 s−1.

Recently, more and more date-driven models such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) [17,18,19], support vector machines (SVMs) [20], random forests (RFs) [21], and Gaussian process regressors (GPRs) [22] have been developed to predict the hot-deformation behaviors of alloys with the development of machine learning techniques. Ge et al. [17] utilized the ANN model and Arrhenius type model to predict the hot-deformation behavior of a high-Nb-containing TiAl alloy with β + γ phases. Their results revealed that ANN models were more accurate than Arrhenius type models in predicting the hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys. However, most of the predictive models proposed have been based on the Arrhenius type model and ANN model. The performance of other constitutive models and data-driven models have rarely been reported. A comprehensive comparison of different predictive models is needed. In addition, the generalization capabilities of the predictive models have only been examined under known deformation conditions, and the performance of predictive models under unknown deformation conditions should be investigated as well. Furthermore, the combination of ML model and mechanism-based constitutive models has not been considered in previous work.

In the present work, the hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys at strain rates of 0.001–0.1 s−1 and temperatures of 910–1060 °C were examined. The experimental results were predicted via three constitutive models and three machine learning (ML)-based models. The prediction accuracies on the training data of six predictive models were checked and compared. In addition, the generalization capability of the Arrhenius type constitutive model and the ANN model was investigated under various conditions. Moreover, we propose an ML–mechanism hybrid model to improve the generalization capability of conventional constitutive models and pure data-driven models.

2. Experiments

A TiAl commercial alloy made by the Institute of Metal Research, Chinese Academy of Science (Shenyang, China) was utilized in this study. The nominal composition was Ti-46Al-2Cr-2Nb (at. %), and the microstructure consisted of γ-TiAl and α2-Ti3Al phases [23]. The cylindrical samples with a dimension of 15 × Φ 8 mm were compressed by a Gleeble-3800 thermomechanical simulation machine, and only axial homogeneous stresses were considered during the compression. The recommend strain rate of TiAl alloys should be smaller than 0.1 s−1 [11,13], and the proposed deformation conditions are listed in Table 1. Each TiAl specimen was heated from room temperature to the test temperature at a rate of 10 °C/s, held for 180 s, and then compressed to 50% true strain at the preset strain rate.

Table 1.

The deformation conditions performed on the Gleeble-3800.

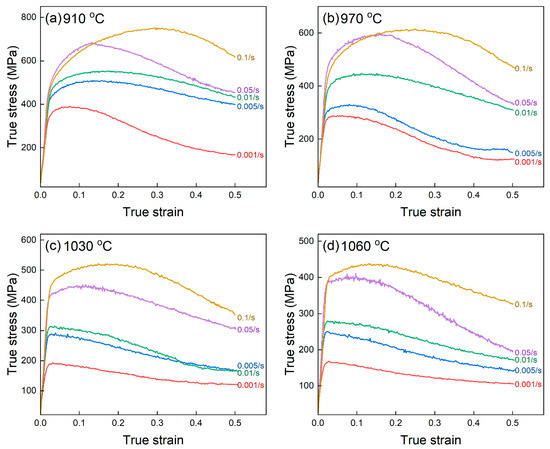

The true stress–strain curves obtained at different deformation conditions are given in Figure 1. The stress–strain curve macroscopically represents the competition between work hardening and softening, which can be observed in Figure 1 [24]. The work hardening phenomenon caused by dislocation multiplications was dominant at the first stage of deformations, and the flow stress increased toward the peak accordingly. Then, the work softening was more significant than the work hardening, leading to a decrease in the flow stress. The work softening mainly resulted from the dynamic recrystallization due to the low stacking fault energy in TiAl alloys [11]. The decrease in flow stress was associated with the higher deformation temperature and the slower strain rate, indicating that the flow stress was sensitive to the deformation conditions [25].

Figure 1.

True stress–strain curves of a TiAl alloy when deformed at the elevated temperature of (a) 910 °C, (b) 970 °C, (c) 1030 °C, and (d) 1060 °C.

3. Predictive Models for Hot Deformation of TiAl Alloys

The flow stresses at eight strains of = 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3, 0.35, and 0.4 were extracted to fit three constitutive models and three ML models. The fitness of each predictive model was evaluated via the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) expressed as follows.

where is the mean of the actual value , and is the corresponding prediction. A greater R2 and a smaller RMSE mean a more accurate model.

3.1. Modified Johnson–Cook (MJC) Model

The Johnson–Cook (JC) model is widely employed in commercial finite element software to evaluate flow stresses of metals at high strain rates and various temperatures [26]. The JC model has been revised to Equation (3) considering the coupling effects of the strain (), strain rate ( in s−1), and deformation temperature (T in K) on flow stresses ( in MPa) [27,28].

where with being the reference strain rate, with being the reference temperature, and B0, B1, B2, C, , and are material constants.

Here, the slowest strain rate 0.001/s and lowest deformation temperature 910 °C were assumed to be reference values. At the reference deformation conditions, Equation (3) can reduce to

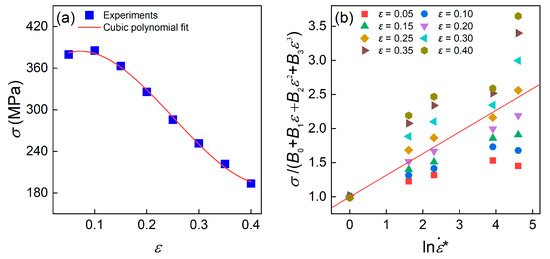

The cubic polynomial fitting of the – plot performed in Figure 2a yielded the values of B0, B1, B2, and B3 as 357.428 MPa, 789.865 MPa, −6346.85 MPa, and 8412.79 MPa, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Cubic polynomial fitting of and at the temperature of 910 °C and the strain rate of 0.001 s−1. (b) Linear relationship between and at the temperature of 910 °C, the red line is the average fitting line.

At the reference temperature, Equation (3) can be expressed as

In which , and the constant C thus can be estimated as 0.3171 by averaging the slopes of the plot at different strain rate, as shown in Figure 2b.

Equation (3) can also be rewritten as

Taking the natural logarithm on both sides of Equation (6) gives

where can be obtained by averaging the slopes of the versus plot at various strain rates.

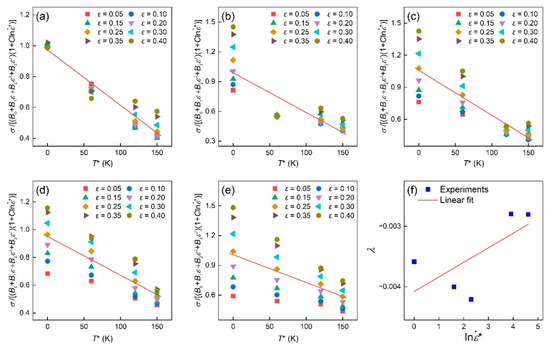

As shown in Figure 3a–e, the values were −0.00594, −0.00571, −0.00542, −0.00406, and −0.00356 when the strain rate was 0.001/s, 0.005/s, 0.01/s, 0.05/s, and 0.1/s, respectively. Next, the values of and can be drawn from the plot in Figure 3f as −0.00408 and 0.000242, respectively. In summary, the material constants in the MJC model for the TiAl alloy are given in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Linear relationship between and at the strain rate of (a) 0.001 s−1, (b) 0.005 s−1, (c) 0.01 s−1, (d) 0.05 s−1, (e) 0.1 s−1, and noting that the red line is the average fitting line. (f) Linear relationship between and .

Table 2.

Fitting material constants in the MJC model for the TiAl alloy.

3.2. Modified Zerilli–Armstrong (MZA) Model

The Zerilli–Armstrong (ZA) model was proposed to describe the deformation behavior of alloys at temperatures lower than 0.6Tm (Tm is the melting temperature) [29]. Samantaray et al. [30] modified the original ZA model to predict the flow stress of metals and alloys at elevated temperatures over 0.6Tm. The MZA model can be expressed as Equation (8).

where C1–C6 and n are material constants. The reference strain rate and reference temperature are the same as the MJC model. At the reference strain rate, Equation (8) can reduce to

Taking the natural logarithm on both sides of Equation (9) gives

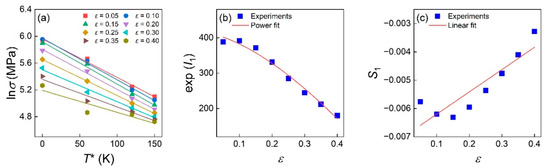

As shown in Figure 4a, the intercept and slope are obtained by the linear fitting of the plot at a certain strain. Since , the power fitting of the plot in Figure 4b can yield the value of , , and n as 462.186, −700.252, and 1.5701, respectively. In addition, the linear fitting of the plot in Figure 4c yielded the value of and as 0.00591 and 0.00013, respectively.

Figure 4.

Relationship between (a) and at various strains, (b) and , and (c) and .

Taking the natural logarithms on both sides of Equation (8) yields Equation (11)

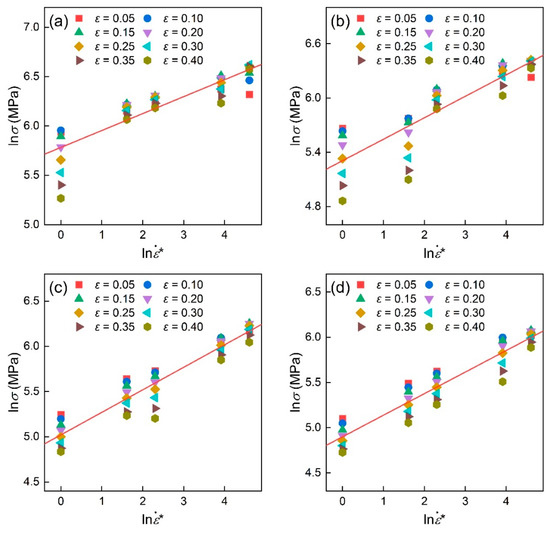

At each deformation temperature, see Figure 5a–d, was obtained by averaging the slopes of the plot. Then, and was calculated as 0.1580 and 0.00055 with the linear fitting of the plot shown in Figure 6. Table 3 lists the evaluated material constants of the MZA model for TiAl alloys.

Figure 5.

Linear relationship between and at the temperature of (a) 910 °C, (b) 970 °C, (c) 1030 °C, and (d) 1060 °C. Noting that the red line is the average fitting line.

Figure 6.

Linear relationship between and .

Table 3.

Fitting material constants in the MZA model for the TiAl alloy.

3.3. Arrhenius Type Model

Sellars et al. [31] proposed an Arrhenius type model expressed as Equation (12) to predict the flow stress during hot deformation.

in which is the peak stress or flow stress at a given strain , R is the universal gas constant, α, A and n are material constants, and Q is the activation energy (kJ/mol). Here, we take the peak stress as an example to demonstrate the definition of material constants α, n, A, and Q.

Taking the natural logarithm on both sides of Equation (13) gives

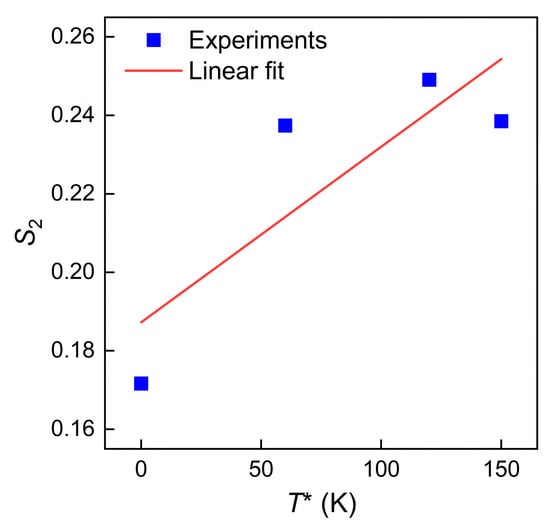

The value of 1/n is obtained by averaging the slopes of the plot under various temperatures. In addition, α is an adjustable constant to ensure a linear and parallel regression of Equation (13) [31]. The present work utilized the Bayesian optimization to determine the value of α [22]. The average R2 value of Equation (13) reached the maximum 0.9920 when was 0.002532. Correspondingly, was deduced as 6.444 in Figure 7a.

Figure 7.

Linear relationship between (a) and , (b) and 1000/T, and (c) and when the adjustable parameter is 0.002532.

Equation (13) is equivalent to Equation (14) expressed as

With the adjusted value, Q thus can be evaluated as the average slope of plots at various strain rates in Figure 7b. The activation energy of the present TiAl alloy calculated by the peak stress was 319 kJ/mol, which was greater than the TiAl self-diffusion activation energy (260 kJ/mol) [32], and similar to other reported TiAl alloys (~350 kJ/mol) [33]. The addition of Cr and Nb increased the activation energy, and thus hindered the hot deformation of TiAl alloys.

With a known activation energy, the Zener–Hollomon (Z) parameter given as Equation (15) can describe the effect of the strain rate and temperature on the deformation behaviors.

Combining Equations (13) and (15) gives the following formula

Thus, was determined as the interception of the plot, see Figure 7c. According to the definition of an inverse hyperbolic sine function, the flow stress at different strains can be predicted via Equation (17).

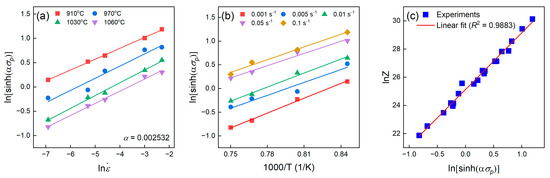

Obviously, the original Sellars model, i.e., Equation (17), ignores the influence of strain on elevated-temperature flow behaviors [34]. Since significant strain effects on flow stresses were observed in the present TiAl alloy, a strain-compensated Sellars (SCS) model should be developed. Similarity, the values of material constants α, n, Q, and lnA at eight given strains can be calculated and listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

The value of material constants of α (MPa−1), n, Q (kJ/mol), and lnA (s−1) for TiAl alloys at different strains.

Generally, the fifth polynomial function is employed to estimate the material constant with different strains. As can be seen in Figure 8, the fifth polynomial function could fit the estimated material constants well (R2 > 0.98). Therefore, Equation (18) represents the SCS model of TiAl alloys, and the corresponding parameters are given Table 5.

Figure 8.

The relationship between the material constant (a) , (b) n, (c) Q, and (d) lnA and the strain.

Table 5.

The coefficients of the polynomial fitting of material constants.

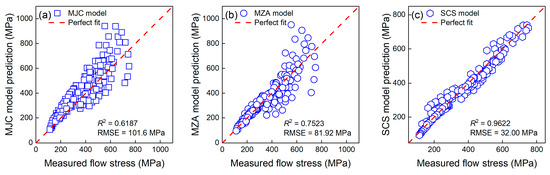

Figure 9 compares the performance of the SCS model, MJC model, and MZA model. For more details of the three constitutive models, please see Gao et al. [35]. As can be seen, the SCS model significantly outperformed the other two constitutive models with a much greater R2 value and an RMSE smaller than 35 MPa. Hence, the SCS model is recommended for simulating the flow behavior of TiAl alloys.

Figure 9.

The predicted flow stress of the (a) MJC model, (b) MZA model, and (c) SCS model versus measured stresses.

3.4. Data-Driven Models

Since the above three constitutive models might not accurately predict the flow behaviors when the stress instability occurs, data-driven models were introduced.

Three ML models including ANN, SVR, and RF models were trained for predicting the flow stress of the considered TiAl alloys. Before constructing the ML models, a feature standardization was employed to standardize the features, i.e., the strain, strain rate, and temperature, given by

where and are the actual value and average actual value of the features, respectively, and is the standard deviation of the features.

There are various hyperparameters that can determine the architecture of the three aforementioned ML algorithms, listed in Table 6, which are efficient in practice [36]. We used the grid search to determine these hyperparameters based on a tenfold cross-validation. The extracted data were equally and randomly divided into ten folds. Each ML model was trained on the training set formed by nine folds and validated on the remaining one. This process was repeated ten times, and the cross-validation R2 (CV-R2) was obtained as the mean of ten validation results. The CV-R2 is regarded as an estimation of the generalization capability, and the application of a cross-validation thus can avoid overfitting.

Table 6.

The hyperparameters of three data-driven models.

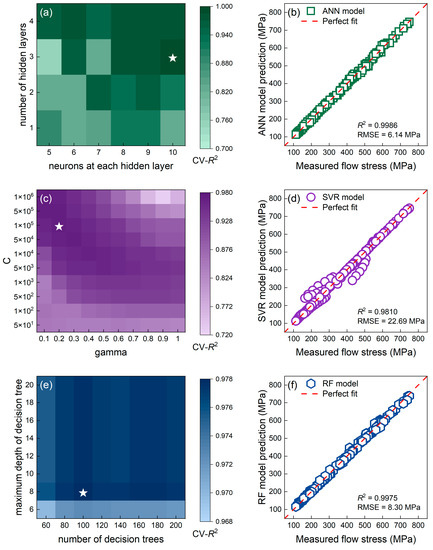

As can be seen in Figure 10a,c,e, the cross-validated R2 (CV-R2) value of all three data-driven models reached 0.97 and higher. The ANN model had the maximum CV-R2 value of 0.9869 when it had three hidden layers, each of which contained 10 neurons (marked with the white star in Figure 10a). In addition, the CV-R2 value for the SVR model was maximized at 0.9728 when C = 100,000 and gamma = 0.2 (white star in Figure 10c), and that for the RF model was maximized at 0.9779 when max_depth = 8 and n_estimators = 100 (white star in Figure 10e). The tuned ANN model had the greatest CV-R2 value among the three ML models, indicating that it had the widest generalization capability.

Figure 10.

The grid search to tune hyperparameters of the (a) ANN model, (c) SVR model, and (e) RF model. The corresponding predicted flow stress of the (b) tuned ANN model, (d) tuned SVR model, and (f) tuned RF model versus the measured values.

Predictions of three data-driven models on eight given strains are illustrated in Figure 10b,d,f versus the measured values. All data-driven models outperformed the constitutive models with R2 value greater than 0.98. In particular, the ANN model had an excellent prediction accuracy, as evidenced by an extremely high R2 value of 0.9986.

4. Generalization Capability of Predictive Models

A good predictive model should have a high prediction accuracy and a wide generalization capability. Therefore, based on the prediction accuracy of three constitutive models and three ML models on training data, only the generalization capabilities of the SCS model and ANN model were further examined.

4.1. Generalization Capability at Interpolated and Extrapolated Strains

Figure 11a,b show the predicted stress–strain responses of the SCS model and ANN model at interpolated strains (0.05 to 0.4 with an interval of 0.01). As expected, both the constitutive model and ML model performed well at interpolated strains. The ANN model had an extremely high R2 value greater than 0.998, and the SCS model had a slightly smaller R2 value of 0.9642. However, as seen in Figure 11c,d, the accuracy of the two predictive models decreased to varying degrees at extrapolated strains (0.41 to 0.5 with an interval of 0.01). The ANN model still performed well at extrapolated strains with a high R2 value of 0.9865, while the R2 value of SCS model was only 0.4623 at extrapolated strains.

Figure 11.

True flow stresses of TiAl alloys under given deformation conditions at interpolated strains and corresponding values predicted by the (a) SCS model and (b) ANN model. True flow stresses of TiAl alloys at extrapolated strains and corresponding values predicted by the (c) SCS model and (d) ANN model.

The mechanism-based SCS model significantly underestimated the flow stress of TiAl alloys at extrapolated strains. This can be explained by the fact that the deformation mechanism of TiAl alloys at large strains might be different from those at small strains, and a similar phenomenon was also reported in nickel-based superalloys [37]. Nevertheless, the pure data-driven ANN model is independent of the mechanism and thus can accurately predict the flow stress at extrapolated strains.

4.2. Generalization Capability at Unknown Deformation Conditions

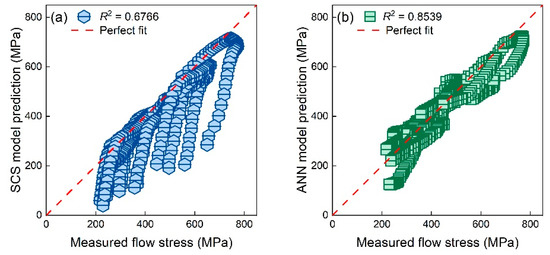

In addition, the stress–strain response under unknown deformation conditions listed in Table 7 was also predicted by the SCS model and ANN model. Unfortunately, neither predictive models could perform well under new deformation conditions; see Figure 12. The R2 value of the SCS model and ANN model were 0.8539 and 0.6766, respectively.

Table 7.

The new deformation conditions to examine generalization capabilities.

Figure 12.

True flow stresses of TiAl alloys under new deformation conditions at strains between 0.05 and 0.5 and corresponding values predicted by the (a) SCS model and (b) ANN model.

As previously mentioned, the ANN model did not consider any deformation mechanism. Therefore, the accuracy of the ANN model under unknown conditions decreased by around 15% compared to that under known conditions. The underlying mechanism under different conditions was similar. Hence, the performance of the SCS model under unknown conditions was nearly the same as that under known conditions. That is, the SCS model could predict the flow stress at small strains (<0.4) well, while its performance at larger strains was extremely poor.

4.3. Improvement of Generalization Capability

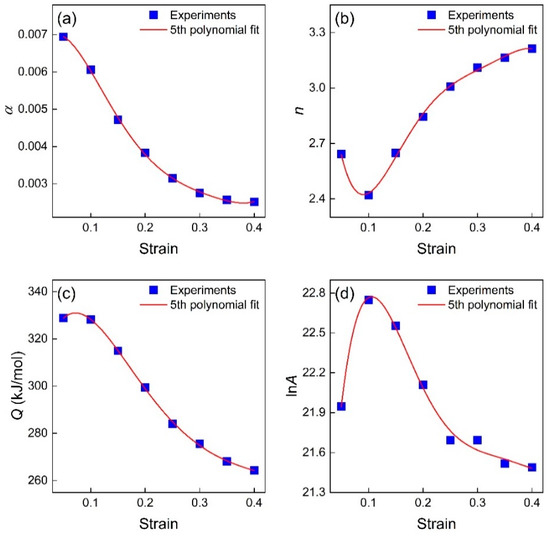

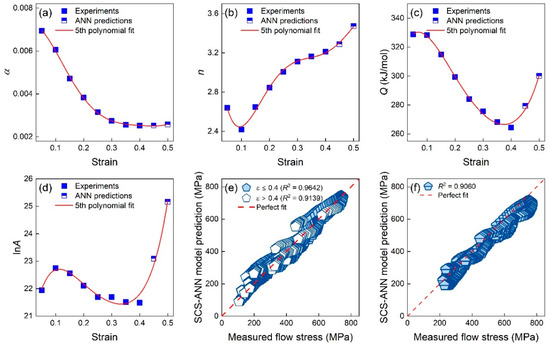

Based on the generalization capability of the SCS model and ANN with different inputs, we proposed a mechanism–ML hybrid model. The predictions of the ANN model at large strains (0.45 and 0.5 here) were combined with the experimental results at small strain (0.05–0.4) to determine the parameters of the SCS model. The obtained SCS model based on hybrid inputs was termed as SCS-ANN model, and the fifth polynomial fits of material constants for the SCS-ANN model are shown in Figure 13. The related parameters of the SCS-ANN model are listed in Table 8.

Figure 13.

The fifth polynomial fitting of material constants (a) , (b) n, (c) Q, and (d) lnA with experiments and ANN predictions for the SCS-ANN model. The predictions of the SCS-ANN model under the (e) given deformation conditions and (f) new deformation conditions.

Table 8.

The coefficients of material constants based on experiments and ANN predictions.

At known deformation conditions, the R2 values of the SCS-ANN model when predicting the stress–strain response at interpolated and extrapolated strains were 0.9642 and 0.9139, respectively. The introduction of ANN predictions could significantly improve the performance of the SCS models at extrapolated strains. For new deformation conditions, the R2 value of the SCS-ANN model could reach 0.9, meaning a better generalization capability than conventional constitutive models as well as data-driven models. The hybrid SCS-ANN model is an accurate and generalized model for predicting the hot-deformation behaviors of the considered TiAl alloys.

5. Conclusions

This work investigated the hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys under different loading strain rates at various deformation temperatures. The experimental results were analyzed by three constitutive models including the MJC model, MZA model, and SCS model. In addition, an ML-based ANN model, SVR model, and RF model were employed to predict the hot-deformation behaviors as well. The following conclusion can be summarized.

- (1)

- The hot-deformation behaviors of TiAl alloys were examined under different deformation conditions. The flow stress of the TiAl alloys was found to be sensitive to the deformation temperature and strain rates. The activation energy of Ti-46Al-2Cr-2Nb was 319 kJ/mol, which was greater than the TiAl self-diffusion activation energy.

- (2)

- The Arrhenius type SCS model had a better predictive accuracy than the MJC and MZA models, with an R2 value of 0.9622 on the training data. As for the generalization capability, the SCS model only performed well at interpolated strains under known deformation conditions, and the corresponding R2 value was 0.9654. The R2 value of SCS model at extrapolated strains or under new deformation conditions was smaller than 0.7.

- (3)

- All three data-driven models performed better than the constitutive models, and the ANN model performed the best with an extremely high R2 value of 0.9986. The ANN model had a good generalization capability under known deformation conditions; the R2 values at interpolated strains and extrapolated strains were 0.9984 and 0.9865, respectively. However, the ANN model could not perform well under new deformation conditions, with a corresponding R2 value of only 0.8539.

- (4)

- For limited hot-deformation experimental data, the ANN model was recommended to predict the flow behavior of TiAl alloys at larger strains. Then, predictions of the ANN model were further combined with experimental results to construct an ML–mechanism hybrid SCS-ANN model. The hybrid model was more accurate than the pure data-driven model and mechanism-based model under unknown deformation conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z.; Methodology, J.X.; Software, R.Z.; Formal analysis, J.X.; Investigation, H.T. and Y.J.; Writing—original draft, R.Z. and J.X.; Writing—review & editing, J.H. and J.X.; Supervision, J.X.; Project administration, J.H.; Funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 91860115) and the State Key Lab of Advanced Welding and Joining, Harbin Institute of Technology (grant no. AWJ-23R04).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Das, G.; Kestler, H.; Clemens, H.; Bartolotta, P.A. Sheet Gamma TiAl: Status and Opportunities. JOM 2004, 56, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, T.; Fukai, H.; Izumi, O. Effect of Ternary Additions on Mechanical Properties of TiAl. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 2185–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollinger, J.; Lapin, J.; Daloz, D.; Combeau, H. Influence of Oxygen on Solidification Behaviour of Cast TiAl-Based Alloys. Intermetallics 2007, 15, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, H.; Chladil, H.F.; Wallgram, W.; Zickler, G.A.; Gerling, R.; Liss, K.-D.; Kremmer, S.; Güther, V.; Smarsly, W. In and Ex Situ Investigations of the β-Phase in a Nb and Mo Containing γ-TiAl Based Alloy. Intermetallics 2008, 16, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loria, E.A. Gamma Titanium Aluminides as Prospective Structural Materials. Intermetallics 2000, 8, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, S.L.; Krause, D.; Lerch, B.; Locci, I.E.; Doehnert, B.; Nigam, R.; Das, G.; Sickles, P.; Tabernig, B.; Reger, N.; et al. Development and Evaluation of TiAl Sheet Structures for Hypersonic Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 464, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.T.; Chen, Y.Y.; Li, B.H. Influence of Yttrium on the High Temperature Deformability of TiAl Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 499, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.J.; Lin, J.P.; Wang, Y.L.; Lin, Z.; Chen, G.L. Deformability and Microstructure Transformation of Pilot Ingot of Ti–45Al–(8–9)Nb–(W,B,Y) Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 416, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Jiang, H.; Tian, S.; Zhang, G. Nanoscale Twinned Ti-44Al-4Nb-1.5Mo-0.007Y Alloy Promoted by High Temperature Compression with High Strain Rate. Metals 2018, 8, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xue, X.; Tang, B.; Kou, H.; Li, J. Flow Characteristics and Constitutive Modeling for Elevated Temperature Deformation of a High Nb Containing TiAl Alloy. Intermetallics 2014, 49, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S. High Temperature Deformation Behavior of Ti–46Al–2Cr–4Nb–0.2Y Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 539, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.J.; Wu, K.H.; Shi, J.; Zou, D. Development of Constitutive Relationships for the Hot Deformation of Boron Microalloying TiAl-Cr-V Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1995, 192–193, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Jiang, H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, S. Hot Deformation and Dynamic Recrystallization Behavior of TiAl-Based Alloy. Intermetallics 2019, 112, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari, P.R.; Sirimontree, S.; Thongchom, C.; Jearsiripongkul, T.; Saffari, P.R.; Keawsawasvong, S. Effect of Uniform and Nonuniform Temperature Distributions on Sound Transmission Loss of Double-Walled Porous Functionally Graded Magneto-Electro-Elastic Sandwich Plates with Subsonic External Flow. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 17, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H. A Study on the Flow Behavior and Bubble Evolution of Circular Oscillating Laser Welding of SUS301L-HT Stainless Steel. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 202, 123726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wan, Z.; Hu, L.; Ren, J. Characterization of Hot Processing Parameters of Powder Metallurgy TiAl-Based Alloy Based on the Activation Energy Map and Processing Map. Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lin, J. Hot Deformation Behavior and Artificial Neural Network Modeling of β-γ TiAl Alloy Containing High Content of Nb. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, H.; Serajzadeh, S. Estimation of Flow Stress Behavior of AA5083 Using Artificial Neural Networks with Regard to Dynamic Strain Ageing Effect. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 196, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, J. Application of Neural Networks to Predict the Elevated Temperature Flow Behavior of a Low Alloy Steel. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.-M.; Gao, Z.-W.; Gao, X.-Y. Predicting Flow Stress of Ni Steel Based on Machine Learning Algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2022, 236, 4253–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, K. Investigation on Hot Forging Strategy for 5CrNiMoV via High-Throughput Experiment and Machine Learning. Eng. Res. Express 2021, 3, 025013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; He, J.-C.; Leng, X.-S.; Zhang, T.-Y. Gaussian Process Regressions on Hot Deformation Behaviors of FGH98 Nickel-Based Powder Superalloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 146, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Tian, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, B.; He, J. The Relationship between Microstructure and Fracture Behavior of TiAl/Ti2AlNb SPDB Joint with High Temperature Titanium Alloy Interlayers. Materials 2022, 15, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ye, W.H.; Hu, L.X. Constitutive Modeling of High-Temperature Flow Behavior of Al-0.62Mg-0.73Si Aluminum Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zeng, W.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y. Hot Deformation Behavior and Flow Stress Prediction of TC4-DT Alloy in Single-Phase Region and Dual-Phase Regions. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 24, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Wang, G.; Kent, D.; Dargusch, M. Constitutive Modelling of the Flow Behaviour of a β Titanium Alloy at High Strain Rates and Elevated Temperatures Using the Johnson–Cook and Modified Zerilli–Armstrong Models. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 612, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, P. A Comparative Study on Johnson-Cook and Modified Johnson-Cook Constitutive Material Model to Predict the Dynamic Behavior Laser Additive Manufacturing FeCr Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 723, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, D.; Shipley, H.; Lea, L.; Jardine, A.; O’Donnell, G.E. Constitutive Analysis of Biomedical Grade Co-27Cr-5Mo Alloy at High Strain Rates. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.-T.; Cheng, W.-C.; Lee, W.-S. Strain Rate Effects on the Mechanical Properties of a Fe–Mn–Al Alloy under Dynamic Impact Deformations. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 392, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, D.; Mandal, S.; Bhaduri, A.K. A Comparative Study on Johnson Cook, Modified Zerilli–Armstrong and Arrhenius-Type Constitutive Models to Predict Elevated Temperature Flow Behaviour in Modified 9Cr–1Mo Steel. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2009, 47, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, C.M.; McTegart, W.J. On the Mechanism of Hot Deformation. Acta Metall. 1966, 14, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, Y.; Herzig, C. Diffusion in the Ti-Al System. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 589–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.P.; Prasad, Y.V.R.K.; Suresh, K. Hot Working Behavior and Processing Map of a γ-TiAl Alloy Synthesized by Powder Metallurgy. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 4874–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Y.; Li, Y.-H.; Wang, X.-F.; Liu, J.-J.; Wu, Y. A Comparative Study on Modified Johnson Cook, Modified Zerilli–Armstrong and Arrhenius-Type Constitutive Models to Predict the Hot Deformation Behavior in 28CrMnMoV Steel. Mater. Des. 2013, 49, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, H.; Tang, D.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X. Six Different Mathematical Models to Predict the Hot Deformation Behavior of C71500 Cupronickel Alloy. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2020, 49, 4129–4141. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Hu, B. Modeling of Thermal Deformation Behavior near Γ′ Solvus in a Ni-Based Powder Metallurgy Superalloy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 156, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).