Abstract

This study examined the integration of cultural accounting in the conservation of a traditional performing art called Bantengan in Malang Raya, Indonesia, that is rich in local wisdom and spiritual values. The study focused on exploring the values of local wisdom contained in Bantengan and analyzing accounting records in its financing, especially post-COVID-19 pandemic. Using a qualitative approach with an ethnomethodological paradigm, data were collected through observation, in-depth interviews, and documentation from the Sukopuro Bantengan Association. This study revealed the importance of accountability in the management and conservation of traditional arts to ensure transparency, sustainability, and relevance of cultural values in an ever-evolving social context. Accounting, often associated with technical aspects, in this context also reflects humanistic and cultural values. The findings of this study are expected to provide a new perspective in the field of cultural accounting, especially related to the conservation and development of traditional arts in Indonesia, as well as provide a useful framework for the management of cultural assets in other regions that have similar contexts.

1. Introduction

The public sector comprises a wide range of activities and services performed by the government or public institutions (Knies et al. 2024; Lapuente and Van de Walle 2020), both at the central and regional levels, with the main goal of meeting the needs of the community (Dick-Sagoe and Andraz 2020). In contrast to the profit-oriented private sector, the public sector focuses on public services (Papenfuß and Schmidt 2022). Public accounting is a technical system applied in the management of public funds, involving various government entities, public institutions, non-profit organizations, and state-owned enterprises (Bisogno and Donatella 2021; Sopanah et al. 2023a) with the aim of providing relevant and trustworthy financial information to support the management of public finances, including accountability, budget planning, and fulfillment of legal obligations. The role of public accountants includes government accounting and auditing, public finance consultants, and financial management (Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al. 2022; Saputra et al. 2021). Along with technological developments and changes in government, public accounting continues to evolve and adapt to improve efficiency and transparency in the public sector (Thi Thanh et al. 2020). Public sector accounting, therefore, serves an essential system to ensure accountability, transparency, and efficiency in the management of public funds through the provision of relevant and trustworthy financial information.

In the wide-ranging and varied context of the public sector, cultural accounting has emerged as a distinct field that plays an essential role in the conservation and management of cultural assets (Ferri et al. 2021; Jayasinghe et al. 2020). It not only focuses on the financial aspect alone but also takes into account the cultural values contained in these assets, such as historical buildings, art, and local traditions (D’Alpaos and Valluzzi 2020). As such, it becomes an integral part of public accounting, ensuring that cultural heritage is managed efficiently and reported with transparency in accordance with the principles of public accountability. This approach emphasizes the importance of maintaining cultural sustainability through responsible management while strengthening community identity in a broader context.

Cultural accounting, a branch of public sector accounting, focuses on managing and reporting the cultural assets and resources owned by public entities such as local governments and cultural institutions. Its primary goal is to protect and manage cultural heritage efficiently, including recording, measuring, and reporting assets such as historic buildings, art collections, and cultural events. Research in various countries, including Indonesia, has explored cultural asset management, cultural value assessment, and preservation strategies. Indonesia, with its rich cultural diversity, provides a unique context for this research, especially through the Bantengan art in Malang, which combines performing arts with local wisdom and serves as a cultural identity for the local community. This research aligns with the UN’s 2030 SDG sustainability agenda, which aims to foster intercultural understanding, tolerance, mutual respect, and an ethic of global citizenship and shared responsibility. The agenda recognizes the diversity of the world’s natural and cultural heritage, emphasizing that all cultures and civilizations contribute to and are essential drivers of sustainable development. By preserving cultural heritage, we can maintain world heritage that benefits broader communities, including economically.

In the context of cultural accounting, the traditional performing art ‘Bantengan’ in Greater Malang shows how local cultural assets are managed and conserved (Sawitri et al. 2024) Bantengan, which is rich in local wisdom values and functions as a cultural identity of the community, requires special attention in financial recording and reporting (Kompasiana 2022). The management of this performing art not only involves the conservation of its physical and non-physical forms, such as dance, music, and rituals, but also requires accounting strategies that are able to reflect the cultural values contained in it. By applying the principles of cultural accounting, the government and related institutions can ensure that Bantengan is not only maintained for its sustainability but is also recognized as an important part of cultural heritage that has significant economic and social values (Utami and Cindrakasih 2023).

Bantengan is one of the traditional art forms that develops in the Greater Malang region, East Java. It, as a performing art, combines dance, pencak silat, traditional music, and magical elements rooted in the local culture of the people of Malang. The name ‘Bantengan’ comes from the word ‘banteng’ which means buffalo or bull, which in this art is a symbol of strength, courage, and protection. Inseparably, it emanates from the history and traditions of the local community. It estimatedly began to develop since the Dutch colonial period as a form and a symbol of resistance to colonialism. It is often associated with traditional rituals related to spiritual powers; people believe that they can summon powerful protective spirits through Bantengan magical dances and rituals. Bantengan itself has several key elements that make it unique and distinctive, namely dance and movement, traditional music, ritual, and magic. The movements in Bantengan are based on pencak silat, with dancers usually wearing bull costumes depicting courage and strength. The dance is often accompanied by energetic and aggressive movements, reflecting a bull’s characteristics. The music that accompanies Bantengan usually consists of gamelan, kendang, gong, and other traditional musical instruments. This music not only regulates the rhythm of the dance but also serves to summon spiritual power. One of the important elements in Bantengan is the presence of magical rituals that are performed before and during the performance. In some cases, Bantengan dancers are believed to experience or trance, where bulls’ spirits are believed to possess them.

Bantengan is more than just an art form; it contains deep local wisdom values such as mutual cooperation, leadership, protection, and interconnectedness between humans and nature. The preparation and implementation of Bantengan usually involve the entire community, showing a strong spirit of togetherness and mutual cooperation. The bull in this art symbolizes a strong leader and protector of the community, reflecting the ideal leadership values in Javanese culture. This art also reflects the close relationship between humans and nature, where animals (bulls) are considered the embodiment of the forces of nature that must be respected.

Bantengan has an important role in the social and cultural life of the people of Malang. It is usually held in various traditional events, such as holiday celebrations, traditional ceremonies, or other social activities. It is more than just entertainment; it serves as a medium to conserve traditions and strengthen the cultural identity of the community. However, like many other traditional art forms, Bantengan faces challenges in maintaining its existence in the modern era. Urbanization, social change, and outside cultural influences have resulted in a decline in interest among the younger generation in traditional arts. For this reason, various efforts have been made to conserve Bantengan, including cultural education, art festivals, and integration with tourism. This is where the role of the government is very necessary in supporting the existence of bantengan art as a cultural heritage of the nation.

Bantengan is a valuable cultural heritage that reflects the people of Malang’s richness in culture and spirituality. Conserving and developing this art are important not only to maintain local identity but also to ensure that these cultural values remain relevant and passed on to future generations. Through a holistic and integrative approach, Bantengan is expected to continue to live and become a symbol of dynamic cultural power in modern society. Bantengan that develops in Malang Raya is not just a performing art but also a cultural heritage that is loaded with local wisdom and spiritual values. As a symbol of strength, courage, and protection, Bantengan reflects the close relationship between the community and the values that are upheld in their social lives. The conservation of this art is inseparable from the importance of accountability in its management and development.

In this context, accountability is essential to ensure that each aspect of Bantengan management conservation is performed with transparency and responsibility. This is in accordance with the theory expressed by Gray (1988), in which transparency and public accountability are very necessary. Accountability involves clear monitoring and reporting on the resources used, including funds, time (Mwesigwa 2020; Vian 2020) and community involvement (Ortega-Rodríguez et al. 2020; Tamvada 2020). It also ensured that the results contribute to the larger goal, which is to conserve cultural heritage and strengthen community identity (Schaaf et al. 2020; Sofyani et al. 2020). Without accountability, these conservation efforts can lose their direction, resulting in the misuse of resources (Castellino 2024) and ultimately threatening the continuity of Bantengan itself. The integration of the principles of accountability in the management of Bantengan not only strengthens transparency and public trust but also ensures that the cultural values contained in it continue to live and be relevant in an ever-evolving social context. This creates a system where Bantengan can be accounted for by the community so that this cultural heritage can continue to be an integral part of the identity of the people of Greater Malang.

Accountability is a fundamental concept in public administration, organizational management, and government that refers to the responsibility of individuals or entities to report, explain, and be accountable for their actions and decisions (Brummel 2021; Sopanah et al. 2023b). In the context of the public sector, accountability emphasizes not only transparent financial reporting but also the efficiency and effectiveness of public services (Furqan et al. 2020). According to Overman and Schillemans (2021) and Schillemans et al. (2020), accountability involves three main elements: accountability to the public (the ability to explain to the public), accountability within the organization (compliance with internal policies), and accountability to superiors (explanation of the achievement of goals).

Cultural Accountability is also important in the context of non-profit organizations and the public sector (Pärl et al. 2022), where transparency in the management of resources, such as cultural funds or heritage assets, is crucial (Bañuelos et al. 2021). It ensures that the organization or government is responsible for the maintenance and management of cultural assets in a way that reflects the values and interests of the communities served (Abhayawansa et al. 2021). By applying the principle of accountability, both in vertical and horizontal contexts, organizations and governments can increase transparency, minimize the risk of abuse of authority, and ensure that the goals and values of the organization or society are maintained and achieved effectively (Rusdianti and Sopanah 2023).

Bantengan art, a performing art rich in local wisdom values, is the primary focus of this study, particularly following its revival after the COVID-19 pandemic. This study employs a qualitative approach with an ethnomethodology paradigm to explore local wisdom values in Bantengan art and the accounting records related to its financing. The main objective of this study is to examine accounting practices in Bantengan art, focusing on the processes of recording and managing finances carried out by associations such as Paguyuban Sukopuro.

This study aims to highlight the importance of implementing bookkeeping, which, although often overlooked in small organizations, can provide significant benefits in maintaining financial transparency and accountability. By keeping accurate records, Bantengan associations can manage funds efficiently, ensuring that contributions from members or proceeds from performances are used for their intended purposes. While accounting is typically associated with technical aspects such as debits and credits, this study broadens its scope by emphasizing the humanistic and local aspects of cultural accounting. Moreover, this study seeks to demonstrate how accounting records not only support financial aspects but also aid in the preservation of Bantengan art by maintaining local wisdom values, such as harmony, togetherness, and control, which are central to this cultural practice. The study highlights its originality by providing a unique approach to cultural accounting practices, especially in the context of Bantengan art in Malang Raya. Unlike previous studies, which have tended to focus on the technical aspects of public accounting or cultural asset management (Carnegie and Kudo 2023; Ferri et al. 2021), this study explores financial records and fund management within traditional art communities that are steeped in local wisdom values.

Additionally, the research gap identified lies in the lack of attention to how the accounting process can support the preservation of traditional arts facing the challenges of modernization and urbanization. Previous studies have often highlighted cultural heritage in the form of physical assets, such as buildings or monuments, without considering the aspects of performing arts such as Bantengan. Therefore, this study offers a new contribution by exploring how simple, yet effective accounting records can strengthen the management of traditional arts, maintain cultural sustainability, and promote accountability in local arts communities.

This study is essential in addressing two main questions: (1) What are the values of local wisdom embedded in Bantengan art? and (2) How are accounting records implemented in financing the performances? These findings are expected to provide new perspectives in cultural accounting, particularly regarding the preservation and development of traditional arts in Indonesia, and to highlight the importance of synergy between accounting and cultural preservation, especially in the context of traditional performing arts in Indonesia.

2. Materials and Methods

This study applied a qualitative method with an ethnomethodological approach (Mlynar 2023). Data were collected through observation, interviews, and documentation focusing on the Sukopuro Bantengan Arts Association. Observations were conducted at the outset, immediately after identifying the research idea, directly within the Sukopuro community—both at the community location and during Bantengan art performances. Interviews took place after the research commenced, involving five informants who were highly knowledgeable and directly engaged with Bantengan art: the community leader, artists, government representatives, community representatives, and academic representatives. Details of some informants are presented in the following Table 1:

Table 1.

List of Informants of the Sukopuro Bantengan Association.

Furthermore, interviews were conducted face-to-face with informants using a semi-structured, in-depth approach (Table 2). The interview consisted of two primary questions, which were expanded into twenty-one specific questions, along with additional questions that emerged spontaneously during the interview process with the informants (Table 3).

Table 2.

List of Questions on the Values of Local Wisdom in Bantengan.

Table 3.

List of Questions about Accounting Recording in the Financing of Bantengan Performances.

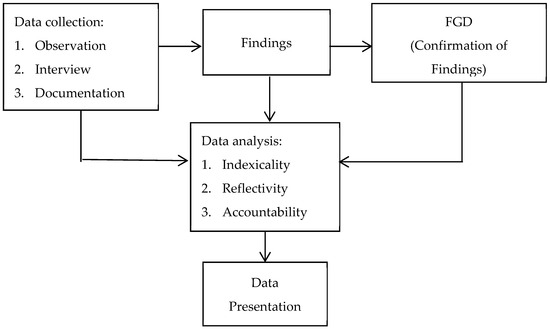

The next data collection method used was documentation, where the researcher documented the results of interviews and observations in the form of pictures, notes, and recordings. These data collection results were then discussed in a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) to obtain input and confirm findings related to the values of local wisdom in Bantengan art. Additionally, this study examined and verified accounting records related to financing Bantengan art performances. Data analysis was carried out using the indexicality, reflexivity, and accountability approaches and concluded with data presentation (Figure 1). The indexicality approach involved labeling interview responses to interpret the research results. The reflexivity approach facilitated a deeper exploration of meanings through stages that described the significance of local wisdom values implied by the indexicality results. Finally, the accountability approach reviewed and analyzed relational interactions within Bantengan art, which were then used to draw conclusions.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Results

Based on the research focus on the values of local wisdom embedded in Bantengan art and the accounting practices used in financing Bantengan performances, the following research results were obtained through intensive data collection, including in-depth interviews, documentation, and observation.

Data Collection Was Conducted Through Interviews

The interview results regarding the values of local wisdom in Bantengan art revealed various perspectives. For example, IB1 briefly explained that the Sukopuro Association was established on 22 May 2022, meaning it has been active for two years, with the primary aim of fostering harmony and strengthening unity between the performers and the community involved. The Sukopuro Association oversees 15 Bantengan groups throughout Sukopuro Village, each of which was established at different times—some as early as 2000. According to IB1, the purpose of the association is to create harmony and unity between the performers and the community. Bantengan is not a rivalry; as IB1 stated, the association only serves as a support. The presence of the association has created a more harmonious environment among the Bantengan groups, which were not as united before its establishment. When asked about economic objectives or legality, IB3 responded affirmatively, mentioning the Arts Identification Number.

According to IB1, Bantengan is a legacy passed down from the ancestors: “As an artist, I only continue this tradition”. He added, “As far as I know, Bantengan originated in the Singosari Kingdom or, some believe that it came from the Kanjuruhan Kingdom. The relief of Jago Temple explains how the performance was carried out in ancient times. In the past, Bantengan was just a performance. However, over time, the Bantengan performers became possessed, which was marked by changes in their behavior, resembling bulls, tigers, or monkeys. These three animal characters are integral to Bantengan. Bantengan symbolizes three powers: the bull as a symbol of strength, the tiger a symbol of honor, and the monkey as agility. Bantengan still exists today with these philosophies”. The history of the Sukopuro Bantengan Association began with the idea of gathering young men and women who used to be often chaotic due to the competition between the northern and southern blocks of residences. The formation of the Sukopuro Association has made their situation orderly and conducive to harmony. For the question “Bantengan involves more than just dancing, right? Or is there another term for it?” IB3 answered: each group has its own characteristics called Kembangan. Each region is different. There is Bantengan, which comes from the Singosari temple; there is also Mahesa Suro; and there is also Abangan in Batu City who wear red masks. There is also Dadung Ngawa in the forest. In Jabung, most of the Pencak movements consist of Bedhesan/monkey, Macanan/tiger, and Bantengan/bull, where the bull symbolizes the people, while Bedes/monkey comes to pit two people against each other. When the researchers asked about how many people participate in Bantengan performance, IB2 answered around 30 people: some inside the bull, some controlling the bull, and some serving as substitute performers in case someone is possessed/in a trance. There is also a handler. Normally, a Banteng team consists of seven people, which can perform different positions in turn.

Bantengan takes place by request/invitation. “Here there is a moment called the Ambal Warsa Paguyuban Sukopuro/Anniversary of the association, which is held once a year in May and everyone must be involved. Bantengan activities are carried out around the village or carnival to other places”, added IB2 for the question of whether there are Bantengan activities if there are no requests/invitations.

Bantengan is also famous for the term Mberot, which according to IB2 means rampaging or difficult to control. Why should there be Bantengan? IB1 answered that it aims mainly to maintain harmony and conserve the traditional art itself. If no one conserves it, it is possible that Bantengan will be recognized by other regions. Regarding the modernization in Bantengan and whether it is profitable or not, IB3 replied that it is true that Bantengan is undergoing modernization. This modernization has both positive and negative impacts. Positively, it helps the economy of the traders who sell during the performance event, while the negative is the deviation of the dancers from the originality of Bantengan itself. Fortunately, the Sukopuro Association still uses traditional musical instruments, not only Disc Jockey (DJ) music. Our participants package Bantengan music with both modern and traditional musical instruments. One event usually takes time from 9 am to 2 am. Because the trance during the performance cannot be controlled, each group is given 30 min to show its performance if there are many groups.

Regarding financial issues, the question began with how many rupiahs must be prepared if someone wants to invite a group to perform Bantengan. IB1 said that inviters only need to pay about IDR 2,000,000. Bantengan is now considered cheap because the artists are happy just to be fed with foods and cigarettes. This is what made the name of Bantengan destroyed. Therefore, the Sukopuro Association is targeting an additional amount of funding, even if it is small. Events that usually invite Bantengan, according to IB5, are circumcision, weddings, or Gebyakan events on the eve of Ramadan/fasting month. When the researchers added the question “For community self-funding, where does the money go?” IB3 said that some go to the group management, and some go to the dancers. The latter occurs in those with less education about Bantengan—those who deviate from the originality of Bantengan.

IB1 answered the question about preparations during the Bantengan performance, stating that one bunch of bananas must not be broken, and the offerings should include a variety of flowers such as three types of flowers (bunga telon), kenanga, and kantil, along with a coconut, peco bakal (a package consisting of flowers, betel leaves, etc.), eggs, a comb, glass, janur, brown sugar, kebaya, sewek, bamboo woven mat, rice, coffee, water, and a male chick, as well as badeg/fermented cassava soaking water. Additionally, some groups may use a cempluk (lamp) that must remain lit throughout the performance.

Regarding the question about the cost for a single performance, IB2 mentioned that it is around IDR 500,000 to IDR 600,000, and the chick needs to be purchased. IB2 added that whether the individual performers receive payment depends on the arrangement; if it is in their own village, the payment goes into the association’s fund, while performances outside may have a budget allocated for the players, with some of the money also going into the association’s fund. Essentially, it can vary.

The conclusion of this paragraph is that a single performance requires various traditional materials, such as bananas, flowers, a coconut, and a male chick, at a cost of around IDR 500,000 to IDR 600,000. When a group of Bantengan is asked to perform, the payment to the performers varies. If they perform in their own village, the money usually goes to the association’s fund, while if they perform outside, some of the money is used for the performers and some goes to the association’s fund. In essence, income from the performance is not always fixed and depends on the situation.

Regarding the existence of accounting records, IB2 answered that each group is different in making records. IB1 added that financial reports are also communicated through the group, detailing funds coming in and going out. The Sukopuro Association makes records (Table 4) as follows.

Table 4.

The 2024 “Sukopuro Bantengan Association” Financial Report.

Accounting records are an important aspect in the management of the Sukopuro Bantengan Association, despite the simple methods applied. Village officials support Bantengan with licensing affairs, IB4 said. IB4 expressed his gratitude for the maximum assistance by the village officials. Sukopuro at this moment has 15 active Bantengan groups, and there are also regular activities that have gained attention from the village government. Bantengan has many positive values, especially in terms of improving the economy of traders and harmony between residents. In the future, village officials will revive Bantengan as a model example.

4. Discussion

The Sukopuro Bantengan Association, which has been established for two years, plays an important role in reconciling and strengthening the unity between players and the community involved in Bantengan. By covering 15 Bantengan groups in Sukopuro Village, in terms of social goals, it has succeeded in creating a more conducive atmosphere among the groups, which were previously less harmonious. It also has economic and legal aspects through the Arts Registration Number, which supports the sustainability and official recognition of Bantengan activities.

The values of local wisdom are reflected in the origins, traditions, and activities of the Bantengan art. Bantengan is an ancestral heritage originating from the Singosari or Kanjuruhan Kingdom, with evidence of its existence seen in the reliefs of Jago Temple. Bantengan is not only entertainment but also contains philosophical values. The three dominant animals in this art are the bull, the tiger, and the monkey, each of which symbolizes strength, honor, and agility, respectively. In addition, the history of Bantengan in Sukopuro shows that this art has succeeded in reducing competition between youth groups and creating harmony through the establishment of the Sukopuro Bantengan Association and the preservation of local culture. Each region has its own characteristics of Bantengan, called “Kembangan”, which reflects the richness of local traditions and symbolism.

A single performance of Bantengan usually involves around 30 people. Each Banteng is played by four people, two of whom play as backups in case of possession. A handler is tasked with controlling the situation. Although there are players who often play the Banteng, all members have been taught to take turns. The formal standard for one Banteng involves seven people, and the number of players depends on how many Banteng appear in the show.

The phenomenon of “Mberot”, which means rampaging bull, is also a famous part of this performance. Bantengan is important to maintain harmony and prevent the art itself from being recognized by other regions. Bantengan has undergone modernization, which brings economic benefits, especially for traders. However, this modernization also has negative impacts, such as the reduction of the art’s authenticity. The Sukopuro Bantengan Association has been trying to maintain a balance between tradition and modernization by continuing to use traditional musical instruments beside the existence of modern elements such as DJ music. The duration of the performance can vary. At certain events, performance duration is usually limited.

Bantengan performances are usually held by request for circumcision or wedding celebrations. There is also an annual event called Ambal Warsa, which involves all members of the Sukopuro Bantengan Association. Since Bantengan is sometimes considered trivial due to minimal compensation, the Sukopuro Bantengan Association tries to maintain its dignity by providing cash contributions. However, there are also practices that stray from the original tradition, such as hiring dancers who raise funds from community donations. Each Bantengan group has a different accounting recording method. The Sukopuro Bantengan Association uses a systematic approach for record-keeping. Its financial reports, including funds received and spent, are also shared within the group for transparency.

The Sukopuro Village Government strongly supports Bantengan, especially in terms of licensing and facilitation of activities. It also pays attention to the positive values of Bantengan, such as its contribution to improving the economy of local traders, strengthening relations between residents, and strengthening local cultural identity. The Village Government plans to continue to revive and make Bantengan a model example for other communities. The East Java provincial government (Kominfo 2023) also expressed similar sentiments, supporting the maintenance and preservation of Bantengan art. The Deputy Governor of East Java stated that this art form is being developed as a promotion for East Java tourism.

Bantengan plays a very important role in maintaining harmony, conserving culture, and strengthening community identity. In facing the challenges of modernization, artists and communities with the support of the village government and local communities continue to make conservation efforts. This research provides in-depth insights into the dynamics and complexities surrounding Bantengan art, highlighting the uniqueness of Indonesia’s local culture. It aligns with the UN’s 2030 SDG sustainability agenda, which aims to foster intercultural understanding, tolerance, mutual respect, and an ethic of global citizenship and shared responsibility. The agenda recognizes the diversity of the world’s natural and cultural heritage, emphasizing that all cultures can contribute to sustainable development.

Ethnomethodology includes three basic concepts: indexicality, reflexivity, and accountability (Handayani et al. 2021). Indexicality refers to the effort to understand verbal expressions and body language that appear in interactions between individuals or communities. This concept allows members to interpret and interact in certain situations by contextualizing the appropriate sentence elements without destroying the existing order. Therefore, ethnomethodology is required to adjust to the perspective of members in understanding reality, not to impose the views of researchers.

Reflexivity is an effort by members to maintain their perceptions of social reality (Alejandro 2020). When someone acts based on a certain perception, he not only builds but also maintains the reality he believes in. If the action does not match the expected reality, members will act reflexively to maintain their initial perceptions, so that order is created in the social world.

Table 5 shows the results of the interviews conducted regarding indexicality and reflexivity in the Sukopuro Bantengan Association.

Table 5.

Indexicality and Reflexivity.

Accountability refers to the way members report, describe, analyze, or criticize a particular situation to explain its causes. This concept encompasses various forms of communication used to explain actions and situations. This study examines the existence and role of Bantengan in the Sukopuro Bantengan Association. The primary difference between this study and previous research lies in the focus of the study. Previous studies have concentrated more on the technical aspects of public accounting and general cultural asset management, often emphasizing financial governance related to arts organizations and cultural heritage without considering deeper cultural aspects. In contrast, this study highlights the importance of preserving the cultural heritage of Bantengan art, which holds historical and philosophical significance. It also examines how accounting practices are applied in financing Bantengan art activities, incorporating values of local wisdom, such as harmony, mutual cooperation, and transparency in fund management. This demonstrates a notable difference in integrating cultural aspects with accounting practices that are relevant to the local community context.

5. Conclusions

Bantengan, as one of Indonesian cultural heritages, more than being merely entertainment, serves as a means of conserving local wisdom values such as harmony, togetherness, and tolerance. Through an ethnomethodological approach, this study reveals how these values are manifested in daily practices by various Bantengan associations, such as the Sukopuro Bantengan Association, which is the focus of this study. The Sukopuro Association is found to have a unique way of reflecting local wisdom values through symbolism (indexicality), the application of these values in daily life (reflexivity), and accountability. In the midst of modernization that presents challenges for the conservation of traditional values, efforts to conserve and innovate continue to be carried out by the Bantengan communities with support from the village government and local communities. However, this study also identified challenges in financial reporting, particularly concerning traditional and ritual items, as well as Bantengan art tools owned by the Sukopuro Association. Uncertainty in valuing these items often hinders accurate recording, as these items possess not only material value but also significant symbolic value. Additionally, there is a lack of adequate accounting knowledge for estimating the value of these art tools.

In addition, this study also reveals that accounting records in Bantengan financing are carried out simply while maintaining transparency. Although the records do not follow formal accounting standards, each association tries to record income and expenses in a way that is easy for its members to understand. Overall, this study provides in-depth insights into how Bantengan plays a role in maintaining harmony, conserving culture, and strengthening community identity. This study also emphasizes the importance of cultural accounting in managing and reporting cultural assets, as well as the importance of conserving traditional arts as part of efforts to maintain local wisdom values. It is expected that the government can play an active role in supporting the promotion of Bantengan traditions and traditional arts. This can be achieved by facilitating licensing, providing financial recording training, and supporting performances at national and international levels. The art of Bantengan is also a significant driver of the community’s economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., A.H., S.B. and I.S.R.; methodology, A.S. and A.H.; software, A.S. and I.S.R.; validation, A.S., A.H. and I.S.R.; formal analysis, A.S., A.H., S.B. and I.S.R.; investigation, A.S., A.H., S.B. and I.S.R.; resources, A.S., A.H., S.B. and I.S.R.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., A.H., S.B. and I.S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.S., I.S.R.; visualization, A.H.; supervision, A.H. and S.B.; project administration, I.S.R.; funding acquisition, A.S. and I.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ana Sopanah appreciates the financial support from a Grant-in-Aid for Research provided by the Indonesia Ministry of Education, contract number 020/SP2H/PT/LL7/2024.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are obtained from the Sukopuro Bantengan associations and are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abhayawansa, Subhash, Carol A. Adams, and Cristina Neesham. 2021. Accountability and governance in pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals: Conceptualising how governments create value. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 34: 923–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, Audrey. 2020. Reflexive discourse analysis: A methodology for the practice of reflexivity. European Journal of International Relations 27: 150–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos, Jaione Korro, Álvaro Rodríguez Miranda, José Manuel Valle-Melón, Ainara Zornoza-Indart, Manuel Castellano-Román, Roque Angulo-Fornos, Francisco Pinto-Puerto, Pilar Acosta Ibáñez, and Patricia Ferreira-Lopes. 2021. The Role of Information Management for the Sustainable Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 13: 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogno, Marco, and Pierre Donatella. 2021. Earnings management in public-sector organizations: A structured literature review. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 34: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummel, Lars. 2021. Social Accountability Between Consensus and Confrontation: Developing a Theoretical Framework for Societal Accountability Relationships of Public Sector Organizations. Administration & Society 53: 1046–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, Garry D., and Eiichiro Kudo. 2023. Whither monetary values of public cultural, heritage and scientific collections for financial reporting purposes. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 35: 192–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellino, Joshua. 2024. Colonial Crime, Environmental Destruction and Indigenous Peoples: A Roadmap to Accountability and Protection. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Beatriz, Serena Santis, and Marco Bisogno. 2022. Public-sector Financial Management and E-government: The Role Played by Accounting Systems. International Journal of Public Administration 45: 605–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alpaos, Chiara, and Maria Rosa Valluzzi. 2020. Protection of Cultural Heritage Buildings and Artistic Assets from Seismic Hazard: A Hierarchical Approach. Sustainability 12: 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick-Sagoe, Christopher, and Jorge Miguel Lopo Gonçalves Andraz. 2020. Decentralization for improving the provision of public services in developing countries: A critical review. Cogent Economics & Finance 8: 1804036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, Paolo, Shannon I. L. Sidaway, and Garry D. Carnegie. 2021. The paradox of accounting for cultural heritage: A longitudinal study on the financial reporting of heritage assets of major Australian public cultural institutions (1992–2019). Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 34: 983–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furqan, Andi Chairil, Ratna Wardhani, Dwi Martani, and Dyah Setyaningrum. 2020. The effect of audit findings and audit recommendation follow-up on the financial report and public service quality in Indonesia. International Journal of Public Sector Management 33: 535–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Sidney J. 1988. Towards a Theory of Cultural Influence on the Development of Accounting Systems Internationally. Abacus 24: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, Nur, Unti Ludigdo, Rosidi, and Roekhudin. 2021. The Concept Of Shiddiq In Financial Accountability: An Ethnomethodology Study Of Boarding School Foundation. International Journal of Accounting and Business Society 29: 63–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, Kelum, Pawan Adhikari, Simon Carmel, and Ana Sopanah. 2020. Multiple rationalities of participatory budgeting in indigenous communities: Evidence from Indonesia. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 33: 2139–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knies, Eva, Paul Boselie, Julian Gould-Williams, and Wouter Vandenabeele. 2024. Strategic human resource management and public sector performance: Context matters. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 35: 2432–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominfo. 2023. Wagub Jatim, Emil Dardak Apresiasi Komunitas Overlanding Indonesia Gelar Budaya Bantengan di Malang. Available online: https://kominfo.jatimprov.go.id/berita/wagub-jatim-emil-dardak-apresiasi-komunitas-overlanding-indonesia-gelar-budaya-bantengan-di-malang (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Kompasiana. 2022. Mempertahankan Eksistensi Bantengan Sebagai Identitas Budaya Lokal Kota B. Available online: https://www.kompasiana.com/sharontambotto2404/6294bb3e53e2c3457b796b73/mempertahankan-eksistensi-bantengan-sebagai-identitas-budaya-lokal-kota-b (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Lapuente, Victor, and Steven Van de Walle. 2020. The effects of new public management on the quality of public services. Governance 33: 461–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynar, Jakub. 2023. Harold Garfinkel and Edward Rose in the early years of ethnomethodology. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 59: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwesigwa, David. 2020. Accountability: A necessity to pro-poor service delivery in Municipal Councils in Uganda. Journal of Governance and Accountability Studies 1: 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Rodríguez, Cristina, Ana Licerán-Gutiérrez, and Antonio Luis Moreno-Albarracín. 2020. Transparency as a Key Element in Accountability in Non-Profit Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 12: 5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, Sjors, and Thomas Schillemans. 2021. Toward a Public Administration Theory of Felt Accountability. Public Administration Review 82: 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenfuß, Ulf, and Christian Arno Schmidt. 2022. Valuation of sector-switching and politicization in the governance of corporatized public services. Governance 36: 1103–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärl, Ülle, Elina Paemurru, Kristjan Paemurru, and Helen Kivisoo. 2022. Dialogical turn of accounting and accountability integrated reporting in non-profit and public-sector organisations. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 34: 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdianti, Imanita Septian, and Ana Sopanah. 2023. Mengenal Akuntansi Sektor Publik dan Perkembangannya. Surabaya: Scopindo Media Pustaka. [Google Scholar]

- Saputra, Komang Adi Kurniawan, Bambang Subroto, Aulia Fuad Rahman, and Erwin Saraswati. 2021. Financial Management Information System, Human Resource Competency and Financial Statement Accountability: A Case Study in Indonesia. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 8: 227–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, Ummul Khasanah, Ishak Bagea, Ria Kristia Fatmasari, and Pande Wayan Renawati. 2024. Cultural Semiotics Analysis of Traditional Bantengan Art: Exploring Function, Symbolic Meaning, Moral Significance, and Existence. RETORIKA: Jurnal Ilmu Bahasa 10: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, Marta, Caitlin Warthin, Lynn Freedman, and Stephanie M. Topp. 2020. The community health worker as service extender, cultural broker and social change agent: A critical interpretive synthesis of roles, intent and accountability. BMJ Glob Health 5: e002296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillemans, Thomas, Sjors Overman, Paul Fawcett, Matthew Flinders, Magnus Fredriksson, Per Laegreid, Martino Maggetti, Yannis Papadopoulos, Kristin Rubecksen, Lise Hellebø Rykkja, and et al. 2020. Understanding Felt Accountability. Governance 34: 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyani, Hafiez, Hosam Alden Riyadh, Heru Fahlevi, and Lorenzo Ardito. 2020. Improving service quality, accountability and transparency of local government: The intervening role of information technology governance. Cogent Business & Management 7: 1735690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopanah, Ana, Harnovinsah, and Riza Bahtiar Sulistyan. 2023a. Madura Indigenous Communities’ Local Knowledge in the Participating Planning and Budgeting Process. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Bisnis 18: 163–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopanah, Ana, Khojanah Hasan, Satya Karyani Putra, and Imanita Septian Rusdianti. 2023b. Akuntabilitas Publik Organisasi Nirlaba. Surabaya: Scopindo Media Pustaka. [Google Scholar]

- Tamvada, Mallika. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and accountability: A new theoretical foundation for regulating CSR. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Thanh, Phuong-Nguyen, Hai-Phan Thanh, Tung-Nguyen Thanh, and Tien-Vo Thi Thuy. 2020. Factors affecting accrual accounting reform and transparency of performance in the public sector in Vietnam. Problems and Perspectives in Management 18: 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, Muherni Asri, and RR Roosita Cindrakasih. 2023. Struktural Functionalism sebagai Proses Transmisi Kesenian Bantengan Kota Batu. Jurnal Komunikasi Nusantara 5: 284–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vian, Taryn. 2020. Anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in health: Concepts, frameworks, and approaches. Glob Health Action 13: 1694744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).