Abstract

As the global energy demand continues to grow and the pursuit of clean and sustainable resources intensifies, nuclear energy stands out as a secure, reliable, and low-emission solution. The complexity of nuclear power plant behavior under various operating conditions necessitates advanced simulation tools capable of capturing the interplay between multiple physical phenomena. Among these, multi-physics coupling, particularly between neutronics and thermal hydraulics, is a well-established approach for accurately modeling transient scenarios with strong feedback effects. In this context, PARCS and TRACE codes, developed by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, are widely used for coupled neutronic/thermal-hydraulic analyses and can be operated via the SNAP graphical interface. However, the current version of SNAP does not support automatic coupling for hexagonal core geometries, such as those found in VVER-type reactors. To address this limitation, a dedicated tool was developed to facilitate the coupling process between PARCS and TRACE for hexagonal cores. The proposed methodology was tested through the simulation of a rod ejection accident in a VVER-1000 reactor, demonstrating the validity of the methodology and confirming that the multi-physics approach provides more accurate, best-estimate results.

1. Introduction

By 2050, the International Energy Agency (IEA) envisions a Net Zero world where nuclear power stands out as a secure, reliable, and low-emission solution to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and address climate change [1]. Rising to this challenge, the nuclear industry is undergoing a transformation, embracing innovation to improve performance, sustainability, and, above all, safety. As public safety remains paramount, one of the sector’s top priorities is to ensure that both existing and next-generation reactor technologies meet the highest safety standards under all operating conditions.

To this end, computer codes play a crucial role in supporting safety assessments for Nuclear Power Plants (NPPs), and ongoing advancements in computer technology and computational methods have significantly enhanced their capabilities. Currently, a key trend is to couple existing codes that simulate different physical phenomena to achieve more accurate simulations of the complex events and transients occurring in NPPs [2]. One of the most widespread coupling techniques is between system thermal-hydraulic and reactor kinetics codes. The main advantage is that it accounts for the feedback effects of thermal hydraulics on neutron kinetics, enabling a more accurate treatment of power and flux distribution during non-symmetric power generation and uneven core cooling. Examples of transients where this type of coupling is particularly useful include almost all reactivity-initiated accidents, such as Rod Ejection Accidents (REA), boron dilution accidents, anticipated transients without scram, and main steam line break scenarios [3].

This study is based on the coupling between TRAC/RELAP Advanced Computational Engine (TRACE) [4] and the Purdue Advanced Reactor Core Simulator (PARCS) [5]. TRACE is a reactor thermohydraulic system code, while PARCS is a multidimensional reactor kinetics code.

Both codes can be used through the SNAP graphical interface [6]; however, SNAP lacks an automatic mapping function for hexagonal core geometries, and this requires additional effort in modeling the coupled system. The groundwork for PARCS/TRACE coupling in VVER-1000 reactors was previously established in the Czech Republic [7,8]; however, with recent advancements in these codes and their models, a revision of the previously developed methodology became necessary. Specifically, there was a need to refine the mapping procedure for the updated models, verify the coupling requirements, and develop tools to support the procedure. A substantial part of the methodology development was carried out and documented as part of a master’s thesis [9], which served as the basis for the advancements presented in this study.

To run coupled simulations, an external mapping file is required to link the respective codes’ geometries and enable them to exchange information through the transient. The developed methodology facilitates the process of generating this mapping file employing Python3 scripts. The validity of these scripts was tested through the simulation of a REA scenario for the VVER-1000 [10,11], whose specific requirements were included in the coupling methodology as well.

The results presented in this paper are preliminary and serve as an example of how to perform external coupling between the two codes, potentially laying the foundation for an automatic mapping function implementation within SNAP. Nonetheless, the REA analysis shows that the coupling leads to a more accurate evaluation of the feedback effects, confirming that the methodology is both valid and applicable to various hexagonal core models.

2. Materials and Methods

This chapter describes the computational tools and methodologies adopted in this study to simulate the behavior of a VVER-1000 reactor, a Russian-designed pressurized water reactor (PWR) widely deployed in Eastern Europe. The reactor model serves as the basis for evaluating the coupled neutronic and thermal-hydraulic response under transient conditions.

The analysis employs two advanced simulation codes developed and maintained by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC): TRACE, a best-estimate thermal-hydraulic system code, and PARCS, a multidimensional reactor kinetics code. While each code can operate independently, their coupled application allows for high-fidelity simulation of complex transients involving strong neutronic–thermal-hydraulic interactions, such as reactivity insertion events. Both tools are distributed through the Code Applications and Maintenance Program, of which the Czech Republic is an active member [12].

The following sections provide a technical overview of the reference reactor model, the key features of TRACE and PARCS, and the details of their coupling methodology.

2.1. Overview of the VVER-1000 Reactor

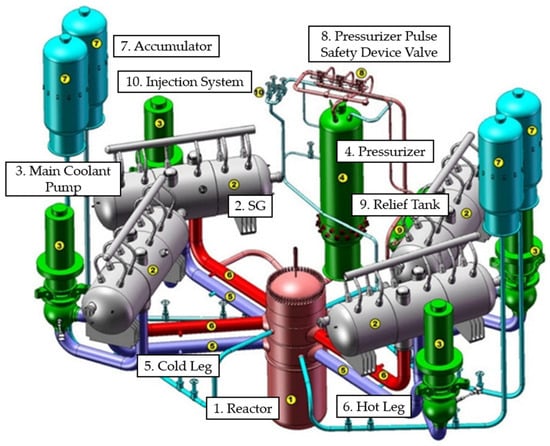

The analysis performed in this study focuses on a generic VVER-1000/V-320 reactor, originally developed by OKB Gidropress (Podolsk, Russia). The reactor’s basic layout and main technical parameters are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively. The VVER-1000 has a thermal output of 3000 MW and is distinguished from Western PWRs primarily by its hexagonal core geometry and the use of horizontal-axis steam generators. The reactor cooling system consists of four main circulation loops, each comprising a reactor coolant pump, a steam generator (SG), a hot leg and a cold leg. The primary circuit is connected to a pressurizer via a surge line and an injection line, each one located on a different hot leg. Core cooling under loss-of-coolant accidents is provided by the Emergency Core Cooling System (ECCS) with high and low-pressure pumps and hydro-accumulators [11].

Figure 1.

Primary Circuit of VVER-1000 plant, adapted from [13].

Table 1.

VVER-1000 V-320 technical parameters, adapted from [11].

2.2. TRACE

The TRAC/RELAP Advanced Computational Engine, formerly known as TRAC-M, represents the latest development in a series of advanced reactor systems codes. Developed by the U.S. NRC, these codes are intended to analyze both transient and steady-state neutronic and thermal-hydraulic behaviors in light water reactors. TRACE is the result of a long-term effort to integrate the functionalities of the NRC’s four major systems codes (TRAC-P, TRAC-B, RELAP5, and RAMONA) into a single, modernized computational tool. It can model components such as the reactor pressure vessel, steam generator, and loop systems, enabling 3D heat-transfer analyses in both primary and secondary circuits [4]. The specific version used in these analyses is TRACE v5, patch 8, released in 2023.

2.3. PARCS

The Purdue Reactor Core Simulator is a three-dimensional (3D) reactor core simulator designed to solve both steady-state and time-dependent multi-group neutron diffusion or low-order neutron transport equations in Cartesian and hexagonal fuel geometries. The primary objective of PARCS modeling is to create an accurate, though approximate, numerical representation of the physical reactor system. Key modeling components in reactor kinetics calculations include the core geometric representation, the cross-section library input, and thermal-hydraulic (T/H) feedback modeling. PARCS offers a 3D geometric representation, which can be simplified to 2D, 1D, or 0D (point kinetics) by selecting appropriate boundary conditions [5]. All simulations in this work were performed using PARCS v3.4.2, released in 2022.

2.4. Coupling PARCS/TRACE

The coupling of PARCS and TRACE codes is implemented through the so-called “segregated approach”, a well-established technique that relies either on a programmed interface (SNAP) or on an external file for data exchange. This approach enables an a posteriori coupling of mono-physics solvers without the need to re-verify and re-validate them.

To set up such coupled calculations, a “spatial coupling” or “mapping” is required [2]. This procedure consists of linking the neutronic nodes in PARCS (fuel assemblies and reflectors) with the thermal-hydraulic nodes in TRACE, both axially and radially. The codes will then exchange various types of information to enable integrated calculations:

- TRACE computes coolant and fuel properties (e.g., moderator temperature, liquid/vapor density, void fraction, boron concentration, centerline and surface temperature of heat structures). These calculations are based on the power distribution provided by PARCS, which serves as the heat source for heat conduction [4].

- PARCS updates macroscopic cross-section data using the local conditions of the coolant and fuel, as received from TRACE. PARCS then calculates the 3D neutron flux and sends the resulting node-wise power distribution back to TRACE.

For each link between the neutronic and the T/H volumes, “coupling coefficients” or “weighting factors” must be specified. These factors are required to match the different nodalizations of the two models and are evaluated from geometrical considerations, as further explained in the following chapters.

The coupling of TRACE and PARCS for VVER-1000 purposes was verified and validated against the OECD NEA benchmark exercises [14]. Specifically, both Ivanov et al. [15] and Jaegar et al. [16] performed the validation for Exercise 1 and 2 of the VVER Coolant Transient Benchmark Phase 2, demonstrating the validity of using both codes for transient analyses of VVER reactors.

3. Models and Methodology

The following sections provide a description of the neutronic and thermohydraulic models developed for this reactor, followed by an outline of the coupling methodology and the relative tools.

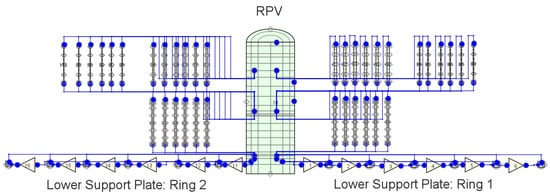

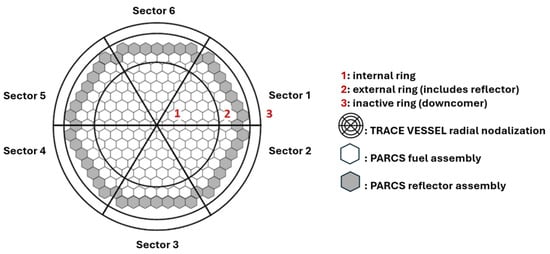

3.1. TRACE Model

The VVER-1000 model was initially developed for the RELAP5/Mod3.3 code and subsequently converted to TRACE v5.8. This model includes both the primary and secondary systems of the plant, as well as its safety systems. The primary system model begins with the Reactor Pressure Vessel (RPV), represented by TRACE’s 3D VESSEL component, which is shown in Figure 2. The vessel is divided radially into three zones: the two inner zones represent the lower plenum, core, and upper plenum, while the third outer zone models the downcomer. Axially, the original model consists of 9 meshes representing the active core, though a variant with 40 axial meshes was also created to achieve a 1:1 alignment with the PARCS model. Azimuthally, the vessel is divided into six 60-degree sectors. Figure 3 provides the details of the axial and sextant mesh distributions.

Figure 2.

RPV model in TRACE.

Figure 3.

Loop radial distribution and fuel nodalization in TRACE models.

The primary circuit model comprises various loops representing different primary system components. These include hot leg pipes, horizontal steam generators, hot and cold collectors, heat exchange tube bundles, loop seal pipes, reactor coolant pumps, and cold legs. The pressurizer, together with its surge and spray lines, is also modeled, including the power-operated relief valve and safety valves. TRACE v5.8 also models the secondary system’s steam lines up to the turbine, with steam dump valves and steam generator safety valves being individually simulated. The feedwater system model incorporates pipes and valves located within containment. Additionally, control components and trip functions are included to simulate safety-grade actions of the instrumentation and control systems.

Finally, the model includes the ECCS with High- and Low-Pressure injection systems and accumulators, allowing for the simulation of Large Break, Medium Break, and Small Break Loss of Coolant Accidents (SBLOCA).

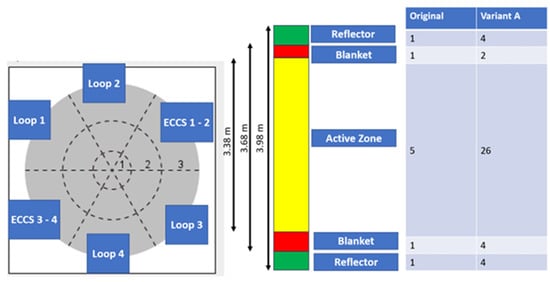

3.2. PARCS Model

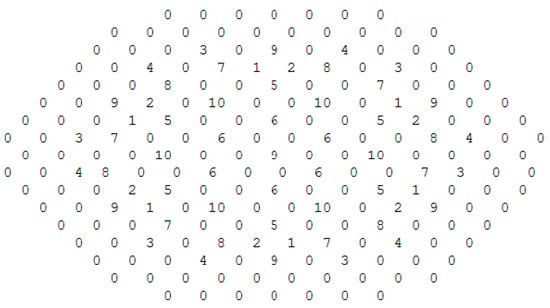

The neutronic model of the VVER-1000 in the PARCS code is developed using various “cards,” each containing specific neutronic definitions. These include, most notably, the cross-sections for fuel assemblies and reflectors, which are generated by an external code (in this case, SCALE), the core layout, and the radial and axial mesh structures. For successful coupling, the geometrical configuration must align with the TRACE model, although the nodalization may differ. The reactor model is divided into 8 radial rings, with 7 rings representing the fuel assemblies and 1 peripheral ring for the reflector, as shown in Figure 4, where each numerical node represents an assembly. Each element consists of 40 axial nodes:

Figure 4.

Radial nodalization of the reactor core in PARCS.

- 26 nodes of 13 cm for the fuel active length;

- 4 nodes of 5 cm for the bottom blanket pins;

- 2 nodes of 5 cm for the top blanket pins;

- 4 nodes of 3.75 cm for the bottom reflector region;

- 4 nodes of 3.75 cm for the top reflector region;

- 40 nodes (with the same dimensions) for the radial reflector.

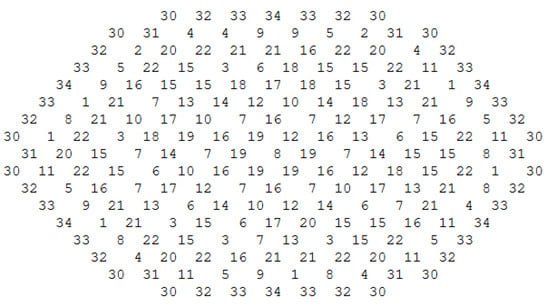

Along with the radial assembly configuration, it is also necessary to set up the control rods configuration. Figure 5 shows their location in the reactor core.

Figure 5.

Position of control rods in the reactor core.

3.3. Coupling Methodology

To enable the exchange of information between the two codes, as explained in Section 2.4, an interface file called MAPTAB containing all mapping information is required. For square-pitch reactor models, MAPTAB is automatically generated by the SNAP interface when coupling PARCS and TRACE. However, for triangular-pitch configurations, characteristic of hexagonal geometries, this process is not automated and must be performed manually.

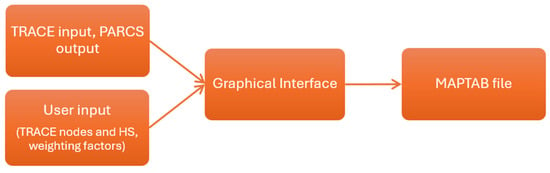

Due to the complexity and limitations of manual mapping, two Python scripts were developed to simplify and standardize the procedure. The first script, referred to as the core script, produces the mapping file almost entirely automatically. The second script provides a graphical interface, relying on the core script but requiring more user interaction. These tools significantly streamline the coupling process and support various hexagonal configurations, enabling easier integration between PARCS and TRACE.

This work focuses on coupling the TRACE 3D VESSEL component, although the feature is also provided for other components, such as pipes. As described in Section 3.1, the TRACE vessel is a cylindrical component divided into axial levels, azimuthal sectors, and radial rings, which together form a mesh-cell grid [17]. Conversely, the reactor core in PARCS is represented by Fuel Assemblies (FAs) arranged as numerical nodes in the radial plane, with additional nodes corresponding to the radial reflector. Because the TRACE vessel geometry does not precisely match the PARCS core nodalization, adjustments are required. Specifically, the number of PARCS nodes must be increased where the axial divisions of the TRACE vessel intersect the FAs.

An example of this discrepancy is illustrated in Figure 6, where the TRACE VESSEL component with the current work’s nodalization is overlaid on the respective PARCS map. The vessel is divided into six azimuthal sectors and two radial rings, excluding the outermost ring (corresponding to the downcomer). White hexagons represent the PARCS FAs, while gray hexagons denote the radial reflector.

Figure 6.

Example of radial nodalization of the RPV in TRACE and PARCS, adapted from [8].

Each node in the map is associated with a weighting factor. This factor quantifies the fraction of thermal-hydraulic feedback received by a neutronic node from its associated thermal-hydraulic cell or, conversely, the fraction of the total neutronic power deposited into the corresponding thermal-hydraulic cell. When a node is shared by many sectors, their weights must be reduced proportionally to maintain consistency with the original FA distribution. For instance, in the VVER-1000 model, nodes located between two azimuthal sectors are divided in two, each with a weight of 1/2. Similarly, the central node is split into six nodes, each with a weight of 1/6.

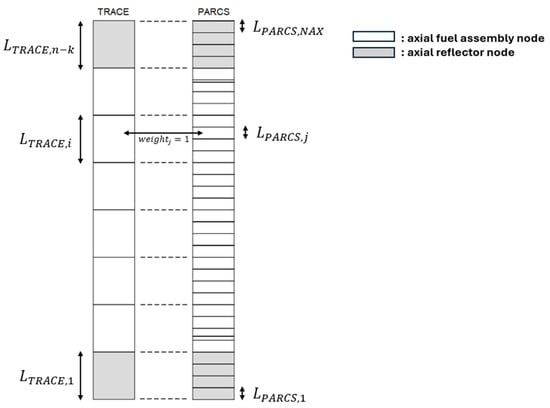

For axial meshing, TRACE typically divides the vessel into n nodes, with the core occupying only n − k nodes, where k corresponds to non-active levels (e.g., lower and upper plenum or other non-heat-structure regions). The heat structures in TRACE are numbered from 1 to n − k, whereas PARCS uses a numbering scheme from 1 to NAX, where NAX represents the number of neutronic axial levels. Ideally, the thermal-hydraulic and neutronic meshes should align closely to ensure consistent accuracy in both fields.

However, in practice, neutronic nodalization is often finer. In such cases, the meshes must be aligned side by side, as shown in Figure 7, to determine the overlap between nodes. If nodes align perfectly without overlapping, as in the case shown in figure, their weights are set to unity. If an overlap occurs, weights are adjusted proportionally to the fraction of the neutronic node’s length aligned with the thermal-hydraulic node. The sum of weights within each neutronic node must always equal unity.

Figure 7.

Example of axial mapping between TRACE and PARCS.

The developed scripts automate the creation of these mapping tables, apply the necessary logic for weights assignment, and organize the data into the MAPTAB file. This file consists of two tables:

- Mapping between hydrodynamic volumes and neutronic nodes.

- Mapping between heat structures and neutronic nodes.

Both tables share the same structure, with each row containing five values: vessel ID, TRACE radial ID, TRACE axial ID, PARCS node ID, and the product of radial and axial weights.

In addition to the mapping file, to couple PARCS and TRACE three more files are needed: the PARCS and TRACE inputs, and the TRACE Stand Alone (SA) restart file, which is generated by the SA TRACE. With these files, it is possible to run the Steady State (SS) Coupled (-C) calculation. This calculation produces several output files, including the restart files of both PARCS and TRACE, which are necessary for Transient (Tr) calculation. The SS-C restart files are then used for the Tr-C calculation along with the transient inputs of PARCS and TRACE.

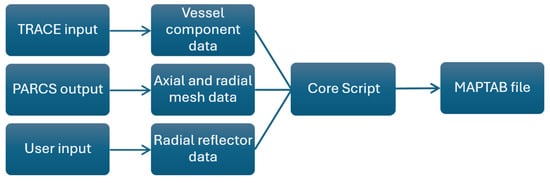

3.3.1. Core Script

The initial script, referred to as the core script, enables map generation and the creation of a mapping file with minimal user input, requiring only a few key data entries. However, the script has limitations regarding the complexity of the geometry it can process, supporting a maximum of 6 azimuthal sectors and 2 radial rings, although the outer ring can include a reflector layer. Data extractions necessary for creating the MAPTAB file are automated within the script using Python’s “Regular Expressions” [18].

A flowchart of the script’s logic is shown in Figure 8. First, a set of data is extracted from TRACE input and the SA PARCS output. Additional parameters that cannot be directly obtained from these files must be provided manually by the user. The script then generates all the additional maps required for the mapping file or modifies existing ones as needed, based on the geometry. It supports geometrical configurations with 1 or 2 radial rings and 1, 2, 3, or 6 azimuthal sectors, enabling the generation of maps with 1 to 12 hydraulic sectors. However, if the radial reflector HS are activated, the coupled simulation fails. Instead, the outer ring HS can be used as a substitute, with a weighting factor of 0 to ensure no neutron power generation in these regions.

Figure 8.

Core script’s logic flowchart.

For axial mapping, it is recommended to maintain consistent axial geometry across thermohydraulic and neutronic models. Nevertheless, the script can modify the weight map and smaller maps as necessary, even if the neutronic, hydraulic, and heat structure nodalizations deviate from the actual vessel geometry.

Additionally, the user can manually activate or deactivate the inclusion of the radial reflector HS and assign a zero-weighting factor to these, if needed.

3.3.2. Graphical Interface

The core script automatically generates the mapping files, requiring minimal user input. However, due to programming complexity when creating more sophisticated maps, an alternative script with a graphical interface was developed. This alternative allows users to manually configure maps with a slightly increased effort, allowing for a greater number of radial rings. The graphical interface, built using Python’s “tkinter” package [19], displays a modified radial map of the core represented by hexagons, each corresponding to a specific node.

A flowchart of the graphical interface functioning is shown in Figure 9. To create the core map, the script first extracts the PARCS radial map, then expands the nodes based on the number of azimuthal sectors for the vessel component. Simultaneously, a corresponding map of weighting factors is generated. Finally, the user selects hexagonal nodes on the interface and assigns each a TRACE Node, which identifies the hydraulic sector where the FA is located, a TRACE HS, corresponding to the HS associated with the FA, and an optional weighting factor available for testing.

Figure 9.

Graphical interface script’s logic flowchart.

This script builds on the programming logic developed for the core script and supports the same number of azimuthal sectors (1, 2, 3, and 6); however, it offers some advantages over the previous script. First, it allows to define additional radial rings, extending the possibility of core geometry configurations. Second, it allows the user to assign any identification number for hydraulic nodes and HS, removing constraints of predefined nomenclatures. Finally, it gives the possibility to assign custom weights, which can be useful, for instance, for disabling the radial reflector HS that are unsupported by the current coupling.

4. Accident Description and Main Results

To validate the developed scripts and coupling methodology, a rod ejection accident scenario at hot full power was simulated [10]. This analysis was conducted using both VVER-1000 thermohydraulic models: the original (9 axial nodes) and the variant (40 axial nodes).

The primary objectives were twofold. First, to verify the accuracy of the axial mapping logic implemented in the scripts, particularly in cases where the two models have differing axial nodalizations. Second, to assess the validity and performance of both models for the specified scenario. The original model uses an axial nodalization that adheres to thermohydraulic requirements, featuring a coarser cell mesh. Conversely, the second model incorporates a finer axial nodalization, which is in a 1:1 scale with the PARCS model, thereby aligning with the detailed meshing required by neutronics.

This dual analysis addresses previous limitations in the coupling procedure, which required identical axial nodalizations for the coupled models, as discussed in [7,8]. By overcoming these constraints, the present work enhances the flexibility and applicability of the coupling methodology for complex reactor simulations.

4.1. Rod Ejection Accident

The rod ejection accident is a subcategory of reactivity-initiated accidents and is classified as a design basis accident according to NUREG 0800 [20].

The event occurs when both the control rod drive mechanism and its drive housing fail simultaneously, resulting in a sudden and rapid withdrawal of the control rod bank. The removal of neutron-absorbing material (poison) introduces a substantial amount of positive reactivity into the core, resulting in a sharp increase in neutron flux and core heat generation. This rapid power excursion causes a short-term spike in reactor power and an adverse power distribution within the core, potentially exceeding the thermal and mechanical design limits of the fuel and reactor system. Given the high speed at which the control rod may be ejected, it can breach the reactor vessel head, possibly initiating a SBLOCA [21].

4.2. Coupled Steady States

The steady-state analysis serves a dual purpose: verifying the consistency of the coupled models and providing a restart point for the transient simulation.

The simulation results were compared to the reference data for ZNPP unit 5 (VVER-100/V-320 design) [22], and to the TRACE SA simulations, which include some additional parameters.

The coupled simulation results show good agreement with both the reference data and the SA simulations, as well as a strong consistency between the two models, as reported in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

SS, SA and coupled simulation results.

Table 3.

SS, -C simulation errors relative to reference data.

No significant discrepancies are observed, except for the water flow in the active zone. The relative error compared with the reference data is −0.60% for the original model and −2.28% for the variant model, respectively. This suggests that a coarser axial nodalization is more appropriate for modeling the TRACE VESSEL component, as evidenced by the smaller deviation in the original model. Conversely, the variant model employs an excessively fine nodalization, which negatively affects the solution process within the vessel and the complex three-dimensional mixing phenomena, leading to an overestimation of the mass flow rate. It should be emphasized, however, that the finer nodalization was introduced solely to verify the applicability of the methodology, and not to quantitively assess its impact on the simulation. Nevertheless, the resulting errors remain within acceptable uncertainty limits for such verification purposes.

It is also worth noting that the inlet and outlet temperatures in the active zone are evaluated by averaging the temperatures of the first and second rings in the first sector, weighted according to the number of fuel pins, which serves as a geometrical weighting factor.

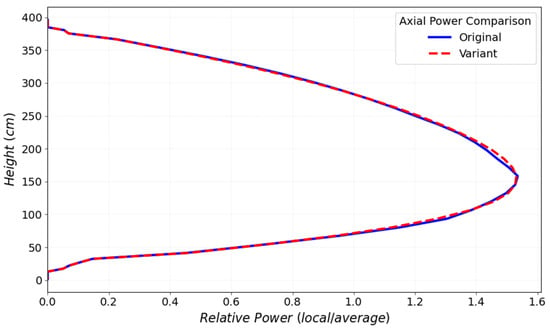

Figure 10 illustrates a comparison between the axial power profiles in terms of relative power (local-to-average power ratio). The original model’s profile is slightly less smooth compared to that of the variant model. This observation underscores the significance of finer nodalization, enabling a more precise evaluation of power distribution. Nevertheless, the coarser nodalization of the original model still produces a sufficiently accurate and consistent power shape.

Figure 10.

Core average axial power profile.

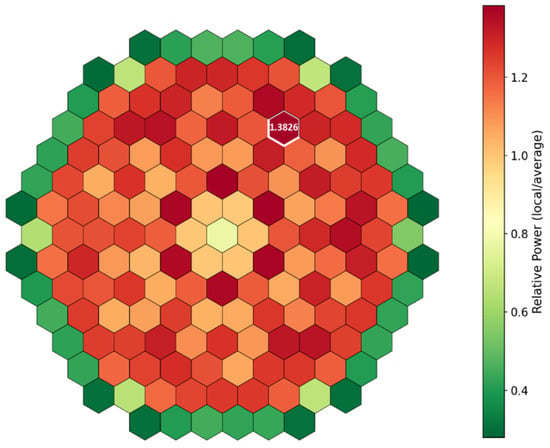

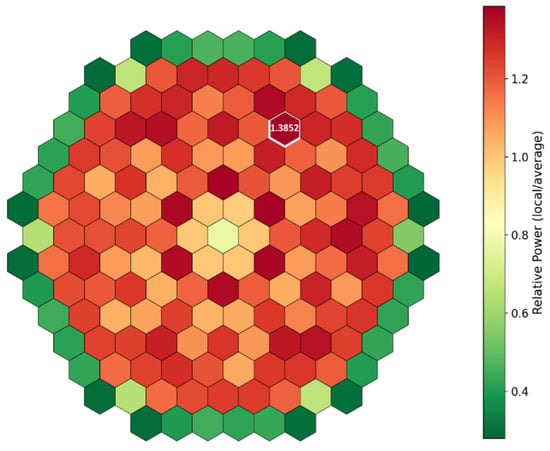

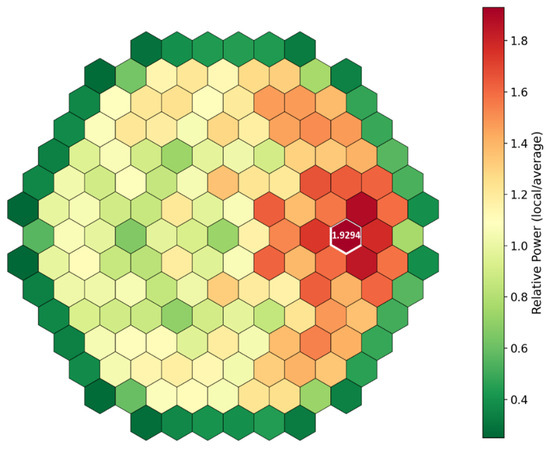

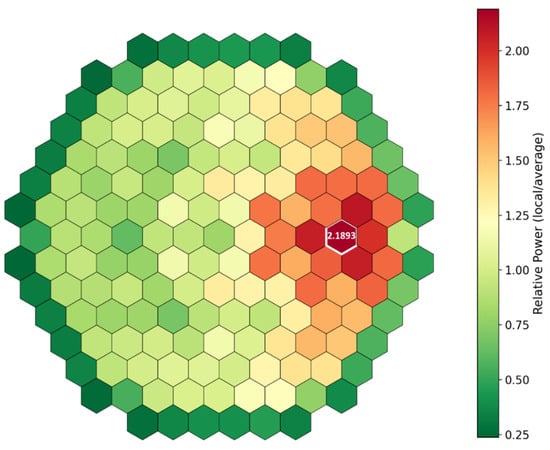

The radial power maps presented in Figure 11 and Figure 12 also show the relative power, with the power peaks location and value highlighted in white. These results confirm that the mapping procedure was executed correctly, as the radial power distribution is approximately symmetric and aligns with the reference data. However, in both simulations, the power peak is slightly shifted toward an outer fuel assembly compared to the SA neutronic simulation. This shift is attributed to the more accurate flow distribution within the core, which enhances moderation in the outer regions and consequently leads to higher power production in those areas.

Figure 11.

Radial power map, coupled PARCS/TRACE, Original model.

Figure 12.

Radial power map, coupled PARCS/TRACE, Variant model.

4.3. Coupled Transients

The transient simulations were computed over a total duration of 200 s. Given the near-complete alignment of results between the two models, the following discussion will focus exclusively on the results obtained from the variant model.

The accident was initiated from an initial condition of 104% nominal power, corresponding to 3120 MW, with the SCRAM signal triggered at 113.5% of nominal power. The simulation assumed four active coolant pumps operating at a reduced water flow rate of 83,000 m3/h. The control rod bank selected for ejection was from group 10, positioned in the right section of the reactor core. The ejection event began at 0.22 s and lasted 0.15 s, resulting in a significant reactivity insertion that caused a pronounced localized power excursion within the core, as illustrated in Figure 13. The resulting radial power distribution matches that of the SA PARCS calculation shown in Figure 14; however, the peak power in the latter is significantly higher. This discrepancy arises because the coupled calculation provides a more accurate assessment of neutronic feedback by dynamically exchanging relevant information between the neutronics and the thermal-hydraulics domains. Consequently, the coupled simulation confirms its role as a best-estimate approach.

Figure 13.

Peak radial power distribution during REA, Coupled PARCS/TRACE.

Figure 14.

Peak radial power distribution during REA, PARCS SA.

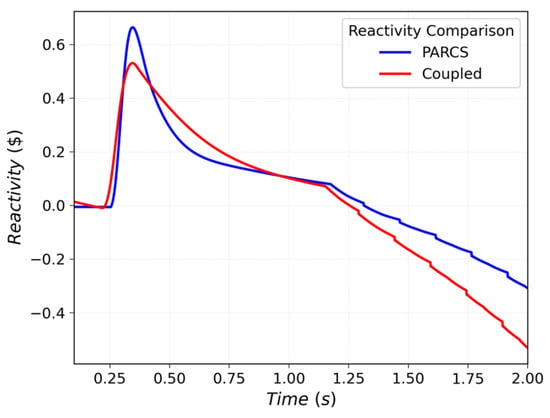

An additional confirmation is provided by the reactivity insertion shown in Figure 15, which illustrates the effect of decreased neutron absorption following control rod withdrawal. The inserted reactivity reaches peak values of 0.66$ in the SA PARCS simulation and 0.53$ in the coupled simulation.

Figure 15.

Reactivity insertion during REA.

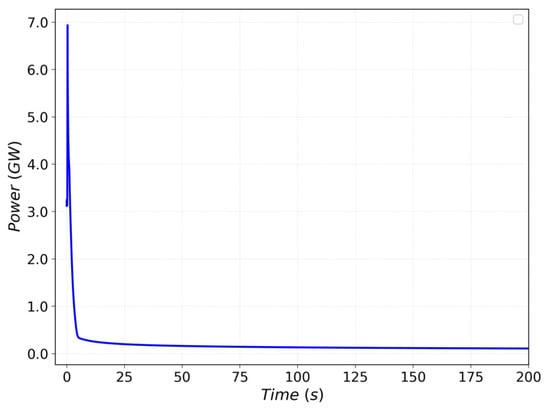

The reactor power peaked at 6.94 GW at 0.35 s before declining, primarily due to Doppler feedback, followed by the activation of the SCRAM system. The SCRAM successfully shut down the reactor, reducing power levels to decay heat levels, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Reactor power during REA.

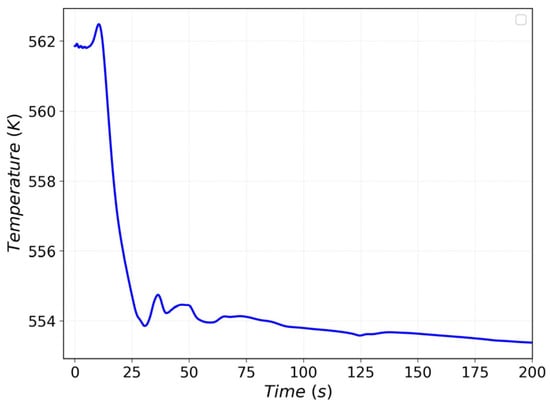

The coolant temperature exhibited a minor peak a few seconds after the power excursion, followed by a rapid decrease to 555 K caused by the reactor shutdown, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Coolant temperature during REA.

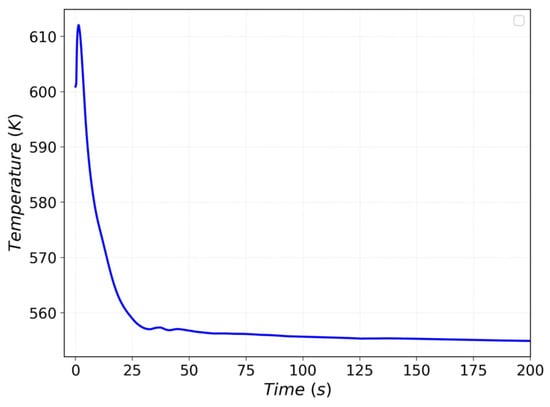

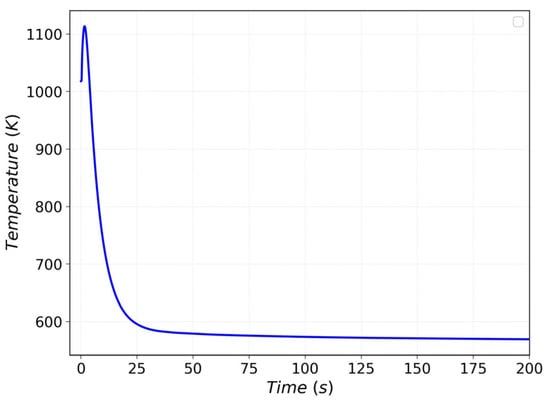

The peak cladding and fuel temperatures followed a similar trend to the reactor power, reaching maximum values of 612 K and 1114 K, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 18 and Figure 19, within the region affected by the ejected rod bank.

Figure 18.

Cladding peak temperature during REA.

Figure 19.

Fuel peak temperature during REA.

Comparison with the utility’s reference data and results obtained using the PARCS code in SA mode indicates excellent agreement, demonstrating the accuracy and robustness of the coupling methodology and simulation approach.

5. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to develop and validate a methodology for coupling PARCS and TRACE codes specifically for hexagonal reactor models. Building upon the tools and expertise established in previous works, the coupling process was streamlined through the creation of two Python scripts. These scripts effectively emulate the SNAP auto-mapping function originally designed for reactors with squared assemblies. To utilize the scripts and generate the required mapping file, users only need to provide TRACE input file along with the output of a stand-alone PARCS simulation. The developed methodology supports geometries with up to six azimuthal sectors and a variable number of radial rings depending of the selected script. While the total axial length of the reactor core must remain consistent between the two models, the methodology accommodates different nodalizations. This flexibility was demonstrated using two thermohydraulic models: one with a coarse axial nodalization and another featuring a fine axial nodalization in a 1:1 scale with the neutronic mesh. The rod ejection accident was selected as a representative transient scenario due to the critical interplay between thermohydraulics and neutronics under such conditions. Steady-state analyses confirmed the validity of the proposed coupling methodology and the mapping logic embedded within the scripts. The results indicated that different nodalization schemes could be employed for the models without compromising the accuracy of the simulations. Furthermore, transient analysis verified the precision and robustness of the coupled simulation approach. The coupled methodology yielded more conservative results compared to the reference data, reinforcing its validity as a best-estimate analysis. This work introduces a reproducible methodology that can be adopted by researchers analyzing hexagonal core reactors using PARCS and TRACE codes. Although initially applied to VVER reactors, the methodology can be extended to other technologies employing hexagonal cores, such as liquid metal reactors, depending on their implementation status within the codes. Moreover, the methodology is not specific to the rod ejection accident and can therefore be readily applied to other coupled scenarios. The automation of the coupling process through Python scripting not only simplifies the workflow but also ensures consistency and accuracy across varied geometrical and nodalization configurations. Currently, however, only the graphical interface script supports models with an arbitrary number of radial rings. Future developments could focus on extending this capability to the core script. In addition, the existing limitations due to incomplete information on radial reflector mapping in the code manuals should be addressed. Once resolved, the scripts could be fully integrated within SNAP, enabling automatic coupling for hexagonal geometries to be available to all users.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M. and G.N.; methodology, A.D. and G.M.; software, A.D., G.M. and G.N.; validation, G.N.; formal analysis, G.N.; investigation, G.N.; resources, A.D. and G.M.; data curation, G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, G.N.; writing—review and editing, A.D., G.M., G.N. and M.D.; visualization, G.N.; supervision, G.M. and M.D.; project administration, A.D. and G.M.; funding acquisition, A.D., G.M., and G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The paper is co-financed from the state budget by the Technology agency of the Czech Republic under the TACR COUPLE (TK05010155) programme. This work has been partially supported by the ENEN2plus project (HORIZON-EURATOM-2021-NRT-01-13 101061677) funded by the European Union.

Data Availability Statement

The results cannot be fully disclosed because they may include sensitive data in the Czech Republic. The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The scripts presented in this study are openly available in “hex_coupling_parcstrace” github repository at https://github.com/nstglc/hex_coupling_parcstrace (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

This work is the result of a collaboration between Sapienza University of Rome, the National Radiation Protection Institute of the Czech Republic, and the Research Centre Řež. The paper is co-financed from the state budget by the Technology agency of the Czech Republic under the TACR COUPLE (TK05010155) programme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| -C | Coupled |

| ECCS | Emergency Core Cooling System |

| FA | Fuel Assembly |

| HS | Heat Structure |

| NPP | Nuclear Power Plant |

| PARCS | Purdue Advanced Reactor Core Simulator |

| PWR | Pressurized Water Reactor |

| REA | Rod Ejection Accident |

| RPV | Reactor Pressure Vessel |

| SA | Stand Alone |

| SBLOCA | Small Break Loss Of Coolant Accident |

| SG | Steam Generator |

| SNAP | Symbolic Nuclear Analysis Package |

| SS | Steady State |

| T/H | Thermal-Hydraulics |

| TRACE | TRAC/RELAP Advanced Computational Engine |

| Tr | Transient |

| U.S. NRC | U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

| VVER | Water–Water Power Reactor |

References

- International Energy Agency. Net Zero by 2050—A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Demazière, C. Modelling of Nuclear Reactor Multi-Physics—From Local Balance to Macroscopic Models in Neutronics and Thermal-Hydraulics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vojackova, J.; Novotny, F.; Katovsky, K. Safety Analyses of Reactor VVER 1000. Energy Procedia 2017, 127, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. NRC. TRACE V5.840 USER’S MANUAL Volume 1: Input Specification; U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. NRC. PARCS v3.4.2 Volume 1: Input Manual; U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Information Systems Laboratories, Inc. Symbolic Nuclear Analysis Package (SNAP) User’s Manual; Version 4.2.1; Information Systems Laboratories: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscak, M.; Mazzini, G. PARCS/TRACE Coupling Methodology for Rod Ejection on Vver 1000 Reactor. Acta Polytech. CTU Proc. 2016, 4, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglierini, B.; Kozlowski, T. Investigation of VVER-1000 Rod Ejection Accident According to the Phenomenon Identification and Ranking Tables for PWR. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2018, 108, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesti, G. PARCS/TRACE Coupling Methodology for Simulating Transient Scenarios in Hexagonal Lattice Reactors. Master’s Thesis, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- AREVA Rod Ejection Accident. Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1207/ML12072A149.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ryzhov, S.B.; Mokhov, V.A.; Nikitenko, M.P.; Bessalov, G.G.; Podshibyakin, A.K.; Anufriev, D.A.; Gadó, J.; Rohde, U. VVER-Type Reactors of Russian Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. NRC the Code Application and Maintenance Program (CAMP). Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/about-nrc/regulatory/research/camp.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Tabadar, Z.; Aghajanpour, S.; Jabbari, M.; Khaleghi, M.; Hashemi-Tilehnoee, M. Thermal-Hydraulic Analysis of VVER-1000 Residual Heat Removal System Using RELAP5 Code, an Evaluation at the Boundary of Reactor Repair Mode. Alex. Eng. J. 2017, 57, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, N.P. VVER-1000 Coolant Transient Benchmark Phase 2 (V1000CT-2), Vol.II: Final Specifications of the MSLB Problem; Nuclear Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, B.; Ivanov, K.; Popov, E. TRACE/PARCS Calculations of Exercises 1 and 2 of the V1000CT-2 Benchmark. In Proceedings of the International Topical Meeting in Reactor Physics (PHYSOR 2006), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–14 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, W.; Hugo, V.; Espinoza, S.; Karlsruhe, F. Safety Related Investigations of the VVER-1000 Reactor Type by the Coupled Code System TRACE/PARCS. J. Power Energy Syst. 2007, 2, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- U.S. NRC. TRACE V5.840 USER’S MANUAL Volume 2: Modeling Guidelines; U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Python.org, Re—Regular Expression Operations. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).[Green Version]

- Python.org, Tkinter—Python Interface to Tcl/Tk. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/library/tkinter.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).[Green Version]

- LWR Edition (NUREG-0800); Standard Review Plan for the Review of Safety Analysis Reports for Nuclear Power Plants. Formerly Issued as NUREG-75/087. U.S. NRC: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.[Green Version]

- Diamond, D.J.; Bromley, B.P.; Aronson, A.L. Studies of the Rod Ejection Accident in a PWR; Brookhaven National Laboratory: Suffolk County, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Iegan, S.; Mazur, A.; Vorobyov, Y.; Zhabin, O.; Yanovskiy, S.; Tien, K. NUREG/IA-0490 “International Agreement Report—TRACE VVER-1000/V-320 Model Validation”; U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).