Abstract

The EU’s green transition hinges on secure access to critical raw materials; vanadium is pivotal for microalloyed steels and emerging long-duration energy storage (VRFBs). Methods: We combine a market and technology review with PESTEL and Porter-5+2 analyses, complemented by a value-chain assessment and a SWOT-to-CAME strategy for the EU. Results: Vanadium supply is highly concentrated (VTM-derived, largely in CN/RU/ZA), prices are volatile, and >85% of demand remains tied to steel; yet VRFBs could shift demand shares by 2030 if costs—dominated by electrolyte—are mitigated. EU weaknesses include lack of primary mining and refining capacity; strengths include research leadership, regulatory frameworks and circularity potential (slag/catalyst recovery, electrolyte reuse). Conclusions: A resilient EU strategy should prioritize circular supply, selective upstream partnerships, battery-grade refining hubs, and targeted instruments (strategic stocks, offtake/price-stabilization, LDES-ready regulation) to de-risk vanadium for grid storage and low-carbon infrastructure. This study also discusses supply chain concentration and price volatility, and outline circular-economy pathways and decarbonization policy levers relevant to the EU’s green energy transition.

1. Introduction

In the context of the energy transition, European and US electricity markets are undergoing significant transformations as a result of the growing deployment of renewable energy sources in their respective energy mixes. One of the changes observed, especially in the European context, is the reduction in capture prices associated with the penetration of renewable technologies, specifically photovoltaic (PV) and wind power. This trend has sparked growing interest in energy storage solutions, largely driven by the reduction in the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) of renewable technologies compared to conventional generation sources [1]. In the context of the increased integration of renewable sources into modern energy systems, there is growing evidence of greater variability in power generation and, consequently, an increasing need for the implementation of storage strategies that encompass both short-duration energy storage (SDES) and long-duration energy storage (LDES). Renewable energy sources such as solar and wind are inherently variable and non-dispatchable, leading to fluctuations in power generation that challenge grid stability and energy security. The integration of large-scale and long-duration energy storage systems can mitigate these effects by balancing supply and demand over extended periods, thereby enhancing the utilization and reliability of renewable power. Among the available technologies, redox flow batteries (RFBs) [2,3]—particularly vanadium-based systems—are attracting increasing attention as scalable and durable solutions for long-duration energy storage in renewable-dominated grids [4].

Increased research into LDES has resulted in the commercialisation of various RFB technologies. Among these, vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs) have seen notable implementation and diffusion, despite the limited availability of vanadium [5,6,7] and its high toxicity even in low concentrations [8]. This is attributed to their stability, life cycle and scalability [9,10,11].

Furthermore, growing interest in energy storage is limited by the difficulties associated with making a homogeneous comparison of costs between the different technologies available. In a large amount of research, the analysis focuses predominantly on the investment cost (CAPEX), disregarding other critical factors that significantly influence economic models, such as efficiency, depreciation over time, and the useful life of the system [12].

However, CAPEX remains a fundamental item in the LCOE of an energy storage system, which is directly related to the cost of the raw materials used in its composition [13]. In the specific case of VRFBs, the price and availability of vanadium have a significant influence on the LCOE of this technology [6].

Crucially, securing the competitive viability of VRFBs is significantly challenged by the pronounced geopolitical concentration in key segments of the value chain. This structural vulnerability stems from the fact that vanadium supply is highly concentrated, with approximately 90% of global production originating in a limited number of nations, primarily China, Russia, and South Africa (Section 3.1). This high concentration yields a market structure quantified by a Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) of around 5000, confirming an oligopolistic market structure that amplifies price volatility (Section 3.3.8). This volatility is critical, as the cost of the electrolyte can represent between 30% and 50% of the total CAPEX (Capital Expenditure) of a VRFB system (Section 3.3.4), while price variations have historically exceeded 100% at certain intervals over recent decades (Section 3.3.8). Furthermore, the leading global deployments of this technology, such as the 800 MWh system in Dalian (Section 3.3.4), are currently concentrated in specific regions, notably China, which reinforces the global asymmetry in technological and industrial maturation.

Furthermore, European regulation provides a crucial frame of reference: the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), the European Green Deal and related industrial resilience policies place secure access to raw materials at the heart of the continent’s energy and technological future. The purpose of these policies is not limited to diversifying supplies and attracting investment, but also focuses on speeding up permitting processes, incentivising recycling and promoting international partnerships [14,15].

Despite the numerous reports addressing the EU electricity market and renewable integration, there is a limited body of academic research that systematically links the strategic security of vanadium supply with the Union’s decarbonisation targets and industrial autonomy. This research aims to fill that gap by adopting a comprehensive strategic perspective that connects material criticality, industrial competitiveness, and policy design, thus providing a coherent framework to evaluate vanadium’s role in Europe’s transition toward a resilient and sustainable energy system.

The purpose of this study is to provide a systematic analysis of the vanadium market from the strategic perspective of the European Union (EU). To this end, it will offer an overview of the political, economic, socio-cultural, ecological and legal environment, as well as an internal analysis of the EU’s strengths and weaknesses in this environment. In this regard, we will seek to provide sound recommendations that contribute to strengthening European autonomy in the energy storage value chain.

2. Methodology

Key analytical tools were selected to assess the prospects for the vanadium market and the strategic sustainability of the EU in the context of the green ecological transition. The methodological design combines a comprehensive assessment of both the external competitive environment and the internal capabilities of the European Union, employing well-established instruments from the field of strategic management and industrial policy analysis.

2.1. Data Collection

The empirical foundation of the study rests on a triangulation of diverse data sources. Primary information was obtained from peer-reviewed scientific literature indexed in Scopus and Web of Science focused mainly on publications from 2020 to 2025, supplemented by earlier studies providing historical or baseline information, ensuring methodological rigor and conceptual validity. Complementary secondary and grey literature were also incorporated, including industrial and market reports from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) [16,17], IEA [18,19,20,21], and Wood Mackenzie [22], as well as official European policy documents such as the Critical Raw Materials Act [23], the Net-Zero Industry Act and communications related to the European Green Deal. This multi-source integration enables a comprehensive and up-to-date characterization of the vanadium sector and its strategic role in the EU energy transition.

To achieve the goal of providing a systematic strategic analysis of the vanadium market from the European Union’s perspective, the methodological design was structured into five integrated analytical phases (Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4, Section 2.5 and Section 2.6). This approach systematically moves from assessing the macro-environmental factors (PESTEL) and competitive industrial structure (Porter’s 5+2 Forces) to evaluating the EU’s internal capabilities and structural weaknesses (Value Chain Analysis), culminating in the development of actionable policy recommendations through the integrated SWOT-CAME framework.

2.2. Contextual Analysis

A baseline contextualization was developed encompassing the geology, metallurgy, and industrial applications of vanadium. This stage established the conceptual and geographical boundaries of the case study and defined the key structural parameters that determine vanadium’s role as a critical raw material within the EU’s decarbonization and industrial resilience framework.

Scientifically, this phase acts as the essential empirical bridge, defining the critical structural parameters—such as the geographic concentration of supply, metallurgical complexity, and the market application split—that serve as the fundamental inputs for the formal PESTEL and Porter’s 5+2 Forces analyses.

2.3. PESTEL Analysis

A comprehensive comparative PESTEL analysis—covering Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal dimensions—was conducted to assess the macro-environmental factors shaping the European vanadium value chain. Each dimension was constructed from the previously identified data sources, systematically identifying drivers, constraints, and interdependencies that condition the EU’s strategic position in vanadium supply and innovation.

2.4. Porter’s Five + Two Forces

In a subsequent stage, Porter’s Five Forces model [24] was applied and extended to a 5+2 framework to include the influence of complementors and stakeholders such as institutional actors, NGOs focused on environmental governance, and technological alliances [25,26]. This adaptation is particularly relevant for critical raw materials, where market dynamics are strongly shaped by regulatory, environmental, and geopolitical pressures. The analysis focused on entry barriers, supplier concentration, substitutability, and bargaining power among industrial and institutional participants, providing a detailed understanding of the competitive structure of the vanadium sector.

2.5. Value Chain Analysis

For the internal dimension, Porter’s Value Chain [27] framework was adapted to the specific context of extractive industries and energy storage technologies. This adaptation allowed the mapping of European strengths and weaknesses across all stages of the vanadium lifecycle—from primary mining and refining to recycling, R&D, and industrial integration. Both tangible resources (such as deposits, processing capacity, and infrastructure) and intangible resources (including regulatory frameworks, skilled human capital, and technological know-how in metallurgy and flow batteries) were evaluated to identify systemic bottlenecks and strategic opportunities.

2.6. SWOT-CAME Integration

The external and internal analyses were subsequently integrated through a combined SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) matrix, summarizing the structural risks and competitive advantages identified in the previous stages. Building on this, the CAME (Correct, Adapt, Maintain, Exploit) framework was applied to transform diagnostic insights into actionable strategies. This stage allowed the formulation of evidence-based recommendations aligned with industrial planning, critical materials policy, and the EU’s long-term resilience objectives.

This sequential and integrative methodological design ensures transparency, consistency, and replicability, providing a rigorous analytical foundation for assessing the geopolitical, industrial, and environmental dimensions of vanadium within the European critical materials framework.

In summary, this methodological framework establishes a coherent pathway linking macro- and micro-level analytical instruments under a unified strategic lens. By combining contextual, structural, and strategic perspectives, the approach allows not only the identification of current vulnerabilities in the vanadium value chain, but also the projection of potential scenarios for its sustainable development within the European Union. The integration of well-established analytical tools—PESTEL, Porter’s extended model, Value Chain mapping, and SWOT–CAME synthesis—ensures that the resulting insights are both theoretically grounded and practically oriented. This multidimensional design ultimately provides a replicable and policy-relevant framework to support evidence-based decision-making in the governance of critical raw materials, reinforcing the analytical credibility and policy utility of the present research.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Main Vanadium Deposits

Vanadium is a chemical element found in the Earth’s crust in relatively high concentrations. It is found in a wide variety of materials, and its average concentration worldwide is 97 mg/kg [28]. However, the concentration of vanadium can vary significantly depending on the type of soil, as it is closely linked to its oxidation state and the pH of the medium [29].

Vanadium, a chemical element with atomic number 23, is commonly found in soils and sediments as a trace element, often replacing iron (Fe) or aluminium (Al) in primary or secondary minerals in octahedral positions in crystal structures [30]. However, due to its correlation with iron, it is more commonly found in mafic rocks than in siliceous rocks [23,31,32,33]. In line with the usual tendency of minerals to occur in nature in association with other minerals and, in exceptional circumstances, individually, most deposits are polymetallic [29,34,35,36]. Broadly speaking, four categories of vanadium deposits have been identified: vanadium titanomagnetite (VTM) deposits, tabular sandstone-hosted and surface uranium deposits, vanadium deposits associated with crude oil, coal and salts, and vanadate deposits [32,37,38,39]. In contrast to the above, some less prevalent deposits have been identified associated with graphite or in laterites, bauxites, iron ores, and phosphate ores [39].

Approximately 90% of global vanadium is extracted from VTM deposits located in Russia, South Africa, China, Finland, Canada, and Australia [36,40,41]. VTM deposits are characterised by accumulations of magnetite and ilmenite in magmatic rocks, as reported in scientific literature [37]. The minerals most commonly found in VTM deposits are magnetite (Fe3O4), ilmenite (FeTiO3), rutile, and small amounts of hematite (Fe2O3) [34,42], resulting in a close Ti-V association [39].

The origin of VTM deposits has not been conclusively elucidated in the scientific field. However, it has been observed that these deposits are commonly associated with stratified igneous intrusions in cratonic regions [38,43].

With regard to uranium–vanadium deposits, the so-called tabular sandstone-hosted deposits (Table 1) are uranium impregnations that form irregular mineralised bodies with a lenticular shape and parallel, in elevation, to the reducing sediments in which they are embedded [44,45]. These elements originate as a result of water flowing through the sediments until it reaches a sufficiently reducing formation that allows both uranium and vanadium to precipitate [46,47].

Surface uranium deposits are characterised as ‘young’ because they are predominantly located in tertiary geological formations adjacent to the topographic surface [48]. The deposits of interest, which are the subject of this study, exhibit uranium mineralisation predominantly in the form of hexavalent minerals of this element. Specifically, the presence of carnotite and tujamunite is observed [45,49,50].

Table 1.

Geometallurgical characteristics of uranium deposits in sandstones [49,50].

Table 1.

Geometallurgical characteristics of uranium deposits in sandstones [49,50].

| Type of Deposit | Mineralogy | Bargain Rocks | Notable Deposits | Metallurgical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone-hosted | Pitchblende, Uraninite, Coffinite, Autunite, Fosrfouranilite. | Quartz with sulphides, carbonaceous material and ferro-magnesium mafic minerals. | Sominair, Niger; Letlhakane, Botswana; Rystkuil, South Africa; Mkuju River, Tanzania; Inkai, Kazakhstan; Khiagda, Russia | High presence of clayey materials. High-grade zones in the shape of an arrow. High carbonate content. Presence of organic matter and sulphides. Low grades. |

| Surficial | Carnotite, Tujamunite, and other complex uranyl minerals. | Carbonate rocks, clays, quartz, and gypsum. | Trekkopje, Namibia; Langer Heinrich, Namibia; Yeelirrie, Australia | Low-grade ores. Soft materials, possible mechanical stripping. High gypsum content. High chloride content. Alkaline leaching is commonly used. |

In summary, it can be stated that uranium and vanadium are transported to their final deposition location by dissolving in the region’s groundwater. This water moves laterally and vertically from the oldest geological formations to the most recent ones, which are associated with tertiary or quaternary sedimentary environments close to the surface. In the latter environment, carnotite is deposited as a result of the accumulation of uranium, potassium and vanadium in the necessary quantities and oxidation states [45,48].

In line with the above, vanadium reserves extracted as a by-product in uranium deposits are highly limited compared to vanadium titanomagnetite deposits [38]. However, as a result of uranium extraction as a primary mineral, they become a source of vanadium that, in the absence of uranium mineralisation, would not be exploited for economic reasons.

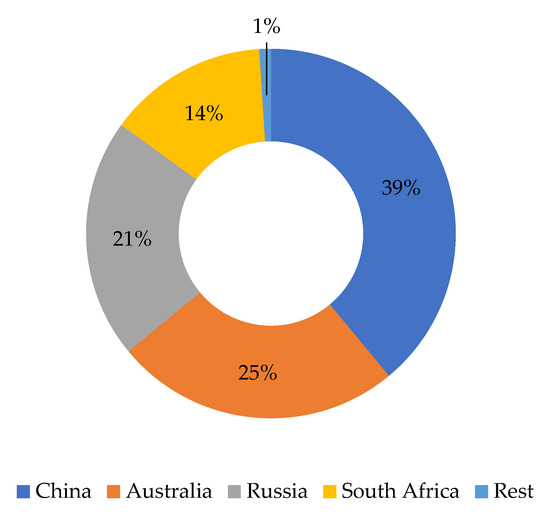

Analysis of the global reserve base (Figure 1) reveals an extreme geographical concentration of vanadium supply, as nearly all identified reserves are located within just four nations. This high concentration, with two countries alone holding well over half of the global total, establishes the critical supply risk addressed later in this study.

Figure 1.

Distribution of vanadium reserves by country according to reference [51].

In the specific case of surface-type uranium–vanadium deposits, despite the fact that there is still a significant concentration of deposits in Namibia and Australia, it is evident that, as a result of mining exploration and prospecting activities in the United States, specifically in the state of Texas, and in Argentina, at least two emerging uranium-bearing regions have been identified [45,48,52]. Secondly, sandstone-hosted deposits have been identified around the world, on different continents. In certain cases, the vanadium grade justifies their metallurgical processing [53].

Crucially, this concentration means that 50% of the world’s reserves are held by countries whose reliability in terms of supply is questionable. Consequently, both the European Union and Australia and the United States have considered vanadium to be a critical raw material (Table 2). That said, and in line with the above, it has been observed that, along with uncertain security of supply, the applications of vanadium have increased due to the energy transition. Therefore, it has been determined that there is likely to be an increase in demand [38,39].

Table 2.

CRM list by year.

3.1.1. Evolving EU Strategic Priorities Reflected in the CRM List

The temporal evolution of the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials (CRM) list (Table 2) provides a clear time-series analysis of the evolving strategic priorities, shifting from a focus purely on supply risk mitigation towards securing entire value chains essential for the Green and Digital Transition.

The inclusion of vanadium in the 2017 list (which continues to be relevant due to its high Supply Risk—SR of 2.3 in the 2023 assessment [62]—driven by concentrated global production in China, Russia, and South Africa) confirmed its vital role in future High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) steel and emerging Long-Duration Energy Storage (LDES) applications.

However, the most recent update demonstrates a major inflection point in EU policy. For the 2023 list, materials such as Nickel and Copper were included not because they met the traditional CRM thresholds, but because they were designated as Strategic Raw Materials (SRMs). As defined under the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), SRMs are essential for technologies supporting the twin green and digital transition and defense objectives. This highlights a strategic shift from simply identifying resource scarcity to actively securing the infrastructural and technological materials critical for achieving industrial resilience and autonomy.

This trend—prioritizing materials like Copper and Nickel due to their strategic end-use in electrification infrastructure—validates the EU strategy’s necessity to move beyond mere diversification (P4—Porter” and “Af1, E3, M2) and establish deep technological and financial partnerships, as defined by the CAME strategy (Af1, E3, M2—SWOT & CAME).

3.1.2. Economic Feasibility of Uranium–Vanadium Deposits: The Ivana Case Study

To illustrate the economic rationale for uranium–vanadium co-production, the Ivana deposit (Río Negro, Argentina) has been selected as a representative example. This deposit, explored by Blue Sky Uranium Corp in 2018 [63], is hosted in sandstone-surficial formations and presents a combined uranium–vanadium mineralization (mainly carnotite and tyuyamunite) with an average grade of 311 ppm U3O8 and 107 ppm V2O5, corresponding to a U/V mass ratio of approximately 2:1.

Using unit operating costs and recovery factors reported by Blue Sky Uranium Corp. (2018) [63]—mining cost ≈ 2.26 USD/t, ore processing cost ≈ 8.26 USD/t, and metallurgical recovery of 85% for uranium and 50% for vanadium and assuming current average market prices between 50 and 100 USD/lb U3O8 and 13 USD/kg V2O5, the results indicate that the cut-off grade for uranium lies between 56–112 ppm U3O8, consistent with values observed in low-grade sandstone-hosted deposits [64,65].

Conversely, the stand-alone cut-off grade for vanadium is estimated to exceed 1600 ppm V2O5, assuming the same cost structure and recovery rates [64]. Given that the actual vanadium grade in Ivana is nearly an order of magnitude lower (≈107 ppm), it is clear that vanadium extraction alone would not be economically feasible [63]. Therefore, the economic justification of uranium–vanadium deposits depends primarily on uranium revenues, with vanadium acting as a secondary product that enhances the project’s financial robustness rather than as a main driver of profitability.

3.2. Vanadium Processing and Metallurgy

The technical and economic viability of a mining operation is often conditioned by various factors, among which the mining method and extractive metallurgy stand out. In this study, a significant correlation has been found between the type of mineral present in the deposit being mined and the element in question. In the field of mining engineering, it is important to consider various geological and geographical factors when determining the mining method to be implemented or the most appropriate extraction technique for a mining operation. These factors include mineralogy, geographical location and the nature of the host rock. The case of vanadium is no exception.

Given the diversity of vanadium deposits, the extractive metallurgy techniques to be implemented will be selected based on the specific characteristics of each operation. In the case of titanomagnetite deposits, two main processing methods are identified, depending on the ore to which the metallurgical processes are applied. These methods are described in references [66,67].

Initially, vanadium was extracted directly. However, this procedure required higher purity ores and generated problems related to the management of tailings and waste [36,68]. In a second phase of research, advances in the field of extractive metallurgy led to the use of vanadium slag, a by-product of the steelmaking process, as the main material for vanadium extraction [36].

In general terms, two predominant methods for extracting vanadium have been identified. The first involves precipitating a vanadium salt by leaching a roasted ore with salt. The second method is based on leaching salt-roasted slag, obtained after smelting the ore to produce pig iron containing vanadium. This is followed by oxygen blowing in a converter, which results in the generation of vanadium-rich slag [68,69].

In contrast, alternative methods for obtaining vanadium are being explored. According to the most recent data (2021), 13.03% of the raw materials for vanadium products produced worldwide are obtained directly from vanadium-bearing titanomagnetite, while 76.20% come from vanadium slag produced from vanadium-bearing titanomagnetite [51].

Regarding U-V deposits, the procedures currently used to extract uranium from their ores can be classified into two clearly distinct categories: acid leaching and basic leaching. This distinction is determined by the inherent characteristics of the specific gangue in question [70]. As evidenced in the analysis in Table 1, minerals from various types of deposits tend to contain alkali elements in concentrations that, when exceeding 5–8% of the total, can make acid consumption prohibitive, forcing the use of basic attack strategies [71].

In the context of a uranium–vanadium deposit, where the recovery of both elements can be of great economic interest, in addition to considerations relating to gangue, the most relevant characteristic of basic treatment is selectivity. Sodium carbonate attack exhibits significantly higher selectivity compared to acid attack methods using sulphuric acid or hydrochloric acid. In certain circumstances, sodium carbonate shows greater selectivity, dissolving only silica and, occasionally, vanadium, rather than dissolving a wider variety of species in the leaching alkali liquor [72,73]. In the field of strategic metal extraction, the sodium salt roasting process for obtaining vanadium from U-V deposits exhibits a remarkable similarity to those used in titanomagnetites. However, given the need to extract two different concentrates, vanadium and uranium are separated in the liquid phase, resulting in recoveries of 70–80% for vanadium and 90–95% for uranium [34].

3.3. Vanadium Applications and Market Trends for Green Energy

3.3.1. Scope and Framing: Energy-Transition-Relevant Applications

Vanadium, chemical element number 23 in the periodic table of elements, is a versatile element with a wide range of industrial applications. However, not all technologies are directly linked to the energy transition or emissions reduction, as its most common applications are linked to the steel industry. However, it is also used in the chemical industry [74]. To properly contextualise this section, it is imperative to distinguish between traditional uses and strategic uses in the context of decarbonisation.

Currently, most of the global demand for vanadium is concentrated in the steel industry, where it is used in the form of ferrovanadium for the production of high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels [7]. Although this is a conventional sector, its relationship with the energy transition should not be underestimated. Vanadium steels reduce the weight and amount of material required in critical structures such as wind towers, electric transport infrastructure and sustainable urban construction. This leads to indirect savings in carbon dioxide emissions [75].

As noted in previous research, storage using lithium-ion batteries (LIB) has proven to be the most relevant emerging application in the context of the energy transition. However, high-temperature lithium-ion batteries (VRFBs) have been identified as having greater potential to improve the efficiency and sustainability of energy storage in the energy sector. These technologies are characterised by their safety, durability and storage capacity on time scales ranging from hours to days [76,77]. Consequently, they are an appropriate complement to intermittent renewable energies, such as wind and solar power. This study addresses the issue of renewable energy penetration in the market, a phenomenon which, although still in its infancy, is postulated as one of the main vectors of resilience for electrical systems in scenarios of high renewable penetration.

Other applications, such as industrial catalysts or titanium and vanadium alloys, have a more tangential relationship with the transition. While they contribute to improving the efficiency of chemical processes, reducing pollutant emissions and lightening materials, they do not have as marked a direct impact as microalloyed steel and hydrogen fuel cells (FVCF).

Consequently, Section 3.3 will focus on applications in which vanadium plays an essential role in the decarbonisation process, such as (i) microalloyed steels, which reduce the material footprint, and (ii) VRFBs, which act as a key vector in stationary storage. The rest of the applications will be briefly reviewed in order to provide a holistic view, albeit of a secondary nature. In this sense, the necessary framework is established to assess both current trends and future prospects in the energy transition.

3.3.2. Current Demand Landscape: Application Split and Material Intensity

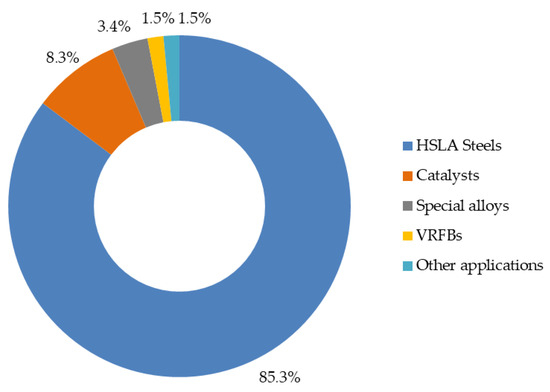

The vanadium market shows significant concentration in certain sectors, with a notable predominance of the steel industry. The current vanadium market shows a dominant and structural dependence on the steel sector, which accounts for between 85% and 90% of global consumption (Figure 2). This imbalance is the primary source of price volatility [78]. This study addresses the use of these steels in various industrial applications. Firstly, they are used in reinforcing bars, structural profiles and oil pipelines. Secondly, there is a growing trend towards their use in infrastructure linked to the energy transition, such as wind towers, power lines and photovoltaic structures. The standard alloy ratio is in the range of 0.03–0.1% by weight of V, suggesting that minimal fluctuations in global steel production could cause significant variations in vanadium demand [79].

Figure 2.

Global vanadium consumption by application. The proportions have been estimated based on the value ranges reported in the literature [78] and adjusted to represent a total of 100%.

The second largest consumption block corresponds to catalysts, which represent between 7% and 10% of the market (see Figure 2) [78]. In the field of scientific research, certain catalysts have been identified that have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in various industrial applications. These include vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) catalysts, used in the production of sulphuric acid, and catalysts used in selective catalytic reduction systems for the removal of nitrogen oxides (NOx) in power plants and industrial processes. Although these uses are more traditional, they contribute indirectly to the energy transition by improving process efficiency and reducing pollutant emissions.

Special alloys, particularly those composed of titanium and vanadium, account for approximately 3–4% of total consumption, as shown in Figure 2 [78]. These applications are particularly important in the aeronautical, biomedical and high-tech sectors, where the strength and lightness of materials are critical factors. Although their relationship with the energy transition is more peripheral, their potential contribution to weight reduction in transport and aviation components, which in turn translates into lower fuel consumption, should not be overlooked [75].

Although long-duration energy storage technologies, primarily VRFBs, currently account for less than 2% of consumption (Figure 2), this segment represents the most significant opportunity for demand diversification and future growth [78].

The remaining applications (pigments, ceramics and minor chemical products) make a marginal contribution to consumption, ranging from around 1–2%, with no prospect of substantial growth in the context of the energy transition [78].

As previous research has shown [78], current demand for vanadium is clearly linked to the steel sector, although there are signs of diversification towards the energy and technology sectors. The market thus faces a twofold complexity: profound structural interdependence with the volatile steel sector, contrasted with the rapid emergence of VRFB demand, which is projected to reconfigure the global market balance in the coming years.

3.3.3. Microalloyed Steels for Low-Carbon Infrastructure

Currently, the most widespread use of vanadium is as a microalloying element in HSLA steels. As previously mentioned, the incorporation of this element, although modest, with a variation between 0.03% and 0.10% by weight [79], has a significant impact on the mechanical properties of steel. Vanadium promotes the formation of carbides, nitrides and carbonitrides that refine grain size and increase strength and toughness without sacrificing ductility [79]. In line with recent findings, recent research on steels with high vanadium content, such as Vanadis 8 produced by Metalurgia de Polvos, has revealed that the presence of MC-type carbides (VC, >2800 HV), in conjunction with heat treatment and ion nitriding, is essential for controlling grain growth and, simultaneously, enhancing wear and corrosion resistance in aggressive environments, which translates into an increase in industrial applications [80].

These characteristics are particularly relevant in the context of the energy transition, where a high volume of steel is required for the development of low-carbon energy infrastructures. In the context of mechanical engineering and structural construction, the use of microalloyed steels in wind towers represents a significant innovation. This material allows for a reduction in section thickness without compromising the structural safety of the structure. As a result, there is a reduction in the total weight of the tower, which in turn reduces the costs associated with transport, assembly and foundations. In the field of electricity transmission and distribution networks, the use of vanadium steels has become common practice in the construction of poles, towers and reinforcements, thus contributing to the expansion of the network necessary for the integration of renewable energies. In the field of construction, the implementation of reinforcement bars with a high elastic limit allows for the optimisation of designs, which translates into a reduction in the carbon footprint associated with the material.

The impact this has is not trivial: it has been estimated that replacing conventional steels with HSLA containing vanadium can reduce steel consumption per functional unit by up to 30%, with a consequent reduction in CO2 emissions [81]. Considering that the steel industry is responsible for approximately 7–9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, these reductions take on strategic importance for international climate goals [18].

3.3.4. Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries and Long-Duration Energy Storage

VRFBs are the implementation of vanadium that is closest to the energy transition. This study addresses the distinctive principle underlying the use of vanadium in four oxidation states—V2+/V3+ in the negative electrolyte and V4+/V5+ in the positive—with the aim of avoiding cross-contamination of species, a phenomenon that can occur when redox pairs belong to different elements [76]. The chemical symmetry in question confers long-term stability and mitigates the irreversible degradation associated with cycles, positioning VRFBs as natural candidates for long-duration stationary storage in combination with wind and photovoltaic energy [82,83].

However, despite this intrinsic advantage, commercial systems still face the major challenge of vanadium ion crossover through the ion-exchange membrane separating the two half-cells. The commonly used Nafion® membrane exhibits limited selectivity between protons and multivalent vanadium ions, allowing gradual interpenetration of species that leads to capacity decay and efficiency loss during cycling. Ongoing research focuses on developing advanced membranes and composite separators with improved ion selectivity and lower permeability to vanadium ions [84,85].

In the field of architecture, power and energy are scaled independently. Specifically, power depends on the size of the electrochemical stacks, while energy depends on the volume of electrolyte stored [6]. This feature, which is not present in technologies such as lithium-ion, enables the economic estimation of systems with a duration of up to 24 h by incorporating electrolyte tanks, thus avoiding the oversizing of the associated power generation unit. In the field of network services, the observed independence has been shown to have a significant impact on reducing incremental costs per additional hour compared to chemical services, where power and energy are coupled [77,82].

Another outstanding aspect that deserves special mention is safety. In this regard, the electrolyte in VRFBs is aqueous in nature and does not have a propensity for combustion, which mitigates the risk of thermal runaway that occurs in certain lithium-ion architectures [86,87]. This fact, in conjunction with the ability to tolerate deep discharges—close to 100% without accelerated degradation— and their long service life—more than 10,000 cycles in stationary applications—leads to an optimisation of the levelized cost of storage (LCOS) when the target duration is longer and the service profile is more intensive [77,82].

Costs and intensity of vanadium use.

The main drawback associated with VRFBs is the high cost of the electrolyte, which is closely linked to the value of vanadium. As can be seen from the research carried out, the scientific literature specialising in the field of solar energy shows that the electrolyte can represent between 30% and 50% of a system’s CAPEX. It has also been determined that the typical intensity of vanadium use is in the range of 3 to 6 kg per kWh of capacity. In practical terms, storing 1 MWh of energy can require between 4.5 and 5.5 tonnes of V2O5 [88]. This phenomenon means that fluctuations in the sale price of vanadium are transferred almost directly to the investment cost of the system [89].

Although electrolyte costs represent a major share of the capital expenditure, other components included in the balance of system (BOS), such as tanks, membranes, pumps, and power conditioning equipment, also exert a significant influence on overall economics. Recent studies suggest that improvements in membrane selectivity, stack efficiency and modular plant design could significantly reduce BOS costs in the coming years [77,90].

Moreover, while vanadium-based systems are often perceived as expensive, other aqueous flow batteries, such as those based on iron or zinc chemistry, also face cost and efficiency limitations. Iron-based flow batteries generally benefit from lower electrolyte costs but exhibit lower energy density and reduced long-term stability. Conversely, VRFBs provide outstanding durability and nearly complete recyclability of the active materials, which offsets part of their higher upfront cost and supports their competitiveness in long-duration energy storage applications [91].

This dependency has promoted particular business models, such as electrolyte leasing, in which a third party finances the vanadium and the user pays for the energy service, minimising the barrier to entry and facilitating circularity (at the end of the contract, the vanadium is recovered and can be reused in another system). A recent study published by the World Bank [92] examines this approach in detail and presents it as a key element in driving commercial adoption while reducing the risks associated with price fluctuations.

Comparison with other storage technologies.

In short ranges (1–4 h), lithium-ion batteries—especially lithium iron phosphate or LFP batteries—maintain a cost advantage thanks to economies of scale and highly developed supply chains. Various analyses [93,94] place the installed cost of Li-ion below the cost of flow technologies, at least in this time range. However, when the required duration increases (ranges between 8 and 12 h), the incremental cost of VRFBs grows more slowly, since adding energy is essentially adding electrolyte and tank.

Recent technology cost assessments by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory [94] project the overnight capital cost for a complete 4 h lithium-ion battery system to average USD 326/kWh by 2030 (in 2022 USD). In comparison, the US Department of Energy [93] show reference projects for a 100 MW/10 h VRFB with total costs estimated at around USD 365–385/kWh for 2030. This price gap reinforces the strategic importance of technology differentiation: the VRFB niche relies on its competitive advantage for Long-Duration Energy Storage—specifically, for durations exceeding 8 h—where its decoupled power and energy capacity and superior cycle life (over 10,000 cycles) offset the higher upfront capital cost.

In the global market context, confirmed by the International Energy Agency [19], battery storage deployment has experienced an unprecedented surge, doubling year-on-year in 2023, with over 40 GW of new capacity added globally. This explosive growth, primarily driven by LFP chemistries for Short-Duration Energy Storage, which accounted for approximately 80% of new capacity additions in 2023, defines the competitive landscape for all battery technologies.

IEA analysis projects that to meet the COP28 (Conference of the Parties) goals—specifically tripling global renewable energy capacity—total energy storage must increase sixfold, with battery storage capacity rising 14-fold to 1200 GW by 2030 in the Net Zero Emissions Scenario. Crucially, the IEA projects that total utility-scale lithium-ion battery system costs will decline by an additional 40% by 2030 in the Stated Policies Scenario, reaching USD 175/kWh.

This intense cost pressure necessitates a clarification of forecast parameters. While the IEA stresses the definitive need for Long-Duration Energy Storage solutions to integrate higher shares of renewables without oversizing the grid, VRFBs must prove their superior Levelized Cost of Storage for durations exceeding eight hours against this backdrop of rapidly decreasing Li-ion system costs. Looking ahead to 2030, the USGS collects market estimates according to which VRFBs would absorb around 17% of vanadium consumption [16]. Such a rapid increase in the share of VRFBs will place new, intensified demands on the vanadium supply chain.

To quantify the market potential and associated risks, particularly in light of projections that VRFBs could absorb around 17% of global vanadium consumption by 2030, a clear set of quantitative assumptions is presented Table 3 which synthesizes the fundamental parameters driving the competitive scenarios for VRFB adoption, focusing on cost targets, scaling advantages, and critical mitigation strategies.

Table 3.

Key Quantitative Assumptions for VRFB Demand Scenarios.

Deployment and flagship projects.

Although the installed base of VRFBs is still modest compared to lithium-ion, in recent years a series of projects have been implemented that demonstrate the technological maturity at grid scale. In Dalian (China), the first phase of a 200 MW/800 MWh project designed for peak management and renewable integration was connected to the grid in 2022.

Outside China, Australia, the US and Europe have deployed smaller-scale projects, but with diverse use cases: microgrids and islands, photovoltaic integration with day-night storage, and deferral of transmission investments when demand grows faster than grid capacity. The IEA reports accelerated growth at the grid scale and anticipates greater technological diversity as regulators recognise the value of long-duration storage [20].

Use cases: How VRFBs fit into the electricity system.

VRFBs perform optimally in the following cases:

- Integration of intermittent renewables, allowing generation to be shifted from hours of excess to hours of deficit without severe degradation penalties [83].

- Postponement of grid reinforcements when located downstream of bottlenecks.

- VRFBs can flatten local peaks and delay reinforcement investments and grid improvements. They also have the advantage of being non-flammable and independent of power and energy, which allows for the design of customised systems [77].

- Microgrids and islands, offering operational safety, intensive cycles and the possibility of reusing the electrolyte at the end of its life [82].

Circularity: Leasing and recycling.

Throughout this paper, it has been mentioned on several occasions that a strategic advantage of VRFBs is that their electrolyte is recoverable. Unlike lithium-ion technology, where recovering lithium, nickel or cobalt with positive net economic returns remains a challenge, in VRFBs it is feasible to recirculate vanadium using relatively conventional chemical operations, regenerating the oxidation state or precipitating it for purification. Circular models such as leasing + recovery reduce initial CAPEX and vanadium price risk by partially decoupling the competitiveness of the technology from the volatility of the primary metal market [92].

Technological sensitivities and cost levers.

Although the electrolyte dominates CAPEX, other factors influence competitiveness:

- Electrodes and membranes: improvements in pressure drop, kinetics and selectivity reduce losses and plant balance costs. Advances in materials and thermal-hydraulic control increase efficiency and reduce OPEX [95].

- Vanadium concentration: increasing molarity increases energy density but requires phase stabilisation to prevent precipitation [95].

- Standardisation: scaling up production and standardising designs reduces the specific cost per kW [82].

In the medium term, gradual improvements are expected which, combined with electrolyte leasing and increased volume, will place VRFBs in competitive cost ranges for storage exceeding 8 h [1]. Some projections for 2030 place total costs (CAPEX) at around $365–385/kWh [94].

3.3.5. Circularity and Recycling in Energy Applications

The concept of circularity in the use of critical raw materials has become a priority for the energy transition. In the case of vanadium, this principle is particularly relevant not only because of the high geographical concentration of its primary production, but also because the metal itself has chemical properties that facilitate its recovery and reuse. In a scenario of recent demand—microalloyed steels today and redox flow batteries in the future—taking advantage of and scaling up vanadium recycling and revaluation routes is essential to ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of the value chain.

The economic feasibility of circularity, however, must be rigorously quantified. Despite vanadium’s intrinsic recoverability, its current contribution to meeting EU demand is marginal, highlighting an operational bottleneck. According to the 2023 EU criticality assessment, the End-of-life Recycling Input Rate (EOL-RIR) for vanadium stands at only 6%. This low figure provides quantitative evidence of the significant gap between theoretical recycling potential (O2) and industrial capacity at scale (D2). Scaling this rate is imperative to mitigate the high Supply Risk (SR = 2.3) and production concentration associated with primary supply, aligning with the strategic objective of the Raw Materials Initiative to reduce dependence on primary materials through recycling. Consequently, targeted analysis of material flows and feasibility of typical projects is required. Vanadium recovery pathways primarily concern VRFB electrolyte, spent catalysts, and steel slag [66].

As discussed in Section 3.3.4, the electrolyte is the most critical cost component in VFBRs, accounting for up to 50% of total CAPEX [89]. However, from a circularity perspective, this apparent weakness becomes an advantage, as the electrolyte in this type of battery remains chemically stable throughout its useful life [96]. In other words, after 15–20 years of operation, the electrolyte retains virtually all of the initial vanadium.

At the end of its useful life, chemical conditioning is carried out, which consists of adjusting the vanadium concentration, removing impurities and restoring operating conditions. In practice, this is equivalent to having a permanent stock of technospheric vanadium that can circulate indefinitely between successive generations of VRFBs [82].

Compared to lithium-ion batteries, where recycling processes are costly and have limited yields [97], the circularity inherent in VRFBs constitutes a differential competitive advantage.

A second relevant circularity flow is vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) catalysts. Over time, these catalysts lose their effectiveness but retain their valuable vanadium content. There are currently established processes for the recovery of spent catalysts using conventional metallurgical techniques such as leaching, selective precipitation and calcination [98,99]. The treatment of thousands of tonnes of catalysts per year can generate a stable flow of secondary vanadium that would help reduce dependence on primary mining.

Unlike VRFB electrolyte, catalysts represent a more dispersed flow with greater logistical variability, as they are generated in multiple chemical and energy plants. Even so, their vanadium content is sufficiently high—between 3 and 12% by weight, compared to less than 1% in primary ores [99]—and there are established industrial processes with yields above 80% [100]. Furthermore, as it is classified as hazardous waste, its recovery has additional environmental benefits by avoiding its disposal in landfills [18].

Steel slag is another secondary resource to consider. In regions that produce steel from titanomagnetic ores, such as China, Russia and South Africa, this slag contains significant amounts of vanadium that can be extracted using pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes [101,102].

In Europe, where vanadium mining is virtually non-existent, projects are being promoted to take advantage of this route: the Vanadium Recovery Project in Finland, which will enable vanadium to be recovered from slag and transformed into battery-grade V2O5, is a clear example of this trend, which is also in line with the objectives of the Critical Raw Materials Act by using industrial waste as a strategic source [23,103].

However, slag presents technical challenges such as variable composition, the presence of iron and titanium oxides, and energy-intensive separation processes [102]. Nevertheless, its volume and relative concentration make this source a potential pillar of secondary supply in a scenario of strong demand growth.

Challenges, prospects and opportunities.

The circularity of vanadium is still far from reaching its full potential. In the case of VRFB electrolyte, although the material is almost entirely recoverable, there is still no industrialised infrastructure for large-scale collection and reprocessing. As the first large-scale projects reach the end of their useful life, it will be necessary to develop logistics chains and regulations to ensure proper management of the electrolyte, similar to what happens with other hazardous waste.

In the field of catalysts, the main limitation is the fragmentation of the collection chain: the existence of multiple suppliers and intermediate managers increases costs and hinders traceability. As for slag, the challenge lies in the efficiency of metallurgical recovery processes and economic viability in the face of volatility in the vanadium market.

The EU, through the CRMA and the Net-Zero Industry Act, has set binding recycling capacity targets for critical raw materials, including vanadium [23]. However, turning these targets into operational chains requires investment in R&D, pilot plants and public–private partnership schemes, which are still in their infancy.

Nevertheless, developing these circular vanadium chains offers significant strategic benefits:

- Reduced dependence on imports, a primary market that is highly concentrated geographically.

- Mitigation of price volatility, by having a buffer stock of secondary supply.

- Reduced environmental footprint, by avoiding primary mining and revaluing waste.

Looking ahead to the coming years, VRFB electrolyte is expected to emerge as the main vector of this circularity as the deployment of this technology increases and secondary markets for reconditioned electrolyte appear. At the same time, spent catalysts will continue to provide a constant flow, while steel slag could become established in Europe and other regions as a strategic supply.

3.3.6. Catalysts and Emissions Control: Adjacent Contributions

Vanadium has found one of its longest-standing and most stable uses in catalysis, with a relative weight less than that of steelmaking, but with significant strategic importance. Two areas account for the bulk of this application: the production of sulphuric acid using the contact process and selective catalytic reduction systems for NOx abatement. Both examples illustrate how vanadium can contribute indirectly to the energy transition: by supporting essential chemical infrastructure for fertilisers, materials and metallurgy on the one hand, and by enabling compliance with air quality regulations in industrial sectors on the other [104].

Vanadium in the production of H2SO4.

Sulfuric acid is, in terms of tonnage, the most manufactured chemical in the world, with volumes exceeding two hundred million tonnes per year [105]. Its industrial production is based on the contact process, in which sulfur dioxide is oxidised to sulfur trioxide and then absorbed in water to form sulfuric acid. Although platinum was historically used as a catalyst, since the mid-20th century it has been replaced by systems based on V2O5 supported on silica and promoted with potassium or caesium, as these have a better cost/efficiency ratio and greater resistance to poisons such as arsenic.

This catalyst has an average life of between two and five years, although it could last up to 10 years if conditions are right. Once exhausted, it still contains a certain percentage of vanadium, which makes it a valuable waste product from a recovery perspective. Through leaching processes (acid or alkaline), followed by selective precipitation, yields of over 80–90% can be achieved and high-purity V2O5 can be obtained [98,99].

The recycling of these catalysts has a dual benefit: it avoids the disposal of hazardous waste in landfills and creates a stable secondary stream of vanadium.

Vanadium in selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of Nox.

The second major field of application is in the reference technology for the removal of NOx from combustion gases in thermal power stations, incinerators and industrial boilers. The system is based on the reaction of NO and NO2 with ammonia, in the presence of a catalyst, to produce nitrogen and water. The most common catalysts are those based on V2O5, as they offer an excellent balance between cost, activity and robustness [106].

Although the active phase is present in proportions of less than 2% by weight of V2O5, it is decisive for conversion, achieving an efficiency of more than 90% in NOx reduction [107]. At the end of its useful life, recycling is possible at rates that, under optimal conditions, can reach 80–90% [108,109].

Although the catalytic applications of vanadium do not account for volumes comparable to those of steelmaking or VRFBs, its relevance in the energy transition can be summarised in three reasons:

- This is a critical chemical infrastructure, as H2SO4 production supports key industries and, at present, there is no mature large-scale substitute for vanadium as a catalyst.

- SCR catalysts enable industrial plants to meet increasingly stringent NOx limits, reducing impacts on health and the environment.

- At the end of their life, these catalysts become a resource that can reintroduce vanadium into the value chain.

3.3.7. Titanium Alloys and Other Specialty Uses

Among titanium alloys, the most notable application is the Ti-6Al-4V alloy, also known as grade 5. This is a compound consisting of 4% vanadium, which accounts for more than 50% of the titanium used in structural applications [110]. Vanadium acts as a phase stabiliser, which allows the microstructure to be controlled, improving mechanical strength and maintaining a good combination of lightness, fatigue resistance and fracture toughness [111].

The use of these titanium alloys extends to fields as varied as [112]:

- The aeronautical and aerospace industry, where, thanks to the weight reductions achieved, savings are made in fuel and CO2 emissions. It is used in the manufacture of fuselages, turbines and anchoring systems.

- The biomedical industry, as it is a biocompatible material that is resistant to corrosion in physiological environments.

- Defence, as it can be used to manufacture lightweight armour and certain weapon components.

- Sport, where its balance between strength and lightness is very suitable.

In addition to the above, vanadium can be found in other smaller but equally strategic fields:

- Superalloys for turbines, where it helps to improve resistance to high temperatures and corrosion [113].

- Special pigments and glass [114].

- Electronics and advanced materials, such as infrared sensors or materials with thermal switching properties, thanks to its reversible metal-insulator phase transition at 68 °C [115].

- Fine chemistry and specialised catalysis for the oxidation of light hydrocarbons and other special chemical processes [37].

Although these are ‘niche’ profiles, the recovery of vanadium in these sectors could be particularly interesting in some cases. In removed implants and discarded aeronautical components, the content is high enough to justify recycling. In general, no significant growth in the use of vanadium is expected in these sectors, although this will depend on their evolution.

3.3.8. Market Structure and Price Dynamics

The global vanadium market has a unique structure characterised by (i) high geographical concentration, (ii) strong dependence on the steel industry, and (iii) marked price volatility. These characteristics not only affect supply stability but also have direct implications for the competitiveness of emerging applications such as VRFBs.

Primary vanadium production is concentrated in a few countries—in 2023, nearly 90% of global supply came from China and Russia, with a very similar figure for 2024 [107]. China is by far the leading producer, accounting for more than half of global supply.

A distinctive feature of this market is that more than 70% of the world’s vanadium is obtained as a by-product of the processing of titanomagnetic ores and steel slag. This means, as has been established throughout this paper, that the availability of vanadium is linked to the dynamics of steel especially high-strength steels [102,116]. Primary vanadium mining is currently practically marginal and, although there are mining projects in countries such as Australia and Canada, the cost of mining and processing is usually less competitive than that of vanadium obtained as a by-product [38].

Another distinctive aspect is the concentration in the processing value chain. Although the raw material can be generated in several regions, the conversion of intermediate (V2O5) or final (ferrovanadium) products is controlled by a small number of companies. This control over the refining stage gives certain players the ability to influence the global availability of vanadium products with the qualities demanded by the market [117].

In terms of products, the market is structured in three main ways:

- Ferrovanadium (FeV), mainly used in microalloyed steels.

- Vanadium pentoxide (V2O5), used as a precursor for alloys, catalysts and, more recently, in electrolytes for VRFBs.

- High-purity vanadium, with specialised applications in aeronautics, biomedicine and electronics.

The combination of these characteristics—geographical concentration, dependence on the steel industry and control of refining by a few players—makes the vanadium market structurally vulnerable to local disruptions, the effects of which are amplified on a global scale.

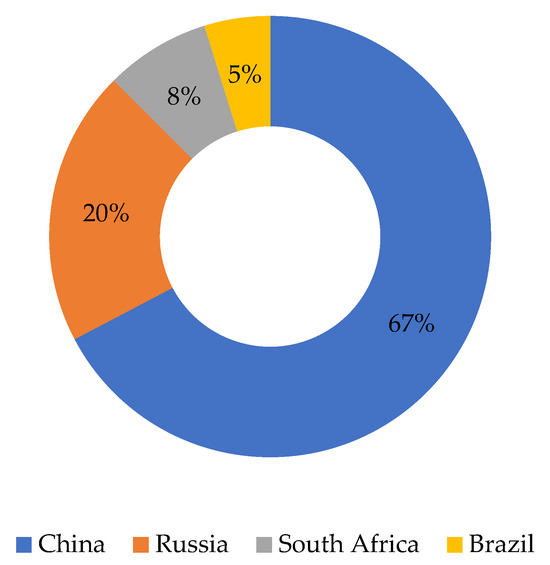

International trade in vanadium clearly reflects the asymmetry between a highly concentrated supply and a geographically diversified demand. The market thus faces a twofold complexity: profound structural interdependence with the volatile steel sector, contrasted with the rapid emergence of VRFB demand, which is projected to reconfigure the global market balance in the coming years (Figure 3) [17].

Figure 3.

Estimated annual vanadium production by country in 2024 [17]. The total production is 104,000 tonnes, and the percentages have been calculated relative to this total.

To quantitatively assess the degree of market concentration, the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) was calculated based on 2024 production shares (China 67%, Russia 20%, South Africa 8%, and Brazil 8%). The resulting HHI value of approximately 5000 indicates a highly concentrated market structure, exceeding the 2500 thresholds commonly used by the European Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice to define oligopolistic markets. Such concentration underscores the vulnerability of the global vanadium supply chain to geopolitical and policy disruptions.

On the demand side, estimates for 2024 place consumption at around 103,000 tonnes, in balance with available supply, but with a strongly skewed sectoral distribution: around 85–90% of vanadium is used in steelmaking, while the rest is used in catalysts, special alloys and, more recently, redox flow batteries, as mentioned in previous sections.

China not only dominates mining production, but also the processing and export of V2O5 and FeV (the former is the raw material for VRFBs and the latter is used to manufacture microalloyed steels). At the same time, it is a large domestic consumer, especially in its steel industry. Russia and South Africa stand out as exporters to Europe and the United States, while Brazil is emerging as an alternative supplier [17].

This dependence creates structural vulnerability, and any disruption has immediate repercussions on global availability and prices. This situation is reinforced by the fact that vanadium supply is largely a by-product of steelmaking, so its production does not respond to the needs of the vanadium market, but rather to the dynamics of the steel industry.

Without attempting to provide an exhaustive study of price developments in this section, we would like to highlight the volatility of prices and justify, in part, the three structural factors to which they respond: (i) the high concentration of supply; (ii) the nature of vanadium as a by-product of steel; and (iii) the limited liquidity of the market, where relatively small changes in production or demand can generate significant fluctuations. The prices referred to are those of V2O5 and FeV, as the other products mentioned above do not usually have public prices and are traded in small volumes through bilateral contracts.

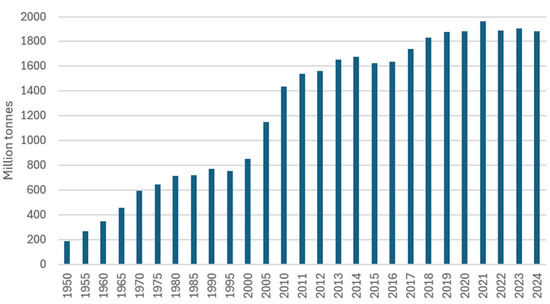

Demand for vanadium remains closely linked to the steel cycle (Figure 2 and Figure 4), which makes its market highly dependent on the global industrial situation. However, historical price fluctuations also respond to commercial and geopolitical factors. Between 1994 and 2003, there was a sustained increase in prices, culminating in an episode of overproduction, followed by a sharp decline. The closure of mines such as Windimura (Australia) and Vantec (South Africa) led to significant price rebounds around 2004. Conversely, periods of exploration expansion and increased production, particularly between 2010 and 2014, tended to stabilise prices [38].

Figure 4.

World Crude Steel Production 1950 to 2024. Source from [118].

Over recent decades, price variations have exceeded 100% at certain intervals, highlighting the structural fragility of the vanadium value chain. Volatility is not a recent phenomenon: since the 1990s, exogenous events—such as the liquidation of strategic reserves in the United States—have exerted downward pressure on the price of V2O5. In contrast, industrial crises, such as the bankruptcy of EVRAZ Highveld Steel & Vanadium Ltd. in South Africa or the power cuts that affected its production in 2008, reduced supply and drove up prices [38].

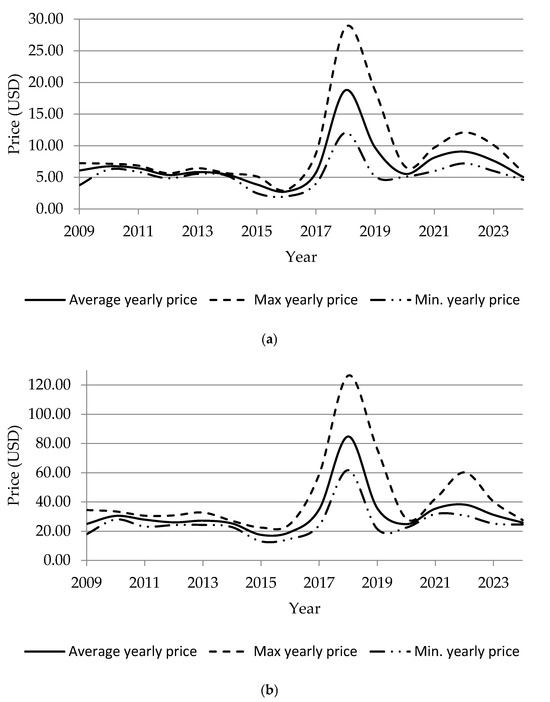

Looking at a more recent time frame, other relevant events can be highlighted. Between 2017 and 2018, China decided to tighten construction standards for reinforcing steel, causing a sudden increase in demand for FeV. In just one year, the price of V2O5 rose from £10/kg to over £30/kg, while FeV in Europe reached highs of around £125/kg [119]. The situation reversed in 2019, when prices plummeted to £7–8/kg for V2O5 and £40–45/kg for FeV in Europe. The market gradually recovered in 2020–2021, against a backdrop of logistical tensions and expectations regarding the deployment of VRFBs, with V2O5 settling above £10–11/kg and FeV exceeding £60/kg. The war in Ukraine and restrictions on Russian exports added further uncertainty during 2022–2023, keeping V2O5 in a range of £9–12/kg and FeV between £50–70/kg, with peaks linked to the global energy crisis [120]. In 2024, the market entered a phase of relative stabilisation, with intermediate values of £8–9/kg for V2O5 and £45–55/kg for FeV, reflecting a temporary balance between steel demand and emerging pressure from the energy sectors (Figure 5) [17].

Figure 5.

Historical evolution of (a) V2O5 and (b) FeV (80%) prices in the European spot market, showing average, maximum, and minimum values. Data derived from investing.com (values in USD). Some differences with values cited in the literature are expected, as published sources may refer to different markets, purity grades or data aggregation methods. Data available up to November 2024.

The causes of these fluctuations are due to a combination of factors. The steel industry, which consumes more than 85% of vanadium, remains the main driver: any regulatory changes, such as those that occurred in China in 2018, have an immediate impact on the prices of V2O5 and FeV. The nature of vanadium as a by-product of steel production introduces rigidity into supply, as it depends on steel dynamics rather than specific demand for the metal, which amplifies volatility. In addition, the small size of the market encourages speculation and limits liquidity. Added to this are geopolitical factors, such as export restrictions in China, sanctions on Russia, disruptions in South Africa, and exposure to energy costs, which particularly affect V2O5 processing.

The future of the vanadium market will be determined by the interaction between two major vectors: traditional demand linked to steelmaking and emerging demand associated with green energy technologies, particularly VRFBs.

In the steel sector, vanadium is expected to maintain its essential role as a microalloying agent in high-strength steels. Growth in construction in emerging markets, together with policies promoting stricter safety and durability standards in infrastructure, will ensure stable and even growing demand for FeV and V2O5. China will remain the epicentre of this consumption, but other developing countries such as India and some Southeast Asian nations will increase their relative weight in the coming years [17].

However, the most significant change will come from the energy sector. Some studies [121] project that demand for vanadium for VRFBs could increase five-fold or even ten-fold by 2030, depending on the speed at which these systems are integrated into electricity grids. Therefore, if the large-scale projects planned in China, Australia or Europe materialise, they could have a significant impact.

Finally, public policies and regulatory frameworks will play a crucial role in market prospects. The inclusion of vanadium in the European Union’s list of critical raw materials (Table 2) and strategic minerals in the United States underlines its strategic importance and anticipates measures to support supply diversification and the promotion of local value chains. At the same time, energy transition policies will determine the scale of future demand.

All this serves to highlight that the vanadium market is at a turning point. The steel industry will continue to provide a solid basis for consumption, but it will be energy applications that determine the degree of expansion or pressure on supply. The extent to which diversification, recycling and price stabilisation strategies are successfully implemented will be decisive in consolidating vanadium’s role as a critical material in the transition to sustainable energy systems.

3.4. Synthesis of the Strategic Diagnosis: Integrating External Vulnerabilities and Internal Strengths for EU Policy Formulation

3.4.1. External Environment Analysis

At the European level, the Green Deal sets climate neutrality for 2050 and calls for the massive replacement of fossil fuels, as well as the deployment of enabling technologies to make the transition fair, competitive and prosperous (Table 4). This change is not insignificant: it relies on the intensive use of raw materials to manufacture renewables, networks, storage, electric mobility and low-emission industrial processes. With this premise in mind, in 2008 the European Commission launched the Raw Materials Initiative (RMI), articulated in three objectives (‘three pillars’) that remain fully valid [54]:

Table 4.

PESTEL.

- Ensure a fair and sustainable supply from global markets.

- Promote responsible supply within the EU itself (exploration, mining and processing with high standards).

- Reduce dependence on primary raw materials through resource efficiency, recycling and substitution.

The PESTEL analysis underscores the central paradox facing the EU: a high level of policy ambition coupled with persistent structural dependence on external sources of vanadium. The coincidence of high geopolitical dependence (P1) and structural economic volatility (E1, E3) represents the EU’s most significant vulnerability in the value chain. This fragility is constrained by trade tensions (P5) and the absence of domestic extraction capacity, even as EU policy (P2, P4) attempts mitigation. Economically, high CAPEX requirements (E3) and price volatility (E1) directly amplify investment risk and negatively influence the LCOS/LCOE of VRFB systems (E2). However, the growing market outlook for long-duration energy storage (LDES) (E4) provides an opportunity for stable demand growth if supported by adequate policy and financing mechanisms.

From a technological and regulatory perspective, the analysis identifies clear opportunities counterbalancing these structural weaknesses. The maturity of VRFB technology (T1) and Europe’s innovation potential in green extraction and recycling processes (T3, E4) illustrate the region’s capacity to lead in sustainable technological development. Nonetheless, the lack of large-scale industrial recycling facilities (T2) and competition from emerging chemistries (T4) pose significant barriers to scaling up vanadium-based storage systems. Social and environmental dimensions add further complexity: while public support for renewable energy and circular economy initiatives is increasing (S1, S3), social opposition to new mining projects in Europe (S2) and limited technical training in vanadium metallurgy (S5) may hinder domestic resource development. Legally, the EU benefits from a robust regulatory framework, as demonstrated by vanadium’s inclusion in the Critical Raw Materials List (L1) and the strategic provisions of the ECRMA (L2–L3), which reinforce environmental standards and supply security requirements. Despite these vulnerabilities, the macro-environment offers clear opportunities (E4, T1, T3). The EU benefits from a robust regulatory framework (L1–L3) and technological leadership in VRFB (T1) and green recycling (T3, E4). In synthesis, the central paradox is encapsulated by the coexistence of strong legal and technological foundations with persistent structural dependence on external sources of vanadium.

The threat of new entrants to the European vanadium market (Table 5) is particularly high, mainly due to a combination of financial, regulatory and geological barriers. The CAPEX associated with greenfield mining projects is extremely high, as these are metals with low concentrations and complex metallurgy, where errors in cost or reserve estimates can compromise the viability of entire projects [146,147,148]. Added to this factor are the highly restrictive environmental licences in the European Union, which slow down or even block extraction initiatives, making it very difficult for new players to enter the market without prior strategic alliances.

Table 5.

Porter.

The most critical structural feature of the global vanadium industry, confirmed by Porter’s 5+2 model, is the unprecedented bargaining power of suppliers. This is driven by extreme geographical and production concentration (2.1–2.3), granting suppliers extraordinary market influence—a dynamic reinforced by vertical integration (2.5) and state export controls (2.3). Concurrently, the threat of new entrants remains structurally low (1.1–1.3) due to high CAPEX, complex metallurgy, and stringent environmental permitting (1.2). This combination of upstream concentration and high entry barriers severely limits competition and contributes to sustained price volatility. Environmental permitting in Europe (1.2) and the lack of large-scale refining infrastructure create additional regulatory and financial barriers, meaning that new participants typically require strategic alliances or public–private partnerships to enter the market. This concentration of upstream power limits competition and contributes to sustained price volatility.

On the demand side, the bargaining power of customers is moderate and largely confined to a small number of VRFB manufacturers (3.1–3.5), whose dependence on long-term contracts and limited ability to switch chemistries constrain their negotiation leverage.

As for the threat of substitute products, the influence is moderate but growing. Although vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs) offer clear advantages in long-duration stationary applications—such as stability in 20,000 charge–discharge cycles and scalability of energy capacity—competing technologies such as lithium-ion batteries have dramatically reduced their levelized cost of storage (LCOS) over the last decade [1,12]. Likewise, advances in sodium-ion and new flow chemistries (Zn–Br, Zn–Cl, Fe-Cr, all-iron RFBs) reinforce competitive pressure [141,142,164,171].

Nonetheless, the EU can capitalize on the power of complementors (6.1–6.4)—particularly research institutions, component manufacturers, and energy system integrators—to stimulate innovation and reduce strategic dependency. Likewise, stakeholders and regulators (7.1–7.4), through the implementation of the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), environmental standards, and ESG investment criteria, exert growing influence over market structure and corporate strategies. These dynamics underscore the need for coordinated industrial and R&D policies, aligning supply diversification with technological innovation to strengthen Europe’s resilience in the vanadium value chain.

Finally, it should be noted that the geological deposits explored to date reveal a scarcity of identified deposits in Europe and their uneven global distribution. As mentioned above, 90% of exploited reserves come from titanomagnetite deposits located in China, Russia and South Africa [39,122]. In contrast, the European Union has no active vanadium mines.

Political and legal conditions, such as CRM regulation and trade restrictions, directly affect supplier bargaining power and market entry barriers. Technological and environmental drivers influence substitution risks and rivalry intensity, while economic volatility impacts both cost competitiveness and buyer behaviour. Table 6 provides an integrated analytical matrix summarizing these interrelations and illustrating how the external context shapes the competitive structure of the vanadium industry.

Table 6.

Integrated analytical matrix combining PESTEL and Porter 5+2 dynamics.

3.4.2. Internal Analysis

Vanadium is a critical element for the energy transition in Europe, as it combines two strategic applications: its use as a microalloying agent in high-performance steels, which reduces material intensity in emission-intensive sectors, and its central role in vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs), considered one of the most mature long-duration energy storage (LDES) technologies for stabilising electricity systems with high renewable penetration [1,6]. Internal analysis reveals a structural gap in the EU value chain (Table 7). While the European Union is a notable leader in VRFB research, technological development and design, as well as in the deployment of green financing policies and circular economy projects [129,172], it lacks its own extractive base to ensure a stable supply of the mineral. Currently, there are no actively operating vanadium mines in the EU, which means that it is almost entirely dependent on imports from countries with high geopolitical risks [39,122].

Table 7.

Internal analysis using Value Chain tools.