There was an error in the original publication [1]. It is related to the arithmetic calculation of the Weber number. Considering this error, the values of the Weber number were corrected throughout the manuscript. In addition, Figures 7b and 8a were replaced with the updated ones, because the X-axis of these figures contains the Weber number values. Following the data in Figure 8a, the empirical expression derived was changed from βmax = 0.45We0.4 to βmax = 0.97We0.2.

A correction has been made to the Abstract:

Abstract: The effect of coal hydrophilic particles in water–glycerol drops on the maximum diameter of spreading along a hydrophobic solid surface is experimentally studied by analyzing the velocity of internal flows by Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV). The grinding fineness of coal particles was 45–80 μm and 120–140 μm; their concentration was 0.06 wt.% and 1 wt.%. The impact of particle-laden drops on a solid surface occurred at Weber numbers (We) from 20 to 250. We reveal the interrelated influence of We and the concentration of coal particles on changes in the maximum absolute velocity of internal flows in a drop within the kinetic and spreading phases of the drop-wall impact. We explore the behavior of internal convective flows in the longitudinal section of a drop parallel to the plane of the solid wall. The kinetic energy of translational motion of coal particles in a spreading drop compensates for the energy expended by the drop on sliding friction along the wall. At We = 250, the inertia-driven spreading of the particle-laden drop is mainly determined by the dynamics of the deformable Taylor rim. An increase in We contributes to more noticeable differences in the convection velocities in spreading drops. When the drop spreading diameter rises at the maximum velocity of internal flows, growth of the maximum spreading diameter occurs. The presence of coal particles causes a general tendency toward a reduction in drop spreading.

A correction has been made to the Materials section, Table 3:

Table 3.

Initial conditions for conducting experiments.

A correction has been made to the Results and Discussion section, the sub-section Effect of We and the concentration of coal particles on the velocity of internal flows in a spreading drop, paragraph 1:

The analysis of the results for the distributions of maximum velocities in the drop over the spreading time (Figure 5) revealed the interrelated effect of We and the concentration of coal particles on changes in the peak values of Umax in the kinetic and spreading phases. At We = 250, it is difficult to distinguish the effect of coal particles on the development of internal flows (Figure 5b,d), regardless of their grinding fineness and concentration. The radial motion of the drops occurs with the spreading velocity Uspr (Figure 5b,d), approximately twice as high as at We = 30 (Figure 5a,c). At such high values of Uspr (about 3.5 m/s), the inertia-driven spreading of the particle-laden drop is mainly determined by the dynamics of the Taylor rim, whose diameter becomes relatively smaller. Then, the rim begins to deform (Figure 6a,b) due to the Rayleigh–Taylor instability [32–34]. The contribution of solids is insignificant, so the values of Umax are quite close, while with We = 20 and a grinding fineness of 45–80 μm (Figure 5a), the addition of coal particles contributes to a rather significant increase in Umax. However, at a coal particle concentration of 0.06 wt.%, the values of Umax were significantly higher than at 1 wt.%. The relative decrease in Umax in the case of a higher concentration can be physically associated with the formation of the internal structure (Figure 6c) and, accordingly, an increase in shear stresses between the liquid layers during the drop spreading. The latter leads to the expenditure of more energy to move the liquid. At a lower concentration, solids, having more physical space between them, cannot form the structure, and therefore the particles can act as single “accelerators” in the velocity field, which achieve inertia-driven acceleration from the internal translational flow of the liquid (Figure 6d). When We = 20 and the particle grinding fineness is 120–140 μm (Figure 5c), then even in the case of a lower concentration, a certain effect of inhibition of internal flows is observed both in absolute values of Umax and in the spreading time t relative to the case without coal particles. This phenomenon is presumably caused by the immediate sedimentation of coal particles upon contact with the surface and their restraining disturbance of the laminar flow (Figure 6e). At 1 wt.%, the number of the particles of 120–140 μm in size becomes larger; they can not only restrain laminar flow but also mechanically deform the liquid–gas interface both on the free surface of the liquid and near the contact line after particle collisions (Figure 6f). The latter can lead to additional local liquid flows that affect the overall distribution of U over the spreading time (Figure 5c). A remarkable thing happened for the drops of Slurry 4, which characterizes the difficult-to-predict nature of particle motion. In particular, coal particles were often grouped in a rather limited area of the radially moving flow. In this case, most of the spreading particle-laden drop contained almost no coal particles.

A correction has been made to the Results and Discussion section, the sub-section of Effect of We and the concentration of coal particles on the velocity of internal flows in a spreading drop, the caption of Figure 5:

Figure 5. Effect of the Weber number and the concentration of coal particles on the distributions of the instantaneous maximum velocity of fluorescent microparticles in a drop over the spreading time: (a) grinding fineness of coal particles 45–80 μm, We = 20; (b) 45–80 μm, We = 250; (c) 120–140 μm, We = 30; (d) 120–140 μm, We = 250. The confidence intervals for the experimental data were no more than 3.3%.

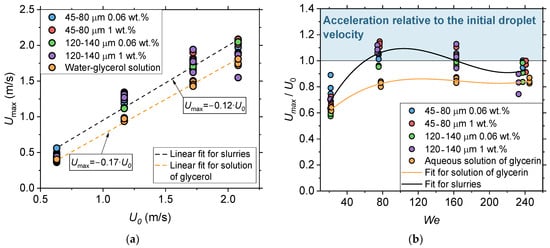

A correction has been made to the Results and Discussion section, the sub-section of Effect of We and the concentration of coal particles on the velocity of internal flows in a spreading drop, Figure 7b:

Figure 7.

Maximum absolute velocities of internal flows in a drop Umax as a function of the initial velocity of the drop before impact U0 (a), parameter Umax/U0 as a function of We (b).

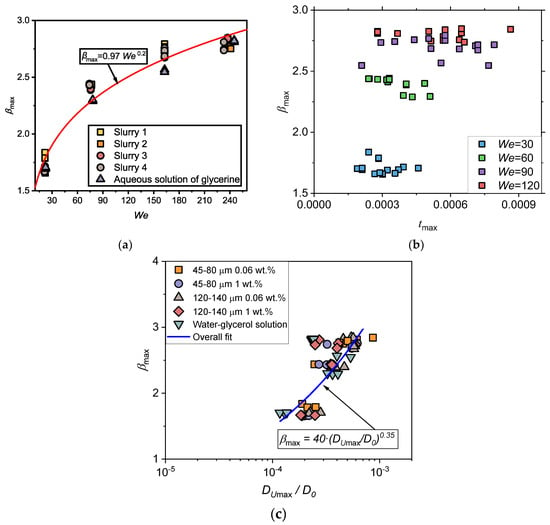

A correction has been made to the Results and Discussion section, the sub-section of Weber number factor, paragraph 1:

In the previous subsection, it was shown that coal particles in a spreading drop can affect the internal flow velocities. If the velocity of internal flows in the drop increases, this should affect the spreading characteristics, in particular, the spreading diameter. Therefore, one of the key tasks of the study was to establish an implicit relationship between the velocity of internal flows in the longitudinal section of the drop and the factor of its maximum spreading βmax. To test this relationship, it was necessary to make sure that for all the liquids under study, the behavior of βmax is mainly determined by the initial drop velocity with the constancy of other terms within We. This confidence was achieved after summarizing the results in the framework of the relationship βmax = f(We) depicted in Figure 8a. The behavior of βmax for particle-laden and water–glycerol drops is governed by the power function of βmax = 0.97We0.2 with R2 = 0.95.

A correction has been made to the Results and Discussion section, the sub-section of Weber number factor, Figure 8a, and its caption:

Figure 8.

Maximum spreading factor βmax and time to reach the maximum spreading diameter tmax for the considered liquids at We = 20, 80, 160, and 250 (a); values of βmax as a function of We (b); values of βmax as a function of the dimensionless diameter of the spreading drop at the maximum velocity of internal flows DUmax/D0 (c).

A correction has been made to the Conclusions section, paragraphs 2 and 3:

- At We = 20, the particle grinding fineness and concentration strongly affect the internal flow velocities, contributing both to their increase and decrease, depending on the combination of the initial parameters of a slurry. At We = 250, the spreading velocity of the particle-laden drops is approximately twice as high as at We = 20. Given this fact, the inertia-driven spreading of the particle-laden drop is mainly determined by the dynamics of the deformable Taylor rim, and the contribution of solids is insignificant, causing the closeness of the values of the maximum absolute velocity of internal flows for various combinations of the initial parameters of a slurry. Relying on the experimental data obtained by the shadow photography and PIV, the behavior of internal convective flows in the longitudinal section of a particle-laden drop is characterized. It is revealed that the kinetic energy of translational motion of coal particles in a drop compensates for the energy expended by the drop on sliding friction along the wall.

- The behavior of the maximum spreading factor βmax for particle-laden and water–glycerol drops is mainly defined by the initial drop velocity with the constancy of other terms within the Weber number and is governed by the power function of βmax = 0.97We0.2 with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.95. Further, we revealed the peculiarity of a noticeable increase in the differences in the velocities of internal flows in spreading drops with an increase in Weber number. Finally, as the Weber number grows, an increase in the spreading drop diameter at the maximum absolute velocity of internal flows causes elevated values for the maximum spreading diameter and is described by the expression . In addition, the presence of coal particles causes a general tendency toward a reduction in liquid drop spreading.

The authors state that the scientific conclusions are unaffected. This correction was approved by the Academic Editor. The original publication has also been updated.

Reference

- Ashikhmin, A.; Khomutov, N.; Volkov, R.; Piskunov, M.; Strizhak, P. Effect of Monodisperse Coal Particles on the Maximum Drop Spreading After Impact on a Solid Wall. Energies 2023, 16, 5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).