Abstract

The current EU energy policy aims to diversify energy sources to ensure energy security while decarbonising the economy and promoting low carbon and clean energy technologies. These tasks are carried out under the European Green Deal Program. Therefore, the overriding goal at present is to search for new sources of energy, including energy recovery from waste. In EU countries, the legal system for waste management is adapted to the circular economy. In Poland, due to the legal possibility of temporary storage and disposal of waste, a substantial volume of industrial waste is temporarily stored and landfilled (above 40%), compared to the importance of waste subjected to treatment. Moreover, energy recovery from waste accounts for a negligible share (below 5%). It may be due to the high costs of these processes, stringent emissions and environmental quality standards. Therefore, as in certain EU countries, the problem of landfill site arson attacks has been exacerbated in Poland (177 fires in 2019). The aim of this article is to determine the relationship between the application of the existing regulations concerning closed-loop waste management and the effectiveness of methods, ways and economic instruments preventing the illegal burning of landfill waste in Poland under the current EU energy policy. Therefore, it can be assumed that this system is not complete. Based on factor force analysis at a scale 1–5, it was found that technological (3.4), legal (3.16) and economic (3.0) factors have the greatest impact on this system. The waste management system should be oriented towards increased waste recovery and a more significant reduction in the volume of temporarily stored waste and landfill waste. It should be considered whether the current move away from the incineration of waste, according to the new EU energy policy, is a better solution in environmental and economic terms than incurring very high costs due to eliminating the effects of the incineration of landfill waste that causes environmental damage.

1. Introduction

As part of the EU energy policy referred to in Article 194, TFEU entitles each Member State to determine the conditions for the use of its energy resources, the choice between different energy sources and the overall structure of its energy supply [1]. In accordance with the provisions of the Energy Union of 2015, the most important goals of the EU energy policy were indicated, i.e., the diversification of European energy sources, ensuring an integrated internal energy market, improving energy efficiency, decarbonising the economy and transitioning to a low-carbon economy, as well as promoting research in the field of low-carbon technologies and clean energy technologies. One of the greatest challenges for the EU Member States is the lack of diversification of energy sources, which disturbs the security of energy supply. It is directly related to external actions taken by the EU in relation to the most important suppliers of energy resources [2,3]. Greenhouse gas emissions, according to the net-zero concept, should be neutralised across the scale [4]. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the continuous sustainable development of the energy sector by raising efficiency and safety standards, extending the availability of various energy sources, increasing competitiveness and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It is very important in this matter to strive for the greater diversification of energy sources. In the 2030 perspective, the EU supports the diversification of energy sources, but first of all, the EU focuses on climate-friendly resources [5]. These goals of the EU energy policy are implemented under the European Green Deal Program established in 2019 [6]. The main idea behind this program is to make Europe a climate-neutral continent by 2050 by delivering clean, affordable and secure energy. As part of this agenda, a new energy legislative package entitled “Fit for 55′: delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the way to climate neutrality” was established [7]. To achieve these energy goals, new sources of energy should be sought, including energy derived from waste.

Nowadays, the issue of waste management has become critical and relevant in terms of environmental protection. The global tendencies to counteract the increase in the mass of waste and the costs of their recovery and neutralisation are also visible in terms of changes in the strategy and the resulting legislative changes. For example, the European Commission’s reports indicate that current production methods and increased consumption contribute to global warming, pollution, material consumption and the depletion of natural resources [8]. For this reason, more attention is paid to the circular economy. The concept of a circular economy was introduced by David Pearce in 1990 [9], and it concerns the interrelationship of the four economic functions of the environment. The environment not only provides utility values—besides being a resource base and a source for economic activity, it is also a basic life support system [10]. The circular economy is defined as a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, energy emissions and leakage are minimised by slowing down, closing and narrowing material and energy loops [11,12]. The introduction of which is to result, i.e., in reducing the amount of waste generated, reusing products and closing production chains. This course of action is appropriate to achieve the environmental goals.

Currently, the transition to a circular economy is one of the policy priorities in Europe. This requires the strengthening of the three “pillars” of this system, such as environmental benefits, cost savings due to the limitation of natural resource needs and additional economic benefits from creating new markets [13]. It is necessary to implement the Action Plan for the circular economy in the European Union established in 2015 [14], which is divided into sections on pro-production, consumption, waste management and processing of secondary raw materials [15,16]. Achieving the EU’s goal of becoming a ‘circular economy’ needs the introduction of changes in the requirements contained in the Waste Framework Directive 2008/98/EC (WFD) [17] concerning the planning of such infrastructure systems. Circular economy should be closely related to the efficiency of resource productivity and effective waste management [18,19]. According to the principle of proximity, WFD involves establishing an integrated and appropriate waste management system at the national level (Art. 16). Furthermore, the system should be designed in such a manner to allow for the entire community to become self-sufficient in terms of waste disposal and recovery. The EU’s legal tool to support the transition to a circular economy is the so-called Waste Package, i.e., an amendment to six Directives concerning waste management [20]. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the implementation of this concept is determined by the applied legal, technical and organisational solutions in waste management, particularly regarding the ‘tightening up’ and ‘sealing’ of this system.

The lack of sealing of this system contributes to ineffective waste management, e.g., through its storage. It should be noted here that, according to the EU’s policy, waste storage should only be a temporary form of waste management before recovery or disposal. Waste landfilling is a method of last resort, applied only for non-recoverable waste under the provisions of Waste Framework Directive. This is because the Directive aims to remedy the shortcomings of the 1975 Waste Framework Directive [21] and its amendment and promotes measures to reduce waste landfilling [22]. As an EU Member State, Poland implemented the provisions of Directive 2008/98/EC to its legislation, first in the 2001 Act on Waste [23], and subsequently in the 2012 Act on Waste (AW) [24], which is currently in force.

Effective waste management in accordance with legal requirements is a great challenge due to technical and organisational possibilities. This applies in particular to industrial waste. In Europe, municipal waste only accounts for approximately 8% [25]. Poland generated almost 127 million tonnes of waste in 2019, of which municipal waste accounted for 10% (12.8 million tonnes). Since 2000, the volume of generated waste (excluding municipal waste) has ranged from 110 to 130 million tonnes. In 2019, it decreased slightly (1%) to the previous year and amounted to 114.1 million tonnes [26]. However, in the opinion of the authors, too much waste production and the inability to manage them result in illegal activities. Among these phenomena, intentionally setting fire to waste storage and landfill sites has been observed in recent years.

Recently, illegal landfilling and the incineration of waste have become reasonably widespread phenomena noted in EU countries, which has caused enormous losses in the environment, e.g., in Italy and Greece [27,28], Slovakia [29], England and Wales [30]. The scale of the landfill arson trend primarily concerns industrial waste, containing often toxic substances. There is hazardous waste, e.g., used car tyres, that is most often illegally burned. This generates emissions of highly toxic compounds to the atmosphere, e.g., dioxins, furans and aromatic hydrocarbons that cause lifestyle diseases and air, water and soil pollution [31,32]. Highly toxic dioxins are especially dangerous, including 2,3,7,8-tetraklhorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), which has recently been classified as carcinogenic in animals and humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). The presence of these substances has been reported in mammalian milk produced by domestic animals (sheep and cows) as well as in human milk samples [33]. During the illegal burning of toxic waste, the population living in these areas may be exposed to cancer, e.g., sarcomas, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [34]. Moreover, the hazardous waste incinerated is characterised by properties such as explosiveness, flammability, toxicity, mutagenicity and ecotoxicity. Introduced into the environment, these substances circulate in nature, causing the contamination of air, water, soil and food, and thus, the resources that are used by humans. There are persistent organic pollutants that are not biodegradable in the environment, i.e., cannot be decomposed to less harmful components or its degradation even by several hundred years [35]. Not only does it pose a threat to human health and lives, and the environment, but it also causes economic losses, i.e., a reduction in the number of resources of suitable quality used in economic activities. Hence, there is a need for a comprehensive analysis of the relevant legal solutions that would prevent this phenomenon at the EU and national regulations level.

Moreover, in the literature, there are many previously cited studies on the waste management system, both in legal, technical and organisational terms. The principles of the circular economy, which also apply to waste, are widely described. However, there is no indication of factors and reasons for the system’s failure to close, the consequence of which is, e.g., illegal waste incineration. This is very important due to not only the threats to the environment and people causing by such actions, but also the resulting economic losses. Identification of legal gaps, factors and other reasons for such a state is a novelty of this study and may be an indication of legislative and organisational changes aimed at limiting illegal methods of handling waste. In addition, an industrial waste management strategy will be proposed. This article assumes that the lack of an appropriate and stricter legal system for closed-loop waste management may contribute to illegally setting fire to industrial waste landfill sites in Poland. Therefore, answers to the following research questions were sought: Are the existing legal solutions and economic instruments and the methods used for closed-loop waste management sufficient to prevent the trend of illegal landfill waste burning? The aim of this study is to determine the relationship between the application of the existing regulations concerning closed-loop waste management and the effectiveness of methods, ways and economic instruments preventing the illegal burning of landfill waste in Poland under the current EU energy policy.

2. Materials and Methods

Table 1.

Details of the research methods used to analysis of the industrial waste management.

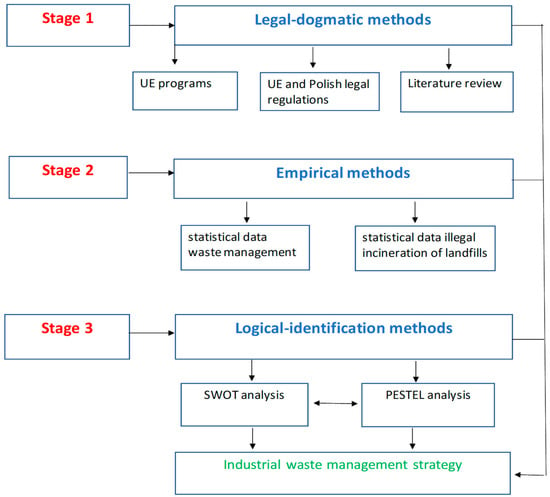

Figure 1.

Types of methods used to verify research assumptions.

- (1)

- The legal dogmatic method

The subjects of the analysis were legal regulations and documents in the field of UE energy policy, European Green Deal program, circular economy and waste management at the EU and national levels. For the purpose of the study, the following were examined: (1) Waste Directive 2008/98/EC, Directive 2000/76/EC, Council Directive 1999/31/EC, Directive (EU) 2018/850; (2) Regulation (EU) 2020/852; (3) European Commission Communications COM(2015) 614/2), COM/2017/34; (4) Polish legal acts—Waste Act of 2001, 2012, Environmental Protection Law of 2001, Environmental Protection Inspectorate Act of 1991, Act of 2018 amended, Environmental Damage Act of 2007, Criminal Code of 1997; (5) Polish Regulations in the range of waste management methods of 2013, 2015, 2016, 2020 and 2021; (6) Polish chosen jurisprudence. The literature in this area was also analysed.

- (2)

- Empirical methods

Empirical studies were based on the analysis of statistical data. The subject of the analysis was the efficiency of industrial waste management in Poland compared to the EU. For this purpose, the amounts of generated waste and the structure of its management in 2016–2020 after the establishment of the Circular Economy Action Plan in 2015, based on data compiled by Eurostat and the Central Statistical Office in Poland, were presented. Recycling (recovery) is considered the most effective method, and the least effective waste disposal and temporary storage. In this respect, the following were analysed: (1) waste generated, (2) recovered, (3) disposal, including landfilling, (4) temporarily stored, (5) transferred to other recipients and (6) previously waste stored (accumulated). On this basis, a trend in the structure of waste management in the analysed period was obtained. In addition, the scale of the phenomenon of the illegal incineration of landfills in the EU and Poland was analysed.

- (3)

- The logical identification method

Based on the analysis of legal regulations, the literature and statistical data, the industrial waste management system was assessed, indicating its advantages and disadvantages. For this purpose, the SWOT method was used to categorise factors into internal (strengths, weaknesses) and external (opportunities, threats) (Table 2) [36]. Thus, this analysis allows to compare the strengths and weaknesses of the industrial waste management system with the opportunities and threats from the environment. Strengths and weaknesses are internal and inherent in this system, while opportunities and threats are external and located in the environment of this system.

Table 2.

Scheme for SWOT analysis of the industrial waste management system [36].

The PESTEL method was used to identify the factors influencing industrial waste management. This analysis classifies political (P), economic (€), social (S), technological (T), environmental (E) and legal (L) factors [37]. Therefore, in this study, the following factors were analysed:

Political factors—government actions that have an impact on waste management (EU energy policy, European Green Deal, environmental law, circular economy strategy).

Economic factors—financial system of the industrial waste management (economic factors, financial abilities, financing).

Social factors—illegal waste management affect the population (ecological safety, health of people, state of environment)

Technological and organisational factors—technological methods and ways of waste management (technology of waste recovery and disposal, structure of waste management, the scale of the phenomenon of illegal waste incineration).

Environmental factors—includes the state of environmental resources, pollution of environment.

Legal factors—environmental law principles, hierarchy of waste management, waste recovery and disposal requirements, UE law implementation, tax and economy law, environmental crimes, economy and tax crimes, criminological activities.

The next stage of this analysis was an assessment of the impact force for these individual groups. A total of 27 factors were analysed, including 3 political, 5 economic, 5 technological, 1 social and environmental and 12 legal factors. The analysis adopted a scale from 1 to 5, where 1—small impact, 5—large impact. An industrial waste management strategy was described and proposed based on the evaluation of these factors.

The last stage of the analyses was determined the relationship between the application of the existing regulations concerning closed-loop waste management and the effectiveness of methods, ways and economic instruments preventing the illegal burning of landfill waste in Poland under the current EU energy policy.

3. Literature Review and Legal Regulation Analysis

3.1. UE Energy Policy and Programs and Waste Management Relations

One of the goals of the EU’s energy policy to be achieved in the 2030 perspective, as already mentioned, is the diversification of energy sources in the context of the sustainable development of the Member States. It is related to the concept of an energy mix, which is a mixture of different types of energy. Their diversity increases the security of the country in the event of a failure or exhaustion of one of the energy sources. Thus, the EU supports the diversification of energy sources, but prioritizes climate-friendly resources [38]. Sustainable development in energy policy refers to the search for instruments that ensure a balance between the objectives of environmental protection, competitiveness and security of supply. It is manifested in ensuring the continuous sustainable development of the energy sector by complying with efficiency and safety standards, extending the availability of various energy sources, increasing competitiveness and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [39]. Thus, the greater the variety of energy sources, the greater the chance of maintaining the country’s energy security. The EU policy in the first place focuses on the development of renewable energy sources, but also other energy sources, e.g., those generated from waste.

The objectives of the EU energy policy have also been included in the European Green Deal Program (EGD). All 27 Member States have committed to transforming the EU into the first climate neutral continent by 2050. To achieve this target, they have committed themselves to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 below 1990 levels. This program reviews energy and climate legislation with the aim of increasing emission reductions and enhancing renewable energy deployment and energy efficiency. Guidelines for environmental protection and aid in the search for energy sources were indicated. Under this program, the ‘Fit for 55′ Package, which includes initiatives in a number of closely related areas, e.g., climate, environment, energy, transport, industry, agriculture and sustainable finance, aims to transform the ambitions of the Green Deal into concrete legislation. It is a set of proposals to amend climate, energy and transport legislation and introduce new legislative initiatives to align EU legislation with the EU’s climate goals, including concerning alternative fuels also derived from waste [40,41]. Sectoral integration means connecting different energy carriers—electricity, heat, cooling, gas, solid and liquid fuels—with end-use sectors such as construction, transport and industry [42].

The European Green Deal assumes that by 2050, the EU economy will be climate neutral and resource efficient. To achieve this, it must become a circular economy, which constitutes its competitive advantage and resilience. An extremely important element of the energy transformation included in the EGD is the circular economy. The full implementation of the circular economy, including taking into account not only mass streams, but also energy flows throughout the life cycle and the issue of harmful emissions, causes the circular economy to be described as an environmentally sustainable economy (green economy). Circular economy systems keep the added value of products as long as possible and eliminate waste. They preserve resources within the economy when the life cycle of products closes, allowing them to be reused productively multiple times, thus, creating additional value. The EU’s understanding of the circular economy is reflected in the new waste hierarchy adopted by the European Commission in 2017 [43,44]. The priority of this hierarchy is to avoid or minimise the generation of waste, i.e., the waste of raw materials. The next solution is to reuse raw materials. The next step is recycling, because it uses more resources (e.g., energy) and it cannot be carried out indefinitely in a loop. Another type of recovery, e.g., energy, is on the penultimate place because only a small part of the raw material’s potential can be recovered in this way. The last solution that should be used as an absolute last resort is the disposal of waste/raw material. Only the first three methods are recommended in the circular economy: reduce, reuse and recycle (3 × R). Therefore, the waste hierarchy supports EU waste policy and legislation and is crucial for the transition to a circular economy. Its primary goal is to establish a priority order to minimise negative environmental effects and optimise efficient waste management in the prevention and management of waste. This Communication covers the following main waste-to-energy processes: (a) co-incineration of waste in combustion plants (e.g., power plants) and in the production of cement and lime; (b) incineration of waste in dedicated facilities; (c) anaerobic digestion of biodegradable waste; (e) production of solid, liquid or gaseous fuels from waste; and (f) other processes, including direct combustion after pyrolysis or gasification.

3.2. Legal System for Waste Management in the EU

The waste management rules at the EU level are set out in the Directive 2008/98/WE. Waste management means the overall handling of waste, namely the collection, transport, recovery, and disposal of waste, including the supervision of such operations and the after-care of disposal sites (Art. 3(9)). The main objective of the Directive is the handling of waste in such a manner so as to not harm the environment or human health, in line with the waste hierarchy and the “polluter pays” principle. Therefore, the main objective of the EU’s waste policy should be to reduce the adverse effects of waste generation and management on human health and the environment. Furthermore, in line with the circular economy principles, waste management policy should aim to reduce resource use by subjecting waste to recovery and using recovered materials to protect natural resources. Therefore, waste management should follow the waste hierarchy in the following order: prevention, preparing for re-use; recycling; other recovery methods (e.g., energy recovery); and disposal. The top priority in the waste management system is to prevent waste generation by taking measures before a substance, material or product has become waste, thus, reducing: (a) the quantity of waste, including through the re-use of products or the extension of the life span of products; (b) the adverse impacts of the generated waste on the environment and human health; or (c) the content of harmful substances in materials and products (Art. 3(12) of the WFD). A subsequent step is the recovery (material or organic recycling, i.e., composting). At the same time, disposal is the last resort method only applied for waste that is not recoverable and should be carried out in a manner safe for the environment and humans in line with regulations. The disposal methods include waste incineration and landfilling.

The most important waste disposal rules regulated in EU legislation are presented in Table 3. These regulations are contained in Directive 2000/76/EC on the incineration of waste [45], and Council Directive 1999/31/EC on the landfill of waste [46], amended by Directive (EU) 2018/850 [47]. According to the provisions of Directive 2000/76/EC, an issue worth emphasizing is to establish rigorous limit values for emissions from incineration plants based on the BATs [48,49]. BATs (Best Available Techniques) have been introduced into the EU legal system by the Council Directive 96/61/EC [50]. The legal definition of BATs is contained in Article 3(10) of the Act 2001 Environmental Protection Law [51] as the most effective and advanced level of technology development and methods of conducting a given activity, which indicates the possible use of particular techniques as the grounds for setting emission limit values and other permit conditions aimed at preventing or, failing that, reducing emissions, and the impact on the environment as a whole [52]. Waste incineration also involves the recovery of energy from waste. It should be emphasized that Directive 2008/98/EC in ANNEX II provides for the recovery process use of waste as a fuel or other means of generating energy (R1). This process shall include incineration plants intended solely for the treatment of municipal solid waste, provided that their energy efficiency is equal to or greater than 0.60 for operating installations authorised in accordance with the applicable Community legislation in force before 1 January 2009; or 0.65 for installations authorised after 31 December 2008. Here, the RDFs (Refuse-Derived Fuels) are defined in the 2003 European Commission document entitled “Refuse Derived Fuel current practice and perspectives” [53] as fuels including various types of waste that have been processed to meet industry guidelines, regulations or specifications, mainly with the aim of achieving a high calorific value. RDFs are also sourced from industrial waste. A wide range of industrial wastes are used as replacement or secondary fuels in Europe [54,55]. These wastes include plastic and paper, used tyres, biomass waste, textile waste, car dismantling residue operations and hazardous industrial waste of high calorific value, e.g., waste oils, industrial sludge [53,56]. Refuse-Derived Fuel is an alternative fuel which is obtained from solid waste. It is a renewable form of energy that can replace coal. By replacing this, we are able to eliminate problems such as ash handling, flue gas emission and air pollution, which are associated with fossil fuels [57].

Table 3.

Basic principles of waste disposal according to EU law.

The Directive 1999/31/EC encourages the prevention, recycling and recovery of waste through reducing the quantity and quality control of waste sent to final storage in landfills. The main goal of the Directive is eliminating uncontrolled landfills [58]. Moreover, the EU Commission recommended inspectors to carry out checks on landfills and the monitoring system [59,60]. However, the Directive 2018/850 recommends the transition of waste management to a circular economy. According to the EU Commission’s guidelines, waste-to-energy processes may have a role in the transition to a circular economy, provided that the EU’s waste hierarchy is applied as a leading principle, and selected waste treatment technologies should ensure that higher levels of waste prevention, re-use and recycling are achieved. This is essential to provide the full potential of a circular economy, in both environmental and economic terms, and to reinforce European leadership in green technologies. It should also be noted that the waste-to-energy conversion can maximise the circular economy’s contribution and reduce CO2 emissions only when the waste hierarchy is followed, which is in line with the EU’s energy strategy [61]. Therefore, the circular economy is a model of production and consumption that in-volves sharing, lending, reusing, repairing, reconditioning and recycling existing materials and products for as long as possible. In this way, the life span of products is extended. In practice, it translates into reducing waste to a minimum. When a product’s life comes to an end, the raw materials and waste derived from it should remain in the economy and be reused, thus, creating an additional value [43].

3.3. Waste Management in Poland and the Acceptable Waste Disposal Methods

Waste management in Poland is carried out under the EU rules that were implemented into the 2012 Act on Waste (AW), i.e., the principle of sustainable development, comprehensiveness, prevention of waste generation, prevention, precaution, proximity in waste management, waste elimination “at source,” separate waste collection, non-deterioration of waste quality, safe operation of installations and equipment in waste management, the obligation to subject waste to recovery or disposal only in installations or facilities that meet specific requirements, protection of human health and lives, compliance with environmental protection requirements and following the waste hierarchy [24]. Among these, the principle of proximity is quite important, where the waste is first processed at the place where it is generated, which may reduce the negative impact on the environment during transport and, consequently, reduce the costs of their disposal [62]. The literature considers that these principles fulfil two essential functions: (1) a function to organise the legal system for waste management, and (2) an environmental protection function. Therefore, the waste management principles achieve the following objectives:

- A maximum reduction in the volume of waste in all economic activities and human livelihood;

- The immediate integration of production residues back into production;

- Recovery of raw materials from collected waste;

- The application of waste disposal processes;

- Waste landfilling in an ordered manner while ensuring a minimum impact on the environment [63].

The content of these principles determines the correct handling of waste, both theoretically and practically [64]. The system is based on waste treatment, which involves the waste recovery and disposal (Art. 3(21) of the AW). These processes are often preceded by waste temporary storage, which the Polish legislator broadly covers. According to Article 3(5), storage involves temporary waste maintenance as well as (a) the initial storage of waste by the waste generator, (b) the temporary storage of waste by the waste collector, and (c) the storage of waste by the waste treatment operator. Therefore, waste storage can be considered a temporary step that precedes the recovery or disposal of waste. The most commonly used and legally permitted waste disposal methods include thermal treatment (incineration) and landfilling (Annex 2 of the AW). The thermal treatment of waste involves incineration by oxidation or other waste thermal treatment processes, including pyrolysis, gasification and plasma processes, provided that the substances generated during these processes are subsequently incinerated (Art. 3(29) of the AW). This process should be carried out in waste incineration plants that meet the technical requirements and emission and environmental quality standards. These are plants or parts dedicated to the thermal treatment of waste with or without the recovery of generated heat. Incineration plants include installations and equipment designed to carry out thermal treatment of waste, including the purification of exhaust gases and their introduction to the air, process control, steering, monitoring, installations for the reception, pre-treatment, storage of waste delivered for thermal treatment, and installations for the storage and treatment of substances resulting from the incineration and exhaust gas purification (Art. 3(26) of the AW) [65]. In Poland, as in other Member States, RDFs are also used. This is important due to the fact that from January 1, 2016, they are forbidden from landfill waste with a calorific value exceeding 6 MJ/kg, which should encourage a wider use of waste for energy purposes [66,67]. However, waste storage should only occur at landfills, i.e., facilities specifically designated for this purpose (Art. 3(25) of the AW) [40,68]. The detailed requirements for waste management methods are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Detailed requirements for the waste management methods in Polish law.

3.4. Economic and Legal Problems of Waste Management

When analysing the state of industrial waste management, apart from legal problems, economic limitations were also observed. Nevertheless, in the EU, through the implementation of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment [75], the taxonomy of energy obtained in the incineration of waste was changed to non-ecological activities. This Regulation aims to increase the level of protection of the environment by redirecting capital from environmentally harmful investments to more environmentally friendly ones. Thus, the taxonomy does not prohibit investing in ecologically destructive activities but grants additional preferences to green solutions. Furthermore, this Regulation establishes criteria for determining whether an economic activity qualifies as environmentally sustainable. Such an investment should meet the environmental objectives set out in Article 9, i.e., contribute to climate change mitigation, transition to a circular economy or prevent environmental pollution. As part of the implementation of the circular economy, the incineration of waste should be minimised and its disposal, including landfilling, should be avoided, in line with the principles of the waste hierarchy (Art. 13 of the AW). However, in practice, there are cases where EU funds are still used to build a thermal waste treatment plant, e.g., to solve the waste problem in a municipality, despite other EU guidelines. This is especially visible to investments that started before 2020, i.e., the amendment of the above Regulation. Unfortunately, although these investments have continued to be subsidized, they will not be treated as sustainable investments, which may affect the costs of their functioning in the future, e.g., by not using support systems for “green” or “sustainable” production. As a rule, one must agree with the direction of such activities. However, it is worth noting that foreign investors, especially, may demand the protection of their legitimate interest in light of international agreements [76].

The financial limitation is also the high costs of adapting the installation to the stringent requirements [77]. Another issue is obtaining revenues from the vacated sites after the accumulated and incinerated waste. Another problem is the lack of financing for a thermal waste treatment plant, which is not conducive to reducing the mass of landfill waste. The lack of proper control and supervision is conducive to illegal activities, which poses numerous threats to the waste management system. The consequence of such a state is the search for alternative ways to manage landfill waste, such as illegal waste incineration, which negatively affects human health and the state of the environment. It also causes tax crimes. It takes advantage of the lack of, in principle, the liability of the partners of a capital company for its obligations. In this arrangement, civil liability applies to members of the company’s governing bodies. In a situation where these people do not have property or meet the exclusion criteria on time (e.g., they file a petition for bankruptcy of the entity), they will be exempt from civil liability. In Polish company law, there is no institution of “shadow directors,” analogous to the provisions of English law. Therefore, premises of extraction occur not only in the case of civil liability of members of the management board but also in public liability to administrative penalties for the violation of environmental protection regulations. In this case, state authorities may also face obstacles to compulsory enforcement. Additionally, even if the lack of members of the company’s governing bodies effectively fails to raise charges of exclusion, if they do not have property, it will not be possible to enforce administrative penalties. Consequently, the imposed administrative penalties or civil liability have no impact on the effectiveness of legal measures to prevent violations of environmental regulations. In such a case, it should seek protection in criminal regulations; in this respect, one should look for a possible fraud, the features of which are the broadest and used in the fight against VAT fraud (VAT carousels) [78,79,80,81,82]. The other method of the illegal disposal of waste is to conduct such activity by subletting the premises of a company registered on the so-called “Pole.” A common practice is to report such a company for a short period when a significant accumulation of waste suddenly disappears, leaving the commune areas with a large mass of accumulated waste, often hazardous [83].

3.5. Legislative Action to Prevent Arson Attacks on Landfill Waste in Poland

To prevent the trend of setting fire to landfill sites, an attempt was made to “tighten” the waste management system in Poland by amending the 2012 Act on Waste and the 1991 Act on the Environmental Protection Inspectorate [84] in the 2018 Act [85]. This amendment introduced more stringent regulations for the different waste management stages (Table 5).

Table 5.

Legislative solutions to prevent illegal incinerated waste.

Having analysed the above regulations included in Table 5, it is worth noting the new rules for waste storage or an obligation imposed on the holder of waste to establish the security of claims and the introduction of new obligations concerning receiving permits for waste collection or conversion. Applicants for a waste collection or waste conversion permit shall be required to submit to the authority, in addition to the previously required documents, additional information concerning the stored waste and the capacity of the installation, facilities, other waste storage sites, and the establishment of the security of claims if it is necessary to cover the costs of the substitute performance of the decision ordering the disposal of waste. Furthermore, in addition to the document confirming the security of claims, the applicant shall be obliged to submit a certificate proving no previous criminal convictions for environmental offenses. Consequently, people convicted of environmental crimes shall not be allowed to carry out waste management activities. In contrast, people fined with an administrative penalty for the torts listed in Article 194 of the AW shall not be granted a permit if the entrepreneur has been fined at least three times. The penalty exceeded the amount of PLN 150,000 (approximately EUR 33,000). Moreover, the issuance of a waste management permit shall be preceded by a mandatory inspection of the facility and other waste storage sites carried out by the State Fire Service inspectors. An adverse opinion issued by the State Fire Service District (Municipal) Chief will result in the competent authority to issue the decision refusing to do so [88,89].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Waste Management Structure in Poland as Compared to the EU

In the EU, in 2018, more than half of waste (54.6%) was subjected to recovery processes, including recycling (37.9%), backfilling (10.7%), or energy recovery (6.0%). The remaining waste (45.4%) was landfilled (38.4%), incinerated without energy recovery (0.7%) or disposed of in other ways (6.3%) (Table 6). Significant differences can be observed between the EU Member States in terms of using these different waste management methods. For example, Italy and Belgium achieved very high recycling rates, while most waste was landfilled in Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Finland and Sweden [90]. The leading countries in waste incineration include Germany and Denmark. In Germany, 55% of waste was incinerated with energy recovery, while in Denmark, it was 29% in 2011, with the proportion of landfill waste as only 6% [91,92]. In 2019, Poland generated 114.1 million tonnes of industrial waste, which recovered 49% of waste—43% was disposed of utilizing landfilling and 5% was disposed of in another way (including the thermal treatment of waste). It should be noted that, as part of disposal, 89% of waste was landfilled, 4% was transferred to other recipients and 2% was temporarily stored [26]. With regard to industrial waste, many companies transform post-production waste into new products, e.g., for the production of gelatine. The raw material for the production of gelatine is post-production waste from the food industry in the meat, poultry and fish industries. Such activities also have an impact on the energy and water efficiency of the production plant. Solid by-products from the meat industry are used for fodder, energy as an additive for various types of fuels and as fertilizers [93]. The data presented above show that despite applying the five-step waste hierarchy in the Polish legal system, a large proportion of the waste generated by economic activities is still landfilled. The volume of landfill waste in 2019 amounted to approximately forty-nine million tonnes, and covered a total area of over 8 thousand ha [26]. In order to check the trends in the waste management structure, data from 2016–2020 after the establishment of the Action Plan for the circular economy were analysed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Industrial waste generated and landfilled (million tonnes) and the structure of processing this waste (%) in Poland in 2016–2020 and UE-28 in 2018.

Table 6 shows a general downward trend in the generated industrial waste in 2016–2020 from 131 to 109 million tonnes. As part of the waste processing structure, the amount of waste recovered was from 48 to 50% (can be considered a constant trend) of waste, and for disposal—46–48% (upward trend), including 42% of waste landfilled. The basic method of waste disposal was landfilling (88–90%). Part of industrial waste was transferred to other recipients at the level of 0.9–2.9%, and the remaining part was temporarily stored (1–2.5%). In Poland, compared to the EU, the data showed a slightly lower share of recovered waste and a higher share of landfill waste. Moreover, in the analysed period, an increase in the waste accumulated in landfills has been observed. The data show that over 40% of industrial waste is landfilled and temporarily stored. The large mass of waste accumulated so far is also disturbing. These data prove the existing technical and organisational difficulties in neutralising this type of waste, which may contribute to illegal activities aimed at disposal of this type of waste by economic entities, such as its incineration. Too little waste is recovered and most of its landfilled. It can contribute to leakage in the waste management system. This situation has not changed over the last years. It seems that despite the implementation of the circular economy system in Poland, nothing has changed so far in the field of industrial waste management regarding recycling, i.e., processing of secondary raw materials. Therefore, the scale of the waste landfilling trend can be regarded as significant, which may contribute to the search for alternative ways to manage landfill waste, not necessarily in a legal manner.

As part of the monitoring interventions undertaken by the State Fire Service’s National Rescue and Firefighting System officers, an increase in the number of fires of both landfills and illegal dumping sites was noted. In 2012, there were 75 fires at places where waste is stored and deposited, while in 2017—132 and 2019—177 such cases throughout the country (an average of 15 fires per month). However, compared to the previous year, 2018, when the number of fires doubled in the first half of the year compared to 2017, the number of fires in 2019 decreased by 27% (243 fires) [26]. Police reports show that at least some landfill fires were caused by intentional arson, e.g., 23 out of 54 fires in 2018 used car tyres plastics [83].

4.2. Factor Analysis of the Industrial Waste Management

While analysing the factors influencing the management of economic waste, the following groups of factors were identified: political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal (Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9).

Table 7.

SWOT analysis for the industrial waste management according to PESTEL analysis classifying: political (P), economic (€), social (S), technological (T), environmental (E) and legal (L) factors.

Table 8.

SWOT analysis for industrial waste management according to PESTEL analysis for particular factors with assessment of the impact force (a scale from 1 to 5, where 1—small impact, 5—large impact).

Table 9.

Proposed industrial waste management strategy based on factor analysis.

Table 7 presents strengths and weaknesses as internal factors, and opportunities and threats as external factors that affect the industrial waste management. The opportunities as favourable factors of the industrial waste management system in accordance with the principle of sustainable development are the EU policy in the field of implementing the circular economy which implements the assumptions of the EU energy policy and the European Green Deal which complies with the principles of waste management in Directive 2018/850, as well as the introduction of stringent technical requirements for storage and disposal waste management. In this way, the strengths of this system are the transition of these rules in the Polish waste management system with rigorous technical standards in according to the waste hierarchy protecting the environment or human health. Here, it should also take into account the acceptable methods of waste management that consist in the recovery of energy from waste incineration and the recovery process, the use of waste as a fuel or other method of energy production (RDFs) and the prohibition of landfilling of high-calorific waste in Polish legislation. On the other hand, weaknesses include the waste management structure dominated by waste storage and the accumulated large mass of industrial waste, which contributes to the lack of technical and organisational disposal possibilities.

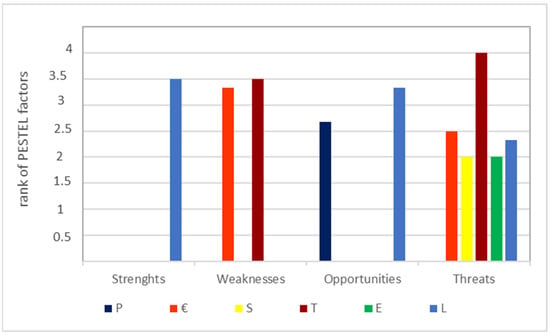

Table 8 presents the impact of the analysed factors described in Table 7. On the basis of this analysis, these factors can be ranked according to the large to small impact: technological—3.40, legal—3.15, economic—3.0 and political—2.67, and social and environmental—2.0.

On the other hand, when analysing the rank of factors in individual SWOT elements, the following findings were discovered:

Strengths—the entire legal system, i.e., the decisive factors are legal at 3.50.

Weaknesses—the technical factors at 3.50 and economic at 3.33.

Opportunities—opportunities are shaped by legal at 3.33 and political factors at 2.67.

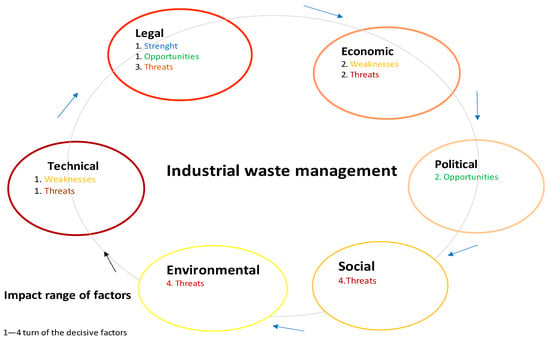

Threats—technological factors (4.0) are decisive, followed by economic and legal factors (2.55 and 2.33, respectively), as well as environmental and social factors (2.0) resulting from the negative impact of illegal landfill incineration on the environment (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The rank of PESTEL factors in four analysed groups (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats), where P—political, €—economic, S—social, T—technological, E—environmental and L—legal.

Figure 3.

The rank of key and decisive factors influencing the industrial waste management.

Based on the assessment of these factors, we proposed an industrial waste management strategy. Due to the impact on industrial waste management of factors according to the ranking, i.e., technological, legal, economic and political, and social and environmental, it is necessary to strengthen the economy in these areas (Table 9).

Table 9 shows the proposals for strengthening the areas of industrial waste management, especially in the technological, legal and economic issues directly affecting its condition. First of all, it concerns an increase in the technical potential of waste recovery methods, including energy recovery, considering legislative changes and extending the system of legal and economic instruments and the possibility of financing waste recovery installations. In the remaining analysed areas indirectly affecting industrial waste management, changes in the EU environmental and energy policy towards greater strengthening and support of waste recovery methods should be considered. However, in order to reduce environmental threats resulting from illegal activities, the monitoring and control system over the management of this waste should be strengthened. The above-mentioned measures will increase the technical possibilities of neutralising and recovering industrial waste, meeting strict emission and environmental standards, increasing the number of investments in this area, limiting illegal activities, and reducing the emission of pollutants into the environment, which will improve the quality of environmental resources and life of the society.

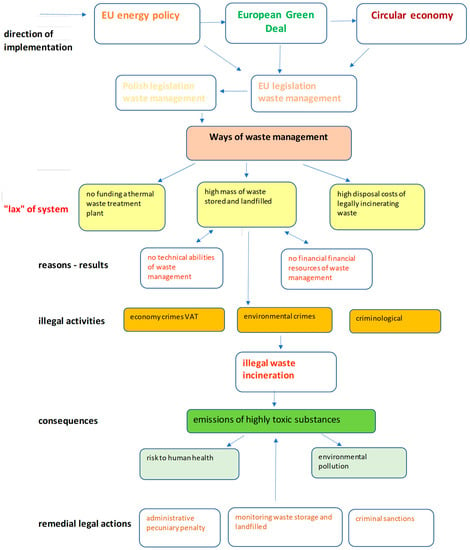

In the last stage of the analysis of the industrial waste management system, the relationship between the application of the existing regulations concerning closed-loop waste management and the effectiveness of methods, ways and economic instruments preventing the illegal burning of landfill waste were determined. The diagram of the industrial waste management system in Poland is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the industrial waste management system in Poland.

When analysing the waste management system in Poland, as shown in Figure 4, the following advantages and disadvantages (limitations) should be indicated:

Advantages

- (1)

- This system is based on EU regulations contained in the Framework Waste Directive 2008/98/EC, which defines the hierarchy of waste management, preferring recovery methods with landfilling as the last resort, as well as other Directives regulating the technical and organisational requirements of waste recovery and disposal methods.

- (2)

- That system complies with the principles of the circular economy, implementing the guidelines of the EU Energy policy and European Green Deal and favouring the recovery and recycling of secondary raw materials.

- (3)

- EU regulations have been implemented with Polish legislation to the Waste Act of 2012 and regulations specifying technical and organisational requirements for waste recovery and disposal methods.

- (4)

- The Polish regulations seem to be consistent with the EU law, regulating in detail the technical requirements of waste recovery and disposal methods.

- (5)

- The legal system of industrial waste management in Poland is, therefore, strongly anchored in EU regulations, and according to the factor analysis, its strengths have a large direct impact, apart from technological and economic factors, on the current state of waste management.

Disadvantages (limitations)

- (1)

- The disadvantages of the industrial waste management system arise mainly from the direct influence of technological and economic factors constituting the weaknesses of this system. Having analysed the waste management structure in Poland, it has to be stated that a substantial amount of industrial waste is still temporarily stored and landfilled compared to certain EU countries, as well as the increasing mass of landfilled accumulated waste. Therefore, too much waste is generated and insufficiently processed in recovery processes and is thermally transformed with energy recovery. However, according to the current EU guidelines in Regulation 2020/852, the thermal treatment of waste with energy recovery has been considered a non-ecological method and not the preferred method for implementing a circular economy. This may be one of the reasons why waste management is not closed.

- (2)

- Too much mass of landfill waste caused problems with its recovery. The reasons for this state of affair should be sought with the lack of organisational, technical and financial possibilities to process such a large mass of landfill waste. This is evidenced by the large direct influence of technical and economic factors. This is linked to the very high costs of legally incinerating waste, i.e., in facilities that comply with the BAT requirements and meet emission standards and environmental protection requirements. Thus, the system seems ineffective, inefficient and leaky. Consequently, alternative (and not always legal) ways to dispose of such waste are sought, including setting fire to waste landfill sites. This constitutes a major threat to the industrial waste management system, as evidenced by the decisive influence of the technical, but also economic (high costs of decommissioning these facilities, costs of repairing environmental damage) and legal factors in the form of other illegal activities in the field of economic and criminological law.

- (3)

- The consequence of this situation is the damage to the environment, which limits the availability of environmental resources for economic activity and worsens the quality of life of society, as evidenced by the indirect influence of social and environmental factors.

In Poland, attempts have been made to resolve this problem by tightening up formal requirements in the form of financial guarantees; the detailed expansion of the provisions on administrative decisions regarding waste collection and storage, including fire protection; an obligation to monitor landfill sites; shortening the permitted period of waste storage; and increasing the level of criminal sanctions. In this way, the above-mentioned legislative measures will enable a more effective verification and selection of entities that are suitably qualified and, above all, are technically capable of managing waste properly without posing a threat to humans and the environment.

5. Conclusions

The current approach to waste management in the EU is to adapt it to a circular economy, which implements the provisions of the EU energy policy and the European Green Deal. This economy involves increasing the proportion of waste recycling and recovery, i.e., extending the life span of secondary raw materials derived from waste and its incineration with energy recovery. Therefore, the industrial waste management system in Poland should be based on these principles. Based on the analysis of the legal status and factor analysis, the advantages and disadvantages of this system were identified. The most decisive factors for the development of the industrial waste economy are legal regulations, technical conditions and economic opportunities. However, the reasons for the lack of closure of this system can be found in the shortcomings in these analysed areas. This allowed for the formulation of remedial postulates. The introduced provisions should be more effective. However, for the sanctions to be effective, they must also be present in the proper proceedings. The entity responsible for the disposal/management of waste in a legal manner is its holder/entity dealing with waste management. However, their liability may be significantly limited in the case of long-term proceedings or failure to identify them, e.g., in the case of liquidation of the company before fulfilling the obligation to dispose of waste or set it on fire. Thus, the mere establishment of legal provisions and criminal sanctions is not necessarily effective, as appropriate instruments for their enforcement are needed. Perhaps entrepreneurs operating in waste management should be subsidized to increase the profitability of waste recovery and disposal and prevent illegal activities.

According to our proposed industrial waste management strategy, it should be strengthened primarily in the technological, legal and economic areas. The waste management system in Poland should be oriented towards increased waste recovery, including energy and fuel recovery during waste incineration, and a more significant reduction in the volume of temporarily stored waste and landfill waste under the circular economy recommendations. Waste management also needs to implement the current EU system that favours the Right to Repair principle, which requires producing more durable, repairable electrical and electronic devices, thus, reducing waste. Therefore, co-financing producers as part of qualifying their activities as sustainable investments could be a good solution for the circular economy and the environment.

In summary, a comprehensive factor analysis of the industrial waste management system, which allows to determine the strengths and weaknesses, as well as opportunities and threats of this system, made it possible to identify legal gaps and possible reasons for not closing this system. The consequence of this is, i.e., illegal waste incineration. The identification of all these aspects constitutes the added value of the article. Moreover, the legal solutions taken to reduce the trend of illegal landfill waste burning can serve as an example of legislative changes in waste management and energy policy and can be useful for applications in other EU countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; methodology, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; software, E.M.Z.; validation, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; formal analysis, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; investigation, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; resources, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; data curation, E.M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; visualization, E.M.Z.; supervision, E.M.Z. and J.J.Z.; project administration, E.M.Z.; funding acquisition, J.J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Parliament. Energy Policy—General Principles. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/68/energy-policy-general-principles (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Leveque, F.; Glachant, J.M.; Barquin, J.; Holz, F.; Nuttall, W. (Eds.) Security of Energy Supply in Europe Natural Gas, Nuclear and Hydrogen; Loyola de Palacio Series on European Energy Policy; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, T.M. Considering environmental costs of greenhouse gas emissions for setting a CO2 tax: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 720, 137524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadhukhan, I. Net-Zero Action Recommendations for Scope 3 Emission Mitigation Using Life Cycle Assessment. Energies 2022, 15, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miciuła, I. Polityka energetyczna Unii Europejskiej do 2030 roku w ramach zrównoważonego rozwoju. Stud. Pr. Wydziału Nauk. Ekon. Zarządzania 2015, 42, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; The European Green Deal. No. COM/2019/640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. ’Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality; No. COM/2021/550 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- European Commission. Communication on the Sustainable Consumption and Production and Sustainable Industrial Policy Action Plan/*COM/2008/397/3. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0397:FIN:en:PDF (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Pearce, D.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.S. An introductory note on the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranic, I.; Behrens, A.; Topi, C. Understanding the Circular Economy in Europe, from Resource Efficiency to Sharing Platforms. CEPS Special Reports No. 143. 2016. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2859414 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; No. COM (2015) 614/2); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K.; Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G.; Tornese, F. Measuring circular economy strategies through index methods: A critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 312, 3–30.

- Robaina, M.; Villar, J.; Pereira, E.T. The determinants for a circular economy in Europe. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 12566–12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech, T.; Bahn-Walkowiak, B. Transition Towards a Resource Efficient Circular Economy in Europe: Policy Lessons from the EU and the Member States. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 155, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilts, H.; von Gries, N. Europe’s waste incineration capacities in a circular economy. Waste Resour. Manag. 2015, 168, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 75/442/EEC of 15 July 1975 on waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 1975, 194, 47–49.

- Nash, H.A. The Revised Directive on Waste: Resolving Legislative Tensions in Waste Management? J. Environ. Law 2009, 21, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste Act of 27 April 2001. Law Journal, 2010; 185/1243, consolidated text.

- Waste Act of 14 December 2012. Law Journal, 2021; 779, consolidated text.

- Hall, D.; Nguyen, T.A. Waste Management in Europe: Companies, Structure and Employment. Available online: https://www.epsu.org/sites/default/files/article/files/2012_Waste_mngt_EWC.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Domańska, W. (Ed.) Environmental Protection: Statistical Analyses; GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2020,1,21.html (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Farmaki, P.; Tranoulidis, A.; Antoniadis, I. Opportunities for Developing an Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management System in Greece: A Legal and Financial Framework. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2017, 11, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Slaybaugh, J.A. Garbage day: Will Italy finally take out its trash in the land of fires? Wash. Int. Law J. Assoc. 2016, 26, 179–207. [Google Scholar]

- Sedova, B. On the causes of illegal waste dumping in Slovakia. J. Environ. Plann. Man. 2016, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Jones, P.; Ettlinger, S. Waste Crime: Tackling Britain’s Dirty Secret; Report, No. 1118486; ESAET: London, UK, 2014; Available online: http://www.esauk.org/application/files/4515/3589/6453/ESAET_Waste_Crime_Tackling_Britains_Dirty_Secret_LIVE.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Świątkowski, A.; Makles, Z.; Grybowska, S. Niebezpieczne Dioksyny; Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Assamoi, B.; Lawryshyn, Y. The environmental comparison of landfilling vs. incineration of MSW accounting for waste diversion. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, A.; Piscitelli, P.; Neglia, C.; Rosa, G.D.; Iannuzzi, L. Illegal Dumping of Toxic Waste and Its Effects on Human Health in Campania, Italy. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6818–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triassi, M.; Alfano, R.; Illario, M.; Nardone, A.; Caporale, O.; Montuori, P. Environmental Pollution from Illegal Waste Disposal and Health Effects: A Review on the ‘Triangle of Death. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1216–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zębek, E. Gospodarka Odpadami w Ujęciu Prawnym i Środowiskowym; KPP University of Warmia and Mazury Press: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R.K.; Alavalapati, J.R.R.; Kalmbacher, R.S. Exploring the potential for silvopasture adoption in south-central Florida: An application of SWOT-AHP method. Agric. Syst. 2004, 81, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obłój, K. Strategia Organizacji; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. Conclusions on the 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework; Report SN 79/14, 24 October 2014; European Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/145356.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Morata, F.; Sandoval, S.I. European Energy Policy; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. European Green Deal. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pl/policies/green-deal/https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pl/policies/green-deal (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal; ESDN Report; ESDN: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.esdn.eu/fileadmin/ESDN_Reports/ESDN_Report_2_2020.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- European Commission. EU Strategy on Energy System Integration. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-systems-integration/eu-strategy-energy-system-integration_pl (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. The Role of Waste-to-Energy in the Circular Economy; No. COM (2017) 34 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Szczygieł, E. Circular economy—A new concept or a necessity. Sprawy Międzynarodowe 2021, 74, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2000/76/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 December 2000 on the incineration of waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2000, 332, 91–111.

- Council Directive 1999/31/EC of 26 April 1999 on the landfill of waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 1999, 182, 1–19.

- Directive (EU) 2018/850 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 1999/31/EC on the landfill of waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 150, 100–108.

- Wiśniewska, E. Najlepsze dostępne techniki (BAT) jako instrument ochrony środowiska. Inżynieria Ochr. Sr. 2015, 18, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Best Available Techniques (BAT) for Preventing and Controlling Industrial Pollution, Activity 4: Guidance Document on Determining BAT, BAT-Associated Environmental Performance Levels and BAT-Based Permit Conditions; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/risk-management/guidance-document-on-determining-best-available-techniques.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Council Directive 96/61/EC of 24 September 1996 concerning integrated pollution prevention and control (IPPC). Off. J. Eur. Union 1996, 257, 26–40.

- Act of 27 April 2001 Environmental Protection Law. Law Journal, 2021; 1973, consolidated text.

- Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/1147 of 10 August 2018 establishing best available techniques (BAT) conclusions for waste treatment, under Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council C/2018/5070. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 208/38, 1–53.

- European Commission. Directorate General Environment Refuse Derived Fuel, Current Practice and Perspectives (B4-3040/2000/306517/Mar/E3); Final Report WRc Ref: CO5087-4; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/waste/studies/rdf.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Zięty, J.J.; Olba-Zięty, E.; Stolarski, M.J.; Krzykowski, M.; Krzyżaniak, M. Legal Framework for the Sustainable Production of Short Rotation Coppice Biomass for Bioeconomy and Bioenergy. Energies 2022, 15, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faaij, A.P.C. Repairing What Policy Is Missing Out on: A Constructive View on Prospects and Preconditions for Sustainable Biobased Economy Options to Mitigate and Adapt to Climate Change. Energies 2022, 15, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonti, D.; Panoutsou, C. Policy measures for sustainable sunflower cropping in EU-MED marginal lands amended by biochar: Case study in Tuscany, Italy. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 126, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, T.; Vignesh, P.; Arun Kumar, G. Refuse Derived Fuel to Electricity. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2013, 2, 2930–2932. [Google Scholar]

- Tojo, N.; Neubauer, A.; Bräuer, I. Waste Management Policies and Policy Instruments in Europe: An Overview; IIIEE Reports, No. 2008:02; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2008; Available online: https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/project/2015/documents/holiwastd1-1_iiiee_report_2__0.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Persson, U.; Münster, M. Current and future prospects for heat recovery from waste in European district heating systems: A literature and data review. Energy 2016, 110, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Landfill Directive 99/31/EC.; Workshop on EU Legislation Waste; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- IMPEL LANDFILL PROJECT. Landfill Directive Implementation. Analysis of the Gaps Found during the Running of the Landfill Project, 2016. Available online: https://www.impel.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/FR-2016-08-Landfill-Directive-Implementation-Gaps-Analysis.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Jerzmański, J. Zasada bliskości w gospodarce odpadami. Przegląd Komunal. 2010, 2, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniowski, P. Model Prawny Systemu Gospodarki Odpadami. Studium Administracyjnoprawne; University Lodz Press: Lodz, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Danecka, D.; Radecki, W. Ustawa o Odpadach. Komentarz; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Szuma, K. Wybrane problemy gospodarowania odpadami w świetle założeń Deklaracji RIO+20 ‘Przyszłość, jaką chcemy mieć’. Białostockie Stud. Prawnicze 2013, 14, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajca, P.; Zajemska, M. Ocena możliwości wykorzystania paliwa RDF na cele energetyczne. Rynek Energii 2018, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bień, J. Production and use of waste-derived fuels in Poland: Current status and perspectives. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2021, 27, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zębek, E.; Raczkowski, M. Prawne i techniczne aspekty gospodarowania odpadami komunalnymi. Przegląd Prawa Ochr. Sr. 2014, 3, 22–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Regulation of the Minister of Climate of 11 September 2020 on complex requirements for waste storage. Law Journal, 2020; 1742.

- Regulation of the Minister of Development of 21 January 2016 on the requirements for the thermal process of waste conversion and methods of handling the waste generated in the process. Law Journal, 2016; 108.

- Regulation of the Minister of Climate of 24 September 2020 on the emission standards for certain types of installations, fuel combustion sources, and waste incineration or co-incineration facilities. Law Journal, 2020; 1860.

- Regulation of the Minister of Economy of 16 July 2015 on the acceptance of waste for landfilling. Law Journal, 2015; 1277.

- Regulation of the Minister of Environment of 30 April 2013 on landfills. Law Journal, 2013; item 523.

- Regulation of the Minister of Climate and Environment of 19 March 2021 amending the ordinance on landfills. Law Journal, 2021; 673.

- Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088. Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, 198, 13–43.

- Krzykowski, M.; Mariański, M.; Zięty, J.J. Principle of reasonable and legitimate expectations in international law as a premise for investments in the energy sector. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2021, 21, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, M.; Bartczak, A.; Markiewicz, O.; Markowska, A. Porównanie kosztów zewnętrznych wybranych metod składowania stałych odpadów komunalnych. Ekon. Sr. 2007, 2, 120–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ożóg, I. Przestępstwa Karuzelowe i Inne Oszustwa w VAT.; Wolters Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Order of the Court of Justice of 6 February 2014, C-33/13. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 175/16, 10.6.2014. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/faed0856-f068-11e3-8cd4-01aa75ed71a1/language-pl (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Judgment of the Provincial Administrative Court in Warsaw of 8 June 2021, III SA/Wa 2138/20, LEX no. 3279508. Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/orzeczenia-i-pisma-urzedowe/orzeczenia-sadow/vi-sa-wa-2138-20-wyrok-wojewodzkiego-sadu-523373204 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Judgment of the Provincial Administrative Court in Gliwice of 21 August 2019, I SA/Gl 417/19, LEX no. 2717417. Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/orzeczenia-i-pisma-urzedowe/orzeczenia-sadow/i-sa-gl-417-19-obowiazek-udowodnienia-zarzutu-522811113 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- NIK. Przeciwdziałanie Wprowadzaniu do Obrotu Gospodarczego Faktur Dokumentujących Czynności Fikcyjne; Report, No. 24/2016/P/15/011/KBF; NIK: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chorbot, P. Nielegalny Obrót Odpadami. Studium Prawnokarne i Kryminologiczne; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Act of 20 July 1991 on the Environmental Protection Inspectorate. Law Journal, 2018; 1471, 1479, consolidated text.

- Act of 20 July 2018 amending the Act on Waste and certain other acts. Law Journal, 2018; 1592.

- Act of 13 April 2007 on the prevention and remediation of environmental damage. Law Journal, 2020; 2187, consolidated text.

- Criminal Code of 6 June of 1997. Law Journal, 2021; 2345, 2447, consolidated text.

- Ćwiek, P. Zezwolenie na gospodarowanie odpadami po zmianach z 20 lipca 2018 r. LEX/el., 2020. Available online: https://www.lex.pl/dostosowanie-zezwolen-odpadowych-5032020,5653.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Zębek, E. Aktualne problemy prawne w gospodarce odpadami. In Aktualne Problemy Prawa i Samorządu Terytorialnego: 25 lat Rozwoju: Od Katedry Prawa i Samorządu Terytorialnego Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogicznej w Olsztynie do Wydziału Prawa i Administracji oraz Katedry Prawa Administracyjnego i Nauki o Administracji Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego w Olsztynie; Dobkowski, J., Sobotko, P., Goerick, J., Eds.; University of Warmia and Mazury Press: Olsztyn, Poland; pp. 155–165.

- Eurostat. Statistics Explained, Waste Treatment by Type of Recovery and Disposal, 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-xplained/index.php?title=File:Waste_treatment_by_type_of_recoveryand_disposal,_2018_(%25_of_total_treatment)_30-04-2021.png (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Kirkeby, J.; Grohnheit, P.E.; Møller, A.F.; Herrmann, I.T.; Karlsson, K.B. Experiences with Waste Incineration for Energy Production in Denmark; Department of Management Engineering, Technical University of Denmark: Roskilde, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jaron, A.; Kossmann, C. Waste Management in Germany 2018; Public Relations Division No. 11055; Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU): Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak, A.; Błyszczek, E. Kierunki zagospodarowania produktów ubocznych z przemysłu mięsnego. Chemia 2009, 4, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bochenek, D. (Ed.) Ochrona Środowiska; GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2017,1,18.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Domańska, W. (Ed.) Ochrona Środowiska; GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2018,1,19.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Domańska, W. (Ed.) Ochrona Środowiska; GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2019,1,20.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Domańska, W. (Ed.) Ochrona Środowiska; GUS: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2021,1,22.html (accessed on 25 September 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).