Abstract

This study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of the More Light for Amazon (MLA) program by examining the roles played by each stakeholder involved in the concession process and identifying the limitations faced for program success. The research employed a content analysis methodology, analyzing a variety of documents, including the Program Operational Manual, Commitment Terms, news articles and concessionaires’ notes. The findings reveal the crucial role of the government as an inducer of actions, establishing objectives and guiding norms for the private sector. Conversely, concessionaires assume the role of program implementers but encounter specific limitations in remote locations that challenge the provision and maintenance of the electrical system in beneficiary communities. The implementation of microgrid systems through concessions enhances coordination and integration between generation and distribution services, allowing for increased government control and ensuring transparency, efficiency and program effectiveness. These identified elements represent significant challenges for the implementation of public policies in remote regions of the Amazon. Overcoming these challenges will require coordinated and strategic actions involving both the government and concessionaires to ensure the complete fulfillment of energy needs in MLA program beneficiary communities.

1. Introduction

Electric energy plays a fundamental role in the development of a country. It is considered one of the main basic infrastructures to drive economic growth, improve the quality of life of the population and promote social inclusion. Electricity must be produced and distributed responsibly, taking into account the social, economic and environmental aspects involved. In addition, it is necessary to guarantee universal access to electricity, especially in rural areas and low-income communities, to promote social inclusion and equity.

Brazil has a robust electrical system with a diversified energy matrix [1] but faces challenges in expanding access to electricity in some rural areas and remote regions. For example, the Amazon region is a vast and difficult-to-access region, with a dense tropical forest, extensive rivers and a complex topography [2] and with municipalities with low political capacity [3], a fact that may limit the effectiveness of the public concession, regulation, construction and maintenance of the electrical system in the region.

In this sense, the construction and maintenance of electrical infrastructure in this area represent a significant logistical challenge, requiring the opening of roads, the construction of transmission lines and the installation of poles and transformers in places of difficult access [4]. As a means to mitigate these challenges, the federal government has been betting on programs for the universalization of electricity via concessions, such as the More Light for Amazon (MLA) program, aimed at the universalization of electricity in rural communities in the Legal Amazon [5].

Specifically, the MLA program offers tax incentives, lines of credit and financing programs with advantageous conditions for interested companies. Subsidies were also offered to reduce investment and operating costs, as well as contractual benefits for concessionaire companies that invest in the expansion of the electrical infrastructure in the region [4,6,7,8]. However, companies face many challenges due to the region’s unique geographic, socioeconomic and environmental characteristics.

When acting via concessions, the federal government uses a partnership model between the public and private sectors that allows the management of public services, works or assets through long-term contracts [9]. However, in the concession of public utility services to private companies, service concessionaires tend to emphasize the maximization of profits to the detriment of social objectives [10], which may not serve the interests of the community.

Although concessions are widely used in developed countries to manage infrastructure projects and public services and even as a means of stimulating innovation, concessions have also been the target of criticism by those who consider that this form of partnership has not been beneficial for the population. For example, some critics argue that concessions do not generate the expected results and can increase inequality between richer and poorer regions [11]. Moreover, the literature lacks comprehensive studies that address the specific socioeconomic and political challenges faced by the universalization of electricity in remote regions such as the Amazon.

Although there are several studies on technologies and technical solutions for the electrification of remote areas and models of public concessions, a deeper understanding of the social, economic and political factors that influence the implementation of these projects is needed. In this sense, the objective of this study was to carry out an analysis of the federal government’s MLA program to identify the role of each of the parties involved in the concession process and the limitations faced for the success of the program.

Performing the analysis of this policy is important to identify the benefits and possible risks of implementing this type of policy, so public policy analyses are essential to understand the benefits and risks involved in the concession process, which requires substantial investments and can have a significant impact on the local economy [12,13,14,15]. The existing literature generally does not adequately explore the economic and social aspects of electrification in these areas, such as the potential for job creation, sustainable economic development and the effects on local communities.

In addition, governance and the public concession policy are also areas that require further study. The way in which concession contracts are designed and implemented can have important implications for the success and sustainability of electrification projects in remote regions [12,16] since, in these regions, the operating conditions pose more risks and offer opportunities for anticompetitive behavior, resulting in concentrated market structures and inefficient regulation [17,18,19]. Therefore, it is important to plan and coordinate actions to promote competition and efficiency in the electricity sector.

The lack of in-depth analysis of the specific institutional and policy challenges faced in this context limits the development of effective strategies for electrification in these areas. Therefore, there is a need for research that fills this gap by analyzing the socioeconomic and political aspects of electrification in remote regions and public concessions as a means to provide a solid basis for the successful planning and implementation of similar projects. In addition to this introduction, the sections in this article address the theoretical framework, methodology, results and discussion and final considerations.

2. Theoretical Framework

The organization of electricity generation, transmission and distribution services in Brazil evolved throughout the country’s history. Electrification in Brazil began to develop in urban areas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, driven by private companies [12,20]. However, rural electrification was practically non-existent in this period due to the lack of infrastructure, the low development of rural areas and logistical difficulties.

Because of this, the Brazilian government promoted the nationalization of the electricity sector with the creation of Eletrobras in 1962, responsible for the coordination and management of state-owned electricity companies. In this way, the government implemented policies to encourage rural electrification, such as financing programs and incentives for private sector participation. However, it was only with the restructuring of the Brazilian electricity sector from 1990 onward that there was an increase in awareness of the importance of rural electrification as a way of promoting the socioeconomic development of rural communities [20,21,22,23].

As a means to regulate the sector, the National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) was established in 1996, with the main function of guaranteeing the quality of service, promoting competition and protecting consumers’ interests [21,24]. Since then, specific programs aimed at rural electrification have been implemented, such as the National Program for Universal Access and Use of Electric Energy (Luz no Campo), launched in 2000, the Light for All Program (2003) and, finally, More Light for the Amazon (2020).

All programs established new technical service criteria for concessionaires and permit holders, which ensured the inclusion of millions of Brazilians historically placed on the margins of the electrical system and represented a breakthrough in relations between concessionaires and consumers [23]. In electrification programs in remote regions, a concession plays a key role in establishing a model of partnership between public authorities and the private sector. This partnership aims to make investments viable, promote the expansion of rural electrification and bring electricity to communities that previously did not have access to this essential service.

The concession appears to be a solution to mitigate one of the biggest challenges faced by electrification programs in remote regions: financial barriers. By transferring the responsibility and investment burden to interested concessionaires through a tariff paid by the user, the concession model allows access to financial resources from the private sector, which are essential for the implementation and operation of electrification systems in these areas.

In this context, the concessionaires make a commitment to provide the electrification service and assume the financial risk inherent to the operations, seeking to recover the investments made through the revenues generated by the tariffs. Depending on the context and regulatory structure, concessions can operate under a monopoly regime or in a competitive environment, encouraging the efficiency and quality of services provided.

A concession as a public–private partnership model offers significant benefits. It allows the transfer of resources and technical knowledge from concessionaires to the public sector, as well as the sharing of risks and responsibilities between the parties involved. A public concession is a means of enabling the improvement of public services by attracting private capital to alleviate government costs. Public administration does not relinquish its responsibilities in this regard. There is a simple temporal delegation, subject to constant control, for the mere provision of the service [14,25].

Based on this, the concession transforms the public service into an enterprise, which causes the service to lose its intrinsic characteristics of being public [12,16,26]. Thus, markets need to be financially viable to ensure their continuity and sustainability in the long term. However, low family income, low electricity demand and high investment costs characterize rural markets that are dispersed and unattractive, leading governments to institute subsidies to minimize economic distortions and operational viability [16,27,28] as a means to allow the concessionaire to adequately fulfill these obligations given the responsibilities toward its stakeholders, such as shareholders, customers, employees and the communities where they operate.

Consequently, concessionaire companies seek to ensure that they have consistent contracts and the quality of differentiated institutional conditions in terms of support [political, legal, fiscal and financial] [12,16,29] to operate in the region. In this way, attention must be paid to commitments, planning, government budgeting and stakeholder coordination [16,27,28,30]. Therefore, contracts must reconcile the interests of federal, state and municipal governments and companies in the electricity sector so that the burden does not make it unfeasible for the user to benefit from the service.

These facts create emblematic and complex projects for companies that do not know the reality of the region, which is especially the case for the Amazon [1]. In the market context, the geographic characteristics and challenges of the Amazon may make electrification in the region unfeasible or less attractive for companies in the electricity sector. This is due to the remote location of the Amazon region and its specific socio-environmental characteristics [1]. The lack of adequate infrastructure in the region presents an additional challenge concerning not only the transmission of electricity but also the need to build roads, railways, ports and airports [31].

The lack of these basic infrastructures hinders investments, since the high costs involved in building new roads and transmission lines to connect remote areas to the national electricity grid may not be attractive for companies. It is important to emphasize that these specific challenges faced in the Amazon have not been captured by other studies that explored the challenges of electrification in remote regions, such as Bangladesh, Haiti, Malaysia, India, Senegal and Kenya [27,28,30]. Each region has its own geographic, socioeconomic and political characteristics, which influence the challenges faced in implementing electrification programs. Therefore, it is essential to consider these specificities when pointing out solutions and lessons learned in different contexts.

In addition, concessions are susceptible to changes in government policies, regulations and commercial agreements, which can create uncertainty and impact investments and operations in the sector [30]. In this way, the consolidation of this market is subordinated to the increasingly financialized accumulation logic and marked by the sharing of risks, resources and technical knowledge to boost the development of the electrical infrastructure [16]. In this context, the public administration has an increased responsibility, as it is the agent that plans and regulates the process.

During the bidding process, the public administration must analyze and judge whether the proposals from the private sector are technically, economically, financially and operationally sound to fulfill the community’s wishes and also provide profit to the commissioner, as well as ensure the execution of contract agreements [16,26]. It is necessary to be attentive to ensure fair competition and avoid the abuse of a dominant position, as this regulation will ensure economic efficiency, competition and benefits for consumers [15,32]. Therefore, concession contracts must be properly structured, addressing legal, economic and technical aspects [14,25]. Next, the proper modeling of contracts is essential to ensure the efficiency and quality of the services provided, as well as to protect the public interest.

Therefore, an adequate regulatory structure is necessary, with effective supervision mechanisms and transparency to guarantee the efficiency and accountability of concessionaires from the electricity sector [13,33,34]. Through this framework, the government will be able to adequately monitor companies and make sure that they comply with contractual and regulatory obligations, especially concerning the quality of service, fair tariffs and adequate investments [35].

In the context of inadequate regulatory structures, there may be anticompetitive behavior, such as abusive prices and discrimination between competitors, as well as the hindrance of the creation of a competitive environment [18,19]. In addition, the lack of competition can be a result of concentrated market structures and ineffective regulation [36]. Certainly, not modernizing the rules can create distortions, threatening the sustainability of one of the most important sectors of the economy.

However, the effectiveness of regulations can be complex, especially in a fragmented political and institutional environment, as is the case in the Amazon region, where there is a great diversity of governmental, political and social actors. In certain states of the region, such as Macapá and Amapá [12], in which the government made an effort to establish efficient markets, regulation failed to guarantee compliance with sectoral contracts in favor of service quality.

This shows that transferring public services to the private sector, guided by competition and financial profitability, does not necessarily result in improvements in the quality of public services [15,32] but rather the transfer of the risks of the undertaking, the cost of services and user income in favor of the state [14,26,37]. In practical terms, the concession implies reducing costs for non-users and worsening the users’ economic situation.

These problems tend to be more common in an environment where the lack of state capacity limits state action and the state can be dominated by powerful actors, causing regulation to be weak, with little transparency and accountability [38,39,40,41,42,43]. One of the main reasons for this is the complexity of the electricity sector, which involves a large number of actors and interests, in addition to the lack of capacity and resources of regulatory agencies to adequately monitor and regulate the electricity sector.

In many cases, regulatory bodies do not have sufficient resources to effectively oversee companies, which can lead to failures in the oversight and enforcement of regulatory standards. In addition, in some situations, the regulatory bodies themselves may be seen as lacking in independence or ineffectiveness, which can lead to situations in which companies have little incentive to comply with rules and regulations.

A lack of clarity and control in the electricity sector can arise when companies have ties to political groups or private interests. This can result in a lack of transparency and accountability, as these connections can protect companies from public scrutiny [32]. This lack of clarity and control can lead companies to operate without social commitment, disrespecting the rights of local communities and workers. This includes practices such as the exploitation of illegal labor, forced removal of local communities and violations of labor rights.

The absence of clear regulations and strict controls can allow companies to provide inadequate or low-quality services without incurring penalties. This could harm the competitiveness of the electricity sector and affect the region’s economic development. Quickly, the succession of facts, in turn, contradicts the supposed effectiveness of the private sector in the context of competition to the detriment of public action, attributed to neoliberalism, which causes the Amazon region to end up with limited service provision [12] and lack transparency in the management of services [10,31]. Still, a public concession can also lead to inequality in the quality of services provided, an increase in service prices and the loss of public control over the provision of services.

In this context, public policy analysis provides a way to understand choices, processes and their consequences [10]. Firstly, this interdisciplinary approach, which spans from economics and public administration to sociology and philosophy, enables public managers and other stakeholders involved in policy making to analyze the safety, effectiveness and efficiency of public policies as a means to guarantee compliance with the established objectives and compliance with the general principles of public administration [29]. This tool is important to help public managers identify the problems faced, find effective solutions to solve them, implement and monitor public policies and assess changes in political, economic and social contexts. Through public policy analysis, public managers can deepen the analysis and understanding of how public policies affect people’s lives.

This method is a tool that can help public managers to identify problems, evaluate the costs and benefits of public policies, identify the main barriers to success and establish short- and long-term goals for the implementation of public policies. In addition, public policy analysis allows public managers to better understand the impact of policies in terms of cost, time and results, helping to ensure that policies are implemented more effectively and transparently.

3. Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive research study. The descriptive approach is used to describe or explain a problem or situation. The main purpose of descriptive research is to provide a more detailed description of a phenomenon or point of view, rather than analyzing or explaining its causes [44]. This approach involves collecting qualitative data, such as interviews, questionnaires, observations and document analysis.

The material analyzed is from a documentary source and consists of official public documents, such as the manual for operating the programs, monitoring reports and other materials released by companies on the subject. The documents studied include Decree No. 10,221, from 5 February 2020, which establishes the MLA program based on Art. 13, item I, of Law No. 10,438, from 26 April 2002 [7], which aims to promote the universalization of the electricity service throughout the national territory.

In addition, the Program Operationalization Manual was analyzed, which defines the operational structure and establishes the technical and financial criteria, procedures and priorities to be applied in the program [8]. The Terms of Commitment between service providers and the Ministry of Mines and Energy were also examined [5] and made available during the monitoring of state services. In addition, journalistic materials, notes from the concessionaires and scientific articles that address the topic and provide support for the information presented were considered.

This variety of documentary sources allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the program, considering different perspectives and sources of information. By combining the analysis of official documents with journalistic materials and scientific articles, it is possible to obtain a more complete and grounded understanding of the MLA program and its developments. It also provides a better understanding of its operational structure, technical and financial criteria, procedures and priorities, as well as the Terms of Commitment between service providers and the government.

The documents were organized in a logical and coherent structure to facilitate the analysis and interpretation of the data. To analyze the selected documents, technical procedures of content analysis were applied. As defined by [45], content analysis is a set of techniques that aim to obtain, through systematic and objective procedures, a description of the content of messages, allowing the inference of knowledge about the conditions of production and the reception of these messages. The objective is to identify key information, such as aspects of the program’s operational structure, technical and financial criteria, and established procedures and priorities, in addition to any other relevant information contained in the documents and materials.

The data were analyzed and interpreted using the IRAMUTEQ software (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires). The software performs the analysis based on the linguistic characteristics of a text as a means to identify the frequency of words, grammatical forms, the vocabulary used, etc., and understand the structure of the correlations between the words and the explanatory context that appears in the text [3,46].

The method used to capture the correlation structure was correspondence factor analysis [CFA], which allows for identifying the degree of association between large sets of words and the explanatory context [47], as well as facilitating counting via a word cloud and the interconnection structure through similarity analysis. The word cloud [48] is grouped and organized graphically according to the word frequency, enabling the quick identification of keywords in an analyzed corpus.

The similarity analysis is based on graph theory and allows the identification of co-occurrences between words, resulting in indications of a connection between terms [49] as a means to support interpretations and identify trends, gaps or challenges highlighted in the documents studied on the MLA program.

4. Results and Discussion

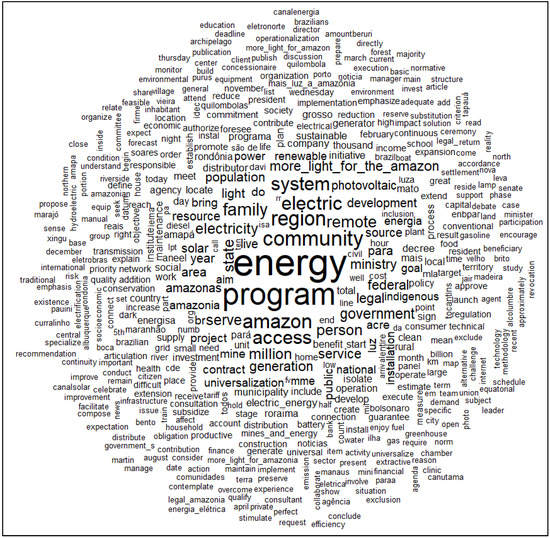

As a means to understand the roles and challenges of the actors involved, the analyzed corpus is composed of a set of documents with 26 texts, with 567 text segments, 2370 forms, 13,278 appearances, 1620 lexemes and 1480 forms in use; there are 39 additional variations, of which 85.9% were classified. Among the keywords presented through the word cloud are program, More Light for Amazon, electricity, community, Legal Amazon, system and government (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vocabulary that appeared most frequently in the analyzed corpus.

The word PROGRAM is the central element of the “More Light for Amazon” policy, as it describes the plan and objectives to be achieved. In fact, programs such as this are public policy initiatives designed to address specific challenges and fill gaps in particular areas or sectors. In the case of “More Light for Amazon”, the program was designed to address the lack of access to electricity in communities located in regions with difficult access to the Legal Amazon [5,7].

In the context of public administration, programs such as this play an important role in implementing policies and achieving specific objectives. To be effective, a program requires careful planning, adequate management and partnerships between the various actors involved, such as local governments, regulatory bodies, companies in the electricity sector, civil society organizations and the beneficiary communities themselves. In addition to resolving the lack of access to electricity, the program must consider environmental and social sustainability, adopting sustainable technologies and practices.

Systematic monitoring and continuous evaluation are essential to measure the program’s impact, correct gaps and promote learning for future initiatives. The program aims to promote regional development, improve the quality of life, reduce the energy deficit and promote social inclusion. Among the actions implemented are the use of low-cost technologies to generate clean energy and the granting of subsidies for low-income families to purchase solar energy equipment.

The central focus of the program is the provision of ELECTRICITY for the population, and the term refers to an essential service capable of expanding opportunities for socioeconomic change in the region. The program has provided electricity to different communities and promoted advances, such as the expansion of electrical coverage, clean and accessible energy, improvement in the quality of life of populations, greater energy security, economic and social development in the region, a reduction in energy costs, greater social inclusion and the development of low-cost clean energy technologies [50]. Achieving these goals is only possible thanks to the most appropriate type of generation SYSTEM (grid or photovoltaic system extension).

This system, in addition to reducing operating costs, enables the implementation of medium- and long-term projects, such as microgeneration and mini-generation projects in remote locations, described here as the LEGAL AMAZON, a region where families do not have access to electricity. These families are represented by the highlighted word COMMUNITY. They are the beneficiaries of the MLA program, residing in remote access regions.

These areas comprise indigenous communities, quilombola territories, rural settlements and riverside communities. The difficult access to these areas deprives those people of social benefits, such as home lighting; the use of household appliances; the use of the means of communication; the electrification of health clinics [making it possible to conserve vaccines and purchase equipment]; and the adequate lighting and ventilation of schools, among other benefits generated by access to and use of electricity [20]. Therefore, it is important to consider the specific challenges faced by these communities in terms of access to electricity.

These communities are located in regions of difficult access, where the electricity infrastructure is precarious or non-existent. The communities mentioned in the passage face significant challenges in terms of accessing electricity due to their remote location and adverse geographic conditions [31]. The lack of electrical infrastructure in remote areas results in limitations in the use of household appliances, poor lighting, the lack of reliable communication and difficulties accessing essential services. However, power utilities face financial challenges in these sparsely populated areas due to high construction and operating costs.

In addition, the implementation of electric energy projects can have environmental and social impacts, requiring mitigation measures that increase costs. The energy demands of remote communities are different from those of urban areas, requiring additional investments in sustainable solutions, such as solar energy and micro-hydroelectric power plants. However, it is important to recognize that these solutions do not always offer an immediate financial return for electric power concessionaires, as pointed out in previous studies on electrification in remote regions of Bangladesh, Haiti, Malaysia, India, Senegal and Kenya [27,28,30].

The implementation of these technologies requires an in-depth understanding of the characteristics and specific needs of each remote region, taking into account the financial and technical barriers, and a project design focusing on renewable energy and decentralized systems as a way for remote regions to overcome the implementation barriers [30]. In this context, the term GOVERNMENT, highlighted in the word cloud, represents the inducing agent of public policies, responsible for reducing social inequalities. Faced with its inability to implement, supervise and inspect this program, it acts through concessions [contracts signed with private companies], guaranteeing greater efficiency and quality in the delivery of these services, and assumes the role of supervisor as a means to guarantee that its objectives are achieved.

In Brazil, the government plays a central role in rural electrification, including formulating policies, providing funding, creating specialized institutions and coordinating public–private partnerships, unlike what happens, for example, in Bangladesh, where there is a lack of government collaboration, particularly regarding support for energy policies [27,30]. On the other hand, in other countries, such as Haiti, Malaysia, India, Senegal and Kenya, governments act more by mobilizing financial resources together with different actors to diversify financing sources by seeking support from international organizations, development banks, sectoral funds and other sources of investment.

Certainly, the government plays a fundamental role in the concession of public services, acting as an inducing agent of public policies. It must define and delimit the activities to be carried out by the concessionaire, establish quality and price standards, supervise compliance with contracts, monitor compliance with user rights and ensure the transparency of processes [21]. While there may be challenges in the government’s ability to directly implement, supervise and oversee these programs, concessions signed with private companies allow for greater efficiency and quality in the delivery of services.

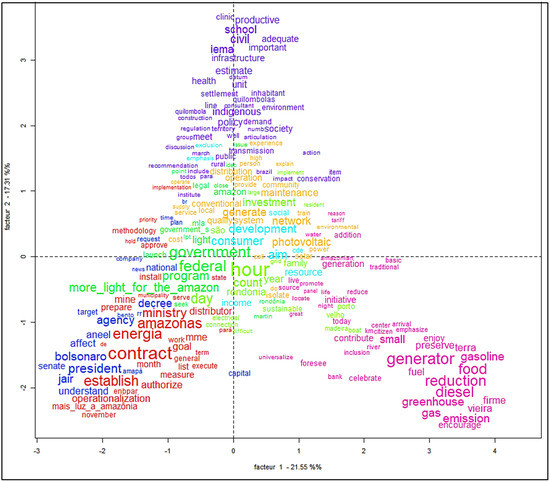

The government also assumes the role of supervisor, ensuring that the program’s objectives are achieved and that there is a balance between the public and private interests involved in the concessions. As reflected in Figure 2, the government assumes the central role in the analysis of the MLA program, since it is largely responsible for defining the objectives and norms that must be followed by the concessionary companies.

Figure 2.

Correspondence factor analysis.

Figure 2 shows a Cartesian plane with the distance between elements inserted in this debate and their connections with the research center—the MLA program administered by the government. In this program, the government faces several administrative challenges to mitigate the precarious infrastructure for the energy service in the north of the country. The first challenge is financial. Since the program is financed by state resources [7,8], governments must provide sufficient resources to finance infrastructure projects.

Adequate funding is crucial to the success of the MLA program, which seeks to electrify remote regions in the Legal Amazon. Resources will come from agents in the electricity sector, the Energy Development Account and other sources regulated by the Ministry of Mines and Energy in conjunction with government agencies [8]. The program prioritizes serving households in these regions and emphasizes the social nature of the investment. The distribution of resources is based on the need to mitigate tariff impacts, address regional needs and consider the financial contribution of the Executors [8].

When comparing the funding system of the MLA program with other similar programs in different parts of the world, we can see that it is based on the use of grants from the country’s own resources. These grants are intended to cover the operating costs of the concessionaires, ensuring the project’s economic viability and the provision of electrification services in remote regions. In this way, the Brazilian government strives to ensure the provision of public services [15,32] and minimize the transfer of enterprise risks and the cost of services to users [14,26,37], aiming to promote social and economic impacts as a means to improve the living conditions of the beneficiary communities, which is not observed in other programs around the world.

In some countries, such as Bangladesh and India, specific funds are established to finance rural electrification [27]. These funds come from different sources, such as international donations, governments, financial institutions and public–private partnerships. Another financing approach adopted in some countries is charging specific fees or contributions for rural electrification. For example, in certain regions of Malaysia, urban consumers pay an additional fee on their electricity bill, which is used to fund electrification programs in remote rural areas [28]. This model seeks to balance costs between urban and rural areas, enabling access to electricity in more distant regions.

This own-grant financing approach differs from other systems that may rely on external sources, such as international loans or public–private partnerships. While the use of the grant itself is an interesting strategy to ensure the economic viability of the MLA program, it is important to point out a few restrictions of this funding model. Relying solely on internal resources can restrict the scale and scope of the program, as available funding may be limited. This could hinder the program’s ability to reach a larger number of households or to implement more extensive electrification projects.

Furthermore, relying only on self-sustaining grants can pose risks in terms of financial stability. Economic fluctuations or changes in the energy sector can impact resource availability and disrupt program continuity. Reliance on a single funding source can also limit the flexibility to adapt to unforeseen circumstances or incorporate innovative solutions.

Comparatively, alternative financing systems that involve external sources, such as international loans or public–private partnerships, can provide additional financial resources and expertise. These partnerships can bring capital investments, technical expertise and operational efficiencies that can contribute to the program’s effectiveness and sustainability.

However, it is essential to carefully assess and manage any dependency on external sources of funding. Potential challenges can arise from negotiating and paying off loans, as well as aligning objectives and priorities among the various stakeholders involved. Furthermore, the involvement of private entities can introduce for-profit interests that can influence the direction of the program and potentially impact its social objectives.

Combining self-sustaining grants with external investment and partnerships can help mitigate the limitations of relying solely on internal resources, ensuring both financial viability and the ability to achieve broader, more impactful results. Strategic planning and effective financial management are crucial to balancing these various sources and ensuring the program’s long-term success and sustainability. In addition, it is essential to establish efficient mechanisms for monitoring and controlling resources to avoid waste and ensure that they are directed to priority areas and communities most in need.

Another challenge is to establish an effective concession system. This concession must ensure that projects are carried out safely and efficiently and that they comply with legal requirements. In addition, it is also necessary to take measures to prevent and control corruption and fraud in the granting of these projects. Finally, there is also an implementation challenge. These projects can be complex and time-consuming, requiring effective coordination between the different levels of government, in addition to being monitored to verify compliance with the goals established with the concessionaires.

As part of the program, electric power concessionaires have the role of supplying energy to these communities through generation, transmission, distribution and consumption infrastructures [8]. In addition, they are also responsible for maintaining the installed electrical power systems, ensuring that energy is available for proper use [50]. This responsibility implies the supply of reliable, continuous and quality energy to meet the needs of the beneficiary communities. This includes identifying and correcting faults and repairing and replacing damaged equipment, thus ensuring availability and energy efficiency.

Another important function of electric power concessionaires in the MLA program is to provide information and advice on the proper use of electricity for residents of these communities [8]. This involves educating residents about installing and maintaining electrical equipment, as well as encouraging responsible and efficient consumption practices. This orientation is important not only for the proper use of energy but also for promoting safety, economy and sustainability. The non-involvement of communities causes failure in the maintenance process to reduce long-term maintenance costs [28], an important element to make the projects economically viable and adjust the roles of the actors.

The government assumes the role of inducing action, and the concessionaires have the role of implementing actions. These roles are complementary and essential to the program’s functioning and success. The government is responsible for conceiving, planning and coordinating the public policies necessary to enable access to electricity in remote communities in the Amazon [31]. The government acts to promote the program and create the necessary conditions for the actions to be implemented.

Concessionaires are responsible for supplying electricity to remote communities through the installation, operation and maintenance of generation, transmission and distribution infrastructures. In this sense, concessionaires are responsible for designing, building and operating the electrical distribution networks necessary to bring energy to remote communities.

To serve program beneficiaries, the initiative provides for the use of solar energy generation and the replacement of small generators, which today are the only source of energy for many families living in these regions; these words are shown in pink in the figure above. These generators run on diesel or gasoline, which is why the new system contributes to reducing the burning of fossil fuels, makes it possible to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and encourages the sustainable use of resources in the Amazon rainforest.

Replacing polluting fuels with electricity also has positive socioeconomic implications. It can promote the establishment of traditional communities in their territories, preventing rural exodus and contributing to local development. In addition, environmental preservation promoted by reducing the consumption of fossil fuels contributes to mitigating climate change and conserving biodiversity.

These new technologies have contributed to greater rural electrification, driven by the use of renewable technologies, such as solar and wind energy. These energy sources have proven to be more viable and accessible to remote areas, providing sustainable energy solutions for rural communities, especially those isolated in the Amazon region.

These technologies are in line with the growing concern about the diversification of the energy matrix and the promotion of renewable sources. Encouraging the use of these sources has been a priority to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and mitigate the environmental impacts caused by large hydroelectric projects [15]. In addition to providing access to electricity, these decentralized and sustainable solutions have the potential to reduce utility operating costs, as they can be more efficient in terms of infrastructure and operating costs compared to expanding conventional electricity grids.

One of the additional advantages of the program when focusing on microgeneration from renewable sources is the improvement in the organization of the governance structure. This occurs because the process of generating and distributing electricity is concentrated in a single actor, breaking with the disorganization previously present in the governance of the sector [19,51]. With this centralization, it becomes possible to direct energy generation actions toward renewable sources, avoiding the imposition of inflexible thermoelectric plants in the composition of the electrical system [19]. This reorganization of the governance structure brings significant benefits.

By having a single actor responsible for the generation and distribution of electricity, it is possible to improve the coordination and operational efficiency of the sector. The centralization of activities allows for more agile and effective decision making, in addition to facilitating the implementation of public policies aimed at promoting renewable energy sources [15,32]. By directing generation actions toward renewable sources, the program seeks to mitigate environmental impacts and reduce dependence on thermoelectric plants powered by fossil fuels [12,18,32]. This contributes to the energy transition and the sustainability of the electricity sector, in line with the goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and combating climate change.

By excluding the imposition of inflexible thermoelectric plants from the composition of the electrical system, the program encourages the diversification of the energy matrix, promoting the use of renewable sources that can adapt more flexibly to the energy demand [15]. This increases the resilience of the electrical system, reducing the risk of shortages or interruptions in energy supply.

In this way, the concentration of energy generation and distribution activities in a single actor, combined with the emphasis on renewable sources, promotes more efficient and sustainable governance, aligned with the objectives of sustainable development and environmental protection. This is particularly relevant in the Amazon region, which has a rich biodiversity and is considered one of the most important areas in the world in terms of environmental conservation. Therefore, overcoming the previous disorganization and moving toward clean energy sources represent important advances in the electricity sector, contributing to the construction of a more efficient, resilient and environmentally responsible system.

On the other hand, the sentences in yellow portray the logistical challenges in terms of operating and maintaining the implementation of the photovoltaic system in these territories, a fact that tends to make these projects financially unfeasible, since the lack of logistical infrastructure can make the installation and maintenance processes of decentralized generation systems more expensive. The logistics of implementing the photovoltaic system involve several aspects.

First, it is necessary to plan and carry out a detailed survey of the communities to be served. Next, it is necessary to design and size the photovoltaic systems according to the needs of each location [52]. This involves determining the required solar power generation capacity, the number and wattage of solar panels, energy storage systems [such as batteries] and indoor distribution systems.

Once designed, the necessary equipment, such as solar panels, inverters, batteries and cables, must be purchased and transported to communities by suitable means [such as boats, planes or land vehicles], ensuring the safe and efficient delivery of the equipment [8,31]. Once installed, photovoltaic systems must be regularly monitored and maintained to ensure their proper functioning. Therefore, the lack of adequate infrastructure, such as road lines and bridges, represents higher costs for providing the service, which can influence tariffs.

Added to the logistical cost, there is a challenge regarding the technical training of local communities and companies involved in the implementation of these projects. It is necessary to ensure that knowledge and skills are adequate for the correct operation and maintenance of power generation systems as a means to ensure the sustainability and durability of these solutions. All these elements represent additional costs assumed by the concessionaires.

These costs, which are necessary to effectively obtain the benefits intended by the entrepreneur, translate into transaction costs, which means that the entrepreneur transfers to the price the uncertainties and insecurities that permeate the business activity [15,32]. In the context of concessions, these costs can arise due to uncertainties about issues such as geographic conditions, access to resources, future demand and regulatory changes. These uncertainties may lead to concessionaires transferring risks and uncertainties to the prices charged to users. This may result in higher tariffs to offset the additional costs and uncertainties faced by concessionaires. Consequently, it may be incompatible with providing affordable rates, that is, rates that are accessible to users.

Achieving the objective of affordable tariffs requires careful consideration of the risk attributed to concessionaires [14,16,26]. Governments, highlighted in green in Figure 2, must balance the need to encourage private investment and economic development with protecting user interests and ensuring affordable tariffs. In this sense, concession contracts must establish clear mechanisms for the allocation and management of risk between the government and the concessionaires, since the challenges that the region imposes are not mere technical details that can be postponed or left aside to be discovered by the magic of the market [36,51]. This may include defining tariff review criteria and risk-sharing and incentives mechanisms for efficiency and performance as a means to facilitate local socioeconomic development.

The increased risk faced by concessionaires can harm local economic development. If risks are excessive or poorly managed, it can discourage investment and limit economic growth in the region. Concessionaires reluctant to take high risks may be less likely to expand their businesses, invest in additional infrastructure or provide quality services.

Therefore, it is critical that governments carefully understand and assess the risks involved in concessions and adopt appropriate strategies to mitigate them [14,16]. This may include creating a stable regulatory environment, implementing risk-sharing mechanisms and promoting public–private partnerships that balance concessionaire interests and local economic development objectives.

This is because the Amazon population is characterized by great socioeconomic diversity, with urban and rural areas and traditional and indigenous communities. This can lead to disparities in electricity tariffs, as some areas may require additional investments to guarantee access to the service. In this sense, the risks for concessionaires are even greater, since Art. 5 of the decree establishing the program does not explicitly mention the participation of the government in the operation and maintenance of the systems, but mentions that “ANEEL will establish the cost referring to the operation and maintenance of generation systems, with or without associated grids” [5,7].

This lack of clarity regarding the government’s participation in the operation and maintenance of the systems can represent a financial risk for concessionaires [16,26]. Although ANEEL sets the cost of these services, it is important to consider whether there will be adequate profitability to cover the expenses incurred by the concessionaires to guarantee the operation and maintenance of the systems in perfect working order. Moreover, the concessionaires are responsible for fulfilling the obligations established by ANEEL concerning the operation and maintenance of the systems [24].

This implies assuming financial responsibility for any problems that may arise during operation, such as repairs, the replacement of components or necessary technological updates. These financial risks can be amplified by uncertainty regarding the durability and service life of photovoltaic systems, as well as the variation in maintenance costs over time. Incidentally, the possibility of adverse events, such as natural disasters or vandalism, may also pose additional financial risks for concessionaires.

It is important to point out that the mitigation of these financial risks depends on an adequate assessment of the costs involved in the operation and maintenance of the systems, as well as on the clear definition of responsibilities between the concessionaires and the government. The existence of clear and transparent contracts between parties can help mitigate these risks and ensure the financial viability of concessionaires under the MLA program.

The words contract, conventional, program, system, set, viability and distributor are some of the items highlighted in red. Contracts play a crucial role in the relationship between the government and the companies involved in the program, as they are the instruments of regulation, establishing the rights and obligations of the parties involved and guaranteeing the provision of the electrification service [14,15]. Systems and feasibility underscore the importance of considering different electrification technologies.

These contracts are regulatory instruments that establish the rights and obligations of the parties involved, guaranteeing the provision of electrification services in remote regions. When analyzing Figure 2, which was presented earlier, we can observe a gap between cluster 3, highlighted in red, which describes the role of the contract, and cluster 4, in violet, which represents the needs of society, the socioeconomic importance of energy in these remote areas and the need for proper planning.

This distancing can be explained by cluster 2, in yellow, which addresses the logistical challenges related to operating and maintaining the system in these remote regions. These challenges can include logistical difficulties, the lack of qualified professionals and the complexity involved in operating and maintaining power generation systems. Therefore, it is essential to consider these different aspects, such as the role of contracts, society’s needs and operational challenges, to ensure the success of the MLA program and the effective provision of the electrification service in these remote regions.

This requires an integrated and strategic approach, involving the government, companies and society, as a means to overcome challenges and achieve the proposed objectives based on a viable action for the companies. In this sense, the word “feasibility” suggests the importance of considering the specific characteristics and needs of each region in terms of assessing the economic and financial viability of electrification projects in remote regions widely discussed in the literature [15,16,28,30].

One of the main challenges in making electrification projects viable in remote regions is related to the high costs of implementing and operating the necessary infrastructure, such as transmission lines and distribution networks. The low population density and the difficult geography of these areas increase the installation and maintenance costs of electrical systems, which can compromise the economic viability of the projects.

One way to overcome economic and financial challenges is to seek innovative and sustainable solutions, such as the adoption of renewable energies and the implementation of decentralized generation systems, such as solar photovoltaic systems, as the project foresees and the concessionaires have been implementing. These solutions can reduce operating costs and make projects more viable in the long term, as well as promote the use of clean energy sources and contribute to the environmental sustainability of remote regions.

The area highlighted in red demonstrates that in addition to honoring the commitment to universal access to electricity, the program hopes that, through the use of this resource, social and economic development will be generated for the benefited areas, enabling improvements in education, health, access to information and the promotion of activities aimed at increasing family income. Thus, the words are highlighted: comply, productive, articulation, need, important, society, commitment and community.

As previously seen, the program aims to universalize electricity to remote regions of the Legal Amazon as a means to bring about socioeconomic changes for its beneficiaries. Therefore, this group is the central factor of the Cartesian plane, while the others are around it, with different degrees of proximity. It is observed that for the MLA to meet the established goals, it is necessary to understand the reality of these families, establish the most viable way to reach the households and supply this energy [traditional or by a photovoltaic system] and understand how the installation and maintenance of the systems will be carried out. Because of this, the government uses contracts with companies providing these services in each region.

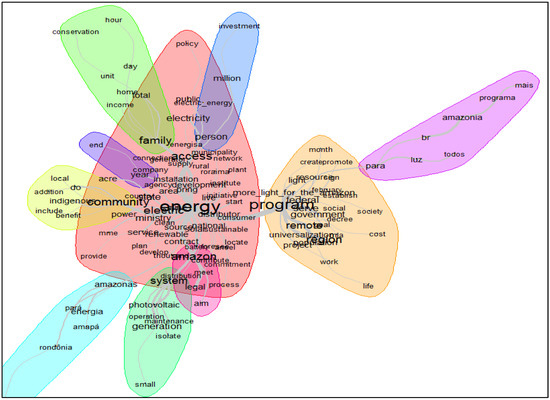

The similarity analysis was used as a means to detect the degree of connection between the elements identified in the analyzed corpus [Figure 3]. Through it, it is possible to observe that, for the implementation of the MLA program, the government acts as a key figure of connection between the need for access to electricity, presented by families located in remote areas of the Legal Amazon, and the need of concessionaires, permit holders and those authorized for energy installation and distribution services to obtain more customers and/or services. These deficiencies permeate the government’s need to reach out to these families and ensure that this public policy is implemented.

Figure 3.

Connection between descriptive elements from the similarity analysis.

However, the most viable means of guaranteeing that these needs are met is through the execution of contracts. Thus, the companies responsible for each state of the Legal Amazon are responsible for accessing and implementing the most suitable system for each location, as well as meeting the required goals. The population has access to electricity, either traditionally or through photovoltaic systems, and the government guarantees the universalization of this service. Thus, it is possible to generate the expected socioeconomic development in these regions through the involvement of communities in the systems’ operation and maintenance processes.

The communities are engaged through educational initiatives on how to use electricity safely, expressing a direct relationship between the program, the concessionaires and society [Figure 3].

Because of the research carried out, it is possible to observe that the electrification programs, initially, could not meet their objectives due to the absence of strategies and action from the state. Only after 2003, with the creation of the program Light for All [LPT], did it start to act as a key actor in the development of public policies, ensuring that the rural population had access to electricity, as well as reconciling this action with the interests of private companies [concessionaires]. However, the first referrals given to the program show that, at least for now, it is limited, in practice, to supplying electricity for the minimum needs of communities, restricted to domestic use [31]. Thus, it began to act as a supervisor, as these works, although carried out by private companies, are carried out in its name.

5. Conclusions

This research aimed to analyze the MLA program as a means to identify the role of each of the parties involved in the concession process [government and private companies] and the limitations faced for the success of the program. Through the information presented, it is concluded that the government plays the role of the inducing agent and supervisor of the process. It acts as an inducer when developing public policies that aim to overcome the lack of access to electricity in communities located in remote regions of the Legal Amazon. In addition, the government also plays a supervisory role, ensuring that concessionaires comply with the objectives and targets established in the concession contracts.

On the other hand, private companies have the role of implementing the actions foreseen in the MLA program. They are the ones that assume responsibility for the generation, transmission, distribution and sale of electricity in the remote regions covered by the program. Electric power concessionaires have the task of providing energy to communities through the necessary and adequate infrastructure to meet local demands.

One of the approaches adopted by the program is the use of solar generation microsystems, which brings significant benefits. These systems allow a reduction in operating costs, minimize environmental impacts and avoid excessive dependence on inflexible thermoelectric plants. Furthermore, by concentrating the electricity generation and distribution process in a single actor, there is an improvement in the organization of the governance structure. In this way, the disorganization that normally affects the governance of the electricity sector is overcome.

This more integrated and centralized approach contributes to the more efficient and coordinated management of electricity-related activities. By eliminating fragmentation and promoting the concentration of responsibilities, the program seeks to optimize decision-making processes, ensure greater efficiency in the implementation of actions and strengthen coordination between the different parties involved.

Furthermore, by focusing on microgeneration from renewable sources, the program also seeks to promote environmental sustainability. The use of solar energy as the main source of generation contributes to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, as well as to the preservation of natural resources in the Amazon region.

However, despite the benefits of the program, it is important to recognize the challenges and limitations it faces, especially given the characteristics of the Amazon region. The Amazon is marked by a complex geography, with vast areas of difficult access, low population density and unique environmental challenges. These characteristics make the expansion of the conventional electrical grid a challenge, especially in small towns, where the financial return on investment may be impractical.

This reality contributes to the increase in the costs of implementation and operation of electrical infrastructures, which can compromise the economic viability of concessionaires. However, through grants, the government minimizes these problems, as well as avoids the transfer of risk to the end user in the name of local socioeconomic development. Even so, the expansion of photovoltaic generation as a solution to meet isolated systems also faces additional challenges. Two key factors are the high logistical costs and the lack of qualified local professionals. In remote regions, the operation and maintenance activities of electrical systems involve greater complexity due to adverse geographic and environmental conditions.

In this context, the need arises for a more integrated approach, in which the private sector and communities play a more active role in the operation and maintenance of systems. Community participation becomes crucial to overcoming logistical challenges and ensuring project sustainability. By involving residents, it is possible to promote training and skills development, making them an integral part of the management and maintenance of electrical systems.

In addition, it is important to explore strategic partnerships and encourage technological innovation to face the specific challenges of the Amazon region. This may include developing solutions tailored to local conditions, such as the use of advanced monitoring and control technologies, energy storage systems and the integration of complementary renewable energies.

Thus, by recognizing the limitations imposed by the characteristics of the Amazon region, it is possible to adopt more flexible and collaborative approaches involving the private sector, local communities and the use of appropriate technologies. Only then will the electrification program in the Amazon be able to effectively face the challenges and achieve its objectives of bringing electricity to remote communities, promoting socioeconomic development and improving the quality of life of these populations.

This program shows that the government, in partnership with private companies, is seeking strategies to overcome limitations and integrate isolated communities. This involves the search for adequate financing, the promotion of strategic partnerships and the adoption of innovative and sustainable solutions for the generation and distribution of electric energy. Therefore, this study contributes to understanding the importance of public policies aimed at families found in a situation of exclusion and without access to essential products/services for social well-being. In addition, it demonstrates the importance of public managers being equipped with information before implementing public policies.

In the process of the research and analysis of the MLA program, it was difficult to obtain detailed information about the program, as well as acquire data from concessionaires and responsible government agencies. This lack of transparency and access to more in-depth information makes it difficult to fully understand how the program works and the impacts achieved.

Given this scenario, it is pertinent and opportune to carry out additional studies and consultations to investigate the feasibility of operating and maintaining the power generation systems implemented in the communities that benefited from the program. This more in-depth analysis will allow for a more precise understanding of the challenges faced by communities in the management and conservation of these systems, as well as identify opportunities for improvement and ensure the sustainability of these electrification initiatives.

To do so, it is essential to understand the involvement of local communities, the role and capacity of municipal governments and other actors in the coordination structure of actions. Through dialogue and the exchange of knowledge, it will be possible to obtain more precise information about the effectiveness of the program, as well as to identify possible gaps or difficulties in the operation and maintenance of energy generation systems. Furthermore, it is important to encourage the availability of more detailed and up-to-date data, ensuring greater transparency and facilitating future research and analysis.

These studies and consultations can cover a wide range of aspects, such as the capacity of the communities to assume responsibility for the operation and maintenance of the systems, the availability of technical and financial resources for these activities, the logistical challenges faced in the remote regions of the Amazon and the necessary training so that communities can efficiently manage these power generation systems.

The results of these surveys and consultations can provide valuable subsidies for the improvement of the program, allowing the implementation of more effective measures to guarantee the sustainable and long-term operation of the energy generation systems in the communities of the Amazon. In addition, they will contribute to strengthening transparency and accountability, enabling a better understanding of the results achieved and the necessary improvements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.d.S.P., F.d.L.B. and F.I.L.S.; methodology, M.A.O.S.; software, M.A.O.S.; validation, F.d.L.B., T.A.V. and M.A.O.S.; formal analysis, M.A.O.S.; investigation, J.d.S.P.; resources, F.d.L.B.; data curation, J.d.S.P. and F.d.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.d.S.P. and F.I.L.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A.O.S. and T.A.V.; visualization, F.d.L.B. and M.A.O.S.; supervision, F.d.L.B. and M.A.O.S.; project administration, M.A.O.S.; funding acquisition, F.d.L.B. and M.A.O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and the APC was funded by PROPPIT/Federal University of Western Pará through Edital 03/2022 [Programa de Apoio à Produção Científica Qualificada].

Data Availability Statement

The documents studied were Decree No. 10.221, of 5 February 2020, which establishes the program More Light for the Amazon, in view of the provisions of Art. 13, item I, of Law No. 10. 438, of 26 April 2002 (BRASIL, 2020), to promote the universalization of electric power service throughout the national territory; the Program Operationalization Manual, which defines the operational structure and establishes the technical and financial criteria, procedures and priorities that will be applied in the Program (MME, 2020); and Terms of Commitment between service providers and the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME, 2020), made available in monitoring the services provided in the states. In addition, journalistic materials and scientific articles that address the topic and support the information presented were used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cassaro, P.M.; Rego, E.E.; Parente, V.; Ribeiro, C.O. The Brazilian Sector of Electricity Transmission: Entrance of Spanish Companies. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2016, 14, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lascio, M.; Barreto, E.F. Energia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável Para a Amazônia Rural Brasileira: Eletrificação de Comunidades Isoladas. 2009. Available online: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/567794/1/solucoes_energeticas_para_a_amazonia.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- De Sousa, H.A.; dos Santos, M.A.; de Almeida, L.C.P. Gestão de resíduos sólidos: Um relato do serviço no contexto Amazônico. Rev. Bras. Adm. Científica 2021, 12, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEMA—Instituto de Energia e Meio Ambiente. Elétrica na Amazônia Legal: Quem Ainda Está Sem Acesso à Energia Elétrica? 2020. Available online: https://energiaeambiente.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/relatorio-amazonia-2021-bx.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Brasil Ministério de Minas e Energia—MME. Acompanhamento dos Atendimentos nos Estados—Ministério de Minas e Energia. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/energia-eletrica/copy2_of_programa-de-eletrificacao-rural/acompanhamento-dos-atendimentos-nos-estados (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Saneamento Ambiental. Programa Mais Luz Para a Amazônia. Available online: https://www.sambiental.com.br/noticias/programa-mais-luz-para-amazonia (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Brasil. Decreto n.o 10.221, de 5 de Fevereiro de 2020. Institui o Programa Nacional de Universalização do Acesso e Uso da Energia Elétrica na Amazônia Legal—Mais Luz Para a Amazônia. 2020. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/decreto/D10221.htm (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Brasil. Manual de operacionalização do Programa Mais Luz para a Amazônia. Ministério de Minas e Energia. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/energia-eletrica/copy2_of_programa-de-eletrificacao-rural/normativos/documentos/manual_de_operacionalizacao_do_programa_mais_luz_para_a_amazonia_edicao_final.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- De Abreu, B.V.; Silva, T.C. Novos paradigmas para a Administração Pública: Análise de processos de concessão e parceria público-privada em rodovias brasileiras. Adm. Pública Gestão Soc. 2009, 1, 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, P.B.M. Aspectos econômicos da produção agrícola do capim-elefante. In Anais do 3o Encontro de Energia no Meio Rural, AGRENER. Campinas. 2000. Available online: http://www.proceedings.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=MSC0000000022000000100032&lng=en&nrm=iso (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Pires, R.R.C. Implementando Desigualdades: Reprodução de Desigualdades na Implementação de Políticas Públicas; IPEA: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/9323 (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Werner, D. Neoliberalização e Mercadejação na transmissão de energia elétrica no Brasil: O caso do Amapá. CGPC. 26 August 2021. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/cgpc/article/view/83212 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Picciotto, S. Capitalismo corporativo e a regulação internacional da concorrência/Corporate capitalism and the international regulation of competition. Rev. Direito Práxis 2016, 7, 530–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justen Filho, M. As diversas configurações da concessão de serviço público. Rev. Direito Público Econ. RDPE 2003, 1, 95–136. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, G.; França, P.H. É Preciso Isonomia Vompetitiva Nas Privatizações do Setor Elétrico. Bol. Conjunt. 2019, 8–11. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/bc/article/view/89067 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Wu, Y.; Song, Z.; Li, L.; Xu, R. Risk management of public-private partnership charging infrastructure projects in China based on a three-dimension framework. Energy 2018, 165, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, W.W. Contract networks for electric power transmission. J. Regul. Econ. 1992, 4, 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, W.W. Electricity market restructuring: Reforms of reforms. J. Regul. Econ. 2002, 21, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque Sgarbi, F.; Uhlig, A.; Simões, A.F.; Goldemberg, J. An assessment of the socioeconomic externalities of hydropower plants in Brazil. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matosinhos, L.A. Universalização do Acesso à Energia Elétrica: Uma Análise em Municípios Mineiros; Universidade Federal de Viçosa: Viçosa, Brazil, 2017; Available online: https://www.locus.ufv.br/handle/123456789/20042 (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Gomes, R.D.M.; Jannuzzi, G.D.M. Eletrificação Rural: Um levantamento da legislação. In IV Encontro de Energia no Meio Rural, AGRENER. Campinas. 2002. Available online: http://www.proceedings.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=MSC0000000022002000100060&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Morrison, C.; Ramsey, E. Power to the people: Developing networks through rural community energy schemes. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Camargo, E.J.S. Programa Luz Para Todos-da Eletrificação Rural à Universalização do Acesso à Energia Elétrica-da Necessidade de Uma Política de Estado. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. Available online: https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/86/86131/tde-22092010-010215/en.php (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Brasil Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica—ANEEL. Universalização. 2016. Available online: https://antigo.aneel.gov.br/universalizacao (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Justen Filho, M.; Pereira, C.A.G. Concessão de serviços públicos de limpeza urbana. Rev. Direito Adm. 2000, 219, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.P. Concessão pública: Um empreendimento público comercial. Rev. BNDES 1996, 3, 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu, C.-W. Lessons from the World Bank’s solar home system-based rural electrification projects [2000–2020]: Policy implications for meeting Sustainable Development Goal 7 by 2030. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2820–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeshqab, F.; Ustun, T.S. Lessons learned from rural electrification initiatives in developing countries: Insights for technical, social, financial and public policy aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, E.F.; Silva, W.A.C.; Araújo, E.A.T. Identificação das variáveis determinantes da eficácia de uma concessão pública, segundo a percepção de seus usuários. Rev. Gestão 2015, 22, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.F. Effective solutions for rural electrification in developing countries: Lessons from successful programs. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.L.; Silva, F.B. Universalização do acesso ao serviço público de energia elétrica no Brasil: Evolução recente e desafios para a Amazônia Legal. Rev. Bras. Energ. 2021, 27, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G. A articulação Entre Regulação, Defesa da Concorrência e Proteção do Consumidor Nos Setores de Telecomunicações, Energia Elétrica e Saneamento Básico. FGV EAESP—Gvpesquisa—Relatórios Técnicos. 2001. Available online: http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br:80/dspace/handle/10438/3042 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Mccahery, J.A.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T.; Becht, M.; Brav, A.; Brown, S.; Coffeldt, M.; Feigelson, J.; Fox, M.; Gillan, S.; et al. Behind the Scenes: The Corporate Governance Preferences of Institutional Investors. J. Financ. 2016, 71, 2905–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton William, W.; McCahery, J.A. Regulatory Competition, Regulatory Capture, and Corporate Self-Regulation. Fac. Scholarsh. Penn Carey Law 1995, 73, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha Sampaio, K.; Ivna Pinheiro Costa, E. Administração Pública Gerencial e o Princípio da Eficiência: Origem, Evolução e Conteúdo. 2018. Available online: https://ww2.faculdadescearenses.edu.br/revista2/edicoes/vol9-2015.1/artigo3.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Pollitt, M.G. The European Single Market in Electricity: An Economic Assessment. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2019, 55, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.N.; Naeem, M.; Iqbal, M.; Imran, M. Economically efficient and environment friendly energy management in rural area. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2017, 9, 015501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. Politics and economics in weak and strong states. J. Monet. Econ. 2005, 52, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. Oligarchic Versus Democratic Societies. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2008, 6, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M. Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. Policy capacity in public administration. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M. The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results. Eur. J. Sociol. 1984, 25, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Y.W. Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. Am. J. Sociol. 1990, 95, 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A. Como Elaborar Projetos de Pesquisa, 4th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2002; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/31031805/9482_lista_de_revisao_1Âo_bimestre_com_respostas_direito.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo, 70th ed.; Persona: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011; 279p. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, Y.S.O. O Uso do Software Iramuteq: Fundamentos de Lexicometria para Pesquisas Qualitativas. Estud. Pesqui. Psicol. 2021, 21, 1541–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallery, B.; Rodhain, F. Quatre approches pour l’analyse de données textuelles. XVIe Conf. AIMS 2007, 28, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, B.V.; Justo, A.M. IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas Psicol. 2013, 21, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratinaud, P.; Marchand, P. L’analyse de Similitude Appliquée Aux Corpus Textuels: Les Primaires Socialistes Pour l’élection Présidentielle Française. In Proceedings of the 11èmes Journées Internationales d’Analyse Statistique des Données Textuelles, Liège, Belgique, 13–15 June 2012; pp. 687–699. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica—ANEEL. Resolução homologatória n.o 2.891. 29 June 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/energia-eletrica/copy2_of_programa-de-eletrificacao-rural/normativos/documentos/reh-2-891-2021.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Ohara, A.; Goldemberg, J.; Barata, L.O. Enfrentamento de Crises Hídricas: O Papel das Energias Renováveis na Construção de Uma Matriz Elétrica Resiliente e de Menor Custo. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Clima e Sociedade. 2021. Available online: https://59de6b5d-88bf-463a-bc1c-d07bfd5afa7e.filesusr.com/ugd/d19c5c_6e6380eb61e24746b5d26bc2d7d752c6.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).