Simple Summary

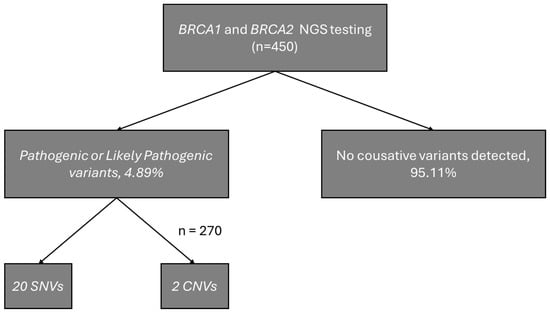

Among the Polish population, around 4% of breast cancer patients and 10% of ovarian cancer patients have pathogenic variants of the BRCA1 gene, whereas variants of the BRCA2 gene are uncommon. Short-read sequencing provides a comprehensive range of data, including the detection of CNVs (copy number variants), but it still poses challenges when using standard NGS workflows. In this study, we investigated genetic variants in a cohort of 450 unaffected individuals with a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, involving at least one first-degree relative, with particular emphasis on CNV detection. In our study, the detection accuracy was just 4.89%, indicating that the genetic predisposition to cancer could not be demonstrated in the majority of patients.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are associated with a significantly increased risk of breast and/or ovarian cancer. We investigated genetic variants in a cohort of 450 unaffected individuals with a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, involving at least one first-degree relative. Methods: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was used to analyze the coding regions of these two genes, with copy number variation (CNV) analysis. Results: A total of 16 unique to our cohort variants classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic were identified in 22 patients, including one novel loss-of-function variant in BRCA1 gene. Furthermore, we identified a deletion of exon 21 in the BRCA1 gene in two patients. Conclusions: These results emphasize the difficulties involved in molecular diagnostics and indicate the need for further research into new predictive models for patients with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

1. Introduction

The role of predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer caused by germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 is well documented in the literature. Pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 gene increase the risk of developing breast cancer to 55–72%, whereas variants in BRCA2 increase the risk to 45–69% [1]. In the Polish population, about 4% of breast cancer patients and 10% of ovarian cancer patients carry pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 gene [2,3,4]. According to the Szwiec et. al. paper, Polish women diagnosed with breast cancer below the age of 50 should be screened with a panel of six founder mutations in BRCA1: NM_007294.4:c.181T>G, NM_007294.4:c.4035del, NM_007294.4:c.5266dup, NM_007294.4:c.3700_3704del, NM_007294.4:c.68_69del and NM_007294.4:c.5251C>T (C61G, 4153delA, 5382insC, 3819del5, 185delAG and 5370C>T) 4) [4]. The screening used to include these variants, but now the standard testing includes targeted NGS of BRCA1/2 genes.

Another important aspect is the care of relatives of individuals with a history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, which may improve predictive accuracy in the case of hereditary variants present in the family [1]. While BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the primary genes associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, several other high-penetrance genes (e.g., TP53, PTEN, CDH1) and moderate-risk genes (e.g., ATM, CHEK2, BARD1, etc.) also contribute to cancer susceptibility [1,5,6,7].

Why is testing for variants in the BRCA1/2 genes so crucial? Individuals who carry germline pathogenic variants in these genes are sensitive to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and DNA-damaging agents, including platinum-based chemotherapies. Therefore, recognizing them is important, as this influences both therapeutic and preventive strategies. This information is used to determine eligibility for targeted therapies, which have been shown to provide this group with significant clinical benefits [8]. In addition to their therapeutic value, BRCA1/2 tests play a key role in preventing cancer and managing family risk. This allows for the implementation of personalized surveillance programs, including earlier and more frequent screening tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound and mammography. Importantly, testing is beneficial not only in families with a high risk of cancer, but also in those with a moderate or unclear family history of breast and ovarian cancer [1]. Some carriers may not meet the classic criteria [9]. They can still benefit from preventive interventions once identified. Furthermore, relatives can be tested to help identify those who are unaware of their hereditary predisposition to cancer [10]. This enables early intervention before the disease develops, before any symptoms appear [11]. In this context, genetic testing is becoming the basis for personalized medicine and cancer prevention at a population level. It also facilitates cascade testing of relatives, promoting early detection in asymptomatic carriers and enabling timely medical interventions, even in families without a strong cancer history [9].

Given the large number of variants in the BRCA1/2 genes, molecular diagnostics in breast cancer patients should be performed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) [1,5,6,7]. Despite the fact that short read sequencing offers a comprehensive range of data from sequencing, even for deep intronic variants or CNVs (copy number variants), it still poses a challenge when using standard NGS workflows [12]. Despite the widespread use of NGS in clinical practice, the prevalence and spectrum of BRCA1/2 variants, particularly CNVs, in Polish families with unaffected individuals and a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer involving at least one first-degree relative, remain limited.

This study aimed to expand current knowledge of germline BRCA1/2 variants in the Polish population by analyzing patients with a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, with particular focus on the detection of copy number variants (CNVs).

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 450 unaffected individuals (9.11% male and 90.89% female) with a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer were recruited between 2021 and 2024 at the Clinical Genetics Outpatient Clinic of the Department of Clinical Genetics at the Medical University of Lodz, Poland. In 2021, within the Polish Ministry of Health program, 12,277 individuals underwent BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing, including 1873 analysis using NGS [13]. All participants underwent pedigree analysis and medical examination. The criterion for inclusion in the study group was the presence of at least one first-degree relative with breast or ovarian cancer. Participants who had already been diagnosed with either of these cancers or who had undergone further genetic testing since the initial BRCA1/2 analysis and obtained a positive result were excluded. Thus, the analyzed cohort consisted exclusively of unaffected individuals at increased familial risk. Peripheral blood was collected from participants in the study group after they had given their informed written consent to genetic testing.

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the Maxwell® RSC Instrument (Maxwell® RSC Blood DNA Kit, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Libraries were prepared using the Devyser BRCA NGS kit (Devyser, Stockholm, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Paired-end sequencing (2 × 149 bp) was performed on a MiSeq System (Illumina). The sequencing quality was assessed using the manufacturer’s software. The mean sequencing coverage was 930x for both BRCA1 and BRCA2. Samples that did not pass quality control were sequenced to obtain the required parameters. Supplementary Figure S1 provides a detailed visualization of exon-by-exon coverage (minimal, mean and maximal) for both BRCA1 and BRCA2.

CNV confirmation was performed using MLPA (Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (SALSA® MLPA® Probemix P002 BRCA1, MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Only CNVs confirmed by MLPA were reported.

The FASTQ file was analyzed using Amplicon Suite 3.7.0 (SmartSeq), and for additional variant annotation and variant selection, we used local ANNOVAR (2019Oct24) [9]. The variants to be analyzed were prioritized according to the ClinVar prediction, the loss-of-function character, and finally the frequency in the GnomAD v4.1 reference population [14], which is below 0.01. For the analysis of CNVs from the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, dedicated software was applied. All statistical analyses were performed using Python (version 3.11) and the libraries NumPy [10] and SciPy [11]. The odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence intervals and p-values were calculated using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test based on 2 × 2 contingency tables.

3. Results

A total of 450 (n = 409 female, n = 41 male) unaffected individuals were included in the study group. CNV analysis was possible in only 270 patients due to data quality constraints. Detailed characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group.

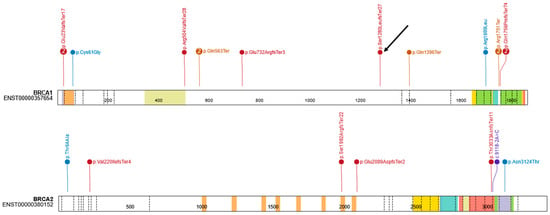

A total of 22 individuals (4.89%) were identified as carriers of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, including 16 carriers of BRCA1 variants (10 unique variants) and 6 carriers of BRCA2 variants (6 unique variants). Among the identified variants, 14 were classified as pathogenic by the ClinGen Expert Panel and 3 as pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to ClinVar (one of our records). The carrier frequency of BRCA1 was significantly higher in the study group than in gnomAD v4.1 (OR = 23.17; 95% CI: 13.99–38.40; p = 1.07 × 10−16), whereas no significant difference was observed for BRCA2 (OR = 1.88; 95% CI: 0.84–4.20; p = 0.15). Odds ratios were calculated relative to the gnomAD v4.1 European (non-Finnish) population. Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram of the obtained results. Founder mutations were observed in 7 patients, and 4 unique variants were identified. The distribution of single-nucleotide variants in the study cohort is shown in Figure 2, visualized using ProteinPaint (https://proteinpaint.stjude.org, accessed on 17 December 2025) [15].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the obtained results.

Figure 2.

Distribution of single-nucleotide variants in the study. The arrow indicates the novel variant.

Table 2 presents the selected variants with HGVS nomenclature, their classification and study group frequency, and the predicted protein changes.

Table 2.

The frequency and classification of the identified BRCA1 (NM_007294.4) and BRCA2 (NM_000059.4) variants are shown sorted by cDNA position.

One novel variant was identified in the BRCA1 gene (NM_007294.4:c.3837del; NP_009225.1:p.(Ser1280LeufsTer27), classified as likely pathogenic and submitted to ClinVar (VCV003384156.1). Additionally, twelve missense variants were identified, all of which had a minor allele frequency of less than 0.01 in gnomAD v4.1. Ten of these variants have conflicting interpretations in ClinVar. One variant had a VUS classification (NM_007294.4: c.1844C>A; p.(Ser615Tyr); VCV002811842.2), and the remaining variant without classification was NM_000059.4:c.190A>G p.(Thr64Ala). They were both evaluated according to the ACMG [16] and ClinGen BRCA1/2 VCEP classifications [17], and were classified as likely benign. According to the AlphaMissense [18], NM_007294.4:c.1844C>A was classified as likely benign (score: 0.119), while BRCA2:c.190A>G was classified as ambiguous (score: 0.38). Additionally, the lack of segregation was another aspect of the final decision.

4. Discussion

Our study yielded a positive result in 4.89% of cases, of which 20 were SNV variants and two were CNV mutations. This result is slightly lower than the results of other studies conducted in Poland, in which individuals underwent BRCA1/2 testing [2,3,4,19]. However, unlike previous studies that focused on affected patients, our cohort consisted entirely of unaffected individuals with a positive family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer.

Unlike BRCA1 (p = 1.07 × 10−16), no significant difference in carrier frequency was observed for BRCA2 (p = 0.15) when compared with gnomAD v4.1. This finding is consistent with a study by Cybulski et al., which found that variants in BRCA2 are relatively rare in familial breast cancer in Poland [20]. Consequently, the absence of statistical significance of variants for the BRCA2 gene in our dataset should be interpreted with caution, particularly in the context of population structure, penetrance differences and cohort selection. Furthermore, the insignificant p-value for BRCA2 can partly be explained by the small number of observed carriers, which reduces the accuracy of the odds ratio estimate. This limitation is inherent in analyses of rare variants, emphasizing the importance of larger sample sizes for reliably detecting moderate enrichment signals.

Furthermore, the NM_007294.4:c.5266dup variant, which is most strongly associated with breast and/or ovarian cancer in Poland, was not the most frequently observed variant in our cohort [2,3,4,19]. Nevertheless, several studies have discussed pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes associated with reduced penetrance [21,22,23]. Finally, the inclusion of unaffected individuals in our cohort may explain the observed frequency deviation, as many of the most severely affected families were likely diagnosed earlier in other clinical centers. Thus, despite the relatively small size of the study group, our study provides additional data on a new loss-of-function variant in the BRCA1 gene (NM_007294.4:c.3837del; p.(Ser1280Leufs*27); ACMG: PVS1, PM2) and other described variants. The NM_007294.4:c.3837del variant is located in exon 10 of the BRCA1 gene. This variant was absent from the gnomAD v4.1 database. The serine cluster domain spans amino acids 1280–1524, and the variant is in position 1800 aa. Mutation of these serine residues has clinical implications and may affect the localization of BRCA1 to sites of DNA damage and the function of the DNA damage response [24].

It is worth noting that the process of detecting CNVs can be a difficult undertaking [12,25,26]. Identifying even a single CNV can have a significant impact on the further care of the patient and their family. Therefore, it is extremely important to accurately determine the exact diagnosis. Several technical challenges were encountered during CNV assessment using the Devyser BRCA NGS kit (NGS amplicon-based) in our study. Although the DNA quality and sequencing metrics (including coverage depth and Q30) were within acceptable ranges, a subset of the samples generated could not be analyzed for CNVs. We attempted to analyze DNA isolate purity parameters based on the A260/A280 spectrophotometric parameters, but this did not show a correlation with the success rate of CNV analysis from NGS data. Neither DNA concentration alone nor different reagent batches from different manufacturers had a significant impact on the success rate of CNV analysis. Consequently, it was not possible to evaluate certain samples for CNVs with confidence, which highlights the need for MLPA validation for negative samples. NGS kits based on probe enrichment may yield more reliable and reproducible CNV analysis results than those based on amplicon technology.

Given the growing number of available genetic test results, it is crucial to collect data on rare genetic variants across multiple families. These efforts could potentially lead to more reliable classification of variants, as demonstrated in the article by Caputo et al. [27]. In this context, the systematic collection of data from cohorts of unaffected individuals with a positive family history, as in the present study, can contribute to the future development of reference datasets for interpreting BRCA1/2 variants in the Polish population. However, several methodological limitations should be taken into consideration. First of all, this study did not analyze deep intronic sequences, meaning that pathogenic variants in these locations of the genome could not be detected. Furthermore, not all patients had CNVs analyzed. Secondly, the analysis only considered two genes and did not involve a broader genetic assessment (e.g., PALB2, CHEK2, ATM, RAD51C and RAD51D). This reflects the clinical and financial constraints of the testing strategy used during the study period, when BRCA1/2 testing was the only approach to screening that was reimbursed in Poland.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study expands the spectrum of known genetic variants with a newly identified loss-of-function variant of BRCA1, which highlights the importance of including CNV analysis in routine BRCA1/2 screening. Identifying this variant shows that clinically relevant changes can be missed in families with no obvious history of the condition. Furthermore, failing to incorporate reliable CNV analysis into standard workflows in amplicon arrays can result in false-negative results. In such cases, diagnostics should be extended to include additional tests, such as MLPA.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol33010010/s1. Figure S1: Distribution of coverage across exons of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z.; Methodology, I.D.; Software, S.S. and T.P.; Formal analysis, T.P. and S.S.; Investigation, I.D., S.S., H.M., M.S., K.P., O.W. and K.Ż.; Data curation, H.M., M.S., K.P., O.W. and K.Ż.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and T.P.; Supervision, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the University Bioethics Committee at the Medical University in Łódź, Poland (approval number: RNN/07/23/KE; approval date: 10 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data were generated from routine patient diagnostics at the Central Teaching Hospital of the Medical University of Lodz. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Petrucelli, N.; Daly, M.B.; Pal, T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gronwald, J.; Cybulski, C.; Huzarski, T.; Jakubowska, A.; Debniak, T.; Lener, M.; Narod, S.A.; Lubinski, J. Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer in Poland: 1998–2022. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2023, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukomska, A.; Menkiszak, J.; Gronwald, J.; Tomiczek-Szwiec, J.; Szwiec, M.; Jasiówka, M.; Blecharz, P.; Kluz, T.; Stawicka-Niełacna, M.; Mądry, R.; et al. Recurrent Mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51C, PALB2 and CHEK2 in Polish Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwiec, M.; Jakubowska, A.; Górski, B.; Huzarski, T.; Tomiczek-Szwiec, J.; Gronwald, J.; Dębniak, T.; Byrski, T.; Kluźniak, W.; Wokołorczyk, D.; et al. Recurrent Mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Poland: An Update. Clin. Genet. 2015, 87, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.; Astiazaran-Symonds, E.; Amendola, L.M.; Balmaña, J.; Foulkes, W.D.; James, P.; Klugman, S.; Ngeow, J.; Schmutzler, R.; Voian, N.; et al. Management of Individuals with Germline Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Variants in CHEK2: A Clinical Practice Resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, A.S.; Robson, M.E.; Mellemkjær, L.; Tischkowitz, M.; John, E.M.; Lynch, C.F.; Brooks, J.D.; Boice, J.D.; Knight, J.A.; Teraoka, S.N.; et al. Radiation Treatment, ATM, BRCA1/2, and CHEK2 *1100delC Pathogenic Variants and Risk of Contralateral Breast Cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Boddicker, N.J.; Na, J.; Polley, E.C.; Hu, C.; Hart, S.N.; Gnanaolivu, R.D.; Larson, N.; Holtegaard, S.; Huang, H.; et al. Contralateral Breast Cancer Risk Among Carriers of Germline Pathogenic Variants in ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and PALB2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, B.; Couch, F.J.; Abraham, J.; Tung, N.; Fasching, P.A. BRCA-Mutated Breast Cancer: The Unmet Need, Challenges and Therapeutic Benefits of Genetic Testing. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1400–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mighton, C.; Shickh, S.; Aguda, V.; Krishnapillai, S.; Adi-Wauran, E.; Bombard, Y. From the Patient to the Population: Use of Genomics for Population Screening. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 893832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razeq, H. Expanding the Search for Germline Pathogenic Variants for Breast Cancer. How Far Should We Go and How High Should We Jump? The Missed Opportunity! Oncol. Rev. 2021, 15, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.K.; Ahsan, M.D.; Bergeron, H.; Lin, J.; Li, X.; Fowlkes, R.K.; Narayan, P.; Nitecki, R.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Moss, H.A.; et al. Cascade Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes: Should We Move Toward Direct Relative Contact? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 4129–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinodoz, M.; Kaminska, K.; Cancellieri, F.; Han, J.H.; Peter, V.G.; Celik, E.; Janeschitz-Kriegl, L.; Schärer, N.; Hauenstein, D.; György, B.; et al. Detection of Elusive DNA Copy-Number Variations in Hereditary Disease and Cancer through the Use of Noncoding and off-Target Sequencing Reads. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SANITAS. Badania Genetyczne w Polsce. Stan Obecny, Potrzeby, Problemy, Rozwiązania; SANITAS: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Francioli, L.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Collins, R.L.; Kanai, M.; Wang, Q.; Alföldi, J.; Watts, N.A.; Vittal, C.; Gauthier, L.D.; et al. A Genomic Mutational Constraint Map Using Variation in 76,156 Human Genomes. Nature 2024, 625, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Edmonson, M.N.; Wilkinson, M.R.; Patel, A.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Rusch, M.C.; Parker, M.; et al. Exploring Genomic Alteration in Pediatric Cancer Using ProteinPaint. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.T.; De La Hoya, M.; Richardson, M.E.; Tudini, E.; Anderson, M.; Berkofsky-Fessler, W.; Caputo, S.M.; Chan, R.C.; Cline, M.S.; Feng, B.-J.; et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Gene-Specific ACMG/AMP Variant Classification from the ClinGen ENIGMA BRCA1 and BRCA2 Variant Curation Expert Panel. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 2044–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Novati, G.; Pan, J.; Bycroft, C.; Žemgulytė, A.; Applebaum, T.; Pritzel, A.; Wong, L.H.; Zielinski, M.; Sargeant, T.; et al. Accurate Proteome-Wide Missense Variant Effect Prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 2023, 381, eadg7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Dumont, T.; Karpinski, P.; Sasiadek, M.M.; Akopyan, H.; Steen, J.A.; Theys, D.; Hammet, F.; Tsimiklis, H.; Park, D.J.; Pope, B.J.; et al. Genetic Testing in Poland and Ukraine: Should Comprehensive Germline Testing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Be Recommended for Women with Breast and Ovarian Cancer? Genet. Res. 2020, 102, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, C.; Kluźniak, W.; Huzarski, T.; Wokołorczyk, D.; Kashyap, A.; Rusak, B.; Stempa, K.; Gronwald, J.; Szymiczek, A.; Bagherzadeh, M.; et al. The Spectrum of Mutations Predisposing to Familial Breast Cancer in Poland. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 3311–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Engel, C.; De La Hoya, M.; Peterlongo, P.; Yannoukakos, D.; Livraghi, L.; Radice, P.; Thomassen, M.; Hansen, T.V.O.; Gerdes, A.-M.; et al. Risks of Breast and Ovarian Cancer for Women Harboring Pathogenic Missense Variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Compared with Those Harboring Protein Truncating Variants. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, T.; Mundt, E.; Richardson, M.E.; Chao, E.; Pesaran, T.; Slavin, T.P.; Couch, F.J.; Monteiro, A.N.A. Reduced Penetrance BRCA1 and BRCA2 Pathogenic Variants in Clinical Germline Genetic Testing. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spurdle, A.B.; Whiley, P.J.; Thompson, B.; Feng, B.; Healey, S.; Brown, M.A.; Pettigrew, C.; kConFab; Van Asperen, C.J.; Ausems, M.G.; et al. BRCA1 R1699Q Variant Displaying Ambiguous Functional Abrogation Confers Intermediate Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.L.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Snyder, R.R.; Hankins, G.D.V.; Boehning, D. Structure-Function of The Tumor Suppressor BRCA1. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 1, e201204005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derouault, P.; Chauzeix, J.; Rizzo, D.; Miressi, F.; Magdelaine, C.; Bourthoumieu, S.; Durand, K.; Dzugan, H.; Feuillard, J.; Sturtz, F.; et al. CovCopCan: An Efficient Tool to Detect Copy Number Variation from Amplicon Sequencing Data in Inherited Diseases and Cancer. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.A.; Loeys, B.; Van De Beek, G.; Peeters, N.; Wuyts, W.; Van Laer, L.; Vandeweyer, G.; Alaerts, M. varAmpliCNV: Analyzing Variance of Amplicons to Detect CNVs in Targeted NGS Data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, S.M.; Golmard, L.; Léone, M.; Damiola, F.; Guillaud-Bataille, M.; Revillion, F.; Rouleau, E.; Derive, N.; Buisson, A.; Basset, N.; et al. Classification of 101 BRCA1 and BRCA2 Variants of Uncertain Significance by Cosegregation Study: A Powerful Approach. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1907–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.