Introduction

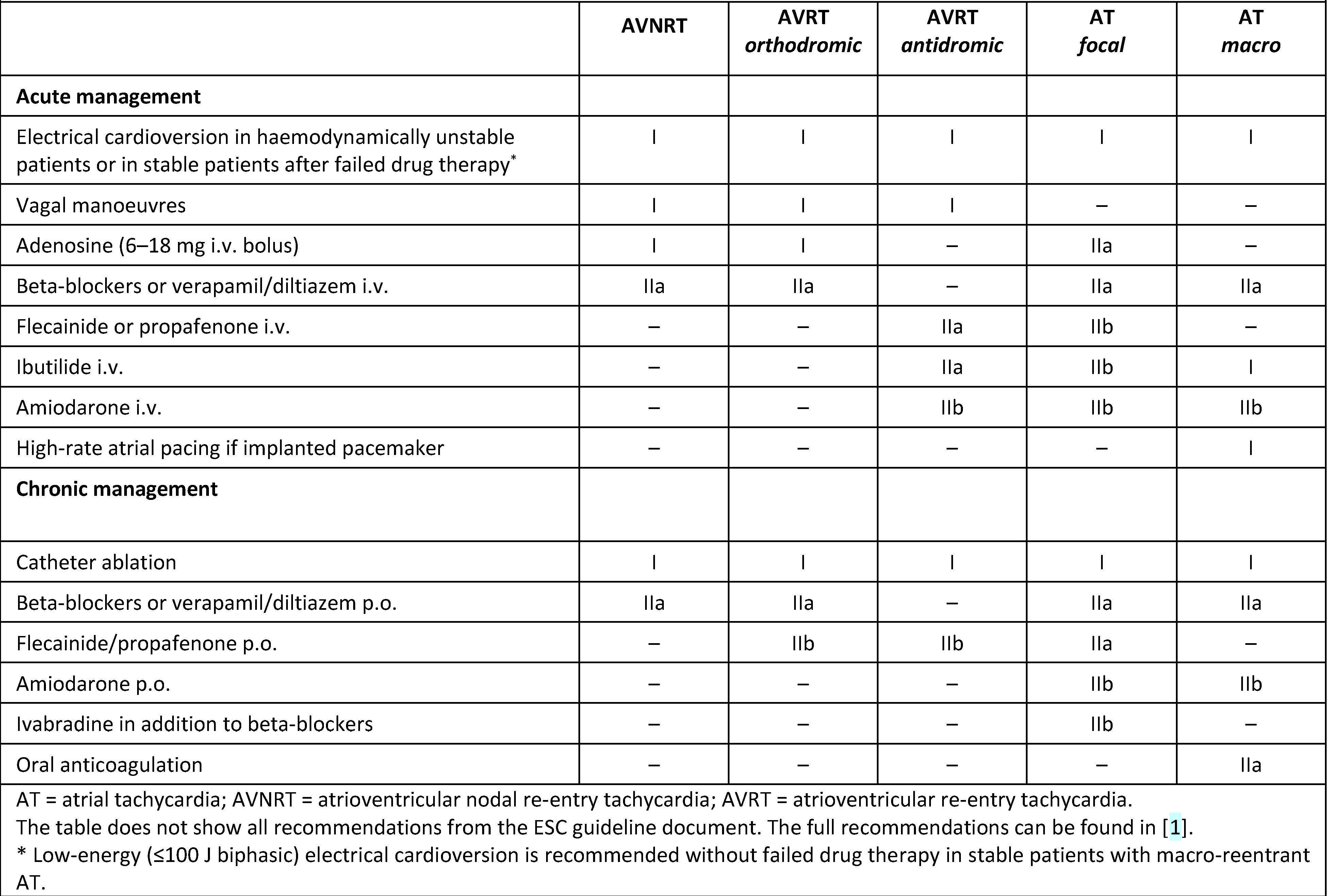

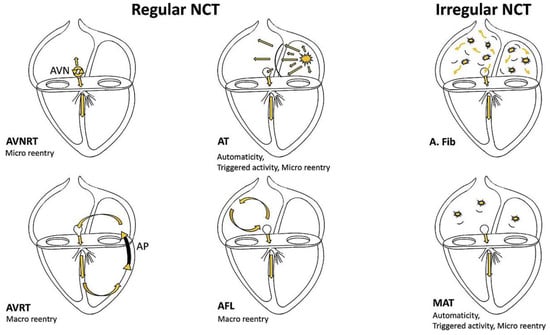

Supraventricular tachycardias (SVTs) are common in the general population and usually symptomatic. Thus, cardiologists and emergency care physicians need to be informed about the correct diagnosis and management of these patients. Here we give an overview based on the recently published 2019 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on SVT [1]. We focus on the updated recommendations for the acute management of SVT in the absence of an established diagnosis and the diagnosis and management of three common SVTs: atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT), and atrial tachycardia (AT). An overview of the acute and chronic management of AVNRT, AVRT and focal AT is provided in Table 1. Examples of 12-lead ECG tracings are shown in Figure 1 and schematic tachycardia presentations in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Acute and chronic management of supraventricular tachycardia. Adapted from [1] with permission.

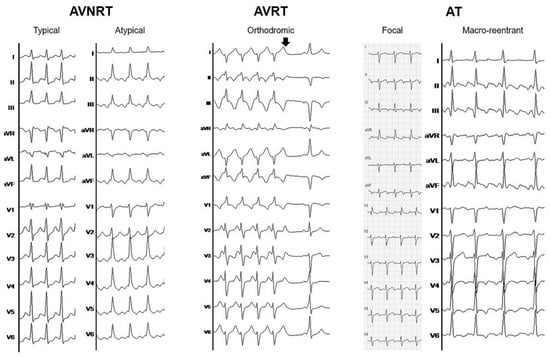

Figure 1.

Electrocardiographic examples of different supraventricular tachycardias. From left to right: Typical (short RP) and atypical (long RP) atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT). Orthodromic atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT) with right bundle branch aberrancy during tachycardia and spontaneous tachycardia termination (arrow) with evidence of preexcitation during sinus rhythm. Focal atrial tachycardia (AT) originating from posterolateral in the right atrium (Note that the limb and chest leads were not recorded simultaneously). Macro-reentrant atrial tachycardia (common flutter) with 2:1 and 3:1 conduction.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of different supraventricular tachycardia circuits. From Shah et al with permission [2]. AVN = atrioventricular node; AP = accessory pathway; AVNRT = atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; AVRT = atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia; AT = atrial tachycardia; AFL = atrial flutter; A. fib = atrial fibrillation; MAT = multifocal atrial tachycardia; NCT = narrow complex tachycardia.

Acute management without established diagnosis

Initial treatment of patients with SVT should be guided by haemodynamic stability and consists of electrical cardioversion if the patient is unstable (recommendation Class I). In haemodynamically stable patients, a 12-lead ECG during tachycardia should be recorded and the first treatment should always consist of vagal manoeuvres (Class I). The preferred one is a modified Valsalva manoeuvre, which was shown to more than double the rate of successful conversion from 17% to 43% [3]. In the modified manoeuvre, patients have to be in a sitting, semi-recumbent position and perform a forced expiration with resistance, for example into a 10 ml syringe. Immediately at the end of this strain, patients are laid flat on their back with their legs raised by medical staff to 45° for 15 seconds [3]. Other vagal manoeuvres include unilateral carotid sinus massage for 5 seconds after excluding carotid bruits and a history of a prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack.

The subsequent treatment recommendations depend on the QRS width. In narrow complex tachycardia, adenosine 6–18 mg i.v. with a saline flush should be administered (Class I) after excluding a history of asthma or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adenosine may terminate the tachycardia in >90% of cases and may give diagnostic clues by unmasking atrial arrhythmias not dependent on the atrioventricular (AV) node. Second line drugs are beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (Class IIa) and, in the case of failed drug therapy, a synchronised cardioversion (Class I). In wide complex tachycardia, adenosine should be administered only if there is no pre-excitation on a resting ECG (IIa). Second line treatment options include procainamide i.v. (Class IIa) and amiodarone i.v. (Class IIb), whereas verapamil is contraindicated (Class III). Generally, there should be a low threshold for electrical cardioversion in wide-complex tachycardia (Class I) and it should be treated as a ventricular tachycardia if the tachycardia mechanism is not fully understood.

Irregularly irregular SVT is usually atrial fibrillation and should be treated accordingly. Management of wide complex, irregular tachycardia is described in the corresponding section of AVRT.

Atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT)

The re-entry circuit of AVNRT consists of the “fast” and “slow” pathways within the AV node, with three possible mechanisms: the most common, typical slow-fast and the less common, atypical fast-slow or slow-slow circuits. The first clinical manifestation of AVNRT has a first peak in the second and third decade of life and a second in the fourth or fifth decade [4].

Diagnosis

The first step in the noninvasive diagnosis of AVNRT, besides the clinical history, is a 12-lead ECG during tachycardia (Figure 1). In the absence of aberrant conduction or a pre-existing ventricular conduction delay, AVNRT is a narrow complex tachycardia. Although rare, AV dissociation may occur as the circuit is within the AVN and neither the atria nor the ventricles are necessary to maintain the tachycardia. In typical AVNRT, the retrograde, atrial activation is via the anteroseptal “fast” pathway, leading to narrow, superiorly directed P waves within or directly after the QRS complex (short RP interval). P waves during tachycardia may present as pseudo R deflections in V1 and aVR, pseudo S waves in the inferior leads or a notch in aVL – underscoring the role of comparing the tachycardia ECG with a sinus rhythm ECG for diagnosis [5]. If the AVNRT onset is captured, a sudden prolongation of the PR interval, corresponding to the anterograde block in the “fast” pathway and conduction via the “slow” pathway, usually precedes the first tachycardia beat. In atypical AVNRT, the P waves are usually clearly visible with a long RP interval and a morphology similar to typical AVNRT.

Acute management

The acute management of AVNRT is guided by haemodynamic stability. In the case of haemodynamic instability, patients should undergo a synchronised cardioversion (Class I). If the patient is haemodynamically stable, vagal manoeuvres as described above are recommended first-line treatment [3]. If vagal manoeuvres fail, adenosine (6–18 mg i.v. bolus) should be used as second line, and a synchronised cardioversion as third line (all Class I). There is only a minor role for beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in the acute management of AVNRT, with contraindications in decompensated heart failure (Class IIa).

Chronic management

The only Class I recommendation for the chronic management of symptomatic and recurrent AVNRT is for catheter ablation. All patients usually undergo a full electrophysiological study with confirmation of the diagnosis before “slow” pathway modification. Catheter ablation has a success rate of ~97% with a recurrence rate of 1.3–4% and a low risk (<1%) of AV block, with even lower risks in experienced centres and a more conservative ablation approach targeting the inferior extensions and sparing the mid-septum [6,7,8]. Higher patient age should not be a contraindication for catheter ablation [9]. It is also indicated in cases of inappropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) shocks due to AVNRT [10]. Chronic drug therapy (Class IIa) for AVNRT should generally be avoided in our view owing to side-effects of long-term drug treatment and the excellent success rates with minimal risk of catheter ablation.

Atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT)

The tachycardia circuit in AVRT has two limbs, of which at least one is an antero- or retrogradely conducting accessory pathway. Usually the second limb is via the AVN and His-Purkinje system, but rarely it can be a second accessory pathway. Typical atrioventricular accessory pathways have electrophysiological properties different from the AV node. However, there is variety of atypical forms, including atrio-fascicular, nodo-fascicular, nodo-ventricular and fasciculo-ventricular accessory pathways, with different conduction properties.

Diagnosis

In the majority of cases (>90%), AVRT is orthodromic with anterograde conduction via the AV node-His Purkinje system leading to a narrow complex tachycardia (except in the presence of functional or pre-existing bundle branch block) with a constant RP interval (Figure 1). In antidromic AVRT the QRS complex is usually fully pre-excited with an often difficult to delineate, retrograde P wave [11]. As AVRT is a serial activation of the atrium and ventricle, both are necessary to maintain the tachycardia and a conduction block to one or the other breaks the tachycardia. Exceptions include a nodo-fascicular/-ventricular accessory pathway, which can sustain tachycardia without the atrium and which should, therefore, strictly speaking not be called AVRT.

During sinus rhythm, pre-excitation is present in “manifest” accessory pathways, may be seen in “latent” accessory pathways with minimal pre-excitation due to anatomical location or conduction properties and is absent in “concealed” accessory pathways that exclusively conduct retrogradely. In the presence of pre-excitation, the accessory pathway can be localised using different algorithms, which are generally less reliable in children [12,13].

Acute management

Acute management includes synchronised cardioversion in the case of haemodynamic instability and modified vagal manoeuvres, adenosine and synchronised cardioversion in a step-wise manner in the case of haemodynamic stability (all Class I). Adenosine should be used in orthodromic AVRT only with caution and the possibility for electrical cardioversion in place, as atrial fibrillation may be induced, which can rapidly conduct over the accessory pathway to the ventricle and may degenerate into ventricular fibrillation [14,15]. In orthodromic AVRT, drugs targeting the AV node (beta-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers) may also be used (Class IIa). Accordingly, drugs acting mainly on the accessory pathway (ibutilide, procainamide, propafenone or flecainide) may be used in antidromic AVRT (Class IIa). Although amiodarone may be used in the acute management of refractory cases (Class IIb), we generally discourage its use in this setting and would rather proceed directly with synchronised cardioversion.

In the case of pre-excited atrial fibrillation synchronised electrical cardioversion should be used more deliberately in haemodynamically stable patients with failed drug therapy (Class I), which includes ibutilide or procainamide (Class IIa) and flecainide or propafenone (IIb). Amiodarone is contraindicated in pre-excited atrial fibrillation (Class III). As both ibutilide and procainamide are usually not readily available in Switzerland, we recommend to directly use synchronised cardioversion for pre-excited atrial fibrillation.

Chronic management

Similarly to AVNRT, the only Class I recommendation for the chronic treatment of symptomatic AVRT exists for catheter ablation. It has a very high success rate of >98% overall with variations depending on the pathway location, a low recurrence rate and an excellent safety profile [16]. Besides symptom control, catheter ablation also dramatically reduces the risk for life-threatening arrhythmia [16]. Beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers should be considered in symptomatic patients without pre-excitation during sinus rhythm if ablation is not desired or feasible (Class IIa); propafenone or flecainide might be considered in patients without ischaemic or structural heart disease (Class IIb). In the case of pre-excited atrial fibrillation that manifests as an irregular wide-complex tachycardia, drugs that only slow down the conduction over the AV node, such as beta-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, digoxin and amiodarone, are potentially harmful and not recommended for chronic therapy (Class III).

Asymptomatic patients with documented pre-excitation have a risk of 20% to develop an accessory pathway-related arrhythmia during their lifetime and should undergo risk stratification to decide if catheter ablation is indicated to reduce the risk of malignant arrhythmias. Although abrupt loss of pre-excitation during exercise testing, following administration of procainamide, propafenone or disopyramide, or spontaneously is considered a low-risk feature, it does not exclude a malignant catheter ablation with short refractory periods [17]. Thus electrophysiological testing has a Class I indication for risk stratification in patients with high-risk occupations or hobbies (e.g., pilot, professional driver) and in patients without noninvasive low-risk features, and a Class IIa indication in all other patients. Noninvasive evaluation only should be discouraged (Class IIb). After invasive risk stratification, catheter ablation is recommended for all patients with high-risk features (Class I). These include an accessory pathway effective refractory period (or shortest RR interval during atrial fibrillation) ≤250ms, multiple accessory pathways or inducible AVRT. Catheter ablation may also be considered in patients with low-risk accessory pathway features in experienced centres according to patient preferences (Class IIb).

Focal atrial tachycardia

Focal AT presents as an organised atrial rhythm due to automaticity, triggered activity or micro-reentry, propagating from a defined anatomical location in a centrifugal pattern. Though focal AT may theoretically originate from anywhere in the atria, the majority originates from the crista terminalis, tricuspid annulus and the pulmonary veins [18]. It is the rarest of the SVTs described in this article.

Diagnosis

A 12-lead ECG during tachycardia usually shows monomorphic P waves with relatively stable cycle lengths and isoelectric intervals between (Figure 1). The isoelectric interval is obligatory for focal AT, but it does not rule out macro-reentrant AT, particularly in patients with previous ablation. P waves may be hidden in the QRS or T wave, depending on the atrial rate and AV conduction, and their morphology allow noninvasive identification of the site of origin [18]. Focal AT may be sustained, but dynamic forms with repeated interruptions and reinitiations are frequent.

Acute management

In the rare event of haemodynamic instability, synchronised cardioversion is recommended (Class I), however AT due to automaticity may immediately reinitiate. Evidence for acute drug therapy is limited. Adenosine (6–18 mg i.v.) should be considered to slow the ventricular rate in order to better identify the P waves and to terminate the AT in the case of triggered activity (Class IIa). In a second step, beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers should be considered (Class IIa). Only as a third step, anti-arrhythmic drugs may be considered (Class IIb).

Chronic management

The preferred treatment for recurrent or incessant AT, or AT with tachycardiomyopathy is catheter ablation (Class I), with an average success rate of 85% and a low complication rate of ~1%, both depending on the site of origin. Similar to acute management, there is little evidence for chronic drug therapy. Beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers may be effective (Class IIa) [19]. Class Ic anti-arrhythmics (Class IIa) and ivabradine may be considered second line (Class IIb). The use of amiodarone should be discouraged because of side effects with long-term use (Class IIb).

In the rare cases of multifocal AT, treatment should be primarily targeted at the underlying condition (Class I) with low evidence for antiarrhythmic drugs and only a supportive role of beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers (Class IIa).

Macro-reentrant atrial tachycardia

We usually distinguish between common, cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI)-dependent and atypical, non-CTI dependent macro-reentrant AT. The classical ECG appearance of macro-reentrant AT shows a continuous, regular electrical activity. However, a significant part of macro-reentrant ATs present with discrete P waves, as part of the tachycardia circuit might be in a protected area with local slow conduction.

Diagnosis

In common, CTI-dependent atrial flutter, the right atrial activation is counter-clockwise downward the free wall, through the CTI, ascends in the right septum, activates the left atrium passively and passes anterior or posterior to the superior vena cava again to the free wall. This activation produces negative saw-tooth waves in the inferior leads and positive waves in V1 (Figure 1). Reverse atrial flutter uses the same circuit clockwise leading to broad, positive waves in the inferior leads and usually negative waves in V1.

The ECG appearance of atypical, non-CTI dependent AT is highly variable and depends on the tachycardia circuit. The circuit may involve prior surgical incisions, prior ablation lesions, anatomical structures (e.g., the vein of Marshall) and progressive atrial fibrosis.

Acute management

Similar to the acute management of other SVTs, synchronised cardioversion is the first step in haemodynamically unstable patients (Class I). But also in haemodynamically stable patients, low-energy electrical cardioversion may be used as a first treatment option (Class I). Alternative Class I-recommended first-line treatments include ibutilide or dofetilide and high-rate atrial pacing in the presence of a cardiac pacemaker. Beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers i.v. should be used for rate control if electrical or pharmacological conversion is not desired (Class IIa). In selected patients, amiodarone may be used if all prior options fail (IIb), whereas propafenone and flecainide are contraindicated (Class III). Alternatively, invasive high-rate atrial pacing may also be considered for AT termination (Class IIb). However, we think in these patients catheter ablation should be considered as soon as possible, especially for atypical AT where the tachycardia circuit needs be delineated while the arrhythmia is ongoing.

If the duration of atrial flutter is unknown, one should bear in mind that oral anticoagulation may need to be instituted according to the CHA2DS2-VaSC score and that a transoesophageal echocardiogram may be necessary to rule out left atrial appendage thrombi before cardioversion in haemodynamically stable patients.

Chronic management

The preferred treatment of symptomatic, recurrent macro-reentrant AT is catheter ablation, which has a high success rate and an excellent safety profile (Class I). In addition, catheter ablation should already be considered after the first episode of symptomatic, common atrial flutter (Class IIa) and is recommended in patients with persistent AT or depressed left ventricular systolic function (Class I). Drug treatment plays a minor role in the chronic management of macro-reentrant AT and should only be considered if catheter ablation failed or is not desired (Class IIa for rate control, Class IIb for amiodarone). If all prior options fail and the patient is still symptomatic, a “pace and ablate” strategy with pacemaker implantation and subsequent AV node ablation should be considered (Class IIa).

Although the thromboembolic risk in macro-reentrant AT is lower than in atrial fibrillation, it is still significantly high [20]. Both arrhythmias frequently coexist and atrial fibrillation can be found in a large proportion of CTI-dependent flutter patients after CTI ablation [21]. Though large randomised trials are lacking, we decide on anticoagulation in macro-reentrant AT patients based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score independently of performed ablation, similar to atrial fibrillation patients (Class IIa).

Conclusion

The first step in the acute management of SVT after a 12-lead ECG documentation should be a synchronised electrical cardioversion in haemodynamically unstable patients and vagal manoeuvres in stable patients. Catheter ablation is the recommended first-line treatment in symptomatic, recurrent AVNRT, AVRT and AT with a high success rate and an excellent safety profile.

Key points

- A 12-lead ECG documentation of the tachycardia should be sought.

- Vagal manoeuvres and intravenous adenosine should be the first-line treatment in the acute management of supraventricular tachycardia.

- Catheter ablation should be offered to all patients as a first-line treatment in the chronic management of all re-entrant and most focal supraventricular arrhythmias.

- Invasive risk stratification with an electrophysiological study should be offered to asymptomatic patients with pre-excitation, who have high-risk occupations or are competitive athletes.

- Noninvasive risk stratification for asymptomatic pre-excitation cannot rule out a potentially dangerous accessory pathway.

- Amiodarone should not be used in pre-excited atrial fibrillation.

- Anticoagulation should be considered in macro-reentrant atrial tachycardia similar to atrial fibrillation.

Conflicts of Interest

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Brugada, J.; Katritsis, D.G.; Arbelo, E.; Arribas, F.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; ESC Scientific Document Group; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. The Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 655–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.L.; Badhwar, N. Approach to narrow complex tachycardia: non-invasive guide to interpretation and management. Heart. 2020, 106, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelboam A, Reuben A, Mann C, Gagg J, Ewings P, Barton A, et al. REVERT trial collaborators. Postural modification to the standard Valsalva manoeuvre for emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardias (REVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015, 386, 1747–1753. [CrossRef]

- Pentinga, M.L.; Meeder, J.G.; Crijns, H.J.; de Muinck, E.D.; Wiesfeld, A.C.; Lie, K.I. Late onset atrioventricular nodal tachycardia. Int J Cardiol. 1993, 38, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritsis, D.G.; Josephson, M.E. Differential diagnosis of regular, narrow-QRS tachycardias. Heart Rhythm. 2015, 12, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritsis, D.G.; Zografos, T.; Katritsis, G.D.; Giazitzoglou, E.; Vachliotis, V.; Paxinos, G.; et al. Catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drug therapy in patients with symptomatic atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia: a randomized, controlled trial. Europace. 2017, 19, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.; Reynolds, M.R.; Calkins, H.; Sondhi, M.; Xu, Y.; Martin, A.; et al. Meta-analysis of ablation of atrial flutter and supraventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol. 2009, 104, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritsis, D.G.; Zografos, T.; Siontis, K.C.; Giannopoulos, G.; Muthalaly, R.G.; Liu, Q.; et al. Endpoints for Successful Slow Pathway Catheter Ablation in Typical and Atypical Atrioventricular Nodal Re-Entrant Tachycardia: A Contemporary, Multicenter Study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019, 5, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostock, T.; Risius, T.; Ventura, R.; Klemm, H.U.; Weiss, C.; Keitel, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005, 16, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, A.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Boles, U.; Baranchuk, A. Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia in Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators: Diagnosis and Troubleshooting. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015, 26, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brembilla-Perrot, B.; Pauriah, M.; Sellal, J.-M.; Zinzius, P.Y.; Schwartz, J.; de Chillou, C.; et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of spontaneous and inducible antidromic tachycardia. Europace. 2013, 15, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pambrun, T.; El Bouazzaoui, R.; Combes, N.; Combes, S.; Sousa, P.; Le Bloa, M.; et al. Maximal Pre-Excitation Based Algorithm for Localization of Manifest Accessory Pathways in Adults. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018, 4, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, C.; Vogel, M.; Lord, S.; Abrams, D.; Bourke, J.; Rees, P.; et al. Accuracy of algorithms to predict accessory pathway location in children with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Heart. 2012, 98, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, A.J.; Murray, S.; Thambyrajah, J. Pre-excited atrial fibrillation triggered by intravenous adenosine: a commonly used drug with potentially life-threatening adverse effects. Emerg Med J. 2008, 25, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, C.J.; Griffith, M.J.; O’Nunain, S.; Ward, D.E.; Camm, A.J. Effects of intravenous adenosine on antegrade refractoriness of accessory atrioventricular connections. Circulation. 1991, 84, 1962–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappone, C.; Vicedomini, G.; Manguso, F.; Saviano, M.; Baldi, M.; Pappone, A.; et al. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in the era of catheter ablation: insights from a registry study of 2169 patients. Circulation. 2014, 130, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, D.Y.; Sherwin, E.D.; Alexander, M.E.; Cecchin, F.; Abrams, D.J.; Walsh, E.P.; et al. The electrophysiological characteristics of accessory pathways in pediatric patients with intermittent preexcitation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013, 36, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistler, P.M.; Roberts-Thomson, K.C.; Haqqani, H.M.; Fynn, S.P.; Singarayar, S.; Vohra, J.K.; et al. P-wave morphology in focal atrial tachycardia: development of an algorithm to predict the anatomic site of origin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 48, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.V.; Sanchez, G.R.; Sacks, E.J.; Casta, A.; Dunn, J.M.; Donner, R.M. Ectopic automatic atrial tachycardia in children: clinical characteristics, management and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988, 11, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadmann, H.; Nielsen, P.B.; Hjortshøj, S.P.; Riahi, S.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Lip, G.Y.H.; et al. Atrial flutter and thromboembolic risk: a systematic review. Heart. 2015, 101, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celikyurt, U.; Knecht, S.; Kuehne, M.; Reichlin, T.; Muehl, A.; Spies, F.; et al. Incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cavotricuspid isthmus ablation for atrial flutter. Europace. 2017, 19, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2021 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.