Abstract

To address global warming challenges, industry, transportation, residential, and other sectors must adapt to reduce the greenhouse effect. One promising solution is the use of renewable energy and energy-saving mechanisms. This paper analyzes several renewable energy sources and storage systems, taking into consideration the possibility of integrating them with smart homes. The integration process requires the development of smart home energy management systems coupled with renewable energy and energy storage elements. Furthermore, a real-life solar energy power plant composed of programmable components was designed and mounted on the roof of a single-family residential building. Based on a long-term analysis of its operation, the main advantages and disadvantages of the proposed implementation solution are highlighted, exemplifying the concepts presented in the paper. Being composed of programmable components, which allow the implementation of custom algorithms and monitoring applications to optimize its operation, the system will be used as a prototyping platform in future research. The evaluation of the developed system over a period of one year showed that, even when using a basic implementation such as the one in this paper, significant savings regarding a household’s energy consumption can be achieved (36% of the energy bought from the supplier, meaning EUR 545 from a total of EUR 1497). Finally, based on the analysis of the developed prototype system, the main technical challenges that must be addressed in the future to efficiently manage renewable energy storage and use in today’s smart homes were identified.

1. Introduction

Global warming is a reality confirmed by recent climate changes that include devastating weather events such as hotter heat waves, extreme droughts, heavier rainfall, hurricanes, and much stronger tropical storms. The main driver of global warming is the greenhouse effect produced by certain gases, in particular carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases resulting from daily human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, gasoline, natural gas), intensive livestock farming, deforestation, and crop fertilization. To mitigate this issue, during the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference, all nations committed to shift away from fossil energy to cleaner, smarter energy. Therefore, finding more sources of renewable energy to replace fossil fuels, and the efficient of use energy with the integration of renewable energy sources and energy storage systems are two objectives that must be addressed [1].

The term renewable energy refers to energy that comes from natural sources or processes that are constantly replenished over a relatively short period [2]. This type of energy, besides reducing global warming, uses free and inexhaustible natural resources. Renewable energy provides stable energy prices over time, requires lower maintenance efforts, creates new jobs, and reduces the energy dependence between countries. However, renewable energy also requires high upfront costs [3] and a lot of space [4], such energy can be intermittent, depending on weather conditions or natural phenomena [5], and its storage remains a challenge [6]. The advantages of using renewable energy offset the disadvantages if we have in mind the planet and the health of its inhabitants.

The main renewable energy sources are water, wind, sun, biomass, earth, and hydrogen. Table 1 presents the types of energy generated by these sources along with their features, and highlights whether they can produce electricity, heat, or fuel in power plants or households.

Table 1.

Renewable energy sources.

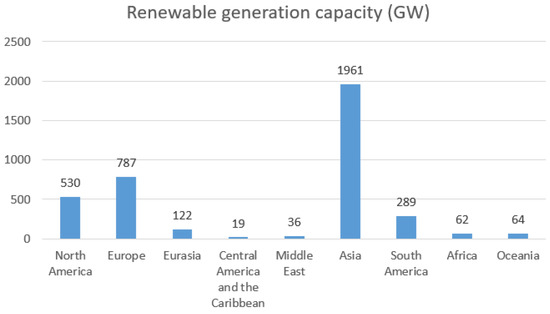

In recent years, nations have made substantial investments in renewable energy production. A recent report published in March 2024 by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) showed that the world’s capacity to generate energy from renewable sources reached 3870 GW at the end of 2023 with an increase of 13.9% (473 GW) observed during 2023 [13]. Solar energy reached a capacity of 1432 GW (37%), hydroelectric energy achieved a capacity of 1277 GW (33%), and wind energy a capacity of 1006 GW (26%), while other types of renewable energies accounted for the remainder (5%). Figure 1 shows the renewable generation capacity by region in GW at the end of 2023. Asia, Europe, and North America generated 84.70% of the global total renewable energy, but the other regions also recorded increases according to the report.

Figure 1.

Renewable generation capacity by world regions in GW at the end of 2023 according to [13] (Eurasia includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Turkey).

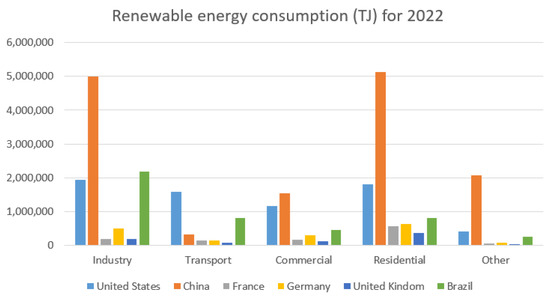

Industry, commerce, transportation, residential, and other sectors consume the renewable energy generated. Recently, the IRENA [14] published information on the final renewable energy consumption in the sectors (such as transportation, commerce, residential, and so on) we mentioned above for several countries for 2022. Figure 2 presents this information for six countries and highlights that the residential sector was one of the main beneficiaries of renewable energy and demonstrates the potential of using it in this segment. Households are increasingly using smarter appliances, turning these homes into smart homes and improving the quality of life of the occupants. The adoption of various gadgets and emerging technologies (i.e., Internet of Things (IoT) devices, high-speed wireless networks) increases energy consumption. The use of renewable energy sources and energy-saving mechanisms should be simultaneously considered to reduce the household energy costs, while offering an eco-friendly solution.

Figure 2.

Renewable energy consumption by country and sector for 2022 according to [14]. The data from [14] were last updated on 11 July 2024.

To achieve this, the following steps must be considered. First, we must conduct an analysis of the operational energy demand of a household and the potential for integrating renewable energy sources. This analysis will help to identify technical solutions for generating and storing renewable energy, as well as for trading energy back to the energy provider if needed. The integration of the identified solutions within a smart home energy management system (SHEMS) is the next step. An SHEMS aims to monitor, control, and optimize the energy sources, energy storage, and home appliances in the most efficient way.

This paper presents the design and implementation of an SHEMS prototype featuring an energy generation system based on photovoltaic cells and programmable components, which we used as a case study. We will use the system as a configurable platform for implementing experimental algorithms for optimization and control in our future works. We evaluated the operation of the system developed over a period of one year. The results obtained from this basic implementation showed that we could achieve significant savings regarding the household’s energy consumption: a reduction of 36% in the amount of energy bought from the supplier, meaning EUR 545 from a total of EUR 1497.

Main Contributions of This Work

We summarize our research contributions as follows:

- We present the design architecture and operation of a photovoltaic energy generation system composed of programmable components, which will enable the prototyping of advanced monitoring and control algorithms for the operation of the power plant using LabVIEW. The system highlights the benefits of renewable energy systems for smart homes and provides a reference design that supports extensive customization.

- We provide real operational data, and we present an analysis of the generated energy, as well as practical considerations that resulted from the design of the system.

- Finally, we identify the main technical challenges that must be addressed when renewable energy sources are integrated into smart homes, considering the design and analysis of the developed photovoltaic system composed of programmable components.

We organize the rest of the paper as follows. Section 2 presents a review of several research efforts regarding SHEMSs with renewable components and highlights their approaches, along with the major results obtained and their drawbacks and limitations. In Section 3, we describe the system components of the prototype real-life solar energy power plant installed in a household. The components of the developed systems can be programmed using the LabVIEW 2023 graphical language to implement different optimization strategies and to develop custom remote monitoring and control applications. We present one such monitoring application here and, based on the data acquired from the system, we draw conclusions specific to the system’s operation and propose potential improvements. Section 4 discusses a few general technical challenges that must be addressed in the generation of energy from renewable sources. In Section 5, we make some concluding remarks.

2. Related Works

The evolution of technologies has transformed traditional houses into 21st century smart homes. Today, houses are being built with a plethora of smart home products, with automation being a key design goal. In recent years, we have witnessed many traditional houses being converted into smart homes by integrating smart systems for heating, cooling, or lighting [15].

A smart home offers several benefits, such as convenience, increased safety, accessibility, and significant energy savings. To reap these benefits, a smart house should include

- An energy generation system (EGS) that allows households to diversify their energy sources as well as take part in electricity production [16].

- An energy storage system (ESS) to store the energy generated.

- An SHEMS that will monitor and manage energy consumption, and enable household appliances that are networked together and that can be controlled remotely.

In this section, we review and analyze several research efforts that proposed various designs [1,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] of SHEMSs with renewable components, from the early 2000s. We selected these specific research efforts because they show the evolution of such systems over time, starting from the simplest implementation of a renewable energy system for households, to current state-of-the-art designs.

In [17], the authors presented an SHEMS that integrates solar EGS and storage energy resources to support smart home energy requirements. The hardware and software architectures of the proposed system provide switching between power from the Australian national grid and the power generated by the integrated renewable elements based on energy flow scenarios and the use of a battery energy storage systems (BESS). The experiments showed that the integration of renewable energy sources saved 33.5%, 35.7%, and 32.23% of the total home energy bill at three pricing intervals (peak (2 p.m.–8 p.m.), shoulder (7 a.m.–2 p.m. and 8 p.m.–10 p.m.), and off-peak (all other times)). The authors did not describe the details of the amount of energy produced from solar energy and how it is used by household appliances. The authors of [18] considered both home energy consumption and generation simultaneously to minimize energy costs. The proposed SHEMS integrates both solar and wind power systems. Their system can estimate the amount of generated energy based on the time of the day and the weather conditions. Based on energy prices, the system can schedule the home appliances to operate in a manner that increases their energy consumption efficiency. Similarly, the authors of [19] proposed an optimized SHEMS which integrates renewable energy sources and an ESS to minimize the electricity bill and peak-to-average ratio (PAR). The proposed system uses mathematical models for energy generation from renewable energy sources, energy storage, energy consumption, energy pricing, and appliance scheduling. The results obtained showed that the integration of renewable energy and ESS reduced the electricity bill by about 20%. This reduction was improved further (approximately 25%) by the addition of a hybrid genetic particle swarm optimization (HGPO) algorithm to schedule the load of the system. In [20], the authors proposed a hybridized intelligent home renewable energy management system which incorporates solar elements and BESS. The efficient control algorithm of the system manages the home electricity consumption based on how much power can be stored in the battery using the available energy, the weather forecast, and the expected energy demand over the next 24 h. The results showed a decreased energy consumption of 48% and an increase in renewable energy consumed at a rate of 65% of the total generated energy. The approach proposed by the authors of [1] is better than the approaches presented so far, because it also enables the sale of surplus energy to the following buyers: electric vehicles, other households, or even electricity providers. Therefore, the ESS of the proposed SHEMS with a renewable energy generation system can store the electricity from the main grid when the price of energy is low, as well as electricity generated by the EGS. The stored energy is used when the electricity price is high or is sold if it exceeds the required load demand. In addition, the approach proposed in [1] used a combination of two heuristic algorithms, particle swarm optimization (PSO) and binary particle swarm optimization (BPSO), to minimize the energy cost of their system to 19.7%. This led to a very high value for the system’s PAR. The authors of [21] presented an intelligent monitoring system based on cost-effective hardware and lightweight software to optimize photovoltaic system performance. The solution features an IoT platform, a cloud-based service, and a user-friendly web interface. It integrates a neural network for day-ahead output forecasting and real-time detection of three types of electrical faults, enhancing the reliability of PV operations. The system’s effectiveness was demonstrated through validation on an experimental testbed. In [22], the authors presented a monitoring system for an off-grid photovoltaic installation powering a miniature greenhouse. It enables remote tracking of key parameters such as PV currents, voltages, solar irradiance, and cell temperature using low-cost hardware and a web application. The proposed system also employs fault-detection mechanisms, ensuring efficient and reliable operation of the system. The small-scale system presented in the paper was simulated and experimentally validated under extreme conditions, including intense heat and exposure to sandstorms, which are typical of desert environments. The authors of [23] proposed a data acquisition and monitoring system for large-scale PV installations located in remote areas. The IoT-based solution is based on low-cost hardware and open-source software and collects information on the current, voltage, and temperature of the PV cells, as well as environmental data like temperature, irradiance, humidity, and atmospheric pressure. It can detect operational malfunctions in the PV system. Additionally, the collected data are also utilized for power forecasting using various prediction algorithms. The authors of [24] empirically analyzed the behavior of an off-grid hybrid renewable system (wind and solar) with storage, which represents a flexible and modern solution for households. The analysis was performed on an experimental setup that can be considered a test platform for hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES), with the possibility of scaling up the power installed for actual implementations. The authors investigated the ability of the system to cover the electricity needs of a household under three different scenarios and found out that none of the scenarios could fulfill this goal. In [25], the study highlighted the essential role that autonomous monitoring and analysis will play in the future of photovoltaic systems as the installed capacity continues to increase. The advanced techniques discussed will enable early detection of system failures, enhancing energy management and optimizing consumption across the power grid.

All these studies demonstrate that photovoltaic (PV) systems, which directly convert solar radiation into electricity, represent the major renewable energy technology currently used for improving the energy performance of buildings and reducing their impact on the environment.

Table 2 summarizes the approaches to SHEMSs we have discussed above and highlights their main results, strengths, and weaknesses. It also presents the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed system we describe in the next section of the paper.

Table 2.

Summary of SHEMS research efforts.

Table 2 shows that the previous approaches faced a set of challenges: the architecture of these types of systems should support easy reconfiguration in order to allow the implementation of more advanced algorithms for optimizing and controlling energy generation and consumption within a smart home; limited accuracy of forecasts; the management of large amounts of acquired data; low-cost aspects; and the security and privacy of the data. In addition, the results of these studies were obtained from simulations and using experimental setups.

To address some of the limitations of these past approaches, we proposed a real-life prototype of an SHEMS with an energy generation system, composed of programmable components, that can be considered a configurable platform for evaluating the efficiency of custom algorithms for optimization and control. This system addresses the challenge of flexible and easy reconfiguration that we identified after reviewing the past related works.

3. Prototype Implementation

This section presents the prototype solar energy power plant that we designed and implemented. It includes a monitoring component, placed in the central area of Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Its EGS has 16 monocrystalline solar panels with a maximum installed power of 5.5 kW. These are placed on the same side of the roof and can generate 10–40 kWh of energy on sunny days, in an eight to fifteen hour interval. The generated electricity is used to supply power to a household, and because the system cannot store surplus energy, this energy is injected into the smart grid [26].

3.1. System Components

The components of our system include

- Sixteen monocrystalline solar panels, type JA Solar 340 W, connected in a series configuration.

- A Fronius Primo 5.0 inverter (Fronius International, Sattledt, Austria), without a local energy storage unit (no accumulator).

- A technical panel that includes electrical terminals and fuses.

- A sub-system for measuring the generated energy and for the transmission of acquired data to the cloud, implemented using National Instruments equipment (required for research and for the generation of tracking algorithms).

The inverter included in the system has its own component in charge of monitoring energy parameters, which are provided through Ethernet connections. Table 3 presents the main characteristics of the solar panels installed.

Table 3.

Principal characteristics of the JA Solar 340 W solar panel [27].

The Fronius Primo 5.0 inverter requires a minimum voltage of 80 V at its input. This means that each one of the 16 panels that are connected in series must generate at least 5 V to start electricity generation. This inverter can work for an extended period, even when the light intensity is low, during sunrise or sunset. It can accommodate two series of panels, having two separate inputs for which it can track the maximum power point (MPP) [28]. The maximum voltage is 2 × 800 V, and the maximum working current is 2 × 12 A [29].

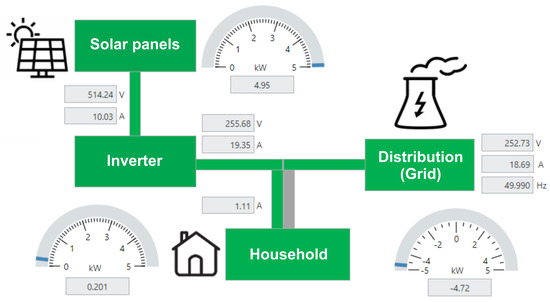

An important component of the system is represented by the monitoring application. It was developed using the LabVIEW™ graphical programming language and offers real-time graphical representation of the continuously acquired data through a web page. The transmission of data to the cloud uses SystemLink Cloud™ 2023 and we implemented the web interface using WebVIs provided by the G Web Development Software 2023 environment. The application also includes financial data which help in calculating the return of investment. The main view of the monitoring application shows that energy generated from the solar panels is injected into the grid, as Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3.

Monitoring application–main view.

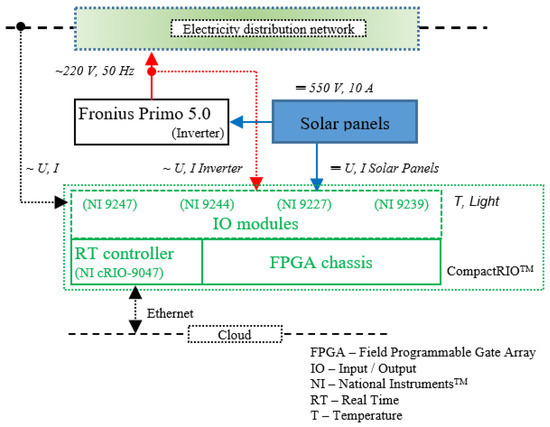

The equipment for monitoring and displaying data is composed of an NI CompactRIO™ 9047 controller running Linux, programmed using LabVIEW™ and FPGA toolkits 2023. The chassis includes a Kintex-7 family FPGA to implement the primary part of the data acquisition. It offers a first in, first out–direct memory access (FIFO-DMA) data transfer mechanism that guarantees that no data loss occurs (voltage, current). This architecture is required because the energy generation system is actually an energy meter. Figure 4 shows a block diagram of the energy generation system, where the connections between all components are specified.

Figure 4.

Energy generation system block diagram.

Several specialized extension modules are used for acquiring voltage and current data:

- NI 9244 (400 Vrms L-N, 800 Vrms L-L, 50 kS/s/ch, 24-bit, 3-phase C series voltage input module)—for measuring the DC voltage from the solar panels, the AC voltage from the inverter, and the AC voltage in the distribution network.

- NI 9227 (50 kS/s/ch, 5 Arms, 24-bit, 4-channel C series current input module)—for measuring the generated DC intensity. All the current channels are connected in parallel to extend the measurement range from 5 A to 20 A.

- NI 9247 (50 kS/s/ch, 50 Arms, 147 Apk, 24-bit, 3-channel C series current input module)—for measuring the AC intensity for the inverter, for the house, and for the distribution network.

- NI 9239 (10 V, 50 kS/s/ch, 24-bit, simultaneous input, 4-channel C series voltage input module)—for measuring the temperature and the light intensity at the panel level.

Currently, the energy that the installed system injects into the grid is not considered in the energy bill of the house where it is installed. To achieve this, we must file a request to connect the system to the distribution network of the energy supplier, to certify the energy producer status of the owner of the energy generation system, and then sign a contract with the energy supplier so that the energy generated and not used by the energy generation system is considered in each bill.

The monitoring system, based on CompactRIO™, shows the quality of the generated energy in real time on the user interface: voltage and current intensity, effective and maximum values, the frequency of the AC, power phasor, and harmonics, both numerical and graphical. The system can also measure the light intensity on the panels for computing the efficiency and the temperature. On a cloudy rainy day, the solar panels produce a maximum of 500 W (the voltage is higher than 500 V, but the intensity of the current is less than 1 A).

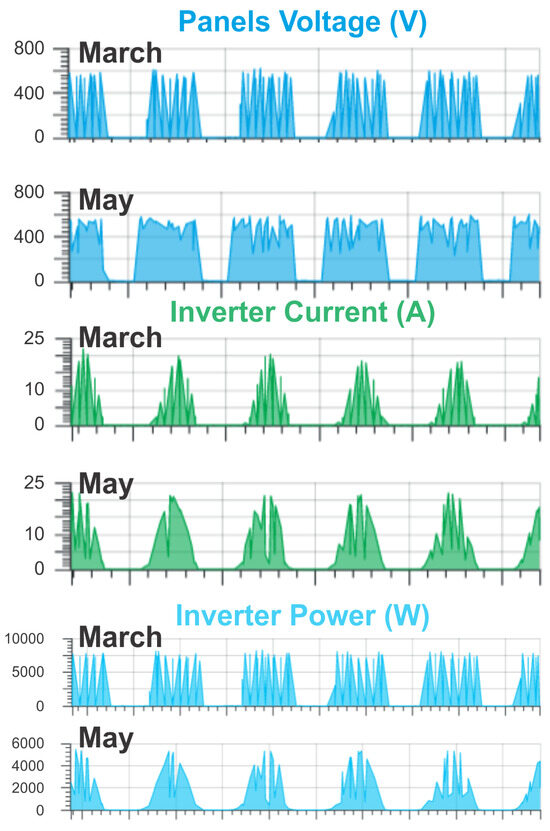

The results presented in Figure 5 compare two operational periods of 5 days in the months of 27–31 March 2024 and 11–16 May 2024. The graphs were generated using a web-based application. The two energy quantities did not differ a lot, but we observe that in March, there were many cases in which there were drops in the voltage and current intensity caused by cloudy weather. This situation did not occur so often during May.

Figure 5.

Voltage, current, and power (y-axis) for 5 days (x-axis), 27–31 March and 11–16 May 2024.

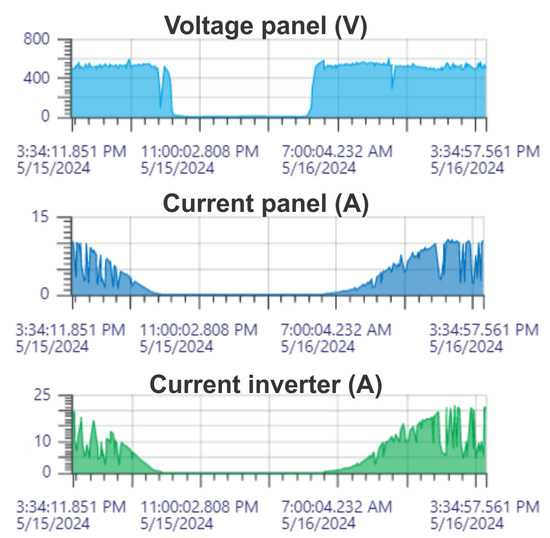

The 16 May 2024, presented in Figure 6, was a sunny day, with clouds that only partially covered the sky. The intensity measurement shows that there were many periods with low values of generated power. The intensity of the current generated by the inverted (bottom graph) was different from that measured at the panel level (middle graph), and this was the result of the maximum power point (MPP) algorithm [28], which undertook the modification of the current and voltage generated so that the maximum power was obtained.

Figure 6.

Voltage and current (y-axis) on 16 May 2024 (x-axis).

Table 4.

Values recorded by the system on 16 May 2024.

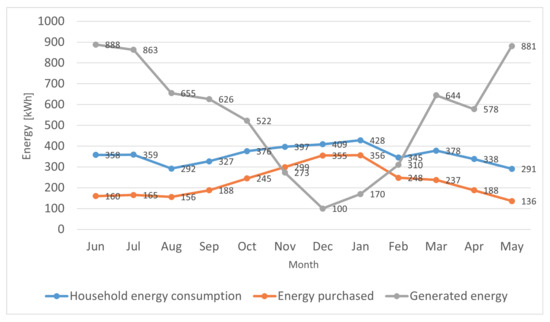

Figure 7.

Energy balance from June 2023 to May 2024.

Figure 7 presents the total energy generated over 12 months (June 2023–May 2024), the energy consumption in that period, as well as the energy purchased to meet the energy demand of the household. Since there is no energy storage, the energy that was bought from the grid was not computed as the difference between the energy produced and the energy consumed. Having no storage, the energy consumed at night cannot be provided by the energy generation system. The total energy consumption of the household was 4.3 MWh, while the amount of energy generated from the photovoltaic cells was 6.5 MWh. Although the amount of generated energy was higher than the amount of energy consumed by 51%, the quantity purchased from the energy supplier was 2.7 MWh (64% of the energy the household consumed).

This shows that, without rigorous planning of the consumption and without energy storage (e.g., using accumulators), the renewable energy generation system was able to produce only 36% of the energy the household required.

Considering the current energy prices in Romania and the fact that the renewable energy injected into the grid was not tracked, the total savings achieved was EUR 545 (EUR 1497 worth of energy consumed in total minus EUR 952 paid for energy purchased from the energy supplier considering EUR 348 per MWh).

By considering the same price for the energy that was injected into the energy distribution network, the money that should be received by the owner of the renewable energy generation system is EUR 1709. In this case, the economic balance would be positive, with the system covering the total household energy consumption of EUR 1497, with the cost of the energy purchased from the energy supplier of EUR 952 and generating a profit of EUR 757 per year.

3.2. Challenges and Possible Improvements

The distribution of the solar panels in two groups, connected in series, made possible by the configuration of the Fronius Primo 5.0 inverter would increase the amount of generated energy. This is because two different orientations are provided by the system in a case where each of the two groups is placed on the two sides of the roof.

One major disadvantage of having all the panels connected in series is if a panel is in shadow, the current in the circuit is given by that panel and the generated power is lower. If the panels are connected in parallel, the total current is larger, and losses of power occur because of the resistance of the conductor materials. There are solutions which use local DC/DC micro-converters for each panel, but this increases the installation costs.

The cost of the entire system, including the solar panels and the inverter, without local energy storage using an accumulator, was approximately EUR 4000. This does not include commissioning, which varies depending on the architecture of the building on which the panels are placed. A thorough financial evaluation should be performed to make sure that a return of investment is possible.

The use of solutions for protecting the panels would be beneficial, because it is a well-known fact that the placement of panels in urban spaces must overcome the effects of factors such as humidity and dust.

One requirement that affects the sale of energy by individuals who own renewable energy generation systems is the requirement from the energy distributor’s side of providing a plan of the energy that will be generated and fed into the distribution network.

4. Technical Challenges

Several technical challenges for integrating renewable energy sources into a household must be addressed in the future. As we have previously noted, the energy needed for a home can be generated in whole or in part from various renewable sources. The household continues to be connected to the power grid, either to receive the energy it still needs or to deliver the surplus of energy not needed. The intermittent feature of renewable energy resources causes voltage and frequency fluctuations when the generated energy is delivered to the power grid. Moreover, renewable energy generating equipment mainly depends on power electronic devices, and this introduces harmonics which affect the quality of power. Modern home appliances also affect the power quality because they embed electronic devices with high harmonics. Improving the quality of power generated is an important challenge that must be addressed. Thus, optimal size and planning of energy generation systems must be thoroughly performed [30]. The storage of renewable energy improves the power quality and voltage stability and supports peak load demand. But an ESS is expensive and requires separate installation space in a home. Thus, making ESSs easier to integrate into a home while being cost-effective is another challenge. Another issue is the management of EGSs, ESSs, smart meters, sensors, and home appliances through the SHEMS to balance the generated energy and load. The development of advanced algorithms/schemas that consider the amount of available energy stored and its prediction, the variation in electricity tariffs, and the household electricity demand at certain time intervals, to reduce electricity consumption and increase economic profits is another challenge currently being addressed by numerous researchers but that still requires more research.

5. Conclusions

The generation of energy from renewable sources has received a lot of attention lately due to the acceleration of global warming and because of the ever-increasing demand for energy for both household and industrial uses. In this paper, we analyzed the renewable sources that can be used for generating energy, considering their application to small installations in family homes. We found that energy generation using photovoltaic panels can provide significant amounts of energy for smart homes and show promise for achieving economically efficient installations that protect the environment. To demonstrate the potential of generating energy for households using photovoltaic technology, we designed and implemented an real prototype system that has been running for a year in a house located in the center of Cluj-Napoca, Romania. The system is programmable using LabVIEW and allows the implementation of advanced algorithms for monitoring and control of its operation. This prototype real-life test platform is suitable for custom optimization algorithms and remote monitoring and control applications. The analysis of the operation of the power plant implemented showed that the energy generated by the solar panels resulted in a reduction of 36% in the amount of energy bought from the supplier. Furthermore, during the spring and summer months, the solar energy produced exceeded the household energy consumption. We presented a performance evaluation of the prototype system and highlighted some of the challenges and possible improvements related to its use. The energy of a modern home should be managed by a system that includes energy generation and energy storage subsystems and an SHEMS. We investigated the techniques that can be used to develop each component of this system, starting from the main functions it has to perform. Finally, we discussed some technical challenges that we must address in the future to enable the large-scale deployment of systems that generate energy from renewable sources for smart homes.

Author Contributions

T.S., G.D.M. and S.F. proposed the idea and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.Z., S.F. and H.H. provided technical supervision, insights, and additional ideas on the presentation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments which helped us improve the organization, content, and presentation of this paper. Sherali Zeadally was partially supported by a Distinguished Visiting Professorship from the University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage Systems |

| BPSO | Binary Particle Swarm Optimization |

| EGS | Energy Generation System |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| FIFO-DMA | First In, First Out–Direct Memory Access |

| HGPO | Hybrid Genetic Particle Swarm Optimization |

| HRES | Hybrid renewable energy system |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| MPP | Maximum Power Point |

| NOCT | Nominal Operating Cell Temperature |

| PAR | Peak-to-Average Ratio |

| PLC | Power Line Communication |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PTC | Photovoltaic US Test Conditions |

| SHEMS | Smart Home Energy Management System |

| STC | Standard Test Conditions |

| US | United States |

References

- Dinh, H.T.; Yun, J.; Kim, D.M.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, D. A Home Energy Management System with Renewable Energy and Energy Storage Utilizing Main Grid and Electricity Selling. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 49436–49450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, T.C.; Farhar, B.C. Public Reaction to Renewable Energy Sources and Systems. In Encyclopedia of Energy; Cleveland, C.J., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman; Moorthy, K.; Patwa, N.; Saravanan; Gupta, Y. Breaking barriers in deployment of renewable energy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zalk, J.; Behrens, P. The spatial extent of renewable and non-renewable power generation: A review and meta-analysis of power densities and their application in the U.S. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Zubo, R.H.A.; Rashid, F.L.; Dakkama, H.J.; Abd-Alhameed, R.; Mujtaba, I.M. Evaluation of Solar Energy Powered Seawater Desalination Processes: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousksou, T.; Bruel, P.; Jamil, A.; El Rhafiki, T.; Zeraouli, Y. Energy storage: Applications and challenges. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 120, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougias, I.; Aggidis, G.; Avellan, F.; Deniz, S.; Lundin, U.; Moro, A.; Muntean, S.; Novara, D.; Pérez-Díaz, J.I.; Quaranta, E.; et al. Analysis of emerging technologies in the hydropower sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bassam, N. Chapter Eight–Wind energy. In Distributed Renewable Energies for Off-Grid Communities, 2nd ed.; El Bassam, N., Ed.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuşkaya, S.; Bilgili, F.; Muğaloğlu, E.; Khan, K.; Hoque, M.E.; Toguç, N. The role of solar energy usage in environmental sustainability: Fresh evidence through time-frequency analyses. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Saydaliev, H.B.; Lan, J.; Ali, S.; Anser, M.K. Assessing the effectiveness of biomass energy in mitigating CO2 emissions: Evidence from Top-10 biomass energy consumer countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 191, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo-Torrejón, E.; Colmenar-Santos, A.; Rosales-Asensio, E.; Mur-Pérez, F. Economic and environmental benefits of geothermal energy in industrial processes. Renew. Energy 2021, 174, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R.; Shah, R.R. Hydrogen as energy carrier: Techno-economic assessment of decentralized hydrogen production in Germany. Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Capacity Highlights. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2024/Mar/IRENA_RE_Capacity_Highlights_2024.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Data and Statistics. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Data/View-data-by-topic/Renewable-Energy-Balances/Overview-Tables (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Hammi, B.; Zeadally, S.; Khatoun, R.; Nebhen, J. Survey on Smart Homes: Vulnerabilities, Risks, and Countermeasures. Comput. Secur. 2022, 117, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, I.; Matthies, E. How do PV households use their PV system and how is this related to their energy use? Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A.; El-Hag, A.; Bahadiri, M.; Harbaji, M.; Ali El Haj, Y. Smart Home Renewable Energy Management System. Energy Procedia 2011, 12, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Choi, C.S.; Park, W.K.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.H. Smart home energy management system including renewable energy based on ZigBee and PLC. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2014, 60, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, A.; Javaid, N.; Hussain, H.M.; Abdul, W.; Almogren, A.; Alamri, A.; Azim Niaz, I. An Optimized Home Energy Management System with Integrated Renewable Energy and Storage Resources. Energies 2017, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, B. Hybridized Intelligent Home Renewable Energy Management System for Smart Grids. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, M.; Eskandari, A.; Aghaei, M.; Nedaei, A.; Sizkouhi, A.M.; Milimonfared, J. Cloud Computing and IoT Based Intelligent Monitoring System for Photovoltaic Plants Using Machine Learning Techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamied, A.; Mellit, A.; Benghanem, M.; Boubaker, S. IoT-Based Low-Cost Photovoltaic Monitoring for a Greenhouse Farm in an Arid Region. Energies 2023, 16, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.E. A New Low-Cost Internet of Things-Based Monitoring System Design for Stand-Alone Solar Photovoltaic Plant and Power Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, T.; Ungureanu, C.; Pentiuc, R.D.; Afanasov, C.; Ifrim, V.C.; Atănăsoae, P.; Milici, L.D. Off-Grid Hybrid Renewable Energy System Operation in Different Scenarios for Household Consumers. Energies 2023, 16, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M. Autonomous Monitoring and Analysis of Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedesiu, H.; Grebla, H.; Nemes, R.; Oprea, C. Monitoring of Individual Photovoltaic Systems using Internet of Things Industrial Technologies. Energetica 2021, 69, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- SolarDesignTools. JA Solar JAM60S10-340/PR (340W) Solar Panel. 2022. Available online: http://www.solardesigntool.com/components/module-panel-solar/JA-Solar/5445/JAM60S10-340-PR/specification-data-sheet.html (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Cupertino, A.F.; Pereira, H.A. Chapter 21—Next generation of grid-connected photovoltaic systems: Modeling and control. In Design, Analysis, and Applications of Renewable Energy Systems; Azar, A.T., Kamal, N.A., Eds.; Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (ANDC); Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 509–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronius International GmbH. Fronius Primo 5.0-1. 2022. Available online: https://www.fronius.com/en-gb/uk/solar-energy/installers-partners/technical-data/all-products/inverters/fronius-primo/fronius-primo-5-0-1 (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Erenoğlu, A.K.; Çiçek, A.; Arıkan, O.; Erdinç, O.; Catalão, J.P.S. A New Approach for Grid-Connected Hybrid Renewable Energy System Sizing Considering Harmonic Contents of Smart Home Appliances. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).