Weathering the STORM and Forecasting Equity for Older Black Women: Expanding Social Determinants of Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

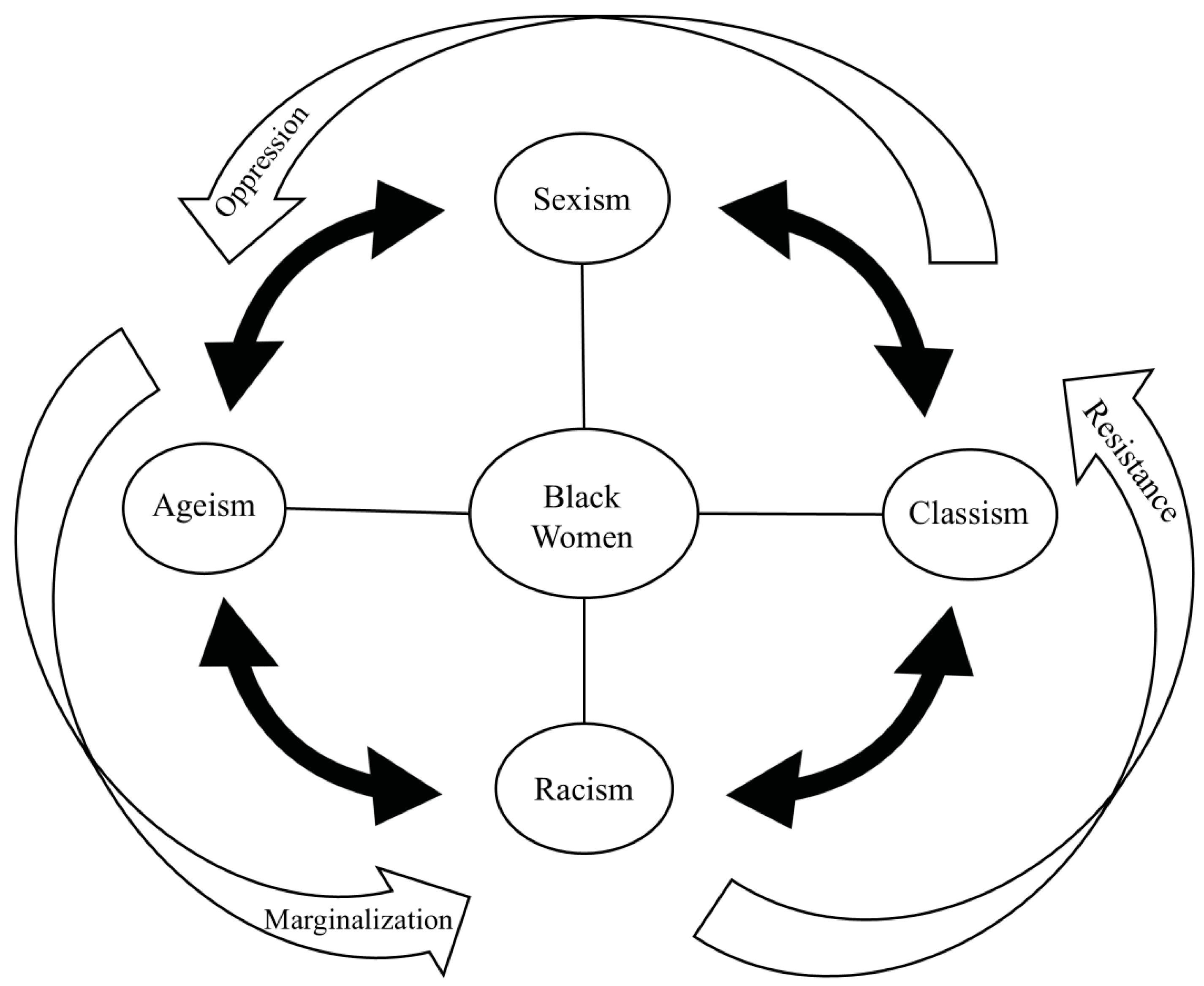

2. Background: A Structural, Intersectional View of Aging

3. Interrelated Systems with Structural Roots

4. Age, Work, Retirement: Modern-Day Implications of Historical Marginalization

5. Contemporary Feminization of Poverty Among Black Women

6. Informal Caregiving: Work Never Ceases

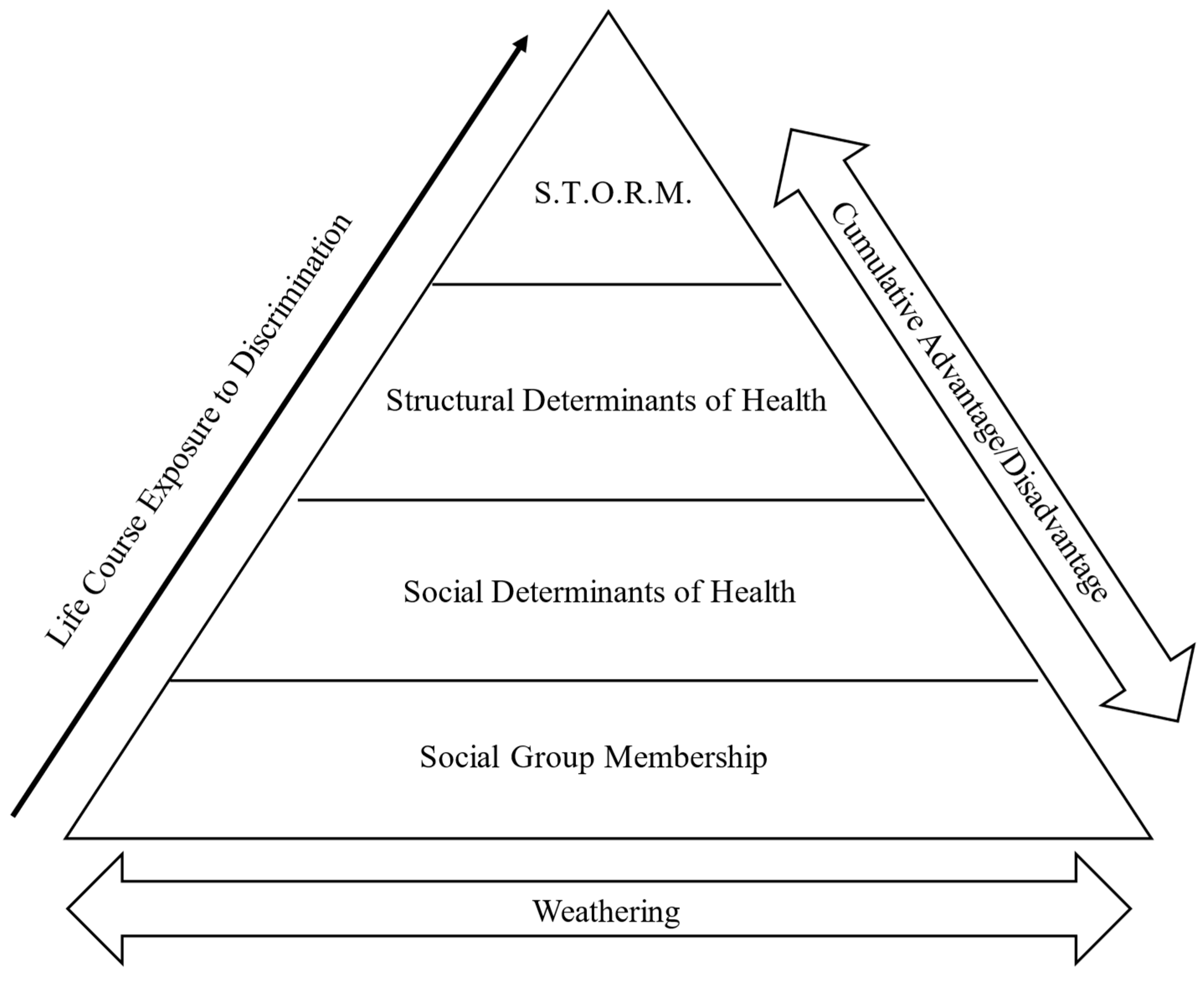

7. Gendered Racism in Health Care Across the Life Course

8. Cumulative Consequences: Forecasting a Perfect STORM

9. The Weathering Hypothesis: A Response to Structural Marginalization and Resilience as Scar Tissue

If you’re Black, working hard and playing by the rules can be part of what kills you.[64] (p. 3)

Given that resilience is a disproportionate expectation of the marginalized, a more appropriate framing for it in the administration of healthcare is a marker of health inequities; an adverse event in response to structural harm that manifests within the individual. We argue that we should reframe “resilience as treatment” to “resilience as scar tissue…”[77] (p. 340)

10. Towards Aging Equity: Structural Intersectionality Across the Lifespan

11. STORM: A Conceptual Framework for Centering Older Black Women’s Experiences

12. Implications and Future Directions

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krieger, N. Epidemiology and the Web of Causation: Has Anyone Seen the Spider? Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 39, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social Determinants of Health Inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, C.M.; Portacolone, E. What is new with old? What old age teaches us about inequality and stratification. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ciaula, A.; Portincasa, P. The Environment as a Determinant of Successful Aging or Frailty. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 188, 111244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, T.W.; Hung, W.W.; Unroe, K.T.; Brown, T.R.; Furman, C.D.; Jih, J.; Karani, R.; Mulhausen, P.; Nápoles, A.M.; Nnodim, J.O.; et al. Exploring the Intersection of Structural Racism and Ageism in Healthcare. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 3366–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, H.O.; Taylor, R.J. Older Black Americans During COVID-19: Race and Age Double Jeopardy. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, A.T.; Zhu, Y.; De Fries, C.M.; Dunbar, A.Z.; Trujillo, M.; Hasche, L. A Phenomenological, Intersectional Understanding of Coping with Ageism and Racism Among Older Adults. J. Aging Stud. 2023, 67, 101186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, A.J.; Mullings, L. (Eds.) Gender, Race, Class, & Health: Intersectional Approaches; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, I.; Grenier, A.; Brotman, S.; Koehn, S. Understanding the Experiences of Racialized Older People Through an Intersectional Life Course Perspective. J. Aging Stud. 2017, 41, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, C.L.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Critical Race Theory, Race Equity, and Public Health: Toward Antiracism Praxis. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100 (Suppl. S1), S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillipson, C. Placing Ethnicity at the Centre of Studies of Later Life: Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Challenges. Ageing Soc. 2014, 35, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, R.J.; Bruce, M.A.; Wilder, T.; Jones, H.P.; Tobin, C.T.; Norris, K.C. Health Disparities at the Intersection of Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Downstream Biological Pathways. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S. Expanding the Gerontological Imagination on Ethnicity: Conceptual and Theoretical Perspectives. Ageing Soc. 2014, 35, 935–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L. Reconstructing the Landscape of Health Disparities Research: Promoting Dialogue and Collaboration Between Feminist Intersectional and Biomedical Paradigms. In Gender, Race, Class, & Health: Intersectional Approaches; Schulz, A.J., Mullings, L., Eds.; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 21–59. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, C.L. Critical gerontology and the new political economy of aging. In Critical Gerontology: Perspectives from Political and Moral Economy; Baywood Press: Amityville, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dressel, P.; Minkler, M.; Yen, I. Social Context of Health: Gender, Race, Class, And Aging: Advances and Opportunities. Int. J. Health Serv. 1997, 27, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versey, H.S.; Gibbons, J. Aging Alone (While Black): Living Alone, Loneliness, and Health Among Older Black Women. Gerontologist 2024, 65, gnae175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. Intersectionality: An Underutilized but Essential Theoretical Framework for Social Psychology; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—An Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A.; Croff, R.; Glover, C.M.; Jackson, J.D.; Resendez, J.; Perez, A.; Zuelsdorff, M.; Green-Harris, G.; Manly, J.J. Traversing the Aging Research and Health Equity Divide: Toward Intersectional Frameworks of Research Justice and Participation. Gerontologist 2021, 62, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.R. Advancing the Study of Health Inequality: Fundamental Causes as Systems of Exposure. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins-Jackson, P.B.; Chantarat, T.; Bailey, Z.D.; Ponce, N.A. Measuring Structural Racism: A Guide for Epidemiologists and Other Health Researchers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.R. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Residential Segregation, and Beyond—Lessons for Studying Structural Racism and Health. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 5, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Jackson, J.; Faison, N. The work and retirement experiences of aging Black Americans. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 26, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, D.V.; Weller, C.E. Retirement Inequality by Race and Ethnicity. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2021, 31, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viceisza, A.; Calhoun, A.; Lee, G. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Retirement Outcomes: Impacts of Outreach. Rev. Black Political Econ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viceisza, A. Black Women’s Retirement Preparedness and Wealth. Urban Institute. 2022. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/Black%20Women%E2%80%99s%20Retirement%20Preparedness%20and%20Wealth.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Bluethenthal, C. The Disproportionate Burden of Eviction on Black Women. American Progress. 2023. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-disproportionate-burden-of-eviction-on-black-women/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Curchin, E. Student Loan Debt Is Common Across All Race and Gender Groups, Especially for Black Women. Center for Economic and Policy Research. Available online: https://cepr.net/publications/student-loan-debt-is-common-across-all-race-and-gender-groups-especially-for-black-women/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Hayman, G.; Mason, J. How The Wage Gap Persists Beyond Working Years, Especially for Black and Latina Women. National Partnership for Women & Families. 17 November 2023. Available online: https://nationalpartnership.org/wage-gap-persists-beyond-working-years-especially-black-latina-women/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Adkins-Jackson, P.B.; Tejera, C.H.; Cotton-Samuel, D.; Foster, C.L.; Brown, L.L.; Watson, K.T.; Ford, T.N.; Bragg, T.; Wondimu, B.B.; Manly, J.J. ‘Rest of the Folks Are Tired and Weary’: The Impact of Historical Lynchings on Biological and Cognitive Health for Older Adults Racialized as Black. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 364, 117537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, N.; Chen, J.T.; Coull, B.A.; Beckfield, J.; Kiang, M.V.; Waterman, P.D. Jim Crow and Premature Mortality Among the US Black and White Population, 1960–2009. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezeala-Harrison, F. Black Feminization of Poverty: Evidence From the U.S. Cross-regional Data. J. Dev. Areas 2010, 44, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.D.; Houseworth, C.A. The Widening Black-White Wage Gap Among Women. Labour 2017, 31, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, M. How Do Wage Gaps Affect Black Women’s Wealth Attainment, and Where Do Expenditures Fit In? Urban Institute. 2023. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-do-wage-gaps-affect-black-womens-wealth-attainment-and-where-do (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Dozier, R. The Declining Relative Status of Black Women Workers, 1980–2002. Soc. Forces 2010, 88, 1833–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, L.; Yadon, N. Intersectional Wealth Gaps: Contemporary and Historical Trends in Wealth Stratification Among Single Households by Race and Gender. Soc. Curr. 2022, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearby, R. When Equal Pay Is Not Enough: The Influence of Employment Discrimination on Health Disparities. Public Health Rep. 2019, 134, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, G.L. The Golden Years: African American Women and Retirement. UW Tacoma Digital Commons. 2004. Available online: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/socialwork_pub/369/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Versey, H.S. Caregiving and Women’s Health: Toward an Intersectional Approach. Womens Health Issues 2017, 27, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- John, D.C. Disparities for Women and Minorities in Retirement Saving. Brookings, 1 September 2010. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/disparities-for-women-and-minorities-in-retirement-saving/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Brady, S.; Patskanick, T.; Coughlin, J.F. An Intersectional Approach to Understanding the Psychological Health Effects of Combining Work and Parental Caregiving. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2024, 79, gbae042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennon, S.M.; Anderson, J.G.; Epps, F.; Rose, K.M. ‘It’s Just Part of Life’: African American Daughters Caring For Parents With Dementia. J. Women Aging 2018, 32, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Coats, J.; Croston, M.; Motley, R.O.; Thompson, V.S.; James, A.S.; Johnson, L.P. ‘We Need a Little Strength as Well’: Examining the Social Context of Informal Caregivers for Black Women With Breast Cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 342, 116528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, C.; Mor, V. Disparities in the Prevalence of Unmet Needs and Their Consequences Among Black and White Older Adults. J. Aging Health 2017, 30, 1427–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.C.; Allen, S.M. Targeting Risk for Unmet Need: Not Enough Help Versus No Help at All. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2001, 56, S302–S310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, E.A. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKoy, J. Racism, Sexism, and the Crisis of Black Women’s Health. Boston University, 1 December 2023. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/articles/2023/racism-sexism-and-the-crisis-of-black-womens-health/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Logan, R.G.; Daley, E.M.; Vamos, C.A.; Louis-Jacques, A.; Marhefka, S.L. ‘When Is Health Care Actually Going to Be Care?’ the Lived Experience of Family Planning Care Among Young Black Women. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.N.; Erving, C.L.; Tobin, C.S.T. Are Distressed Black Women Also Depressed? Implications for a Mental Health Paradox. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 10, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.N.; Kaatz, A.; Carnes, M. Physicians and Implicit Bias: How Doctors May Unwittingly Perpetuate Health Care Disparities. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, K.A.; Berlin, J.A.; Harless, W.; Kerner, J.F.; Sistrunk, S.; Gersh, B.J.; Dubé, R.; Taleghani, C.K.; Burke, J.E.; Williams, S.; et al. The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, A.; Randall, J. ‘We’re Not Taken Seriously’: Describing The Experiences of Perceived Discrimination in Medical Settings For Black Women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 10, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastik, J.; Bowleg, L.; Versey, H.S. Moving multiple categories research into closer conversation with intersectionality. under review.

- Funk, C. Black Americans’ Views About Health Disparities, Experiences With Health Care. Pew Research Center. 22 July 2024. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/04/07/black-americans-views-about-health-disparities-experiences-with-health-care/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Elder, G.H., Jr. Age Differentiation and the Life Course. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1975, 1, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannefer, D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, S327–S337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugarten, B.L.; Moore, J.W.; Lowe, J.C. Age Norms, Age Constraints, and Adult Socialization. Am. J. Sociol. 1965, 70, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.-K.; Klopack, E.; Zhang, Y.; Gibbons, F.X.; Beach, S.R.H. Racial Discrimination, Inflammation, and Chronic Illness Among African American Women at Midlife: Support for the Weathering Perspective. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 8, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethn. Dis. 1992, 2, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.W.; Dilworth-Anderson, P.; Goodwin, P.Y. Caregiver Role Strain: The Contribution of Multiple Roles and Available Resources in African-American Women. Aging Ment. Health 2003, 7, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.K.; Beach, S.R.H.; Philibert, R.A.; Cutrona, C.E.; Gibbons, F.X.; Barr, A. Economic Hardship and Biological Weathering: The Epigenetics of Aging in a U.S. Sample of Black Women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 150, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A. The False Narrative of Coping with Toxic Stress. Harvard Public Health Magazine, 5 June 2024. Available online: https://harvardpublichealth.org/equity/arline-geronimus-public-health-book-on-structural-racism-effects/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Geronimus, A.T.; Hicken, M.T.; Pearson, J.A.; Seashols, S.J.; Brown, K.L.; Cruz, T.D. Do US Black Women Experience Stress-Related Accelerated Biological Aging? Hum. Nat. 2010, 21, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.-K.; Beach, S.R.H.; Barr, A.B.; Simons, L.G.; Gibbons, F.X.; Philibert, R.A. Discrimination, Segregation, and Chronic Inflammation: Testing the Weathering Explanation for the Poor Health of Black Americans. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1993–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.-K.; Klopack, E.; Beach, S.R.H.; Gibbons, F.X.; Philibert, R.A. The Effects of Social Adversity, Discrimination, and Health Risk Behaviors on the Accelerated Aging of African Americans: Further Support for the Weathering Hypothesis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 282, 113169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.; Iyer, K. Internalized Racism, Hopelessness, and Physical Functioning Among Black American Men and Women: A Cross-sectional Test of Two ‘Weathering’ Hypotheses. Stigma Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombé, C.L. Superwoman Schema: African American Women’s Views on Stress, Strength, and Health. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Chae, D.H.; Price, M.M.; Powell, W.; Steed, T.C.; Black, A.R.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Marquez-Magaña, L.; Woods-Giscombe, C.L. Racial Discrimination, the Superwoman Schema, and Allostatic Load: Exploring an Integrative Stress-coping Model Among African American Women. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Cardemil, E.V.; Overstreet, N.M.; Hunter, C.D.; Woods-Giscombé, C.L. Association Between Superwoman Schema, Depression, and Resilience: The Mediating Role of Social Isolation and Gendered Racial Centrality. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2022, 30, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, A.K.; Hayman, L.L. Unveiling the Strong Black Woman Schema—Evolution and Impact: A Systematic Review. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2024, 33, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombe, C.; Robinson, M.N.; Carthon, D.; Devane-Johnson, S.; Corbie-Smith, G. Superwoman Schema, Stigma, Spirituality, and Culturally Sensitive Providers: Factors Influencing African American Women’s Use of Mental Health Services. J. Best Pract. Health Prof. Divers. Res. Educ. Policy 2016, 9, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste, D.-L.; McDonald, L.R.; LeFevre, F.; Russell, N.; Baptiste, K.-J.; Paul, L.; Procks, D.; Josiah, N.; Akomah, J.; Owusu, B. Black Women as Superwomen; Health Disparities and the Cost of Strength: A Discursive Paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.C.T.; Anderson, R.E.; Gaskin-Wasson, A.L.; Sawyer, B.A.; Applewhite, K.; Metzger, I.W. From ‘Crib to Coffin’: Navigating Coping From Racism-related Stress Throughout the Lifespan of Black Americans. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erving, C.L.; McKinnon, I.I.; Van Dyke, M.E.; Murden, R.; Udaipuria, S.; Vaccarino, V.; Moore, R.H.; Booker, B.; Lewis, T.T. Superwoman Schema and self-rated health in black women: Is socioeconomic status a moderator? Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 340, 116445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslovic, B.; Lett, E. Resilience Is an Adverse Event: A Critical Discussion of Resilience Theory in Health Services Research and Public Health. Community Health Equity Res. Policy 2023, 44, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson-Singleton, N.N.; Spivey, B.N.; Harrison, E.G.; Nelson, T.; Lewis, J.A. Double-edged sword or outright harmful? Associations between Strong Black Woman schema and resilience, self-efficacy, and flourishing. Sex Roles 2024, 90, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.D.; Dufault, S.M.; Spears, E.C.; Chae, D.H.; Woods-Giscombe, C.L.; Allen, A.M. Superwoman Schema and John Henryism Among African American Women: An Intersectional Perspective on Coping With Racism. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 316, 115070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.M.; Thomas, M.D.; Michaels, E.K.; Reeves, A.N.; Okoye, U.; Price, M.M.; Hasson, R.E.; Syme, S.L.; Chae, D.H. Racial Discrimination, Educational Attainment, and Biological Dysregulation Among Midlife African American Women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 99, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, N.E.; Stewart, J. Health Disparities Across the Lifespan: Meaning, Methods, and Mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colen, C.G. Addressing racial disparities in health using life course perspectives. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2011, 8, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T. Black/White Differences in the Relationship of Maternal Age to Birthweight: A Population-based Test of the Weathering Hypothesis. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 42, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T. To Mitigate, Resist, or Undo: Addressing Structural Influences on the Health of Urban Populations. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.A.; Buchanan, N.T.; Mingo, C.A.; Roker, R.; Brown, C.S. Reconceptualizing Successful Aging Among Black Women and the Relevance of the Strong Black Woman Archetype. Gerontologist 2014, 55, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Eibach, R.P. Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-Group Identities. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, E.; Asabor, E.; Beltrán, S.; Cannon, A.M.; Arah, O.A. Conceptualizing, Contextualizing, and Operationalizing Race in Quantitative Health Sciences Research. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 314–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, J. ROOTT’s Theoretical Framework of the Web of Causation Between Structural and Social Determinants of Health and Wellness. Restoring Our Own Through Transformation. 2016. Available online: https://www.roottrj.org/web-causation (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Collins, P.H. Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M.; Castro, F.G.; Strycker, L.A.; Toobert, D.J. Cultural Adaptations of Behavioral Health Interventions: A Progress Report. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 81, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versey, H.S. Photovoice: A method to interrogate positionality and critical reflexivity. Qual. Rep. 2024, 29, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, S.; Shea, D.G.; Reyes, A.M. Cumulative Advantage, Cumulative Disadvantage, and Evolving Patterns of Late-Life Inequality. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Versey, H.S.; Van Vleet, S. Weathering the STORM and Forecasting Equity for Older Black Women: Expanding Social Determinants of Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121777

Versey HS, Van Vleet S. Weathering the STORM and Forecasting Equity for Older Black Women: Expanding Social Determinants of Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121777

Chicago/Turabian StyleVersey, H. Shellae, and Samuel Van Vleet. 2025. "Weathering the STORM and Forecasting Equity for Older Black Women: Expanding Social Determinants of Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121777

APA StyleVersey, H. S., & Van Vleet, S. (2025). Weathering the STORM and Forecasting Equity for Older Black Women: Expanding Social Determinants of Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121777