Abstract

We study the magnetic properties of platinum diselenide (PtSe2) intercalated with Ti, V, Cr, and Mn, using first-principle density functional theory (DFT) calculations and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations. First, we present the equilibrium position of intercalants in obtained from the DFT calculations. Next, we present the magnetic groundstates for each of the intercalants in along with their critical temperature. We show that Ti intercalants result in an in-plane AFM and out-of-plane FM groundstate, whereas Mn intercalant results in in-plane FM and out-of-plane AFM. V intercalants result in an FM groundstate both in the in-plane and the out-of-plane direction, whereas Cr results in an AFM groundstate both in the in-plane and the out-of-plane direction. We find a critical temperature of <0.01 K, 111 K, 133 K, and 68 K for Ti, V, Cr, and Mn intercalants at a 7.5% intercalation, respectively. In the presence of Pt vacancies, we obtain critical temperatures of 63 K, 32 K, 221 K, and 45 K for Ti, V, Cr, and Mn-intercalated , respectively. We show that Pt vacancies can change the magnetic groundstate as well as the critical temperature of intercalated , suggesting that the magnetic groundstate in intercalated can be controlled via defect engineering.

1. Introduction

The field of two-dimensional (2D) spintronics [1] has seen unprecedented attention in the past few years, thanks to the recent experimental discovery of two-dimensional (2D) magnetic materials [2,3] and [4]. However, the low Curie temperature of experimentally discovered 2D magnets (45 K for monolayer and 61 K for bulk ) impedes their technological application. Thankfully, there are many possible 2D magnets. One avenue of finding such 2D magnets is searching the space of magnetic crystals [5,6]. Another avenue of realizing 2D magnets is through magnetic doping [7,8] of conventional 2D materials. The advantage of such magnetically doped magnets is the ability to control their properties through charge transfer.

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) offer a promising avenue for realizing 2D magnets through magnetic doping [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. There have been many theoretical [7,8,11,12,14] and experimental [9,10,13] reports of realizing 2D magnetism in semiconducting TMDs through metal doping. On the theoretical side, Mishra et al. [11] investigated the effect of Mn doping on the magnetic properties of MoS2, MoSe2, MoTe2, and WS2. Mn-doped MoS2 was also studied by A. Ramasubramaniam and D. Naveh [12], who obtained promising results predicting magnetic order persisting above room temperature. The work of Muhammad H. et al. [9] combined experimental fabrication and characterization with DFT methods to investigate the magnetic properties of Ni-doped WSe2, which they reported to have room-temperature magnetic ordering. Luo et al. produced a review paper discussing the doping and functionalization of several different 2D TMDs [15], including MoS2, MoSe2, WS2, and WSe2. However, similar work on realizing magnetic order in metallic TMDs with the 1T structure is not as common. As recent reports on 2D metallic magnetic systems, e.g., [16], show room-temperature magnetic order, it is natural to look at other metallic systems, such as PtSe2.

Metallic TMDs are interesting because free electrons can provide a pathway for long-range magnetic interaction. One such interesting metallic TMD is . forms a layered TMD with semimetallic character [17]. More recently, epitaxial growth of mono- and few-layer has revealed a transition to semiconducting character for the monolayer and bilayer [18,19]. Moreover, the large atomic weight of can result in a higher anisotropy, which is necessary for the existence of 2D magnetic order [20]. Kar et al. performed a first-principles study of the magnetism in doped PtSe2 monolayers and found promising higher-than-room-temperature magnetic ordering [21]. However, detailed work on the magnetic ordering, including Monte Carlo simulations for the estimation of the transition temperature in magnetically doped PtSe2, is still missing from the literature. The presence of Pt vacancies in pristine is responsible for a spin polarization of the electronic cloud around the vacancy, making defective a material of interest for future spintronic applications [22,23]. Moreover, theoretical studies have shown that the presence of vacancies in TMDs is energetically favorable in pristine grown in Se-rich conditions [24] and reduces the formation energy of intercalated systems [8]. In Ref. [24], the authors find a Pt vacancy density of in ultrathin layered .

In this work, we theoretically investigate the magnetic order in bulk intercalated with Ti, V, Cr, and Mn, using first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations. In Section 2, we describe the methods used in our work, starting from DFT for the calculation of structural parameters and magnetic groundstates, up to the critical temperature calculation using Monte Carlo. In Section 3, we first present the equilibrium position of intercalants in obtained from the DFT calculations. Next, we present the magnetic groundstates for each of the intercalants in along with their critical temperature. We study the effect of Pt vacancies on the structure and formation energy and investigate their impact on the magnetic order. Finally, in Section 4, we conclude.

2. Methods

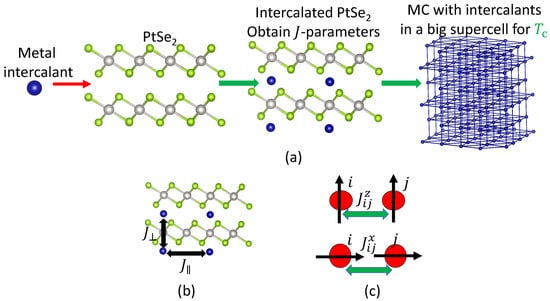

Figure 1a illustrates our computational model. We first intercalate a supercell of and calculate the total energy of various magnetic configurations including ferromagnetic (FM) and anti-ferromagnetic (AFM) configurations using DFT+U calculations. Details on the computational parameters are included in Appendix A. To take into account the magnetic anisotropy, we perform total energy calculations with spin-axis oriented in the in-plane and the out-of-plane direction.

Figure 1.

(a) The magnetic ions are intercalated in . (b) The exchange parameters in the in-plane () and in the out-of-plane () direction. (c) The J parameters between spins i and j oriented in the in-plane direction () and in the out-of-plane direction ().

Next, we model the magnetic structure of an intercalated supercell using a parameterized Heisenberg Hamiltonian:

where is the magnetic moment vector of the intercalant atom. The exchange interaction strength tensor [7], with elements describing the strength of the interaction between spins at site i and j, is assumed to be rotationally invariant in the direction of the planes, because has in-plane rotational symmetry. Additionally, we assume that the interaction strength in the x and the y directions is equal and that the tensor’s diagonal elements are vanishingly small. The result is a diagonal exchange interaction strength tensor with elements where . We consider the range of interaction up to the nearest-neighbor atoms in the in-plane and the out-of-plane direction shown in Figure 1b. The second term is the single-ion anisotropy D. With being diagonal and rotationally invariant in the plane of the layers, the Heisenberg Hamiltonian becomes

Here, is the direction of spins, when oriented in the in-plane/out-of-plane direction, as shown in Figure 1c. The parameters and D are obtained by fitting to the total-energy DFT calculations using the method developed in Ref. [25]. To assess the validity of the nearest-neighbor approximation, we have performed additional calculations to investigate the effect of the second-nearest-neighbor interactions, of which the details are explained in Section S1 of the Supplementary Information.

After obtaining the parameters of the Heisenberg Hamiltonian, we make larger supercells of intercalated (, or 512 magnetic sites), and study the magnetic phase transition using MC simulations. For each material, we perform ten independent MC runs, each with a different initial condition. We simulate the magnetic order using 3000 equilibration steps and 3000 subsequent MC steps. From the MC simulations, we obtain the specific heat and the magnetization of the intercalated as a function of temperature. From the peak of the specific heat, we determine the critical (Curie/Néel) temperature.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structure of Intercalated PtSe2

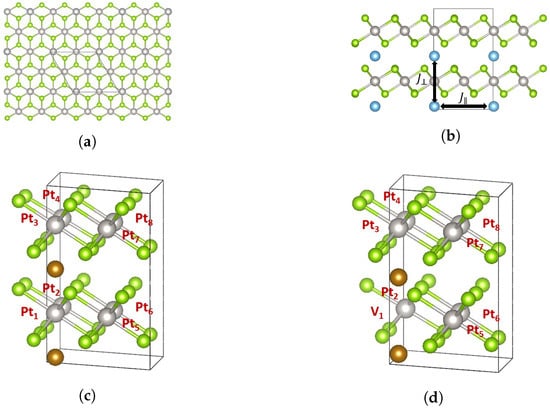

Figure 2 shows the structure of intercalated . Figure 2a,b show the top and the side view of the most stable structure of the intercalated PtSe2 for each of Ti, V, Cr, and Mn intercalation (see Section S2 of the Supplementary Information for structural details, and Section S3 for details on the formation energy calculations), obtained from DFT relaxation in a supercell.

Figure 2.

(a) Top view of the intercalated . The original unit cell has 8 Pt atoms, 16 Se atoms, and 2 intercalant atoms. (b) The side view of the intercalated . The in-plane () and out-of-plane () exchange interactions are shown as well. (c) The structure without vacancies. (d) The structure with a Pt vacancy at the location of Pt1.

We define the intercalation fraction according to the number of potential intercalant sites. The intercaltion of 3d transition metals into MX2 TMDs (with M = metal and X = chalcogen), such as and WSe2, typically happens at sites with octahedral coordination of X atoms [26]. Therefore, since we have one intercalant for every four octahedral intercalation sites, we express the intercalated as TM1/4 (where TM = intercalant atom). We use the same DFT-relaxed TM1/4 in all subsequent calculations. We choose the fraction TM1/4 for our study because the intercalants are likely to form an ordered superlattice along the c axis of the hexagonal unit cells (i.e., in the out-of-plane direction) [26,27].

3.2. Magnetic Ordering and Critical Temperature

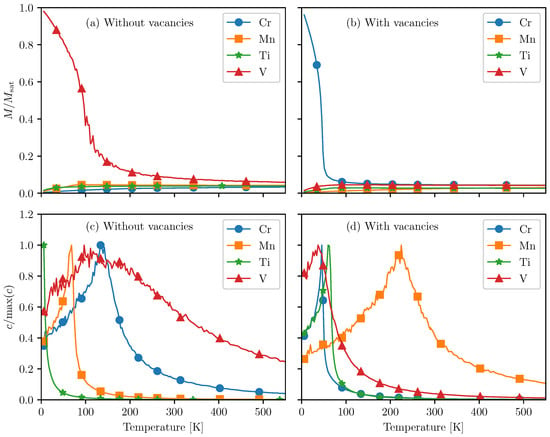

Figure 3a shows the magnetization as a function of temperature for intercalated PtSe2 for intercalants Ti, V, Cr, and Mn without Pt vacancies. We normalize the curves to the saturation magnetization , which is the maximum magnetization that can be achieved in the material, when all magnetic moments point in exactly the same direction. We observe that when no vacancies are present, the magnetization for V saturates at low temperatures, suggesting a ferromagnetic transition. For Ti, Cr, and Mn, the magnetization vanishes at lower temperatures, suggesting an anti-ferromagnetic transition.

Figure 3.

(a) The magnetization of intercalated for various intercalants without any vacancies. M is the magnetization per intercalant atom obtained from the MC simulations and is the saturation magnetization. (b) The magnetization of intercalated for various intercalants in the presence of vacancies. (c) The specific heat c of intercalated for various intercalants without any vacancies. (d) The specific heat c of intercalated in the case where vacancies are present.

Figure 3b shows the magnetization as a function of temperature for intercalated PtSe2 for intercalants Ti, V, Cr, and Mn with Pt vacancies. We observe that when the vacancies are present, the magnetization of Ti-, V-, and Mn-intercalated goes to zero, suggesting an anti-ferromagnetic order. For Cr-intercalated , the magnetization reaches saturation, suggesting a ferromagnetic transition.

Figure 3c shows the specific heat as a function of temperature for intercalated pristine . We observe that the specific heat peaks at for V, for Cr, and at for Mn. However, for Ti, the specific heat peaks at a much lower temperature, namely below the lowest temperature point in our simulation, .

Figure 3d shows the specific heat as a function of temperature for intercalated pristine . When vacancies are present, the specific heat peaks at , , , and for Ti, V, Cr, and Mn, respectively.

3.3. Exchange Interactions and Magnetic Groundstate

Table 1 shows the obtained J parameters, onsite anisotropy (D), and the magnetic moment () for various intercalants obtained from the DFT calculations, with and without Pt vacancies. The J parameters increase quite significantly for Ti and Mn, boosting their Néel temperature from below and in pristine to and in defective , respectively. Moreover, we see that although the out-of-plane J parameters () of V remain positive, the in-plane J parameters () become negative, resulting in an in-plane AFM and out-of-plane FM groundstate. The V-intercalated therefore changes from a ferromagnet with of , to an anti-ferromagnet with a of . For Cr, all J parameters, both in-plane and out-of-plane, change sign, resulting in a change in the magnetic groundstate from purely anti-ferromagnetic to purely ferromagnetic, when vacancies are present. Cr-intercalated changes from an anti-ferromagnet with when the is pristine to a ferromagnet with when the material contains vacancies. Additionally, we find that for all the intercalants except for Ti, the out-of-plane interaction () is stronger than the in-plane interaction, suggesting a strong out-of-plane super super-exchange interaction [28].

Table 1.

Summary of the results for the intercalated PtSe2 with and without vacancies. Results for structures with vacancies are in the columns marked with (PtV).

The interaction between magnetic intercalant atoms occurs through a super super-exchange interaction chain X – Se – Pt – Se – X, where X denotes the intercalant atom (in our case: Ti, V, Cr, or Mn). The d orbitals of the intercalant atoms couple to each other through the p orbitals of the Se atoms and the d orbitals of the Pt atom in the chain. In the super super-exchange mechanism, each step in the chain consists of an anti-ferromagnetic coupling, so that the X atoms are ferromagnetically coupled. In the case where the X atoms have a positive spin density, the chain consists of the following spin density signs: X (+) – Se (−) – Pt (+) – Se (−) – X (+), where “+” refers to a positive spin density, and “−” refers to a negative spin density. When such a ferromagnetic coupling is satisfied, the super super-exchange interactions will stabilize the ferromagnetic state and be the reason that the out-of-plane exchange parameters are large.

In the case of V-intercalated without vacancies, we see that the V (+) – Se (−) – Pt (+) – Se (−) – V (+) chain is satisfied; see Figure S3a in the Supplementary Information. From Table 1, we see that the out-of-plane exchange coupling is indeed strong, and (see Table 1), when compared to the in-plane exchange interaction. Such a coupling through the super super-exchange mechanism stabilizes the ferromagnetic state, which is why the V-intercalated without vacancies has a ferromagnetic groundstate.

For Mn-intercalated , however, we see that the chain has a different form: the Mn (+) – Se (−) – Pt (−) – Se (−) – Mn (+); see Figure S3b in the Supplementary Information. We see that the super super-exchange interaction does not take place, and that because of the lack of super super-exchange interaction, the out-of-plane exchange parameters are small, namely and ; see Table 1. The lack of stabilizing super super-exchange interactions causes an energy penalty in the ferromagnetic state, which pushes the state up in energy. The result is that the groundstate of Mn-intercalated is not the ferromagnetic state, but an anti-ferromagnetic state.

Additionally, looking at the effect of vacancies, we can attribute the destabilization of the ferromagnetic state of V-intercalated to a disruption of the super super-exchange interactions, causing a drop in the strength of the out-of-plane exchange parameters, namely drops from to and drops from to when the Pt vacancies are considered. The disruption of the super super-exchange mechanism causes the ferromagnetic state to shift up in total energy, and the groundstate goes from being a ferromagnetic state with a Curie temperature of to being an anti-ferromagnetic state with a Néel temperature of .

Comparing the J parameters in Table 1, we see that the sign of either the in-plane () or the out-of-plane () exchange parameters change for all the intercalants. The change in the sign of J parameters suggests that the magnetic groundstate changes for all of the intercalated with Pt vacancy compared to intercalated pristine . The tunability of J parameters with vacancy suggests that the magnetic properties of intercalated can be tuned by creating vacancies in .

From the DFT results, we extract the localized magnetic moments on each atom of our intercalated materials. We find that the magnetic moments on the Pt and Se atoms are small compared to the moments on the intercalant atoms. The largest relative magnetic moment on a Pt atom occurs in Ti-intercalated in the presence of vacancies and its size is 8.43% of that of the Ti atoms. The smallest relative magnetic moment on a Pt atom occurs in pristine Mn-intercalated and its size is only 0.5% of the magnetic moment of the Mn atoms. Therefore, we conclude that our assumption that the magnetic moments are mostly located on the intercalant atoms is correct.

4. Conclusions

We have theoretically studied the possibility of realizing magnetic order in 1T- through magnetic intercalation with Ti, V, Cr, and Mn. We showed that Ti results in an in-plane AFM and out-of-plane FM groundstate, whereas Mn results in in-plane FM and out-of-plane AFM. V results in an FM groundstate both in-plane and out-of-plane, whereas Cr results in an AFM groundstate both in the in-plane and out-of-plane direction. The critical temperatures that we find are lower than , , , and for Ti, V, Cr, and Mn, respectively.

We have further shown that the Pt vacancy significantly impacts the magnetic order in intercalated both qualitatively and quantitatively. Most significantly, V intercalants become in-plane AFM from in-plane FM, and Cr intercalants transition from an AFM groundstate to an FM groundstate. Moreover, the Néel temperature of both Ti and Mn intercalants increases with Pt vacancy to and compared to a lower than and in the pristine , respectively. Finally, we have shown that Pt vacancies can reduce the energy of formation in intercalated .

The tunability of the magnetic groundstate and critical temperature opens a plethora of opportunities for defect engineering the magnetic groundstate in through intercalation. Further exploration of the electronic properties of intercalated would provide deeper insights into the tuning of the magnetic order in . Additionally, we would like to mention that investigating the stability of magnetic states for different intercalant fractions would be an interesting avenue for future studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ma14154167/s1, Figure S1: The supercell used in the next-nearest neighbor calculations, Table S1: The lattice vectors and angles for the intercalated PtSe2 structures with and without Pt vacancies, Figure S2: The formation energy of the different intercalated PtSe2 structures, with and without vacancies present, Figure S3: (a) Spin density for V-intercalated PtSe2. (b) Spin density for Mn-intercalated PtSe2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: W.G.V. and B.S.; Funding acquisition: W.G.V and B.S.; Code development: S.T. and P.D.R.; Simulations: P.D.R.; Analysis: P.D.R., S.T., M.L.V.d.P.; Supervision: M.L.V.d.P., W.G.V., B.S.; Writing—Original draft: P.D.R.; Writing—Discussion and editing: All authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project or effort depicted was or is sponsored by the Department of Defense, Defense Threat Reduction Agency. The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the federal government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1802166. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work was supported by imec’s Industrial Affiliation Program.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article (and its supplementary material).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at The University of Texas at Austin for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper: http://www.tacc.utexas.edu (accessed on 21 July 2021). Peter D. Reyntjens acknowledges support by the Eugene McDermott Fellowship program, under Grant Number 201806.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TMD | Transition Metal Dichalcogenide |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| FM | Ferromagnetic |

| AFM | Anti-ferromagnetic |

Appendix A. DFT Calculations

For all our DFT calculations, we use the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) [29,30,31,32]. We use the Projector-Augmented Wave (PAW) method [33] and the generalized gradient approximation proposed by Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof [34] for the exchange and correlation functionals in our calculations. To account for the Van der Waals interactions, we use the DFT-D3 method of Grimme et al. [35]. In all our DFT calculations, we set the plane-wave cutoff energy at and employ an energetic convergence criterion of to ensure our results are accurate. Prior to any self-consistent or Monte Carlo calculation, we perform the structural optimization of our systems by changing the lattice parameters and ionic positions until all the forces on the ions are lower than /Å.

Appendix A.1. Hubbard U Correction

The intercalants are elements with highly correlated electrons in the 3d-shell. Because we use atoms which have an incomplete 3d-shell as intercalants, we need to consider the correlation effects of electrons in the 3d-shell. We use the Hubbard U correction within DFT (DFT + U) [36] We estimate the value of the U parameter using the linear response method of M. Coccocioni and S. De Gironcoli [37]. For each + intercalant system, we use the value of U obtained using the linear response method in all spin-polarized noncollinear DFT + U calculations for that system. The results are listed in Table 1.

Appendix A.2. Total Energies of the Magnetic States

The strength of magnetic interactions between the dopants depends on the relative stability of the various magnetic states. To get an accurate picture of the magnetic behavior around the critical (Curie or Néel) temperature, we therefore calculate the total energies of different ferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic and anti-ferromagnetic states for each material. On each intercalant site, we take all ferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic and anti-ferromagnetic combinations of the up and down spins states. Once the different spin configurations have been determined we perform non-collinear DFT + U by aligning each configuration along the [100] and [001] directions. We set the size of the initial magnetic moments in our DFT simulations according to the number of unpaired electrons in the d-shell of the intercalant atoms. The final groundstate magnetic moments are lower than the number of unpaired electrons due to the formation of bonds.

References

- Cortie, D.L.; Causer, G.L.; Rule, K.C.; Fritzsche, H.; Kreuzpaintner, W.; Klose, F. Two-Dimensional Magnets: Forgotten History and Recent Progress towards Spintronic Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1901414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M.A.; Dixit, H.; Cooper, V.R.; Sales, B.C. Coupling of Crystal Structure and Magnetism in the Layered, Ferromagnetic Insulator CrI3. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Clark, G.; Navarro-Moratalla, E.; Klein, D.R.; Cheng, R.; Seyler, K.L.; Zhong, D.; Schmidgall, E.; McGuire, M.A.; Cobden, D.H.; et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a Van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 2017, 546, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gong, C.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Ji, H.; Stern, A.; Xia, Y.; Cao, T.; Bao, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 2017, 546, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Torelli, D.; Thygesen, K.S.; Olsen, T. High throughput computational screening for 2D ferromagnetic materials: The critical role of anisotropy and local correlations. 2D Mater. 2019, 6, 045018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tiwari, S.; Vanherck, J.; Van de Put, M.L.; Vandenberghe, W.G.; Soree, B. Computing Curie Temperature of Two-Dimensional Ferromagnets in the Presence of Exchange Anisotropy. 2021. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.07958 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Tiwari, S.; Van de Put, M.L.; Sorée, B.; Vandenberghe, W.G. Magnetic order and critical temperature of substitutionally doped transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 2021, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyntjens, P.D.; Tiwari, S.; Van de Put, M.L.; Sorée, B.; Vandenberghe, W.G. Magnetic properties and critical behavior of magnetically intercalated WSe2: A theoretical study. 2D Mater. 2020, 8, 025009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Muhammad, Z.; Khan, R.; Wu, C.; ur Rehman, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, L. Ferromagnetism in CVT grown tungsten diselenide single crystals with nickel doping. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 115701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Lou, X.; Xie, Z.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chang, H. Ta Doping Enhanced Room-Temperature Ferromagnetism in 2D Semiconducting MoTe2 Nanosheets. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2019, 5, 1900552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Zhou, W.; Pennycook, S.J.; Pantelides, S.T.; Idrobo, J.C. Long-range ferromagnetic ordering in manganese-doped two-dimensional dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 144409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramaniam, A.; Naveh, D. Mn-doped monolayer MoS2: An atomically thin dilute magnetic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 195201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.J.; Duong, D.L.; Ha, D.M.; Singh, K.; Phan, T.L.; Choi, W.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, Y.H. Ferromagnetic Order at Room Temperature in Monolayer WSe2 Semiconductor via Vanadium Dopant. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1903076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yue, Q.; Chang, S.; Qin, S.; Li, J. Functionalization of monolayer MoS2 by substitutional doping: A first-principles study. Phys. Lett. A 2013, 377, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Zhuge, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lv, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhai, T. Doping engineering and functionalization of two-dimensional metal chalcogenides. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019, 4, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Z.; Huang, B.; Malinowski, P.; Wang, W.; Song, T.; Sanchez, J.; Yao, W.; Xiao, D.; Zhu, X.; May, A.F.; et al. Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, G.Y.; Liang, W.Y. The electronic structures of platinum dichalcogenides: PtS2, PtSe2 and PtTe2. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1986, 19, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Yao, W.; Song, S.; Sun, J.T.; Pan, J.; Ren, X.; Li, C.; Okunishi, E.; Wang, Y.Q.; et al. Monolayer PtSe2, a New Semiconducting Transition-Metal-Dichalcogenide, Epitaxially Grown by Direct Selenization of Pt. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 4013–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawkat, M.S.; Gil, J.; Han, S.S.; Ko, T.J.; Wang, M.; Dev, D.; Kwon, J.; Lee, G.H.; Oh, K.H.; Chung, H.S.; et al. Thickness-Independent Semiconducting-to-Metallic Conversion in Wafer-Scale Two-Dimensional PtSe2 Layers by Plasma-Driven Chalcogen Defect Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 14341–14351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermin, N.D.; Wagner, H. Absence of Ferromagnetism or Antiferromagnetism in One- or Two-Dimensional Isotropic Heisenberg Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1966, 17, 1133–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.; Sarkar, R.; Pal, S.; Sarkar, P. Engineering the magnetic properties of PtSe2 monolayer through transition metal doping. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2019, 31, 145502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avsar, A.; Cheon, C.Y.; Pizzochero, M.; Tripathi, M.; Ciarrocchi, A.; Yazyev, O.V.; Kis, A. Probing magnetism in atomically thin semiconducting PtSe2. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Tian, T.; Hu, X.; Zeng, K.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.W. Structure, Stability, and Kinetics of Vacancy Defects in Monolayer PtSe2: A First-Principles Study. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8640–8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, H.; Choi, Y.; Baniasadi, F.; Hu, D.; Jiao, L.; Park, K.; Tao, C. Visualization of point defects in ultrathin layered 1T-PtSe2. 2D Mater. 2019, 6, 041005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Van de Put, M.L.; Sorée, B.; Vandenberghe, W.G. Critical behavior of the ferromagnets CrI3, CrBr3, and CrGeTe3 and the antiferromagnet FeCl2: A detailed first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 014432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, R.; Yoffe, A. Electronic properties of intercalation complexes of the transition metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Phys. 1987, 36, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, S.S.P.; Marseglia, E.A.; Brown, P.J. Magnetisation density distribution in Mn1/4TaS2: Observation of conduction electron spin polarisation. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1983, 16, 2749–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.W. Antiferromagnetism. Theory of Superexchange Interaction. Phys. Rev. 1950, 79, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 14251–14269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dudarev, S.L.; Botton, G.A.; Savrasov, S.Y.; Humphreys, C.J.; Sutton, A.P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cococcioni, M.; de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA + U method. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 035105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).