Abstract

The present research is focused on an experimental investigation to evaluate the mechanical, durability, and thermal performance of compressed earth blocks (CEBs) produced in Portugal. CEBs were analysed in terms of electrical resistivity, ultrasonic pulse velocity, compressive strength, total water absorption, water absorption by capillarity, accelerated erosion test, and thermal transmittance evaluated in a guarded hotbox setup apparatus. Overall, the results showed that compressed earth blocks presented good mechanical and durability properties. Still, they had some issues in terms of porosity due to the particle size distribution of soil used for their production. The compressive strength value obtained was 9 MPa, which is considerably higher than the minimum requirements for compressed earth blocks. Moreover, they presented a heat transfer coefficient of 2.66 W/(m2·K). This heat transfer coefficient means that this type of masonry unit cannot be used in the building envelope without an additional thermal insulation layer but shows that they are suitable to be used in partition walls. Although CEBs have promising characteristics when compared to conventional bricks, results also showed that their proprieties could even be improved if optimisation of the soil mixture is implemented.

1. Introduction

Earth has been used as a building material since ancient times in several different ways around the world [1,2,3,4]. Industrialised building systems and the dissemination of materials, like concrete [5], have replaced earthen construction. Today, earthen construction is associated with poverty [2], and most of this type of construction is located in developing countries. The continuous increase in the energy cost of some building materials (cement and ceramic bricks) and environmental issues are promoting the use of sustainable materials, such as the earthen materials known by their abundance and low-cost production [5,6,7].

Compressed earth blocks (CEBs) are one of the most widespread earthen building techniques. They represent a modern descendent of the moulded earth block, commonly called as the adobe block [7]. The compaction of earth improves the quality and performance of the blocks [4] but also promotes several environmental, social, and economic benefits [8,9]. Regarding the environmental advantages of using earthen products, a previous study showed that in a cradle-to-gate analysis of different walls, the use of earthen building elements could result in reducing the potential environmental impacts by about 50% when compared to the use of conventional building elements [2].

Earthen construction is known to undergo rapid deterioration under severe weather conditions [10]. If not built adequately, earthen buildings have lower durability and are more vulnerable to extreme weather conditions and rainfall than conventional buildings. This situation means higher maintenance and repair costs during the life cycle of a building [11].

In the last few years, there has been increasing interest in overcoming the mechanical and durability issues related to earthen blocks. Different stabilisation techniques were used to improve durability and compressive strength [6,11,12,13]. Dynamic compaction alone or together with chemical stabilisation using several additives has been shown to considerable improve the mechanical performance of CEBs [10,13]. In contrast, compaction increases thermal conductivity [14]. The stabilisation process of raw earth refers to any mechanical, physical, physicochemical, or combined methods that enhance its properties [10]. Bahar et al. [15] studied the effect of several stabilisation methods on mechanical properties. The results showed that the combination of compaction and cement stabilisation is an effective solution for increasing the strength of earth blocks. Amoudi et al. [16,17] developed an experimental program to study the mechanical properties of cement-stabilised earth blocks. They verified that cement in the presence of water forms hydrated products that occupy the voids and wrap the soil particles. That process leads to an improvement in compressive strength, water absorption, dimensional stability, and durability. In many countries, CEBs are stabilised with cement or lime, and there are successful examples of their use in the construction of buildings. Several studies highlighted their lower construction cost, simpler construction processes, and the contribution of this material to maintaining a better indoor environment quality when comparing to the use of conventional building materials [8,11,18,19,20]. Besides that, some studies show that the addition of lime to compressed earth blocks can improve their mechanical and hydrous properties [21,22].

Regarding the thermal proprieties of earthen building products, since they are massive, they contribute to increasing the thermal inertia of the buildings. This feature can have a positive influence on the thermal performance of buildings in certain climates. A previous study showed that in locations with hot summers and temperate winters, such as the Mediterranean areas, earthen construction could provide comfortable indoor temperature by passive means alone [23]. This property can reduce heating and cooling energy needs and therefore contribute to lower life cycle environmental and financial costs. Nevertheless, compared to the number of studies focusing on mechanical properties, there are fewer studies related to the thermal properties of compressed earth blocks [11]. Adam and Jones [24] measured the thermal conductivity of lime and cement stabilised hollow and massive earth blocks using a guarded hot box method. The authors verified that the thermal conductivity was higher on stabilised blocks (0.20 W/m2·K and 0.50 W/m2·K). The compressive strength used in the compaction of the blocks, the type of soil, and the additives used can significatively influence the thermal conductivity of a CEB building element [24]. For that reason, in the literature, it is possible to find very different thermal conductivity values for earthen products. For example, according to the Portuguese thermal regulation [25], the thermal conductivity to consider for adobe, rammed earth, and compressed earth blocks is 1.10 W/(m2·K). At the same time, other studies show quite different values, also depending on the considered earthen building technique—earth materials with fibres (0.42–0.90 W/(m2·K)), adobe (0.46–0.81 W/(m2·K)), or rammed earth (0.35–0.70 W/(m2·K)) [1,26].

When designing a sustainable building, the design team must have comprehensive information regarding the different building products they can use [19]. Information should include that related to the life cycle environmental (e.g., embodied energy and global warming potential), functional (e.g., mechanical and thermal) and economic (e.g., construction and maintenance cost) performances.

Based on this context, this research is within a series of studies that are being developed by the same authors to develop comprehensive information about earthen construction. Past studies include those related to analysing the contribution of this type of construction in improving the indoor environmental quality [23] and reducing the embodied environmental impacts [2].

The present research is focused on an experimental investigation to evaluate the mechanical, durability and thermal performances of compressed earth blocks produced by a Portuguese company. This study aims to analyse the functional quality of the abovementioned product and assess its potential to be used in the construction of buildings.

2. Materials and Methods

The compressed earth blocks tested are a commercial product made by a manufacturer located in the city of Serpa, district of Beja (southern Portugal), which is also a contractor that builds earthen and conventional buildings. This contractor is one of the leading earth building systems builders in Portugal. The share of the earthen building systems corresponds to around 12% of the total company’s activity, and during the year 2014, the company produced 338 m3 of rammed earth and 36 m3 of compressed earth blocks. Usually, rammed earth is used to build 60-cm-thick walls, and the dimensions of the CEBs produced by this company varies. In this work, 30 cm × 15 cm × 7 cm compressed earth blocks were studied, since it is the most common block produced by the company. Additionally, this size is the most used in the Portuguese construction. The soil mixture is stabilised by using 6% by weight (wt) of hydraulic lime and 1% wt of hydrated lime. The mix also uses water, generally extracted on-site (groundwater) (10% by weight), which evaporates during the drying process. In the majority of cases, earthen building elements are built from soil extracted from the construction site. Additionally, according to the company’s data, the compressed earth blocks are made and compacted using a mechanical tapping machine. The company provided compressed earth blocks and the soil used for their production. They were experimentally analysed in different labs of the Department of Civil Engineering of the University of Minho, located in the city of Guimarães, district of Braga (northern Portugal).

2.1. Soil Characterisation

The soil was characterised in terms of particle size distribution, sand equivalent, clay content, cohesion limits, and compaction properties. These properties evaluate the quality of soil to be used in earthen construction. The particle size distribution was determined according to the EN 196:1966 standard [27]. The main goal of the sand equivalent test is to estimate the percentage of sand that exist in a soil fraction with particles with less than 2 mm. This test was done according to EN 933-8:2002 [28]. The methylene blue test allows the quantification of clay content present in a soil sample through the ionic change between the cations that exist in the soil particles and was done according to EN 933-9:2002 [29]. The cohesion limits of soil are fundamental for the final quality of CEBs. The main goal of this test is assessing the liquid limit (LL), the plastic limit (LP), and the index of plasticity (IP) of the soil. The cohesion limits were determined and calculated according to the EN 143:1969 standard [30].

The compaction properties of soil are fundamental in earthen products since there is a direct relation between dry density and compressive strength of a product. A more compact product presents higher strength. The main goal of the Proctor compaction test consists in analysing the optimum water content. This water content corresponds to the water content of a soil that allows it to achieve its dry density for specific energy of compaction. This test was done according to LNEC E 197:1966 standard [31], considering two types of compaction (light and hard) in a small mould.

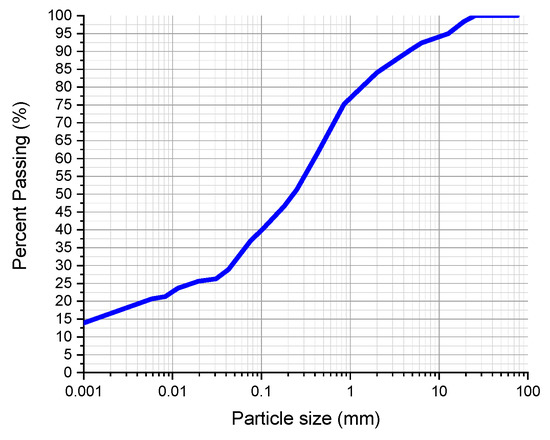

Table 1 and Figure 1 summarise the characteristics of the soil used for CEBs production. The soil presented a good particle size distribution and showed the four types of particles in significant percentages (15.9% pebble, 47.2% sand, 17.6% silt, and 19.4% clay). As shown in Table 1, the soil has a liquid limit of 29% and a plasticity index of 11%. Therefore, it can be classified as a fair to poor clayed soil (type A6) according to the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) system [32]. However, according to the CRATerre group [33], these figures are within the limits of the recommended classes for soil to be used as a construction material. The methylene blue test shows 2.28 g of methylene blue per 100 g of soil, indicating a low degree of expansion, as also confirmed by the plasticity index, suggesting a low clay content in the studied soil [34]. This result is good since expansive soils are affected by humidity variations that change its consistency [35]. The analysed soil has a maximum dry density between 1.95 g/cm3 and 1.99 g/cm3, which means that this soil is classified as “very good” to be used as construction material [33].

Table 1.

Particle size distribution and Atterberg limits of the soil used.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution of the soil, according to the results of the sedimentation test.

2.2. Compressed Earth Blocks Characterisation

2.2.1. Electrical Resistivity

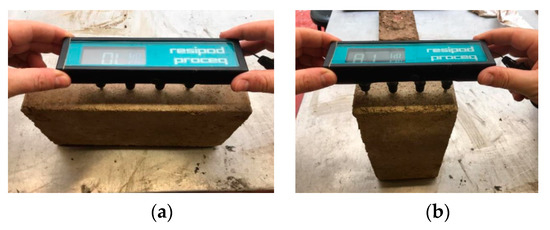

The electrical resistivity was measured using the ResipodProceq equipment, made by Proceq SA (Schwerzenbach, Switzerland), which comprises four equidistant (38 mm) electrodes (Figure 2). During this test, an alternate current was provided between the external electrodes and the electrical potential difference between the internal electrodes was measured. The electrical resistivity was measured through the Ohm’s law and computed by the equipment used. The tested samples were the ones used for the water absorption by capillarity test after they achieved the saturation point. Four measurements were done for each saturated compressed earth block sample.

Figure 2.

Electric resistivity test: measurements were done in two samples faces—(a) width and (b) length.

2.2.2. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity

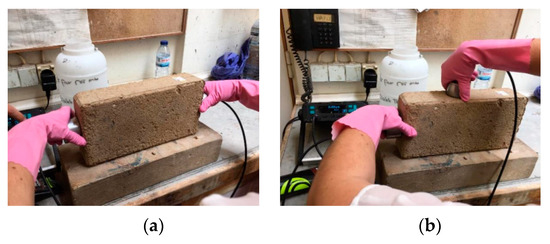

The Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) test evaluates some materials properties, such as elasticity modulus, homogeneity, mechanical resistances, and cracking. It is also possible to calculate the propagation velocity [36]. The UPV tests consists of measuring the time that a given sound pulse takes to pass through a known section of a specimen. This is based on the wave propagation theory, where a sound pulse propagates faster in a dense material and slowly in a porous material. It is therefore possible to calculate the propagation velocity [36], and this test allows the indirect determination of the intrinsic characteristics of a given sample [36]. There is almost nothing in the literature about the use of this test in compressed earth blocks. Nevertheless, there are some studies that have already been performed on rammed earth [37,38] that disclose that there is a relation between the UPV and the compressive strength of earthen products. The UPV measurement was developed according to EN 12504-4:2007 [39] in two directions (direct and indirect—see Figure 3). The measure of UPV in the direct position was obtained with the transmitter and receiver transducers positioned on two opposite sides. The indirect measurements were done by placing the transmitter on one face and the receiver on a perpendicular side. An appropriate coupling gel was applied between the transducers and the sample to prevent the existence of voids in the contact area. Three independent readings were registered for each sample. Equation (1) is used to calculate the UPV, which is the ratio between the distance (L) between the transductors (emission and receptor) and the propagation time (t).

Figure 3.

Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) test—(a) direct method and (b) indirect method.

2.2.3. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength test used a hydraulic press machine with a capacity of 3000 kN (Figure 4), coupled with a hydraulic control system, according to NP EN 772-1 [40]. For the test, two transducers were used, one that belongs to the press and another external to measure the vertical displacement (LVSTs). The test used displacement control, with a regular load velocity of 0.5 kN/s. The experiment consisted of applying an increasing compressive load until the load achieved 40% to 50% of the failure value after registering the maximum load peak. Six samples were tested to assess the compressive strength of CEBs.

Figure 4.

Compressive strength test.

2.2.4. Total Water Absorption

The assessment of the total water absorption of a block is essential since it can be used for routine quality checks, classification according to required durability and structural use, and to estimate the volume of voids [4,41]. Usually, the less water a block absorbs and retains, the better its structural performance and durability. Reducing the total water absorption capacity of a block has often been considered as one way of improving its quality [41].

The total water absorption test consists of immersing a block in the water until no further increase in apparent mass is observed. This experiment followed the LNEC E 394:1993 standard [42]. It is considered that there was no increase in the apparent mass when two consecutive measurements did not differ by more than 0.1% by mass. The test was carried out at atmospheric pressure in which three samples were immersed in water for 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h. After each period, the surface of the specimen was wiped with a cloth to remove any adsorbed water. Then the samples were weighed. Initially, the test was done for 24 h, as recommended by the standard and observed in other studies [4,41]. However, after 24 h immersion in water, the CEBs disintegrated, and it was not possible to measure its wet weight. The percentage of water absorbed (A) was calculated using Equation (2). Wh is the weight of the specimen after each period of immersion, and Ws is the dry block weight.

2.2.5. Water Absorption by Capillarity

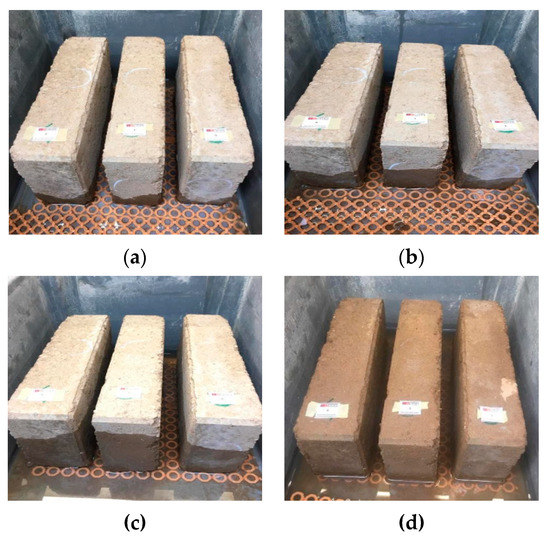

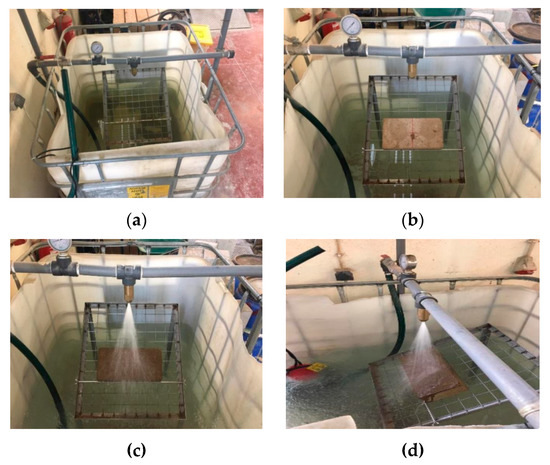

This test consists of quantifying the amount of water absorbed by capillarity in the compressed earth block. The experiment was performed in three entire blocks following the LNEC E 393:1993 standard [43]. This is a Portuguese standard for analysing the water absorption in concrete, and it was used since the procedure is similar to the international standards specific for earthen products [10,40,44]. Before being immersed, each specimen dried for 14 days in an oven at a controlled temperature of 60 ± 5 °C. In the following step, each sample was weighed with a precision of 0.1 g, and then its lower face was immersed in a 5 mm water bath. Samples were left in the bath for 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min, and 2, 3, 4, 6, 24, and 72 h, to identify the water saturation point (Figure 5). The water absorption by capillarity coefficient, Cb, was calculated for 10 min, according to UNE 41410:2008 [44] and using Equation (3).

where

Figure 5.

Water absorption by capillarity test: (a) after 10 min of water immersion; (b) after 30 min of water immersion; (c) after 45 min of water immersion; and (d) after 60 min of water immersion.

- Cb is the water absorption by capillarity coefficient (g/cm2·min0.5);

- M1 is the weight of the block after immersion in water (g);

- M0 is the weight of the block before immersion in water (g);

- S is the immersed area (cm2);

- t is the immersion time (min).

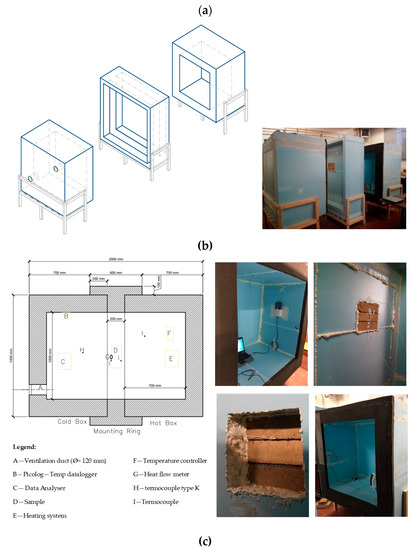

2.2.6. Accelerated Erosion

This test analyses the degradation process of a specimen caused by water falling on it. This experiment verifies the surface resistance to erosion, thus evaluating the durability of the analysed blocks. The test was performed according to NZS 4298:1998 [39], and a rain simulator was used (Figure 6). The climate parameters used were the ones for Penhas Douradas region, Guarda district since it is the Portuguese region with the highest precipitation values (1715 mm). In the experiment, a direct rainfall exposure index (worst scenario) was considered, which means that a flow rate of 14.26 L/min was used in the rainfall simulation. The outlet pressure in the water nozzle was 45 kPa, respecting the conditions recommended for erosion tests in the international standards.

Figure 6.

Accelerated erosion test: (a) setup; (b) sample preparation; (c) and (d) sample test.

2.2.7. Thermal Transmittance

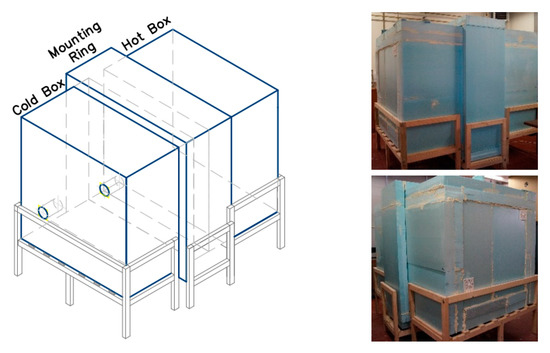

The characterisation of the thermal properties of the CEBs is based on the analysis of the thermal transmittance (U-value) of the product. The thermal transmittance was measured using a guarded hot box set up apparatus, built for this study in the Department of Civil Engineering of the University of Minho, according to ASTM C1363-11:2011 [45] (Figure 7a). The hot box consists of two five-sided chambers (dimensions: 2.0 m × 1.4 m × 1.6 m), the cold and the hot one. The envelope is well insulated, made of extruded polystyrene (20 cm; U = 0.21 W/(m2·K)), to reduce the heat flux through the envelope and minimise heat losses by conduction. The specimen is placed in the mounting ring placed between the two chambers (Figure 7b). The setup is placed in an indoor environment with a controlled temperature below to the ones in the measurement chambers.

Figure 7.

Hot box apparatus. Legend: (a) hotbox closed; (b) cold chamber, mounting ring, and hot chamber; (c) longitudinal plan view of the hotbox apparatus and position of the measurement equipment.

The thermal transmittance of the sample is obtained by measuring the heat flux rate needed to maintain the hot chamber at a steady temperature (in this study 35 ± 5 °C). Two ventilation devices were placed in the back wall of the cold chamber (Figure 7a), which allow the cold air to enter into the chamber and the hot air to exit. The ventilation is necessary to maintain uniform heat flux conditions through the specimen. In the hot chamber, there is a heating system, controlled by a temperature controller, that controls the defined temperature. The temperature in the chambers was measured by four thermocouples (two in each chamber—one in the middle of the chamber, and the other near the sample). A heat flux sensor was installed in the centre of the sample (Figure 7c). Preliminary calibration measurements were carried out successfully to evaluate the heat losses and the heat transfer through a wall with known thermal transmittance.

In this study, the heat flux method was used to determine the U-value. There is a heat flux through a material when there is a temperature difference between two sides. Heat flows from the warmer side to the colder side. It is possible to calculate the U-value of a specimen using the standardised methodology of ISO 9869-1:2014 [46] by assessing the heat flux together with the temperatures in both chambers. In this experiment, the greenTEG gSKIN® U-Value Kit (KIT-2615C) was used to automatically quantify the temperatures, the heat flux through the material and the U-value. The U-value is obtained from the average values of the heat flux through a small CEBs wall sample (composed of three blocks) and the temperature difference, ΔT, between the chambers, using Equation (4). In this experiment, the heat flux was assessed in two points of the CEBs wall.

where

- n is the total number of data points;

- φ is the heat flux in (W/m2);

- ΔT is the temperature (°C) difference between the two sides of the specimen.

3. Results

In this section, the mechanical, durability, and thermal characterisation of the CEBs will be described and discussed.

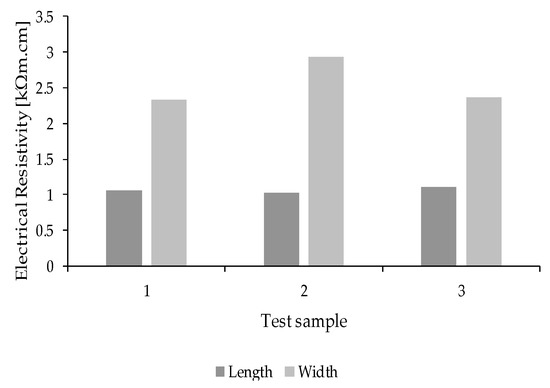

3.1. Electrical Resistivity

Electrical resistivity was measured to analyse the porosity of CEBs, and the results are presented in Figure 8. CEBs have electrical conductivity mainly because ions can propagate in their body. Electrical resistivity is directly dependent on CEBs permeability. In water-saturated CEBs with higher porosity, the propagation of ions is easier, and therefore, there is a lower electrical resistivity [47]. From Figure 8, it is possible to conclude that the measurements done in the direction of the bigger dimension (length) of the sample showed similar results for all samples. However, in the measurements carried out in the other direction (width), sample 2 presented higher values than samples 1 and 3. This result can be an indication that sample 2 was denser, with fewer pores or with pores with smaller dimensions (meaning reduced permeability and conductibility). These outputs disclose some disparity between the porosity of tested CEB samples.

Figure 8.

Results of the electrical resistivity tests of the three specimens carried out in the two directions.

3.2. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity

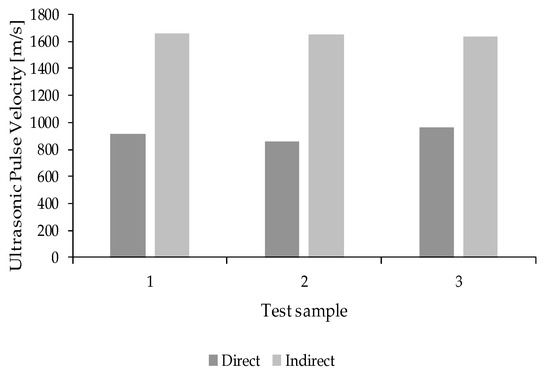

Figure 9 presents the results for the UPV for each sample, using the same samples used in the electrical resistivity test. Five measurements were carried out for every sample (for each direction, direct and indirect) and results presented in Figure 9 are the average of the results obtained for each sample.

Figure 9.

Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity measurements.

A sonic impulse propagates with lower velocity in a porous body and with higher velocity in a denser one. Therefore, according to the analysis of the results, it is possible to conclude that sample 2 presented slightly lower UPV, which can be an indication of a higher number of voids. These results are similar to the electrical resistivity test results. The sample performance differences could be due to the incorrect homogenisation of the soil mixture and/or cracking.

3.3. Compressive Strength

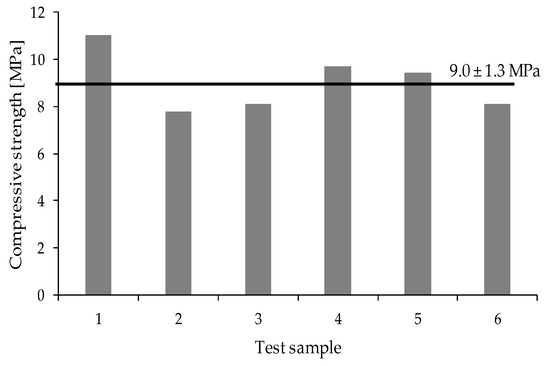

The compressive strength test is considered a reference test for CEBs since it is regarded as an essential indicator of masonry strength. Figure 10 presents the results obtained for the compressive strength of six samples, as well as the average value obtained for this parameter. The results showed a variation on compressive strength between 7.8 MPa and 11.0 MPa, being the average 9.0 ± 1.3 MPa. These values are very good ones since it is known that the minimum compressive strength requirements for CEBs, varying between 1.0 MPa and 2.8 MPa [7,21]. These higher values can be related to the compaction process used since compacting the soil using a press improves the quality of the material. The higher density obtained by compaction significantly increases the compressive strength of the blocks [48]. Another reason for the higher compressive strength is the presence of lime in the mixture. Lime allows the development of calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) together with the formation of minor amounts of calcite, which causes increased strength [21].

Figure 10.

Compressive strength results.

3.4. Total Water Absorption

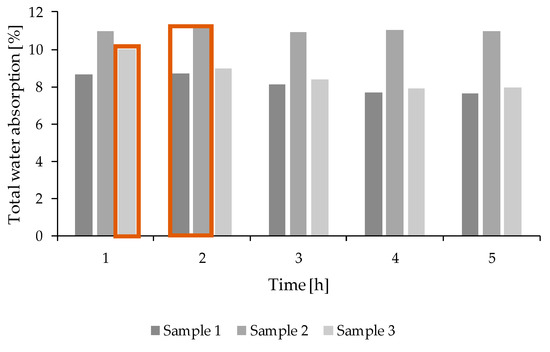

Analysing Figure 11, the maximum values obtained for the total water absorption for each sample were 8.7%, 11.3%, and 10.0% for samples 1, 2, and 3, respectively. It is possible to conclude that the total water absorption varied between 8.7 and 11.3%, being these values favourable when compared with clay bricks (0–30%), concrete blocks (4–25%), or calcium silicate bricks (6–16%) [4]. Although this result seems good, the fast absorption and desegregation of blocks can influence the durability negatively. Total water absorption is influenced by the granulometry of the soil and compaction pressure. These two aspects have a meaningful impact in the density, mechanical strength, compressibility, permeability, and porosity of CEBs [4,48].

Figure 11.

Total water absorption results. The results highlighted by the orange box represents the maximum values obtained in the total water absorption test.

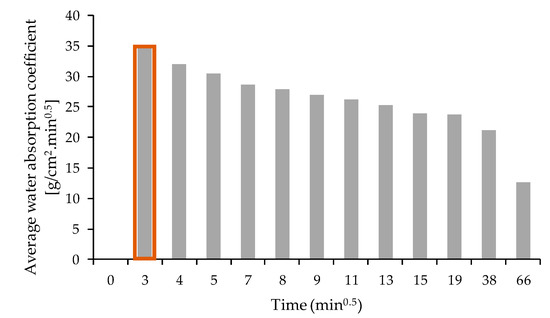

3.5. Water Absorption by Capillarity

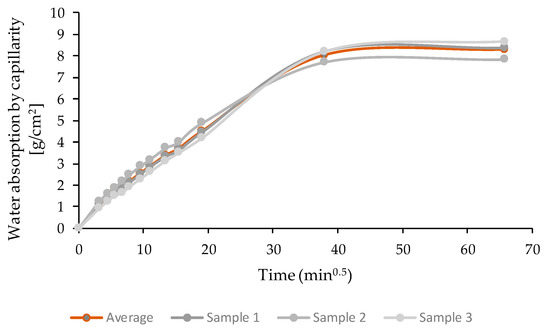

CEBs used in a structure may undergo alternating phenomena of absorption and release of water, mainly because of the capillarity effect [49]. The curves shown in Figure 12 illustrate the variation of water absorption by capillarity until the total saturation of each sample is reached, as a function of the square root of test time. Figure 13 shows the variation of the water absorption coefficient (average of the three samples tested) of compressed earth blocks as a function of the square root of test time. This coefficient was determined for all test periods. However, the literature mentions that the value at the end of 10 min (represented with an orange rectangle in Figure 13) is representative of the behaviour of masonry exposed to a violent storm [21]. At the end of this period, the water absorption coefficient value was 34.6, and therefore, the blocks are classified as having high capillarity [21]. This result can be related to the fact that the soils used to manufacture the CEBs have a high percentage of sand (Table 1). In this study, the high presence of bigger particles (in terms of size) in CEBs seems to be an issue related with the quality of the particle size distribution of the soil, used for the CEBs production, than the quality of the soil itself, which did not cause good reaction with lime and resulted in CEBs with high porosity [10].

Figure 12.

Total water absorption results.

Figure 13.

Variation of the average water absorption during the test period.

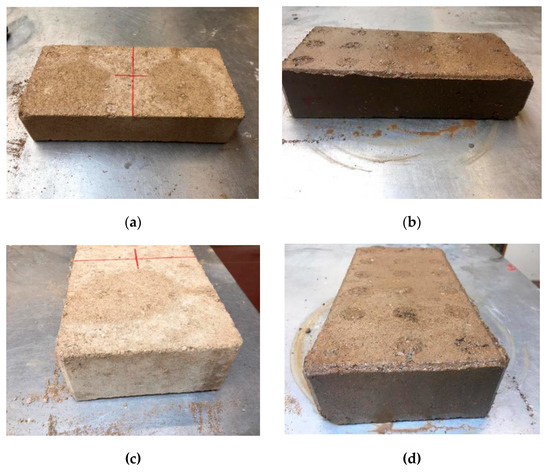

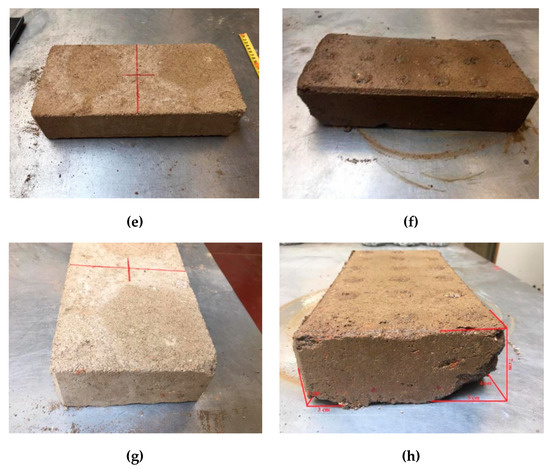

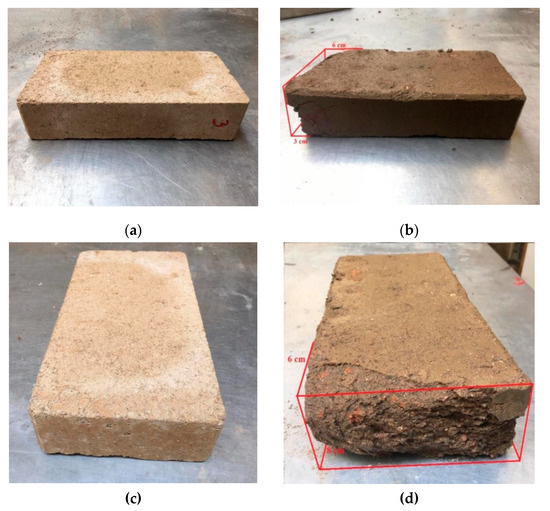

3.6. Accelerated Erosion

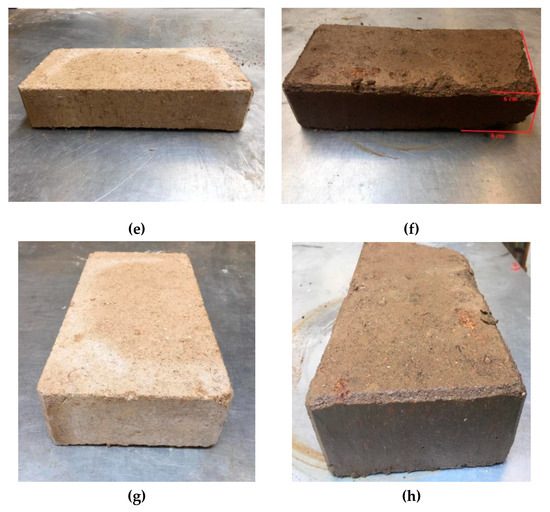

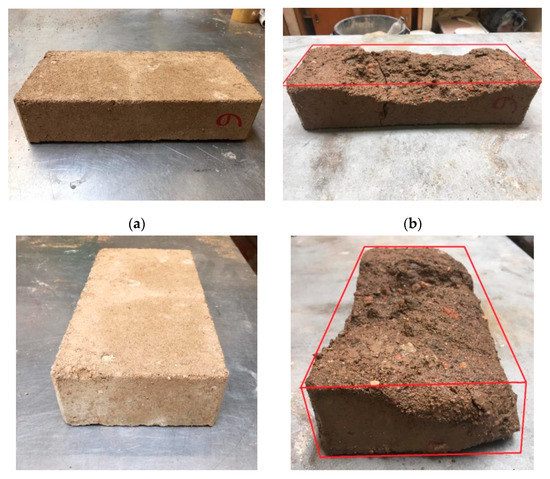

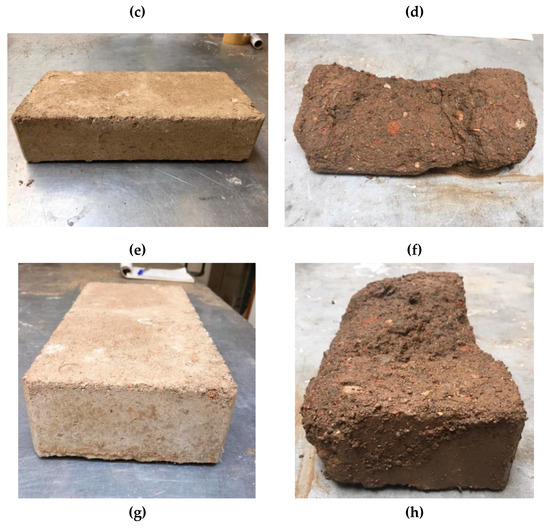

The degradation analysis of CEBs was done, and the results are presented in Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16. A total of seven blocks were analysed in this test. Initially, three blocks were tested for one hour. Since blocks did not present any type of erosion, this test was repeated in four additional blocks, and the results were the same. Based on these results and according to NP EN 12504-4 [39], CEBs were classified with an erosion index of 1 (erosion depth between 0–20 mm/h), which means that they had very good results in terms of durability.

Figure 14.

Accelerated erosion test. (a,c,e,g)—four sides of the exposed face of sample 1 before the test; (b,d,f,h)—four sides of the exposed face of sample 1 after two hours of testing.

Figure 15.

Accelerated erosion test. (a,c,e,g)—four sides of the exposed face of sample 3 before the test; (b,d,f,h)—four sides of exposure face of sample 3 after two hours testing.

Figure 16.

Accelerated erosion test. (a,c,e,g)—four sides of the exposed face of sample 6 before the test; (b,d,f,h)—four sides of the exposed face of sample 6 after testing.

To understand how these blocks behave if exposed for more time to the erosion test and if there is any relation with the other physical properties mentioned before, the analysis was extended for one additional hour.

After two hours of water exposition, CEBs presented different behaviour. Sample 1 did not show significant damage in the majority of faces exposed to water but presented a loss in one part of the block where there was already a small defect before the test (Figure 14). Sample 2 showed similar behaviour to sample 1. Samples 3 (Figure 15), 4 and 5 presented some damage in the two smaller faces, even though the face in contact with the water was the one with a larger area (highlighted with a red cross in Figure 14). Samples 6 (Figure 16) and 7 suffered significant damage, and at the end of two hours, they were almost destroyed. It is then essential to analyse the reasoning behind the different deterioration levels of CEBs since they were manufactured using the same soil, mixture, and compaction process. The most probable explanation for the differences is the inadequate particle size distribution in the soil used. According to the literature in the field of earthen blocks, the soil should only present particles below 5 mm of diameter [48]. Nevertheless, it was possible to see particles with higher dimensions in the most damaged samples (Figure 16d,f,h). These big size particles affected the homogeneity of the mixture, which negatively influenced the porosity and the porous structure of the CEBs. The lack of uniformity in the structure of the blocks worsens their behaviour to water. This problem also explains the results achieved in the total water absorption and water absorption by capillarity tests. The presented porosity and durability issues can be minimised if proper soil preparation and/or selection is considered [18].

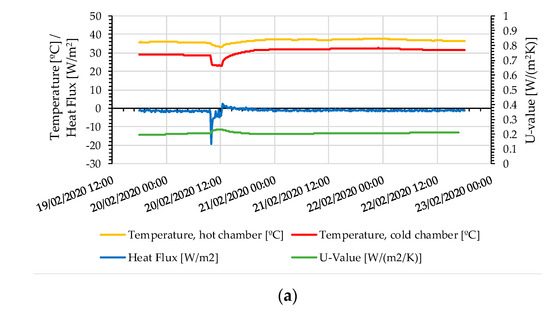

3.7. Thermal Transmittance

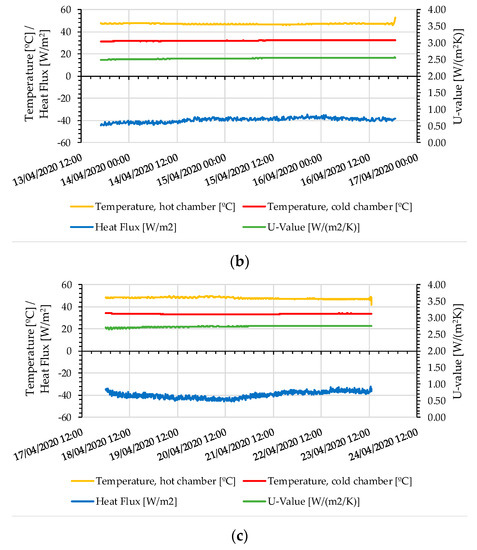

Regarding the thermal transmittance, Figure 17 shows the measurement results for the XPS wall (Figure 17a) and the compressed earth blocks small wall (Figure 17b,c). From the analysis of Figure 17, it is possible to verify that the values measured for temperature and the heat flux were very stable during the test period, in both cases. The temperature in the hot chamber practically did not change since the heat input to the box was controlled so that the temperature established was maintained (35 °C). The heating system turns on when the temperature drops below 35 °C and turns off when the temperature rises to 40 °C. The heat flux is presented as negative values due to heat flux sensor placement in the sample.

Figure 17.

Measurements of the heat flux, hot and cold superficial temperatures and U-value in the XPS wall (a) and in the small CEBs wall (b,c).

The results of the preliminary calibration measurements carried out, using a reference sample with known thermal transmittance (XPS 20 cm), showed an agreement with the technical data provided by the manufacturer (U-value of 0.21 W/(m2·K) and thermal conductivity of 0.60 W/(m·K). The measured thermal transmittance of the 15 cm CEBs wall was of 2.65 ± 0.16 W/(m2·K) (thermal resistance of 0.21 (m2·K)/W on average).

The results indicate that the thermal conductivity of the CEBs studied is significantly lower than the reference values (1.1 W/(m·K)) listed by the Portuguese National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC) [25]. Considering the thickness of the CEBs wall analysed (15 cm), the thermal transmittance of the CEB wall would be approximately 3.26 W/(m2·K) (thermal resistance of 0.31 (m2·K)/W)) (for external walls). The thermal transmittance measured for the CEB wall sample was lower than the value obtained from technical data of LNEC. This result can be explained due to a higher porosity of these blocks, which increased their thermal resistance. This result is in accordance with the other analysis made in those blocks; as was seen in the accelerated erosion test, the CEBs presented a different soil composition, showing in some samples soil particles with a size larger than 5 mm, which leads to a higher thermal conductivity (Figure 16). Moreover, the results could be better if the granulometry of the soil was optimised, since in the experiments found soil particles larger than 5 mm and some small rocks that increase thermal transmittance.

4. Discussion

The compressed earth blocks characterisation is summarised in Table 2. Overall, the results are consistent and show that these blocks presented good mechanical and durability properties and better thermal performance than the reference values listed in the technical data for Portugal, but they also present porosity issues. The non-destructive (electrical resistivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity) and the destructive (water absorption) tests for porosity analysis showed similar results. CEBs samples presented heterogeneity on their mixture composition, which led to the production of blocks with different porosities. The high values obtained in the water absorption test highlight that this is the most problematic characteristic of the CEBs. Contrary, to the other results, the compressive strength analysis and the accelerated erosion test presented significant results. The compressive strength obtained was approximately three times higher than the minimum requirement for CEBs. Moreover, these CEBs were classified as erosion index of 1, which means that they have an erosion depth between 0–20 mm/h, are very resistant, and have good durability properties.

Table 2.

Thermophysical proprieties of the analysed compressed earth blocks.

One of the essential features of these building elements is thermal resistance. In this study, thermal transmittance was analysed, corresponding to a U-value of 2.66 W/(m2·K). The results seem to be in accordance with the results obtained for the quality and durability parameters, showing that the results could be better if the granulometry of the soil was optimised, since in the experiments found soil particles larger than 5 mm and some small rocks that increase thermal transmittance. Therefore, the optimisation of the soil particle size distribution in the mixture before CEB production is necessary to increase thermal performance while maintaining high mechanical resistance.

5. Conclusions

The results presented in this study show a strong relationship between soil and mixture preparation and compaction with CEB properties. During the investigation, it was possible to observe that the use of soil with particles with higher dimensions than the ones recommended by the international standards for CEB production had a significant effect in some of CEBs properties, such as: porosity, water absorption, durability and thermal performance. However, even though these blocks did not have the proper production, they did not present mechanical resistance issues. In general, the analysed CEBs are adequate to be used for construction of partition walls. Moreover, it was seen in the literature that these blocks presented several benefits in terms of environmental performance. Taking this into account, optimising the soil particle size distribution in the mixture before CEB production could be a solution to minimise these issues (mainly in thermal performance) while maintaining high mechanical resistance. The optimisation of the distribution will lead to a production of elements with lower porosity, and it is known that porosity has a direct relation to mechanical resistance and durability. However, by reducing porosity, it is expected that thermal transmittance increases. The study of CEB optimisation and the characterisation of the optimised CEB properties will be studied in the future in order to assess the real contribution of this optimisation in CEB mechanical, durability, and thermal performance. In short, optimisation of compressed earth blocks is necessary to improve their functional quality and increase their potential for use in the construction of buildings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.T., J.F., and R.M.; methodology, E.R.T., S.M.S., and R.M.; validation, S.M.S. and R.M.; formal analysis, E.R.T. and J.F.; investigation, E.R.T., G.M., A.d.P.J., and C.G.; resources, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.T.; writing—review and editing, E.R.T., A.d.P.J., C.G., J.F., S.M.S., and R.M.; supervision, S.M.S. and R.M.; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the support granted by the FEDER funds through the Competitively and Internationalization Operational Programme (POCI) and by national funds through FCT (the Foundation for Science and Technology) within the scope of the project with the reference POCI-01-0145-FEDER-029328, and of the Ph.D. grant with the reference PD/BD/113641/2015, which were fundamental for the development of this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support granted by DANOSA “Derivados asfálticos normalizados, S.A.” industry for the hotbox construction by providing all the necessary insulation material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Minke, G. Building with Earth: Design and Technology of a Sustainable Architecture; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 9783034608725. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.; Peixoto, M.; Mateus, R.; Gervásio, H. Life cycle analysis of environmental impacts of earthen materials in the Portuguese context: Rammed earth and compressed earth blocks. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Jalali, S. Earth construction: Lessons from the past for future eco-efficient construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taallah, B.; Guettala, A.; Guettala, S.; Kriker, A. Mechanical properties and hygroscopicity behavior of compressed earth block filled by date palm fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 59, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, D.; Barbosa, J.; Soares, E.; Miranda, T.; Cristelo, N.; Briga-Sá, A. Thermal performance assessment of masonry made of ICEB’s stabilised with alkali-activated fly ash. Energy Build. 2017, 139, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, G.; Zhang, X.; Edris, W.F.; Cañas, I.; Garijo, L. A comprehensive study of mechanical properties of compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.B.; Jelidi, A.; Cherif, A.S.; Jabrallah, S.B. Optimizing thermal and mechanical performance of compressed earth blocks (CEB). Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 104, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, M.; Cherif, A.S.; Zeghmati, B.; Sediki, E. Stabilization effects on the thermal conductivity and sorption behavior of earth bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibeddra, S.; Kharchi, F. Performance of Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks in sulphated medium. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdad, M.; Benidir, A. Hydro-mechanical properties and durability of earth blocks: Influence of different stabilisers and compaction levels. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban. Dev. 2018, 9, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gustavsen, A.; Jelle, B.P.; Yang, L.; Gao, T.; Wang, Y. Thermal conductivity of cement stabilized earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie Arsène, M.I.; Frédéric, C.; Nathalie, F. Improvement of lifetime of compressed earth blocks by adding limestone, sandstone and porphyry aggregates. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Elahi, T.E.; Shahriar, A.R.; Mumtaz, N. Effectiveness of fly ash and cement for compressed stabilized earth block construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 255, 119392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, A.H.; Walker, P.; Venkatarama Reddy, B.V.; Heath, A.; Maskell, D. Mechanical and thermal properties, and comparative life-cycle impacts, of stabilised earth building products. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, R.; Benazzoug, M.; Kenai, S. Performance of compacted cement-stabilised soil. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amoudi, O.S.B.; Khan, K.; Al-Kahtani, N.S. Stabilization of a Saudi calcareous marl soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guettala, A.; Abibsi, A.; Houari, H. Durability study of stabilized earth concrete under both laboratory and climatic conditions exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, K.K.G.K.D.; Jayasinghe, C. Cement stabilized rammed earth as a sustainable construction material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toure, P.M.; Sambou, V.; Faye, M.; Thiam, A. Mechanical and thermal characterization of stabilized earth bricks. Energy Procedia 2017, 139, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouny, F.; Fouchal, F.; Pop, O.; Maillard, P.; Rossignol, S. Mechanical behavior of an assembly of wood-geopolymer-earth bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taallah, B.; Guettala, A. The mechanical and physical properties of compressed earth block stabilized with lime and filled with untreated and alkali-treated date palm fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 104, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guettala, A.; Houari, H.; Mezghiche, B.; Chebili, R. Durability of lime stabilized earth blocks. Courr. Savoir 2002, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.; Mateus, R.; Gervásio, H.; Silva, S.M.; Bragança, L. Passive strategies used in Southern Portugal vernacular rammed earth buildings and their influence in thermal performance. Renew. Energy 2019, 142, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, E.A.; Jones, P.J. Thermophysical properties of stabilised soil building blocks. Build. Environ. 1995, 30, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina dos Santos, C.A. ITE50—Coeficientes de Transmissão Térmica de Elementos da Envolvente dos Edifícios; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, B. The Ecology of Building Materials, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 9781856175371. [Google Scholar]

- LNEC. 196: Solos - Análise Granulométrica; Especificação do Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 1966; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- IPQ. EN, NP. 933-8, Norma Portuguesa (Setembro de 2002). In Ensaios das Propriedades Geométricas dos Agregados: Determinação do Teor de Finos - Ensaio do Equivalente de Areia; IPQ: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- IPQ. EN, NP. 933-9. In Ensaios das Propriedades Geométricas dos Agregados Parte 9: Determinação de Finos - Ensaio do Azul de Metileno; IPQ: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- IPQ. NP, NP. 143: 1969. In Determinação dos Limites de Consistência; IPQ: Lisboa, Portugal, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- LNEC. 197: Solo-Cimento. Ensaio de Compactação; Especificação do Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 1966; Volume xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Standard A.S.T.M. D3282 (2009) Standard Practice for Classification of Soils and Soil-Aggregate Mixtures for Highway Construction Purposes; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doat, P.; Hays, A.; Houben, H.; Matuk, S.; Vitoux, F.; CraTerre, F. Building with Earth, 1st ed.; The Mud Village Society: New Delhi, India, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arab, P.B.; Araújo, T.P.; Pejon, O.J. Identification of clay minerals in mixtures subjected to differential thermal and thermogravimetry analyses and methylene blue adsorption tests. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 114, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukselen, Y.; Kaya, A. Suitability of the methylene blue test for surface area, cation exchange capacity and swell potential determination of clayey soils. Eng. Geol. 2008, 102, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Gomes, N. Caracterização de Blocos de Terra para Construção de Alvenarias Ecoeficientes. Master’s Thesis, University Nova, Lisbon, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Canivell, J.; Martin-del-Rio, J.J.; Alejandre, F.J.; García-Heras, J.; Jimenez-Aguilar, A. Considerations on the physical and mechanical properties of lime-stabilized rammed earth walls and their evaluation by ultrasonic pulse velocity testing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-del-Rio, J.J.; Canivell, J.; Falcón, R.M. The use of non-destructive testing to evaluate the compressive strength of a lime-stabilised rammed-earth wall: Rebound index and ultrasonic pulse velocity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPQ. EN, NP. 12504-4. 2007, Ensaios de Betão nas estruturas—Parte 4: Determinação da velocidade de propagação dos ultra-sons; IPQ: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IPQ. EN, NP. 772-1. 2002, Methods of Test for Masonry Units—Part 1: Determination of Compressive Strength; IPQ: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kerali, A.G. Durability of Compressed and Cement-Stabilised Buildings Blocks. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- LNEC. 394, Betões, Determinação da Absorção de Água por Imersão, Ensaio à Pressão Atmosférica; Laboratório Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- LNEC. 393, Concrete—Determination of the Absorption of Water through Capillarity; Test at environment pressure (in Portuguese). Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- UNE 41410. Bloques de tierra comprimida para muros y tabiques Definiciones, especificaciones y métodos de ensayo. Asoc. Española Norm. Y Certif. —Aenor 2008, 26.

- Standard A.S.T.M. C1363-11, Standard Test Method for Thermal Performance of Building Materials and Envelope Assemblies by Means of a Hot Box Apparatus; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- BSI. BS ISO 9869-1: 2014: Thermal Insulation–Building Elements–in situ Measurement of Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Part 1: Heat Flow Meter Method; BSI: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Motahari Karein, S.M.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Ebadi, T.; Isapour, S.; Karakouzian, M. A new approach for application of silica fume in concrete: Wet granulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 157, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigassi, V.; CRATerre-EAG. Compressed Earth Blocks: Manual of Production; Deutsches Zentrum für Entwicklungstechnologien—GATE: Eschborn, Germany, 1985; Volume I, ISBN 3528020792. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, E.A.; Agib, A.R.A. Compressed Stabilised Earth Block Manufacture in Sudan; Graphoprint for UNESCO: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).