Abstract

The traditional power grid is just a one-way supplier that gets no feedback data about the energy delivered, what tariffs could be the most suitable ones for customers, the shifting daily needs of electricity in a facility, etc. Therefore, it is only natural that efforts are being invested in improving power grid behavior and turning it into a Smart Grid. However, to this end, several components have to be either upgraded or created from scratch. Among the new components required, middleware appears as a critical one, for it will abstract all the diversity of the used devices for power transmission (smart meters, embedded systems, etc.) and will provide the application layer with a homogeneous interface involving power production and consumption management data that were not able to be provided before. Additionally, middleware is expected to guarantee that updates to the current metering infrastructure (changes in service or hardware availability) or any added legacy measuring appliance will get acknowledged for any future request. Finally, semantic features are of major importance to tackle scalability and interoperability issues. A survey on the most prominent middleware architectures for Smart Grids is presented in this paper, along with an evaluation of their features and their strong points and weaknesses.

1. Introduction

For the last years, claims for a more efficient energy management have become only more frequent. Besides, governments are more willing than before to become more energy-independent and have a better saying on how energy is being used in each of their nations [1]. Finally, ecological and Earth-friendly concerns are on the rise too; a significant part of the energy that is produced is not properly used, thus putting a strain on the abundant albeit finite resources of the planet [2]. It is in this context where every suggestion to improve energy production and consumption is welcome [3]. However, in order to get relevant information about these two topics it is preferable to gather some data rather than jump to any conclusions. In order to accomplish this task, a system able to communicate through all the stages of power distribution must be implemented, and once enough data has been retrieved, it can be used to influence power generation decisions as well. The usual way to deliver the produced energy comprises several steps: to begin with, energy will be produced at power plants of varying nature (hydroelectric, coal, oil, gas, nuclear-fired, etc.) and once it has been produced in a specific facility it is distributed via the running power grid. Lastly, energy will reach the devices placed within the domain of the interested stakeholders.

As it can be inferred, this is a one-way process with little to no stakeholder involvement. The high voltage grid sends power to local-scaled power distribution systems without any smart decisions being taken. Users are able to provide feedback data about how the power is consumed, but only with time-consuming, attention-demanding procedures. There is a very low amount of decisions that can be made taking that consumption into account, being most of them improvised and linked to peak electrical demand. Therefore, power companies must handle the issue under a rather costly and clumsy procedure that requires profound studies about how to better deal with this question [4]. The proposal of the Smart Grid is supplying all these procedures with a certain amount of information for better decision making. In order to accomplish this task, communications have to be enabled throughout all the components of the power grid, thus enabling a two-way data interchange involving producers and consumers of energy. That is one of the cornerstones of the Smart Grid, because the interchange of information will provide the basis for smart power management, and it can be used to achieve the objectives it was conceived for, such as carbon emissions reduction [5] or a better distribution of low power electricity [6]. Plus, as long as a historical record is stored and can be accessed, other applications as power consumption forecast or consumption statistic can be obtained as well.

1.1. The Advantages of Middleware Architectures

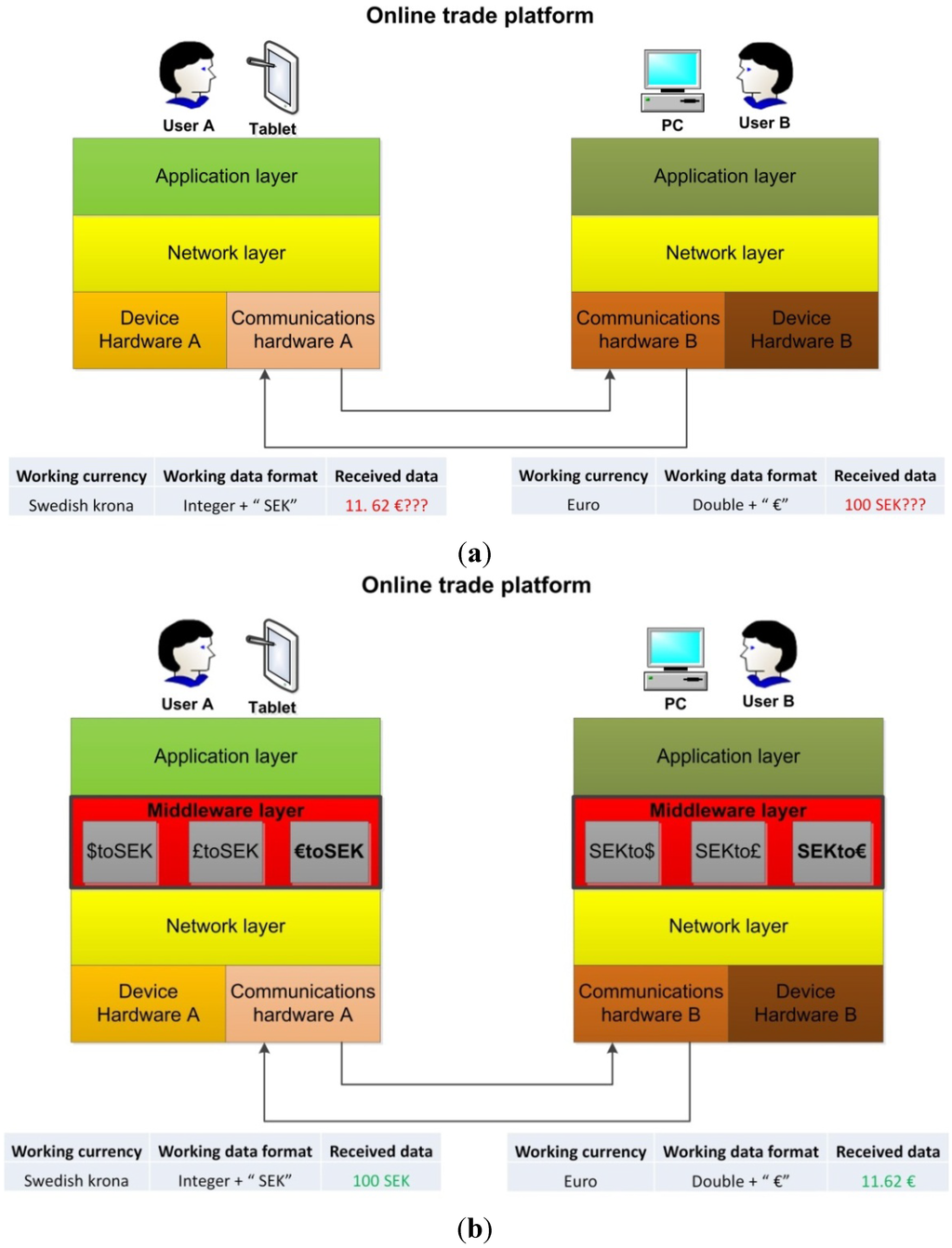

In order to integrate all the different devices that will be providing communication data, a unifying layer is required. This layer will abstract not only all the complexity of the lower components of the Smart Grid used for smart metering and measuring, but also the structure of the power grid, thus keeping the user oblivious from its structure. It is because of this issue that a middleware layer has to be developed, thus integrating the very different components a Smart Grid is equipped with into one homogeneous-looking layer. As displayed in Figure 1a, if an online trade platform is set up and currency exchanges have to be performed, chances are that the platform will malfunction without a middleware layer. At first, there is no problem at the lower layers due to the fact that they are managing Protocol Data Units (PDUs) rather than the application content inside, and as long as the PDUs have acceptable fields in terms of existence and/or length, no issues will appear. However, when that content is accessed by the applications it is very likely that they will present interpretation problems (for example, if it was retrieved from a piece of equipment with a different processor or different byte storage methods). Nevertheless, if a middleware intermediate layer is used, data can be converted according to the needs of a particular application layer, thus solving any format-related issues, as depicted in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) Dissonance between the understandable data format and the one received; (b) Communications system enhanced with a middleware layer.

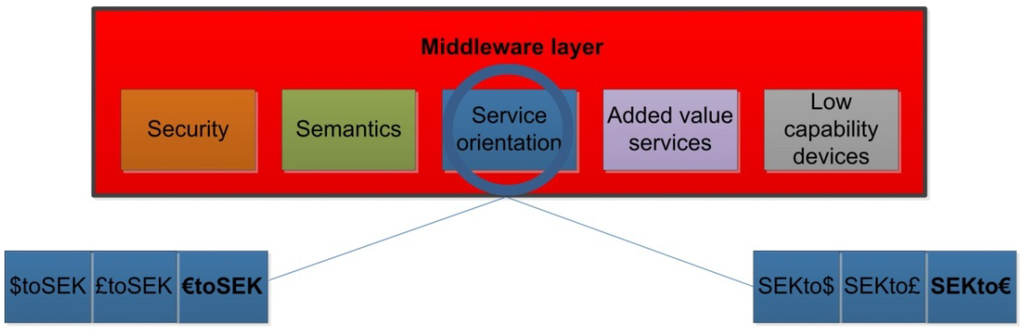

Regarding the Smart Grid, a middleware layer is expected to take into account several features: security for data transfer between entities, semantic treatment of information, service orientation for better user attendance, services that provide an added value to the architecture (such as Quality of Service) and flexibility in order to deal with feedback from low capability devices. In the previous example of the online trade platform, the methods required to interchange currencies could be considered as part of the services that are provided to the end users, and these methods will be encased within the middleware architecture. A more detailed perspective can be obtained from Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Inner view of expected middleware functionalities.

It is worth mentioning that low capability devices are referred to as devices with diminished features both in physical and in computing terms when compared to conventional equipment such as Personal Computers or laptops. Commonly, these are downsized devices that are lightweight and small enough to be placed in locations unreachable with more conventional equipment such as walls, corners or pillars. However, the cost of this portability is paid in other aspects, such as storage capabilities, since very little ROM or RAM memories can be mounted. Processing power is severely constrained too, with microcontrollers falling well below the standards of personal computing. In the context of the Smart Grid, low capability devices are used to collect data from the environment or the context they are placed upon. It is usual for them to be equipped with sensors and actuators for data collection and/or information notification. Depending on the sensors and actuators they are equipped with, low capability devices will be able to measure different variables. Examples of low capability devices are motes from a Wireless Sensor Network, like the ones presented in [7], or RFID tags, as in the GridStat middleware architecture, which is described in the next section.

The need to integrate several different pieces of hardware devoted to monitoring and evaluate the different facilities used for power generation and transmission has been reported and known for several years now; and actually, the term Smart Grid has been in use since at least 2005 [8]. In order to overcome the issues resulting from the need to interconnect several pieces of very different equipment to gather information from the Smart Grid, many different middleware architecture proposals have been put forward. In this context, middleware architectures are employed to gather the data from lower, more hardware-based levels and present it to higher levels, regardless of whether data are coming from one remote place or another, the device used for data collection, etc., Karnouskos [9], for example, talks about how different devices will be used to measure and share energy consumption data at the last mile of the power grid. He also suggests that middleware can be conceived as the “glue” for business-to-device and device-to-device connectivity. For others, like Li et al. [10], middleware architectures must be used for power grid communication, putting forward GridStat as an example. Gustavsson et al. [11] argue that middleware architectures are a critical element to adjust to the challenges that Smart Grid engineering requires. For example, middleware is used for the implementation of service oriented systems, and as a way of implementing functional and non-functional interoperability that is able to meet the wanted Quality of Service features.

Several authors have suggested the idea of providing a middleware architecture that is message-oriented (MOM or Message Oriented Middleware) with the available services accessed via either Web services or a technology that makes use of them. They go even as far as encouraging or designing solutions being able to provide Quality of Service when middleware is implemented. It is not uncommon for middleware architectures to use solutions that will guarantee interoperability among inner components of this layer. The ones that must be highlighted are:

- Enterprise Serial Bus (ESB), a software architecture for interconnecting devices of very different capabilities using software packages named bundles used in middleware architectures as MDI [12], which is described in the following section;

- AMQP [13], which stands for Advanced Message Queuing Protocol, and is used for communications procedures for entities involved in a message-oriented middleware;

- RabbitMQ [14], an AMQP open source implementation that can be used under a publish/subscription paradigm.

1.2. The Advantages of Semantics in Middleware Architectures

In spite of the advantages of middleware architectures in any distributed system—in a way, middleware architectures are de facto compulsory instead of advantageous in distributed systems, as the IT infrastructure of a Smart Grid may be—there are still challenges that must be tackled. Regular middleware architectures are fairly effective interconnecting devices of different nature, but in an environment such as a Smart Grid new challenges must be faced. As an example, dynamic elements that can disappear and reappear in very little time (smart meters or embedded systems encased in white goods that are turned off or on) can easily put a strain on the middleware architecture. These situations call for semantics usage. Generally speaking, and under the scope of information technologies, we consider that semantics can be regarded as the capability to apprehend the meaning and implications of a piece of content that will turn from raw data to processed information. Semantics will provide as a key value the ability to become aware of the meaning of the content at the application layer. What is more, if provided with the suitable equipment—as an inference engine—the application will be able to make choices without needing human intervention, therefore saving power and time for energy users.

By using ontologies, semantic annotations can also be provided. Ontologies describe devices offering data about the features of the device (identification, measuring capabilities, processor characteristics, battery lifetime, etc.) and its services (data required, updates, etc.) thus giving a specific idea of what can be done and with what devices, regardless of their differences in the devices hardware or in what need is solved by using a service. Semantic annotations, on the other hand, can be defined as representations of specific information that is organized according to syntax and hierarchical rules given by ontologies. Examples of ontologies that fit in well in the scope of the Smart Grid are Semantic Sensor Network (SSN) [15] or Standard Ontology for Ubiquitous and Pervasive Applications (SOUPA) [16]. Commonly, they provide tools to either model sensing devices, along with their capabilities—in the case of SSN—or design applications that feed on ubiquitous equipment—in the case of SOUPA. In any case, they are conceived for applications with a high number of devices that strongly resemble the metering and monitoring infrastructure that can be found in the Smart Grid. Ontologies can be generated using tools as Ontology Web Language (OWL). Thus, the data is transferred, processed and stored according to a format and a hierarchy defined by ontology, therefore standardizing the information mapping within a system to an extent.

Finally, another new feature is obtained as a consequence: context-awareness. Since the point of the Smart Grid is collecting information from usual power distribution and consumption centers, the middleware architecture used must be informed about what work conditions there are in the Smart Grid. The idea is that the middleware architecture will react differently depending on how the parameters that measure work conditions may vary during their lifetime, thus providing services in different manners (sources of renewable energy may generate different amounts of power depending on whether the day is sunny, cloudy, windy or not, etc.).

This paper is structured as follows: an introduction on why a middleware architecture, and more precisely, a semantic middleware architecture is desirable for a Smart Grid has already been offered. Section 2 deals with a proposed classification for middleware architectures linked to the Smart Grid, along with the ones that have been found after a thorough survey. Their features, performance, strengths and weaknesses are presented here as well. Section 3 describes the open issues that have been discovered after processing all the data previously obtained in Section 2. Section 4 deals with the conclusions and future works that will be carried out in the light of the survey and open issues. A brief section of acknowledgements and another listing the references will conclude this paper.

2. Survey on Middleware Architectures and Related Works

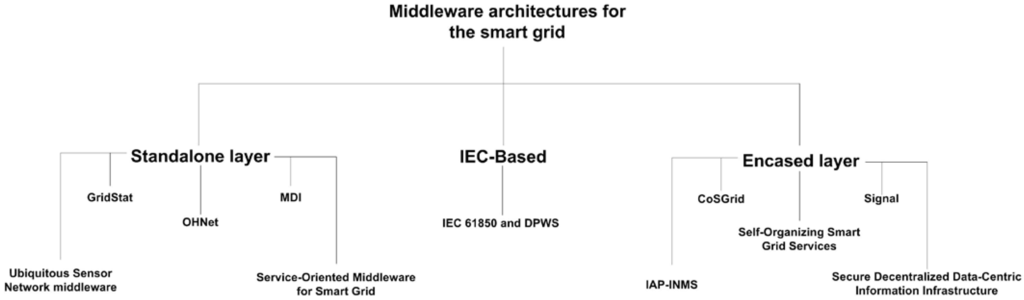

It can be claimed that there are three different kinds of middleware architectures for the Smart Grid: firstly, the ones based on standards published by the International Electrotechnical Commission or IEC—which often combine elements of already established solutions, such as IEC 61850 or IEC 61970 in [17] or [18]—to provide middleware functionalities in Smart Grids. Secondly, another different kind where middleware architectures are conceived as a standalone layer that exists independently. Finally, a third group where middleware architectures for the Smart Grid must be encased in a particular architecture and have less strict boundaries. All these architectures have been surveyed and are described in the following sections.

2.1. GridStat

GridStat has been designed with the purpose of having a middleware layer capable of keeping pace with the data collection capabilities of the equipment present in the power grid [19]. It is claimed by its authors to tackle latency and reliability issues that may be present when transferring data.

2.1.1. GridStat Features

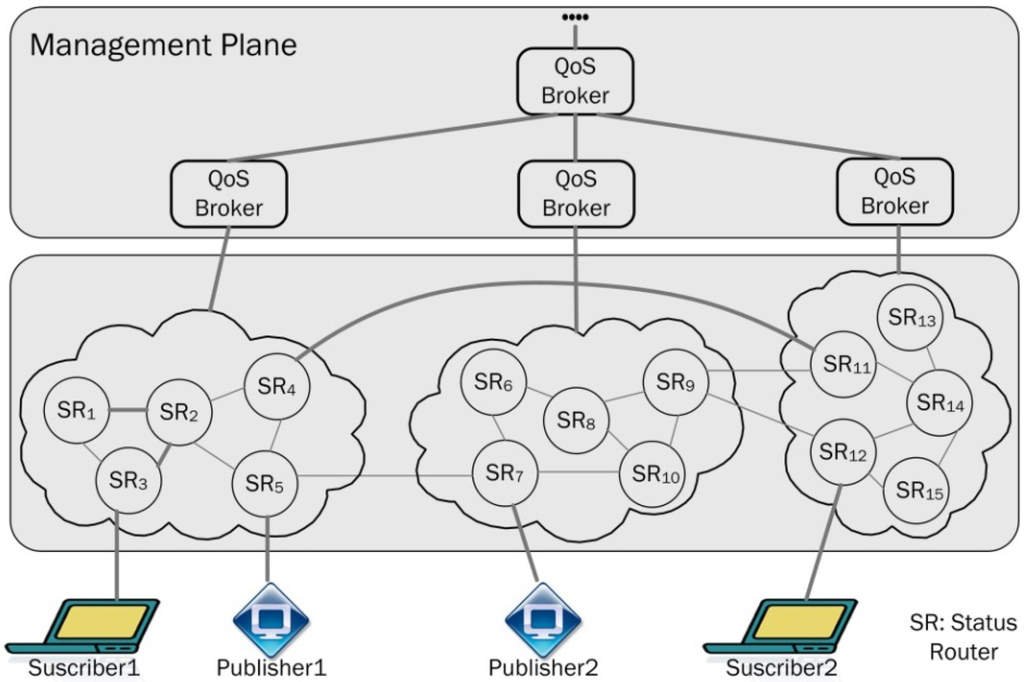

The GridStat architecture has been designed considering two different levels or planes: a management plane—charged with resource allocation and data adaptation regarding changing circumstances, as power configurations and system failures—and a data plane—the layer that will forward data from the sources to the destinations depending on the orders of the management plane. Each of the levels has several inner components as well: within the data management plane there are several entities named QoS brokers organized according to a hierarchy (where the lowest level QoS brokers are named leaf QoS brokers and will interact with the data plane). At the data plane, though, there will be several, plainly organized status routers that will be connected to equipment able to process requests and responses following a publication-subscription model for their communications. Several status routers will be managed by one leaf QoS broker in a cloud. An overview of GridStat architecture is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

GridStat architecture as described in [19].

In this middleware architecture, command interactions and forwarding interactions are the only ones that will take place, and they will be done so using an event channel, which is an entity used for intercommunication purposes between status routers that publishers and subscribers are connected to. Additionally, several components have been defined in order to provide physical implementations of the theoretical concepts presented, as it has been listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of GridStat main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Electronic Product Code information services module | Made of two parts: an AAM repository for information storage retrieved by RFID tags and a service engine AAM repository management interfaces belong to. |

| Object Name Service | A directory service. It matches AAM server network addresses with tag codes. |

| Reader interface module | Integration features for tag readers. Tag information is read by means of the interface of this module. |

| Data dump module | Data makes use of a C++ implementation based on the CIM model to define relations among power systems. |

2.1.2. GridStat Performance

Typically, a publisher will advertise the availability of its data streams to the management plane via an API that will also be used for data requests, regardless of the intermediate network technology. Afterwards, the QoS broker announces both what publication is available and the publication rate (for example, in monitoring applications). In the end, the status router will forward incoming pieces of data through the event channels, according to the subscriptions made and the rules determined by the management plane.

2.1.3. GridStat Strengths and Weaknesses

GridStat is an ambitious and detailed approach on middleware for the Smart Grid, feeding on communication capabilities and hierarchy to provide its facilities. However, there are several issues that must be born in mind. Testing for this architecture was made using hardware devices far more powerful than those that may be present in a Smart Grid development at a home or a facility (home loads as a television or a washing machine enhanced with an embedded system, smart meters scattered around a dwelling, etc.). Plus, GridStat does not implement any mechanism that uses semantics, thus resulting in not a semantic annotation on services or devices, which results in an underperformance of the whole system.

2.2. Service-Oriented Middleware for Smart Grid

Zhou and Rodrigues put forward a service-oriented middleware for Smart Grids, thus stressing the concept of obtaining services as the driving motivation for Smart Grid deployment [20]. The authors claim that their middleware solution is able to tackle issues related to heterogeneous services, which are the most usual ones in the Smart Grid domain.

2.2.1. Service-Oriented Middleware for Smart Grid Features

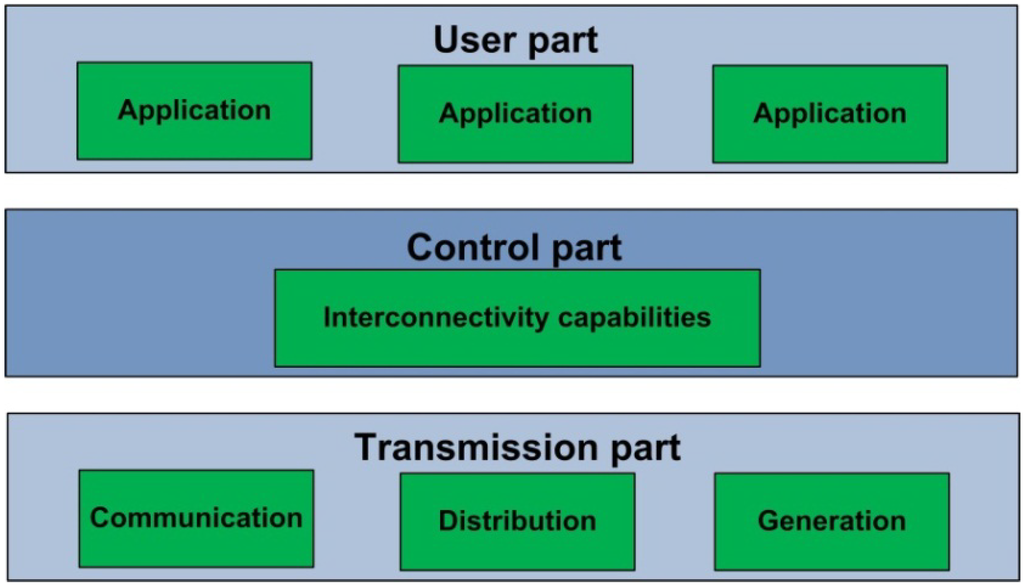

The authors have conceived their middleware architecture as one that is service-driven, user-centric and specifically designed for the requirements of the Smart Grid. They consider several design principles that are critical for any current middleware implementation: independence from any kind of device to spread usage, interoperability, portability, backing for computational variety in heterogeneous applications and clear relations between middleware functions and user requests. Therefore, the proposal focuses on obtaining a heterogeneous service infrastructure capable of dealing with devices of multiple objectives. This infrastructure is made up of three different layers: a transmission part, a control part and a user part. The transmission part can be divided into three smaller components (generation, distribution and communication); it is a layer used for adaptive meter infrastructure data transfer—which involves energy consumption—around a networked area. The control part, on the other hand, is mainly used to connect transmission and user parts, and is placed between the former two. The control part uses a mechanism designed for management between the different connected devices at the transmission part and Quality of Service and experience improvement at the user part. This latter part provides a certain performance of jitter, reliability, bandwidth or delay, which are features regarded as cornerstones for the facilities that will be offered by the application layer. A layered representation of the architecture is presented in Figure 4.

Additionally, a list of each of the layer inner components and what is expected from them is shown at Table 2.

Figure 4.

Service-Oriented Middleware for Smart Grid, as described in [20].

Table 2.

Description of Service-Oriented Middleware for Smart Grid main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Transmission part | Transmits electrical power from generation To distribution centers. Made up by generation, communication and distribution modules. |

| Control part | Device management between transmission and user parts. Made up by security, management and assignment modules. Exchange modules as bridges with the other two parts. |

| User part | Integration features for tag readers. Made up by bandwidth, applications and Consumption modules. |

2.2.2. Service-Oriented Middleware for Smart Grid Performance

According to the authors, their design of a service-oriented middleware was made bearing in mind cognitive radio-based applications, spectrum efficiency and application security. The architecture was tested by measuring several different steps (access control, message transmission, power allocation and service quality) by using a network simulator. It has been compared to two other proposals—Power-Aware Middleware [21] and Time-Driven Middleware [22]—with a growing number of simulated users (from 10 to 40) showing better results in terms of Mean Option Score.

2.2.3. Service-Oriented Middleware for Smart Grid Strengths and Weaknesses

This proposal seems to be fairly suitable for typical middleware duties, and the authors are aware of the lack of development in the Smart Grid as far as middleware architectures are concerned. Unfortunately, it does not enable any mechanism to make the middleware architecture aware of the kind of device it is dealing with (by means of a semantic description) or is not making the services aware of the context where they are executed (it is not making use of semantically annotated services). In addition to that, the results that have been obtained are a result of a simulation instead of data obtained from actual devices. Finally, the standard deployed during the testing (802.11b) may overwhelm the possibilities of many low capability devices use for data harvest, which are more likely to use other standards like 802.15.4.

2.3. Ubiquitous Sensor Network Middleware (USN)

Another appealing proposal is the one made by Zaballos et al., where sensor networks are mentioned as agents able to provide information [23]. According to their view, middleware functionalities may involve quality of service, security or filtering, and they will be tackled by using what they call USN (for Ubiquitous Sensor Network) Middleware.

2.3.1. USN features

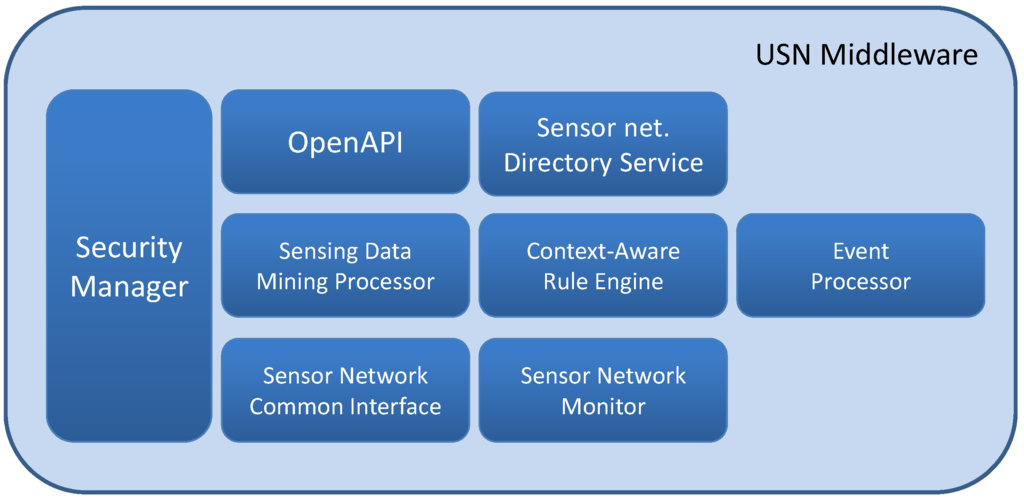

USN Middleware is divided into three sub-layers, each of them with their own security manager but differing in all the other components. The lower one, and the closest to the hardware devices, will be devoted to a sensor network common interface and a sensor network monitor (apart from their own level security manager). The second one is used to equip somewhat semantic capabilities: a sensing data mining processor, a context-aware rule engine (to infer behaviors onto the system taking into account the context it is involved in), an event processor and the level Security manager. Finally, at the highest layer—which is the one that will be in touch with the foreseeable applications, as AMI-related requests and responses, distributed generation, demand response, supervision and vigilance, etc.—in addition to the level security manager, an Open API and a sensor network directory service are employed. Figure 5 shows the inner components of the architecture.

Figure 5.

Ubiquitous Sensor Network middleware, as described in [23].

In order to provide an accurate description of the middleware architecture, its main components have been summarized at Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of Ubiquitous Sensor Network middleware components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Lower layer | The layer closest to the hardware infrastructure. It is made by a security manager, a sensor network common interface and a sensor network monitor. |

| Medium layer | A go-between between the upper and the lower level. Made up by a security manager, a sensing data mining processor, a context-aware rule engine and an event processor. |

| Higher layer | The nearest layer to the applications. It is made up by a third security manager, an open API and a sensor network directory service. |

2.3.2. USN Performance

As expected, the middleware layer will interact as a messenger between the sensor network and the applications of the upper layer. Open Service Environment (OSE) is used to implement the different functions and the business intelligence that must be used to implement the middleware architecture. Their proposal will also make use of Power Line Communications or PLC to enable the communication network.

2.3.3. USN Strengths and Weaknesses

An effort has been made by the authors to provide a middleware capable not only of using sensor networks, which effectively match the concept of low capability devices, and adding some semantic features, as a context-aware rule engine. However, the authors have used Common System for Middleware of Sensor Networks or COSMOS [24] as a reference for their own middleware, and although the latter was conceived for sensor networks with heterogeneous components, it has not been explicitly designed for its usage in Smart Grids, nor does implement any mechanism to obtain any semantic added value. Furthermore, not many details are provided about how the inner components of the middleware architecture are made and what specific functionalities are performed.

2.4. OHNet (Object-Based Middleware for Home Network)

Kim and Kim, on the other hand, proposed a middleware architecture based on objects that will interact between home devices and the ones that belong to a Smart Grid [25]. This middleware, that has been named Object-based Middleware for Home Network (OHNet) by the authors, can be employed by the final user to their advantage, as they can schedule home electricity consumption during off-peak periods of time.

2.4.1. OHNet Features

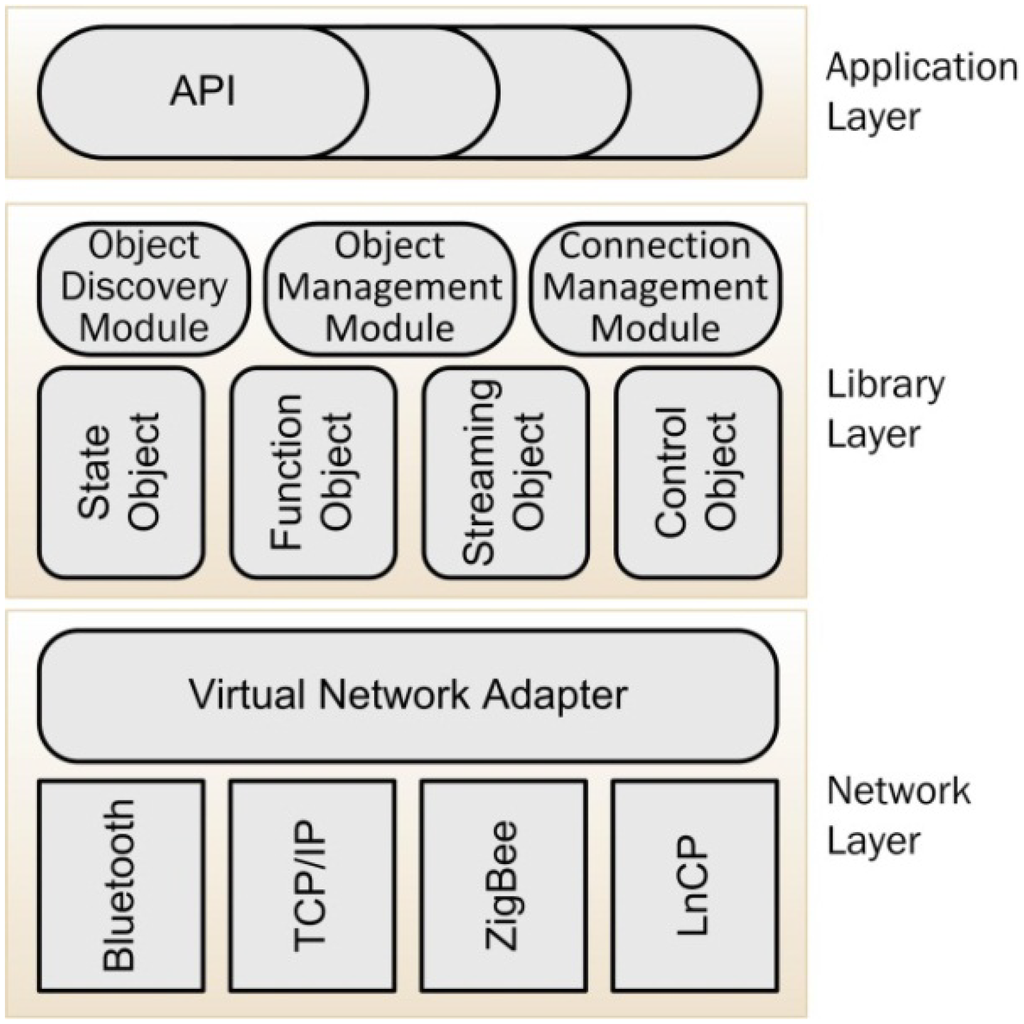

OHNet is made up of three different components, namely the Network, Library and the Application layer, each of them with their own inner components. The network layer makes use of a Virtual Network Adapter or VNA to provide abstraction for various protocols and therefore making them equally accessible. Coincidentally, the VNA is making use of a routing table (Device Routing Table or DRT) with information regarding the kind of protocol used or the identification of the device that will come in handy to route data. At the same time, the library layer will provide information from the home devices by means of four different objects (State, Function, Control and Streaming objects) and three different modules (Object Discovery, Object Management and Connection Management modules). Finally, while the application layer is not properly a part of the middleware architecture, it will offer APIs to the users (Initialization, Discovery and Description) that want to access the services that can be provided. Figure 6 displays the main components of OHNet.

Figure 6.

OHNet components, as described in [25].

Furthermore, the components of this middleware layer are presented in Table 4 so as to aim at what functionalities can be retrieved.

Table 4.

Description of OHNet components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Application layer | Use for application requests and responses. It is made up by Application Programming Interfaces. |

| Library layer | Made up by an object discovery module, an object management module, a connection management module and several objects (state object, function object, streaming object, control object) |

| Network layer | This module tackles the communications. It is made by a virtual network adapter working with TCP/IP, Bluetooth, Zigbee and LnCP. |

2.4.2. OHNet Performance

The architecture has been tested using physical devices: embedded boards representing a heater, a clock, a laptop, a smart phone, etc., and Smart Grid-based devices as a battery, a solar power generator and a smart meter. Connections were guaranteed by using either a TCP/IP architecture or Bluetooth for interoperability purposes. As smart meters are equipped with Device Routing Tables, they will send messages requesting electricity data to the laptop, which forwards it to the appropriate piece of equipment that will offer the answer that is then retrieved.

2.4.3. OHNet Strengths and Weaknesses

This proposal is effective when it has to interconnect home devices with a Smart Grid, and actual devices have been used to test its performance and behavior rather than any simulation. It does not, however, specifically take into account any low capability device that may be used by the Smart Grid, not is using any semantic added value to enhance its own capabilities. Plus, it is limited to a home environment, not offering any data about performance in a scenario of different characteristics (for example, a factory), nor considering interaction between several environments.

2.5. Meter Data Integration (MDI)

Li et al. [12] suggest what they have called a “Unified Solution for Advanced Metering Infrastructure Integration” with a layer named Meter Data Integration (MDI) that can be used for the middleware level. Among its functionalities, it is primarily used for unifying Advanced Metering Infrastructures and Distribution Management Systems. The authors stress their efforts in integrating the Advanced Metering Infrastructure with the Distribution Management System (DMS), dealing with the challenges that may pose in terms of information models and communication protocols, and where their MDI layer is placed.

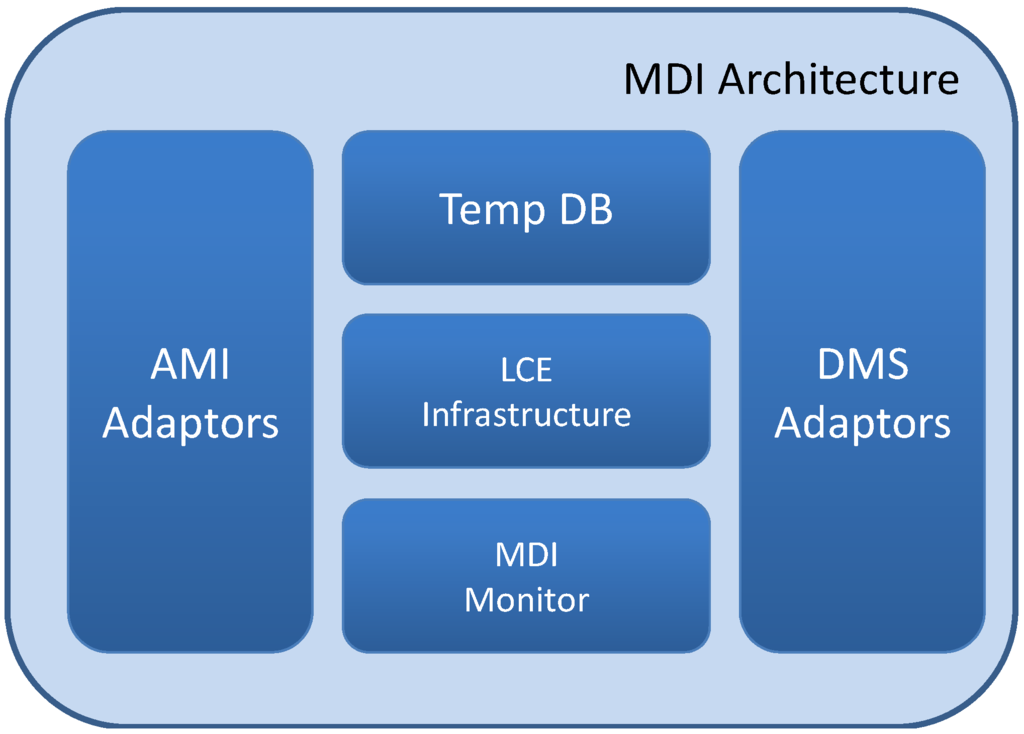

2.5.1. MDI Features

The MDI layer is involved in a system as the interconnecting part between AMIs and DMSs, so it must be able to connect with different kinds of communication protocols and smart meter data models. Depending on the requirements of the device, the MDI layer can be used with an Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) or a system for Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA). The components used to design this layer are: AMI and DMS adaptors (for the data incoming from Advanced Metering Infrastructures and Distribution Management Systems), an Information Translation and Verification Structure (used in order to eliminate the information gaps between AMI and DMS systems and having the latter ones as equipment compliant with IEC 619868-9) and a MDI monitor (put to a use to track the status of the different components of the MDI layer). There are several components MDI is made of: AMI adaptors (adapted to different sorts of AMI data), Information Translation and Verification Structure (used to do away with information gaps between AMIs and DMSs), Loosely Coupled Event Infrastructure (acts as the messaging infrastructure of the MDI layer), DMS adaptors (mirroring the design decisions of AMI adaptors) and MDI Monitor (used to track the status of the functional components of the MDI layer). They are all depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

MDI components, as described in [12].

Table 5.

Description of MDI main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| AMI adaptor | It is used for data transfer between AMIs and DMSs. They transfer meter data and metering information. |

| Information Translation and Verification Structure | Uses information mapping to remove information gaps between AMIs and DMSs. |

| Loosely Coupled Event Infrastructure | Messaging infrastructure. Functional components are coordinated by publication or subscription against this entity. |

| DMS adaptors | Data transfer between DMSs and AMIS. They take into account throughput limitations. |

| MDI Monitor | It will track MDI components by using Loosely Coupled Event subscriptions. |

2.5.2. MDI Performance

When designing a MDI layer, the authors name a plethora of challenges that must be taken into account: performance, scalability, adaptability and extensibility. Typically, MDI layer will work supporting three different kinds of actions: AMIs publishing meter data to the DMSs, DMSs polling meter data from AMIs and DMSs pushing control commands. Operations at the MDI layer will be using data and control information as inputs or outputs and Enterprise Service Buses, SCADAs or Web Services as the medium for queries and responses.

2.5.3. MDI Strengths and Weaknesses

This middleware layer is integrating trusty technology to solve interoperability issues (like the Enterprise Service Bus) and it is likely to have a high level of reliability. However, it appears as it has been conceived merely to integrate data of different nature. Therefore, it is not capable of providing any added semantic value to the information that is integrated, nor it uses the capabilities of the Common Information Model that is frequently used in Smart Grid architectures.

2.6. IEC 61850 and DPWS Integration

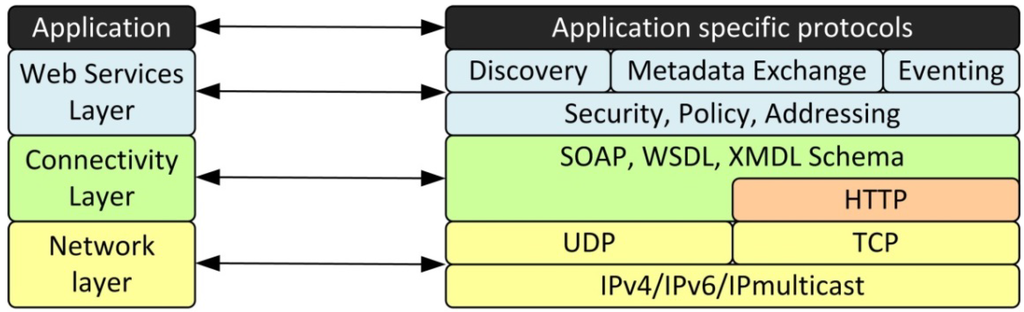

Sucic et al. [26] suggest an integration between IEC 61850 standard (a standard for the design of Ethernet-related devices in industrial environments [27]) and Devices Profile for Web Services (DPWS, a standard used for communications involving low capability networks [28]). The authors regard the latter as a suitable middleware architecture and claim that the whole system it is a standard compliant, event driven Service Oriented Architecture for semantic-enabled Smart Grid Automation.

2.6.1. IEC 61850 and DPWS Features

According to the authors, IEC 61850 is capable of defining future-proof automation architecture for power systems, and uses to do so three different characteristics: a semantic data modeling (divided into an application scope—made of a data set and functional constraints—and an information modeling scope—made up by servers, logical devices, logical nodes, data objects and data attributes), data-exchange services (using several model classes for vertical communications—association model, server models, setting-group-control-block model, control model, log-control-block model and report-control-block models) and some more features for management and engineering of IEC 61580 systems (XML files formatted with regards to the System Configuration description Language). The authors also highlight the semantic capabilities of IEC 61850, which makes use of a mechanism called Abstract Communication Service Interface or ACSI to establish a link between the abstract services of IEC 61850 and application layer-related implementations. Despite this, components from IEC 61850 are lagging behind due to the fast Smart Grid development, and therefore must be enhanced, putting forward DPWS for its common use on event-driven and service-oriented architectural principles. The authors support the idea of integrating the ACSI functionalities into a middleware based on DPWS: since DPWS distinguishes between hosting devices and hosted services, a DPWS-based IEC 61850 implementation could provide Service Oriented Architecture-ready devices with hosted exchange services. These would be based on ACSI at a hosting device, related with Web Services as Discovery, Description and Eventing (the latter one related just to report-control-block), as depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

IEC 61850 and DPWS components, as described in [26].

Similarly, the main components of this middleware proposal have been presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Description of IEC 61850 and DPWS main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Hosting device | Appliance used for service storage. |

| Hosted services | Customized application functionalities. They are represented by model classes for vertical communications. |

2.6.2. IEC 61850 and DPWS Performance

The authors have made efforts to provide an event-driven data exchange architecture under a publish/subscribe mechanism as expected from IEC 61850. Three basic services are contemplated: one used for managing settings or Report Control Block (RCB) objects at the server side, another one for RCB object settings retrieval from the server, and a third one supporting a spontaneous data delivery mechanism. Smart Grid architectures can be dynamically managed too: the WS-Discovery specification allows having Smart Grid devices discovered, and DPWS device functionality description uses WS-MetadataExchange as a retrieval procedure for metadata relying on hosted services, which provides the foundations for self-descriptive IEC 61850 devices.

2.6.3. IEC 61850 and DPWS Strengths and Weaknesses

Despite the step forward in access ease and the addition of some semantic degree to the proposal, it has several weaknesses. DPWS dependence on Web services does not seem to fit perfectly with the requirements of a Smart Grid, which is much more likely to work under an event-driven model than a request-response one, as it is acknowledged by the authors. Additionally, the somewhat large capabilities that Web services and DPWS require in terms of computation may be a hindrance for a Smart Grid, where low-capability devices are often used and segmentation of packets may be required. Lastly, the semantic component introduced by the usage of DPWS does not mention the usage of extended semantic mechanisms, such as ontologies for device and service description and annotations, or a language to create ontologies as OWL.

2.7. IAP-INMS

García et al. [29] put forward a distributed software architecture that aims to manage the different devices that can be found in a Smart Grid. The authors claim that there is a need for Integrated Network Management that can be provided via software agents. Under this implementation, an event-based, real time middleware architecture is mentioned as a requirement to interchange data between the different agents, along with other tasks focused on control. This proposal has been named after the name of the company it has been developed at (IAP) and Integrated Network Management.

2.7.1. IAP-INMS Features

The authors claim that there are several functional blocks that must be considered, according to their reviewed reference architectures: fault handling, events and alarm management, performance management, security management, configuration management, device management and integration capabilities. Each of this functional blocks results in several management features (status monitoring, statistics generation, authorization, authentication, smart devices provisioning, time alignment, interface activity recording and audit, etc.) that will have to be dealt with. The intelligent software agents paradigm is put to a use here by employing the main properties of software agents (claimed to be social capabilities, autonomy, proactive intelligence, temporal continuity, mobility, rationality in global goals and learning ability) for service implementation. As for the architecture itself, there are three different layers that must be highlighted: a Network Mediation layer (which has as its major aim processing data flows from and to the Smart Grid devices and is in charge of communications with Smart Grid devices), a Management Application layer (made by applications operating in backend systems) and a Middleware Communication Services layer (used for interoperability between the other two layers). All these layers are used within an Intelligent Agents Platform that has been tested. Table 7 is showing the main components of the architecture.

Table 7.

Description of IAP-INMS main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Mediation layer | Process data flows in a distributed way. Made by Mediator Systems containing Intelligent agents that communicate with an internal event-bus middleware. |

| Management Application layer | Provides management applications. Made by Application Backends containing Intelligent agents that communicate with an internal event-bus middleware. |

| Middleware Communication Services | Act as a go-between for Mediation and Management Application layers. |

| Intelligent Agents Platform | Middleware is deployed here. It contains intelligent agents. |

2.7.2. IAP-INMS Performance

IAP-INMS architecture was tested on an IP service access network based on BPL devices designed for an Advanced Metering Infrastructure network with an AMI concentrator. Each concentrator is monitoring 10 variables at each of the AMI counters while polling them every 15 min. Tests were run using a low bandwidth access network—128 kbps—between the mediation layer and the concentrators accessing to the AMI counters. Other tested features were the application management layer and several other deployed applications at the backend side (alarm management, performance monitoring, provisioning, usage data collection, etc.).

2.7.3. IAP-INMS Strengths and Weaknesses

This middleware architecture must be credited for adding several features that are of certain importance in order to get a state-of-the-art middleware architecture, such as software agents and semantics. Unfortunately, there are very few mentions about how ontologies and the inference engine are used, along with other kind of desirable security characteristics. Alas, low capability devices, which are likely to be found in a metering infrastructure, are not considered under this development, except for low bandwidth mentions without further specification.

2.8. CoSGrid

Villa et al. [30] have created what they call a “Dynamically Reconfigurable Architecture for Smart Grids”. The authors claim to make use of a proposal based on what they have named Controlling the Smart Grid (CoSGrid), which contains an Object Oriented communication middleware as part of the whole project, and has as final goal using a set of devices that has the same information model.

2.8.1. CoSGrid Features

The authors conceive the system made up of components that can be managed as objects relying on the same information model. In this way, they will be able to establish logical relations among the different components. What is more, the components attempt to retrieve information from any device that can be expected inside a Smart Grid (hence their need to create an Embedded Meter Device able to fulfill this requirement). All in all, the authors claim that their proposal is made by four different entities: communication middleware (being inspired by CORBA, it is a collection of distributed objects able to share information by means of remote method invocations), Embedded Meter Device (a device ensuing sensing and actuating hardware that will be presented as a distributed remote object), an information model (a collection of abstractions to model and design platform services as distributed applications) and a group of core services with reconfiguration and aggregation features. Table 8 displays the most important components of this architecture.

Table 8.

Description of CoSGrid main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Communication middleware | CORBA-based, distributed queries are made. It must provide a well-known interface for clients. |

| Embedded Meter Device | A hardware device containing components used for handling Smart Grid usual requests and responses. |

| Information Model | Abstractions required for object modeling. There are five non-exclusive categories (metering, state control, notification, node aggregation, data aggregation). |

| Core Services | Data aggregation or composition. Service discovery protocol. |

2.8.2. CoSGrid Performance

Their middleware layer works as a client-server architecture, enabled with Web services to retrieve the wanted services. As in CORBA, a service invocation from the client to the server will be using a method of a reference belonging to a proxy that will be coded and sent through the network to the server. Once there, the information will be decoded by making use of a skeleton, which is likely to have been generated in an automated fashion, and is making use of the tools typical of middleware distributions to have classes (Stub, Skeleton, etc.) automatically generated. It is with this layer of middleware that what the authors call Embedded Meter Devices—measurement elements that are built using a specific approach for low capability hardware devices named picoObject—are used to collect data. When these data are collected, they will be done so by using an information model involving measuring, event notification and data aggregation.

2.8.3. CoSGrid Strengths and Weaknesses

The proposed middleware architecture and the information model are conceived in a way that they match most of Smart Grid applications that can be expected. Unfortunately, it also has limitations: unlike Embedded Meter Devices, the suggested middleware layer is not taking into account the low capabilities of the devices that are used for collecting information. What is more, the information model does not make use of any semantics or ontology engine, thus crippling its possibilities of making an adaptive, flexible middleware.

2.9. Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services

Awad and German propose Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services [31], expected to make decisions both locally and in a distributed way in an autonomous manner. Rather than providing explicit middleware architecture, the authors suggest an algorithm that could be place at the core of it, and used specifically in a Smart Grid.

2.9.1. Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services Features

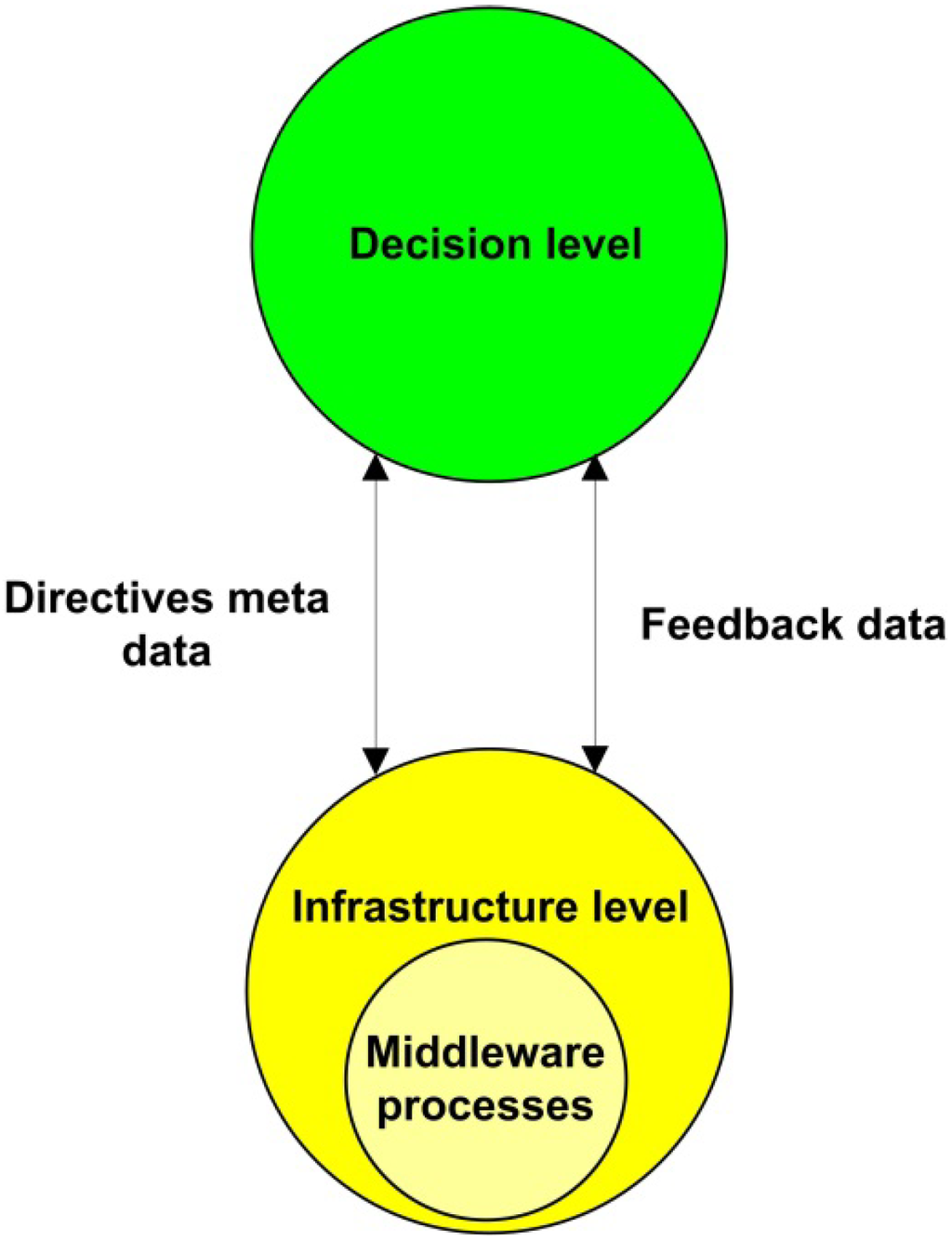

The authors emphasize the advantages that self-organizing solutions pose for the Smart Grids: they enable autonomic behaviour from participating nodes, show adaptive adjustment, enable reliable services in unreliable environments, work under conditions where interaction patterns are not foreseeable, minimize maintenance requirements and offer scalability. In order to guarantee these solutions, this proposal is divided into two different levels: infrastructure and decision. Middleware is explicitly used at the infrastructure level for service provisioning as data aggregation, routing, data replication and data filtering. Typically, infrastructure level receives data from the decision level aimed at taking a decision at the former level, which may use even cloud resources to complete its duties. Decision level, on the other hand is using a meta-model focused on providing the semantics required for the infrastructure level processes. It is made up by four entities: required information (in order to define the type of data required), design process (actions to solve a problem are considered here), distributed data base (in order to get needed information) and service controller (if the required information is not available and services must be triggered to obtain it). An overview of the proposal can be watched at Figure 9. All the features that have been described before have been summarized and presented in Table 9 as well.

Table 9.

Description of Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure level | Receives directive meta data from the decision level and provides feedback data. |

| Decision level | Requests data to the infrastructure level so as to take decisions. It is composed by several entities: required information, design process, distributed database and service controller. |

Figure 9.

Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services components, as described in [31].

2.9.2. Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services Performance

In order to illustrate the advantages of the Smart Grid, a scenario is offered where a Smart Grid is deployed and energy is provided via several energy sources. If a switch involved in the power transfer is damaged, the power grid can reconfigure itself automatically to guarantee power supply, instead of having customers contacting the power company. In addition to this use case, the authors put forward several metrics to measure how good a self-organizing service is: Degree of Scalability, Degree of Robustness (takes into account adaptability and resilience), Degree of Target Orientation, Degree of Emergence, Degree of Flexibility, Degree of Reliability and Degree of Parallelism (how nodes join or leave a system from different sides at the same time).

2.9.3. Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services Strengths and Weaknesses

Although putting to a use a dynamic meta-model is an interesting idea, it is done so at the decision level, not at the layer where the middleware architecture is present, and the mechanisms that are used by the middleware for accomplishing its usual tasks are not explicitly mentioned. As it happens with many other proposals, there is very little information about semantic contents, and whether semantic annotations are offered in services or device descriptions is not known. It is not clear how tests are being done either.

2.10. Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure for Smart Grid

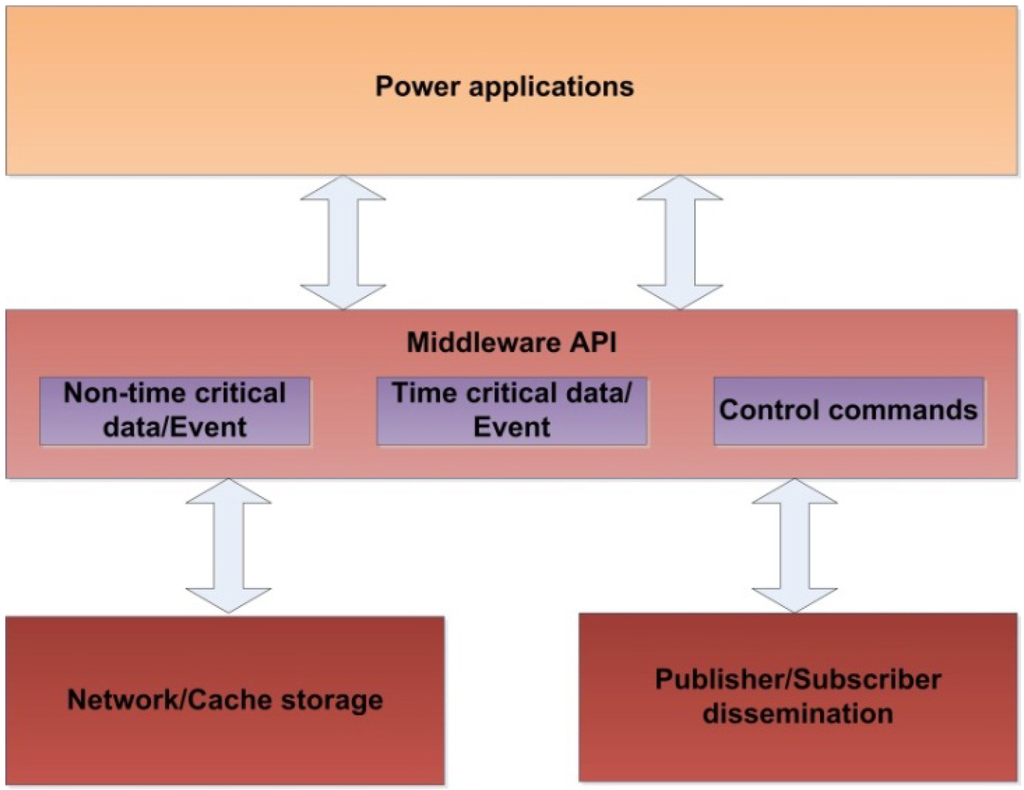

Kim et al. [32] put forward their own middleware architecture that has been labeled as a Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure for Smart Grid. IP is explicitly used at the communication layer, and the authors claim to have tackled the specific issues of power-related applications (distributed data sources, latency-aware data transactions, security or real-time event updates).

2.10.1. Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure Features

The middleware architecture presented here will be containing three different components: a non-time critical data event module (for data that are able to admit some latency), a time critical data event module (that will be somewhat involved in a distributed network storage system for this kind of data) and a control commands module (in order to get control information). These components, along with their relations with upper and lower layers, have been illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure components, as described in [32].

The authors deem their proposal as easily improvable by adding self-healing and self-configurability capabilities. Decentralization is also pursued in order to solve several issues (scalability, bottleneck issues). Other implementation issues have been treated too: naming, routing and forwarding are dealt with control entities keeping IP addresses assigned to the elements belonging to the domain; Common Information Model is used as a way to obtain a standardized data format too. Security is also taken into account: each of the communication channels use a key securely derived by the involved users based on their credentials by employing a key exchange or KE. The main features of this middleware architecture can be observed in Table 10.

Table 10.

Description of Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Non-time critical data event module | Entity used for data transmission for non- critical data related to events. |

| Time critical data event module | Entity used for data transmission for critical data related to events. |

| Control commands module | Entity used for commands related with control functionalities. |

2.10.2. Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure Performance

As in other implementations, a publish-subscription model will be put to a use in order to support middleware. Alas, a network storage capability and a pull-based access to the data will be used too; at the same time, a lower security grid overlay network will be employed to have security in the development that is used to prevent distributed denial of Service (DoS) attacks.

2.10.3. Secure Decentralized Data-Centric Information Infrastructure Strengths and Weaknesses

Although the efforts in security have to be applauded, the other features of the proposal are not offering any solution for semantic treatment of information. Besides, very little about the technologies that are used for the implementation of the middleware layer is provided, along with how the inner components of the middleware architecture are built inside, aside from their obvious functionalities.

2.11. Middleware Services for P2P Computing in Wireless Grid Networks (Signal)

Hwang and Aravamudham deal with Middleware Services for P2P Computing in Wireless Grid Networks [33]. According to their view, in order to better provide grid-based services a scalable middleware is required, thus suggesting their own proposal, named Scalable Inter-Grid Network Adaptation Layers (Signal).

2.11.1. Signal Features

The idea behind Signal is that a low capability device, as a mobile phone, can be enabled to have a much higher than expected output by making use of P2P technologies across a grid. This is a proxy-based middleware proposal supported by employing Globus (a project bent on computational grids rather than middleware for Smart Grids [34]). This proposal uses data prefetching and caching procedures at the middleware layer to improve the overall performance of the system, and will provided Quality of Service related facilities (support for resource and service discovery, QoS guarantees provision, etc.). Several components are used with the aim of providing more scalable and intelligent resource management, according to the fundamental goals of a middleware architecture: a Registry/discovery service module (communicating with devices of different nature to register services), a proxy level (so as to communicate devices and computational resources offering intercommunicating proxies) and a job computational level (intended for storage devices, computational resources or memory). The main components of Signal have been summed up in Table 11.

Table 11.

Description of Signal main components.

| Main components | Description |

|---|---|

| Registry/discovery service module | Entity that makes use of SOAP over TCP/IP to register and discover services. |

| Proxy level | It provides caching, QoS and application independence for mobile phones. This entity is made of several inner proxies. |

| Job computational level | Entity made by computational grids containing computational facilities. |

2.11.2. Signal Performance

Usually, it will work by sending requests to the remote locations capable of replying the requests given the resource availability of the moment. In addition to that, the Open Grid Services Architecture’s (OGSA’s) web extension is used to access the services that can be potentially provided by means of Web services that are stored in a UDDI registry with XML descriptions. When the mobile device has to communicate with the proxy, it will be done via SOAP and securely authenticating each other by means of Generic Security Service (GSS).

2.11.3. Signal Strengths and Weaknesses

Signal makes use of specific low capability devices as mobile phones (although it can be disputed whether mobile phones can be regarded as low capability) and makes use of technologies with close ties with other middleware architectures, such as Globus. Unfortunately, it is oblivious about adding a semantic value to the information gathered that goes beyond Web services. Additionally, devices less powerful than a mobile phone may be used so as to collect data from a Smart Grid.

3. Taxonomy on Middleware Architectures for the Smart Grid

Considering all the different surveyed middleware architectures and the main characteristics they share, a taxonomy has been created so as to have a more holistic view of all the middleware architectures available. It is presented in Figure 11.

It must be remembered that usually, the idea of designing a middleware architecture trying to meet one particular purpose presents both advantages and disadvantages. Standalone layers tend to be more strongly defined in terms of scope and objectives, but may require an extra effort to adapt to other architectural components. Middleware layers encased as part of a wider architecture are already adapted, but their functionalities and purposes are sometimes blurry. Finally, middleware architectures using IEC standards take power industry developments into account, yet they may not be suitable enough when low capability devices are integrated in the Smart Grid.

Figure 11.

Taxonomy on middleware architectures for Smart Grids.

4. Open Issues

As it can has been learnt from the previous section, there is a plethora of middleware architectures, often with very different characteristics not easy to grasp. For a more holistic idea, the most notorious capabilities of the reviewed middleware architectures have been extracted. Firstly, the middleware architectures have been evaluated according to what they are capable of offering, considering a fixed set of parameters, as it has been displayed in Table 12.

Table 12.

Main features of the surveyed middleware architectures.

| Middleware architecture | Low capability devices | Semantics | Security | QoS | Service orientation | Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GridStat | No | No | No* | Yes | Low | Yes |

| Service-oriented middleware for Smart Grid | No | No | Yes | Yes | High | Yes |

| USN middleware | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Medium | No *** |

| OHNet | No | No | No | No | Low | Yes |

| MDI | No | No | No | No | High | Yes (sim) |

| DPWS + IEC 61850 | No | Yes ** | Yes | No* | High | No *** |

| IAP-INMS | No | Yes ** | Yes | No | Medium | Yes |

| CoSGrid | Yes | No | No* | No | Medium | Yes |

| Self-organizing Smart Grid services | No | No | No | No | High | No *** |

| Secure decentralized data-centric | No | No | Yes | No | Medium | No |

| Signal | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High | No *** |

* The authors claim the feature can be implemented within the middleware architecture; ** Without displaying ontologies or semantic annotations; *** Use cases are presented.

Additionally, Table 13 shows the main advantages and disadvantages that have been found in the previously surveyed middleware architectures for Smart Grids.

Table 13.

Main advantages and disadvantages of middleware architectures for Smart Grids

| Middleware arch. | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| GridStat | Flexible architecture for events and data collection. Publish-subscribe model suitable for the challenges of the project. QoS is provided. Tested in actual devices. | CORBA usage and its suitable alternatives may be too computationally demanding for low capability devices and smart meters. |

| Service-oriented middleware for Smart Grid | Service Oriented Architecture makes it service centric instead of device centric. QoS and QoE are provided. Tested by the involved researchers. | No context-awareness for devices or services. Used deployment standards may be too demanding for low capability devices |

| OHNet | Conceived for interconnecting home and Smart Grid devices. Can interact with different protocols. APIs are used for the application layer. | Interconnection with low capability devices is not mentioned. Bound to a very specific domain. |

| MDI | Architecture tested by developers. | Weak focus on Smart Grid. Middleware presented only as a part of a wider architecture. Middleware as just a data integration layer. |

| DPWS + IEC 61850 | Service Oriented Architecture makes it service centric instead of device centric. Technologies used are widely accepted and adopted. Slim semantic features are present. | DPWS client-server model does not completely match requirements of Smart Grids. DPWS may be too heavy for low capability devices. |

| IAP-INMS | Event based, real time features. Interoperability solutions (ESB) widely used and accepted. Architecture tested by developers. Slim semantic features are present. | Semantically annotated services or ontologies are not mentioned. Low capability devices are not thoroughly considered. |

| CoSGrid | Lightweight CORBA has been used for the middleware architecture. Security can be provided at higher levels. | Middleware presented only as a thin part of a wider architecture. No test data. |

| Self-organizing Smart Grid services | Self-organizing characteristics. Semantic features are considered | Middleware presented only as a thin part of a wider architecture. No test data. |

| Secure decentralized data-centric | Self-healing and self-configurability capabilities can be implemented. Security services are used | Not many specifications about middleware implementation. |

| Signal | Distributed nature of the service. Quality of Service is provided. | Web services may demand too many resources. Devices used are not so low-capable. |

Given the analysis presented, there are several challenges that have been detected in the different middleware architectures that have been presented. The most relevant of them are:

4.1. Middleware as an Afterthought Rather than a Defined Component

Unlike most of the other hardware and software elements of a Smart Grid, the overall impression in many of the proposals is that middleware layer was not born in mind when the design of the different systems was being undertaken. It seems like, at first, systems were being implemented without taking the appropriate care of components integration in a majority of the cases. Once it was done so, the part where that integration was somewhat taking place was labeled as “middleware”, although not enough efforts have been made in this stage to make the integration more seamless, holistic or efficient. Also, it is significant that in most of the documentation reviewed, the middleware layer or architecture has not been given any particular name.

4.2. Low to Nonexistent Intelligence in Decision Making

A strong stress on making smart decisions based on semantic is definitely required. The tools that are common in other knowledge management areas of the Internet of Things, such as ontologies or semantic middleware, are dramatically absent here. It is a serious inconvenience, for smart decisions should be the backbone of the Smart Grid and there is a lot of potential in the ubiquity of it that gets wasted. Either existing ontologies that have proved their usefulness like SSN or SOUPA must be adapted to the Smart Grid or brand new ones must be created from scratch fully compliant with the requirements of it.

4.3. Middleware is Not Fulfilling Its Expected Functionalities

If middleware is the piece of software that is needed to abstract the complexity of lower layers and provide the higher ones with a homogeneous presentation, regardless of the technologies that may be used, then it is a long way until these tasks are fulfilled in this field. So-called middleware architectures are not hiding the elements that are required for communications and make them aware the user of this inner technology layers. Alas, not much information is offered as far as new device and/or new architectures integration is concerned. This behavior must be modified in order to have it fitting middleware architecture principles.

4.4. Interoperability Unforeseen Issues

Unlike other areas of network communications—wireless or not—or energy, where strong efforts are being made by institutions as CENELEC to standardize new applications that may involve the Smart Grid [35], middleware is a difficult area where to have an ultimate standard. This is like that because any particular system, with its particular components at the lower and higher layers, will have very different middleware needs, and the middleware solutions will be usually able to interoperate with each other under specific circumstances, instead of intending a single implementation. Research in middleware is bent not on having a universal common middleware for every imaginable solution, but on improving the existing interconnection solutions. Therefore, when several subsystems are integrated, the nature of the hardware diversity will have to be taken into account. Nevertheless, when hardware and application layers are identical or at least very similar to other systems where certain middleware and interoperability solutions were used, it is likely that the same concept will be employed for similar requirements as well.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper has presented a survey on the most prominent solutions on middleware architectures for the Smart Grid, acknowledging middleware as a necessity for energy usage improvement and infrastructure management. Middleware architectures that have been found as matching the scope of this paper have been further analyzed, presenting their main characteristics, along with the way they work and both their strong points and improvable features. Furthermore, a taxonomy on how middleware architectures for Smart Grids can be classified has been put forward as well. Although middleware architectures presented in this paper have important advantages, there are still missing features that are becoming normal in middleware architectures used for other systems (regular network computing, etc.). Regarding the survey done and the extracted data, it is considered that the best, most-fitting middleware architecture for a Smart Grid should have the following characteristics:

- It should be designed being aware of the possibility of low capability devices usage (Wireless Sensor Network motes or homebrew smart meters are likely to be used as part of the metering infrastructure of the Smart Grid).

- Added value features (Quality of Service, security mechanisms, etc.) should be provided beyond interoperability and interconnectivity, as the latter should be taken for granted in any middleware architecture.

- Semantics should be consistently and systematically applied, as this offers critical advantages in service and/or device discovery or resource availability and, so far, is either missing or not thoroughly implemented in the surveyed middleware architectures. Plus, it has to be considered that semantics have the potential to solve issues regarding interoperability and interconnectivity in a more efficient and seamless than what has been done until now. Therefore, adding semantic characteristics to middleware should become a cornerstone for future middleware developments.

- Strong service-orientation. While focus on other aspects of the system—as devices or network topology—are of major importance, facilities present in the Smart Grid are thought to provide a benefit for human beings, so chances are that they will be retrieved as services.

- Finally, the middleware architecture should be tested in actual devices, attempting to match as much as possible the environment where it is supposed to be deployed.

Acknowledgments

This survey on middleware architectures for the Smart Grid has been done as part of the work that is being undertaken for the I3RES (ICT-based Intelligent management of Integrated RES for the smart grid optimal operation) research project, a FP7 initiative (reference number: 318184) that aims to improve the inclusion of Renewable Energy Sources, along with developing a management tool of special usefulness for the distribution grid [36].

References

- FitzPatrick, G.J.; Wollman, D.A. NIST Interoperability Framework and Action Plans. In Proceedings of 2010 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 25–29 July 2010; pp. 1–4.

- Kuri, B.; Li, F. Valuing Emissions from Electricity towards a Low Carbon Economy. In Proceedings of 2005 IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2005; pp. 53–59.

- Tan, Y.K.; Huynh, T.P.; Wang, Z.Z. Smart personal sensor network control for energy saving in DC Grid powered LED lighting system. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2012, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Shu, F. Density forecasting for long-term peak electricity demand. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2010, 25, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, R. Energy management and Smart Grids. Energies 2013, 2262–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendin, A.; Berganza, I.; Arzuaga, A.; Osorio, X.; Urrutia, I.; Angueira, P. Enhanced operation of electricity distribution grids through smart metering PLC network monitoring, analysis and grid conditioning. Energies 2013, 6, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.A.; Drieberg, M.; Sebastian, P. Deployment of MICAz Mote for Wireless Sensor Network Applications. In Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Computer Applications and Industrial Electronics (ICCAIE), Penang, Malaysia, 4–7 December 2011; pp. 303–308.

- Amin, S.M.; Wollenberg, B.F. Toward a smart grid: Power delivery for the 21st century. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2005, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnouskos, S. The Cooperative Internet of Things Enabled Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Symposium on Consumer Electronics, Braunschweig, Germany, 10 June 2010; pp. 07–10.

- Li, F.X.; Qiao, W.; Sun, H.B.; Wan, H.; Wang, J.H.; Xia, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, P. Smart Transmission Grid: Vision and framework. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2010, 1, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, R.; Hussain, S.; Nordstrom, L. Engineering of Trustworthy Smart Grids Implementing Service Level Agreements. In Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Intelligent System Application to Power Systems (ISAP), Hersonissos, Greece, 25–28 September 2011; pp. 1–6.

- Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Tournier, J.C.; Peterson, W.; Li, W.P.; Wang, L. A Unified Solution for Advanced Metering Infrastructure Integration with a Distribution Management System. In Proceedings of First IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 4–6 October 2010; pp. 566–571.

- Appel, S.; Sachs, K.; Buchmann, A. Towards benchmarking of AMQP. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Conference on Distributed Event-Based Systems, Cambridge, UK, 12–15 July 2010; pp. 99–100.

- Esswein, S.; Goasguen, S.; Post, C.; Hallstrom, J.; White, D.; Eidson, G. Towards Ontology-Based Data Quality Inference in Large-Scale Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of 2012 12th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGrid), Ottawa, Canada, 13–16 May 2012; pp. 898–903.

- Ganz, F.; Barnaghi, P.; Carrez, F.; Moessner, K. Context-Aware Management for Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communication System Software and Middleware, Verona, Italy, 1–3 July 2011; pp. 1–6.

- Söldner, G.; Kapitza, R.; Meier, R. Providing Context-Aware Adaptations Based on a Semantic Model. In Distributed Applications and Interoperable Systems, Proceedings of 11th IFIP WG 6.1 International Conference, DAIS 2011, Reykjavik, Iceland, 6–9 June 2011; Felber, P., Rouvoy, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Chen, B. Application of Data Interface in Power System Dispatching Based on IEC 61970 Standard. In Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Electric Utility Deregulation and Restructuring and Power Technologies (DRPT), Weihai, China, 6–9 July 2011; pp. 1048–1051.

- Cauchon, L.; Bouffard, A.; Dolan, D.; Peloquin, M.; Michaud, C. Real-Time IEC 61970 Based System for Bulk Power System Restoration at Hydro-Québec: RECRÉ-TR. In Proceedings of IEEE 3rd International Conference on Communication Software and Networks (ICCSN), Xi’an, China, 27–29 May 2011; pp. 100–104.

- Gjermundrod, H.; Gjermundrod, H.; Bakken, D.E.; Hauser, C.H.; Bose, A. GridStat: A flexible QoS-managed data dissemination framework for the Power Grid. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2009, 24, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Service-oriented middleware for smart grid: Principle, infrastructure, and application. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2013, 51, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Oliveira, L.M. QoE-driven power scheduling in smart grid: Architecture, strategy, and methodology. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2012, 50, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Gjessing, S.; Yuen, C.; Xie, S.L.; Guizani, M. Cognitive radio based hierarchical communications infrastructure for smart grid. IEEE Netw. 2011, 25, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaballos, A.; Vallejo, A.; Selga, J.M. Heterogeneous communication architecture for the smart grid. IEEE Netw. 2011, 25, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Ryou, J.C. Cosmos: A middleware for integrated data processing over heterogeneous sensor networks. ETRI J. 2008, 30, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.J. An Object-Based Middleware for Home Network Supporting the Interoperability among Heterogeneous Devices. In Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2011; pp. 585–586.

- Sucic, S.; Bony, B.; Guise, L. Standards-Compliant Event-Driven SOA for Semantic-Enabled Smart Grid Automation: Evaluating IEC 61850 and DPWS Integration. In Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Athens, Greece, 19–21 March 2012; pp. 403–408.

- Ferrari, P.; Flammini, A.; Rinaldi, S.; Prytz, G. Mixing Real Time Ethernet traffic on the IEC 61850 Process Bus. In Proceedings of 9th IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS), Lemgo, German, 21–24 May 2012; pp. 153–156.

- Samaras, I.K.; Hassapis, G.D.; Gialelis, J.V. A modified DPWS protocol stack for 6LoWPAN-based wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2013, 9, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.P.; Oliver, J.; Gosch, D. An Intelligent Agent-Based Distributed Architecture for Smart-Grid Integrated Network Management. In Proceedings of IEEE 35th Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN), Denver, CO, USA, 10–14 October 2010; pp. 1013–1018.

- Villa, D.; Martin, C.; Villanueva, F.J.; Moya, F.; Lopez, J.C. A dynamically reconfigurable architecture for smart grids. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2011, 57, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; German, R. Self-Organizing Smart Grid Services. In Proceedings of 6th International Conference on Next Generation Mobile Applications, Services and Technologies (NGMAST), Paris, France, 12–14 September 2012; pp. 205–210.

- Kim, Y.J.; Thottan, M.; Kolesnikov, V.; Lee, W. A secure decentralized data-centric information infrastructure for smart grid. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Aravamudham, P. Middleware services for P2P computing in wireless grid networks. IEEE Internet Comput. 2004, 8, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, I.; Kesselman, C. The Globus project: A status report. Future Gener. Comp. Syst. 1999, 15, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; Daowd, M.; Hegazy, O.; Mulder, G.; Timmermans, J.-M.; Coosemans, T.; van den Bossche, P.; van Mierlo, J. Standardization work for BEV and HEV applications: critical appraisal of recent traction battery documents. Energies 2012, 5, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICT-Based Intelligent Management of Integrated RES for the Smart Grid Optimal Operation. http://cordis.europa.eu/search/index.cfm?fuseaction=proj.document&PJ_RCN=13456678 (accessed on 22 July 2013).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).