Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to present the two existing virtual account models functioning in the European Union, examine their legal validity and identify the legal challenges related to the functioning of these models. The first model, Mass Payment Accounts, which is related to virtual accounts rather than to virtual IBANs, is the model where the licensed financial institution only provides a business payment (settlement) account, with technical subaccounts, to one of their business clients. The functionality of the subaccounts is limited to reflect and distinguish the incoming payments. The second and more complex model is the vIBAN solution, where the licensed payment institution provides, to another licensed financial institution, indirect access to local payment schemes (hereinafter referred to as “vIBAN”). To confirm the legal validity and identify the potential risks of vIBAN services, EU law was analysed with some insights from Polish law. The reason for introducing vIBAN services is the difficulty for certain payment service providers to participate in so-called designated payment systems. Designated payment systems are usually the most widespread local payment systems. The reason for the different treatment of these designated systems is banking systemic risk, understood as a situation where a default by a system participant may result in a default by other participants. Consequently, even if a given payment service provider can obtain its own IBAN number, there is often no possibility for it to participate in designated payment schemes. Bearing in mind the different rules in the case of designated payment systems, the legality of vIBAN services in the EU law is justified by the principle of free movement of services, the principle of equal access to payment schemes and the obligation of the credit institutions to provide banking and non-banking participants with credit institution payment account services on an objective, non-discriminatory and proportionate basis. However, there are various challenges related to the functioning of vIBAN services, such as the overlapping of certain AML/CFT obligations, enforcement of administrative and court seizures, AML-related blocking of vIBANs and consistency of money transfer sender data with the Fund Transfer Regulation. The most pressing challenges requiring prompt regulation on the European level are related to the applicable deposit protection scheme, as well as to specific Member States’ administrative restrictions, which can cause difficulties in offering vIBAN services to business entities.

1. Introduction

IBAN is the acronym for International Bank Account Number. It is an internationally recognised standard used for processing payment transactions, both across borders and domestic. It identifies the payment account of the customer, as well as that of the financial institution which provides the service. IBAN originated as a solution to integrate payments within the European Union and European Economic Area. It is now officially supported by 80 countries (including all EU/EEA countries and Switzerland). In 26 other countries, this standard was partially introduced (SWIFT 2022). Cross-border money transfer using the IBAN standard is recognised by other major countries where the standard is not implemented (e.g., Canada and the USA). The registration authority for the IBAN ISO 13616:2020 standard is SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications network, created by worldwide financial system participants for financial messages and transactions (IBAN n.d.).

One IBAN function is to create the possibility for a financial institution to participate in international and national payment systems and offer its customers international and national money transfers. While performing SWIFT payments using IBAN does not require specific country establishment of the payment service provider, access to national payment systems throughout the EU is, as a rule, limited to entities having their physical establishment in an EU Member State. Even if a given payment service provider can obtain a local IBAN number, in order to participate in the local payment systems, the relevant national authorities require, from the payment service provider, an establishment in a given country, i.e., either a headquarters or a branch.

Having a physical establishment in a particular country causes increased costs and obligations for a financial institution. Such an establishment may not be economically reasonable taking into account the number of potential clients or the pure internet-based character of the payment services in scope, which do not require a physical presence. Therefore, in market practice, services in the form of offering “virtual” accounts, also called “virtual IBANS” emerged.

Currently, vIBAN services are not explicitly regulated. They are considered to be a service which falls under the larger category of Banking-as-a-Service or White Label Banking (Grabowski 2021). There is also limited research related to this topic. The aim of this research paper is to outline the two groups of existing vIBAN models: virtual accounts used as mass payment accounts (Model 1) and the vIBAN model (Model 2), where the account holder provides their own payment services to the end-users, taking into account their own financial authorisation. These models were analysed with respect to the related EU regulations, including an insight into Polish law as an EU transposition law. Legal grounds for providing vIBAN services, as well as the legal challenges concerning the provision of these services in the EU, were identified. Findings include the assessment of the legal validity of the presented models, as well as de lege ferenda and future conclusions.

2. Literature Review

While the concept of Open Banking is quite well developed in the financial literature, Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS), often called White Label Banking is relatively new. Sometimes, the term “Open Banking as a Service” (Farrow 2020) is used for the purpose of identifying new services that break the banking monopoly by providing certain financial services. Examples may be CBI Globe—the Global Open Banking Ecosystem—originating in Italy (Passi 2018), or the solution provided by Commerzbank in the field of accounts, cards, payments, securities (Berentzen et al. 2021). There are concerns regarding the extensive use of customer data and its influence on the development of new banking services (Wossidlo and Rochau n.d.). Nevertheless, there are positive aspects to having such a wide access to customer data by the financial system participants. The vast amount of financial data possessed by traditional banks and Fintechs can be used, for example, for fraud identification, employing an appropriate method of detecting clusters (Li et al. 2021).

Empirical studies proved that the strongest alternative to traditional banking services is payments. Therefore, European banks should mainly focus on payment alternatives for Fintech investments to attract customer attention and achieve effective collection of receivables. Additionally, Fintech investments in money transferring could help banks decrease their costs, which is expected to have a positive influence on their sales volume (Kou et al. 2021). It was noted that, with regard to existing “traditional banking”, Banking-as-a-Service will bring greater competition from challengers and possible further erosion of margins. Alternatively, some banks will proactively engage in partnerships and acquisitions to maintain their customer base and address competition (Broby 2021).

The provision of services based on the concept of banking as a platform is now possible, primarily due to the digital transformation of the sector (Naimi-Sadigh et al. 2021). It can be expected that technological changes will result in the emergence of new services. An example is the concept of the Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), which can technically be based on blockchain technology. The introduction of the CBDC, when implemented by major countries, could have a disruptive effect on financial markets. The economy-wide adoption of a CBDC may significantly lower consumer need for demand deposits (Jun and Yeo 2021). Such an adoption could also have a tremendous impact on payment schemes and would most probably lead to the development of new payment and settlement solutions which would replace the existing schemes.

Non-banking entities wishing to provide financial services also face certain constraints; one example is access to payment systems, in particular, the so-called designated payment systems (Górka 2016). Providing indirect access to designated payment systems is the core component of services referred to as virtual IBANs, analysed in this article.

3. Methodology and Limitations

To confirm the legal validity and to identify potential risks in the presented two models of virtual account services, primary and secondary EU law were analysed, taking into account such basic principles as the freedom to provide services and the freedom of establishment, as set forth in the Treaty of Functioning of the European Union. Secondary EU law is set forth in the Settlement Finality Directive, CRD4 directive, and the PSD2 directive which is based on the “high harmonisation” principle. Although the high harmonisation principle establishes a certain level of equality on the EU-wide level, the directive must still be transposed into national law. As far as the respective Acquis Communautaire is based on direct (regulations) and indirect (directives and other acts of soft law) legal acts, some insight into the transposed Member State’s law is required. Because the regulations concerning vIBAN services have their roots in EU Law, the teleological method of law interpretation was accommodated.

The scope of this article is limited to analysing the two most representative variants of virtual account services. This scope is not exhaustive; there may be different related models for providing safeguarding accounts for Payment Institutions and Electronic Money Institutions, which can be related to providing access to payment schemes.

4. Two Basic Models of vIBAN Solution

There are currently two basic models of virtual accounts in use, which are provided under the EU legal regime. The first group can be called “Mass Payment Accounts”, the second group, Virtual IBANs. Both groups will be presented in the next section.

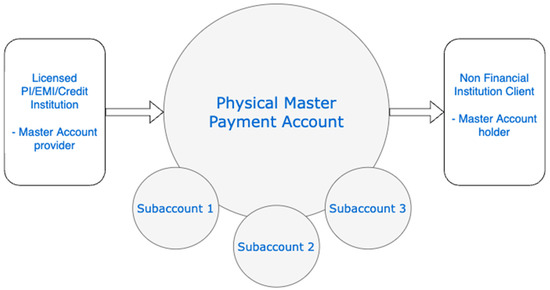

The first, simpler model of virtual accounts is the model of Mass Payment Accounts. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the service provider (licensed financial institution) and the service receiver (the entity that takes into account the services of mass payment subaccounts).

Figure 1.

Mass payment accounts.

The name “mass payment” best reflects the purpose of the created technical accounts (subaccounts) which, at the same time, can have allocated IBAN numbers. These are usually used for the needs of large payment receivers with many clients, such as telecommunications, internet or energy providers. They are also useful for smaller provider billing systems, both in the private and public sectors. The subaccounts are allocated to individual clients. The main purpose of these accounts is payment identification—the correct recording of inflows and their assigning to a specific client. They enable the clients (the end-users) to only pay in funds using their specific allocated IBAN. Usually, the client can only check the balance of a subaccount in the application of the provider and has no ability to make requests to the subaccount. If the client aims to withdraw the deposited funds, they submit a request to the provider, who is able to execute it. The balance in the subaccount can be negative (e.g., in the case of an invoice payment being overdue).

Subaccounts are linked to the Master Account (Physical Master Payment Account) for the purpose of reconciliation. All incoming and outgoing funds are reflected in the Master Account and typically, automatically, in the subaccounts.

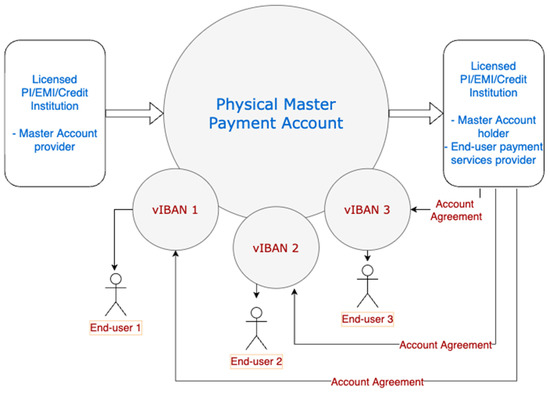

The second model of virtual accounts is the model of “true” virtual IBANs being separate payment accounts. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the service provider (licensed financial institution) and the service receiver (licensed financial institution), as well as between the service receiver and the end-customer (the additional layer marked in red).

Figure 2.

vIBANs.

The basic setup of vIBANs is similar to the setup of subaccounts in the Mass Payment model. The Partner opens a settlement account (with an optional safeguarding function) with the service provider (licensed financial institution having access to local payment schemes). The technical accounts (subaccounts) are then created and the respective IBANs allocated to these accounts. The subaccounts may be technically maintained either in the Provider’s or in the Master Account Holder’s system. The money flows are reflected both in the Master Account (“real” funds) and the subaccounts (only a “virtual” counterpart of the funds in the Master Account). The difference is the extended functionality of the sub-accounts and a result of this is an additional contractual layer (pictured red in Figure 2 and explained in the next part of this article). vIBANs enable the end user to not only deposit funds, but also to deduct them using various payment instruments. The functionality of vIBANs is similar to that of traditional “real” payment accounts, i.e., handling settlements including outgoing money transfers, connecting debit cards and keeping the account balance. They are also presented within open banking solutions, enabling “passive” payment initiation services and account information services.

The vIBAN model can also be used to provide an electronic money wallet to the end-users. The wallets can be offered as prepaid, or qualify as limited network solutions. Such wallets may have further restrictions, such as spending limitations or certain types of payments; for example, they can be useful when connected with a card or used for special purposes, such as restaurant vouchers or sport cards for employees.

vIBANs can be further “nested”, e.g., vIBAN 1 can have three further subaccounts (subvIBAN 1.1, subvIBAN 1.2, subvIBAN 1.3) allocated to different purposes. The performed transactions are first reflected in the subvIBAN, then in the vIBAN and, finally, in the Master Payment Account.

5. Legal Construction of the Virtual Account Models

The first model of virtual accounts—Mass Payment accounts—is based on a settlement account agreement. The provider of such an account requires a license which enables it to offer payment accounts. According to the second payment services directive (PSD2), a payment account is defined as an account held in the name of one or more payment service users which is used for the execution of payment transactions. Providing payment accounts is a payment service and, if provided in EU/EEA territory, requires appropriate authorisation. This can be an authorisation to act as a payment institution (PI), electronic money institution (EMI) or credit institution or a branch of a foreign bank (UK, Switzerland, USA). PSD2 empowers the Member States to relax the authorisation requirements to a limited extent. As a result, there are various other “local” payment service providers entitled to provide payment accounts, such as small payment institutions in Poland (małe instytucje płatnicze).

The counterparty to the settlement account agreement is the account holder, which is a business entity, whether a corporation or a sole trader. The account holder does not require any authorisation to hold the account. However, they require a title to hold the end-users’ money which is credited to the subaccounts and the Master Payment Account. As a rule, the basis for holding the end-users’ money is an underlying commercial agreement (e.g., energy supply, providing access to internet services). There may also be cases where the Mass Payment Account Holder is a licensed financial institution itself and, acting under this license, it utilises the subaccounts to provide its own payment or other financial services to its end-users. Such a setup should be carefully scrutinised for additional legal requirements and similarities to Model 2.

The relationship between the Master Account Provider and Master Account Holder is covered by the legal construct of the payment account agreement. This agreement is regulated by the particular Member State’s national law transposing the PSD2 (e.g., BGB and Zahlungsdiensteaufsichtgesetz in Germany, Ustawa o usługach płatniczych in Poland), but also by other relevant EU and national laws.

While the Master Account qualifies as a payment account, the generated subaccounts do not qualify as payment accounts or banking accounts. The end user is only able to fund such an account but not to execute any payment transactions. Consequently, the Master Account Holder does not have the obligation to enter into a payment service agreement with the end-user. Such a subaccount is not required to offer the possibility of initiating payments or providing aggregated information in the account and payment transactions, as is required for payment initiation services and account information services (so called “passive” PSD2 functionalities). The request directed by the end user to the Master Account Holder to withdraw money is not treated as a payment order within the meaning of PSD2, resulting in an extended execution time for such requests (PSD2, as a rule, requires the payment transactions to be executed T+1, i.e., by the end of the next business day).

The first “layer” in Model 2, vIBANs, is similar to that in Model 1. The licensed Master Account Provider offers a payment account to the account holder. However, in Model 2, the created subaccounts, the vIBANs, constitute payment accounts themselves. It is possible for the end user to execute payment transactions such as money transfers or card payments. This has two major implications: (1) the Master Payment Account Holder requires authorisation to provide payment services to its end-users; and (2) this Holder has an obligation to enter into payment services agreements with its end users and perform any related obligations.

To provide payment services to its end users in the UE/EOG, the Master Payment Account Holder must be authorised as a PI/EMI, Credit Institution or branch of a foreign bank (however, in this last case, it may be difficult to obtain access to the local payment schemes). This authorisation must be valid in the Member State where the Master Payment Account Holder provides its services. Usually this occurs by way of passporting due to the EU freedom to provide cross-border services. The Master Payment Account Holder enters into a contractual relationship with its end users (red layer in Figure 2). This relationship is also based on the construct of a payment service agreement, mostly regulated by the local laws introduced as a transposition of PSD2. The functionalities, and legal and contractual regulations, of such payment accounts provided to end users are similar to those for traditional “real” payment accounts. The Master Account Holder is obliged to provide open banking access functionality for such accounts, including “passive” capability for payment initiation services and account information services, which an end user may wish to consider.

In Model 2, the provided Master Payment Account may qualify as a safeguarding account according to PSD2. PIs and EMIs have the obligation to safeguard the incoming client funds, which are not disposed of until the next business day. One legally permitted safeguarding method is to deposit such client funds in a safeguarding account. In this case, the Master Payment Account has the function of both the settlement account and the safeguarding account. The benefit of the safeguarding account is that the deposited client funds are insulated in accordance with national law in the interest of the payment service users against the claims of other creditors of the PI/EMI, in particular in the event of insolvency.

As a rule, the services provided by the Master Payment Account Provider to the Master Payment Account Holder can qualify as a type of corresponding banking service. Such services are generally exempt from the outsourcing regime according to the EBA Guidelines on Outsourcing Arrangements. The EBA Guidelines indicate outsourcing as an arrangement of any form between an institution, a payment institution or an electronic money institution and a service provider, by which that service provider performs a process, a service or an activity that would otherwise be undertaken by the institution, the payment institution or the electronic money institution itself. The vIBAN provider offers, under its own license, payment services to the end-users. To be able to provide these services, the vIBAN provider assumes the services of the Master Payment Account Provider—to provide accounting, reconciliation, access to payment rails and related services.

6. Legal Grounds for Providing vIBAN Services in the EU and Poland

There are no dedicated regulations at the EU level for providing vIBAN services. From the perspective of public law, both the Master Account Provider and the Master Account Holder can have the appropriate authorisation to provide services under the relevant EU Member State law. In the case of the Master Account Provider, it is the authorisation as a Credit Institution/PI/EMI/other entity to provide payment services in the territory of the Member State, where these entities have an establishment (the freedom of establishment). For the Master Account Holder, and, simultaneously, for the vIBAN provider, the legal grounds for providing payment services to the end user in the territory of a given Member State is passporting, on the basis of freedom of providing services. This does not exclude the right of the Master Account Holder to provide its services (freedom of establishment) or to act as a branch located in the EU/EEA of a foreign bank.

The EU approach towards granting a payment service provider access for payment rails for other service providers is reflected in PSD2 and its Article 35 concerning access to the payment schemes. According to this provision, payment systems shall not impose on payment service providers, on payment services users or on other payment systems any of the following requirements: (i) restrictive rules on effective participation in other payment systems; (ii) rules which discriminate between authorised payment service providers or between registered payment service providers in relation to the rights, obligations and entitlements of participants or (iii) restriction on the basis of institutional status. This provision constitutes the right of payment service providers to access the payment schemes or, if the payment scheme rules for a given participant are not consistent with Art. 35 PSD2, the right to equal treatment or other resulting rights. These rights can be executed in civil proceedings in respective civil courts. At the same time the providers of the payment schemes are entitled (and obliged) to set appropriate requirements to ensure the integrity and stability of their payment systems; they must be able to verify that the internal arrangements of the applying PSP are sufficiently robust against all types of risk. The differences in price conditions for different types of PSPs should be allowed only where these are motivated by differences in costs incurred (see the motives underlying PSD2). The main aim of the provision is to provide equality and a level playing field among the different categories of PSP (i.e., credit institutions and payment institutions/electronic money institutions). However, it cannot be interpreted as an obligation for the payment schemes to grant access to all, even authorised PSPs, without taking into account the risk related to such access and the individual situation of a given PSP applicant.

The rules of participation in the payment systems are controlled by the banking supervision authorities, firstly, for establishing the system, and secondly, on an ongoing basis. They can also be examined by the respective competition authorities with regard to consistency with competition law.

As a consequence of easing the access rules to the payment systems, a wide range of non-banking entities obtained access to various existing payment schemes. Directive 207/64/EC (PSD1) introduced the possibility of providing payment services to non-banking payment service providers—Payment Institutions and Electronic Money Institutions. PSD1 (Art. 28) introduced, for payment service providers, similar rules for access to the payment schemes, as did PSD2. PSD1 came into force on 25 December 2007. A consequence of “breaking” the banks’ monopoly on providing payment services was the increased possibilities for these new entities to access payment schemes. Accordingly, PSD2 introduced further types of payment service providers, such as payment initiation service providers (PISP) and account information services providers (AISP). Neither type of providers participates in the payment schemes. Rather, they have the legal ability to ensure, for their users, access to payment accounts provided to them by account servicing payment service providers (ASPSP), and to initiate payments or receive information in the accounts.

The obligation to enable access to payment systems with “non-restrictive” rules does not apply to payment systems designated under Directive 98/26/EC (Settlement Finality Directive, SFD). PSD2 requires only that Member States ensure that where a participant in a designated system allows an authorised or registered payment service provider that is not a participant in the system to pass transfer orders through the system, that participant shall, when requested, give the same opportunity in an objective, proportionate and non-discriminatory manner to other authorised or registered payment service providers. The reason for the special regulation of designated payment systems is their importance for the banking sector of a given Member State, and any related systemic risk which should be prevented. Systemic risk is defined by the Polish Settlement Finality Act as the risk of a situation where a default by a system participant may result in a default by (an)other participant(s).

In Poland, the designated retail payment system for PLN is Elixir, which, at the same time, is the most widespread retail national payment system. Elixir enables money transfers, direct debits and cheque reconciliation. The second designated retail system is Euro–Elixir. Both systems are provided by the Polish National Clearing House (KIR). A prerequisite to participate in the Elixir system is to have an open current account at the National Bank of Poland (NBP) in the SORBNET2 system. This, however, is only possible, according to the Polish National Bank Act, for (national) banks and for other legal entities, following approval by the President of the Polish National Bank. The possibility to participate in the National Bank’s settlement system also determines the possibility to perform settlements in the National Bank’s currency and to participate in Polish designated systems (Masłowski 2020). The NBP offers a settlement service for payment systems operated by KIR SA. A bank’s net liabilities and receivables resulting from the exchange of payment orders in PLN or in EUR, made, respectively, in the Elixir and Euro Elixir systems through KIR SA, are settled, respectively, in the SORBNET2 system and TARGET2-NBP, in settlement sessions performed during fixed hours with the NBP. The SORBNET2 system also maintains a KIR SA escrow account, for which banks that are participants in the Express Elixir system, i.e., the instant payment system afforded by KIR SA, maintain the liquidity necessary to conduct settlements in the Express Elixir system. The NBP is also a direct participant in the KIR SA system (Narodowy Bank Polski 2019).

At the same time, according to Article 35 (2) PSD2, where a participant in a designated system allows an authorised or registered payment service provider that is not a participant in the system to pass transfer orders through the system, that participant shall, when requested, give the same opportunity in an objective, proportionate and non-discriminatory manner to other authorised or registered payment service providers.

Article 35 (2) (a) PSD2 cannot be interpreted in such a way that a payment service provider who obtained access to the designated payment schemes is obliged to grant further (indirect) access for other payment service providers to participate in the designated system (Grabowski 2020). However, the PSPs participating in the designated payment systems are, on the basis of Art. 35 (2), entitled to grant further access to the schemes to other authorised PSPs. If they decide to grant such access, they are obliged to assure that the access rules for such indirect participants are equal and non-discriminatory for each of the participants. At the same time, the participant cannot set the rules for indirect access, as this would contradict or circumvent the rules set by the payment scheme provider for the scheme.

Article 35 PSD2 is interpreted in connection with Article 36, which obligates (after the transposition to the Member State’s national law) the credit institutions to provide the non-banking PSPs (payment institutions, electronic money institutions and various other national PSPs introduced according to PSD2 national transposition) access to credit institution payment account services on an objective, non-discriminatory and proportionate basis. Such access is sufficiently extensive as to allow payment institutions to provide payment services in an unhindered and efficient manner. If a credit institution rejects such access, it must provide the competent authority with duly motivated reasons. The motives underlying PSD2 emphasise that while such access can be basic, it should always be sufficiently extensive for the payment institution to be able to provide its services in an unobstructed and efficient way.

Both rules—principles for accessing payment schemes and principles for accessing payment accounts held with the credit institutions—are for the benefit of not only authorised PSPs but also, indirectly, for payment service users. The aim is to provide the end users with complex, wide and cost-effective payment services.

Although the aim of the PSD2 rules for access to payment schemes was to provide a level playing field for PIs and EMIs, they also apply to other types of PSP, such as credit institutions or branches of foreign banks. A PSP applying for access to payment schemes can apply for access, either utilising its right to establishment, or the freedom to provide services and passporting rights (European Commission 2011).

7. Legal Challenges concerning the Services of vIBANs (Model 2)

In both Model 1 and in Model 2, the Master Payment Account Provider offers a “conventional” business account to the Master Payment Account Holder. This account is bound by all rules related to providing payment accounts. In particular, the Master Payment Account provider must perform all Know-Your-Customer (KYC) verification duties. The provider is also obliged to monitor the transactions executed in the account and undertake sanction screening according to the local law transposing the Directive EU 2018/843 (AMLD5).

While Model 1 relies on the services of the Master Payment Account Provider and is quite well regulated, Model 2 poses several legal challenges.

In Model 2, the Master Payment Account Holder provides its own payment services, under its own license, to the end-users. Its obligation is to perform all duties in terms of customer onboarding and KYC, as well as the monitoring and screening of end-user payment accounts. At the same time, as all the transactions in an end-user subaccount are reflected in the Master Payment Account, they are subject to monitoring and screening by the Master Payment Account Provider. In practice, the transactions are monitored and screened twice: by the Master Payment Account Provider and by the Master Payment Account Holder (and vIBAN provider). Suspicious transactions can be blocked by the Master Account Provider without informing the Master Account Holder, who is responsible for the end-user vIBAN relationship. From the end-user perspective, it is very important that both these players cooperate closely.

vIBANs, as payment accounts, are subject to compulsory enforcement of administrative and court seizures. However, in practice, the enforcement authorities often direct their requests to seize the vIBAN of a particular end user to the Master Account Provider. The Master Account Provider only offers the Master Account to the Master Account Holder. Therefore, they can take adequate measures with regard to this account only because they do not have a contractual relationship with the end-user. To be able to validify the execution, such requests should be directed to the vIBAN provider. However, this can be challenging because the vIBANs may not be reported within the local evidence and information-sharing systems which are used by bailiffs and other state authorities (i.e., OGNIVO in Poland). The Master Account Provider reports only the Master Account as provided by itself.

The same rule applies to requests from the anti-money-laundering authorities (Główny Inspektor Informacji Finansowej in Poland). However, one best practice suggests that, if the Master Payment Account Holder receives such a request to block a certain vIBAN, they can block a respective amount in the Master Account and redirect the request to the Master Payment Account Provider. At the same time, the Master Account Holder informs the AML authorities about passing the request to the provider of the respective vIBAN.

All payment transactions performed by payment service providers established within the EU/EEA are bound by obligations resulting from Regulation 2015/847 (Funds Transfer Regulation). The payment service provider of the payer shall ensure that transfers of funds are accompanied by the following information on the payer: (i) the name of the payer; (ii) the payer’s payment account number and (iii) the payer’s address, official personal document number, customer identification number or date and place of birth. Accordingly, the payment service provider of the payer shall ensure that transfers of funds are accompanied by the following information on the payee: (i) the name of the payee and (ii) the payee’s payment account number. In practice, there is legal uncertainty regarding who should be indicated as the sender of the money transfer executed from a vIBAN. Practically, the money transfer is initiated from the Master Payment Account; it is, therefore, common practice (e.g., in the Polish market) that the providers indicate the Master Payment Account Holder as the sender of the money transfer. Details of the vIBAN holder are provided in the title field of the money transfer. However, from the legal point of view, the vIBAN is considered to be a payment account itself. Therefore, if an end user initiates a payment, it seems that they should be indicated, respectively, as the sender of the transfer. Another question arises regarding which entity is legally responsible for ensuring the compliance of the end-user money transfer information with the Fund Transfer Regulation. As this service is provided by the Master Account Holder, it seems that it should also be responsible for this obligation.

According to directive EU 2014/49 for deposit guarantee schemes, the Member States are obliged to introduce respective deposit protection schemes. As a rule, the deposits of a particular client within the same credit institution are guaranteed up to an amount of EUR100,000. However, there is uncertainty related to vIBANs. The Master Payment Account Provider is the licensed financial institution with access to payment rails. From the Master Account Provider’s perspective there is only one Master Payment Account Holder. The guaranteed level for the whole Master Payment Account deposits should, therefore, be EUR100,000. However, legally, each of the vIBANs constitutes a payment account itself. Technically, the funds are deposited at the ledger of the Master Payment Account Provider but, legally, the deposit-receiving credit institution is the Master Payment Account Provider. As a result, the end-user deposits should be protected by the deposit protection scheme of the Master Payment Account Holder—up to EUR100,000 for each end-user. As an example, if the Master Payment Account Holder is licensed in Poland and the Master Payment Account Provider is licensed in France, the French deposit protection scheme regulates the protection rules for the end-user deposits within the deposit-taking vIBAN provider. If the fund-receiving vIBAN provider is not a credit institution, but an IP or an EMI, end-user money is safeguarded according to the local EU Member’s laws, introduced as a transposition of PSD2 and EMD2.

There are also several challenges concerning the possibility of offering end users vIBANs to be used for business purposes. Many EU Member States have special legislation in place to prevent tax evasion and financial crime, such as the “split payment” in Poland (as well as in Italy and Romania). This concept relies on creating an additional VAT account which is ancillary to the standard business account and whose purpose is to be used for VAT reconciliation in case of high-value, and special categories of, business payments. The business settlement account should also be reported by the end user to the “white list” of VAT payers. Additionally, there is an obligation in Poland for business settlement account providers to report such business accounts to the STIR system. STIR is a tele-information system in the Polish Clearing House whose purpose is to process the data provided by financial institutions in order to analyse the risk of using the financial sector for fiscal fraud. However, the existing Polish legislation is not clear about whether vIBANs provided by the Master Account Holder to the end users can be reported to STIR and have a VAT-account created. First, it is not very clear who should report the accounts. On the one hand, the Master Payment Account is, itself, a business settlement account. It is provided by the Master Account Provider and, as such, should, potentially, be reported to STIR, be white-listed and have a VAT account created. On the other hand, vIBANs are “full” payment accounts within the meaning of the PSD2 directive itself. Thus, legally it should also be possible to use such accounts for business purposes. However, the vIBANs are provided by the Master Account Holder, not by the Master Account Provider. It is not very clear whether they can be STIR-reported by the Master Account Provider, which has access to the reporting facilities. Furthermore, limiting the possibility of offering business accounts with access to local IBANs only to institutions having a branch in the country would lead to the violation of competition rules. As a result, the tax laws, which must be neutral (particularly in respect to VAT), would limit the freedom to provide the services (in this situation, the payment services according to PSD2 directive).

8. Findings and Conclusions

There are two virtual IBAN models functioning on the European market. The first is the Mass Payment Accounts model, the second can be called “real” virtual IBANs (vIBANs). Mass Payment Accounts take into account the payment services of a payment service provider authorised in an EU country. The Account Provider opens a business account for the Account Holder. The Account Holder creates the technical subaccounts (held with the Account Provider) which have their own IBAN numbering. The function of the individual subaccounts is to separate the funds coming from the end users of the Account Holder. The Account Holder does not provide the payment services to the end users but, rather, has a commercial relationship with them, such as providing telecommunication or energy supply services. This commercial relationship is the basis for the Account Holder holding the end-users’ money. While it provides the services to the end-users, the Account Holder in Model 1 does not own or utilise their own license. As the described Model 1 is a basic one, there may be some variation.

In Model 2, the Account Holder is authorised in a given EU country and provides payment services to its end-users, taking into account the authorisation. The virtual IBANs offered are “full” payment accounts within the meaning of PSD2. The vIBANs not only allow the end users to deposit funds, but also to consider other payment services, such as outgoing money transfers, card payments or various e-wallet solutions. The vIBANs allow “passive” PSD2-based payment initiation and account information services.

The reason for creating the vIBAN services was to address difficulties obtaining access to local designated payment schemes, like Elixir in Poland, for payment service providers acting in a given Member State, on the basis of the freedom to provide services. Various EU Member States limit the possibility of participating in so-called designated payment systems to financial institutions licensed in the given Member State or having a branch there. This constitutes a limitation on the EU principle of freedom to provide cross-border services. The legal grounds for providing such services are the Treaty of Functioning of the European Union, the PSD2 directive regarding PIs and EMIs and the CRD directive with regard to credit institutions. The PSD2 directive enhances access to payment schemes for “new” market entrants, such as PIs and EMIs, imposing non-discriminatory obligations on payment scheme operators. However, PSD2 makes an exception for the designated systems, which have an important role in a given Member State’s banking system and, therefore, there is the need to prevent systemic risk. These are usually the most widespread local payment systems in the given country, such as Elixir in Poland. Therefore, to be competitive, the PSPs acting in the given EU Member State seek access to such systems. With regard to Poland, it can be possible for PSPs authorised in other EU countries, and acting across borders, to obtain a Polish IBAN number. However, it would not be possible to open a current account with the National Bank of Poland, which is needed for reconciliation within the Elixir system.

PSD2 also imposes an obligation on PSPs participating in designated payment systems to provide further access to indirect participants on an equal basis. However, by providing further access, the PSPs cannot extend or change the particular designated payment system rules.

In addition, the credit institutions have an obligation to provide non-banking PSPs with access to payment account services on an objective, non-discriminatory and proportional basis. These rules aim to provide a level playing field for non-banking payment service providers, as well as to other types of PSP, such as credit institutions or branches of foreign banks which can act on either the basis of the freedom of establishment or the basis of freedom to provide services. The same rule applies for credit institutions and branches of foreign banks.

As a result, all legal provisions limiting the access to payment schemes for authorised payment service providers, including acting across borders, should be interpreted in a narrow manner. There are no general rules which would constitute constraints on providing vIBAN services to other PSPs by the PSPs participating in the designated payment systems.

vIBAN services face various challenges, such as “overlapping” of the AML obligations with regard to monitoring and screening of the payment transactions, which must be performed by both the Master Account Provider as the Master Account Holder. This could lead to operational problems, such as (if allowed) informing the customers about blocked transactions. The same applies to blocking transactions on the request of the AML authorities. If a request to block is directed at the Master Account Provider, best practice is to perform a preliminary blocking and refer the request to the Master Account Holder for assessment and execution.

Further lack of clarity involves the compulsory enforcement of administrative and court seizures. While, legally, these should be addressed to the Master Account Holder as the end-user payment account provider, in practice, the enforcement authorities are not aware of the specifics of vIBAN construction and direct their requests to the Master Account Provider. In Poland, such vIBANs are not reported in the local OGNIVO system used by bailiffs, thereby rendering them difficult to identify. The same rule applies to requests to block vIBANs from AML authorities and prosecutors. Best practice suggests the AML/CF-related blockings addressed to the Master Account Provider should be temporarily executed and referred to the Master Account Holder for review.

There is legal uncertainty as to which provider can be held liable for consistency with the Fund Transfer Regulation and which entity (the Account Holder or the end-user) should be indicated as the sender of the money transfer. As the vIBAN is a PSD2-based payment account, it seems that the end user should be indicated as the sender of the transfer.

An important aspect of providing payment accounts is the protection of deposits. Despite the Master Account being a payment account itself, vIBANs—subaccounts—are also offered as payment accounts. Therefore, the funds deposited in vIBANs are subject to the deposit protection scheme applicable to the Master Account Holder. For example, if the Master Account Provider is authorised in Germany and the Master Account Holder is authorised in Lithuania, the Lithuanian deposit protection scheme should apply to the protection of end-user deposits in the vIBANs, up to EUR100,000 for each account.

In some EU Member States there are special administrative obligations related to providing business accounts to sole traders and business entities. For example, in Poland, there is an obligation on the PSP to establish an ancillary VAT account for each business account and to report such business accounts to the local fiscal fraud prevention system—STIR. On the other hand, to be able to perform VAT-related, high-value and sensitive reconciliations, the end user is obliged to report such a business account to the white list of VAT payers. Such administrative obligations, however, do not prevent offering vIBAN services to end users for business purposes. Such a limitation would not be aligned with the principle of neutrality of tax rules or with the freedom to provide services within the EU.

De lege ferenda, there should be proper legislation in place regulating vIBAN services in the EU Member States, especially indirect access to the designated payment systems by non-banking financial service providers. The easiest approach would be to abolish entirely the special rules relating to participation in the designated systems. This would create the ability to participate in these systems for all authorised entities providing services either on the basis of the freedom of establishment or the freedom to provide the services. On the other hand, this would limit the flexibility of the Member States’ authorities to set the rules for the functioning of the designated payment systems. This could lead to increasing systematic risk, which is critical for the functioning of the financial sector. However, as a middle ground, the EU legislator should address the issue of designated system participants providing vIBAN services to other entities. The most pressing issue seems to be the clarification of the rules for deposit protection. This would mean confirming that end-user deposits in specific vIBANs are protected by the deposit guarantee scheme of the home Member State where the vIBANs payment account provider is authorised. There should also be clarification on the European level that vIBAN services can be offered to both individuals and business entities. This would oblige the local legislators to introduce administrative legislation which would not restrict the vIBAN services offered to business entities.

As future work, it is recommended that an empirical study be conducted, comparing different Member States’ approaches to indirect access to local payment schemes, in particular to designated payment systems. Such a study could include an assessment of the systemic risk connected with such designated schemes. The study could supplement a future proposal for an EU-wide legal regime to organise equal access to payment schemes for established banks and new entrants (such as Payment Institutions and Electronic Money Institutions). The outcome could be the basis for the revision of the Settlement Finality Directive and the regulation of indirect access to payment systems in the form of virtual IBAN services.

Another very important area of study could be to assess the influence of the eventual CBDC currency introduction on the existing payment schemes, especially the possibility of replacing the existing distributed payment schemes with new alternatives.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berentzen, Christoph, Christian Betz, and Heiko Dosch. 2021. Die Commerzbank Auf Dem Weg Ins Ökosystem—Open Banking Als Wegbereiter Für Kollaborative Geschäftsmodelle. Banking & Information Technology 22: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Broby, Daniel. 2021. Financial Technology and the Future of Banking. Financial Innovation 7: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2011. Your Questions on PSD. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/faq-transposition-psd-22022011_en.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Farrow, Gary S. D. 2020. Open Banking: The Rise of the Cloud Platform. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems 14: 128–46. [Google Scholar]

- Górka, Jakub. 2016. IBANs or IPANs? Creating a Level Playing Field between Bank and Non-Bank Payment Service Providers. In Transforming Payment Systems in Europe. Edited by Jakub Górka. Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 182–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Michał. 2020. Ustawa o Usługach Płatniczych. Komentarz. 2 Wydanie. Munich: C.H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, Michał. 2021. Legal Aspects of ‘White-Label’ Banking in the European, Polish and German Law. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBAN. n.d. IBAN Examples, Structure and Length. Available online: https://www.iban.com/structure (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Jun, Jooyong, and Eunjung Yeo. 2021. Central Bank Digital Currency, Loan Supply, and Bank Failure Risk: A Microeconomic Approach. Financial Innovation 7: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, Gang, Özlem Olgu Akdeniz, Hasan Dinçer, and Serhat Yüksel. 2021. Fintech Investments in European Banks: A Hybrid IT2 Fuzzy Multidimensional Decision-Making Approach. Financial Innovation 7: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Tie, Gang Kou, Yi Peng, and Philip S. Yu. 2021. An Integrated Cluster Detection, Optimization, and Interpretation Approach for Financial Data. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masłowski, Michał. 2020. Wybrane aspekty prawne dostępu niebankowych dostawców usług płatniczych do systemów płatności. Monitor Prawa Bankowego 12. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi-Sadigh, Ali, Tayebeh Asgari, and Mohammad Rabiei. 2021. Digital Transformation in the Value Chain Disruption of Banking Services. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 13: 1212–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narodowy Bank Polski. 2019. System Płatniczy w Polsce. Available online: https://www.nbp.pl/systemplatniczy/system/system_platniczy_w_polsce.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Passi, Liliana Fratini. 2018. An Open Banking Ecosystem to Survive the Revised Payment Services Directive: Connecting International Banks and FinTechs with the CBI Globe Platform. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems 12: 335–45. [Google Scholar]

- SWIFT. 2022. IBAN REGISTRY This Registry Provides Detailed Information about All ISO 13616-Compliant National IBAN Formats. Available online: https://www.swift.com/resource/iban-registry-pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Wossidlo, Kay, and Adrian Rochau. n.d. Open Banking: Wie Erfolgreiche API-Plattformen Funktionieren. Banking & Information Technology 22: 55–62.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).