Abstract

To meet the expanding energy demand, all available energy sources must be utilized. Renewable energies are both eternal and natural, but their major downside is their inconsistency. Due to the rising costs of fossil fuels and the CO2 they emit, hybrid renewable energy (HRE) sources have gained popularity as an alternative in remote and rural areas. To address this issue, a hybrid renewable energy system (HRES) can be developed by combining several energy sources. In order to build modern electrical grids that have advantages for the economy, environment, and society, the hybrid system is preferable. A summary of various optimization methods (modeling techniques) of an HRES is presented in this paper. This study offers an in-depth analysis of the best sizing, control methodologies, and energy management strategies, along with the incorporation of various renewable energy sources to form a hybrid system. Modern hybrid renewable energy system utilities rely more on an optimal design to reduce the cost function. Reviews of several mathematical models put out by various academicians are presented in this work. These models were created based on reliability analyses incorporating design factors, objective functions, and economics. The reader will get familiar with numerous system modelling optimization strategies after reading this study, and they will be able to compare different models based on their cost functions. Numerous modeling approaches and software simulation tools have been created to aid stakeholders in the planning, research, and development of HRES. The optimal use of renewable energy potential and the meticulous creation of applicable designs are closely tied to the full analysis of these undoubtedly complicated systems. In this field, as well, several optimization restrictions and objectives have been applied. Overall, the optimization, sizing, and control of HRES are covered in this paper with the energy management strategies.

1. Introduction

Solar energy is the most cost-effective way for India to meet its future energy needs. Solar energy is becoming more affordable in India, attracting buyers interested in environmentally friendly energy sources [1]. Until 2015, the majority of Indian cities had no solar power plants. As a result, improved hybrid PV facilities will be required to meet future energy demand. This research may be used to aid in the selection of the optimal hybrid PV system for a smart city, taking into account the specialized displays as well as environmental and economic concerns [2]. HRES are one of the most viable and dependable alternatives to the main power grid for electrifying rural consumers, as they help to reduce fossil fuel consumption while mitigating climate change [3]. An HRES has the advantages such as high reliability, less energy storage capacity needed, increased efficiency, modularity, and minimized LCOE over single-energy-source-based systems [4,5].

To meet the global energy demand, industry will continue to devour all available resources in the near future. Due to the coronavirus epidemic and total shutdown, global energy consumption fell 5.9% in 2020 compared to 2019 [6]. New wind and solar projects built in recent years have increased productivity. Renewables usually obtain grid preference, so they do not have to adjust their production to match demand [7]. According to Exxon Mobil’s most current energy prediction [8], green and nuclear energy will contribute to around 25% of global power in 2040.

Poorly structured and disorganized HRES project development can lead to higher-than-expected investment costs. As a result, various modeling and methodologies and simulation software have been used to assist HRES stakeholders in their research, planning, and development efforts [9]. In reality, HRES simulation includes calculating numerical formulas that outline the mathematical models for the function of the relevant HRES components. As a result, the system’s behavior can be illustrated, and the decision-making process for the project can be aided [10]. It is worth noting that the simulation algorithms generate non-identical combinations of renewable energy systems based on the user’s input parameters (for example, meteorological data and size parameter range) [11,12]. The non-identical combinations of the various simulation approaches can be attributed to their inherent diverse dispatch strategies [13]. Given the system components, the terrain of the area, and the meteorological data, the HRES performance optimization must be performed with a method that is proven to work [14].

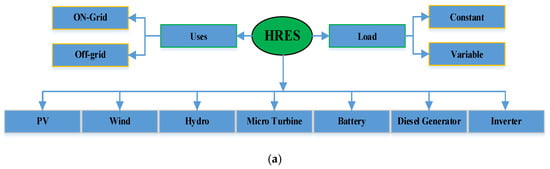

Figure 1 depicts the parameters that comprise a relevant HRES optimization process. Regardless of its complexity, an efficient understanding, analysis, design, and planning of an HRES project necessitates conducting a thorough theoretical prefeasibility analysis and thoroughly examining the validity of its results using specialized simulation software and relevant scenarios used as case studies [4,11]. As a result, a comprehensive HRES study is directly related to effective RES utilization and precise project design [15]. The “Holy Grail” for HRES optimization in this area is to use a well-designed and efficient sizing method that works [16]. One ideal size methodology is needed to properly and cost-effectively utilize renewable energy supplies. By fully using the PV, WT, and battery bank, the best size approach may assist in securing the lowest investment, allowing the hybrid system to function at its most cost-effective and dependable levels. When you set cost goals and look at the system’s performance over time, you can obtain the best balance of dependability and cost [17]. An HRES is a type of electrical system that combines one renewable energy source with several others. The system may be used on or off the grid, and it can employ traditional, sustainable, or hybrid energy sources [18]. Many commercial software programs, including HOMER, iHOGA, PVSyst, PVSOL, TRNSYS, RETScreen, INSEL, and others, have been found to be useful in sizing and optimizing HRES [19].

Figure 1.

(a,b) An HRES optimization methodology.

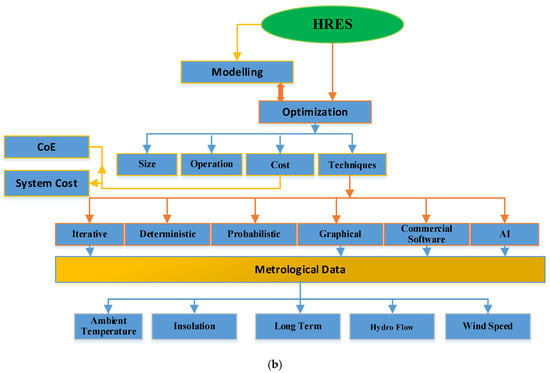

R. Siddaiah et al., focuses on most current methodologies published for sizing a PV/wind hybrid system, as well as a quick assessment of advancements in optimization methods, cost analysis tools, and storage system strategies [20]. S. Dawoud et al., focus on unique approaches offered in hybrid energy practice based on physical modelling with diverse hybrid network optimization processes [21]. Vivas et al., reviewed the most recent research on off-grid renewable energy systems using hydrogen storage technology [22]. Tezer et al. [23] looked at how multi-objective optimization strategies for system cost and durability have progressed over the previous two decades. In a feasibility study, Khare et al. looked at optimal size, modelling, control components, and reliability issues. Furthermore, this review [24] discusses the use of development technologies and game theory in the construction of HRES. Energy management measures must be employed to ensure the appropriate functioning of HRES, as well as to sustain demand and improve performance. A well-thought-out energy management strategy allows the system to meet demand while simultaneously prolonging the life of system components, minimizing operational costs and enhancing the use of RES. It also allows the system to conserve energy, prevent elements from being damaged by overload, and improve the power system’s reliability, all of which lead to improved system performance [6]. Energy needs and RE provisioning approaches, energy frameworks, HRES deployment, and energy readiness management were all examined by Y. Liu et al., SPV, WT, DGs, and battery solutions that are more efficient have all been proved [25]. Figure 2 depicts the number of publications for HRES (1992 to 2022) based on various configurations.

Figure 2.

Number of Publications for HRES (1992 to 2022) depending on various configurations.

The majority of renewable energy installations are used to power off-grid locations or to fulfill global network demand (buildings, industry, and the residential sector). This section will concentrate on the most commonly used HRES energy consumption profile. Isolated area: This type of load can be an island, a small settlement in the Sahara, a mountain, or a small number of houses off the grid; dwelling sector: This sort of load varies depending on the location of the resident (poor or wealthy country) and the amount of appliances installed; industry: due to technical and economic constraints, such as the need for a vast space, the continuity of energy production, the quality of energy, and the need for a substantial investment fund, this type is rarely explored by researchers in their investigations; buildings: this sort of building can be a market, a university, a laboratory, an administration, an education facility, etc., and it is defined by low consumption (few kilowatts) and grid connectivity, transportation, etc.) [26].

This study gives a thorough review of the most recent HRES research along four important axes: sizing (using commercial software or a traditional and new generation approach), optimization (conventional, novel generation, and hybrid methods), planning and controlling (centralized, distributed, hybrid, and new generation methods), and energy management (technical goal-oriented strategy, economic goal-oriented strategy, and techno-economic goal-oriented strategy). This research also focuses on the most recent hybrid system approaches that have been published and established, as well as the generators used in these systems. At the end of the section, there is a detailed comparison of algorithm applications, as well as their benefits and drawbacks.

The following is a summary of the current study’s novelty:

- According to a study framework on energy consumption profiles, when HRES is adjusted technically and economically using sophisticated optimization techniques or commercial software, it may successfully meet energy demand in remote places.

- HRES is frequently optimized using advanced optimization techniques such as fuzzy logic, ANNs, and evolutionary algorithms. The most prevalent commercial scaling software is HOMER PRO and RET Screen.

- The most frequently used control technology for providing stability, protection, and power balancing is MPPT (based on PSO, neural networks, and fuzzy logic).

- In order to choose the finest one, the current literature study exposes advanced optimization approaches and software.

- This paper discusses the objective function, figures of merit, limitations, conclusions, challenges, and future research.

This paper is divided into six sections: The Section 1 is an introduction; the Section 2 dealt with HRES optimization methods (modeling techniques) in depth; and the Section 3 discusses the method for sizing an HRES. The Section 4 is about the HRES control mechanism and management strategy. In the Section 5, challenges and further studies of an HRES are discussed. Finally, Section 6 is made of this study in the sixth section.

2. HRES Optimization Methods (Modeling Techniques)

In a hybrid system, there are numerous objectives that need to be optimized, such as size, modeling, control, and management [27]. In this section, a list of the most often utilized optimization methods in recent years is compiled. Subramanian et al., categorized energy systems modeling methodologies into two groups based on modeling approach and application area requirements [10]. Ghofrani and Hosseini [28] used a different approach and divided the major optimization algorithms into three categories: classical algorithms, metaheuristics algorithms, and hybrids energy system modelling strategies were classified as analytical, simulation, or MCS (Monte Carlo simulations) methods by Tina et al. [29] and Khatod et al. [30]. The last category included three modeling sub-approaches depending on input variable management techniques. Simple time series, probabilistic approaches, and average daily (or even monthly) energy balance values were also considered. The numerous optimization strategies discussed can be grouped into two main groups, according to another approach [10,17,31]: traditional optimization techniques and next generation optimization approach techniques. The modelling approaches reported in this study are grouped into three categories according to the structure employed by most scientists in the HRES “enterprise,” as illustrated in Table 1 as:

Table 1.

Modeling techniques overview.

2.1. Conventional Optimization Techniques

The iterative technique uses a series of mathematical simulations to arrive at a set of roughly approximated outcomes that may be used to address the problem at hand. The simulations are run on a computer until all of the conditions are fulfilled [10]. To be more specific, iterative approaches are used to perform the linear adjustment of the values supplied to HRES decision variables, resulting in a scan of all potential generating unit configurations. In this light, the computation of how dependable the system’s power may be by evaluating each design, as well as the ideal configuration, is discovered. The evolutionary algorithm (sometimes known as a heuristic approach) is a development of the well-known iterative technique. Despite the faults that result in a localized rather than a global optimum solution, the number of choice variables has minimal impact on the evolutionary process; its growth is proportional to an exponential increase in simulation time [61]. Linear programming techniques [32,33], dynamic programming techniques [34,35], and multi-objective optimization approaches [36,37,38] are examples of iterative techniques. Probabilistic approaches are defined as a statistical explanation of the design of each variable, awarding random values based on the data imported. Hourly or daily simulations are carried out [10,29,39,40]. On the other side, deterministic approaches look at load demand and resources as predictable quantities with known time-series variation [41,42,43]. Graphical construction procedures are created when the optimization functions and the outlines are drawn in the same graph. These strategies can solve the optimization problem [10,44,45] by focusing on the region of implementation. Table 2 outlines several common optimization strategies.

Table 2.

Conventional optimization techniques used in HRES.

2.2. New Generation Optimization Techniques

Metaheuristics optimization approaches can be used to describe the techniques in this area: GA approaches are global search heuristics, which are subsets of evolutionary algorithms [10]. They are elitist search techniques with a simulation in which the greatest individual in a generation is passed on to the next generation without degeneration [29]. GA employs Darwin’s theory to describe the survival of species in a population, which consists of three fundamental processes (selection, crossover, and mutation) and three critical regulatory parameters (population size, crossover, and mutation rates) [58,59]. Following a random selection of people from the initial population (“the parents”), the three major processes are used to create the “children” for the following generation. After that, the technique continues with consecutive generations of individual solution adjustments until the required optimal population evolution is achieved [66]. By using broad crossover and mutation procedures that produce new populations at every stage of the process, GA avoids jeopardizing adherence to the local optimum. Nonetheless, in order to solve the optimization problem, GA requires a huge number of control decision variables as input. It’s crucial to figure out what the best controlling coefficients are, because changing them can change the algorithm’s performance [58]. M. Paulitschke et al., employed a GA to build and optimize a hybrid system for feeding remote locations in Senegal that included a solar generator, WT, DG, and storage system (battery). This research has two goals: one is economic, and the other is environmental. The first aim is to lower the level cost of the system, and the second is to reduce CO2 emissions. The data reveals an inverse relationship between levelized cost and CO2 emissions, with CO2 emissions declining from 762.08 to 11.89 per year when leveled cost rises from 1.22 to 2.05 €/kWh [67].

ANNs are computational (or mathematical) models based on biological neural networks [17]. They use a connectionist approach to simulation to depict the assessed system’s intermediate solutions and analyze the incoming data. They’re made up of linked artificial neuron clusters [68,69]. Amirtharaj et al. AGONN’s approach [70] is a hybrid of ANN and AGOA that leverages ANN to determine optimal utilization and reduce switching loss in a system. In terms of current, voltage, and power signal, the results reveal that the proposed methodology outperforms the GOA, CMBSNN, and WOANN.

PID controllers use FL to calculate the error as well as the change in error between the actual outputs and the reference (or control) inputs. The scaled values are accepted by the “main controller” at the controller’s operational level (fuzzification (or input) stage) depending on the decision-making mechanism (fuzzy inference (or processing) stage). The defuzzification (or output) step generates the output values, which are then fed into the fuzzification stage. It’s vital to continue the technique until you have an ideal result (error convergence to zero) [47]. Derrouazin et al. employed FL multi inlet/outlet to regulate the energy flux of a hybrid system that included SPV, WT, and batteries. The results show that the electronic switches’ signals accurately and quickly track the hybrid power system’s imposed input power states [71].

PSO [72] is a technique for population-based evolutionary simulation. Its prominence is expanding due to its quick convergence and ease of usage in single-peak and multisensory activities. Swarm optimization [48] is a method inspired by nature that optimizes non-linear functions by imitating bird flocking and fish schooling. Its accuracy [50] is related to its popularity as the most widely used metaheuristic algorithm [49]. To achieve the global optimum, each iteration stage computes the position and velocity of each particle in the swarm individually. In order to achieve the required outcome, each particle records two possible values: pbest (the best solution discovered thus far) and swarm best (the best solution found by the entire swarm) [54]. According to Kennedy and Eberhart [48], the tracking of the aforementioned data is conceptually similar to the GA crossover procedure. When Bilal et al. blended this methodology with a GA to enhance a hybrid model based on SPV and CSP with battery, the results demonstrated an improvement in both financial (leveled expense of 16.33€/kWh) and technological (static effectiveness of 10.92% and 305,940 MWh energy output) parameters when compared to other approaches and processes [73].

SA [52,53,54] is a strategy used to tackle discrete search space optimization issues. TLBO [58] is a population-based approach that uses two phases for simulation, similar to GA and ABC. It is based on the conventional classroom technique (teaching–learning). The learner/student and the instructor (who is receiving instruction from the teacher) are the two phases (during the final phase, each person strives to develop by engaging with other students). The population to achieve the global solution in this nature-inspired method is a group of students. The numerous optimization problems control variables produce the various subjects proportionally allotted to the learners. Each learner is assigned a value grade for each subject that corresponds to a possible alternative, and the quality of the proposed answer is reflected in the overall mean grade. The greatest response for the entire population is represented by the instructor [57].

The ACO is a straightforward and trustworthy heuristic search strategy that mimics ant behavior physiologically. It is used for highly non-linear situations [54,55,56,57] when there is no utility in adopting standard procedures. A recently created metaheuristic approach is inspired by the well-structured work division and organization that includes employed bees, observer bees, and scout bees. Honeybees’ natural waggle-dancing behavior for foraging reasons [49] inspired ABC. Scout bees are in charge of exploration, whereas spectator bees are in charge of exploitation [47]. The ABC approach achieves the global optima while avoiding the local optima by ignoring Hessian and gradient matrix data while using population-based stochastic principles. The ABC techniques include two steps: initialization and repetition, with the latter separated into three categories: engaged bee step, bystander bee step, and Scout bee step [49]. Some new generation optimization techniques in Table 3.

Table 3.

A list of the new generation optimization techniques.

2.3. Hybrid Techniques

A hybrid technique is any approach that combines two or more algorithms in order to take use of the benefits of each algorithm while overcoming the shortcomings of the single algorithm [27]. SA-CS [85], CSHSSA, IHSCSA [74], and HSSA [86] are only a few of the hybrid approaches for optimizing hybrid systems that have been developed in recent years. There are other hybrid approaches [87], GAPSO [88], MOCSA [80], GMDHMNN- MFFOA [89], and others, which integrate Monte Carlo simulation with numerous energy-balance/financial equations [90]. Table 4 highlights several hybrid optimization strategies as:

Table 4.

A list of hybrid optimization techniques.

2.4. Evaluation of Various Optimization Techniques

Optimization techniques are distinguished by their high performance, capacity to tackle difficult problems, and ability to apply many objective functions. The most common disadvantage of all optimization approaches, however, is that they take too long and are difficult. Traditional techniques to economic optimization are the most successful, but they have a limited number of optimization parameters. Due to the sophisticated procedure and codes utilized, the new generation optimization approach requires high hardware performance to function. The efficacy and speed of this strategy, as well as its precision, are its primary advantages. Integrating classical and new generation optimization approaches reveals a methodology with great speed and resilience, but it also necessitates advanced design and difficult code generation. The Table 5 highlights the benefits and downsides of each optimization method:

Table 5.

Benefits and downsides of each optimization techniques [19,20,26,91].

3. Methods for Sizing an HRES

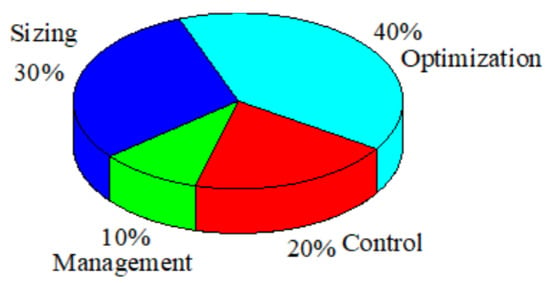

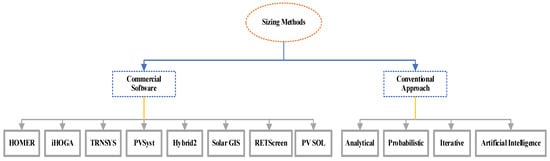

The hybrid system’s size is a crucial factor in determining the generators’ capabilities. The system may be undersized or enormous if it is not properly sized. The most difficult part is calculating true load and step time so that oscillations can be adequately accounted for. Most studies, on the other hand, use data samples of a few hours, days, or months [91]. There are two sorts of sizing methods: software-based and conventional approaches as shown in Figure 3 as:

Figure 3.

Methods of sizing.

3.1. Software for an HRES Sizing

There are several commercial apps for scaling hybrid systems, and the bulk of them, such as RET Screen, iHOGA, INSEL, HOMER, ReOpt, SAM, and WISDEM, operate on Windows and utilize the programming language Visual C++ [92]. Baneshi et al. size a hybrid system in Shiraz, Iran, that comprises a DG, SPV, and WT, as well as a storage system (battery), using the HOMER software tool. The goal of this article is to develop a hybrid model that is both financially feasible and low in CO2. According to [93], the best economic outcome is a total leveling cost of 9.3 to 12.6 cents per kWh, with 43.9 percent coming from global production and renewable fuels. Fadaeenejad et al. used the iHOGA tool to make a hybrid model that involves two RES (SPV and WT) and two typical units (DG and batteries) for a tiny Malaysian community [94]. The RERL at the University of Massachusetts designed the Hybrid2 tools with an NREL grant. Mills et al. in Chicago use this tool to size a combined PV/wind/FC plant. The modelling for the fuel cell alternative [95] reveals that there is enough RE to cover the peak load.

“RET Screen”, a tool for projecting and evaluating energy infrastructure, analyses systems from a variety of perspectives, including technological, financial, ecological, and power efficiency [96]. P. Kumar et. al. used a Canadian modelling tool to analyze systems from a variety of perspectives, including technological, financial, ecological, and power efficiency, simulate model SPV, WT, DG, and a blended battery bank. The results reveal a 99% decrease in CO2 emissions [97], owing to the hybrid system’s reliance on renewable energy. Table 6 summarized the inlet and outlet attributes of each scaling tool as:

Table 6.

Sizing tool’s input and output [19,20,23,26,92,93,94,95,96,97].

The tool “TRNSYS” is largely used to model thermal systems [96]. Kumar et al., use this tool to make and model PV and thermic hybrid systems; the analysis reveals that hybrid solutions outperform SPV systems both economically and technologically [97].

The comparison of tools reveals various qualities and limits for each one, as shown in Table 7. The most significant points are picking the finest software depending on system usage and degree of size optimization, which means that RET Screen and HOMER can size any system using a simple optimization formula, with a 10 kW restriction, iHOGA may size any system, Solar GIS has less technical parameters and requires internet, and PV SOL has not supported an advanced sizing algorithm, TRNSYS & PV Syst cannot size all generators without optimization since Hybrid2 has certain inherent issues. RET Screen and HOMER are the best software package for sizing HRES, as per the outcomes of this evaluation.

Table 7.

Evolution of different scaling approaches (professional tools) used in hybrid system [1,19,26,92,93,94,95,96,97,98].

3.2. Traditional Approaches for Scaling HRES

Traditional sizing procedures are divided into four categories, such as: (1) analytical techniques, (2) iterative techniques, (3) probabilistic techniques, and (4) AI techniques, as explained below.

3.2.1. Analytical Techniques

The scale of the hybrid model is characterized by feasibility [99], which is depicted by a mathematical formula. In 2015, Madhlopa et al. published a study in South Africa that employed an analytical approach to build a hybrid model that included wind and solar generator elements. The purpose is to take steps to improve the hybrid system’s water efficiency. A hybrid core delivers 100 GWh/year, 0.97 €/kWh, and 75 km3/year, according to Figures [100].

3.2.2. Iterative Techniques

This approach is a recursive algorithm program that ends when the optimal system design is achieved [19,96]. Camargo et al. adopted this methodology to size a standalone hybrid model driven by SPV, WT, and batteries for supply to a Brazilian rural hamlet. The aim of this exercise is to establish a system which is both inexpensive and trustworthy. According to models, the optimum hybrid model architecture is 500 W of SPV, three WTs (600 W each), and five batteries (1200 Wh each). With a leveled cost of 1.044 R$/Wh [101], the total cost of this system is 25.6720 kR$.

3.2.3. Probabilistic Techniques

In probabilistic techniques to integrate system size [96], the impact of meteorological conditions, isolation, and oscillations on the proposed system is taken into account. Although this is one of the most widely used size approaches, the results show that it may not be the best option for obtaining the best result [19]. The P-PoPA method was used by Wen Hui Liu et al. to size SPV, WT, biomass, and batteries. The outcome suggests that strong storage capacity and power rating are increased while offshore electricity demand is lowered [102].

3.2.4. AI Techniques

In his review paper “A Study on Configurable, Control, and Scaling Approaches of HRES”, Upadhyay [103] stated, “AI is a phrase that in its widest meaning would represent the abilities of a tool or object to accomplish identical types of functions that describe human cognition”. The GA [104], MOSaDE [105], NSGA-II [106], MBA [107], PSO [108], MLUCA [101], ABSA [109], IFFA [110], A-Strong [111], BFA [112], ANN [74], FL [75], BBO [113], CS [76], DHS [114], SA-CS [85], ACO [115], and so on have all been used to discover the appropriate size for hybrid systems. Table 8 outlines the different size methodologies [17], together with their components of the system and target functions:

Table 8.

Recent studies on optimum sizing.

3.3. Evaluation of Various Sizing Techniques

Traditional methods are characterized by their ease of use and speed, yet these advantages restrict their performance and analysis. Because artificial intelligence uses multi-objective functions to tackle complicated problems, this flaw can be overlooked. This problem can be resolved through an iterative algorithm if the approach is based on a fundamental algorithm that engages in a cyclical process to build the best-sized configuration. Based on a basic numerical model, an analytical technique may quickly size up a hybrid system with limited functionality. However, this approach has the drawback of ignoring some important elements. For all difficult procedures, as compared to earlier approaches (analytical and iterative), AI is the best solution as it is endless and generates outstanding results. The complexity codes that are employed in this approach are the most difficult parts of the challenge. Table 9 compares the various hybrid system sizing methods.

Table 9.

Comparison of various scaling approaches (conventional approach) employed in hybrid systems [1,19,26,27,30].

4. HRES Control Mechanisms and Management Strategy

4.1. HRES Control Mechanisms

The following parameters should be monitored in any blended system: [120,121,122,123]:

- System stability refers to the system’s voltage and frequency.

- Protection entails keeping an eye on the power flow.

- Power balance refers to the allocation of loads in the most efficient way.

A variety of control systems for wind turbines have been proposed in the literature, including MPPT based on PSO [124], allocation of voltage vectors on the grid side converter relying on DPC [125], and pitch control employing a resilient sliding mode technique [126]. Several control strategies have been used to enhance solar panel effectiveness [127,128], including MPPT based on GRNN [129], deep learning neural network for solar photovoltaic prediction [130], and using MPPT in partially shadowed scenarios [131]. Voltage control [132], frequency control [133], and reactive power [134] have all been key research fields for DGs. Controlling hybrid renewable power systems may be achieved in a variety of ways, including centralized control [135], distributed control [136], and hybrid control [137], as well as RBC [138] and P-I control [139]. Classical techniques include neural network algorithms [140], FL controllers [141], multi-objective PSO [142], and ANFIS [143].

Because distributed or hybrid control is efficient in decentralizing control, minimizing system failure, and allowing the use of several forms of control in a single hybrid system, it is used in the majority of hybrid systems. The intricacy of the connection and processing codes is the only drawback to this sort of control. When used in a small size HRES, this type of control demonstrates high efficacy, better performance, and ease of building. Furthermore, as compared to dispersed or hybrid control, the cost of centralized control is lower. Until then, there is a good chance that the system will be entirely shut down if there is an issue with the generators or that maintenance will be scheduled. Table 10 highlights the key categories of control, as well as their benefits and drawbacks.

Table 10.

A comparison of the various control techniques [19,26,96,97].

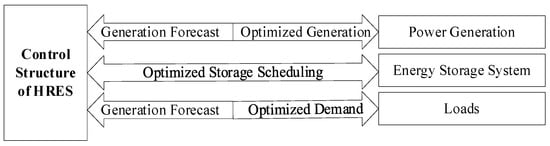

4.2. An HRES Management Strategy

Hybrid system management enables year-round system supply [22], a rise in element longevity, a reduction in economic parameters (global cost, leveling cost, etc.), and, as a consequence, system performance optimization (Figure 4). HRES management strategies are classified into three groups as shown in Figure 5 as:

Figure 4.

Intelligent energy flow structure.

Figure 5.

HRES management strategies.

4.2.1. Technological Goal-Oriented Strategy

The main objective of this approach is to take into account the technical parameters of hybrid systems in order to cover energy demands [144,145,146], enhance device lifespans [147], boost performance [148], boost stability of the system [149], boost storage network lifespans (BAT, FC, super capacity, etc.) [98], and many other parameters that characterize hybrid system power sources (Table 11). PMC [150], PSO [151], real-time optimization [152], ANN [153], and HOMER PRO [154] are some of the systems employed to regulate these parameters.

Table 11.

Management methods and its characteristics of hybrid system [99,155,156].

4.2.2. Economic Goal-Oriented Strategy

Any strategy that considers particular variables that impact the system’s economic situation, independent of its technological position (stability, system performance, and so on), is an economic objective strategy (Table 11) [99]. The model predictive control [154], GA [157], differential evolution algorithm [158], MILP [159], FL [160], interior search algorithm [161], commercial software such as HOMER [162], and so on are employed in significant published economic approach studies to achieve two fundamental objectives: coverage of demand and cost-cutting of the system.

4.2.3. Technological-Economic Goal-Oriented Strategy

This method for solving multi-objective functions is based on nonlinear optimization, and takes into account both technological and economic variables. This strategy has the benefit of improving technical characteristics such as component performance and lifespan while decreasing economic factors such as global cost (Table 11) [156]. Two of the most widely used approaches in this strategy are FL [163] and PSO [164]. This concept employs a variety of approaches, including a flow chart [165], an artificial electric field algorithm [166], evolutionary computational intelligence [167,168,169], and HOMER software [72]. Table 12 lists all of the management techniques.

Table 12.

Management methods review.

5. Challenges and Further Studies

Hybrid systems have long been seen as a viable grid-supply alternative. After it has been proven that oversizing increases system costs and inadequate power supply undersizing increases system costs, dimensioning, and optimization algorithms must successfully seek an acceptable mix of critically assessing elements such as system cost and efficiency.

- The authors used two basic methodologies are: Commercial software and conventional approaches, according to a recent study on HRES scaling. When the two approaches are compared, it becomes clear that commercial software is easier to use, more versatile in simulation, and faster, but it is limited by the use of unsophisticated optimization formulae. Conventional approaches can optimize the sizing field better than commercial tools, produce faster results, and address multi-objective problems, but they are difficult to use and complex to implement.

- Authors have been focusing on the three approaches: Traditional, next generation optimization, and hybrid methods, according to a survey of the literature. Conventional approaches in techno-economic analysis are characterized by speed and efficiency, with the disadvantage that the optimization area is limited. Because of its superior efficiency, accuracy, and faster convergence, new generation optimization methods are the most widely used in optimization; nevertheless, the downside of this strategy is that it necessitates the employment of specialized processing software.

- Hybrid approaches use the benefits of each approach to improve performance and minimize optimization processing time by combining the efficiency and speed of traditional methods with the accuracy and speed of next-generation optimization methods. Despite all of these benefits, the most significant disadvantages of hybrid approaches are the complexity of design and the difficulty of providing code.

- HRES control might be centralized, distributed, classical, or hybrid in nature. With distributed and hybrid control being the most popular due to their efficiency in controlling each generator individually, decreased system failure risk, increased system lifetime, and the ability to apply the most up-to-date control methods for each component individually. The most uncomfortable aspect of this control is the intricacy of connectivity inside the system or in program processing.

6. Conclusions

The research goals have an impact on how energy is managed in hybrid systems. Most researchers, for example, concentrate on techno-economic objectives because this type of analysis ensures both a technical (enhance life span, cover utilization, and boost performance) and an economical (mitigate the system cost and improve power cost) of HRES in order to achieve the best configuration. Many approaches are used to supervise HRES parts, including FL, PSO, ANN, and commercial software such as HOMER.

The importance of HRES for electrifying distant areas, feeding the main grid, conserving energy, reducing emissions, and lowering leveled energy costs was investigated in this research. Furthermore, the benefits and limitations of each strategy were reviewed, as well as the primary strategies for each axis (optimization, sizing, control, and management strategies). Following are the major conclusions:

- HRES may successfully fulfill energy demand in remote locations when optimized technically and economically (minimize investment cost or leveled cost) utilizing modern generation optimization techniques or commercial software.

- Traditional techniques to economic optimization are the most successful, but they have a limited number of optimization parameters. Due to the sophisticated procedure and codes utilized, the new generation optimization approach requires high hardware performance to function. The efficacy and speed of this strategy, as well as its precision, are its primary advantages. Integrating classical and new generation optimization approaches reveals a methodology with great speed and resilience, but it also necessitates advanced design and difficult code generation.

- The comparison of commercial software reveals various qualities and limits for each one, as shown in Table 7. The most significant points are picking the finest software depending on system usage and degree of size optimization. RET Screen and HOMER are the best software package for sizing HRES, as per the outcomes of this evaluation.

- Because distributed or hybrid control is efficient in decentralizing control, minimizing system failure, and allowing the use of several forms of control in a single hybrid system, it is used in the majority of hybrid systems. The intricacy of the connection and processing codes is the only drawback to this sort of control. When used in a small size HRES, this type of control demonstrates high efficacy, better performance, and ease of building. Furthermore, as compared to dispersed or hybrid control, the cost of centralized control is lower.

- To manage the HRES, techniques such as technological, economical, and techno-economical are used to reduce the entire system’s cost with the help of commercial software and other optimization techniques are reviewed.

- In order to obtain the best results in optimization, sizing, control, and management of an HRES, each research must employ a variety of approaches. On comparing numerous approaches, it ensures that the system performs well, and the objectives are fulfilled.

This review study will be helpful in navigating the difficulties and complexity involved in the investigation of HRES size, optimization, control, and management strategy. The detailed evaluation and comparative study, in this work will benefit industry, professionals, practicing engineers, and researchers for the understanding of an HRES.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; methodology, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; software, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; validation, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; formal analysis, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; investigation, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; resources, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; data curation, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; writing—review and editing, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; visualization, A.A.K., A.F.M., R.K.P. and H.M.; supervision, A.F.M.; project administration, H.M. and A.F.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from Intelligent Prognostic Private Limited Delhi, India Researcher’s Supporting Project (XX-02/2022) for conducting this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Johor Bahru 81310, Malaysia; the authors would like to acknowledge Integral University, Lucknow for providing the MCN: IU/R&D/2022-MCN0001472; and support from Intelligent Prognostic Private Limited Delhi, India Researcher’s Supporting Project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mathew, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Saha, S.; Mondal, S.; Haque, M.E. Sizing approaches for solar photovoltaic-based microgrids: A comprehensive review. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2022, 4, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minai, A.F.; Husain, M.A.; Naseem, M.; Khan, A.A. Electricity demand modeling techniques for hybrid solar PV system. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavadias, K.A. Stand-Alone, Hybrid Systems. In Comprehensive Renewable Energy; Sayigh, A., Kaldellis, J.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 623–656. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, S.; Chandel, S.S. Review of software tools for hybrid renewable energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.; Lee, K.T.; Lee, G.Y.; Chso, Y.M.; Ahn, S.H. Optimization of Hybrid Renewable Energy Power Systems: A Review. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2015, 2, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerdata, Global Energy Trends. Total Power Use. Available online: https://www.enerdata.net/publications/reports-presentations/world-energy-trends.html (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- OECD Publishing. International Energy Agency Global Energy Review 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://webstore.iea.org/download/direct/2995 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Exxon Mobil, 2017 Outlook for Power: A View to 2040. Available online: http://cdn.exxonmobil.com/~/media/global/files/outlook-for-power/2017/2017-outlookfor-power.pd (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Turcotte, D.; Ross, M.; Sheriffa, F. Photovoltaic Hybrid System Sizing and Simulation Tools: Status and Needs. In Proceedings of the PV Horizon: Workshop on Photovoltaic Hybrid Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10 September 2001; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A.S.R.; Gundersen, T.; Adams, T.A., II. Modeling and Simulation of Energy Systems: A Review. Processes 2018, 6, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuna, L.G.; Padilla, R.V.; Santander-Mercado, A.R. Measuring reliability of hybrid photovoltaic-wind energy systems: A new indicator. Renew. Energy 2017, 106, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Falahi, M.D.A.; Jayasinghe, S.D.G.; Enshaei, H. A review on recent size optimisation methodologies for standalone solar and wind hybrid renewable energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 143, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiprasad, N.; Kalam, A.; Zayegh, A. Comparative Study of Optimisation of HRES using HOMER and iHOGA Software. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2018, 77, 677–683. [Google Scholar]

- Kavadias, K.A.; Triantafyllou, P. Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems’ Optimisation. A Review and Extended Comparison of the Most-Used Software Tools. Energies 2021, 14, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Analysis of Hybrid Systems: Software Tools. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Information, Communication and Bio-Informatics (AEEICB16), Chennai, India, 27–28 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diaf, S.; Diaf, D.; Belhamel, M.; Haddadi, M.; Louche, A. A methodology for optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid PV/wind system. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 5708–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Lou, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, L.; Yang, H. Current status of research on optimum sizing of stand-alone hybrid solar–wind power generation systems. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belatrache, D.; Saifi, N.; Harrouz, A.; Bentouba, S. Modelling and numerical investigation of the thermal properties effect on the soil temperature in Adrar region, Algerian. J. Renew. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 2, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.A.; Pal, N.; Saeed, S.H. Review of solar photovoltaic and wind hybrid energy systems for sizing strategies optimization techniques and cost analysis methodologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaiah, R.; Saini, R.P. A review on planning, configurations, modeling and optimization techniques of hybrid renewable energy systems for offgrid applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoud, S.M.; Lin, X.; Okba, M.I. Hybrid renewable microgrid optimization techniques: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, F.J.; de Heras, A.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M. A review of energy management strategies for renewable hybrid energy systems with hydrogen backup. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 126–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezer, T.; Yaman, R.; Yaman, G. Evaluation of approaches used for optimization of stand-alone hybrid renewable energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, V.; Nema, S.; Baredar, P. Solar–wind hybrid renewable energy system: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, J. Modeling, planning, application and management of energy systems for isolated areas: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari, C.; Hamouda, M.; Makhloufi, S. Sizing and optimization for hybrid central in South Algeria based on three different generators. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2017, 6, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.L.V.; Gray, E.M.A. Optimization and integration of hybrid renewable energy hydrogen fuel cell energy systems—A critical review. Appl. Energy 2017, 202, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, M.; Hosseini, N.N. Optimizing Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems: A Review. In Sustainable Energy-Technological Issues, Applications and Case Studies; Zobaa, A.F., Afifi, S., Pisica, I., Eds.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; Chapter 8; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Tina, G.M.; Gagliano, S.; Raiti, S. Hybrid solar/wind power system probabilistic modelling for long-term performance assessment. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatod, D.K.; Pant, V.; Sharma, J. Analytical Approach for Well-Being Assessment of Small Autonomous Power Systems with Solar and Wind Energy Sources. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2010, 25, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, S. Optimised model for community-based hybrid energy system. Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedid, R.; Rahman, S. Unit sizing and control of hybrid wind-solar power systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1997, 12, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huneke, F.; Henkel, J.; González, J.A.B.; Erdmann, G. Optimisation of hybrid off-grid energy systems by linear programming. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2012, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.R.; Musgrove, L. The optimization of hybrid energy conversion systems using the dynamic programming model–Rapsody. Int. J. Energy Res. 1988, 12, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirtzis, A.G.; Gavanidou, E.S. Optimum operation of a small autonomous system with unconventional energy sources. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 1992, 23, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konak, A.; Coit, D.W.; Smith, A.E. Multi-objective optimization using genetic algorithms: A tutorial. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2006, 91, 992–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, M.; Wang, R.; Zha, Y.; Zhang, T. Multi-Objective Optimization of Hybrid Renewable Energy System Using an Enhanced Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm. Energies 2017, 10, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Bansal, R.C.; Singh, A.R.; Naidoo, R. Multi-objective optimization of hybrid renewable energy system using reformed electric system cascade analysis for islanding and grid connected modes of operation. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 47332–47354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramourtsis, A.C.; Bakirtzis, A.G.; Dokopoulos, P.S.; Gavanidou, E.S. Probabilistic evaluation of the performance of wind-diesel energy systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1994, 9, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaki, S.H.; Chedid, R.B.; Ramadan, R. Probabilistic Performance Assessment of Autonomous Solar-Wind Energy Conversion Systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1999, 14, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdougui, H.; Minciardi, R.; Ouammi, A.; Robba, M.; Sacile, R. Modelling and control of a hybrid renewable energy system to supply demand of a “Green” building. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 64, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.; Poudel, S.R.; Lee, K.-T.; Ahn, S.-H. Mathematical Modeling of Hybrid Renewable Energy System: A Review on Small Hydro-Solar-Wind Power Generation. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2014, 1, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Barakat, G.; Yassine, A. Deterministic Optimization and Cost Analysis of Hybrid PV/Wind/Battery/Diesel Power System. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2012, 2, 686–696. [Google Scholar]

- Borowy, B.S.; Salameh, Z.M. Methodology for Optimally Sizing the Combination of a Battery Bank and PV Array in a Wind/PV Hybrid System. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1996, 11, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markvart, T. Sizing of hybrid photovoltaic-wind energy systems. Sol. Energy 1996, 57, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.; Ferdowsi, M.; Shamsi, P.; Dagli, C.H. Modeling and Simulation of Microgrid. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 114, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharia, B.J.; Brahma, H.; Sarmah, N. A review of algorithms for control and optimization for energy management of hybrid renewable energy systems. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, V.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Geleta, D.K.; Manshahia, M.S. Artificial Bee Colony-Based Optimization of Hybrid Wind and Solar Renewable Energy System. In Handbook of Research on Energy-Saving Technologies for Environmentally-Friendly Agricultural Development; Kharchenko, V., Vasant, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; Chapter 9; pp. 429–453. [Google Scholar]

- Eltamaly, A.M.; Mohamed, M.A.; Al-Saud, M.S.; Alolah, A.I. Load management as a smart grid concept for sizing and designing of hybrid renewable energy systems. Eng. Optim. 2017, 49, 1813–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc, M. Particle Swarm Optimization; ISTE Ltd.: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, S.; Rutter, I.; Wagner, D.; Wagner, F. A Simulated-Annealing-Based Approach for Wind Farm Cabling. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Future Energy Systems, Shatin, Hong Kong, 16–19 May 2017; pp. 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Kwak, G.; Cho, K.; Huh, J. Wind farm layout optimization for wake effect uniformity. Energy 2019, 183, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdinc, O.; Uzunoglu, M. Optimum design of hybrid renewable energy systems: Overview of different approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, Y.; Xiang, J. Optimal Sizing of a Stand-Alone Hybrid Power System Based on Battery/Hydrogen with an Improved Ant Colony Optimization. Energies 2016, 9, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhane, P.; Rangnekar, S.; Mittal, A. Optimal Sizing of Hybrid Energy System using Ant Colony Optimization. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2014, 4, 683–688. [Google Scholar]

- Minai, A.F.; Usmani, T.; Iqbal, A.; Mallick, M.A. Artificial Bee Colony Based Solar PV System with Z-Source Multilevel Inverter. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication & Materials (ICACCM), Dehradun, India, 21–22 August 2020; pp. 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Savsani, V.J.; Vakharia, D.P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput. Aided Des. 2011, 43, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Optimization of solar systems using artificial neural-networks and genetic algorithms. Appl. Energy 2004, 77, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, M.; Pellegrino, D. Mathematical optimization of a RES-H2 plant using a black box algorithm. Renew. Energy 2005, 30, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wei, W.; Xiang, J. A Simple Sizing Algorithm for Stand-Alone PV/Wind/Battery Hybrid Microgrids. Energies 2012, 5, 5307–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.R.; Natarajan, E. Optimization of integrated photovoltaic–wind power generation systems with battery storage. Energy 2006, 31, 1943–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, S.M.; Tafreshi, S.M.M.; Rajati, M.R. Unit Sizing of a Stand-Alone Hybrid Power System Using Model-Free Optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Granular Computing, San Jose, CA, USA, 2–4 November 2007; pp. 751–756. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Chen, H.C. A mathematical technique for hybrid power system design with energy loss considerations. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 82, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedid, R.; Akiki, H.; Rahman, S. A decision support technique for the design of hybrid solar–wind power systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1998, 13, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoji, S.K.; Rath, B.B.; Kumar, D.V. Optimization of Hybrid PV Wind Energy System Using Genetic Algorithm (GA). Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2014, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Paulitschke, M.; Bocklisch, T.; Böttiger, M. Comparison of particle swarm and genetic algorithm based design algorithms for PV-hybrid systems with battery and hydrogen storage path. Energy Proc. 2017, 135, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, K.; Alam, M.A.; Minai, A.F. Optimization of Solar Energy Using ANN Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Power Energy, Environment and Intelligent Control (PEEIC), Greater Noida, India, 18–19 October 2019; pp. 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minai, A.F.; Usmani, T.; Uz Zaman, S.; Minai, A.K. Intelligent Tools and Techniques for Data Analytics of SPV Systems: An Experimental Case Study. In Intelligent Data Analytics for Power and Energy Systems; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Malik, H., Ahmad, M.W., Kothari, D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirtharaj, S.; Premalatha, L.; Gopinath, D. Optimal utilization of renew- able energy sources in MG connected system with integrated converters: An AGONN Approach. Analog. Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2019, 101, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrouazin, A.; Aillerie, M.; Mekkakia-Maaza, N.; Charles, J.-P. Multi input-output fuzzy logic smart controller for a residential hybrid solar-wind- storage energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 148, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odou, O.D.T.; Bhandari, R.; Adamou, R. Hybrid off-grid renewable power system for sustainable rural electrification in Benin. Renew. Energy 2019, 145, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, B.O.; Nourou, D.; Kébé, C.M.F.; Sambou, V.; Ndiaye, P.A.; Ndongo, M. Multiobjective optimization of hybrid PV/wind/diesel/battery systems for decentralized application by minimizing the levelized cost of energy and the CO2 emissions. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2015, 10, 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Maleki, A.; Rosen, M.A.; Liu, J. Sizing a stand-alone solar-wind-hydrogen energy system using weather forecasting and a hybrid search optimization algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 180, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallanza, A.; Porretto, M.; Puma, G.L.; Marannano, G. A sizing approach for stand- alone hybrid photovoltaic-wind-battery systems: A Sicilian case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanajaoba, S.; Fernandez, E. Maiden application of Cuckoo Search algorithm for optimal sizing of a remote hybrid renewable energy System. Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhai, R.; Fu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.G. Optimization study of thermal-storage PV-CSP integrated system based on GA-PSO algorithm. Sol. Energy 2019, 184, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Pourfayaz, F. Optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid photovoltaic/wind/battery power system with LPSP technology by using evolutionary algorithms. Sol. Energy 2015, 115, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshsari, A.; Ghiamy, M.; Mousavi, M.M.M.; Bagal, H.A. Optimal design of hybrid water–wind–solar system based on hydrogen storage and evaluation of reliability index of system using ant colony algorithm. Int. Res. J. Appl. Basic Sci. 2013, 4, 3582–3600. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi, M.; Askarzadeh, A. Techno-economic analysis and size optimization of an off-grid hybrid photovoltaic, fuel cell and diesel generator system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 44, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahboune, H.; Zouggar, S.; Krajacic, G.; SabevVarbanov, P.; Elhafyani, M.; Ziani, E. Optimal hybrid renewable energy design in autonomous system using Modified Electric System Cascade Analysis and Homer software. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 126, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, M. Dynamic behavior of a stand-alone hybrid power generation system of wind turbine, micro-turbine, solar array and battery storage. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 3051–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Maleki, A.; Rosen, M.A.; Azarikhah, P. Optimization of a hybrid system for solar-wind-based water desalination by reverse osmosis: Comparison of approaches. Desalination 2018, 442, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdeli, N. Optimal management of hybrid PV/fuel cell/battery power system: A comparison of optimal hybrid approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, B.; Maleki, A.; Zhang, W. Simulated annealing-chaotic search algorithm based optimization of reverse osmosis hybrid desalination system driven by wind and solar energies. Sol. Energy 2018, 173, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Maleki, A.; Rosen, M.A.; Liu, J. Optimization with a simulated annealing algorithm of a hybrid system for renewable energy including battery and hydrogen storage. Energy 2018, 163, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Myhren, J.A.; Han, M.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y. Techno-economic analysis of a solar photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) concentrator for building application in Sweden using Monte Carlo method. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 165, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, N.; Kasaeian, A.; Toopshekan, A.; Bahrami, L.; Maghami, A. Optimizing a hybrid wind-PV-battery system using GA-PSO and MOPSO for reducing cost and increasing reliability. Energy 2018, 154, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Garcia, D.A.; Keynia, F.; Bisegna, F.; de Santoli, L. A novel composite neural network based method for wind and solar power forecasting in microgrids. Appl. Energy 2019, 251, 113353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, A.A.; Hatata, A.Y.; Aldl, M.M. Optimal sizing of hybrid renewable energy system via artificial immune system under frequency stability constraints. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 015905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrich, M.; Mohammed, O.H.; Kamel, S.; Selim, A.; Sultan, H.M.; Akherraz, M.; Jurado, F. Development and implementation of a novel optimization algorithm for re- liable and economic grid-independent hybrid power system. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Xue, X.; Liu, G. Techno-economic evaluation for hybrid renewable energy system: Application and merits. Energy 2018, 159, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneshi, M.; Hadianfard, F. Techno-economic feasibility of hybrid diesel/PV/wind/battery electricity generation systems for non-residential large electricity consumers under southern Iran climate conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 127, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewfik, T.M.; Badr, M.A.; El-Kady, E.Y.; Latif, O.E.A. Optimization and energy management of hybrid standalone energy system: A case study. Renew. Energy Focus 2018, 25, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Al-Hallaj, S. Simulation of hydrogen-based hybrid systems using Hybrid2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2004, 29, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, T.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Mohamed, A. A review on sizing methodologies of photovoltaic array and storage battery in a standalone photovoltaic system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 120, 430–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Deokar, S. Designing and Simulation Tools of Renewable Energy Systems: Review Literature. In Progress in Advanced Computing and Intelligent Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, P.; Braccia, L.; Luppi, P.; Zumoffen, D.; Feroldi, D. Integration of sizing and energy management based on economic predictive control for standalone hybrid renewable energy systems. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, A.; Sandhu, K.S. Hybrid wind/photovoltaic energy system developments: Critical review and findings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhlopa, A.; Sparks, D.; Keen, S.; Moorlach, M.; Krog, P. TDlamini, Optimization of a PV–wind hybrid system under limited water resources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.E.C.; Vidotto, M.L.; Niedzialkoski, R.K.; de Souza, S.N.M.; Chaves, L.I.; Edwiges, T.; Werncke, I. Sizing and simulation of a photovoltaic-wind energy system using batteries, applied for a small rural property located in the south of Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, W.; Rafidah, S.; Alwi, W.; Hashim, H.; Shiun, J.; Erniza, N.; Shin, W. Sizing of Hybrid Power System with varying current type using numerical probabilistic approach. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Sharma, M.P. A review on configurations, control and sizing methodologies of hybrid energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, A.R.; Cardemil, J.M.; Escobar, R.; Colle, S. Multi-objective optimization of hybrid CSP + PV system using genetic algorithm. Energy 2018, 147, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, M.A.M.; Bouchekara, H.R.E.H.; Alghamdi, A.S. Optimal Sizing of PV/wind/diesel hybrid microgrid system using multi-objective self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm. Renew. Energy 2018, 121, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamjoo, A.; Maheri, A.; Dizqah, A.M.; Putrus, G.A. Multi-objective design under uncertainties of hybrid renewable energy system using NSGA-II and chance con-strained programming. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 74, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A. A reliable methodology based on mine blast optimization algorithm for optimal sizing of hybrid PV-wind-FC system for remote area in Egypt. Renew. Energy 2016, 95, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarzadeh, A.; dos Coelho, L.S. A novel framework for optimization of a grid independent hybrid renewable energy system: A case study of Iran. Sol. Energy 2015, 112, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Askarzadeh, A. Artificial bee swarm optimization for optimum sizing of a stand-alone PV/WT/FC hybrid system considering LPSP concept. Sol. Energy 2014, 107, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yuan, X. Multi-objective optimization of stand-alone hybrid PV-wind-diesel-battery system using improved fruit fly optimization algorithm. Soft Comput. 2016, 20, 2841–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H.; Lin, G. Optimal design of hybrid renewable energy systems using simulation optimization. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2015, 52, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, B.K.; Pandi, V.R.; Sharma, R.; Das, S.; Das, S. Multiobjective bacteria for- aging algorithm for electrical load dispatch problem. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A. BBO-based small autonomous hybrid power sys- tem optimization incorporating wind speed and solar radiation forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangqian, D.; Bekhrad, K.; Azarikhah, P.; Maleki, A. A hybrid algorithm based optimization on modeling of grid independent biodiesel-based hybrid solar/wind systems. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhane, P.; Rangnekar, S.; Mittal, A.; Khare, A. Sizing and performance analysis of standalone wind-photovoltaic based hybrid energy system using ant colony optimization. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2016, 10, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Wang, H. Real time energy management and control strategy for micro-grid based on deep learning adaptive dynamic programming. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, A.L.; Tan, C.W.; Lau, K.Y. Optimal sizing of an autonomous photovoltaic/wind/battery/diesel generator microgrid using grasshopper optimization algorithm. Sol. Energy 2019, 188, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, A.; Sandhu, K.S. Optimal Sizing of a Grid-Connected PV/Wind/Battery System Using Particle Swarm Optimization. Iran J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2019, 43, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, F.S.; Diab, A.A.Z.; Ali, Z.M.; El-Sayed, A.H.M.; Alquthami, T.; Ahmed, M.; Ramadan, H.A. Optimal sizing of smart hybrid renewable energy system using different optimization algorithms. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4935–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, J.; Mwasilu, F.; Lee, J.; Jung, J.W. AC-microgrids versus DC-microgrids with distributed energy resources: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidram, A.; Davoudi, A. Hierarchical structure of microgrids control system. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2012, 3, 1963–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.E.; Mehrizi-Sani, A.; Etemadi, A.H.; Cañizares, C.A.; Iravani, R.; Kazerani, M.; Jiménez-Estévez, G.A. Trends in microgrid control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, R.; Srivastava, A.K. Controls for microgrids with storage: Review, challenges, and research needs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2009–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitharthan, R.; Karthikeyan, M.; Sundar, D.; Rajasekaran, S. Adaptive hybrid intelligent MPPT controller to approximate effectual wind speed and optimal rotor speed of variable speed wind turbine. ISA Trans. 2019, 96, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-González, W.; Montoya, O.D.; Garces, A. Direct power control for VSC-HVDC systems: An application of the global tracking passivity-based PI approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 110, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L.; Corradini, M.L.; Ippoliti, G.; Orlando, G. Pitch angle control of a wind turbine operating above the rated wind speed: A sliding mode control approach. ISA Trans. 2020, 96, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, K.; Minai, A.F.; Malik, H. Intelligent Approach-Based Maximum Power Point Tracking for Renewable Energy System: A Review. In Intelligent Data Analytics for Power and Energy Systems; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Malik, H., Ahmad, M.W., Kothari, D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.; Husain, M.A.; Minai, A.F.; Khan, A.N.; Amir, M.; Dinesh Kumar, J.; Iqbal, A. Assessment of Meta-Heuristic and Classical Methods for GMPPT of PV System. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2021, 22, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.F.; Ling, Q.; Javed, M.Y.; Mansoor, M. Novel MPPT techniques for photovoltaic systems under uniform irradiance and Partial shading. Sol. Energy 2019, 184, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qi, X.; Liu, H. A comparison of day-ahead photovoltaic power forecasting models based on deep learning neural network. Appl. Energy 2019, 251, 113315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoud, A. MPPT controller for PV array under partially shaded condition, Algerian. J. Renew. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2019, 1, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Haseltalab, A.; Botto, M.A.; Negenborn, R.R. Model predictive DC volt- age control for all-electric ships. Control Eng. Pract. 2019, 90, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.-S.; Baek, E.-R.; Jeon, B.-G.; Chang, S.-J.; Park, D.-U. Seismic performance of emergency diesel generator for high frequency motions. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2019, 51, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrjerdi, H.; Hemmati, R.; Farrokhi, E. Nonlinear stochastic modeling for optimal dispatch of distributed energy resources in active distribution grids including reactive power. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2019, 94, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasetsky, D.; Sidorov, D.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Xiong, J.; He, L. Centralized emergency control for multi-terminal VSC-based shipboard power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 104, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M.; Zarif, M.H. A novel two-stage distributed structure for reactive power control. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2020, 23, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaladi, K.K.; Sandhu, K.S. Real-Time Simulator based hybrid control of DFIG-WES. ISA Trans. 2019, 93, 9325–9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakui, T.; Sawada, K.; Yokoyama, R.; Aki, H. Predictive management for energy supply networks using photovoltaics, heat pumps, and battery by two-stage stochastic programming and rule-based control. Energy 2019, 179, 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Safdarnejad, S.M.; Powell, K.M. Dynamic simulation, control, and performance evaluation of a synergistic solar and natural gas hybrid power plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 179, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingamuthu, R.; Mariappan, R. Power flow control of grid connected hybrid renew- able energy system using hybrid controller with pumped storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 3790–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, M.; Mahmodi, E.; Mousavi, M.; Chaharmahali, I. A novel Fuzzy PI controller for improving autonomous network by considering uncertainty. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2019, 18, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, M. Detailed study, multi-objective optimization, and design of an AC-DC smart microgrid with hybrid renewable energy resources. Energy 2019, 169, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Kassem, A.M. Antlion optimizer-ANFIS load frequency control for multi-interconnected plants comprising photovoltaic and wind turbine. ISA Trans. 2018, 87, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, W. Multi-stage active management of renewable-rich power distribution network to promote the renewable energy consumption and mitigate the system uncertainty. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 111, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forough, A.B.; Roshandel, R. Lifetime optimization framework for a hybrid renewable energy system based on receding horizon optimization. Energy 2018, 150, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Minai, A.F.; Khan, A.A.; Kumar, S. IoT Based Energy Management System for Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication & Materials (ICACCM), Dehradun, India, 21–22 August 2020; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukuri, S.H.C.; Saravanan, B.; Arunkumar, G. Experimental evaluation of the performance of virtual storage units in hybrid micro grids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 114, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonkile, M.P.; Ramadesigan, V. Power management control strategy using physics-based battery models in standalone PV-battery hybrid systems. J. Energy Storage 2019, 23, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmadakis, I.; Elmasides, C. Towards performance enhancement of hybrid power supply systems based on renewable energy sources. Energy Proc. 2019, 157, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.L.V.; Gray, E.M. Optimization of renewable hybrid energy systems—A multi-objective approach. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 971–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Menghwar, M.; Asghar, E.; Panjwani, M.K.; Liu, Y. Real-time energy management for a smart-community microgrid with battery swapping and renewables. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Loy-Benitez, J.; Nam, K.; Hwangbo, S.; Rashidi, J.; Yoo, C. Sustainable and reliable design of reverse osmosis desalination with hybrid renewable energy systems through supply chain forecasting using recurrent neural networks. Energy 2019, 178, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, I.; Avila, D.; Marichal, G.N.; Rodríguez, J.A. Assessment of hybrid renewable energy systems to supplied energy to autonomous desalination systems in two islands of the canary archipelago. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, M.; Mancuso, G.M.; Riccardi, J.; Cantù, M.; Pannocchia, G. A sequential linear programming algorithm for economic optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems. J. Process. Control 2017, 74, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Busaidi, A.S.; Kazem, H.A.; Al-Badi, A.H.; Farooq Khan, M. A review of optimum sizing of hybrid PV–Wind renewable energy systems in Oman. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Yan, X.; Li, Q.; Long, T. A design and experimental investigation of a large-scale solar energy/diesel generator powered hybrid ship. Energy 2018, 165, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, H.; Khorshidi, J. Exergoeconomic analysis and optimization of a solar based multigeneration system using multiobjective differential evolution algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Hou, B. A hybrid algorithm for mixed integer nonlinear programming in residential energy management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, M.H.; Ardehali, M.M. Operational performance of energy storage as function of electricity prices for on-grid hybrid renewable energy system by optimized fuzzy logic controller. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouholamini, M.; Mohammadian, M. Heuristic-based power management of a grid–connected hybrid energy system combined with hydrogen storage. Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muh, E.; Tabet, F. Comparative analysis of hybrid renewable energy systems for off-grid applications in Southern Cameroons. Renew. Energy 2018, 134, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowdeh, S.A.; Davoodkhani, I.F.; Moghaddam, M.J.H.; Najmi, E.S.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Ahmadi, A.; Gandoman, F.H. Fuzzy multi-objective placement of renewable energy sources in distribution system with objective of loss reduction and reliability improvement using a novel hybrid method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 77, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Triviño, P.; Fernández-Ramírez, L.M.; Gil-Mena, A.J.; Llorens-Iborra, F.; García-Vázquez, C.A.; Jurado, F. Optimized operation combining costs, efficiency and lifetime of a hybrid renewable energy system with energy storage by battery and hydrogen in grid-connected applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 23132–23144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, L.; Pino, F.J.; Guerra, J.; Rosa, F. Definition, analysis and experimental investigation of operation modes in hydrogen-renewable-based power plants incorporating hybrid energy storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 113, 290–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]