Abstract

Globally, there are around 1.3 billion cigarette consumers, indicating it to be the second highest risk factor for early death and morbidity. Meanwhile, psychological therapy offers tools based on its different models and techniques, which can contribute to smoking cessation. In this context, this study gathers scientific evidence to identify psychological therapies that can be used to reduce cigarette consumption. A systematic review of controlled clinical studies was conducted, implementing the PRISMA methodology. Search queries were performed with terms extracted from MESH (Medical Subject Headings) and DECS (Descriptors in Health Sciences). Subsequently, the search was queried in the scientific databases of Medline/PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest, and PsycNet, with subsequent verification of methodological quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists. The selected documents revealed that cognitive behavioral therapy prevails due to its use and effectiveness in seven publications (25%). The cognitive approach with mindfulness therapy is found in 4 publications (14%), the transtheoretical model with motivational therapy in 4 publications (14%), brief psychological therapy in 3 publications (10%), and the remaining 10 documents (37%) correspond with others. Intervention studies refer to cognitive behavioral therapy as the most used in reducing cigarette consumption; in terms of the duration of abstinence, scientific evidence shows beneficial effects with short-term reduction.

1. Introduction

Current use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco is associated with an increased risk of mortality in general, especially in daily smokers [1]. According to Méndez, Alshanqeety, and Warner (2013), if no additional policies are implemented and current smoking initiation and cessation rates persist, global adult smoking prevalence is estimated to be 22.7% in 2020 and 22.0% in 2030, with a total of 872 million smokers [2].

According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) report, more than 1.3 billion people consume cigarettes worldwide [3,4]. In Switzerland, smoking was the most common modifiable cardiovascular risk factor among young adults hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes, affecting 71.4% of them. Although there has been a significant decrease in active smoking among these patients between 2000 and 2019, it still affected approximately two-thirds of them in 2019 [5].

Smoking is associated with an increased risk of more than 25 preventable diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease (CAD), and several types of cancer, including lung, laryngeal, mouth, and throat cancers [6]. Smoking is, therefore, directly linked to increased morbidity and mortality, including chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and CAD due to atherosclerosis and high blood pressure [7,8]. According to the WHO [9,10], smoking is the second most common cause of premature death, causing around 8,000,000 deaths per year.

Tobacco, being a legal consumer product, contains components that, when burned, generate numerous toxic substances that negatively affect various organs and systems of the human body, impacting the life expectancy of smokers [11]. Tobacco smoke is composed of a gaseous phase and a particulate phase containing more than 4000 identified substances, such as carbon monoxide, nicotine, and tars [12]. During the combustion of cigarettes, substances such as hydrocyanic acid, formic aldehyde, lead, arsenic, and ammonia, radioactive elements such as uranium, benzene, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and acetaldehyde are created, enhancing the addictive effect of nicotine, the main addictive component of tobacco [13].

Carbon monoxide, a common substance in tobacco, impacts oxygenation and blood vessels, while nicotine generates psychological and physical dependence by binding to specific brain receptors [14]. Moreover, tobacco tars contain carcinogens and irritants that damage the respiratory system and other organs, such as polonium-210, a carcinogenic substance present in tobacco smoke due to the absorption of radium-226 by tobacco leaves [15]. Exposure to these harmful substances impacts health depending on the amount, duration and form of exposure, the presence of other chemicals, as well as individual habits and personal characteristics [16].

Another essential component in understanding smoking is nicotine, an essential component extracted from tobacco leaves, considered addictive due to its ability to generate a transient release of endorphins in the brain’s reward circuits via dopamine [17]. This phenomenon produces a momentary feeling of euphoria when it enters the bloodstream, although its comparatively brief effect requires further consumption of the substance to maintain the desired effect [18]. Regular nicotine use affects the central nervous system, influencing learning, the ability to handle stress, and self-control [19]. When cigarette smoke reaches the lungs, nicotine is rapidly absorbed and reaches the brain within seconds, being a determining factor in the addiction process due to its pharmacokinetic properties [20]. This rapid access to the central nervous system makes it difficult to quit smoking immediately, so an evidence-based therapeutic approach is required to manage withdrawal symptoms [21].

Currently, there are different types of smoking cessation therapies, e.g., pharmacotherapy [22], nicotine patch therapy, and interventions from a psychological perspective (cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT] [23], motivational interviewing [24], mindfulness, telephone support, quit lines, online services, and social networks) [25,26].

Various conventional psychological therapies are mentioned in the literature, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, and mindfulness. CBT focuses on changing negative thought patterns, providing strategies for adaptive coping with smoking-related thoughts and behaviors [27]. Motivational interviewing, on the other hand, focuses on empathic collaboration and ambivalence, seeking to strengthen intrinsic motivation to quit smoking, recognizing the complexity of the process [28]. Several studies [29,30] showed promising results when using motivational interviewing as a pre-treatment tool for smoking cessation. On the other hand, mindfulness, based on meditation techniques, focuses on increasing awareness of urges to smoke, facilitating the conscious management of these urges by highlighting the importance of the mind–body connection in overcoming tobacco use [31]. Recent research highlights the effectiveness of social networks, helplines, and online services as a means of providing ongoing support [32,33]. Based on the above, the present systematic review aims to compile scientific evidence on the psychological therapeutic actions used in smoking reduction.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted following the PRISMA method as a guide to collect updated information in a transparent manner, revealing key findings about the review [34]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. The scope of the systematic review was established by the AMCPLT strategy to perform a descriptive analysis of the scientific literature, not including a meta-analysis. The acronym corresponds to six components of the research question: (A) Adjective; (M) Measurement; (C) Condition; (P) Population; (L) Place; (T) Time [35].

- Review questions

What therapeutic actions or psychological treatments are most used for the reduction of habitual cigarette smoking?

Based on the establishment of the questions, the inclusion and exclusion criteria to be considered for the selection of the information were defined, obtained from consultation databases using search equations with descriptors examined in health thesauri to determine the key words (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Thesaurus terms.

Table 2.

Databases with the applied search query.

- Inclusion criteria

As we delved into this review, we maintained certain criteria in mind while selecting studies. Firstly, we prioritized research grounded in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), particularly those incorporating elements of psychological treatments in their interventions. Furthermore, it was essential that participants were adults, over the age of 18, with a history of regular nicotine use. Additionally, we imposed a temporal boundary on our selection, concentrating on studies published within the last five years (2017–2021).

- Exclusion criteria

In our approach, we also established specific criteria to exclude certain studies from our analysis. Consequently, we eliminated research that was not based on experimental methods and those lacking psychological interventions in their methodology. Additionally, we disregarded publications dated before 2017, those unrelated to smoking habits, and any texts without full access.

- Information sources

To conduct our information search, we utilized six renowned scientific bibliographic databases: ProQuest, Science Direct, Scopus, Medline/PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and PsycNet.

- Search strategy

To accurately identify the studies and formulate the search equations, we meticulously selected the appropriate terms. We utilized descriptors in Health Sciences, such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and DECS (Health Sciences Descriptors), focusing on the following keywords: “Psychological therapy”, “Smoking”, and “Nicotine dependence” (see Table 1).

To construct the search equations effectively, we employed Boolean operators, including “OR”, “AND”, and “NOT”. These operators were skillfully adapted to suit the format of the various databases we utilized (see Table 2).

Subsequently, we initiated our search using the equations crafted for the previously selected databases. It is noteworthy that some databases accommodated a broad array of terms, while others imposed limits on the number of terms at the outset of a search, leading to varied results. After eliminating duplicate publications that failed to meet our eligibility criteria, we independently reviewed the titles and abstracts. During this phase, studies deemed irrelevant based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded. Any disagreements regarding the suitability of articles were resolved through thorough discussion. Below, you will find a summary of our filtering process, applied to each criterion in the publications, determining the number of studies selected for inclusion (Table 3).

Table 3.

Filters applied.

- Data extraction process

Following the initial selection, we meticulously prepared a record table in Excel, which was independently populated by the authors. In this table, we carefully documented the key elements from each of the selected studies, ensuring a detailed and organized compilation of data.

- Characteristics

Initially, we embarked on classifying the interventions and the corresponding descriptions of the treatment therapies. In this process, we compared these interventions between the control and experimental groups. This comparison considered various characteristics of the therapies, such as the underlying model, techniques employed (if applicable), and whether the intervention was conducted in groups or individually. Additionally, we investigated specific details regarding the therapy sessions, including the number of sessions, their frequency, and the duration of each session. The effectiveness and benefits of these therapies, the intervention protocol, randomization processes, and the characteristics of the participants were also thoroughly examined.

Furthermore, we identified and documented the qualifications and characteristics of the therapists and outcome evaluators. The follow-up protocols post-intervention and the findings of the studies were also meticulously recorded. In instances where we encountered missing or unclear data, we proactively reached out through email to request additional information, thereby ensuring the comprehensiveness and accuracy of our data collection process.

- Risk of bias assessment of individual studies

The approach we adopted for assessing the risk of bias in the included studies was grounded in the critical appraisal tools provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute. Specifically, we utilized their checklist for randomized controlled trials to determine the reliability level of each study. This instrument was applied independently to the checklists, ensuring a thorough and unbiased evaluation. Following this individual assessment, a comparison was made through a consensus-building process, as outlined in reference [27].

- Selection and analysis

The initial phase of our study selection involved a preliminary screening based on inclusion criteria, focusing on characteristics of the population, study type, and publication year. Following this, we embarked on a more detailed process to determine the eligibility of studies. This involved tabulating their characteristics, which allowed for a comprehensive comparison. During this comparison, we rigorously verified each study’s compliance with the inclusion criteria.

This meticulous process was guided by the criteria set forth in the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for randomized controlled trials. The checklist includes a range of questions covering key aspects of trial design and execution: randomization methods for assigning participants to treatment groups, the blinding of participants, therapists, and outcome evaluators to treatment allocation, ensuring baseline similarity, verifying complete follow-up, and accounting for dropouts, employing appropriate statistical analysis, and evaluating the adequacy of the trial design. Additionally, it includes queries regarding the potential standard deviation in randomized controlled trials, particularly focusing on individual randomization and parallel groups.

In the final stage of study selection, we extracted and collated relevant sections addressing our research question. These data were then systematically integrated into two distinct tables for clarity and ease of reference. The first table, titled “Selected Studies”, presents general information on the selected studies. The second focuses on therapeutic interventions and is titled “Intervention Characteristics”.

- Assessment of publication bias

This process was performed based on the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist criteria for randomized controlled trials [36].

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Studies

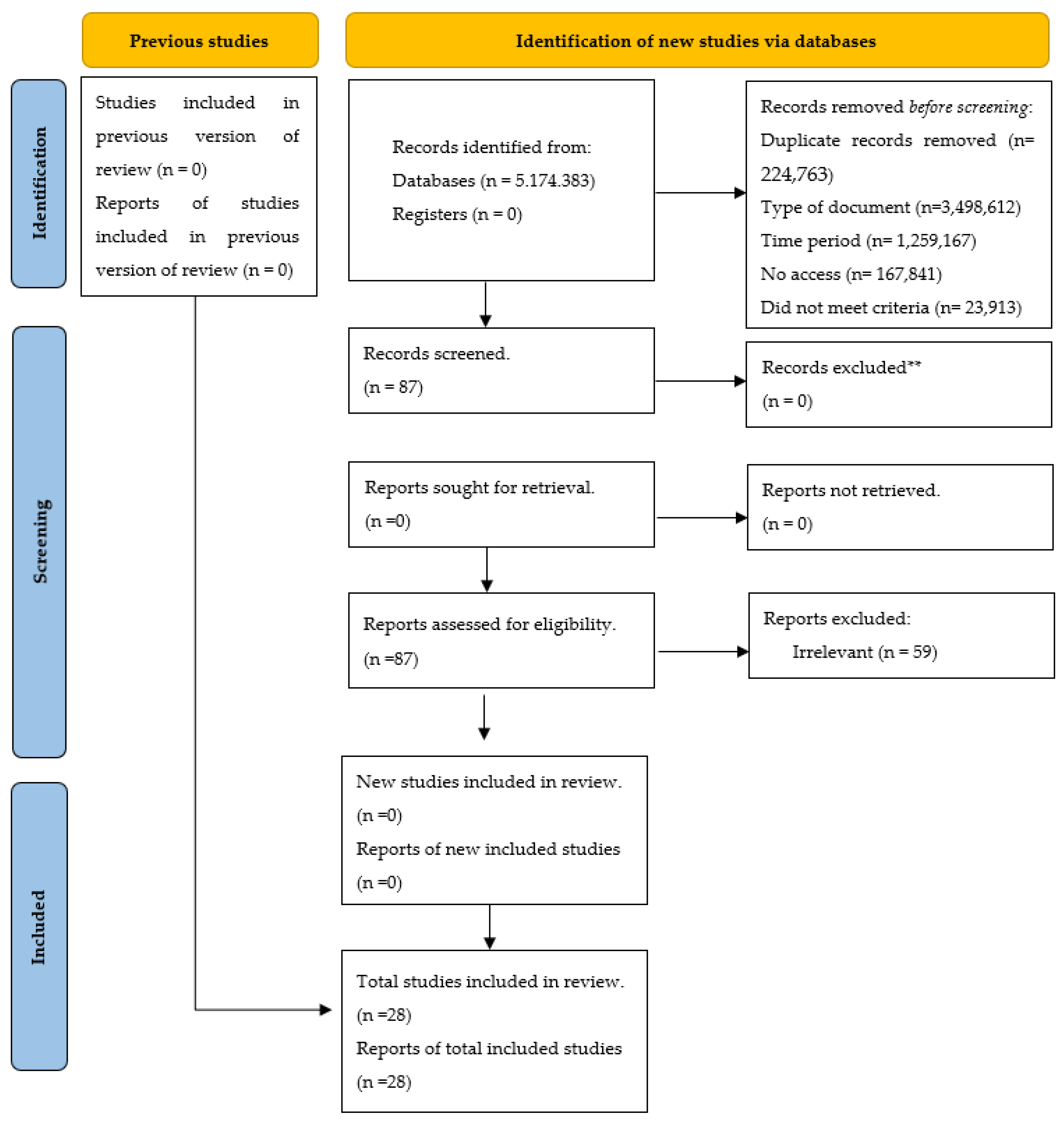

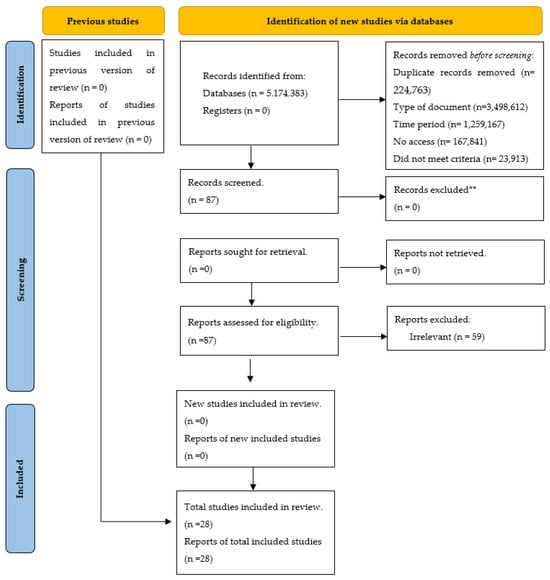

The results of the search and selection process, from the records found in the review to the inclusion of the studies, are presented below (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for updated systematic reviews, which includes searches of databases [34].

Our search process commenced with the initial step of determining the “Total number of articles found”. This figure represents the aggregate results yielded by the initial search across various databases. At this juncture, we had solely employed the search equation without the integration of any exclusion filters. In addressing the “Document Type”, our focus was narrowed to texts specifically categorized as articles. This delineation led to the exclusion of books, essays, and other such formats, allowing us to concentrate on sources that are more pertinent and specific. The “Time Period” was intentionally confined to the years between 2017 and 2022. The section pertaining to “Incomplete/duplicate texts” covers two significant concerns. Firstly, we omitted texts that were incomplete, whether due to access limitations or their status as ongoing research proposals. Secondly, we removed articles that were either duplicates or had undergone subsequent updates. The category “No access” pertains to articles that preclude the viewing of the complete document. Regarding “Noncompliance with criteria”, texts that failed to meet our predefined exclusion criteria were eliminated. Ultimately, the “Total number of selected articles” indicates the final tally of articles that successfully passed through all filters and criteria and were, thus, deemed suitable for inclusion in our systematic review.

From an initial pool of 23,913 studies, a rigorous process of mechanical filtering was applied, significantly reducing the number of documents. A subsequent detailed review of the texts further narrowed the selection to 28 documents that met our established criteria. Throughout this process, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) emerged as a prominent theme, both in terms of quantity and effectiveness, being featured in seven publications (25%). Other notable approaches included the cognitive approach and mindfulness therapy, each found in four publications (14%), as well as the transtheoretical model with motivational therapy. Brief psychological therapy was mentioned in 3 publications (10%), and the remaining 10 papers (37%) explored a variety of interventions, each offering unique insights into the challenge of smoking cessation. During study selection, it was ascertained that CBT is prevalently used due to its efficacy in enhancing adherence to psychological treatments for smoking and in reducing abstinence among habitual cigarette users.

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

As highlighted in the preceding section, our meticulous selection process culminated in the identification of 28 studies (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Selected studies.

3.3. Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

In assessing the risk of bias in individual studies, the Johanna Briggs checklist, a widely recognized tool for the assessment of randomized controlled trials, was applied. After detailed analysis, most studies were classified as having a medium-low risk of bias.

3.4. Analysis of the Treatments

After careful selection and assessment of the risk of bias of each study, a detailed analysis of each paper was conducted. This involved classifying the studies according to descriptions of the interventions and comparisons between treatments and control groups. Specific details of each intervention were examined, such as the number of sessions, their duration and frequency. In addition, we compared how each technique addressed smoking cessation, considering participants and their attributes related to group assignment, methods of measuring smoking, and the presence of pre- and post-testing. The synthesis also included an overview of the therapists and evaluators involved, as well as the follow-up procedures during and after the intervention, and the outcomes of the study, i.e., the efficacy of the therapies.

Of the studies reviewed, seven incorporated cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) due to its effectiveness in modifying dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors, focusing on the problem and highlighting practical application. In the context of smoking cessation, CBT helps individuals to restructure their thinking patterns, adopt healthier responses, and develop beneficial behaviors. The other studies we analyzed employed a variety of interventions, some of which were combined approaches. For example, Ref. [40] integrated motivational intervention, games, story therapy, and reading and writing therapy. We also encountered mindfulness therapy [45], Allen Carr’s Easyway therapy [41], and cognitive bias modification [62,63].

3.5. Techniques Used in the Studies

In this systematic review, we observed a diverse array of intervention techniques across the selected studies, with a notable emphasis on those grounded in the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model. Notably, cognitive restructuring emerged as a key technique, employed in two of the studies. This approach focuses on identifying, confronting, and altering irrational and negative thought patterns that fuel addiction to smoking.

Additionally, we noticed a significant incorporation of various training methods derived from the CBT model. These included self-modification, mindfulness, impulse tolerance training, and emotional regulation. Emotional regulation, which appeared in two of the studies, involves teaching individuals to manage their immediate emotional states—whether that means maintaining, enhancing, or suppressing them—with the goal of achieving emotional equilibrium.

Group counseling sessions, used in two of the studies, provided a platform for participants to build relationships and offer mutual support, aiding them in tackling the everyday challenges associated with smoking. Techniques for stimulus control were also noted in our review.

Motivation played a central role in the implementation of techniques such as motivational interviewing, playful interventions, and motivational interventions, often combined with story therapy, as well as reading and writing therapy. Psychoeducation was identified as technique for effectively managing dependency, withdrawal symptoms, stimulus control, self-regulation, mood management, coping skills, and relapse prevention. Techniques specifically targeting mood management, including those focused on anger and stress, were also employed. One study highlighted the potential effectiveness of a CBT-based smoking reduction program that integrates various clinical strategies.

3.6. Characteristics of the Sessions

Our systematic review revealed a wide range of techniques, each with differences in duration, style of intervention, and the impacts observed in the corresponding studies. In Table 5, we carefully highlight the key aspects that stand out as particularly relevant to each therapeutic approach.

Table 5.

Intervention characteristics.

3.7. Evaluators of the Results

During the systematic review conducted, a recurring problem was observed in many of the studies: a lack of clear information about the outcome assessors, which made it difficult to assess the risk of bias and discussions about blinding in the study process. In addition, a significant challenge highlighted in these experiments was a high dropout rate among participants. This dropout appears to be associated with difficulties experienced during abstinence and other symptoms that arise in the context of smoking cessation efforts [44,61].

4. Discussion

Systematic review of the scientific literature shows that educational processes on habituation and the implications of smoking, including its effects over different time periods and its important health consequences, often fail to have a significant impact on smokers [38,56].

It is important to consider that smoking represents a repetitive action that can become almost automatic, which complicates the smoking cessation process and the need to address it in a comprehensive manner [47]. In addition to the act of smoking itself, various environmental factors, such as the taste and smell of cigarettes, the sensation of holding a cigarette, and the longevity of these habits, often link smoking to positive experiences in the mind of the smoker [45].

From the first contact of nicotine with neurons, an arousal state is triggered that neurons remember, adapting their responses to subsequent nicotine exposure. This interaction leads to a dependence characterized by the neurons’ desire to re-experience this state of arousal [53]. As a result, this systematic review evidences a high dropout rate among participants in these studies, often due to difficulties associated with withdrawal and other symptoms related to the effects of nicotine [47].

The systematic review showed the most frequent limitations experienced when developing controlled clinical trials (RCTs), including clarity in the identification of therapists and evaluators, as well as transparency in blinding processes. This weakness impacts current smoking cessation strategies that minimal outcomes, such as occasional smoking or sporadic abstinence, have negligible effects on overall health outcomes, such as mortality and morbidity [44,46]. Restrictions on how RCTs are reported affected the review process, impacting the selection of studies was the occasional lack of clarity or omission of critical information in titles and abstracts, such as types of treatment, a situation that could cause confusion or misinterpretations of results.

Following this, it is important to critically evaluate the quality and generalizability of studies supporting smoking cessation recommendations and interventions [64,65]. In the RCTs studied, it was found that the psychological therapies and psychological approaches most implemented in controlled trials are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral therapy and psychosocial support, and other treatments, with financial incentives, video games, and combinations of procedures. It is worth highlighting that a relevant aspect of this review is the influence of participants’ willingness or determination to quit smoking on their commitment to treatment and persistence at follow-up [45].

Most of the studies, were based on psychological treatments aimed at reducing withdrawal symptoms in habitual cigarette users and performed pre- and post-intervention measurements through different means of verification with biomarkers (expired CO) or biochemically in blood and saliva sampling; however, the studies do not report results on long-term abstinence. Authors such as Jhanjee, Lal, Mishra [58] and Zakharova and Ibatov [56] reported variable abstinence rates depending on the type of treatment and duration of follow-up.

In the case of interventions with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), abstinence was maintained until the fourth week, with 22% in the PTSD-PTSD group and 13% in the non-PTSD group [60]. In turn, Laude et al. [46] compared prolonged versus nonprolonged CBT for smoking cessation. No significant differences in abstinence were observed at 52 and 104 weeks [46].

Combined treatments refer use of cognitive behavioral therapy—CBT, with mindfulness [48], home visits [62], and psychosocial support and telephone counseling [38]. Interventions appear to have positive effects on smoking cessation, with abstinence rates above 50% at 6 months [57]. Frings et al. [40] compared the Easyway program with a specialized pharmacological and behavioral support service; the combination of behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy, in particular NRT and varenicline, are effective in promoting smoking cessation [66].

Regarding the use of financial incentives, its efficacy is presented in decreasing the severity of withdrawal symptoms [37] in time no longer than one-year post-intervention [47]. Video-based interventions such as those conducted by Bloom et al. [50] QuitBet platform, and Scholten et al. [49] with the go/no-go training game for smoking cessation in young adults. Neither baseline nor endpoint measures were reported [49].

Comparing the selected studies, it was found that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most widely used method to reduce tobacco consumption. It is relevant to note that CBT encompasses a variety of techniques with significant efficacy in the reviewed studies. The most needed effects that were not addressed in the reviewed experiments are the rate of reduction in cigarette consumption, health-related quality of life, severity and duration of withdrawal symptoms, self-efficacy to quit, relapse, changes in attitudes and beliefs about smoking, and adherence to smoking cessation treatment [67].

The studies reviewed in this systematic review emphasize the immediate benefits of smoking cessation interventions, but also highlight a key concern: the long-term efficacy of these treatments remains uncertain, as the sustainability of abstinence and the possibility of relapse are major challenges [20]. Follow-up periods in these studies vary, ranging from brief check-ups to more comprehensive and continuous follow-up that includes in-person and telephone interactions, as well as various medical assessments. One study in particular extended the duration of its follow-up, providing a more robust dataset and underlining the importance of long-term observation for more reliable results, but aspects such as self-efficacy to quit, health-related quality of life, and improved family relationships are aspects that could increase motivation to quit [68].

5. Conclusions

In our quest to answer the central question of our systematic review—“What psychological therapies are effective in reducing smoking?”—we embarked on a thorough examination of relevant literature. Our search spanned six esteemed scientific bibliographic databases, leading to the selection of 28 studies that not only aligned with our precise inclusion criteria, but also passed the rigorous assessment based on the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists [36] (see Supplementary Material). Our systematic review methodology was meticulously aligned with the standards set by the PRISMA 2020 Declaration, an essential guide for the publication of systematic reviews [34].

The results obtained from the analysis revealed the existing psychological treatments which address smoking and also contribute to treatment adherence to be cognitive behavioral treatments, interventions that implement the use of mobile technology, mindfulness, and brief and motivational interventions. The psychological treatment that has shown efficacy in reducing smoking withdrawal symptoms is CBT, which is characterized by its structured approach and its focus on modifying cognitive and behavioral patterns associated with smoking.

The evidence gathered suggests that it is important to address smoking abstinence through preventive interventions, namely effective and personalized treatments that provide individuals with tools and resources that are tailored to their particular needs, promote well-being, enhance the quality of life of individuals, and attenuate the burden of tobacco-associated diseases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph21060753/s1, Attachment S1: JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses.

Author Contributions

A.N.S.-G. contributed to the data collection and writing of the article; J.A.C.-U. collaborated with the concept and design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the document; L.C.-C. collaborated with the concept and design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the document; S.-M.C.-S. contributed to the concept or design study; V.B. contributed to the concept or design study; D.R.-P. contributed to the concept of the study or design and to the writing of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This systematic review article is a product funded within the framework of the “call for strengthening projects in execution of STI in health sciences with young talent and regional impact” of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MINCIENCIAS), in agreement with the Simón Bolívar University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

A request was made for retrospective registration of the systematic review in PROSPERO, where it was initially verified that there was no systematic review similar to the one proposed. Once this was verified, all items required by PROSPERO were fulfilled for granting the ID registration number: 325082 Title: Psychological therapies for smoking cessation: a systematic review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Research and Innovation Department of Simón Bolívar University, for providing the Management System tools implicit in the process, and the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation of Colombia for financing the required resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACE | Allen Carr’s Easy way |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CS | Cognitive strategy |

| EC | Enhanced care. |

| EST | Enhanced standard treatment. |

| IC | Intensive care |

| MBAT | Mindfulness-based addiction treatment |

| MESH | Medical Subject Headings |

| NRT | Nicotine replacement therapy |

| NT | No treatment |

| SC | Standard Care |

| TAU | Treatment as usual |

| UC | Usual care |

| PHS | Public Health Service |

| MB | Mindfulness-based yogic breathing |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| PP | Point-prevalence |

| DSC | Dual-smoker couples |

| N-O-T | Not-on-Tobacco |

| PA | Physical activity |

| N-O-T+FIT | Module |

| BI | Brief Intervention |

| CI | Intervention Condition |

References

- Inoue-Choi, M.; Shiels, M.S.; McNeel, T.S.; Graubard, B.I.; Hatsukami, D.; Freedman, N.D. Contemporary Associations of Exclusive Cigarette, Cigar, Pipe, and Smokeless Tobacco Use With Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 3, pkz036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, D.; Alshanqeety, O.; Warner, K.E. The potential impact of smoking control policies on future global smoking trends. Tob. Control 2013, 22, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Cigarrillo. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Declaración de la OMS: Consumo de Cigarrillo y COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/11-5-2020-declaracion-oms-consumo-cigarrillo-covid-19 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Mahendiran, T.; Hoepli, A.; Foster-Witassek, F.; Rickli, H.; Roffi, M.; Eberli, F.; Pedrazzini, G.; Jeger, R.; Radovanovic, D.; Fournier, S.; et al. Twenty-year trends in the prevalence of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in young acute coronary syndrome patients hospitalized in Switzerland. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, E.A.; Lowe, K.E.; Make, B.J.; Lynch, D.A.; Kinney, G.L.; Budoff, M.J.; Mao, S.S.; Dyer, D.; Curtis, J.L.; Bowler, R.P.; et al. Identifying smoking-related disease on lung cancer screening CT scans: Increasing the value. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. J. COPD Found. 2019, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, J. Effects of Radiation on the Environment. In Radiation Effects in Polymeric Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kubalek, D.; Serša, G.; Štrok, M.; Benedik, L.; Jeran, Z. Radioactivity of cigarettes and the importance of 210Po and thorium isotopes for radiation dose assessment due to smoking. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 155, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, D.M.; Dybing, E.; Gray, N.; Hecht, S.; Anderson, C.; Sanner, T.; Straif, K. Reducción obligatoria de sustancias tóxicas en el humo del cigarrillo: Una descripción de la propuesta TobReg de la Organización Mundial de la Salud. Control del Tabaco 2008, 17, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülsen, A.; Yigitbas, B.A.; Uslu, B.; Drömann, D.; Kilinc, O. The effect of smoking on COVID-19 symptom severity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulm. Med. 2020, 2020, 7590207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebet, A.; Kibet, J.; Ombaka, L.; Kinyanjui, T. Surface bound radicals, char yield and particulate size from the burning of tobacco cigarette. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, R.; Hertz-Schünemann, R.; Ehlert, S.; Liu, C.; McAdam, K.; Baker, R.; Streibel, T. Highly time-resolved imaging of combustion and pyrolysis product concentrations in solid fuel combustion: NO formation in a burning cigarette. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 1711–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz-Schünemann, R.; Ehlert, S.; Streibel, T.; Liu, C.; McAdam, K.; Baker, R.R.; Zimmermann, R. High-resolution time and spatial imaging of tobacco and its pyrolysis products during a cigarette puff by microprobe sampling photoionisation mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 2293–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.W.; Teesdale-Spittle, P.; Page, R.; Ellenbroek, B.; Truman, P. Biologically Active Compounds Present in Tobacco Smoke: Potential Interactions Between Smoking and Mental Health. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 885489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagà, V.; Gattavecchia, E. Poloniul: Ucigaşul radioactiv din fumul de tutun [Polonium: The radioactive killer from tobacco smoke]. Pneumologia 2008, 57, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Sustancias Químicas Nocivas en los Productos de Cigarrillo. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/es/cancer/causas-del-cancer/cigarrillo-y-cancer/agentescancerigenos-en-los-productos-de-cigarrillo.html (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Roh, S. Scientific Evidence for the Addictiveness of Tobacco and Smoking Cessation in Tobacco Litigation. J. Prev. Med. Public Health=Yebang Uihakhoe Chi 2018, 51, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiton, M.; Diemert, L.M.; Bondy, S.J.; Cohen, J.E.; Fung, M.D.; Zhang, B.R.; Ferrence, R.G. Real-world effectiveness of pharmaceutical smoking cessation aids: Time-varying effects. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Informe de la OMS Sobre la Epidemia Mundial de Tabaquismo. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326072 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Fernández, M.R.V. Efectividad de una Intervención Enfermera Sobre Abordaje al Tabaquismo en Diferentes Servicios de la Red de Salud Mental. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McRobbie, H.; Hajek, P. Effects of rapid smoking on post-cessation urges to smoke. Addiction 2007, 102, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRobbie, H.; Lee, M.; Juniper, Z. Non-nicotine pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation. Respir. Med. 2005, 99, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul-Kader, J.; Airagnes, G.; D’almeida, S.; Limosin, F.; Le Faou, A.L. Les outils du sevrage tabagique en 2018 [Interventions for smoking cessation in 2018]. Rev. Pneumol. Clin. 2018, 74, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, A.; Kano, M.; Sato, T. Motivational interviewing and cognitive behavior therapy for smoking cessation. Nihon Rinsho. Jpn. J. Clin. Med. 2013, 71, 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Borgne, A.; Aubin, H.J.; Berlin, I. Les stratégies thérapeutiques actuelles du sevrage tabagique [Current therapeutic strategies in smoking cessation]. Rev. Prat. 2004, 54, 1883–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Carim-Todd, L.; Mitchell, S.H.; Oken, B.S. Mind-body practices: An alternative, drug-free treatment for smoking cessation? A systematic review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 132, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Puranik, M.P.; Uma, S.R. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy compared with basic health education for tobacco cessation among smokers: A randomized controlled trial. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2020, 18, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, E.I.; Chavarria, J.; Liu, M.; Hedeker, D.; King, A.C. Effects of a brief motivational smoking intervention in non-treatment seeking disadvantaged Black smokers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindson-Hawley, N.; Thompson, T.P.; Begh, R. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3, CD006936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.T.; Cahill, K.; Qin, Y.; Tang, J.L. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 1, CD006936. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfalian, S.; Spears, C.A.; Juliano, L.M. The effects of mindfulness-based yogic breathing on craving, affect, and smoking behavior. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2020, 34, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, K.; Chen, T.A.; Martinez Leal, I.; Correa-Fernández, V.; Obasi, E.M.; Kyburz, B.; Williams, T.; Casey, K.; Brown, H.A.; O’connor, D.P.; et al. Organizational-level moderators impacting tobacco-related knowledge change after tobacco education training in substance use treatment centers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, I. Temporalities of peer support: The role of digital platforms in the ‘living presents’ of mental ill-health. Health Sociol. Rev. 2024, 33, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. PRISMA Flow Diagram. 2020. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Cañón, M.; Buitrago-Gómez, Q. The research question in clinical practice: A guideline for its formulation. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. Engl. Ed. 2018, 47, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Mundt, M.P.; Bak, T.B.; Piper, M.E.; Smith, S.S.; Fraser, D.L.; Fiore, M.C. Financial incentives to Medicaid smokers for engaging tobacco quit line treatment: Maximising return on investment. Tob. Control 2020, 29, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.T.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Vidrine, D.J.; Prokhorov, A.V.; Frank, S.G.; Tahay, P.D.; Houchen, M.E.; Cantor, S.B. Cost-effectiveness analysis of smoking cessation interventions using cell phones in a low-income population. Tob. Control 2019, 28, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vispo, C.; López-Durán, A.; Rodríguez-Cano, R.; Senra, C.; Becoña, E. Treatment completion and anxiety sensitivity effects on smoking cessation outcomes. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peckham, E.; Arundel, C.; Bailey, D.; Brownings, S.; Fairhurst, C.; Heron, P.; Li, J.; Parrott, S.; Gilbody, S. Smoking Cessation Intervention for Severe Mental Ill Health Trial (SCIMITAR+): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frings, D.; Albery, I.; Moss, A.; Brunger, H.; Burghelea, M.; White, S.; Wood, K. Comparison of Allen Carr’s Easyway programme with NHS-standard specialist cessation support: A randomised controlled trial. Addiction 2020, 115, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, M.L.; Rosen, R.L.; Versella, M.V.; Borges, A.; Leyro, T.M. A pilot randomized clinical trial of brief interventions to encourage quit attempts in smokers from socioeconomic disadvantage. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Siman, N.; Cleland, C.M.; Van Devanter, N.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, N.; Shelley, D. Effectiveness of village health worker–delivered smoking cessation counseling in Vietnam. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendtsen, M. Heterogeneous treatment effects of a text messaging smoking cessation intervention among university students. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spears, C.A.; Hedeker, D.; Li, L.; Wu, C.; Anderson, N.K.; Houchins, S.C.; Vinci, C.; Hoover, D.S.; Vidrine, J.I.; Cinciripini, P.M.; et al. Mechanisms underlying mindfulness-based addiction treatment versus cognitive behavioral therapy and usual care for smoking cessation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laude, J.R.; Bailey, S.R.; Crew, E.; Varady, A.; Lembke, A.; McFall, D.; Jeon, A.; Killen, D.; Killen, J.D.; David, S.P. Extended treatment for cigarette smoking cessation: A randomized control trial. Addiction 2017, 112, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskins, L.B.; Payne, C.A.; Schiavone, W.M.; Beach, S.R.; MacKillop, J.; VanDellen, M.R. Feasibility, tolerability, and potential advantages of a dyadic financial incentive treatment for smoking cessation among dual-smoker couples: A pilot study. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, H.; Nahvi, S.; Arnsten, J.H.; Brinkman, H.R.; Rivera-Mindt, M.; Wetter, D.W.; Bloom, E.L.; Price, L.H.; Richman, E.K.; Betzler, T.F.; et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of smartphone-assisted mindfulness-based intervention with contingency management for smokers with mood disorders. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, H.; Luijten, M.; Poppelaars, A.; Johnson-Glenberg, M.C.; Granic, I. Mechanisms of change in a go/no-go training game for young adult smokers. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, E.L.; Japuntich, S.J.; Pierro, A.; Dallery, J.; Leahey, T.M.; Rosen, J. Pilot trial of QuitBet: A digital social game that pays you to stop smoking. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zale, E.L.; Maisto, S.A.; De Vita, M.J.; Hooten, W.M.; Ditre, J.W. Increasing cessation motivation and treatment engagement among smokers in pain: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 29, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.; Zou, G.; Shi, J.; Chen, W.; Gong, X.; Wei, X.; Ling, L. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a WHO-5A model based comprehensive tobacco control program among migrant workers in Guangdong, China: A pilot study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausherr, Y.; Quinto, C.; Grize, L.; Schindler, C.; Probst-Hensch, N. Smoking cessation in workplace setting: Quit rates and determinants in a group behaviour therapy programme. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.D.; Ferris, K.A.; Metzger, A.; Gentzler, A.; Duncan, C.; Jarrett, T.; Dino, G. Physical activity and quit motivation moderators of adolescent smoking reduction. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.S.; Bell, M.L.; Armin, J.S.; Giacobbi, P.R.; Nair, U.S. A telephone-based guided imagery tobacco cessation intervention: Results of a randomized feasibility trial. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larisa, A.Z.; Ibatov, A. Effectiveness of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment of tobacco dependence among health professionals. Hyg. Sanit. 2020, 99, 390–393. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Fernández, V.; Díaz-Toro, E.C.; Reitzel, L.R.; Guo, L.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Calo, W.A.; Shih, Y.C.; Wetter, D.W. Combined treatment for at-risk drinking and smoking cessation among Puerto Ricans: A randomized clinical trial. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhanjee, S.; Lal, R.; Mishra, A.; Yadav, D. A randomized pilot study of brief intervention versus simple advice for women tobacco users in an urban community in India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2017, 39, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Palm Reed, K.M.; Bloom, E.L.; Minami, H.; Strong, D.R.; Lejuez, C.W.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Hayes, S.C. A randomized controlled trial of distress tolerance treatment for smoking cessation. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018, 32, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japuntich, S.J.; Lee, L.O.; Pineles, S.L.; Gregor, K.; Joos, C.M.; Patton, S.C.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; Rasmusson, A.M. Contingency management and cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma-exposed smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Addict. Behav. 2019, 90, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, J.; Staiger, P.K.; Hayden, M.J.; Hughes, L.K.; Youssef, G.; Lawrence, N.S. A randomized controlled trial of inhibitory control training for smoking cessation and reduction. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 87, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brody, A.L.; Zorick, T.; Hubert, R.; Hellemann, G.S.; Balali, S.; Kawasaki, S.S.; Garcia, L.Y.; Enoki, R.; Abraham, P.; Young, P.; et al. Combination extended smoking cessation treatment plus home visits for smokers with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 19, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boffo, M.; Zerhouni, O.; Gronau, Q.F.; van Beek, R.J.; Nikolaou, K.; Marsman, M.; Wiers, R.W. Cognitive bias modification for behavior change in alcohol and smoking addiction: Bayesian meta-analysis of individual participant data. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2019, 29, 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briere, J.B.; Bowrin, K.; Taieb, V.; Millier, A.; Toumi, M.; Coleman, C. Meta-analyses using real-world data to generate clinical and epidemiological evidence: A systematic literature review of existing recommendations. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Song, F.; Gu, H.; Wang, J.; Jia, G.; Lu, M.; Qian, J.; Wang, L.; Shen, J.; Ren, Z. An assessment of factors associated with quality of randomized controlled trials for smoking cessation. Oncotarget 2016, 16, 53762–53771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Sun, S.; He, Y.; Zeng, J. Effect of Smoking Reduction Therapy on Smoking Cessation for Smokers without an Intention to Quit: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10235–10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delle, S.; Kraus, L.; Maspero, S.; Pogarell, O.; Hoch, E.; Lochbühler, K. Effectiveness of the national German quitline for smoking cessation: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Foll, B.; Piper, M.E.; Fowler, C.D.; Tonstad, S.; Bierut, L.; Lu, L.; Jha, P.; Hall, W.D. Tobacco and nicotine use. Nature reviews. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).