Abstract

Osteochondroma is frequently found in the general skeleton but is rare in the condylar region of the mandible. We report a case of an osteochondroma of large size and rapid growth in the mandibular condyle, which was treated with total condylectomy and condylar replacement with a costochondral graft and preservation of the articular disc. In cases with a healthy and well-positioned articular disc, it may be preserved with no need of disc repositioning.

Osteochondroma, also known as osteocartilaginous exostosis, is one of the most common benign tumors of long bones, but it may occur in any bone that forms by endochondral ossification and has been reported in nearly every part of the craniofacial skeleton that is embryologically derived from a preexisting cartilage model including the skull base, maxillary sinus, zygomatic arch, nasal septum, and mandible.[1] The most common sites of occurrence in the craniofacial region are the coronoid process of the mandible and the mandibular condyle.[2]

Patients suffering from condylar osteochondromas are usually older as compared with osteochondromas in other locations (average 40 years). In a series of 34 osteochondromas, Peroz et al[3] found that there was a female preponderance with a female:male ratio of 1.5:1. The pathogenesis of these tumors is still controversial.[1] Osteochondromas are benign and slow-growing tumors that cause gradual displacement and elongation of the mandible and may lead to a severe malocclusion. Infrequent complications of untreated osteochondroma are hearing loss and pain.[4]

Several methods have been reported for the treatment of condylar osteochondromas. Surgical treatments include resection through a conservative condylectomy, total condylectomy with reconstruction or selected tumor removal without condylectomy.[2,5,6,7,8] We report a case of an osteochondroma of large size and rapid growth in the mandibular condyle, which was treated with total condylectomy and condylar replacement with a costochondral graft and preservation of the articular disc. The clinical symptoms, anatomical features, histological characteristics, and differential diagnosis of these lesions are also discussed.

Case Report

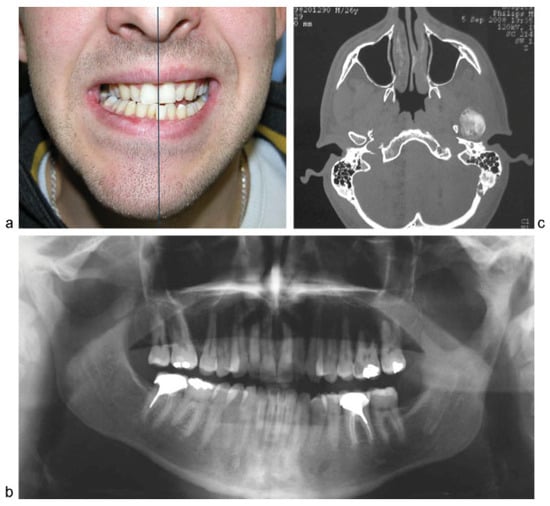

A 24-year-old man was referred to our Hospital for progressive facial asymmetry and limited mouth opening over a period of 6 months. Clinical examination showed marked asymmetry with prognathic deviation of the chin to the right side and vertical displacement of the left mandibular angle (Figure 1a). The maximal mouth opening was 23 mm with an opening pattern of uncorrected deviation to the right side. In occlusion, there was a unilateral open bite in the left posterior region and a contralateral cross-bite. No pain was observed. A panoramic radiograph revealed a well-circumscribed and radiopaque image at the left condylar head. The coronal, axial and three-dimensional computed tomography images showed a 3 × 1 cm dense mass developing from the medial region of the condylar head (Figure 1b, c). On the basis of clinical and imaging findings an initial diagnosis of benign condylar neoplasm, osteoma or osteochondroma, was proposed.

Figure 1.

(a–c) Marked facial asymmetry with prognathic deviation of the chin to the right side and vertical displacement of the left mandibular angle. Preoperative panoramic radiograph and CT scan: showing a radiopaque and well-circumscribed image at the left condylar head. CT, computed tomography.

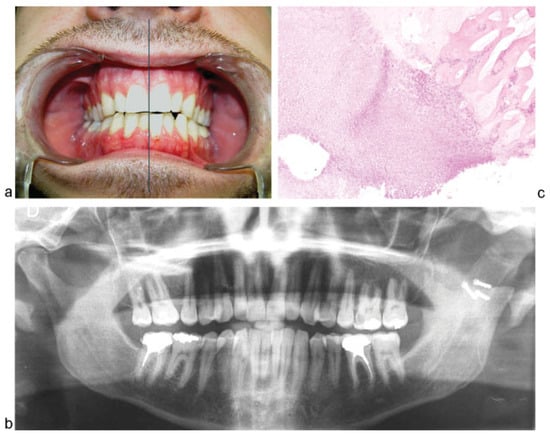

Tumor excision was performed under general anesthesia and nasotracheal intubation. Surgical approach was performed across an Al-Kayat Bramley technique in combination with a submandibular incision. The condyle and ramus were dissected subperiosteally and a 30-mm diameter lesion was observed with a medial projection to the skull base region. Due to the tumoral size, it was removed performing a total condylectomy just below the condylar neck with preservation of the intact articular disc and without damaging the peripheral anatomic structures. Condylar reconstruction was achieved using a costochondral graft fixed by three screws (Figure 2a–c). No complications in terms of infection or hemorrhage occurred postoperatively. An adequate occlusion was maintained by intermaxillary fixation for 2 weeks. In the immediate postoperative period the patient presented a transient palsy of the temporal branch of the facial nerve, which resolved completely in 3 months. At 15 months followup, the maximal mouth opening was 40 mm and the patient had an adequate mandibular function without occlusal alterations. The panoramic radiograph at this point follow-up showed no signs of recurrence and no resorption of the costochondral graft (Figure 3a,b). Histopathologic examination revealed a thickened cartilaginous cap over the head of the condyle and the islands of cartilaginous inclusions within the adjacent bone trabeculae of variable size (Figure 3b). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of osteochondroma.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Removal of the tumor by means of a total condylectomy just below the condylar neck with preservation of the intact articular disc (blue arrow) and without damaging the peripheral anatomic structures. The big size of the tumor is appreciated. Immediate reconstruction by means of a chondrocostal graft (yellow arrow).

Figure 3.

(a–c) Postoperative situation at 15-month follow-up: facial symmetry, mouth opening of 40 mm, and no occlusal alterations. Postoperative panoramic radiograph at 15-month follow-up: no signs of recurrence and no resorption of the costochondral graft. Histopathologic examination: this sample shows the transition between the cartilage and bone.

Discussion

Among the reported benign tumors of the condyle, chondromas, osteomas, and osteochondromas are the most common.[1] Condyle osteochondromas are mostly found on the medial aspect (57%), followed by the anterior (20%) and rarely in lateral or superior positions (< 1%).[3] This can be explained by the theory of focal accumulation of embryonic connective tissue with cartilaginous potential at the site of tendon insertions. Continued stress and strains in the insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle may cause hyperplastic changes in these cells. This may also explain the occurrence of these tumors in the coronoid process stressed by the tension of the temporalis muscle.[2,5] The etiology of these tumors is still controversial. Some authors consider that trauma and infection may play a role in the formation of these lesions.[9,10] Other hypotheses are based on residues from the cartilaginous primordial cranium or in a neoplastic pathogenesis.[3,4]

The growth of osteochondromas is usually slow, causing gradual displacement of the midline, elongation of the mandible, increased vertical growth, and can lead to a severe malocclusion. In slow growth cases, there is a reciprocal compensatory vertical growth of the maxilla with canting of the occlusal plane.[10] In our case the growth was rapid (6 months) resulting in a unilateral posterior open bite on the left side, contralateral cross-bite, no deviation of the mandibular midline, and vertical displacement of the left mandibular angle. In this situation, there was no change in the maxillary occlusion. Other clinical symptomatology in patients with osteochondromas may include disc displacement, loss of condylar function and, rarely, pain.[5] However, Holmund et al reported five patients with unilateral osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle where the main complaint was pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and no patient was so disturbed by the facial asymmetry.[11]

Radiographically, osteochondroma is predominantly an exophytic mass of mixed density. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are important, not only for visualizing and locating the lesion, but also for evaluating the relation with adjacent structures.[5,12]

Histologically, osteochondroma needs to be distinguished from osteoblastoma, chondroma, benign osteoblastoma, and chondroblastoma.[11] The histologic examination consists of a cartilaginous cap with hypertrophic chondrocytes arranged in clusters covered by a broad layer of partially loose periosteal collagen tissue. Regular bony trabeculae produced by enchondral ossification are seen.[13]

As Holmund et al reported, when considering treatment, it is crucial to determine if the lesion is growing or is in an inactive state by repeated imaging. If the lesion is inactive and without TMJ symptoms, surgical intervention would be to an address a cosmetic deformity or related to a masticatory dysfunction.[11] If active growth is present, surgical resection is the treatment of choice. Various surgical treatments have been reported. The traditional treatment of condylar osteochondromas consists of total condylectomy with immediate reconstruction, usually by means of costochondral graft or total joint prosthesis.[2,8] Based on the benign nature of osteochondromas and its low risk of recurrence (2%), Aydin et al and Ortakoglu et al supported a minimally invasive treatment for osteochondromas by removing only the portion of condyle involved by the lesion, reshaping the remaining condyle and subsequent plication of the disc.[1,10] Peroz et al performed an extended review of the literature, describing the clinical, histological, and surgical criteria of 34 cases reported. A total of 26 patients were treated by condylectomy, while 9 patients had the osteochondroma removed. No recurrence appeared in cases treated with condylectomy, whereas two recurrences were reported in the nine patients treated with resection of the lesion. Malignant transformation has been reported to be extremely rare in cases of solitary lesions.[3] However, Barret et al reported a case of a secondary chondrosarcoma arising in osteochondroma of the nasal septum.[13] Wolford et al presented a conservative condylectomy technique, with the osteotomy performed below the condylar head, but high in the condylar neck, and articular disc repositioning for the treatment of mandibular condyle osteochondromas.[5] After the remaining condylar neck was reshaped, an orthognathic procedure for reposition of the condylar stump and disc into the glenoid fossa was performed. Five patients required maxillary and mandibular orthognathic surgery for concomitant correction of the dentofacial deformity, while only one patient underwent an ipsilateral sagittal split osteotomy of the mandible. They reported the results of this technique in six patients with diagnosis of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle. No recurrence of the tumor was observed during the follow-up which ranged from 22 to 108 months. Evaluations of TMJ function and range of mandibular motion were normal. These authors stated that this technique was an acceptable treatment for osteochondromas of the mandibular condyle with several advantages such as removing the pathology while maintaining native mandibular bone and the articular disc, allowing correction of the facial deformity with concomitant orthognathic surgery and eliminating the need of a graft and, therefore, reducing the morbidity.[5] Holmund et al[11] reported a 5-year follow-up of five patients with mandibular condyle osteochondromas treated by condylectomy with reshaping of the condylar neck and vertical ramus osteotomy, which is advanced to form a new condyle underneath the disc preserved (a technique described by Loftus et al[14]). Ramus osteotomies were performed on the contralateral side in three patients for mandibular set back. All patients presented occlusal changes, four had an open bite in the affected side and one patient had a compensatory growth of the maxilla. During the 5-year follow-up, no patient showed recurrent growth and all patients showed a good and stable occlusion. Martinez-Lage et al[15] reported three adult patients, two with osteochondroma and one with hyperplasia treated also by condylectomy and simultaneous reconstruction with an oblique vertical-sliding ramus osteotomy with postoperative stable results. The tumor size and condylar neck extension in our case required an osteotomy just below the condylar neck. Therefore, as we did not have a remaining neck to reshape, we decided on an autogenous graft, concretely a costochondral graft, for condylar reconstruction.

TMJ reconstruction can be performed with costochondral, fibula, metatarsal, clavicle, iliac crest grafts, coronoid process, grafts and alloplastic condylar implants.[16] The costochondral graft, described by Gillies (1920) and popularized by Ware and Brown (1981) has been widely used by many authors with very good results. The benefits described by McIntosh are its biological compatibility, ease of use, functional adaptability, versatility, and minimal additional morbidity for the patient.[17] The growth potential of the costochondral graft makes it an ideal choice in children.[18] However, it presents problems such as risk of fracture, further ankylosis, unpredictable growth, and possible partial or total graft resorption.[19] In our case the last control panoramic radiograph showed no signs of resorption. Moreover, within 15 months the patient had an optimal mandibular function, aesthetic, and a stable occlusion with no need for additional orthognathic surgery. Joint prosthesis could be another option for TMJ reconstruction. We considered that in the case of our young patient, 24 years old, and with an intact articular disc, a joint prosthesis would have been an excessive aggressive treatment with possible need of replacement at long-term follow-up. Both Wolford et al and Holmund et al performed disc repositioning in the treatment of osteochondromas.[5,11] Our patient presented an intact and healthy articular disc with a correct position so we decided to preserve it without repositioning and avoid lateral pterygoid muscle liberation. During the follow-up, the patient showed an adequate mandibular function with no clicking and no pain has been reported. Therefore, we suggest the preservation of the disc, without repositioning, in cases of well-positioned and healthy-appearing articular disc.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aydin, M.A.; Küçükçelebi, A.; Sayilkan, S.; Celebioğlu, S. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: Report of 2 cases treated with conservative surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001, 59, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karras, S.C.; Wolford, L.M.; Cottrell, D.A. Concurrent osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle and ipsilateral cranial base resulting in temperomandibular joint ankylosis: Report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996, 54, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peroz, I.; Scholman, H.J.; Hell, B. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 31, 455–456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seki, H.; Fukuda, M.; Takahashi, T.; Iino, M. Condylar osteochondroma with complete hearing loss: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 61, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolford, L.M.; Mehra, P.; Franco, P. Use of conservative condylectomy for treatment of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 60, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roychoudhury, A.; Bhatt, K.; Yadav, R.; Bhutia, O.; Roychoudhury, S. Review of osteochondroma of mandibular condyle and report of a case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 69, 2815–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, T.; Schroth, G.; Laeng, R.H.; Lädrach, K. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996, 54, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, K.; Ogi, N.; Echiverre, N.V.; Yoshida, K. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999, 28, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutilli, B.J.; Quinn, P.D. Traumatically induced peripheral osteoma. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992, 73, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortakoglu, K.; Akcam, T.; Sencimen, M.; Karakoc, O.; Ozyigit, H.A.; Bengi, O. Osteochondroma of the mandible causing severe facial asymme-try: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007, 103, e21–e28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmlund, A.B.; Gynther, G.W.; Reinholt, F.P. Surgical treatment of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle in the adult. A 5-year follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 33, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, S.; Long, X.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, M.; Cai, H. The clinical and radiographic characteristics of condylar osteochondroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012, 114, e66–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, A.W.; Hopper, C.; Speight, P.M. Oral presentation of secondary chondrosarcoma arising in osteochondroma of the nasal septum. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996, 25, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loftus, M.J.; Bennett, J.A.; Fantasia, J.E. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyles. Report of three cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986, 61, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Lage, J.L.; González, J.; Pineda, A.; Álvarez, I. Condylar reconstruction by oblique sliding vertical-ramus osteotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2004, 32, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, B.C.; Porto, G.G.; Bessa-Nogueira, R.V.; Nascimento, M.M. Surgical treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis: Followup of 15 cases and literature review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009, 14, E34–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- MacIntosh, R.B. The use of autogenous tissues for temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000, 58, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaban, L.B.; Perrott, D.H.; Fisher, K. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990, 48, 1145–1151, discussion 1152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohara, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ohta, E. Chest wall deformities and thoracic scoliosis after costal cartilage graft harvesting. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997, 99, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the author. The Author(s) 2014.