Abstract

Risk management is critical for corporate finance management systems, in addition to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable development (SD) programs. Stakeholders need risk information to make informed judgments as to their involvement. No studies exist to date concerning disclosure of non-financial and financial risks in corporate annual statements and Polish strategic sector company reports. The authors sought to determine whether energy companies disclosed risks in non-financial annual reports in 2011–2020 (e.g., CSR, integrated, and board activity reports), and whether one can assess threats, including business activity risks and SD, based on these reports. We assessed the reports of all large Polish energy companies on a three- and five-degree scale to develop a model for risk information disclosures. We have three key empirical findings. Only half the analysed companies disclose annual financial data, threats, and risks. Less than half have implemented and operate enterprise risk management systems. The current ‘soft’ regulatory solutions give energy companies appreciable risk disclosure options, which often is counterproductive. We suggest developing a single integrated European Union (EU) regulation (e.g., directives, standards, or official principles) for non-financial risk disclosures. Our model classifies Polish energy company risks to business activity operations and risk management systems. Other sectors can use this universal model. Our results constitute progress in identifying company risks and may encourage continuing studies of other energy companies, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), which should be intensively developed. Research should also occur in other strategic sectors.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable development (SD) ideas and the problem of non-financial information disclosures in company annual reports are important worldwide research subjects. Stakeholders report growing demand for such disclosures, including threats and business activity risks. We show that current Polish energy company practices do not generally meet potential investors, shareholders, and other stakeholders (Stakeholders) needs and require stronger disclosure regulation.

Many theories interpret CSR and SD, e.g., [1]: environmental, social, instrumental, ethical, and political theories. The last decade has produced many CSR and SD definitions. Both CSR and SD are accepted as global socio-economic concepts integrating different economic, social, and environmental objectives [2]. For example, the European Commission (EC) in its Green Paper [3] defined CSR as an idea “whereby an enterprise integrates social, economic and environmental concerns in its business activity and its interaction with its stakeholders on a voluntary basis”. The current EU strategy defines CSR simply as “the responsibility of companies for their impacts on society” [4]. The non-financial corporate information for stakeholders’ disclosures is an EU priority [4], because effective communication and dialogue between socially responsible companies and Stakeholders are key CSR and SD factors e.g., [5,6,7,8,9,10]. The practical instrument for such communication is the CSR report (CSRR) or integrated report (IR).

In the past decade, Polish CSRRs and IRs have increased significantly, reflecting current Polish annual reporting practice and helping meet Stakeholder needs. Currently, a lively debate continues regarding the quality and usefulness of annual corporate statements, including CSRRs and IRs [11,12,13,14,15,16]. CSRRs and IRs are effective communication tools concerning economic, social, and environmental initiatives, but Stakeholders complain that annual data do not contain detailed information on risks affecting operations [17,18,19].

Polish annual financial statements continue to be basic, unbiased information sources. Financial statements can identify basic risks linked to the company’s assets, finances, and financial results but do not allow determination of other operating risks, such as business environment risks, capital markets, management, and measurement of non-disclosed intangible values or CSR. Such information is thus incomplete, and does not fully meet user expectations. Financial audits create the greatest trust in company data but are obligatory only for large- and medium-sized companies. Therefore, their usefulness is seriously limited for Stakeholder decisions. Thus, IRs partially fill the Polish information gap, where both non-financial and financial information are presented, including CSR and SD disclosures. Reporting effective risk management for Stakeholders is critical to implement CSR and SD and for transparency in corporate finance management systems. Annual CSRRs and IRs constitute the basic company information source; their quality is thus critically important.

We investigated this area to meet growing Stakeholder demand for information on threats and risks disclosed in Polish socially responsible companies. We analysed the quantity, quality, and content of non-financial reports (separate CSRRs, IRs, and board activity reports) as information sources on Polish energy company risks. For CEE countries, including Poland, energy sector risk reporting is very important for CSR and SD. Energy projects, green energy development, and financial stability are important to citizens and politicians everywhere.

For three years, Poland has seen rising energy investments, shrinking profits, and high raw material costs. Current threats and risk management systems are key CSR factors for Stakeholders and the country’s economy. Polish and EU economic disruptions may also affect energy company performance; fuels, gas, and mining companies; project subcontractors, and customers e.g., [20,21,22,23]. It is thus important to identify new energy company risks.

This article aims to determine whether Polish energy companies disclose risks in annual reports and whether it is thereby possible to assess risks. We collected data from corporate annual non-financial reports (CSRRs, IRs, and board activity reports) and company websites.

The study consists of five sections (after this introduction):

- Section 2 describes CSR reporting in the literature and an empirical research review.

- Section 3 shows CSR and integrated reporting of Polish risk information disclosures.

- Section 4 describes the sample, methodology, data sources, and research questions.

- Section 5 presents our research results and answers our research questions. We assess the: (1) type and length of annual reports; (2) energy company disclosure scope; and (3) quality of non-financial corporate reports. We conclude with our concept for management risk systems, a model for threat disclosure in non-financial reports, and a classification of energy company business activity risks and SD.

- Section 6 offers general conclusions, research limits, and further research directions.

In this study, we review the literature, demonstrate the empirical research, and propose a disclosure model for threats and business activity risks from financial statements and non-financial reports. Our results contribute to CSR studies, as no analysis exists concerning risk disclosure in annual reports, and may encourage similar studies elsewhere. They show a risk reporting model of interest to the EU, especially CEE countries. CEE countries have been constantly seeking new energy investment and development solutions (e.g., green energy sources). These conclusions raise the awareness of researchers, companies, regulators, and Stakeholders.

2. Literature and Empirical Research

For 30 years, CSR, SD and sustainability reporting have been important in academic and business circles, and the topic of many empirical studies. For this study, numerous papers published outside Poland are also important. Many international studies discuss CSR and SD in companies, industries, or countries e.g., [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Fifka [31] examined 186 studies, grouping them by their geographic origin. Fifka [31] indicates that authors across countries use different methods and paths to report analysis. Many authors show diversity in CSR reporting based on choices of Stakeholder engagement strategies and/or the relationships with specific Stakeholders e.g., [32]. Other authors show increasing interest in non-financial information and IRs that include financial and corporate governance, in addition to other economic, environmental, and social performance. e.g., [33]. A multi-author study systematised the use of 600 indicators in CSRRs e.g., [34]. Many indicators appear in CSRRs and IR, but few are commonly used [15].

Many studies focused CSR research on accounting e.g., [35,36], but few relate to disclosed information on risks. For example, Souabni [37] shows the theoretical and practical problems of narrative reporting, including risk and non-financial disclosure. Miihkinen [38] describes the factors that affect the quantity and quality of company disclosures, in addition to the impact of national reporting standards and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) on CSR and risk reporting. Other research discusses the quantity and scope of risk disclosures e.g., [39,40,41]. Most disclosed risks concerned the company’s financial condition. Companies are reluctant to disclose non-financial risks. A few companies identified and described future risks. Other authors also investigated whether disclosed risk is correlated with industry and size [39,42].

Many authors show that smaller companies disclosed far fewer risks e.g., [42]. Alzear and Hussainey [43] studied Saudi annual reports. They describe 11 key risk categories; within key categories, they distinguished some 47 subcategories. Over 63% of disclosed risks dealt with financial data, including market risks (23%). Less than 37% of the information addressed non-financial risks, including operating risks (17%). Lajili and Zeghal [44] studied 300 Toronto Stock Exchange (TSE) company annual reports. They assessed the TSE-listed company reports for risk disclosure quantity and quality, concluding that these companies disclose much risk data in optional and obligatory disclosure areas. In turn, Amran et al. [45] explored Malaysian risk management disclosures. Linsley and Shrives [42] investigated environmental risk disclosures, concluding that environmental information reporting is not uniform. Moreover, environmental information is not presented clearly, because such risks are not quantified. Other authors confirmed that the lack of risk disclosure models considerably reduced the usefulness of risk information e.g., [44]. Many authors examined correlations between risk disclosures in annual reports and the company’s market value, e.g., [46,47].

Research on annual CSR reporting occurs quite frequently in CEE, including Poland, and in other developing countries elsewhere. Many authors studied reporting practices of their respective countries’ companies. Many studies have investigated internal and external factors of CSR reporting—for example, whether internal (e.g., industry and size) and external factors (e.g., Stakeholder pressures) impact risk disclosure e.g., [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Horváth et al. [50] show annual socially responsible listed company reporting practices in nine CEE and two Western European countries (Germany and Austria). Albu and Klimczak [51] show the differences and commonalities that characterise the CSR reporting of companies operating in three CEE countries (Poland, Romania, and Slovenia) and Turkey. These authors also presented the diversity of practices and approaches existing in those four countries. Hahn and Kühnen [53] show determinants of sustainability reporting, including a theory review (including legitimacy, stakeholder, signalling, and institutional theory), trends, results, and new research directions. Ali et al. [54] show the factors driving social responsibility disclosure in CEE and other European developing countries. These authors find that company characteristics such as industry sector, size, profitability, and corporate governance principles appear to accelerate the EU social responsibility reporting regulations and agenda. Other authors have also attempted to fill the reporting practices gap in this under-researched region [55,56].

During our literature review, we did not identify research in CEE and developing countries that shows key aspects in risk disclosure in non-financial annual reports.

Non-financial annual reporting also has drawn attention from Polish authors. Many Polish empirical studies have focused on annual large enterprise or Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE)-listed company CSRRs and IRs. For our purposes, several Polish papers are relevant.

Many authors note that to be useful to Stakeholders, a non-financial corporate report should display reliability, cohesion, and comparability e.g., [11,12,15,17,57,58,59,60]. Szczepankiewicz [12] discusses issues related to ensuring report-to-report comparability. Samelak [58] proposed the first theoretical integrated reporting model for Polish socially responsible companies. Szczepankiewicz [12] systematised the principles of defining the range, scope, quantity, and quality of Polish CSRRs and IRs. Subsequently, Szczepankiewicz and Mućko [15] studied CSR reporting models currently used by such companies. Szadziewska [59] divided large and WSE-listed companies disclosing CSR information into three groups, namely those that: (1) formally apply and disclose only regulatory compliance issues; (2) disclose information on economic, social, and environmental problems and their solutions; and (3) disclose detailed information relevant to CSR and business development. Szczepankiewicz [12] analysed annual reports searching for information building the firm’s market value. Szadziewska [59] and Szczepankiewicz [11,12] concluded that enterprises use reports only to create a positive company self-image and not to provide comprehensible, credible, and relevant non-financial information to Stakeholders. They concluded that enterprises use CSRRs to create a positive company self-image and not provide useful non-financial information to Stakeholders.

A study by Szczepankiewicz shows that Polish companies seldom disclose risks in their CSRRs. Krasodomska [60] also postulated that, in addition to GRI indicators, companies should also publish other information in annual reports. Other authors discuss many detailed issues of CSRRs, using examples from various industries in Poland. There are many empirical studies of non-financial Polish annual reports focusing only on CSR and integrated reporting. Samelak [58] predicts that IRs will eventually replace CSRRs in Poland. Many Polish authors explore the use of annual CSRRs and IRs, but only Szczepankiewicz [17] shows that Polish large and small companies rarely disclose risks.

Many authors show aspects of disclosure of financial risk identifiable to Stakeholders from disclosed balance sheet data e.g., [18,19,61,62,63,64,65]. For example, Szczepankiewicz [18,19] examined risks specified in the Polish Accounting Act (PAA) that must be disclosed in the activity report, and risks presented in the management commentary in accordance with IFRS.

In the global literature, many authors also criticise certain tendencies in CSR reporting. For example, Boiral [66] shows that 89% of negative information either was reported only partially or not disclosed. Boiral claims that most companies present an exaggerated image of their external awards, positive achievements, and social commitments.

Many studies focused on camouflaging corporate unsustainability in CSRRs e.g., [67]. Other authors point to certain aspects of corporate reputation and corporate hypocrisy in CSR reporting, e.g., [68]. Szczepankiewicz [12,17] shows Polish public company Stakeholders (e.g., energy companies and others from strategically important Polish sectors) want to access clear, comprehensive risk information.

Risk identification, assessment, and disclosure aspects in Polish non-financial reports (e.g., CSRRs, IRs, and board activity reports, including energy companies) from strategic sectors have not yet been analysed. No author (prior to this study) has analysed risks in Polish CSRRs and IRs. The authors focus primarily on threat disclosures and whether continued company operational risks and SD can be presented adequately.

3. Polish CSR and Integrated Reporting Regulations for Risk Information Disclosures

CSR and SD have significance for EU political and legislative activities [15]. Assessing current threats, risks to the company’s future condition, and going-concern risk is a complex process for Stakeholders. To meet Stakeholder needs, annual reporting has recently evolved quickly. Corporate reporting is now a worldwide subject for lively discussion. Financial information disclosure has long been codified, but standardisation of risk and other non-financial data is far more complicated.

Various global organisations have undertaken many such standardisation initiatives, including the Global Social Initiative (GSI), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the GRI, the EC and the UN Global Compact. Polish companies generally use GRI and IIRC documents [69]. Like Poland, many international organisations use the GRI-G4 documents [70]. In Poland, the GRI-G4 is often used with international standards of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and other frameworks, concept, guidelines, and initiatives (e.g., ISO 14001, ISO 17025, ISO 18001, ISO 22300, ISO 26000, ISO 27001, ISO 31000, ISO 37001, ISO 45001, ISO 50001, and ISO 9001, in addition to COSO II-ERM, or FERMA).

In 2010, the EC began a discussion for standardisation of non-financial information in corporate annual reporting and then announced three documents: Directive 2013/34/EU [71], Directive 2014/95/EU [72], and the Commission Recommendation (CR) 2014/208/EU [73]. Polish regulatory authorities have introduced national regulations regarding obligatory public company reporting of risks. In 2017, the two above-mentioned directives and CR 2014/208/EU were included in national legislation in the PAA [74] and the National Accounting Standard No. 9 (NAS 9)—Activity Report [75]. Polish public companies must prepare “Non-Financial Statements” and “Corporate Governance Statements” (CGSs) as standalone parts of the “Board’s Activity Report”. Listed company CGSs must contain risk information. The year 2017 also saw the publication of the Non-Financial Reporting Standard (SIN) [72]. The Polish SIN is a short version of the GRI standard. However, currently, most Polish CSRRs or IRs are prepared based on the GRI-G4.

Polish companies present financial information in annual financial statements, which makes it possible to identify multiple business activity risks. Different annual financial statement elements allow Stakeholders (acting alone or with professional help) to detect important risks. The PAA [74] defines the obligatory financial statement components and the required structure, scope, and content of information. Financial statements have the following elements: (1) balance sheet; (2) statement of changes in equity; (3) profit and loss account; (4) cash flow statement; and (5) financial notes. From the obligatory financial statement components, Stakeholders can identify only financial risks.

Stakeholders can identify other business activity risks from financial statement notes, consisting of (1) the introduction and (2) additional notes and explanations.

The introduction contains the management board statement on the company’s ability to continue as a going concern and any related risks. Additional notes and explanations should contain: (1) an overview of any uncertainty regarding the ability to continue as a going concern; (2) a description of already initiated or planned actions aimed at eliminating such uncertainty; and (3) market risks (including price change, foreign exchange, and interest rate risk) and other operating risks (how operating assets/liabilities, and the company’s strategy, marketing policy, building and maintaining production capacity, and supply and sales logistics, may affect the company).

Table 1 shows the main risk types in Polish annual financial statements.

Table 1.

Identification of business activity risks in annual financial statements.

We conclude that financial statements do not inform Stakeholders about other risks, including but not limited to: (1) the company’s business environment and activities; (2) capital markets; (3) management and measurement of undisclosed intangible values (e.g., intellectual capital); and (4) CSR activity. The above-mentioned risks should thus appear in non-financial reports, e.g., the CSRR, board activity report, or the non-financial part of the IR.

CSRRs present basic data concerning assets, liabilities, revenues, costs, profits from the annual financial statements, and risks that the company wants to disclose. In turn, all IRs include five financial statement elements (See Table 1) and, additionally, the board activity report. The first IR financial component is the annual financial statement; the second includes the company’s activity report and other non-financial information. Currently, only large companies must submit such a report (based on PAA and NAS 9 guidelines).

According to the International Accounting Standards Board’s recommendations, a management commentary can replace the activity report. The board activity report should present the risks specified in the PAA and NAS 9, including [74,75,76,77]: (1) expected new company business activity and development threats; (2) financial condition (from economic and financial analysis); (3) strategic risks; (4) operational risks; (5) trade risks; (6) credit risks; (7) financial instrument risks; (8) price change risks; (9) financial risk management system objectives and methods; (10) cash flow risks; (11) Treasury stock purchase; (12) other significant risks; and (13) corporate governance principles (but only for publicly listed companies).

4. Research Methodology and Empirical Data

4.1. Description of the Sample and Methodology

We performed an empirical study of 56 CSRRs and IRs of all Polish energy companies using a content analysis method. We researched specific analytical units in the report texts (inter alia key words, descriptions, sentences, tables, schemas, charts, or other segments). Many scientists use this method to study company reporting, which can be easily replicated [15,78]. Moreover, based on her experience as an auditor, one author assessed the reports on a three- and five-degree scale to develop a risk information disclosure model in non-financial corporate reports published by socially responsible energy companies.

To begin, we collected all Polish energy company CSRRs and IRs from 2007 to 2020. All reports were originally submitted for a competition from 2007 to 2020 for “the Best CSR Report in Poland”. Next, we coded the CSRRs and IRs to measure their diversity and quantity.

The issue was to determine whether Polish energy companies disclose risks in the CSRRs or IRs, and whether it is possible to assess future business activity risks from those disclosures. We formulated four research questions (see: RQ1–RQ4 in Section 4.2). We present empirically the scope of information in non-financial annual reports of Polish energy companies, a strategically important sector for Polish SD. Stakeholders are interested in identifying business activity and other risks affecting these companies.

4.2. Description of the Data Sources and Research Questions

The Polish energy sector includes 15 large companies. Many prepare annual CSRRs or IRs. Publishing CSR and SD information is voluntary in Poland.

Our research sample consists of two groups of annual reports:

- 56 non-financial reports (41 CSRRs and 15 IRs) submitted for “the Best CSR Report in Poland” competition in 2008–2021.

- Eight annual WSE-listed company reports, indexed as of 30 June 2021.

“The Best CSR Report in Poland” competition started in 2007. From 2007 to 2021, 460 reports were submitted. The first Polish CSRRs were submitted in 2008 (13 reports—but only one energy company). Submissions have increased every year, with 55 reports (four energy companies). Only three energy companies have regularly submitted reports for the competition since 2012. Eleven reports received awards: PGNiG Group (PNGiGG), Energa Group (EnergaG), and Tauron Polska Energia S.A. (TPE) (three each); Polskie LNG S.A. (PLNG) and GAZ-SYSTEM S.A. (G-S) (one each).

Table 2 provides an overview of participating Polish energy companies.

Table 2.

Overview of energy companies participating in “The Best CSR Report in Poland” competition.

Analysis shows many company annual CSRRs and IRs published in the same year (e.g., 2010 or 2020) provide then-current company conditions and management’s approach to risk disclosure. However, given a small sample of available annual reports (e.g., two to six energy company reports per year), analysing all such reports is very important. Therefore, we deliberately concentrated on all submitted CSRRs and IRs from the period 2007–2020. Our results may show the evolution in managements’ approaches to the annual reporting model, and especially the scope and structure of risk information. Moreover, we believe the results may show whether the disclosure evolution is more useful to Stakeholders.

Table 3 shows an overview of annual CSRRs and IRs by energy companies from 2007 to 2020. All analysed companies (between 2008–2021) are large.

Table 3.

Overview of energy company CSRRs and IRs (2007–2020).

Energy companies prepared all non-financial annual reports (CSRRs or IRs) until 2014 using GRI-G3.1. From 2015, energy companies have used GRI-G4.

The total volume of these reports covers 7243 pages, only 671 of which (9.26%) contain financial information. Basic financial information in such reports is important, because it may help Stakeholders identify financial and business risks.

Only five energy companies (G-S in 2011–2014 and 2019; PGEG in 2015–2018; TPE in 2016–2019; ENEA and Polenergia in 2020) published IRs. External reviewers audited all such IRs. TPE was the only enterprise publishing annual IRs in 2016–2020, disclosing all GRI-G4 socially responsible aspects and full company information. TPE is the only company whose reports contain elements and non-financial data mentioned in Samelak’s model [58]. All IRs have been externally verified, which enhances report reliability for Stakeholders [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88].

The remaining energy enterprises publish annual CSRRs. CSRRs have rarely been externally verified (only 19.51%—8 of 41; TPE for 2011–2012, EnergaG for 2013–2015 and 2018–2019, and PKPE for 2020).

We identified eight key Stakeholders for Polish energy companies, broken into 27 stakeholder categories (see: Table 3): (1) employees (full-time employees, potential employees, trade unions, labour inspectors); (2) investors (banks, corporate investors, strategic investors, private investors, brokerage houses, the WSE); (3) suppliers and subcontractors; (4) clients/customers (corporate customers, private customers, business partners); (5) society (residents and social leaders, public administration, local communities, the EU); (6) technical and industry organisations; (7) universities, researchers, and media; and (8) environment organisations (public environmental authorities and entities, the State Forests Authority, and other environmental non-governmental organisations).

We conclude that the clients, environment organisations, and employees are the most important Stakeholders (100% of companies). In 2017–2020, all reports include a management statement on the implemented principles of ethics or codes of ethics and anti-corruption (100%).

We also reviewed all WSE-listed energy companies reports to identify financial and business activity risks in 2020. In the WIG indices (WIG20, mWIG40, and sWIG80—total 140 companies), there are only eight energy companies. We included four WSE-listed energy companies that participated in “The Best CSR Report in Poland” competition in 2008–2021—PGNiGG, TPE, ENEA and PGE. The other companies did not participate. We also analysed whether the WSE-listed energy companies published non-financial reports (e.g., CSRRs or IRs in 2020 on company websites).

Section 5 analyses annual financial statements and board activity reports of WSE-listed energy companies for 2020. The IFRS and PAA (amended in 2017) specify the current form, content, and scope of financial statements, whereas NAS 9 and Article 46 of the PAA determine the scope and form of board activity report risk disclosures. In Poland, these regulations have not changed for four years. Therefore, the authors only analysed these reports for 2020. All annual financial statements and board activity reports have been externally verified.

Table 4 shows the analysis for WSE-listed energy companies.

Table 4.

Data on analysed corporate annual reports of WSE-listed companies operating in the energy sector (2020).

Three of eight WSE-listed energy companies (TPE, ENEA, and Polenergia) in 2020 posted their IRs in addition to the annual financial statements and the board activity report (Table 4). Furthermore, TPE, ENEA, and Polenergia participated in “The Best CSR Report in Poland” competition in 2020 (see: Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Other WSE-listed energy companies have not published CSRRs to date. We concluded that the board activity reports of only three of the eight companies, which contain a detailed presentation of business activity risks, deserve note (TPE, Polenergia, and MLS).

Ultimately, we believe that the analysed annual reports are the intentional and best choice for our research. However, the analysis of the 2020 WSE-listed energy company was used to report supplements and help achieve our research objectives, answer questions, define the disclosure model risk, and suggest the final conclusions.

As previously mentioned, the primary research problem was to determine whether Polish energy companies disclose risks in annual reports, and whether one can assess business activity risks from them. We set out to answer four research questions:

- RQ1—Does Polish CSR reporting give Stakeholders financial data and condition indicators?

- RQ2—Must Stakeholders search for business activity risk information elsewhere (e.g., annual financial statements or board activity reports)?

- RQ3—Is the scope of information disclosed in CSRRs or IRs sufficient to identify business activity risks and SD?

- RQ4—What recommendation—a conceptual model or other system-level changes—should we propose for energy companies, if any?

The answers depend on the scope and quality of information of the CSRRs and IRs. These socially responsible reports are forms of dialogue between the energy company and its Stakeholders. High-quality risk reporting is linked to a responsible approach to CSR and SD. Comprehensive annual reports reflecting current conditions and risks show social responsibility towards Stakeholders.

Companies experience many types of threats, including business activity risks and SD, as reflected in Hypothesis (H1): “A conceptual model embracing all the main aspects of threats to energy companies, including business activity risks and SD, can provide an analytical framework for CSRR or IR risk disclosures”. Stakeholders are interested in energy company business activity risk disclosures. Generally, Stakeholders do not have access to complete risk data. We believe a model for such disclosures in CSRRs or IRs is necessary. Such a model should combine research experience with a practical approach that Stakeholders expect.

5. Research Results

5.1. Type and Length of the Analysed Annual Reports

Corporate annual integrated reporting is relatively new in Poland and elsewhere. From 2016 to 2019, only four energy companies published IRs (G-S, GPECG, TPE, and PGEG), and half announced only CSRRs. Other energy companies announced CSRRs with separate annual financial statements. TPE’s IR volume (316 pages in 2016–2017, 518 pages in 2018–2019, and 523 pages in 2020) is significantly greater than that in other IRs. The IR by GPECG is the shortest, comprising only 43 pages.

The CSRRs by three companies are long (PGNiGG—122 pages in the report from 2014, EnergaG—176–281 pages in reports from 2015–2019, and Polenergia—136 pages in the report from 2019). The CSRR report by VEP (2019) is the shortest, comprising only 54 pages. The analysed CSRRs contain very little financial information (one page) (Table 2 and Table 4).

5.2. Scope of Risk Disclosures in Energy Company Annual Reports

- (A)

- Does Polish CSR reporting give Stakeholders financial data and condition indicators? (RQ1)

To help Stakeholders identify business activity risks, the energy company should disclose the board activity report and data from the annual financial statements on the company’s website. This information is entity specific.

Table 5 presents whether non-financial annual reports contain the financial and risk information. One author assessed the financial statement elements on a three-degree scale.

Table 5.

Financial data and information in annual CSRRs and IRs.

Table 6 presents information on company’s financial condition and risks in the analysed corporate annual reports. One author assessed the financial statement elements on a five-degree scale.

Table 6.

Information on company’s financial condition and risks in the analysed corporate annual reports.

The study showed that, from 2011–2019, only G-S presented all annual financial statement components in its IRs (profit and loss account, balance sheet, statement of cash flow, and additional notes). In the following years (2015–2020), only two companies (PGEG and TPE) presented the basic components in their IRs, and two more companies (ENEA and Polenergia) did so in 2020. Importantly, the analysed companies prepared an IR containing financial data with indicators. Furthermore, these companies published all components of their annual financial statements for 2015 to 2020 on the company website. Analysts using the annual financial statements can examine detailed information to identify future financial risk factors (See Table 1 and Table 5).

The other companies (PLNG and PKPE) did not present any financial statement data in their CSRRs. The financial information shown in the remaining CSRRs was limited to the following: (1) sales results (97.44%); (2) total assets (94.87%); (3) total equity (89.74%); and (4) financial results (92.30%). During 2013–2015 and 2018–2019, only EnergaG presented audited reports. From 2009 to 2019, the other analysed companies did not show such external audited reports, which is clearly negative.

- (B)

- Must Stakeholders search for business activity risk information elsewhere (e.g., annual financial statements or board activity reports)? (RQ2)

Table 6 shows whether stakeholders can find data on the company’s financial condition and risks in energy company CSRRs or IRs. One author assessed the risk information on a five-degree scale.

For the first time in 2011, G-S published an IR with all necessary data. PGEG published an IR in 2015–2018, TPE in 2016–2020, GPECG only in 2016, and Polenergia and ENEA only in 2020. These companies presented the basic financial indicators with a risk overview including CSR risk. Only TPE and G-S describe basic future financial and selected non-financial risks. TPE and G-S also show the measures taken to reduce these risks.

The analysis indicates that other energy companies did not show the financial indicators in their CSRRs. Some companies only provided an overview of selected non-financial risks. The other analysed companies presented only basic aspects of CSR risks (on environmental and social issues) in their CSRRs.

In recent years, only seven of the 15 companies have implemented a full Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) system based on ISO standards, e.g., ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 18001, ISO 27001, ISO 17025, ISO 22300, ISO 26000, ISO 27001, ISO 31000, ISO 37001, ISO 45001, ISO 50001, COSO II, and FERMA) (see Table 3). The remaining companies implemented only 2–3 selected basic ISO standards, e.g., ISO 9001 and ISO 14001.

We conclude that only three energy companies (G-S, TPE, and PGEG) systematically published their financial indicator overview and full risks (including CSR).

We further conclude that the CSRRs from 2007 to 2020 did not contain any information and data about financial, credit, or market risks. Stakeholders need to seek this information in the annual financial statements. Nevertheless, from 2009 to 2020, only seven of the 15 companies systematically posted the annual financial statements on their website (see Table A1 in Appendix A). Only five of the 15 companies are WSE listed. They post their annual financial statements on the WSE website (see Table 4). The non-WSE-listed energy companies did not post their financial statements on their website. Therefore, many Stakeholders mainly look at generally available (free-of-charge) CSRRs or IRs on corporate websites. Access to information sources is important to Stakeholders.

- (C)

- Is the scope of information disclosed in CSRRs or IRs sufficient to identify business activity risks and SD? (RQ3)

We conclude that the energy company CSRRs not containing information from annual financial statements and/or board activity reports do not allow Stakeholders to recognise and analyse all risks (see details of financial risk, including business activity risks and SD, presented in Table 1).

Many Stakeholders are also interested in operational information:

- Are there nuisances to the environment or local residents?

- Are there protests against the energy company?

- Are there administrative actions against the energy company by local government entities?

- Are there legal actions brought by other Stakeholders?

The lack of information in CSRRs or IRs on the above problems does not allow Stakeholders to identify and analyse the basic threats, including business activity risks and SD. The interested stakeholders can look for such information on corporate websites. We conclude that the Polish CSR reporting model currently used by energy companies does not show any operational and financial data.

- (D)

- What recommendation—a conceptual model or other system-level changes—should we propose for energy companies, if any? (RQ4)

Many energy companies voluntarily publish all elements of annual financial statements and audit reports on their websites. Publishing annual reports on websites is not obligatory in Poland. PAA amendments in 2016 lifted the obligation to publish such data on websites.

Only some energy companies publish all financial statement elements on their websites. We conclude that only seven of the 15 companies (PGNiGG, G-S, TPE, Polenergia, VEP, PGEG, and EnergaG) did so. The other energy companies did not disclose their financial information to Stakeholders.

We conclude that the obligation to ensure general (free-of-charge) access to financial statements on websites and/or to make publishing IRs obligatory should be restored.

We believe that only socially responsible organisations and theorists can develop a new integrated reporting standard that ensures the disclosure of risk information will meet EU Directives [72,73,74] and national regulations.

5.3. Discussion of Energy Company Annual Report Quality

Many world authors have conducted a lively discussion on socially responsible company non-financial report quality. Studies show that non-financial information published in non-financial statements is important for Stakeholders in assessing company performance, even if not directly related to financial statement data, e.g., [89,90,91,92,93]. All risk types may have major image-related, legal, or financial implications. These effects may influence the company’s going-concern continuity and SD. Thus reliable, current, and accurate risk data is important to Stakeholders.

Many authors confirmed that non-financial reports are often used to build image, e.g., [5,7,10,94,95,96,97]. Many authors, practitioners, and Stakeholders have criticised CSRRs. Studies show that the management boards that prepare annual CSRRs do not do so consistently, responsibly, and honestly, even if they prepare their reports in accordance with the GRI [47,94]. For example, Boiral [66] concluded that almost 89% of significant adverse threats and incidents were not disclosed in annual CSRRs.

Many authors discuss the quality of the new IRs published by socially responsible companies and their compliance with the International Investor Relations Federation Standard e.g., [79]. Other authors review CSR reporting quality improvement in selected countries (including EU members and Poland) [13,15,98,99]. However, in Poland, only Szczepankiewicz and Mućko [15] evaluated the CSRR and IR quality of energy and mining companies.

Good company financial performance and stability are very important for Polish SD. We wanted to analyse the 2009–2020 Polish energy company CSRRs and IRs. However, we have not found any studies addressing Polish energy company risk disclosures and are thus unable to offer a broad discussion concerning socially responsible reporting questions and risk disclosures. Therefore, only some references to selected international and Polish studies are possible. A large gap in the literature exists, which we want to fill. Therefore, the fundamental question should be: whether and what risk information should appear in CSRRs and IRs to ensure that such disclosures are useful to Stakeholders?

We conclude that the non-financial reports (CSRRs and IRs) must address the information needs of many Stakeholders (eight key groups and 32 categories—see Table 3). Socially responsible energy companies should provide a suitable quantity and usefulness of disclosed risk information and standardise the scope, structure, and form of annual CSRRs and IRs to ensure comparability, e.g., [13,16,58,59,68,70,98,100,101].

Many studies of annual non-financial reports (e.g., CSRRs and IRs) show that these reports should be widely available, uncomplicated, understandable, and transparent. These reports are then most useful to Stakeholders. We consider that socially responsible energy company CSRRs and IRs additionally should comply with GRI 4 and applicable regulations, and be complete, logical, and cohesive, e.g., [59,98,99]. Therefore, socially responsible energy companies should provide transparent, cohesive, and logical presentations to Stakeholders. Annual IR page counts should also be reasonable, e.g., [11,15,66]. We conclude that IRs (see, e.g., TPE, G-S, PGEG) are more useful for Stakeholders than CSRRs (see, e.g., PGNiGG, FPHP, VEP, EDFP), as they present varied current company image aspects e.g., [11,57,59,101].

Our study of Polish energy company CSRRs and IRs shows that Stakeholders encounter significant difficulties in conducting a benchmark analysis. Reports differ in length (the smallest report has 43 pages, the largest 523 pages), and in the type and scope of information. Moreover, information is very often presented in two separate IR parts. It is thus difficult to analyse the relationship between Polish IR information providers. Currently, in Poland, no self-standards or guidelines show how to integrate IR information. These differences make it difficult for Stakeholders to compare current financial situations, risk management system effectiveness, and future results, because publishing CSR and SD information is voluntary in Poland.

Moreover, we believe that energy companies present only information about newly implemented quality systems, anti-corruption practices, adherence to ethical codes or principles, investment projects, good financial results, successes, awards, and other trust- and image-building facts, all of which are marshalled to demonstrate that the company is a CSR leader. CSRRs and IRs should only not be positive image building tools. Such an overemphasised and overoptimistic annual report image may undermine company credibility and the credibility of the dialogue between the reporting entity and its Stakeholders. We believe that companies publishing poor-quality CSRRs will feel pressure from Stakeholders to improve annual report quality, e.g., [11,66].

An open question needs asking: how can this situation be changed?

In Section 5.4 we propose a new model of socially responsible energy company risk disclosures for presenting CSRRs or IRs. This universal model can be implemented elsewhere.

5.4. A Model of Risk Information Disclosures in CSRRs and IRs and of Classifying Management Risks, Business Activity Risks, and SD

We conclude that the most important various threats and business activity risks (over 86.67%) are: (1) financial risk; (2) rising raw material prices for energy production and an increase in import costs; (3) the sharp cost increases for external subcontracting services; (4) rapid declines in energy investment pace; and (5) atmospheric pollution.

Detailed analysis of WSE-listed energy company board activity reports (see Table 4) shows that the types and categories of risk are far greater than indicated above. Reports of the WSE-listed energy companies show particular risk types relevant for future operations. Each risk type may give rise to legal, financial, or image-related consequences and impact the company’s business continuity. Therefore, we developed a risk disclosure model for energy company reporting that includes the basic types of business activity risks and SD. This model is a proposal to energy companies publishing annual CSRRs or IRs on their websites.

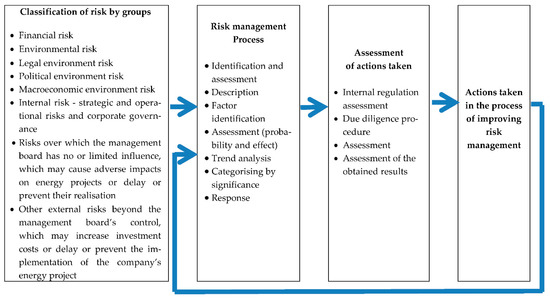

Figure 1 shows our concept of risk management systems and the model of categorising the type of risks that affect energy company business activity and SD. This concept of risk management systems is universal and can be implemented elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Risk information disclosures in socially responsible energy company reports—a model of classifying management risks, business activity risks, and SD. Source: own research.

We propose a model for disclosing risks in annual reports for the remaining energy companies that only publish CSRRs or IRs. One author considers that five of eight companies had the most complete board activity reports. The reports of these companies (PGNiGG, PGEG, TPE, ENEA, and Polenergia) show a fair image of risk impacts of continued business. This model can be a template for annual report risk disclosure. Transparent, exact, and reliable risk information is very important to Stakeholders.

Our risk classification by groups (Table 7) shows the type of risks that should be published in CSRRs and IRs when all Stakeholders do not have free access to current and complete information from energy company annual financial statements and board activity reports.

Table 7.

Risk classification in energy company annual non-financial reports.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

For many Stakeholders, although many technological changes in corporate information processing and reporting have occurred, the decision-making process is still difficult. IRs are the new means of reporting all financial and various supplementary non-financial information in annual statements. In many countries, IRs have not yet become standard practice but are very often individually adopted by many global companies to build investor relations. Polish IRs tend to contain many duplications and various discrepancies. Much IR information overlaps with that in separately published board activity reports [102,103,104]. Therefore, many global authors propose clarifying the concept of integrated reporting and reporting models, so that there is no information duplication e.g., [58,92,104].

The study aims to contribute to the evaluation of annual reporting, to determine whether Polish energy companies disclose risk in CSRRs or IRs, and if it is possible to assess threats, business activity risks, and SD. Our paper fills a gap in reporting and risk disclosures in energy company annual reports. We developed responses to the four research questions asked through an examination of the report quality of Polish energy companies.

In this study, we demonstrated a reasoning process using a literature review, empirical research, and the proposition of our model for disclosures of threats, business activity risks, and SD in annual reports (CSRRs or IRs). Methodologically, we used reporting processes tracing the historical evolution of Polish energy company CSRRs and IRs and risk disclosures [105].

We formulated our ten conclusions from the analysis of 2020 energy company annual reports: (1) all companies have already implemented CSR concepts; (2) all companies have already implemented environmental management systems; (3) 93% of companies have already implemented quality management systems; (4) 87% of companies have already implemented ethics management systems; (5) 75% of companies for 2020 have similar forms and structures of CSRRs and IRs, but a more in-depth study reveals multiple approaches to annual non-financial report contents and forms, and specifically disclosure of risk information; (6) over 60% of companies have already implemented ERM; (7) only 63% of companies disclose their non-financial threats in annual reports; (8) only 41% of companies disclose their financial threats in annual reports; (9) only 60% of reports from 2016 to 2020 were verified externally; and (10) interestingly, the quality of annual reporting has evolved positively over time (e.g., TPE reports 2010–2020).

We reached three key empirical findings:

- (1)

- Energy companies are at different stages in adopting integrated reporting.

- (2)

- Companies prefer not to disclose financial condition indicators and risk in Polish CSRRs and IRs.

- (3)

- The currently ‘soft’ solutions in the regulations give companies considerable freedom in disclosing non-financial information (including risk), which is at times counterproductive. Therefore, we should develop a single integrated standard for risk disclosures.

We propose a new model of classifying risks by type and risk management system. These various risks influence the continued energy company business activity. This universal model can be implemented elsewhere.

Many studies (see [17,18,19,103]) show that Stakeholders seek comprehensive information extending beyond CSR and including facts on companies’ financial performance and business activity risks. Therefore, external verification of such energy company reports is essential, and its results are important for Stakeholders.

6.2. Research Limits and Directions for Future Research

The article has several limitations. We conducted the study of risk information disclosures based on only one strategic sector in Poland and thus are unable to offer a wider perspective, because we did not find studies that have analysed energy company risk disclosure in annual CSRRs and IRs or from other sectors (although we reviewed many international studies, e.g., [106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113] and others).

Another limitation stems from the number of analysed reports (56 CSRRs and IRs) and the method employed to analyse them (content analysis method and use of a five-degree scale). Despite the undoubted advantages of the content analysis method and its suitability for small sample analysis (this method is used by many scientists to study companies’ reporting, because it can be easily replicated), this method has weaknesses, such as its unidirectionality or inability to create predictive models. Therefore, all results should be treated with due caution and as an incentive for further research on larger samples in many sectors.

Furthermore, political, social, and cultural factors influence the social responsibility disclosure agenda. We find crucial differences between the determinants of CSR disclosure in EU countries, including in CEE and developing countries. In developed countries, the concerns of specific Stakeholders are important in disclosing CSR information. In contrast, firms in CEE and developing countries perceive relatively little pressure from the public concerning CSR disclosure; see [55]. Therefore, further research in CEE and developing countries is necessary.

Despite many limitations, the applied research method and findings obtained allowed achieving the research aim, i.e., to develop a risk information disclosure model in non-financial reports of socially responsible Polish energy companies. This universal model can be implemented elsewhere.

We hope that this paper and model will provide a basis for future research in the energy and other strategic sectors. Continued research will allow for an improved understanding of Stakeholder expectations and an expected change in CSRR and IR scope and quality. A future comparative study may yield interesting results and lead to conclusions about regulatory changes (new EU directives, taxonomy, SD, green energy, standards, reporting, etc.). We also suggest a wider cross-industry investigation for future researchers.

Polish energy companies face the challenge of moving towards sustainable development and ecology based on CSR and SD concepts, and stable, efficient Polish and European energy systems. Meeting sustainable objectives requires substantial commitments from EU and national entities. The priority of sustainable development and ecology should be constantly emphasised, and the processes of CSR and non-financial reporting transformation should be empowered and monitored as a key factor for sustainable energy sector transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.I.S., W.E.L. and F.U.; methodology, E.I.S. and F.U.; software, E.I.S.; validation, E.I.S., W.E.L. and F.U.; formal analysis., E.I.S. and F.U.; investigation, E.I.S. and F.U.; resources E.I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.I.S.; writing—review and editing, E.I.S., W.E.L. and F.U.; visualization, E.I.S.; supervision, E.I.S., W.E.L. and F.U.; project administration, E.I.S.; funding acquisition, E.I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Financial data published on energy companies on corporate websites.

Table A1.

Financial data published on energy companies on corporate websites.

| Company Name | Reported Year | Basic Financial Indicators | Financial Statement (All Components) | Board Activity Report | Report of a Chartered Accountant (External Auditor) | Leader in 2008–2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGNiGG | 2005–2007 | - | - | - | - | |

| 2008 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 | |

| 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| FPHP | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| G-S | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 | |

| 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2019 | - | - | - | - | ||

| RWEP | 2009 | - | - | - | - | |

| 2010 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2012 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2013 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2014 | - | - | - | - | ||

| PLNG | 2014 | - | - | - | - | |

| EDFP | 2013 | - | - | - | - | |

| 2014–2015 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2016 | - | - | - | - | ||

| ZPUE | 2017 | - | - | - | - | |

| GPECG | 2016 | - | - | - | - | |

| TPE | 2011 | - | - | - | - | |

| 2012 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2013 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | |

| 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Polenergia | 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | |

| 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| VEP | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| ENEA | 2007–2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 2011 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2013 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2014 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2015 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2016 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2017 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2018 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2019 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2020 | - | - | - | - | ||

| PGEG | 2013–2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 | |

| 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| EnergaG | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 |

| 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| PKPE | 2020 | - | - | - | - |

References

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. Using global reporting initiative indicators for CSR programs. J. Glob. Responsib. 2013, 4, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Paper: Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; Available online: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_DOC-01-9_en.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- A Renewed EU Strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52011DC0681 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Freeman, E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG Integrated Reporting: Performance Insight through Better Business Reporting; KPMG: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. Available online: https://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/road-to-integrated-reporting.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Hoffman, C.; Fieseler, C. Investor relations beyond financials. Non-financial factors and capital market image building. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2011, 17, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Y. Sustainable development of a company: Building of new level relationship with the consumers of XXI Century. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2013, 15, 687–701. Available online: https://www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro/temp/Article_1234.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Carini, C.; Chiaf, E. The relationship between annual and sustainability, environmental and social reports. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2015, 13, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Freeman, E.; Abreu, M.C.S.D. Stakeholder theory as an ethical approach to effective management: Applying the theory to multiple contexts. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Definiowanie zakresu, zasięgu i jakości zintegrowanego sprawozdania. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2013, 174–186. Available online: http://www.dbc.wroc.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=28092&from=publication (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Informacje tworzące wartość rynkową w raportowaniu biznesowym. Kwart. Nauk O Przedsiębiorstwie 2013, 3, 33–42. Available online: https://polona.pl/item/informacje-tworzace-wartosc-rynkowa-w-raportowaniu-biznesowym,NDgzMzY3NDk/0/#item (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Hąbek, P. Evaluation of sustainability reporting practices in Poland. Qual. Quant. 2014, 48, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasodomska, J. CSR disclosures in the banking industry. Empirical evidence from Poland. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I.; Mućko, P. CSR reporting practices of Polish energy and mining companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch, J.; Krasodomska, J. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An empirical study of polish listed companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Ryzyka ujawniane w zintegrowanym sprawozdaniu przedsiębiorstwa społecznie odpowiedzialnego. Ekon. I Organ. Przedsiębiorstwa 2013, 5, 71–82. Available online: http://www.orgmasz.nazwa.pl/sklep/sklep/ekonomika-i-organizacja-przedsiebiorstwa/rocznik-2013/ekonomika-i-organizacja-przedsiebiorstw-nr-05-2013-r-detail.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Propozycja identyfikacji i klasyfikacji zagrożeń w ocenie zasadności przyjęcia założenia o kontynuacji działalności w jednostkach. Zesz. Teor. Rachun. 2013, 73, 113–130. Available online: http://bazekon.icm.edu.pl/bazekon/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171275207?printView=true (accessed on 10 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Przyjęcie założenia o kontynuacji działalności jednostki według krajowych i międzynarodowych regulacji. Stud. Oecon. Posnan. 2013, 8, 57–65. Available online: http://soep.ue.poznan.pl/jdownloads/Wszystkie%20numery/Rok%202013/05_szczepankiewicz.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Gabbi, G.; Giammarino, M.; Matthias, M. Die hard: Probability of default and soft information. Risks 2020, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Mazouz, K. Excess cash, trading continuity, and liquidity risk. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohv, K.; Lukason, O. What best predicts corporate bank loan defaults? An analysis of three different variable domains. Risks 2021, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, S.K.; Ramudu, J. Bankruptcy prediction and stress quantification using support vector machine: Evidence from indian banks. Risks 2020, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, E.; Ferrary, M. Dynamics of stakeholders’ implications in the institutionalization of the CSR field in France and in the United States. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Xu, S.; Gong, X. On the value of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An empirical investigation of corporate bond issues in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 227–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Hill, T.R. An exploratory analysis of stakeholders’ expectations and perceptions of corporate social and environmental reporting in South Africa. South Afr. J. Account. Res. 2010, 24, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Kim, H.; Park, K. Corporate environmental responsibility and firm performance in the financial services sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Ghauri, P. Determinants influencing CSR practices in small and medium sized MNE subsidiaries: A stakeholder perspective. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufflet, E.; Cruz, L.B.; Bres, L. An assessment of corporate social responsibility practices in the mining and oil and gas industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifka, M.S. Corporate responsibility reporting and its determinants in comparative perspective—A review of the empirical literature and a meta-analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.M.; Nazari, J.A.; Mahmoudian, F. Stakeholder relationships, engagement, and sustainability reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, L.; Zorio-Grima, A.; García-Benau, M.A. Stakeholder engagement, corporate social responsibility and integrated reporting: An exploratory study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, L.C.; Searcy, C. An analysis of indicators disclosed in corporate sustainability reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.B.; Watson, L. Corporate social responsibility research in accounting. J. Account. Lit. 2015, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL Ani, M.K. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and financial reporting quality: Evidence from Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2021, 21, S25–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souabni, S. Predicting an Uncertain Future: Narrative Reporting and Risk Information; The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miihkinen, A. What drives quality of firm risk disclosure? The impact of a national disclosure standard and reporting incentives under IFRS. Int. J. Account. 2012, 47, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, S.; Bozzolan, S. Framework for the analysis of firm risk communication. Int. J. Account. 2004, 39, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo, D.; Beltran, J.M.T. The disclosure of risk in financial statements. J. Account. Forum 2003, 28, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demina, I.; Dombrovskaya, E. Generating risk-based financial reporting. In Digital Science; Antipova, T., Rocha, Á., Eds.; online; 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/search.Search.html?type=publication&query=Generating%20risk-based%20financial%20reporting.%20In%20Digital%20Science.%20Edited%20by%20T.%20Antipova%20and%20%C3%81.%20Rocha (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Linsley, P.; Shrives, P. Risk Reporting: A Study of Risk Disclosures in the Annual Reports of UK Companies. Br. Account. Rev. 2006, 38, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzear, R.; Hussainey, K. Risk disclosure practice in Saudi non-financial listed companies. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2017, 14, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajili, K.; Zeghal, D.A. content analysis of risk management disclosures in Canadian annual reports. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2005, 22, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Bin, A.M.R.; Che Haat, M.H. Risk reporting—An exploratory study on risk management disclosure in Malaysian annual reports. Manag. Audit. J. 2008, 24, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, F. Are risk disclosures an effective tool to increase firm value? Manag. Decis. Econ. 2017, 38, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlif, H.; Hussainey, K. The association between risk disclosure and firm characteristics: A meta-analysis. J. Risk Res. 2014, 19, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, G.; Cagle, M.N.; Dalkılıç, A.F. Corporate social responsibility and regulatory initiatives in Turkey: Good implementation examples. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 15, 372–400. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309566265_Introduction_to_the_Special_issue_on_Corporate_Social_Reporting_in_Central_and_Eastern_Europe (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Albu, N.; Albu, C.N.; Filip, A. Corporate reporting in Central and Eastern Europe: Issues, challenges and research opportunities. Account. Eur. 2017, 14, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, P.; Pütter, J.; Dagilienè, L.; Dimante, D.; Haldma, T.; Kochalski, C.; Král, B.; Labaš, D.; Lääts, K.; Bedenik, N.O.; et al. Status Quo and future development of sustainability reporting in Central and Eastern Europe. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2017, 22, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, C.N.; Klimczak, K.M. Editorial. Small and Medium-sized Entities Reporting in Central and Eastern Europe. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 16, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijałkowska, J.; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Garsztka, P. Corporate social-environmental performance versus financial performance of banks in Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Arraiano, I.; Hategan, C.D. The Stage of Corporate Social Responsibility in EU-CEE Countries. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouhal, J.; Gurvits, N.; Nikitina-Kalamäe, M.; Startseva, E. Finding the link between CSR reporting and corporate financial performance: Evidence on Czech and Estonian listed companies. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2015, 4, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, P. Rewolucja w Raportowaniu Biznesowym. Interesariusze, Konkurencyjność, Społeczna Odpowiedzialność; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Samelak, J. Zintegrowane Sprawozdanie Przedsiębiorstwa Społecznie Odpowiedzialnego; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Szadziewska, A. Environmental reporting by large companies in Poland. Zesz. Teor. Rachun. 2012, 68, 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Krasodomska, J. Informacje niefinansowe jako element rocznego raportu spółki. Zesz. Nauk./Uniw. Ekon. W Krakowie 2010, 816, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Karmańska, A. (Ed.) Ryzyko w Rachunkowości; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wysłocka, E. Rola informacji i sprawozdawczości finansowej w ocenie ryzyka inwestycyjnego. Finans. Rynk. Finans. Ubezpieczenia 2013, 61, 605–614. Available online: https://www.wneiz.pl/nauka_wneiz/frfu/61-2013/FRFU-61-t2-605.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Sierpińska, M.; Jachna, T. Ocena Przedsiębiorstwa Według Standardów Światowych; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, E. Analiza Sprawozdań Finansowych; PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dunal, P.; Furman, W.; Gajda, G.; Kolenda, D.; Król, M. Ryzyko we Współczesnej Rachunkowości; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, J.; Archel, P.; Correa, C. GRI and the camouflaging of corporate unsustainability. Account. Forum 2006, 30, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.-M.; Yeo, J. Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. 2013. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/g4/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Soyka, P. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) Integrated Reporting Framework: Toward better sustainability reporting and (way) beyond. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2013, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2013/34/EU. 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pl/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32013L0034 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Directive 2014/95/EU. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Commission Recommendation 2014/208/EU of 9 April 2014 on the Quality of Corporate Governance Reporting (‘Comply or Explain’). 2014. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2014/208/oj (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- The Accounting Act. Poland. 2021. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19941210591/U/D19940591Lj.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- National Accounting Standard 9, Krajowy Standard Rachunkowości nr 9 “Sprawozdanie z Działalności”. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/krajowe-standardy-rachunkowosci (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Polish Non-Financial Reporting Standard (SIN). 2017. Available online: https://odpowiedzialnybiznes.pl/publikacje/standard-informacji-niefinansowych-sin-2017/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Management Commentary jako nowe źródło informacji o działalności jednostki gospodarczej. Zesz. Teor. Rachun. 2012, 66, 191–203. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=138241 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2010, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofian, I.; Dumitru, M. The Compliance of the Integrated Reports Issued by European Financial Companies with the International Integrated Reporting Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoszewicz, A.; Rutkowska-Ziarko, A. Practice of Non-Financial Reports Assurance Services in the Polish Audit Market—The Range, Limits and Prospects for the Future. Risks 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Searcy, C.; dos Santos, P.; Kensah, D. A Review of Dutch Corporate Sustainable Development Reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkey, R.N.; Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M.; Sankara, J. Does assurance on CSR reporting enhance environmental reputation? An examination in the U.S. context. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.R.; Simnett, R. CSR and assurance services: A research agenda. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, M.; Lobo, L.G.J.; Mazzi, F.; Paugam, L. Implications of the Joint Provision of CSR Assurance and Financial Audit for Auditors’ Assessment of Going-Concern Risk. Contemp. Account. Res. 2020, 37, 1248–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, G.; Becatti, L. Assurance services for sustainability reports: Standards and empirical evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petryk, O.; Kurylo, O.; Karmaza, O.; Makhinchuk, V.; Martyniuk, O. Non-financial reporting of companies and the necessity of its confirmation by auditors in Ukraine. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pucheta, M.; Consuelo, M.; Bel-Oms, I.; Rodrigues, L.L. The engagement of auditors in the reporting of corporate social responsibility information. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, E.R.; van Eck, L. Research on extended external reporting assurance: Trends, themes and opportunities. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2021, 32, 63–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, C.; Tenwick, J.; Bicciolo, G. Comparing the Implementation of the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive in the UK, Germany, France and Italy; Frank Bold: Kraków, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N.; Rubino, M. Appreciations, criticisms, determinants, and effects of integrated reporting: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romolini, A.; Fissi, S.; Gori, E. Exploring integrated reporting research: Results and perspectives. Int. J. Account. Financ. Report. 2017, 7, 32–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, J. Disclosure of Non-Financial Information: A Powerful Corporate Governance. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Stolowy, H.; Paugam, L. The expansion of non-financial reporting: An exploratory study. Account. Bus. Res. 2018, 48, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allini, A.; Rossi, F.M.; Hussainey, K. The boards’ role in risk disclosure: An exploratory study of Italian listed state-owned companies, J. Public Money Manag. 2016, 36, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahat, Y.; Dunne, T.; Fifield, S.; Power, D. Risk-related disclosure: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. J. Account. Forum 2019, 43, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, B. The deteriorating usefulness of financial report information and how to reverse it. Account. Bus. Res. 2018, 48, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S. Risk reporting quality: Implications of academic research for financial reporting policy. J. Account. Bus. Res. 2012, 42, 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hąbek, P.; Wolniak, R. Assessing the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of reporting practices in selected European Union member states. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Ewolucja sprawozdawczości przedsiębiorstw—Problemy zapewnienia porównywalności zintegrowanych raportów z zakresu zrównoważonego rozwoju i CSR. Finans. Rynk. Finansowe. Ubezpieczenia 2014, 71, 135–148. Available online: http://www.wneiz.pl/nauka_wneiz/frfu/71-2014/FRFU-71-135.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Kowalczyk, R. How do stakeholder pressure influence on CSR-Practices in Poland? The construction industry case. J. EU Res. Bus. 2019, 2019, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braviera-Puig, A.; Gómez-Navarro, T.; García-Melón, M.; García-Martínez, G. Assessing the communication quality of CSR reports. A case study on four spanish food companies. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11010–11031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulinajtis-Grzybek, M.; Świderska, G. Practical use of the integrated reporting framework—An analysis of the content of integrated reports of selected companies. Zesz. Teor. Rachun. 2017, 94, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I. Zintegrowane sprawozdanie przedsiębiorstwa jako narzędzie komunikacji z interesariuszami. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2014, 329, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]