Abstract

Offshore wind (OSW) energy represents a vast and largely untapped resource capable of significantly contributing to the rising global electricity demand while advancing ambitious decarbonization and clean energy transition goals. Despite its potential, the effective harnessing of OSW is contingent upon the strategic and reliable integration of offshore generation into existing onshore AC power systems. Multi-terminal high-voltage direct current (MTDC) networks have emerged as a promising solution for this task, offering enhanced flexibility, scalability, and operational resilience. However, several technical and operational challenges—such as lack of standardization, coordinated control of multiple multi-vendor converters, reliable communication infrastructures, protection schemes, and seamless integration of offshore HVDC substations—must be addressed to fully realize the benefits of MTDC systems. This review paper critically examines these challenges and proposes a control, communication, protection, and HVDC substation design that could be adopted as an initial guideline for the efficient and secure integration of OSW into AC grids. By identifying current research gaps and synthesizing existing solutions, the paper provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing the role of MTDC networks in future offshore wind deployments.

1. Introduction

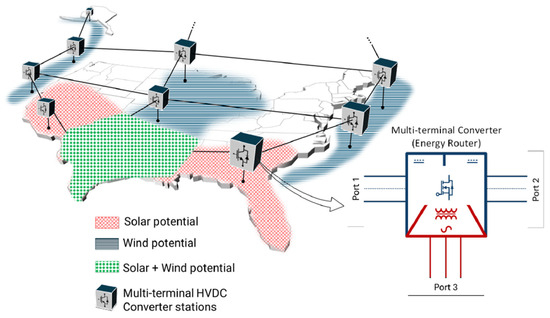

Power systems are transitioning towards decarbonization with the widespread incorporation of renewable energy sources, replacing conventional power plants. Injection of clean energy into the grid is expected to increase substantially in the forthcoming years [1,2,3,4,5]. This will lead to significant growth of variable energy resources (VER), such as solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind farms. Load centers along U.S. coastlines stand to benefit from massive Offshore wind (OSW) resources that are closer than land-based wind and solar. The prospect of integrating these OSW resources with the onshore grid has stimulated discussions of the multi-terminal HVDC (MTDC) networks and their benefits of reliability, economy, and flexibility [6,7,8,9].

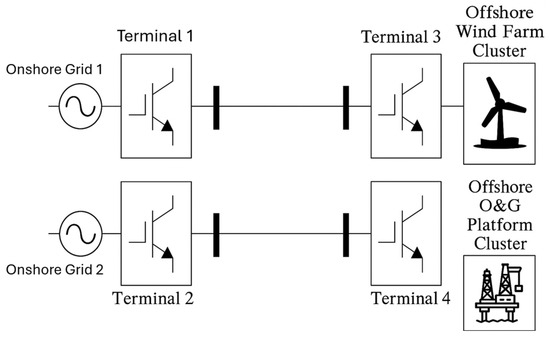

Figure 1 shows the simplest design for integrating an OSW cluster to the onshore grid via the MTDC network; it also shows that the same design could be used in supplying the electric needs of an offshore oil and gas platform, similar to what was considered in [10,11].

Figure 1.

An example MTDC network.

An MTDC-based offshore grid offers significant benefits:

- Reduction in the number of outages of OSW plants by providing alternate paths of power delivery

- Reduced OSW curtailments by redirecting power to other points of interconnections (POIs)

- Provision of ancillary services due to HVDC inherent capabilities

- Improved onshore grid reliability

- Additional transmission capacity and resulting reduction of onshore congestion costs

To maximize the benefits derived from OSW energy resources—such as increased reliability, ameliorated resiliency, congestion reduction, and increased capacity—the offshore grid must be planned prudently [12,13,14]. Presently, transmission development for OSW projects typically follows a project-focused, generator lead-line method. This methodology restricts the potential advantages of implementing a coordinated MTDC meshed network involving three or more terminals, which can offer more cost-effective transmission solutions [15,16,17]. Consequently, transitioning from simple radial topologies to meshed offshore grid designs is highly valuable and can yield significant long-term benefits. Although mesh-ready designs entail higher initial costs compared to radial configurations—estimated to increase OSW plant costs by approximately 0.4 to 2.5% [18]—the long-term operational and economic advantages justify this investment. A meshed grid can be established by interconnecting offshore substations of multiple adjacent wind farms, utilizing either HVAC or HVDC technologies depending on the inter-plant distance. HVAC interconnections offer lower costs, simpler technology and control schemes, and enhanced reliability; however, their power transfer capability diminishes over longer distances. In contrast, HVDC interconnections enable extended connection lengths and provide precise onshore power flow control but come with higher costs and the need for DC circuit breakers (DCCBs), which remain less mature compared to their AC counterparts [19,20,21,22]. Implementing mesh-ready designs requires additional infrastructure, including gas-insulated switchgear (GIS) cable bays at offshore substations, shunt reactors to manage cable charging effects (in AC tie configurations), larger offshore platforms, and comprehensive mesh operation studies. These studies are critical to ensuring effective grid control in meshed configurations and facilitating future upgrades as necessary.

For meshed networks, HVDC technology is an attractive way forward due to its ability to control power flow, its higher transfer capability (1200 MW/HVDC cable as opposed to 400 MW/HVAC cable), and its additional control capabilities, e.g., reactive power control and black start (B.S.). Offshore MTDC networks can provide substantial ancillary support to onshore AC transmission systems. By leveraging the fast and flexible controllability of VSCs, MTDC grids can deliver enhanced voltage-ride-through (VRT) capability, effective harmonic mitigation, synthetic frequency response, and B.S. support.

The B.S. of onshore grid from offshore HVDC systems varies slightly between point-to-point (PtP) and MTDC systems. In case of PtP, the offshore VSC-HVDC system self-starts its auxiliary systems using batteries, diesel generators (DGs), fuel cell, or uninterruptible power supply (UPS). The converter operates in grid-forming (GFM) mode and provides independent frequency and voltage control on offshore busbars to energize AC collection network and sequential turbines energization. Later, the DC cable link between offshore and onshore network is charged and the onshore converter is powered up with offshore converter in DC voltage control followed by restoration of the onshore grid. For MTDC networks, there should be at least one GFM converter terminal in the interconnected network that sequentially energizes the other terminals operating in GFL mode by providing the required DC reference. To speed up the B.S., multiple offshore converter terminals could be operated in GFM mode with robust communication for DC voltage control coordination and power sharing. The B.S. operation differs from the normal operation of the offshore integrated grid, in which the onshore converter is typically responsible for the DC voltage control due to its connection to a strong, stable onshore AC grid avoiding DC voltage fluctuations and resultant converter tripping, whereas the offshore converter performs the active power (P) control as it is connected to weak AC network formed by the offshore wind turbines.

A comparison of the above discussed schemes is presented in Table A1 in Appendix A.

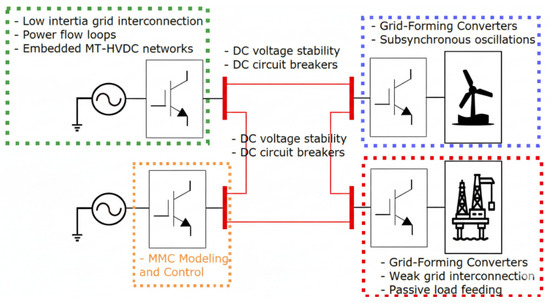

This paper reviews the control, communication, and protection challenges facing the deployment of MTDC-related inverter-based technology. The most critical challenges facing MTDC networks are highlighted in Figure 2. This paper also suggests technical ways to address some of these challenges.

Figure 2.

MTDC challenges.

Despite previous studies, such as [7,8,9,15] focusing solely on control and converter topology for MTDC networks, ref. [14] on reliability analysis of offshore networks, ref. [17] on performance evaluation of VSC-HVDC systems, refs. [19,20] on DCCB, and [23] on significance of communication in wind power applications, no comprehensive work exists that concurrently addresses MTDC control, communication, protection, and HVDC substation design in a single paper. In addition, the previous works lack a detailed review of MTDC standardization that is essential for seamlessly interconnecting and operating offshore MTDC networks with existing onshore and offshore networks. The above discussed aspects are comprehensively addressed in this paper, which enhances the significance of this work.

The next sections of the paper are organized as follows: Section 2 details the state of the art of MTDC standardization. Section 3 discusses the protection challenges and provides an initial set of guidelines for a reliable and resilient protection system design for OSW MTDC transmission systems. Section 4 focuses on the control challenges of MTDC systems, and Section 5 specifies the communication requirements and possible solutions for high-speed and reliable communication for effective OSW transmission. Section 6 concludes the paper by outlining a pathway toward the realization of fully integrated OSW grids.

2. State of the Art of MTDC Standardization

Numerous international organizations are actively developing standards to support the OSW sector. Major contributors include the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Det Norske Veritas (DNV), and the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS). Their work predominantly addresses mechanical and structural aspects—such as turbine blades, nacelles, towers, and support structures—along with requirements for fabrication, transportation, installation, and safety assurance [24,25,26]. Despite this progress, current standards provide limited technical guidance on the electrical design, operational strategies, and protection practices of OSW power systems. In particular, they do not address the unique challenges posed by MTDC offshore networks. There is growing consensus on the need for MTDC-specific standardization across four major areas: (i) performance requirements and grid code specifications, (ii) operational manuals tailored for Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) and Independent System Operators (ISOs), (iii) standardized utility interconnection procedures, and (iv) offshore electrical and structural design practices [27,28,29,30]. Although some functional aspects—such as active power regulation and fault-ride-through (FRT) capability—are partially covered under existing U.S. grid requirements (e.g., IEEE 2800–2022, FERC Large Generator Interconnection Agreement (LGIA), and North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) Reliability Standards for Bulk Electric Systems), these documents do not fully address advanced control modes, islanded or grid-forming operation, adaptive and hierarchical control architectures, or MTDC protection philosophies [31,32]. MTDC grids impose additional complexity due to the need for coordinated control across multiple converter stations, robust protection schemes, DCCBs, and standardized communication and interface protocols.

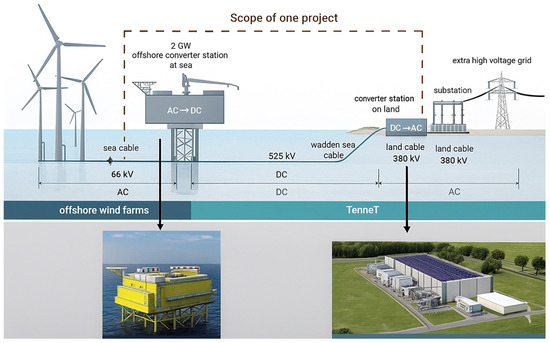

Historically, most HVDC installations in Europe—whether inland or offshore—have been deployed as PtP transmission systems. As the region accelerates efforts to meet its 2050 decarbonization and energy-security objectives, there is increasing emphasis on transitioning from isolated PtP links to interconnected MTDC grid topologies to improve reliability, system flexibility, and operational efficiency. Several European initiatives are now focused on formulating standards for these emerging multi-terminal configurations. One of the most prominent efforts is the 2-GW offshore HVDC standard proposed by TenneT, the transmission system operator (TSO) responsible for OSW integration in the Netherlands and Germany [33]. TenneT’s initiative aims to establish a harmonized technical framework for HVDC grid development across Europe. A key element of this framework is the adoption of modular “system blocks” with increased transmission capacity, enabling scalability and cost reductions through uniform design and mass deployment. When the required offshore transfer capability exceeds the rating of a single HVDC circuit, TenneT proposes deploying multiple identical system blocks to form clusters of standardized offshore transmission units. This modular architecture enhances redundancy and reliability, simplifies operational coordination, and reduces lifecycle costs. The proposed standard defines system blocks capable of transmitting 2 GW of offshore wind power to shore via ±525 kV HVDC links based on state-of-the-art voltage-source converter (VSC) technology [34].

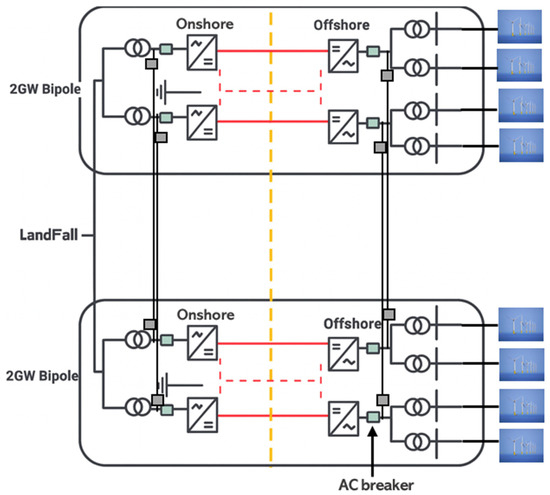

Figure 3 depicts the conceptual arrangement of a single 2-GW offshore HVDC system following the TenneT standard. These standardized system blocks are designed to accommodate equipment from multiple vendors, including HVDC converter transformers, auxiliary power units, and protection components such as integrated AC/DC switchyards and gas-insulated switchgear (GIS). The standard further aligns requirements for process automation, cyber-secure communication networks, thermal management systems, and operational procedures, thereby improving system interoperability and enabling streamlined multi-vendor integration.

Figure 3.

TenneT 2 GW offshore HVDC grid-connected system [34].

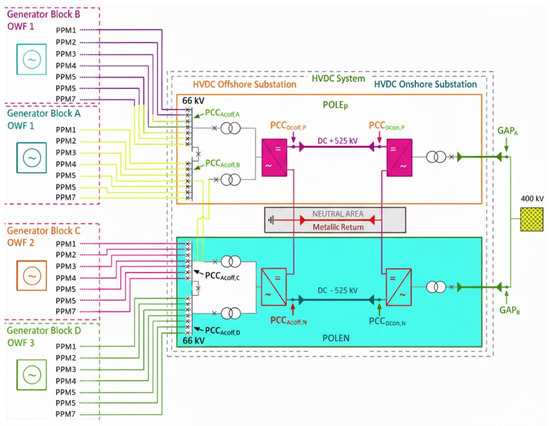

From an engineering perspective, the 2-GW reference architecture is based on a bipolar HVDC scheme incorporating a dedicated metallic return conductor, as shown in Figure 4. Alternatives that rely on ground-based return paths can reduce upfront infrastructure costs; however, they introduce additional complexities related to stray current interactions with subsea assets, including corrosion risks for pipelines and other marine structures. The bipolar arrangement offers a key operational advantage: continued power transfer at approximately 50% of rated capacity during the loss of a single pole, whether due to contingencies or planned maintenance. The offshore interface also includes a cross-linked configuration, which improves supply reliability and supports higher overall energy availability. Adopting a metallic-return bipole enables a modular system layout, allowing incremental build-out of the HVDC network. This expandability is particularly important for future scenarios in which OSW resources from multiple states could be interconnected through an Offshore Independent System Operator (O-ISO) framework. Moreover, the standardized and modular nature of the platform enhances interoperability, ensuring equipment from multiple HVDC vendors can be integrated and coordinated seamlessly across the system.

Figure 4.

2 GW bipole HVDC system [34].

The concept of aggregating OSW capacity into 2-GW clusters, each connected to shore through a single HVDC transmission corridor, has also been identified as the least-cost configuration in studies conducted under the PROMOTioN initiative (Progress on Meshed HVDC Offshore Transmission Networks) [35,36]. PROMOTioN—an EU-supported program active from 2016 to 2020—examined the broad spectrum of technical, regulatory, legal, and economic barriers associated with large-scale OSW deployment in Europe. Its system planning analysis was based on a long-term outlook that envisions 200 GW of offshore wind generation in the North Sea by 2050. Within this framework, the project recommended adopting 525 kV bipolar HVDC technology for North Sea applications, while 325 kV monopolar HVDC systems were deemed more suitable for anticipated developments in the Irish Sea. Overall, the PROMOTioN findings reinforce the growing international alignment around the use of standardized 2-GW offshore clusters as an efficient and economically robust approach for transmitting large volumes of OSW power to land-based grids.

3. Protection

The protection of MTDC systems is highly complex and necessitates the use of DCCBs. Various elements in DCCBs, including varistors, capacitors, inductors, and charging units, are critical to enhance interruption speed, and to reduce the size and associated cost [37,38,39,40]. The protection of HVDC systems is more complex than AC systems, because DC faults lead to large, instantaneous spikes in the current and have no zero crossing. The large instantaneous current is the result of the low impedance and inertia of HVDC systems, as well as the swift discharge of capacitors utilized in the converters. This necessitates a fault-clearing time of few milliseconds. For instance, the Zhangbei project in China has a fault-clearing time of 6ms [41,42]. Standard protection requirements in AC grids are also present in DC grids, including reliability, selectivity, sensitivity, speed, seamlessness, robustness, interoperability, and restoration.

HVDC protection schemes are either single-ended or double-ended, where the former doesn’t require any communication and the latter is based on communication [43]. The example of double-ended protection is differential protection, which becomes challenging for long transmission lines due to communication speed and strict data synchronization requirements. Therefore, single-ended protection schemes that rely on local measurements are widely recognized due to their enhanced speed and operation.

One of the protection strategies (Energy Router) that is capable of fully regulating the current, in addition to voltage and frequency, is shown in Figure 5. This converter station topology regulates the power flow bi-directionally, in addition to instantaneously blocking or reducing the current injection to the DC link during a fault by effectively acting as a solid-state breaker. However, this comes at an additional expense and is not applicable to the existing HVDC networks.

Figure 5.

MTDC multi-terminal multi-port station to regulate current, voltage, and reroute power as required [44].

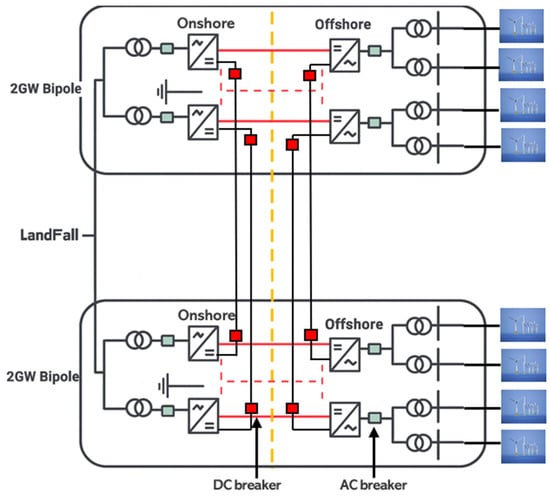

This section proposes a protection strategy using the TenneT 2 GW modules introduced in Section 2 as a reference. These 2 GW bipole modules can be interconnected via two primary approaches: AC-side interconnection or DC-side interconnection, as illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7 [33]. In the AC-side interconnection scheme (Figure 6), offshore and onshore connections are made on the AC side. This approach may offer a cost-effective solution for clusters of wind farms located in close proximity—typically within 50 miles—allowing the use of established AC protection devices. For longer AC interconnections, compensation with shunt reactors is required approximately every 50 miles to manage cable charging effects.

Figure 6.

AC-side interconnection of 2 GW bipole HVDC system.

Figure 7.

DC-side interconnection of 2 GW bipole HVDC system (MTDC system).

Conversely, DC-side interconnection is essential for long-distance transmission and for linking geographically dispersed offshore wind areas, as it eliminates the need for AC compensation reactors and networks. However, this method necessitates the deployment of DCCBs for protection, which currently remain costly and are available in limited voltage ratings. OSW grid designs are likely to adopt a hybrid configuration that combines these topologies to minimize capital and operational expenditures while maximizing reliability, redundancy, and availability. Such a modular and expandable approach could be realized by employing AC-side interconnections for converter stations located within 50 miles of OSW resources, and DC-side interconnections for more distant stations. Coordinated protection schemes between AC and DC sides of the converters will be essential to ensure system security and performance, as detailed in [35,36].

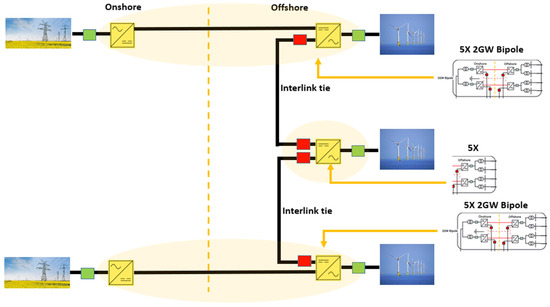

Figure 8 illustrates a conceptual offshore network configuration constructed using 2-GW bipolar HVDC modules, which are aggregated to form 10-GW offshore wind clusters. The design incorporates an inter-cluster tie line sized at 40% of the capacity of each cluster, a value aligned with the typical average annual offshore wind capacity factor of about 40%. This sizing ensures that the tie line can accommodate the majority of available generation under normal operating conditions, while limiting curtailment during contingency events or scheduled outages. In the configuration shown, the interlink is rated at 4 GW, corresponding to 40% of the total 10-GW generation capacity of the cluster. This approach provides N-1 contingency capability for the HVDC export paths, enhancing overall system robustness and ensuring high reliability and availability for OSW delivery to the onshore grid.

Figure 8.

Proposed High-level MTDC Offshore Back-Bone Grid Design.

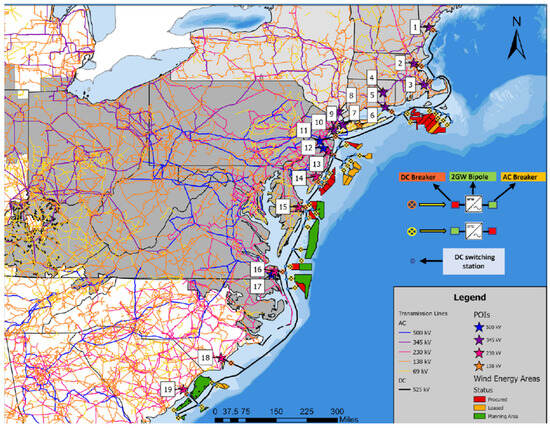

In this architecture, generation assets interface directly with the DC transmission network, or alternatively, the reference bus is provided through a DC switching station that incorporates a fractionally rated disconnect switch. The reduced rating of this switch is made possible by its coordinated operation with the AC/DC protection systems deployed at the associated offshore and onshore converter stations. The DC switching station plays a pivotal role by isolating faulty segments of the offshore network and enabling safe execution of maintenance activities. Where converter platforms are located in close proximity to the offshore grid, the DC switching station and DC circuit breaker can be consolidated into a single offshore platform, streamlining infrastructure and reducing installation complexity. Extending this concept, Figure 9 presents a conceptual 76-GW multi-terminal offshore HVDC grid for the U.S. East Coast, identifying nineteen potential onshore points of interconnection (POIs) that could serve as landing points for integrating future offshore wind developments with the existing onshore transmission system [45,46].

Figure 9.

Proposed MTDC Offshore Back-Bone Grid Design for the U.S. East Coast. Note: Numbers 1–19 represent potential POIs [45].

4. Control

There are several control challenges associated with the robust operation of MTDC networks, including a lack of standard detection and mitigation methods to address adverse control interactions among multi-vendor converters. PtP HVDC technology has been operational for decades; however, MTDC technology is relatively new and converter control in the case of more than 2 terminals presents challenges that may need to be addressed through large-scale demonstration projects prior to scaling up to the systems-level. Also, MTDC technology is more prone to utilizing converters from different manufacturers. This necessitates the development of innovative vendor-neutral controls that could enable the reliable operation of hybrid AC/DC systems through robust coordination between the AC and DC sides of OSW converters. Advanced control systems are essential to enhance the steady state and dynamic performance of converters for reliable operation during normal, fault scenarios, and extreme weather events. MTDC controls for offshore grids should utilize a scalable approach to enhance their reliability, redundancy, and expandability. The controller should be expandable to allow future OSW expansions by incorporating adaptable master/master and/or master/slave configurations [47,48,49].

VSC-HVDC converter, as opposed to line commutated converter (LCC) technology is best suited for the development of OSW grids, as this helps in providing advanced control features necessary for the realization of robust and supportive offshore grids. The VSC-HVDC has significant benefits, such as B.S. capability, compactness, ability to integrate into weak AC networks, and independent active and reactive power control. Modular multi-level converters (MMC) are typically utilized at the 320 kV or 525 kV levels required for OSW MTDC transmission. The MMCs require a complex control system to operate the converter terminal owing to the complex and interconnected internal dynamics of the converter, including DC voltage stability (within a 5% range), circulating currents, maintaining energy between phases and handling the total energy stored in the converter. There are also control challenges associated with mitigating sub-synchronous oscillations due to the interaction between the wind farms and converter stations. Primarily, the DC bus voltage is controlled by one of the converter stations (master), and the other station (slave) utilizes the PQ control [50]. The more advanced version utilizes droop-based control where the active power (P) is modified in proportion to the variation in the DC voltage to achieve the desired DC voltage stability [51]. Reference [52] proposes a distributed voltage control scheme where the DC voltage control burden is shared by all the terminals in the network. An alternative to the conventional voltage droop characteristics of VSC stations is proposed in [53]. This technique introduces possible operation in three different control modes, including conventional voltage droop control, fixed active power control, and fixed dc voltage control. This enhances flexibility in active power sharing and power control as well as DC voltage control without active power oscillation during the transition between the different modes.

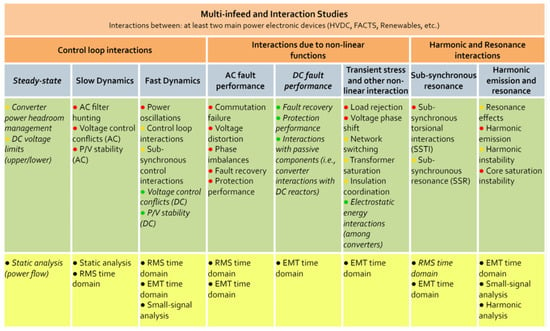

The control issues associated with MTDC networks could be addressed utilizing detailed real-time simulations, but it is still a complex process for large inverter-based systems. Converters from different vendors have variations in modeling, control tuning, and associated parameters. The interaction between converters and the network is highly critical. However, it is a challenging task due to the diverse parties involved, including manufacturers and TSOs, developers, and researchers. DC grids exhibit fast transients, which lead to more complexities in the interaction studies. There is a series of efforts underway to handle these interactions, including technical brochures from CIGRE, such as B4.81, B4.82, and B4.85 [54]. The interaction studies proposed in CIGRE B4.81 are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Interaction studies proposed in CIGRE 4.81 [54].

Inertia provision is another control challenge as solar panels and wind turbines are connected via inverters, which do not inherently provide traditional inertia, which reduces frequency control capability resulting in lower frequency nadirs following trips of large amounts of real power generation. However, this can be handled through virtual inertia provision by these power-electronics-based resources. A battery energy storage system (BESS) coupled into the WT system could provide inertia to complement these variable resources. Several techniques have been proposed to provide frequency support to the AC grid through the utilization of the frequency droop component in the AC droop control of MTDC networks [55,56,57].

Modern power electronic inverters paired with local energy storage can emulate several grid-support functions—such as providing synthetic inertia—and can operate in GFM mode. In GFM operation, the inverter establishes its own voltage and frequency reference, enabling autonomous synchronization even when the power system is de-energized, as occurs during a B.S. event. A persistent challenge with photovoltaic and wind resources is their dependence on inherently variable and uncontrollable natural inputs. Consequently, during system outages, the capability of PV and wind plants to assist in B.S. procedures is limited if weather conditions are not favorable. Integrating dedicated on-site energy storage mitigates this constraint by supplying the necessary power and stability support independent of resource availability.

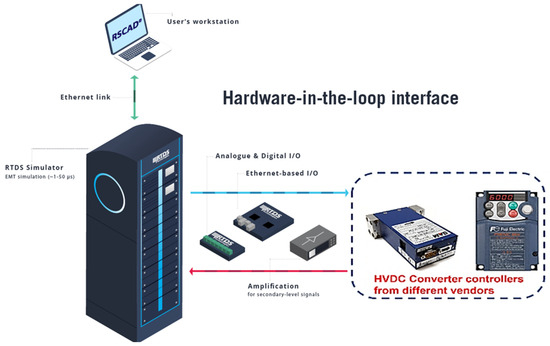

Given that large OSW networks may integrate converter, communication, and control equipment sourced from multiple vendors, interoperability becomes a critical design consideration. Ensuring that controllers from different manufacturers exchange data reliably and follow coordinated control actions is essential to prevent misoperation and communication failures. To verify cross-vendor compatibility and validate control performance, Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop (C-HIL) testing can be applied [58,59,60]. C-HIL involves connecting an actual controller—such as a commercial converter control unit—to a real-time digital simulator (e.g., RTDS or other HIL platforms). The real-time simulator reproduces the behavior of the surrounding power system, including network dynamics, converter responses, and environmental variations. The physical controller functions as it would in the field, processing real-time measurements (voltage, current, frequency) and issuing control commands back to the simulated system. This technique enables rigorous verification of control behavior without requiring full-scale power hardware.

Key advantages of the C-HIL methodology for validating converter control systems include:

- Interoperability Assessment—Ensures controllers from different vendors can operate in a coordinated and reliable manner.

- Control Performance Evaluation—Provides detailed insight into dynamic and steady-state response characteristics under realistic conditions.

- Safe Testing Environment—Allows fault scenarios and extreme operating conditions to be explored without risking physical equipment.

- Accelerated Development Cycle—Supports iterative testing and refinement of control algorithms early in the design process.

- Compliance and Certification Support—Facilitates verification of standards-based performance criteria prior to deployment.

In order to support vendor neutrality and interoperability, feedback from different HVDC converter vendors should be incorporated, with the possible utilization of software models of converters from these vendors. Another challenge that needs to be addressed is the requirement for high-fidelity, accurate models of HVDC converters and control schemes that are not readily available from the vendors. To resolve this challenge, the harmonic impedance spectrum-based technique in the C-HIL setup could be utilized to identify the dynamic black-box model of the converters [61]. For this purpose, controller hardware from multiple HVDC converter vendors could be utilized. The C-HIL setup for this purpose is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

C-HIL setup to identify the black-box model of OWF HVDC converter controllers.

The robust performance of the controller could be evaluated utilizing different system studies, including power flow, stability, control interaction, and fault behavior modeling, which could be done in the phasor domain and EMT domain utilizing hybrid simulation tools. In addition, hybrid Power Hardware-in-the-Loop (P-HIL) emulation involving real-time systems with actual hardware converter valves could improve module validation, leading to faster development cycles.

5. Communication

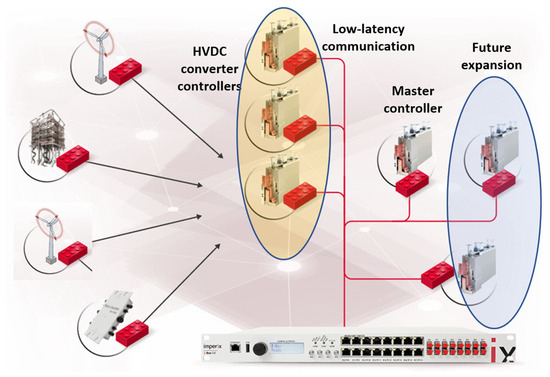

A centralized supervisory controller is essential for coordinating all converter terminals participating in OSW power transmission. Reliable operation of an offshore HVDC grid depends heavily on fast, high-integrity communication, since reference setpoints and control updates must be delivered from the supervisory controller to the individual converter station controllers with very low latency. This requirement can be met by adopting high-speed industrial communication technologies—such as EtherCAT, PESnet, SyCCo, or RealSync—that support deterministic, real-time data exchange.

The supervisory controller plays a pivotal role in maintaining grid stability across all operating conditions by issuing the necessary control commands. Its responsibilities cover both fast dynamic response functions and slower steady-state optimization tasks:

Dynamic control requirements (~40 µs timescale)

- Detecting and responding to fault conditions using appropriate protection and control actions

- Modifying converter controls to counter rapid deviations in voltage or frequency, thereby preventing cascading outages

Steady-state control requirements (tens of milliseconds)

- Managing operational settings, including tuning converter droop coefficients to influence power-flow distribution

- Regulating power injection from offshore wind plants

- Overseeing transmission loading, managing congestion, and optimizing power routing through the offshore network

A conceptual model illustrating the communication architecture between the supervisory (master) controller and the local HVDC converter controllers for offshore wind integration is presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Communication diagram between the central offshore grid controller and individual OSW farms’ converter controllers.

The EU-funded InterOPERA project specifically addresses the interoperability of multi-vendor HVDC systems, including communication aspects, due to its significance towards seamless MTDC network operations [62]. This project is aimed at developing common functional specifications and standardized interfaces that define how components from different vendors should interact. The project also aims to develop real-time demonstrators for testing the communication and operation of multi-vendor HVDC systems.

6. Conclusions

The OSW grid could provide multiple advanced grid-support features (harmonic filtering, frequency response, power-flow control, and voltage regulation) due to the utilization of advanced converter controllers. This paper identifies and reviews key bottlenecks, from a protection, control, and communication perspective, facing MTDC technology integration for OSW power transfer to the onshore grid, and proposes a way forward to tackling these challenges that prioritizes communication and leverages large-scale HIL testing capabilities. Full-scale, full-functionality technology demonstrators are essential for the development and evaluation of HVDC grid control, communication, protection systems, and associated equipment, including DCCBs and GIS technology. Additionally, pilot projects are critical for validation, ensuring safety, workforce training, and building stakeholder confidence in emerging meshed offshore grid control and protection technologies.

For a developing landscape of more OSW power integration, the TSOs have a major role to play in the integration of offshore HVDC networks with onshore grid as they set the voltage and frequency requirements, FRT behavior, reactive power (Q) requirements, allocate B.S. and restoration responsibilities. This involves robust coordination for power dispatch, congestion management, and AC/DC grid stability by incorporating services provided by converter stations (synthetic inertia, fast frequency response, voltage support). One of the largest obstacles facing TSOs is multi-vendor interoperability due to the involvement of different control algorithms, protection philosophies, and DC-voltage droop implementations and incompatible communication protocols. To fully realize the benefits of OSW energy potential, coordinated planning of both generation and transmission infrastructure is imperative. This requires active collaboration among all stakeholders—including electric utilities, regulators, energy agencies, TSOs, and research institutions—to develop cohesive policies and strategies that support integrated OSW development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and J.H.E.; methodology, M.N., J.H.E., J.M. and E.H.; formal analysis, M.N., J.H.E. and J.M.; investigation, M.N. and J.H.E.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.N., J.H.E., J.M. and E.H.; visualization, M.N. and E.H.; supervision, M.N. and J.H.E.; project administration, E.H.; funding acquisition, E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Offshore Wind Research & Development Consortium (NOWRDC), primarily funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). This document was prepared in connection with activities carried out under Award No. 165438-110 DE-EE0008390.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GFL | Grid following |

| GFM | Grid forming |

| GIS | Gas-insulated switchgear |

| HVDC | High-voltage direct current |

| MMC | Modular multi-level converter |

| MTDC | Multi-terminal high-voltage direct current |

| OSW | Offshore wind |

| POIs | Points of interconnections |

| PtP | Point-to-point |

| VSC | Voltage source converter |

| TSOs | Transmission system operators |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison among different offshore-onshore grid interfacing strategies.

Table A1.

Comparison among different offshore-onshore grid interfacing strategies.

| Approach/Technology | Main Advantages | Main Limitations | Maturity Level | Suitability for Large-Scale Offshore Networks | Control Strategy | Protection Approach | Black-Start Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point-to-Point VSC HVDC | Proven technology; flexible power flow | Limited scalability; no meshed operation | High (commercially deployed) | Suitable for single wind farm connections; less optimal for multi-terminal networks | Onshore DC voltage control; offshore P-control | Standard line protection; converter-based DC protection | Limited; relies on onshore AC for DC voltage |

| Multi-Terminal HVDC (MTDC) | Supports meshed networks; enables power sharing; redundancy potential | Complex control and protection; interoperability challenges | Medium (demonstration & pilot projects) | Promising for large-scale hubs; needs standardization for multi-vendor systems | Coordinated DC voltage control or droop; offshore P-control | Multi-terminal DC protection; requires communication & coordination | Possible if at least one GFM converter is available offshore/onshore |

| Offshore Grid-Forming VSC | Black-start capable; stabilizes offshore AC microgrid; supports weak grids | Requires auxiliary power or storage; not widely deployed yet | Low-Medium (R&D and simulations) | Suitable for black-start and weak offshore grids; can be integrated in MTDC networks | Grid-forming AC/DC voltage; onshore P-control | Standard VSC protection; may require local DC breakers | High; can energize DC link and offshore AC microgrid independently |

References

- Milano, F.; Dörfler, F.; Hug, G.; Hill, D.J.; Verbič, G. Foundations and challenges of low-inertia systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 Power Systems Computation Conference (PSCC), Dublin, Ireland, 11–15 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hatziargyriou, N.; Milanovic, J.; Rahmann, C.; Ajjarapu, V.; Canizares, C.; Erlich, I.; Hill, D.; Hiskens, I.; Kamwa, I.; Pal, B.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability revisited & extended. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 3271–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, A.; Normandia Lourenço, L.F.; Munkhchuluun, E.; Meegahapola, L.; Sguarezi Filho, A.J. Grid-Connected Power Converters: An Overview of Control Strategies for Renewable Energy. Energies 2022, 15, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.M.; Munda, J.L.; Hamam, Y. Power system flexibility: A review. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Mathuria, P.; Bhakar, R.; Mathur, J.; Kanudia, A.; Singh, A. Flexibility requirement for large-scale renewable energy integration in Indian power system: Technology, policy and modeling options. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 29, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.M.A. Multi-Terminal Hvdc Grids: Control Strategies for Ancillary Services Provision in Interconnected Transmission Systems with Offshore Wind Farms. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Normandia Lourenço, L.F.; Louni, A.; Damm, G.; Netto, M.; Drissi-Habti, M.; Grillo, S.; Sguarezi Filho, A.J.; Meegahapola, L. A Review on Multi-Terminal High Voltage Direct Current Networks for Wind Power Integration. Energies 2022, 15, 9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ravishankar, J.; Fletcher, J.; Li, R.; Han, M. Review of modular multilevel converter based multi-terminal HVDC systems for offshore wind power transmission. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.D.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Control of multi-terminal HVDC networks towards wind power integration: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, E.; Leforgeais, B. Selection of Power From Shore for an Offshore Oil and Gas Development. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldsund, M.; Reyes-Lúa, A.; Fu, C.; Ditaranto, M.; Nekså, P.; Mazzetti, M.J.; Brekke, O.; Bindingsbø, A.U.; Grainger, D.; Pettersen, J. Low carbon power generation for offshore oil and gas production. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 17, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.; Ergun, H.; Van Hertem, D. Incorporating DC grid protection, frequency stability and reliability into offshore DC grid planning. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 2772–2781. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, B. The offshore grid: The future of america’s offshore wind energy potential. Ecol. LQ 2015, 42, 651. [Google Scholar]

- Tuinema, B.W.; Getreuer, R.E.; Rueda Torres, J.L.; van der Meijden, M.A. Reliability analysis of offshore grids—An overview of recent research. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2019, 8, e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, J.A.; Liu, C.; Khan, S.A. MMC based MTDC grids: A detailed review on issues and challenges for operation, control and protection schemes. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 168154–168165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, H.; Guvenc, U.; Duman, S.; Kahraman, H.T. Optimal power flow for hybrid AC/DC electrical networks configured with VSC-MTDC transmission lines and renewable energy sources. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 3938–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangwa, N.M.; Venugopal, C.; Davidson, I.E. A review of the performance of VSC-HVDC and MTDC systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES PowerAfrica, Accra, Ghana, 27–30 June 2017; pp. 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifenberger, J.; Tsoukalis, J.; Newell, S.A. The Benefit and Cost of Preserving the Option to Create a Meshed Offshore Grid for New York; Technical Report; Brattle Group, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, C.M. HVDC circuit breakers: A review identifying future research needs. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2011, 26, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhberdoran, A.; Carvalho, A.; Leite, H.; Silva, N. A review on HVDC circuit breakers. In Proceedings of the 3rd Renewable Power Generation Conference (RPG 2014), Naples, Italy, 24–25 September 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rouzbehi, K.; Hajian, M.; Niayesh, K.; Gharehpetian, G.B.; Saad, H.; Ali, M.H.; Sood, V.K. HVDC circuit breakers: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 13726–13739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Mustafa, A.; Alqasemi, U.; Rouzbehi, K.; Muzzammel, R.; Guobing, S.; Abbas, G. HVdc circuit breakers: Prospects and challenges. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, S.M.; Ozansoy, C. The role of communications and standardization in wind power applications—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirnivas, S.; Musial, W.; Bailey, B.; Filippelli, M. Assessment of Offshore Wind System Design, Safety, and Operation Standards; No. NREL/TP-5000-60573; National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dolores Esteban, M.; López-Gutiérrez, J.S.; Negro, V.; Matutano, C.; García-Flores, F.M.; Millán, M.Á. Offshore wind foundation design: Some key issues. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2015, 137, 051211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrozaite, O.; Torabi, C.; Van Damme, N.; Velez, D.; Wallemacq, M. Standardization of Turbine Design and Installation Vessels to Accelerate the Offshore Wind Industry in the United States. J. Sci. Policy Gov. 2024, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.K.; Torbaghan, S.S.; Gibescu, M.; Roggenkamp, M.M.; Van Der Meijden, M.A.M.M. The need for a common standard for voltage levels of HVDC VSC technology. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, P.; Marshall, B.; Kahlen, C. Deliverable 11.5 Best Practice and Recommendations for Compliance Evaluation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: http://www.promotion-offshore.net/fileadmin/PDFs/D11.5_Best_practice_and_recommendations_for_compliance_evaluation-final.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Dragon, J.; Beites, L.F.; Callavik, M.; Eichhoff, D.; Hanson, J.; Marten, A.K.; Morales, A.; Sanz, S.; Schettler, F.; Westermann, D.; et al. Development of functional specifications for HVDC grid systems. In Proceedings of the 11th IET International Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission, Birmingham, UK, 10–12 February 2015; IET: Stevenage, UK, 2015; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Akhmatov, V.; Callavik, M.; Franck, C.; Rye, S.E.; Ahndorf, T.; Bucher, M.K.; Müller, H.; Schettler, F.; Wiget, R. Technical guidelines and prestandardization work for first HVDC grids. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2013, 29, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.A.; Hooshyar, A. Controlling grid-forming inverters to meet the negative-sequence current requirements of the IEEE Standard 2800-2022. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 2541–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.W.; Patel, M.; Haddadi, A.; Farantatos, E.; Boemer, J.C. Inverter current limit logic based on the IEEE 2800-2022 unbalanced fault response requirements. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 July 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, M.; Enslin, J.H.; Hines, E.; McCalley, J.D.; Lof, P.A.; Garnick, B.K. Multi-terminal HVDC grid topology for large scale integration of offshore wind on the US Atlantic Coast. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th IEEE Workshop on the Electronic Grid (eGRID), Auckland, New Zealand, 29 November–2 December 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Next Generation Offshore Grid Connection Systems: TenneT’s 2 GW Standard. Available online: https://electra.cigre.org/321-april-2022/technology-e2e/next-generation-offshore-grid-connection-systems-tennets-2-gw-standard.html (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Progress on Meshed HVDC Offshore Transmission Networks (PROMOTioN). Available online: https://www.promotion-offshore.net (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- PROMOTioN Final Deployment Plan (D12.4). Available online: http://www.promotion-offshore.net/fileadmin/PDFs/D12.4_-_Final_Deployment_Plan.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Li, G.; Liang, J.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Joseph, T.; Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Jose, K.F. Frontiers of DC circuit breakers in HVDC and MVDC systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Beijing, China, 26–28 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tahata, K.; El Oukaili, S.; Kamei, K.; Yoshida, D.; Kono, Y.; Yamamoto, R.; Ito, H. HVDC circuit breakers for HVDC grid applications. In Proceedings of the 11th IET International Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission, Birmingham, UK, 10–12 February 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Taherzadeh, E.; Radmanesh, H.; Javadi, S.; Gharehpetian, G.B. Circuit breakers in HVDC systems: State-of-the-art review and future trends. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2023, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Adeuyi, O.D.; Li, G.; Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Liang, J. Coordination of MMCs with hybrid DC circuit breakers for HVDC grid protection. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2018, 34, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Wei, X. Research on key technology and equipment for Zhangbei 500kV DC grid. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC-Niigata 2018-ECCE Asia), Niigata, Japan, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 2343–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, Q.; Yang, R. Research on demonstration project of Zhangbei flexible DC grid. In Proceedings of the 2020 10th International Conference on Power and Energy Systems (ICPES), Chengdu, China, 25–27 December 2020; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Molina, M.J.; Eguia, P.; Larruskain, D.M.; Torres, E.; Abarrategi, O.; Sarmiento-Vintimilla, J.C. Single-ended limiting inductor voltage-ratio-derivative protection scheme for VSC-HVDC grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 147, 108903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disruptive DC Converters for Grid Resilient Infrastructure to Deliver Sustainable Energy. Available online: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/programs-and-initiatives/view-all-programs/dc-grids (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- East Coast Offshore Wind Transmission. Available online: https://nationaloffshorewind.org/wp-content/uploads/Brochure-East-Coast-Offshore-Wind-Transmission.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Offshore Wind Transmission Expansion Planning for the U.S. Atlantic Coast. Available online: https://offshorewind.tufts.edu/ospre-reports (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Garg, L.; Prasad, S. A review on controller scalability for VSC-MTDC grids: Challenges and applications. Smart Sci. 2023, 11, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakosyan, A.; Ameli, A.; El-Fouly, T.H.; El Moursi, M.S.; Salama, M.M.; El-Saadany, E.F. A novel control technique for enhancing the operation of MTDC grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irnawan, R. Planning and Control of Expandable Multi-Terminal VSC-HVDC Transmission Systems; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Pei, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. An improved master-slave control strategy for automatic DC voltage control under the master station failure in MTDC system. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 11, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Fu, Q.; Wang, H. Damping torque analysis of DC voltage stability of an MTDC network for the wind power delivery. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2019, 35, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzbehi, K.; Miranian, A.; Luna, A.; Rodriguez, P. DC voltage control and power sharing in multiterminal DC grids based on optimal DC power flow and voltage-droop strategy. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2014, 2, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzbehi, K.; Miranian, A.; Candela, J.I.; Luna, A.; Rodriguez, P. A generalized voltage droop strategy for control of multiterminal DC grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2014, 51, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañas Ramos, J.; Moritz, M.; Klötzl, N.; Nieuwenhout, C.; Leon Garcia, W.; Jahn, I.; Kolichev, D.; Monti, A. Getting ready for multi-vendor and multi-terminal HVDC technology. Energies 2024, 17, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadabi, H.; Kamwa, I. Dual adaptive nonlinear droop control of VSC-MTDC system for improved transient stability and provision of primary frequency support. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 76806–76815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Häger, U.; Rehtanz, C. Adaptive droop control of VSC-MTDC system for frequency support and power sharing. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, B.; El Moursi, M.S.; El-Saadany, E.F. Primary frequency support strategy for MTDC system with enhanced DC voltage response. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 1512–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseh, M.B.; Colak, A.M.; Inzunza, R.; Ambo, T. Active anti-islanding technique using C-HIL real time simulation. In Proceedings of the 2020 9th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Application (ICRERA), Online, 27–30 September 2020; pp. 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Antonin, C.; Bastien, E.; Mevludin, G.; Bertrand, C. A C-HIL based data-driven DC-DC power electronics converter model for system-level studies. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE), Grenoble, France, 23–26 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya, S.; Binod, S.; Srivastava, A.; Baluni, A.; Poddar, S.; Mathew, L. Controller Hardware in Loop Simulation (C-HIL) for Grid-Connected Photovoltaic System. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Smart Technologies for Power, Energy and Control (STPEC), Bilaspur, India, 19–22 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, B.; Louarroudi, E.; Bragos, R.; Pintelon, R. Harmonic impedance spectra identification from time-varying bioimpedance: Theory and validation. Physiol. Meas. 2013, 34, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InterOPERA: Enabling Multi-Vendor HVDC Grids. Available online: https://interopera.eu/objectives/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).