Probabilistic Assessment Method of Available Inertia for Wind Turbines Considering Rotational Speed Randomness

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Probabilistic Modeling of Rotational Speed: Develops a Copula-based joint probability model that captures the dependence between wind speed and turbine rotational speed, specifically accounting for uncertainties introduced by wake and wind shear effects under determined wind speed conditions.

- (2)

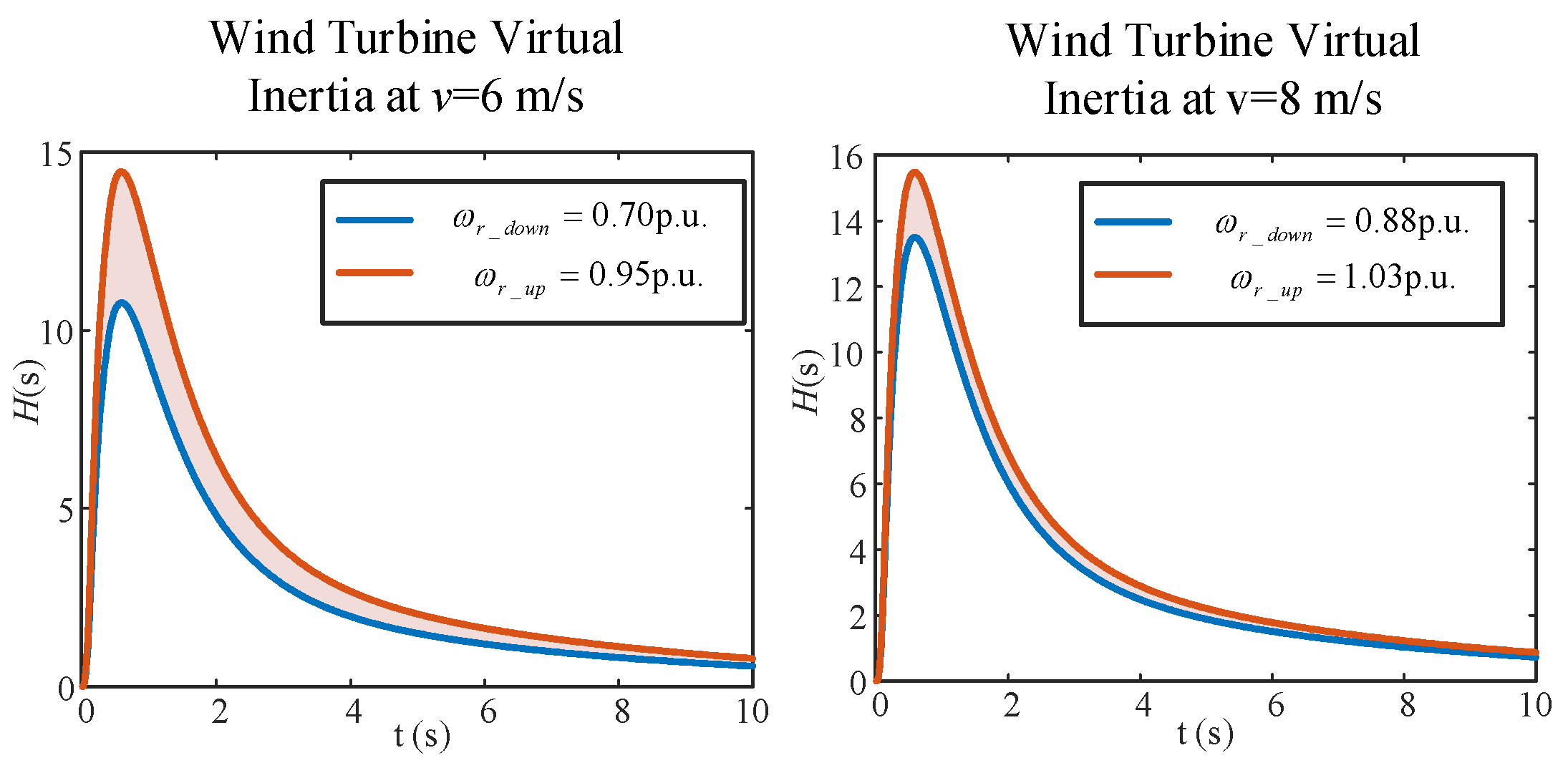

- Confidence-Aware Inertia Assessment: A probabilistic assessment method for the available inertia of wind turbines incorporating rotational speed randomness is proposed. It incorporates rotational speed randomness to generate confidence intervals for available inertia, enabling risk-informed power system planning.

- (3)

- Experimental Validation with Real Data: Utilizing actual operational data from a wind farm in China for case validation, showing a 6.5% improvement in estimation accuracy compared to deterministic methods and verifying that actual inertia values fall within the predicted 90% confidence bounds.

2. Joint Probability Distribution Modeling for Wind Farm Speed and Turbine Rotational Speeds

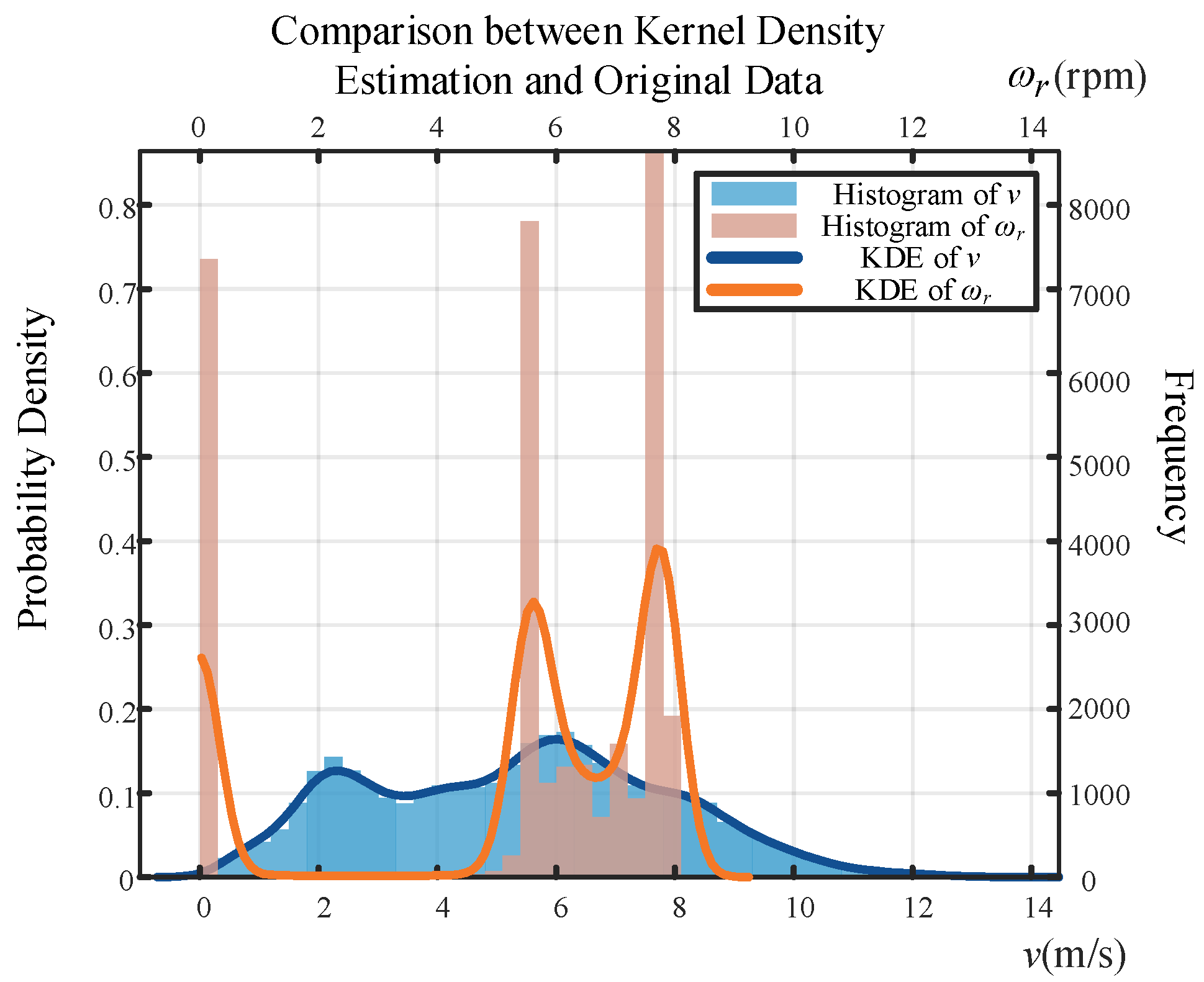

2.1. Modeling of Marginal Probability Distributions for Wind Farm Speed and Turbine Rotational Speed

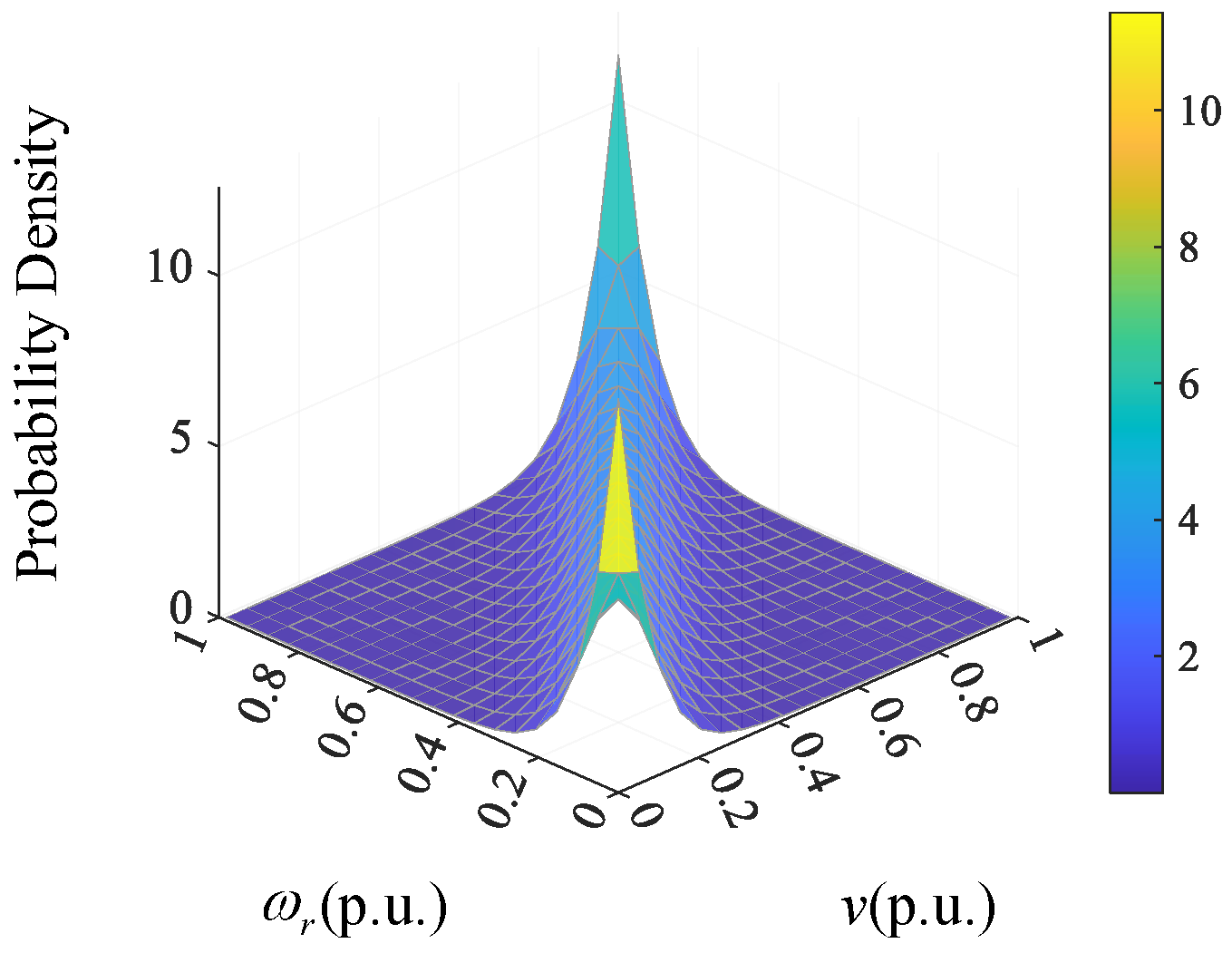

2.2. Copula-Based Modeling of Joint Probability Distribution for Wind Speed and Rotational Speed

2.3. Conditional Probability Distribution of Rotational Speed Under Given Wind Speed

3. Probabilistic Assessment Method of Available Inertia for Wind Turbines

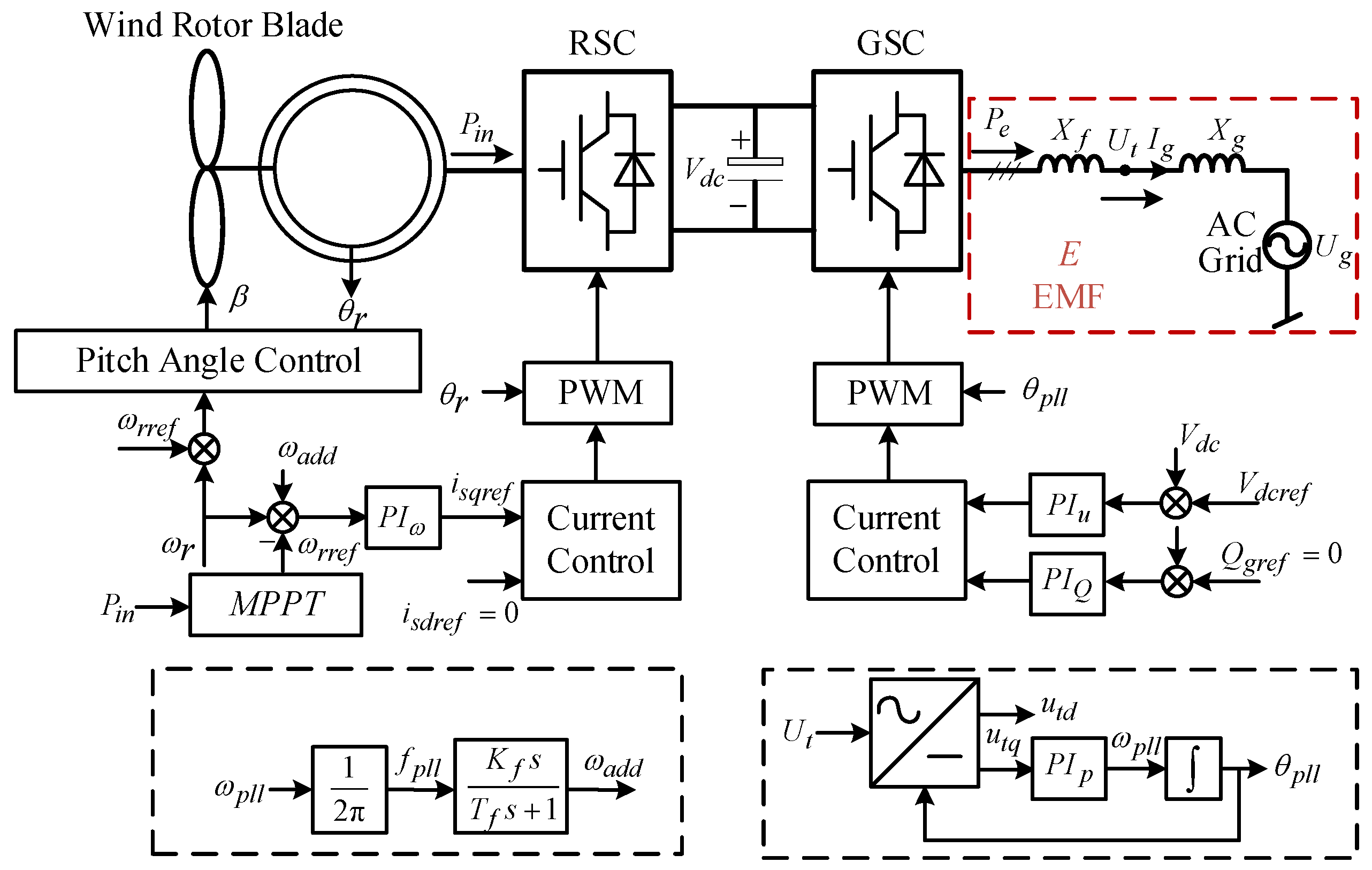

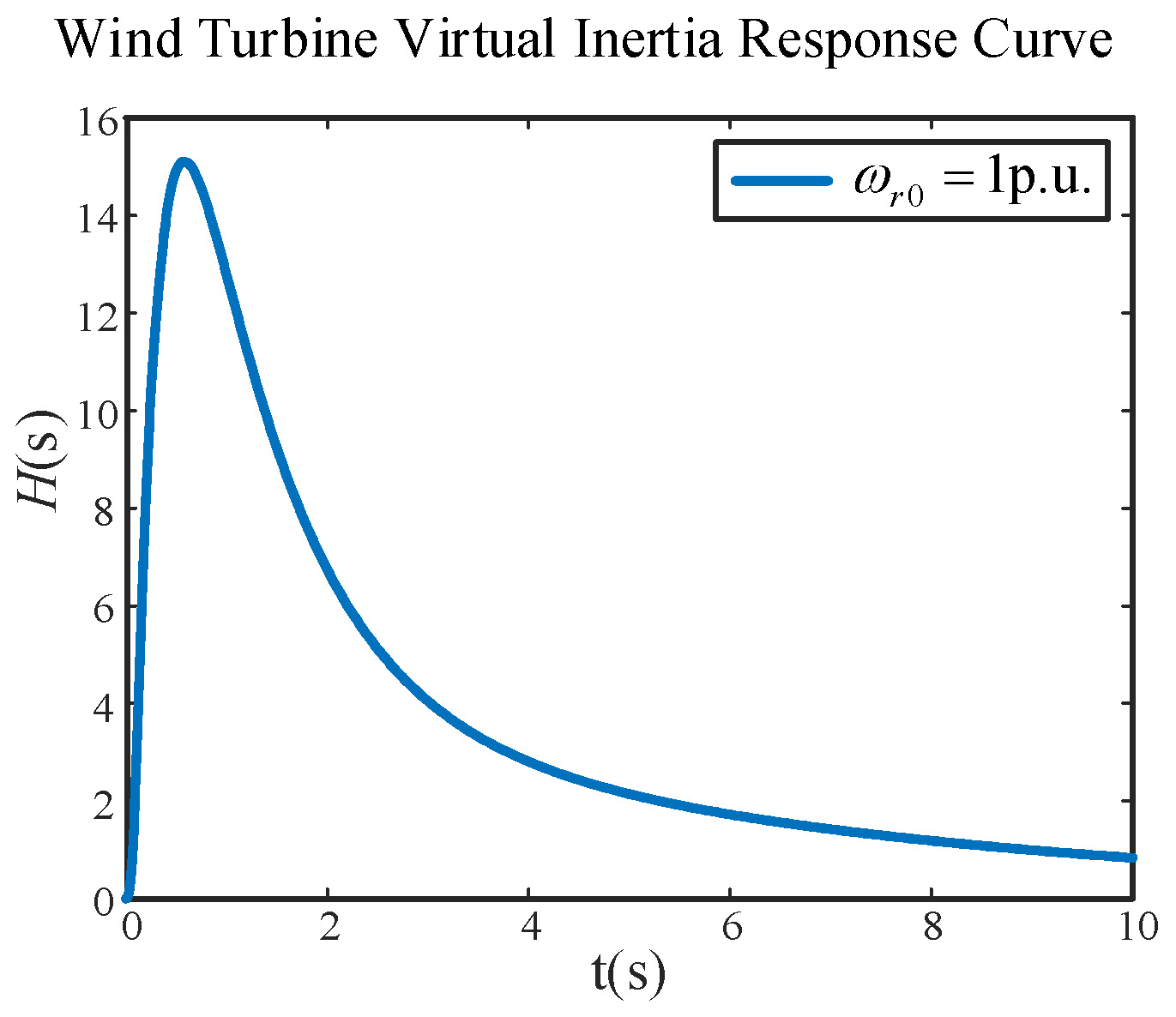

3.1. Characterization of Equivalent Inertia in Wind Turbines Under Determined Rotational Speed

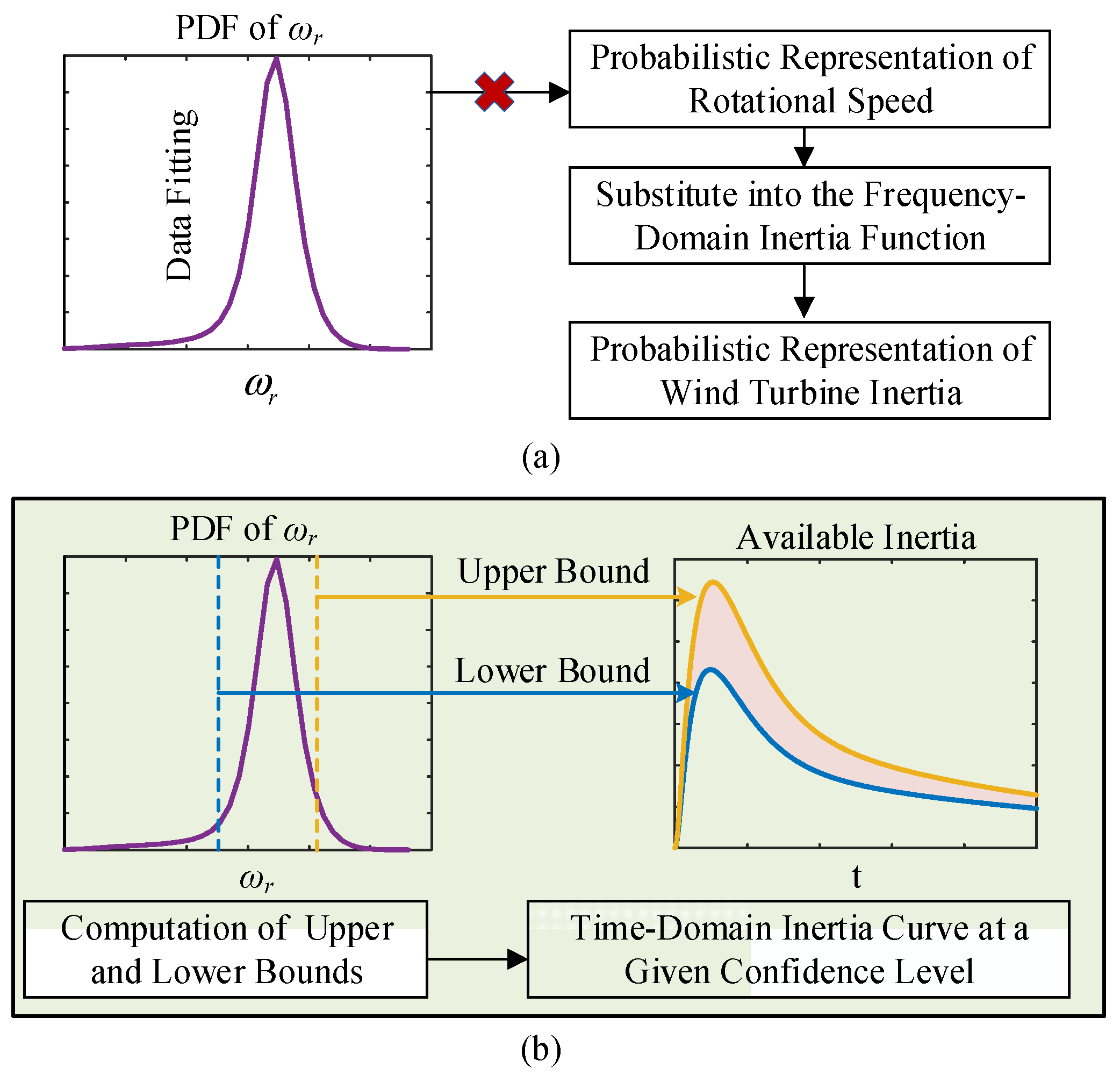

3.2. Probabilistic Assessment Framework for Wind Turbine Inertia Accounting for Rotational Speed Randomness

- Collect sample data and utilize kernel density estimation to approximate the discrete samples, determining the marginal probability density functions of wind farm speed and wind turbine rotational speed.

- Employ a Copula function to model the correlation between the marginal distributions, selecting the optimal Copula via an evaluation function to establish the joint probability distribution.

- Apply the bisection search-numerical integration method to compute the confidence interval of the rotational speed.

- Substitute the results into the inertia expression to obtain the upper and lower bounds of the wind turbine’s available inertia response curve for a specific confidence level α, ultimately achieving a probabilistic characterization of the wind turbine’s available inertia.

4. Case Study

5. Conclusions

- A joint probability distribution model for wind farm speed and turbine rotational speed was developed using kernel density estimation and Copula function fitting, accurately characterizing the probabilistic distribution characteristics of turbine rotational speed under given wind speed conditions.

- A probabilistic assessment method for the available inertia of wind turbines was proposed by integrating the conditional probability density function of rotational speed. The actual operational data from a wind farm in Zhejiang Province of China fully validated the correctness of the proposed probabilistic assessment method. Case study results demonstrate the method’s superior reliability, successfully enclosing the actual inertia (12.3 s) within the 90% confidence band, whereas a conventional MPPT-speed-based assessment yields a 6.5% error under a 6 m/s wind speed condition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Copula Function | Probability Distribution Function | Scope of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Norm Copula | Symmetrically Distributed Data | |

| t-Copula | Data with High Tail Dependence | |

| Gumbel Copula | Data with Upper Tail Dependence | |

| Clayton Copula | Data with Lower Tail Dependence | |

| Frank Copula | Symmetrically Distributed Data |

| Name | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rated Capacity per Turbine | SN/MW | 9 |

| Total Installed Capacity | SN_WF/MW | 504 |

| Distance to Shore | d/km | 25 |

| Water Depth Range | h/m | 18–25 |

Appendix B

- Spearman Correlation Coefficient

- 2.

- Kendall Correlation Coefficient

- 3.

- Squared Euclidean Distance

| Name | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rated Power | PN/MW | 1000 |

| Rated Voltage | UN/kV | 211.508 |

| Equivalent Filter Reactance of Wind Turbine | Xf/Ω | 0.00016 |

| Rotor Moment of Inertia | J/(kg/m2) | 5.785 × 106 |

| Internal Electromotive Force (EMF) of Wind Turbine | E/kV | 211.6 |

References

- National Energy Administration. Grid Integration Performance of Renewable Energy Sources in 2024 [EB/OL]. 2025. Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/20250221/e10f363cabe3458aaf78ba4558970054/c.html (accessed on 1 January 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zhu, D.; Guo, X.; Tang, B.; Hu, J.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y. Feedforward Frequency Deviation Control in PLL for Fast Inertial Response of DFIG-Based Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Lu, M.; Hang, L.; Zeng, P.; Liu, Y. Capacitor Voltage Imbalance Mechanism and Balancing Control of MMC When Riding Through PTG Fault. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, J.; Jenkins, N. Comparison of the response of doubly fed and fixed-speed induction generator wind turbines to changes in network frequency. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2004, 19, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Qiu, Y.; Hua, B.; Sun, D.; Nian, H. Asymmetrical Fault Ride-Through Enhancement for DFIG-Based WT Based on Sequence Coupling Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hu, J.; Lin, L.; Zeng, P.; Hang, L. A Generalized DC Asymmetrical Fault Analysis Method for MMC-HVDC Grids Considering Metallic Return Conductors. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 2568–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.K. Research on Time-Varying Rotating Inertia of Doubly-Fed Induction Generator. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.P.; Chen, P.F.; Ding, M.; Wu, H.B.; Dong, W. Quantitative Analysis of Inertia Support Capability of Direct-Drive Turbine Under VSG Control. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 501–510. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Sheng, S.; Zhou, Y.B.; Shi, Y. Evaluation of Equivalent Virtual Inertia of Wind Farm Based on Measured Data. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 1819–1829. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-H.; Wang, D.-L.; Sun, H.-N.; Lu, J.-Y.; Zuo, Y.-P.; Hu, J. Research on Inertia Characteristics and Minimum Inertia Evaluation Method of Doubly-Fed Wind Power System after Grid Connection. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2025, 20, 323–335. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.-D.; Liu, D.; Xu, B.; Ding, H.-Y.; Liu, J.-C. Quantitative Evaluation Method for Effective Support Capability of Virtual Inertia of Wind Turbines. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2024, 1–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-C.; Xu, S.-L.; Li, H.-Z.; Shu, Z.-Y.; Huang, S.-Y.; Tian, B.-J. Rapid Estimation of Equivalent Virtual Inertia of Wind Farm. Power Syst. Technol. 2021, 45, 4683–4692. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.-H.; Lu, Z.-X.; Qiao, Y.; Li, J.-M.; Chen, Y.; Guan, Y.-F.; Wang, T. Multi-time-scale Equivalent Inertia Mechanism Modeling of Direct-drive Wind Turbines Based on Full-order Model. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 79–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.W.; Zhang, W.M.; Zhang, Y.F.; Liu, Z. Circular-linear-linear probabilistic model based on vine copulas: An application to the joint distribution of wind direction, wind speed, and air temperature. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerod. 2021, 215, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-Q.; Yao, L.-Z.; Xu, J.; Cheng, F.; Mao, B.-L.; Wen, Z.; Chen, R.-S. Probabilistic Evaluation of Equivalent Inertia for High-Penetration Renewable Energy Power Systems Based on Slice Sampling-Markov Chain Monte Carlo Simulation. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W.-Z.; Xu, L.; Yao, Y. Estimation of Available Inertia in Wind Farms Considering Wind Speed Distribution and Turbine Inertia Conversion Uncertainty. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. 2021, 55 (Suppl. S2), 51–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, C. Generation of Scenic Output Scenarios Based on Copula Theory. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Hangzhou, China, 27–29 December 2024; pp. 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- Su, R.; Wang, P.; Li, C.; Qi, H.; Wang, J. Scenario Generation of Multiple Wind Farm Power Output Considering Spatial Correlation Based on Vine Copula. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Energy, Electrical and Power Engineering (CEEPE), Yangzhou, China, 26–28 April 2024; pp. 1317–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Zou, X.; Zhou, S.; Dong, W.; Kang, Y.; Hu, J. Feedforward Current References Control for DFIG-Based Wind Turbine to Improve Transient Control Performance During Grid Faults. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2018, 33, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, D.; Hu, J.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y.; Guerrero, J.M. Inertial PLL of Grid-Connected Converter for Fast Frequency Support. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Zhu, D.; Hu, J.; Liu, R.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y. Inertia Evaluation and Optimal Design for PMSG-Based Wind Turbines With df/dt Control. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, R. Wind Power Curve Modeling With Hybrid Copula and Grey Wolf Optimization. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Song, Y.H. Theories, Methodologies and Applications of Probabilistic Forecasting for Power Systems with Renewable Energy Sources. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 45, 2–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Khorramdel, B.; Chung, C.; Safari, N.; Price, G.C.D. A Fuzzy Adaptive Probabilistic Wind Power Prediction Framework Using Diffusion Kernel Density Estimators. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 7109–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Hou, Y. Probabilistic Forecast for Multiple Wind Farms Based on Regular Vine Copulas. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Copula Type | Spearman Correlation Coefficient | Kendall Correlation Coefficient | Squared Euclidean Distance | Elv Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norm Copula | 0.8335 | 0.7021 | 13.5298 | 0.5177 |

| t-Copula | 0.8954 | 0.7229 | 11.0272 | 0.3402 |

| Gumbel Copula | 0.8672 | 0.6889 | 21.2174 | 0.8821 |

| Clayton Copula | 0.8137 | 0.6289 | 24.7135 | 2.0960 |

| Frank Copula | 0.9276 | 0.7597 | 5.0905 | 0.1640 |

| Original Data | 0.9162 | 0.7409 | / | / |

| v (m/s) | ωr (p.u.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.5, 0.625] | [0.625, 0.75] | [0.75, 0.875] | [0.875, 1] | [1, 1.125] | |

| 2 | 0.0263 | 0.0960 | 0.0026 | 0.0004 | 2.14 × 10−6 |

| 4 | 0.0396 | 0.6402 | 0.0606 | 0.0090 | 5.46 × 10−5 |

| 6 | 0.0014 | 0.1610 | 0.4358 | 0.2891 | 0.0025 |

| 8 | 3.0 × 10−5 | 0.0042 | 0.0338 | 0.7692 | 0.1031 |

| 10 | 4.4 × 10−6 | 0.0006 | 0.0051 | 0.3945 | 0.4362 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Liu, J.; He, Z.; Wang, C.; Qiu, C.; Gu, Y.; Pan, X. Probabilistic Assessment Method of Available Inertia for Wind Turbines Considering Rotational Speed Randomness. Energies 2025, 18, 6457. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246457

Ma J, Liu J, He Z, Wang C, Qiu C, Gu Y, Pan X. Probabilistic Assessment Method of Available Inertia for Wind Turbines Considering Rotational Speed Randomness. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6457. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246457

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Junchao, Jianing Liu, Zhen He, Chenxu Wang, Congnan Qiu, Yilei Gu, and Xing Pan. 2025. "Probabilistic Assessment Method of Available Inertia for Wind Turbines Considering Rotational Speed Randomness" Energies 18, no. 24: 6457. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246457

APA StyleMa, J., Liu, J., He, Z., Wang, C., Qiu, C., Gu, Y., & Pan, X. (2025). Probabilistic Assessment Method of Available Inertia for Wind Turbines Considering Rotational Speed Randomness. Energies, 18(24), 6457. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246457