Abstract

Background: Menopause, a critical period during a woman’s life, is characterized by various changes, including disturbances in their oxidative balance and circadian rhythm. Currently, the gut microbiome is suggested as an important participant in these processes. Methods: This study involved 96 menopausal women. Their sleep quality was assessed using three questionnaires: the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). The GSH and GSTP1 contents in the serum were measured by means of immunoassay methods, while the composition of the gut microbiome was determined via molecular genetic methods. Results: E. coli, K. oxytoca, S. aureus, Enterobacter spp., Shigella spp., Streptococcus spp., Prevotella spp., and M. stadmanae were found to correlate with the GSH content in different sleep groups, while the presence of K. oxytoca, S. aureus, Enterococcus spp., K. pneumoniae, and M. stadmanae is also important for the GSH level in several of these groups. F. prausnitzii, S. aureus, P. micra, Acinetobacter spp., and E. rectale are associated with GSTP1 concentration in various sleep groups, while the presence of F. nucleatum and P. micra is also relevant for the GSTP1 content in some of these groups. Conclusions: Thus, in menopausal women, the composition and structure of the gut microbiota are associated with sleep disorders. GSH and GSTP1 are associated with some gut microbiome markers in menopausal women, but these relationships differ in different sleep disorders.

1. Introduction

Sleep is suggested to have a protective role against oxidative damage due to its influence on the efficiency of the antioxidant defense system. Many results support this hypothesis [1,2]. In turn, insufficient sleep in terms of quality and/or longevity may impact a number of biochemical parameters associated with oxidative stress (OS) and inflammation [3]. Synthesized and maintained at high concentrations in all cells, the sulfhydryl-containing tripeptide glutathione (GSH) is a key protector against oxidative stress [4,5]. Glutathione transferase (GST) is also one of the most important antioxidant enzymes, along with glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase [6]. GST plays a major role in cellular redox-dependent processes, catalyzing the conjugation of GSH with non-polar compounds of endogenous and exogenous origin containing electrophilic atoms of sulfur, nitrogen, and phosphorus, as well as with organic hydroperoxides, and protecting the cell from the possible toxic effects of these compounds. GST includes three superfamilies: cytoplasmic, mitochondrial and microsomal. Cytoplasmic GST enzymes can fall into different classes of enzymes, among which GSTP1 is one of the most well studied and is most closely related to the development of human diseases [7,8].

Evidence exists for the interactions between the gut microbiome and OS; however, sleep disturbances could be a mediating factor in this relationship [9]. It is suggested that the gut microbiome regulates its host’s sleep through the gut–brain axis and is involved in sleep disorder development [10,11,12,13]. On the other hand, sleep deficiency apparently leads to microbiome alteration because of the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the gut, affecting bacteria directly or through the immune system [14].

The menopause is one of the most critical periods in a woman’s life, with sleep disorders being one of the main signs of the neurovegetative changes that occur during this process [15]. The menopause represents the termination of reproductive function and ovarian failure, with the decline in female sex hormone levels leading to various short- and long-term changes. Insomnia occurs in more than half of postmenopausal women [16]. Oxidative balance is also affected by menopausal changes, and it has been shown that postmenopausal women have higher levels of ROS compared with premenopausal women, indicating the development of oxidative stress [17,18,19]. Previous results have shown that various bacteria are involved in this process [20]. Meanwhile, the glutathione system is one of the most important participants in the processes maintaining the stability of molecular metabolic parameters [21].

The aim of this study was to reveal the correlations between GSH and GSTP1 levels and the gut microbiome in climacteric women with sleep disturbances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consent

This study was conducted at in the Scientific Centre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems (Irkutsk, Russia). Informed consent was given by the participants in accordance with the Ethical Norms of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. The research protocol was approved by the Committee on Biomedical Ethics of the Scientific Centre (protocol No 3.1.3, dated 28 September 2022).

2.2. Subjects

In the first stage, 112 women were recruited. The primary inclusion criteria were a climacteric status and an age from 45 to 69. In addition, all women reported the presence of amenorrhea or menstrual irregularities, consisting of stable fluctuations (7 days and above) during successive cycles. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a regular menstrual cycle, an AMH level > 1 ng/mL, exacerbation of chronic diseases, diabetes mellitus, oncological disease, infectious diseases, and antibacterial medication in the past three months. Ultimately, the study sample included 96 volunteers. All participants provided written informed consent.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Questionnaire

Grouping was based on the results of three self-administered questionnaires.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) consists of 19 items and is the most widely used retrospective self-report questionnaire assessing sleep quality over the previous month. The questionnaire analyzes seven sleep domains (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medication use, and daily activities). These domains are combined to create a single factor, global sleep quality. The results were assessed according to the standard protocol, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. PSQI > 5 has been validated as a cut-off for sleep disturbances (SD group) across a number of populations [22,23].

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) is a reliable tool for quantifying the perceived severity of insomnia. The ISI is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the nature, severity, and impact of insomnia. The standard period is the “past month”, during which the following dimensions are assessed: difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, difficulty waking early in the morning, sleep dissatisfaction, the impact of sleep disturbances on daytime functioning, the visibility of sleep problems to others, and stress caused by sleep difficulties. The ISI includes 7 items with a total score of 0–28. The classical interpretation according to the guidelines is as follows: control group < 8 points (N group); subthreshold insomnia 8–14 points (SubI group); clinical moderate insomnia 15–21 (I group); and severe insomnia > 21 (SevI group) [24]. However, since the last two groups are basically clinical insomnia groups, they were combined and a 3-group analysis was carried out. Binomial division is also possible, with a threshold equal to 10 suggested as the best option (ISI ≥ 10 indicates SD) [25].

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a subjective measure of sleepiness that is widely used in clinical practice to identify and assess the severity of excessive daytime sleepiness. ESS is an 8-item questionnaire that asks patients about their likelihood of falling asleep in normal situations. ESS has a threshold > 10 (S group) [26,27]—this is not the only cut-off option, but is the most common one [28].

2.3.2. Collection of Materials

Between 8.00 and 10.00 a.m., after 12 h of overnight fasting, venous blood was sampled from the cubital vein of each subject into a tube with a clot activator to obtain serum. Then, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 1500× g. The remaining blood serum was collected in an Eppendorf tube and frozen. Serum was used to assess the AMH, GSH, and GSTP1 concentrations. Also, each participant provided fresh stool samples on the same day. Feces were collected in test tubes with beads for material homogenization (BashingBead; Zymo Research, Tustin, CA, USA). All samples were stored at −80 °C prior to the assays being carried out.

2.3.3. GSH

The GSH level (µg/mL) in serum was measured with the ELISA kit for Research Use Only “BLUE GENE” E01G0233 on “ELx808IU” analyzer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3.4. GSTP1

GSTP1 concentration (ng/mL) in serum was determined with the ELISA kit for Research Use Only “BLUE GENE” E01G0442 on “ELx808IU” analyzer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3.5. Gut Microbiome

The fecal DNA of each subject was extracted with the Stool Genomic DNA Kit (CWBIO, Beijing, China) according to the routine protocol. The quantitative assessment of the microbiocenosis state was investigated with RT-PCR, with fluorescent detection of amplification results using the “COLONOFLOR” reagent kit (Alphalab, Saint Petersburg, Russia) on a CFX-96 thermocycler (BioRad, San Mateo, CA, USA). Samples with concentrations ranging from 1 to 2 ng/μL were considered in this study. The Colonoflor-16 (premium) kit combines the Colonoflor-16 (biocenosis) and Colonoflor-16 (metabolism) reagent kits and allows for the quantitative (lg CFU/g) determination of the total bacterial mass, Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Bacteroides spp., Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. thetaiotaomicron), Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prau), Escherichia coli (E. coli), Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila), Enterococcus spp., enteropathogenic E. coli, Klebsiella pneumonia (K. pneumonia), Klebsiella oxytoca (K. oxytoca), Candida spp., Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens), Proteus vulgaris/mirabilis (P. vulgaris/mirabilis), Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum), Parvimonas micra (P. micra), Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Blautia spp., Acinetobacter spp., Eubacterium rectale (E. rectale), Streptococcus spp., Roseburia inulinivorans (R. nulinivorans), Prevotella spp., Methanobrevibacter smithii (M. smithii), Methanosphaera stadmanae (M. stadmanae), Ruminococcus spp., and the Bacteroides spp./F. prau ratio.

2.3.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with R Studio 2024.12.1 Build 563. The following libraries were used: “ggplot2”, “readxl”, “table1”, “boot”, and “dplyr”. Data in tables are presented as Me [Q1; Q2]. To calculate correlation, the Spearman rank correlation test was used, and 95% confidence intervals for Spearman correlations were obtained using the bootstrap method with 10,000 resamples. To compare two groups, the Wilcoxon rank sum exact test was applied. To compare several groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was carried out. Subsequently, to identify groups with significant differences, the pairwise Wilcoxon rank test with Bonferroni correction was applied. Values of p < 0.05 (comparison of two groups), p < 0.017 (comparison of three groups), or p < 0.013 (comparison of four groups) were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of PSQI Groups

Based on PSQI scores, participants were categorized into two groups (Table S1, Supplementary Material). Three bacterial parameters differed significantly between these groups, namely, Enterococcus spp. (p = 0.025), Shigella spp. (p = 0.04), and Clostridium perfringens (p = 0.013), with the levels of these bacteria being higher in the group with sleep disorders. Moreover, the differences in Shigella spp. were significant, since their values in the group with poor sleep quality were above Q3.

3.2. Characteristics of ISI Groups

One method of analyzing the ISI questionnaire involves binomial grouping (Table S2, Supplementary Material). The total bacterial mass is lower in the insomniac sleep disorder group (p = 0.03). Additionally, significant differences were detected for Clostridium perfringens (p = 0.002), Streptococcus spp. (p = 0.03), and Shigella spp. (p = 0.03). The differences in Shigella spp. were significant, as their values in the group with poor sleep quality were above Q3, as in PSQI grouping.

The four-group ISI classification provides the following breakdown of groups (Table S3, Supplementary Material). According to the results, a non-significant trend is observed for Akkermansia muciniphila, for which the content is lower in the I group compared with the SevI group (p = 0.039). Clostridium perfringens level was higher in the I group than in the N group (p = 0.008) and was numerically higher in the SubI and SevI groups compared with the N group.

We combined the moderate (I) and severe (SevI) insomnia groups to create a single clinical insomnia group (Table S4, Supplementary Material). A higher abundance of Clostridium perfringens (p = 0.007) was detected in the insomnia group compared with the control. Moreover, the GSTP1 (p = 0.034) and Parvimonas micra (p = 0.046) levels in the insomnia group were numerically lower than in the subclinical insomnia group.

3.3. Characteristics of ESS Groups

The Epworth scale questionnaire was used to assess the daytime sleepiness rate. According to the results, the whole sample was divided into two groups (Table S5, Supplementary Material). The content of Bifidobacterium spp. (p = 0.04), Eubacterium rectale (p = 0.04), and Prevotella spp. (p = 0.02) was significantly higher in the excessive daytime sleepiness group compared with the control.

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between GSH in Serum and Bacterial Parameters

According to the results, the GSH content in serum is associated with several gut bacteria in the insomnia group only (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spearman correlation between GSH in serum and bacterial parameters in ISI groups.

S. aureus was also correlated with GSH in the subclinical insomnia group, but this correlation was stronger, in the insomnia group. Thus, in this group, three species and three genera positively correlate with the GSH content in the serum. However, this tendency disappears in the severe insomnia group. One of the reasons for this could be the size of this group, and hence one transformation was implemented. Combining the two groups (insomnia and severe insomnia) into one yielded the following results: K. oxytoca, S. aureus, and M. stadmanae were still associated with GSH, but only the relationship between M. stadmanae and GSH remained strong. Meanwhile, Prevotella spp. correlated with this parameter insignificantly. The binomial grouping approach partly confirmed this association.

The analysis of the other questionnaires revealed additional significant bacteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation between GSH in serum and bacterial parameters in groups.

For the PSQI groups, we only obtained two bacteria with moderate correlations: S. aureus and Shigella spp. Notably, S. aureus did not correlate with GSH in the serum of the control group of either questionnaire with any type of division, but showed moderate to strong correlations in the sleep disorder groups.

Also, M. stadmanae exhibited a weak correlation with GSH in the sleep disorder group of PSQI; however, it showed a strong association in the excessive daytime sleepiness group compared with a weak association in the control group.

Furthermore, there was an inverse relationship between GSH in the serum and E. coli in the excessive daytime sleepiness group exclusively, as well as between GSH and Streptococcus spp.

3.5. Correlation Analysis Between GSTP1 in Serum and Bacterial Parameters

Along with GSH in the serum, the GSTP1 concentration was measured. These parameters correlated at a high level (p = 2.112 × 10−13, rho = 0.69). However, the GSTP1 correlation profile was different (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman correlation between GSTP1 and bacterial parameters in ISI groups.

Notably, S. aureus again showed significant results. In the insomnia group, Acinetobacter spp. was also significantly associated with GSTP1 concentration. In the joint group, E. rectale showed a moderate correlation.

On the other hand, in the PSQI groups, the situation was different (Table 4), with an inverse relationship between GSTP1 and F. prausnitzii being detected in the control group.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation between GSTP1 and bacterial parameters in groups.

P. micra showed a weak correlation with GSTP1 in the ISI SD group, but this correlation was of moderate strength in the excessive daytime sleepiness group.

3.6. GSH and GSTP1 Levels in the Presence of Gut Bacteria in Total Group

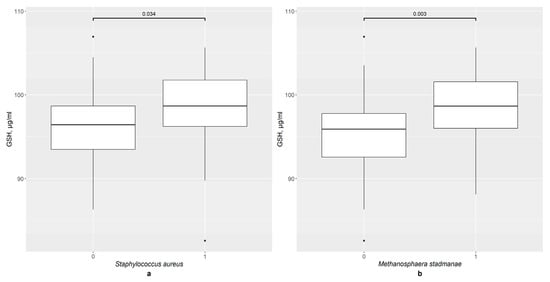

In the second step of this study, the GSH content in the serum was analyzed in the different groups according to the presence of certain bacteria. In the overall sample, the presence of two bacteria significantly impacted the GSH level: S. aureus (Figure 1a), with p = 0.034, and M. stadmanae (Figure 1b) with p = 0.003. Therefore, a more precise analysis was carried out.

Figure 1.

The difference in GSH content in groups: (a) 0—S. aureus not detected (n = 80), 1—S. aureus detected (n = 16); (b) 0—M. stadmanae not detected (n = 65), 1—M. stadmanae detected (n = 31).

3.7. GSH and GSTP1 Levels in the Presence of Gut Bacteria in ISI Groups

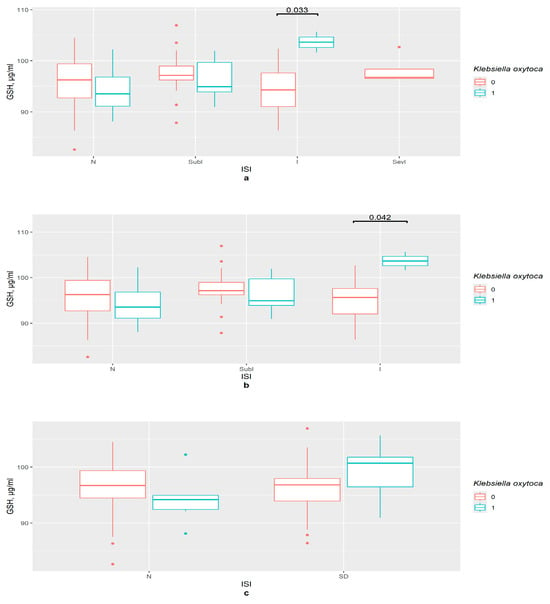

Firstly, the ISI groups were investigated. K. oxytoca influences GSH content in the insomnia group (p < 0.05), not in the subclinical insomnia and the control groups (Figure 2a,b). The binomial ISI division provided no statistically significant results (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

The difference in GSH content in groups (a) 0—K. oxytoca not detected, 1—K. oxytoca detected, N—control (n0 = 37, n1 = 4), SubI—subclinical insomnia group (n0 = 24, n1 = 7), I—insomnia group (n0 = 17, n1 = 2), SevI—severe insomnia group, ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire; (b) 0—K. oxytoca not detected, 1—K. oxytoca detected, N—control (n0 = 37, n1 = 4), SubI—subclinical insomnia group (n0 = 24, n1 = 7), I—combining insomnia group (I and SevI groups) (n0 = 21, n1 = 3), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire; (c) 0—K. oxytoca not detected, 1—K. oxytoca detected, N—control (n0 = 46, n1 = 6), SD—insomniac sleep disorders group (n0 = 36, n1 = 8), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire.

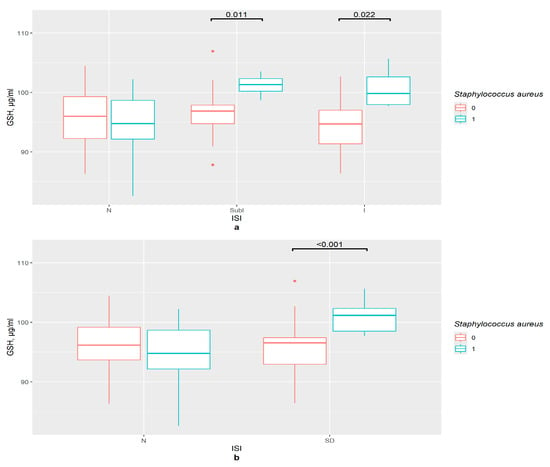

S. aureus’ presence was associated with an increase in the GSH content in the serum of the subclinical (p = 0.011) and clinical insomnia groups (p = 0.022), but not in that of the control group (Figure 3a). This supports the data obtained in the correlation tests. In the ISI insomnia group with binomial division, GSH concentration was significantly higher in S. aureus’ presence (p < 0.001), while there was no such tendency for the control group (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

The difference in GSH content in groups (a) 0—S. aureus not detected, 1—S. aureus detected, N—control (n0 = 34, n0 = 7), SubI—subclinical insomnia group (n0 = 27, n1 = 4), I—combining insomnia group (I and SevI groups) (n0 = 19, n1 = 5), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire; (b) 0—S. aureus not detected, 1—S. aureus detected, N—control (n0 = 45, n1 = 7), SD—insomniac sleep disorders group (n0 = 35, n1 = 9), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire.

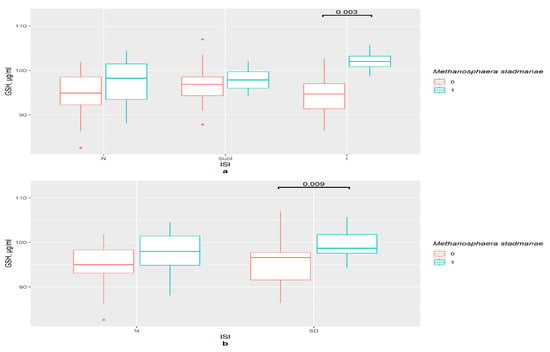

M. stadmanae influenced the GSH content in the serum of the insomnia group (p = 0.001) and the insomnia and severe insomnia joint group (p = 0.003) (Figure 4a). Binomial division presented similar results (p = 0.009) (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

The difference in GSH content in groups (a) 0—M. stadmanae not detected, 1—M. stadmanae detected, N—control (n0 = 30, n1 = 11), SubI—subclinical insomnia group (n0 = 19, n1 = 12), I—combining insomnia group (I and SevI groups) (n0 = 16, n1 = 8), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire; (b) 0—M. stadmanae not detected, 1—M. stadmanae detected, N—control (n0 = 36, n1 = 16), SD—insomniac sleep disorders group (n0 = 29, n1 = 15), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire.

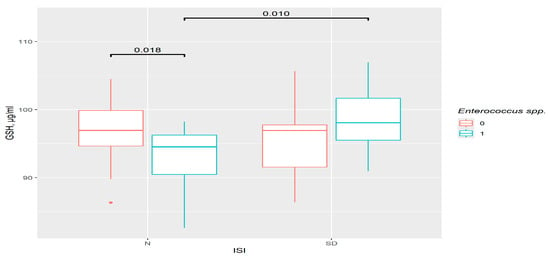

This type of analysis provides one additional result. Insomniac disorders were correlated with a relatively higher level of GSH as compared to the control in the presence of Enterococcus spp. (p = 0.01). In the control group, the GSH level was significantly lower in presence of this genus (p = 0.018) (Figure 5). So, in this case, the difference was not in the insomnia group, but in the control group, suggesting that the participation of bacteria is important.

Figure 5.

The difference in GSH content in groups. 0—Enterococcus spp. not detected, 1—Enterococcus spp. detected. N—control (n0 = 38, n1 = 14), SD—insomniac sleep disorders group (n0 = 28, n1 = 16), ISI—insomnia severity index questionnaire.

The concentration of GSTP1 is also different in the presence of P. micra, but no associations with sleep disturbances were revealed.

3.8. GSH and GSTP1 Levels in the Presence of Gut Bacteria in PSQI Groups

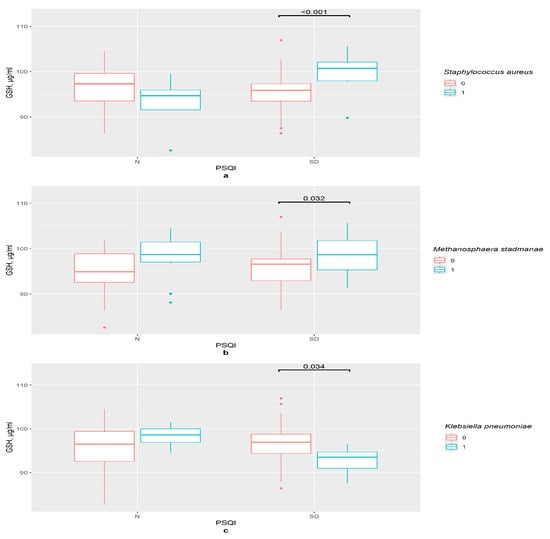

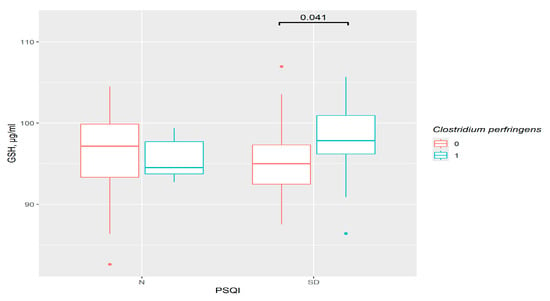

In the PSQI control group, there were no important differences in GSH serum concentration between groups divided by the presence or absence of certain bacteria. However, sleep disturbances were associated with variations in the GSH level (p = 0.001). The combination of two factors, namely the presence of S. aureus and sleep problems, had connections with the increase in GSH content in the serum (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

The difference in GSH content in groups: (a) 0—S. aureus not detected, 1—S. aureus detected, N—control (n0 = 31, n1 = 4), SD—sleep disturbance group (n0 = 49, n1 = 12), PSQI—Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; (b) 0—M. stadmanae not detected, 1—M. stadmanae detected, N—control (n0 = 23, n1 = 12), SD—sleep disturbance group (n0 = 42, n1 = 19), PSQI—Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; (c) 0—K. pneumoniae not detected, 1—K. pneumoniae detected, N—control (n0 = 30, n1 = 5), SD—sleep disturbance group (n0 = 55, n1 = 6), PSQI—Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Noticeably, GSH content was higher in women with sleep disturbances in the presence of M. stadmanae compared with the group with an absence of this bacteria (p = 0.032); however, no significant differences between PSQI groups were observed (Figure 6b).

So, for these two bacteria, sleep disturbances were an important factor for GSH content level. Two other bacteria provided no significant results when other methods of dividing the groups were applied. In the presence of K. pneumoniae, the GSH level is lower in the sleep disturbances group (p = 0.034) (Figure 6c).

A higher level of GSH was observed in the C. perfringens group with sleep disorders (p = 0.041) (Figure 7). However, the variations between PSQI groups in the presence or absence of this bacteria were invalid.

Figure 7.

The difference in GSH content in groups: 0—C. perfringens not detected, 1—C. perfringens detected, N—control (n0 = 30, n1 = 5), SD—sleep disturbance group (n0 = 39, n1 = 22), PSQI—Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

GSTP1 content fluctuations were non-significant.

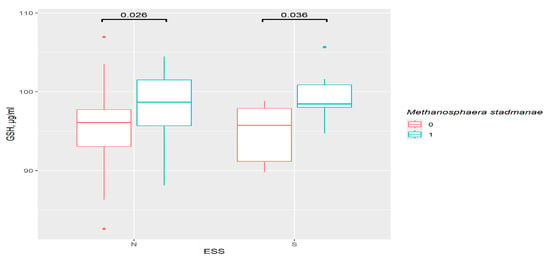

3.9. GSH and GSTP1 Levels in the Presence of Gut Bacteria in ESS Groups

In ESS groups, the only important result was the increase in GSH in presence of M. stadmanae (p = 0.026 in the control and p = 0.036 in the excessive daytime sleepiness group). However, this was related to the bacteria, rather than sleep disorders, as observed for the PSQI (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The difference in GSH content in groups: 0—M. stadmanae not detected, 1—M. stadmanae detected, N—control (n0 = 56, n1 = 23), S—excessive daytime sleepiness (n0 = 9, n1 = 8), ESS—Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

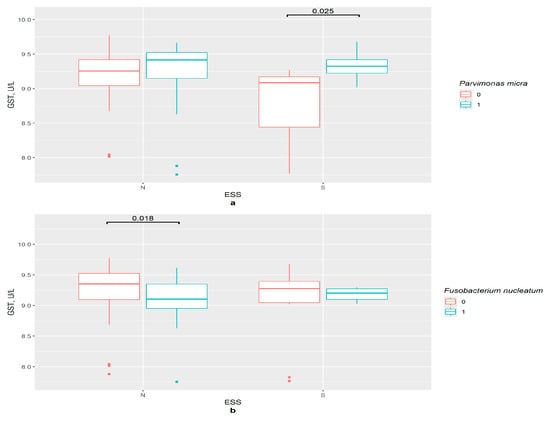

In the absence of P. micra, the GSTP1 concentration was lower in the excessive daytime sleepiness group compared with the control (p = 0.025) (Figure 9a). In the control group, the GSTP1 content was lower in the presence of F. nucleatum (p = 0.018). However, no differences between ESS groups in the F. nucleatum absence/presence subgroups were observed (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

The difference in GSTP1 content in groups:: (a) 0—P. micra not detected, 1—P. micra detected, N—control (n0 = 49, n1 = 30), S—excessive daytime sleepiness (n0 = 7, n1 = 10), ESS—Epworth Sleepiness Scale; (b) 0—F. nucleatum not detected, 1—F. nucleatum detected, N—control (n0 = 60, n1 = 19), S—excessive daytime sleepiness (n0 = 12, n1 = 5), ESS—Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

3.10. GSH and GSTP1 Association with Bacteria in Different Groups with Sleep Disorders

Many species and genera are therefore associated with glutathione system fluctuations. GSH in the serum was mostly higher in cases of sleep disturbances and in the presence of certain bacteria. Moreover, it was correlated with bacteria content in the gut (Table 5).

Table 5.

GSH Association with Bacteria in Different Groups with Sleep Disorders.

GSH level in the serum correlated with GSTP1 concentration; however, the GSTP1–microbiome correlation profile was different (Table 6).

Table 6.

GSTP1 association with bacteria in different groups with sleep disorders.

4. Discussion

In recent years, studies of the human microbiome have led to development of the gut–brain axis theory, which proposes a relationship between the gut bacterial community, along with its metabolites and chemical compounds, and physiological and pathological processes in the brain. The number of studies that have addressed the link between the menopause, the gut microbiome, and sleep is relatively small. Moreover, sleep is not a standalone characteristic, and is rather considered as part of a set of other factors [29]. It must be mentioned that the profiles of people with insomniac disorder investigated in other studies do differ. Some authors have suggested that Prevotella plays an important role in insomnia, potentially affecting sleep by regulating amino acid metabolism and promoting inflammation [13], because Prevotella correlates with serum indoxyl sulfate levels [30]. Indoxyl sulfate, a tryptophan derivative, is produced by intestinal bacteria. It is a uremic toxin, promoting inflammation and oxidative stress [31]. In our study, the level of Prevotella was found to be higher in the group with excessive daytime sleepiness and was associated with GSH only in the insomnia group, and not in the control or subclinical insomnia group. Therefore, it is possible that under sleep deficiency conditions, this bacteria may be associated with oxidative stress development.

Another study revealed that Streptococcus’ relative abundance was considerably higher in insomniacs compared to healthy controls [32]. Our results reveal only a negative correlation between Streptococcus and GSH in the group with the excessive daytime sleepiness. There are other controversial reports regarding Streptococcus trends in patients with insomnia disorder [33]. Thus, more precise investigations are needed to evaluate these results.

The investigation of the correlation between gut content and serum metabolites revealed that the levels of the Bacteroidaceae and Ruminococcaceae families significantly decreased in patients with insomnia disorder compared with healthy controls. On the other hand, levels of the Prevotellaceae family increased. At the genus level, a significant decrease in levels of the genus Bacteroides and a significant increase in levels of the genus Prevotella were observed for patients with insomnia disorder, compared with healthy controls [34].

In our study, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii showed a negative correlation with GSTP1 in the PSQI control group and a positive correlation in the ISI insomniac group. It is claimed that the increased resistance of the bacteria correlates with the presence of oxygen superoxide or ROS-detoxifying enzymes and genes [35]. Oxidative stress could be an unfavorable condition for this genus, so in the control, the decreased GSTP1 concentration might mean a more preferable condition for this bacteria; meanwhile, in the sleep deficiency group, the increased GSTP1 level may be aimed at reducing oxidative stress.

In an animal model, the relative abundances of Escherichia–Shigella increased in the induced insomnia group [36]. An association between Escherichia–Shigella content and dietary habits in insomnia was also detected [37]. According to our results, E. coli negatively correlates with GSH only in the excessive daytime sleepiness group. However, Shigella spp. demonstrates a moderate association with GSH in the insomniac and sleep disorder groups for all questionnaires. It is notable that two bacteria species display similar results—S. aureus and M. stadmanae apparently have a strong association with GSH content in sleep deficiency terms. Unlike Shigella spp., these significant results were detected not only in quantitative but also in qualitative analysis of this bacteria’s abundance. S. aureus is related to GSTP1 content in the insomnia group as well.

We reported previously that M. stadmanae methanogen is associated with a higher level of TBARS in the group with sleep disorders. Moreover, TBARS and advanced oxidation protein products increase in the group with sleep disorders compared to the control in the sample with M. stadtmanae in the gut [20]. Therefore, the presented parameters appear promising for further investigation.

E. coli and Klebsiella overgrowth is assumed as the pathophysiological mechanism behind gut dysbiosis [38]. K. oxytoca positively correlates with GSH content in the serum in insomnia groups, and GSH level was higher in the presence of this bacteria. On the other hand, K. pneumoniae’s presence is associated with a lower GSH level in the SD group of PSQI. The indole production ability is the main difference between these two bacteria [39]. Indole derivatives influence GSTP1 concentration [40]. Despite a direct impact on GSTP1 not being observed in our study, this mechanism could explain the difference in GSH results. It is well known that indole derivatives mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation [41,42]. Therefore, it is possible that the glutathione system is one of the main ways for this activity to occur.

It is possible that oxidative stress or sleep alterations may be a reason for or a consequence of microbial fluctuations. GSH supplementation influences gut microbiome diversity. The abundance of the phylum Proteobacteria significantly decreased, as well as that of pathogenic Escherichia/Shigella; however, genera such as Megasphaera, Bacteroides, and Megamonas were found to be significantly enriched after supplementation [43]. On the other hand, modeling postmenopausal conditions in mice showed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes regulate the key GSH enzyme glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic subunit and inhibit mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species accumulation via the cAMP response element-binding (CREB) pathway. This affects the de novo synthesis of GSH [44]. Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiota is interconnected with circadian rhythms. Short-chain fatty acids or bile acids produced by the gut microbiota may mediate this relationship. The influence of microbiota metabolites on circadian rhythms is extensive and is linked to their other functions, such as their participation in energy metabolism and immune responses [45,46].

Menopause-related hormone changes may also affect the gut microbiome composition. It has been suggested that the depletion of ovarian steroid hormones has an impact on the deconjugation of glucuronide or sulfate groups from sex steroid hormones, allowing for enterohepatic recirculation. This is supported by studies which revealed differences in the gut content of individuals of different genders. Additionally, changes were also detected after puberty. On the other hand, the complex effects of the menopause have been investigated insufficiently [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], with information about the state of the glutathione system in menopausal women with insomnia clearly lacking. According to previous results, the menopausal status is clearly relevant for the state of the glutathione system [21].

One potential mechanism linking the gut microbiota and sleep disorders is the hormone melatonin [55], which effectively decreases oxidative stress markers and increases the levels of antioxidative factors, including GSH [56,57]. On the other hand, being produced in the gastrointestinal tract and having local and systemic effects, melatonin is closely connected to the intestinal microbiota [58]. Melatonin alters the composition of the gut microbiota, decreasing or increasing the levels of certain genera, restoring disturbances caused by sleep problems, stress, or other negative factors. The mechanism of this effect is debated, but it is believed that butyrate plays an important role in mediating it. It is also suggested that the composition of the microbiome influences melatonin levels [55]. There is much evidence of the important role of melatonin in the association between oxidative stress and the gut microbiome, but it should be mentioned that most studies in this field are based on animal models, with a lack of human investigations [9,59]. It is possible that the further research in this field may provide more significant information about the discussed processes.

There are limitations to this study, the first of which is the small sample size employed. However, to justify the obtained results, the groups were combined, and additional methods of dividing the sample were applied. Meanwhile, taxa with insufficient registered results were tested as quality factors. Therefore, the findings which were not registered in multiple tests should be interpreted cautiously. Secondly, the disproportionate distribution of women across groups could cause difficulties in result assessment. Further investigations are therefore needed. Additionally, the fact that the questionnaires were self-administered might lead to misunderstandings and further mistakes with the grouping of volunteers. However, we provided consultation to minimize unfavorable consequences. Lastly, the sleep questionnaires used have not been not validated for our region. On the other hand, many studies have proven their reliability.

5. Conclusions

The association between certain gut bacteria in menopausal women and serum oxidative stress markers was revealed, with the key role of sleep disturbances in this association being determined. It is possible that the correlations between the gut microbiome and oxidative stress in menopausal women with sleep disturbances extend beyond the glutathione system in the serum, and further research may focus on other parameters affecting this relationship.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathophysiology33010003/s1, such as characteristics of PSQI groups and the total sample; characteristics of ISI groups, binomial division; characteristics of ISI groups, standard breakdown; characteristics of ISI groups, combining insomniac disorders in one group; characteristics of ESS groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. (Natalya Semenova) and L.K.; methodology, N.S. (Natalya Semenova) and N.G.; software, N.G.; validation, N.G. and I.M.; formal analysis, N.S. (Natalya Semenova); investigation, O.N., N.B., E.K., E.N. and N.S. (Nadezhda Smurova); resources, N.S. (Natalya Semenova); data curation, N.S. (Natalya Semenova); writing—original draft preparation, N.G.; writing—review and editing, N.S. (Natalya Semenova), S.K. and L.K.; visualization, N.S. (Natalya Semenova); supervision, S.K.; project administration, N.S. (Natalya Semenova), N.B. and L.K.; funding acquisition, N.S. (Natalya Semenova) and L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by basic scientific research No 121022500180-6.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Committee on Biomedical Ethics of this Scientific Centre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems (Irkutsk, Russia) (protocol No 3.1.3 dated 28 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed with the use of equipment from the Collective research center “Center for the development of progressive personalized technologies for health” SC FHHRP, Irkutsk.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Semenova, N.V.; Madaeva, I.M.; Brichagina, A.S.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Kolesnikova, L.I. 8-Hydroxy-2′-Deoxyguanosine as an Oxidative Stress Marker in Insomnia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W. Association of oxidative balance score with sleep quality: NHANES 2007–2014. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagasabai, T.; Riddell, M.C.; Ardern, C.I. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidant Micronutrients as Mediators of the Relationship Between Sleep, Insulin Sensitivity, and Glycosylated Hemoglobin. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 888331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Berk, M.; Campochiaro, P.A.; Jaeschke, H.; Marenzi, G.; Richeldi, L.; Wen, F.-Q.; Nicoletti, F.; Calverley, P.M.A. The Multifaceted Therapeutic Role of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) in Disorders Characterized by Oxidative Stress. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 19, 1202–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, A. Glutathione metabolism. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budkowska, M.; Cecerska-Heryć, E.; Marcinowska, Z.; Siennicka, A.; Dołęgowska, B. The Influence of Circadian Rhythm on the Activity of Oxidative Stress Enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorova, T.; Tereshkina, E.; Savushkina, O.; Boksha, I.; Vorobyova, E.; Burbaeva, G. Activity of Platelet Enzymes Glutathione Reductase and Glutathione-S-Transferase in Males and Females of Different Age Groups. Int. Res. J. 2020, 12, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deponte, M. Glutathione catalysis and the reaction mechanisms of glutathione-dependent enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 3217–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.; Garashchenko, N.; Kolesnikov, S.; Darenskaya, M.; Kolesnikova, L. Gut Microbiome Interactions with Oxidative Stress: Mechanisms and Consequences for Health. Pathophysiology 2024, 31, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, Y.; Fan, F.; Zhang, B. The Role of Microbiome in Insomnia, Circadian Disturbance and Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, V.; Gibbons, S.M.; Martinez, K.; Hutchison, A.L.; Huang, E.Y.; Cham, C.M.; Pierre, J.F.; Heneghan, A.F.; Nadimpalli, A.; Hubert, N.; et al. Effects of Diurnal Variation of Gut Microbes and High-Fat Feeding on Host Circadian Clock Function and Metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badran, M.; Khalyfa, A.; Ericsson, A.; Gozal, D. Fecal microbiota transplantation from mice exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits sleep disturbances in naïve mice. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 334, 113439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, B.; Sheng, D.; Yang, J.; Fu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Gai, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Multiomics Analysis Reveals Aberrant Metabolism and Immunity Linked Gut Microbiota with Insomnia. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00998-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Dor, Y.K.; Nambara, K.; Pollina, E.A.; Lin, C.; Greenberg, M.E.; Rogulja, D. Sleep Loss Can Cause Death through Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Gut. Cell 2020, 181, 1307–1328.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.V.; Madaeva, I.M.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Solodova, E.I.; Kolesnikova, L.I. Insomnia in Peri- and Postmenopausal Women: Plasma Lipids, Lipid Peroxidation and Some Antioxidant System Parameters. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 8, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachul, H.; De Campos, B.H.; Lucena, L.; Tufik, S. Sleep During Menopause. Sleep Med. Clin. 2023, 18, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E.; Al-Rawas, A.M.; Al-Maqbali, M.; Al-Saleh, M.; Enriquez, M.B.; Al-Siyabi, S.; Al-Hashmi, K.; Al-Lawati, I.; Bulthuis, M.L.C.; et al. Systemic Oxidative Stress Is Increased in Postmenopausal Women and Independently Associates with Homocysteine Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassalle, C.; Sciarrino, R.; Bianchi, S.; Battaglia, D.; Mercuri, A.; Maffei, S. Sex-related differences in association of oxidative stress status with coronary artery disease. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, 414–419.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leanza, G.; Conte, C.; Cannata, F.; Isgrò, C.; Piccoli, A.; Strollo, R.; Quattrocchi, C.C.; Papalia, R.; Denaro, V.; Maccarrone, M.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Postmenopausal Women with or without Obesity. Cells 2023, 12, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.V.; Garashchenko, N.E.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Nikitina, O.A.; Novikova, E.A.; Smurova, N.E.; Klimenko, E.S.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Madaeva, I.M.; Kolesnikova, L.I. Methanogen Methanosphaera stadtmanae in women intestine. Influence on the free radical oxidation and sleep quality in menopause. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2025, 179, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.V.; Madaeva, I.M.; Brichagina, A.S.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Kolesnikova, L.I. Glutathione Component of Antioxidant Status in Menopausal Women with Insomnia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 173, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitser, J.; Allen, I.E.; Falgàs, N.; Le, M.M.; Neylan, T.C.; Kramer, J.H.; Walsh, C.M. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) responses are modulated by total sleep time and wake after sleep onset in healthy older adults. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omachi, T.A. Measures of sleep in rheumatologic diseases: Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Functional Outcome of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, S287–S296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric Indicators to Detect Insomnia Cases and Evaluate Treatment Response. Sleep 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A New Method for Measuring Daytime Sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechat, B.; Hirotsu, C.; Appleton, S.; Younes, M.; Adams, R.J.; Vakulin, A.; Hansen, K.; Zajamsek, B.; Wittert, G.; Catcheside, P.; et al. A novel EEG marker predicts perceived sleepiness and poor sleep quality. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fang, X.; Xu, C.; Pan, N.; Wang, Y.; Xue, T.; Zhang, M.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J. Epworth sleepiness scale is associated with hypothyroidism in male patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1010646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, K.M.; Linenberg, I.; Hall, W.L.; Kadé, K.; Franks, P.W.; Davies, R.; Wolf, J.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Asnicar, F.; Segata, N.; et al. Menopause is associated with postprandial metabolism, metabolic health and lifestyle: The ZOE PREDICT study. EBioMedicine 2022, 85, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Chen, B.; Wu, J.; Shao, R.; Li, Y. A multi-omics study of the association between insomnia with objective short sleep duration phenotype and high blood pressure. Sleep 2025, 48, zsaf030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chern, Y.-B.; Tsai, J.-P.; Liu, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Hsu, B.-G. Serum Indoxyl Sulfate as a Potential Biomarker of Peripheral Arterial Stiffness in Patients with Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3 to 5. Toxins 2025, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Liu, Z. The relationship between gut microbiota and insomnia: A bi-directional two-sample Mendelian randomization research. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1296417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Chan, Y.L.; Chan, N.Y.; Wing, Y.K.; Chan, F.K.L.; Su, Q.; Ng, S.C. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Insomnia: A Systematic Review of Case–Control Studies. Life 2025, 15, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Zou, Z.; Dou, S.; Li, G.; Yan, F.; Chen, B.; Li, Y. Alterations in Gut Microbiota Are Correlated With Serum Metabolites in Patients with Insomnia Disorder. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 722662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botin, T.; Ramirez-Chamorro, L.; Vidic, J.; Langella, P.; Martin-Verstraete, I.; Chatel, J.-M.; Auger, S. The Tolerance of Gut Commensal Faecalibacterium to Oxidative Stress Is Strain Dependent and Relies on Detoxifying Enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00606-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qi, X.; Wang, S.; Tian, C.; Zou, T.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Banxia-Yiyiren alleviates insomnia and anxiety by regulating the gut microbiota and metabolites of PCPA-induced insomnia model rats. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1405566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ye, J.; Wen, Y.; Liu, L.; Cheng, B.; Cheng, S.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, F. Evaluating the Effects of Diet-Gut Microbiota Interactions on Sleep Traits Using the UK Biobank Cohort. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamation, R. Endogenous Ethanol Production in the Human Alimentary Tract: A Literature Review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 40, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AL-Khikani, F.O.; Abadi, R.; Ayit, A. Emerging carbapenemase Klebsiella oxytoca with multidrug resistance implicated in urinary tract infection. Biomed. Biotechnol. Res. J. 2020, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özaslan, M.S. Investigation of Potential Effects of Some Indole Compounds on the Glutathione S-Transferase Enzyme. Biochemistry 2024, 89, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yang, P.-N.; Lo, Y.-S.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-M.; Wu, Y.-R.; Yao, C.-F.; Chang, K.-H.; et al. Investigating Therapeutic Effects of Indole Derivatives Targeting Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Neurotoxin-Induced Cell and Mouse Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Lee, H.; Park, S.-H.; Hong, S.H.; Song, K.S.; Cha, H.-J.; Kim, G.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-S.; et al. Indole-6-carboxaldehyde prevents oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage and apoptosis in C2C12 skeletal myoblasts by regulating the ROS-AMPK signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2020, 16, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaike, A.H.; Kalamkar, S.D.; Gajjar, V.; Divate, U.; Karandikar-Iyer, S.; Goel, P.; Shouche, Y.S.; Ghaskadbi, S.S. Effect of long-term oral glutathione supplementation on gut microbiome of type 2 diabetic individuals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2023, 370, fnad116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhuge, A.; Li, L.; Ni, S. Gut microbiota modulates osteoclast glutathione synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis in mice subjected to ovariectomy. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, K.; Chang, E.B. Intersection of the gut microbiome and circadian rhythms in metabolism. Trends Endocr. Metab. 2020, 1, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, J.M.; Ammar, R.M.; Tenchov, R.; Lemmel, S.; Kelber, O.; Grieswelle, M.; Zhou, Q.A. Gut microbiome–brain alliance: A landscape view into mental and gastrointestinal health and disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 10, 1717–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Lin, J.; Qi, Q.; Usyk, M.; Isasi, C.R.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Derby, C.A.; Santoro, N.; Perreira, K.M.; Daviglus, M.L.; et al. Menopause Is Associated with an Altered Gut Microbiome and Estrobolome, with Implications for Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. mSystems 2022, 7, e0027322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwa, M.; Plottel, C.S.; Blaser, M.J.; Adams, S. The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djw029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsunenko, T.; Rey, F.E.; Manary, M.J.; Trehan, I.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Baldassano, R.N.; Anokhin, A.P.; et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012, 486, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falony, G.; Joossens, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Wang, J.; Darzi, Y.; Faust, K.; Kurilshikov, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Vandeputte, D.; et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science 2016, 352, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhernakova, A.; Kurilshikov, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Schirmer, M.; Vatanen, T.; Mujagic, Z.; Vila, A.V.; Falony, G.; Vieira-Silva, S.; et al. Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science 2016, 352, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, T.; Vich Vila, A.; Garmaeva, S.; Jankipersadsing, S.A.; Imhann, F.; Collij, V.; Bonder, M.J.; Jiang, X.; Gurry, T.; Alm, E.J.; et al. Analysis of 1135 gut metagenomes identifies sex-specific resistome profiles. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, T.; Naito, Y.; Inoue, R.; Kashiwagi, S.; Uchiyama, K.; Mizushima, K.; Tsuchiya, S.; Dohi, O.; Yoshida, N.; Kamada, K.; et al. Differences in gut microbiota associated with age, sex, and stool consistency in healthy Japanese subjects. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Kelley, S.T.; Chen, Y.; Escobar, J.S.; Mueller, N.T.; Ley, R.E.; McDonald, D.; Huang, S.; Swafford, A.D.; Knight, R.; et al. Age- and Sex-Dependent Patterns of Gut Microbial Diversity in Human Adults. mSystems 2019, 4, e00261-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garashchenko, N.E.; Semenova, N.V.; Kolesnikova, L.I. Melatonin and gut microbiome. Acta Biomed. Sci. 2024, 9, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, T.; Lee, T.H. Cellular Mechanisms of Melatonin: Insight from Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michurina, S.V.; Ishchenko, I.Y.; Bochkareva, A.L.; Arkhipov, S.A.; Kolesnikov, S.I. Effect of melatonin on expression of apoptosis regulator proteins BCL-2 and BAD in ovarian follicular apparatus after high temperature exposure. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 170, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Taghizadieh, M.; Mehdizadehfar, E.; Hasani, A.; Fard, J.K.; Feizi, H.; Hamishehkar, H.; Ansarin, M.; Yekani, M.; Memar, M.Y. Gut microbiota in neurological diseases: Melatonin plays an important regulatory role. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonmatí-Carrión, M.-Á.; Rol, M.-A. Melatonin as a Mediator of the Gut Microbiota–Host Interaction: Implications for Health and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.