Abstract

This article discusses the impact of rail market liberalization on the energy intensity of rail in relation to the export of goods, as well as the identification of multidimensional cause-and-effect relationships between rail energy intensity and the importing country’s economic condition, transport performance, and transport distance. Three research questions were formulated: (1) Does the liberalization of the EU transport market and the implementation of a sustainable transport policy contribute to minimizing the energy consumption of rail transport? (2) Does the pursuit of economic growth allow for reducing the energy intensity of goods exported by rail transport in global trade? (3) Is there a justified paradigm for shifting long-distance freight transport from roads to rail? This study concerned 21 directions of the export of goods transported by rail from Poland to partner countries (worldwide) in 2010–2020. A panel model of rail transport energy consumption with random effects was constructed. As a result of rail market liberalization, the export of goods transported by rail across great distances occurs without harming economic development and leads to a reduction in energy intensity. On this basis, key strategies were formulated to promote rail transport in reducing the energy intensity of the transport sector. The authors filled the research gap by identifying the relationship between the energy intensity of exports of goods by rail transport in value terms, depending on the European transport market’s liberalization process, the importing countries’ economic situation, transport volume, and distance. The presented approach is innovative and can be adapted to the analysis of other modes of transport, including road transport, and other countries (and their structure and export directions).

1. Introduction

Rail freight transport plays an integral role in the economy, enabling the efficient flow of goods over long distances. It is recognized as a sustainable, safe, and profitable mode of transport [1,2,3]. It also improves regional and interregional relations, which is critical for the spatial evolution and economic integration of different areas [4]. Furthermore, rail freight transport is the cornerstone of economic stability and growth, providing a sustainable and efficient way to transport goods [1]. It serves entities by streamlining goods flows, reducing delivery times, and enhancing service quality [5,6,7]. The structure of rail freight transport is likely to alter due to global trends such as energy intensity reduction, decarbonization, and the circular economy, which may restrict the transport of some items such as coal and oil [6]. The development of intermodal transport networks, with rail playing a key part, is required for the sustainable development of freight transport [8]. Overall, rail freight transport is an important part of a stable and sustainable economy. Building a resilient and sustainable transport system plays a key role in achieving the sustainable development goals. Within these assumptions, solutions are sought to reduce the negative effects of degrading transport activities on society [9]. Rail transport, compared to road transport, is characterized by lower energy consumption per unit of transport work performed and lower emissions of harmful gases, which make it an important tool for the decarbonization of transport [10]. Road transport is responsible for high specific CO2 emissions, safety risks, high levels of land absorption, noise emissions, and the problem of congestion [9,11]. As a result, this mode is characterized by the highest level of generated external costs, while satisfying the largest share of needs in the field of inland cargo transport (77.8% of transport work performed in the EU-27 countries in 2022 was carried out by road transport [12]). Decisions on the choice of rail for freight transport result primarily from its technical and operational features, such as high transport capacity, low unit operating costs, high energy efficiency, and reliability (compared to road transport) [13,14].

The transport services provided are the engine driving economic processes; therefore, solutions are being sought that will reduce the negative impact of transport while not reducing the competitiveness of the economy by meeting transport needs. The change in the modal structure of transport aimed at preventing asymmetry by transferring loads from road transport to rail and inland waterway transport under the assumption of the shift paradigm is of key importance [15]. The need to shift loads from road to rail transport is also emphasized in EU legislation. The European Commission [16] recommends that by 2030, 30% of road transport of goods moved over a distance of more than 300 km should be transferred to alternative modes of transport. By 2050, it should be over 50%. Such policy-making is intended, among other things, to aim at promoting rail transport by ensuring equal conditions of competition in terms of setting prices in transport, fair conditions of access to the rail market, the development of railway infrastructure determining accessibility to this mode of transport, and improving multimodal integration [17]. This is also confirmed in the literature on the subject, which supports this position, emphasizing the need to transfer loads from road to rail transport and pointing to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) emissions as one of the most important benefits [18].

Many countries, particularly those in the European Union, have prioritized rail freight transport deregulation as a means of improving transport efficiency, competitiveness, and sustainability. This approach includes deregulating the market to increase competition, privatizing state-owned companies, and decreasing corporate regulations. The goal is to increase service quality, reduce costs (including energy intensity), and shift freight transport from road to rail to lessen environmental effects. Liberalization can be viewed from different perspectives:

- Sustainability and environmental impact: liberalization is viewed as a way to promote sustainable transport by boosting rail competitiveness while decreasing the negative environmental implications of road freight [19,20]; the construction of multimodal transport networks is necessary to accomplish the aims of sustainable transport systems [20];

- Efficiency and enhancements in performance: liberalization may contribute towards greater technical effectiveness and enhanced performance in rail freight transport, evidenced by the rising transported volume of goods and also the increasing passenger flow [21,22,23]; rail freight transport efficiency varies greatly between geographical areas, and liberalization may not consistently boost efficiency across all countries [22];

- Innovation and market competitiveness: to remain competitive in a liberalized market, national carriers must innovate in areas such as intermodal terminals and digitalization [19].

Liberalizing rail freight transport has the potential to improve the transport sector’s efficiency (in all dimensions, especially in the energy intensity), competitiveness, and sustainability. While it can result in considerable performance improvements and cost savings, the success of liberalization efforts is dependent on resolving market dominance problems and ensuring that infrastructure and regulatory frameworks promote fair competition. For success in a liberalized market, national carriers must innovate and make strategic modifications. In general, liberalization is a potential strategy for shifting freight transport from roads to rail, lowering environmental consequences, and boosting sustainable transport systems.

Given the high dependence on energy supply, the limited supply of transport services (after pandemic COVID-19), disrupted supply chains, the current geopolitical situation, and the economy and transport’s reliance on energy, it is possible to conclude that rail transport plays an essential role in minimizing energy consumption. The limited supply of road carriers may lead to a shift from road toward rail transport, but this option is contingent on the removal of infrastructural constraints and the introduction of supportive legislation [24,25]. The increased demand for rail services, combined with the need for robust infrastructure and adaptive logistics strategies, demonstrates the complexities of managing freight transport in a dynamic environment (market shocks, volume fluctuations, on the one hand, and the need to maintain supply chain efficiency, on the other) [25,26].

The authors filled the research gap by identifying multidimensional cause-and-effect relationships of the energy intensity of exports of goods by rail transport (energy consumption by this transport per 1 USD of GDP) in the context of liberalization of the rail market. Knowledge of these relationships is crucial in programming and implementing EU transport policy.

This article is organized into five sections. The first section is the introduction. The second section discusses the development and liberalization of the rail market through the prism of European Union integration, as well as a reference to the shift paradigm in the context of minimizing the energy consumption of transport (including rail). Section 3 presents a description of the data and the research techniques used. Section 4 presents the research results and discussion with policy recommendations, with particular attention paid to the panel model of energy intensity in rail transport. The last section ends with conclusions, directions, and conditions for improvement.

2. The Development of the Rail Market in the Context of EU Integration and Legal Regulations

2.1. Historical Outline of European Union Integration

After the Second World War, the countries of Western Europe began to quickly rebuild their economies thanks to the financial assistance program of the United States—the European Recovery Program [27,28,29]. The condition for granting support was the liberalization of the economy in the countries covered by the program. In this way, economic aid turned out to be a powerful tool to counter the growing influence of the Soviet Union in Europe, which offered a radical alternative to capitalism [30]. The “Iron Curtain” not only divided Europe into two political and ideological camps but also economic ones. After World War II, people’s democratic states began to rebuild their socio-economic structure through industrialization, which meant the development of industry at a rate much faster than other sectors of the economy, at the expense of agriculture and services. Following the Soviet example, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe focused on the development of heavy, machine, and electrotechnical industries, based on their internal resources of raw materials and capital (economic autarchy). The socialist economy was extensive. It was a centrally directed economy. It was characterized by high capital and energy consumption in production [31]. Market instruments were not used for economic development. Industrialization resulted in a gradual degradation of the natural environment.

Immediately after the war, many Western European politicians began to put forward proposals for close political and economic cooperation between the countries west of the Elbe. Political integration meant a union of sovereign states pursuing a common policy in the areas most important to them, and the condition for its success was the actual or potential complementarity of the economic structures of states [32]. In 1946, the Customs Union between the Benelux countries was introduced [33,34,35]. In 1948, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation was established, which was made up of 16 countries participating in the Marshall Plan [36]. In 1948, the Treaty on economic, social, and cultural cooperation and collective self-defense, called the Brussels Treaty, was concluded. Signed by five European countries (Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Great Britain), it created the Western Union (since 1954 the Western European Union).

On 9 May 1950, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of France, Robert Schumann, as a result of the conflict between West Germany and France over the Statute of the Saar Basin, presented a plan to strengthen economic cooperation consisting of combining the coal and steel industries of France and Germany and submitting them to the control of a supranational body, which was intended to control arms and conflict prevention. Schumann outlined a vision of a common basis for economic development as the first stage of a European Federation (“Fédération Européenne”) [37]. Economic cooperation was to become the basis for political stabilization and the peaceful coexistence of European countries. On April 18, 1951, the European Coal and Steel Community was established in Paris, which included France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg [38]. It was an example of sectoral integration, as only a strictly separated area (coal and steel industry) was subject to unification. A common market for coal, iron, and steel was created between the contracting states. The institutions of the Community were also established, consisting of the High Authority, the Common Assembly, the Special Council of Ministers, and the Court of Justice [39].

The next stage of economic integration was the creation under the Treaties of Rome (1957) of the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community, the aim of which was the harmonious economic development of Western European countries and a long-term economic development program in the form of a common market, free movement of goods, people, capital and services, cooperation in industrial and transport policy, a uniform tax policy, creating the necessary conditions for the emergence and rapid development of the nuclear industry, to raise the standard of living in the Member States and to develop exchanges with other countries. In 1965, a fusion treaty was signed (entered into force in 1967), which established a single Council and a single Commission of the European Communities. In 1960 (the Stockholm Treaty), it established the Free Trade Association, which allowed the establishment of a free trade zone. In 1973, the United Kingdom, together with Denmark and Ireland, became a member of the European Communities, and in 1981, Greece did as well. In 1985, the Single European Act was adopted—an international agreement that entered into force in 1987 and established a common internal market of the Member States, and a common economic, scientific, and technological development policy. In the meantime, in 1986, Spain and Portugal joined the communities. In 1992, the European Economic Area was created—a free trade area and a common market between the contracting entities. On 7 February 1992, the Treaty on European Union (Treaty of Maastricht) was signed and entered into force on 1 November 1993 [40]. In 1995, Austria, Finland, and Sweden joined the European Union. In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam was adopted. Signed in 2001, the Treaty of Nice reformed the EU institutions and adapted the European Union to enlargement by the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The accession negotiations of these countries were officially launched on March 31, 1998. The socio-economic crisis that affected the communist countries in the 1980s showed the need for cooperation and tightening of ties between the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the countries of Western Europe. The collapse of the Soviet Union finally ended the division of Europe into two political and economic blocs and, as a result, enabled integration with European structures. As a result of the political transformation, the former socialist countries were rapidly switching to a market economy. There have been privatization processes, de-monopolization of the market, and liberalization. On 1 May 2004, Poland, together with Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Hungary, joined the European Union [40]. The adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon (2007), which entered into force on 1 December 2009, marked a watershed moment in the European Union’s ongoing integration process. It attempted to strengthen the EU’s efficacy, coherence, and democratic legitimacy while also dealing with the problems provided by globalization and economic crises [41,42]. It revised prior treaties, specifically the Treaty on the European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community, to expedite decision-making and improve institutional performance [43,44]. The Treaty of Lisbon was meant to create a stable foundation for confronting economic and political problems, and it marked a significant step forward in Europe’s ongoing and irreversible integration process [42,44]. And then, on 1 January 2007, Bulgaria and Romania joined the Union, and on July 1, 2013, Croatia joined. In the 2016 referendum, the people of Great Britain voted to leave the EU. On 21 January 2020, Great Britain left the European Union (Brexit). Currently, candidates for the community are Albania, Montenegro, Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, Moldova, Ukraine, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

All integration processes, including the political and economic sphere, enabled the economic activation of Central and Eastern Europe. They led to the unification of the market and the development of a coherent economic policy. Modern industrial production and export of industrial products have become the driving force of the economy of a single European market.

2.2. The Process of Liberalization of the Rail Services Market in EU Transport Policy

Transport is an important element of the European integration process. Its development ensures community cohesion and is one of the basic factors in the development of the European Union and also provides the opportunity to equalize the socio-economic level of particular EU countries or regions.

The importance of rail transport in Europe and around the world has been changing, which was mainly due to the rapid development of road transport and individual motorization. Railways ceased to be the dominant mode of transport for goods and passengers in the early 1950s, and that declining trend persisted throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as evidenced by transport work (tonne-kilometers) [45]. The decline was particularly noticeable in freight transport—in the 1980s in Western European countries, this transport was constantly decreasing.

Before accession to UE, in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland, the share of railways in the transport market was significant, which was due to, among others, a different socio-economic system, low quality of road infrastructure, or poor development of road transport services. However, after the political transformation in Poland (1989–2004), a rapid decline in domestic and international transport began, caused primarily by a sharp decline in material production, as well as a decline in the real incomes of the population and an increase in unemployment. The collapse of Poland’s trade with the countries of the former USSR was also important.

The phenomenon of the declining importance of railways in transport became the subject of discussion, including in political circles of the community, especially when the negative effects of such a rapid development of road transport and motorization were increasingly noticed [46]. With the creation of a common EU transport market, the dominance of road transport deepened even more. Therefore, actions were taken in the community to change this state of affairs, which were articulated in the documents defining the EU transport policy, i.e., the so-called transport white papers.

According to the White Paper of 1992, the common transport policy was to consist of integrated actions, including in the following areas [47]:

- Strengthening the proper functioning of the internal market,

- Elimination of industry imbalance through activities aimed at eliminating factors distorting intra- and inter-industry competition,

- Creating a coherent trans-European network,

- Implementation of technical standards for environmental protection,

- Increasing safety in all modes of transport.

The next White Paper 2001 “European Transport Policy for 2010: Time to Decide” [48] was the result of an analysis of problems and challenges related to European transport policy, especially in light of the upcoming enlargement of the European Union to include a group of Central and Eastern European countries. The discussed White Paper noted threats related to the ongoing increase in transport volumes in European Union countries. To overcome these trends and contribute to the creation of an economically efficient, but at the same time, ecologically and socially responsible transport system, the Commission presented a package of several dozen instruments and measures of the common transport policy. The basic objectives and activities of the common transport policy are included in the following areas [49]:

- Changing the proportions between modes of transport, including improving the quality of services in road transport, and concerning rail transport, the so-called revitalizing of the railways (liberalizing access to the provision of freight transport on a separate Trans-European Rail Freight Network and extending it to the entire network for international transport, guaranteeing rail safety, optimizing the use of infrastructure, improving services) and the postulated integration of individual modes of transport,

- Eliminating bottlenecks in transport infrastructure, including verification of guidelines for TEN-T, development of multimodal corridors with priority for freight traffic, creation of a high-speed passenger rail network, development of traffic management systems, and ensuring an appropriate level of financing for these investments,

- Placing transport users at the heart of transport policy, including improving transport safety (reducing road deaths, protecting vehicle users, controls, penalties, etc.) and internalizing the external costs of transport (gradual introduction of infrastructure user charges, ensuring the interoperability of the road charging system, improving the infrastructure valuation system, harmonizing fuel taxes),

- Steering the globalization of transport, including improving the efficiency and coherence of existing infrastructure, developing the railway network, strong EU participation in international bodies, and developing its satellite navigation system (Galileo).

The White Paper 2011 “Plan to create a European Transport Area—striving to achieve a competitive and resource-efficient transport system” is a document defining the currently implemented European Union policy in the entire transport sector, including the rail sector [16]. This document is strategic; hence, the EU transport policy is presented from the perspective of 2020–2030, and even has references to 2050.

The general assumptions on which the development of the transport sector in the EU is to be based include the following [50]:

- Improving the energy efficiency of vehicles in all modes of transport resulting from the systematic introduction of fuels and propulsion systems consistent with the principle of sustainable development,

- Optimization of the operation of multimodal logistic chains,

- More efficient use of rolling stock and infrastructure, thanks to the use of more effective traffic management and information systems as well as advanced logistics and market measures.

The implementation of the above assumptions and objectives is to lead to the creation of a single European transport area, which should facilitate the movement of citizens and goods, reduce its costs (including external costs), and ensure the sustainable development of European transport [51].

Since 1991, reforms have been undertaken in the rail sector, the previous functioning of which in the Member States was based on natural network monopolies and a lack of internal competition. A practical manifestation of the implementation of the assumptions of the EU transport policy was the adopted and implemented legal regulations relating to both the entire transport and its modes. Regarding rail transport, legal regulations were adopted under the so-called railway packages. The regulations from the 1990s are conventionally referred to as the “zero railway package”, which contains the following: Directive 91/440 [52], Directive 95/18 [53], Directive 95/19 [54], and Directive 96/48 [55]. In 2001, the first railway package was adopted, which included the following directives: 2001/12 [56], 2001/13 [57], 2001/14 [58], and 2001/16 [59]. The second railway package of 2004 included the following directives: 2004/49 [60], 2004/50 [61], 2004/51 [62], and Regulation 881/2004 [63]. The 3rd railway package (2007 and 2008) included the following directives: 2007/58 [64], 2007/59 [65], 2008/57 [66], 2008/110 [67], and regulations 1370/2007 [68] and 1371/2007 [69]. In 2012, it had the so-called rework of the first railway package, which meant a thorough amendment of the regulations and their consolidation through the adoption of Directive 2012/34 on the creation of a single European railway area [70]. The latest 4th railway package from 2016 is a set of six legal regulations divided into two pillars: technical and market. The technical pillar includes Directive 2016/797 [71], Directive 2016/798 [72], and Regulation 2016/796 [73]. The market pillar includes the directive 2016/2370 [74], Regulation 2016/2337 [75], and Regulation 2016/2338 [76].

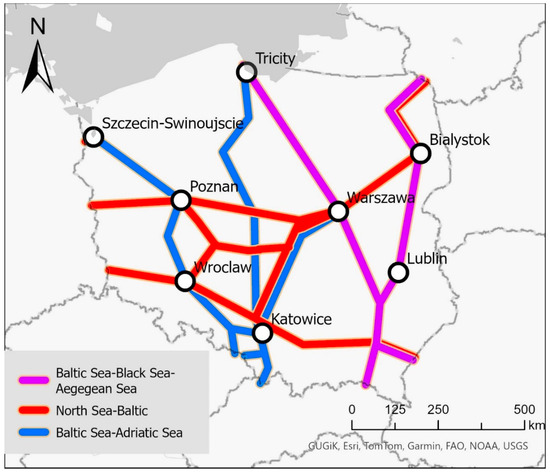

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Krajowy Plan Odbudowy i Zwiększenia Odporności—KPO) for Poland of 2022 is in line with the EU common transport policy and aims to aid the country’s economic and social rebuilding while also increasing competitiveness following the COVID-19 pandemic. As part of green and intelligent mobility policy, efforts are being made to reduce the emission intensity of the transport sector by shifting from road to rail transport (which is becoming more appealing) and boosting multimodal transport. It is proposed to modernize 478 km of railway lines, 300 km of which will comply with Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) standards, with a budget of roughly EUR 2.4 billion [77] (TEN-T transport corridors for rail freight transport are shown in Figure 1). Furthermore, the development of cargo hubs is a significant endeavor. The largest transport investment in this program is to be the Centralny Port Komunikacyjny (CPK; Solidarity Transport Hub) [78].

Figure 1.

Core TEN-T network for rail transport in Poland. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by TENtec Geographic Information System, Mobility and Transport, European Commission and ArcGIS Living Atlas, Esri. Visualization developed using ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.0.2 software.

Analyzing changes in regulations relating to rail transport, it can be concluded that legislative activities are consistent with the guidelines of transport policy aimed at revitalizing, standardizing, and simplifying the functioning of the rail services market and increasing the competitiveness of EU rail transport. It is also worth noting that an important aspect of the adopted regulations is those regarding technical issues, including the development of European freight corridors in the TEN-T and the interoperability and safety of the rail system (including infrastructure, rolling stock, and rail traffic control systems, and also in terms of energy consumption of transport).

2.3. Minimizing the Energy Consumption of Transport in the Context of the Shift Paradigm

Among various studies, the evaluation of programs related to the modal shift from road to rail transport, whose aim is to reduce energy and CO2 consumption in freight transport, is particularly important [10,79,80,81,82]. The European Union’s policy aimed at creating the European Single Market has always been closely related to environmental protection issues. The currently implemented European Union environmental protection policy (i.e., European Green Deal [83]) sets one of the most important goals for all modes of transport, which is to reduce their energy consumption. This applies to infrastructure, power systems, rolling stock, and traffic organization and management. It must be remembered that lower fuel consumption per unit of transport work has a huge impact on reducing the emission of many toxic compounds into the atmosphere. At the same time, designers are trying to find favorable solutions in the field of new drive concepts using alternative fuels, which is consistent with the European Union guidelines in the field of EU ecological policy [83]. One of the main goals of the EU’s transport policy is continuous action to shift passenger and freight transport from road to modes that have a less negative impact on the natural environment, including rail transport. The promotion of intermodal transport is part of this policy.

An equally important element of the EU transport policy is activities aimed at increasing the efficiency of particular modes of transport. The actions concern both the reduction in emissions of harmful substances into the environment [84,85], and the reduction in energy consumption in a given mode of transport [86], but the point is not so much about minimizing the consumption of fuel or traction energy, but about reducing its consumption per unit of transport work performed (e.g., in the case of rail freight transport—constant striving to increase the length of trains and/or their gross weight). The issue of energy consumption is multidimensional, including not only factors related to the level of traction fuel or traction energy consumption but also other factors. This includes, among others, such elements as the structure of rolling stock (wagons and traction) [2] or the type of traction vehicles and their drive [2,84,87] (e.g., electric—including cells [88,89,90], hybrid [91], hydrogen [92,93] and others), as well as issues of railway infrastructure [87,94,95], rail traffic control systems [95,96,97], and even the organization of rail traffic and transport [90,95,96,97], or the ability to properly conduct rolling stock (eco-driving [98]). The sources of energy consumption in rail transport are, on the one hand, technical, and on the other are organizational, social, environmental, and economic, which favor the adaptation of the system, management, and global development of transport [99]. Various studies have been conducted on the impact of the shift paradigm using rail transport on the energy intensity of the transport sector, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Expected effects of the shift paradigm for transport decarbonization—a literature review.

The liberalization of the rail market in the EU has aided the adoption of the shift paradigm by boosting market share in rail freight services and promoting competition. However, the influence on modal shift was moderate, implying that additional policy measures may be required to achieve more substantial outcomes [103].

The next part of this article analyzes the impact of the liberalization of the railway market on the energy intensity of rail transport and identifies multidimensional cause-and-effect connections between the energy intensity of rail transport and selected economic and transport indicators.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

This study used secondary data from the databases listed in Table 2. The time range covered the years 2010–2020. At the same time, it was the widest scope possible to examine, taking into account the integrity and completeness of the data. The data were structured into panel data, yielding 231 observations. The structure and scope of data determined the export destinations of goods from Poland. The 21 largest directions for years 2010–2020 were selected: Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Brazil, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Morocco, Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom. The analysis focused only on rail transport, the data were analyzed and included only for this mode, and in the case of intermodal transport (requiring the integration of another mode of transport), only sections of routes performed by rail transport were taken into account (see Figure 1 and Figure 4). This study excluded other geographical export directions due to their small share in trade and the summary data for other countries.

Table 2.

Description of the data used in this study in alphabetical order.

3.2. Methodology

The research problem was formulated in the form of three research questions:

- Does the liberalization of the EU transport market and the implementation of a sustainable transport policy contribute to minimizing the energy consumption of rail transport?

- Does the pursuit of economic growth allow for reducing the energy intensity of goods exported by rail transport in global trade?

- Is there a justified paradigm for shifting long-distance freight transport from roads to rail?

Based on the above questions, the authors formulated the following research hypothesis: liberalization of the EU transport market, aimed at creating a single European transport area and the convergence of Member States in the implementation of sustainable development goals, favors minimizing the energy consumption of rail transport without harming the economies and the movements of exported goods in worldwide trade.

The aim of this article is to set directions for rationalizing the energy consumption of rail transport in global exports of goods without harming freight movement and the economy.

To calculate the energy intensity of exports of goods by rail transport, the first step was to recognize the data structure and extract information from it separately on the energy intensity of diesel and electric traction [in MJ/thousand tonne-kilometers gross] and gross transport performance separately for diesel and electric locomotives. Based on these data, it was possible to estimate the aggregate energy consumption of diesel traction and electric traction using the index method. Data on total transport and the structure of rolling stock were necessary to decompose two measures of energy intensity of rail transport in net terms [MJ/t] from the gross approach. The aggregated energy consumption by diesel and electric traction for various geographical directions of goods exports was related to the GDP of countries importing goods from Poland. These operations allowed us not only to clear the data from the unladen weight of the rolling stock but also to relate this value to the country’s economic growth. Finally, the values were converted into a standardized unit such as Mtoe/USD (Mtoe/PPP in current USD). Further in this article, the term energy intensity of rail transport in the export of goods is understood through the prism of energy consumption by mode of transport in relation to the GDP of the importing country.

The level of lagging in achieving the European Union’s goals for reducing energy intensity (as an outlier) is an unnominated variable. It was calculated based on the Mahalanobis distance [118,119], which considers the structure of correlations between variables and allows for the identification of outlier observations. Because the covariance matrix weights it, it does not require prior standardization and will automatically adjust the scale of the variables. The construction of this variable took into account information about the membership in the European Union and energy consumption per volume of exported goods for a given country (net energy intensity), taking into account the above requirements in the calculation (decomposition of gross from net). The lower the ratio of unit energy consumption per export volume, the better from the point of view of implementing sustainable development assumptions.

The analysis began by calculating descriptive statistics for all analyzed countries that are Poland’s trading partners. This was necessary to present the background. The energy consumption of goods exported by rail transport was presented using the cartogram method. Finally, a panel model with random effects was constructed to describe the relationship (Equation (1)):

where

- —energy intensity of goods exported by rail transport from Poland to importing countries i in year t related to their GDP

- —volume of transport of goods exported by rail transport from Poland to the importing country i in year t

- —average transport distance of 1 tonne of goods exported by rail transport from Poland to the partner country (importer) i in year t

- —gross domestic product in the importing country i in year t

- —constant

- —structural parameters

- —spatial autoregressive parameter

- —random effects

- —random component

Panel models with random effects (RE) are used in multilevel and time-cross-sectional analyses. Despite their wide use, there are the following limitations to their use:

- Problem with the correlation of a lower-level variable with higher-level residuals [120],

- Assuming that random intercepts are normally distributed, which may introduce negligible errors, but failure to account for random slopes may lead to significant standard errors [121],

- Random-effects models may be susceptible to errors resulting from the intentional omission of important variables [120,122],

- Random-effects models may misattribute between-unit heterogeneity with respect to the inefficiency measure [120,123].

It is important to be aware of these pitfalls and to be able to use appropriate correction methods after verifying the model in terms of its properties.

The properties of the model were examined in many tests. The most important was the Hausman test because its results confirm that a model with random effects is better than with fixed effects. The Wald test again allowed for the joint significance of the studied variables in the model and this case confirms the causality of the energy consumption of rail transport. The Breusch–Pagan test allows the researcher to verify the occurrence of individual effects.

Table 3 provides an overview of other selected techniques used to analyze the energy intensity, energy consumption, and energy efficiency of rail freight transport. The scope of this research is diverse because the issue of reducing energy consumption can be studied in various contexts, as indicated in the previous section of this article. In addition, the main directions and limitations of research were indicated. The research proposed in this article is innovative, although subject to all the methodological rigors described above. So far, it has not been undertaken in a similar context using the same methodological techniques. Therefore, its framework was proposed.

Table 3.

Selected techniques used to analyze energy consumption, energy intensity, and energy efficiency in rail freight transport (various approaches).

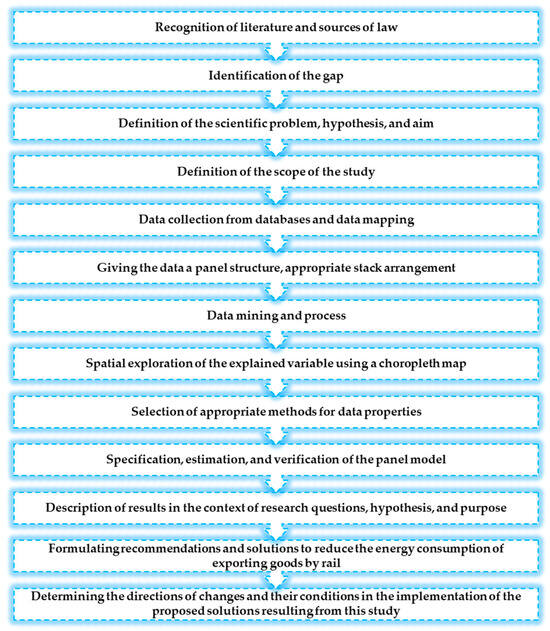

Figure 2 presents the framework of the authors’ research procedure (methodology).

Figure 2.

The framework of the authors’ research procedure (methodology). Source: own elaboration.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Findings and Explanations

Table 4 presents selected descriptive statistics of the analyzed variables, i.e., the mean, median, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation.

Table 4.

Selected summary statistics.

As Table 4 shows, all analyzed variables were characterized by very high variability in the examined time range. Based on the coefficient of variation, i.e., the quotient of the standard deviation to the mean, it can be concluded that the studied countries and years were characterized by very large differences in terms of all analyzed statistical features. In other words, they were not homogeneous. The greatest differences were recorded for the energy consumption of rail transport (approx. 262%), GDP (approx. 188%), and rail transport performance (approx. 183%). Slightly lower values were recorded for the remaining variables. This will be important for the model, as it can be assumed that the model will have individual and random effects.

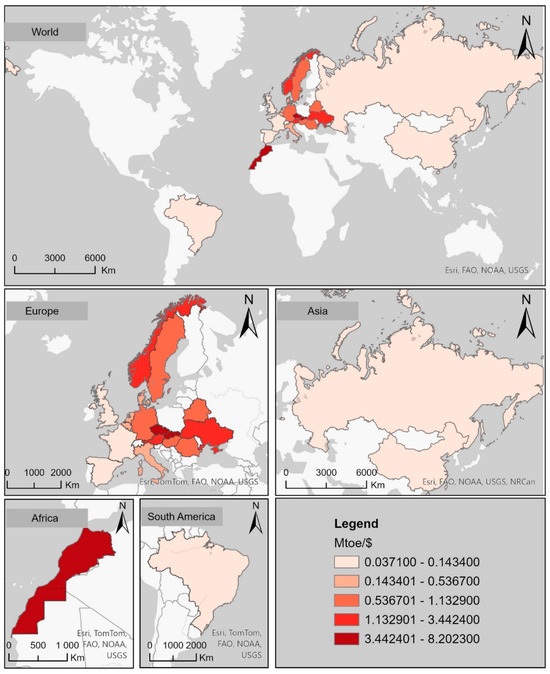

Figure 3 additionally illustrates the average energy intensity of exports of goods by rail transport in 2010–2020 using the cartogram method, which takes into account the spatial diversity of the variable explained in the model.

Figure 3.

Average annual energy intensity of goods exported from Poland by rail transport in 2010–2020 (in Mtoe/USD). Note: Energy intensity classes are presented using the Jenks natural breaks classification method. Source: own elaboration based on database from Table 2 and data provided by ArcGIS Living Atlas, Esri. Visualization developed using ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.0.2 software.

The most energy-intensive directions for exporting goods by rail transport (in some cases by intermodal transport, but in the analysis, we only refer to sections served by rail transport) from Poland are Morocco (8.2023 Mtoe/USD), the Czech Republic (7.0729 Mtoe/USD), and Slovakia (5.6716 Mtoe/USD). This means that generating 1 USD of GDP thanks to the import of goods by partner countries required energy consumption by rail transport of 8.2023 Mtoe, 7.0729 Mtoe, and 5.6716 Mtoe in Morocco, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, respectively. The least energy-intensive export directions were China (0.0371 Mtoe/USD), Brazil (0.0718 Mtoe/USD), and France (0.0850 Mtoe/USD). Apart from the above-mentioned most energy-intensive countries, three more recorded energy intensity of exports of goods by rail transport above the average in the surveyed countries and in the time range: Austria (3.4424 Mtoe/USD), Norway (2.2692 Mtoe/USD) and Ukraine (2.0337 Mtoe/USD). However, other countries recorded below average energy consumption of this transport. The explanation of the variability of the energy consumption of exports of goods by rail transport and its causality is presented by a panel model (Table 5).

Table 5.

Panel model of energy intensity of export of goods by rail transport with random effects.

Based on the model presented in Table 5, it can be clearly stated that all analyzed variables were statistically significant. The Wald test for the joint significance of the studied variables in shaping causality also allows for the conclusion that transport performance for export goods by rail transport, economic growth, the average transport distance of 1 tonne of goods exported by rail transport, and the level of lagging in achieving the European Union’s goals for reducing energy intensity (as an outlier) are the reasons for the energy intensity of exporting goods by rail. The model has a very high cognitive value, as it explains approximately 99% of the variability in the energy consumption of goods exported by rail transport from Poland. The results of the Hausman test did not allow us to reject the hypothesis that the random-effects model is better than the fixed-effects model, which also explains the choice of this type of model in the exploration of cause-and-effect relationships.

In the analysis of the cause-and-effect relationships of the energy intensity of rail transport (energy consumption by this mode of transport in relation to GDP), several conclusions can be drawn as follows:

- With an increase in transport performance by 1%, the energy intensity of exporting goods by rail transport increases by 0.9934%, ceteris paribus (estimation error—understood as a deviation of approximately 1/100 of this value). This flexibility is not directly proportional, but it indicates that transport work reflects the energy consumption of this type of transport. This means that transport work stimulates economic growth on the one hand and energy consumption by this type of transport on the other.

- An increase in GDP by 1% causes a decrease in the energy intensity of exports of goods by rail transport by 0.9885%, ceteris paribus. Such a change reflects technological progress or transport technology but also informs that for each 1 USD of GDP generated, rail transport consumes less and less energy.

- An increase in the average transport distance of 1 tonne of goods by 1% contributes to a decrease in the energy intensity of rail transport by 1.0076%. This means that long-distance rail transport of goods brings increasingly greater economies of scale.

- The more a country deviates from the sustainable transport policy (here understood by EU membership and respect for the developed provisions and goals), the higher the energy consumption. The level of lagging in achieving the European Union’s goals for reducing energy intensity (as an outlier; measured by the Mahalanobis distance) increases by 1%, and the energy intensity of exporting goods by rail transport increases by 0.0662%. It also confirms that the creation of a single European transport area, which eliminated barriers between national systems and allowed the integration of processes and international multimodal operators, reduced the total energy intensity of rail transport. The degree of unification of regulations and technical conditions facilitates the movement of goods and reduces energy costs. The value of this parameter as a hidden variable could be influenced by models of the division of infrastructure management and transport activities of rail transport (separation, integration, hybrid model).

- The average distance has the greatest impact on the energy consumption of rail transport, but transport performance and GDP also have a significant impact. They can be considered as a triad of causative factors for the energy consumption of export goods transported by rail.

The model also explains that shifting the export of goods from road to rail transport over long distances takes place without harm to the economy and goods movement. Moreover, there is a decoupling between energy consumption by rail transport and economic growth.

4.2. Discussion on Strengthening the Position of Rail Transport to Reduce Energy Intensity and Recommendations

The energy consumption of exporting goods by rail is influenced by the transport technology used: mass-distributed and intermodal. In commercial terms, bulk transport is mainly so-called full train shipments, which are transported with one consignment note. However, two technologies for transporting goods by rail dominate: dispersed transport (by wagons) and full-train transport (compact, shuttle), which generate different costs (including energy consumption) and transport times. Wagon transport usually requires more time to complete, which involves stops at intermediate stations and train changes. Full-train transport allows the elimination of unnecessary operations (including marshaling of wagons), but the choice of technology depends on the rail carrier. If a carrier operates throughout the entire railway network, distributed transport technology may be a more interesting option for it in terms of revenues [130]. Taking into account geographical criteria and technology, international transport can be carried out by regular trains (made of single wagons or several wagons), compact (shuttle) regular or express trains in mass transport between the sender and recipient of goods, or compact intermodal trains (transport of containers, semi-trailers, swap bodies) in express system transport [130]. The energy intensity of rail transport is also significantly influenced by the same demand and supply factors that stimulate the demand for rail freight transport. On the demand side, there are factors such as the following [130,131,132]:

- Spatial distribution of economic activities,

- Economic situation—with better economic conditions, the demand for transport increases (actual demand also increases, and the gap between actual and potential demand shrinks),

- Specialization in production—greater demand for the transport of semi-finished products and components,

- Organization of trade and product distribution,

- Intensity of foreign trade—a higher share of exports in GDP causes an increase in demand for international transport,

- Production technologies—material-intensive technologies, stimulation of growth in transport,

- Branch structure of the economy,

- Degree of cargo containerization,

- Export and import structure,

- Level of infrastructure investments.

On the supply side, the following can be distinguished [130,132]:

- Quality of railway infrastructure, which determines the speed of cargo movement, timeliness, and punctuality,

- Service potential of rail-substitutable modes of transport,

- Price competitiveness of other carriers,

- Spatial accessibility of loading points and stations,

- Equipment that determines the processing capacity of port, border, and rail terminals (rail-ports),

- Having a reserve of transport capacity on specific routes.

Rail freight transport plays an important role in EU transport policy. Nevertheless, it must adjust to shifting demands and consumer needs to preserve and increase its market share, especially in light of the competition of other transport modes, e.g., road transport.

Among the key points of discussion, a special place is occupied by issues regarding the conditions for the development of rail transport in the European Union, namely the following:

- Regaining market share will require rail freight transport to innovate and adapt to changing circumstances, such as the increase in containerized goods, by cooperating with partners in the transport chain and providing door-to-door services [133].

- The European Union’s policy objectives seek to achieve a substantial transition (shifting) from road to rail transport, with optimistic projections indicating that rail freight demand might double by 2050 [134]. To accommodate the anticipated doubling of freight traffic and optimize the competitive advantage of rail freight, cooperation across European railways is vital [135].

- High-speed rail freight transport may be a feasible alternative for low-density, high-value cargo, soaking large CO2 reductions, although it is currently more costly than road transport [133].

- To grow, rail freight transport in the EU should enhance the quality of its services, implement integrated supply chain strategies, and save costs by implementing heavier and longer trains, wider loading gauges, faster average speeds, and more efficient use of wagon space [136].

- Due to asymmetries in both intra- and intermodal competition, rail freight has doubly imperfect competition, which calls for regulatory attention to entry obstacles and market concentration [135].

- Rail freight has to raise capacity through improved planning, ICT systems, and infrastructure upgrades to draw clients and meet EU mode shift objectives. It also needs to provide competitive pricing and higher service quality [137].

- The competitiveness of rail freight depends on innovations like digitalization, optimization of the management of rail traffic (ERTMS), the ability to serve the new technology of intermodal transport, and the development of intermodal terminals network.

- Optimizing the railway network and using approaches like the critical path method (CPM) and critical chain method (CCM) are two ways to make rail freight a greater competitor [138].

- The integration of European rail transport systems, as included in the TEN-T extension policy to Ukraine and Moldova, requires the development of technologies to facilitate the provision of services between systems with different track gauges.

- The development of rail freight transport is contingent upon the deployment of logistic solutions and pro-competition regulations [139].

- The expansion of rail freight in the EU should be aided by deregulation, market liberalization, addressing the significant roles played by large corporations, and government action [135]. Further and deeper deregulation, improved planning, ICT systems, an integrated supply chain strategy, and a quicker establishment of rail freight corridors are all necessary for the development of rail freight transport in the EU [137].

For rail freight transport in the European Union to thrive, it must become more customer-focused, sensitive to market developments, and attractive in pricing. This necessitates higher service quality, a greater capacity of infrastructure, and technological and logistical improvements. Regulatory measures must resolve market imbalances and encourage collaboration among operators. The successful execution of these initiatives might result in a considerable shift from road to rail, under EU policy objectives, leading to a more environmentally friendly and productive transport sector. Table 6 contains proprietary strategies promoting energy reduction using rail transport.

Table 6.

Solutions for reducing energy use by boosting rail transport.

Such recommendations may help the EU drastically reduce the energy intensity of the transport sector. Energy intensity will be decreased and the EU‘s larger environmental and sustainability goals will be met by promoting rail transport through enhanced services, better infrastructure, financial incentives, and institutional support.

Reducing energy intensity and avoiding negative environmental effects require that rail transport play a larger role in the export of goods within multimodal transport networks. The aim of integrating different modes is to improve the role of rail transport in intermodal freight networks. Increasing the position of rail transport as a result of market liberalization can be achieved through the following:

- Economic and spatial integration: the EU’s integration and economic advancements in the importing partners serve to lower the energy intensity of rail transport for exports [99],

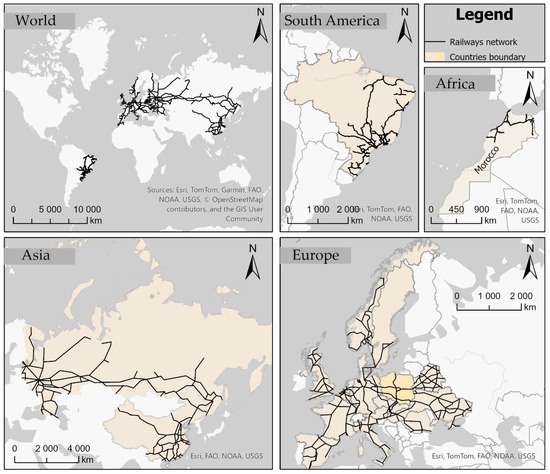

- Intercontinental freight transport: rail transport may save CO2, NOx, and PM10 emissions when it replaces maritime transport on some transcontinental freight routes (Figure 4), but careful logistical planning is needed [149],

Figure 4. Intercontinental Transport Network for rail freight transport for studied countries. Note: the country of export (Poland) is marked in a more saturated color. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by ArcGIS Living Atlas, Esri. Visualization developed using ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.0.2 software.

Figure 4. Intercontinental Transport Network for rail freight transport for studied countries. Note: the country of export (Poland) is marked in a more saturated color. Source: own elaboration based on data provided by ArcGIS Living Atlas, Esri. Visualization developed using ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.0.2 software. - Facilitating terms for multimodal transport in particular sectors: the use of strategic logistics models and technological advancements is crucial in certain sectors to facilitate multimodal rail-road transport [150],

- Energy-saving strategies in rail systems: enhancing sustainability in rail networks may be achieved even in situations when rolling stock is unavailable by implementing energy-saving techniques like recovery devices and appropriate drive profiles [151],

- Upstream goods consolidation: reducing the requirement for de- and re-consolidation, boosting container usage, and saving CO2 emissions by consolidating commodities upstream and utilizing rail-based intermodal transport downstream [152],

- Optimizing the loading of containers: at rail-truck intermodal terminals, effective container loading procedures may drastically cut down on handling time, rearranging, and energy usage [153],

- Using double-track railways: double-track railways can convey freight more often while using less fuel and emitting less carbon monoxide due to the greater capacity of such a line [154],

- High-speed rail impact: infrastructure for high-speed rail encourages technological advancement, industry agglomeration, and lower general energy usage, particularly in outlying cities [155].

To sum up, multiple solutions can be implemented to enhance the role of rail transport in the export of goods within intermodal networks and decrease energy intensity. These include streamlining the process of loading containers, consolidating commodities upstream, making use of double-track railways, leveraging high-speed rail infrastructure, substituting rail for maritime transport on specific routes, and putting energy-saving measures into practice. Furthermore, industry-specific technical advancements and economic and spatial integration are critical to improving the sustainability and efficiency of rail transport in multimodal networks.

5. Conclusions

The presented research allowed for the analysis of cause-and-effect relationships between the energy consumption of exports of goods by rail transport due to the economic situation of the trade partner country Poland (economic growth of the importing country), transport performance determining transport capacity, average transport distance (geographical proximity, spatial distribution of importing countries), and level of lagging in achieving the European Union’s goals for reducing energy intensity (as an outlier). According to research, countries importing goods from Poland by rail were characterized by large spatial differences in the energy intensity of this type of transport (energy consumption by rail transport per 1 USD of GDP). An increase in the average distance by 1% resulted in an almost proportional decrease in the energy intensity of this transport (by 1.0076%). This is an incentive to move goods over long distances from road to rail. Similarly, an improvement in the economic situation of the importer’s country by 1% resulted in a reduction in the energy consumption of this transport (this is primarily due to the technology used). However, an increase in transport capacity, i.e., transport work by 1%, causes an increase in energy intensity by approximately 0.99% (also almost proportional). This means that there are economies of scale. However, delaying the implementation of a sustainable transport policy or failing to implement it results in an increase in the energy intensity of rail transport in the entire system, although the elasticity is quite low (approx. 7%). The model is presented in the context of the process of interaction and liberalization of the rail market because liberalization of market access is an important instrument of the EU transport policy. Its operation was intended to improve services and increase the share of rail transport in the total transport market (environmental friendliness), and to reduce barriers between modes of transport and national transport systems.

One of the directions of rationalization is the implementation of the sustainable development paradigm, i.e., the shift paradigm, i.e., moving transport from road to rail, especially over long distances. This is intended to help reduce the energy consumption of the entire transport sector. However, for the market to be competitive, it was necessary to liberalize it in the economic, legal, and managerial context. Competition stimulates the efficiency of transport processes. The more efficient the process, the lower the energy consumption. Competition improves the quality of railway services, which influences market demand for railways that are less energy-intensive. Liberalization necessitated the interoperability of European railway systems, i.e., its technical and operational coherence (not yet completed), and this affected the quality of services, travel times, and passing the border crossings.

In summary, the implications for the sustainability and efficiency of rail transport as a result of liberalization are as follows:

- Reduction in carbon dioxide emissions—liberalization of the railway market contributes to improving energy efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which is in line with specific EU environmental goals,

- Increased economic efficiency—promoting the transition from road to rail transport helps to increase the share of railways in the market, while the energy-efficient operation of railways reduces operating costs, making rail transport more profitable and competitive with other modes,

- Improved service quality and reliability in support of sustainable transport-infrastructure modernization help improve the efficiency of rail operations and energy efficiency, and also affect the quality and reliability of rail services, which is fundamental in the promotion of rail transport to further support sustainable development goals.

Further development of rail transport in the European Union towards rationalization of energy consumption must be based on the following general assumptions:

- Modernization of railway infrastructure, mainly on railway lines belonging to the TEN-T, to reduce costs related to rail traffic, including wide implementation of modern railway network diagnostics, focusing on investments increasing capacity on strategic railway sections and the development of the TEN-T, striving to increase the maximum axle loads on the tracks, eliminating bottlenecks [156,157,158,159],

- Completing the full implementation of the rail interoperability recommendations on the TEN-T on railway lines, which will allow for the elimination of barriers related to the principles of organizing and managing rail traffic in individual countries of the community,

- Improvement of energy efficiency of traction vehicles resulting from the introduction of fuels and drive systems consistent with the principle of sustainable development,

- The use of multi-system locomotives to an increasing extent, allowing for the elimination of the barrier of various power supply systems for the traction network,

- Use of IT and telematics tools to an even wider extent, allowing for the simplification of administrative procedures, tracking the movement and origin of goods, and optimizing schedules and traffic flow (e-Freight), including the extensive use of artificial intelligence (AI),

- Harmonization of intermodal competition conditions through effective pricing policy [82,160].

Providing a competitive and sustainable substitute for road freight, rail freight transport is an essential part of the EU’s transport sector. But it has encountered difficulties including shrinking market share, obstacles from regulations, and constraints in infrastructure. A general pentad of conditions necessary for rail freight transport in the European Union and in the world in the directions indicated above can be mentioned:

- 1.

- Regulation and policy assistance:

- Deregulation and market liberalization are necessary to enhance rail freight, including both intermodal and intramodal competitiveness [135,161],

- Pro-competition laws and strong independent regulators are essential for network access and the growth of the whole transport sector [139,162],

- 2.

- Investments in technology and infrastructure:

- Substantial expenditures in terminals, infrastructure, and technologies are required to boost productivity and fulfill demand in the future [134,137],

- Enhancing planning, utilizing ICT systems, and implementing integrated supply chain strategies can enhance the effectiveness and quality of services [136,137],

- 3.

- Operational efficiency:

- Lower operating costs along with increased capacity might be achieved by running longer and heavier trains, wider loading gauges, faster average speeds, and greater use of wagon space [136,137],

- Despite being more expensive, high-speed rail freight provides significant CO2 reductions and may be competitive with suitable infrastructure charges and handling fees [133],

- 4.

- Client-focused service:

- More deregulation and the provision of door-to-door services, which are presently dominated by road transport, can lead to a more client-oriented service [136,137],

- Technology advancements including digitalized corporate processes, RO-LA, and intermodal terminals are crucial for drawing in clients [161],

- 5.

- Sustainability targets and goals:

- Policies ought to support rail freight transport as an environmentally beneficial alternative to lessen the damaging effects of road freight transport on the environment [134,138],

- The environmental advantages of rail freight transport can be further increased by fully electrified transport networks and CO2 levies [133].

The EU’s rail freight transport depends on several factors, including infrastructure investments, regulatory support, client-centered services, operational effectiveness, and environmental sustainability. Strong regulatory frameworks, on the one hand, and deregulation, on the other hand, are necessary to promote competition and innovation. Infrastructure and technology investments will raise service quality and productivity. The combination of client-driven innovations and operational improvements will make rail freight transport more complementary—even competitive—with road transport. Lastly, advocating for rail freight transport as an environmental choice is consistent with the sustainability objectives of the European Union.

The aim of this article was achieved, the research questions were answered, and the hypothesis was positively verified. The research results indicate that the studied area is interesting and requires in-depth analyses. The limitations of this study result from its assumptions, methods used, and use of data (data for 2020 may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic). Rail transport faced persistent challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic [163]. The COVID-19 pandemic forced transport companies to adapt to new conditions. Carriers had to adapt to movement restrictions and supply disruptions, which resulted in higher operating costs [164]. The pandemic had a wide impact on the rail transport market in Europe. In 2020, the number of freight transports decreased by 7% compared to 2019. In 2021-2022, a reconstruction of the railway market was observed [165]. In the case of Poland, there was a significant decrease in the number of goods transported by rail by 15,363 tonnes [166]. Additionally, the pandemic has negatively impacted Poland’s international trade, with exports proving more resilient than imports, but overall trade flows have been disrupted by the pandemic [167]. Research by other scientists shows that the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on production processes in Poland. During the pandemic, many companies faced supply chain disruptions, which directly impacted their ability to export goods [168]. In addition, various types of shocks could have had an impact on the energy consumption of goods exported by rail: supply, price, structural, political, and social [99]. In the years 2010-2020, the Polish rail transport sector was exposed to various shocks:

- Structural—deregulation of the rail transport market in Poland led to increased competitiveness and efficiency. The increase in competition was beneficial, but the lack of appropriate regulations could limit the full use of the potential of the railway market [169,170,171];

- Political—EU transport policy, shifting transport from roads to railways, was aimed at reducing pollutant emissions and congestion. In Poland, increased competition in the railway sector increased the share of railways in the transport of goods, which had multidimensional effects on other sectors [25],

- Prices—the increase in emission prices under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) affected the energy sector in Poland [172], which translated into an increase in the operating costs of rail transport,

- Supply influences the energy consumption of transport in the long term by transferring production shocks in the industrial, processing, and construction sectors [173],

- Social and sanitary—mainly related to the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused disruption of supply chains and declines in the transport of goods, the financial condition of the railway sector [166].

The research carried out is innovative because the literature has not yet examined the energy intensity of rail transport with a similar approach, especially taking into account export–import relations and the methodology used. The research is interdisciplinary—it covers management, transport economics, spatial management, GIS, and econometrics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., E.Z., A.D., S.K. and P.D.-D.; methodology, E.S. and E.Z.; validation, E.S., E.Z. and A.D.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, E.S., E.Z., A.D., S.K. and P.D.-D.; resources, E.S., E.Z., A.D., S.K. and P.D.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S., E.Z., A.D., S.K. and P.D.-D.; writing—review and editing, E.S., E.Z., A.D., S.K. and P.D.-D.; visualization, E.S., S.K. and E.Z.; supervision, E.S., E.Z., A.D. and P.D.-D.; project administration, E.S. and E.Z.; funding acquisition, E.S., E.Z., A.D., S.K. and P.D.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

|  | Co-financed by the Minister of Science under the “Regional Excellence Initiative”. |

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, R. Research on the Correlation between Freight Transportation and National Economic Development. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 253, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwil, M.; Bartnik, W.; Jarzębowski, S. Railway Vehicle Energy Efficiency as a Key Factor in Creating Sustainable Transportation Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, J. Role of the Railway in Sustainable Multimodal Mobility. In Proceedings of the XXIII Konference S Mezinarodni Ucasti: Soucasne Problemy V Kolejovych Vozidlech/23rd Conference: Current Problems in Rail Vehicles, Ceska Trebova, Czech Republic, 20–22 September 2017; Michalkova, B.V., Ed.; 2017; pp. 327–334, ISBN 978-80-7560-085-1. [Google Scholar]

- Shirov, A.; Sapova, N.; Uzyakova, E.; Uzyakov, R.M. Comprehensive Forecast of Demand for Inter-Regional Rail Freight Transport. Econ. Reg. 2021, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkurina, L.; Maskaeva, S. Methods for Economic Assessment of Operational Quality and Its Impact on Railway Delivery Time. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 402, 06002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheret, D. Evaluation of Long-Term Prospects of the Structure of Freight Rail Transportation. VNIIZHT Sci. J. 2021, 80, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, L.; Huo, M.; Yu, X. Research on High-Speed Railway Freight Train Organization Method Considering Different Transportation Product Demands. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5520867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarz, M.; Przybylska, E.; Wolny, M. Reliability of the Intermodal Transport Network under Disrupted Conditions in the Rail Freight Transport. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 44, 100686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ke, Y.; Zuo, J.; Xiong, W.; Wu, P. Evaluation of Sustainable Transport Research in 2000–2019. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, R.A. Boosting Intermodal Rail for Decarbonizing Freight Transport on Java, Indonesia: A Model-Based Policy Impact Assessment. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 48, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Hao, H.; Bi, H. Evaluation on the Development of Urban Low-Carbon Passenger Transportation Structure in Tianjin. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 55, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Modal Split of Inland Freight Transport. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TRAN_HV_FRMOD (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Szałucki, K. Transport Samochodowy. In Transport. Tendencje Zmian; Wojewódzka-Król, K., Załoga, E., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 67–103. ISBN 978-83-01-22033-4. [Google Scholar]

- Załoga, E. Nowa Polityka Transportowa Unii Europejskiej. In Transport. Tendencje Zmian; Wojewódzka-Król, K., Załoga, E., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 583–614. ISBN 978-83-01-22033-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Zong, Y. The Impact of the Freight Transport Modal Shift Policy on China’s Carbon Emissions Reduction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. White Paper. Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area—Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System; COM (2011) 144 Final 2011; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, P.; Quan, S.; Chu, W. Analysis of Market Competitiveness of Container Railway Transportation. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, e5569464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, A.; Rahimi, E.; Amini, H.; Jamshidi, H. Freight Modal Policies toward a Sustainable Society. Sci. Iran. 2020, 27, 2690–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, B.; Bugarinović, M. Why and How to Manage the Process of Liberalization of a Regional Railway Market: South-Eastern European Case Study. Transp. Policy 2015, 41, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, T.; Yanginlar, G.; Kalaycı, S. Railway Transport Liberalization: A Case Study of Various Countries in the World. J. Men’s Stud. 2016, 6, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinová, E. Does Liberalization of the Railway Industry Lead to Higher Technical Effectiveness? J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2016, 6, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beria, P.; Quinet, É.; Rus, G.D.; Schulz, C. A Comparison of Rail Liberalisation Levels across Four European Countries. Res. Transp. Econ. 2012, 36, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hita, C.; Ruiz-Rua, A. Competition in the Railway Passenger Market: The Challenge of Liberalization. Compet. Regul. Netw. Ind. 2019, 20, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonowicz, M.; Zielaskiewicz, H. Rail Transport in Supply Chains. Autobusy Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2018, 19, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, R.; Jandová, M.; Król, M.; Nekrasenko, L.; Paleta, T. The Effectiveness of EC Policies to Move Freight from Road to Rail: Evidence from CEE Grain Markets. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 37, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.; Caffarelli, P.; Gastelle, J. Dynamic Changes in Rail Shipping Mechanisms for Grain (Summary); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://search.crossref.org/search/works?q=10.9752%2FTS280.08-2020&from_ui=yes# (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Spielvogel, J.J. Western Civilization: Volume II: Since 1500; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-357-94151-5. [Google Scholar]

- Duiker, W.J. Contemporary World History; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-357-36490-1. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, C. Bonds without Borders: A History of the Eurobond Market; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-84388-8. [Google Scholar]

- Steil, B. The Marshall Plan. Dawn of the Cold War; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5011-0237-0. [Google Scholar]

- Szpak, J. Historia Gospodarcza Powszechna; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1999; ISBN 978-83-208-1696-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lenkiewicz, T. Idee Integracji i Dezintegracji Unii Europejskiej w Perspektywie Historycznej. Gdańskie Stud. Międzynarodowe 2017, 15, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cogen, M. An Introduction to European Intergovernmental Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-18181-1. [Google Scholar]

- The Marshall Plan: Phase I 5 June–22 September 1947. In European Recovery and the Search for Western Security, 1946–1948; Bennet, G., Salmon, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-41417-1. [Google Scholar]

- Doliwa-Klepacki, Z.M. Europejska Integracja Gospodarcza; Temida 2: Białystok, Poland, 1996; ISBN 83-86137-23-1. [Google Scholar]

- Doliwa-Klepacki, Z.M. Integracja Europejska (Po Amsterdamie i Nicei); Temida 2: Białystok, Poland, 2001; ISBN 83-861 37-79-7. [Google Scholar]

- Etling, H.H. Robert Schuman (1886–1963. Życie Dla Europy. Droga Do Deklaracji Założycielskiej Unii Europejskiej Deklaracji Schumana z 9 Maja 1950 r. Rocz. Wydziału Nauk. Prawnych I Ekon. KUL 2005, 1, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Milward, A.S. Politics and Economics in the History of European Union; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 0-415-32941-8. [Google Scholar]

- Prawo Unii Europejskiej; Barcik, J., Grzeszczak, R., Eds.; Ch. Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-8291-395-8. [Google Scholar]

- Łastawski, K. Historia Integracji Europejskiej; Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek: Toruń, Poland, 2011; ISBN 978-83-7611-864-2. [Google Scholar]

- Häde, U. The Treaty of Lisbon and the Economic and Monetary Union. In The European Union after Lisbon; Blanke, H.J., Mangiameli, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 421–441. ISBN 978-3-642-19506-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, S. Lisbon Treaty—A Treaty Linking Past and Future of European Integration. J. Sichuan Univ. 2011, 3, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bonciu, F. The Positive Side of Lisbon Treaty. Rom. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2007, 2, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Phinnemore, D. The Treaty of Lisbon in Context. In The Treaty of Lisbon: Origins and Negotiation; Palgrave Studies in European Union Politics. Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, J.; Wardacki, W.; Zalewski, P. Transport Kolejowy: Organizacja, Gospodarowanie, Zarządzanie; Kolejowa Oficyna Wydawnicza: Warszawa, Poland, 1995; ISBN 978-83-86183-10-4. [Google Scholar]

- Burnewicz, J. Transport EWG.; Wydawnictwa Transportu i Łączności: Warszawa, Poland, 1991; ISBN 83-206-0986-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission—The Future Development of the Common Transport Policy. A Global to the Construction of a Community Framework for Sustainable Mobility; COM (92) 494 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. White Paper. European Transport Policy for 2010: Time to Decide; COM (2001) 370 Final 2001; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]