Abstract

The impact of physical health conditions on coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) severity in World Trade Center disaster-exposed populations remains understudied. We examined the association of type, number and diagnosis time of pre-existing health conditions with COVID-19 severity, using the WTC Health Registry (WTCHR). We analyzed 3568 WTCHR enrollees with self-reported severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in a 2021 follow-up survey. COVID-19 severity was measured by self-reported symptom duration (<2, 2–4, and >4 weeks) and hospitalization (hospitalized versus not). Pre-existing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), respiratory conditions, cardiovascular conditions, and diabetes were self-reported and categorized into four groups (no diagnosis, post-9/11, pre-9/11, and undefinable). We used multinomial logistic regression and binary logistic regression to analyze the association of comorbidities with COVID-19 symptom duration and hospitalization, respectively, adjusting for post-traumatic stress disorder and demographic factors. Analysis was also conducted separately by enrollee type: rescue and recovery workers (RRW) vs. community members (non-RRW). Having all four health conditions post-9/11 was associated with longer symptom duration after SARS-CoV-2 infection (>4 weeks) among RRW (AOR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.03–6.87). Reporting a post-9/11 respiratory condition was associated with an increased risk of being hospitalized among RRW and an increased risk of longer symptom duration (>4 weeks) among non-RRW. While post-9/11 diabetes was associated with an increased risk of longer symptom duration among RRW, post-9/11 GERD and pre-9/11 cardiovascular conditions were associated with an increased risk of longer symptom duration and being hospitalized among non-RRW, respectively. The impact of certain health conditions on COVID-19 severity varied across enrollee types and time of diagnosis. Given the lasting health impacts of 9/11-related exposures, targeted medical surveillance and proactive healthcare interventions are critical for mitigating the risk of severe COVID-19 illness in this population.

1. Introduction

The World Trade Center (WTC) attacks on 11 September 2001 killed thousands of people and exposed many more to hazardous materials resulting from the collapse of the Twin Towers and fires from the initial impact [1,2]. Previous studies reported an increased incidence of physical and mental health conditions after 9/11 among the WTC-exposed population compared to the general population. This includes an increased risk of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other respiratory conditions; gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD); cardiovascular conditions; diabetes; and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Given the high burden of mental and physical morbidities in the WTC-exposed population, it is likely that this population is more vulnerable to new and emerging health threats, such as the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), than the general population.

It has been reported that people with severe or multiple physical morbidities are more likely to experience severe or worse clinical outcomes following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection [10,11]. Among the most common health conditions associated with severe COVID-19 illness are cardiovascular diseases and hypertension, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and GERD [10,11,12,13,14]. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis reported that previous use of a proton pump inhibitor, one of the most used drugs for gastric acid suppression, was associated with an increased risk of progression to severe COVID-19 [15].

The risks of physical health conditions associated with 9/11 exposure among exposed populations have been well-studied. Previous studies reported that longer duration and more intense exposure among the WTC-exposed rescue and recovery workers (RRW) are linked to cardiometabolic risk, cardiovascular disease and stroke [16,17,18,19], including higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension and worsening trajectories of glucose and systolic blood pressure over time [16]. Furthermore, the incidences of respiratory conditions such as asthma, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, airway hyperreactivity, and accelerated lung function decline are also increased among the WTC-exposed RRW compared to the general population and are strongly correlated with the intensity and duration of exposure to WTC dust and smoke [20]. These respiratory conditions are linked to metabolic syndrome, which is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Similarly, among the community members (non-RRW), persistent upper and lower respiratory symptoms with lung function abnormalities were also reported for those who were exposed to pulverized dust, gas, and fumes after WTC destruction [21]. Furthermore, upper aerodigestive tract irritation such as GERD may potentially progress to major cardiovascular events and is associated with self-reported myocardial infarction among all of the WTC-exposed population [22]. Because of the heightened prevalence of these health conditions among the WTC-exposed population, which overlap with health conditions associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection outcome, people who were WTC-exposed may be at increased risk for severe COVID-19 illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A previous cohort study of WTC rescue and recovery responders has already reported that those with pre-existing GERD, heart disease, and obstructive airway diseases were more likely to have severe COVID-19 illness than those without any of these conditions [23], while another study of Fire Department of New York responders who served in the WTC disaster reported that having a greater lung function decline rate prior to the pandemic was associated with severe COVID-19 illness [24]. No studies have yet examined the risk of severe COVID-19 outcome among WTC-exposed civilians. Given that WTC-exposed community members generally experienced different types of WTC exposure, risk of health conditions, and had very different demographic characteristics than RRW [21], it is hypothesized that the outcome of COVID-19 infection may differ between WTC-exposed RRW and non-RRW.

In this study, we conducted the first analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infection severity among enrollees in the World Trade Center Health Registry (WTCHR), which includes both RRW and non-RRW exposed to the WTC terrorist attacks. We examined whether the type, time of diagnosis relative to the WTC attacks, and number of post-9/11 physical health conditions in the WTC-exposed population were associated with the severity of COVID-19, as indicated by length of COVID-19 symptoms and related hospitalization in the 9/11-exposed population. We analyzed these associations in both the overall sample and separately for WTC RRW and non-RRW. This study did not collect data on Long COVID, which is addressed in a separate study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

The WTCHR was established in 2002 to conduct longitudinal follow-up on individuals who were exposed to the WTC attacks in New York City on 11 September 2001 (9/11). The methods for recruitment into the WTCHR are described in detail elsewhere [25,26]. In brief, the WTCHR completed enrollment in 2003–2004 and has recruited over 71,000 participants. The cohort in this study includes rescue/recovery workers, lower Manhattan residents, office workers, students, and passersby. All enrollees provided verbal informed consent at enrollment (Wave 1), followed by completion of a detailed questionnaire related to sociodemographic characteristics, WTC exposure, and physical and mental health history. Since enrollment, four subsequent waves of surveys were completed in 2006–2007 (Wave 2), 2011–2012 (Wave 3), 2015–2016 (Wave 4), and 2020–2021 (Wave 5). From April 2020 to February 2021, the Wave 5 survey was disseminated to nearly 40,000 eligible enrollees who completed the WTCHR’s Waves 1, 2, and at least one of the Waves 3 and 4 surveys.

In addition to five waves of survey data collected from the WTCHR cohort, the WTCHR has also conducted more focused, in-depth surveys to monitor and perform surveillance activities on newly emerging conditions. To capture individual-level experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, a COVID-19 survey was developed and distributed to 36,831 eligible enrollees from January through August 2021. A total of 22,301 enrollees responded to the COVID-19 survey. A second WTCHR COVID-19 survey to address Long COVID, among other topics, was fielded between December 2022 and September 2023 among enrollees who had responded to the above COVID-19 survey, and this will be the source for future analyses.

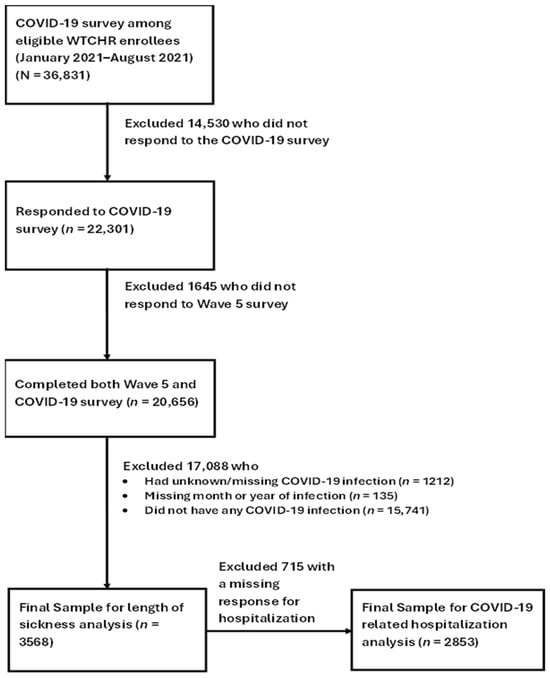

The study sample of the present study consisted of those who reported having SARS-CoV-2 infection on the COVID-19 survey among enrollees who completed both the Wave 5 and the 2021 COVID-19 surveys (n = 20,656). We excluded enrollees who had unknown/missing self-reported COVID-19 infection (n = 1212), missing month or year of infection (n = 135) or reported that they did not have any COVID-19 infection (n = 15,741). The final sample for the analysis of symptom duration included 3568 enrollees. In the analyses involving COVID-19-related hospitalization, we further excluded 715 enrollees with missing data on hospitalization (final sample for hospitalization analysis n = 2853) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Sample Selection and Number of Enrollees in the Analyses.

2.2. Outcome Variables

Severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection was assessed by two variables: (1) duration of SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms, and (2) hospitalization status. Duration was defined by the following question from the COVID-19 survey: “How long were you sick with COVID-19?”, which we categorized into a three-level variable (<2 weeks, between 2 and 4 weeks, and >4 weeks). We chose these cut-off points so that the reference level would conservatively capture mild COVID infections, which have an estimated median duration of approximately 10 days [27]. Hospitalization status was operationalized as a dichotomous variable (hospitalized vs. not hospitalized) derived from the survey question: “How long were you hospitalized for COVID-19 illness?” We did not ask for Long COVID status in the current survey, as this will be addressed in analyses of the WTCHR’s second COVID survey.

2.3. Exposures of Interest

The exposures of interest were self-reported physician-diagnosed pre-existing GERD, respiratory conditions (asthma, reactive airway dysfunction syndrome, and COPD), cardiovascular conditions (hypertension, angina, heart attack, coronary heart disease, and stroke), and diabetes. We chose these specific physical conditions because in addition to being the most common health conditions associated with severe COVID-19 illness, previous studies reported increased risks of these conditions among the WTC-exposed population [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Each of these physical conditions were grouped into 4 categories: (1) No diagnosis, (2) diagnosed post-9/11, (3) diagnosed pre-9/11, and (4) undefinable, based on responses from all primary wave surveys up until Wave 5. A common question regarding whether the enrollee has been told by a doctor or other health professional that he/she had the physical condition, followed by the year he/she was first told of the diagnosis, was asked in all Registry’s primary wave surveys. Responses from all surveys were aggregated and summarized based on step-wise logic rules, taking as precedent the most recent non-missing response over prior responses. Enrollees were considered as diagnosed post-9/11 if they consistently reported a year of diagnosis after 9/11, or if they reported no diagnosis in an earlier survey and later reported the condition with post-9/11 or unknown year of diagnosis, without ever reporting diagnosed pre-9/11. Enrollees were considered as diagnosed pre-9/11 if they reported the condition with a year of diagnosis pre-9/11, without ever reporting no diagnosis or year of diagnosis post-9/11. Undefinable included enrollees who reported no diagnosis, pre-9/11, and post-9/11 inconsistently across all surveys, except for those who reported no diagnosis in an earlier survey followed by diagnosed post-9/11 only. Based on their respective physiological systems, individual post-9/11 physical conditions were also examined as a summary variable of total number of types of post-9/11 physical conditions, ranging from 0 (no post-9/11 physical comorbidities across types reported) to 4 (all post-9/11 physical conditions across types reported).

2.4. Covariates

Covariates were chosen a priori and included in the analyses were age (<45, 45–64, and ≥65 years), gender (female, male), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic Other), marital status (now married/living with partner, divorced or separated, widowed, and never married), educational attainment (less than high school, high school/general education degree (GED), some college, and college graduate or above), household income (<$50K, $50K–<$75K, $75K–$150K, and $150K+), smoking history (never, former, and current), body mass index (BMI) (normal and underweight, overweight, and obese), and ever having probable WTC-related PTSD (Yes vs. No). Probable WTC-related PTSD symptoms were assessed using the 20-item scale version (PCL-5). Enrollees with a score > 33 were considered ever having probable PTSD. All covariates, except for gender, race/ethnicity (Wave 1), were obtained from either Wave 4 or Wave 5 based on the most recent report prior to the COVID infection. Enrollee type (rescue and recovery worker versus community member) was also determined at enrollment (Wave 1).

2.5. Data Analysis

We used multinomial logistic regression to estimate multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for the associations of each of the four types of pre-existing physical conditions (GERD, diabetes, respiratory, and cardiovascular conditions) with duration of COVID-19-related illness, and binary logistic regression for the association with hospitalization, adjusting for covariates. We examined associations in overall sample and stratified by enrollee type (RRW versus non-RRW), which was self-reported at enrollment. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC, USA), with a two-sided significance level of ≤0.05. All procedures and the study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

3. Results

In the study sample of 3568 Registry enrollees who reported having had SARS-CoV-2 infection, 2038 (57.1%) reported being sick with COVID-19 for less than 2 weeks, 903 (25.3%) for 2 to 4 weeks, and 550 (15.4%) for more than four weeks (Table 1). Fifty-three percent of the sample were community members. About fifty-nine percent of the sample had at least one post-9/11 physical health condition prior to COVID-19 diagnosis. Over half of the sample had obtained a college degree or higher. A higher proportion of those who reported being sick for longer than 4 weeks versus less than 2 weeks (30.6% vs. 23.4%) or hospitalized versus not hospitalized for COVID-19 infection (42.2% vs. 24.2%) were 65 years or older. Among those who responded to the hospitalization question (n = 2853), 9.5% (n = 270) reported being hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. Compared to those who reported being sick for less than 2 weeks, those who reported being sick for longer than 4 weeks were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic (10.2% and 13.3% vs. 5.2% and 9.6%, respectively). Similarly, a higher proportion of those who reported being hospitalized for COVID-19 infection versus not hospitalized were non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic (11.9% and 12.2% vs. 6.1% and 11.0%, respectively). Moreover, a higher proportion of those who reported being sick for longer than 4 weeks versus less than 2 weeks or hospitalized for COVID-19 infection versus not hospitalized were obese, had post-9/11 diagnosis of GERD, a respiratory condition, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample by COVID-19 Severity.

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the associations of each comorbid physical conditions by time of diagnosis with length of sickness and hospitalization for COVID-19, respectively. Overall, having a post-9/11 diagnosis of GERD (AOR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.13–1.82) or post-9/11 respiratory condition (AOR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.17–1.98) was significantly associated with being sick for longer than 4 weeks versus less than 2 weeks (Table 2). Having a post-9/11 respiratory condition (AOR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.27–2.49) or pre-9/11 cardiovascular condition (AOR: 2.37, 95% CI: 1.38–4.08) was associated with COVID-19 related hospitalization.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for the Association Between Each Pre-existing Condition and COVID-19 Severity, stratified by time of diagnosis *.

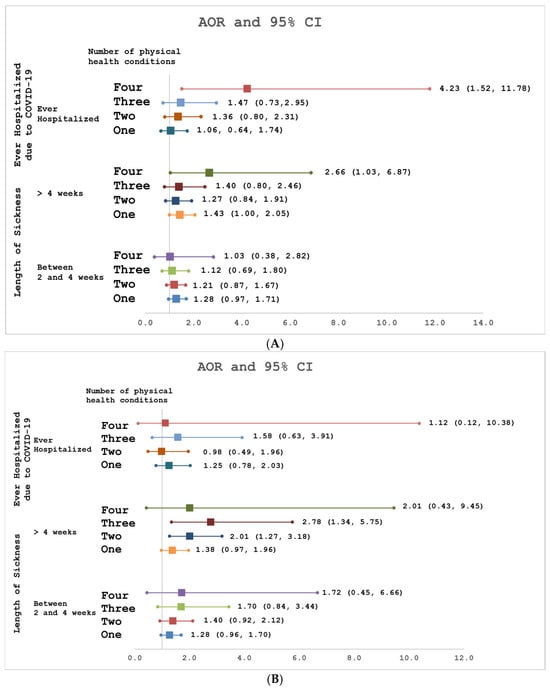

Among rescue and recovery workers, having post-9/11 diabetes (AOR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.02–2.41) was associated with being sick with COVID-19 for >4 weeks compared to <2 weeks. Only having a post-9/11 respiratory condition (AOR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.38–3.39) was associated with being hospitalized for COVD-19. Having all four physical conditions post-9/11 versus none was associated with being sick for >4 versus <2 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection (AOR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.03–6.87) and being hospitalized for COVID-19 (AOR: 4.23, 95% CI: 1.52–11.78) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Association of number of post-9/11 physical conditions with ever hospitalized for COVID and length of sickness among WTC Rescue and Recover Workers. (B) Association of number of post-9/11 physical conditions with ever hospitalized for COVID and length of sickness among WTC-exposed Community Members.

Among community members, having a post-9/11 respiratory condition (AOR: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.36–3.05) or GERD (AOR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.08–2.28) was associated with being sick for >4 weeks compared to <2 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Having a pre-9/11 cardiovascular condition (AOR: 2.99, 95% CI: 1.40–6.43) was associated with being hospitalized for COVID-19. Having three (AOR: 2.78, 95% CI: 1.34–5.75) or two (AOR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.27–3.18) post-9/11 physical conditions versus none was associated with being sick for >4 weeks compared to <2 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 2B). However, having at least one post-9/11 physical condition versus none was not associated with COVID-19 hospitalization.

4. Discussion

Overall, our findings are consistent with research conducted on the general population [10,11,12,13,14]. The associations between certain pre-existing physical health conditions and COVID-19 severity that were reported in the general population were also seen among the WTC-exposed population. Specifically, we found that having a post-9/11 diagnosis of respiratory condition or GERD was associated with being sick for longer duration after SARS-CoV-2 infection among community members, while having a post-9/11 diagnosis of diabetes was associated with being sick for longer duration after SARS-CoV-2 infection among responders. Additionally, while having a post-9/11 respiratory condition was associated with being hospitalized for COVID-19 in responders, having a pre-9/11 cardiovascular condition was associated with being hospitalized for COVID-19 in community members. The likelihood of having a longer duration of sickness and being hospitalized for COVID-19 increased with the number of post-9/11 physical health conditions among RRW. These findings support the need to monitor and provide targeted healthcare for WTC-exposed individuals with pre-existing health conditions, as they often have a higher burden of such conditions compared to the general population and therefore face an increased risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes.

A systematic review of risk factors for severe clinical outcomes revealed that COPD was the most strongly predictive comorbidity for both severe disease and admission to ICU, while dyspnea (i.e., shortness of breath) was the only significant symptom predictive for both severe disease and ICU admission [13]. Respiratory conditions, along with cardiovascular conditions and diabetes, are also widely known to increase the odds of hospitalization after SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general population [10,11,12,13,14]. The mechanisms linking comorbidities to increased COVID-19 severity are not fully understood but may involve increased expression of the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 protein, the primary receptor that SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter human cells [28,29]. Additionally, compromised immune function, chronic systemic inflammation, and underlying organ dysfunction may play a role in exacerbating disease severity in individuals with pre-existing chronic health conditions [28]. Therefore, it is reasonable that a higher number of types of comorbidities that include these conditions is associated with more severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [11].

Among the WTC RRW, we found that having a post-9/11 respiratory condition was associated with a 116% increased risk of being hospitalized for COVID-19. A previous study of COVID-19 severity among WTC responders also reported that having an obstructive airway disease was significantly associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, defined as either having severe symptoms or being admitted to a hospital [16]. A novel finding of this study is that post-9/11 diabetes was associated with longer symptom duration among rescue and recovery workers, which was not reported in Lhuillier’s study [23]. Having multiple physical health conditions is more common among WTC responders than in the general population [30] and, as shown in this study, can further increase the risk of severe COVID-19 illness. Our findings emphasize the importance of managing underlying conditions to not only reduce the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes but also mitigate the risk of severe illness from similar infectious diseases.

This study also provides some of the first data on COVID-19 severity among community members exposed to the WTC terrorist attacks. Interestingly, we found that the same health condition can have a different impact on COVID-19 severity among WTC community members compared to rescue and recovery workers. For example, while post-9/11 diabetes was associated with a longer duration of COVID-19 symptoms in rescue and recovery workers, this association was not observed in community workers. Furthermore, among community members, having post-9/11 GERD and a pre-9/11 cardiovascular condition was associated with increased risk of longer symptom duration and increased risk of being hospitalized, respectively. These associations were not observed among rescue and recovery workers. The reasons for these differences are unclear but may be due to the well-documented differences in demographic statuses, WTC environmental and traumatic exposures, and healthcare access between WTC rescue and recovery workers and community members. For example, our finding on pre-9/11 CVD among community members may implicate the difference in chronicity of the condition between WTC responders and community members, as professional responders often have better cardiovascular health than the general population due to the physical criteria for entry into the occupation. Additionally, WTC community members are relatively more diverse in race/ethnicity, income, education background, and other sociodemographic statuses than rescue and recovery workers [21,30]. They were also exposed to lower levels of the initial dust cloud and lingering environmental contamination in the area. Additionally, the levels of access to healthcare services may differ between these enrollee groups. While the World Trade Center Health Program (WTCHP) provides medically necessary treatment and monitoring for WTC-related conditions at no cost for both Responders and Survivors who were impacted by the disaster for interdisciplinary illnesses, the established enrolment criteria are different for each of these two groups. Taken together, these may explain the difference in impact of COVID-19 severity by the same health condition between the groups. Given that this is the first study to identify these differences, further research is needed to better understand the underlying factors that influence COVID-19 severity across different enrollee groups.

Our study has several limitations. First, we cannot discount the possibility of response bias, as all data in this study are based on self-reported information. The mean number of months between time of COVID survey completion and the month and year of reported infection was 9 months, with a range of 0–19 months. Though it is unlikely for enrollees to forget an important lifetime event such as hospitalization, those who had the infection more recently would be more likely to recall the length of sickness accurately than having the infection earlier in the pandemic. Second, selection bias may have occurred because individuals with no or mild symptoms might have gone undetected and would thus have been excluded from this study. This issue may have been particularly pronounced early in the pandemic when testing was not widely available. Third, the COVID-19 survey was only offered to a subgroup of the WTCHR who had answered several earlier waves, further limiting the generalizability of this study and may skew the results in favor of those who were able to respond to the surveys. Fourth, although COVID-19 severity is associated with a wide range of new or worsened medical conditions across multiple body systems, we focused on physical health conditions that are most frequently documented and clinically impactful in this study. This allowed us to conduct a rigorous and interpretable analysis and to provide a clear foundation for future investigations. Our focuses on these major categories represent a first step, and future work can expand to additional conditions. Lastly, at the time of this study, data on long COVID that was collected in the second WTCHR COVID-19 survey were not readily available. Since having a more severe infection is a risk factor for long COVID [31,32], future studies incorporating these follow-up data to examine the association between acute severity and long COVID are warranted, to improve the understanding of the long-term impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection among WTC-exposed populations.

5. Conclusions

This study reinforces the existing evidence that comorbidities increase the risk of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection severity while also providing new insights into how other underlying factors may modify this relationship among the WTC-exposed population. Notably, we found that the impact of certain health conditions that were diagnosed after 9/11 on COVID-19 severity varied across different enrollee groups, suggesting that differences in demographics, 9/11-related exposures, and access to medical care may influence disease outcomes. These findings underscore the complex interplay between pre-existing health conditions and external factors, highlighting the need for targeted research and healthcare strategies to address the unique risks faced by different populations. Moreover, this study adds to the existing literature by illuminating the indirect impact of WTC exposure on health through heightening of disease severity in the context of a new and emerging health threat, expanding beyond the direct long-term impact of WTC exposure on the development of chronic health conditions. This further underlines the importance of continued monitoring and care of WTC-exposed individuals to prevent further deterioration of health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y., R.D.K., J.L. and J.E.C.; methodology, J.Y., R.D.K. and J.L.; software, J.Y.; validation, J.Y. and J.L.; formal analysis, J.Y.; investigation, J.Y. and J.L.; resources, J.E.C.; data curation, J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y., R.D.K., J.L. and J.E.C.; visualization, J.Y.; supervision, J.E.C.; project administration, J.Y., J.L. and J.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number U50OH009739 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH, the CDC, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (IRB# 02-058, 29 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

The informed consent was obtained from all participants at the establishment of the Registry, conforming to established ethical standards. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

World Trade Center Health Registry data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author following review of applications to the Registry from external researchers. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Prior to 30 April 2009, the Registry was supported by U50/ATU272750 from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), CDC, which included support from the National Center for Environmental Health, CDC; and by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH). The authors thank Janna Metzler, Julia Sisti, and Elizbeth Selkowe from the NYC DOHMH for their critical review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| GED | General education degree |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| WTC | World Trade Center |

| WTCHR | World Trade Center Health Registry |

References

- Landrigan, P.J.; Lioy, P.J.; Thurston, G.; Berkowitz, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chillrud, S.N.; Gavett, S.H.; Georgopoulos, P.G.; Geyh, A.S.; Levin, S.; et al. Health and environmental consequences of the world trade center disaster. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioy, P.J.; Weisel, C.P.; Millette, J.R.; Eisenreich, S.; Vallero, D.; Offenberg, J.; Buckley, B.; Turpin, B.; Zhong, M.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. Characterization of the dust/smoke aerosol that settled east of the World Trade Center (WTC) in lower Manhattan after the collapse of the WTC 11 September 2001. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, H.E.; Yu, S.; Stellman, S.D.; Brackbill, R.M. Injury, intense dust exposure, and chronic disease among survivors of the World Trade Center terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Inj. Epidemiol. 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackbill, R.M.; Cone, J.E.; Farfel, M.R.; Stellman, S.D. Chronic physical health consequences of being injured during the terrorist attacks on World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, R.M.; Hadler, J.L.; DiGrande, L.; Ekenga, C.C.; Farfel, M.R.; Friedman, S.; Perlman, S.E.; Stellman, S.D.; Walker, D.J.; Wu, D.; et al. Asthma and posttraumatic stress symptoms 5 to 6 years following exposure to the World Trade Center terrorist attack. JAMA 2009, 302, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, H.T.; Miller-Archie, S.A.; Cone, J.E.; Morabia, A.; Stellman, S.D. Heart disease among adults exposed to the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center disaster: Results from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Brackbill, R.M.; Stellman, S.D.; Farfel, M.R.; Miller-Archie, S.A.; Friedman, S.; Walker, D.J.; Thorpe, L.E.; Cone, J. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and comorbid asthma and posttraumatic stress disorder following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on World Trade Center in New York City. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 1933–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Archie, S.A.; Jordan, H.T.; Ruff, R.R.; Chamany, S.; Cone, J.E.; Brackbill, R.M.; Kong, J.; Ortega, F.; Stellman, S.D. Posttraumatic stress disorder and new-onset diabetes among adult survivors of the World Trade Center disaster. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weakley, J.; Webber, M.P.; Gustave, J.; Kelly, K.; Cohen, H.W.; Hall, C.B.; Prezant, D.J. Trends in respiratory diagnoses and symptoms of firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: 2005–2010. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Li, D.; Wang, A.; Shen, S.; Ma, Z.; Li, X. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Risk Factors Associated with Severity and Death in COVID-19 Patients. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 6660930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Sauver, J.L.; Lopes, G.S.; Rocca, W.A.; Prasad, K.; Majerus, M.R.; Limper, A.H.; Jacobson, D.J.; Fan, C.; Jacobson, R.M.; Rutten, L.J.; et al. Factors Associated With Severe COVID-19 Infection Among Persons of Different Ages Living in a Defined Midwestern US Population. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 2528–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M.J.; Baldwin, M.R.; Abrams, D.; Jacobson, S.D.; Meyer, B.J.; Balough, E.M.; Aaron, J.G.; Claassen, J.; Rabbani, L.E.; Hastie, J.; et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Yuan, J.M. Predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 and intensive care unit admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public. Health 2020, 65, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeuffer, C.; Le Hyaric, C.; Fabacher, T.; Mootien, J.; Dervieux, B.; Ruch, Y.; Hugerot, A.; Zhu, Y.J.; Pointurier, V.; Clere-Jehl, R.; et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with severe COVID-19: Prospective analysis of 1,045 hospitalised cases in North-Eastern France, March 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Chen, Y.; Sun, C.; Ahmed, M.A.; Bhan, C.; Guo, Z.; Yang, H.; Zuo, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hu, L.; et al. Does Proton Pump Inhibitor Use Lead to a Higher Risk of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection and Progression to Severe Disease? a Meta-analysis. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnov, H.; Patel, K.A.; Knobel, P.; Hsu, H.L.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Just, A.C.; Sade, M.Y. World Trade Center (WTC) Exposures and Cardiometabolic Risk Among WTC Health Program General Responders. Am. J. Public Health 2025, 115, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.; Crowley, G.; Mikhail, M.; Lam, R.; Clementi, E.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Schwartz, T.M.; Liu, M.; Prezant, D.J.; Nolan, A. Metabolic Syndrome Biomarkers of World Trade Center Airway Hyperreactivity: A 16-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, N.L.; Shapiro, M.Z.; Sabra, A.; Dasaro, C.R.; Crane, M.A.; Harrison, D.J.; Luft, B.J.; Moline, J.M.; Udasin, I.G.; Todd, A.C.; et al. Cardiovascular disease in the World Trade Center Health Program General Responder Cohort. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Alper, H.E.; Nguyen, A.M.; Maqsood, J.; Brackbill, R.M. Stroke hospitalizations, posttraumatic stress disorder, and 9/11-related dust exposure: Results from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleven, K.L.; Rosenzvit, C.; Nolan, A.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Kwon, S.; Weiden, M.D.; Skerker, M.; Halpren, A.; Prezant, D.J. Twenty-Year Reflection on the Impact of World Trade Center Exposure on Pulmonary Outcomes in Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) Rescue and Recovery Workers. Lung 2021, 199, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibman, J.; Liu, M.; Cheng, Q.; Liautaud, S.; Rogers, L.; Lau, S.; Berger, K.I.; Goldring, R.M.; Marmor, M.; Fernandez-Beros, M.E.; et al. Characteristics of a residential and working community with diverse exposure to World Trade Center dust, gas, and fumes. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, R.; Ahmadi, A.; Alper, H.; Li, J.; Yu, S. The association of Gastro-esophageal reflux disease and self-reported myocardial-infarction among World Trade Center disaster exposed persons. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 58, 103232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhuillier, E.; Yang, Y.; Morozova, O.; Clouston, S.A.P.; Yang, X.; Waszczuk, M.A.; Carr, M.A.; Luft, B.J. The Impact of World Trade Center Related Medical Conditions on the Severity of COVID-19 Disease and Its Long-Term Sequelae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiden, M.D.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Singh, A.; Schwartz, T.; Liu, Y.; Vaeth, B.; Nolan, A.; Cleven, K.L.; Hurwitz, K.; Beecher, S.; et al. Pre-COVID-19 lung function and other risk factors for severe COVID-19 in first responders. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00610-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfel, M.; DiGrande, L.; Brackbill, R.; Prann, A.; Cone, J.; Friedman, S.; Walker, D.J.; Pezeshki, G.; Thomas, P.; Galea, S.; et al. An overview of 9/11 experiences and respiratory and mental health conditions among World Trade Center Health Registry enrollees. J. Urban Health 2008, 85, 880–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Brackbill, R.M.; Thalji, L.; Dolan, M.; Pulliam, P.; Walker, D.J. Measuring and maximizing coverage in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 1688–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenforde, M.W.; Kim, S.S.; Lindsell, C.J.; Billig Rose, E.; Shapiro, N.I.; Files, D.C.; Gibbs, K.W.; Erickson, H.L.; Steingrub, J.S.; Smithline, H.A.; et al. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network—United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Nalla, L.V.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, N.; Singh, A.A.; Malim, F.M.; Ghatage, M.; Mukarram, M.; Pawar, A.; Parihar, N.; et al. Association of COVID-19 with Comorbidities: An Update. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, L.; Campos Codo, A.; Sampaio, V.S.; Oliveira, A.E.R.; Ferreira, L.K.K.; Davanzo, G.G.; de Brito Monteiro, L.; Victor Virgilio-da-Silva, J.; Borba, M.G.S.; Fabiano de Souza, G.; et al. Acid pH Increases SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of Death by COVID-19. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 637885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azofeifa, A.; Martin, G.R.; Santiago-Colon, A.; Reissman, D.B.; Howard, J. World Trade Center Health Program—United States, 2012–2020. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2021, 70, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tsampasian, V.; Elghazaly, H.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Debski, M.; Naing, T.K.P.; Garg, P.; Clark, A.; Ntatsaki, E.; Vassiliou, V.S. Risk Factors Associated With Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Burdens of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 by severity of acute infection, demographics and health status. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.