Abstract

Various structural, organizational, and subjective factors contribute to psychological distress, exacerbated by adverse working conditions in mental health services and resulting in significant impacts on workers’ health. This study aims to map the existing literature on work-related factors and consequences associated with the illness of mental health service workers. A scoping review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. The review question was formulated based on the population, concept, and context framework. Searches were performed in eight electronic databases, and the findings were synthesized in synoptic tables. A total of 28 studies were included, addressing factors encompassing structural, organizational, and procedural aspects of the work environment, as well as social and relational elements involving the healthcare team, users, and their families, all contributing to workers’ illness. The main challenges identified include work overload, excessive working hours, inadequate physical infrastructure, insufficient supplies, understaffing, lack of managerial support, and exposure to physical, biological, chemical, and ergonomic risks. The analysis of work-related factors in mental health services reveals a concerning scenario of physical, emotional, and mental strain among professionals.

1. Introduction

The social precariousness of work generates complex dynamics that manifest in precarious working and employment conditions, characterized by persistent feelings of insecurity and vulnerability among workers, particularly related to the risk of unemployment. This situation is driven by multiple factors, including fragile forms of entry into the labor market, social inequalities, increased work intensity, outsourcing, lack of job security, and multiple occupational exposures to health risks. Long working hours, lack of autonomy, task repetitiveness, and monotony also contribute to such precariousness [1,2].

These transformations in the labor landscape have led to significant changes in the healthcare field, especially concerning production processes, professional profiles, and working conditions. The changes brought about by the Brazilian Psychiatric Reform (BPR) sought to overcome the precariousness of work in mental healthcare settings. However, recent setbacks and counter-reforms have introduced new challenges and impacts on workers [3,4].

In this context, mental healthcare has come to encompass not only technical and procedural aspects but also emotional, ethical, ideological, and political dimensions. Thus, in daily practice, healthcare workers and professionals involved in mental healthcare face a transition from an institutionalized model to a psychosocial model [3,4]. Among these professionals, the nursing staff is the most extensively involved, traversing all aspects of this transformation scenario and its implications for mental healthcare. In Brazil, out of 3.5 million health sector workers, approximately 1.7 million (around 50%) are nursing professionals. This category maintains the closest contact with patients in care processes, reinforcing the notion of transversal engagement, which consequently increases susceptibility to mental health disorders [5,6].

Therefore, factors related to organizational conditions, job demands, and the competencies of workers and professionals in mental health services—as well as cultural, social, and personal characteristics embedded in the work environment—are health determinants that can negatively affect well-being. Within this context, a literal distinction arises between ‘workers’ and ‘professionals’: while all professionals are workers performing duties in a specific area of expertise, usually attained through formal education, training, and practical experience, the term ‘worker’ is broader and includes anyone engaged in labor activity, regardless of their level of specialization or formality [7].

Timely monitoring and interventions regarding these work characteristics are essential for creating conditions that support the development of a satisfactory and fulfilling occupational identity and performance [8]. Epidemiological studies in the field of occupational health have highlighted the correlation between work organization characteristics and mental disorders [9]. Regarding workers and professionals in mental health services, significant gaps remain in both understanding the problem and identifying and addressing the factors contributing to these conditions. Workers affected by Work-Related Mental Disorders (WRMDs) may experience irritability, insomnia, fatigue, memory lapses, difficulty concentrating, and reduced physical and intellectual performance, as well as somatic complaints, discouragement, anxiety, depersonalization, and decreased productivity and job satisfaction [8,10,11,12].

From a perspective aimed at understanding the workers’ dynamics and the feelings of suffering and pleasure derived from the work environment, two main categories can be identified: the organizational structure, working conditions, and relationships; and the worker’s subjective engagement, including defensive strategies and spaces for collective discussion. These elements are directly related to experiences of pleasure and discomfort at work. The relationship between job demands and defense mechanisms against their psychological effects are crucial points in the psychodynamic approach to work, highlighting labor organization as a potentially destabilizing factor for the mental health of workers, including those in mental health services [13,14].

It is widely acknowledged that the work environment has a direct impact on workers’ health. Changes in the organization and processes of work have contributed to increased rates of illness among health professionals in recent years [10,11]. From this perspective, research can expand and update scientific knowledge on the subject, providing essential data for the implementation of occupational health policies—particularly for nursing workers—with a focus on improving working conditions, reducing exposure to environmental and psychosocial hazards, and ensuring protective measures for those working in mental health services. Accordingly, this review aims to map the existing literature on work-related factors and consequences that contribute to the illness of workers in mental health services.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a scoping review study, for which ethical approval by a Research Ethics Committee involving human participants was not required. This study was conducted as a scoping review rather than a systematic review. Scoping reviews are designed to map the existing literature, summarize key findings, and identify knowledge gaps, whereas systematic reviews focus on answering specific research questions and often evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. Given the exploratory nature of our study and the diversity of study designs, populations, and outcomes, a scoping review was considered the most appropriate method to provide a comprehensive overview and guide future research.

The aim was to gather the existing literature on the topic, summarize the data, and identify gaps in the current body of knowledge. To guide and support this study, the assumptions of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual and the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation were adopted, see Supplementary Materials. The review protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework [15,16].

The review question was as follows: What work-related factors contribute to the illness of workers in mental health services? The PCC acronym was used (P: Population = workers in mental health services; C: Concept/phenomenon of interest = work-related factors that cause illness; and C: Context = mental health services).

The search strategy was carried out in three stages: an initial limited search in Medline and the Virtual Health Library (VHL) to identify the main concepts related to the research topic and apply them to the research question; listing of terms/descriptors to be used in the search strategy, with predefined use of Boolean operators such as AND and OR; and a manual search of the references from selected articles to identify studies not retrieved through the initial database strategy.

Searches were conducted in the following electronic databases: National Library of Medicine (PubMed); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Virtual Health Library (VHL); Web of Science (WOS); Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO); Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS); and Embase.

For gray literature, the Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (BDTD) was consulted. Table 1 presents the descriptors used in developing the search strategy, which was initially created in PubMed and later adapted to the indexing structure of each database.

Table 1.

Descriptors used in the search strategy for population, phenomenon of interest, and context, 2024.

The searches were conducted between 25 February and 29 April 2024, without language restrictions; however, the majority of the studies identified were in English. Studies in other languages, such as Spanish and Portuguese, were also included when titles and abstracts were understandable in English or translated using automated translation tools. No studies in Japanese, Korean, or other languages outside English, Portuguese, or Spanish were identified in the final selection. Of the 28 studies included, 22 were in English, 4 in Portuguese, and 2 in Spanish.

Database searches were carried out simultaneously by two researchers, who followed the same order of descriptor use and Boolean combinations across each database and subsequently compared their results. To ensure comprehensive coverage, all databases were accessed via the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) journal portal.

The following types of studies were considered eligible: opinion articles, reviews, case studies, quasi-experimental studies, randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, and qualitative studies that addressed work-related factors and consequences contributing to the illness of workers in mental health services. Exclusion criteria included incomplete documents, duplicates, and studies that did not present work-related factors potentially associated with worker illness.

After the searches were completed in both databases and gray literature sources, duplicate articles were removed using Rayyan® software, version 1.0 (Cambridge, MA, USA). Next, titles and abstracts were screened based on the established eligibility criteria. Studies deemed suitable were included for full-text review and considered for the final selection of the review literature.

In the event of disagreements between reviewers, a third reviewer was consulted to resolve the conflict. Data extraction was conducted using an Excel spreadsheet to organize the most relevant findings for structuring and grouping the literature. Extracted data included: Authors; Year/Country; Method/Design; Objective; Population; Setting; Related factors; and Consequences.

Data were presented both textually and visually through a narrative synthesis, followed by a discussion contextualizing the findings in relation to the study’s specific objectives. These objectives were to identify work-related factors contributing to the illness of mental health professionals, categorize the associated consequences, and map gaps in the current literature to address the guiding research question.

3. Results

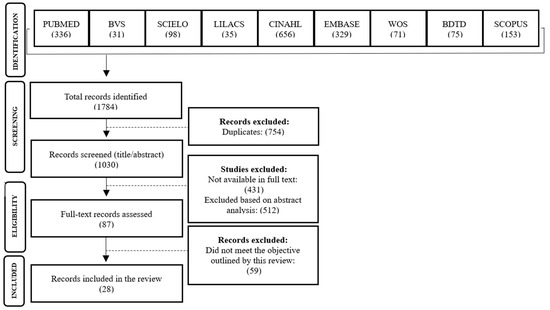

The search process initially identified 1748 records, of which 754 were duplicates. A total of 1030 articles were included for initial screening. Following a second screening, 431 records were excluded due to lack of full-text availability, and 512 were excluded based on title and abstract analysis. Of the remaining 87 articles, 28 met the eligibility criteria and addressed the proposed objectives, and were thus included in the final sample of this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process, 2024.

The studies were conducted in different years and countries, with a significant predominance of research originating from Brazil [8,12,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Regarding the years of publication, they range from 2006 to 2024, including studies carried out in Switzerland [37], Israel [38,39], Iran [40,41], and Belgium [42]. The study settings described in the articles encompass various types of mental health services, covering a range of contexts and regions. Notably, multiple types and locations of Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS) are represented, including CAPS I, II, III, AD, and CAPSi, from cities in Brazil’s northeast—such as Campina Grande, in the state of Paraíba—to the south, such as Foz do Iguaçu, in the state of Paraná. In addition, the studies include psychiatric inpatient units in public and private hospitals [26,28,30,33,34,37,40,41,42], psychiatric teaching hospitals [31], mental health centers in Israel [38,39], Iran [41,42], and Belgium [42], as well as specialized services for the care of individuals who use alcohol and other drugs [17,35] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methodological Summary of Included Studies, 2024.

The predominance of Brazilian studies in this review reflects the relevance and significant scientific production in the field of mental health in Brazil, particularly after the psychiatric reform, which stimulated research on working conditions and the health of professionals in community-based services such as CAPS. International publications were included to broaden the comparative analysis; however, their number was smaller due to the specificity of the topic in the Brazilian context.

Regarding the study populations, participants included physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists, administrative staff, physical educators, pharmacists, physiotherapists, speech therapists, caregivers, security guards, and general services workers. Sample sizes varied considerably, ranging from small groups of 6 workers to large studies involving up to 4464 professionals. In terms of study designs, quantitative investigations were more predominant, particularly those with cross-sectional designs [8,19,21,28,29,33,34,37,38,39,40,42]. Qualitative studies were also prominent, employing exploratory and descriptive approaches [17,18,20,22,23,24,25,26,30,31,36]. Additionally, some studies utilized mixed-methods approaches [12,32,35] and reviews of the literature [27].

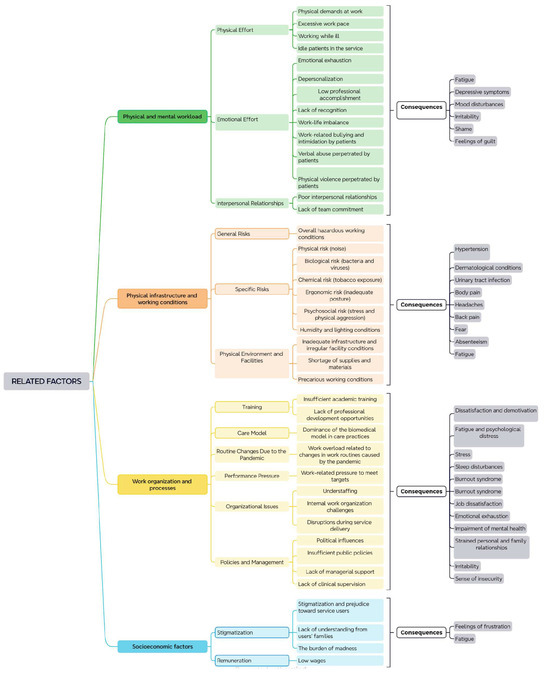

Based on the interpretative analysis of Figure 2, it is possible to characterize the work-related factors that contribute to the illness of workers in mental health services, as well as their possible consequences. Work overload was identified as a critical factor affecting these workers, further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The constant pressure to meet targets and the excessive workload [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] resulted in fatigue and psychological distress [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], stress [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], sleep disturbances [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], and Burnout syndrome [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], with job dissatisfaction as a major consequence [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Figure 2.

Work-related factors contributing to the illness of mental health service workers and their consequences, 2024.

Inadequate physical infrastructure and irregularities in facilities [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], combined with a shortage of supplies and materials [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,22,26,27,31,33,36], were described as having a negative impact on the quality of the work environment. Work organization, understaffing [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], lack of managerial support [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], and insufficient clinical supervision [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] contribute to feelings of insecurity [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] and irritability [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] among professionals. These conditions negatively affect both overall and mental health [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], as well as interpersonal relationships in the workplace, and even personal and family life [23].

Physical demands [35,36,37] and excessive work pace [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] were also evident in the findings, resulting in emotional exhaustion [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], depersonalization [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], low professional accomplishment [21], sadness [12,23], feelings of frustration [8,12,18], failure [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], and powerlessness [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Interpersonal relationship problems [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], such as lack of team commitment [8], lead to fatigue [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34], depressive symptoms [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], mood swings [23], shame [38], and feelings of guilt [36].

Physical risks (e.g., noise) [28], biological risks (e.g., bacteria and viruses) [28,29,30], chemical risks (e.g., tobacco) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], and ergonomic risks (e.g., poor posture) [28,29,30] were prevalent. In addition, psychosocial risks (e.g., stress and physical aggression) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] and precarious working conditions [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] contributed to hypertension [21], dermatological diseases [21], urinary tract infections [21], body, head, and back pain [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], fear [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], absenteeism [22], and fatigue [23].

Insufficient academic training [31] and lack of professional development opportunities [31], combined with the predominance of biomedical care practices [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], generate dissatisfaction and demotivation [23,25]. Stigmatization and prejudice toward service users [18,19,20,21,22], as well as a lack of understanding from users’ families [32], further intensify mental suffering [26], resulting in shame [38] and alcohol abuse [30].

Low wages [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] and lack of recognition [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] are additional factors that contribute to feelings of frustration [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] and fatigue [23], especially among professionals with longer tenure in the service [40].

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the work-related factors that contribute to the illness of workers in mental health services, understanding that the health of healthcare workers requires reflective practices on the conditions and organization of work within these services. The workplace in mental health services can simultaneously function as a source of professional fulfillment and as a context for stress and suffering, depending on organizational and relational dynamics.

Although this study did not focus on a single professional category, the results highlighted nursing as the most frequently examined profession in research on workers’ mental health in mental health settings. The working conditions of nursing teams emerge as a critical issue in Brazil’s health system, characterized by an insufficient and inadequately trained workforce in mental healthcare settings—an issue closely related to nursing education in Brazil [31,43].

These problems negatively impact the health of nursing professionals, compromising the reception and care of users of health services, and affecting the quality and effectiveness of care delivery [44].

Despite the significant advances brought by the Brazilian psychiatric reform—such as the promotion of deinstitutionalization and the implementation of community- and outpatient-based actions—the country continues to face major challenges beyond workforce shortages. In recent years, the scenario has been marked by funding restrictions and the Unified Health System’s (SUS) difficulty in absorbing new demands, undermining the continued progress of the reform [45,46].

These structural and financial constraints have led to long working hours, insufficient rest, and continued pressure to meet high service demands without adequate support, which contributes to mental exhaustion, anxiety, and other mental health conditions. This creates a vicious cycle in which professionals become ill and leave the workforce, worsening the shortage of human resources—factors identified in this review that significantly affect the lives and health of mental health workers [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

In this context, the findings suggest that organizational structures and understaffed teams directly affect the provision of comprehensive care to users and their families. The findings of study [47] support the idea that mental illness not only impacts healthcare workers themselves, but also the family and social context in which they are embedded. Therefore, the organizational structure requires teams to adopt a broad, integrated approach that includes collaboration with different components of the healthcare network, through mental health matrix support and clinical supervision—identified in this review as an associated factor due to its lack of consistent implementation.

The physical infrastructure of psychosocial care in Brazil shows that many services were established in buildings without the necessary adaptations to meet the needs of users, families, and healthcare teams. In contrast, it is known that a healthcare facility that adheres to design principles of therapeutic environments becomes more welcoming, helping to strengthen and renew the patient’s relationship with the institution. These environments cease to be controlling and restrictive and instead promote conditions that enhance autonomy for individuals in their care processes [48].

Regarding workplace risks and safety, this review highlights studies that point to biological, chemical, and physical risks. Examples include biological risks associated with potential infections caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. These risks are present across mental healthcare settings, both community-based and hospital-based, and can compromise workers’ physical and psychological well-being [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

The lack of an organizational culture focused on protecting workers in Brazilian mental health services is concerning. Without a system that prioritizes safety and well-being, work environments can become harmful, jeopardizing both the quality of services and workers’ health. Although there are laws and policies intended to protect workers, their implementation is often insufficient—due to lack of resources, weak enforcement, or a lack of genuine institutional commitment [31,43].

Studies show that long working hours reduce professional satisfaction across sectors and are linked to declining motivation over time. This can lead to personal dissatisfaction, which in turn undermines motivation and affects self-esteem. Some studies indicate that civil servants working in public institutions report greater satisfaction than workers in the private sector, likely due to the job security enjoyed by public employees compared to those on less secure contracts (e.g., temporary or outsourced workers) [19].

Mental health professionals’ job satisfaction is strongly influenced by the conditions in which services are delivered. A lack of alignment between service logistics and user needs was reported as a significant concern. Frequent interruptions during patient care, staff shortages, and delays in acquiring materials are problematic. These findings are supported by another study that also identified dissatisfaction due to service interruptions, resource scarcity, and organizational issues [18,19].

The implications for practice highlight the importance of an integrated approach to addressing the factors that contribute to illness among mental health service workers. Excessive workloads, performance pressure, and inadequate facilities must be strategically addressed to improve workplace conditions. Measures such as reviewing organizational processes, enhancing professional training, and improving physical and material resources are essential to mitigate the negative impacts identified.

Following the methodological framework of this scoping review, no statistical weighting or quantitative synthesis of prevalence or incidence rates was performed. Instead, to enhance interpretability, stressors were organized according to their recurrence and emphasis across the included studies. Primary stressors most frequently reported and consistently emphasized were work overload, understaffing, and long working hours. Secondary stressors that were recurrent but less prominent were inadequate infrastructure, exposure to occupational risks (physical, biological, chemical, and ergonomic), and insufficient supplies. Tertiary stressors less consistently highlighted or context-dependent were limited training opportunities and insufficient managerial support. This frequency-based categorization clarifies the relative salience of each factor in the literature while remaining aligned with the methodological boundaries of a scoping review.

Another relevant aspect concerns the terminology used to describe the workforce. In the Brazilian literature, the term worker (trabalhador) was often applied broadly to all individuals engaged in mental health services, regardless of their professional training or clinical responsibilities. In contrast, international studies more commonly used the term professional to designate licensed staff providing direct clinical care. This heterogeneity in descriptors limited the possibility of consistently distinguishing between clinically trained professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, psychologists) and other service workers (e.g., administrative or support staff). While differences in educational background and role may influence how individuals experience and manage stressors, the available data did not allow for systematic stratification by these characteristics.

In addition to the findings discussed, this review identified several gaps in the literature. While factors such as workload, staff shortages, and exposure to physical and biological risks have been examined, there is limited research on the long-term psychological effects of work-related stress, differences in occupational risks across mental health service settings, and the effectiveness of interventions aimed at mitigating worker illness. Moreover, organizational culture, team dynamics, and socio-cultural factors remain underexplored, limiting understanding of how these elements influence the well-being of mental health professionals. Addressing these gaps through future research is essential to develop targeted strategies for improving workplace conditions, enhancing professional satisfaction, and ultimately safeguarding both workers’ health and the quality of care provided to users.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that precarious working conditions in mental health services have a significant impact on the mental health of professionals and the quality of care provided. Excessive workloads, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of professional training are critical factors that must be addressed to improve the work environment and, consequently, the effectiveness of mental health services.

It is essential that occupational health policies consider mental health workers not only in structural and financial terms but also through the lens of an integrated approach that prioritizes worker safety and well-being. Strategic measures such as the revision of organizational processes, expansion of professional training, and improvement of physical and material conditions are crucial for mitigating the negative impacts identified and fostering a healthier and more productive work environment.

The study also highlights the importance of continuing the psychiatric reform and adapting work practices to new demands, ensuring that mental health services can effectively and humanely meet the needs of both professionals and service users.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22121822/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; methodology, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; software, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; validation, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; formal analysis, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; investigation, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; resources, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; data curation, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; writing—review and editing, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; visualization, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; supervision, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; project administration, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C.; funding acquisition, J.M.B.d.G., J.A.d.S.F., E.M.N.P., R.D.d.S., J.B.d.S.B.N. and E.F.d.O.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Araújo, T.M.; Palma, T.F.; Araújo, N.C. Work-related Mental Health Surveillance in Brazil: Characteristics, difficulties, and challenges. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2017, 22, 3235–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.A. Classe trabalhadora, precarização e resistência no Brasil da pandemia. Em Pauta 2021, 19, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, K.L.; Beck, C.L.C.; Perrone, C.M.; Coelho, A.P.F.; Vasconcelos, R.O. Mobilização subjetiva de trabalhadores de um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial Álcool e Drogas: Intervenção em saúde do trabalhador por meio da clínica psicodinâmica do trabalho. Rev. Bras. Saúde Ocup. 2018, 43 (Suppl. S1), e12s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, F.C.D.; Silva, R.M.; Siqueira, D.F.; Pretto, C.R.; Müller, F.E.; Freitas, E.O. Produção científica acerca da saúde de trabalhadores de serviços de saúde mental. Rev. Recien 2022, 12, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocruz. Pesquisa Inédita Traça Perfil da Enfermagem no Brasil. 2024. Available online: https://portal.fiocruz.br/noticia/pesquisa-inedita-traca-perfil-da-enfermagem-no-brasil (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio (EPSJV). Piso Salarial da Enfermagem: Os Entraves na Garantia de Direitos para a Categoria. 2024. Available online: https://www.epsjv.fiocruz.br/noticias/reportagem/piso-salarial-da-enfermagem-os-entraves-na-garantia-de-direitos-para-a-categoria (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Neves, D.R.; Nascimento, R.P.; Felix Júnior, M.S.; Silva, F.A.; Andrade, R.O.B. Meaning and Significance of work: A review of articles published in journals associated with the Scientific Periodicals Electronic Library. Cad. EBAPE.BR 2018, 16, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santos, Y.L.Q.; Navarro, V.L.; Elias, M.A. A precarização do trabalho e a saúde dos profissionais de um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial. Cad. Psicol. Soc. Trab. 2023, 26, e190114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, J.A.; Nobre, S.V.; Silva, C.F.; Lima, I.C.S.; Domingos, J.E.P.; Bezerra, A.M. Satisfação e impacto do trabalho em serviços de saúde mental de um município de referência. Saúde (Santa Maria) 2021, 47, e63691. [Google Scholar]

- Centenaro, A.P.F.C.; Silveira, A.; Colet, C.F.; Kleibert, K.R.U.; Santos, G.K. Potentials and challenges of Psychosocial Care Centersin the voice of health workers. Rev. Enferm. UFSM 2022, 12, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, F.A.M.; Barbosa, G.C.; Corrente, J.E.; Komuro, J.E.; Papini, S.J. Satisfaction and burden in mental health professionals’ performance. Esc. Anna Nery 2021, 25, e20200309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, I.C.S.; Sampaio, J.J.C.; Ferreira Júnior, A.R. Work and illness risks in Territorial Psychosocial Care: Implications for mental health care management. Saúde Debate 2023, 47, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.A.; Silva, D.R.A.; Ibiapina, A.R.S.; Silva, J.S. Mental illness and its relationship with work: A study of workers with mental disorders. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2018, 16, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aciole, G.G.; Pedro, M.J. Sobre a saúde de quem trabalha em saúde: Revendo afinidades entre a psicodinâmica do trabalho e a saúde coletiva. Saúde Debate 2019, 43, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. 2015; 24p, Available online: https://reben.com.br/revista/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Scoping.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Santos, L.R.; Barbosa, G.C.; Silva, J.C.M.C.; Oliveira, M.A.F. Mental health workers’ life experience during the coronavirus pandemic. Rev. Enferm. UFSM 2022, 12, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhs, M.; Olschowsky, A.; Ferraz, L. Suffering and defense in work in a mental health care servisse. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J.F.; Santos, A.M.; Primo, L.S.; Silva, M.R.S.; Domingues, E.S.; Moreira, F.P.; Wiener, C.; Oses, J.P. Job satisfaction and work overload among mental health nurses in the south of Brazil. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2019, 24, 2593–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clementino, F.S.; Miranda, F.A.N.; Martiniano, C.S.; Marcolino, E.C.; Pessoa Júnior, J.M.; Fernandes, N.M.S. Satisfaction and work overload evaluation of employees’ of Psychosocial Care Centers. J. Res. Fundam. Care Online 2018, 10, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, A.B.; De Lucca, S.R. Burnout Syndrome in Mental Health Workers at Psychosocial Care Centers. Mundo Saúde 2021, 45, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamente, V.; Onocko-Campos, R. Processo de trabalho e sofrimento institucional em Centros de Atenção Psicossocial Infanto-juvenis (Capsi): Uma pesquisa-intervenção junto a trabalhadores. Rev. Latinoam. Psicopatol. Fundam. 2022, 25, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Y.G.; Oliveira, J.S.A.; Chaves, A.E.P.; Clementino, F.S.; Araújo, M.S.; Medeiros, S.M. Psychic burden development related to nursing work in Psychosocial Care Centers. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74 (Suppl. S3), e20200114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, V.; Hennington, E.A. A saúde mental dos profissionais de um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial. Physis 2012, 22, 983–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzener, C.H. Avaliação dos Fatores de Sofrimento e Prazer no Trabalho em um Centro Atenção Psicossocial. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008; 107p. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, C.N. Sob o Peso dos Grilhões: Um Estudo Sobre a Psicodinâmica do Trabalho em um Hospital Psiquiátrico Público. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009; 275p. [Google Scholar]

- Ramminger, T. Cada CAPS é um CAPS: A Importância dos Saberes Investidos na Atividade para o Desenvolvimento do Trabalho em Saúde Mental. Ph.D. Thesis, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; 226p. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, M.A.; Marziale, M.H.P. Occupational risks and illness among mental health Workers. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2014, 27, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, D.; Legay, L.F.; Abelha, L. Satisfação com o trabalho e impacto causado nos profissionais de serviço de saúde mental. Rev. Saúde Pública 2007, 41, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Carvalho, M.B.; Felli, V.E.A. O trabalho de enfermagem psiquiátrica e os problemas de saúde dos trabalhadores. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2006, 14, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scozzafave, M.C.S.; Leal, L.A.; Soares, M.I.; Henriques, S.H. Psychosocial risks related to the nurse in the psychiatric hospital and management strategies. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, F.F.S.; Costa, S.F.G.; Batista, P.S.S.; Carvalho, M.A.P.; Lordão, A.V.; Batista, J.B.V. Overload in health workers in a psychiatric hospital complex in the northeast of Brazil. Esc. Anna Nery 2021, 25, e20210018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, K.H.J.F.; Gonçalves, T.S.; Silva, M.B.; Soares, E.C.F.; Nogueira, M.L.F.; Zeitoune, R.C.G. Risks of illness in the work of the nursing team in a psychiatric hospital. Rev. Latibo Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.L.C. Satisfação e sobrecarga de trabalho entre técnicos de enfermagem de hospitais psiquiátricos. Rev. Port. Enferm. Saúde Ment. 2017, 17, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.A.S.; Pereira, M.O.; Oliveira, M.A.F.; Pinho, P.H.; Gonçalves, R.M.D.A. Work process and its impact on mental health nursing professionals. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2015, 28, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guimarães, J.M.X.; Jorge, M.S.B.; Assis, M.M.A. (In)satisfação com o trabalho em saúde mental: Um estudo em Centros de Atenção Psicossocial. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2011, 16, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, K.A.; Voirol, C.; Kunz, S.; Gurtner, A.; Renggli, F.; Juvet, T.; Golz, C. Factors associated with health professionals’ stress reactions, job satisfaction, intention to leave and health-related outcomes in acute care, rehabilitation and psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes and home care organisations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assuline, S.Z.; Savitsky, B.; Wilf-Miron, R.; Kagan, I. Social shaming and bullying of mental health staff by patients: A survey in a mental health centre. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itzhaki, M.; Peles-Bortz, A.; Kostistsky, H.; Barnoy, D.; Filshtinsky, V.; Bluvstein, I. Exposure of mental health nurses to violence associated with job stress, life satisfaction, staff resilience, and post-traumatic growth. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, M.S.; Valizadeh, N.; Dehghan, N.; Shalbafan, M. Workload and Burnout Among Nurses of a Public Referral Psychiatric Hospital in Tehran, Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Iran Med. Counc. 2022, 5, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtari, Z.; Farhady, E.; Khodaee, S. Relationship between job burnout and work performance in a sample of Iranian mental health staff. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2009, 12, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, V.P.; Clarke, S.; Willems, R.; Mondelaers, M. Nurse practice environment, workload, burnout, job outcomes, and quality of care in psychiatric hospitals: A structural equation model approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerich, B.F.; Campos, O.R. Formação para o trabalho em Saúde Mental: Reflexões a partir das concepções de Sujeito, Coletivo e Instituição. Interface 2019, 23, e170521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.L.D.; Begnini, M.; Prigol, A.C. Implicações da síndrome de burnout na saúde mental dos enfermeiros da atenção primária à saúde. Rev. Port. Enferm. Saúde Ment. 2023, 30, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athié, K.; Amarante, P. Financiamento da saúde mental pública: Estudo do caso do Rio de Janeiro (2019 a 2022). Saúde Debate 2024, 48, e8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onocko, C.R.T. Saúde mental no Brasil: Avanços, retrocessos e desafios. Cad. Saúde Pública 2019, 35, e00156119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazan, L.F.; Fortes, S.L.C.L.; Junior, C.K.R.D. Apoio Matricial em Saúde Mental: Revisão narrativa do uso dos conceitos horizontalidade e supervisão e suas implicações nas práticas. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2020, 25, 3251–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, P.R.C.B.; Mazzaia, M.C. A percepção de enfermeiros acerca da ambiência na saúde mental/Perception of nurses about the environment in mental health. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2019, 2, 2322–2324. Available online: https://ojs.brazilianjournals.com.br/ojs/index.php/BJHR/article/view/1694 (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Marziale, M.H.; Rocha, F.L.; Robazzi, M.L.; Cenzi, C.M.; Santos, H.E.C.; Trovó, M.E. Organizational influence on the occurrence of work accidents involving exposure to biological material. Rev. Latinoam. Enferm. 2013, 21, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).