Highlights

Public health relevance—How does this work relate to a public health issue?

- Racial and ethnic inequities in severe COVID-19 outcomes persisted among Medicaid beneficiaries despite uniform insurance coverage.

- Disparities were most evident at hospital admission, underscoring upstream social and structural determinants that shape exposure risk and severity at presentation.

Public health significance—Why is this work of significance to public health?

- By examining the hospitalization continuum (COVID-19 diagnosis at admission, excess in-hospital mortality, and mortality within COVID-19 hospitalizations), this study clarifies where inequities are most pronounced.

- Findings show that insurance coverage alone is insufficient to prevent inequities in severe infectious disease-related hospitalization burden and hospital outcomes.

Public health implications—What are the key implications or messages for practitioners, policy makers and/or researchers in public health?

- Equity-focused strategies should prioritize prevention, early diagnosis, and timely outpatient evaluation and treatment access to reduce avoidable hospitalizations in Medicaid and similarly vulnerable populations.

- Continuum-based evaluation of inequities can guide more targeted preparedness and health system responses for the COVID-19 endemic phase and future public health emergencies.

Abstract

COVID-19 exposed longstanding racial and ethnic inequities among underserved populations. This retrospective cohort study examined inequities across stages of the hospitalization continuum—from COVID-19 diagnosis at admission to in-hospital mortality, including mortality patterns among COVID-19 hospitalizations—among Medicaid beneficiaries in Kentucky during 2020–2021. Statewide hospitalizations were analyzed using multivariable regression models, with propensity score matching (PSM) used as a confirmatory approach. Non-Hispanic Black patients were more likely than non-Hispanic White patients to be hospitalized with COVID-19 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.41; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.26–1.59). Across the full cohort, COVID-19 hospitalizations were associated with substantially higher in-hospital mortality compared with non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 2.38; 95% CI = 2.09–2.70). Additionally, hospitalizations among non-Hispanic Black patients had a modestly lower hazard of in-hospital mortality compared with non-Hispanic White patients (aHR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.70–0.94). However, in analyses restricted to COVID-19 hospitalizations, adjusted estimates showed no Black–White differences in in-hospital mortality, with consistent findings from PSM analyses. These results indicate that racial inequities were more pronounced at hospital admission than during inpatient care, underscoring the importance of prevention, early diagnosis, and timely outpatient care as COVID-19 enters an endemic phase.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed and amplified longstanding racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States. In 2021, COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death nationwide, with an unprecedented burden of mortality concentrated in communities of color [1]. Across the pandemic period from 2020 to 2021, racial and ethnic minority populations—including Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN)—experienced disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death compared with White populations [2]. For example, early surveillance documented COVID-19 hospitalization rates that were approximately five times higher among Black and Hispanic persons than among White persons [3]. COVID-19 mortality rates were likewise substantially higher among Black, Hispanic, and AI/AN populations, who accounted for a disproportionately large share of deaths relative to their population size. These disparities widened with increasing age and contributed to disproportionate reductions in life expectancy among minority communities [1,3]. Taken together, these patterns reflect the unequal toll of the pandemic on structurally marginalized populations.

These inequities are rooted in structural forces that influence exposure risk, underlying health status, and access to timely care. Long-standing residential and occupational segregation, concentrated poverty, and unequal access to health services—key social determinants of health—have left communities of color disproportionately vulnerable during public health crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic [4,5]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has emphasized that these conditions are shaped by systemic and structural racism, which adversely affects health and underlies elevated risks among racial and ethnic minority populations [5]. In turn, Black and Hispanic communities were more likely to be employed in frontline and essential occupations, reside in crowded households, and experience barriers to preventive and outpatient care—conditions that increased exposure risk and delayed clinical presentation during the pandemic [6,7,8]. These structural conditions also intersect with established inequities in chronic disease burden, increasing the risk of severe illness once infected in these populations [9].

When COVID-19 infection progresses to severe illness, hospitalization represents a critical juncture at which underlying health vulnerabilities—shaped by social and economic conditions—become clinically significant. Unlike community-based outcomes, inpatient care within a standardized clinical setting involves multiple sequential processes (including diagnosis at admission, treatment, and survival) that unfold over the course of hospitalization. As a result, hospitalization provides a uniquely informative context for examining how structural inequities and baseline health risks intersect and manifest across different stages of care, rather than as a single endpoint. This hospitalization-continuum framework is especially relevant for examining health outcomes among socially and economically disadvantaged populations.

Medicaid beneficiaries represent a socially at-risk population in which these intersecting structural, social, and clinical vulnerabilities are especially concentrated. As the primary source of health coverage for low-income adults and a disproportionate share of minoritized populations, Medicaid serves individuals with elevated baseline health risks and persistent social disadvantage [10]. Kentucky provides a salient example: the state’s expanded Medicaid program covers a socioeconomically diverse population, including rural Appalachian communities with a high burden of chronic conditions [10]. Examining hospitalizations among Medicaid beneficiaries in Kentucky therefore provides an opportunity to assess how these intersecting vulnerabilities translate into inequities across the course of inpatient care.

Much of the existing research on COVID-19-related disparities has focused on single outcomes—such as infection, hospitalization, or mortality—examined in isolation [11]. Fewer studies have assessed sequential outcomes across stages of the hospitalization continuum related to COVID-19, including likelihood of diagnosis at admission, excess mortality risk, and racial and ethnic inequities in hospital mortality. To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has systematically examined these multiple stages of care within a Medicaid population. To address this gap, we analyzed a statewide retrospective cohort of Kentucky Medicaid hospitalizations during 2020–2021. This study examines racial and ethnic inequities at multiple stages of this continuum using risk-adjusted analyses, with propensity score matching serving as a confirmatory approach. Specifically, we aimed to: (1) assess racial and ethnic differences in the likelihood of COVID-19 diagnosis at hospital admission; (2) quantify excess risk of hospital mortality associated with COVID-19 compared with non-COVID-19 hospitalizations; and (3) evaluate racial and ethnic inequities in hospital mortality among COVID-19 hospitalizations. By distinguishing inequities reflected at hospital admission from those occurring during inpatient care, this study provides actionable insights to strengthen population health protection as COVID-19 enters an endemic phase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective cohort study of Kentucky Medicaid beneficiaries hospitalized during 2020–2021 was conducted to evaluate severe COVID-19 outcomes across the hospitalization continuum. The excess risk of in-hospital mortality associated with COVID-19 was estimated, and whether racial and ethnic inequities arose prior to hospitalization or persisted after admission was assessed. The study was reviewed by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board (IRB 23.0537), determined to be non-human subjects research, and was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [12].

2.2. Data Source

Data were obtained from the Kentucky Health Facility and Services (KHFS) claims database for calendar years 2020–2021, maintained by the Cabinet for Health and Family Services [13]. The KHFS database contains encounter-level inpatient discharge records from hospitals statewide in Kentucky, including patient demographics, primary payer, admission and discharge details, hospital characteristics, and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis and procedure codes. The unit of analysis was hospitalization. Because the data were de-identified and did not include unique patient identifiers, repeated admissions could not be linked and were therefore treated as independent encounters.

2.3. Study Sample

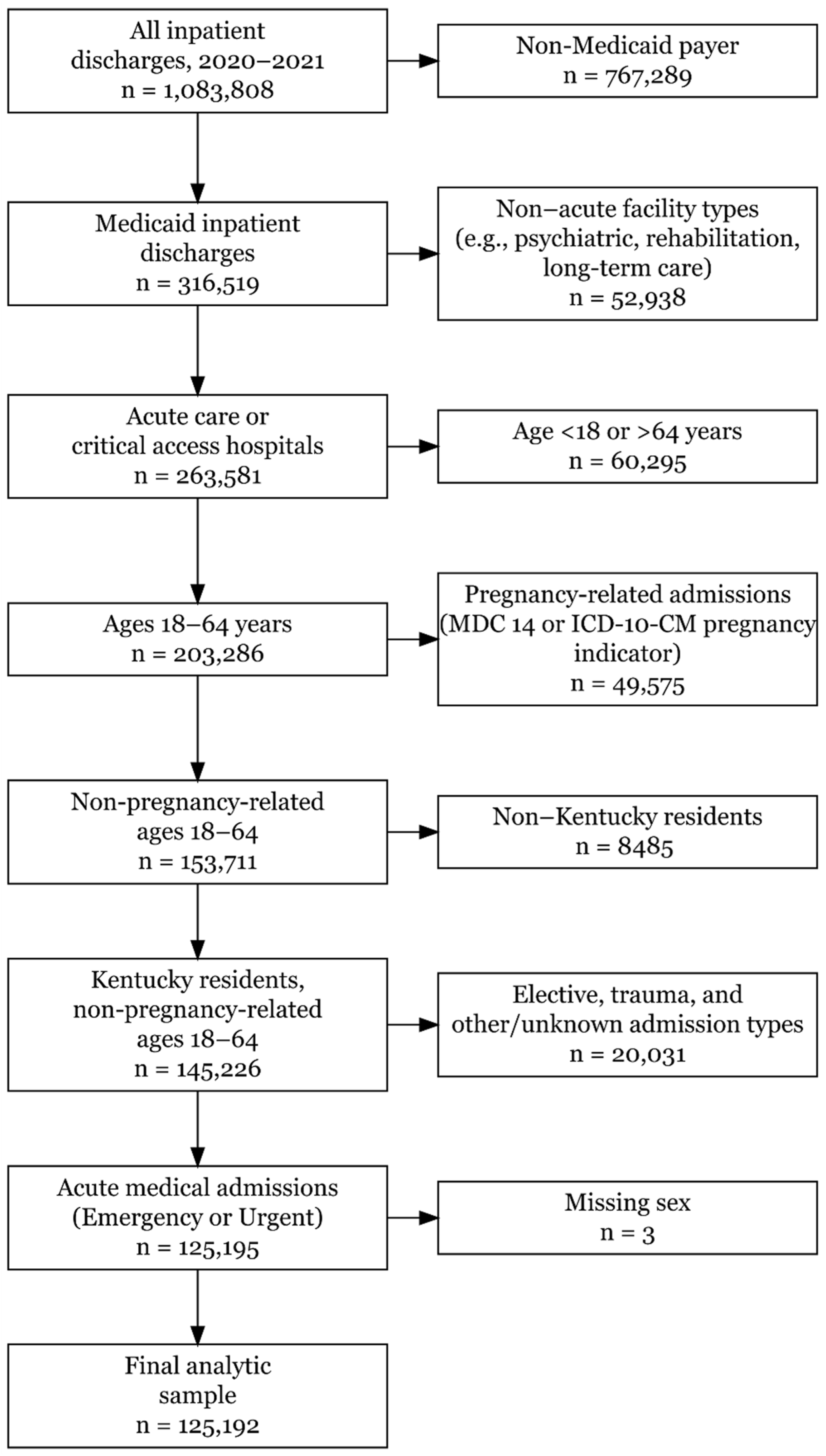

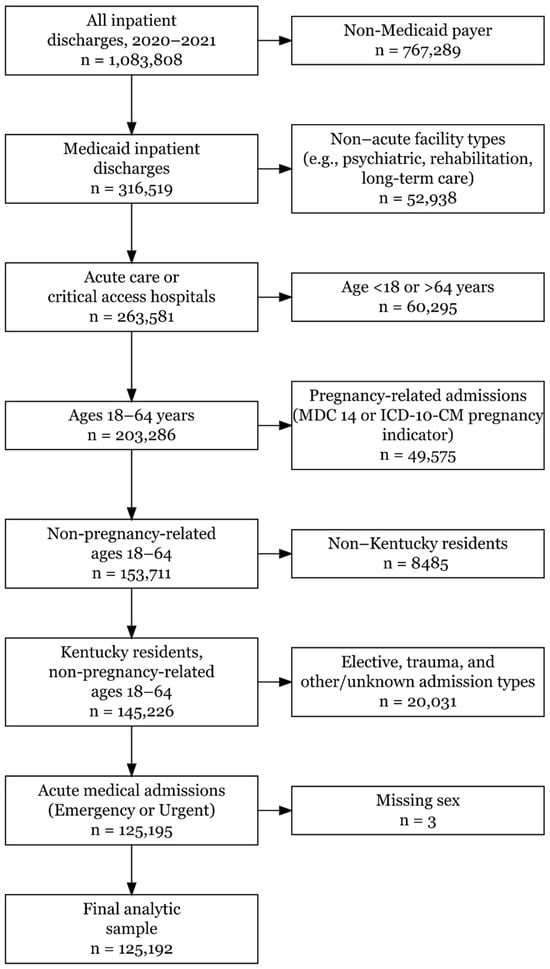

The study sample was derived using sequential inclusion and exclusion criteria, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to derive the final analytic cohort (n = 125,192) from all Kentucky inpatient discharges, 2020–2021.

Hospitalizations were restricted to Medicaid beneficiaries aged 18–64 years who were Kentucky residents and admitted for non-pregnancy-related, acute medical conditions. Pregnancy-related admissions were identified using Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) 14 and ICD-10-CM pregnancy diagnosis codes and excluded from the analytic sample. The analytic cohort was limited to admissions from short-term acute care hospitals and critical access hospitals; admissions from other facility types, elective or trauma-related admissions, and those with missing demographic information were excluded. After these criteria were applied, the final analytic sample comprised 125,192 Medicaid inpatient hospitalizations.

2.4. Outcome and Exposure

Two primary outcomes were examined: COVID-19 diagnosis at hospitalization and in-hospital mortality. Hospitalization with a COVID-19 diagnosis was defined using ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes B97.29 and/or U07.1 [14]. In-hospital mortality was identified using the discharge disposition code indicating death during the hospitalization (code 20). Across analyses, this hospitalization-level COVID-19 diagnosis indicator was modeled as the outcome, the primary exposure, or used to restrict the analytic sample, as appropriate.

2.5. Covariates

All multivariable analyses adjusted for patient- and hospital-level characteristics selected a priori based on existing literature and data availability. Continuous variables were categorized where appropriate to increase interpretability and consistency with prior health services and COVID-19 outcomes research. Patient-level covariates included age, sex, and comorbidity burden measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI score was calculated for each hospitalization using ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes according to a validated coding algorithm and categorized for analysis [15].

Hospital-level covariates included hospital type (acute care vs. critical access), bed size, and ownership. Calendar time was accounted for using discharge quarter to adjust for temporal variation in COVID-19 burden, treatment availability, and hospital capacity during the study period.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced to summarize patient and hospital characteristics for hospitalizations with and without a COVID-19 diagnosis. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and length of stay (LOS) in days was summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs).

To evaluate racial and ethnic inequities across the hospitalization continuum and excess risk of in-hospital mortality associated with COVID-19, a series of multivariable regression analyses were conducted. A logistic regression model was estimated to assess the odds of COVID-19 diagnosis at hospitalization. Race/ethnicity was specified as the primary explanatory variable, with adjustment for patient- and hospital-level covariates. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

Unadjusted in-hospital survival by COVID-19 diagnosis was described using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, with discharge alive treated as a censoring event. Excess in-hospital mortality associated with COVID-19 diagnosis was quantified using Cox proportional hazards regression models, with LOS as the time scale and death during hospitalization as the event. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were reported.

To evaluate whether racial inequities in in-hospital mortality persisted among hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis, analyses were restricted to this subset, and Cox proportional hazards models analogous to those described above were estimated.

In a confirmatory analysis, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to create covariate-balanced, comparable groups of hospitalizations among non-Hispanic (NH) Black and NH White individuals with a COVID-19 diagnosis. Matching was performed on patient- and hospital-level covariates using nearest-neighbor 1:1 matching without replacement and a caliper of 0.05 on the propensity score. Cox proportional hazards regression was then repeated in the matched sample to confirm findings on in-hospital mortality.

In all regression models, robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level were used to account for correlation among hospitalizations within the same facility. Proportional hazards assumptions for Cox models were assessed using standard diagnostic methods, including log–log survival plots and Schoenfeld residuals, with no substantive violations observed. This was a hypothesis-driven comparative analysis; therefore, multiple testing corrections were not applied to avoid overly conservative inference. The data were managed in KNIME (version 5.1) and analyzed in Stata (version 18). Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided tests with α = 0.05.

2.7. Sensitivity Analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the primary modeling assumptions and findings. First, Cox proportional hazards models for in-hospital mortality were repeated after excluding hospitalizations with LOS shorter than 1 day or longer than 60 days, which may reflect atypical clinical courses or administrative irregularities.

Second, comorbidity specification was evaluated by replacing categorical CCI measures with the continuous CCI score in both logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models. Third, an alternative propensity score-matched sample of hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis was constructed using 1:2 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement and a caliper of 0.10, and a Cox proportional hazards model was re-estimated to assess sensitivity to the matching ratio and caliper width.

All sensitivity analyses used the same covariates as their corresponding primary models. Detailed results, including full Cox model estimates for hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis, propensity score matching diagnostics from the 1:1 matched analysis, and additional sensitivity analyses, are provided in the Appendix A.

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample and Cohort Derivation

After applying sequential inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1), 125,192 hospitalizations among Medicaid-enrolled Kentucky residents aged 18–64 years during 2020–2021 comprised the analytic cohort.

3.2. Descriptive Characteristics by COVID-19 Diagnosis

Among the 125,192 hospitalizations, 8409 (6.7%) had a COVID-19 diagnosis and 116,783 (93.3%) did not (Table 1). Hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis were more concentrated in older age groups; individuals aged 60–64 years accounted for 1492 (17.7%) COVID-19 hospitalizations compared with 15,731 (13.5%) non-COVID-19 hospitalizations. Sex distributions were similar across groups, with females comprising 4285 (51.0%) COVID-19 hospitalizations and 57,393 (49.1%) non-COVID-19 hospitalizations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Hospitalizations Among Medicaid Patients by COVID-19 Status, Kentucky, 2020–2021.

Overall, hospitalizations among non-Hispanic White patients comprised the majority of encounters. Among Hispanic patients, COVID-19 hospitalizations accounted for a larger share (556; 6.6%) than non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (2452; 2.1%), whereas the proportions of hospitalizations among non-Hispanic Black patients were similar across COVID-19 (1253; 14.9%) and non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (15,189; 13.0%).

Median length of stay was longer for COVID-19 hospitalizations (5 days; IQR, 3–9) than for non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (3 days; IQR, 2–6). The distribution of Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) categories differed between COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 hospitalizations; a smaller share of COVID-19 hospitalizations fell into the highest category (≥5: 1941; 23.1%) compared with non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (≥5: 34,403; 29.5%).

COVID-19 hospitalizations occurred more frequently in critical access hospitals (3215; 38.2%) than non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (40,545; 34.7%). COVID-19 hospitalizations were also concentrated in larger hospital bed-size categories and varied across discharge quarters, with peaks in 2020 Q4, 2021 Q1, and 2021 Q3.

3.3. Adjusted Odds of COVID-19 Diagnosis at Hospitalization

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, race and ethnicity were associated with the odds of COVID-19 diagnosis at hospitalization (Table 2). Compared with hospitalizations among non-Hispanic White patients, higher adjusted odds of COVID-19 diagnosis were observed for hospitalizations among non-Hispanic Black (aOR = 1.41; 95% CI, 1.26–1.59), Hispanic (aOR = 4.14; 95% CI, 3.38–5.08), non-Hispanic Asian (aOR = 2.59; 95% CI, 1.98–3.38), and non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander patients (aOR = 4.07; 95% CI, 2.52–6.57). Increasing age was associated with higher adjusted odds of COVID-19 diagnosis relative to ages 18–20, with the highest odds among hospitalizations of patients aged 60–64 years (aOR = 2.91; 95% CI, 2.29–3.69). Hospitalizations among female patients had slightly higher adjusted odds of COVID-19 diagnosis than those among male patients (aOR = 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05–1.16). Adjusted odds varied across discharge quarters, with elevated odds observed during late 2020 and throughout 2021.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds of COVID-19 Diagnosis at Hospitalization Among Medicaid Beneficiaries, Kentucky, 2020–2021.

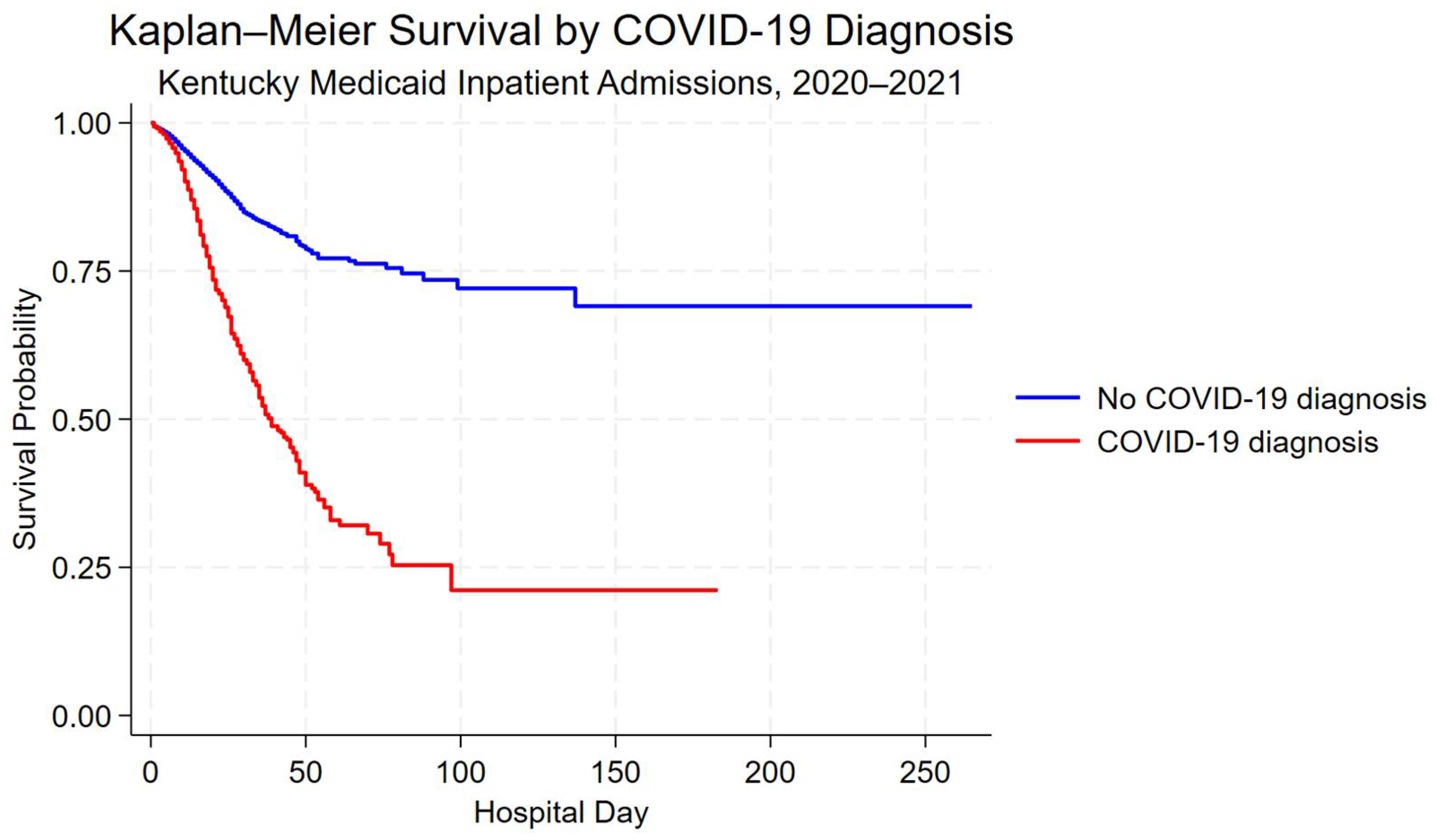

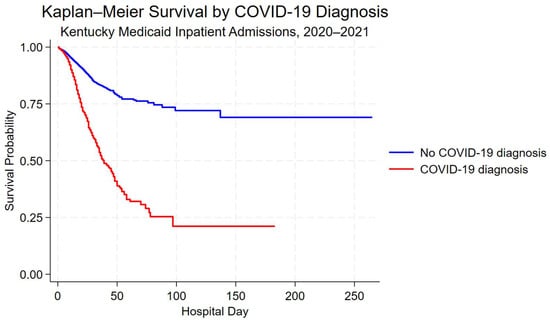

3.4. Unadjusted Survival by COVID-19 Diagnosis

Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrated lower unadjusted in-hospital survival among hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis compared with those without a COVID-19 diagnosis (Figure 2). Differences in survival probability were most pronounced during the first 60 days of hospitalization.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for hospitalizations with and without a COVID-19 diagnosis among Kentucky Medicaid beneficiaries, 2020–2021. Survival time is measured in-hospital days; discharge alive was treated as a censoring event.

3.5. Adjusted In-Hospital Mortality: COVID-19 vs. Non-COVID-19 Hospitalizations

In adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, COVID-19 diagnosis was associated with a higher hazard of in-hospital mortality compared with non-COVID-19 hospitalizations (aHR = 2.38; 95% CI, 2.09–2.70) (Table 3). Increasing age was associated with progressively higher hazards of mortality relative to ages 18–20, with the highest hazards observed among hospitalizations of patients aged 55–59 years (aHR = 1.88; 95% CI, 1.16–3.05) and 60–64 years (aHR = 2.15; 95% CI, 1.34–3.45).

Table 3.

Adjusted Hazard of Inpatient Mortality for COVID-19 vs. Non-COVID-19 Hospitalizations Among Medicaid Patients, Kentucky, 2020–2021.

Compared with hospitalizations among non-Hispanic White patients, hospitalizations among non-Hispanic Black patients had a lower adjusted hazard of in-hospital mortality (aHR = 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70–0.94). Higher CCI categories were associated with increasing mortality hazards, with the highest hazard observed among hospitalizations with CCI ≥5 (aHR = 2.61; 95% CI, 2.01–3.38).

3.6. Racial Inequities in In-Hospital Mortality Among COVID-19 Hospitalizations

Among hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis (n = 7757; deaths = 650), adjusted Cox regression models showed no difference in in-hospital mortality between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients (aHR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.70–1.13; Table 4). Full model estimates are provided in Appendix A Table A1.

Table 4.

Black–White Differences in In-Hospital Mortality Among Medicaid Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19, Kentucky, 2020–2021.

In confirmatory analyses using 1:1 propensity score-matched samples of hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients (n = 1889; deaths = 114), the adjusted hazard of in-hospital mortality did not differ between groups (aHR = 1.10; 95% CI, 0.69–1.74) (Table 4). Covariate balance improved after matching, with standardized differences below 0.10 for most covariates (Appendix A Table A2).

3.7. Sensitivity Analyses

Results were robust across sensitivity analyses (Appendix A Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5). Excluding hospitalizations with length of stay shorter than 1 day or longer than 60 days yielded similar hazard estimates for in-hospital mortality among hospitalizations with and without a COVID-19 diagnosis (HR = 2.35; 95% CI, 2.08–2.65), as well as for hospitalizations among non-Hispanic Black versus non-Hispanic White patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis (HR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.71–1.14). Replacing categorical CCI measures with a continuous CCI score produced comparable estimates for COVID-19 diagnosis at hospitalization and in-hospital mortality. Alternative propensity score matching using 1:2 nearest-neighbor matching also yielded similar mortality hazard estimates (HR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.63–1.17).

4. Discussion

In this statewide analysis of hospitalizations among Medicaid beneficiaries in Kentucky during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021), racial and ethnic inequities were observed across multiple stages of the hospitalization continuum. Compared with non-Hispanic White patients, non-Hispanic Black patients were more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 rather than other conditions, indicating a disproportionate burden at the point of hospital admission. In the full cohort model, hospitalizations involving a COVID-19 diagnosis were associated with substantially higher in-hospital mortality compared with non-COVID-19 hospitalizations. Further, in-hospital mortality risk was modestly lower among non-Hispanic Black patients than among non-Hispanic White patients—a pattern likely reflecting differences in case mix or admission thresholds rather than COVID-19-specific mortality differences.

When analyses were restricted to COVID-19 hospitalizations, adjusted models did not show Black–White differences in in-hospital mortality. Together, these findings suggest that racial inequities were more pronounced at the point of hospitalization and in the distribution of COVID-19 admissions, not within COVID-19-specific inpatient mortality. This distinction underscores the importance of examining multiple stages of hospitalization when assessing racial and ethnic inequities.

For instance, the distribution of COVID-19 hospitalizations by race and ethnicity in this study mirrored patterns observed nationally during the pandemic [16,17]. Greater exposure risk stemming from structural inequities—including frontline and essential occupations, crowded living conditions, and barriers to timely outpatient care—likely contributed to higher infection risk and subsequent hospitalization among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic communities [18]. National surveillance has repeatedly documented substantially higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates among non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Hispanic populations compared with non-Hispanic White populations during the early pandemic period [16,17].

Importantly, within Kentucky’s Medicaid population, these patterns persisted despite uniform insurance coverage, suggesting that coverage alone was insufficient to mitigate disparities in severe COVID-19 illness requiring hospitalization. This underscores the role of upstream population- and environmental-level factors—such as occupational exposures, housing conditions, structural barriers to care, comorbidity burden, and healthcare-seeking patterns—in shaping which patients arrive at the hospital with COVID-19.

Beyond differences in who was hospitalized with COVID-19, outcomes during inpatient care further highlight the burden associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations. Hospitalizations involving a COVID-19 diagnosis were associated with a substantially higher risk of in-hospital mortality compared with non-COVID-19 hospitalizations. This elevated mortality persisted after adjustment for demographic characteristics and comorbidity burden, indicating that differences in patient case mix alone do not fully explain the observed mortality gap. Consistent with these findings, national evidence from the early pandemic period documented markedly higher in-hospital death rates among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 compared with other acute conditions [19].

From a public health perspective, these findings underscore that preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among high-risk populations remains critical, even as the pandemic transitions to an endemic phase. The markedly higher mortality associated with COVID-19 once inpatient care is required highlights the importance of timely access to vaccination, workplace protections (e.g., paid sick leave, PPE, safer conditions), early outpatient evaluation, and effective antiviral treatment—particularly for Medicaid populations facing structural barriers to care [19,20]. Strengthening these upstream and early-care interventions may reduce the disproportionate burden of severe disease that ultimately manifests within hospitals [21].

Several large multisite studies have found that, after adjustment for demographic and clinical factors, racial differences in COVID-19 in-hospital mortality are often attenuated or not statistically significant, even as disparities in infection and hospitalization persist [22,23]. Consistent with this evidence, adjusted analyses restricted to hospitalizations with a COVID-19 diagnosis did not demonstrate differences in in-hospital mortality between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients. This contrast suggests that inequities in this Medicaid population were more strongly reflected in who arrived at the hospital with COVID-19 than in mortality once hospitalized.

Notably, the absence of observed mortality differences within COVID-19 hospitalizations should not be interpreted as evidence that inpatient care processes were equivalent across racial groups. Residual differences in illness severity at presentation, unmeasured clinical factors, and social conditions preceding admission may continue to influence outcomes in ways not fully captured by administrative data. Confirmatory propensity score-matched analyses among COVID-19 hospitalizations yielded consistent results, supporting the interpretation that disparities in this cohort were concentrated earlier in the hospitalization continuum rather than during inpatient mortality.

Taken together, the patterns observed here highlight why evaluating multiple points along the hospitalization continuum is essential for identifying where inequities are most pronounced and where interventions may be most effective.

5. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. First, a statewide cohort of Medicaid hospitalizations in Kentucky was analyzed across 2020–2021. The dataset captures inpatient encounters within a single public insurance program, enabling assessment of inequities within a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. This comprehensive coverage reduces potential selection bias related to insurance status and supports stable estimates within the Medicaid population.

Second, inequities were examined across multiple stages of the hospitalization continuum. These stages included likelihood of COVID-19 diagnosis at admission, excess in-hospital mortality associated with COVID-19, and mortality patterns among COVID-19 hospitalizations. This continuum-based approach extends prior studies that often focused on single outcomes in isolation and helps clarify where inequities are most pronounced [11].

Third, rigorous analytic strategies were used to strengthen robustness. Multivariable regression models adjusted for a wide range of demographic and clinical factors, and propensity score matching was used as a confirmatory approach for key comparisons. Consistent findings across analytic approaches increase confidence in the robustness of the observed associations, while acknowledging the non-causal nature of the study. Finally, the use of administrative claims data enabled population-level analyses that are difficult to achieve in smaller clinical cohorts.

Several limitations should be considered. First, as an observational retrospective study, the analyses cannot establish causal relationships between race/ethnicity, COVID-19 diagnosis, and in-hospital mortality. Second, although models adjusted for a wide range of covariates, residual confounding remains possible. Because this study relied on administrative claims data, direct measures of illness severity at presentation (e.g., physiologic indicators, laboratory values, or radiographic findings) were unavailable and may influence in-hospital mortality. In addition, diagnoses, comorbidities, and race/ethnicity were derived from administrative records and may be misclassified, and claims data may not fully capture clinical nuance or key social risk factors relevant to COVID-19 outcomes.

Third, hospitalizations—not individual patients—were the unit of analysis. Repeating admissions by the same individual could contribute multiple observations and may influence estimates despite adjustment. Differences in the severity of illness at the time of hospital admission across racial and ethnic groups may contribute to selection bias, particularly when examining disparities at the point of hospitalization.

Fourth, race and ethnicity categories were constrained by data availability and aggregation requirements. More granular subgroups (e.g., Hispanic origin groups) could not be examined, and small sample sizes limited precision for some populations, including Asian and American Indian/Alaska Native patients. Fifth, the study period reflects the early pandemic (2020–2021), before widespread vaccine uptake and the introduction of newer COVID-19 therapies. Patterns may have evolved later, although the structural drivers of inequity emphasized here remain relevant for preparedness and future public health emergencies.

Finally, because the analysis was limited to Medicaid beneficiaries in Kentucky, findings may not be fully generalizable to other populations or geographic settings. Future studies incorporating patient-level longitudinal data, clinical severity measures, and broader geographic coverage may further clarify the mechanisms underlying observed disparities.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that racial and ethnic inequities in COVID-19 outcomes among Medicaid beneficiaries were concentrated at the point of hospitalization rather than within COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. Non-Hispanic Black Medicaid patients bore a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 hospital admissions, consistent with upstream structural and social conditions that shape exposure risk and baseline health prior to hospitalization.

These findings highlight the importance of distinguishing inequities reflected at hospital entry from those occurring during inpatient care. As COVID-19 enters an endemic phase and severe outcomes become increasingly concentrated among socioeconomically vulnerable populations, equitable response will depend on prevention, early diagnosis, and timely access to outpatient treatment. Medicaid programs and public health systems remain central to reducing avoidable hospitalizations by addressing risks that precede hospital entry.

Evaluating outcomes across multiple stages of hospitalization clarifies where inequities arise and where interventions may be most effective. Preparedness strategies that strengthen early prevention and equitable access to care—particularly for Medicaid populations—will be essential to reducing disparities in severe disease during COVID-19 and future public health emergencies.

Author Contributions

S.H.S.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, and supervision. B.B.L.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, and formal analysis. M.G.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, and formal analysis. S.M.K.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, and formal analysis. F.S.: conceptualization, methodology, and validation. F.N.K.: conceptualization, methodology, and validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board review was conducted at the University of Louisville (IRB No. 23.0537, approval date: 28 July 2023), and the study was classified as non-human subjects research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Kentucky Health Facility and Services (KHFS) inpatient data was used to identify Medicaid patients. This data can be requested from the Commonwealth Institute of Kentucky, University of Louisville.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Model for In-Hospital Mortality Among COVID-19-Positive Medicaid Patients, Kentucky, 2020–2021 (n = 7757; deaths = 650).

Table A1.

Full Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Model for In-Hospital Mortality Among COVID-19-Positive Medicaid Patients, Kentucky, 2020–2021 (n = 7757; deaths = 650).

| Adjusted HR 1 | 95% CI 2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age Group (ref = 18–20) | ||||

| 21–24 | 1.29 | 0.41 | 4.00 | 0.664 |

| 25–29 | 0.94 | 0.32 | 2.79 | 0.911 |

| 30–34 | 1.86 | 0.59 | 5.84 | 0.289 |

| 35–39 | 1.44 | 0.47 | 4.42 | 0.522 |

| 40–44 | 2.15 | 0.74 | 6.27 | 0.162 |

| 45–49 | 2.25 | 0.77 | 6.59 | 0.141 |

| 50–54 | 2.38 | 0.78 | 7.26 | 0.129 |

| 55–59 | 2.57 | 0.86 | 7.70 | 0.093 |

| 60–64 | 2.92 | 0.96 | 8.86 | 0.058 |

| Sex (ref = Male) | ||||

| Female | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.95 | 0.009 |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref = NH White) 3 | ||||

| NH Black | 0.89 | 0.70 | 1.13 | 0.326 |

| NH Asian | 0.84 | 0.34 | 2.12 | 0.717 |

| NH AI/AN | 1.58 | 0.10 | 24.52 | 0.744 |

| NH NH/PI | 0.93 | 0.23 | 3.69 | 0.914 |

| Hispanic | 0.91 | 0.68 | 1.21 | 0.507 |

| CCI Score (ref = 0) 4 | ||||

| 1–2 | 1.28 | 1.04 | 1.58 | 0.018 |

| 3–4 | 1.06 | 0.81 | 1.40 | 0.652 |

| ≥5 | 1.40 | 1.09 | 1.79 | 0.008 |

| Hospital Type (ref = Critical Access) 5 | ||||

| Acute Care | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 0.004 |

| Hospital Bed Size (ref = <1000 beds) | ||||

| 1000–2999 beds | 0.84 | 0.43 | 1.64 | 0.611 |

| 3000–5999 beds | 1.03 | 0.51 | 2.08 | 0.928 |

| 6000–9999 beds | 1.18 | 0.60 | 2.33 | 0.633 |

| Over 9999 beds | 1.15 | 0.62 | 2.11 | 0.665 |

| Hospital Ownership (ref = Non-Profit) | ||||

| For-Profit | 0.97 | 0.72 | 1.33 | 0.869 |

| Discharge Quarter (ref = 2020 Q1) | ||||

| 2020 Q2 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 1.47 | 0.171 |

| 2020 Q3 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.045 |

| 2020 Q4 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 1.41 | 0.213 |

| 2021 Q1 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 0.033 |

| 2021 Q2 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 1.21 | 0.110 |

| 2021 Q3 | 0.93 | 0.33 | 2.61 | 0.885 |

| 2021 Q4 | 0.63 | 0.23 | 1.74 | 0.369 |

1 HR = Hazard ratio. 2 CI = confidence interval. 3 Race/ethnicity categories are mutually exclusive. NH = Non-Hispanic; AI/AN = American Indian or Alaska Native; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. 4 CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index. 5 Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) are CMS-designated rural facilities with limited inpatient capacity and 24-h emergency care.

Table A2.

Propensity Score Matching Summary, Covariate Balance, and Matched Cox Model for Black–White Differences in In-Hospital Mortality Among COVID-19-Positive Medicaid Patients, Kentucky, 2020–2021.

Table A2.

Propensity Score Matching Summary, Covariate Balance, and Matched Cox Model for Black–White Differences in In-Hospital Mortality Among COVID-19-Positive Medicaid Patients, Kentucky, 2020–2021.

| Panel A. Matching Summary | ||

| NH White 1 | NH Black 1 | |

| Unmatched sample (COVID-19-positive inpatients) | 6504 | 1253 |

| Matched 1:1 analytic sample | 636 | 1253 |

| Total matched sample | 1889 | — |

| Panel B. Balance Statistics Before and After Matching (Values shown are proportions in NH White vs. NH Black groups; SD = Absolute Standardized Difference) | ||

| Characteristic | Before Matching (NH White vs. NH Black, SD 4) | After Matching (NH White vs. NH Black, SD 4) |

| Death (in-hospital) | 0.064 vs. 0.088, SD = 0.084 | 0.064 vs. 0.069, SD = 0.015 |

| Age Group (ref = 18–20) | ||

| 21–24 | 0.026 vs. 0.040, SD = 0.077 | 0.047 vs. 0.040, SD = 0.036 |

| 25–29 | 0.055 vs. 0.083, SD = 0.110 | 0.097 vs. 0.083, SD = 0.051 |

| 30–34 | 0.066 vs. 0.087, SD = 0.077 | 0.085 vs. 0.087, SD = 0.007 |

| 35–39 | 0.088 vs. 0.081, SD = 0.023 | 0.091 vs. 0.081, SD = 0.035 |

| 40–44 | 0.104 vs. 0.117, SD = 0.043 | 0.113 vs. 0.117, SD = 0.013 |

| 45–49 | 0.117 vs. 0.120, SD = 0.008 | 0.112 vs. 0.120, SD = 0.025 |

| 50–54 | 0.160 vs. 0.148, SD = 0.034 | 0.148 vs. 0.148, SD = 0.000 |

| 55–59 | 0.181 vs. 0.152, SD = 0.076 | 0.151 vs. 0.152, SD = 0.004 |

| 60–64 | 0.188 vs. 0.150, SD = 0.101 | 0.146 vs. 0.150, SD = 0.011 |

| Sex (ref = Male) | ||

| Female | 0.517 vs. 0.516, SD = 0.002 | 0.498 vs. 0.516, SD = 0.036 |

| CCI Score (ref = 0) 2 | ||

| 1–2 | 0.318 vs. 0.308, SD = 0.022 | 0.318 vs. 0.308, SD = 0.021 |

| 3–4 | 0.132 vs. 0.153, SD = 0.062 | 0.154 vs. 0.153, SD = 0.002 |

| ≥5 | 0.236 vs. 0.247, SD = 0.024 | 0.237 vs. 0.247, SD = 0.021 |

| Hospital Type (ref = Critical Access) 3 | ||

| Acute Care | 0.463 vs. 0.113, SD = 0.840 | 0.197 vs. 0.113, SD = 0.234 |

| Hospital Bed Size (ref = <1000 beds) | ||

| 1000–2999 beds | 0.106 vs. 0.028, SD = 0.315 | 0.035 vs. 0.028, SD = 0.038 |

| 3000–5999 beds | 0.154 vs. 0.089, SD = 0.202 | 0.126 vs. 0.089, SD = 0.120 |

| 6000–9999 beds | 0.169 vs. 0.161, SD = 0.022 | 0.223 vs. 0.161, SD = 0.158 |

| Over 9999 beds | 0.541 vs. 0.720, SD = 0.378 | 0.612 vs. 0.720, SD = 0.231 |

| Hospital Ownership (ref = Non-Profit) | ||

| For-Profit | 0.106 vs. 0.052, SD = 0.201 | 0.080 vs. 0.052, SD = 0.114 |

| Discharge Quarter (ref = 2020 Q1) | ||

| 2020 Q2 | 0.026 vs. 0.071, SD = 0.208 | 0.072 vs. 0.071, SD = 0.005 |

| 2020 Q3 | 0.046 vs. 0.104, SD = 0.223 | 0.101 vs. 0.104, SD = 0.010 |

| 2020 Q4 | 0.148 vs. 0.171, SD = 0.061 | 0.176 vs. 0.171, SD = 0.014 |

| 2021 Q1 | 0.160 vs. 0.148, SD = 0.033 | 0.148 vs. 0.148, SD = 0.000 |

| 2021 Q2 | 0.065 vs. 0.073, SD = 0.035 | 0.090 vs. 0.073, SD = 0.059 |

| 2021 Q3 | 0.329 vs. 0.241, SD = 0.197 | 0.217 vs. 0.241, SD = 0.057 |

| 2021 Q4 | 0.221 vs. 0.187, SD = 0.085 | 0.195 vs. 0.187, SD = 0.021 |

| Panel C. Propensity Score-Matched Cox Proportional Hazards Model | ||

| Group Comparison | Adjusted HR (95% CI [Lower—Upper]) | p-value |

| NH Black (ref = NH White) | 1.1 (0.69–1.74) | 0.692 |

1 NH White = Non-Hispanic White; NH Black = Non-Hispanic Black. 2 CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index. 3 Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) are CMS-designated rural facilities with limited inpatient capacity and 24-h emergency care. 4 Standardized differences <0.10 indicate good covariate balance. Note: Values represent the proportion of patients in each covariate category within NH White and NH Black groups. For example, “0.026 vs. 0.040” indicates 2.6% of NH White patients and 4.0% of NH Black patients were ages 21–24. The standardized difference (SD) quantifies balance between groups; SD < 0.10 indicates acceptable balance. Death is the primary outcome and was not used in the matching algorithm. Proportions are shown here for descriptive comparison only. Standardized differences reflect absolute differences in outcome prevalence before and after matching.

Table A3.

Sensitivity Analysis 1: Cox Models Excluding Length of Stay <1 or >60 Days.

Table A3.

Sensitivity Analysis 1: Cox Models Excluding Length of Stay <1 or >60 Days.

| Outcome | Sample (LOS Restricted to 1–60 Days) | Key Exposure/Comparison | Adjusted Effect (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality (Cox model) | All Medicaid inpatient stays (n = 124,957; 3257 deaths) | COVID-19-positive vs. non-COVID-19 inpatient stays | HR = 2.35 (95% CI: 2.08–2.65) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (Cox model) | COVID-19-positive inpatients (n = 8371; 689 deaths) | NH Black vs. NH White | HR = 0.90 (95% CI: 0.71–1.14) | 0.390 |

Sensitivity Analysis 1 excluded admissions with length of stay <1 day or >60 days and re-estimated the multivariable Cox models used in the primary analysis. All covariates matched the primary specifications, and robust standard errors were clustered by hospital ID. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; LOS = length of stay; NH = non-Hispanic.

Table A4.

Sensitivity Analysis 2: Models Using Continuous Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Table A4.

Sensitivity Analysis 2: Models Using Continuous Charlson Comorbidity Index.

| Outcome | Sample | Key Exposure/Comparison | Adjusted Effect (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 diagnosis among hospitalized patients (logistic regression) | All Medicaid inpatient stays (n = 125,192) | NH Black vs. NH White | OR = 1.40 (95% CI: 1.25–1.58) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (Cox model) | All Medicaid inpatient stays (n = 125,192) | COVID-19-positive vs. non-COVID-19 inpatient stays | HR = 2.40 (95% CI: 2.12–2.71) | <0.001 |

Sensitivity Analysis 2 replaced Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) categories with the continuous CCI score in both models. All other covariates matched the primary specifications, and robust standard errors were clustered by hospital ID. OR = odds ratio; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; NH = non-Hispanic.

Table A5.

Sensitivity Analysis 3: Alternative Propensity Score-Matched Cox Model for COVID-19-Positive NH Black vs. NH White Patients (1:2 Matching).

Table A5.

Sensitivity Analysis 3: Alternative Propensity Score-Matched Cox Model for COVID-19-Positive NH Black vs. NH White Patients (1:2 Matching).

| Outcome | Sample | Matching Specification | Key Exposure/Comparison | Adjusted Effect (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality (Cox model) | COVID-19-positive NH Black and NH White inpatients (n = 2455; 164 deaths) | 1:2 nearest-neighbor propensity score matching (caliper = 0.10) on age group, sex, CCI category, hospital class, bed size, ownership, and discharge quarter | NH Black vs. NH White | HR = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.63–1.17) | 0.330 |

Sensitivity Analysis 3 re-estimated the propensity score-matched Cox model among COVID-19-positive NH Black and NH White patients using 1:2 nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.10. Matching variables included age group; sex; CCI category; hospital class; bed size; ownership; and discharge quarter. Robust standard errors were clustered by hospital ID. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; NH = non-Hispanic.

References

- Truman, B.I.; Chang, M.-H.; Moonesinghe, R. Provisional COVID-19 Age-Adjusted Death Rates, by Race and Ethnicity—United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.U.; Thirumalareddy, J.; Gupta, J.S.; Abdul Jabbar, A.B. Disparities in COVID-19 Mortality in the United States, 2020–2023. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiga, S.; Corallo, B.; Pham, O. Racial Disparities in COVID-19: Key Findings from Available Data and Analysis; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin, Z.; Lee, E.K. The Role of Poverty and Racial Discrimination in Exacerbating the Health Consequences of COVID-19. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.; Buhr, R.G.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hsu, J.J.; Brown, A.F.; Ziaeian, B. Racial and Ethnic Disparities and the National Burden of COVID-19 on Inpatient Hospitalizations: A Retrospective Study in the United States in the Year 2020. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2025, 12, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haro-Ramos, A.Y.; Brown, T.T.; Deardorff, J.; Aguilera, A.; Pollack Porter, K.M.; Rodriguez, H.P. Frontline Work and Racial Disparities in Social and Economic Pandemic Stressors during the First COVID-19 Surge. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, Y.; Roll, S.; Miller, S.; Lee, H.; Larimore, S.; Grinstein-Weiss, M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Housing Instability During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Assets and Income Shocks. J. Econ. Race Policy 2023, 6, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehmer, T.K.; Koumans, E.H.; Skillen, E.L.; Kappelman, M.D.; Carton, T.W.; Patel, A.; August, E.M.; Bernstein, R.; Denson, J.L.; Draper, C.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Outpatient Treatment of COVID-19—United States, January-July 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kompaniyets, L.; Pennington, A.F.; Goodman, A.B.; Rosenblum, H.G.; Belay, B.; Ko, J.Y.; Chevinsky, J.R.; Schieber, L.Z.; Summers, A.D.; Lavery, A.M.; et al. Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020-March 2021. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakib, S.H.; Little, B.B.; Karimi, S.M.; Goldsby, M. COVID-19 Mortality Among Hospitalized Medicaid Patients in Kentucky (2020–2021): A Geospatial Study of Social, Medical, and Environmental Risk Factors. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, S.; John, D.; Li, W.T.; Li, Y.; Mattingly-App, A.; Jain, S.; Chang, E.Y.; Ongkeko, W.M. Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic-Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Facilities and Services Data—Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Available online: https://www.chfs.ky.gov/agencies/ohda/Pages/hfsd.aspx (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Kadri, S.S.; Gundrum, J.; Warner, S.; Cao, Z.; Babiker, A.; Klompas, M.; Rosenthal, N. Uptake and Accuracy of the Diagnosis Code for COVID-19 Among US Hospitalizations. JAMA 2020, 324, 2553–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasheen, W.P.; Cordier, T.; Gumpina, R.; Haugh, G.; Davis, J.; Renda, A. Charlson Comorbidity Index: ICD-9 Update and ICD-10 Translation. Am. Health Drug Benefits 2019, 12, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thielke, A.; Curtis, P.; King, V. Addressing COVID-19 Health Disparities: Opportunities for Medicaid Programs; Issue Brief; Milbank Memorial Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, A.M.; Garg, S.; Pham, H.; Whitaker, M.; Anglin, O.; O’Halloran, A.; Milucky, J.; Patel, K.; Taylor, C.; Wortham, J.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Rates of COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit Admission, and In-Hospital Death in the United States From March 2020 to February 2021. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2130479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakib, S.H.; Little, B.B.; Karimi, S.; McKinney, W.P.; Goldsby, M.; Kong, M. Mediating Effect of the Stay-at-Home Order on the Association between Mobility, Weather, and COVID-19 Infection and Mortality in Indiana and Kentucky: March to May 2020. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Bowe, B.; Maddukuri, G.; Al-Aly, Z. Comparative Evaluation of Clinical Manifestations and Risk of Death in Patients Admitted to Hospital with Covid-19 and Seasonal Influenza: Cohort Study. BMJ 2020, 371, m4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakib, S.; Karimi, S.; McGeeney, J.; Parh, M.; Zarei, H.; Chen, Y.; Goldman, B.; Novario, D.; Schurfranz, M.; Warren, C.; et al. Local Health Department COVID-19 Vaccination Efforts and Associated Outcomes: Evidence from Jefferson County, Kentucky. Vaccines 2025, 13, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakib, S.H.; Antimisiaris, D. Analysis of Polypharmacy in Older Adults Pre- and Post-COVID-19. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 18, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazic, A.; Tilford, J.M.; Martin, B.C.; Rezaeiahari, M.; Goudie, A.; Baghal, A.; Greer, M. In-Hospital Mortality by Race and Ethnicity Among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Using Data From the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative. Am. J. Med. Open 2024, 12, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Martinez, J.; Hirsch, J.S.; Cerise, J.; Lesser, M.; Roswell, R.O.; Davidson, K.W.; Northwell Health COVID-19 Research Consortium. Association of Race/Ethnicity with Mortality in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.