Abstract

The article is aimed at increasing the probability of successful IT project completion by identifying the sources of 105 universal risks as well as establishing cause-and-effect relationships between these risks. The article presents the results of an analysis of 105 risks relevant to IT projects; five of them are commercial risks, 45 are compliance risks and 55 are project risks. Risk analysis was carried out using the 5Why, SWIFT and Harrington coefficients. Based on the results of the analysis, the root causes initiating the onset of risks were identified, such as the user, customer, project manager, project team, subcontractor and competitor. Moreover, it was found that the share of the users in the total number of risk sources is 2%, 15% for the customer, 43% for the project manager, 36% for the project team, 2% for the subcontractor and 2% for the competitor. The article also shows models of cause-and-effect relationships of compliance and project risks, presents the results of assessing the risks occurrence probability and their possible impact in cases of materialization, and establishes the most likely and dangerous scenarios in IT projects. The results obtained allowed the development of a criterion to assess the management maturity of a contractor (executor, supplier) planning to develop an computer program as part of an IT project.

1. Introduction

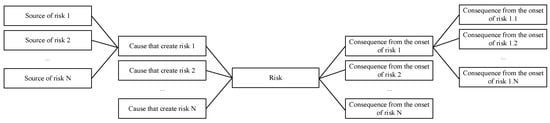

Analysis of scientific papers has shown that risk in IT projects are generally understood as a probable event derived from particular sources and can lead to certain consequences and have a negative and/or positive impact on the planned project goals (Lee and Baby 2013; Brandas et al. 2012; Paladino et al. 2009; Mishra et al. 2014; Aven 2012; Beer et al. 2015; De Bakker et al. 2014; Luckmann 2015). Causes that create risk are usually understood as conditions that have the potential to create probable events, sources of risk as objects that create probable events, and consequences from the onset of risk as circumstances that arise from risk materialization (Nikolaenko 2018b). The risk structure model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Risk structure—risk, causes that create risk, sources of risk and consequences from the onset of risk.

According to the general rule of the international set of best practices for project management outlined in the PMBOK Guide®, a project must be considered a unique work process with a fixed start date and end date (PMBOK Guide® 2017). In this regard, an IT project must be understood as a unique process with start and end dates for the execution of work that is aimed at creating an IT result, i.e., a result designed to ensure the functioning of electronic computers and other digital devices (Keil et al. 2018).

Risk management in IT projects is one of the management areas that can significantly increase the chances of successfully achieving project goals; this is confirmed by numerous studies (O’Neill 2018; Bushuyev and Wagner 2014; Backlund et al. 2014; Gładysz and Kuchta 2022; Sidorov and Senchenko 2020). For example, studies conducted by The Standish Group in 50,000 IT projects have shown that the material damage resulting from the occurrence of one negative risk is estimated at an average of $1000 (The Standish Group 2014). A thorough analysis of the reasons for the onset of negative risks enabled the determination that these material losses could have been avoided by a preventive impact on negative risks. Moreover, The Standish Group experts note in their studies that one preventive measure would not cost more than $1.

The need for risk management in IT projects is also confirmed by the results of research by Nikolaenko (Nikolaenko 2018b). In particular, scientists have found that any IT project, regardless of its size, complexity, duration, type and management methods, is exposed to 105 risks: five of them are commercial risks, 45 are compliance risks and 55 are project risks. (Nikolaenko 2022). It should be noted that while analyzing 447 IT organizations, it was established that the cumulative material damage from the occurrence of 363 compliance risks amounted to more than $4 million, where the damage of one compliance risk occurrence averaged $12,000. Compliance risks are probable events caused by the possibility of violating the rules stipulated by current legislation, standards and codes of conduct, where the consequences of these violations can manifest themselves in the form of legal sanctions from regulatory and supervisory authorities, industry associations as well as persons whose rights and interests have been violated (ERP 2017; ISO 2018).

In order to increase the likelihood of successful completion of IT projects, this article presents the results of a 105 risk analysis.

To achieve this goal, the authors of this article solved the following tasks:

- Sources of 105 risks relevant to IT projects were identified.

- Models of cause-and-effect relationships between universal compliance and project risks have been created.

- A criterion for assessing the management maturity of a contractor (performer, supplier) planning to develop a computer program within an IT project has been developed.

It should be noted that these risks are universal since their materialization is relevant to any IT project. Special risks, i.e., risks that may occur in a private IT project, are not included in the list under study.

2. Background

A project can only be considered successful when the planned requirements are met, stakeholder expectations are satisfied, and the planned goals are achieved (Powell and Klein 1996). It must be emphasized that achieving the planned results in project activities is a difficult task. This statement is confirmed by Ewusi-Mensah K. and Przasnyski Z.H.’s study results, which proved that about 35% of projects are terminated before their goals are achieved (Ewusi-Mensah and Przasnyski 1991). Scientists note that especially dangerous are those projects that, going beyond the planned budgets and schedules, continuously absorb valuable resources but, despite this, do not achieve their goals. The data obtained allows Ewusi-Mensah K. and Przasnyski Z.H. to conclude that project managers and project teams do not fully understand the problems they may encounter in the process of project implementation and how these problems need to be dealt with. Cule P., Schmidt R., Lyytinen K., and Keil M. in their writings argue that failure to achieve project goals is a result of the fact that project managers and project teams do not take the necessary measures to influence risks (Cule et al. 2000). Vujovic V., Dinic N. and other scientists claim that risk management is a key factor that ensures project success (Vujovic et al. 2020). Perez-Apaza F., Ramirez-Valenzuela A. and Peraz-Apaza J.D. note that the constant improvement of processes and risk management methods can significantly reduce the number and impact of problems occurring in projects (Perez-Apaza et al. 2021).

Risk management in IT projects is a set of principles, processes and methods that seek to assess and eliminate the most dangerous computer and project risks (Ropponen and Lyytinen 2000). Risk management is one of the most important competencies of IT project managers and teams, through which they can eliminate possible threats and risks in advance, thus increasing the chances of successful achievement of planned goals. Heemstra F.J. and Kusters R.J. note in their works that risk assessment and prevention lower the likelihood of large-scale disruptions during the development of software and also reduce the duration of IT projects that create software for computers (Heemstra and Kusters 1996). Odeh A., El-Hassan A. and other scholars have noted that the use of special methods for determining maturity in IT projects, such as CMMI or PMMM, can not only identify strengths and weaknesses of management, but also increase the loyalty of potential customers who seek to conclude contracts with reliable contractors (contractors, suppliers) (Odeh et al. 2021; Hutabarat et al. 2021).

Inefficient use or absence of risk management in IT projects is accompanied by constant «fire fighting», stress, uncertainty, repeated breakdowns of schedules and their revisions, as well as frequent lawsuits (Phelps 1996). Analyzing similar problems, Phan D., Vogel D. and Nunamaker J. came to the conclusion that IT projects can arise, both technical and managerial problems (Phan et al. 1998). This conclusion is confirmed by studies by Addison T. and Vallabh S., who found that IT projects may materialize about 14 project risks directly related to the management of IT projects and the creation of software code (Addison and Vallabh 2002). Stevens K. J. and Fowell S. identify 11 current risks for IT projects (Stevens and Fowell 2003). Sumner M. highlights 16 universal risks that can materialize during the implementation of the IT project (Sumner 2000).

In addition to the above, it is necessary to mention the results of the analysis of 447 ITorganizations conducted by Nikolaenko V.S. has established that any IT project, regardless of its scale, complexity, or duration, is exposed to 105 risks, of which five are commercial risks, 45 are compliance risks and 55 are project risks (Nikolaenko 2018a). A retrospective analysis of the scientific literature showed that the list of risks compiled by Nikolaenko V.S. at the time of writing this article is the most comprehensive and complete. Therefore, identifying sources for these risks and establishing cause-and-effect relationships between them is an urgent scientific and practical task, the solution to which should significantly contribute to increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of risk management in IT projects.

3. Methodology

The analysis of 105 risks relevant to IT projects was carried out using the 5Why, SWIFT and coefficients of the Harrington Verbal-Numeric School (Harrington coefficients).

Let us consider the application of these methods to the scope of the tasks in more detail.

The 5Why method is a method focused on the identification of risk sources (Wijayanti et al. 2022). The method was first proposed by Toyoda in order to increase the quality of Toyota products. Subsequently, the method began to be applied in other areas. For example, 5Why is often practiced in lean manufacturing, Kaizen, Six Sigma, and IT (Shirinkina et al. 2022; Sahu et al. 2022). The essence of the method is to consistently ask the question: «Why does the risk occur?». If the root cause is not established, then the same question is asked again to consider the answers received. The process is repeated until the source of the risk is identified. Note that when using 5Why, risks that were not previously identified can be identified, and this is an indisputable advantage of the method.

The next method used to analyze 105 risks was the Structured What If Technique (SWIFT) (Card et al. 2012). To deal with risks, SWIFT uses a set of phrases such as «What if…?», «What will it lead to… ?», «What happens if… ?», «Can anyone… ?», «Can anything… ?». These phrases help project teams not only identify sources of risk but also develop scenarios for the possible development of events in their projects.

To assess the probability of risks occurrence and the possible impact from their materialization, this article used a qualitative assessment and Harrington coefficients (Merna and Al-Thani 2008). Examples of Harrington coefficients for assessing the degree of influence and the degree of probability are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Harrington coefficients for assessing the possible impact of risk in the event of its materialization.

Table 2.

Harrington coefficients for assessing the probability of risk materialization.

10 respondents were chosen for expert evaluation of probability and impact. All respondents had a professional education and at least 4 years’ experience in the field of information technology. It should be noted that this number is due to two factors: first, the verification of expert assessments; and second, the possibility of obtaining more reliable estimates (Nikolaenko 2016). More detailed information on respondents’ competencies is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Information on respondents’ competencies.

To assess the probabilities of universal risks materialization and their possible impact in the event of their occurrence, the Harrington coefficients were used. Each expert presented three types of assessment for each universal risk: optimistic, most probable (realistic) and pessimistic. The obtained estimates were substituted into Formulas (1) and (2).

where , and —optimistic, most probable (realistic) and pessimistic risk materialization probability assessments; , and —optimistic, most probable (realistic) and pessimistic assessments of possible impact in case of risk; —calculated risk materialization value; —calculated value of the possible influence in case of risk.

Further, for each risk, the arithmetic mean of the probability of the risk materialization and the possible impact in the event of its occurrence were calculated according to Formulas (3) and (4).

where N—expert opinions number.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Risk Analysis Using the 5Why Method

In the process of identifying risk sources using the 5Why method, it was found that the sources are the stakeholders of the IT project, such as the user, customer, project manager, project team, subcontractor (co-executor), and competitor. It should be noted that according to the PMBOK Guide® international code of the best project management practices, project stakeholders are understood to be individuals and/or legal entities that are actively involved in the project or whose interests may be affected during the implementation of the project or upon its completion (PMBOK Guide® 2017).

The results of the analysis of 105 risks relevant to IT projects using the 5Why method are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sources of IT project risks.

Depending on the specifics of the implementing IT projects and creating programs process, the stakeholders may also include the product manager, project sponsor, contractor (performer, project owner, general contractor, supplier), etc. In particular, the product manager in the field of information technology is a specialist who manages the life cycle of IT products by organizing their creation, market launch, promotion, sales, support, development and withdrawal from the market (Petroșanu et al. 2022). The project sponsor (project curator) is a senior manager who oversees the IT project on the contractor’s (executor) part, provides overall control, and also supports the project team with material, human, financial and other resources (Martínez et al. 2021).

Depending on the customers task, the interested party of the project, which assumes obligations to perform certain work to create a program and/or provide paid IT services, is called a contractor (performer, supplier, general contractor, etc.). The term «project owner» can also be found in the literature (Wiegers and Beatty 2013). It should be noted that if the contractor involved other persons (subcontractors, co-executors) in the performance of his obligations, then in this case he will act as a general contractor (general contractor). Given this circumstance and also the fact that the project manager most often acts on the project owner’s side, it seems possible to combine sources of risk, such as the project manager, the project team and the subcontractor, into one source—the contractor. Therefore, in this case, the contractor’s share of the total number of risk sources will be 76%.

This circumstance clearly demonstrates the importance of assessing the contractor from the standpoint of risk management, because if a contract is signed with a contractor who does not carry out preventive actions on 105 risks, then the likelihood of material damage during the program’s development increases significantly.

4.2. Results of Risk Analysis Using the SWIFT Method

The list of 105 risks relevant to IT projects can be divided into commercial, compliance and project risks.

The commercial risks of IT projects are understood as any potential threats that may prevent interested parties from making a profit from the operation of the created programs. For example, the actions of competitors, piracy and/or the presence of substitute goods on the IT market can adversely affect the commercial potential of computer programs developed within the IT project framework (Table 5).

Table 5.

Commercial risks of IT projects.

Despite its small percentage of the total risks—only 4.7%—one commercial risk materialization can offset all the resources expended and the project team’s efforts, causing catastrophic material damage. First of all, this is due to the fact that commercial risks most often occur when the program creation is in the last phases of the project life cycle.

Next, we analyze the compliance risks of IT projects. It is worth noting that the first formal consolidation of the compliance risk management principles took place on 29 April 2005, when the Basel Committee published the document «Compliance and Compliance-Function in Banks» (Basel Committee 2005). According to the opinion of the Basel Committee, the main risk management tool in the field of compliance is the Code of Corporate Conduct, which sets out the norms of behavior for employees when interacting with clients, colleagues, counterparties, supervisory authorities, and other persons that employees encounter in the course of performing their professional duties. For example, the Code formalizes the rules for accepting and giving gifts, for counteraction to bribery and corruption, for legalization of proceeds from crime, etc.

T. Merna and F. Al-Thani in their writings note that the emergence of compliance risks is a rather rare occurrence; however, the materialization of such a risk is a sufficient condition for causing significant material damage (Merna and Al-Thani 2008). These risks come from the customer, the contractor, the exclusive right to the result of intellectual activity, the subcontractor, property, crime and the external compliance environment (Table 6).

Table 6.

Compliance risks of IT projects.

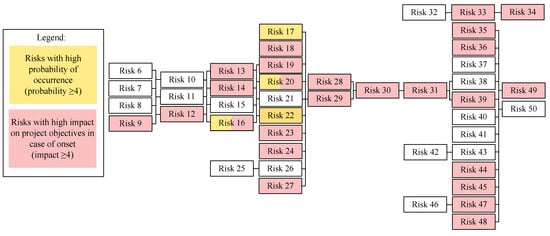

Compliance risk analysis of IT projects using the SWIFT method showed that these risk events have cause-and-effect relationships. For example, if the contractor does not fulfill his obligations under the contract, this will lead to a deception of the customer’s expectations. If this happens, the customer will refuse to accept and pay for the work performed by the contractor. In worst case scenarios, a dispute between the customer and the contractor will lead to litigation. The model of cause-and-effect relationships for compliance risks in IT projects is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Model of cause-and-effect relationships for IT project compliance risks.

The construction of cause-and-effect relationships between compliance risks was carried out based on answering the question “What if… ?”. As an example, consider the process of answering the question, “What happens if the requirements change during the implementation of the project?”. The answers were “The contractor (performer) will not fulfill its obligations under the contract” and “The work performed (service rendered) will not meet the customer’s expectations”. Thus, between the risks of changing requirements during the course of the work (Risk 20), the risk that the contractor will not fulfill its obligations under the contract (Risk 29), and the risk that the work performed will not meet the expectations of the customer (Risk 30), causal relationships have been established.

The analysis of the cause-and-effect relationships of IT project compliance risks established:

- Initiating risks, whose materialization leads to subsequent risk occurrence, are risk events associated with the customer. In particular, «the risk that the customer does not have a corporate culture, employees and experience in conducting activities in a single information space»; «the risk that the customer will not have well-functioning corporate procedures for information interaction»; «the risk that there are no key and qualified specialists on the customer’s side»; and «the risk that there will be customer restructuring». In this regard, it is logical to assume that in order to reduce the likelihood of the possible subsequent occurrence of compliance risks, it is necessary to take actions in advance to prevent the above probable events.

- Compliance risks of the external environment, such as «the risk of changing the norms of the current legislation»; «the risk of violating the norms of the current legislation»; and «the risk of fines for violating the current legislation» are not included in the general causal relationship of the model. This circumstance can be explained by the indirect influence of these compliance risks on the process of implementing IT projects and the progress of creating programs.

- The risk that the work performed (service rendered) will not meet the customer’s expectations is the most dangerous position in the scenario.

- For IT projects, in the negative scenario development, three outcomes are relevant: receiving a fine for violating the current legislation; lawsuit from the customer (contractor); lawsuit from a subcontractor.

Let us analyze project risks using the SWIFT method. Project risks are those whose materialization affects one goal of the project or a combination of them (content, duration, cost and quality of the project). These risks become relevant due to the actions (or inactions) of project managers and members of project teams, as well as the equipment, technologies and equipment used (Table 7).

Table 7.

IT project risks.

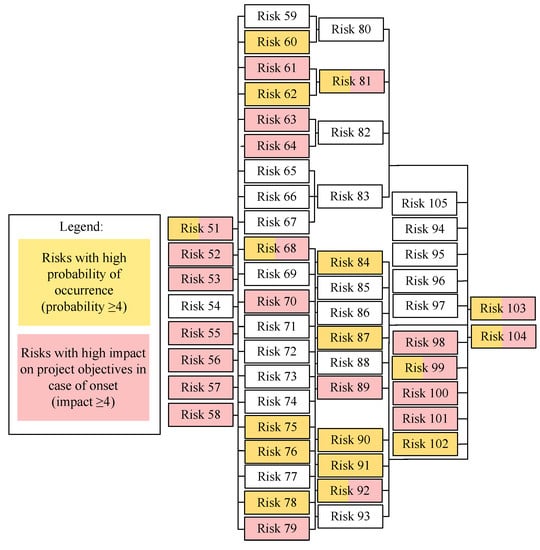

The cause-and-effect relationship model of project risks of IT projects, obtained during the analysis by the SWIFT method, is shown in Figure 3. The model clearly demonstrates that the initiating risks, whose materialization leads to the onset of subsequent risks, are risk events associated with the project manager and the project team. An analysis of these risks reveals that the main reason for their occurrence is the low professional training of the project team members. Therefore, for the effective and efficient management of project risks, systematic accreditation of project participants is required. Violations of this requirement adversely affect the project objectives and reduce the likelihood of their successful achievement.

Figure 3.

Model of cause-and-effect relationships of project risks of IT projects.

Furthermore, the analysis of the cause-and-effect relationship model of project risks in IT projects made it possible to establish that the onset of these risks leads to a change in the content, duration, cost and/or quality of the project. In particular, «project duration risk» and «project cost risk» are the most dangerous compared to other project risk events since the occurrence of any project risk affects the duration and cost of an IT project. It is important to emphasize that in the case of a negative scenario, when the duration and/or cost of an IT project does not meet the customer’s expectations, his refusal to accept and pay for the work performed (service rendered) may follow, initiating the onset of compliance risks.

4.3. Criteria for Evaluating the Maturity of IT Project Management

Based on the results of the 105 universal risks analysis using 5Why, SWIFT and Harrington coefficients, it was found that the main sources of risks are the project manager (43%) and the project team (36%). The remaining share (21%) is distributed among the customer, end user, subcontractor and competitor. It follows that in order to successfully achieve the project goals, it is necessary that the project manager and team members acting on the contractor (executor, supplier) side possess the necessary professional competencies. For example, the IT project manager is obliged to organize the process of concluding contracts and additional agreements with them, monitor the implementation of contracts, audit information system configurations, etc. In this regard, it is logical to assume that a systematic audit of the professional knowledge and skills of the project manager and project team members can be a preventive measure that eliminates this problem. Crawford’s studies support this assumption; he found that the formation and development of professional competencies recorded in the PMBOK Guide® require the systematic accreditation of project participants (Crawford 2006).

The contractor was also found to be the main source of risk. The only exception is the risk that competitors will influence the progress of work (the provision of services). This means that the contractor is obliged to assess risks in advance and develop the necessary measures to eliminate them, since it is the contractor who is responsible for the possible materialization of these risks.

In this regard, it can be concluded that the implementation of preventive measures aimed at the elimination of 105 risks can be a criterion providing the possibility to assess the maturity of a contractor (performer, supplier) planning to develop a program within the IT project framework.

It should be noted that the relevance of this problem is also confirmed by the results of studies by Hochstetter J., Vairetti C., Cares C., Ojeda M.G. and Maldonado S. In their works, they examine the characteristics that determine the reliability of contractors involved in fulfilling IT orders for government needs and come to the conclusion that reliable contractors have a high level of maturity in terms of risk management (Hochstetter et al. 2021). Scientists argue that the higher the level of maturity of risk management, the more reliable the contractor, since, as a rule, there are no unforeseen circumstances in the process of fulfilling an IT order.

5. Discussion

Addison T. and Vallabh S. in their work, discuss the occurrence of 14 risks that can materialize in the process of implementing an IT project (Addison and Vallabh 2002). The list of these risks is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

List of current IT projects’ risks according to Addison T. and Vallabh S. studies results.

Based on the risk analysis presented in Table 8, the following can be concluded:

- Addison T. and Vallabh S. risk list identifies the most dangerous risks for IT projects, the materialization of which can have a significant impact on the process of achieving project goals. However, the Nikolaenko V.S. risk list is of greater practical interest, as it captures not only dangerous risks for IT projects but also evaluates them, groups them, and establishes a causal relationship between them.

- There are no commercial or compliance risks in the risk lists of Addison T. and Vallabh S. According to the authors of this article, this is a significant omission, since the material damage of one compliance risk occurrence is on average $12,000.

- The list developed by Addison T. and Vallabh S. contains 14 risks, which, according to the authors of this article, is insufficient. In particular, the authors of the article believe that leveling the risks presented in Table 8 cannot guarantee the successful achievement of project objectives since the list does not contain such dangerous risks as “the risk of changing the norms of the current legislation”, “the risk of violating the norms of the current legislation” and others, the materialization of which can completely shut down the work in the IT project.

Stevens K. J. and Fowell S. in their writings, note that about 11 risks can materialize in IT projects (Stevens and Fowell 2003). The list of these risks is presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

List of current IT projects’ risks according to Stevens K. J. и Fowell S. studies’ results.

Based on the analysis of the risk list presented in Table 9, it can be concluded that Stevens K. J. and Fowell S. do not pay due attention to the group of compliance risks.

Sumner M. identifies 16 universal risks that can materialize during the implementation of an IT project (Sumner 2000). The list of these risks is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

List of current IT project risks according to Sumner M. research results.

Analysis of the Sumner M. risk list shows that among the presented probable events, as well as in other cases, there is no group of compliance risks.

Based on the considered risk lists, it can be concluded that the authors of this article, unlike their predecessors, conducted a study for 45 compliance risks relevant to IT projects, assessed their probabilities and impacts, identified the sources of these risks, and also established causal relationships between them.

6. Conclusions

The results of the analysis of 105 risks relevant to IT projects made it possible to formulate a criterion for the management maturity of a contractor (performer, supplier) planning to develop a computer program within the framework of an IT project. Using this criterion allows contracting with a more mature contractor who can guarantee the successful achievement of project objectives. It also means that customers are not recommended to conclude contracts with a contractor (executor, supplier) for the creation of computer programs until the necessary preventive measures are taken to eliminate risks.

It should be noted that the list of 105 risks is universal, i.e., these risks can materialize in any IT project regardless of the scale, complexity, duration, type and methods of management. Special risks are not included in this list because they are unique and occur in private IT projects. In this regard, the presence of a mechanism for identifying, evaluating and impacting special risks on the side of the contractor (executor, supplier) may be an additional criterion to assess its managerial maturity.

In 18 subsequent works, the authors, taking into account the results obtained in this study, are posed to develop and present the concept of the contractor (performer, supplier) maturity model, which will allow for the identification of the best counterparties that guarantee the successful completion of IT projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N. and A.S.; methodology, V.N.; validation, V.N.; formal analysis, V.N. and A.S.; investigation, V.N.; resources, V.N. and A.S.; data curation, V.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.N. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, V.N. and A.S.; visualization, V.N.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education; project FEWM-2023-0013.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Addison, Tom, and Seema Vallabh. 2002. Controlling Software Project Risks—An Empirical Study of Methods used by Experienced Project Managers. Paper presented at 2002 Annual Research Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists on Enablement through Technology, Gqeberha, South Africa, September 16–18; pp. 128–40. [Google Scholar]

- Aven, Terje. 2012. The risk concept—Historical and recent development trends. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 99: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backlund, Fredrick, Diana Chronéer, and Erik Sundqvist. 2014. Project Management Maturity Models—A Critical Review. A case study within Swedish engineering and construction organizations. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 119: 837–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basel Committee. 2005. Compliance and the Compliance Function in Banks. Basel: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Martina, Thomas Wolf, and Tirazheh Zare Garizy. 2015. Systemic risk in IT portfolios—An integrated quantification approach. Paper presented at International Conference on Information Systems: Exploring the Information Frontier, Fort Worth, TX, USA, December 13–16; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brandas, Claudiu, Otniel Didraga, and Nicolae Aurelian Bibu. 2012. Study on risk approaches in software development project. Informatica Economica 16: 148–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bushuyev, Sergey D., and Reinhard Friedrich Wagner. 2014. IPMA Delta® and IPMA Organisational Competence Baseline (OCB): New approaches in the field of project management maturity. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 7: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, Alan J., James R. Ward, and P. John Clarkson. 2012. Beyond FMEA: The structured what-if technique (SWIFT). Healthcare Risk Manage 31: 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Kent. 2006. Project Management Maturity Model. New York: Auerbach Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cule, Pual, Roy Schmidt, Kalle Lyytinen, and Mark Keil. 2000. Strategies for Нeading off Project Failure. Information Systems Management 17: 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bakker, Karel, Albert Boonstra, and Hans Wortmann. 2014. The Communicative Effect of Risk Identification on Project Success. Project Organisation and Management 6: 138–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERP. 2017. Enterprise Risk Management. Integrating with Strategy and Performance. New York: Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Ewusi-Mensah, Kweku, and Zbigniew H. Przasnyski. 1991. On Information Systems Project Abandonment: An Exploratory Study of Organizational Practice. MIS Quarterly 15: 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gładysz, Barbara, and Dorota Kuchta. 2022. Sustainable Metrics in Project Financial Risk Management. Sustainability 12: 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemstra, Fred J., and Rob J. Kusters. 1996. Dealing with Risk: A Practical Approach. Journal of Information Technology 11: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstetter, Jorge, Carla Vairetti, Carlos Cares, Mauricio García Ojeda, and Sebastián Maldonado. 2021. A Transparency Maturity Model for Government Software Tenders. IEEE Access 9: 45668–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutabarat, Novalina, Teguh Raharjo, Bob Hardian, Agus Suhanto, and Andi Wahbi. 2021. PMMM Kenzner Questionnaire Validation for Project Management Maturity Level Assessment: One of the Largest Indonesia’s State-Owned Banks. Paper presented at 2021 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS), Depok, Indonesia, December 14; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). 2018. ISO 31000:2018 Risk Management—Guidelines. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, Mark, Kambiz Saffarizadeh, and Wael Jabr. 2018. Update Assimilation in App Markets: Is There Such a Thing as Too Many Updates? Paper presented at Thirty Ninth International Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, December 13–16; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, One-Ki Daniel, and Deepa Varghese Baby. 2013. Managing dynamic risks in global IT projects: Agile risk management using the principles of service-oriented architecture. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making 12: 1121–50. [Google Scholar]

- Luckmann, John Arthur. 2015. Positive risk management: Hidden wealth in surface mining. The Journal of The Southem Africa Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 115: 1027–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Pablo, Isidro A. Pérez, María Luisa Sánchez, María de los Ángeles García, and Nuria Pardo. 2021. Wind Speed Analysis of Hurricane Sandy. 2021. Wind Speed Analysis of Hurricane Sandy. Atmosphere 12: 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merna, Tony, and Faisal F. Al-Thani. 2008. Corporate Risk Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Anant, Sidhartha Das, and James Murray. 2014. Managing Risk in Government Information Technology Projects: Does Process Maturity Matter? Production and Operations Management 24: 365–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaenko, Valentin S. 2016. Implementation of Risk Management in IT projects. Public Administration. E-Journal 54: 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaenko, Valentin S. 2018a. Negative and Positive Risks in IT projects. Moscow University Bulletin. Series 21. Public Administration 3: 91–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaenko, Valentin S. 2018b. Risk, risk management and uncertainty: Clarifying concepts. Public Administration. E-Journal 81: 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaenko, Valentin S. 2022. With the hope of taking a risk. A new approach to project management is proposed. Search 30–31: 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, D. 2018. The Way Forward: A Strategy for Harmonizing Agile and CMMI. CrossTalk. The Journal of Defense Software Engineering 29: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Odeh, Ammar, Ammar El-Hassan, Ismail Keshta, and Tareq AlHajahjeh. 2021. A Model for Understanding Project Requirements based on CMMI Specifications. Paper presented at 7th International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Istanbul, Turkey, October 27–28; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Paladino, Bob, Larry Cuy, and Mark L. Frigo. 2009. Missed opportunities in performance and enterprise risk management. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 20: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Apaza, Fernando, Andre Ramírez-Valenzuela, and Juan D. Perez-Apaza. 2021. The Toyota Kata methodology for managing the maturity level pf Last Planner® System. Paper presented at 29th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC29), Lima, Perú, July 12–18; pp. 514–23. [Google Scholar]

- Petroșanu, Dana-Mihaela, Alexandru Pîrjan, George Căruţaşu, Alexandru Tăbușcă, Daniela-Lenuța Zirra, and Alexandra Perju-Mitran. 2022. E-Commerce Sales Revenues Forecasting by Means of Dynamically Designing, Developing and Validating a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) Network for Deep Learning. Electronics 11: 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Dien, Douglas Vogel, and Jay Nunamaker. 1998. The Search for Perfect Project Management. Computerworld 22: 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, Robert. 1996. Risk Management and Agency Theory in IS Projects: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Information Technology 11: 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- PMBOK Guide®. 2017. Project Management Body of Knowledge, Guide, 6th ed.Newtown Square: Project Management Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Philip L., and Jonathan H. Klein. 1996. Risk Management for Information Systems Development. Journal of Information Technology 11: 309–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropponen, Janne, and Kalle Lyytinen. 2000. Components of Software Development Risk: How to Address Them? IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 26: 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, Rekhraj, Bhuneshwar Choudhuri, and Shravan Yadav. 2022. Usages of six sigma in library services. Paper presented at Conference: Library as a Medium of Communication; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364011786_Usages_of_six_sigma_in_library_services (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Shirinkina, Elena, Alsu Kuramshina, Nadezhda Antonova, and Oleg Kravets. 2022. Multi-aspect model for lean manufacturing implementation. Paper presented at II International Scientific Conference on Advances in Science, Engineering and Digital Education: (Asedu-II 2021), Krasnoyarsk, Russia, October 28. [Google Scholar]

- Sidorov, Anatoly, and Pavel Senchenko. 2020. Regional Digital Economy: Assessment of Development Levels. Mathematics 8: 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Kenneth, and Sue Fowell. 2003. Perspective on E-Business Software Project Risk. Paper presented at 7th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Adelaide, Australia, July 10–13; pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, Mary. 2000. Risk factors in enterprise-wide/ERP projects. Journal of Information Technology 15: 317–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Standish Group. 2014. The CHAOS Manifesto. West Yarmouth: The Standish Group. [Google Scholar]

- Vujovic, Vuk, Nebojša Denić, Vesna Stevanović, Mališa Stevanović, Jelena Stojanović, Yan Cao, Yasir Alhammadi, Kittisak Jermsittiparsert, Hiep Van Le, Karzan Wakil, and et al. 2020. Project planning and risk management as a success factor for IT project in agricultural schools in Serbia. Technology in Society 63: 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegers, Karl, and Joy Beatty. 2013. Software Requirements. Redmond: Microsoft Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti, Dewayani Nur, Tatan Sukwika, and Soehatman Ramli. 2022. Analisis Insiden Fatality Akibat Covid-19 Menggunakan Metode 5 Why, SCAT, BowTie, dan ISM. Jurnal Migasian 6: 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).