Abstract

Study Design: A retrospective analysis of patients with subcondylar fractures treated via a transmasseteric ante- roparotid approach by the Oral and Maxillofacial Department at the University of Oklahoma. Objective: The goal of this study was to evaluate complications, morbidity, and safety with the transmasseteric ante- roparotid approach for treatment of subcondylar fractures, and compare it to other findings previously reported in the literature. Methods: A retrospective study was conducted that consisted of 23 surgically treated patients in the past 2 years for subcondylar fractures. Only patients with pre-operative malocclusion and who underwent open reduction with internal fixation with the transmasseteric anteroparotid (TMAP) approach were included. Exclusion criteria included 1) patients treated with closed reduction 2) patients who failed the minimum of 1, 3, and 6-week post-operative visits. The examined parameters were the degree of mouth opening, occlusal relationship, facial nerve function, incidence of salivary fistula and results of imaging studies. Results: 20 of the surgically treated patients met the inclusion criteria. Two patients were excluded due to poor post-operative follow up and 1 was a revision of an attempted closed reduction by an outside surgeon that presented with pre-existing complications. There were no cases of temporary or permanent facial nerve paralysis reported. There were 3 salivary fistulas and 2 sialoceles, which were managed conservatively and resolved within 2 weeks, and 2 cases of inadequate post-surgical maximal incisal opening (<40 mm) were observed. Conclusion: The transmasseteric anteroparotid approach is a safe approach for open reduction and internal fixation of low condylar neck and subcondylar fractures, and it has minimal complications.

Introduction

Mandibular fractures are the third most frequent maxillo- facial fractures after nasal and zygomatic bone fractures.[1] Condylar fractures constitute 17.5% to 50% of all mandibular fractures. In a 17-year retrospective study analyzing the pattern of 4,143 mandibular fractures, condylar fractures were shown to comprise 18.4% of all mandibular fractures.[2] These fractures are typically a result of an indi- rect force transferred to the condyle from a blow elsewhere. Their displacement is determined by the direction, degree, magnitude and precise point of application of the force, as well as the state of dentition and the occlusal position.[3] One commonly cited indication for open treatment of condylar fractures are those that have 10 to 45 degrees of deviation and/or more than 2 mm loss of vertical ramus height.[4] Teeth in occlusion with proper function seem to be the most important goal in the treatment of any mandibular fracture.[5]

Various classifications of condylar fractures are reported in the literature. Lindahl classified condylar frac- tures based on the anatomic level of the fracture: condylar head, condylar neck, and subcondylar.[6] Subcondylar frac- tures are further classified according to: 1 dislocation at the fracture level; and 2 position of the condylar head with respect to articular fossa. Spiessl and Schroll proposed 6 fracture types that described the fracture of the condylar head and neck and the dislocation or displacement of the condylar head.[7] Bhagol et al developed a subcondylar frac- ture classification system describing the degree of fracture displacement and ramus height shortening.[4]

Management of these fractures remains a controversial topic in maxillofacial trauma. Treatment modalities include observation with physiotherapy, closed reduction (CR) treatment, and open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) via transfacial or intraoral approaches. The decision of which treatment modality to employ can be based on several fac- tors: degree and direction of displacement, level of fracture, position of the condylar head in relation to the glenoid fossa, position of the fractured bone segments, loss of ver- tical ramus height, patient age, dental status, and accom- panying fractures of the facial skeleton.[1] Several meta-analyses have been published comparing the func- tional outcomes between and ORIF and CR treatment for mandibular condyle fractures.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14] Ellis et al found that patients treated by closed techniques had a significantly greater percentage of malocclusion compared with patients treated by open reduction, in spite of the fact that the initial displacement of the fractures was greater in patients treated by open reduction.[15]

A proposed list of absolute and relative indications for open treatment of mandibular condyle fractures was described by Zide and Kent in 1983 and has been revised by numerous authors since that time.[16] Several open approaches to these fractures have been described in the literature with one of the most common being a variation of the retromandibular transparotid approach. Other open approaches described in the literature include the subman- dibular, transmasseteric/transparotid, pre-auricular and intraoral approaches.[17] The surgical approach used to access the condylar fracture for open reduction internal fixation is determined by the level of the fracture and degree of displacement as well as the surgeon’s experience and skill level. The patient’s desire to be treated by an open or closed approach can also dictate treatment, and potential complications of the 2 modalities must be discussed.

Possible complications associated with open treatment include facial nerve paralysis, salivary fistulae, sialocele, and Frey syndrome, post-operative malocclusion, hema- toma, wound infection, and non-esthetic scarring. The pre- valence of facial nerve injury after open treatment of mandibular condyle fractures ranges from 12% to 48%.[18,19] Ellis et al conducted a prospective study of 93 patients treated open via the retromandibular approach and found the rate of temporary facial nerve injury to be 17.2% at 6 weeks after surgery, all of which had resolved after 6 months.[20] Patients with closed treatment may sustain similar post-operative complications including malocclusion, mandibular asymmetry, and restricted masticatory function or ankylosis.

The endoscopic technique allows visualization of the fracture through small incisions, which leads to less visible scarring and a lower risk of facial nerve injury. The endoscopic technique can be performed intraorally or extraorally. This approach does require additional training and skill as well as increased operating time.

The TMAP is an excellent option to treat subcondylar fractures. It provides a straightforward dissection to the mandibular ramus, adequate exposure for reduction and fixation, with minimal risk to adjacent vital structures, and an inconspicuous scar. The aim of this paper was to evaluate the efficiency and safety of the TMAP approach to reduce and fix displaced condylar fractures.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective study that evaluated the medical records of patients that underwent ORIF of subcondylar fractures at the Oral and Maxillofacial surgery department at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center from August 2017 to August 2019. The study was registered with our facility’s Institutional Review Board under the number 11058. In this time frame there were 53 patients that pre- sented to our oral and maxillofacial surgery department with subcondylar fractures. Twenty-three of these patients were treated open via a transmasseteric anteroparotid approach. The determination for open versus closed treat- ment was made based on the level of the fracture and degree of displacement, pre-operative malocclusion, and patients’ desires. The patients were followed up for a min- imum 6-week post-operative period.

During follow up, the monitored parameters included:

- Facial nerve function;

- Re-establishment of pre-injury occlusion;

- Maximal incisal opening;

- Presence and resolution of sialocele/parotidocuta- neous fistula.

Surgical Procedure

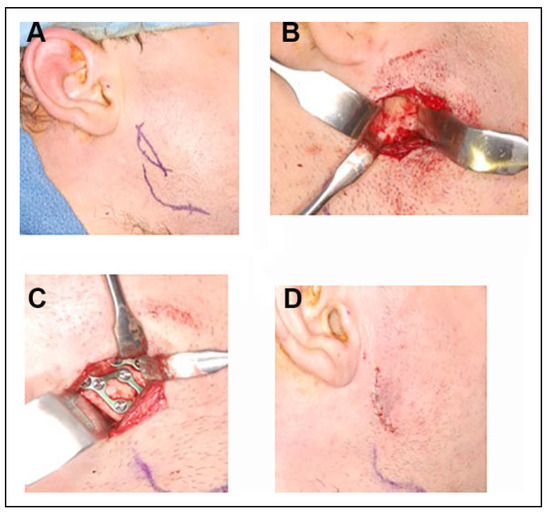

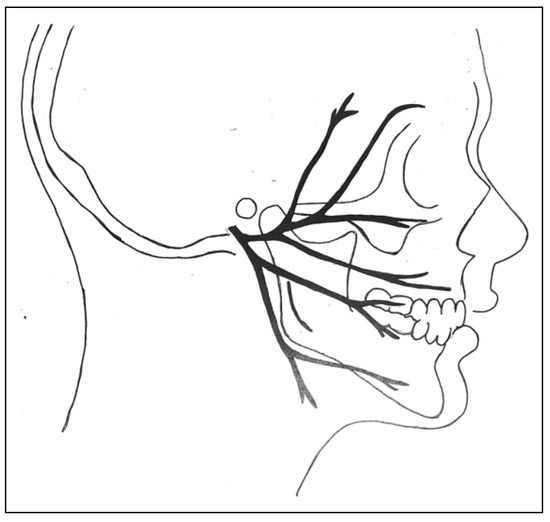

All patients included in this study had their surgery per- formed by the same primary surgeon with OMFS residents from the University of Oklahoma using a transmasseteric anteroparotid approach for open reduction internal fixation of the condylar fractures. The patient was placed in a supine position with head tilted to the contralateral side after nasotracheal intubation with a nasal RAE was per- formed. Prior to the extraoral incision, Erich arch bars were placed and the patient was placed into MMF with elastics. The incision site was then marked in the following manner: a sterile ruler was used to measure the distance from the center of the tragus to the antegonial notch, which typically measures roughly 9 cm; with the ruler still in position a 3 cm long mark was made on the skin over the middle third of the previous measurement; the incision was then marked in a curvilinear fashion posterior to the 3 cm line (Figure 1A). This measurement and incision design keeps the plane of dissection between the marginal and buccal branches of the facial nerve as shown in Figure 2. A 15 blade was then used to make an incision through skin and subcutaneous tissues, until the superficial musculoapo- neurotic system (SMAS) layer was reached. At this point, the SMAS was undermined and divided with electrocau- tery. Facial nerve monitoring was utilized throughout the dissection. Once the parotid capsule was reached, blunt dissection with 2 mosquito hemostats was carried through the parotid gland and masseter until the lateral border of the ramus was visualized. Once the lateral aspect of the ramus is encountered, a periosteal elevator is used to dissect in a subperiosteal plane to expose the lateral surface of the ramus and the fractured condylar process in order to achieve adequate reduction at with enough room to place hardware (Figure 1B). When the fracture pattern permits, a 3D mini-plate with an anti-rotational limb that extends anteriorly was the fixation method of choice (Figure 1C). To aid with fracture reduction the distal segment was dis- tracted inferiorly by placing a large osteotome over the occlusal table of the ipsilateral posterior teeth. By rotating the osteotome, the distal segment was rotated down, creat- ing space for fracture reduction. After adequate reduction was obtained, MMF with heavy elastics was performed and the internal fixation applied. The incision was then closed in layers to obtain a watertight closure of the parotidomas- seteric fascia and SMAS (Figure 1D). A pressure dressing was then placed over the surgical site and left in place for 48 hours. The patient is removed from maxilla-mandibular fixation prior to extubation and placed into guiding elastics. The patients were transitioned into elastics immediately post operatively and encouraged to function with the joint. All patients were placed on a soft no chew diet for 6 weeks after fixation. The goal of early mobilization was to reduce the risk of ankylosis of the affected joint. Arch bars were removed once the patient reached a minimum of 6 weeks of healing and were satisfied with their post fixation occlusion.

Figure 1.

(A) Planned incision, (B) subcondylar fracture exposed, (C) fixated fracture, (D) incision closure.

Figure 2.

Depiction of the branching of the facial nerve including the planned incision site for the TMAP approach.

Results

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 52 patients who sustained subcondylar and condylar neck fractures were seen by the Oral and Maxillofacial surgery department at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Twenty-three of these patients were treated with open reduction internal fixation using miniplates and screws utilizing a transmasseteric anteroparotid approach to the fractures. Three patients were excluded from the study due to poor post-operative follow up or pre-existing complications, rendering a final sample of 20 patients. Of the surgically treated group, 14 patients had a concomitant mandible fracture and 4 patients had associated midface fractures (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subcondylar and Concomitant Fractures.

There was no evidence of facial nerve injury in any of the patients that were treated open through the transmasse- teric anteroparotid approach. Two cases of sialoceles and 3 parotidocutaneous fistulas were observed which were managed with antisialogogues and pressure dressings and all resolved within 2 weeks. Eighteen of the 20 patients achieved an MIO equal to or greater than 40 mm by 6 weeks post-operatively, 1 had 30 mm and another had 35 mm. Both of these 2 cases had poor compliance with post-operative physiotherapy. All of the patients in this study, regardless of concomitant facial fractures, achieved a re-establishment of their pre-injury occlusion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of Complications.

Discussion

Open reduction internal fixation of subcondylar fractures has grown significantly in popularity among practiced sur- geons since the introduction of plates and screws in max- illofacial trauma. Numerous studies have proven that these fractures can be treated closed. However, closed reduction becomes increasingly difficult as the degree of displace- ment becomes more severe and requires excellent patient cooperation with a post-operative rehabilitation program.

The closed technique is unable to address shortening of the ramus or significant angulations of the fractured segments. The indications for surgery can vary significantly among surgeons. The patients that met the indications for open surgical treatment of subcondylar fractures in the present study were those that presented with a significant dental malocclusion and were found to have displacement of the fractured segment between 10 and 45 degrees and/or 2 mm or greater loss of vertical ramus height measured on commuted tomography scans.[21,22,23]

We utilize the transmasseteric anteroparotid approach as it provides adequate access to the fractured segments with- out compromising any vital structures. No facial palsy occurred in this study, including transient facial palsy. Similar studies have shown a rate of facial nerve palsy of 7.5% to 17.2% with the retromandibular approach,[20,24] 14% to 33% with the pre-auricular approach,[1,25] and 8% to 16% with the submandibular/Risdon approach.[26,27]

The only relatively serious complications we observed were salivary fistulae/sialocele, due to the opening of the parotid capsule; though these all resolved with conservative management in a short period of time. Similar studies have shown a rate of sialocele/parotidocutaneous fistula of 2.3% to 7.3% with the retromandibular approach[20,24] and 5% to 22% with the pre-auricular approach.[1,25] No other compli- cations, including surgical site infection, plate breakage, hypertrophic scaring, hematoma, or Frey’s syndrome were experienced by participants in this study.

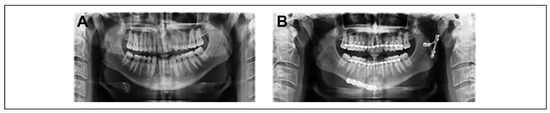

Lastly, the choice of osteosynthesis device is pivotal in providing excellent reduction and stable fixation at the fracture site. The quantity and quality of the bone, espe- cially of the condylar fragment, can make fixation delicate and difficult.[28] Some investigators have recommended 1 linear 4-hole plate at the posterior border of the condylar neck[20,29,30] sometimes in association with an anterior plate to increase the stability of the bone fixation.[31,32] Due to limited space, we advocate using a 6-hole lambda plate with the anterior limb functioning as an anti-rotational component (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

A, Pre-operative panorex demonstrating a right parasymphyseal and left subcondylar fracture. B, Post-reduction with a lambda plate at the left subcondylar fracture site.

Conclusions

We recommend the use of the transmasseteric anteroparo- tid approach as it provides for fast and direct access through a “nerve free” window[33] to the fractured segments with a relatively low rate of complications and morbidity.

IRB approval

University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center – 11058.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Croce A, Moretti A, Vitullo F, Castriotta A, Rosa DM, Citraro L. Transparotid approach for mandibular condylar neck and subcondylar fractures. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital.

- Morris C, Bebeau NP, Brockhoff H, Tandon R, Tiwana P. Mandibular fractures: an analysis of the epidemiology and patterns of injury in 4,143 fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Zachariades N, Mezitis M, Mourouzis C, Papadakis D, Spanou A. Fractures of the mandibular condyle: a review of 466 cases. Literature review, reflections on treatment and proposals. J Craniomaxillofac Surg.

- Bhagol A, Singh V, Kumar I, Verma A. Prospective evalua- tion of a new classification system for the management of subcondylar fractures. J Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, 1: 69(4), 1159.

- Santler G, Ka¨rcher H, Ruda C, Ko¨ le E. Fractures of the condylar process: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Lindahl, L. Condylar fractures of the mandible. I. Classifica- tion and relation to age, occlusion, and concomitant injuries of teeth-supporting structures, and fractures of the mandibular body. Int J Oral Surg.

- Spiessl, B. Rigid internal fixation of fractures of the lower jaw. Reconsr Surg Traumatol.

- Duan DH, Zhang Y, A meta-analysis of condylar fracture treatment. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi.

- Nussbaum ML, Laskin DM, Best AM. Closed versus open reduction of mandibular condylar fractures in adults: a meta- analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1087.

- Kyzas PA, Saeed A, Tabbenor O. The treatment of mandibular condyle fractures: a meta-analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg.

- Liu Y, Bai N, Song G, et al. Open versus closed treatment of unilateral moderately displaced mandibular condylar frac- tures: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.

- Al-Moraissi EA, Ellis E, 3rd. Surgical treatment of adult mandibular condylar fractures provides better outcomes than closed treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Berner T, Essig H, Schumann P, et al. Closed versus open treatment of mandibular condylar process fractures: a meta- analysis of retrospective and prospective studies. J Craniomaxillofac Surg, 1404.

- Chrcanovic, BR. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment of mandibular condylar fractures: a meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Ellis E, 3rd, Simon P, Throckmorton GS. Occlusal results after open or closed treatment of fractures of the mandibular condylar process. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Zide MF, Kent JN. Indication for open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Imai T, Fujita Y, Motoki A, et al. Surgical approaches for condylar fractures related to facial nerve injury: deep versus superficial dissection. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1: 48(9), 1227. [CrossRef]

- Downie JJ, Devlin MF, Carton ATM, Hislop WS. Prospective study of morbidity associated with open reduction and inter- nal fixation of the fractured condyle by the transparotid approach. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Yang L, Patil PM. The retromandibular transparotid approach to mandibular sub-condylar fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Ellis E, 3rd, McFadden D, Simon P, Throckmorton G. Surgical complications with open treatment of mandibular condylar process fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 9: 58(9).

- MacLennan, WD. Fractures of the mandibular condylar process. Brit J Oral Surg.

- Haug RH, Assael LA. Outcomes of open versus closed treat- ment of mandibular fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 3: 59(4).

- Baker AW, McMahon J, Moos KF. Current consensus on the management of fractures of the mandibular condyle. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Van Hevele J, Nout E. Complications of the retromandibular transparotid approach for low condylar neck and subcondylar fractures: a retrospective study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesnaver A, Gorjanc M, Eberlinc A, Dovsak DA, Kansky, AA. The periauricular transparotid approach for open reduction and internal fixation of condylar fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Nikolic’ Zˇ S, Jelovac DB, Sˇabani M, Jeremic’ JV. Modified Risdon approach using periangular incision in surgical treat- ment of subcondylar mandibular fractures. Srp Arh Celok Lek, 2: PMID, 2965.

- Nam SM, Lee JH, Kim JH. The application of the Risdon approach for mandibular condyle fractures. BMC Surg, 2: 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier T, Pierre T, Gabriel M. Open reduction internal fixa- tion of low subcondylar fractures of mandible through high cervical transmasseteric anteroparotid approach. J Oral Max- illofac Surg, 2446.

- Haug RH, Assael LA. Outcomes of open versus closed treat- ment of mandibular subcondylar fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Hyde N, Manisali M, Aghabeigi B, et al. The role of open reduction and internal fixation in unilateral fractures of the mandibular condyle: a prospective study. Br J Oral Maxillo- fac Surg.

- Asprino L, Consani S, de Moraes M. A comparative bio- mechanical evaluation of mandibular condyle fracture plat- ing techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Tominaga K, Habu M, Khanal A, Mimori Y, Yoshioka I, Fukuda J. Biomechanical evaluation of different types of rigid internal fixation techniques for subcondylar fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1510.

- Narayanan V, Ramadorai A, Ravi P, Nirvikalpa N. Transmas- seteric anterior parotid approach for condylar fractures: expe- rience of 129 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2021 by the author. The Author(s) 2021.