The Relationship Between Well-Being and MountainTherapy in Practitioners of Mental Health Departments

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Work-Related Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Services

1.2. Theoretical Models and Psychological Well-Being in the Work Context

1.3. Environmental and MountainTherapy Activities

1.4. Aims of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sampling

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Questionnaires

2.3.1. General Health Questionnaire [GHQ-12], Italian Version

2.3.2. Maslach Burnout Inventory [MBI], Italian Version

2.3.3. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale [UWES-9], Italian Version

2.3.4. Resilience Scale [RS-14], Italian Version

2.3.5. Edmondson’s Team Psychological Safety Scale [57]

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

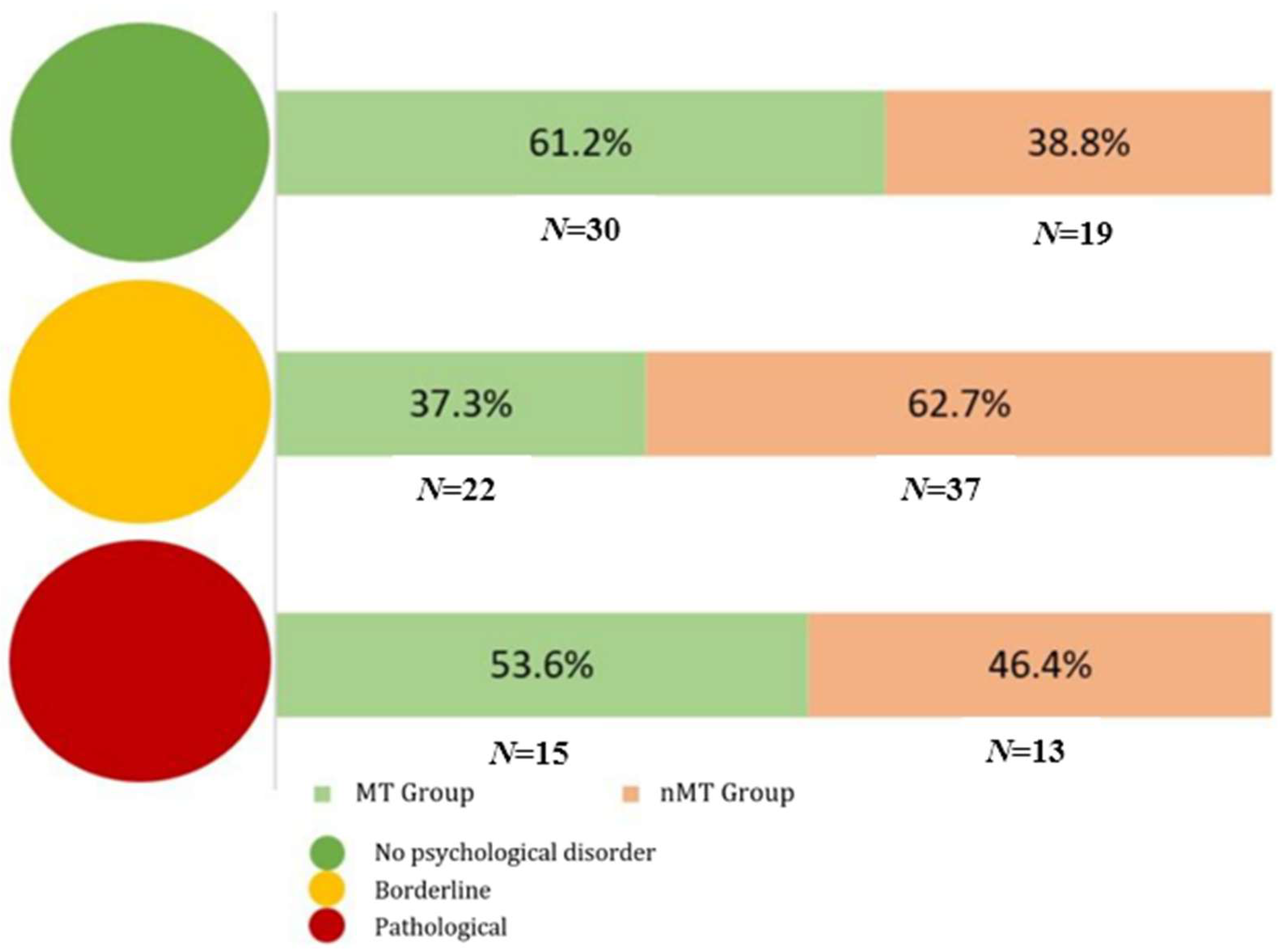

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations and Future Projections

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MTA | MountainTherapy activities |

| MT | MountainTherapy |

| nMT | no MountainTherapy |

| GHQ-12 | General Health Questionnaire |

| MBI | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| UWES-9 | Utrecht Work Engagement Scale |

References

- Cooper, C.L.; Payne, R. Causes, Coping, and Consequences of Stress at Work; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-471-91879-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.; Griffiths, A.; Rial-González, E. Research on Work-Related Stress; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg; Bernan Associates [Distributor]: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-92-828-9255-8. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R. Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. Health Work; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, J.; Peter, R.; Cremer, P.; Seidel, D. Chronic Work Stress Is Associated with Atherogenic Lipids and Elevated Fibrinogen in Middle-aged Men. J. Intern. Med. 1997, 242, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.; Griffiths, A.J. The Assessment of Psychosocial Hazards at Work. Handb. Work Health Psychol. 1996, 127, 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Sarafis, P.; Rousaki, E.; Tsounis, A.; Malliarou, M.; Lahana, L.; Bamidis, P.; Niakas, D.; Papastavrou, E. The Impact of Occupational Stress on Nurses’ Caring Behaviors and Their Health Related Quality of Life. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaghar, M.I.; Masrour, M.J. A Comparative Study of Satisfaction and Family Conflicts among Married Nurses with Different Working Hours. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkic, K.; Landsbergis, P.A.; Schnall, P.L.; Baker, D. Is Job Strain a Major Source of Cardiovascular Disease Risk? Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2004, 30, 85–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.L. Working Hours and Health. Work Stress 1996, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, A.H.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Houtman, I.L.D.; Bongers, P.M. “The Very Best of the Millennium”: Longitudinal Research and the Demand-Control-(Support) Model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S. Job Stress and Cardiovascular Disease: A Theoretic Critical Review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Florian, V. Burnout, Job Setting, and Self-Evaluation among Rehabilitation Counselors. Rehabil. Psychol. 1988, 33, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, R.; Crea, G.; Laghi, F.; Provenzano, L. Il Rischio Psicosociale Nelle Professioni Di Aiuto. La Sindrome Del Burnout Nei Religiosi, Operatori Sociali, Medici, Infermieri, Fisioterapisti, Psicologi e Psicoterapeuti; Erickson: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia, R.; Vannucci, A. (Eds.) Prevenire Gli Eventi Avversi Nella Pratica Clinica; Springer Milan: Milano, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-88-470-5449-3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/world-mental-health-report (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Parent-Thirion, A.; Fernández Macías, E.; Hurley, J.; Vermeylen Fourth, G. European Working Conditions Survey. Eur. Found. Improv. Living Work. Cond. Pozyskano Z. Www Eurofound Eur. Eu. 2007. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/system/files/2015-11/6ewcs_first_findings_-_eurofound.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, T.P. Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth-Cozens, J. Interventions to Improve Physicians’ Well-Being and Patient Care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tummers, G.E.R.; Landeweerd, J.A.; Van Merode, G.G. Work Organization, Work Characteristics, and Their Psychological Effects on Nurses in the Netherlands. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2002, 9, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodilupo, A.; Colucci, M. Stress Infermieristico in Strutture Sanitarie Intermedie: Studio Osservazionale e Ipotesi Di Intervento. Riv. L’Infermiere 2023, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado, M.D.M.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Linares, J.J.G.G.; Márquez, M.D.M.S.; Martínez, Á.M. Burnout Risk and Protection Factors in Certified Nursing Aides. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas-Hernández, L.; Ariza, T.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Albendín-García, L.; De la Fuente, E.I.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Prevalence of Burnout in Paediatric Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V. The Impact of Workplace Social Support, Job Demand and Work Control Upon Cardiovascular Disease in Sweden; University of Stockholm: Stockholm, Sweden, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Avallone, F.; Bonaretti, M. Benessere Organizzativo. Per Migliorare La Qualità Del Lavoro Nelle Amministrazioni Pubbliche; Rubbettino Editore: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, P.; Mavros, P.; Coyne, R.; Roe, J. The Urban Brain: Analysing Outdoor Physical Activity with Mobile EEG. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolouki, A. Neurobiological Effects of Urban Built and Natural Environment on Mental Health: Systematic Review. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 38, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-W.; Jeong, G.-W.; Kim, T.-H.; Baek, H.-S.; Oh, S.-K.; Kang, H.-K.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, Y.S.; Song, J.-K. Functional Neuroanatomy Associated with Natural and Urban Scenic Views in the Human Brain: 3.0T Functional MR Imaging. Korean J. Radiol. 2010, 11, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, S.; Neale, C.; Patuano, A.; Cinderby, S. Older People’s Experiences of Mobility and Mood in an Urban Environment: A Mixed Methods Approach Using Electroencephalography (EEG) and Interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-barrak, L.; Kanjo, E.; Younis, E.M.G. NeuroPlace: Categorizing Urban Places According to Mental States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudimac, S.; Sale, V.; Kühn, S. How Nature Nurtures: Amygdala Activity Decreases as the Result of a One-Hour Walk in Nature. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4446–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, R.; Johnson, K.; Lee, K.; Williams, K. Comparing the Effect of Mindful and Other Engagement Interventions in Nature on Attention Restoration, Nature Connection, and Mood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Process: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling 2012. Available online: https://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Joschko, L.; Palsdottir, A.M.; Grahn, P.; Hinse, M. Nature-Based Therapy in Individuals with Mental Health Disorders, with a Focus on Mental Well-Being and Connectedness to Nature—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoppola, G. Montagnaterapia-SAT—Sezione Di Riva Del Garda. Available online: https://www.satrivadelgarda.it/0/montagnaterapia/2/1943/page.aspx (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Niedermeier, M.; Hösl, B.; Frühauf, A.; Kopp, M. Mountain Sport Activities, Affective State, and Mental Health–A Narrative Review. Curr. Issues Sport Sci. 2024, 9, 046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, C.F.; Frecchiami, A.; Delle Fave, A. Interventi Riabilitativi Ed Esperienza Ottimale Nel Contesto Montano. Psichiatr.Comunita 2011, 10, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor, D.A.; Hopker, S.W. The Effectiveness of Exercise as an Intervention in the Management of Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Br. Med. J. 2001, 322, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tari, A.R.; Walker, T.L.; Huuha, A.M.; Sando, S.B.; Wisloff, U. Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Exercise and the Importance of Fitness for Healthy Brain Ageing. Lancet 2025, 405, 1093–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuechterlein, K.H.; Ventura, J.; McEwen, S.C.; Gretchen-Doorly, D.; Vinogradov, S.; Subotnik, K.L. Enhancing Cognitive Training through Aerobic Exercise after a First Schizophrenia Episode: Theoretical Conception and Pilot Study. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, S44–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, V.F.; De Toma, N.G.; Tulli, P.; Bacigalupi, M.; Bardanzellu, V.; Le, B. Nuovi Strumenti per La Salute Mentale. Psichiatr. Comunità 2006, 5, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser, K.T.; Bellack, A.S.; Gingerich, S.; Agresta, J.; Fulford, D. Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, K. Nurtured by Nature. Monit. Psychol. 2020, 51, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, D. GHQ and Psychiatric Case. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli, M.; Politi, P. Struttura Fattoriale Della Versione a 12 Domande Del General Health Questionnaire in Un Campione Di Giovani Maschi Adulti. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 1993, 2, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Perez, J.M.L.; D’Antonio, A.C.; Perez, F.J.F.; Arcangeli, G.; Cupelli, V.; Mucci, N. The General Health Questionaire (GHQ-12) in a Sample of Italian Workers: Mental Health at Individual and Organizational Level. World J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirigatti, S.; Stefanile, C. MBI. Maslach Burnout Inventory; Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 1993. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9): A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G. A Review of the Resilience Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 2009, 17, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, C.; Bertù, L.; Lucano, M.; Ielmini, M.; Braggio, E.; Vender, S. Reliability and Validity of the Italian Version of the 14-Item Resilience Scale. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2016, 9, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.; Brivio, F.; Fagnani, L.; Capelli, R.; Stringo, J.; Aprosio, S.; Riva, P.; Greco, A. Psychometric Validation of the Italian Version of Edmondson’s Psychological Safety Scale in the Organizational Context. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the European Health Psychology Society (EHPS 2021)-Book of Abstracts, Online, 23–27 August 2021; Easy Conferences. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural Equation Models with Nonnormal Variables: Problems and Remedies; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Djernis, D.; Lerstrup, I.; Poulsen, D.; Stigsdotter, U.; Dahlgaard, J.; O’Toole, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nature-Based Mindfulness: Effects of Moving Mindfulness Training into an Outdoor Natural Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why Is Nature Beneficial?: The Role of Connectedness to Nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What Is the Best Dose of Nature and Green Exercise for Improving Mental Health? A Multi-Study Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brega, A.; Carpineta, S.; Cossu, E.; Benedetto, P.D.; Frugoni, E.; Galiazzo, M.; Lanfranchi, F.; Piergentili, P. Montagnaterapia; Erickson Direct Publishing: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tabolli, S.; Ianni, A.; Renzi, C.; Di Pietro, C.; Puddu, P. Soddisfazione Lavorativa, Burnout e Stress Del Personale Infermieristico: Indagine in Due Ospedali Di Roma. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2006, 28, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. OCS Organizational Checkup System: Come Prevenire Il Burnout e Costruire l’impegno: Guida per Il Capo Progetto; Organizzazioni Speciali, University of Turin: Turin, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Weinstein, N.; Bernstein, J.; Brown, K.W.; Mistretta, L.; Gagné, M. Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MT Group (n = 83; 49.7%) | nMT Group (n = 84; 50.3%) | χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | (χ2(39) = 39.88, p = 0.431) | ||||

| mean (SD) | 44.65 (11.32) | 47.10 (9.86) | |||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Gender | (χ2(3) = 1.42, p = 0.701) | ||||

| male | 14 | 21.2 | 16 | 24.6 | |

| female | 49 | 74.2 | 46 | 70.8 | |

| prefer not to answer | 3 | 4.5 | 2 | 3.1 | |

| other | / | / | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Geographical location | (χ2(3) = 1.798, p = 0.615) | ||||

| north-east | 42 | 50.6 | 40 | 47.6 | |

| north-west | 19 | 22.9 | 26 | 40.0 | |

| center | 14 | 16.9 | 10 | 11.9 | |

| south | 8 | 9.6 | 8 | 9.5 | |

| islands | / | / | / | / | |

| Referral Service | |||||

| outpatient | 20 | 32.3 | 28 | 45.9 | |

| residential | 18 | 29.0 | 13 | 21.3 | |

| semi-residential | 24 | 38.7 | 20 | 32.8 | |

| Years of employment | (χ2(3) = 3.13, p = 0.373) | ||||

| less than 5 years | 23 | 34.8 | 15 | 23.1 | |

| 5 to 10 years | 7 | 10.6 | 12 | 18.5 | |

| 10 to 20 years | 14 | 21.2 | 16 | 24.6 | |

| more than 20 years | 22 | 33.3 | 22 | 33.8 | |

| Team role | (χ2(6) = 1.87, p = 0.931) | ||||

| social worker | 2 | 3.0 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| physician | 3 | 4.5 | 2 | 3.1 | |

| health and social worker (OSS) | 4 | 6.1 | 5 | 7.7 | |

| psychiatric rehabilitation | 7 | 10.6 | 5 | 7.7 | |

| therapist | |||||

| psychologist | 11 | 16.7 | 8 | 12.3 | |

| nurse | 18 | 27.3 | 22 | 33.8 | |

| professional educator | 21 | 31.8 | 22 | 33.8 | |

| MT practice length | / | / | |||

| less than 1 year | 8 | 12.1 | |||

| 1 to 3 years | 22 | 33.3 | |||

| 3 to 5 years | 14 | 21.2 | |||

| 5 to 10 years | 8 | 12.1 | |||

| more than 10 years | 14 | 21.2 | |||

| MT practice attendance | / | / | |||

| 1 time per week | 5 | 7.7 | |||

| 1 time every 2 weeks | 12 | 18.5 | |||

| 1 time per month | 47 | 72.3 | |||

| participation in visits | 1 | 1.5 | |||

| M (SD) | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT Group | nMT Group | |||||

| GHQ-12 (Psychological distress) | ||||||

| total score | 15.06 (6.31) | 16.67 (4.38) | −1.721 | 117.282 | 0.044 | −0.297 |

| general dysphoria | 9.04 (4.50) | 10.20 (3.11) | −1.741 | 116.955 | 0.042 | −0.300 |

| social functioning | 6.01 (2.43) | 6.46 (1.92) | −1.195 | 134 | 0.117 | −0.205 |

| MBI (Burnout) | ||||||

| emotional exhaustion | 2.62 (1.12) | 2.63 (0.86) | −0.117 | 127.295 | 0.454 | −0.020 |

| depersonalization | 1.66 (0.74) | 1.73 (0.72) | −0.578 | 137 | 0.282 | −0.098 |

| personal accomplishment | 4.91 (0.67) | 4.74 (0.79) | 1.374 | 137 | 0.086 | 0.233 |

| UWES-9 (Job engagement) | ||||||

| vigor | 3.51 (0.66) | 3.36 (0.61) | 1.343 | 133 | 0.091 | 0.231 |

| devotion | 4.06 (0.77) | 3.98 (0.76) | 0.633 | 133 | 0.264 | 0.109 |

| emotional involvement | 3.23 (0.60) | 3.15 (0.64) | 0.785 | 133 | 0.217 | 0.135 |

| RS-14 (Resilience) | 76.72 (13.86) | 77.12 (13.30) | −0.172 | 133 | 0.432 | |

| Edmondson’s Scale (Psychological Safety) | ||||||

| general | 5.00 (1.19) | 5.01 (1.06) | −0.044 | 132 | 0.483 | −0.007 |

| self-expression | 5.35 (1.09) | 5.20 (1.00) | 0.800 | 132 | 0.212 | 0.134 |

| M (SD) | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT Group More than Once a Month | MT Group Less than Once a Month | |||||

| GHQ-12 (Psychological distress) | ||||||

| total score | 12.71 (6.56) | 15.96 (5.80) | 1.921 | 63 | 0.030 | 6.00 |

| general dysphoria | 7.18 (4.84) | 9.77 (4.10) | 2.139 | 63 | 0.272 | 4.30 |

| social functioning | 5.53 (2.35) | 6.19 (2.38) | 0.984 | 63 | 0.164 | 2.37 |

| MBI (Burnout) | ||||||

| emotional exhaustion | 2.39 (1.23) | 2.67 (1.09) | 0.886 | 63 | 0.190 | 1.12 |

| depersonalization | 1.31 (0.40) | 1.73 (0.77) | 2.857 | 54.107 | 0.003 | 0.70 |

| personal accomplishment | 5.00 (0.63) | 4.89 (0.67) | −0.610 | 63 | 0.267 | 0.66 |

| UWES-9 (Job engagement) | ||||||

| vigor | 3.80 (0.74) | 3.39 (0.61) | −2.276 | 63 | 0.013 | 0.65 |

| devotion | 4.20 (0.83) | 3.99 (0.74) | −0.954 | 63 | 0.175 | 0.77 |

| emotional involvement | 3.22 (0.78) | 3.24 (0.55) | 0.137 | 63 | 0.446 | 0.62 |

| RS-14 (Resilience) | 82.29 (11.735) | 75.83 (12.309) | −1.882 | 63 | 0.032 | 12.17 |

| Edmondson’s Scale (Psychological Safety) | ||||||

| general | 5.18 (1.04) | 4.93 (1.25) | −0.714 | 63 | 0.239 | 1.20 |

| self-expression | 5.18 (1.26) | 5.38 (1.03) | 0.634 | 63 | 0.264 | 1.10 |

| M (SD) | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT Group During MT Activities | MT Group During Other Work Activities | |||||

| UWES-9 (Job engagement) | ||||||

| vigor | 5.88 (0.93) | 3.50 (0.66) | −8.322 | 66 | <0.001 | 0.86 |

| devotion | 6.26 (0.90) | 4.06 (0.77) | −4.500 | 66 | <0.001 | 0.88 |

| emotional involvement | 5.62 (1.06) | 3.23 (0.60) | −8.322 | 66 | 0.002 | 1.01 |

| Edmondson’s Scale (Psychological Safety) | ||||||

| general | 4.20 (0.61) | 5.01 (1.19) | −5.819 | 66 | <0.001 | 1.16 |

| self-expression | 4.35 (0.58) | 5.35 (1.09) | −5.609 | 66 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lanfranchi, F.; Zambetti, E.; Bigoni, A.; Brivio, F.; Di Natale, C.; Martini, V.; Greco, A. The Relationship Between Well-Being and MountainTherapy in Practitioners of Mental Health Departments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081181

Lanfranchi F, Zambetti E, Bigoni A, Brivio F, Di Natale C, Martini V, Greco A. The Relationship Between Well-Being and MountainTherapy in Practitioners of Mental Health Departments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081181

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanfranchi, Fiorella, Elisa Zambetti, Alessandra Bigoni, Francesca Brivio, Chiara Di Natale, Valeria Martini, and Andrea Greco. 2025. "The Relationship Between Well-Being and MountainTherapy in Practitioners of Mental Health Departments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081181

APA StyleLanfranchi, F., Zambetti, E., Bigoni, A., Brivio, F., Di Natale, C., Martini, V., & Greco, A. (2025). The Relationship Between Well-Being and MountainTherapy in Practitioners of Mental Health Departments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081181