Abstract

Mental disorders encompass conditions that affect cognition, emotions, and behavior, representing a major public health challenge. In Colombia, there are no studies that estimate the burden of disease caused by mental and behavioral disorders. This study aimed to determine the burden of disease attributable to these conditions in the departments of Colombia in 2022. A burden of disease analysis was conducted using official national data sources, including the Individual Health Service Delivery Records and death certificates from the Vital Statistics System, consolidated by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection within the Integrated Social Protection Information System. Estimation methods followed the World Health Organization’s Global Health Estimates framework. Disability-Adjusted Life Years were used as the summary measure, integrating mortality and non-fatal outcomes to quantify the overall population impact. A total of 296,010.6 Disability-Adjusted Life Years were estimated (95% UI: 279,343.2–312,678), representing a rate of 572.7 (95% UI: 540.5–605) per 100,000 population. Anxiety accounted for 47.26%. Women represented 60.86% of the total burden, with 180,157.6 (95% UI: 165,046.3–195,268.9). Overall, 99.27% of the burden from mental and behavioral disorders was due to Years Lived with Disability, underscoring the substantial impact on quality of life, particularly among women.

1. Introduction

Mental disorders comprise a set of clinically identifiable symptoms and behaviors, cognition, emotional regulation, and behavioral functioning leading to significant limitations in daily activities [1,2,3]. In recent decades, mental and behavioral disorders (MBDs) have become an increasing public health priority due to their high prevalence and substantial impact on quality of life, healthcare systems, and national economies [4,5].

Accurately assessing their population impact requires metrics that integrate both mortality and disability. Traditional indicators based solely on mortality or prevalence fail to capture the duration, severity, and functional consequences of these conditions. Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), used in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) framework and adopted by the WHO Global Health Estimates (GHE), address these limitations by combining Years of Life Lost (YLL) and Years Lived with Disability (YLD) into a single measure [6,7,8,9,10].

In Colombia, population-based assessments of mental and behavioral disorders have relied predominantly on mortality and prevalence statistics, limiting the understanding of their functional impact. Although DALYs have become essential worldwide for guiding health policies and prioritizing interventions, their use in Colombia remains limited, and no recent subnational studies have estimated the burden of disease associated with MBDs using GBD methodology [6,11,12,13].

This gap restricts the capacity of territorial health authorities to plan and allocate resources based on comparable and standardized burden estimates. Therefore, the present study aimed to quantify the burden of disease attributable to mental and behavioral disorders across Colombian departments in 2022, providing updated evidence to inform national and subnational decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

A descriptive study was conducted using secondary data sources. Estimation procedures were based on the creation of synthetic indicators, such as YLL, YLD, and DALYs. The study population consisted of Colombians in 2022, according to records from the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), totaling 51,874,024 people (distributed across the country’s 32 departments). From this population, individuals who became ill or died from mental or behavioral disorders during that period and were properly registered in official databases were selected. Mortality data from Colombia’s Vital Statistics System were obtained through the Single Affiliation Registry (RUAF) database, and the Individual Health Service Provision Records (RIPS), both of which are available in the respective databases of the Integrated Social Protection Information System (SISPRO). They have restricted access that requires a username and password assigned by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection (MSPS), in accordance with Law 1581 of 2012 [14].

Disorders were classified according to their frequency of occurrence. Morbidity causes were identified using the primary diagnosis, and mortality causes through the underlying cause of death. Records lacking primary diagnoses or underlying causes, as well as duplicate entries, were excluded. Organic mental disorders, including symptomatic disorders, mental and behavioral disorders caused by tobacco use, mental and behavioral disorders derived from the use of other stimulants including caffeine and unspecified mental disorders, were also omitted. Likewise, the study did not incorporate diseases with no assigned weights in the methodology, as well as the group labeled as “others” or “unidentified.” These diseases did not allow for clear classification and weight assignment within each group.

A total of 112 ICD-10 codes were selected, each associated with an estimated disability weight drawn from the WHO (Supplementary Materials Table S1). Table of sequelae and health states. The WHO Global Health Estimates framework was applied, disaggregated by sex and age group, and disability weights for mental and behavioral disorders were assigned following this methodology [15]. YLL and YLD were calculated using the WHO’s abridged formula, incorporating life expectancy, number of cases, and estimated duration of disability. DALYs were obtained by summing YLL and YLD by age, sex, and department (Supplementary Materials Table S2).

Although administrative health databases provide wide population coverage, they are subject to potential underreporting, miscoding, and variability in diagnostic practices, which were considered when interpreting the results.

Equation (1): Basic formula for YLLs.

D is the number of deaths due to the cause (c) in the age group (a), in sex (s), and year (t) is the life expectancy at each age (the weighting factor is derived from the standard life expectancy (SLE) recommended by WHO, based on a 92-year-old SLE).

Equation (2): Basic formula for YLDs.

W is the disability weight, P is the prevalence of the disease or injury (c), in the age group (a), according to sex (s), and year (t), according to the Global Burden of Disease Study [15] disability weights for each health state.

Equation (3): Basic formula for DALYs.

(c) is disease or injury, (a) the age group, (s) the sex, and (t) is the year.

* The study presents crude rates that were not age-standardized

The indicators were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical considerations: The study was classified as minimal risk and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles established by national and international regulations. It followed the GATHER statement (Supplementary Materials Table S3), which aims to enhance transparency in the reporting of health estimates based on multiple data sources [16]. Additionally, this study complied with the ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving humans established by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), specifically guidelines 1, 9, and 12 [17].

3. Results

3.1. Years of Life Lost (YLLs)

During 2022, a total of 59 deaths attributed to mental and behavioral disorders were reported in the country. Of these, 89.8% (53 cases) were related to disorders due to psychoactive substance use. A total of 2132.7 (95% UI: 1504.3–2761.1) YLL were calculated and attributed to mental and behavioral disorders, with a rate of 4.1 (95% UI: 2.9–5.3) YLL per 100,000 inhabitants. Regarding sex comparison, the premature death rate in men is 8.33 times higher than in women. Concerning age distribution, a higher number of YLL were observed in men over 60 years old, especially in the 60 to 64-year age group.

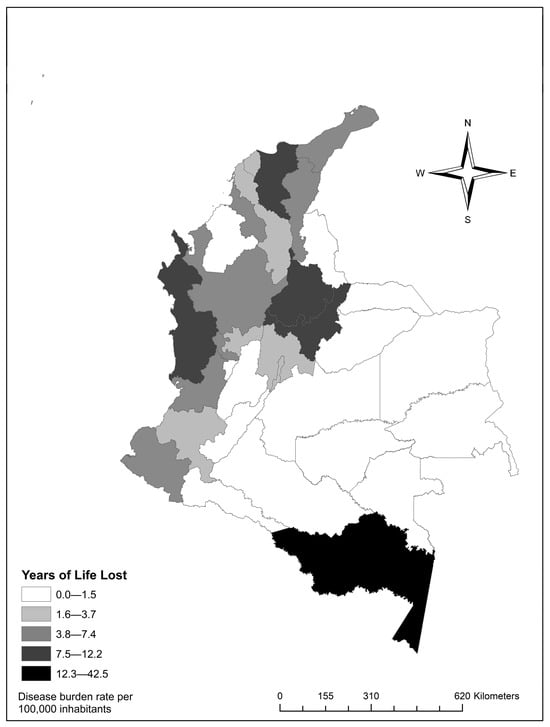

When classifying departments with the highest YLL rates, the department of Amazonas showed a rate of 42.5 (95% UI: 0–28.8) premature deaths, followed by Chocó with a rate of 12.2 (95% UI: 0–130.1) (see Figure 1) (Supplementary Materials Table S4).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Years of Life Lost (YLLs) rates by department.

3.2. Years Lived with Disability (YLDs)

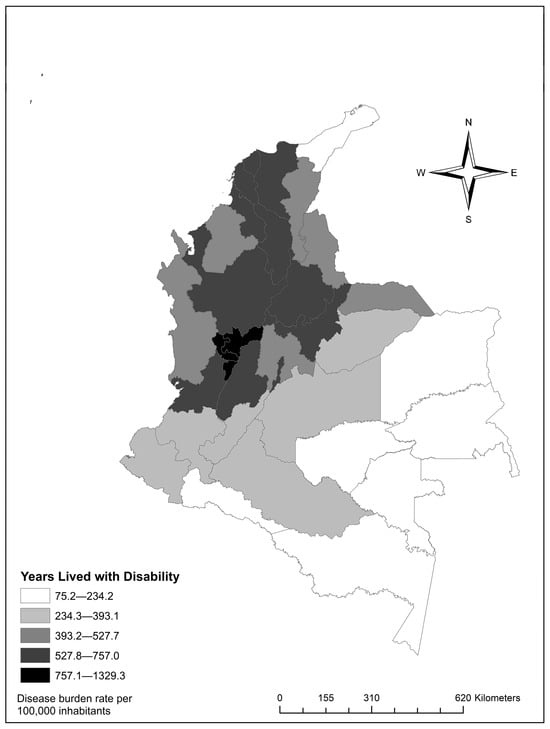

A total of 38,052 cases of mental and behavioral disorders (classified under 112 ICD-10 codes) were recorded. Of these, 19,453 occurred in men (51%). Regarding health loss, an estimated 293,877.8 (95% UI: 277,218.5–310,537.2) YLDs were calculated, with a rate of 568.6 (95% UI: 536.4–600.9) YLDs per 100,000 inhabitants (see Figure 2). As for sex, men had a 0.34 times lower rate of suboptimal health compared to women.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) rates by department.

In the distribution of YLD rates by department, Quindío showed the highest YLD rate of 1329.3 (95% UI: 946.6–1711.9), attributable to mental and behavioral disorders. Meanwhile, Amazon and Orinoquía regions exhibited the lowest health loss values. The departments of Guainía 121.2 (95% UI: 73.2–168.3), Vaupés 101.4 (95% UI: 61.5–137.6), and Vichada 75.1 (95% UI: 51.1–98.8) stood out among them (Supplementary Materials Table S5).

3.3. Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs)

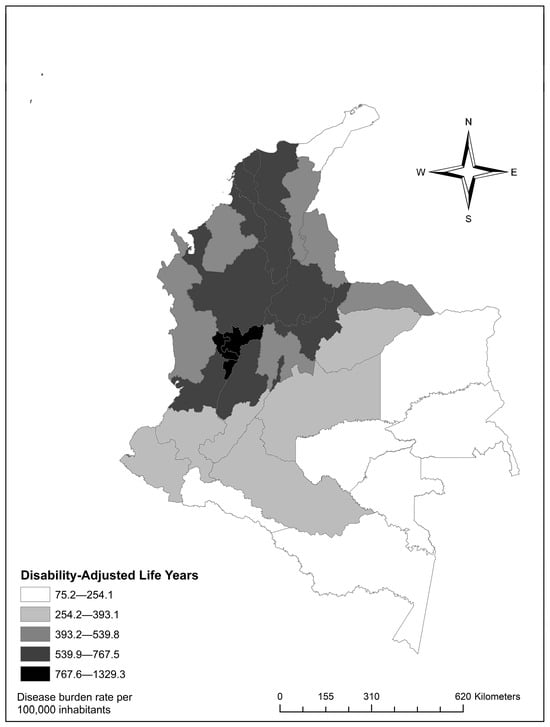

A total of 296,010.6 Disability-Adjusted Life Years were estimated (95% UI: 279,343.2–312,678), with a rate of 572.7 (95% UI: 540.5–605) DALYs per 100,000 inhabitants. This is the result of adding YLL and DALYs caused by mental and behavioral disorders. It represents the total DALYs produced by these disorders in Colombia for 2022.

At the departmental level, the highest burden was observed in neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders, and somatoform disorders, which accounted for 156,099.59 (95% UI: 140,954.4–171,244.8) DALYs. Schizophrenia, schizotypal disorders, and delusional disorders followed with 53348.6 (95% UI: 48,804.2–57,893.0). Finally, mood disorders accounted for 53,307.2 (95% UI: 51,182.7–55,431.5), (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Disability-Adjusted Life Years rates by department.

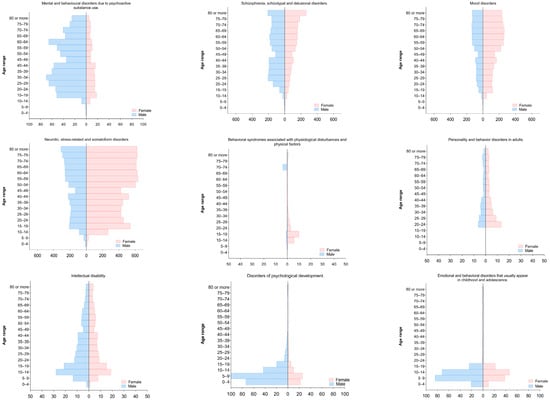

Quindío had the highest rate, with 1329.3 (95% UI: 946.6–1711.9). Risaralda followed with 1047.6 (95% UI: 715.8–1359.5), and Caldas, with 1006.6 (95% UI: 714.7–1297.9) (Supplementary Materials Table S6). In age distribution, the burden increased with age, with patterns varying by specific disorder (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of disability-adjusted life years by subgroups according to age and sex, 2022.

4. Discussion

In Colombia, in the year 2022, mental and behavioral disorders accounted for 296,010.6 DALYs (95% UI: 279,343.2–312,678), representing a rate of 572.7 per 100,000 population (95% UI: 540.5–605), of which 99.27% was attributable to YLDs. The marked predominance of YLD over YLL is consistent with international reports, where the burden of mental disorders arises primarily from prolonged disability rather than direct mortality [18,19,20]. This pattern is explained by the fact that most individuals with these disorders do not die from the primary condition but from other medical and behavioral comorbidities [7,21,22].

The study identified sex differences, with women contributing 180,157.6 DALYs (95% UI: 165,046.3–195,268.9), at rates of 681.1 (95% UI: 623.9–738.2), equivalent to 60.86% of the national burden from these disorders. This demonstrates greater vulnerability in this population group, consistent with recent international evidence showing a higher burden and prevalence of mental disorders among women [23].

In the analysis by specific cause, anxiety disorders accounted for 52.7% of total DALYs, followed by schizophrenia (18%) and bipolar disorder (8.9%). This order is partially consistent with global studies such as the GBD 2019 publication, where depressive disorders represented the largest proportion (37.3%), followed by anxiety (22.9%) and schizophrenia (12.2%) [18,24]. Differences may be justified by subnational variations in prevalence, diagnostic patterns, data availability, and territorial inequalities [25].

Regarding anxiety, this study estimated 156,099.6 DALYs (95% UI: 140,954.4–171,244.8), with a rate of 302.0 (95% UI: 272.7–331.3), which is consistent with global data. Studies report that anxiety affected nearly 46 million people worldwide in 2017 [26], and in 2019, the WHO reported approximately 301 million individuals living with an anxiety disorder [3], representing a large share of the global burden [27,28,29] Sex differences were evident, with women accounting for 62% of the burden, aligning with several studies [29,30]. With respect to age, a marked increase was observed among women older than 50 years, consistent with evidence linking biological aging and psychosocial changes to greater susceptibility to anxiety [31,32].

For schizophrenia, 53,348.6 DALYs (95% UI: 48,804.2–57,893.0) were recorded, with a rate of 103.2 (95% UI: 94.4–112.0). Males accounted for 59.1% of this burden, consistent with findings documenting a higher impact in this group [33,34]. The highest burden was observed among individuals aged 15–19 years, consistent with the typical age of onset described for this disorder [35,36,37].

Bipolar disorders caused 26,454.8 DALYs (95% UI: 25,1.00–27,852.6), with rates of 51.2 (95% UI: 48.5–53.9). Several studies report similar results [38,39], with more than 40 million people affected worldwide [3]. The burden among women reached 62.3%, although evidence is variable regarding which sex is most affected; some reports indicate that women have higher rates of bipolar disorders [39,40]. The 2019 GBD Mental Health study identified 39.5 million cases, of which approximately 52.4% were women [18].

Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use accounted for 13,046.74 DALYs (95% UI: 11,993.8–14,099.6), with a rate of 25.24 (95% UI: 23.2–27.3). A pronounced sex difference was identified, with males representing 79.1% of this burden, and a higher impact was observed among adolescents and young adults. These findings are consistent with studies identifying this group as the most vulnerable [41,42,43,44].

When disaggregated by substance type, alcohol accounted for 40.9% of DALYs attributable to psychoactive substances and 1.8% of total DALYs from mental disorders, while opioids represented 0.9%. These results reflect a greater burden from alcohol consumption in Colombia and align with GBD 2016 estimates, which reported approximately 4.2% of global DALYs attributable to alcohol and about 1.3% associated with psychoactive substances, including opioids [45]. Among the burden attributable to alcohol, 84% corresponded to males, a trend observed in Latin American studies and in GBD 2016 and 2021 estimates, where men are the major contributors to alcohol-attributable DALYs [40,45,46,47]. Additionally, in Colombia, the 2013 National Consumption Survey reported that 73% of alcohol users were men [48].

Territorially, three departments showed the highest rates: Quindío with 1329.3 (95% UI: 946.6–1711.9), Risaralda with 1047.6 (95% UI: 715.8–1359.5), and Caldas with 1006.6 (95% UI: 714.7–1297.9). In all departments, anxiety was the main contributor to DALYs, except in Magdalena, where schizophrenia reached a rate of 224.2 (95% UI: 157.3–291.1), surpassing other disorders in that territory. These differences may be explained by a combination of structural factors such as greater urbanization, population concentration, and better access to mental health services, which facilitate detection. In territories with greater limitations, such as Magdalena, severe disorders may represent a larger burden due to limited availability of specialized services, diagnostic barriers, and low treatment continuity. Additionally, territorial heterogeneity overlaps with areas affected by conflict, socioeconomic inequality, and displacement, shaping the distribution of mental disorders [25,49,50].

5. Conclusions

In Colombia, mental and behavioral disorders remain a major contributor to the national burden of disease. The distribution of this burden shows marked differences by sex and territory, with a higher proportion of YLDs among women and a higher-level occurrence of YLLs among men, reflecting persistent inequalities in social determinants and access to mental health services.

These findings highlight the need to strengthen intersectoral policies aimed at prevention, early detection, and comprehensive care, incorporating territorial and equity-based approaches. Integrating this evidence into health planning and resource allocation could enhance the efficiency of interventions and the responsiveness of the health system. The results may guide national and subnational strategies to optimize resource distribution and strengthen the health system’s response to MBDs in the country.

Limitations

Limitations inherent to secondary data analysis are acknowledged. The quality of estimates depends on the accuracy and completeness of national records, which may lead to diagnostic errors, underreporting, or duplication of cases. Mortality associated with mental disorders is likely underestimated, as death certificates often prioritize the immediate cause rather than underlying psychiatric conditions. Additionally, regional disparities in diagnostic capacity and the exclusion of categories without assigned weights may limit comparability with international studies. Furthermore, subnational comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as the estimates were not age-standardized, which may affect comparability between regions with different demographic structures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22121854/s1, Table S1: Assignment of diagnoses to diagnostic groups; Table S2: Mental and Behavioral Disorders in Colombia, 2022; Table S3: Annex Table GATHER; Table S4: YLL Rate by Disorders and Department; Table S5: YLD rate (Years Lived with Disability) by disorders, by department, Colombia 2022; Table S6: DALY rate (Disability-Adjusted Life Years) by disorders, by department, Colombia 2022.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.J.Q.D., O.A.G.L. and E.S.R.; methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, and data curation, K.J.Q.D. and O.A.G.L.; writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing, K.J.Q.D., O.A.G.L. and E.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the University of Los Llanos through the project: “Development of an Observatory on Mental Health, Family, and Social Coexistence for the Design of Comprehensive Strategies, Knowledge Management, and the Formulation of Policies, Plans, and Programs in Colombian Orinoquía” code: 112291891873, contract 655/2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study was classified as minimal ethical risk and used secondary, aggregated, and publicly available data from SISPRO. These data were collected by state entities under national health policies and regulations that ensure confidentiality and ethical management. Therefore, ethical review and approval were waived in accordance with the CIOMS Guideline 12, which establishes that informed consent and formal ethical approval are not required for studies using anonymized, population-based, and mandatory registry data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required for this study, as the unit of analysis consisted of aggregated data grouped by geographic area, age, sex, and cause, without any identifiable individual information. The researchers had no direct contact with participants and did not access personal data. According to Guideline 12 of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), informed consent may be waived when data are obtained from mandatory population-based health records collected in the context of routine healthcare, as was the case with the official databases used in this research.

Data Availability Statement

The morbidity and mortality data used in this study were obtained from the MSPS (https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Portada/index.html), accessed on 5 March 2024, through SISPRO (https://www.sispro.gov.co/Pages/Home.aspx), accessed on 5 March 2024, which hosts the RUAF and RIPS databases (https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1NDSv6yfFnpMpPdhG0jZMko75BnO7op1n?usp=sharing). Access to these datasets is restricted and granted upon formal request to the MSPS, in compliance with Statutory Law 1581 of 2012 [14], which authorizes the use of data for historical, statistical, or scientific purposes. Researchers must request access credentials by contacting the MSPS at (sispro_bodega@minsalud.gov.co), and are subsequently provided with login information to access the SISPRO server through an SQL Server Analysis Services cube in Excel for data extraction and processing. Mortality records were obtained from the RUAF–Non-Fetal Mortality database, and morbidity data from RIPS. Demographic information was drawn from the 2022 national population projections published by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) (https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php), accessed on 6 March 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CIOMS | Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DANE | National Administrative Department of Statistics |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| GHE | Global Health Estimates |

| MSPS | Ministry of Health and Social Protection |

| RIPS | Individual Health Service Provision Records |

| RUAF | Single Affiliation Registry |

| SISPRO | Integrated Social Protection Information System |

| YLD | Years lived with disability |

| YLLs | Years of Life Lost |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.federaciocatalanatdah.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/dsm5-manualdiagnsticoyestadisticodelostrastornosmentales-161006005112.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Cuesta-Mosquera, E.L.; Picón-Rodríguez, J.P.; Pineida-Parra, P.M. Current Trends in Depression, Risk Factors, and Substance Abuse. J. Am. Health 2022, 5. Available online: https://jah-journal.com/index.php/jah/article/view/114/226 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Mental Disorders. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Salinas Fredricson, A.; Krüger Weiner, C.; Adami, J.; Rosén, A.; Lund, B.; Hedenberg-Magnusson, B.; Fredriksson, L.; Naimi-Akbar, A. The Role of Mental Health and Behavioral Disorders in the Development of Temporomandibular Disorder: A SWEREG-TMD Nationwide Case-Control Study. J. Pain. Res. 2022, 15, 2641–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Araoz, E.; Paricahua-Peralta, J.; Paredes-Valverde, Y.; Quispe-Herrera, R. Prevalence of common mental disorders in university students. Rev. Cuba. Med. Mil. 2023, 52, e02302968. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0138-65572023000400012 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Gutiérrez Lesmes, O.A.; Grisales-Romero, H. Burden of disease in Colombian Orinoquia, 2017. F1000Research 2022, 11, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Zayeri, F.; Salehi, M. Trend analysis of cardiovascular disease mortality, incidence, and mortality-to-incidence ratio: Results from global burden of disease study 2017. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Ma, H.; Wang, Y. Trends in the prevalence and disability-adjusted life years of eating disorders from 1990 to 2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Vos, T.; Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Flaxman, A.D.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S.; et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2197–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata-Casas, L.; Gutierrez-Lesmes, O.A.; Cala-Vitery, F. The burden of tuberculosis disease in women, Colombia 2010–2018. Infectio 2023, 27, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisales-Romero, H.; González, D.; Porras, S. Disability-Adjusted Life Years Due to Mental Disorders and Diseases of the Nervous System in the Population of Medellin, 2006–2012. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2020, 49, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Lesmes, O.A.; Vinasco-Ramos, D.S.; Plata-Casas, L.I. Burden of Disease from HIV/AIDS in the Colombian Orinoquía Region, 2010–2018. Bol. Semillero Investig. Fam. 2023, 5, e-828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de Colombia. Ley 1581 de 2012—Ley de Protección de Datos Personales. 2012. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma_pdf.php?i=49981 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Department of Data Analytics Division of Data Analytics Delivery for Impact, WHO. WHO Methods and Data Sources for Global Burden of Disease Estimates 2000–2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G.A.; Alkema, L.; Black, R.E.; Boerma, J.T.; Collins, G.S.; Ezzati, M.; Grove, J.T.; Hogan, D.R.; Hogan, M.C.; Horton, R.; et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: The GATHER statement. Lancet 2016, 388, e19–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization; Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans; CIOMS: Geneve, Switzerloand, 2017; 150p, Available online: https://cioms.ch/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/CIOMS-EthicalGuideline_SP_INTERIOR-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios-Jiménez, N.M.; Duque-Molina, C.; Alarcón-López, A.; Beatriz González-Mota, S.; Miranda-García, M.; Paredes-Cruz, F.; Valle-Arteaga, E.I.; Reyna-Sevilla, A. Mental Health: Importance of the Issue, Strategies, and Challenges for the IMSS. Rev. Med. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2022, 60, 150–159. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10627502/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, F.; Origoni, A.; Schroeder, J.; Schweinfurth, L.A.B.; Stallings, C.; Savage, C.L.G.; Katsafanas, E.; Banis, M.; Khushalani, S.; Yolken, R. Mortality in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Clinical and serological predictors. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 170, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, T.; Marwaha, S. Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 8, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Fan, A.; Yang, Z.; Fan, D. Global burden of mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: Results from the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, G.; Song, J.; Service, S.K.; Ramirez-Diaz, A.M.; Diaz-Zuluaga, A.M.; Arias, A.; Castaño-Ramirez, M.; Crossley, N.A.; Lopez-Jaramillo, C.; Freimer, N.B.; et al. Socioeconomic and geographic disparities in psychiatric outcomes under Colombia’s universal healthcare system. Psychol. Med. 2025, 55, e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.; van Ommeren, M.; Flaxman, A.; Cornett, J.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, J.; Expósito, V.; Torres, E. Epidemiology of anxiety and its context in Primary Care. Aten. Primaria Práct. 2024, 6, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Reangsing, C.; Trakooltorwong, P.; Maneekunwong, K.; Thepsaw, J.; Oerther, S. Effects of online mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on anxiety symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanazzo, S.; Mansueto, G.; Cosci, F. Anxiety in the Medically Ill: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 873126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Geng, T.; Jiang, M.; Huang, N.; Zheng, Y.; Belsky, D.; Huang, T. Accelerated biological aging and risk of depression and anxiety: Evidence from 424,299 UK Biobank participants. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnon, V.; Dutheil, F.; Vallet, G. Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendrek, A.; Mancini-Marïe, A. Sex/gender differences in the brain and cognition in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 67, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, K.M.; Drake, R.; Goldstein, J.M. Sex differences in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.; Ferrari, A.; Santomauro, D.; Diminic, S.; Stockings, E.; Scott, J.G.; McGrath, J.J.; Whiteford, H.A. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.; Arango, C.; Fagerlund, B.; Galderisi, S.; Kas, M.; Leucht, S. Identificación y tratamiento de personas con esquizofrenia de inicio infantil y de inicio temprano. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 82, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.M.; Bucci, P.; Mucci, A.; Pezzella, P.; Galderisi, S. Gender Differences in Clinical and Psychosocial Features Among Persons With Schizophrenia: A Mini Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 789179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierenberg, A.A.; Agustini, B.; Köhler-Forsberg, O.; Cusin, C.; Katz, D.; Sylvia, L.G.; Peters, A.; Berk, M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Kong, L.; Baweja, R.; Ba, D.; Saunders, E. Gender disparity in bipolar disorder diagnosis in the United States: A retrospective analysis of the 2005–2017 MarketScan Commercial Claims database. Bipolar Disord. 2022, 24, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors by state in the USA, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 404, 2314–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Burgos, L.; Guzmán-Saldaña, R.; Márquez-Corona, M.; Pontigo-Loyola, A.; Márquez-Rodríguez, S.; Mora-Acosta, M.; Acuña-González, G.R.; Hernández-Morales, A.; Medina-Solís, C.E. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption: A National Ecological Study in Mexican Adolescents. Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 3604004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moan, I.S.; Bye, E.K.; Rossow, I. Stronger alcohol-violence association when adolescents drink less? Evidence from three Nordic countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakutsikwa, B.; Britton, J.; Langley, T. The effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on poverty in the United Kingdom. Addiction 2021, 116, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, H.E.; Moffitt, T.E.; Copeland, W.E.; Costello, E.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Patton, G.; Degenhardt, L.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. A heavy burden on young minds: The global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 987–1012, Correction in Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 987–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30488-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.A.; Rincon, V.M.C.; Serna, H.V.; Bersh, S. Alcohol Consumption and Bipolar Disorder in a Colombian Population Sample. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2020, 49, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhong, G.; Xu, C.; Chen, T.; Du, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, M.; Du, J. Trends and cross-country inequalities of alcohol use disorders: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Global Health 2025, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho; Observatorio de Drogas de Colombia; Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. Estudio de Mortalidad Asociada al Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas 2013–2020; Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho—Observatorio de Drogas de Colombia (ODC); Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses: Bogotá, Colombia, 2022. Available online: https://www.minjusticia.gov.co/programas-co/ODC/Documents/Publicaciones/Consumo/Estudios/Nacionales/informederesultados.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- León-Giraldo, S.; Casas, G.; Cuervo-Sanchez, J.S.; Gonzalez-Uribe, C.; Bernal, O.; Moreno-Serra, R.; Suhrcke, M. Health in Conflict Zones: Analyzing Inequalities in Mental Health in Colombian Conflict-Affected Territories. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 595311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón Garavito, G.A.; Burgess, R.; Dedios Sanguinetti, M.C.; Peters, L.E.R.; Vera San Juan, N. Mental health services implementation in Colombia–A systematic review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).