Abstract

The Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project (PRP) is a tool designed to structure and organize mental health care, guided by the theoretical and practical principles of Psychosocial Rehabilitation (PR). This article aims to identify the initial requirements for the prototyping of a “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”. To achieve this, an integrative review was conducted with the research question: what initial requirements are important to compose the prototype of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App” in mental health? In the search process, 834 articles were identified and exported to the online systematic review application Rayyan QCRI, resulting in 36 eligible articles for this study, along with one app. The reading of this material allowed the elicitation of three themes: privacy and data protection policy; design; and software and programming. The prototyping of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App” should prioritize data security and protection, simplicity in design, and the integration of technological resources that facilitate the management, construction, monitoring, and evaluation of psychosocial rehabilitation projects by mental health professionals.

1. Introduction

The Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project (PRP) is a tool that structures and organizes mental health care guided by the theoretical and practical precepts of psychosocial rehabilitation (PR). It also allows building and/or rescuing the contractuality of the psychiatric patient so that they can manage their life with autonomy, desires, values, and purposes, achieving social protagonism [1,2,3].

The literature shows that these projects, when performed on paper, are bureaucratic, fragmented, decontextualized from the psychosocial needs of the psychiatric patient, and difficult to operationalize in mental health services [4,5]. In this sense, one way to dynamize them would be to adapt them to a mobile mHealth support technology, as this resource allows streamlining traditional processes in mental health [6,7,8], promoting the exercise of human rights, citizenship, accessibility to care, and mental health services, which can reduce inequalities and social injustices [9].

Therefore, it is necessary to develop digital tools, such as mental health apps to be used by mental health professionals to support the psychosocial rehabilitation of people with severe and persistent mental disorders, seeking to promote social inclusion, the construction of autonomy, social functionality, and the exercise of citizenship in this population [10].

However, there are few apps developed for psychosocial rehabilitation, and those that exist are focused on supporting the patient through gamification [10,11].

Thus, it is necessary to develop mental health apps contextualized and adapted to the work environment and the ”real” needs regarding mental health care provided by mental health professionals [12], especially considering the context of psychosocial rehabilitation and the difficulties of the psychosocial care network inserted in the Brazilian public health system (SUS) [2,4,5,13,14].

Considering this reality and the existing gap regarding the development of apps that favor the planning of psychosocial rehabilitation by health professionals [3,11], it is essential to develop scientific investigations on this topic. The literature shows that even though there is no standard for the development of a mental health app [15,16,17,18,19], there are common steps as follows: An exploratory and descriptive literature review for researchers or developers to know the state-of-the-art about apps, identify similar apps and resources to support their idea, and gather initial prototyping requirements. Co-design or consultations with mental health professionals to contextualize the requirements of the review or to know specific requirements. The development and validations (technical, content, appearance, and usability) [4,14,15,16,17,18,19].

By following the requirements for prototyping, it is possible to develop mental health apps through the creative process, such as the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”. Prototyping allows the principal researcher to actively participate in the app’s visual design, functionality, and content, ensuring it aligns with its therapeutic purposes. This process is based on theoretical foundations that justify its therapeutic approach and is aligned with the prototyping requirements gathered from the literature review [15,20,21,22,23,24,25], content and appearance validation [23,24,26], and usability [16,27,28,29].

Thus, this article aims to identify initial requirements for the prototyping of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”.

2. Materials and Methods

An exploratory, descriptive, and integrative literature review study was conducted, as adapted from PRISMA guidelines, following research stages [30,31,32,33]: Firstly, composition of the research question based on the PICo strategy. Secondly, definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thirdly, selection of health sciences descriptors (DeCS) and medical subject headings (MeSH) and their respective synonyms. Fourthly, composition of the electronic search expression and its insertion into national and international databases. Finally, synthesis of the selected references.

The research question was constructed using the PICo strategy, where P is the population/research condition, I is the intervention, and Co is the context [31]. Based on this reference, the following research question was delimited: what initial requirements are important to compose the prototype of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App” in mental health? It should be noted that P is “initial requirements”, I is “compose the prototype of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”, and Co is “mental health”.

Considering this information, the controlled descriptors indexed in DeCS and MeSH were established, with their respective synonyms in Portuguese, English, and Spanish, and combined with Boolean operators (AND and OR) to construct the electronic search expression completed with their synonyms. The short form can be seen below, and the complete form in Table 1 [31]. P (“Design de Software” OR “Software Design” OR “Diseño de Software” OR “Projeto de Sistemas” OR “System Design” OR “Diseño de Sistemas” OR “Software” OR “Software” OR “Programas Informáticos”) AND I (“Aplicativos Móveis” OR “Mobile Applications” OR “Aplicaciones Móviles” AND “Projetos” OR “Projects” OR “Proyectos” AND “Psychiatric Rehabilitation” OR “Psychiatric Rehabilitation” OR “Rehabilitación Psiquiátrica”) AND Co (“Mental Health” OR “Mental Health” OR “Salud Mental”).

Table 1.

Description of the search expression, based on the indexed descriptors and their respective synonyms combined using the Boolean operators.

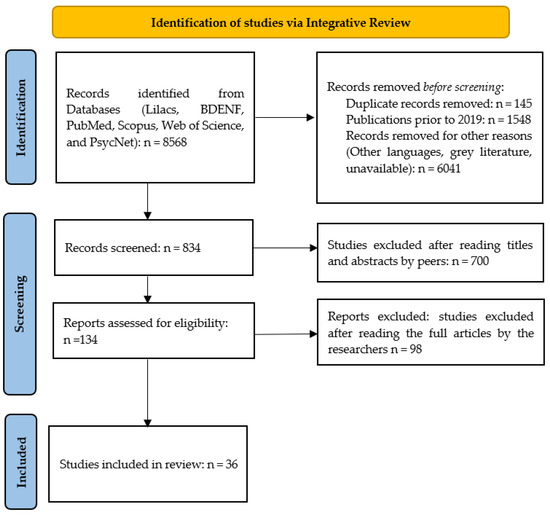

This complete electronic expression, Table 1, was inserted on 12 August 2023, into the databases of the Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (Lilacs), Nursing Database (BDENF), International Literature in Health Sciences (PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycNet via remote access through the Federated Academic Community (CAFe) on the Portal of Periodicals of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), searching by title, abstract, and keywords/DeCS/MeSH. For this purpose, complete articles published in Portuguese, English, and Spanish were included, published in the period between 2019 and 2023, corresponding to 5 years. Duplicate articles and those that did not meet the research question (eligibility) were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps flowchart for selection of articles for this integrative literature review. Source: prepared by the author (2024).

Concurrently, the 834 articles were exported to the online systematic review application Rayyan QCRI for double-blind peer review based on titles and abstracts. As there were no conflicts among the reviewers, submission to a third evaluator was not necessary [34,35]. After reading the titles and abstracts of the 834 articles with the aid of Rayyan QCRI, 700 articles were excluded for not meeting the defined eligibility criteria, resulting in 134 articles. After a thorough full-text review, 98 articles were excluded, leaving 36 articles for inclusion in this study. These articles were re-read and synthesized to address the research question and objectives of this work (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected articles for the integrative review.

To complement the integrative literature review and gain a better understanding of technological products (apps) related to psychosocial rehabilitation apps, a search was conducted during the same period as the review (between 2019 and 2023) in Google Patents (N = 0), Espacenet (N = 1), Latipat-Espacenet (N = 0), Patentscope (N = 0), Play Store (N = 3), App Store (N = 0), and the Brazilian National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) (N = 0). The following keywords were used in Portuguese, English, and Spanish: Projects, Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health and Apps/ Projects, Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, and App/ Proyectos, Rehabilitación Psicosocial y Salud Mental y Aplicaciones. An advanced search was conducted by title and/or abstract and/or full text words, when available. As inclusion criteria, titles and/or abstracts of patents/apps that described a relationship with the development of “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Projects Apps” were included, and as exclusion criteria, patents/apps that did not meet the eligibility criteria and were written in languages other than Portuguese, English, and Spanish were excluded.

This research resulted in 1 patent and 6 apps, which, after applying the exclusion and eligibility criteria [66,67], resulted in 3 mental health apps. After installing the apps on personal smartphones (of two researchers) to learn about their features, the patent was read and excluded because it did not have an available app and there were no details available due to copyright restrictions. Two apps were also excluded due to interface defects that prevented the evaluation of their functionalities. Therefore, only 1 mental health app was included (Table 3), which was analyzed in terms of its functions and technological resources [47].

Table 3.

Selected applications for the search, app, and description platform.

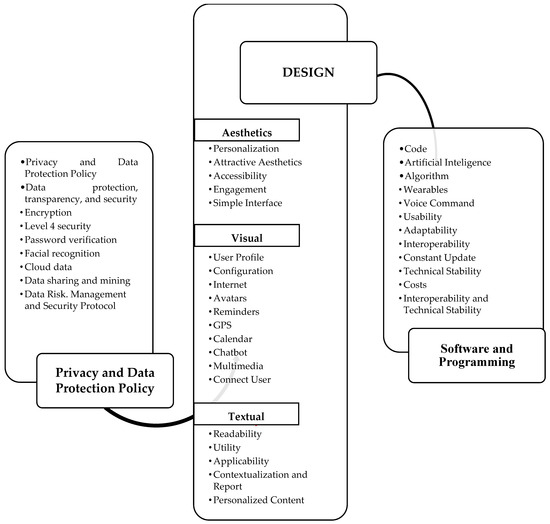

Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006, 2022, 2023) six-phase approach to thematic analysis, we analyzed the articles and the app. Initially, we immersed ourselves in the data (phase 1), thoroughly reading and rereading the materials to gain a comprehensive understanding. This familiarization process led to the generation of initial codes (phase 2) related to functions, technological resources, and recommendations. These codes were then systematically grouped into potential themes and subthemes (phase 3), reflecting recurring patterns and significant meanings within the data. We then rigorously reviewed and refined these candidate themes (phase 4), ensuring they accurately represented the data and captured the nuances of the coded segments. This iterative process involved revisiting the data and codes to ensure coherence and comprehensiveness. Subsequently, we clearly defined and named the final themes and subthemes (phase 5), providing concise labels that encapsulated the essence of each. To enhance the trustworthiness and validity of our findings, a second researcher independently reviewed the identified themes and codes (phase 4), a process informed by best practices in collaborative thematic analysis. This independent verification helped to mitigate potential researcher bias and strengthened the rigor of our analysis [47]. Figure 2 presents the resulting themes, subthemes, and illustrative codes. This figure provides a clear and transparent overview of our analytical process and findings. It was created to visually encapsulate the structured approach and key themes identified, making the data more accessible and understandable. Guided by Braun and Clarke’s framework, this structured approach allowed us to systematically analyze the data and develop a rich understanding of the key themes present.

Figure 2.

Presents the possible composition of the prototype “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”. Source: Prepared by the authors, 2024 (see Figure S1).

3. Results

Presented below are the themes and corresponding codes that refer to initial requirements to compose the prototyping of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”.

4. Discussion

For the prototyping of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App” it is imperative that researchers pay attention to the simplicity of its design [44,60], as a simple appearance and simple functionalities do not make it unviable and do not prevent its personalization. Personalization (background, themes, and colors) of an app allows the user to feel represented by and belonging to this app in a way that addresses diversities and gender representation and makes them feel included from its prototyping to its availability for download [40,42,49]. To make it attractive, there must be a configuration menu so that the user can edit profile information, choose avatars or photos, and make adjustments related to necessary functionality/update notifications [24,40,45,51]. Personalization should be planned and designed in advance in the app’s design.

The design needs to be user-centered and have content and technological resources that unfold into images, icons, and texts [46,56], buttons, and menus that meet their functionality and are based on theoretical support and/or scientific evidence [12,40,46], with the inclusion of colorful icons and appropriate screen sizes, a pleasant modern aesthetic, and needs to avoid cognitive overload [25,35,46,54,56].

Another important requirement is interactivity and ease of use [64], which favors effective participation and testing by the target audience [55]. Furthermore, it is essential that mental health apps have accessibility, which is expressed through the inclusion of diversities and human particularities, being a factor that influences engagement [41,43,49], which represents the user’s involvement in using a mental health app and performing their tasks/actions [58]. In this way, accessibility should be valued, since, in most cases, mental health apps have a barrier to their effectiveness in the real world due to a lack of involvement with the user because they are decontextualized from their reality [38].

However, research has shown that the prototype or development of a mental health app with all the technological resources currently available to researchers and developers tends to generate difficulties in its use among its users [24,38,60]. Among the technological resources indicated, the following stand out: internet access, which is the main source of research on health/mental health information for professionals and users [40,46,68]; mental health care reminders [24,49,52]; calendars with dates and management of schedules and appointments [55]; GPS to locate mental health services [12,35]; a chatbot, an automatic robot for interaction with users with pre-programmed prompts [61]; multimedia [24,53,56]; personalized feedback through prompts, which allow for rapid intervention; reports for the composition of metrics, and refined or raw data about their activities [42]; a resource for connecting with a therapist (through video calls, chat, and other media resources) [39,45]; gamification [10]; artificial intelligence [39,45,69] with the help of voice commands and multimedia (sound captures); and wearables that allow learning about human behavior [52] through the algorithm [39,45,48,50,69].

The stage at which researchers and developers choose the technological resources to be used in mental health apps is prototyping, and at this moment, the app’s design is improved and sketched, and subsequently, development proceeds, focusing on programming to activate the mental health app, enabling its interoperability, usability [53], and choice of operating system [56,70]. At this stage, it is also defined whether the code used will be open or not [36,53]. The programming of mental health apps requires special attention to adaptability and interoperability. Adaptability allows the app to be modified to meet the constantly evolving needs of users. Interoperability, in turn, ensures that the app can share data with other health systems, facilitating integration and access to relevant information. These characteristics are fundamental to ensuring the usability of the app and its ability to prevent technical problems, as pointed out by [25,58].

Regarding data security and privacy, the literature suggests a scarcity of scientific research on the full understanding of the risks and threats to data security and privacy in mental health apps. The main threats to privacy in these apps concern likability, identifiability, non-repudiation, detectability, information disclosure, unawareness, and non-compliance [71].

Studies [72,73,74,75] focus on privacy policies, others on a more bioethical approach [76,77] or specifically on data sharing [78], or recommendations for mental health app evaluation [79]. One study alerted us to the need for mental health apps to have clear policies on infrastructure, processing, storage, and the sharing of data [80].

Data privacy and security are also a barrier to the usability of mental health apps [50,81], requiring developers and researchers to implement security and risk management measures and strategies, and through interventions for cases of privacy invasion through data leakage [41,82]. Measures such as encryption [51], logout after five minutes of continuous non-use of the app by its user, password protection and password verification by email, smartphones, and/or facial or digital detection [38,45] can prevent privacy violations and data theft [6,35,44,55,56,76,77].

Often, the large amount of data produced by mental health apps is stored in the cloud [56] to reduce the memory load on the user’s smartphone and also ensure that data are not lost [40]. Generally, cloud services contracted from trusted companies are encrypted, but by outsourcing, the risk of data invasion increases, and control is lost by the app owners and the users themselves [76].

The study also warns that cloud infrastructure services, such as storage on Firebase, which guarantee the functionality of apps in an “easy” way for developers, limit the control over the data, and the process may not be transparent [80]. It is recommended that developers build a well-structured flow for the transmission, sharing, and storage of data, making them aware that mental health apps are potentially risky systems regarding data privacy and security, consulting lawyers when developing the security and privacy policy, knowing the policies and laws related to data privacy in their respective countries, collecting valid user consent, and receiving advice from professionals specialized in data security and privacy in relation to mental health apps [80].

Data mining has been used with the support of artificial intelligence to use data for mental health intervention, make diagnoses, and prevention, which is still a little-explored field and has been justified as a way to ensure quality in different aspects involving information, such as assessment, diagnoses, evolutions, records, and images produced in health [45,53].

The access to the internet through health applications faces the issue of data confidentiality [76,77,83]. This problem worsens when it comes to data produced in the field of mental health, which are sensitive and generally used as criteria for diagnosing mental disorders and their comorbidities [77]. In the prototype of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”, researchers and developers intend to build a data protection and security policy with the assistance of a professional lawyer to address the ethical standards and conditions of use of the app. For this purpose, the authors’ recommendations will be used [77,79]. The concept of Netiquette—a virtual behavior protocol, similar to rules of conduct socially defined in the real world, with the objective of fostering a healthy, dynamic, and fluid coexistence on the internet, respecting people’s rights—will be encouraged among users by the data protection and security policy [84]. Users will be strongly discouraged from sharing patient data (without their authorization) with third parties, under penalty of copyright infringement, guaranteed by the app’s responsible parties, the exclusion of the profile, communication to professional councils, and police and judicial authorities for due action [6,76,77].

Thus, the prototype of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”, as an idealized product, emerges anchored in the theory of psychosocial rehabilitation and the structure of the psychosocial rehabilitation project [1,2,3,85]. In developing this research it was found that there is no app in the consulted databases on mental health with the purpose of facilitating the management, construction, monitoring, and evaluation of psychosocial rehabilitation projects by mental health professionals.

In this sense, the prototyping of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App’” will be based on graphic design methodology, which allows researchers/developers to use subjective aspects, such as intuitiveness and professional experience, during the creative process of developing technological products [22,86,87]. The entire construction of the prototype will take place in the Marvel software [88], with the creative process guided by the pursuit of simplicity [60], translation, and dialog between technology and mental health [1]. This approach aims to balance its functionality with the design oriented by the artistic process of the researchers/developers [7,22].

Although this is both an opportunity for transformation and improvement in mental health care, it is also a great challenge, as there is an immense amount of technological resources that can be integrated into the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”, whether substantially in prototyping, and later, in development, requiring researchers and developers to make assertive choices that result in an easy-to-use app with moderate to high usability [24,38] that guarantees data security without violating human rights [38,55,76,89].

Directions Futures

The next steps are aimed at developing the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”, based on the PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) framework [1]. The user population will consist of mental health professionals (e.g., psychiatric nurses, doctors, psychologists, therapists, etc.). The concept is the psychosocial rehabilitation project: a systematic care instrument based on the theory of psychosocial rehabilitation, defined with phases: assessment, goals, interventions, and agreements. The context will be the CAPS service (psychosocial rehabilitation care environment). To this end, a focus group will be conducted with the CAPS team to define the prototyping requirements contextualized to the work environment of these professionals, to be integrated into the design of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”. Through the creative process and leap of the principal researcher, using the Marvel prototyping tool [22,88], this creative process will always be guided by the theoretical support of psychosocial rehabilitation and the structure defined in the literature of the psychosocial rehabilitation project [2,3,85], as can be seen in Table 4 below, which allows capturing the requirements defined in Figure 2, the findings of the present research which has been selected and adapted according to the process and creative leap, and in accordance with the structure of the psychosocial rehabilitation project [2,3,7,22,86,87]. In addition, the next research steps will use health professionals’ consultancy through prototype validation [16,23,24,90,91,92,93]. Finally, for the authors, the creative leap allows for changes, as the researchers’ creativity and other emerging senses can add changes and innovation to make the prototype of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App” coherent, adequate, and functional without compromising its future development and usability [22,24,56].

Table 4.

Initial requirements for the prototyping of the psychosocial rehabilitation project app.

5. Conclusions

The prototyping of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App” should prioritize data security and protection, simplicity in design, and the integration of technological resources that facilitate the management, construction, monitoring, and evaluation of psychosocial rehabilitation projects by mental health professionals. The integrative review conducted in this work identified three main themes: privacy and data protection policy; design; and software and programming. These themes are crucial to ensure that the application meets the needs of mental health professionals and patients, making it important and justified to reflect on these themes before prototyping, which become initial prototyping requirements. The review provided a list of many technological resources and recommendations regarding data privacy, requiring researchers to reflect on their feasibility, so that their choices are aligned with the creative process and functionality of the “Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project App”, always guided by the psychosocial rehabilitation project structure.

Finally, a limitation of this study is the lack of practical validation of the identified requirements, which suggests the need for future studies to test and validate the effectiveness of the prototype in real-use contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22020310/s1, Figure S1: “APP PROJETO DE REABILITAÇÃO PSICOSSOCIAL” (2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.A.C.C., M.F.M., J.C.S.G., and C.A.A.V.; methodology, F.A.A.C.C., M.F.M., J.C.S.G., and C.A.A.V.; software, F.A.A.C.C.; validation, F.A.A.C.C., M.F.M., I.d.O.R., and F.B.F.; formal analysis, F.A.A.C.C., and I.d.O.R.; investigation, F.A.A.C.C.; resources, F.A.A.C.C.; data curation, F.A.A.C.C., and I.d.O.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.A.C.C., F.B.F., M.F.M., I.d.O.R., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; writing—review and editing, F.A.A.C.C., F.B.F., M.F.M., I.d.O.R., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; visualization, F.A.A.C.C., F.B.F., and M.F.M.; supervision, F.B.F., M.F.M., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; project administration, F.A.A.C.C., M.F.M., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; writing—review and editing, F.A.A.C.C., F.B.F., M.F.M., I.d.O.R., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; visualization, F.A.A.C.C., F.B.F., M.F.M., I.d.O.R., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; supervision, F.A.A.C.C., F.B.F., M.F.M., I.d.O.R., C.A.A.V., and J.C.S.G.; funding acquisition, F.A.A.C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES), grant number 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Material Synthesis Literature Review can be found at Resultado RIL.pptx.

Acknowledgments

To the Psychiatric Nursing Program of the School of Nursing of Ribeirão Preto (EERP-USP), to the Doctoral Program in Psychology of the Doctoral School of the University of Salamanca (USAL), to the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Salamanca (USAL), and to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Babinski, T.; Hirdes, A. Reabilitação psicossocial: A perspectiva de profissionais de centros de atenção psicossocial do Rio Grande do Sul. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2004, 13, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.; da Silva, J.C.B.; de Almeida, J.M.; Feitosa, F.B. Reabilitação Psicossocial: O Relato de um Caso na Amazônia. Saúde Redes 2021, 7 (Suppl. S2), 1–18. Available online: http://revista.redeunida.org.br/ojs/index.php/rede-unida/article/view/3272 (accessed on 5 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Godinho, D.M.; Peixoto Junior, C.A. Clínica em movimento: A cidade como cenário do acompanhamento terapêutico. Fractal 2019, 31, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Antonio, C.R.; da Mangini, F.N.R.; Lunkes, A.S.; de Marinho, L.C.P.; de Zubiaurre, P.M.; Rigo, J.; Siqueira, D.F.D. Projeto terapêutico singular: Potencialidades e dificuldades na saúde mental. Linhas Críticas 2023, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.F.L.; Mendes, A.M.P. Reabilitação Psicossocial E Cidadania: O Trabalho E A Geração De Renda No Contexto Da Oficina De Panificação Do Caps Grão-Pará. Cad. Bras. Saúde Ment. 2020, 12, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding, P. Mapping the rise of digital mental health technologies: Emerging issues for law and society. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2019, 67, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, I.; Granell, C. Considerations for designing context-aware mobile apps for mental health interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, M.; Schueller, S.M. State of the Field of Mental Health Apps. Cogn. Behav. Pr. 2018, 25, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, C.J.; Celleri, M. Aplicaciones móviles en salud mental: Percepción y perspectivas en Argentina. Psicodebate 2022, 22, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.P.; Barroso, B.; Deusdado, L.; Novo, A.; Guimarães, M.; Teixeira, J.P.; Leitão, P. Digital Technologies for Innovative Mental Health Rehabilitation. Electronics 2021, 10, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainsford, K.; Fitzgibbon, B.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Hoy, K.E. Transforming treatments for schizophrenia: Virtual reality, brain stimulation and social cognition. Psychiatry Res. Junho 2020, 288, 112974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Lewis, C.; Chi, H.; Singleton, G.; Williams, N. Mobile health applications for mental illnesses: An Asian context. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acebal, J.S.; Barbosa, G.C.; da Domingos, T.S.; Bocchi, S.C.M.; Paiva, A.T.U. O habitar na reabilitação psicossocial: Análise entre dois Serviços Residenciais Terapêuticos. Saúde Debate 2020, 44, 1120–1133. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-11042020000401120&tlng=pt (accessed on 4 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- De Zubiaurre, P.M.; Wasum, F.D.; Tisott, Z.L.; de Barroso, T.M.M.D.A.; De Oliveira, M.A.F.; De Siqueira, D.F. O desenvolvimento do projeto terapêutico singular na saúde mental: Revisão integrativa. Arq. Ciências Saúde UNIPAR 2023, 27, 2788–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bezerra, E.A.A.C.; Ferreira, A.A.; Bezerra, S.A.C.; da Portela, L.C.; Bezerra Júnior, S.A.C. Desenvolvimento de um protótipo móvel para auxiliar enfermeiros: Diagnóstico de enfermagem em saúde mental. Rev. Contemp. 2023, 3, 11228–11246. Available online: https://ojs.revistacontemporanea.com/ojs/index.php/home/article/view/1119 (accessed on 5 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.C. Aconchego: Construção e validação de aplicativo para apoio à saúde Mental. Dissertação. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brasil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli, A.; Karver, T.S.; Roundfield, K.D.; Woodruff, S.; Wierzba, C.; Wolny, J.; Kaufman, M.R. The Appa Health App for Youth Mental Health: Development and Usability Study. JMIR Form Res. 2023, 7, e49998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.I. Developing Mental or Behavioral Health Mobile Apps for Pilot Studies by Leveraging Survey Platforms: A Do-it-Yourself Process. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e15561. Available online: https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/4/e15561 (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Honaker, M.G.; Weitlauf, A.S.; Swanson, A.R.; Hooper, M.; Sarkar, N.; Wade, J.; Warren, Z.E. Paisley: Preliminary validation of a novel app-based e-Screener for ASD in children 18–36 months. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 1963–1975. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aur.2997 (accessed on 10 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Na, H.; Jo, M.; Lee, C.; Kim, D. Development and Evaluation: A Behavioral Activation Mobile Application for Self-Management of Stress for College Students. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1880. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/10/1880 (accessed on 10 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.A.S.; Cecchin, H.F.G.; Pimentel, S.M.; Spíndola, M.R.; Mota, M.R.S.; Martins, H.; Leite, F.S. Desenvolvimento de uma tecnologia mHealth para prevenção e literacia em saúde mental entre jovens universitários. Rev. Obs. 2023, 9, a16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, S.; Boudhraâ, S.; Dumont, M.; Tremblay, M.; Riendeau, S. Developing A Mobile App with a Human-Centered Design Lens to Improve Access to Mental Health Care (Mentallys Project): Protocol for an Initial Co-Design Process. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e47220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, L.P.C.; dos Reis, P.L.C.; Casarin, R.G.; Caritá, E.C.; Silva, S.S. Desenvolvimento de aplicativo móvel como estratégia de educação para o matriciamento em saúde mental. Rev. Eletrônica Debates Educ. Cient. Tecnol. 2023, 13, 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, L.; Furneaux-Bate, A.; Debenham, J.; Spallek, S.; Newton, N.; Chapman, C. Development of a Peer Support Mobile App and Web-Based Lesson for Adolescent Mental Health (Mind Your Mate): User-Centered Design Approach. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, E.A.; Lyman, C.; Roberts, J.E. Development of an mHealth App–Based Intervention for Depressive Rumination (RuminAid): Mixed Methods Focus Group Evaluation. JMIR Form Res. 2022, 6, e40045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.S.B.; Costa, L.S.P.; Carvalho, M.R.R.; de Mamede, R.S.B.; de Morais, J.B.; de Paula, M.L. Mobile web application for use in the Extended Family Health and Primary Care Center: Content and usability validation. Rev. CEFAC 2020, 22, 1–8. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-18462020000300509&tlng=en (accessed on 1 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- De Ferreira, L.F.A.; Benevides, A.M.L.N.; Rabelo, J.A.F.; Medeiros, M.S.; de Barros Filho, E.M.; Sanders, L.L.O.; Peixoto, R.A.C. Desenvolvimento, Satisfação e Usabilidade de plataforma móvel para monitoramento da saúde mental de estudantes universitários. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e19911225525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuck, N.; Dietel, F.A.; Nohr, L.; Vahrenhold, J.; Buhlmann, U. A smartphone app for the prevention and early intervention of body dysmorphic disorder: Development and evaluation of the content, usability, and aesthetics. Internet Interv. 2022, 28, 100521. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214782922000288 (accessed on 1 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ruf, A.; Koch, E.D.; Ebner-Priemer, U.; Knopf, M.; Reif, A.; Matura, S. Studying Microtemporal, Within-Person Processes of Diet, Physical Activity, and Related Factors Using the APPetite-Mobile-App: Feasibility, Usability, and Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, T.; Loureiro, L.; Botelho, M. Intervenção psicoeducacional promotora da literacia em saúde mental de adolescentes na escola: Estudo com grupos focais. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2021, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.; Orfão, N.H. População em Situação de Rua sob a Perspectiva da Intersetorialidade e Direitos Humanos na Gestão do Cuidado em Saúde. Saúde Redes 2022, 8 (Suppl. S1), 179–189. Available online: http://revista.redeunida.org.br/ojs/index.php/rede-unida/article/view/3486 (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. In PLoS Medicine; Public Library of Science: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Galvão, T.F.; Tiguman, G.M.B.; Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. A declaração PRISMA 2020: Diretriz atualizada para relatar revisões sistemáticas. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2022, 31, e112. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, H.A.; Nunes, L.A.; DeJesus, J.; Liverpool, S.; Moltrecht, B.; Neelakantan, L.; Harriss, E.; Watkins, E.; Fazel, M. Determination of Markers of Successful Implementation of Mental Health Apps for Young People: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e40347. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36350704 (accessed on 3 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Honey, M.L.L. User perceptions of mobile digital apps for mental health: Acceptability and usability—An integrative review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 147–168. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jpm.12744 (accessed on 4 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Pérez, A.; Matey-Sanz, M.; Granell, C.; Díaz-Sanahuja, L.; Bretón-López, J.; Casteleyn, S. AwarNS: A framework for developing context-aware reactive mobile applications for health and mental health. J. Biomed Inform. 2023, 141, 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaebel, W.; Lukies, R.; Kerst, A.; Stricker, J.; Zielasek, J.; Diekmann, S.; Roelandt, J.L.; Thorpe, L.; Topolska, D.; Assche, E.; et al. Upscaling e-mental health in Europe: A six-country qualitative analysis and policy recommendations from the eMEN project. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.; Scult, M.A.; Barnes, E.D.; Betancourt, J.A.; Falk, A.; Gunning, F.M. Smartphone apps for depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of techniques to increase engagement. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariman, K.; Ventriglio, A.; Bhugra, D. The Future of Digital Psychiatry. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.; Ponting, C.; Labao, J.P.; Sobowale, K. Considerations of diversity, equity, and inclusion in mental health apps: A scoping review of evaluation frameworks. Behav. Res. Ther. 2021, 147, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckvale, K.; Nicholas, J.; Torous, J.; Larsen, M.E. Smartphone apps for the treatment of mental health conditions: Status and considerations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, E.; Balvert, S.; Oorschot, M.; Borkelmans, K.; van Os, J.; Delespaul, P.; Fett, A.K. An ecological momentary intervention incorporating personalised feedback to improve symptoms and social functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, C.; Huckvale, K.; Carswell, K.; Torous, J. A Narrative Review of Methods for Applying User Experience in the Design and Assessment of Mental Health Smartphone Interventions. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2020, 36, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torous, J.; Vaidyam, A. Multiple uses of app instead of using multiple apps—A case for rethinking the digital health technology toolbox. Epidemiology Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Polson, D. Apps, Avatars, and Robots: The Future of Mental Healthcare. In Issues in Mental Health Nursing; Taylor and Francis Ltd: Milton Park, UK, 2019; pp. 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, S.; Schwannauer, M.; Berry, N. The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory. Psychol. Psychother. 2019, 92, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.M.; Firth, J.; Minen, M.; Torous, J. User engagement in mental health apps: A review of measurement, reporting, and validity. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, R.; Fitzgerald, A.; Segurado, R.; Dooley, B. Is there an app for that? A cluster randomised controlled trial of a mobile app–based mental health intervention. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 1538–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, M.; Anderberg, P.; Sanmartin Berglund, J.; Frögren, J.; Cano, N.; Cellek, S.; Zhang, J.; Garolera, M. Feasibility-usability study of a tablet app adapted specifically for persons with cognitive impairment—smart4md (Support monitoring and reminder technology for mild dementia). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgreen, T.; Rabbi, F.; Torresen, J.; Skar, Y.S.; Guribye, F.; Inal, Y.; Flobakk, E.; Wake, J.D.; Mukhiya, S.K.; Aminifar, A.; et al. Challenges and possible solutions in cross-disciplinary and cross-sectorial research teams within the domain of e-mental health. J. Enabling Technol. 2021, 15, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhiya, S.K.; Lamo, Y.; Rabbi, F. A Reference Architecture for Data-Driven and Adaptive Internet-Delivered Psychological Treatment Systems: Software Architecture Development and Validation Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 9, e31029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.; Al Khalifah, G.; Oyebode, O.; Orji, R. Apps for Mental Health: An Evaluation of Behavior Change Strategies and Recommendations for Future Development. Front. Artif. Intell. 2019, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timakum, T.; Xie, Q.; Song, M. Analysis of E-mental health research: Mapping the relationship between information technology and mental healthcare. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, C.L.; Myers, A.L.; Smagula, S.; Fortuna, K.L. Can Smartphone Apps Assist People with Serious Mental Illness in Taking Medications as Prescribed? Sleep Med. Clin. 2021, 16, 213–222. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33485529 (accessed on 11 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, N.E.; Armstrong, C.M.; Hoyt, T.V. Smartphone apps for psychological health: A brief state of the science review. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, J.A.; Jacob, J.D.; Siegle, G.J.; Dey, A.; Thase, M.E.; Dabbs, A.D.; Kazantzis, N.; Rotondi, A.; Tamres, L.; Van Slyke, A.; et al. CBT MobileWork: User-Centered Development and Testing of a Mobile Mental Health Application for Depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2020, 45, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Li, L.; Torous, J.; Gratzer, D.; Yellowlees, P.M. Review and Implementation of Self-Help and Automated Tools in Mental Health Care. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz, J.M.; Van Boxtel, R.; Torous, J.; Firth, J.; Lebovitz, J.G.; Burdick, K.E.; Hogan, T.P. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression: Scoping Review of User Engagement. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e39204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchert, S.; Alkneme, M.S.; Bird, M.; Carswell, K.; Cuijpers, P.; Hansen, P.; Heim, E.; Shehadeh, M.H.; Sijbrandij, M.; Hof, E.V.; et al. User-centered app adaptation of a low-intensity e-mental health intervention for Syrian refugees. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.; Benedetto, E.; Huang, H.; Grossman, E.; Kaluma, D.; Mann, Z.; Torous, J. Augmenting mental health in primary care: A 1-Year Study of Deploying Smartphone Apps in a Multi-site Primary Care/Behavioral Health Integration Program. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruzan, K.P.; Reddy, M.; Washburn, J.J.; Mohr, D.C. Developing a Mobile App for Young Adults with Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: A Prototype Feedback Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghouts, J.; Eikey, E.; Mark, G.; De Leon, C.; Schueller, S.M.; Schneider, M.; Stadnick, N.; Zheng, K.; Mukamel, D.; Sorkin, D.H. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, M.A.; Shanahan, L.; Rohde, J.; Schulz, A.; Wackerhagen, C.; Kobylińska, D.; Tuescher, O.; Binder, H.; Walter, H.; Kalisch, R. Standalone Smartphone Cognitive Behavioral Therapy–Based Ecological Momentary Interventions to Increase Mental Health: Narrative Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e19836. Available online: https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/11/e19836 (accessed on 11 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- McCall, T.; Ali, M.O.; Yu, F.; Fontelo, P.; Khairat, S. Development of a Mobile App to Support Self-management of Anxiety and Depression in African American Women: Usability Study. JMIR Form Res. 2021, 5, e24393. Available online: https://formative.jmir.org/2021/8/e24393 (accessed on 11 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinengo, L.; Stona, A.C.; Griva, K.; Dazzan, P.; Pariante, C.M.; von Wangenheim, F.; Car, J. Self-guided Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Apps for Depression: Systematic Assessment of Features, Functionality, and Congruence with Evidence. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27619. Available online: https://www.jmir.org/2021/7/e27619 (accessed on 15 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eis, S.; Solà-Morales, O.; Duarte-Díaz, A.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Robles, N.; Carrion, C. Mobile Applications in Mood Disorders and Mental Health: Systematic Search in Apple App Store and Google Play Store and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F.; Kermani, Z.A.; Khademian, F.; Aslani, A. Critical Appraisal of Mental Health Applications. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 261, 303–308. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31156135 (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Parmar, P.; Ryu, J.; Pandya, S.; Sedoc, J.; Agarwal, S. Health-focused conversational agents in person-centered care: A review of apps. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.B.; Chan, S.R.; Yee-Marie Tan Gipson, S.; Kim, J.W.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Luo, J.; Wang, P. A hierarchical framework for evaluation and informed decision making regarding smartphone apps for clinical care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statcounter. Operating System Market Share Worldwide. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Deng, M.; Wuyts, K.; Scandariato, R.; Preneel, B.; Joosen, W. A privacy threat analysis framework: Supporting the elicitation and fulfillment of privacy requirements. Requir. Eng. 2010, 16, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, L.; Torous, J.; Vahia, I.V. Data Security and Privacy in Apps for Dementia: An Analysis of Existing Privacy Policies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurgalieva, L.; O’Callaghan, D.; Doherty, G. Security and Privacy of mHealth Applications: A Scoping Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 104247–104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, K.; Neary, M.; Adkins, E.C.; Schueller, S.M. Reviewing the data security and privacy policies of mobile apps for depression. Internet Interv. 2018, 15, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Halter, V.; Karliychuk, T.; Grundy, Q. How private is your mental health app data? An empirical study of mental health app privacy policies and practices. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2019, 64, 198–204. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0160252718302681 (accessed on 10 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, G. Second Mind: Considerações Ético-Legais sobre a Digitalização em Saúde Mental no Contexto Português. Rev. Port. Psiquiatr. Saúde Ment. 2022, 8, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, N.; Greely, H.T.; Cho, M.K. Ethical development of digital phenotyping tools for mental health applications: Delphi study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e27343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huckvale, K.; Torous, J.; Larsen, M.E. Assessment of the Data Sharing and Privacy Practices of Smartphone Apps for Depression and Smoking Cessation. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagan, S.; Emerson, M.R.; King, D.; Matwin, S.; Chan, S.R.; Proctor, S.; Tartaglia, J.; Fortuna, K.L.; Aquino, P.; Walker, R.; et al. Mental Health App Evaluation: Updating the American Psychiatric Association’s Framework Through a Stakeholder-Engaged Workshop. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaya, L.H.; Babar, M.A.; Rashid, A.; Wijayarathna, C. On the privacy of mental health apps. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2022, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simões Almeida, R.; Marques, A. User engagement in mobile apps for people with schizophrenia: A scoping review. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, P.; Karmacharya, R.; Salisbury, T.T.; Carswell, K.; Kohrt, B.A.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Lempp, H.; Thornicroft, G.; Luitel, N.P. Perception of healthcare workers on mobile app-based clinical guideline for the detection and treatment of mental health problems in primary care: A qualitative study in Nepal. BMC Med. Informatics Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnike, A.N.; Dale, B.J. Rewiring Mental Health: Legal and Regulatory Solutions for the Effective Implementation of Telepsychiatry and Telemental Health Care. Houst J. Health Law Policy 2017, 17, 21–103. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Martín-Herrera, I. Cortesía en Internet. Presentación de una guía multidisciplinar sobre la netiqueta. Anagramas Rumbos Y Sentidos De La Comunicación 2023, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.C.; García, J.C.S.; Feitosa, F.B.; de Reis, I.O.; Caritá, E.C.; Moll, M.F.; Ventura, C.A.A. Theoretical and bioethical foundations for the development of the psychosocial rehabilitation project application. Saúde Redes 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschoarelli, L.C.; da Silva, J.C.P. Importância do estudo metodológico para o desenvolvimento da área do design informacional. In Rumos da Pesquisa no Design Contemporâneo: Relação Tecnologia × Humanidade; Estação das Letras e Cores Editora Ltda: Barueri, Brazil, 2013; pp. 50–67. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281873709 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Paschoarelli, L.C.; Medola, F.O.; Bonfim, G.H. Características Qualitativas, Quantitativas e Quali-quantitativas de Abordagens Científicas: Estudos de caso na subárea do Design Ergonômico. Rev. Des. Tecnol. Soc. 2015, 2, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, E.K.; Cruz, M.F.; Andrade-Arenas, L. Machine Learning Applied to Prevention and Mental Health Care in Peru. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.; Roberts, L.W. The Ethical Use of Mobile Health Technology in Clinical Psychiatry. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, R.A.S. Desenvolvimento de Protótipo de Tecnologia Digital Para Apoio Aos Profissionais de Enfermagem Frente ao Estresse Ocupacional: Proposta de Intervenção. Master’s Dissertation, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, L.S.; Oliveira, E.N.; Vasconcelos, M.I.O.; Fernandes, C.A.R.; Dutra, M.C.X.; de Almeida, P.C. Desenvolvimento e validação de um jogo educativo sobre uso abusivo de drogas e o risco de suicídio. SMAD Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Ment. Álcool Drog. 2023, 19, 16–25. Available online: https://www.revistas.usp.br/smad/article/view/188483 (accessed on 9 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Farias, Q.L.T. Tecnologia Educativa Digital Para Promoção da Saúde Mental de Adolescentes: Estudo de Validação Por Especialistas. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Sobral, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gusmão, E.C.R. Construção E Validação de Um Aplicativo de Identificação das Habilidades Adaptativas de Crianças E Adolescentes com Deficiência Intelectual. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).